Anime Landscapes as a Tool for Analyzing the Human–Environment Relationship: Hayao Miyazaki Films

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Landscape

1.2. The Relationship between Landscape and Cinema (Anime)

1.3. What Is Anime?

1.4. Hayao Miyazaki’s Films: His World View and Approaches to Anime

“We need courtesy toward water, mountains, and air in addition to living things. We should not ask courtesy from these things, but we ourselves should give courtesy toward them instead.”(Miyazaki, as cited in Mayumi et al. 2005, p. 3)

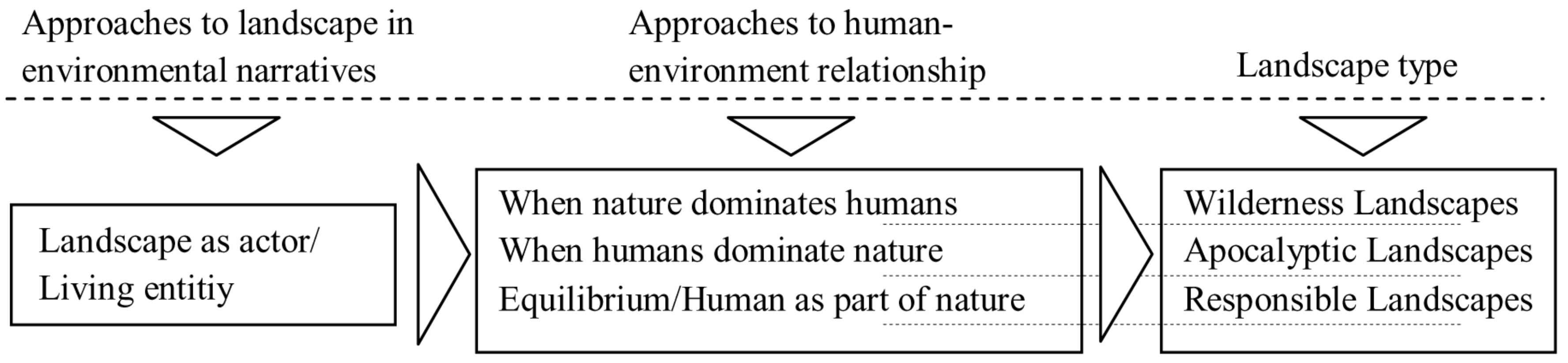

1.5. Analyzing the Human–Environment Relationship through Animated Landscapes: Landscape as Actor and Living Entity

2. Methodology

2.1. Human–Nature Power Relations Approach

2.2. Landscape Types and Definitions

2.2.1. Wilderness Landscapes

2.2.2. Apocalyptic (Dystopian) Landscapes

2.2.3. Responsible Landscapes

2.3. Information on the Films That Will Be Analyzed

2.3.1. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (Japanese Title: Kaze no tani no Naushika)

2.3.2. My Neighbor Totoro (Japanese Title: Tonari no Totoro)

2.3.3. Princess Mononoke (Japanese Title: Mononoke Hime)

3. Results

3.1. Wilderness Landscapes: Forests of Miyazaki

3.2. Apocalyptic Landscapes: Sites of Tension and Destruction

3.3. Responsible Landscapes: Flowing with Nature’s Rhythm

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aitken, Stuart C. 1991. A Transactional Geography of the Image-Event: The Films of Scottish Director, Bill Forsyth. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 16: 105–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, Stuart C., and Deborah P. Dixon. 2006. Imagining Geographies of Film. Erdkunde: Archiv furWissenschaftliche Geographie 60: 326–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, Miklos, and Stefan Drews. 2015. Nature as relationship partner: An old frame revisited. Environmental Education Research 21: 1056–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhill, David L. 2010. Surveying the Landscape: A New Approach to Nature Writing. Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 17: 273–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigell, Werner, and Cheng Chang. 2014. The Meanings of Landscape: Historical Development, Cultural Frames, Linguistic Variation, and Antonyms. Ecozon@ 5: 84–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow, Susan. 2005. Technologies of Perception. Master’s thesis, York University, Toronto, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow, Susan. 2009. Technologies of Perception: Miyazaki in Theory and Practice. Animation 4: 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, Giuliana. 2002. Atlas of Emotion. Journeys in Art, Architecture, and Film. New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro, Dani. 2006. The Animé Art of Hayao Miyazaki. Jefferson: McFarland & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Melanie. 2015. Environmentalism and the Animated Landscape in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) and Princess Mononoke (1997). In Animated Landscapes History, Form and Function. Edited by C. Pallant. New York: Bloomsbury, pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2004. European Landscape Convention—Explanatory Report. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16800cce47 (accessed on 8 March 2018).

- Crist, Eileen. 2004. Against the social construction of nature and wilderness. Environmental Ethics 26: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curti, Giorgio Hadi. 2008. The ghost in the city and a landscape of life: A reading of difference in Shirow and Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 26: 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, Wimal. 2010. Landscapes of meaning in cinema: Two Indian examples. In Cinema and Landscape. Edited by Graeme Harper and Jonathan Rayner. Bristol: Intellect, pp. 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Dürbeck, Gabriele. 2012. Writing Catastrophes: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on the Semantics of Natural and Anthropogenic Disasters. Ecozon@ 3: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Flint, Courtney G., Iris Kunze, Andreas Muhar, Yuki Yoshida, and Marianne Penker. 2013. Exploring empirical typologies of human–nature relationships and linkages to the ecosystem services concept. Landscape and Urban Planning 120: 208–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greider, Thomas, and Lorainne Garkovich. 1994. Landscapes: The Social Construction of Nature and the Environment. Rural Sociology 59: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, Graeme, and Jonathan Rayner. 2010. Introduction-Cinema and Landscape. In Cinema and Landscape. Edited by Graeme Harper and Jonathan Rayner. Bristol: Intellect, pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, Keith. 2007. Aspects of Wilderness. Theology 110: 110–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivakhiv, Adrian. 2008. Green Film Criticism and Its Futures. Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 15: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijnendijk, Cecil C. 2008. The Forest and the City: The Cultural Landscape of Urban Woodland. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lukinbeal, Chris. 2005. Cinematic Landscapes. Journal of Cultural Geography 23: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayumi, Kozo, Barry D. Solomon, and Jason Chang. 2005. The ecological and consumption themes of the films of Hayao Miyazaki. Ecological Economics 54: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, Bryan. 2001. Considering the Nature of Wilderness: Reflections on Roderick Nash’s Wilderness and the American Mind. Organization & Environment 14: 188–201. [Google Scholar]

- Meades, Allan. 2015. Beyond the Animated Landscape: Videogame Glitches and the Sublime. In Animated Landscapes History, Form and Function. Edited by C. Pallant. New York: Bloomsbury, pp. 269–85. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Robin L., and Joseph Heumann. 2007. Environmental Cartoons of the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s: A Critique of Post-World War II Progress? Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 14: 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naess, Arne. 2005a. Self-Realization: An Ecological Approach to Being in the World. In The Selected Works of Arne Naess. Deep Ecology of Wisdom Explorations in Unities of Nature and Cultures. Edited by Harold Glasser and Alan Drengson. Dordrecht: Springer, vol. X, pp. 515–30. [Google Scholar]

- Naess, Arne. 2005b. The Deep Ecology Movement: Some Philosophical Aspects. In The Selected Works of Arne Naess. Deep Ecology of Wisdom Explorations in Unities of Nature and Cultures. Edited by Harold Glasser and Alan Drengson. Dordrecht: Springer, vol. X, pp. 33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Napier, Susan J. 2001a. Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Napier, Susan J. 2001b. Confronting Master Narratives: History As Vision in Miyazaki Hayao’s Cinema of De-assurance. Positions 9: 467–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, Chris. 2015. Introduction. In Animated Landscapes History, Form and Function. Edited by C. Pallant. New York: Bloomsbury, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Reinders, Eric. 2016. The Moral Narratives of Hayao Miyazaki. Jefferson: McFarland. [Google Scholar]

- Rofe, Matthew W. 2013. Considering the Limits of Rural Place Making Opportunities: Rural Dystopias and Dark Tourism. Landscape Research 38: 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, Fred P. 2013. Seeing and Doing Conservation Differently: A Discussion of Landscape Aesthetics, Wilderness, and Biodiversity Conservation. The Journal of Environment Development 22: 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, Gary. 1990. Practice of the Wild: Essays. San Francisco: North Point. [Google Scholar]

- Stokrocki, Mary L., and Michael Delahunt. 2008. Empowering Elementary Students’ Ecological Thinking Through Discussing the Animé Nausicaa and Constructing Super Bugs. Journal for Learning through the Arts 4: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, William M. 2006. Urban disasters: Visualising the fall of cities and the forming of human values. The Journal of Architecture 11: 603–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevenin, Benjamin. 2013. Princess Mononoke and beyond: New nature narratives for children. Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture 4: 147–70. [Google Scholar]

- Thwaites, Kevin, and Ian Simkins. 2007. Experiential Landscape: An Approach to People, Place and Space. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tomos, Ywain. 2013. The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii. Ph.D. dissertation, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Tschida, David A. 2004. The Crocodile Hunter, the Jeff Corwin Experience, and the Construction of Nature: Examining the Narratives and Metaphors in Television’s Environmental Communication. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Walliss, John. 2014. Apocalypse at the millennium. In Millennialism and Society: End All Around Us: The Apocalypse and Popular Culture. Edited by John Walliss and Kenneth G. C. Newport. London: Equinox, pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, Roslyn. 2009. “The Shadow of the End” The Appeal of Apocalypse in Literary Science Fiction. In Millennialism and Society: End All Around Us: The Apocalypse and Popular Culture. Edited by John Walliss and Kenneth G. C. Newport. London: Equinox, pp. 173–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Lucy. 2005. Forest Spirits, Giant Insects and World Trees: The Nature Vision of Hayao Miyazaki. Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 10: 3. Available online: http://www.usask.ca/relst/jrpc/art10-miyazaki-print.html (accessed on 8 March 2018).

- Yamanaka, Hiroshi. 2008. The Utopian “Power to Live” the Significance of the Miyazaki Phenomenon. In Japanese Visual Culture: Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime. Edited by Mark W. MacWilliams. New York: M.E. Sharpe, pp. 237–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, James, and Nancy Buffington. 2007. Miyazaki’s Monsters (Pdf). Available online: http://www.stanford.edu/~njbuff/conference_winter07/papers/james_yang.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2018).

- Yokohari, Makoto, and Jay Bolthouse. 2011. Keep it alive, don’t freeze it: A conceptual perspective on the conservation of continuously evolving satoyama landscapes. Landscape and Ecological Engineering 7: 207–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, Sayoko. 2007. Exploration of the Japanese Individuation Process Through a Jungian Interpretation of Contemporary Japanese Fairy Tales. Ph.D. dissertation, California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka, Shiro. 2008. Heart of Japaneseness: History and Nostalgia in Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away. In Japanese Visual Culture: Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime. Edited by Mark W. MacWilliams. New York: M.E. Sharpe, pp. 256–73. [Google Scholar]

| Landscape Type | Name of the Film | Name of the Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Wilderness Landscape | Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind | Fukai (Sea of Decay) |

| Princess Mononoke | Shishi Gami’s forest | |

| Apocalyptic Landscape | Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind | Destroyed human settlements and war scenes |

| Princess Mononoke | Shishi Gami’s forest (the death of Shishi Gami) | |

| Tataraba (the Iron Town) | ||

| Responsible Landscape | My Neighbor Totoro | Totoro’s forest and surrounding settlements |

| Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind | The Valley of the Wind |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mumcu, S.; Yılmaz, S. Anime Landscapes as a Tool for Analyzing the Human–Environment Relationship: Hayao Miyazaki Films. Arts 2018, 7, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7020016

Mumcu S, Yılmaz S. Anime Landscapes as a Tool for Analyzing the Human–Environment Relationship: Hayao Miyazaki Films. Arts. 2018; 7(2):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7020016

Chicago/Turabian StyleMumcu, Sema, and Serap Yılmaz. 2018. "Anime Landscapes as a Tool for Analyzing the Human–Environment Relationship: Hayao Miyazaki Films" Arts 7, no. 2: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7020016

APA StyleMumcu, S., & Yılmaz, S. (2018). Anime Landscapes as a Tool for Analyzing the Human–Environment Relationship: Hayao Miyazaki Films. Arts, 7(2), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7020016