Abstract

Dating the late 1000s to the mid-1200s CE, petroglyphs of sandal images are among others that distinguish ancient Pueblo rock art in the San Juan and Little Colorado River drainages on the Colorado Plateau from Ancestral Pueblo rock art elsewhere across the Southwest. The sandal “track” also has counterparts as effigies in stone and wood often found in ceremonial contexts in Pueblo sites. These representations reflect the sandal styles of the times, both plain in contour and the jog-toed variety, the latter characterized by a projection where the little toe is positioned. These representations are both plain and patterned, as are their material sandal counterparts. Their significance as symbolic icons is their dominant aspect, and a ritual meaning is implicit. As a component of a symbol system that was radically altered after 1300 CE, however, there is no ethnographic information that provides clues as to the sandal icon’s meaning. While there is no significant pattern of its associations with other symbolic content in the petroglyph panels, in some western San Juan sites cases a relationship to the hunt can be inferred. It is suggested that the track itself could refer to a deity, a mythological hero, or the carver’s social identity. In conclusion, however, no clear meaning of the images themselves is forthcoming, and further research beckons.

Ancient rock art contains icons or symbols grounded in mythologies and narratives that were once shared among group members by means of oral traditions and rituals. Iconic shapes and visual images condense meanings now lost to us, these pictured components being mere remnants of former ideologies persisting today only in their material forms. In the American Southwest, Ancestral Pueblo rock art in the Four Corners region of the Colorado Plateau dating between ca. 1000s and 1250 CE includes images of sandals or sandal tracks, some of which are distinguished by a jog in the vicinity of the little toe. Contemporary with the rock art, jog-toed and plain sandals icons represented in the archaeological record as wood and stone tablets, not to mention the prototypical sandals themselves, have long been recognized [1,2,3]; [4] (p. 106); [5] (p. 38); [6] (p. 67). This essay plots the distribution of the sandal icon, with a focus on the jog-toed variety, through time and space and explores some of the contexts in which they appear in an attempt to call attention to these figures and establish a basis upon which future work can proceed in order to better understand their significance.

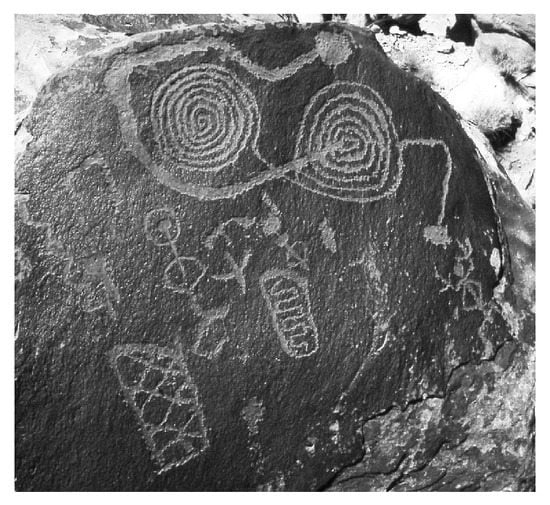

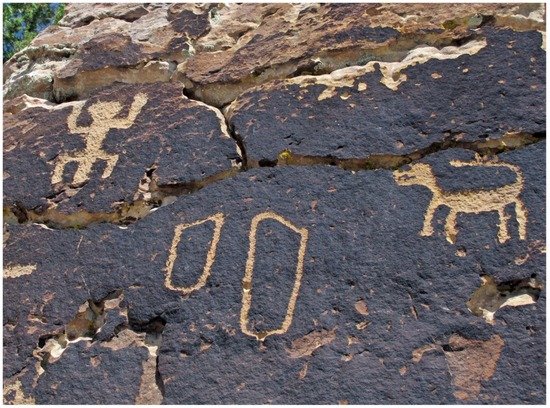

While earlier examples of sandals depicted in rock art exist, they are extremely rare, thus raising the question of whether or not the subjects of this paper represent a new element in the regional ideology or were part of an ancient tradition. Regardless, the sandal image gained importance sometime after the 1000s, and a jog-toed form, distinguished by a protruding bump where the little toe is positioned, became a specialized development (Figure 1). Both plain and jog-toed sandals are visually presented singly, paired (perhaps joined by a line), or on rare occasions in groups. Sandal images of both genres may be enhanced with formal abstract patterns. The images under discussion seldom imply paths or trails, and their significance as stand-alone icons with symbolic content is their salient characteristic. They contrast with petroglyphs of bare footprints that are prevalent in Ancestral Pueblo rock art prior to 1300 CE. The symbolic status of the sandal image in rock art is supported by the miniature, life-size, and greater than life-size effigies in wood or stone from late Pueblo II to mid-Pueblo III sites (ca. 1000–1200 CE) in the San Juan and Little Colorado River drainages, where they are found in kivas or caches associated other ritual paraphernalia (Figure 2). It is surmised that these may have functioned as altar furnishings.

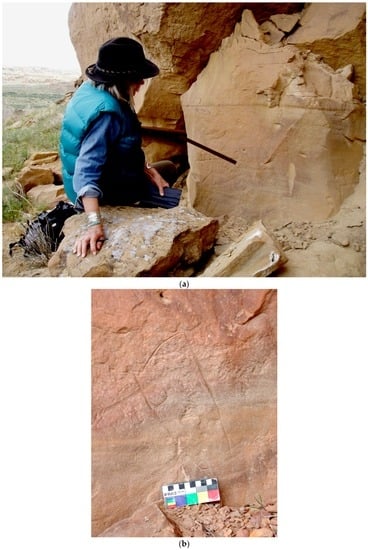

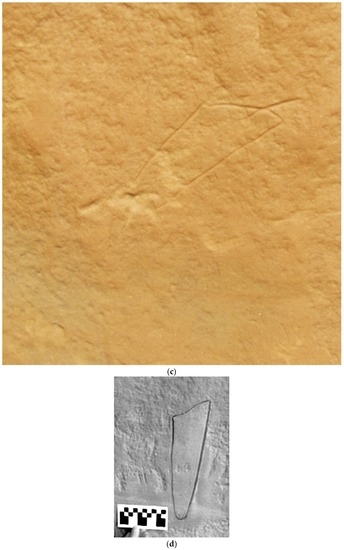

Figure 1.

Incised jog-toed sandal petroglyph, western Mesa Verde region, Utah.

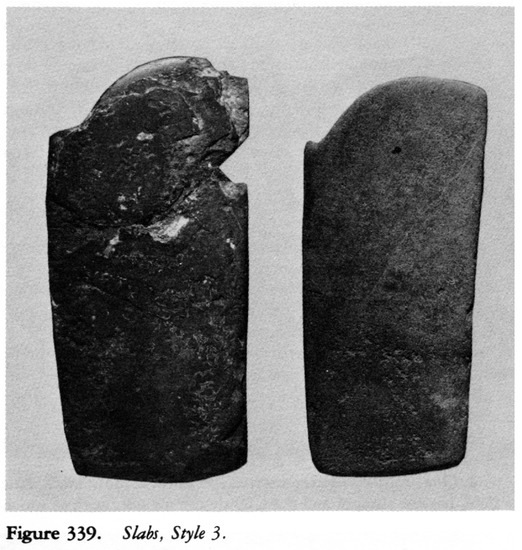

Figure 2.

Sandal stones, larger than life-size. Long House, Mesa Verde. [7] (Figure 339).

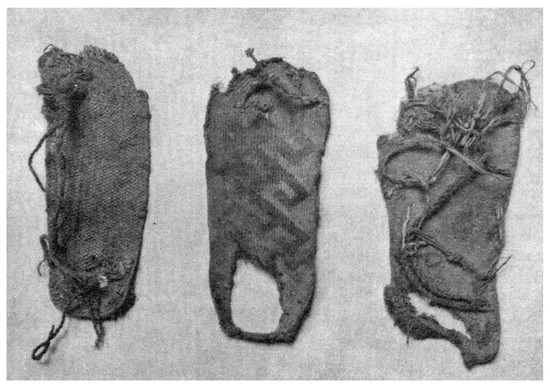

As an element within a rock art context and symbol system that was radically altered after 1300 CE, there is little ethnographic information that provides an insight as to the sandal icon’s meaning. While several potential relationships it might have are offered, no clear interpretation has been reached. Whether the jog-toed as opposed to the plain sandal “track” carries any special symbolic implications remains a moot point. Better woven than their plain counterparts, jog-toed sandal footgear along with the non-jog-toed type were both in general use in the San Juan region around 1200 CE [8] (p. 265); [9] (p. 325); and Figure 3. The common use of jog-toed sandal footgear as documented at Antelope House by Magers argues against any social exclusivity of this sandal type. It is worthy of note, that there are no known examples of the sandal image, much less the jog-toed variety, depicted on/as the foot of a human figure in rock art as if to signify a special status.

Figure 3.

Twined jog-toed sandals, Pueblo Bonito, room 24. [6] (Figure 34.)

1. The Sandal as Graphic Image

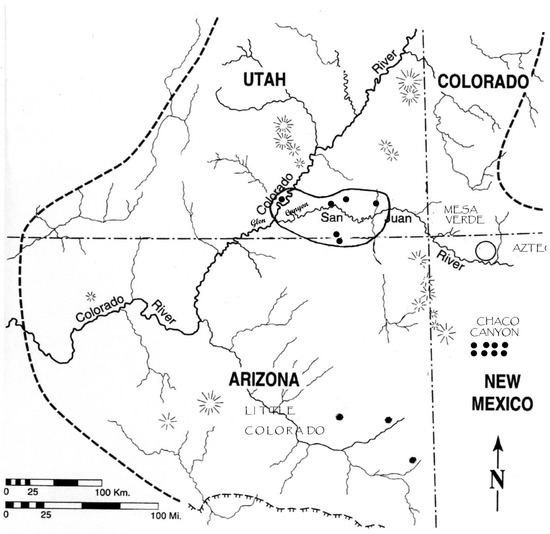

It is important to note that while the sandal image in any form is a relatively uncommon rock art motif, it has been documented from Chaco westward to the right bank of the Colorado River in Glen Canyon as well as in the Little Colorado River drainages (Figure 4). The “jog” itself is a variable feature in the area of the little toe and may vary from a simple flourish or slight flare at the outer edge of the foot in lieu of a normal sloping contour, to an actual sharp upward projection. Both jog-toed and non-jog-toed sandal images frequently occur together, confirming their contemporaneity. At times the presence of a jog is even uncertain, calling into question whether or not the jog-toed version has any special significance.

Figure 4.

Map of Four Corners region of the Colorado Plateau where sandal rock art and effigies occur (Adapted from [10] (Figure 1.4)).

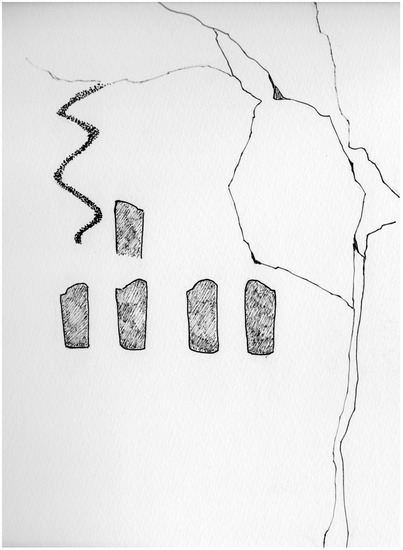

Although commonly obscure, sandal representations are well documented in Chaco Canyon in New Mexico where intensive rock art surveys have been conducted over a period of decades. Most jog-toed examples have been reported from the central part of the canyon, the area with heaviest occupancy [11]. To date, the tight line-up of five carefully ground and abraded jog-toed sandals at the Sombreada site (29SJ400) is the most “formal” representation of these images in Chaco rock art (Figure 5). Characteristically at Chaco, sandal images are not prominent in the panels where they occur. They are often isolated, sporadic depictions, casually incised or even scratched with little investment in time or skill (Figure 6). In some cases, stick figures, flute players, spirals, animals may be pictured on the same rock face, but there is no convincing relationship between the sandal icons and other figures. One pair of well-rendered, linked sandal images lacking the jog is pecked along with spirals in a crack aligned to the setting equinox sun (Figure 7). The significance, if any, of these associations is unknown.

Figure 5.

Jog-toed sandal set, Sombreada talus site, Chaco Canyon. (Drawing by author, adapted from field drawing by Jane Kolber and Jenny Huang).

Figure 6.

Incised single jog-toed sandals from various locations, Chaco Canyon: (a) location near ground level on boulder, near Casa Chiquita; black line points at image; (b) detail: Casa Chiquita sandal; (c) isolated incised sandal; (d) incised sandal: lines enhanced on photo for visibility.

Figure 7.

Pair of pecked sandals in crack lined up with equinox sunset, view to west, Chaco Canyon.

Several of the jog-toed sandal petroglyph sites at Chaco Canyon are located close to “McElmo” style great houses (i.e., Casa Chiquita, Kin Kletso) defined by their blocky masonry construction. Talus unit cliff-side sites with which jog-toed sandal tracks are associated have similar masonry, including the aforementioned Sombreada. Great houses with this type of stone work date between ca. 1110 and 1140 CE [12] (p. 267), and while it may be assumed that the talus unit sites have similar dates [13] (p. 42), little information is available on these architectural complexes at Chaco.

Above the San Juan west of Chaco, casually rendered non-jog-toed sandal petroglyphs were recorded in a detailed survey of Pictured Cliffs above the San Juan River beyond Farmington, New Mexico, one pair of which is embellished with interior designs [14] (Figure 39). As at Chaco, these elements command no particular visual importance within the context of other petroglyphs. Sandal images, usually lacking the jog, are only occasionally seen in Kayenta rock art [15], in Canyon de Chelly, and the central Mesa Verde region, including Hovenweep [16] (Figure 52); [17]. No jog-toed sandal images have been recorded from Mesa Verde itself [18].

In the western Mesa Verde region and in the Glen Canyon vicinity, however, there are several notable sandal sites (Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12; and see [19] (Figure 7.122), and [20] (Figure 48). In Butler Wash, at least thirteen carefully incised, square-heeled sandal silhouettes, both plain and with detailed interior designs, comprise a single panel below a Pueblo III cliff structure (Figure 8). There are two linked pairs in which one sandal is plain, the other decorated. Both sandals in one of these pairs are jog-toed. In other examples, the jog is absent. All are right-footed except for the two left-footed sandals of the paired sets. A pair of hand stencils is present, along with bird tracks and human figure, none of which appear to be in meaningful association with the sandals. The defensively situated rooms above the petroglyphs bear paintings of large concentric circle shields typical of the late thirteenth century sites in that region [21] (pp. 8–27). A baked clay impression of a jog-toed “print” was also found in Butler Wash bearing a patterned design with a scroll at the toe below which follows a series of finely executed interlocking fret patterns [5] (Figure 17). In this case, the patterning resembles that of the incised petroglyphs. It may be from the same site.

Figure 8.

Incised sandal petroglyphs, western Mesa Verde region.

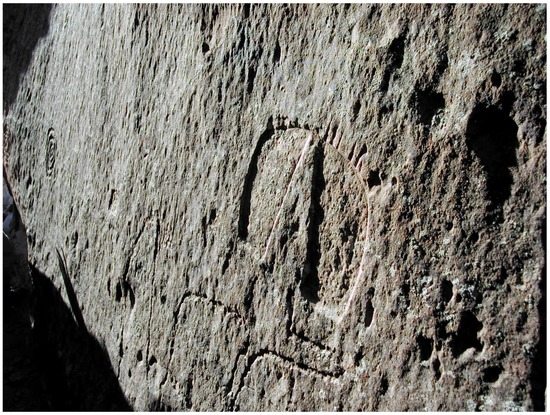

Figure 9.

Two jog-toed sandals, spirals and other motifs, lower San Juan River.

Figure 10.

Possible patterned jog-toed sandal, Oljeto Wash. Utah. (Photograph courtesy of Chuck LaRue).

Figure 11.

Absent hunter panel with jog-toed sandals, bow and sheep, Oljeto Wash, Utah. (Photograph courtesy of Chuck LaRue).

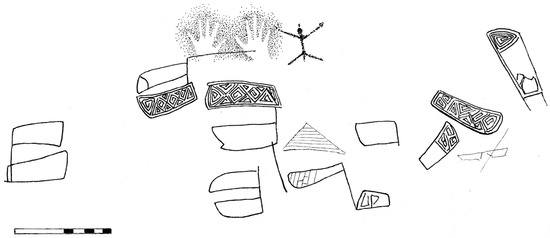

Figure 12.

Petroglyphs along the Colorado River, Buried Olla Site, Smith Fork Bar, Utah. (schematic partial reconstruction after Kolb photograph [22] (p. 158) and Scott File photo [23] (Figure 96), and photograph courtesy of Don Fowler from the Glen Canyon Project, University of Utah).

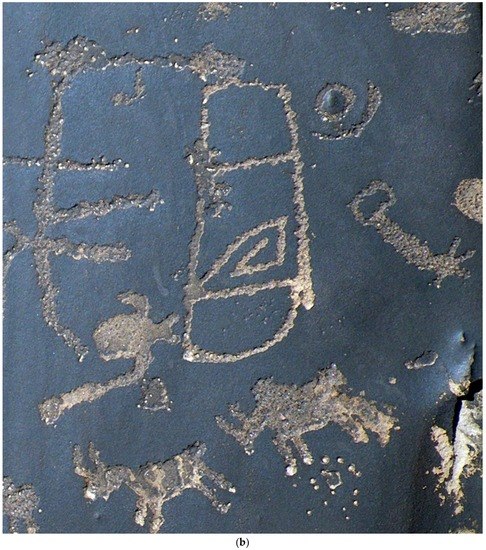

Sandal iconography continues westward down the San Juan. In some sites in the vicinity of Glen Canyon, the sandal images are suggestive of narrative scenes in which they play a symbolic role. Among these is an integrated group in a kind of “symbolic shorthand” featuring a pair of jog-toed sandals that in this case do appear to represent the tracks of an invisible hunter (Figure 11). Slightly above and to the right of the tracks is a bow and arrow aimed at a small bighorn sheep. Below the pair is a third right-footed jog-toed track. This track, however, is not in line with the right foot of the pair, so that a progression of movement is not implicit, or at least the perception of such is thwarted; and in addition, the tracks are separated by a small, solid circle. A small pecked handprint and geometric designs comprise the remainder of the group. Ambiguities notwithstanding, the overall scene suggests that a hunt is in progress. Further west, from a southern tributary of the San Juan in Glen Canyon, in another integrated complex, carefully delineated motifs include two sets of plain and decorative non-jog-toed sandal tracks facing a small solid circle, again with potential narrative implications [20] (Figure 48). Partial views of a third and fourth sandal lead into the scene, and in this case a progression of movement does appear to be indicated.

Also in Glen Canyon on the right bank of the Colorado River, an impressive display of 14 vertically oriented sandal images was recorded at Smith Fork Bar (Figure 12). The site is now under Lake Powell. The sandals represent a Pueblo II-III component of this multi-component site that includes late Basketmaker figures. The sandal images were well executed as independent icons, none being represented in pairs or in progressive sequence. Both right and left feet are depicted, and the toe contour of one is fringed. Among elements appearing contemporary with the sandals are human footprints, meandering lines, a small stick figure, bird tracks, and a line of bighorn sheep that runs through the jog-toed images. At right-hand side of the panel, a hunter points a bow with an arrow surmounted by a sheep toward a single sheep, and possibly the group of sheep near the jog-toed icons were also intended to be included in his hunt, a spatial gap notwithstanding. Equally significant, perhaps, are the lightning-like zigzags pecked along with seven tracks at the upper left. One of these designs resembles a lightning lattice, a wooden artifact found in a cache of wooden artifacts in Chetro Ketl at Chaco [24] (Figure A.38). In one case an elaborate zigzag pattern seems to emerge from a sandal image.

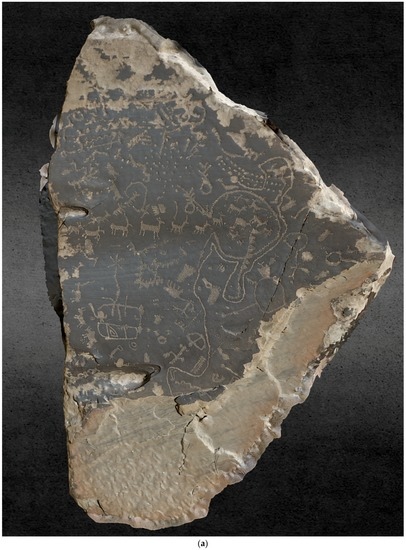

Finally, jog-toed sandal petroglyphs are currently known from three widely separated sites in the Little Colorado River drainage (Figure 13 and Figure 14; see also [25] (Figure 98d). Whereas in every case the image is depicted as an independent element, the occurrence of one of these on a panel in which an extensive animal drive and a bow hunter is portrayed adds to the hunting associations described at least two of the lower San Juan sites.

Figure 13.

Petroglyphs on the Rio Puerco, Little Colorado drainage, Arizona. (a) An animal drive dominates this scene, and a jog-toed sandal is visible on the upper right; (b) Detail of sandal petroglyph (Photographs courtesy of Robert Mark, Rupestrian Cyber Services).

Figure 14.

Petroglyph sandals. Eastern Arizona, upper Little Colorado. (Photograph courtesy of John Pitts).

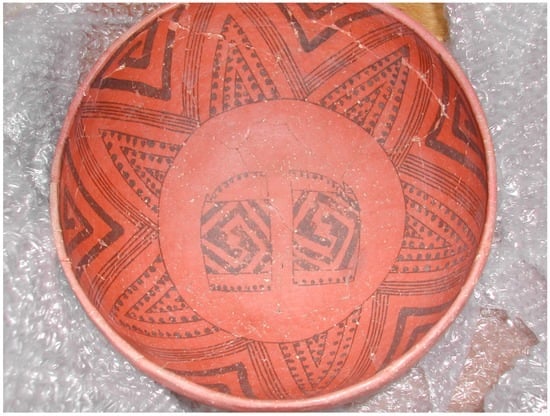

In addition to the petroglyphs, jog-toed sandal images, usually elaborated with geometric patterns were sometimes depicted on ceramics, and more rarely, incised on wall plaster of rooms at Chaco and in the western Mesa Verde region (Figure 15; and [26] (Figures 2 and 6). These contexts provide a means for dating (to be discussed).

Figure 15.

Puerco Black-on-red bowl. (Private collection, provenience unknown).

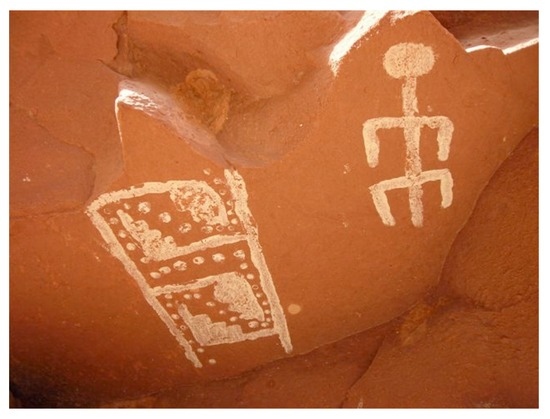

2. Sandal Effigies in Stone, Wood, and Clay

Sandal effigies in stone, wood--thin slabs of stone or wood fashioned as a silhouette of a sandal or sandal track image—or imprinted in clay, are substantial commentary on the importance of sandal symbolism among the Ancestral Pueblos in the Colorado Plateau (Figure 2 and Figure 16). As early as 1919, Kidder and Guernsey observed that sandal stones “are common in the Mesa Verde ruins, and are figured by Fewkes and Nordenskiold, Morley reports them from McElmo, and Professors Cummings and Kidder excavated several on Alkali Ridge, San Juan County, Utah in 1908. Mr. Richard Wetherill states that they occur in Marsh Pass, Chaco Canyon, Grand Gulch, Allen Canyon, and Montezuma County, Colorado” [4] (p. 106).

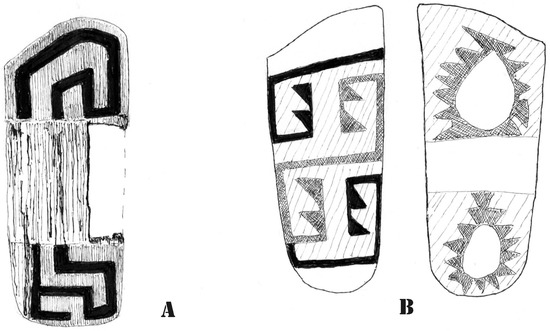

Figure 16.

Painted sandal effigies in wood. (A) Pueblo del Arroyo, Chaco Canyon; (B) both faces of a single sandal effigy from Room 72, West Ruin, Aztec with contrasting designs in black, red, and light green. Note the very slight flare at the little toe. (Drawing by author, adapted from [27] (Plate 145) and [28] (Figure 2C,D).

Sites with sandal stones or wooden effigies—jog-toed or non-jog-toed, include the Escalante Ruin ([29], Figure 21), and sites on Mesa Verde, the La Plata Valley, Aztec, and Chaco and elsewhere [2] (Plate 81); [3] (pp. 20, 142 and Plate 42, h); [4] (pp. 105–6); [5] (Figure 16, center); [6] (p. 67); [7] (pp. 289–90 and Figure 339); [27] (Plate 144); [28]; [30] (Figure 5.23); [31] (Plate 21, j); [32] (Plate29, s); [33] (p. 23 and Figure 10); [34] (Plate. XXXIX); [35] (Figures 309–312; [36] (pp. 241–42 and Figure 286c); [37] (p. 248)). From further west, Osborne reports that no sandal stones are mentioned in the McLloyd and Graham collections largely from the Colorado River above the confluence with the San Juan [35] (pp. 4–5, 481), nor were they reported from Glen Canyon. A plain sandal stone from upper White Canyon, however, extends their distribution to the Colorado River drainage [38] (p. 57 and Figure 49), and this is likely the northwest boundary of the distribution of this artifact. Because of the extensive looting in southeastern Utah, many examples in private collections are thought to derive from this region, adding to the general inventory, although the information surrounding these illegally obtained items is irrevocably lost. Miniature jog-toed sandal stones have been found in association with ceremonial caches in the Rio Puerco and other drainages of the Upper Little Colorado in Arizona (Figure 17). Finally, there are a few tablets of clay into which sandal impressions were made when the clay was soft. From Butler Wash a baked clay tablet with a sandal impression that is slightly jog-toed was described earlier.

Figure 17.

Miniature jog-toed stone sandal effigy, Little Colorado River drainage. (1963 photograph by Myrtle Perce Vivian; courtesy of R. Gwinn Vivian).

Commonly larger than life-size, finely worked, ground stone or wooden sandal effigy tablets in plain or jog-toed shape are characteristic. Although the “sandal stones” were once erroneously tagged as utilitarian “sandal lasts” [27] (p. 132), this idea has been not only questioned, but vigorously challenged and dismissed [3] (p. 142); [4] (p. 105–6); [9] (p. 330); [35] (p. 479–80). Further, their associations with caches of ritual paraphernalia or kivas are documented from Mesa Verde, Chaco, and Aztec sites [3] (p. 20); [39]; [36] (p. 241 and Figure 286); [7] (p. 289). Wooden forms often bore painted decoration comparable to those seen on sandals in rock art. From Aztec two painted wooden sandal forms (at least one of which is jog-toed and with rounded heel) are painted on both sides with geometric designs (Figure 16). Their archaeological contexts in ritual caches and the investment in time represented in their manufacture are testimony to their iconic status and symbolic significance that can be extended to the graphic examples, and their use as altar furnishing is likely.

3. Chronology

The sandal icon seems to have prevailed for at least 200 years among the Plateau Pueblos. Jog-toed sandals may have originated around the time when left and right-footed shaping became a feature of sandal construction, or shortly thereafter, a change that may have occurred around 900 CE [10] (p. 4). While rock art is often extremely hard to date precisely, ballpark dates are relatively easy to estimate, falling well within the Pueblo II–Pueblo III time frame (i.e., 900–1280 CE), although a more restricted time span is currently indicated. Representations in other media provide a more precise guide to dating this sandal iconography (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Chronological data on sandals as symbols.

Square-heeled, jog-toed sandals engraved or chalked in white on room plaster no longer existent were recorded early in the twentieth century in Pueblo del Arroyo, Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl [26] (Figures 2 and 6). These images could have been made during or following the occupation of these rooms. Although contemporaneity with the Bonito Phase occupation (ca. 1050–1130) cannot be assumed, it appears likely however, as architectural details and/or the contents of some of the rooms indicate that they had ceremonial functions [3] (pp. 35, 205–6). If so, the incised imagery may have been made in connection with their ritual importance, thus confirming their Bonito Phase origins. Incised sandals on plaster in Butler Wash appear to be from the 1200s.

Jog-toed sandals pictured on ceramics from the eastern San Juan region and the Little Colorado suggest outside dates between 900 and 1200 CE, with a narrower range between 1030 and 1200 more likely, as summarized in Table 1.

Ritual caches and other contexts in archaeological sites provide also chronological information for jog-toed sandal forms in stone and wood. A jog-toed sandal stone tablet with evidence of yellow paint from the floor of room 16 in BC 50 (Tseh Tso) is potentially among the earliest examples, although this is by no means certain [1] (p. 95 and Plate XIX,b; [40]). A sandal stone is also reported from Mesa Verde (Site 875) dating between 1025 and 1075 CE [41]. In the ritual assemblages at Salmon Ruins and at Aztec, painted and unpainted sandal effigies in wood, with a “jog”, barely indicated only as a slight flourish, date between AD 1100 and 1150 (Figure 16 and Table 1). Jog-toed sandal stones from Long House on Mesa Verde were retrieved from late Pueblo III contexts (see [7] (pp. 409–13), a situation which argues for a late date for the continuing use of these items on Mesa Verde. A ritual use through the Pueblo III period indicates that some rock art examples in the lower San Juan region were probably produced well into the 1200s, the incised jog-toed images in Butler Wash supporting this suggestion.

In Canyon de Chelly and Mesa Verde, jog-toed sandals as footgear were being made through Pueblo III, or into the late thirteenth century [8] (p. 265); [9] (p. 325). At Antelope House in Canyon del Muerto, where a systematic investigation of perishables was conducted, the trend in sandal shape as foot gear was from contoured toes in PII-early PIII (ca. 1000–1150 CE), to contoured with jog-toed in Middle PIII to early Late PIII (1150–1200 CE), reaching a peak around 1200 CE [8] (pp. 264–65) Magers [8] (p. 265) concludes that, “the high proportion of jogged-toe sandals among twined and fine-plaited sandals indicates that toe shape to be particularly common at that time”—primarily, that is, around 1200 CE see also [8] (Tables 113 and 114). Contrary to expectations, however, no sandal stones, were reported from Antelope House [42] (Table 213).

Miniature jog-toed stone effigies associated with ceremonial caches in east central Arizona date largely from 1050–1200 CE, according to estimates made on the basis of the associated ceramics (Figure 17). The dating of a Puerco Black-on-red bowl with paired jog-toed sandal images between 1030–1150 CE [43] (pp. 162–63) is in concert with the cache findings.

In summary, sandal images and effigies appear to have emerged as a significant part of the symbolic repertoire of Ancestral Pueblos in the San Juan and to a lesser extent in the Little Colorado River regions in or by the 1000s and continued at least into the early 1200s. Estimated dates for the sandal stone from BC 50 in Chaco Canyon found in association with Red Mesa Black-on-white sherds likely dates no earlier 1050 or later [40].

4. Contexts and Meaning

The data presented here do not support or negate the suggestion that the sandal-as-symbol complex originated in Chaco, or that the jog-toed sandal style was regarded outside of Chaco as a “high visibility feature” produced in local emulation of Chacoans, although this has been proposed (e.g., [44] (Table 1). Certainly the rock art does not support this notion, and more data are needed to deal with this issue. Recently Crown et al. [45] (p. 445) assert that the jog-toed sandal itself evolved as an accommodation to polydactyly in the form of six toes, a trait characteristic of an early elite burial, although no sandal was found in association. The burial in question (Burial 13 in Room33 in Pueblo Bonito) was recently radio-carbon dated between A. D. 690–877, with a median date of A.D. 781 [46] (p. 19623), dates that precede in time the iconography under discussion.

Nevertheless, a synthesis of foot imagery at Chaco [45] emphasizes the symbolic role of the foot in Ancestral Pueblo ideology during these years, accounting for its presence in the rock art. The symbolic importance of the sandal as a graphic image is also underscored by its replication in other media found within archaeological contexts that indicate it had a ceremonial role. Thus, its representations in rock art can be viewed as part of the symbolic and ritual repertoire or “vocabulary” that prevailed among the Plateau Pueblo peoples throughout the San Juan and neighboring regions during Pueblo II-III times.

Sandal imagery in rock art is rare earlier, although distinctive crescent-toed Basketmaker III sandals (ca. 400–700 CE) are represented as petroglyphs at one site in Sandoval County in northwestern New Mexico. From Juniper Cove on Black Mesa, Arizona, sandal tracks imprinted in oval-shaped fired clay “patties” date from Basketmaker III times [47], and similar findings are reported from elsewhere around the Four Corners). In 1948 McGregor [48] (p. 26) rightfully asked whether or not there was a continuity in tradition between these early clay impressions and the later jog-toed clay imprint from Butler Wash. Did the latter function in the same way, as did the stone and wooden effigies? A systematic review of sandal images from Basketmaker III through the Pueblo period is beyond the boundaries of this paper, although such an investigation might provide some insight into the questions raised here. In no period, however, is sandal imagery as consistently represented as within the Pueblo II–III periods under discussion, with the jog-toed sandal image as a signature feature.

This brief study brings into focus several other unresolved issues. An unanswered question posed early in this discussion was whether or not there is a significant symbolic difference between jog-toed and non-jog-toed sandals? Is the jog simply a stylistic preference or is there a symbolic dimension that contributed to a difference in meaning between the two? And what meaning did these sandals as icons hold for the ancient Pueblo people on the Colorado Plateau? To what did they refer?

Although there is a tendency to treat the jog-toed sandal as a “special” item, the possibility cannot be discounted that any type of sandal icon embodied a similar set of meanings. The physical distinctions are often slight, and both sandal types occur as individual icons for which a symbolic status is indicated. In rock art, paired sandal icons often lack jogs, while on the pottery examples discussed here, the jog is always present. When shown in a progressive sequence suggesting a trail or event, the “track” itself relinquishes its symbolic properties and becomes a means of indicating movement within a narrative. Jog-toed sandals as a rule do not form these sequences. In conclusion, although there tend to be differences in their presentations in rock art, the currently available data do not contribute to a clear picture of potential differences between plain and jog-toed sandal imagery, if any, in their iconographic roles.

As carefully crafted ritual paraphernalia the sandal contrasts sharply with the rock art renditions that are quickly and casually inscribed individually on Chaco cliffs and elsewhere, leading one to speculate on their function as petroglyphs and what meaning they may have held as “public documents” in a cultural landscape. However, even as rock art, the sandal icon is technologically variable and its contexts diverse, leading to the suggestion that the figure itself, although united within a broad conceptual framework, was multivalent in its implications and usage. Such “dynamic ambiguity” is discussed by M. Jane Young [49] (pp. 178–85) in regard to rock art images as viewed by the Zuni. In sites where multiple sandals are depicted, the powers it was perceived to embody may have been increased by its redundancy. Among the Pueblos today, an “aesthetic of accumulation” prevails in many situations. An accumulation of clouds, corn or any other item of positive value is viewed as desirable, and in rock art, multiple images of a positive entity increase the power of what is portrayed (Figure 5 and Figure 12). Continuing on a speculative note, it is proposed that in some contexts the sandal icon may have had social implications, signifying identity or affiliation with a lineage, clan, or moiety. As such the image might have been carved near places of residence of members of the social unit concerned, or even rendered by seemingly “wandering” individuals at Chaco at a favorite spot, much in the spirit of “graffiti”. This could explain the sporadically encountered sandal images casually incised and scratched, where the image lacks any particular link to house structures or a significant landscape feature. In either context, these representations may be accounted for by the idea expressed by the contemporary Zuni, “it is good to have a picture of your clan animal [in this case symbol] around you” [49] (p. 181). Whether or not it had social implications, and this is just speculation at this point, the sandal icon may have been linked in origin via mythology to a powerful supernatural entity including a deified ancestor or culture hero.

While it was hoped that associated elements in rock art might throw light on their meaning, unfortunately, little information along these lines has been forthcoming. In general, elements comprising many rock art panels appear to be independent of each other, and associations appear to be random. At Chaco, flute players and maidens constitute a commonly portrayed fertility complex that may occur near jog-toed sandal images, but this spatial proximity seems more coincidental than intentional.

In contrast with Chaco, the sandal is depicted in fuller iconographic contexts in petroglyph panels in the lower San Juan and Little Colorado drainage, although its function in this rock art may or may not have been different from that in the upper San Juan. As described previously, in panels in the lower San Juan described here, two, including the absent hunter panel, suggest highly abstracted narratives in which the sandal images do take on meaning as tracks (Figure 11 and [20] (Figure 48). Other sites (Figure 12 and Figure 13) in which sandal tracks figure prominently have hunting implications, although in these instances, the sandal image seems to have symbolic rather than narrative significance, possibly invoking a power or entity associated with hunting.

One is then prompted to ask if the association between sandal symbols and the hunt in the westernmost sites is supported by the associations between sandal imagery and tchamahias as described from the La Plata Valley in southwestern Colorado. The Mancos corrugated vessel with seven right-footed jog-toed images impressed into the corrugations was described earlier, and the jar contained two tchamahias, wedge-shaped stones, hornfel celts that have complex ritual roles among the ethnographic Pueblos. Elsewhere in the La Plata valley a sandal stone in a room along with tchamahias [50].

While sandal icons vanished from the archaeological record over 700 years ago, tchamahias persist in ritual contexts today. Noting that sandal iconography and tchamahias shared a similar geographic distribution in the San Juan and that they occurred together in two instances, it is possible to propose that there may have been a symbolic linkage between them. The assumption is that the tchamahia made its debut as a tool functioning as a hoe [51] (pp. 80–81) and later on acquired ceremonial value and served as altar pieces [52] (p. 489). Today among the ethnographic Rio Grande Keres Pueblos and the Hopi, the tchamahia are variously associated with war, the hunt, powers of the four directions, Stone Men, or viewed as “rain knives” [51] (p. 81); [53] (pp. 194–95, 333). The word itself is an honorific Keresan term linked to the War Chief. The association of the sandal petroglyphs with lightning iconography at Smith Fork raises the question of a connection here between sandal stones and the lightning power connected with ethnographic tchamahias. Lightning is viewed as a weapon of the War Gods. Based on the rock art, there is a suggestion that the sandal was associated with hunting powers. Tchamahias on today’s altars are often viewed as a badge of office. Did the sandal stone perform a similar role? (e.g., [54] (pp. 625, 707, 745)).

While taking into consideration the shifts in meaning that must have occurred over centuries, the observations offered here are tenuous but tantalizing, linked as they are by fragile threads of evidence. While the very large discrepancy between the latest dates of the jog-toed sandals and the contemporary symbolic and ritual functions of the tchamahia, cautions against drawing any conclusions at this point based on ethnographic information, these relationships at least provide guidelines for further investigations.

5. Conclusions

This essay has presented a preliminary sketch of the distribution of sandal iconography across the Colorado Plateau and speculated on its potential meanings. Sandal imagery was a distinctive and important component of Ancestral Pueblo symbolism reaching an apex between ca. A.D. 1050 and 1200. As petroglyphs, pottery designs, and ritual objects, the sandal image apparently denotes power, at least in some contexts. Whether it involved a culture hero as a hunter, a deity, or ancestor —real or mythical—or identified social relationships and affiliations, it is proposed that the sandal reproduced as an icon in various media, acquired several possible functions and meanings within different social and ritual contexts. The association of the jog-toe sandal with polydactyly and the questionable extension of this “package” to elite Pueblo rulers, whose supernatural endowments were thought to have been made evident by way of by a physical abnormality—all of which is somewhat dubious—is not necessarily a closed issue. There remain questions. The configuration of the jog-toed sandal—either the sandal itself or its representation—is usually not any wider than the non-jog-toed variety, thereby raising the issue of its use by six-toed individuals. Chronological disparities exist between the Chaco burial in question and the apex of development of the sandal as a symbol. The often-sketchy representations of the jog-toed sandals on Chaco cliffs lack any sense of having been honorific. In contrast, the more elaborate graphic development of the jog-toed and other sandal representations in the lower San Juan indicate that there is no simple or single answer as to its significance.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Nineteenth International Rock Art Conference IFRAO 2015, Caceres, Spain, on the session “Watch Your Step” organized by Jane Kolber and Patricia Dobrez who kindly invited my participation. I am indebted to numerous friends and colleagues who over several years have shared information and otherwise facilitated this work, including Ben Bellorado, Tamara DeRosiers, Jerry Fetterman, Kelley Hays-Gilpin, Dennis Gilpin, Robert Mark, Laurie Webster and Winston Hurst. Jane Kolber and Donna Yoder provided gracious hospitality and guidance in the field in Chaco Canyon. Drawings and photographs are by the author unless otherwise indicated. Additional contributions to the illustrations were generously contributed by Jane Kolber, John Pitts, Chuck LaRue, R. Gwinn Vivian, and Don Fowler. Thank you all!

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Donald D. Brand, Florence M. Hawley, Frank C. Hibben, and Tseh Tso. A Small House Ruin, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Preliminary Report; Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Bulletin 308. Anthropological Series 2(2); 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Neil Judd. The Material Culture of Pueblo Bonito. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 124; Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Neil Judd. Pueblo del Arroyo, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 138(1), Publication 4346; Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Alfred V. Kidder, and Samuel J. Guernsey. Archaeological Explorations in Northeastern Arizona. Washington, D. C.: Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 65, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- W.K. Moorehead. “A Narrative of Explorations in New Mexico, Arizona, Indiana, etc.” In Phillips Academy Bulletin. Andover: Department of Archaeology, 1906, Volume 3, pp. 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- George H. Pepper. Pueblo Bonito. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 27; New York: American Museum Press, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Richard P. Wheeler. “Stone Artifacts and Minerals.” In Long House: Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado; Edited by George S. Cattanach Jr. Publications in Archeology 7H, Wetherill Mesa Studies; Washington: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1980, pp. 243–306. [Google Scholar]

- Pamela C. Magers. “Weaving at Antelope House.” In Archeological Investigations at Antelope House; Edited by Don P. Morris. Washington: National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, 1986, pp. 224–76. [Google Scholar]

- Carolyn M. Osborne. “Objects of Perishable Materials.” In Long House: Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado; Edited by George S. Cattanach Jr. Publications in Archeology 7H, Wetherill Mesa Studies; Washington: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1980, pp. 317–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley Hays-Gilpin, Ann Cordy Deegan, and Elizabeth Ann Morris. Prehistoric Sandals from Northeastern Arizona: The Earl H. Morris and Ann Axtell Morris Collection. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona, No. 82; Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- J. Kolber. Personal communication, 2010.

- Stephen H. Lekson. Great Pueblo Architecture of Chaco Canyon. Albuquerque: Publications in Archeology 18B, Chaco Canyon Studies, National Park Service, New Mexico, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Tom Windes. “House Location Patterns in the Chaco Canyon Area: A Short Description.” In Chaco Society and Polity: Papers from the 1999 Conference. Edited by Linda S. Cordell, W. James Judge and June-el Piper. Albuquerque: New Mexico Archaeological Council, Special Publication 4, 2001, pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Robin Farwell, and Karen Wening. The Pictured Cliffs Project. Santa Fe: Laboratory of Anthropology Notes 299, Research Section, Museum of New Mexico, Santa Fe, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Polly Schaafsma. A Survey of Tsegi Canyon Rock Art. Santa Fe: Manuscript on File, Navajo National Monument, and Laboratory of Anthropology Library, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Sally J. Cole. Legacy on Stone: Rock Art of the Colorado Plateau and Four Corners Region. Boulder: Johnson Books, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy H. Olsen. Hovenweep Rock Art: An Anasazi Visual Communication System. Los Angeles: Occasional Paper 14, Institute of Archaeology, University of California, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sally Cole. Personal communication, 2006.

- Kenneth B. Castleton. Pictographs and Petroglyphs of Utah, Vol. 2 The South, Central, West, and Northwest. Sal Lake City: Museum of Natural History, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Christy G. Turner II. Petrographs of the Glen Canyon Region. Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin 38 (Glen Canyon Series No. 4); Flagstaff: Northern Arizona Society of Science and Art, Inc., 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma. Polly. Warrior, Shield, and Star. Santa Fe: Western Edge Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth Kolb, and Emery Kolb. “Experiences in the Grand Canyon.” The National Geographic Magazine, 1914, vol. 26, 99–184, Washington, D. C. [Google Scholar]

- Polly Schaafsma. Indian Rock Art of the Southwest. Santa Fe and Albuquerque: School of American Research and University of New Mexico Press, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- R. Gwinn Vivian, Dulce N. Dodgen, and Gayle H. Hartmann. Wooden Ritual Artifacts from Chaco Canyon, New Mexico: The Chetro Ketl Collection. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona No. 32; Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Sally J. Cole. Legacy on Stone, 2nd ed. Boulder: Johnson Books, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frances Joan Mathien. “Pueblo Wall Decorations: Examples from Chaco Canyon.” In Climbing the Rocks: Papers in Honor of Helen and Jay Crotty. Edited by Regge N. Wiseman, Thomas C. O’Laughlin and Cordelia T. Snow. Albuquerque: Archaeological Society of New Mexico 29, 2003, pp. 111–26. [Google Scholar]

- Earl H. Morris. Archaeological Studies in the La Plata District. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington, Publication 519, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Laurie Webster. “Perishable Ritual Artifacts at the West Ruin of Aztec, New Mexico: Evidence for a Chacoan Migration.” Kiva 77 (2011): 139–71. [Google Scholar]

- Judith Ann Hallasi. “Archaeological Excavations at the Escalante Site, Dolores, Colorado, 1975–1976, Part II.” In The Archaeology and Stabilization of the Dominguez and Escalante Ruins. Cultural Resources Series, No. 7; Denver: Colorado State Office, Bureau of Land Management, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy J. Aikens. “The Abraders of Chaco Canyon: An Analysis of their Form and Function.” In Ceramics, Lithics, and Ornaments of Chaco Canyon. Edited by Joan Mathien. Santa Fe: Publications in Archeology 18G, Chaco Canyon Studies, Vol. II (Lithics), pp.701-945. National Park Service, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Jesse Walter Fewkes. “Spruce Tree House.” In Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 41. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvanus Morley. “The Excavation of Cannonball Ruins in Southwestern Colorado.” American Anthropologist n.s.10 (1908): 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl H. Morris. “The Aztec Ruins.” In Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. New York, 1919, vol. 26, pp. 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gustave Nordenskiöld. The Cliff Dwellers of Mesa Verde, Southwestern Colorado: Their Pottery and Implements. Translated by D. Lloyd Morgan. Stockholm: P.A. Nortedt and Söner, 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Carolyn Osborne. The Wetherill Collections and Perishable Items from Mesa Verde. Los Alamitos, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur H. Rohn. Mug House: Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado; Archaeological Research Series 7-D, Wetherill Mesa Excavations; Washington: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1971.

- Richard Sandal Stones Wetherill. The Antiquarian. Columbus, Ohio: The London Printing and Publishing Company, 1897, vol. 1, p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- “Hobler, Philip M., and Audrey E. Hobler with an Appendix by Polly Schaafsma.” In An Archeological Survey of the Upper White Canyon Area, Southeastern Utah. Antiquities Section Selected Paper V(13); Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1978.

- Earl H. Morris. “Notes on Excavations in the Aztec Ruins.” In Anthropological Papers. 26 (pt.5); New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- R.G. Vivian. Personal communication, 2015.

- Robert H. Lister. Site 875, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado. Contributions to Mesa Verde Archaeology II; Boulder: University of Colorado Studies in Anthropology No. 11, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Laurence D. Linford. “The Stone Artifacts.” In Archeological Investigations at Antelope House; Edited by Don P. Morris. Washington: National Park Service, US Department of the Interior, 1986, pp. 514–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley Hays-Gilpin, and Eric van Hartsveldt, eds. Prehistoric Ceramics of the Puerco Valley: The 1995 Chambers-Sanders Trust Lands Ceramic Conference. Ceramic Series No. 7; Flagstaff: Museum of Northern Arizona, 1988.

- Paul Reed. “Chacoan Immigration or Emulation of the Chacoan System? The Emergence of Aztec, Salmon, and Other Great House Communities in the Middle San Juan.” Kiva 77 (2011): 119–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricia L. Crown, Kerriann M. Hedman, and Hannah V. “Mattson Foot Notes: The Social Implications of Polydactyly and Foot-Related Imagers at ChacoCanyon.” American Antiquity 81 (2016): 426–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen Plog, and Carrie Heitman. “Hierarchy and Social Inequality in the American Southwest: A.D. 800-1200.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 107 (2010): 19619–19626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton C. Baldwin. “A Basketmaker III Tablet.” Southwestern Lore 3 (1939): 48–52, Boulder, Colorado. [Google Scholar]

- John C. McGregor. “A Clay Sandal Last from Utah.” Plateau 21 (1948): 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- M.J. Young. Signs from the Ancestors. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Laurie Webster. Personal communication, 2007.

- Alden C. Hayes. “A Cache of Gardening Tools: Chaco Canyon.” In Collected Papers in Honor of Marjorie Ferguson Lambert. Edited by Albert H. Schroeder. Papers of the Archaeological Society of New Mexico 5; Albuquerque: Albuquerque Archaeological Society Press, 1976, pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jesse W. Fewkes. “Minor Hopi Festivals.” American Anthropologist n.s, 4 (1902): 482–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsie Clews Parsons. Pueblo Indian Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1939, vol. 2, (Revised, Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London, 2 vols. 1969). [Google Scholar]

- Alexander M. Stephen. Hopi Journal. Edited by E.C. Parsons. New York: Columbia University Press, 1936, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- L.J. Abel. Pottery Types of the Southwest. Flagstaff: Museum of Northern Arizona. Ceramic Series no 3; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- R. Gwinn Vivian, and Bruce Hilpert. The Chaco Handbook: An Encyclopaedic Guide, 2nd ed. Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).