1. Introduction

Australian Aboriginal symbols are visual forms of knowledge that express cultural intellect within a sense of place and spiritual space. With over 350 different Aboriginal Nations in Australia, creative expressions of knowledge are unique to each Aboriginal Nation as designs, symbols, techniques and mediums are bound within customary laws associated to Creational periods. Therefore symbolic markings, lines and patterns remain the intellectual property of that Nation. This article highlights how Aboriginal creativity has little concepts of aesthetical value, but is a cultural display of meaning relating to Creational periods, often labelled as The Dreamings, with a focus on the Dharug Nation, located around the northern Sydney area of NSW. The Dharug term for the Creational period is Gunyalungalung—traditional ritualized customary lores. Our lores are governed within mens and womens business, inscribed through memory and visual literacies (see

Figure 1). These symbols are permanently located within the environment on open rock surfaces, caves and makings on trees. Whilst some symbols are manmade, others are made by Creational ancestral beings and contain deep story lines of information in sacredness. Therefore, creative imagery engraved or painted on rock surfaces are forms of conscious narrative that emphasise deep insight. It is this deep insight of interpretation that allows the free flow of external influences within the environment to transcend into the internal spiritual worlds.

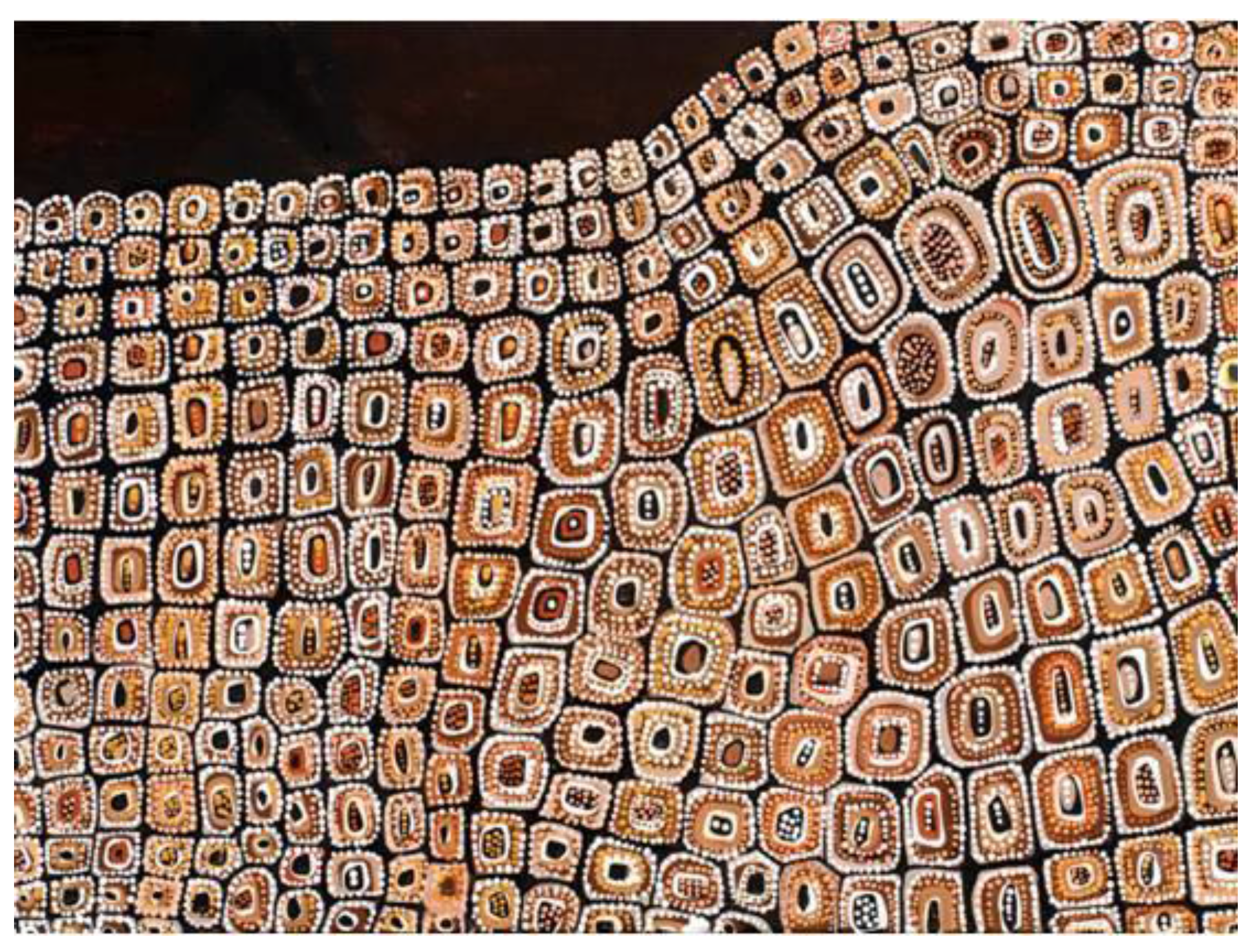

Figure 1.

Gunyalungalung Women’s Business; Natural Ochre’s on paper by Belanjee that illustrate the sacredness within cultural place and spiritual space. Location of cave not disclosed.

Figure 1.

Gunyalungalung Women’s Business; Natural Ochre’s on paper by Belanjee that illustrate the sacredness within cultural place and spiritual space. Location of cave not disclosed.

Classification by a Western interpretation of “art” devalues thousands of years of generational knowledge systems, where visual information has been respected, appreciated, and valued. This article attempts to create an alternative understanding of how the creative form within a cultural framework illustrates knowledge and therefore has little relevance to aesthetic pleasure in viewing, or acquirement within a sense of ownership, but reflects vital information based on living. For example, many symbols located around rock formations contain animal symbols that inform bypassers of what foods may be located within the area.

In validating Dharug Aboriginal visual knowledge, recent research suggests that symbols of cultural content have the ability to connect the external and internal worlds through the unconscious mind (Dow, 1986) as unique visual literacies that Dow terms “semiotic” manipulations. Bakhtien (2000) describes symbolic interpretations as the transition from an image to a symbol, which “makes it semantically deep and gives a semantic perspective” (pp. 381–382). Lawlor (1991) reaffirms such notions: “the image is the vehicle, for the body and presence, of the fertilising power of the Ancestors on earth” (p. 291) that contains deep sacred meanings (Effland, 2002). The ability for symbols to communicate cultural intent is also acknowledged by Kelly, (2008:36), who states that internalised explorations are subjective trans-generational experiences transmitted through “visual symbolism, mental communication, and practice of spirituality that do not separate the sacred and the secular in daily life”. Geertz (1973) also argues that symbols hold significance “of which men communicate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge about and attitudes toward life” (p. 89).

Whilst there is considerable research explaining how symbols are visual literacies and hold semantically deep meaning and perspective, there is little acknowledgement as to how Aboriginal symbols achieve a psychological response and transference from the external image to the internal body. From a Dharug standpoint, the purposeful use of repetitive rhythmical visual form acts as a sensation to the mind and body in connecting individuals to self and the environment. Visual knowledge is therefore the transversal of cultural place to spiritual place. Interestingly Yazzie (1999) also refers to knowledge as “transferences of information from the outside world of nature to the individual self” (p.84). Whilst Yazzie provides an insight of visual knowledge, self within a Dharug concept is not a consideration, as communal involvement is a priority. In elaborating further, self is considered only a piece of knowledge, whereas the collective has ultimate knowledge. The patterning of the environment forms a conscious reminder of our valuable relationships to all living things, see

Figure 2.

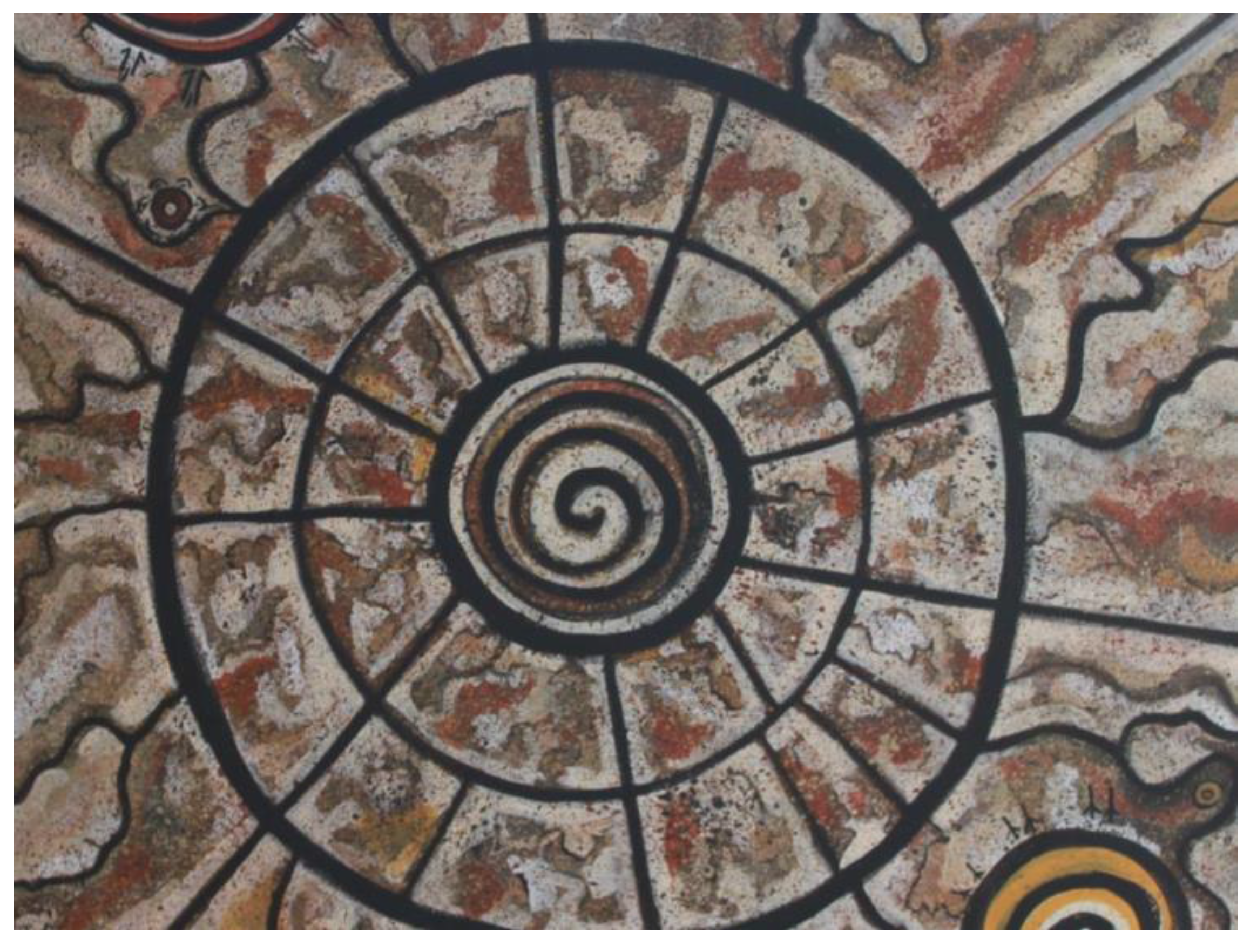

Figure 2.

Acrylic on canvas by Belanjee that illustrates the spiritual relationship of the crocodile within cultural place.

Figure 2.

Acrylic on canvas by Belanjee that illustrates the spiritual relationship of the crocodile within cultural place.

A sense of cultural place within Dharug notions relates to feelings associated with identity that emphasise community belonging. It is a place that is central to Dharug philosophical life purpose, as the concept of land is not connected to self-ownership—rather, it is a state of internal wealth where customary obligations in caring for Country is fulfilled and maintained. Spiritual space provides a sense of purpose to living, and appears through dreams, visions and ancestral guidance. Therefore, Cultural place and Spiritual space are connected to philosophical understanding within Dharug Gunyalungalung. Recent research also articulates that a sense of place relates to harmonies within the earth (Stokols and Shumaker, 1981), a psychosocial space reflective of cultural relationships (Lee, 1973) that have “the capacity to tap the creative life forces of the inner space...to exercise inwardness” (Ermine, 1995, p. 104).

2. Visual Knowledge of Cultural Intent

Whilst there has been a great deal of research and curatorial study published around contemporary Aboriginal dot work, there is little attention paid to the origins of such processes. Historically, the Aboriginal contemporary art movement of the early 1970s in Central Australia has been categorised as a movement which discredits traditional practices within making. Art Teacher Geoffrey Bardon’s observations in witnessing ceremonial ground designs performed by lore men during ceremonial encounters was one of the first comprehensive Western studies performed on foundational creative making within ceremonial practice. Bardon presented the idea of reproducing these non-permanent designs into a public arena onto wall surfaces. Such public exposure of pure sacredness created offence within many Aboriginal Nations. This is because publically expressed traditional reproductions of visual spiritual images are believed to cause anger or harm to those not initiated. In response, attempts were made to cover sacredness by manipulating creative form. Crocker (1987), for example, argues that the use of dotting was implemented as a safe alternative to cover up forms of sacredness. From a Dharug standpoint multi-layering techniques are an intentional act of concealing knowledge where only the initiated are able to comprehend scared information. Dotting techniques have always been used within ceremonial healing practices and has similarities to other Aboriginal Nations. Crocker’s suggestion that dotting originated as new process for safeguarding and protecting sacredness is not totally correct. To explain further, ground makings used in traditional healing are sculpted by the hands, with fingers used to make indentations within the earth surface. It is argued that fingerprints within the earth’s surface are the original process of dot making. Whilst Croker argues that dotting was developed out of a desire to cover secrecy, it is argued that this process already existed within ceremonial healing making as a form of multi layering widely used within many Aboriginal Nations. Hence, it is more the approach of multi-layering that specifies protection of scared knowledge. In grasping a deeper understanding, Dharug symbols are more unique, in that symbols contain ancestral spiritual energies and hence have the innate power of cultural belief. Cultural visual knowledge is obtained through deep spiritual connection to ancestral pasts which only the initiated can interpret. Traditional initiation processes shape social behaviours and obligations through learning cultural law.

2.1. Simplified Symbols of Complex Knowledge

One of the most common symbols used is the circle, which represents cosmological aspects of cultural place and spiritual space. Circular impressions left on rock surfaces also indicate forms of sacredness; expressions of connections to cultural place within mind, body, and emotions. Such evidence is witnessed within the many circular images engraved on rock surfaces within Dharug Country that often includes concentric circular forms that acknowledge the harmonies within the external and internal worlds. Western misinterpretations of some circular engravings within Dharug Country have been noted. For example, according to Sim (1996) these depictions represent the moon, or solar images, yet are actually knowledge of sacredness that contain ancestral power. These symbols contain a deep central engraved hole with three emitting circles built out from the central core, which contain up to twenty radiating lines. The first circle represents individual internal roots, such as intuition with the ancestral world, with the second, larger circle representing relationships to place and space. The third, outer circle relates to the close primary cultural connections such as totems, spiritual affiliations and the extended world. Radiating lines relate to all the relationships within personal place and space within a sense of timelessness.

Figure 3.

Visual knowledge of relationships to cultural place and spiritual space; Acrylic painting on canvas by Belanjee, illustrating concentric circles of cultural connections within place and radiating lines of the relationships within space.

Figure 3.

Visual knowledge of relationships to cultural place and spiritual space; Acrylic painting on canvas by Belanjee, illustrating concentric circles of cultural connections within place and radiating lines of the relationships within space.

The circle as a Dharug symbol is representative of all self, relationships and the whole cosmos. Within making, the inner circle is often depicted as a relationship image that epitomizes innerness. The belief that everything is controlled by our internal intuitive voice is illustrated by the inner circle. Interestingly, the North-American Ojibwa Nation also expresses the circle as a metaphoric interpretation to time and place, whilst spherical form expresses spacial relationships (Graveline, 1998). Other similarities include the belief that the circle is sacred, having no beginning and no end, revolving around human generational and seasonal activities within nature depicting natural change (Mehl-Madrona, 1997).

Jung (1969) also found great significance of circular symbolic form within the Tibetan mandala, which represents the four basic human sensitivities: intuition, sensation, thinking, and feeling. Interestingly the philosophy behind the mandala has considerable similarity to Dharug relativeness of deep internalised feelings. Jung studied the mandala to pursue the psychological meaning of symbolic form, later realising its purpose as seeking order from inner confusion and chaos (Jung, 1973). After introducing his patients to mandala making, he concluded that “to paint what we see before us is a different art from painting what we see within” (Jung, 1954, p. 253). Alike to Dharug making, the mandala is created through spiralling movements often laden with colour to increase internalised illusions of movement and freedom.

3. Conclusions

In understanding cultural differences within visual expressions it is necessary to reflect on wisdom and knowledge built over generations. This may appear difficult for non-Indigenous people, who see imagery from an external viewpoint, rather than considering the deep metaphorical elements that lie beneath the obvious. Perhaps there is also a sense of prejudgment, with many non-Indigenous people observing symbols as simple forms of communication based on notions of primitiveness. Therefore, difficulties may arise in perceptions as traditional symbols reflect a sense of ingenuity requiring considerable intellectual effort acquired through trans-generational processes.

Dharug storytelling utilises visual content to ensure messages are imprinted to the next generation as expressions of worldviews, through comprehensive dialects within a collective intellectual space. It is the understanding that visual imagery is more easily stored in memory, hence simplicity is intentional. The additional use of repetitive patterning assists in memory recall, by generating rhythmical energies. The circle, for example, when used in a repetitive manner illustrates cyclical and harmonious space that ensures both conscious and unconscious responses are locked into the memory.

Within this article, it has been highlighted that Australian Aboriginal symbols are visual forms of knowledge that express cultural intellect through an association to place and space. Creative imagery comprises conscious narratives, emphasising deep insight that influences Cultural place and Spiritual space in being connection relating to Dharug Gunyalungalung, the Creational periods.