Abstract

Within the contemporary art system complex, constantly-changing cultural features coexist with stratified acts of dealing. The art market operates as a collective mediation structure, developing a multiple agency: financial and economic, educational, political and social. In this article, we offer the result of an empirical test dedicated to the identification of unseen changes in the informal organizational pattern of the market. Observing the behavior of selected samples, we focused, firstly, on the networks of artists and commercial galleries at the Art Basel fair; and, secondly, on the group and solo shows organized by a relevant sample of international contemporary art museums and exhibitions spaces. These analyses offer an insight into the changes that occurred from 2005 to 2013, encompassing the quantitative growth of the art system infrastructure and the effects of the crisis of 2008.

1. Premises

Complexity is a structural predicate of the contemporary art system (Danto 1964; Dickie 2000).1 Its elusive character evades efforts to provide a single definition and challenges most attempts to outline a clear and stable picture.

The contemporary art system is also a market, and since the 1970s2 it has been studied as such by a large number of scholars. A great many agents operate in this market, encompassing a wide range of activities that support a fast-growing and progressively globalized trade in artworks. It is a market that has proved capable of bringing significant flows of capital from the financial market into the art world as an alternative form of investment (Pesando 1993; Mei and Moses 2002; Renneboog and Spaenjers 2013). It is a market in which the supply chain currently offers a large and ever-increasing variety of goods: paintings, sculptures, drawings, writings, books, prints, photos, videos, performances, memories and archives, relics, and objects of various kinds. As in many other markets, its trade activities respond to different needs and consumer behaviors: symbolic capital acquisition, financial risk hedging, cultural or aesthetic passion, pleasure, and political activism (Bourdieu [1979] 1984).

A quick glance at the last two decades clearly indicates that one of the most impressive features of the contemporary art system is its quantitative growth. This dynamic can be easily detected looking at the market dimension of the system. In 2000, there were approximately 55 established international art fairs while in 2018 there were close to 300 of them (Baia Curioni 2012; McAndrews 2018, 2019). In the same year, the overall value of sales was estimated to have reached 16.5 billion dollars.

Auction sales tripled from 2000 to 2007, reaching 33 billion dollars before the reduction in activity following the 2008 crisis. In 2018, the overall volume was 29 billion dollars, driven in particular by the high end of the market featuring works priced at over 10 million. The fast-growing online market reached an estimated 6 billion dollars and an average 11% growth in six years. The global exchanges recorded in 2018 amounted to 67.4 billion dollars, with an advanced sales value of 9% in 10 years and 40 million in transactions. An impressive 310,000 businesses are estimated to operate in the art market, employing close to 3 million people, with a 20 billion turnover and 375,000 additional jobs in external support (McAndrews 2019) but this expansion is not only happening in the market infrastructure. The large number of Contemporary Art Museums that have been built and opened since the beginning of the 1990s—a number that strongly increased in the early 2000s3—shows how the growth involved the overall structures of the contemporary art world. Quantity is not quality, but a quantitative shift of this size needs to be understood not only as a mere infrastructural transformation but also as a cultural challenge. This seems particularly true considering that the art market is a peculiar kind of market: a market that participates in a system that transforms the very nature and function of the object being traded. We are not referring here to the Marxian notion of use value as opposed to exchange value, which is the transformative function of every market even if very narrowly defined (Adorno [1938] 2002), but rather to the art market’s capacity to change the intimate cultural nature of goods altogether through the acts of selling and appreciating them (Moulin [1967] 1989, p. 12).4 The relation is bidirectional: the late 20th-century art history shows that everything, every good and every tangible formal representation can be considered an artwork if placed in the right context of narrative and institutions.

Symmetrically, anthropologists tell us that every artwork, even the holiest and most representative, can potentially acquire the status of a mere commodity, whether temporarily or permanently (Appadurai 1986). The results of many different top-end auctions offer a clear example of this trajectory: the artworks, even the rarest and the most celebrated become commodities traded for sound and often—though not always—legitimate speculative reasons, without necessarily losing their auratic dimension (Benjamin 2013).5 Beyond the rhetoric of the so-called “genius”6 and even beyond the significance established by art historians, the hammered prices of artworks may rise on the basis of perfectly cynical and narrow financial strategies (Thompson 2008), or as the result of calculated strategies of symbolic capital acquisition (Bourdieu [1979] 1984). In this game, the prices themselves and their dynamics are part of the prestige and symbolic life of the artwork and thereby acquire specific cultural meanings (Velthuis 2003).

These figures and their implications have been scrutinized and discussed quite often. The tension between the fragile meaningfulness of individual art practices and the “arbitrariness” of a volatile, powerful, and collective market represents a conundrum to be debated over the last 50 years and a challenging topic for art historians.

The work of an artist cannot be conceived as a “standard” market-oriented practice (Bourdieu 1996).7 At the same time, the market dimension of the art system seems to maintain a specific cultural role which is not only due to its significant influence on the artists’ careers and on their capacity to sustain their professional choices. The market dimension produces specific narratives and may also influence the behavior of art institutions (like museums and art schools).

In this article, we assume that this tension—and the way in which it has been conceptualized—offers a fertile point of view for interpreting the history of the so-called contemporary art system: a history of the ideological and organizational way in which the hyper-mobilized civilization of the 20th century included, and somehow also neutralized, the “revolutionary” independence of poetic knowledge.

We decided to focus our attention on a specific, globalized, segment of the market dimension of the system, in order to offer an evidence-based contribution on its behaviors. At the same time, we considered the “art market” in a perspective that encompasses the economic and the cultural dimension of the exchanges.

A multiplicity of imaginaries and functions coexisting within the same act of dealing is nothing new for art historians and social scientists, and it is certainly not a characteristic exclusive to contemporary art markets.8 The linguistic and symbolic dimension of human agency gives rise to the possibility that any act of mediation implies representation and interpretation and, therefore, the transformation of the object, with the latter potentially acquiring different meanings in different contexts and formats of perception.

What is interesting from our perspective is the process through which this cultural and transformative function of the contemporary art system and market is institutionalized, and how its trajectory may be changing. The art system’s agency, unfolding as a mediating practice9 enforced by specific institutional frameworks, exceeds the traditional economic definition of markets10 and paves the way for extending the very concept and function of markets beyond their agency centered on dealing and the efficient allocation of resources.

The art system can be studied as a market, cultural engine, and civilizational attractor.11 The coexistence of these dimensions is a core feature that is reflected in the social agency of art practices and in the overall social relevance of the arts.

2. The Art Market and Its Multiple Agencies

To understand an extremely large and complex social phenomenon such as the art system, it proves useful to adopt a practice-based perspective (Nicolini 2012) in which social phenomena are conceived as routinized performances mobilizing the bodily, social, discursive, and material dimensions (Nicolini 2017).

By approaching it as a constellation of practices, defined as “regimes of a mediated object-oriented performance of organized sets of sayings and doings” (Nicolini 2017, p. 21), it is possible to assess and describe its features in a processual and multi-layered way and, in the same vein, to advocate for a processual and performative understanding of institutional and organizational phenomena (Czarniawska 2014). Keeping with this perspective, we observed the patterns of forms of agency that make up the art system, offering a possible and emergent description of it rather than proposing an ex ante definition based on the above-mentioned traditional dualism between market-oriented and cultural-oriented views of the system.

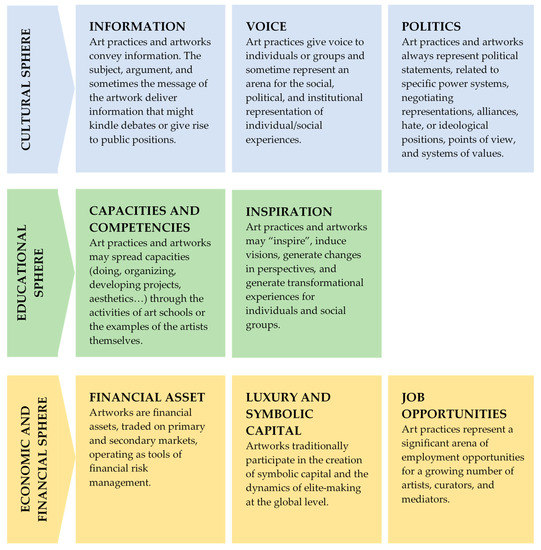

The type of work enacted through this agency, producing and reproducing the system, could be conceptualized as a part of the cultural public sphere, as a component of the educational sphere, or as a part of the economic and financial sphere (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Forms of art system agencies.

The coexistence of these different layers is crucial for the reproduction of contemporary art in modern societies. Although the various stakeholders may perceive only a limited number of these facets, their entanglement defines and frames the legitimacy of the experience and practice of art in contemporary societies.

Keeping with this perspective, we introduce here the idea of viewing the system as a bundle of agencies and practices. We offer a possible preliminary classification of the system, that is, we approach it with a view to scaling down its complexity.

Secondly, we present in the following part of the essay the results of a longitudinal study exploring some of the microstructures—conceived as repeated organizational patterns—that support the reproduction of this multi-layered set of features focusing on the relationships between market institutions and museums.

3. Is the Role of Art Market Changing?

The overall contemporary dimensions of the art world and its relatively fast growth since the early 2000s represent an unprecedented historic innovation. Some scholars see this quantitative dynamic as the frame in which an organizational transition is taking place, with the dealer–collector relationship displacing the dealer–critic one as the prevailing form evaluating contemporary artworks and artists.12

The consequences of this transition seem to be significant in that the dealers/collectors pairing suggests the image of an art world essentially dominated by market-driven choices that take the place of theoretical, curatorial, and art historical appraisals of artworks.13

Significantly enough, Seth Siegelaub, one of the most relevant and creative representatives of art marketing practices in the New York scene during the 1970s, organized his last provocation at Art Basel 2013 by vigorously questioning the integrity of the art system as a field of cultural production.14

In this paper, considering the complexity and stratification of the art system, we develop the hypothesis that over the past few years the system has operated through dealer–critic and dealer–collector relationships simultaneously, without being dominated by a specific pattern.

The informative “smallness” of the art system implies continuous contact and information flows among actors operating at different levels. At the same time, the hierarchical structure of the system implies that there are deep informational asymmetries between actors.

What we try to show is that the main line of tension is therefore between insiders and outsiders—as defined by Kindleberger (1991)—or, more precisely, between different categories of insiders and outsiders operating in the system. Each of these categories includes collectors, artists, gallerists, dealers, and institutions with both dealing and cultural roles.

Their game is informal; it is comprised of professional credibility, financial interests, friendships, alliances, marriages, tacit knowledge, social status, tastes, and habitus that together give rise to a multidimensional network of volatile and interconnected practices. Within this loose-knit network, a few stable relational and organizational forms can be identified. Their function is to offer stability and resilience to the system as a whole while at the same time regulating and exploiting the differences among actors and between sets of available information.15

However, these informal organizational patterns do not necessarily remain the same over time. Exogenous shocks—such as the dimensional growth of the system or the consequences of a global financial crisis—might produce unforeseen changes, eventually transforming not only the system’s market practices but its overall forms of agency and, therefore, the ultimate meaning of art practices in our societies.

4. Materials and Methods

The research presented in this article is designed in an attempt to address some of these questions by constructing and assembling different databases. The first such database charts the galleries and artists that showed at Art Basel in the eight years from 2005 to 201316; the second includes the activities (collective and solo exhibits) of 35 contemporary international art museums and exhibition spaces in the same span of years17; and a third outlines the auction prices of a selected set of artists from 2005 to 2019.18

These sets of information allow us to take an initial empirical and descriptive look at some common, stable organizational structures, focusing in particular on the behaviors of galleries and museums.

More precisely, we decided to follow up on some of the choices made by a specific set of world galleries—the ones included in the Art Basel fair from 2005 to 2013—and to use the choices made by a sample of contemporary international art museums during the same time period as a control group. Using the information offered by the Art Basel fair, we collected the names and demographic data of all the artists that exhibited at the fair. Through the websites, we collected information about all the group and solo exhibitions curated by each museum included in the sample.

We focused on the behaviors of galleries and museums in order to understand if and how the quantitative shock of the last 20 years has produced a detectable change in the art system’s informal but stable constituencies, and in what direction.

The choice of the time span (2005–2013) allows us to consider four years of infrastructural market growth (2005–2008) and five years (2009–2013) in which the system reacted to the massive 2008 financial crisis, eventually recovering from its main short-term effects.

Our empirical observation was divided into three parts.

- In the first, we considered the world of galleries, identifying regular patterns in their operations.

- In the second, we concentrated on museums, looking at the specific features of their behavior.

- In the third, we focused on some overlaps and interactions between these two different institutions.

- In the conclusion, we present and discuss the empirical evidence collected.

5. The Art Basel Galleries

Galleries act as market agents even if they are not pure dealing agents. Galleries represent specific artists, promote and sell their works through exhibits, catalogs, events, and often operate as trustworthy advisors for important collectors. The definition of gallery encompasses institutions that vary greatly in terms of dimensions, centrality, and financial and organizational capacities. One of the most striking trends in recent years is the tendency for galleries to become polarized, with a small number of huge, multinational, primary, and secondary market galleries (such as Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth) on one side and all the rest on the other side. The rest are composed of international or national small to medium-sized galleries. The distinction between secondary and primary market galleries that used to be important is now much less clear-cut. With few exceptions, galleries are relatively small firms and represent a limited number of artists in a primary and secondary market perspective. Their sustainability is based on a combination of short-term operations (selling artworks to cover the company’s upfront costs) and medium long-term operations (sustaining, controlling, and increasing the artists’ value and status). There is a high level of investment and sunk costs for each artist included in each gallery roster, and galleries thus tend to concentrate on a relatively small number of trusted relationships with artists.

Art Basel is the most well-established contemporary art fair at the global level and over the last 20 years was the fair that attracted the wealthiest collectors, representing an opportunity for participating galleries to cover a significant part (from the 30% to the 50%) of their annual sales. This is why a large number of galleries apply for admission each year, giving rise to lengthy waiting lists. A small number of galleries that are already members decide on admission through a co-optative mechanism. Although the member galleries do employ different strategies, a common feature in Basel is that the artworks exhibited there are the ones with the best chances of being sold.

In order to develop an overview of the galleries’ behaviors, we decided to consider the panel of all the galleries admitted to Basel from 2005 to 2013.

Table 1 provides a clear picture of the population of galleries admitted to Basel in the period under consideration (2005–2013).

Table 1.

Number and rotation of galleries at the Art Basel fair.

The overall distribution of incoming and outgoing galleries is stable as is the overall rotation of the group.

Of the 508 galleries admitted during these nine years, 191 (38%) were stable participants in the fair (eight or nine times) while 96 (19%) were admitted for only one year.19 The number of galleries that are admitted for only one year remains stable over time (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of galleries admitted to Art Basel for only one year.

As shown in Table 3, the number of artists included in the Art Basel galleries’ roster increased significantly in 2006 and 2008 before stabilizing, and the overall rotation of artists (number of new incoming and old outgoing) tended to decrease in the last part of the period.

Table 3.

Number of artists at the Art Basel fair.

Considering only the 155 galleries that were admitted for all nine years—the ones that make up the true backbone of the fair—the artists that were included in more than 10 rosters are eight highly-established names, among whom Andy Warhol has maintained a dominant position (Table 4).

Table 4.

Artists included in at least 10 rosters of the stable galleries (included for nine years).

A stable cohort of artists that appeared in the art fair’s rosters at least for seven years out of the nine possible years (48% of the total, see Table 5) surrounds this core group.

Table 5.

Artists’ inclusion in the galleries’ rosters.

There were only 976 artists who appeared only one or two years (24% of the total). These figures indicate that the stable galleries representing the “structural backbone” of the fair from 2005 to 2013 concentrate their actions on the same group of 1900 artists. Only 24% of their portfolios vary more widely in terms of artists on offer.

Another relevant finding is that, if an artist is included in more than two rosters, his or her ability to remain at Basel for a longer time changes: 95% of the artists included in two or more rosters show a duration of seven to nine years. This percentage falls to 39% for those who were represented by an average of fewer than two galleries. The interpretation of these figures is not univocal: Basel is a highly-selective environment, and once an artist has been included and shown, the gallery environments tend to keep him or her for many years.20

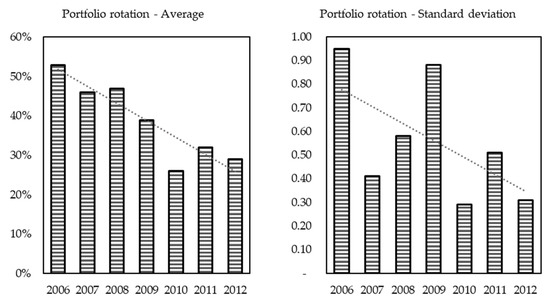

This tendency toward a stable set of artists increased after the 2008 financial crisis. We calculated the portfolio rotation21 of the Basel galleries considering the artists that are eliminated and the ones that are included in each roster and found that this index decreased after 2008 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Galleries’ portfolio rotation.

After the financial crisis, the galleries apparently concentrated on the same artists they had presented at previous editions of the fair, reducing the number of changes. This attitude indicates a risk reduction strategy adopted widely among the Basel galleries (as indicated by the reduction of the standard deviation of the rotation).

6. Contemporary Art Museums and Exhibition Spaces

Museums work as cultural agents. They operate by acquiring and preserving collections, through research and publishing, and by mobilizing different audiences and media outlets (events, online platforms, exhibits, talks, educational programs, zines, etc.). Their purposes might vary depending on the founders’ mission statements.

From a market perspective, their sets of actions might be compared to that of “rating” agencies: acquisition by a museum or exhibition in a solo or collective show can be considered a sign of reputation-building for an artist and his or her works.

For our research, we selected a sample of 35 contemporary art museums and exhibition spaces operating in 15 nations, listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Contemporary art museums and exhibition spaces in our sample.

The star system has a perceptible influence on the museum environment, and indeed the 10 most-exhibited artists of the period are shown in Table 7.22

Table 7.

Most-exhibited artists.

Andy Warhol is the leading star of these nine years for both galleries and museums.

At the same time, 74.1% of the sample only appeared once in the nine years while only 4.1% was shown more than six times (Table 8).

Table 8.

Artists and number of exhibitions.

This finding, almost the opposite of the data collected for galleries (see Table 5 above), indicates that the exhibition choices of each individual museum are largely independent of the choices made by other museums, which is consistent with the promotional and cultural role these institutions play.

7. Galleries and Museums: Independence and Relationships

The boundaries between the practices of galleries and those of museums have been fading since the evolution of so-called “primary market” galleries in the 1970s. The growing size and role of the market in the last 25 years, and the growing demand for artworks and art in general, has reduced incentives to maintain a long-term, faithful relationship between artists, galleries, and museums. The increasing role of the economic side of the art agency operates as a tool for the progressive mobilization of the art system in a process that is consistent with increasing liquidity and relational fluidity.

Is this dynamic really being acted out? Are the roles of both galleries and museums actually on the verge of a profound change? Is it possible to empirically describe the dynamics being played out in the core of art market structures?

In 2015, The Art Newspaper openly questioned museums’ relative independence from the seductions of the market: “Nearly one-third of the major solo exhibitions held in US museums between 2007 and 2013 featured artists represented by just five galleries, according to research conducted by The Art Newspaper. We analyzed nearly 600 exhibitions submitted by 68 museums for our annual attendance-figures survey and found that 30% of prominent solo shows featured artists represented by Gagosian Gallery, Pace, Marian Goodman Gallery, David Zwirner, and Hauser & Wirth” (Halperin 2015).

In the next section, we develop two empirical tests that offer an evidence-based perspective on the issue.

7.1. Independence

One initial descriptive analysis considering the overlap between the museums and the Art Basel galleries portfolio of artists indicates a consistent degree of independence between the two groups of institutions.

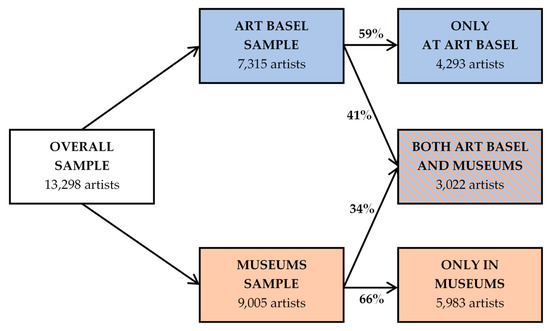

The overall sample is composed of 13,298 artists, 7315 appearing at Basel from 2005 to 2013, and 9005 exhibited in the same years by the selected sample of 35 contemporary art museums and exhibition spaces (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Overall sample structure.

A total of 3022 artists appeared in both samples, 41% of all those exhibited at Basel, and 31% of those exhibited in the museums.

Of the artists exhibited in the selected museums and spaces, 66% are not included in Basel, thus confirming the museums’ independence from the fair system.

A further test carried out on the museum sample and a group of 52 selected Basel galleries23 supports the description above and shows that the two groups not only seem to act independently but also operate through different networking structures.24

- The museum–artist network is characterized by a higher level of degree centrality and a lower betweenness for the exhibited artists: this implies that each artist has relationships with a larger number of colleagues in the museum world and that each museum tends to privilege different clusters of artists.

- The gallery–artist network displays a contrasting structure: a lower degree and higher level of betweenness. This indicates that the galleries operate on smaller but more similar groups of artists.

The differences in the networking structures reveal that the two groups of institutions played diverse roles and maintained different relationships with the population of artists during the nine years under observation: the galleries, acting according to a dealing perspective, operated with fewer artists and on an overall more similar and limited group of artists, characterized by a higher market profile. The museums worked with a wider set of artists and according to a much more independent perspective.

Given these findings, market and cultural roles seem to be distinct.

7.2. Connections

Considering the museums’ exhibitions, it is important to distinguish between solo and group shows. The first are monographic, dedicated to a single artist as a tribute to his or her career or to welcome a promising newcomer. These shows involve a specific investment of curatorial labor and funds for the institutions and represent a critical statement about the work of an artist. The second, group shows, are also important reputational signals for the artists involved but they are collective exhibitions, sometimes characterized by a specific theme, and artists might be included for various reasons.

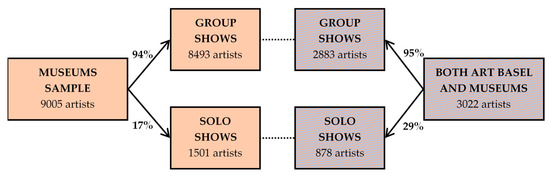

It is interesting to observe that from 2005 to 2013, 29% of the Basel artists (878) were included in the solo shows produced by the museums. If we look at the general museum sample, only 17% of the artists had a solo show (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Solo and group shows: Museums and Basel.

Although the action of museums generally seems to be independent of market signals, the artists who were included at Basel received significantly greater attention from the museums. This overlap requires further investigation. Is this a sign that galleries use the curatorial choices of museums as a point of reference? Or the opposite? Is it a matter of combined attention from both the institutions converging on a given artist?

7.3. Further In-Depth Inquiry

The last test that we conducted considered a specific sub-sample of artists, all those that have been included in the galleries’ rosters after 2008. This is a group of 75 newcomers: 64 of them selected by at least one of the 155 stable Basel galleries and 11 only selected by other, less-stable Basel galleries.

For all of these artists, we considered the operations carried out by the sample of museums and charted the progression of auction prices from 2005 to 2019, looking in particular at the level of market “liquidity” calculated as total auction turnover for each year and artist.

These are the main findings:

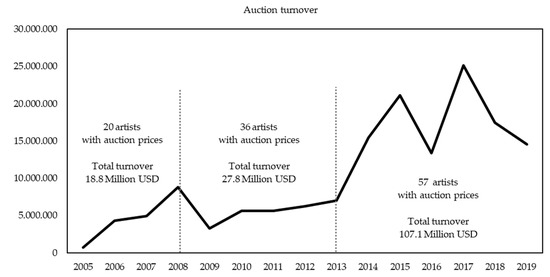

- Auction liquidity for this group of artists rose significantly after 2013, with a total turnover of 107.1 Million dollars from 2013 to 2019 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Auction turnover of selected Art Basel artists.

Figure 5. Auction turnover of selected Art Basel artists. - Before their inclusion at Basel, 19 artists were exchanged, with an average yearly turnover of 180,976 dollars. After their inclusion, the number of artists with auction sales rose to 37 up to 2013 and then to 57 since 2014, with an average yearly turnover of 313,096 dollars (a 73% increase).25 This is a group of young newcomers to the market who were been included in the Art Basel roster after 2008 and increased their overall market value after 2013.

- Museums have a significant presence in relation to this group of artists: 55 of them (73%) were exhibited in a museum between 2005–2013 (as compared to an average of 41% of the total number of Basel artists, see Figure 3). Moreover, 24 of them (32%) were given solo shows, as compared to an average of 29% (see Figure 4). The stable Basel galleries represented 22 of them. This tells us that the action of museums mainly overlaps with the action of a specific group of insiders, represented by the stable Art Basel galleries.

- The auction liquidity of the artists featured in solo shows is 1,279,000 dollars as compared to an average of 647,000 dollars, and an average of 64,000 for the artists who were not included in any museum exhibitions.26 This means that museum exhibitions, and especially solo shows, have an impact on auction prices.

- The last significant finding is that the action of galleries follows in the footsteps of museums: 16 cases out of the 23 characterized by a solo show indicate that the museums’ activities anticipated the galleries’ commercial intentions to deal in that artist’s work. This evidence suggests that cultural and dealing features may be closely connected in terms of sequence, but they are nonetheless organized with curatorial evaluations prevailing over dealing practices.

8. Main Findings and Limitations

In this article, we focus our attention on the systemic dimension of the contemporary art market, in order to offer an evidence-based contribution on its behaviors, while simultaneously considering it in a perspective that encompasses the economic and the cultural dimension of the exchanges. We thus first offered a comprehensive overview of the art system as both an economic and a cultural environment. The economic vs. cultural binary conceptualization is at once simplistic in theoretical terms and difficult to operationalize from an empirical point of view; in this paper, we suggest that, in order to overcome these limits, it would be fruitful to begin by following action nets (Czarniawska 2004) so as to observe the features of the system as emerging from this temporary state of stabilization. Organized around three main spheres of action and meaning—cultural and public, educational, economic, and financial—the system unfolds as a bundle of different forms of agency.

In the central section of the article, the empirical analysis, we focused on two databases of information collected regarding Art Basel galleries and a sample of contemporary art museums and exhibition spaces selected from around the world. This analysis identified a stable informal pattern of organizational choices that differentiates the sets of actions of the two institutional groups, museums and galleries; that is to say, patterns of choices distinguish the role of “cultural legitimation” from the commercial perspective.

In the last part of the article, considering a group of artists selected by these galleries in and after 2008, we noted an intense overlapping of action between the two groups of institutions. In reacting to the 2008 crisis, the most important Art Basel galleries intensified their focus on new artists and looked attentively at the choices made by the group of museums under consideration here. We also found that the connection between these two institutional groups has a recognizably positive effect on the overall auction liquidity of the artists included in the sample.

The consistency between these two categories and the financial impact of such consistency does not affect the signaling and cultural role played by museums, and indeed moves by museums seem to anticipate both the galleries’ choices and the auction liquidity of the artists.

In spite of the system’s infrastructural expansion and the crisis of 2008, our analysis did not find evidence of a change in the informal organizational pattern of the art system.

The fact that we also found two artists who display intense auction liquidity and gallery presence that is not echoed by shows in the selected group of museums indicates that some artists may have dealer-led careers, as a relatively minor option.

The main limitations of our findings stem from our choice to develop an initial empirical overview and have to do with different issues. One is related to the sources: the Art Basel sample reflects a very specific gallery environment, while the sample of museums is quantitatively limited. The second order of limitation is methodological, suggesting that our findings could be productively supplemented by further qualitative inquiries. For example, the positive sequence “museum–gallery” empirically identified here needs to be reconsidered by looking at the complex set of relationships that may connect the work of gallerists to collectors, curators, and museums. Such informal relationships do not necessarily leave behind evidence that is explicit and easy to trace.

Further research is needed to build on this classification of the art system’s forms of agency. The most fruitful way to pursue such research would be through qualitative analyses, either focusing on specific artworks or following the network of practices at play in specific environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing, S.B.C. and M.E.P. (selected parts); methodology and formal analysis, S.B.C. and L.F.; review, data processing and visualization, L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This research was developed within a wider project organized by ASK—Art, Science & Knowledge Research Center at Università Bocconi, Milan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adorno, Theodor. 2002. On the Fetish character in Music and the Regression of Listening. In Essays on Music. Edited by Richard Leppert. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 288–317. First published 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1986. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large. Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, Carol, and Catherine De Zegher. 2006. Women Artists at the Millennium. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arper, Neil O., and Gregory H. Wassall. 2006. Artists’ careers and their labor markets. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture. Edited by Victor A. Ginsburg and David Throsby. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Baia Curioni, Stefano. 2012. A Fairy Tale: the art system, globalization, and the fair movement. In Contemporary Art and Its Commercial Markets. A Report on Current Conditions and Future Scenarios. Edited by Olav Velthuis, Stefano Baia Curioni and Maria Lind. Berlin: Sternberg Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baia Curioni, Stefano, Laura Forti, and Ludovica Leone. 2015. Making visible. Artists and galleries in the global art system. In Cosmopolitan Canvases. The Globalization of Markets for Contemporary Art. Edited by Olav Velthuis and Stefano Baia Curioni. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 2013. Charles Baudelaire. Un poeta lirico nell’età del capitalismo avanzato. Edited by Giorgio Agamben, Barbara Chitussi and Clemens-Carl Härle. Vicenza: Neri Pozza. [Google Scholar]

- Bielby, Denise. 2009. Gender inequality in culture industries: Women and men writers in film and television. Sociologie du Travail 51: 237–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. First published 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braden, Laura. 2009. From the Armory to academia: Careers and reputations of early modern artists in the United States. Poetics 37: 439–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braudel, Fernand. 1993. Civilisation matérielle, économie et capitalisme. XVe-XVIII siècle. Les jeux de l’échange. Paris: Le Livre de Poche, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Cornelia, and Lisa Gabrielle Mark. 2007. WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution. Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art. [Google Scholar]

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. 1987. The Imaginary Institution of Society. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coulangeon, Philippe, Hyacinthe Ravet, and Ionela Roharik. 2005. Gender differentiated effect of time in performing arts professions: Musicians, actors and dancers in contemporary France. Poetics 33: 369–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarniawska, Barbara. 2004. On Time, Space, and Action Nets. Organization 11: 773–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarniawska, Barbara. 2014. A Theory of Organizing. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniawska, Barbara, and Bernward Joerges. 1996. Travels of Ideas. In Translating Organizational Change. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Studies in Organization, vol. 56, pp. 13–48. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniawska, Barbara, and Guje Sevón, eds. 1996. Translating Organizational Change. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Studies in Organization, vol. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Danto, Arthur C. 1964. The Artworld. American Philosophical Association Eastern Division Sixty-First Annual Meeting, 15 Octorber 1964. The Journal of Philosophy 61: 571–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nora, T. 1995. Beethoven and the Construction of Genius: Musical Politics in Vienna 1792–1803. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dickie, George. 2000. The Institutional Theory of Art. In Theories of Art Today. Edited by Noël Carroll. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Equi Pierazzini, Marta, Alberto Monti, and Paola Dubini. 2017. Glass Cliff in Art? An Exploratory Study of Women Artists’ Careers at Art Basel System. Paper presented at the European Academy of Management (EURAM), Glasgow, UK, 21–24 June, ISSN 2466-7498. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Graeme. 2003. Hard Branding the cultural city. From Prado to Prada. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27: 417–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graw, Isabelle. 2012. In the grip of the market? On the relative heteronomy of art. The art world and art criticism. In Contemporary Art and Its Commercial Markets. A Report on Current Conditions and Future Scenarios. Edited by Olav Velthuis and Maria Lind. Berlin: Sternberg Press, pp. 183–208. [Google Scholar]

- Grodach, Carl. 2013. Cultural Economy Planning in creative cities: Discourse and practice. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37: 1745–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerzoni, Guido. 2014. Museums on the Map. 1995–2012. Torino: Allemandi. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, Julia. 2015. Almost one third of solo shows in US museums go to artists represented by five galleries. The Art Newspaper. April 2. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/almost-one-third-of-solo-shows-in-us-museums-go-to-artists-represented-by-five-galleries (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Heartney, Eleanor, Helaine Posner, Nancy Princenthal, Sue Scott, and Linda Nochlin. 2013. After the Revolution. Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art. Munich, London and New York: Prestel. [Google Scholar]

- Iamurri, Laura. 2016. Un Margine che Sfugge. Carla Lonzi e l’arte in Italia 1955–1970. Macerata: Quodlibet Studio. [Google Scholar]

- Karpik, Lucien. 2010. Valuing the Unique. The Economics of Singularities. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kindleberger, Charles. 1991. Storia Delle Crisi Finanziarie. Bari: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 1984. The Powers of Association. The Sociological Review 32: 264–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonzi, Carla. 1969. Autoritratto. Bari: De Donato. [Google Scholar]

- Lonzi, Carla. 1980. Vai pure. Dialogo con Pietro Consagra. Milano: Scritti di Rivolta Femminile. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrews, Claire. 2018. The Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report 2018. Basel: Art Basel. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrews, Claire. 2019. The Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report 2019. Basel: Art Basel. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, Jianping, and Michael Moses. 2002. Art as an investment and the Underperformance of Masterpieces. American Economic Review 92: 1656–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morineau, Camille. 2009. Elles@centrepompidou. Women artists in the collection of the Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création Industrielle. In Exhibition Catalogue. Paris: Editions Centre Pompidou. [Google Scholar]

- Moulin, Raymonde. 1989. Le marché de la peinture en France. Paris: Éditions de Minuit. First published 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini, Davide. 2012. Practice Theory, Work and Organization. An Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini, Davide. 2017. Practice Theory as a Package of Theory, Method and Vocabulary: Affordances and Limitations. In Methodological Reflections on Practice Oriented Theories. Edited by Michael Jonas, Beate Littig and Angela Wroblewski. Berlin: Springer International Publishing, pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Nochlin, Linda. 1988. Why have there been no great women artists? ARTnews, January 1971. In Women, Art and Power and Other Essays. New York: Westview Press, pp. 22–39, 67–71. First published 1971. [Google Scholar]

- North, Douglas. 1990. Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pesando, James E. 1993. Art as an Investment: The Market for Modern Prints. American Economic Review 83: 1075–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rengers, Merijn, and Olav Velthuis. 2002. Determinants of Prices for Contemporary Art in Dutch Galleries, 1992–1998. Journal of Cultural Economics 26: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renneboog, Luc, and Christophe Spaenjers. 2013. Buying Beauty: On prices and Returns in the Art Market. Management Science 59: 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, Sophie. 2009. Unconcealed. The international Network of Conceptual Artists 1966–1977. Dealers Exhibitions and Public Collections. London: Ridinghouse. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, Pier Luigi. 2009. Kunst=Kapital? Invitation to a pointless investigation. In Imaginary Economics. Quando L’arte sfida il capitalismo. Edited by Olav Velthuis. Milano: Johan & Levy, pp. 113–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlin-Andersson, Kerstin. 1996. Imitating by Editing Success: The Construction of Organizational Fields. In Translating Organizational Change. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Studies in Organization, vol. 56, pp. 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sapori, Armando. 1982. Studi di Storia Economica. Secoli XIII–XIV–XV. Firenze: Sansoni. [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz, Vaughn. 2009. Social and symbolic boundaries in newspaper coverage of music, 1955–2005: Gender and genre in the US, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. Poetics 37: 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, Eran, Arnout van de Rijt, Alex Miltsov, Vivek Kulkarni, and Steven Skiena. 2015. A Paper Ceiling: Explaining the Persistent Underrepresentation of Women in Printed News. American Sociological Review 80: 960–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Dan. 2008. The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Velthuis, Olav. 2003. Talking prices Symbolic Meanings of Prices on the Market for Contemporary Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Velthuis, Olav. 2009. Imaginary Economics. Quando L’arte sfida il capitalismo. Milano: Johan & Levy, pp. 113–28. [Google Scholar]

- White, Cynthia A., and Harrison C. White. 1965. Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zapperi, Giovanna. 2017. Carla Lonzi. Un’arte della vita. Roma: DeriveApprodi. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The art system is an institutional environment that encompasses a multiplicity of different actors in many different regions of the planet. This world traditionally includes artists, museums, galleries, fairs, auction houses, exhibition spaces, dealers, curators, art historians, activists, independent spaces, art magazines, art publishers, press agents, academic and non-academic art schools, research institutes, and departments of philosophy, economics and management, art, cultural and curatorial studies in different faculties. Its boundaries are indistinct and unstable. It is difficult to say what is “in” and what is “out” and why, but the consequences of being included or excluded are tangible. | ||||||||||||

| 2 | The art market became a relevant subject matter for research in the 1970s with Raymonde Moulin’s seminal and precious contribution (Moulin [1967] 1989). We are limited here to mention the framing of the contemporary art system in economic terms, but of course the relation between the cultural and economic sphere is more articulated, being historically-layered, complex and multidirectional. Especially during the 1980s, a double-sided process of economization of the arts and culturalization of the economy took place (Velthuis 2009). This process entailed not only the identification of arts as financial and luxury assets and of artists as superstars, but also the rising attention of the economic sphere to cultural processes, leveraging on the symbolic sphere and the construction of imaginaries (Sacco 2009). An example is the rising of culture-led urban regeneration processes and, in the 1990s, the integration of cultural interventions (urban design and architecture, events, public art) in “traditional” interventions such as economical and infrastructural redevelopments (Evans 2003; Grodach 2013). | ||||||||||||

| 3 | See for example Guerzoni (2014) for an investigation upon museum opening and extensions between 1995 and 2012. Yet are no standard statistics on the number of contemporary art museums at the global level. There is strong evidence that a large number of new contemporary art museums have been created in emerging countries (China, Russia in particular) in the last couple of decades, in the same years many institutions moved into new landmark buildings or were created in different western cities pulled by the diffusion of cultural policies aimed at fostering the attractiveness and the creative scene of the cities. | ||||||||||||

| 4 | In her early work on the French art market, Raymonde Moulin noted that: “La haute dignité reconnue à l’art par notre société constitue l’endroit d’un systeme dont l’envers est la commercialisation de l’art: le marché des tableaux est le lien de cette secrète alchimie que opère la transmutation d’un bien de culture en merchandise”. | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Here we use the notion of “aura” in the sense suggested by Walter Benjamin: an irreducible distance that induces worship. | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Regarding this issue, see De Nora (1995). A critique of the rhetoric of genius along with the discourse on greatness and its implication has of course been developed by feminist art history and criticism; notably one of the first endeavors in this direction is represented by the seminal work by Nochlin ([1971] 1988). Evidently, the field had developed greatly and with many nuances since the 1970s; we just mention here some more recent works that build upon and recognize the centrality of Nochlin’s work, for example Armstrong and De Zegher (2006) and Heartney et al. (2013), in terms of scholarship, and Butler and Mark (2007); Morineau (2009), in terms of curating and exhibitions practices. Although the American realm has been particularly active, especially in the dawning moment of feminist art criticism, and has been a context where some experiences connected to the visual arts were crucial to the subsequent unfolding of the feminist reflection in art at a global level (Butler and Mark 2007), other geopolitical contexts have had their own stories of engagement with the problematic issue of marginalization of women in the art field. For example, In Italy a crucial thinker on these matters has been Carla Lonzi, an art historian and feminist theorist devoted to staking out critical practices of engagement with artists as individuals stripped of their aura as autonomous and creative geniuses (Lonzi 1969; Iamurri 2016; Zapperi 2017), and to debunking the cultural myth of the artist also in daily life practices (Lonzi 1980). | ||||||||||||

| 7 | The relationship between the contemporary art system as a whole and the art market has been traditionally complex and, often, also oppositional. | ||||||||||||

| 8 | The notion of “imaginary” is intended as a social force within global cultural processes, able to create collective meaning (Appadurai 1996; Castoriadis 1987). | ||||||||||||

| 9 | In this text we use the expression “mediating practice” to refer to processes of circulation and translation of ideas, meanings, resources and values in the art system. We are inspired here by the tradition of works in organization and management studies that—building on the sociology of Latour (1984)—mobilize the concept of translation to account for a process of spreading institutional elements Czarniawska and Joerges (1996); Czarniawska and Sevón (1996), with translation in this case referring to a type of reciprocal, non-unidirectional work in which what is translated is transformed and modified according to the new context and settings (Sahlin-Andersson 1996). | ||||||||||||

| 10 | North (1990) has defined markets as institutionally defined “baskets of rules” aimed at creating the most efficient (least expensive and most accessible) conditions for bringing together the demand and supply of any merchandise. | ||||||||||||

| 11 | The evidence of the cultural function of market is established also since the fundamental works of Sapori (1982) and later of Braudel (1993) on the relevance of the Mediterranean mercantile exchanges in the early European Renaissance. This feature today is common to different luxury or symbolic good markets (fashion and design in particular). | ||||||||||||

| 12 | The role of the dealer–critic relationship as a key and innovative feature of the Avantgarde-based art system has been suggested by White and White (1965); the idea of dealer–collector dominance has been suggested by Graw (2012), among others. | ||||||||||||

| 13 | One initial consequence is the convergence of the art and luxury markets and the subsequent evidence that a painting, even a renowned piece of world art history (not to mention an average good work), constitutes a fungible asset (Graw 2012). Such artwork is personal property, not different from a Ferrari or a luxury home, eventually privatized and made inaccessible to the public until the next sale. This idea powerfully fuels some stellar auction prices for modern-contemporary art pieces, privatizing the very making of art history as a supreme form of lux. | ||||||||||||

| 14 | “What makes a great artist? What makes a great artwork? Beauty? Emotion? Content? Originality? Novelty? Chance? Sensitivity? Genius? Rarity? Price? Who defines this value and how are these judgements made? Curators? Art Historians? Critics? Artists? Art dealers? Collectors? Museums? How is Art History made? What are the underlying mechanisms and roles? Are they the same everywhere in all times, in all societies, in all periods? How do you think Art History is made?” These were the questions raised by Seth Siegelaub in Art Basel Conversations in 2013. | ||||||||||||

| 15 | Richard (2009) invaluable work on the diffusion of conceptual art in Germany during the 1970s identifies a very interesting example of a long-term informal, stable alliance. | ||||||||||||

| 16 | Art Basel dataset: We collected data on all the galleries that participated in Art Basel between 2005 and 2013 and data on the artists presented every year by each gallery, thereby building a unique dataset on the basis of the fair’s original annual catalogues. We developed a longitudinal database of the portfolios of 508 galleries, their reciprocal connection and overlaps, and of indicators of the visibility of more than 7300 artists, mapping their mutual relations. We excluded the “Edition” section in the recognition that the market of printed multiples displays different dynamics. | ||||||||||||

| 17 | Museums and exhibition spaces dataset: We selected a sample of 35 international contemporary art museums and exhibition spaces, chosen according to their cultural significance on the basis of qualitative interviews with contemporary art curators. The database comprises information on 9005 artists, 16,947 group shows and 1948 solo shows from 2005 to 2013. | ||||||||||||

| 18 | Auction prices dataset: We charted auction sales prices for a selection of the artists included in the previous datasets. | ||||||||||||

| 19 | Calculated excluding the first and the last year of the sample. | ||||||||||||

| 20 | The inclusion of an artist in a gallery’s roster may depend on various factors: it can be the consequence of a long-lasting relationship or a short-term opportunity. In general terms, this inclusion can be considered a sign of the artist’s reputation. The fact of being shown by more than one gallery increases the intensity of this sign (Karpick 2010; Baia Curioni et al. 2015). | ||||||||||||

| 21 | Index portfolio rotation is defined as the sum of discontinuities (new artists in or old artists out), considered in percentage of the portfolio of each gallery. Artists who were presented for only one year are excluded. | ||||||||||||

| 22 | The imbalance in terms of representation of male and female artists highlighted by Table 4 and Table 7 could not be more striking. Indeed, previous studies have already shown how the overall representation of female artists in the Basel setting (2005–2012) is extremely low: women artists represented only 27% of the total and European and North American galleries displayed only 21% of women in their portfolios (Equi Pierazzini et al. 2017) and the situation is not getting better according to the 2019 Art Basel report, referring to 2018 data and indicating that the considered sample of primary market galleries represents 36% of female artists and the sale of their works accounts for the 32% of their annual turnover. Moreover, the bigger the gallery, the fewer female artists are represented are, with galleries with turnover over $10 million representing only 28% of female artists (McAndrews 2019). Studies have indeed already underlined the condition of gender inequality in the art market in terms of career mobility and wages (Arper and Wassall 2006) and in performance in terms of selling prices (Braden 2009; Rengers and Velthuis 2002)—in this respect from this essay emerges that there are not women artists among those with highest auctions prices. These kinds of problems are common also in other cultural sectors such as the music (Schmutz 2009) and editorial field (Shor et al. 2015) as well as the performing art sector (Coulangeon et al. 2005) and the movie industry (Bielby 2009). | ||||||||||||

| 23 | Artists were selected based on their years at Basel (nine) and the position of the booth within the overall fair layout, considering only the booths located along the central alley. The analysis was carried out by considering the two groups of institutions separately: the galleries with their artists and the museums with their artists. For both groups, the analysis treated the artists as nodes and the institutions as ties. | ||||||||||||

| 24 | In order to analyze the dynamics of gatekeeping activities, we performed a network analysis (software: UciNet) connecting artists, galleries and museums. We calculated the main centrality measures, focusing on “degree centrality” (expressing the number of ties surrounding each node) and “betweenness centrality” (expressing how central a node is in connecting to the others). For an artist, having a high degree of centrality means, first of all, that his or her works are presented by many galleries; second, he or she is exhibited with a relatively large number of artists; third, he or she is exhibited alongside central artists and tends to be a more stable feature of the fair’s displays over the years. On the other hand, a low degree does not necessarily imply that the artist’s career is undermined.

| ||||||||||||

| 25 | Auction values were adjusted for inflation. Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Historical rates. | ||||||||||||

| 26 | We excluded here four outliers, those artists who had more than 20 million in turnover from auction sales: Hurvin Anderson, Joe Bradley, Zhang Huan, and Farhad Moshiri. All of them were shown at the stable Art Basel galleries. | ||||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).