Abstract

This article discusses the role of artistic interventions in shaping communities in selected Polish cities. It especially explores marginalized urban areas that are gaining new identities through art. A crucial aspect of the analysis concentrates on the influence of artistic activities on the formation of social bonds. Moreover, it focuses on the revitalization strategies that incorporate artistic activities designed to beautify spaces and enhance residents’ sense of security. It also includes examples of grassroots initiatives undertaken by artists in degraded areas. This study employed a qualitative methodology. In addition to reviewing the literature, a comparative analysis of case studies encompassing murals, site-specific installations, graffiti, and participatory art was conducted. The selected case studies demonstrate that art is not merely an esthetic endeavor but an important tool for solving spatial and social issues. Artists’ activities in difficult areas of a city lead to perceptual, visual, and functional changes. However, the question was whether the process of co-creation with the local community translated into stronger neighborly relationships or a greater sense of security.

1. Introduction

Artistic actions revitalize forsaken and neglected areas, transforming them into spaces for encounters, interactions, and dialog. They are also associated with aestheticization. The use of artistic activities for urban regeneration varies according to the political and economic conditions. In the United States and Western Europe, concepts such as creative placemaking (Markusen and Gadwa Nicodemus 2010) and cultural districts (Murzyn-Kupisz 2012) have become prevalent. Creative placemaking involves the use of culture and art in the deliberate transformation of the environment in collaboration with the local community. In this case, the potential and resources of space users are focused on creating spatial development concepts or actively participating in changing them to suit their needs. The given approach involves various actors in the co-design process, including the public and private sectors, nonprofit organizations, and direct users. A cultural district, on the other hand, refers to a clearly defined area of a city where a diverse range of cultural and artistic activities are implemented through grassroots or top-down initiatives, both private and public (Roodhouse 2010, p. 24). In Europe, examples of such neighborhoods are often located in post-industrial areas or at a distance from the city center. These types of districts are typically characterized by poor infrastructure and esthetics, as well as safety problems. However, they are also characterized by excellent spatial, architectural, and historical potential. Therefore, as a result of multidimensional remedial measures, a new layer of meaning and culture is “imposed” on the historic urban fabric, leading to the regeneration and new image of the area.

In both creative placemaking and cultural districts, a common element is a reference to the artistic potential of people and locations. However, distinctions between the two are evident in their aims, scope, and institutional structures. In the case of creative placemaking, participatory tools play a crucial role. This aligns with the idea of “meaningful participation” promoted by the UN Habitat. (United Nations 2016). Given approach, combined with creative actions, increases the potential to stimulate community involvement. Consequently, this translates into concrete and tangible changes. The principles of creative placemaking are not always reflected in field practice. Therefore, there is no shortage of critical opinions on these activities (McKinnon and Schrag 2021). The model proposed by Florida for attracting talent and creating creative districts carries, as Peck notes, the risk of gentrification and spatial polarization (Peck 2005). Henri Lefebvre’s theory provides a more beneficial solution. It assumes the democratization of urban space, that is, the joint shaping of the environment by residents (Nadolny 2015). Although Western literature is usually critical of the neoliberal tendencies of creative placemaking (Zukin 2010; Markusen and Gadwa Nicodemus 2010), few researchers have addressed the issue of EU structural funds. This phenomenon has significantly affected the nature and direction of many artistic interventions in post-socialist cities. The hybrid model proposed in Poland is crucial for this purpose. This combines Florida’s theory of growth with Lefebvre’s concept of participation. Simultaneously, it considers grassroots artistic initiatives as well. Thus, this article contributes to the international debate on the role of art in revitalization, with particular emphasis on post-socialist centers.

In this study, public art is understood broadly. First, it refers to activities carried out in publicly accessible urban spaces, such as streets, courtyards, and squares. These include grassroots and structured, institutional interventions initiated or commissioned by public entities and implemented in cooperation with NGOs. Adopting such a broad definition allows for the analysis of a wide range of diverse phenomena, from spontaneous murals, through artistic co-production and ephemeral activities, to large-scale artistic projects covering entire neighborhoods as part of revitalization strategies. As a result, two different models of the emergence of art in public spaces were discussed. First, artistic projects that are part of well-thought-out revitalization efforts in the degraded parts of Polish cities were presented. Next, examples of grassroots, spontaneous activities resulting from the initiatives of artists and the local community were provided.

1.1. Urban Regeneration in Poland and Post-Socialist Europe

In addition to different urban strategies and policies, Poland and other post-socialist European countries faced challenges in the 21st century, such as the layered effects of years of neglect degrading urban space, the spatial and economic consequences of the rapid industrialization of the previous era, and mass housing construction, such as Budapest’s District VIII and Prague’s Žižkov (Petaccia and Angrilli 2020). The Revitalization Act, introduced in 2015, was the first document to regulate regenerative processes in Polish cities. According to its wording, revitalization was a comprehensive process of bringing degraded areas out of crisis through integrated actions, benefiting the local community, space, and economy (Revitalization Act of 9 October 2015 n.d.). Although it was multifaceted, particular emphasis was placed on the social aspect (Ciesiółka and Maćkiewicz 2020).

Although revitalization projects carried out in Poland and Western Europe shared many common elements, the differences between them centered on social specificity. In Poland, efforts have focused on social integration and community building, whereas in Western countries, revitalization has often concentrated on issues of migration and ethnic diversity (Masierek 2021). To address social, economic, and esthetic needs, the Polish Revitalization Act of 2015 created a hybrid model (Petaccia and Angrilli 2020). It assumed a combination of bottom-up and top-down approaches for planning and implementing revitalization activities and public participation. However, a large number of projects, sometimes as much as 78%, relied on EU cohesion funds, which required private partnerships, often favoring the interests of developers at the expense of local communities’ needs (Ciesiółka and Burov 2021).

Revitalization programs in Poland have faced numerous challenges. Among them are art projects, which sometimes contributed to an increase in real estate prices in a given neighborhood by up to 240% (2004–2019), leading to the displacement of low-income residents without providing them with adequate protection (Murzyn-Kupisz 2012). In Western cities such as Berlin, regulations have been introduced to protect residents through the use of rent caps. Meanwhile, actions that directly impact residents instead of protecting them, although inconsistent with the objectives of revitalization projects, are common. Indeed, revitalization’s primary goal is to counteract both social and spatial marginalization (Roberts and Sykes 2000). In Poland, although the Revitalization Act of 2015 mandates comprehensive measures, esthetic projects (murals and festivals) that do not address social problems dominate. A similar situation exists in other Eastern Bloc countries, such as Budapest, where the Tűzraktér replaced an independent cultural center with commercial spaces (Czirfusz 2015, p. 92).

When analyzing the role of art in the revitalization of post-socialist cities, it is also important to mention the phenomenon of “shrinking cities”, and, in particular, and in particular the artistic and cultural programs designed to counteract it. One of the strategies adopted by artists is, for example, the temporary use of abandoned buildings and the organization of exhibitions or community art initiatives there. Such activities contribute to the revitalization of shrinking neighborhoods and bring about real changes focused on the well-being of the local community rather than economic potential. Examples include projects carried out by artists in collaboration with NGOs in cities such as Oberhausen and Riga. They highlight the scale of opportunities behind such alternative strategies. To a much greater extent, they offset the risk of commodification and exclusion. As Matyushkina underlines, they “have the potential to contribute to the sustainable development of shrinking cities, as they capitalize on local resources, and center around the acute needs of local communities” (Matyushkina 2023).

Interdisciplinary art projects can also be a tool for criticizing urban policy, as demonstrated by the Shrinking Cities program, funded by the German Cultural Foundation (2002–2008)1. Since 2002, more than 200 artists, architects, scholars, and local interest groups have participated in this program. As a result, numerous exhibitions, publications, and actions took place in public spaces. They addressed the issue of depopulation and promoted new, participatory models of city management. At the same time, attention was drawn to the possibility of using art as a tool for reflection, debate, and counteracting urban marginalization.

1.2. The Role of Art in Public Space

Art in public spaces constitutes a multi-dimensional phenomenon. According to Kwon, we can talk about art in public places, art as a public space, or art created in the public interest (Kwon 2004). Given the subject matter of this study, it is appropriate to focus on the last category. A shortcoming of art created for the public interest consists of its ephemeral nature. Nevertheless, numerous examples of such artistic interventions indicate that they can contribute to increasing awareness and resolving many problematic issues. In this sense, the artist becomes an intermediary who creatively and engagingly attracts attention, highlights the problem, and inspires change. In this sense, community art gives a voiceless voice and facilitates social transformation (Zhou et al. 2024, p. 5). Art is not only a tool for aestheticization, social animation, and activation. In addition, it influences perceptions of safety (Hall and Robertson 2001). With its appearance, a place loses its neglected and chaotic images. In return, it has the potential to integrate the local community around a program, to “tame” the common space, and to generate social energy, enabling, in turn, the building of a sense of community. (Sharp et al. 2020). Not only do direct users notice this phenomenon, but it also arouses the interest of outsiders, including tourists. Consequently, unfavorable or dangerous incidents are gradually eliminated.

In this context, the artist ceases to function as an authoritarian creator who imposes certain solutions in public space. By approaching, cooperating with, and co-creating with the local community, he becomes a guide who inspires and encourages action. Suzi Gablik, in “The Reenchantment of Art”, points to the necessity of the artist’s return to a kind of spirituality and empathy as the foundation of artistic activity. She emphasizes that the goal of true art is social transformation, which can contribute to the healing of both individuals and communities. The author encourages artists to create with a spirit of cooperation, openness, and authenticity. Such an approach fosters the building of interpersonal bonds and deepens reflection on a place and its inhabitants (Gablik 1991).

A particular risk of participatory activities constitutes failure to consider differences within a given community. Instead of meeting their real needs, this may result in the perpetuation of inequality (Kwon 2004). For instance, according to Kwon, Chicago’s Culture in Action exhibition, which approached participants as simplistic identities, did not contribute to solving systemic social problems but only perpetuated stereotypes (Kwon 2004). Claire Bishop also highlighted the dangers of social participatory art, particularly its uncritical praise (Bishop 2012). The researcher stresses that projects of this type are often judged according to ethical criteria (e.g., inclusivity) rather than artistic ones. Thus, interventions appear to be visually appealing but do not lead to real change because they do not consider the voices of marginalized groups, at the very least. Hence, as Kester suggests, the most optimal solutions emerge from grassroots collaborations, as they directly focus on the challenges faced by the target group. He also points out that we should move from art “for” the community to art “with” the community, where participants co-create the process of art-making (Kester 2014).

This study aims to provide an in-depth analysis of eight examples of artistic interventions in selected Polish public spaces. The primary objective was to evaluate the impact of art on community shape. The chronological framework predominantly covered the past 15 years.

Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed:

- Artistic interventions in public spaces contribute to strengthening social ties and building community.

- Artistic interventions in public spaces contribute to enhancing the subjective sense of security and well-being of the user.

The results of the analysis indicate that artistic interventions in the public spaces of Polish cities strengthen social bonds but simultaneously carry the risk of exclusion if not accompanied by a long-term, thoughtful housing or social policy. These conclusions advocate for hybrid action models in revitalization programs.

2. Results

Artistic interventions in public spaces constitute part of official revitalization programs as well as many grassroots efforts. The following are selected examples of bottom-up and top-down initiated activities, as well as those undertaken by artists in collaboration with the local community, with the aim of visual transformation, renewal of a specific area, building ties, and fostering dialog. The examples of interventions have been sorted according to the assumptions in the research hypotheses. In the following analysis, each artistic intervention is considered in terms of its impact on building social bonds (Hypothesis 1) and improving the subjective sense of security and well-being (Hypothesis 2). Additionally, each case was assigned an intervention type (grassroots, participatory, institutional, municipal) to highlight the diversity of action forms. Furthermore, Hypothesis 1 includes projects implemented as a result of revitalization efforts, in cooperation with NGOs, artists, and local residents. In turn, Hypothesis 2 presents projects implemented as a result of grassroots initiatives by NGOs and/or artists. Each project presented below was accompanied by a short description and objective. The issue of public involvement is discussed in turn, along with its social and spatial effects.

Hypothesis 1.

Artistic interventions in public spaces contribute to strengthening social ties and community building.

2.1. Szczecin—Downtown Mosaics Project (Part of the Revitalisation Program/Municipal Intervetion with the Participation of NGOs, Artists, and Local Community)

The Downtown Mosaics project in Szczecin, an initiative of the Oswajanie Sztuki Association and City Council, was created as part of the revitalization efforts launched in 2018. The primary objective was to regenerate areas of the city that were perceived as dangerous, neglected, or unattractive. To this end, the potential of local artists, residents, and activists was harnessed.

Szczecin, located in the West Pomeranian Province, was mainly shaped in the 19th century but was heavily affected by the war. Nevertheless, it has remained primarily associated with the shipbuilding industry. However, after its decline in 2000, the city began to enter a crisis, resulting in an increase in unemployment and depopulation. An urban revitalization program was designed to address these problems. Among the planned activities was the “Downtown Mosaics” project, which was implemented primarily in neglected backyards2. The project was based on interactions between initiators and recipients. They both selected murals and canvases and collected ceramic materials, including old plates and bowls. The residents also decided on the design and participated in laying mosaics (Krawczak 2023). The decision to choose such materials as artistic mediums was also crucial. They are durable, water-resistant, do not fade, and are much harder to destroy (Krawczak 2023, p. 109). The choice of backyards as sites for artistic intervention was not accidental as well. The artists and educators who initiated the project stressed that backyards are natural meeting places and hence should be cared for. Culture and art, on the other hand, are ideal tools and, at the same time, pretexts for meetings.

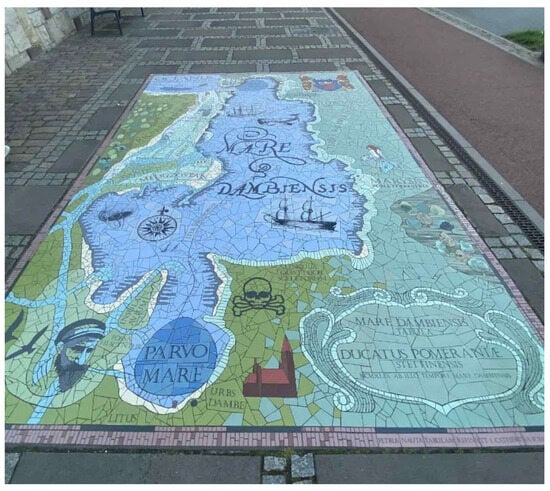

The accuracy of the concept and popularity of the idea are reflected in the two-part mosaic map created in cooperation with residents. It contains suggestions for walking paths along the mosaic trail, during which one can see not only new but also historical artworks. This is related to Szczecin’s numerous translations of mosaics in the post-war period (1945–1989), commissioned by private and public institutions. After 1990, mosaics appeared through initiatives by cooperatives, residents, artists, city authorities, and entrepreneurs. The latest mosaics feature maritime themes or natural, local spots and landscapes, as well as common topics (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The Mare Dambiensis mosaic by Justyna Budzyn. Szczecin.

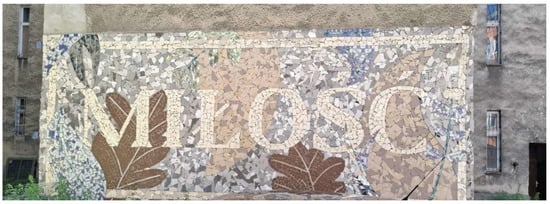

Figure 2.

Love mosaic by Stowarzyszenie Oswajanie Sztuki. Szczecin.

Revitalization measures in Szczecin, including artistic ones, translated into a greater sense of community and a stronger local identity, aligned with the program’s objectives. As Kinga Rabinska, the project manager of Mosaics, underlined: “we consider it our mission to create more and more opportunities to meet with the help of art and culture and thus to build our community”. “Our goal is to encourage people to think about the built environment surrounding them–about the buildings, public spaces, their backyard, streets, stairs, their neighborhood and all in all about the entire city”, she added (Vikárius 2020). Szczecin mosaics have also improved the visual appeal of the sites and, consequently, tourist interest.

2.2. Nadodrze Colorful Yards (Part of the Revitalisation Program/NGOs Intervention and Local Community)

The revitalization of Wrocław’s Nadodrze District began in the 1990s, although the actual renewal program was not implemented until 2009 (Jabłoński-Weryński 2020, pp. 70–71). Numerous top-down and bottom-up activities have been conducted in recent years. Despite these measures, the area was still associated with insecurity, crime, and poverty. It also remained visually and symbolically distinct from the rest of the city. The situation needed to be changed, given that Nadodrze is located not far from the historic city center and Ostrów Tumski (Cathedral Island). According to the data gathered by many official municipal authorities, the main problems noticed in Nadodrze included the weak role of neighborhood networks, lack of identification with the place of residence, passivity of residents, partial exclusion of some social groups (e.g., national minorities), and crime (Dębek and Olejniczak 2015, p. 13).

Therefore, the goal of the revitalization program focused not only on the beautification of the area but also on instilling a sense of responsibility in residents. It also encouraged them to take action in a common space. The concept was to transform Nadodrze into an arts and crafts center that would be friendly to various businesses (Wroclaw 2016). To this end, the OK! Art Foundation initiated the implementation of long-term creative projects involving local communities in Wroclaw’s urban space. Among the most notable projects one may find “Colorful Backyards,” which transformed intricate urban interiors between neglected old tenements into artistic, colorful spaces (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). Consequently, two murals were brought to life in Wrocław’s Nadodrze district: “Backyard–Our Atelier” (2014–2015) and the “Backyard–Discovering Art” (2016–2017). The project began by establishing connections with local communities. First, artists from the OK! Art Foundation and animators from the Backyard Cultural Animation Center began creating free portraits for residents. During the process, conversations ensued, and with them, trust. Then came the time for art workshops, through which the target designs of the murals and murals themselves were created. The initiators aimed for the final result to be a visual representation of the residents rather than a creative expression by artists (Wroclaw 2016, pp. 84–85). Therefore, at each stage, they paid special attention to the quality and building of relationships with users. Meetings with artists enabled residents to express their ideas and needs while learning new skills.

Figure 3.

Murals that are part of the Colorful Backyards project by OK! Art Foundation.

Figure 4.

Murals that are part of the Colorful Backyards project by OK! Art Foundation.

Figure 5.

Murals that are part of the Colorful Backyards project by OK! Art Foundation.

Both mural projects consist of many diverse motifs. In the Backyard—Our Atelier project, motifs related to creativity and crafts are featured, including easels, paints, brushes, and images of children and adults engaged in painting and drawing. The whole is kept in warm, bright colors. In contrast, the theme of the Backyard–Discovering Art Project is to experience and learn about various forms of art. Hence, there are references to famous artists (Van Gogh, Munch, Chagall, and Frida Kahlo), their quotes, and interpretation of classical art works. Residents’ portraits also appear there. Some fragments express the individual creativity of the residents. They are directly related to their lives, interests, and passions. The mural, a combination of painting, sculpture, and ceramic elements, is characterized by its vivid and intense colors.

As a result of the project and the long-lasting process, the image of Nadodrze improved. The murals have become a popular tourist destination in Wroclaw. Although this aspect has its advantages, it is cited in conversations with residents as a drawback, with a “tiring” and “irritating” effect. Therefore, there are even some cards placed in the windows and on certain parts of the murals, which ban photography and even “looking in.”

2.3. Gdansk—Lower Town Districts (Dolne Miasto) (Part of the Revitalisation Program/Municipal and Institutional Intervetion with the Participation of Artists and Local Community)

The Lower Town District project in Gdansk was created as part of a revitalization project co-financed by the Regional Operational Program for the Pomorskie Voivodeship for the years 2007–2013. The program’s primary objective was to revitalize degraded areas of the city, including public spaces. It was equally important to improve the challenging socioeconomic situation of residents.

The Lower Town District, situated close to the historic center, was not destroyed during the war. Therefore, it was characterized by great potential. However, over the years, the district has remained neglected and isolated. The buildings located there have fallen into disrepair, and no new construction projects have been undertaken.

Among the 210 tasks carried out under the revitalization program, some exploited the potential of art. As a first step, the historic city bathhouse building was adapted to house the Laznia Center for Contemporary Art, which began undertaking many activities for and with the residents of the district (Wołodźko 2017). One of its many initiatives concentrated on the creation of the Outdoor Gallery of the Lower Town, intended as an outdoor and publicly accessible collection of artworks. These included sculptures, installations, sound and light shows, visual projections, and paintings. Many art projects implemented within the gallery were created on the symbolic boundary line in the spaces separating the Main City from the Lower City (Wojtowicz-Jankowska 2019). Their realization was carried out in cooperation with artists, architects, scientists, urban planners, and, above all, the residents of the Lower City. Among the most popular projects is the Invisible Gate by the Front Studio Group, a mirror installation designed to bridge the physical and symbolic division between the old and lower towns.

The artistic potential generated during the revitalization process in the Lower Town has gradually attracted additional initiatives that align with the area’s creative agenda and its character. These include the international art platform Corners, which created site-specific works in collaboration with residents in May 20173. Their projects were mostly temporary and ephemeral, but they managed to engage the local community through sound installations, videos, photography, performances, interviews, and workshops. These, as well as many other projects organized during the two-week activities, were created in dialog with the audience—residents—who had a tangible impact on the final shape of the works and the events. Their diversity and form of implementation (along with the local community) have attracted many users. This way, the artists managed to reduce the distance and establish closer bonds with the residents. Residents of Dolne Miasto still remember these events and talk about them in a highly positive manner, which was echoed in almost all of the conversations conducted by the author.

The artistic interventions implemented in Gdańsk’s Lower Town changed the district’s perception. In several cases, they beautified the space. They also enabled the transformation of a previously neglected part of the city into a safer and more attractive area for both residents and tourists, as evidenced by numerous tourist offerings and city forums.

2.4. Lodz—Księży Młyn (Part of the Revitalisation Program/Municipal Intervention and Local Community Engagement)

Księży Młyn in Łódź is a 19th-century workers’ settlement initially associated with a spinning mill. The entire complex also includes a factory store, fire department, hospital, school, factory director’s villa, and three palaces. Over the years, the area has been neglected, and the buildings have required many repairs. Therefore, mainly people with low income levels lived there (Łódź City Council 2012). The project to revitalize the complex, which was financed, among other sources, by the city budget and EU funds, began in 2012. The main goal of the program was to “to create and develop a space friendly to both residents and visitors and to intensify its use through the introduction of appropriately selected functions and spatial solutions while preserving the historical and cultural values” (Łódź City Council 2012, p. 14). According to the residents, the area needed improvement in terms of cleanliness and esthetics. At the same time, alcoholism, hooliganism, vandalism, and poverty were listed as the most pressing problems (Łódź City Council 2012, p. 11). In the first stage of revitalization, activities focused on building trust among residents, strengthening ties, and fostering a willingness to cooperate on the concept of Księży Młyn. To this end, meetings, cognitive mapping workshops, and exhibitions of photos of Księży Młyn taken by residents and others were organized (Zając 2015).

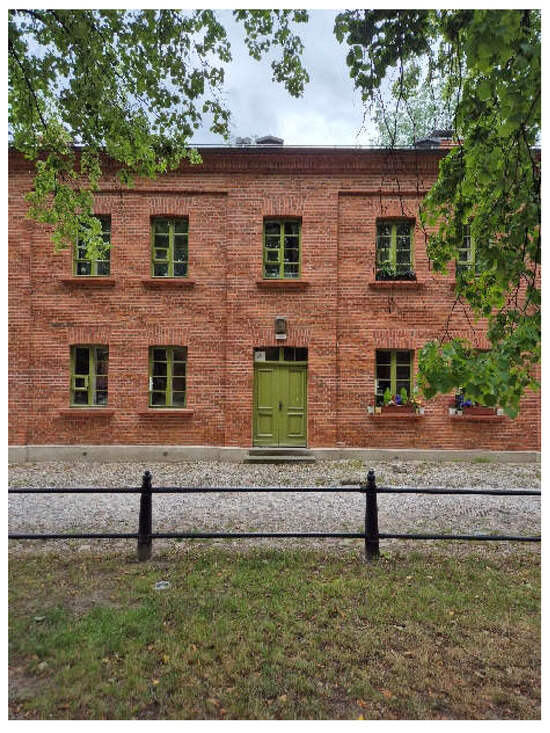

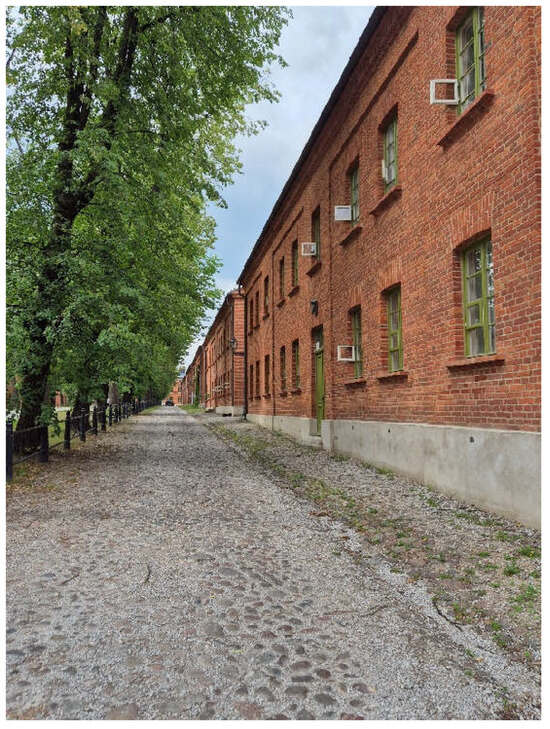

Revitalization was based on the consistent shaping of the image of the area as a creative district. Therefore, art studios were launched that remained open to residents and tourists (Open Studio Days have been organized since 2024). An Art Incubator, an innovative art development center that supports young artists by offering them space to work, exhibit, and organize events involving the local community, was also established. Revitalization included the aestheticization of space, focusing on courtyards, walking trails, and plazas. As a result, Księży Młyn has won numerous awards and is recognized throughout the country as a trendy and vibrant neighborhood of Łódź (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Księży Młyn after revitalization.

Figure 7.

Księży Młyn after revitalization.

Despite many positive changes, the reports also highlight flaws and risks, such as the short-lived nature of the implemented social activities (Łódź Province Management Board 2024, p. 12) and the lack of consideration or insufficient consideration of the technical condition of housing units in revitalization activities (Łódź Province Management Board 2024, p. 91). A notable concern refers to an excessive focus on improving the visual attractiveness of buildings (facades). In addition, a number of residents did not decide to return to the renovated premises because of their reluctance to relocate again and financial issues (higher rent) (Łódź Province Management Board 2024, pp. 90–91). However, conversations with residents revealed that they were satisfied with the revitalization program and the housing conditions created for them. They are also proud of the results and the considerable popularity of the area.

Hypothesis 2.

Artistic interventions in public spaces contribute to improving residents ‘subjective sense of security and well-being’.

2.5. Lodz—“The Excluded Have a Voice” (Grassroot Initiative)

An example of grassroots activities (created on the initiative of an informal group) in Łódź is the 2021 Excluded Have a Voice Project, funded by the city’s microgrant program. The project targeted the wards of the probation center located in the vicinity of a renovated factory, which is currently a shopping and entertainment center. In this case, public space served as a medium through which previously excluded people could make their presence known. The project consisted of anti-exclusion workshops and collaboration during the creation of the mural: preparation of a concrete fence canvas, followed by creative work on stencils (in cooperation with the Academy of Fine Arts) (Grzyś 2024, pp. 219–21). The wall chosen as the backdrop for this project deteriorated and formed a clear spatial division within the courtyard. Therefore, the aim was not only to beautify the space but also to visually eliminate this impression. The murals improved the visual appearance of the courtyards. However, their social dimensions turned out to be much more significant. The work was carried out by children and young people from a curatorial center with the help of artists. Thus, the mural helped break down social and cultural barriers. The target group was able to make their presence visible in public spaces (Grzyś 2024, pp. 219–21). The two murals are simple but colorful. One depicts plant motifs, while the other refers to the idea of peace in defiance of the war in Ukraine (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

“The excluded have a voice” murals.

During a telephone conversation with the head of the probation center, it became clear that the youth reacted positively to the project. They were eager to participate, especially since the wall in place of the resulting mural was “disgusting” and filled with vulgarities. The joint creation of a new painting and, above all, the opportunity to participate at every stage was attractive and appealing to the youth. Currently, the mural is already deteriorating and is likely to be destroyed as part of the ongoing revitalization program in the area, which aims to transform the location’s image into a more prestigious one4.

2.6. Wrocław—Iza Rutkowska’s Hedgehog (Grassroot Initiative)

Rutkowska’s work is part of a grassroots community art movement. Through her activities, the artist regularly contributes to spatial and social changes. One of her projects, titled “Jeż” (Hedgehog), created in 2015 as part of the “Wrocław–wejście od podwórka” (Wrocław–entrance from the backyard) initiative, was part of the visual arts program of the European Capital of Culture (Rut 2017). It was created in the backyard of a Wrocław housing estate in Przedmieście Oławskie, a neglected and notorious neighborhood. The primary goal focused on the creation of artwork that would address the needs of the local community and be dedicated to it. First, the artist selected a location and spoke to the residents. This allowed her to better understand the expectations, needs, and problems they faced. From these conversations, the concept of a large-format hedgehog mascot emerged. It was intended to serve as a pretext for further encounters among adults and as entertainment for local children. The artist also wanted to “domesticate” this space. This was particularly important given the neglected nature and visually unattractive condition of the area itself. Therefore, residents were reluctant to spend time there, which hindered their integration.

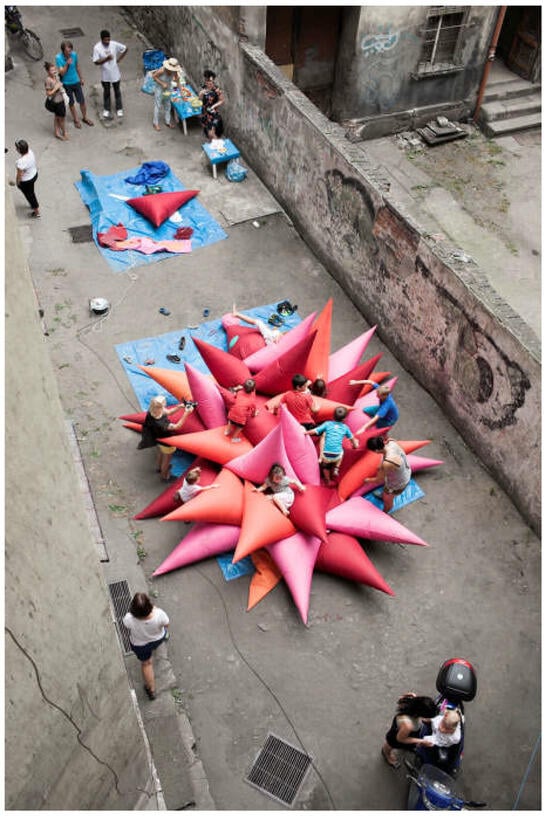

The Hedgehog was made of more than a dozen colorful small pieces constructed and installed by the artist and residents (Figure 9 and Figure 10). The 8 m-long, colorful mascot encouraged children to go out into the yard and play. You could jump on the Hedgehog, cuddle up to it, and lie down on it (Figure 11). As complementary activities, animated films about hedgehogs were screened, and drawings and tattoos with a hedgehog motif were created. Due to the popularity of this project, the artist and the children gathered around the Hedgehog managed to raise funds on a public collection basis to continue the project and go on vacation. In addition, the Hedgehog encouraged adults to come out to the courtyard, where they had the opportunity to get to know each other, integrate, and think about the quality of the area and the possibilities for its improvement.

Figure 9.

The Hedgehog by Iza Rutkowska. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 10.

The Hedgehog by Iza Rutkowska. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 11.

The Hedgehog by Iza Rutkowska. Courtesy of the artist.

The project described above did not end in 2015. The artist herself emphasizes that she has been constantly monitoring and leading the process for ten years, first with various cultural institutions and then with the Department of Social Affairs. She also continued to work with residents5. Owing to their actions and determination, in 2024, a project for the backyard (construction of a playground, multifunctional area, and outdoor gym) was financed by the Wrocław Civic Budget program, which was named the Backyard of All Residents (Figure 12). In a few days, a celebration will be held to commemorate the opening of the first part of the courtyard and to announce the start of the next construction work. Performatively, the artist, together with the residents, will green the space and renovate the inscription, Courtyard of All Residents.

Figure 12.

The Backyard of All Residents. Courtesy of Iza Rutkowska.

The long duration and success of the project were only possible because a comprehensive co-design process was followed. Residents, especially leaders, together with the artist, have worked for years in the surrounding area to strengthen local social ties. “I do not engage in artistic intervention; I conduct comprehensive design processes–for me, it is a total difference,” emphasizes Rutkowska6. The artist, along with the residents, conceived the concept of the courtyard’s redevelopment, which was later developed by an architect selected through a tender process. From a bird’s-eye view, the courtyard took the form of a hedgehog designed by the artist, with functional features developed in collaboration with residents. The final design differed slightly from the original version, as it was simplified by architects and officials. However, according to Rutkowska, it was a process, not a design, that led from a small 7 m hedgehog to Podwórko im. Wszystkich Mieszkańców (Courtyard of All Residents), which, when viewed from above, has been transformed into a hedgehog.

Meanwhile, people from outside, who are unfamiliar with the project and find themselves in the courtyard, may not even realize that it is shaped like a hedgehog. However, it remains important to residents. The hedgehog is a symbol of the story that connects them. Consequently, a bond was formed between the residents and the space itself. Rutkowska even underlines that when one of the recreational devices in the courtyard became loose, the residents immediately hid it in the basement so that no one would damage it and then wanted to give it to a subcontractor for repair.

As a result of a long process, a previously unclaimed area was transformed into a courtyard with a specific name, used by a group of people who know each other and treat the place almost as their own, taking care of it and looking after the equipment and devices located there.

2.7. Urban Forms Lodz (Grassroot Initiative)

The Urban Forms Foundation is one of the most critical organizations shaping public spaces in Łódź through art. Since 2008, the Foundation has completed more than 149 murals and art installations in Polish cities. During the Urban Form Festival, which was organized periodically (the last edition was held in 2018), workshops, picnics, meetings with artists, and educational activities were held, in addition to the creation of new street artworks on selected walls. Projects implemented by the Foundation were developed in close cooperation with residents and local activists. Activities included the Open Gallery of Young Art, which allowed young artists to showcase their work in public spaces such as underpasses while attempting to transform the esthetics of neglected spaces (Figure 13 and Figure 14). However, the participation of the local community was crucial, as they were involved in selecting the walls and sharing their opinions, which had a tangible impact on the final shape of the artwork.

Figure 13.

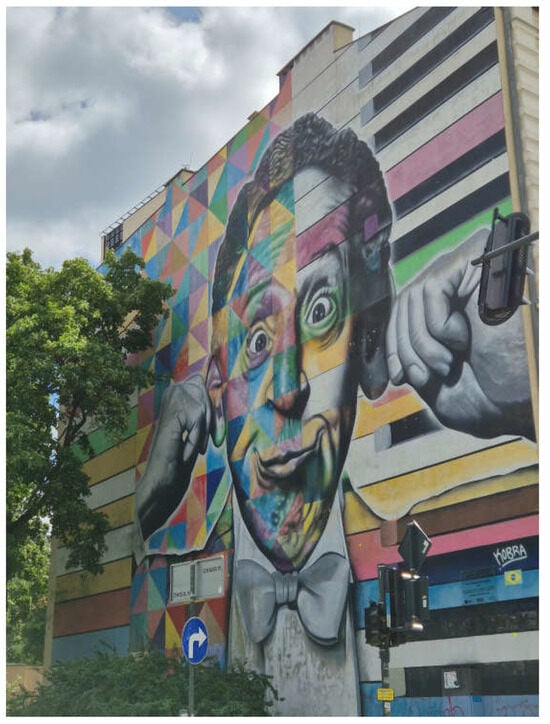

Mural as part of the Urban Forms project. Author: OS GEMEOS (Brazil), ARYZ (Spain).

Figure 14.

Mural as part of the Urban Forms project. Author: Eduardo Kobra (Brazil).

Different studies and reports (Urban Forms 2014) demonstrate that such activities strengthen neighborhood ties, build a sense of pride, and activate the local community. Residents usually approve this type of art concept (Statucki 2019, p. 120). For the most part, they reacted positively to the murals, recognizing that they contributed to the city’s beautification. This aspect is not insignificant, given that it was noted in the 2014 State of the City Report (Łódź City Council 2020, p. 23). Hence, there was no shortage of statements in the survey report that murals serve to beautify the streets, brighten up Łódź, enliven the space, and refresh gloomy areas. Moreover, due to the murals, especially their vibrant colors, Lodz has become much more visually attractive and colorful despite the prevailing “grayness and ugliness” of the neglected streets and tenements around (Łódź City Council 2020, p. 23). This is also reflected in the tourism industry. Until recently, areas that did not arouse much interest have become tourist destinations due to art in Łódź public spaces (Mokras-Grabowska 2015, p. 26).

2.8. Warsaw Bródno Sculpture Park (Combining Grassroot and Institutional Initiative)

The idea of creating the Bródno Sculpture Park originated from the efforts of several entities. These included local officials from Warsaw’s Targówek district, Polish artist Althamer, and the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. Targówek is a peripheral district in Warsaw. It was considered the poorest part of Warsaw during the post-war period. In the 1970s, large housing blocks were built in a given area, which significantly altered their appearance, as well as the 22.5-hectare park. In 2009, Poland’s only Sculpture Park was initiated on its grounds as part of a grassroots initiative (Figure 15 and Figure 16). It was intended to be a community park. Therefore, it should engage local users and nurture connections. Moreover, the originators wanted art to be accessible to everyone.

Figure 15.

“Zinaxin i Dolacin” sculptures by Magdalena Abakanowicz, Bródno Sculpture Park.

Figure 16.

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Untitled (overturned tea house with the coffee maker).

The works placed in the park are both permanent and lasting, as well as ephemeral and impermanent. Some are created by artists, while others are created by the residents themselves. Among them are poems written on the asphalt of some of the park’s alleys and mosaics set in the rhythmic structure of concrete slabs. There is also no shortage of performances, such as that of artist Honorata Martin, who lived in the park for several weeks to realize the performance “Domestication”7.

According to local animators, art interventions have an excellent impact on nearby residents. They facilitate the involvement of the local community and encourage them to become more active (What should Bródnowski Park be like? Urząd Miasta Warszawy 2017).

However, the report from the public consultation (What should … 2017) directs attention to another aspect. Sculpture Park is undoubtedly a valuable element of the park, but there were also critical voices among the residents. Criticism was directed at the lack of homogeneous concepts and communication (What should … p. 105). The lack of sufficient information about the sculptures, as well as their incomprehensibility and alienation, was also highlighted (What should …, pp. 24, 74). Some were even received as offensive, ugly, and sloppily made, or placed haphazardly enough to occupy space that could be used for something else.

The initiator of the Sculpture Park, Polish artist Pawel Althamer, argues that the space is meant to be a form of play with the residents, hence its multi-layered nature, as well as the lack of a plan with a legend or information about the sculptures. Indeed, the goal should be to discover and experience the park and sculptures gradually (What should…, p. 54). Art historian and curator Stanislaw Ruksza, defending the idea, points out that the most important qualitative feature of the idea of the park is its open form, which does not reduce the successively created works to an “everlasting” monument but consciously draws on the traditions of minimalism and participatory practices8. The sculptures are not created with one overarching or specific raw material in mind; they are a dynamic response to context, time, and place, and last but not least, the sphere of ideas prevails over matter—he adds.

3. Discussion

Artistic interventions included in revitalization programs are characterized by faster implementation and greater financial outlays. They also cover larger areas and have a greater impact. In contrast, grassroots projects are more flexible. Their nature and direction of action are constantly modified and adapted to meet current needs and conditions. However, the scope of these activities is often more limited, and less financial resources force initiators to impose time, space, or material restrictions. The two types of models presented are not mutually exclusive and can be combined. They can complement and reinforce one another. In practice, we observe the evolution of initiatives, starting with participatory methods in grassroots projects to publicly funded revitalization programs. Certain feedback loops were also observed. Community participation in official projects builds trust and can lead to subsequent grassroots initiatives. This creates a new field of dialog. Despite their differences, both approaches are elements of the same urban ecosystem. Their complementarity lies in the possibility of mutual learning and the exchange of knowledge and experiences. Effective revitalization draws on grassroots practices, while grassroots initiatives can gain greater support and expand their reach by entering into relationships with institutions and municipalities. An analysis of both forms of artistic intervention—as in this study—provides universal guidelines and models that can be applied in other cities and countries, including outside Poland.

3.1. Artistic Interventions as a Tool for Social Dialog and Social Agency

An analysis of selected art interventions in public spaces has demonstrated that they are valuable tools for fostering social empowerment among residents. This is particularly evident in projects involving local communities in all phases (diagnosis, creation, and evaluation). Social participation, implemented from the conceptual phase, as seen in the instances of “The Excluded have a voice” in Łódź, “Colorful Backyards,” and the Rutkowska project in Wrocław, provides a significantly higher chance of successful, lasting spatial transformation. This is also confirmed by the answers provided by the guides of alternative guided tours, according to which there is potential for renewal through street art, as it has a pleasant visual impact and supports areas that might be explored (Cercleux 2021, p. 9).

Murals, especially those created in Łódź and Gdańsk, led to an apparent change in the image of the place. The interest of the press, tourists, bloggers, and the city’s residents has translated into a different perception of not only individual spots but also of whole courtyards and streets. In addition to the visual aspect, social ties were also improved. Due to the numerous workshops and events accompanying the creation of the works, residents, according to interviews (Wrocław, Gdańsk), had the opportunity to get to know each other better, establish closer relationships, and create joint initiatives. In Wroclaw, for example, allowing residents to participate in the creation of works translated into the initiative’s popularity and durability. However, co-creation in these cases would not have been possible without the long preparatory process of building trust, forming bonds, and educating users. Therefore, as emphasized by Jadwiga Charzyńska, former director of the Łaźnia Center for Contemporary Art in Gdańsk, the beginning of the concept of the Municipal Gallery in Gdańsk was directly related to the educational program to “familiarize” future users with the proposed changes in public space (Draganovic et al. 2013, p. 16). Therefore, a participatory approach seems particularly important for the success of artistic projects. Ignoring the audience at an early conceptual stage or during implementation carries the risk of rejection or negative reactions. The implementation of Szczecin’s mosaics has created new meeting places. Moreover, mosaics and co-creation processes have restored the meaning and social functions of former courtyards. Thus, the implementation of artistic projects reveals their potential to build social bonds and strengthen local identities. However, this process should include sincere and attentive dialog with the local community. This was emphasized by Kyong Park, who believes that artists, architects, and communities play a key role in the regeneration of cities facing deindustrialization and depopulation. The author draws particular attention to the legitimacy of such cooperation, as it contributes to visual and physical spatial change. An important factor in this context is the emphasis on strengthening the sense of belonging and creating new forms of dialog and cooperation. In this way, art becomes an important tool for revitalization, encompassing both space and the lives of residents (Park 2005).

The collective rights of all inhabitants, as proposed by Lefebvre (Lefebvre 1974), to mold, experience, and reinterpret urban space consistent with their requirements and ambitions, was mirrored in all of the above-mentioned projects, through which residents subdued their immediate vicinity, leading to its reinterpretation and remodeling according to their needs. Bond building, dialog, and participation translate directly into burgeoning community involvement, which in turn enables the efficient redefinition of urban space and encourages other groups to do the same. The Rutkowska project best illustrates this approach. This also confirms John Dewey’s thesis that esthetic experience is a process embedded in daily life, not a detached contemplation (Dewey 1934). A similar concept guided the Lodz project, where young individuals at risk of social exclusion demonstrated their visibility and presence through art. The same can be applied to the “Colorful Courtyard” project in Wrocław, where the initiators aimed to bring art closer to people, not only through artistic education but also through practical and creative means. The most important aspect of the process was everyday conversations, which later developed into artistic activities. In both examples, socially excluded people had the opportunity to express themselves and, through art, show their experiences, emotions, or opinions. Moreover, such creative activities effectively reduced social isolation and feelings of exclusion, such as in Dolne Miasto in Gdańsk. In turn, the involvement of residents in the process of designing and creating works of art, as well as the openness of outdoor events, fostered the creation of new neighborhood connections.

Revitalization programs in Poland have contributed to the aestheticization of space and an increased sense of security. According to the majority (70%) of respondents from municipalities included in the revitalization process in Lodz, the measures implemented have significantly improved the level of security (Łódź Province Management Board 2024, p. 56). Similar data can be found in evaluation studies on the impact of revitalization measures from 2014 to 2020, indicating that increased security is the most pronounced change observed in revitalized areas (Łódź Province Management Board 2024).

A community that begins to notice and cooperate with each other contributes to changing the perception of space from an unsafe place to a tamed and thus much safer, “familiar,” “our” place. According to residents of Lodz, a building “decorated” with a mural can be a source of new identity formation and be treated as a common good, stimulating care for the immediate space (Statucki 2019, p. 112). The renewal of architecture, improvement in cleanliness, lighting, and new facilities primarily influence the sense of security. However, in interviews conducted with users in revitalized areas, a recurring statement emerged. The presence of murals, art installations, sculptures, and new urban furniture also contributes to an increased sense of security. Art reduces the “no man’s land” space, which, according to the “broken windows” theory of Wilson and Kelling, generates a sense of insecurity and promotes the escalation of crime (Kelling and Wilson 1982). The incidents of vandalism in public spaces have significantly decreased in Wrocław’s Nadodrze district and Rutkowska’s backyard. Residents of these areas demonstrate a high degree of care for their homes and surrounding neighborhoods (Jaskólski and Smolarski 2020, p. 114). This is because artistic interventions in abandoned, problematic, or degraded places create new forms of social interactions. They function like “eyes” that not only see but also notice and stimulate specific actions. Owing to its size, color, and uniqueness, the inflatable hedgehog compelled residents to reflect and react through play, conversations, and joint spatial activities. As a result, they started taking greater care of the surrounding spaces. Mural Backyard–Discovering Art in Wrocław encouraged interaction with art. Mural–Our Backyard Studio enabled residents to take on the role of artists and interact with art daily. The Sculpture Park in Warsaw sparked discussions about the presence of art in public spaces, its form, character, exhibition formats, and protection.

Referring to the work of Nikos Papastergiadis, it is essential to highlight the significance of art in fostering a sense of belonging, community, and integration of marginalized groups (Papastergiadis 2010). Projects that encourage the community to talk about a place through words or visual symbols have become a medium for shaping and perpetuating local narratives. In turn, narrative and dialog, combined with the creative act and concrete realization in the form of a tangible object, help to take root in a given space and build a lasting “sense of place.” However, art in public spaces does not always have to take a permanent form. The performative project “Domestication” in the Sculpture Park, Rutkowska’s temporary installation, or the ones implemented in Gdańsk, although transient, resonate with such intensity that they initiate enduring social change. This is because they often appeal to multiple senses or go beyond usual patterns through their messages. According to Dewey, this leads to personal and community transformation (Riedler 2024). Temporary workshops, lectures, and art projects carried out during the Urban Forms Festival in Łódź or the Lower Town in Gdańsk by the Corners’ art platform have engaged different generations and people from various social and economic backgrounds through their breadth and unconventionality. Public spaces have begun to function as meeting places for dialog and shared action. Consequently, they fostered trust and social solidarity among the residents. In this way, public spaces began to assume the role of “third places,” playing a crucial part in social life by supporting the formation of social networks and enhancing social capital (Grzyś 2024)—the impact of informal civic initiatives on shaping urban spaces.

3.2. Between Revitalization and Gentrification—Issues and Criticism of Artistic Interventions in Public Space

Artistic interventions undertaken as part of revitalization or grassroots remediation efforts, while usually bringing many spatial, social, and economic benefits, carry significant risks of gentrification and “artwashing.” Richard Florida referred to this concept already in his “creative class” theory. According to him, creators of culture and art attract investment capital, increasing the attractiveness of neighborhoods and promoting economic development in the area. However, while this can bring a variety of benefits, it increases the risk of gentrification (Florida 2012). Rising property values, combined with the increasing cost of living, are prompting existing residents to consider relocating. Not surprisingly, Peck criticized Florida’s concept (Peck 2005). Such effects also contradict the provisions of the 2015 Revitalization Law, which is intended to prevent social and spatial exclusion. Artistic realizations should not be limited to investment magnets. Although it is profitable, it leads to economic stimulation and encourages entrepreneurship in local communities. Nevertheless, as Sharon Zukin and Loretta Lees have pointed out, there is a danger that art in public spaces will result in “art washing” (Zukin 2010). In her book, Naked City, Sharon Zukin points out the risks of revitalization, which entails investment capital, which in turn leads to the loss of the local character of a neighborhood, while at the same time, as a result of progressive price increases, it forces existing residents to move (Zukin 2010). Loretta Lees describes examples of this approach, according to whom the “creative revitalization” of London neighborhoods after 1997 resulted in a displacement of more than 135,000 people (Lees 2020). In this case, artwashing was merely a transitional phase, leading to the transformation of the intervened facilities (social buildings) into luxury apartments. Polish cities also face the problem of artwashing. This is particularly true for EU-funded revitalization programs. Hence, there is a need for a multidimensional and inclusive approach to such projects that considers real conditions and challenges, as well as social, economic, and cultural challenges.

The perception of space is another problem that emerges in relation to artistic interventions in public spaces. Although many of the mentioned projects were positively evaluated, some were also criticized. Bródno Sculpture Park, which received mixed reviews, serves as an excellent example. This aspect is addressed by Bishop (Bishop 2012), who warns against unreflective enthusiasm for participatory art, as it overlooks the real needs and multidimensional identity of local communities. The opinions of residents must not be treated superficially but rather as an indispensable part of long-term community consultations, from which the concrete content and form of actions emerge. Simulating participatory actions to promote ideas for space usually fails. Meanwhile, in the case of funding from the EU and regional funds, esthetic rather than structural measures were preferred by the respondents. A noteworthy example is the Sculpture Park in Bródno, an undertaking led by an artist and officials with substantial support from the museum. However, conversations with residents revealed a lack of sufficient participatory approach when working on the concept of selecting sculptures. Consequently, some sculptures have been misunderstood and criticized. In the case of the revitalization of Nadodrze in Wrocław, although many positive changes have occurred, a significant portion of problems and challenges, such as unemployment, have been overlooked. Although local support centers have engaged a large group of residents through workshops and counseling, these efforts have primarily targeted middle-class working people rather than the intended group. Furthermore, the revitalization project has attracted private investors who view social issues as secondary concerns. Emphasizing housing privatization and real estate investment lays the groundwork for gentrification, which can lead to resident displacement. Existing residents also lack the opportunity to present alternative land-use options to authorities, which translates into a diminishing ability to participate in the changes taking place in their community (Jabłoński-Weryński 2020, p. 74). A similar situation was observed in Gdańsk. The image change of Dolne Miasto in Gdańsk has led to growing investor interest in this part of the city (Gdańsk City Development Office 2023, pp. 13–48). Increased investment activity suggests that the subarea has become more attractive and has greater development potential; however, it also carries the risk of gentrification. Dolne Miasto in Gdańsk and Księży Młyn in Łódź are already regarded as prestigious areas, accompanied by increasing popularity. Nevertheless, both examples have been repeatedly cited as successful cases of urban revitalization. Since 2020, the number of businesses in Dolne Miasto has steadily increased (Gdańsk City Development Office 2023, p. 45). The revitalization project has won numerous awards in several competitions. Among others, it was nominated in the RegioStars 2022 competition for its high potential to bring about social change related to the lifestyle of residents, use of urban space, increased responsibility for the place of residence, and local identity (Gdańsk City Development Office 2023, p. 13).

Although the revitalization of Gdańsk’s Lower Town was carried out with high artistic and esthetic standards, it revealed shortcomings in terms of social policy. Although some projects included elements of social participation, they were insufficient. It was not possible to fully engage with the recipients and confront them with their problems and needs. Participatory activities were carried out too quickly and often in a fragmented manner, making it difficult to obtain specific guidelines and data. According to a report on revitalization in Gdańsk, there was a strong focus on esthetic functions and community building without considering the needs related to improving living conditions, work, and mental health. Population displacement, the report notes, was in turn associated with the permanent degradation of existing social ties, often based on mutual neighborly help, friendship, and kindness (Łódź Province Management Board 2024, pp. 128–29).

In summary, revitalizing public spaces through art should not be limited to merely masking problems but also addressing them. As Bätschmann points out, caution is necessary when overstating the transformative power of art. (Bätschmann 2023). A city is not a showroom but a multifaceted space that performs a variety of functions, including the most important one—social. Only a space that constitutes “the heart of urban activities, determinant of local identity and a key element of structural conjunctions, could be important for the local community and have a significant role in the whole regeneration process” (Rembeza 2012, p. 1285).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Design

This study focuses on artist-led interventions in Polish cities between 2007 and 2022, undertaken in two different models: grassroots activities and urban regeneration initiatives commissioned by the public sector.

The timeframe of the case studies primarily covers the period from Poland’s accession to the European Union 2004 to 2024, with particular emphasis on the years 2014–2022, which saw the highest intensity of regeneration activities. Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022) was a period of downtime, “suspension”, and withdrawal from public activities. It should be emphasized that many of the analyzed projects were long-term; therefore, it was necessary to adopt such a broad time frame.

The study is based on a qualitative methodology that combines a literature review, particularly urban regeneration programs 2014–2020 and municipal strategies, case study analysis, thematic interpretation, field observation, and private conversations with community members. Seventeen individuals participated in the conversations. It was a purposive sample, in which the criterion for selecting respondents was primarily their place of residence in the immediate vicinity of a particular art intervention. The interlocutors included six people from Nadodrze in Wrocław, six from Gdańsk, and five from Łódź. The conversations contained questions regarding the reception of the intervention space, expectations, and results. Emphasis was placed on opinions concerning activities undertaken by artists or institutions in the area of interest. Conversations were conducted individually in the field in the specified cities, adhering to ethical norms, and obtaining informed consent from the participants. Anonymity and voluntary participation were guaranteed.

A comparative analysis facilitated the identification of shared themes, diverse approaches, and best practices. Finally, to capture public reactions and opinions, several online discussions concerning the artwork were analyzed. The main objective of this study was to examine the mechanisms of artistic interventions in public spaces. Equally important is understanding their impact on community building and sense of security.

4.2. Case Study Selection

Case studies were selected based on the following four criteria: The initial criterion was spatial context. All selected projects were located in areas with problematic or degraded urban conditions. During the intervention, the districts were characterized by dilapidated infrastructure, neglected architecture, crime, and poverty. Geographical diversity was the second criterion for inclusion. Therefore, case studies ranged from large agglomerations, such as Warsaw, through post-industrial cities, such as Łódź, to historic but challenging districts, such as Nadodrze in Wrocław. The given criterion makes it possible to capture the local conditions. It also allowed for the analysis of the way artistic activities were adapted to the specific needs and problems of a given community.

The following criterion was the level of social engagement. The idea focused on emphasizing diverse models of participatory strategies, such as co-creation with residents (Szczecin), workshops (Gdańsk), and community consultations (Wrocław), or, conversely, initiatives lacking considerable community input, such as in Warszawa. Theoretical alignment was also crucial. Therefore, the selected projects had to fit into specific theoretical frameworks. Finally, the examples provided refer to different types of artistic interventions as well as different scale of interventions (from small-scale, neighborhood interventions to projects implemented at the district level).

The criteria listed above highlight the diversity of the artistic strategies employed and their impact on social and spatial issues. Each of these projects contributed to a visible esthetic improvement in the area or a change in social perception (integration, safety, and community). However, these are not model examples of revitalization through art. Despite their positive effects, they also pose threats that must be considered when designing revitalization processes.

The selection of several diverse case studies was intentional, as it allowed for the presentation of the heterogeneity of the Polish urban panorama and strategies of public art. Only by contrasting different spatial, institutional, and social contexts (e.g., Łódź vs. Gdańsk, artistic murals vs. participatory mosaics) can one reveal the spectrum of challenges and opportunities for artist-led regeneration in post-socialist cities.

4.3. Research Procedure and Data Analysis

The conversations were analyzed using a thematic method to detect recurring themes related to sense of security, integration, local identity, and perceptions of spatial alteration. The choice of cases allowed for a comparative analysis to assess the effectiveness of diverse modes of action: top-down (municipal and institutional initiatives), bottom-up (residents initiatives and NGOs), and hybrid (projects organized by artists, institutions, and local communities). This comparison permitted the conclusion of the prerequisites for the successful implementation of artistic interventions in public spaces.

4.4. Limitations and Further Research

Research on the spatial and social impacts of artistic interventions is subject to certain limitations. First, the ephemeral nature of many projects must be considered. Owing to their location in public spaces, they are often damaged by human factors and weather. Some, such as installations and workshops, were intentionally brief. Another challenge is the long-term evaluation of the projects. Revitalization programs are complex, and art is only one of the many elements of the entire process, making it difficult to assess their effects. In this context, it could be helpful to use a matrix to examine the impact of art on social cohesion, such as the tool developed by the public art Think Tank Ixia. Future research could incorporate quantitative methods or examine similar initiatives in other post-socialist cities.

5. Conclusions

A comparative analysis of the examples presented reveals several recurring tools and solutions that have contributed to redefining public spaces. However, it should be emphasized that the scope and nature of these changes depended primarily on the level of involvement of the local community and the forms of cooperation between artists and other entities in the community. Grassroots participatory projects had the greatest impact on building bonds and “taming” public spaces. Although visually more attractive, top-down initiatives do not always lead to lasting social changes. The scope of the analyzed interventions is also important. Grassroots projects have addressed the problem more accurately and solved it more effectively. In contrast, top-down projects focused much more on the image and then on the promotion of the project. The Bródno Sculpture Park, as a large-scale, interdisciplinary project, demonstrates different mechanisms of engagement and raises unique challenges regarding community acceptance.

When analyzing the examples presented in this study, it is evident that the type of artistic intervention is an important factor in determining the scope and nature of its impact on local communities. Grassroots activities carried out by residents and artists most often translate into strengthening social bonds and building a collective identity as they engage participants in the direct co-creation of space (Rutkowwska project). Participatory projects that integrate lower and higher levels of social organization promote not only integration but also an improved sense of security and well-being among users (Colorful Backyards). Municipal interventions, on the other hand, although often visually spectacular, tend to have a limited social impact, especially if they lack genuine resident participation (Księży Młyn).

The conducted analysis highlights several universal mechanisms. Regardless of city size or socio-economic status, public art interventions can support social capital, redefine perceptions of safety, and activate local communities. However, one condition must be met, namely participation and co-creation with residents. Obviously, certain outcomes remain closely tied to local conditions. The effectiveness of intervention depends on existing social bonds, institutional support and the specificity of urban challenges (e.g., depopulation, gentrification).

In summary, this analysis highlighted the dual nature of artistic interventions in public spaces. The complexity of revitalization programs makes it challenging to isolate the specific effects achieved solely through creative activities. They undoubtedly contributed to the aestheticization of space and impacted community formation. However, they also led to adverse changes, such as overtourism or artwashing.

Neighborhoods in which art begins to dominate and become a hallmark, such as in the case of Łódź or Gdańsk, become fashionable, desirable, and ultimately egalitarian. This process disrupts the current social structure. Therefore, existing residents may feel alienated or out of place. A lack of information, context, and art education can even result in resistance to artworks (e.g., the sculptures in Bródno Sculpture Park).

The analysis also indicated the need for a more accurate selection of artistic interventions tailored to residents’ cultural needs and competencies. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the specific characteristics of local communities and local users at every stage of the creative process. Official, top-funded revitalization initiatives, although they have adequate resources for comprehensive implementation of activities, including a participatory component, tend to stretch over time and are not always carried out through the arts. Artistic grassroots initiatives, on the other hand, are by definition closer to the people and the target group, which facilitates relationship building and translates into less spectacular but much more critical solutions for the community. As demonstrated by Rutkowska’s Jeż project, the most effective and lasting results were achieved through a comprehensive approach to the process, which included co-designing with the target group. Artistic interventions are typically short-lived. Even if the work is permanent, the actual process ends with its completion, whether through painting or placement on walls. There is no doubt that such activities contribute to the aestheticization of space. They also initiate specific changes, such as in the perception of space, the identity of a place, or even its familiarization. However, without targeted activities and project leaders, the initial enthusiasm and commitment of the community tend to fade gradually. Therefore, the optimal solution is a hybrid model of activities that combines elements of both bottom-up and institutional approaches. This is also the most relevant in the Polish context.

The study’s findings suggest the need to redefine the measures of success of art projects in public spaces. Instead of focusing on visual, tourist, or media effects, an approach based on the categories of “belonging,” “causality,” and “cultural continuity” should be promoted.

Each type of intervention should be tailored to local needs and supported by an in-depth diagnosis of residents’ expectations and problems. This approach provides opportunities to build urban identity and improve the well-being of the local communities.

Although this article focuses on Polish examples, an approach, such as social participation, co-production, and negotiation of public space through art, can be fruitfully employed in further studies across Central and Eastern Europe, provided that it is tailored to local socio-political realities and supported by primary data (interviews, participatory observation).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

I confirm that the present study did not involve human participants or animals. Therefore, in accordance with the Code of Ethics for Researchers of the Polish Academy of Sciences (Resolution No. 2/2020 of the General Assembly of the Polish Academy of Sciences, 25 June 2020), approval from an ethics committee was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Information on the program can be found at: https://www.kulturstiftung-des-bundes.de/en/programmes_projects/image_and_space/detail/shrinking_cities.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 5 August 2025). |

| 2 | Backyard—an open, publicly accessible space surrounded by buildings, e.g., blocks of flats, serving various social functions. A common type of urban interior in Europe. |

| 3 | More information concerning the Corners project may be found at https://cultureactioneurope.org/projects/tell-us-a-story/stories/corners/ (accessed on 30 June 2025). |

| 4 | The telephone conversation with the center’s curator was conducted by the author of the article on 16 June 2025. |

| 5 | Based on email correspondence with the artist on 25 June 2006. |

| 6 | See note 5 above. |

| 7 | Information on Honorata Martin social sculpture: https://park.artmuseum.pl/en/o-parku/honorata-martin-zadomowienie (accessed on 30 June 2025). |

| 8 | Stanisław Ruksza’s commentary can be found on the: https://sztukapubliczna.pl/pl/park-rzezby-na-brodnie-/czytaj/44 (accessed on 30 June 2025). |

References

- Bätschmann, Oskar. 2023. The Art Public: A Short History. Translated by Nick Somers. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, Claire. 2012. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cercleux, Andreea-Loreta. 2021. Street Art Participation in Increasing Investments in the City Center of Bucharest, a Paradox or Not? Sustainability 13: 13697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesiółka, Przemysław, and Angel Burov. 2021. Paths of the Urban Regeneration Process in Central and Eastern Europe after EU Enlargement—Poland and Bulgaria as Comparative Case Studies. Spatium 46: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesiółka, Przemysław, and Barbara Maćkiewicz. 2020. From Regeneration to Gentrification: Insights from a Polish City. People, Place and Policy Online 14: 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czirfusz, Márton. 2015. Obliterating Creative Capital? Urban Governance of Creative Industries in Post-Socialist Budapest. Europa XXI 26: 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dewey, John. 1934. Art as Experience. New York: Minton, Balch & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Dębek, Michał, and Paulina Olejniczak. 2015. Wizerunek wrocławskiego Nadodrza po działaniach rewitalizacyjnych 2009–2013. Social Space 1: 1–48. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Draganovic, Julia, Anna Szynwelska, and Adam Budak, eds. 2013. The Relevance of Art in Public Space. Gdańsk: Laznia Centre for Contemporary Art. Available online: https://rpo.pomorskie.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Problematyczna-niewygodna-niejasna.-Rola-sztuki-w-przestrzeni-publicznej.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Florida, Richard L. 2012. The Rise of the Creative Class: Revisited. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gablik, Suzi. 1991. The Reenchantment of Art. New York: The Reenchantment of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Gdańsk City Development Office. 2023. Municipal Revitalization Program for the City of Gdańsk for 2017–2030. Available online: https://www.brg.gda.pl/attachments/article/2047/GPR-Miasta-Gdaska-na-lata-2017-2030---PROJEKT.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Grzyś, Patrycja. 2024. Wpływ Nieformalnych Inicjatyw Obywatelskich na Kształtowanie Przestrzeni Miejskiej. Przykład Łodzi. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Łódź, Łódź, Poland. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Tim, and Iain Robertson. 2001. Public Art and Urban Regeneration: Advocacy, Claims and Critical Debates. Landscape Research 26: 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłoński-Weryński, Szymon. 2020. Mit wrocławskiego Nadodrza. Gentryfikacja jako negatywna konsekwencja procesu rewitalizacji. Our Europe. Ethnography—Ethnology—Anthropology of Culture 9: 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Jaskólski, Marek, and Mateusz Smolarski. 2020. Rewitalizacja i gentryfikacja jako procesy sprzężone na wrocławskim Nadodrzu. Studia Miejskie 22: 105–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kelling, George L., and James Q. Wilson. 1982. Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety. The Atlantic 249: 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kester, Grant H. 2014. On Collaborative Art Practices. Interview by Praktyka Teoretyczna. Available online: https://www.praktykateoretyczna.pl/artykuly/grant-h-kester-on-collaborative-art-practices/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).