Abstract

In the early 1470s, Venetian artist Gentile Bellini painted Basilios Bessarion kneeling in front of the precious Byzantine reliquary that Bessarion donated to the Venetian Scuola di Santa Maria della Carità. This painting functioned as the cover to the tabernacle where the reliquary was stored. Rather than accurately depicting the sacred object, Bellini’s painting reworks the appearance of the reliquary in relation to the figures in the painting and reveals a disjunction between the relic and its cover. The reliquary becomes a somber, monumental object that has more presence as a looming entity than as a combination of parts and histories. This paper positions Bellini’s painted enclosure for the reliquary as a product of the blending of Venetian and Byzantine devotional practices and sacred objects. Bessarion’s reliquary was an aggregate object, and Bellini’s painting continues the reframing of Bessarion’s reliquary to serve as a visual contract of the connection between Bessarion and the Scuola di Santa Maria della Carità and, more broadly, Byzantium and Venice. Bellini’s painting ultimately seeks to capture the sacred mystique associated with Byzantine Orthodoxy while also establishing the reliquary within its Venetian, confraternal present.

1. Introduction

In Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Age of Art, Hans Belting wrote: “A religious object could have no greater proof of its power than to come from Constantinople.” (Belting 1994, p. 196). This belief was essential to the Venetian confraternity of the Scuola di Santa Maria dei Battuti della Carità, the oldest of the Venetian scuole grandi, which received a Byzantine reliquary from Basilios Bessarion (1403–1472) in 1472. A metropolitan of Nicaea in the Orthodox Church, Bessarion devoted his life to the unification of the Eastern and Western churches and campaigned for this cause at the Ecumenical Council of Ferrara and Florence in 1438, which brought the Eastern and Western Churches together through a nominal agreement. Pope Eugenius IV (1383–1447, r. 1431) made Bessarion a cardinal of the Latin Church in 1439 in recognition of his continued efforts. In 1463, Bessarion visited Venice and pledged a precious reliquary to the Scuola di Santa Maria della Carità upon his admittance to the confraternal organization in search of support against the Ottoman Turks (Campbell 2005, pp. 36–37; Klein 2013, p. 246). The reliquary was a staurotheke, meaning that it held a relic of the True Cross. Bessarion’s reliquary contained two fragments of the True Cross as well as two pieces of Christ’s tunic. It was previously owned by the Byzantine princess Eirēnē (or Irene) Palaiologina and came to Bessarion through a bequest from Patriarch Gregorios III Melissema in 1459 (Campbell 2017, pp. 332–33; Klein 2017, p. 8). Following the official transfer of the reliquary to the confraternity in 1472, the scuola kept the sacred object in a locked tabernacle in their albergo, or meeting room, when not being carried in processions on special feast days or otherwise venerated. The tabernacle was adorned with a painted cover by the Venetian artist Gentile Bellini (1429–1507) that depicts Cardinal Bessarion kneeling before the reliquary in an attitude of prayer with two members of the scuola.

It was likely Venice’s wealth, proximity to shipping routes, and connections to Constantinople that inspired Bessarion’s donation. However, he chose to give the relics to a civic institution with religious ties, rather than to the doge or San Marco as representatives of the republic. In Venice, the scuole—religious lay confraternities that were created for lay devotion and mutual aid for members—handled many communal responsibilities for the city (Brown 1998, p. 15; Wurthmann n.d.). The scuole were divided into scuole grandi and scuole piccoli, which were in part divided by membership size (the scuole grandi were allowed up to 550 members), as well as by prestige and historical power. The four scuole grandi of the early fifteenth century were formed in the thirteenth century as self-flagellating orders, and regularly held ritual processions through the public spaces of Venice on holy days. The Scuola di Santa Maria dei Battuti della Carità was the oldest Venetian confraternity, followed by the Scuola di San Marco, the Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista, and the Scuola di Santa Maria della Misericordia. Eventually, two other scuole would join the ranks of the scuole grandi: the Scuola di San Rocco in 1489 and the Scuola di San Teodoro in 1552 (Wurthmann n.d.). Each scuola had its own headquarters, usually next to the church from which it took its name, which consisted of a large meeting hall, a chapel, and a smaller committee room, or albergo. The meetinghouse of the Carità was near the center of the city, and in the mid-fifteenth century, its members expanded their house with a new albergo, where Bellini’s painting was part of the decorative program and a visual statement of the confraternity’s significance.

Bessarion’s reliquary is an aggregate object compiled in three discrete phases: the gold and enamel Byzantine staurotheke, later set into a golden, gem-encrusted framework of narrative scenes, covered with a painted wooden cover, and eventually embedded within a Venetian metalwork support. Bellini’s painting continues the reframing of Bessarion’s reliquary and serves as a visual contract of the connection between Bessarion and the Scuola di Santa Maria della Carità and, more broadly, Byzantium and Venice. This paper seeks to interrogate the importance of Bellini’s manipulation of scale, a drastic alteration of the size of the reliquary in relation to the three figures in the painting. In highlighting this often-ignored incongruity, I suggest a new reading of Bellini’s tabernacle door as a visual argument for the Byzantine provenance of the reliquary that bolsters the reputation of the Scuola di Santa Maria della Carità through their possession of this significant, sacred object.

2. The Transformations of Bessarion’s Reliquary

As a result of its location and prominence as an international mercantile city, Venice had always enjoyed closer contact with the Byzantine Empire than most other Western cities. However, after the Fourth Crusade of 1204 when Venice sacked Constantinople and the fall of Constantinople in the mid-fifteenth century, Venice actively presented itself as a new Byzantium. The city visually incorporated Byzantine spoils and adapted Byzantine styles into its religious and civic artworks, perhaps seen most overtly in the four bronze horses taken from Constantinople in 1204 and installed on the façade of San Marco, and the striking Pala d’Oro at the high altar of the same church.1

Bessarion’s reliquary was a donation on a smaller scale, yet incredibly significant to the Scuola di Santa Maria della Carità (hereafter, the Carità) as a visual and theological marker of its place within Venetian culture. As a staurotheke, the reliquary was highly desirable. Relics of the True Cross were linked in perpetuity to the Byzantine Imperial court, due to St. Helena’s legendary discovery of Christ’s cross.2 Bessarion’s donation of this reliquary was one of several he made to various Venetian institutions as he strove for the unification of the Eastern and Western Churches. Bessarion’s gifts also sought to solicit Western military support for a crusade against the Turks. The Guardian Grande of the Carità, Andrea della Sega, recorded the arrival of Bessarion’s reliquary on Trinity Sunday in 1472, nine years after the cardinal pledged it to the charitable institution.

2.1. Physical Transformations

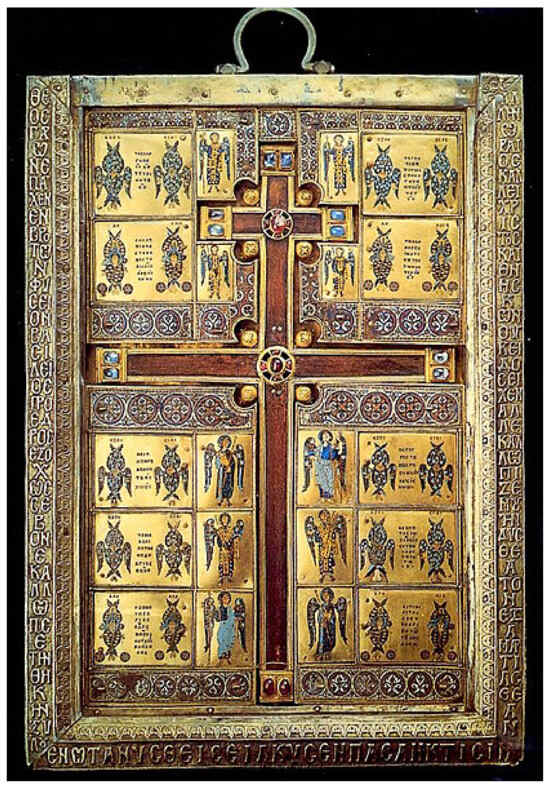

By the time the reliquary reached Venice in 1472, it had undergone many stages of transformation (Figure 1). The original reliquary of bright gold and richly colored enamel—a rectangular reliquary with an inset three-armed cross, two enamel portraits of Emperor Constantine and his mother St. Helena, and four windows for the four Christological relics—exemplified the gilded, high-relief style associated with the late Byzantine Empire. This earliest part of the object dates from the mid-fourteenth century (Campbell 2005, p. 36). Bright gold and richly colored enamel are set against a star-studded blue enamel background. The crucifix features a highly worked repoussé figure of Christ on a smaller cross, and green enamel roundels hold the first letters of Greek inscriptions called cryptograms, which functioned as apotropaic or spiritual formulas (Pentcheva 2017, p. 375). Visible behind the rectangular windows that protect and seal them in the reliquary, the two fragments of the True Cross and two pieces of Christ’s tunic stand out against a gold background. Reliquaries protect relics, but they also visually communicate their importance and, in some cases, information about the relics within. The rectangular, panel-like box of Bessarion’s reliquary was a type particularly associated with the Byzantine court, as seen in objects like the Limburg staurotheke (Figure 2). Both Bessarion’s reliquary and the Limburg staurotheke feature an inset, removable cross surrounded by compartmentalized imagery—scenes from the Passion on the Bessarion reliquary, and angels, cherubim, and seraphim on the Limburg staurotheke. Both reliquaries have a sliding, rectangular cover and are adorned with gold, enamel, and gems. While this is a single comparison, it demonstrates some of the common elements expected of a Byzantine object by those in the West.

Figure 1.

The Reliquary of Cardinal Bessarion, late fourteenth century to 1460s, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice (Wikimedia, Mongolo 1984, CC BY-SA 3.0).

Figure 2.

Limburg Staurotheke, late 10th century, Limburg an der Lahn, Hesse (Wikimedia, ManiacParisien, image in public domain).

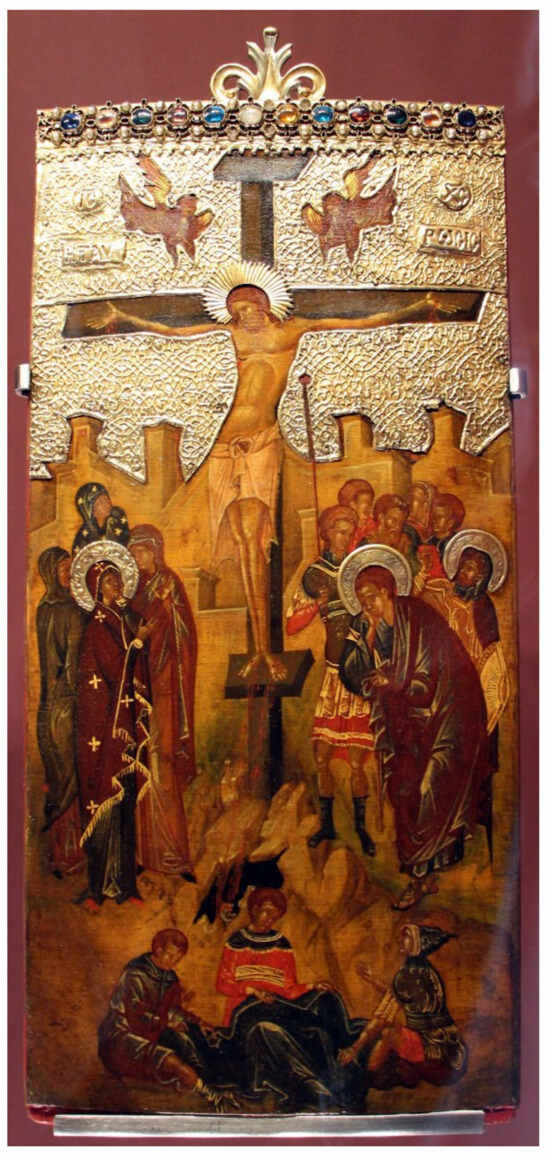

In Bessarion’s reliquary, the rich colors of the central reliquary are echoed in the seven narrative scenes that surround the Byzantine object on three sides. A gold band with pearls and cabochon-cut gemstones protrudes between each rectangular depiction of a moment from the Passion narrative, which is identified with Greek inscriptions. During this stage in the object’s life, it also gained a painted cover that features an image of the Crucifixion outside a walled city with a group of guards playing dice for Christ’s robe in the foreground (Figure 3). While the cover served to obscure the inset relics on a day-to-day basis, the depicted scene alluded to what was behind the painted panel. By positioning the three figures in the act of dividing Christ’s garments between them in the central foreground, the artist directly referenced the two fragments of Christ’s tunic within the reliquary. The narrative paintings and the painted cover for the reliquary were likely completed by an artist or workshop in Crete before Bessarion’s ownership, based on the description in the 1463 act of donation (Klein 2017, p. 25). Compounding these painted additions, between 1463 and 1472, Bessarion commissioned a metalwork frame and stem that further enclosed the object and allowed members of the Scuola to carry and present the reliquary in processions (Campbell 2017, p. 335; Klein 2013, p. 248; Lauber 2017, pp. 64–65; Polacco 1992, pp. 87–94).

Figure 3.

Cover for the Reliquary of Cardinal Bessarion, first half of the 15th century, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice (Wikimedia, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0).

2.2. Reinterpretation in Painting

When the Carità received the reliquary, they needed to ensure that they had a proper place to keep the sacred object when it was not on view during processions and rituals. Based on a letter to Bessarion on 6 July 1472 from Andrea dalla Siega, the guardian grande (leader or chief official) of the Carità, we know that the confraternity planned to house the reliquary within what he described as a “tabernaculum et monumentum [tabernacle and monument].”3 With this in mind, the Carità commissioned Gentile Bellini to paint a panel that would serve as the cover to a tabernacle to house the reliquary when not in use, though the remainder of the tabernacle no longer survives (Brown 1987, p. 192; Campbell 2017, p. 336). By the 1470s, Gentile Bellini was a well-established Venetian artist who had previously worked for the church of the Scuola with his father, Jacopo, and his brother, Giovanni.

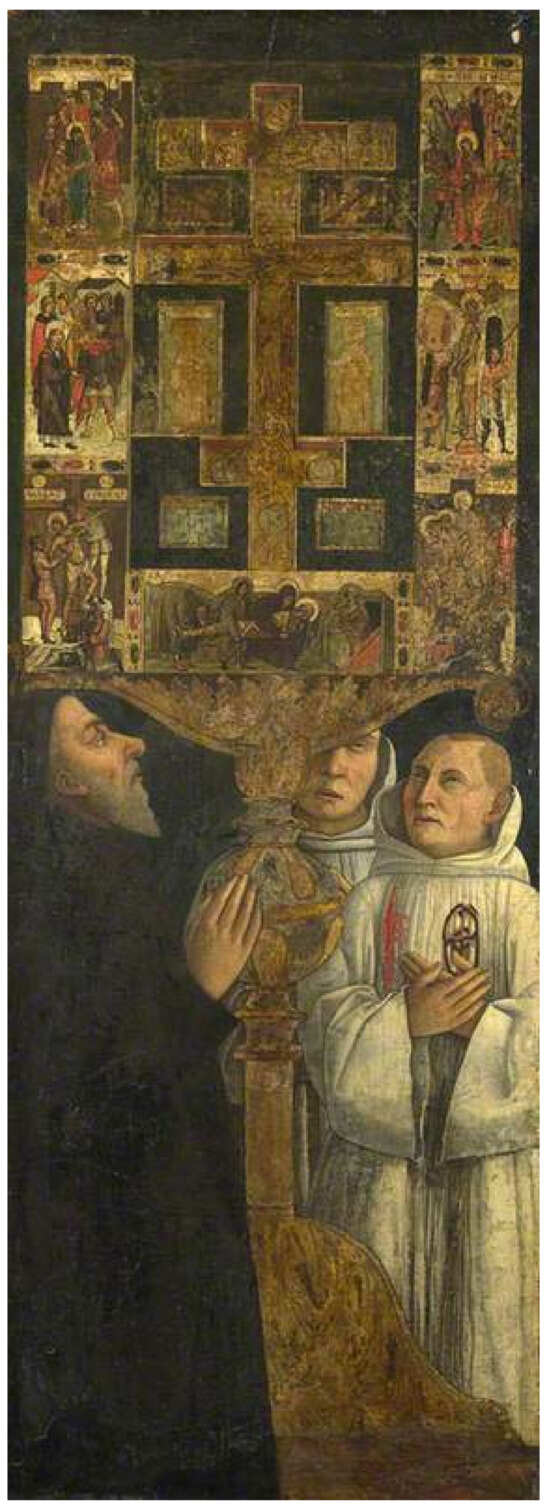

Bellini’s painting features three figures who kneel below a large reliquary that dwarfs the figures and dominates the upper portion of the narrow, rectangular panel (Figure 4). The black-robed figure of Cardinal Bessarion appears closest to the picture plane, his face and hands presented in profile and slightly overlapping the knop of the reliquary stem near the center of the panel. Two male figures in white robes kneel on the right side of the panel, clearly placed behind the reliquary that overlaps their bodies. Both figures cross their hands in front of their chests and raise their heads towards the reliquary. Their eyes squint and seem to roll back as if to emphasize the physical and spiritual toll of looking and devotion they act out within the painting. The figure on the far right has red and black badges on his chest. The figures behind the reliquary are members of the Carità, who are clothed in the white robes that they wore in processions. While the three figures only occupy the bottom half of the panel, the reliquary itself extends the entire length of the painting. The image has a stark, black background, and a uniform light falls on and illuminates the reliquary from the front right side of the panel, ensuring that the reliquary is the focal point of the painting. Bellini defines the reliquary through strong geometric shapes and the subtle interplay of linear outlines and sketchily depicted details.4

Figure 4.

Gentile Bellini, Cardinal Bessarion with the Bessarion Reliquary, 1470s, National Gallery of Art, London (Wikimedia, BotMultichill, image in the public domain).

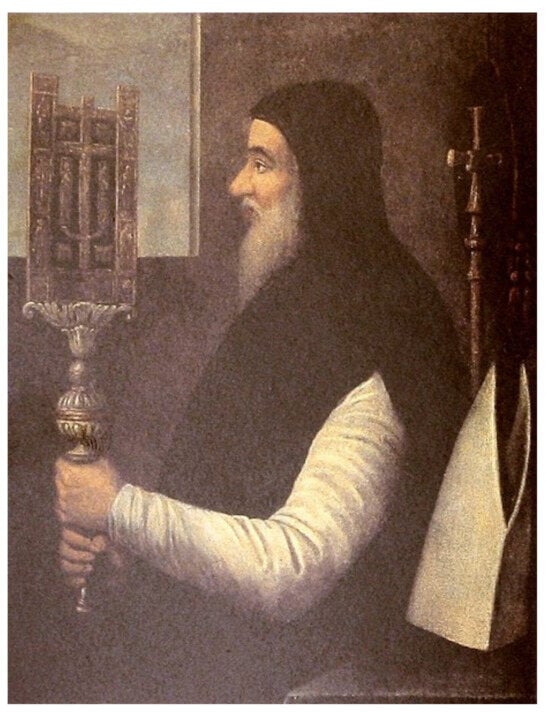

In Bellini’s painting, the various additions to the reliquary are blended and subsumed into a singular object whose appearance obscures its nature as a pastiche of elements dating from different periods and produced in wide-spread geographical regions. The divisions between enamel, painted panels, and metalwork are softly diffused in Bellini’s depiction of the reliquary. The artist mutes the glint of precious metals and sheen of enamel, resulting in a somber, monumental object, which has more presence as a looming entity than as a combination of parts and histories.5 More striking than Bellini’s manipulation of materials in the painting is his reimagining of scale. Bessarion’s reliquary measures forty by fifteen inches, which is comparable to the physical size of the painted reliquary on Bellini’s panel. Therefore, while the reliquary itself remains consistent in relation to the viewer, the figures of Bessarion and the two members of the Carità shrink drastically as compared to the life-sized reliquary. A 1540 painting of Cardinal Bessarion and his Reliquary by Gianetto Cordegliaghi demonstrates the significant, purposeful alteration of the reliquary in Bellini’s tabernacle door (Figure 5).6 The painting is by one of Bellini’s pupils and is thought to be a copy of a lost portrait of Bessarion that Bellini painted for the confraternity’s albergo. There, it would be positioned near the tabernacle and further remind members of the confraternity of Bessarion’s important donation. In contrast with the tabernacle cover it originally shared a room with, Cordegliaghi’s painting shows Bessarion grasping the handle below the knop with two clenched fists, and staring straight ahead towards the reliquary, which is slightly larger than his head. When both of Bellini’s paintings were together in the Carità’s albergo, as they were until the Napoleonic suppression of religious orders in 1810, the varied scale of the reliquary in each painting would have been unavoidably evident.

Figure 5.

Gianetto Cordegliaghi, Cardinal Bessarion and His Reliquary, 1540, Biblioteca Marciana, Venice (Wikimedia, Shakko, image in the public domain).

3. Confraternal Competition

The clearly Byzantine nature of Bessarion’s reliquary was a significant element in the rivalry between Santa Maria della Carità and another of the scuola grande, the Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista. As Patricia Fortini Brown has demonstrated, the pious confraternities of Venice navigated a tricky balancing act within the religious and civic life of the city, striving for equal honor and prestige through various means, including their relics (Brown 1987). Like the Carità, the Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista also possessed a relic of the True Cross with a Byzantine provenance, donated by the Crusader and scholar Philippe de Mézières (1327–1405), the grand chancellor of Cyprus, in 1369 (Klein 2010, p. 224). San Giovanni Evangelista commissioned an elaborate metalwork and rock crystal processional cross to house the relics, and this reliquary played a key role in important religious processions (Brown 1987, p. 193; Klein 2017, p. 25). Furthermore, San Giovanni Evangelista’s relic gained a reputation as an effective miracle-working relic, with at least nine recorded miracles between 1370 and 1480. Between 1490 and 1506, the scuola published an incunabulum detailing the reception and miracles of the relic. The incunabulum stated: “Amongst the other worthy relics that one presently finds in Venice, truly the cross of the scuola of misier [sic] San Giovanni Evangelista is the most worthy and the most excellent; which is most certainly and undoubtedly believed to be the wood of the cross where our savior hung to save us, and this is proven by many miracles that happened in diverse times which are noted in order here below.”7 The arrival of Bessarion’s reliquary, in 1472, presented a challenge to San Giovanni Evangelista not only as another relic of the True Cross but also, as argued by Holger Klein, because Bessarion’s reliquary more effectively visualized its Byzantine origins. As Klein argued in his seminal article, “Eastern Objects and Western Desires,” relics from the East carried an inherent value that was not tied to their material worth, but rather to the carefully constructed power of the Byzantine emperor as he discriminately dispersed the most prestigious relics (Klein 2004, pp. 285–87). The situation changed after the sack of Constantinople in 1204, after which the emperor no longer controlled the most sacred relics (Majeska 2004, pp. 187–88). By the late fifteenth century, Venice likely had the greatest concentration of Greek relics in Europe. These relics included the body of St. Mark, the arm of St. George, a fragment of the skull of St. John the Baptist, and at least six other relics of the True Cross (Klein 2010, p. 211). As Klein argues, visual authenticity and the recognition it entailed were essential for the efficacy of Byzantine relics (Klein 2004, p. 306). Bessarion’s appearance in Bellini’s painting is important because he functions as a signifier of the Byzantine connection of the reliquary, emphasizing the Carità’s connection to Constantinople in their framing of the relic, but also demonstrating the ultimate appropriation and absorption of Byzantine elements by Venice.

It was typical for scuole to decorate their headquarters with cycles of scenes related to the dedications of their scuole or important relics they housed. Coinciding with the publication of the incunabulum cited above, the Scuola of San Giovanni Evangelista commissioned a cycle of nine paintings that followed the text to celebrate their miracle-working relic and their significance to the civic functions of Venetian society. Unlike Bellini’s tabernacle cover for the Carità, which commemorated its donor and provided an exemplar for veneration, the cycle for San Giovanni Evangelista was based on miracle accounts but, in reality, celebrated the city of Venice.

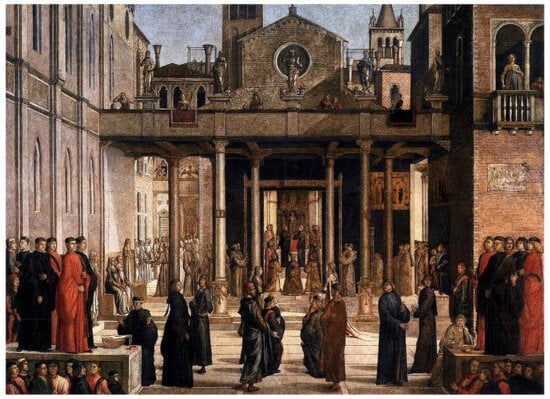

The cycle of paintings involved many of the leading Venetian artists of the day. Gentile Bellini painted Procession of the Relic of the True Cross and two other scenes in 1496; other paintings in the cycle include Lazzaro Bastiani’s Offering of the Relic of the Holy Cross to the Brothers of San Giovanni Evangelista from 1494 and Vittore Carpaccio’s Miracle of the Relic of the True Cross from the same year.8 As Patricia Fortini Brown ably explores in Venetian Narrative Painting, in each of these scenes, the Venetian setting of the miracles takes precedence over the miracles themselves or the relic which effects them. For example, in Bastiani’s painting of the presentation of the relic to the scuola, while the relic is centrally placed and framed in a doorway, the scene is still almost lost in the perspectival rendition of the Venetian setting populated with portraits of scuola members (Figure 6). As a key moment that establishes the authority and provenance of the relic for the scuola, one might expect the sacred object to take greater precedence in the painting. Similarly, in Bellini’s Procession of the Relic of the True Cross, the relic is centrally placed and framed by a canopy, but the scuola members taking part in the procession and the expansive Piazza San Marco dominate the composition.

Figure 6.

Lazzaro Bastiani, Offering of the Relic of the Holy Cross to the Brothers of San Giovanni Evangelista, 1494, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice (Wikimedia, Sailko, image in public domain).

Though Bellini’s earlier, smaller painting for the Carità was not a narrative, I argue that it similarly demonstrated the Carità’s central significance to the civic life of Venice. For each of these two scuole, the entire albergo functioned as a frame for its Byzantine relic of the True Cross, which informed how it should be received and perceived in Venice as a whole. In the albergo of the Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista, the cycle of paintings situated the relic within the city both in each scene individually and in the arrangement of the room as a whole. According to Patricia Fortini Brown’s reconstruction of the albergo of San Giovanni Evangelista, the scuola kept their relic of the True Cross in the altar at the front of the room, possibly below Carpaccio’s miracle painting and opposite Bellini’s painting of the procession (Brown 1998, p. 136, appendix XV). The paintings encircled the top half of the two-story high room with carefully rendered ‘eyewitness’ depictions of Venice. This arrangement invited the viewer to imagine themselves in a microcosm of Venice through the common color choices, vanishing point, and scale of each panel. However, the decorations in the Carità albergo presented a close view of the reliquary and donor, rather than a scene that connected the subject to the city. Whereas the reliquaries themselves are barely suggested in the San Giovanni Evangelista cycle, Bessarion’s reliquary is an unavoidable presence in Bellini’s painting for the Carità. Instead of emphasizing miracles, Bellini’s tabernacle cover as well as the portrait of Bessarion emphasized devotion and enhanced the connection to the sacred. Though each scuola utilized a different aesthetic approach—narrative versus donor portrait, large wall panel versus small tabernacle cover—both scuole transformed Byzantine relics into objects of particularly Venetian devotion.

With this understanding of the competition between the Carità and San Giovanni Evangelista, the inclusion of Bessarion and the two scuola members in Bellini’s painting gains new significance. Bessarion offered his reliquary to the confraternity as a pious gift, but it also functioned as a visualization of the contract between Bessarion and the scuola, which made Bessarion an honorary member. Caroline Campbell argues that the scuola members in Bellini’s painting may represent Ulisse Aliotti and Andrea della Siega, two leaders within the confraternity who facilitated the gift of the reliquary (Campbell 2005, p. 38). In this context, their upturned eyes might not only visualize devotion but also hint at the silver inscription in Latin on the reverse of the reliquary: BESSARIO EPISCOPVS SABIN CAR NICAENVS PATRIARCHA CONSTANTINOPOLITANVS BEATEA VIRGINI MARIAE SCHOLAE CARITATIS VENETIIS. This inscription establishes Bessarion’s role as donor and his connection to both the Greek and Latin Churches and to Constantinople, but significantly concludes by naming the Scuola di Santa Maria della Carità, as well as their position in Venice. These elements serve to effectively transition the reliquary into the hands of the Carità and authenticate their claims to Byzantine connection.9

4. The Donor and the Portrait

Bellini’s painting of Cardinal Bessarion, his reliquary, and the two members of the confraternity who received his donation already fulfilled a specific function as the lockable door to the reliquary’s housing within the albergo. For the remainder of this article, however, I would like to consider another role that Bellin’s painting filled—that of a portrait. Who, or what, however, is it a portrait of?

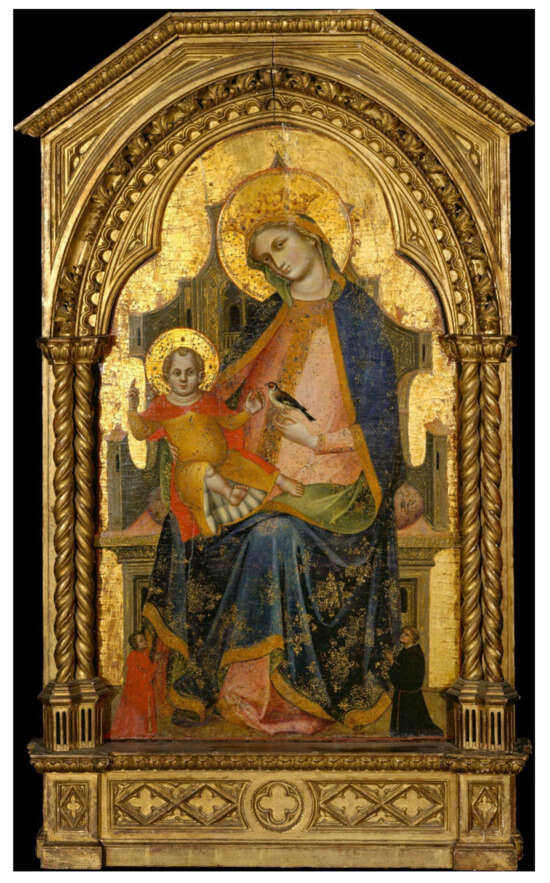

Both the position and the scale of the three figures in Bellini’s tabernacle painting immediately suggest donor figures. Donor portraits function as a type of votive imagery, serving to prominently position an individual, couple, or family near holy or otherwise important figures. The donor benefits through both religious commemoration and social cachet. To emphasize that the donors themselves are not holy figures worthy of veneration, in most medieval depictions in both East and West, the donors are carefully set apart from the sacred figures or narrative. In some instances, this is a physical separation, in which the donors are placed in a frame or a flanking wing of an altarpiece, but in many examples, donors are differentiated by their minute size in comparison to the holy imagery. Lorenzo Veneziano’s Madonna and Child Enthroned with Two Donors (ca. 1360–65) exemplifies this type (Figure 7). Within the painting, the Virgin Mary sits on an architectural throne, supporting the Christ Child on one knee while a goldfinch perches on her opposite hand. At the Virgin’s feet, almost subsumed by the folds of drapery that cascade from her lap, kneel two small figures in attitudes of devotion. The man on the right has the tonsure, brown habit, and knotted rope belt of a Franciscan friar, while the figure on the opposite side wears a red garment that may reference the traditional clothing of Venetian senators. Were these two figures to stand, their entire bodies would still be smaller than the infant Christ, reinforcing that they do not physically occupy the same space as the holy figures, but rather are connected through their act of donation and dedication.

Figure 7.

Lorenzo Veneziano, Madonna and Child Enthroned with Two Donors, ca. 1360–65, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (image in the public domain).

By the mid-fifteenth century, many artists across Europe had shifted to more proportional donor figures, a move that was likely connected to Renaissance interests in perspective and lifelikeness.10 This was not universally true, as demonstrated in Carlo Crivelli’s 1470 Madonna and Child Enthroned with Donor, a painting closely contemporary to Bellini’s tabernacle painting (Figure 8). While Crivelli crafts a sense of depth and occupiable space within the painting through his use of linear perspective and modeling of figures and objects, this implied verism is jarringly disrupted through the Lilliputian figure who kneels at the hem of the Virgin’s garments. Furthermore, Crivelli depicts the crown of Heaven near the figure, where the crown seems to balance on the edge of the pavement at the Virgin’s feet. This serves to draw the viewer’s eye to Crivelli’s ability to disrupt our understanding of two- and three-dimensional space.

Figure 8.

Carlo Crivelli, Madonna and Child Enthroned with Donor, 1470, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (image in public domain).

However, Bellini and Crivelli were not the only late fifteenth-century artists who perpetuated the tradition of diminutive donor figures. To give only one example, Benozzo Gozzoli’s 1481 Saints Nicolas of Tolentino, Roch, Sebastian, and Bernardino of Siena with Kneeling Donors, likely painted for a patron in Pisa, features a male and female donor who kneel in the foreground at approximately a quarter of the size of the standing saints (Figure 9). Both the position and the scale of these donors follow the established conventions as demonstrated in the Lorenzo Veneziano painting discussed above.

Figure 9.

Benozzo Gozzoli, Saints Nicholas of Tolentino, Roch, Sebastian, and Bernardino of Siena, with Kneeling Donors, 1481, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (image in the public domain).

Two elements set Bellini’s painting of Cardinal Bessarion and his reliquary apart from these Western examples of paintings with donor figures. The first is the object of veneration, which is the literal object of the reliquary, rather than the Virgin and Child, saints, or other holy figures. The second is the setting of the painting, which isolates the three kneeling figures and the monumental reliquary within a dark, claustrophobic space that lacks any reference points for the scale of the people or the object within their environment. The incongruity between the relative scale of the reliquary and the relative scale of the humans who interact with the reliquary is only understood when Bellini’s rectangular panel fulfills its purpose, not just as a painting, but as the tabernacle door that protected the reliquary. It is only when the viewer originally in the scuola’s albergo perceives the equivalent relationship between Bellini’s painted reliquary and Bessarion’s donated object at the same time as they view their body in comparison to the depiction of Bessarion and the two confraternity members that the manipulation of scale becomes truly evident.

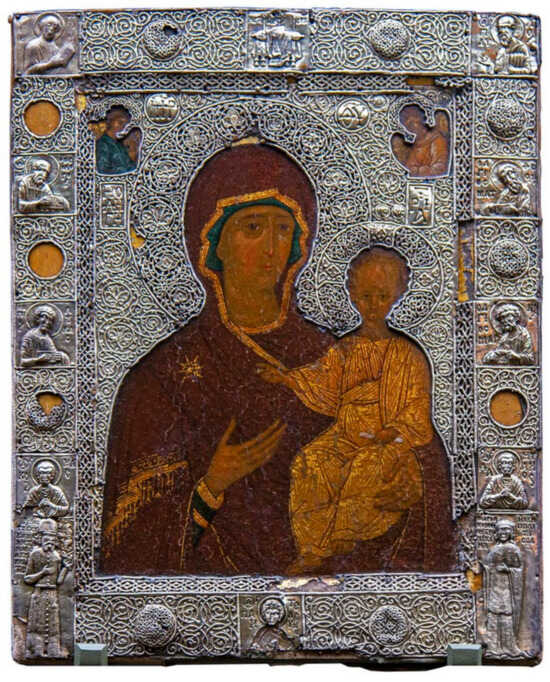

In contrast to Western devotional imagery, Byzantine icons, manuscripts, and other imagery more consistently maintained the exaggerated difference in size between holy figures and donors well into the fifteenth century. As an example, the Reveted Icon with the Virgin Hodegetria from the late thirteenth or early-fourteenth century visually connects the viewer of the icon to the holy figures through the frame, which features small full-body representations of the donors (Figure 10). The donors function as examples of devotion for the viewer, as well as a sort of steppingstone from exterior to interior. Similarly, Bessarion in Bellini’s painting serves as a transition from simply viewing the painting to engaging with the reliquary, through his exemplary prayer and his physical position that overlaps with the reliquary.

Figure 10.

Icon of the Virgin and Child, late 13th–early 14th century, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow (Flickr, byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

In looking at the treatment of donor figures, or Renaissance and Byzantine art more broadly, it is tempting to speak in generalities, with a distinct separation between Latin and Greek styles. However, evidence shows that the situation was much more nuanced, with patrons and institutions commissioning and collecting works in both styles. This was particularly true in cities like Venice, which in many ways prospered as a direct result of the meeting and blending of cultures. For Western viewers moving into the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the saturated colors, rich materials, and stylized flatness of Byzantine art evoked the past and therefore signaled a connection to early Christianity regardless of the actual age of a given object. Bellini exploits this association in two ways in the tabernacle door. First, through the size and prominence of the reliquary itself, he is able to feature the Greek-style paintings and adornments that characterized the reliquary and highlight the form of the staurotheke, which was particularly associated with the Byzantine imperial court. Second, through the alteration of the scale between the reliquary and the three venerating figures, Bellini evokes not just depictions of donors, but specifically an approach to donor portraits that itself echoes Byzantine precedents that may be understood as a type of claim to antiquity. Bellini pointedly used the smaller donor figures as a way to draw attention to them—somewhat conversely given their size—at a moment when donor figures in painting were shifting to become at the same or a closer scale to the holy figures. While Bellini was not alone in using the diminutive donors, as discussed above, his use in combination with the emphasis on the Byzantine nature of both object and donor suggests that Venetian viewers may have understood Bellini’s shrunken Bessarion and confraternity members as an additional reference to the reliquary’s Byzantine provenance.

In a recent study, Rico Franses argues that the fascination with the individuality of donors within Byzantine portraits overshadows the other elements of the paintings, including holy figures. He states: “These scenes thus come to be subsumed under the broader category of ‘The Portrait’ in general, and examined in that capacity alone, rather than in their specificity as representations of an interaction between a set of characters (Franses 2018, p. 9).” Bearing that in mind, what do we gain from a consideration of all of the characters—Bessarion, scuola members, and reliquary—depicted in Bellini’s painting? The painted tabernacle door fits the definition of a donor portrait, in that it shows both the owner and recipient of an object. In contrast to the most established form of donor portrait, the recipient in Bellini’s painting is not God or another holy figure, but instead the members of the confraternity to which Bessarion gave his reliquary (Franses 2018, pp. 17–22).

In Byzantium during the Palaiologan period (1261–1453), portraits became more common than they had been during earlier, more iconoclastic periods, and were used for a variety of functions including as semi-legal documents. For example, a donor portrait could be used to visualize a contract, particularly an evocation of intercession through a gift from devotee to saint (Carr 2006, pp. 190–91). The inclusion of both Bessarion and the Carità members in Bellini’s painting may suggest this component of donor paintings, visualizing the contract between cardinal and confraternity that was satisfied through the donation of the reliquary in 1472 and its placement in the tabernacle behind Bellini’s painted door. Rosella Lauber recently suggested a new date for Bellini’s painting as completed after 11 April 1474, based on a vote from the confraternity to commission a “pavimento de taio dorado [a carved and gilded support]” to hold the pole of the reliquary, a furnishing that is depicted in Bellini’s painting (Lauber 2017, pp. 70–75). With a 1474 date, the depiction of Bessarion is decidedly postmortem, completed at least two years after the cardinal died. This, in addition to the fact that both Bellini’s tabernacle door and the other painted portrait of Bessarion were installed in the Carità’s albergo with a marble inscription that extorted the members of the confraternity to remember Bessarion in their prayers, further emphasizes the memorial element of donor portraits.

Is the discrepancy between the scale of the reliquary and the figures in Bellini’s painting then solely due to the conventions of donor portraits, particularly those with Byzantine influence? Perhaps, but an additional nuance of donor portraiture certainly supports and strengthens the correlation between the painting, the reliquary itself, its holy contents, and the individuals depicted. As addressed above, the small figures in donor portraits were a way to indicate that those individuals did not physically occupy the sacred space of the holy figures. Franses extends this visual convention to suggest that the inclusion of the disproportionate donors within a depiction of sacred space was a way to envision the miraculous nature of these dedicatory and intercessory encounters (Franses 2018, p. 203). While Bessarion’s reliquary was itself a precious object, it had far greater value due to its sacred power as an intercessory tool. The Christological relics inside inspired great hope in the members of the Carità that they would soon be witness to (and beneficiaries of) miracles enacted through the reliquary. Bellini’s painting asserts this potential power by presenting the reliquary within the painting in a position that would usually be occupied by Christ himself or another holy figure. The reliquary becomes the intercessor in a way that was understood theologically but rarely depicted visually. Through this lens, the monumental reliquary visualizes its miraculous status in Bellini’s painting as it towers over Bessarion and the two confraternity members, even if the miracles that the Carità hoped for ultimately never came to pass.

5. Conclusions

Bessarion’s reliquary and the Christological relics it contained were the last official gift to Venice from Byzantium (Perocco 1984, p. 18). Anthony Cutler argues that, by the time Venice displayed Cardinal Bessarion’s reliquary beneath the Pala d’Oro in San Marco in 1472, the Byzantine origins of both objects were lost, subsumed beneath purely Venetian identities (Cutler 1995, p. 257). While the specifics of the provenance of each object may have been obscured by time, I contend that the Byzantine identity of Bessarion’s reliquary was visually maintained as part of Venetian efforts to redefine its identity as the heir of Byzantium, essential to its civic status. The Scuola di Santa Maria della Carità used Bellini’s painted tabernacle cover to communicate its prestige and connection to Venice, and to compete with the Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista, theoretically and physically refashioning the Byzantine reliquary within its own Venetian frame.

How should we characterize Bellini’s painting of Cardinal Bessarion and his reliquary? While Bellini’s painting might not accurately depict the reliquary in terms of material or scale, the panel still fulfills its tripartite function as a lockable cover for the reliquary’s resting place, an indication of what was inside the cabinet, and a reminder of the object’s donor. Ultimately, it privileges the object over the patron and devotees. The details of the object itself are obfuscated, echoing the visual understanding of the object from a distance in a dark church or crowded procession. Bissera Pentcheva makes a strong case for the animating effect of the gilded surface of Bessarion’s reliquary itself to evoke the divine space of heaven, establishing the reliquary as an object that is meant to facilitate active communication between heaven and earth (Pentcheva 2017, p. 376). In contrast, Bellini’s painting of Cardinal Bessarion’s reliquary is quiet and still. Here, adorning a tabernacle in the albergo of the Carità, the painting evokes a different connection, one between Bessarion and the confraternity, between Byzantium and Venice, one that acknowledges the history of the reliquary and its donor but ultimately situates the reliquary firmly in its Venetian, confraternal present.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable; no new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The scholarship on this topic is vast; see, for instance: (Bettini 1984, pp. 35–64; Brown 1996; Cutler 1995, pp. 237–67; Georgopoulou 1995, pp. 479–96; Matthews 2018, pp. 72–109; Pincus 1992, pp. 101–14). |

| 2 | Helena is initially associated with the Finding of the Cross in Ambrose’s 395 CE De obitu Theodosii. (Baert 2004, pp. 24–29; Borgehammar 1991; Drijvers 1992). |

| 3 | ASVe SGSMC, Atti, reg. 140, ff. 144–145r, cited in (Lauber 2017, p. 66). |

| 4 | For a detailed discussion of where Bellini’s depiction of the reliquary differs from its current appearance, see (Campbell 2017, pp. 340–41; Klein 2013, pp. 253–67). |

| 5 | For a discussion of the accuracy of Bellini’s painting in relation to the current composition of the reliquary and its likely original form, see (Klein 2013, pp. 253–67). |

| 6 | This painting is now in the Biblioteca Marciana, which houses the manuscripts Bessarion dedicated to the Venetians (Cutler 1995, p. 257). |

| 7 | Incunablum of San Giovanni Evangelista, cited in (Brown 1998, p. 135). |

| 8 | Of the nine paintings, three were by Gentile Bellini, two by Giovanni Mansueti, one by Vittore Carpaccio, one by Lazzaro Bastiani, one by Benedetto Diana, and one by Pietro Perugino (Brown 1998, p. 63). |

| 9 | For a discussion of the metonymic nature of Byzantine objects, particularly icons, in the West after the Fourth Crusade, see (Harvey 2021, pp. 113–31; Voulgaropoulou 2019, pp. 1–41). |

| 10 | Consider, for instance, Robert Campin’s Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece), ca. 1427–32 or the Madonna and Child with Saints and Donors attributed to Sebastiano del Piombo, both at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

References

- Baert, Barbara. 2004. A Heritage of Holy Wood: The Legend of the True Cross in Text and Image. Translated by Lee Preedy. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans. 1994. Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Age of Art. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bettini, Sergio. 1984. Venice, the Pala d’Oro, and Constantinople. In The Treasury of San Marco, Venice. Edited by David Buckton. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 35–64. [Google Scholar]

- Borgehammar, Stephan. 1991. How the Holy Cross Was Found: From Event to Medieval Legend. Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksell International. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Patricia Fortini. 1987. Honor and Necessity: The Dynamics of Patronage in the Confraternities of Renaissance Venice. Studi Veneziani 14: 179–213. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Patricia Fortini. 1996. Venice and Antiquity: The Venetian Sense of the Past. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Patricia Fortini. 1998. Venetian Narrative Painting in the Age of Carpaccio. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Caroline. 2005. The Bellini, Bessarion and Byzantium. In Bellini and the East. Edited by Caroline Campbell and Alan Chong. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Caroline. 2017. ‘Almost Another Byzantium’: Gentile Bellini and the Bessarion Reliquary. In La Saturoteca Di Bessarione Fra Constantinopoli e Venezia. Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, pp. 331–49. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, Annemarie Weyl. 2006. Donors in the Frames of Icons: Living in the Borders of Byzantine Art. Gesta 45: 189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, Anthony. 1995. From Loot to Scholarship: Changing Modes in the Italian Response to Byzantine Artifacts, ca. 1200–1750. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 59: 237–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drijvers, Jan Willem. 1992. Helena August: The Mother of Constantine the Great and the Legend of Her Finding of the True Cross. Leiden and New York: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Franses, Rico. 2018. The Literal, the Symbolic, and the Contact Portrait: On Belief in the Interaction between Human and Divine. In Donor Portraits in Byzantine Art: The Vicissitudes of Contact between Human and Divine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 194–222. [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulou, Maria. 1995. Late Medieval Crete and Venice: An Appropriation of Byzantine Heritage. The Art Bulletin 77: 479–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, Maria. 2021. Icon, Contact Relic, Souvenir: The Virgin Eleousa Micromosaic Icon at The Met. Metropolitan Museum of Art Journal 56: 113–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Holger A. 2004. Eastern Objects and Western Desires: Relics and Reliquaries between Byzantium and the West. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 58: 283–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Holger A. 2010. Refashioning Byzantium in Venice, ca. 1200–1400. In San Marco, Byzantium, and the Myths of Venice. Edited by Henry Maguire and Robert S. Nelson. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, pp. 193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Holger A. 2013. Die Staurothek Kardinal Bessarions: Bildrhetorik Und Reliquienkult Im Venedig Des Späten Mittelalters. In “Inter Graecos Latinissimus, Inter Latinos Graecissimus” Bessarion Zwischen Den Kulturen. Edited by Claudia Märtl, Christian Kaiser and Thomas Ricklin. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, vol. 39, pp. 245–76. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Holger A. 2017. Cardinal Bessarion, Philippe de Mézières and the Rhetoric of Relics in Late Medieval Venice. In La Stauroteca Di Bessarione Fra Constantinople e Venezia. Edited by Holger A. Klein, Valeria Poletto and Peter Schreiner. Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, pp. 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lauber, Rosella. 2017. Cultural Exchanges in Venice, for an Artistic ‘Archive of Memory’: New Contributions on Gentile Bellini, Bessarion, and the Scuola Grande Della Carita’, through Michiel’s Notizia. In Padua and Venice: Transcultural Exchange in the Early Modern Age. Edited by Brigit Blass-Simmen and Stefan Weppelmann. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Majeska, George P. 2004. The Relics of Constantinople after 1204. In Byzance et Les Reliques Du Christ. Edited by Jannic Durand and Bernard Flusin. Paris: Association des Amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance, pp. 183–90. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, Karen R. 2018. Emulation of and Appropriation from Byzantium in Venetian Visual Culture. In Conflict, Commerce, and an Aesthetic of Appropriation in the Italian Maritime Cities, 1000–1150. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 72–109. [Google Scholar]

- Pentcheva, Bissera V. 2017. Phenomenology of Light: The Glitter of Salvation in Bessarion’s Cross. In La stauroteca di Bessarione fra Constantinople e Venezia. Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, pp. 257–87. [Google Scholar]

- Perocco, Guido. 1984. Venice and the Treasury of San Marco. In The Treasury of San Marco, Venice. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus, Debra. 1992. Venice and the Two Romes: Byzantium and Rome as a Double Heritage in Venetian Cultural Politics. Artibus et Historiae 13: 101–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polacco, Renato. 1992. La Storia Del Reliquiario Bessarione Dopo Il Rinvenimento Del Verso Della Croce Scomparsa. Saggi e Memorie Di Storia Dell’arte 18: 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Voulgaropoulou, Margarita. 2019. From Domestic Devotion to the Church Altar: Venerating Icons in the Late Medieval and Early Modern Adriatic. Religions 10: 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurthmann, William B. n.d. Venice Scuole. In Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).