1. Introduction

Antiquities looting has become increasingly prominent in news headlines. Newspapers around the world show headlines reporting antiquities looting from Israel, Cambodia, China, Greece, Italy, Egypt, Peru, Syria, and the United States. Though reports of antiquities looting are found in all regions, many seem to be especially concentrated in areas of armed conflict. Indeed, many headlines suggest that a relationship exists between antiquities looting and armed conflict. Headlines such as “Syria’s Historical Artifacts Aren’t Just Being Destroyed by ISIS, They’re Being Looted” imply that parties involved in armed conflict are using antiquities as a source of funding” (

Robins-Early 2015). Although over 50% of archaeological sites globally have reported at least some degree of looting (

Proulx 2013), evidence on the extent to which antiquities looting is related to armed conflict is largely qualitative (e.g., case studies) or journalistic (

Baker and Anjar 2012;

Brodie 2003;

Di Giovanni et al. 2014;

Hanson 2015;

Howard et al. 2015;

Losson 2016).

Recent news articles on antiquities looting discuss antiquities looting as a source of funding for ISIS based on journalistic evidence that “by some estimates, these sales now represent ISIS’s second largest source of funding” (

Di Giovanni et al. 2014). While there is indeed evidence that ISIL has engaged in systematic antiquities looting (

Keller 2015), it is less clear whether ISIL represents a unique case or whether they should be viewed as the norm. Other articles argue that the sales made in the international illicit trade in antiquities could prolong or intensify conflict by providing a readily available source of goods to trade for weapons (

Baker and Anjar 2012). These articles do not distinguish between antiquities looting in support of conflict (e.g., as a source of funding for terrorist groups, a way to sustain a conflict by maintaining a supply of weapons, etc.) and antiquities looting that results from armed conflict but that is opportunistic in nature. Only a handful of articles have tried to disentangle this relationship and even they have had to rely on individual newspaper and magazine articles (

Howard et al. 2015). A few scholarly articles have also connected the trade in art and antiquities to prolonging conflict (

Brodie 2003); however, they tend to begin their discussion after the object has already been looted or discuss looting as part of the broader trafficking supply chain in conflict areas (

Bogdanos 2005;

Brodie and Sabrine 2018).

The evidence presented in such articles is important; however, if antiquities looting is indeed concentrated in areas of armed conflict, then it is also important to quantitatively assess what, if any, relationship exists between them. Systematically analyzing quantitative data to look at patterns across incidents and time is one way to complement journalistic and qualitative research. In this vein, several groups have worked to record and quantify looting and other damage to archaeological sites using satellite imagery, particularly in the Middle East (

Bowen et al. 2017;

Casana and Laugier 2017;

Contreras and Brodie 2010;

Cunliffe 2014;

Fradley and Sheldrick 2017;

Isakhan 2015;

Lauricella et al. 2017;

Parcak et al. 2016). While these efforts have accumulated large quantities of data, these have been collected with varying methodologies and goals that are often only tangentially related to conflict.

1 Further, only one study has used satellite imagery to explicitly look at the relationship between archaeological site damage and conflict.

2 Cunliffe (

2014) has recorded 18 forms of site damage at two sites in Syria over a 50-year period (imagines from the late 1960s, 2003–2004, and 2009–2010) and compared the extent of damage at these sites during times of peace to times of conflict. However, only one form of damage is directly related to looting and the qualitative comparison between times of peace and times of war does not differentiate between the multiple possible interrelated relationships that could exist between armed conflict and archaeological looting.

Two potentially interrelated relationships are especially important to consider: strategic antiquities looting in armed conflict and opportunistic antiquities looting in armed conflict. These relationships reflect two temporal orderings: antiquities looting preceding armed conflict (strategic) and armed conflict preceding antiquities looting (opportunistic). Antiquities—defined broadly in this research as any object over 100 years old located in the ground or embedded in a fixture of an archaeological site—have intrinsic value. Because of this value, they could be used to fund violent campaigns or to send political messages that attack cultural identity (

Van der Auwera 2012). Both cases represent strategic antiquities looting. By contrast, during armed conflict there can be a breakdown in social order that can lead to increases in crime in general, including antiquities looting. Antiquities looting in this case is opportunistic and akin to other types of crime resulting from a vacuum in social order, which may be committed for a variety of reasons.

This study assesses the relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict in Egypt to demonstrate the utility of quantitative data and methods for this area of research. Drawing on two criminological theories that look at the interaction between offenders and the settings of crime—routine activity theory and the CRAVED principles

3—this study looks at both the overall relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict and their temporal ordering in Egypt from 1997 to 2014. Autoregressive Distributed Lag Models (ARDL) with a bounds testing approach are used to assess these relationships with a newly collected time series dataset derived from open source news articles. The findings suggest that there is evidence of a relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict and that there is some evidence of strategic looting (compared to opportunistic looting) in these data. These findings also point to both the utility of empirical methods in assessing the relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict and the need for quantitative data that can more accurately capture looting incidents (or attempts) rather than media reports of looting.

1.1. Strategic and Opportunistic Looting in Armed Conflict

Routine activity theory (

Cohen and Felson 1979) and the CRAVED principles (

Clarke 1999) together provide a theoretical framework for why certain objects or places are targets for illicit activity (e.g., looting) more often than others.

Cohen and Felson’s (

1979) routine activity theory requires that three elements be present for a crime to occur: a motivated offender, the lack of capable guardianship, and suitable targets. Crime is more likely to occur when these three elements are present in time and space. Target suitability includes such things as the aesthetic or material value of the target, how difficult it is to remove (inertia), how exposed or visible the targets is, and how easily accessible a target is to a given offender (

Felson and Clarke 1998).

Clarke’s (

1999) CRAVED principles expand on this idea of target suitability by focusing on the idea that certain objects or natural resources can be considered “hot products.” A “hot product” is any kind of stolen good (including food, animals, and works of art) that is easily Concealable, Removable, Available, Valuable, Enjoyable, and Disposable (i.e., CRAVED) (

Clarke 1999).

Together, these theories can help to explain how archaeological sites are targeted. Archaeological sites often cover large geographic areas, while there are typically few resources available for monitoring. Given their size, archaeological sites are both difficult to police and are typically areas of low priority. Thus, it is difficult to establish guardianship over archaeological sites. These sites also contain a plethora of potentially valuable objects, particularly in a country like Egypt, where cultural heritage is everywhere. According to Mohamed Ibrahim Ali, Egypt’s minister of state for antiquities, “when you dig, you find something” (

Boyle 2014). This makes archaeological sites eminently suitable targets for theft and looting. Finally, a motivated offender is anyone that is able, willing, or trying to commit a crime (

Cohen and Felson 1979). Looting of archaeological sites provides a living for some people (

Matsueda 1998), a way to make extra income for others, or an opportunity to engage in another illegal activity (

Teijgeler 2013), creating a supply of motivated offenders.

As such, the combination of a large number of archaeological sites and objects available with little to no guardianship could create a motivated offender from any person or group in need of a quick and discrete form of funding (

Teijgeler 2013). Particularly when viewed as a source of “hot products”, archaeological sites are suitable targets for any motivated offender. Antiquities are objects that can be looted, transported, and either disposed of into other illicit networks or sold at a high market value with little concern for getting caught. The lack of effective regulation over antiquities looting and trafficking makes them easily disposable (a key element for Clarke in the creation of “hot products”) and makes them effective sources of revenue for funding conflict before and during the fighting (see e.g.,

Ross 2015). Both theories can provide a framework for understanding how antiquities looting can both support armed conflict and be a consequence of armed conflict.

1.1.1. Strategic Antiquities Looting in Armed Conflict

An increase in looting prior to or during a conflict could suggest that one or more parties (ethnic group, terrorist organization, etc.) is selling or trafficking antiquities to acquire funds to support or sustain a conflict or violent action.

4 As mentioned above, it is difficult to maintain guardianship over archaeological sites during times of peace and are even then eminently suitable targets for crime by motivated offenders. In armed conflict, capable guardianship is more difficult to maintain as the priorities of the government shift to address the greatest need. Nationally, archaeological sites are more likely to be overlooked during conflict as local law enforcement are deployed elsewhere (

Teijgeler 2013). Internationally, existing regulations are both easy to bypass and ineffective at stopping trafficking in looted objects during conflict.

With regard to motivated offenders, actors in armed conflicts and trafficking networks intentionally and rationally choose how to finance their actions, using whatever resources are accessible “unless these clash with honestly held religious or ideological positions” (

Passas and Jones 2006, p. 1). They prefer easily acquired objects because these do not require any special skills and are a reliable source of revenue (

Freeman 2011). The choice of archaeological sites and antiquities is strategic and intended to fund current and future activities.

The strategic value of antiquities for conflict financing makes them a suitable target for looting in armed conflict. Antiquities can be seen as a natural resource that is exploited, or what Clarke calls a “hot product” (

Clarke 1999). Although

Clarke (

1999) does not specifically consider “hot products” in the context of conflicts, objects that meet the CRAVED principles would be good resources to exploit for financial needs as conflict is just a specific need. For example, objects that are concealable, removable, available, valuable, and disposable will be most useful in financing an armed conflict.

5 Antiquities are easily concealed, making it easier to get them on the market before the looting is noticed. Looting archaeological sites (i.e., digging holes) does not require any special skills, which makes antiquities easily accessible (

Freeman 2011). The high concentration of potentially valuable objects within archaeological sites makes them a reliable means of acquiring funds. Most important, though, is their value as a commodity and their disposability.

From an organizational perspective, access to large quantities of easily accessible natural resources is a good source of funding. However, not all resources are equally valuable in times of conflict—quick trades or sales are not always possible, so commodities that retain their market value are better sources of funding. Plentiful resources with little market value or a small return on investment are not a good source of funding for conflict because they must be sold quickly. Commodities, like diamonds or antiquities, maintain their market value and have a high return on investment—and are therefore favored because they can be sold or held as needed. Both diamonds and antiquities have thousands of categories, the most valuable of which will have a narrow market. Once they enter the market, higher-end items will be noticed; however, their sale will also have a high return. Lower-end diamonds and antiquities can also be sold in bulk at consistent prices. Both can also be used as currency for illegal goods and services (

Wilford 2003) and are excellent “storage assets” because they retain their market value over time (

Hardouin and Weichhardt 2006, p. 306).

The exact nature of the relationship between natural resources and armed conflict (e.g., predicting the onset of conflict or an increase in the duration of conflict) is debatable and depends on many factors (type and location of resource, degree of ethnic fragmentation in a country, type of conflict, analytic method etc.) (

Ross 2015). For example, “contraband” goods (

Angrist and Kugler 2008), lootable resources (

Lujala et al. 2005;

Ross 2006), and resources capable of increasing rebel “fighting capacity” in civil conflict (

Lujala 2010;

Ross 2012) are more likely to be associated with an increase in the odds of the onset of armed conflict, as well as increasing the duration of conflict. Regardless of whether exploiting or looting resources leads to the onset and/or prolonged duration of armed conflict, using natural resources in an armed conflict is a strategic decision for either side of a conflict. The desired outcome could be control of a contested resource (e.g., oil) or use to increase a group’s fighting capacity (e.g., obtaining weapons, equipment, etc.) (

Andersen et al. 2017). In Syria, both pro-government and opposition groups have engaged in a variety of methods to increase revenue, including archaeological looting, kidnapping, smuggling of basic goods and contraband (drugs), and control of oil production (

Hallaj 2015). The large-scale systematic looting did not occur until after the onset of conflict in May 2012, whereas local looting and the sale of artifacts were an earlier source of funding (

Hallaj 2015). Though it remains unclear if such local looting preceded the onset of the conflict, both local and systematic looting have been strategically used as a revenue source in Syria (

Hallaj 2015).

1.1.2. Opportunistic Antiquities Looting in Armed Conflict

Armed conflict may also increase the extent of antiquities looting by increasing opportunity and altering the perceived risks and rewards associated with engaging in this type of crime. The difficulty in monitoring and protecting archaeological sites during conflict makes it easier for objects to reach the illegal markets. During times of armed conflict, a breakdown in authority can further decrease capable guardianship, which both affects the motivation of the offenders and the suitability of the target. Where prior to conflict the perceived (or actual) cost of committing a crime like looting may have been too high, the decrease in capable guardianship may lower the perceived risk. The aftermath of a terrorist attack or the confusion accompanying a riot or large protest can create a vacuum of social order, decreasing both guardianship and perceived risk. Given the potential existing lack of guardianship, it may also be the case that at an individual level, previously available and more profitable options (legal or illegal) for individuals become unavailable or too difficult to pursue during armed conflict. In such a case, looting would be considered an opportunistic crime with easier access, high rewards, and little to no consequences.

Archaeological sites become suitable (and possibly ideal) targets during armed conflict not only for the ease of access and low perceived cost, but also for the objects themselves. As mentioned above, it takes little skill to loot objects from an archaeological site, making them easily removable. The prevalence of archaeological sites makes them readily available to loot, while the action of looting is difficult to detect. It is easy to fake an object’s provenance (history of ownership), which allows them to move through a gray market (a market that conducts both legal and illegal transactions) to the buyers in legal markets (

Kersel 2006;

Mackenzie 2011;

Proulx 2013).

1.2. Egypt as a Case Study

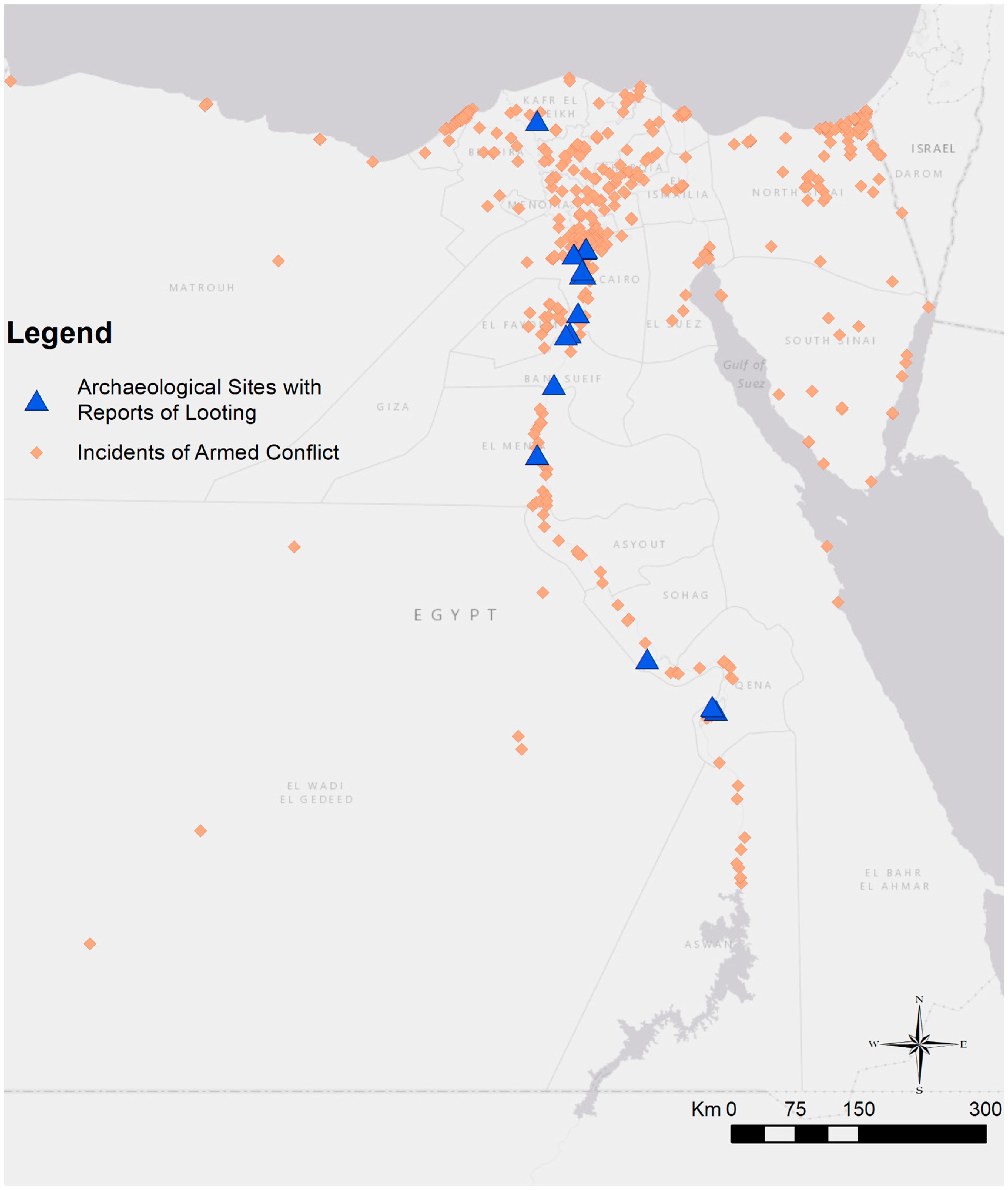

A number of countries in the Middle East with a rich cultural heritage could serve as the case study for this research; however, Egypt has three characteristics that make it a good case study. First, Egypt has a long and rich cultural heritage and is invested in attempting to protect and preserve it. Second, because Egypt is invested in its cultural heritage, it is more likely to report when antiquities are looted, which is essential for data collection. Third, Egypt’s armed conflict events from 1997 to 2014 have relatively well-defined start dates, which are helpful when trying to disentangle the two possible relationships between antiquities looting and armed conflict. This date range covers the end of one armed conflict in Egypt that spanned from 1993 to 1998 and the beginning of a second conflict in Egypt spanning from 2011 to present day. Each reason is discussed in more detail below.

1.2.1. Egypt’s Cultural Heritage

Cultural heritage is everywhere in Egypt and integral to its economic wellbeing. Egypt has a history of preserving its cultural heritage and because almost all the cities are built in the presence of heritage sites, they use the preservation of these sites to their advantage by marketing their history to tourists (

Coben 2011;

UNDP 2016). As tourism makes up a large part of Egypt’s economy, it is in the country’s interest to both preserve the quality and quantity of its cultural heritage. To maintain the quality of the sites, the country periodically shuts down the pyramids to mitigate environmental changes resulting from the press of tourists. For example, the humidity caused by people breathing in a burial chamber can lead to changes in the pH balance of the imagery (

Golia 2014). Egypt has also invested in their cultural heritage by getting them on the UNESCO World Heritage list. Egypt is home to seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites and has another 33 proposed heritage sites under consideration (

UNESCO 2016).

Despite Egypt’s best efforts, the sheer quantity of cultural heritage in the country makes preservation a difficult task. Cultural heritage includes all objects in museums and storage facilities, the great monuments, and antiquities in archaeological sites (both known and unknown). Egypt has numerous archaeological sites, many of which are tourist destinations and while the Ministry of Antiquities has compiled a list of archaeological sites in Egypt, it is not readily available to the public. Egypt also almost certainly has numerous sites that have not yet been identified or discovered. As such, known and unknown archaeological sites contain a plethora of antiquities that are potentially suitable targets for looting.

Egypt is invested in protecting its cultural heritage and has a long history of attempting to protect and preserve its cultural heritage from the destruction of conflict and from looters. Their strategy for reducing the looting of antiquities, especially from archaeological sites, is to pass stricter laws with harsher penalties, increase security measures, and place checkpoints at every Egyptian port (

El-Aref 2005). Unfortunately, there has been no systematic evaluation of these measures, so it is unclear how effective they are.

1.2.2. A Brief History of Armed Conflict in Egypt

This section provides a brief history of armed conflict in Egypt to provide context for the analysis discussed in the next section. Egypt has a long history of multiculturalism and armed conflict tied to tensions between religious groups and non-state actors, particularly between Coptic Christians and Muslim groups (

Kepel 2003;

Murphy 2002). This section focuses only on those events taking place between 1993 and 2014 to provide the context for both conflicts that are partially covered in the time period of the study (1997–2014). From 1993 to 2014, Egypt experienced two major armed conflicts along with scattered incidents of terrorism and unrest, all of which related to changes in the Egyptian Government. Neither conflict is completely contained in the period of study, which may affect the results of the analysis (see below for more information on this).

Starting in the 1990s, the Egyptian Government underwent a massive neoliberal reform, from a primarily state-operated economy to a globalized capitalist system very quickly (

Schwartz 2011, p. 33). While the government was creating a capitalist foundation for the country, it was not advancing Western ideals of equal rights for citizens (

Schwartz 2011). Thus, while Egypt as a country was doing well economically, dissatisfaction with the government was growing from both the Islamist groups and the disenfranchised lower classes of society. Islamist groups took issue with the secular influence of the West on the government and wanted to create an Islamic state (

Schwartz 2011, pp. 33–34). The lower classes and disenfranchised (e.g., women and Coptic Christians) took issue with the lack of rights and fair living wages (

Masoud 2011;

Schwartz 2011, pp. 33–36). From 1993 to 1998, the Egyptian Government was engaged in an intrastate conflict with the al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya. While this conflict ended in 1998, the actions of the al-Gama movement resonated with other Islamist groups like the Tahwid wal Jihad (United and Holy War) that conducted terrorist attacks in 2004–2005 (

Fletcher 2008).

From 2011 to the present day, Egypt has been involved in a period of intrastate armed conflict incidents stemming from the Arab Spring and the uprising in Egypt of 2011 (the “Lotus Revoution”—see

Teijgeler 2013). The Arab Spring began in other countries in 2010, but did not impact Egypt until a year later, when President Hosni Mubarak was ousted as a result of large scale uprisings (involving both the Islamic Group and Coptic Christians) that demanded his resignation (

Masoud 2011). The initial impetus of the uprising involved many, and sometimes contradictory, goals. While both Coptic Christians and Islamist groups called for Mubarak’s resignation, Coptic Christians wanted more equality and higher wages (especially for women). Meanwhile, the Islamist Group disdained the secular government and wanted a return to an Islamic rule (

Bowker 2013;

Gerbaudo 2013;

Masoud 2011;

Schwartz 2011).

From the ousting of Mubarak in 2011 to the Supreme Council of Armed Forces’ (SCAF) assumption of leadership in 2012, Egypt experienced a security vacuum (

Teijgeler 2013). Local law enforcement (including the Tourism and Antiquities Police) disappeared or were released from their duties and thousands of prisoners were released from jails across the country (

Teijgeler 2013). Although the police had mostly returned to their duties by 2012, their enforcement and investigation of looting was at best sporadic (

Teijgeler 2013). The role of the military has been central to the incidents of intrastate conflict as it has consistently had the most power and influence, after the government (

Gerbaudo 2013). They have at times supported the uprisings and at other times suppressed them. The Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) assumed leadership of the government after Mubarak resigned until Mohammed Morsi was elected President in 2012. Morsi was then ousted in a military coup in 2013 due to his inability to find a credible alternative to an Islamic state and perceived ineptitude (

Gerbaudo 2013, pp. 104–5). The former military chief Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has now held the position of President since 2014 (

Basil 2014).

1.2.3. Reports of Antiquities Looting in Egypt

Egypt’s investment in its cultural heritage makes it more likely to report instances of looting, theft, or destruction. It has a long history of reporting to market countries like the United States and international bodies like the International Council of Museums (ICOM) and INTERPOL when its cultural heritage is in danger. Such reports lead to the development of memorandums of understanding prohibiting the import, export, and sale of antiquities from Egypt by individual nations and the issuance of Red Lists of prohibited or stolen antiquities by international bodies (

ICOM 2012). Egypt also reports to news outlets on cultural heritage crimes. From 1997 to 2014, there were 150 news reports in English language outlets that mentioned the looting, theft, destruction, return, or repatriation of antiquities in Egypt. This is likely an underestimate of the number of reports that went to news agencies since it only includes English news sources. Several Egyptian archaeologists and international scholars also continue to try to report individual instances of archaeological looting as they find them.

6 Although this may seem like a small number of reports for a 17-year period, it is still more news reports than other countries, apart from Iraq and Syria (see discussion on data below). The number of news reports in the Arab Spring was more than four times that of all the other years combined, which suggests that media reports will only continue to become more common as time passes. This investment and commitment to reporting events also makes it more likely that news reports contain data that can be quantified. Combined with Egypt’s plethora of antiquities and its clearly defined armed conflicts, this tendency to report events makes Egypt a good choice for a case study looking at the relationship between armed conflict and antiquities looting.

2. Materials and Methods

This study uses a newly collected quantitative data set of reports of antiquities looting incidents at archaeological sites, reports of all armed conflict incidents, and incidents of regime changes in Egypt from 1997 to 2014. These data were compiled from open sources of data, which broadly include any publicly available information that can be coded and quantified into a database. While some scholars have used open source satellite imagery from Google Earth Pro to identify looting pits over time (

Parcak et al. 2016), few studies have evaluated the utility of media reports as a source of data on looting incidents. Satellite imagery has the potential to provide detailed views of a given site over time; however, it also requires knowing where to look beforehand and images may not be available at regular intervals. News stories, by contrast, do not require such prior knowledge, are published at a minimum in daily intervals, and are known to be reliable sources of event data for certain types of crime (e.g., terrorism—see

Dugan and Chenoweth 2013;

Schrodt and Gerner 1994). As such, reports of looting from news sources have the potential to provide a different perspective of looting than satellite imagery that focuses specifically on the timing of events. A brief description of the data is included here (see

Appendix A for a more detailed description of the antiquities looting data collection and coding strategy), followed by a description of the methods used.

2.1. Time Series Data on Antiquities Looting, Armed Conflict, and Regime Changes in Egypt

Reports on incidents of antiquities looting were coded from news stories archived in Reuters and Lexis Nexis. Over 180,000 news stories with the key term “Egypt” were initially downloaded from Reuters and Lexis Nexis combined from 1997 to 2014. News stories were then searched for a series of key terms relating to antiquities looting (see

Table A1 in

Appendix A). All lead sentences (the first sentence description of the article) were coded by hand to remove stories not relating to antiquities looting in Egypt or that were published prior to 1997, resulting in 732 news stories for further review.

These 732 stories were coded based on the entire news story at a minimum for location, type of location (archaeological site, museum, other, no information provided), and incident type (destruction, looting, theft). For an incident to be considered looting, the object(s) had to have been removed from the ground or structural complex of an archaeological site. Since the act of looting often destroys some, if not all, of a site, an incident was only coded as destruction if the main purpose was indicated as destruction and no objects were taken. Similarly, the terms “looting” and “theft” are often synonymous in the media. In this research, an incident could only be coded as theft if the object(s) had been recorded and removed from the archaeological site. For example, an object taken from an archaeological site storage facility is theft because the objects have already been discovered and recorded. There were also several cases that could not be classified as destruction, theft, or looting, and so were coded as “other.” For example, because a storage facility is not within the archaeological complex, it is not considered part of the archaeological site. The exceptions to this are objects physically attached to a structure within the archaeological site. For example, if a part of a statue is removed or part of a mural cut from a wall or tomb, this action would be considered looting even if the object(s) had been identified previously by archaeologists. Below are examples of incidents coded as “looted”, “theft”, and “destruction”. Ultimately, only incidents of antiquities looting that were recorded as occurring between 1997 and 2014 were kept for this analysis, resulting in 91 cases of antiquities looting.

Looting: “Grave-robbers cut away part of a false door bearing painted stone reliefs depicting ceremonial figures and a bronze statue of Horus was also taken” (

Boseley 1997).

Destruction: “a bomb blast destroyed a museum/mosque with Islamic art in it” (

Gauch 2014).

Theft: “Ka-Nefer-Nefer mask from 19th dynasty Egyptian noblewoman stolen in early 1990s from the storage facility near it’s excavation site” (

MO Lawyers Media Staff 2006).

Data on incidents of armed conflict were compiled from two sources of event data: the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ALCED) and the Global Terrorism Database (GTD). Data from the ACLED record information on a variety of political violence incidents in Egypt from 1997 to 2014, including three types of battles, violence against citizens, rioting, protesting, and non-violent events (

ACLED 2015). The GTD records terrorism events from around the world from 1970 to 2014. To be included, an incident must be “an intentional act of violence or threat of violence by a non-state actor” (

LaFree et al. 2015, p. 19). Additionally, incidents are only included if they meet at least two of the following three criteria: (1) the violent act was aimed at attaining a political, economic, religious, or social goal; (2) the violent act included evidence of an intention to coerce, intimidate, or convey some other message to a larger audience(s) other than the immediate victims; and (3) the violent act was outside the precepts of international Humanitarian Law (

LaFree et al. 2015, pp. 19–20). The data from both databases were filtered to include variables on the incident date, country, and location of the incident (at the governorate, city, and site level). The data were cleaned to remove any duplicate events both within and between data sources. In total, there were 5762 incidents of armed conflict in Egypt from 1997 to 2014. During the time period in question, there were several regime changes in the Egyptian government. Such changes can influence both armed conflict and antiquities looting. As such, the study includes a binary variable indicating the occurrence of a regime change. These data came from the Polity IV project, a part of the Integrated Nations Center for Societal Conflict Research’s (INCSR’s) database. The polity data continually track and update on regime changes around the world (

Center for Systemic Peace 2015). Once all data were cleaned and coded, they were aggregated and merged into a month-level dataset and a quarter-level dataset (see

Tables S1 and S2 in the supplementary files). These were the most granular units of analysis for which there was sufficient variation in the antiquities looting and armed conflict variables.

Benefits and Limitations of the Data

These data have several benefits and limitations that are important to discuss. All sources of data used in the current study come from open sources. Open source data have several benefits for studying phenomena that have historically been easier to access through more qualitative methods. First, by virtue of being publicly available, open source data are useful for studying new areas within a discipline like criminology or archaeology. Generally, less data is available on such phenomena because they have not been studied. For phenomena that are considered outside the traditional scope of research, open source data provide a way to look at these new areas. Second, open source data are a cost-effective way to collect data on a wide variety of subjects (e.g., terrorism, see

Dugan and Chenoweth 2013). Online digitization, publishing, and archiving of newspapers, journals, and blogs provides easy access to decades of news articles from media outlets around the globe. Repositories can be specific to a single institution (e.g., Reuter’s archives) or be large databases covering many large and small publications (e.g., Lexis Nexis). Access to these databases through universities or private subscriptions allows researchers to access large quantities of information spanning any subject. For example, the GTD is considered one of the most robust terrorism databases currently in use in criminology (

LaFree and Dugan 2007).

Despite the utility of open source data, the sources used to create these data present some limitations. First, while these data include a relatively large number of regime changes in the dataset, they are still relatively rare in the data, which may affect the findings.

Second and more important to the analysis, the news stories used to create the antiquities looting data contain unavoidable implicit bias. The current study could only capture what the media chose to cover on antiquities looting, which changes over time. This includes what the media considers to be newsworthy, what is of interest to the public, and the means of reporting information. For example, the advent of the Internet made it significantly easier for journalists and amateur reporters to disseminate information. This in turn broadened the range of newsworthy topics, making it more likely that antiquities looting would be reported later in the timeline. Additionally, news stories may lack granularity to get at the actual behavior of interest—antiquities looting. More dramatic or serious cases of looting are more likely to be reported by news agencies, while every day looting may go unnoticed or unreported. As such, the events in the data may disproportionately represent targeted or strategic lootings compared to opportunistic lootings. The current study must also assume that objects have been removed from the sites being reported as “looted,” which may or may not be a reasonable assumption. As such, with these data, the closest this study gets is reports of antiquities looting.

2.2. Methodology

In addition to looking at antiquities looting and armed conflict descriptively, the current study used multiple time series analysis to examine three hypotheses: (1) antiquities looting and armed conflict have a positive statistically significant relationship; (2) an increase in antiquities looting will precede an increase in armed conflict; and (3) an increase in armed conflict will precede an increase in antiquities looting. Specifically, this study uses autoregressive distributed lag models (ARDL) and a bounds testing approach to look at each hypothesis.

ARDL models are designed to look at autoregressive processes, phenomena that are explained in part by their own history and in part by the influence of other factors. In this case, the model allows us to look at the influence of prior incidents of armed conflicts and of looting on current incidents of armed conflict. The basic ARDL model is presented in Equation (1), where

estimate each set of parameters in levels and

estimate the lagged (and/or differenced) parameters that, when combined, create an unrestricted error correction term (

Philips 2018). This combination of estimating the parameters in levels and lags allows for cointegrated relationships and mixed orders of integration between the parameters.

This combination also makes the ARDL model robust in spite of different data structures or orders of integration (i.e., some variables that are I(0) and others that are I(1)), possibly cointegrated relationships, separate lag structures for each variable, and small sample sizes (usually less than 100) (

Pesaran and Shin 1997;

Pesaran and Smith 1998;

Pesaran et al. 2001). Such flexibility in the model makes the ARDL approach suitable for exploratory studies like this one. Another advantage of the ARDL approach is that it is able to differentiate between short-term relationships (dynamics and fluctuations over short time periods) and long-term relationships (permanent relationships over long periods of time) between armed conflict and antiquities looting. The bounds testing methodology developed by

Pesaran and Shin (

1997) and

Pesaran et al. (

2001) was designed to work with mixed orders of integration to determine whether a long-term relationship and cointegration is present between two variables. The combination of ARDL models and a bounds testing approach to cointegration addresses potential issues that can arise from data that have different orders of integration (

Philips 2018). The ability to differentiate between short and long-term relationships and the flexibility of this approach to different data structures makes it an appropriate multiple time series method for analyzing the relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict.

Initial tests of the data revealed that antiquities looting and regime changes were stationary (i.e., both variables were I(0)), but that armed conflict was not (i.e., armed conflict was I(1)). It was also not clear whether or not there were cointegrating relationships among the variables. As such, to analyze the relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict, I had to use a method that could (1) determine whether any cointegrating relationships existed; (2) accommodate mixed orders of integration between the variables of interest; and (3) allow for cointegration in addition to mixed orders of integration, if necessary. At both the month and quarter levels of analysis, the data have small sample sizes (less than 100), which affected the ability of traditional tests to detect cointegration.

Given the complexity of the data, the current study used an ARDL model with the bounds testing approach to analyze the three hypotheses at both the month and quarter levels. It is important to note that running the ARDL model in statistical software (e.g., EViews) requires that either armed conflict or antiquities looting be specified as the dependent variable. As such, the ARDL model was termed with each as the dependent variable. The procedure used for each model is as follows:

Check the stationarity of the variables and determine their order of integration (m).

Use the ARDL model to analyze the relationship with armed conflict as the dependent variable.

Formulate the unrestricted error correction version of the ARDL model in Equation (1) with armed conflict as the dependent variable.

Determine the lag structure of the unrestricted error correction model. This lag structure selects a lag for each of the endogenous variables in the model.

Make sure the model is well-specified (no serial correlation or autocorrelation and the model is stable).

Perform a bounds test for cointegrating relationships.

Repeat Step 3 and all component steps with antiquities looting (or cultural property crime) as the dependent variable.

4. Discussion

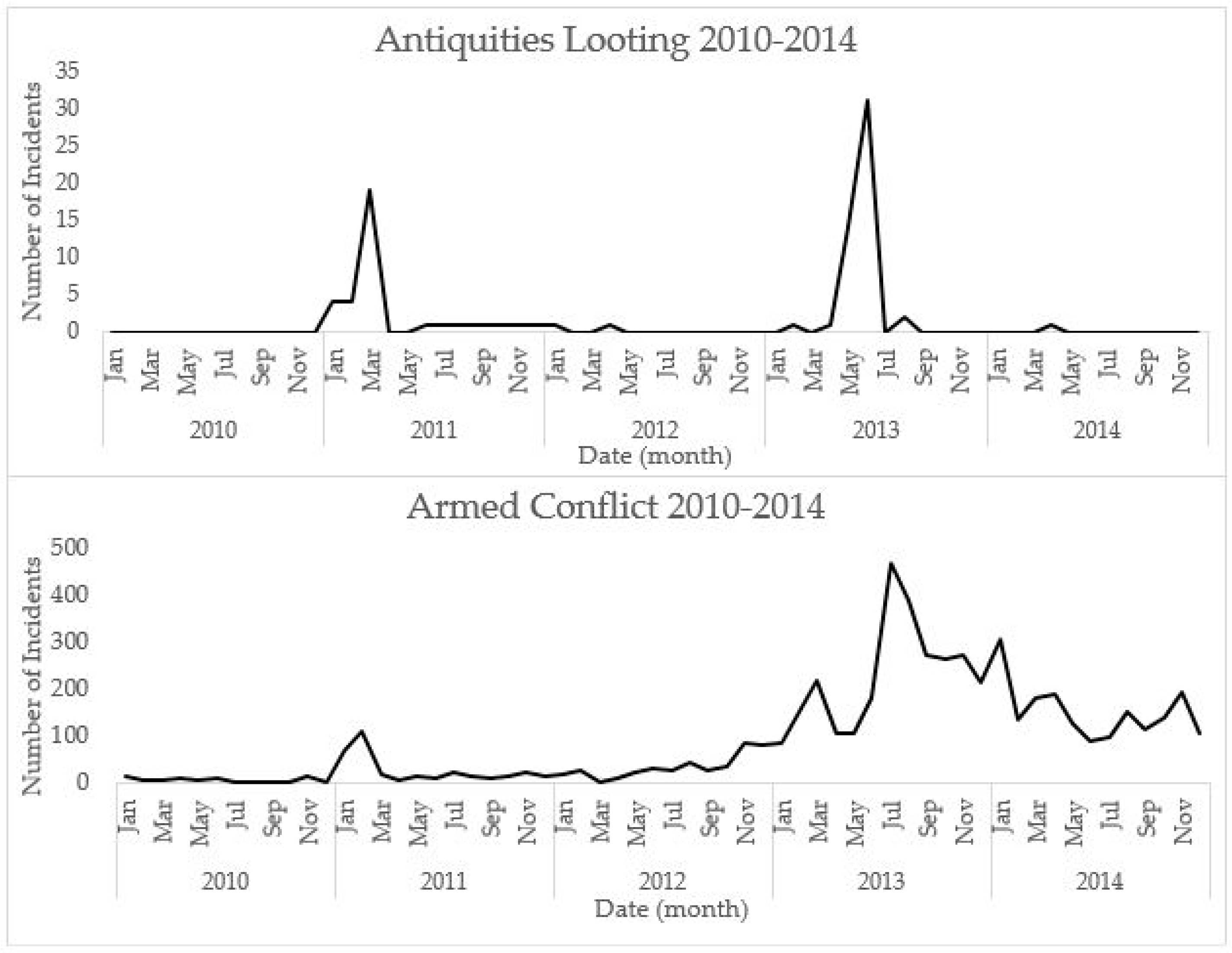

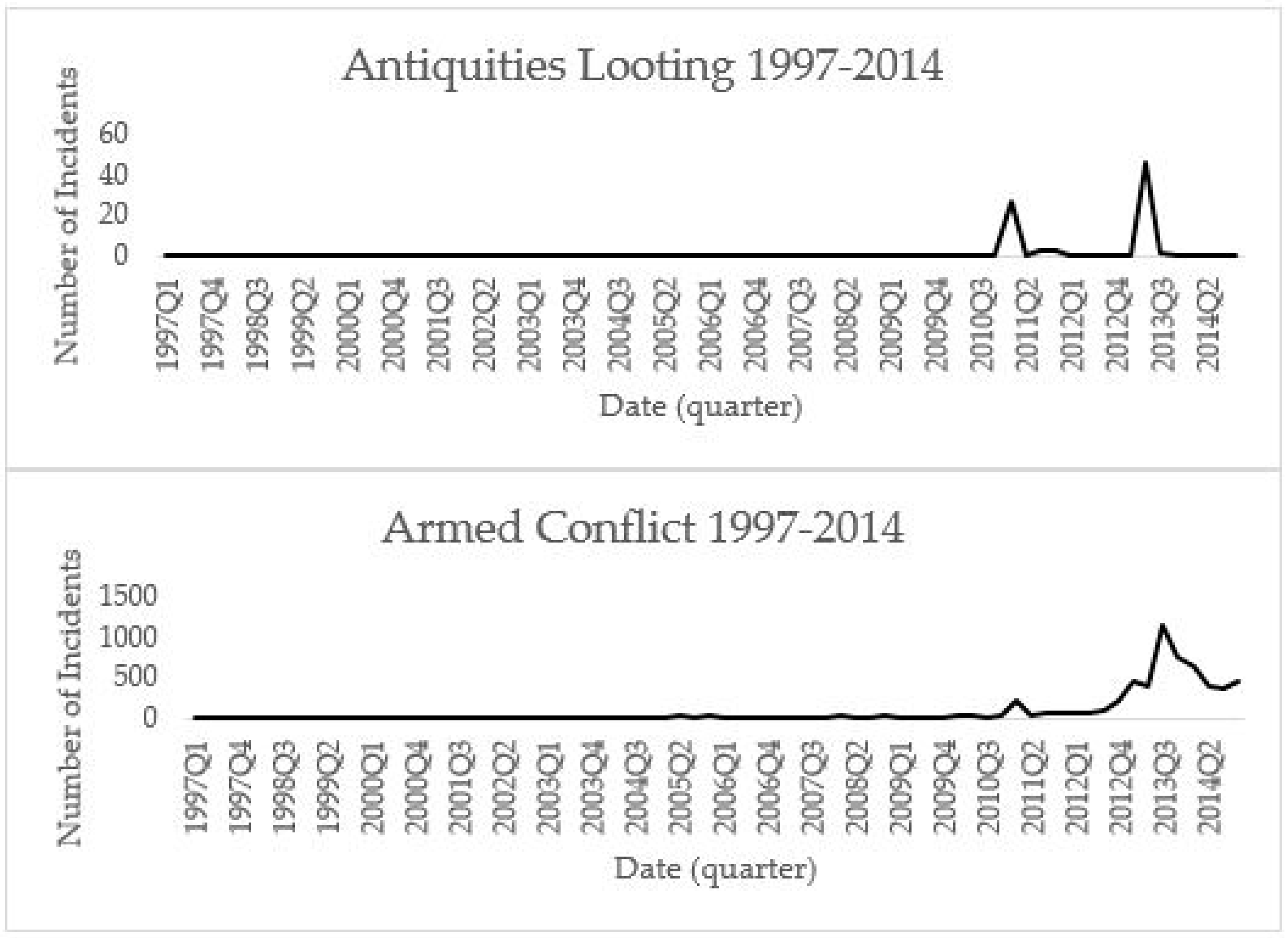

This study makes several important contributions to our understanding of the relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict. First, this study demonstrates the utility of using quantitative data to look at this relationship. Using quantitative data provides the ability to look at the scope of antiquities looting incidents. Egypt, despite its long history of attempting to stop the looting and trafficking of antiquities, has been unable to evaluate the effectiveness of their actions as they do not have any baseline numbers to work from. As these data show, the number of reported instances of antiquities looting in Egypt has increased since 2011 (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Though the data generated for this study are certainly an undercount of the true scope of antiquities looting, they are able to provide an initial look at the frequency of looting over time in more detail than previously established in the literature.

Prior evidence of any relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict has been journalistic or based on case studies tracing the path of looted objects to the market (e.g.,

Baker and Anjar 2012;

Mackenzie and Davis 2014). Quantitative methods like multiple time series complement these qualitative methods in two ways. First, they make it possible to look at whether a relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict can be supported with empirical evidence. Second, they make it possible to see if the relationship is true over time. The results of the above provide both evidence for an empirical relationship over time and a start towards understanding more of the nuances to this relationship. While the results should be viewed cautiously given the exploratory nature of this study, they demonstrate the type of information that can be gained from quantitative data.

Relatedly, the results above speak to the quality of data that can be extracted from open source news stories on antiquities looting. Of the over 180,000 new stories reviewed, only 732 could be coded for antiquities looting incidents (see

Appendix A for details). In total, only 91 incidents of antiquities looting were coded from 1997 to 2014. A 2013 survey of archaeologists found that archaeologists reported that over 50% of archaeological sites had experienced looting to some degree (

Proulx 2013). Journalistic evidence (existing media portrayals, qualitative case studies) and satellite imagery confirm that antiquities looting is not a rare event (

Manacorda and Chappell 2011;

Parcak 2009). As such, a total of 91 instances of looting over a 17-year period (most concentrated from 2010 to 2014) is unlikely to be an accurate representation of the frequency or scope of looting. Open source reports of looting in news stories are useful as a first step in looking at the scope of antiquities looting; however, they are not as reliable a source of information as they are for other types of crime, like terrorism (

Dugan and Chenoweth 2013;

Schrodt and Gerner 1994). The lack of support for opportunistic looting (Hypothesis 3) may be in part due to this underrepresentation. The lack of variation that results introduces measurement error into the analyses, which affects the stability of the model and our ability to trust the results when antiquities looting is the dependent variable (as an independent variable, this is less of an issue).

A third contribution of this study is its attempt to disentangle strategic antiquities looting from opportunistic antiquities looting. While this study is not able to establish causality, the hypotheses address two of the three necessary components to establish causation: (1) a statistically significant relationship; (2) temporal ordering; and (3) alternative explanations (

Mill 1882). While this study cannot address alternative explanations, the first hypothesis directly tests whether a positive relationship exists between antiquities looting and the remaining two hypotheses look at two different temporal orderings of events.

The results indicate moderate support for the first hypothesis, moderate support for one temporal ordering (antiquities looting preceding armed conflict), and weak support for the other temporal ordering. While the results do not provide sufficient detail on the direction of the relationship (positive or negative), they do provide strong support for a statistically significant relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict through the presence of cointegration. This is an important finding as it is the first such empirical evidence in the literature and provides a baseline for future research. However, by itself, this finding does not tell us anything about the temporal ordering of the relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict.

The second and third hypotheses focus on the temporal ordering of events, which is the second criteria for causality. Evidence for antiquities looting preceding armed conflict could suggest that the looting was strategic and could be associated with an armed conflict financing argument. By contrast, evidence for armed conflict preceding antiquities looting could suggest that the looting was opportunistic and a result of the breakdown in social order. These temporal orderings are not necessarily mutually exclusive as both could potentially occur during an armed conflict by different groups. This study found some evidence for both temporal orderings; however, the results for the strategic angle were stronger than for the opportunistic angle. These are important findings for several reasons. First, this is the first study to be able to look at temporal ordering, and while these data have limitations, the results suggest that it is important to distinguish between strategic and opportunistic looting. Second, when combined with the empirical evidence of a relationship, this study can partially look at causality, which has not been attempted before. Third, these results provide an important direction for future research.

4.1. Limitations

Despite the importance of the findings from this study thus far, several important limitations must be discussed. First, this study looks at armed conflict incidents within Egypt’s borders and that related only to Egypt. Egypt’s geo-political context from 1997 to 2014 may share some characteristics with other nearby countries (e.g., being influenced by the Arab Spring); however, the intra-country conflict in Egypt developed according to its unique geographical, political, economic, and cultural pressures. As such, any findings from this study cannot and should not be generalized to other countries.

Second, as mentioned above, this study is not able to get at causality as it cannot rule out several alternative explanations (see below). As an exploratory study, this is not a significant limitation. However, it does mean that the results should be interpreted with caution and should not be taken as evidence of a causal relationship. That is, the results of this study do not conclusively prove that increases in antiquities looting will lead to an increase in armed conflict as a funding mechanism.

Third, one of the main limitations with open source data is that it is not possible to differentiate between changes in reporting trends and patterns in the underlying antiquities looting behaviors. The current data can only speak to reporting behaviors. Without another source of data on antiquities looting to corroborate the timing of the looting incidents reported by the news, it is not possible to know for certain whether reporting behaviors align with underlying looting behaviors.

Fourth, this analysis is not able to distinguish between different types of strategic or opportunistic looting. For example, it cannot distinguish between looting that leads to the onset of a conflict from looting that prolongs an existing conflict. As the focus of this study is on attempting to disentangle temporal ordering more broadly, this limitation does not affect the conclusions presented above. Rather, the findings here speak to any looting that precedes any incidents of armed conflict and vice versa, regardless of whether they are part of a broader prolonged conflict. However, not accounting for the variations in each non-mutually exclusive category of looting does limit what can be learned about the relationship between these two phenomena and may be masking the true relationship.

Finally, the findings of this analysis may not be unique to antiquities looting. It was not possible to account for the influence of crime in general on this relationship as no country-level crime rate statistics were available for Egypt from 1997 to 2014. This is a significant limitation. The findings could reflect a unique relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict, but they could also reflect the broader relationship between crime in general and armed conflict. Armed conflict creates opportunities for crime to occur and transforms existing criminal opportunities. For example, looting behaviors (of electronics, destruction of property, etc.) often occur in violent conflicts (

Mac Ginty 2004). Existing criminal opportunities and markets are also affected by armed conflict. Drug cultivation and distribution is both fostered and transformed by armed conflict (

Cornell 2007). The lack of social order allows such markets to continue to operate; however, their methods of sales and distribution have to adapt as the market shapes and adapts to the conditions of conflict (

Cornell 2007). Crime also affects and shapes armed conflict through a crime-rebellion nexus (

Galeotti 1998). Organized crime can affect rebellions by pitting sides of conflicts against each other, particularly in countries where criminal markets are entrenched in their social and political history (

Galeotti 1998;

Makarenko 2004). Controlling for crime in general, including organized crime and street crime is important to understanding the relationship between armed conflict and antiquities looting. Without the ability to control for crime in general, this study cannot rule out the possibility that the relationship between armed conflict and antiquities looting is spurious.

4.2. Future Directions

The findings, particularly with regard to opportunistic looting, suggest that open source news articles may not be able to capture accurate enough information on looting incidents to provide a comprehensive picture of the situation. As such, alternative sources of data should be considered and utilized in empirical analysis. Satellite images of archaeological sites may be a useful source of data. Research has shown that it is possible to calculate the number of looter tunnels within a single image and to estimate the probability that an object was taken based on the depth of the hole (see

Cunliffe 2014;

Parcak 2009). If images were taken frequently enough, it would be possible to estimate the changes in antiquities looting over time with more precision than news stories allow.

Additionally, the current study is only able to look at armed conflict as a general category; however, the relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict may vary according to the type of conflict. For example, it may be more likely that antiquities are looted to support terrorism than they are to support a riot or a protest. Terrorist attacks typically require planning and the resources to put the plan in motion. Looting antiquities to sell could provide the funds necessary for the attack. Riots and protests may be more spontaneous with less planning involved and so would not need or have time to loot antiquities to sell for funds. As such, future research should look at the relationship between antiquities looting and different types of armed conflict. Relatedly, the current study cannot differentiate between whether antiquities looting affects the start of an armed conflict or sustains an ongoing armed conflict. Yet, it is possible that antiquities could be strategically looted to start a conflict, as well as to provide additional resources for an ongoing conflict. These two types of strategic looting may be associated with different types of conflict or it may be that different actors in the conflict would engage in looting to initiate versus sustain a conflict. Future research should try to differentiate between these two effects.

Finally, future research should address the alternative explanations that could not be accounted for in this study. For example, economic stress in a country may make it more likely that it will experience armed conflict and that people will engage in opportunistic looting. Economic stress is one factor that, when combined with other factors like a vacuum of governance, can lead to a failed state (

Cohen and Felson 1979). In Egypt, such stress could result from a draught affecting the portion of the gross domestic product associated with agriculture. In turn, failed states are more likely to experience armed conflict. Similarly, economic stress in a country may be the result of a lack of economic opportunity. If people are unable to make a living wage in a legitimate business (e.g., farming), they may then turn to looting antiquities to obtain a steadier supply of income. Such alternative explanations should be explored in future research.

5. Conclusions

This study sought to better understand the relationship between armed conflict and antiquities looting using a newly created quantitative data set and empirical analysis. Open source news stories were used to create a time series dataset of reports of antiquities looting and armed conflict. Then, using autoregressive distributed lag models and a bounds testing approach, the study analyzed the data with respect to three hypotheses: (1) antiquities looting and armed conflict are positively related; (2) an increase in antiquities looting is associated with an increase in armed conflict; and (3) an increase in armed conflict is associated with an increase in antiquities looting. The first and second hypotheses received moderate support; however, the third hypothesis received weak support.

Several findings are worth highlighting. First, looting in the month or quarter prior seems to be associated with a positive change in incidents of armed conflict, which could either be an increase in the magnitude of armed conflict incidents or the beginning of armed conflict. Second, while the analyses did not support the hypothesis that increases in armed conflict are associated with an increase in antiquities looting, this does not mean opportunistic looting does not occur. Rather, this suggests that these data are not able to capture this type of looting. Third, despite the limitations in the data, these analyses demonstrate the value in using quantitative data. They allow for a more nuanced analysis of the relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict that could complement individual case studies or journalistic evidence. They also enable the use of quantitative methods such as multiple time series. Finally, this research emphasizes the importance of using quantitative methods to better understand this relationship. Though this research is an initial attempt to apply empirical analysis, the findings are significant and provide a baseline and direction for future research.

Based on this study, future research should be conducted in several areas. First, future research should consider other sources of quantitative data to address the limitations of using open source news stories. Second, quantitative methods should be used to investigate the relationship between antiquities looting and different types of armed conflict. Finally, additional research should be conducted to account for alternative explanations to try to get at a causal relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict.