Abstract

This article examines the material data preserved in king’s coffins used to bury and/or rebury five different kings, which represent the surviving material evidence we have of the art produced to manufacture divinized kingship during the New Kingdom: Seqenenre Taa, Kamose, Thutmose I/Panedjem I, Thutmose III, and Ramses II. All of them were removed from their original 17th and 18th Dynasty sepulchers, stripped of valuable materials, modified, and reused in later cache burials of the 20th, 21st, and 22nd Dynasties by 20th and 21st Dynasty High Priests of Amen, who used these recrafted coffins as a means of claiming their political and ideological legitimacy. Supported with detailed evidence of the five surviving king’s coffins as objects of social and political value and sometimes relying on the coffins recovered from Tutankhamun’s tomb for comparison, this article attempts to reconstruct some of the original material state of this art as a tool of power.

1. A King’s Coffin as an Object of Power

An Egyptian coffin divinizes the person inside, idealizing their features, covering them with protective and transformative text, and turning the deceased into Osiris or Re or both (Sousa 2014). The fact that New Kingdom coffins were constructed in the shape of the human body adds another dimension to this object’s power. An anthropoid coffin displays crafted mouth, eyes, ears, and nose; it has body contours and hands. Although some outer coffins are very large, the inner anthropoid coffin was constructed to be the same approximate size as the living human beings around it, equalizing the dead person and the ritualists and mourners around it.

Coffins for royalty manufactured additional power for the deceased inside and the ritualists working around it, creating social separators in terms of larger size, multiple pieces in a set of nesting coffins, additional valuable materials, and rare and restricted styles and iconography. The materiality of the royal Egyptian coffin communicates social power. Egyptian kings’ coffins were ideally completely made of, or covered with, precious metals, like gold or silver, ideally embossed and inlaid sheeting, rather than simple metal foils (Bertsch et al. 2017; Guerra et al. 2023). The eyes of king’s coffins were ideally inlaid with metal, stones, and colored glass. The surface of such coffins displays inlays of semi-precious stones and glass arranged in decorative and figurative patterns, like the stripes of a nemes-headdress or the feathers of a bird. All of this material, as well as the iconography into which they were shaped, were monopolized by and for the king, separating the king from the rest of society by means of fine art and funerary production.1

The royal funerary object was crafted to act as the receptacle for the corpse of a person believed to be the “good god”, which likewise received material interventions, including removing the wet inner organs, drying these and the body itself out for weeks, lubricating and anointing the organs and body with imported oils and anti-fungal/anti-bacterial resins, wrapping organs and body with yards of linen, some woven specifically as bandages and/or of the finest quality with a high thread count (Smith 1912; Ikram and Dodson 1998; Ikram 2010; Abdel-Maksoud and El-Amin 2011). A king’s flesh and bone were thus turned into an effigy of sorts (Cooney 2012). This wrapped body was then embellished with protective and enlivening amulets, rings and stalls placed on fingers and toes, pectorals and necklaces on the neck and chest, earrings on the ears, coverings of various sorts on the head, and finally a mask over the head and upper chest to protect that most vulnerable part of the mummified body (Reeves 2022). This funerary ensemble represents a crafted message of political and religious power, combining craftsmanship, precious materials and human tissue, resulting in a fetishized image of the king as a god, turning the mummified body inside of a nesting coffin set into something perceived to hold power from its own side (for this understanding of the fetishized object, see Boscagli 2014).

The royal coffin included repeated instantiations of itself in human form so that audience members interacting with the various parts of the ensemble might have had difficulty seeing where the human body stopped and the objects began. The royal coffin was crafted to look like the embellished mummy, after all. The visual repetition was purposeful. The nested parts of a coffin set were depicted with similar forms and motifs, all of them showing (or meant to show) the same bodily form and portrait of the king on the lid, all of them showing similar transformative decoration and iconography on the lid, case sides, and interior, each coffin able to act singly, if necessary, but more effectively as part of a larger ensemble to encase and transform the body of the monarch within multiple layers of protection. The coffin ensemble manufactured non-practical, aesthetically pleasing, technologically advanced fine art using the modified flesh and bone of a socially separated and hierarchically elevated person as the core material of that art (Cooney 2021).

To embellish and divinize the dead king in such a coffin set, a variety of Egyptian artisans were trained and maintained over generations so that they could apply their carefully gained specialized expertise to the task at hand, each specialist adding different elements to the ensemble. Such coffins were ordered years in advance, ideally as soon as the king ascended the throne (Brown 2024). These artisans were allotted large amounts of time, it seems, to create these bespoke and intricate royal coffins, as well as rare, imported, and valuable materials, including imported cedar wood, fine grained lime plasters, refined animal glues, linen sheeting to stabilize, precious stones like carnelian and lapis lazuli, manufactured red, yellow, and blue glass formed into shapes crafted to fit the coffin’s decorative scheme, and precious metals like silver and gold—monopolized by and for the ruling elite. The resources used in a king’s coffin thus represent the hoarded wealth and political reach of that ruler’s political regime. Minerals and metals were sourced from expeditions into the deserts and beyond, timber and resins from imported trees felled in faraway west Asia and central Africa, and glass created in palace factories. None of this sourcing or crafting was technologically necessary to sustain systems of food creation, shelter, or the other necessities of biological human life; such artistic practices were maintained and controlled for the conspicuous consumption of the high elite in funerary display (Voutsaki 1997).

In the 17th and early 18th Dynasties, New Kingdom kings were buried in so-called rishi coffins, sometimes crafted from an entire log of local sycomore fig wood, presumably a tree felled especially for the production of the king’s coffin (Miniaci 2011; Arbuckle MacLeod, forthcoming). The crafting of the king’s coffin can thus be understood as a sacrifice made by the living because an Egyptian community somewhere was expected to make a kind of payment in the form of a centuries’ old shade giving tree (Cooney 2024, p. 95). Because the sycomore fig was considered a mother goddess by the Egyptians (Giesecke 2023, p. 131), this wood was perceived to be the correct material to contain a divinized ruler in the early New Kingdom. These rishi coffins were decorated with iconography that transformed the king into a falcon—Horus incarnate—with a bird’s feathers incised and painted on the surface of lid and case (Miniaci 2011; Sousa 2018). Such kings’ coffins may have been displayed in both closed and open social settings, the former in the company of the king’s family and highest elite, and the latter during a large, public funerary display during which audience members could only see the coffin ensemble from a distance. Nicholas Brown, however, uses compelling evidence from the burial preparations for Merenptah and Tutankhamun to suggest that the king’s coffin set was not formally shown in procession when the king was buried because it had already been installed in the tomb in secret. Brown argues it was the embellished and mostly veiled, we must presume, mummy of the king that was put on display during the funeral procession, indicating that the royal coffins were only shown to a very select audience in an enclosed space (Brown 2024). The installation of the dead king within a nest of valuable, crafted art before an exclusive audience signified the transfer of power from the dead king to those individuals present, and to the heir in particular (see also Lippert 2013).

The king’s coffin was a place to collect a mass of text and iconography, much of it maintaining archaic markers of kingship not readily understood by the rest of society, even by some of elite society. The coffin’s decoration was thus a place to display restricted knowledge known only to an initiated few, some of it tucked away inside the coffin, some of it later covered over with heated resins that were poured over the mummy and coffins inside and out (ex: Carter 1927, pp. 78–82). In short, the king’s coffin ensemble was a crafted political statement of social specialness for the person buried inside, of political utility for the next king who had just ascended the throne, for his associates and lieutenants, and even for those specialists responsible for its crafting.

And now we come to the dataset at hand, namely five kings’ coffins; four are preserved from Deir el Bahari 320 (Theban Tomb 320), the so-called “Royal Cache”, and one from a reburial space at Dra Abu el-Naga (see Appendix A—Royal Caches Chart). These king’s coffins were used to bury and/or rebury five different kings:

- Surviving Kings’ Coffins

- Seqenenre Taa—17th Dynasty—modified 18th Dynasty rishi style

- Kamose—17th Dynasty—17th Dynasty rishi style

- Thutmose I/Panedjem I—18th Dynasty coffin redecorated in 21st Dynasty style

- Thutmose III—mid 18th Dynasty style

- Ramses II—late 18th Dynasty style

All of these surviving king’s coffins had been removed from their original 17th and 18th Dynasty sepulchers, stripped of valuable materials, modified, and reused in later cache burials of the 20th, 21st, and 22nd Dynasties (Cooney 2024). It is not clear if these five coffins were actually made for the particular kings found in them. Indeed, the coffins in which Seqenenre Taa and Ramses II were reburied were probably not made for these specific kings as the coffin styles do not match the dates of rule, about which more will be said below. Each of these five king’s coffins show unambiguous evidence for the removal of valuables, redecoration of the surfaces, ritual manipulation, and reuse by 20th and 21st Dynasty Theban political agents who ostensibly needed the valuable material resources these coffins could provide. These five surviving kings’ coffins prove that Theban kings’ coffin ensembles—except for any intact or semi-intact tombs including Tutankhamun’s—were stripped of most of their precious materials and downsized from a coffin set to a single coffin that accommodated the stripped and rewrapped corpse. These actions occurred over a stretch of time from the 20th to 22nd Dynasties when Theban agents systematically cleared the royal and elite necropolises of Thebes to fund their scattered and decentralized power regimes at the end of the Bronze Age and into the early Iron Age (Reeves 1990).

The bodies of dozens of kings from the New Kingdom, their family members, and the Theban rulers of the 21st and early 22nd Dynasties have been recovered from multiple caches, including Theban Tomb 320 in Deir el Bahari, the tomb of Amenhotep II known as King’s Valley 35, and other unknown Dra Abu el-Naga reburial spaces, most rediscovered and moved into museum collections in the 19th century (Cooney 2024). The vast majority of the kings’ bodies were removed from their nesting royal coffins and reburied in single elite body containers. Some of these elite body containers were modified to suit the kings by adding cobras, crooks, and flails, either in three-dimensional wooden form or painted in two-dimensions. Such modifications were arguably meant to showcase the pious caretaking of 20th and 21st Dynasty Theban agents like high priests Herihor and Panedjem I (Cooney 2024). The elite coffin used to rebury Amenhotep I, for example, was stripped of any precious materials before its reuse for the king, but craftsmen made sure to affix a wooden uraeus and repaint the coffin with imagery, including a protective vulture goddess on the chest, the king’s names, titles, and some simple transformative texts (Daressy 1909, pp. 7–8; Cooney 2024, pp. 143–48).

Except for the coffins of Tutankhamun discovered by Howard Carter in 1922 in King’s Valley 62 and a few examples of 17th Dynasty royal coffins from Dra Abu el-Naga, these five kings’ coffins represent the surviving material evidence we have of the art produced to manufacture divinized kingship during the New Kingdom.2 This article attempts to use the material data preserved to reconstruct some of the original material state of this art as a tool of power, sometimes relying on the coffins recovered from Tutankhamun’s tomb for comparison. We will start with the detailed evidence of the five surviving king’s coffins as objects of social and political value.

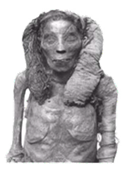

2. The Coffin Used for Seqenere Taa (CG 61001)

The coffin used to rebury Seqenenre Taa was found in Theban Tomb 320 (Cooney 2024, pp. 119–26). The outer coffin’s lid is late rishi in style and was originally made for a king as it has a nemes-headdress and cobra uraeus (Figure 1). The date of the piece is in question, and the coffin may date to later than Seqenenre Taa himself, potentially to the early or mid-18th Dynasty. At some point, the coffin was (re)fashioned for Seqenenre Taa as his name was inscribed into a plaster surface, suggesting that gold sheeting and other valuables were removed from the royal coffin first, after which time it was replastered, redecorated, and regilded.

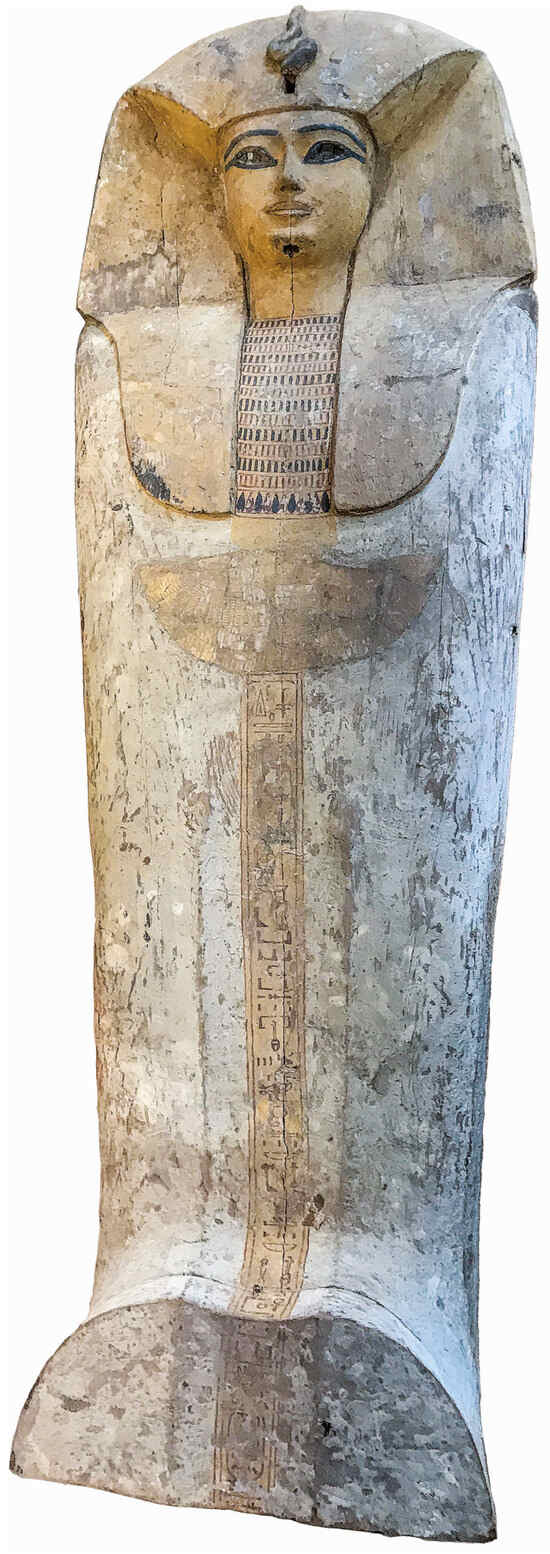

Figure 1.

The outer coffin lid of Seqenenre Taa (CG 61001). Photo by UCLA Coffins Project, courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Cairo. From Recycling for Death by Cooney (2024), used with permission of the publisher, AUC Press.

The coffin preserves chisel marks in the surface of the wood over which the current plaster layer was applied, indicating the removal of precious materials such as gilding or gold sheeting before new layers of plaster and gilding were applied. There were thus multiple modifications of this coffin, including an initial removal of gold, a restoration and replastering, and then new incisions in that plaster to mark the coffin for Seqenenre, accompanied by regilding, after which we see another, later removal of those precious materials added in the 20th or 21st Dynasties. After gilding was selectively removed, the surface of the coffin was covered with a light wash of yellow and/or white paint with details picked out in blue, black, and red. Multiple mortis and tenon joins, many of which were sawn through to open the coffin, indicate that the coffin was opened and closed multiple times. The lid of the coffin is quite shallow, which may indicate the lid was cut down for some reason, but this is unclear.

The tail of the cobra uraeus motif on the forehead retains its gilding, though the rearing cobra itself was removed, most-probably to recommodify the gold. The nemes pattern was executed with blue paint and gilding at some point, some of which is still visible, though it has since been painted over with a light-yellow wash. Once the head’s gilding was removed, the whole area was covered with a white–yellow paint.

The face was covered with a yellow–white wash, with details of the eyebrows and eye lines drawn in blue paint. The face once had inlaid eyes, which have since been removed, probably because they were made of precious materials. Artisans used red paint to delineate the lips and upper seam between the forehead and nemes-headdress. There are two dowel holes on either side of the face that must have held ears molded in gold sheeting, now missing.

Running down the center of the lid is a painted column of text on the yellow wash, written in red ink, which replaced an original incised and presumably gilded column of text. The preserved gilded cartouche of the king reads “Seqenenre, Venerated of Osiris, Lord of Djedu”. This painted column continues down the front of the case to the underside of the feet, where another preserved area of gilded incised plaster is preserved. This column of text continues onto the case of the coffin, though, here on the case, only incised plaster is visible, without any evidence of gilding.

The case and lid show different plaster and surface treatments. The gilding of the Seqenenre lid was removed and with it, most of the plaster. The case was not gilded in this way as there are no traces of gold remaining. Some gold leaf is left on the Horus heads at each shoulder of the lid, on the winged cobra and vulture on the chest, within the cartouche name, on the text on the bottom of the feet, and on the cobra tail on the forehead.

The most striking element on the coffin lid’s interior is the thick layer of a black, varnish-like substance, applied after the coffin was stripped of its gilded exterior and reworked, as is apparent from black spots that overlay the whitewash and yellow paint on the exterior. The coffin lid shows an uneven number of exposed tenons, some of which were sawn through, indicating the coffin was closed and opened multiple times. Some of these sawn-through tenons were plastered over.

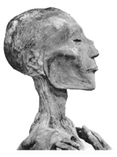

3. The Coffin Used for Kamose (TR. 14.12.27.12)

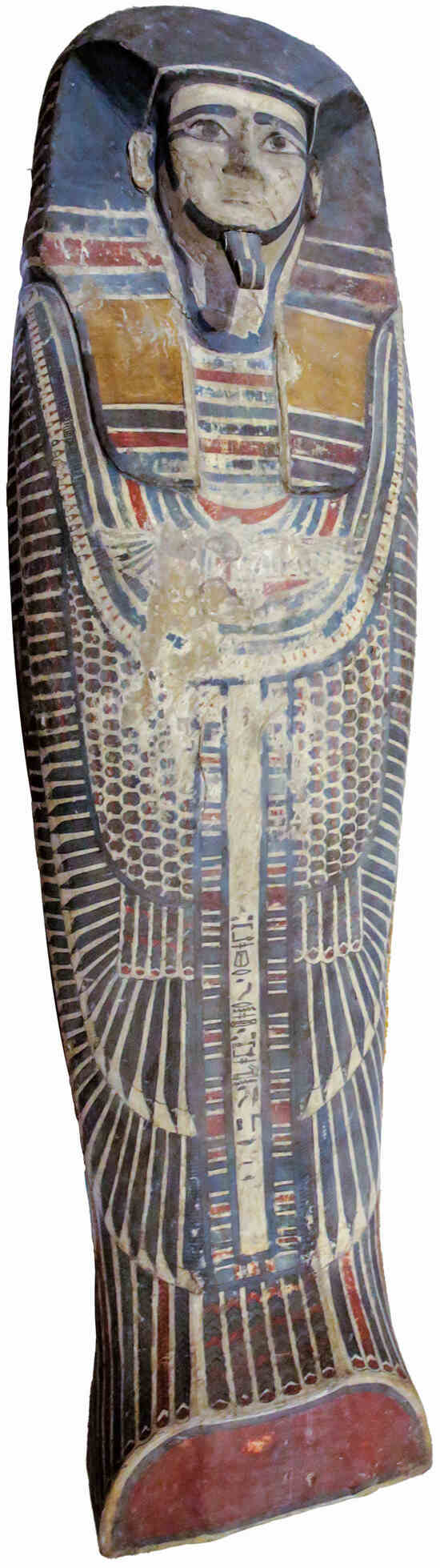

The mummy and coffin of Kamose were discovered at Dra’ Abu el-Naga near to the spot where Ahhotep was found (Winlock 1924; Miniaci 2011; Cooney 2024, pp. 285–89). This coffin was crafted with a nemes-headdress for a king (Figure 2). The lid of the coffin was carved from the same, single log. Egyptian blue paint was applied roughly over the ears, suggestive of repainting after recommodification. The coffin’s beard seems to be original to the piece. The chin strap is painted in Egyptian blue, and the neckline is also outlined in this color. On the front of the lid is a vulture pectoral, while the central column of hieroglyphs running down the center has sections at the top and bottom that seem to have been purposefully scrubbed away, suggesting modifications. It is even possible that this royal coffin shows a name reuse, implying another king’s coffin was reused for the reburial of Kamose. One of the mortis and tenon joins on the left side was forcibly opened, indicating this burial was recommodified before reburial. The exterior of the case has a very thick layer of plaster overlaying the wood, which was then painted over, suggestive of recommodification after the stripping of valuables.

Figure 2.

The coffin of Kamose (TR.14.12.27.12). Photo by UCLA Coffins Project, courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Cairo. From Recycling for Death by Cooney (2024), used with permission of the publisher, AUC Press.

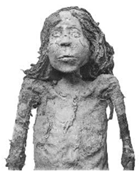

4. The Coffin of Thutmose I Reused for Panedjem I (CG 61025)

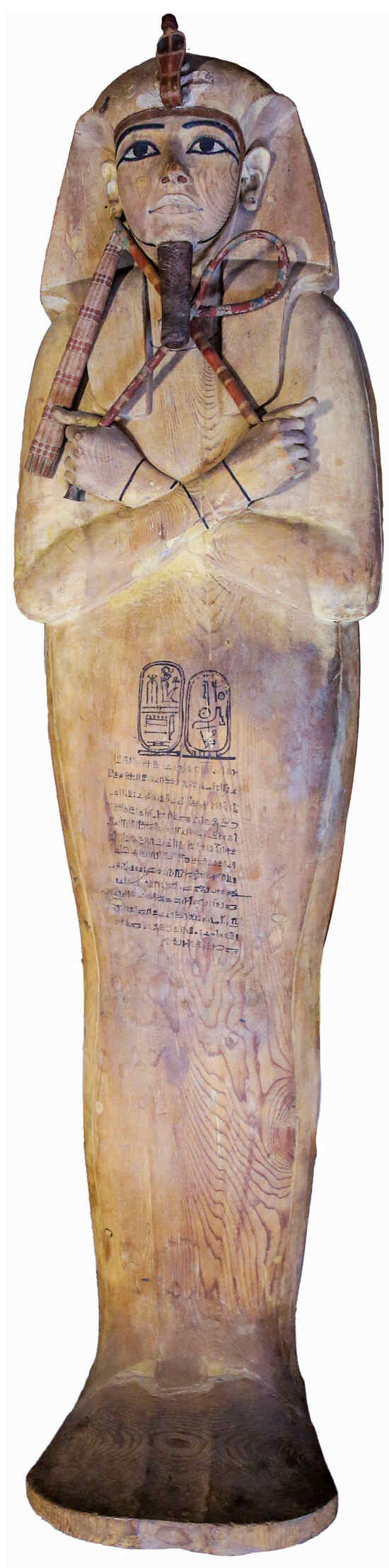

This coffin originally belonged to King Thutmose I and was reused for Panedjem I, eventually deposited in TT 320 (Figure 3; Cooney 2024, pp. 299–305). The original inlaid wig, vertical lid inscription, and inlaid udjat-eyes on the case sides for Thutmose I are visible under the current plaster layer. Underlaying this later plaster (re)decoration, there are some chisel marks on the Thutmoside surface that are still visible, suggesting that the coffin was removed of valuables before it was reused. Since the Panedjem I surface gilding was also chiseled away at a later date, there seem to be two instances of gold removal from this piece.

Figure 3.

The coffin of Thutmose I reused for Panedjem I (CG 61025). Photo by UCLA Coffins Project, courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Cairo. After (Daressy 1909, Plate XXVIII).

The reusers added a new plaster layer to the face and coffin surface. New gilded plasterwork with a complicated inlay of colored glass was added to the coffin lid for Panedjem I, including the wig band, collar, pectoral, and lower body decoration.

The hands of the outer coffin lid were built of multiple pieces of wood, an unusual feature, leading one to suspect that the removal of valuable commodities from Thutmose I’s coffin had damaged the surface, demanding that the reusers repair the fisted hands with new pieces of wood. There is chiseling visible on these newly formed hands, too, indicative of a second instance of gold removal. The old Thutmoside inlay on the wrists is partially visible underneath the plaster, indicating that the original coffin had crossed forearms modeled onto its surface.

The removal of gilding from Panedjem’s decoration was selective, leaving the gilded and inlaid wig band, wesekh-collar, and bracelets intact. The gilded eyes were left partially intact. The gilded pectoral and vertical text were also allowed to remain after recommodification. The rest of the lid’s surface shows evidence of rough removal of surface gold. The underside of the lid shows a red plastered layer underneath the black varnish, suggesting modification. The lid is very shallow in depth, suggesting it was cut down.

New mortises were added with barely enough width in the case side to sink them suggesting that the coffin sides have been thinned. The interior of the case has been varnished black. This black layer cannot be the original decorative layer because the removal of interior wood is clear from chisel marks and uneven case side widths. After the addition of the black varnish, the case interior was decorated with text and iconography in line drawing. The gilding on the case sides was selectively removed, taking everything except the two panels of the striped headdress.

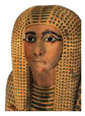

5. The Coffin Used for Thutmose III (CG 61014)

The coffin of Thutmose III (Cooney 2024, pp. 199–207; Brown 2020) was made for a king and reused for a king (Figure 4). On the exterior surface, the coffin was completely stripped of gold, quite roughly in places. The royal coffin was likely originally covered in gold sheeting. Once stripped of this original surface, the high-quality, fine-grained wood was restored with another layer of plaster and a thinner layer of gold leaf. The interior decoration for Thutmose III was applied only after the coffin was opened and removed of its valuables twice, suggesting the interior was originally covered with gold sheeting of some kind. After this was removed, another set of mortises and tenons was sunk, and the coffin was covered in gold leaf. At some point after this, probably in the early 22nd Dynasty, the last gilded layer was removed from the coffin exterior, this time quite roughly, destroying the face, head covering, chest, and body. There are still traces of gilding preserved on the neck, shoulder, and on the case, though it was a very thin layer.

Figure 4.

The coffin used for Thutmose III (CG 61014). Photo by UCLA Coffins Project, courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Cairo. From Recycling for Death by Cooney (2024), used with permission of the publisher, AUC Press.

The coffin has very thin walls, with a lack of regularity in thickness, suggesting multiple iterations of chiseling the wood—to create more internal space or to remove valuable commodities, or both. The coffin shows an excess of mortis and tenon joins—three series of them—indicating that the coffin was reopened and closed at least twice after its original 18th Dynasty closing.

The interior decoration of lid and case shows a white plaster layer with careful incision of regular lines and a painted vertical column of inscription on the lid and case for Thutmose III. This interior decoration cannot date to the 18th Dynasty but dates rather to the 20th or 21st Dynasty because later mortis and tenon joins were added after the original interior was cut back, leaving old mortis and tenon joins at the edge of the coffin sides or cut away completely. The plastered interior shows even, incised lines on a plastered surface, crossed at ninety degrees at certain points to create a grid pattern, curving inwards at the feet. This pattern likely represents a mat motif, representative of the archaic matting meant to contain the deceased king (Brown 2020). While such decoration and iconography seem consistent with 18th Dynasty coffin interior decoration, it is more likely that 21st Dynasty craftsmen purposefully chose archaizing elements. The whole coffin interior was covered with a shiny, black varnish, covering this netting decoration and inscription. The uneven and unfinished flat seams show remnants of gilding, suggesting that this area was repeatedly stripped and regilded with thin gold foil.

Examination of the inlaid left eye indicates it was made of blue glass; the right eye is only an empty socket. The eyebrows seem to have been made of inlaid glass, but the inlay channel is quite shallow on the forehead compared to the temple, suggesting the removal of surface wood. The wooden ears were removed, but gilding around both ears remains.

The uraeus hole/attachment is small and off center, towards the proper right-hand side. The off-center placement suggests that there were originally two attachments for a dual cobra-vulture emblem on the king’s forehead. Furthermore, the impression of a cobra’s coiled body in the plaster on the left-hand side of the king’s forehead corroborates this observation.

On either side of the collar, the attachments for a crook and flail are visible. The plaster relief of the collar is preserved in places, along with the feather patterning on the lid’s right shoulder, with some gilding still attached to it.

On the lid’s left hand, one can see the outline of knuckles cut into the coffin’s wooden core to which a block of wood was added on top, now missing. It is unclear what the previous decoration layers looked like, but multiple layers of plaster suggest multiple decorative layers. The bottom of the lid’s and case’s feet shows plastered gilding, too, most of which has been stripped from the piece, though there are remnants of plaster and gilding work on the lid’s foot-end. The foot-end of the lid and case shows a grid pattern incised into the plastered linen, which was then covered with gold leaf. The grid was cut evenly and with the help of a regular tool, incised into the plaster surface.

On the exterior of the case underside, 18th Dynasty body contours are visible. The underside of the case also shows the tail of the nemes-headdress, which has remnants of gilding all around it, indicating that the entire coffin exterior was once gilded, ostensibly even in its final 21st Dynasty iteration.

The coffin and lid sides are very thin in section, compared to the much thicker sides in the coffin set of Tutankhamun, for example, and show flat seams, unlike Tutankhamun’s stepped seams (Carter 1927, Plates XXII and XXV). The seams are roughly chiseled and uneven, probably because they have been removed of their gilding. The removal of gold from the coffin’s seams cut through white plaster decoration of the lid and case interiors. Some small sections of seam gilding remain. In some areas, it seems that a red paint/wash was applied after the gold removal; in other areas it seems a red paint/wash was added before. Both instances are probably verifiable.

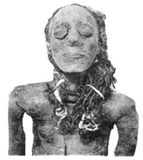

6. The Coffin Used for Ramses II (CG 61020)

This coffin was originally made for a king as it was crafted with a nemes-headdress (Figure 5; Cooney 2024, pp. 232–38). However, this royal coffin was not made for Ramses II but rather a late-18th Dynasty monarch according to the stylistic features of the face (Reeves 2017).

Figure 5.

The coffin used for Ramses II (CG 61020). Photo by UCLA Coffins Project, courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Cairo. From Recycling for Death by Cooney (2024), used with permission of the publisher, AUC Press.

There are absolutely no traces of gilding on this coffin. It is possible that this coffin was covered with gold sheeting. Because there is no relief work cut into surface plaster or wood to which the gold would have adhered and formed, we might assume that significant depth was removed from the coffin surface to take the gold sheeting off. Even the dowels on the coffin face indicate the coffin surface here was cut back for some reason. If the eyes had been originally inlaid, they have since been filled with plaster and repainted.

Visual comparison to Tutankhamun’s second coffin shows that this piece is very similar in craftsmanship and style. However, Tutankhamun’s wooden coffins have stepped seams on the cases and lids (Reeves 2022), while this coffin reused for Ramses II has flat seams of uneven width, which after modification were painted red. It is probable that the interior of this coffin was also cut back, removing the inner step and leaving only thin coffin walls. Assuming the coffin was cut back, it was expertly done as the interior modeling remains.

There is no trace of black varnish on the piece. The crook and flail and probable double vulture and cobra uraeus were replaced with cheaper, polychrome versions made of wood. The bare wood is covered with a yellow wash over the entire surface of the piece inside and out. This yellow paint may include orpiment, but testing is required to prove this supposition.

The face of the coffin is Amarna or post-Amarna in style, with the details painted on, including eyebrows, eyes, and beard strap in Egyptian blue. It is clear that the uraeus has been modified. Not only is it off center in its current state, but there are remains of another dowel hole filled and covered with plaster on the coffin’s right for a double uraeus. The current uraeus has been changed to a single cobra made of wood, while a tail of plaster was maintained and is currently positioned approximately one centimeter away from the newly added wooden uraeus.

The wooden ears were attached with dowels and plaster, and, perhaps after gold sheeting was removed, details were repainted in red and black ink, including the ear piercing, an Amarna or post-Amarna feature. Along the left side of the nemes-headdress, one can see a mortis join in close proximity to the edge of the coffin, suggesting that the coffin exterior was cut back considerably as mortis and tenon joins are usually located in the middle of a coffin seam’s width. Indeed, throughout the body of the coffin, there are a number of dowels that are visible, close to the surface, indicating that the coffin was planed down from its original wooden core during or after gold removal.

Within the interior of the case, there is obvious wood modification at each of the two elbows, where the wood was cut back to create more room on the inside, ostensibly for another body container, indicating that, even post recommodification, the earliest reburials of Egyptian kings included multiple nesting pieces and only later were they reduced to single coffin burials.

7. Comparison with the Tutankhamun Coffin Set

It is useful to compare these coffins made for kings with the 18th Dynasty coffins of Tutankhamun, our only surviving New Kingdom coffin set. The 21st and 22nd Dynasty coffins from Tanis would also have been instructive, but these were unfortunately not found intact (Montet 1947, 1951, 1960), leaving only the metal inner pieces for museum display and study. First, it is important to note that only wooden kings’ coffins survive from the Theban royal caches, not any made of precious metals. Thus, the best comparisons from Tutankhamun’s tomb are the outer and second coffin in the three coffin nesting set, both of which were made of embellished wood. Second, it is clear that all precious materials had been removed from the kings’ coffins interred in the royal caches. It is Nicholas Reeves who notes “How different from those battered hulks recovered from the caches at Deir el-Bahri (DB 320) and the tomb of Amenhotep II (KV 35)!” (Reeves 2022, p. 209).

Third, though no exact measurements could be made for this study, the gilding applied to the outer and second Tutankhamun coffin is certainly thicker and more extensive than the gold re-applied to the coffins of Thutmose III and Sequenenre-Taa by Theban agents in the 21st Dynasty. The face of Tutankhamun’s outer and second coffins seems to approach a kind of sheet-gold (Reeves 2022, p. 210), though more extensive study is needed to prove this point. The point is: the gold originally applied was more generous than the gold applied later by Theban agents in the 20th and 21st Dynasties. Indeed, the fact that the coffin used to rebury Thutmose III was re-gilded by Theban agents suggests that it may have originally been covered with gold-sheeting inside and out, rather than just gold leaf. Finally, it must be noted that none of the surviving kings’ coffins show any traces of a nesting set of multiple pieces; only single coffins survive. Tutankhamun’s coffin set suggests that the most valuable materials were retained for the innermost coffin pieces—his inner coffin and mummy mask were made of inlaid solid gold—while his second and outer coffins were larger but made of wood covered with gold.

Tutankhamun’s entire coffin set including the lion bed, Reeves tells us, amounted to a “ton-and-a-quarter weight”, or an astounding 1250 kilos, or 2500 pounds (Reeves 2022, p. 209). Many elements contributed to that weight, including the solid gold of the inner coffin and mummy mask, the imported wood making up the outer coffins, the glass used as inlay, and the extensive amounts of resin poured into the ensemble. Just thinking in terms of base commodities, the value of this material is measurable and profoundly expensive. We can and should use the surviving example of Tutankhamun’s semi-intact tomb to imagine that most 18th Dynasty kings were likewise buried with such excess—even though it cannot be proven directly.

There is an interesting modification visible on the feet of Tutankhamun’s outer coffin, namely the cutting of the top of the coffin feet, ostensibly to enable the entire set to fit into the sarcophagus. This cut area was then covered with thick black resin such that it drips down the top of the feet (Carter 1927, pp. 89–90). We can understand this black substance as a kind of “healing agent”, covering over any hacking or chiseling into the decorated coffin surface, particularly this seemingly last-minute modification. Theban agents of the 20th and 21st Dynasties also relied on this black varnish substance, using it on the interior and seams of coffins after making their own modifications, and it is fitting to understand the application of the substance as a kind of “healing” action after valuables were taken and coffins were refashioned.

Both of Tutankhamun’s wooden outer and second coffins were made of imported wood, the outer piece identified as cypress, a west Asian conifer (Reeves 2022, p. 210), while his second coffin was made of an unidentified but almost certainly imported wood (Reeves 2022, p. 213). These wood choices find interesting parallels in the imported west Asian cedar wood used to craft the coffins for Thutmose III and Ramses II, for example.

Both of Tutankhamun’s wooden coffins included a double cobra and vulture uraeus pair affixed to the forehead of the king, identified by Edna Russmann as Nephthys (the cobra) and Isis (the vulture) (Russmann 1997, p. 271), the same goddesses depicted on the head and foot ends of New Kingdom coffins, respectively (Lüscher 1998). These embellished images of protected kingship are missing from all the surviving royal coffins from the Theban caches, having been stripped and replaced with cheaper, single uraeus versions in the 20th and 21st Dynasties. Tutankhamun’s coffin set is invaluable, as it reveals the original 18th Dynasty intent. Indeed, each of Tutankhamun’s vulture and cobra uraei was given its own tiny wreath of flowers and leaves as part of the burial ritual, indicating the importance of this element of the king’s coffin (Carter 1927, Plates XXII and LXVII).

Tutankhamun’s coffin set includes the divine beard attached to chin and crook and flail in the hands of each piece. These have been removed from the surviving kings’ coffins from Theban royal caches, unsurprising given the precious materials—copper, gold, silver, glass—used to construct these objects. The coffin reused for Ramses II’s shows these elements restored, but with cheaper painted wood and no other embellishment. Kamose’s beard was also restored with a wooden version. Pinholes in the surface of the coffin lid suggest Thutmose III’s crook and flail were restored with cheaper wooden examples in the 20th and/or 21st Dynasties, but they are no longer there, suggesting that they were restored with gilded wood.

Tutankhamun’s outermost coffin has plaster modeling providing a surface relief that was then gilded (Reeves 2022, p. 211). Similar plaster relief is preserved on the coffin of Thutmose I under the decoration for Panedjem I’s reuse, and such plaster relief is also visible on the coffin used for Seqenenre Taa. It is not clear if the surviving plaster relief visible on the coffin for Thutmose III is original to the 18th Dynasty or a later 20th/21st Dynasty instantiation, and more stratigraphic work needs to be conducted to determine its approximate date. Such gilded plaster relief was a common feature of kings’ coffins.

Tutankhamun’s second coffin exhibits extensive inlay set into a plastered wooden matrix of some depth, probably explaining why the coffin reused for Ramses II is so much thinner in its case and lid sides compared to Tutankhamun’s coffins; with the removal of the inlay pattern likely came multiple centimeters of wood and plaster, too. Indeed, Theban agents would have removed surface thickness from each of the surviving kings’ coffins from the Theban royal caches, as can be seen by an overall comparison of the stepped seams of Tutankhamun’s outer and second coffins with the simple, flat, narrow seams of the coffins of Seqenenre Taa, Kamose, Thutmose I, Thutmose III, and Ramses II.

As these coffins were stripped of gold and inlay, their mortis and tenon construction was also significantly modified. Any tenons of precious materials—Tutankhamun had tenons made with gold and silver (ex: Carter 1927, p. 82)—were removed for basic wooden tenons. New mortises were sunk into the repositioned middle of the coffin case and lid seams, most visible on the coffins for Seqenenre Taa and Thutmose III. The locking mechanisms of Tutankhamun’s outer and second coffins involved tenons and securing pins of precious materials (Reeves 2022, p. 213), but there is little trace of such locked closures on the surviving king’s coffins from the royal caches as the wood in which they were placed was removed and/or modified (though there are remnants of the locking mechanisms on the coffin used for Thutmose III (Cooney 2024, p. 203, fig. 6.15.9) as well as Seqenenre Taa (Cooney 2024, p. 123, fig. 6.1.11). Any place on the kings’ coffins where there was an application of valuable materials—like mortis and tenon joins of gold and silver—would have drawn particular attention and been stripped in the 20th and 21st Dynasties. Indeed, we can read accounts of Howard Carter’s tribulations extracting the coffins not only from a matrix of black resin, but also the issues of undoing the securing pins in the mortis and tenon joins (Reeves 2022, pp. 218–19). Carter’s problems and subsequent solutions allow us to recreate some of the methodology of 20th and 21st Dynasty Theban agents who wanted to reuse the wooden coffins once stripped of valuables. It was important for Carter to remove the coffins intact and unspoiled for museum display, just as it must have been vital for Theban agents to remove functional wooden body containers for the reburial of important personages.

Both Tutankhamun’s outer and second coffin were worked with glass inlays to create eyebrows and cosmetic lines around the eyes. We see similar treatments on the surviving kings’ coffins from the royal caches, particularly the coffin for Thutmose III. The coffin of Thutmose I preserves original eye inlay channels underneath the new decorative surface for Panedjem I. Only shallow channels are left for the brows on the coffin of Ramses II, suggesting that the inlaid coffin surface was cut back when the valuable gold and inlay matrix was removed. Shallow inlay channels remain on the coffins for Seqenenre Taa and Kamose, suggesting that the surface was also cut back when the inlay was removed.

There is another surviving element from Tutankhamun’s coffins that is useful to compare to the royal reburials performed in the 20th and 21st Dynasties, but it is not a part of the material construction of the coffin, but rather an embellishment placed on to the mummy or coffin, namely Tutankhamun’s flower and leaf wreaths made of blue lotus waterlily, white lotus waterlily, cornflower, corn poppy, mandrake, chamomile, olive leaf, persea leaf, pomegranate leaf, wild celery, willow, and nightshade (Reeves 2022, p. 211). In the same way that 18th Dynasty burial agents ritually adorned the coffins of the king with these botanicals, 20th and 21st Dynasty Theban agents likewise used leaf and flower garlands after they had stripped and rewrapped the royal mummies. King Ahmose’s mummy was found rewrapped with a garland of delphinium flowers, also called larkspur (Smith 1912, p. 15), while Amenhotep I’s mummy included a garland with flowers of sesbania, delphinium, safflower, and acacia (Smith 1912, p. 18). If mummies were so decorated (Wiese and Jacquat 2014; Dittmar 1986), we might assume that 20th and 21st Dynasty Theban agents saw the attachment of wreaths and garlands as another means of restoring the royal ancestors after recommodification events.

8. Restoring the Element of Sun/Gold

These coffins prove that later reusers were keen to restore the power of what they had taken. It seems to have been most essential to restore the element of gold—the skin of the gods—to these kings’ coffins, even after masses of it were stripped from their surfaces (Aufrère 1991). The gold on the coffin in which Thutmose III was reburied was completely restored inside and out with gold leaf at various points in its use time. The thinness of the interior case and lid side walls suggests the removal of gold from the interior, after which a plastered and painted decorative layer was laid down. The exterior retained its restored thin gold leaf surface until its final moment of caching. Thutmose III’s was the only surviving kings’ coffin to maintain the element of gold in some form until the final caching moment, giving us some idea that this coffin and its inhabitant were used and displayed by Theban priestly agents in some fashion until its caching in TT320. In every other case, the element of gold was restored with a yellowish paint, some of it perhaps including orpiment, pending chemical testing. Seqenenre’s lid, including the nemes-headdress, face, vulture goddess, and vertical text bands were painted yellow, mimicking gold. Indeed, one of the text bands on the coffin foot-end has remnants of gold leaf, indicating Theban agents were aware that this substance elevated the ritual and/or social power of the king inside, and they were thus selective about where to place it and from where they should remove it. The entire surface of Ramses II’s coffin was covered with a yellow wash of paint over the bare wood, both inside and out. Only the coffin used for Kamose lacks yellow paint for the king’s face and central text band; however, the entire case exterior was covered with a yellow paint, the same type of yellow treatment added to the coffin used for Seqenenre Taa. After gold was removed from the coffin of Thutmose I, it was completely redecorated for Panedjem I, at which point gold leaf was added back to the coffin on the face, hands, and other elements—not for the 18th Dynasty ancestor king but for the 21st Dynasty High Priest of Amen.

We see the addition of yellow paint to the surfaces of non-elite coffins refashioned for kings too, including the coffins redecorated for Ahmose (Cooney 2024, pp. 127–32), whose entire face, lid, and even coffin seams were painted yellow, or Amenhotep I (Cooney 2024, pp. 143–48) who bears a yellow painted face, or Thutmose II (Cooney 2024, pp. 193–98) who has a very light yellow wash on the text bands and face, or Ramses I (Cooney 2024, pp. 223–26) whose face and hands are painted yellow in the manner of a 21st Dynasty yellow coffin, or Saptah (Cooney 2024, pp. 263–66) whose coffin surface is entirely yellow. Saptah’s yellow surface paint almost certainly contains orpiment, as the sparkling nature of this pigment is visible to the eye. The coffin reused for Seti I (Cooney 2024, pp. 227–31) indicates the head band and uraeus were both painted a light yellow, and the surface also betrays a few specks of gold leaf, indicating an attempt to do a thin regilding even after ostensibly stripping thicker layers of gold. The coffin in which Thutmose IV (Cooney 2024, pp. 254–58) was reburied bears the red face of an elite man, but the text column added to rebury the king is painted with a light-yellow wash, mimicking gold. A yellow surface was so required for the coffin in which Seti II (Cooney 2024, pp. 259–62) was reburied that the entire surface of a 21st Dynasty polychrome yellow was covered over with a resinous yellow layer; it was this surface that was inscribed with Seti II’s name. A similar treatment, namely covering over 21st Dynasty polychromy with a yellow–white layer, is also seen on the coffin reused for Ramses IV (Cooney 2024, pp. 276–80). The coffin in which Setnakht (Cooney 2024, pp. 267–72) was reburied had a gilded surface, ostensibly removed once it was cached in KV 35. The case interior decoration of the sky goddess and text with the name of Ramses III (Cooney 2024, pp. 239–43) was applied with a whitish-yellow paint. The coffin reused for Ramses VI (Cooney 2024, pp. 281–84) has the king’s name added in yellow paint.

9. Restoring the Element of Earth/Osiris

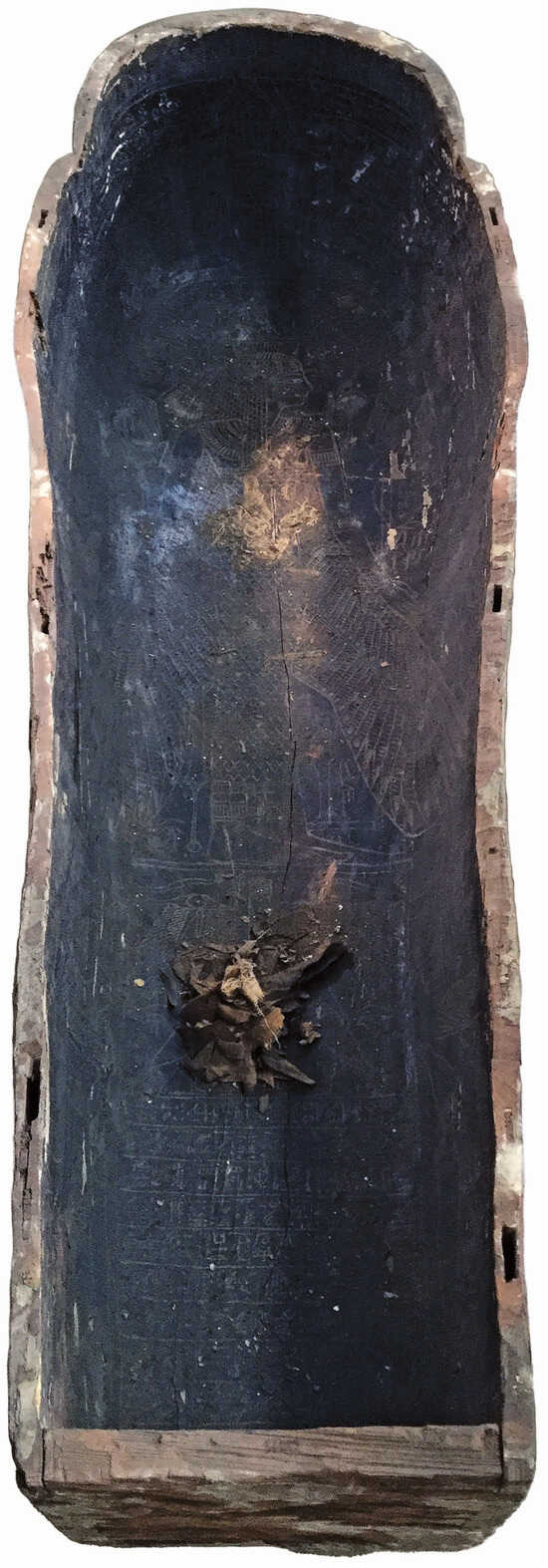

Some of the king’s coffins show the addition of thick black resinous material to the interior, potentially to add a divinizing, Osirian element back to the body containers after they had been stripped of valuables. Such black varnish has been shown to include imported and difficult to source materials like tree resins and bitumen, and it was an expensive commodity. It is visible on the coffin case and lid interior for Seqenenre Taa (Figure 6; Cooney 2024, pp. 119–26), which show chisel marks under the black substance, indicating a valuable interior was removed before it was added. The coffin of Thutmose I was covered with a black varnish on the interior surfaces after it was stripped and cut back for Panedjem I (Figure 7; Cooney 2024, pp. 299–305). The coffin used for Thutmose III has a restoration layer of thick black resinous material applied over a restored plastered and inscribed interior (Figure 8; Cooney 2024, pp. 199–207). Since this black layer covers over inscribed decoration, it seems the restoration of this Osirian element outweighed the importance of text visibility and/or that it was ritually applied during reburial. The coffin used for Ramses II does not have any such black resinous material on the inside of the piece (Figure 9; Cooney 2024, pp. 232–38), an interesting difference from the other coffins made for kings. Likewise, the coffin of Kamose does not show any application of the resinous black substance (Figure 10; Cooney 2024, pp. 285–89), suggesting this particular restoration was put into practice during later sweeps and after this piece had been put away in a reburial in Dra Abu el-Naga.

Figure 6.

Interior of the outer coffin case of Seqenenre Taa (CG 61001). Photo by UCLA Coffins Project, courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Cairo. From Recycling for Death by Cooney (2024), used with permission of the publisher, AUC Press.

Figure 7.

Interior of the coffin case of Thutmose I reused for Panedjem I (CG 61025). Photo by UCLA Coffins Project, courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Cairo. From Recycling for Death by Cooney (2024), used with permission of the publisher, AUC Press.

Figure 8.

Interior of the coffin case used for Thutmose III (CG 61014). Photo by UCLA Coffins Project, courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Cairo. From Recycling for Death by Cooney (2024), used with permission of the publisher, AUC Press.

Figure 9.

Interior of the coffin case used for Ramses II (CG 61020). Photo by UCLA Coffins Project, courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Cairo. From Recycling for Death by Cooney (2024), used with permission of the publisher, AUC Press.

Figure 10.

Interior of the coffin case of Kamose (TR.14.12.27.12). Photo by UCLA Coffins Project, courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Cairo. From Recycling for Death by Cooney (2024), used with permission of the publisher, AUC Press.

Only a few kings reburied in non-royal coffins have the addition of this black resinous material, including Amenhotep I (Cooney 2024, pp. 143–48), Thutmose II (Cooney 2024, pp. 193–98), and Ramses III (Cooney 2024, pp. 239–43).

10. Restoring the Element of Protective Iconography

The five kings’ coffins indicate that elements of protection had to be restored to the piece after the stripping of valuables. Iconographic elements like pectorals or sky-goddesses in the form of birds, or protective texts needed to be restored. The coffin used for Seqenenre Taa shows the repainting of a broad collar and a winged deity on the chest (Cooney 2024, pp. 119–24). The coffin for Kamose has many painted elements of protection restored to it, including a broad collar, a winged protective deity on the chest, and rishi features, also markers of kingship (Cooney 2024, pp. 285–89). The coffin used for Thutmose III has remnants of regilded broad collar, indicating it also had a winged bird on the chest as well, now mostly gone given the rough removal of gold at its caching. The interior of the coffin used for Thutmose III also shows a net or basket pattern incised into a plastered surface, suggestive of protective iconography (Brown 2020; Cooney 2024, pp. 199–207). The coffin used for Ramses II has arm bands accentuated in Egyptian blue and well as a double cartouche in black paint on the midbody (Cooney 2024, pp. 232–38).

Kings reburied in non-royal coffins show similar treatments, including Ahmose who has a board collar and pectoral painted onto the surface (Cooney 2024, pp. 127–32), Amenhotep I who has a winged vulture painted onto the chest and onto the back of the lid’s head end (Cooney 2024, pp. 143–48), Thutmose II who has a painted broad collar and winged vulture on the chest (Cooney 2024, pp. 193–98), Thutmose IV who has a vertical text band in black paint (Cooney 2024, pp. 254–58), Ramses I who received a hieratic protective inscription on the top of his head (Cooney 2024, pp. 223–26), Seti I who received a pectoral of sorts in the form of a double cartouche on top of the symbol for gold in black paint (Cooney 2024, pp. 227–31), Seti II (Cooney 2024, pp. 259–62), Saptah (Cooney 2024, pp. 263–66) and Ramses IV who only have a vertical text bands in black paint (Cooney 2024, pp. 276–80).

11. Restoring the Elements of Human Agency

The five kings’ coffins indicate it was important to restore the element of human agency to the coffins, particularly the eyes, nose, mouth, and ears, but also the hands if stylistically appropriate. If such features had been removed in the process of stripping valuables, they were restored with three-dimensional features in wood or with two-dimensional features drawn in paint. It is quite possible that coffins in which kings were reburied once were crafted with inlaid eyes, only to have them removed for their valuable materials, filled in with plaster, and repainted. The coffin reused for Ahmose (Cooney 2024, pp. 127–32) is a possible example of such treatment of the eyes, as is the coffin of Ahmes-Nefertari (Cooney 2024, pp. 133–37). Only non-invasive scanning techniques like X-ray or CT scan will reveal such restorations.

The inlaid eyes of Seqenenre Taa were removed in a sweep for valuables, and thus, it seems to have been important for the restorers to paint around the eyes and on to brows with Egyptian blue paint, even if those eyes were not filled in. The mouth of this coffin was lined in red paint (Cooney 2024, pp. 119–26), presumably adding an element of agency. The coffin for Kamose was potentially repainted in Egyptian blue after the removal of valuables, which is suggested by the thick application of blue paint over the king’s left ear. It is even possible that these ears were restored with plaster (Cooney 2024, pp. 285–89). The coffin of Thutmose I reused for Panedjem I has hands carefully restored with pieces of wood, after the removal of gold proved too rough for them (Cooney 2024, pp. 299–305). The coffin reused for Thutmose III has a very damaged surface, but the remaining gilding indicates that eyes, nose, mouth, and ears had been restored with a thin layer of gilding, only to be removed again later in a subsequent sweep of valuable commodities when the piece was cached (Cooney 2024, pp. 199–207). As for the coffin reused for Ramses II, his features have been fully repainted in Egyptian blue, white, and black. The eyes even have a touch of red paint at the inner canthus (Cooney 2024, pp. 232–38). If the eyes were once inlaid, which is quite possible given the overall quality of the piece, they have since been filled in and repainted. The corners and seam of the mouth have also been painted with blue paint. Even the nostrils were accentuated with the addition of blue paint, and we must presume this was to re-activate the nose after gold sheeting and other valuables were removed from the piece (Corcoran 2016).

Many non-royal coffins used to rebury kings suggest that elements of human agency had to be restored after gold sheeting was removed, in particular ears. The coffin used for Thutmose II has ears built up around the face using plaster, likely as a later restoration (Cooney 2024, pp. 193–98), as does the coffin used for Thutmose IV (Cooney 2024, pp. 254–58). The coffin reused for Seti I, has ears drawn on in two-dimensions with paint (Cooney 2024, pp. 227–31). Not every king was treated with such respect, however; the coffin in which Ramses III was reburied shows the entire surface of the lid covered with a wash of reddish-brown paint with no accentuation of the facial features (Cooney 2024, pp. 239–43). The coffins reused for Seti II and Ramses IV have no restored ears at all, whether in two or three dimensions (Cooney 2024, pp. 259–62, 276–80). We can arguably see a difference in restoration between those kings cached in KV 35 and those cached in TT 320.

12. Restoring the Element of Kingship

Theban agents of the 20th and 21st Dynasties also made sure to restore elements of kingship, like the uraeus on the brow, crook and flail if there were hands to hold them, and royal names. The coffin for Seqenenre Taa does not have a restored uraeus head, as the empty notch of a recommodified cobra body has not been filled. The plaster-modeled cobra body and tail is visible along the forehead. The early 18th Dynasty coffin for Seqenenre Taa was not crafted with any arms or hands to hold royal instruments (Cooney 2024, pp. 119–26), and thus none needed to be restored. The coffin used for Kamose has a restored divine beard in wood, painted blue with a blue chin strap (Cooney 2024, pp. 285–89). The coffin of Thutmose I was remade into Panedjem I’s coffin in the 21st Dynasty, and we can see that while a uraeus was restored to the forehead, it was decided not to place a crook and flail in the restored hands. Instead, Panedjem holds ankh and died signs in his fisted hands. This coffin has an empty hole for the beard, indicating the divine beard had been made of precious material and has been recommodified (Cooney 2024, pp. 299–305).

The coffin used to bury Thutmose III has attachment holes for a crook and flail, and since these holes are visible on the surface of the coffin, it is assumed these were the restored instruments, not those crafted for the original coffin. The crook and flail are now missing, and perhaps they were thus made of gilded wood. The king’s coffin for Thutmose III once had two uraeus holes for a vulture and a cobra, but one hole has been covered over with the new decorative surface of gilded plaster; the restored uraeus is now missing and was likely made of gilded wood. The beard is also missing (Cooney 2024, pp. 199–207).

The coffin used for Ramesses II has the most restorations of preserved royal insignia including painted, non-gilded, wooden uraeus, divine beard, and crook and flail (Cooney 2024, pp. 232–38). One assumes if these had been gilded, they would now be missing. There are two uraeus holes visible, one of them covered over by plaster, leaving the remaining wooden uraeus off-center and suggesting the original uraeus treatment on this king’s coffin was a double cobra and vulture version. Both the coffins used for Thutmose III (Cooney 2024, pp. 199–207) and Ramses II (Cooney 2024, pp. 232–38) originally had double uraeus holes meant to fit vulture and cobra uraei as seen on the coffin set of Tutankhamun or on the canopic jars of Amenhotep II and Horemheb (Dodson 1994). In both cases on the coffins of Thutmose III and Ramses II, a single, central uraeus was restored to the coffin, presumably because it was found to be more in line with current models. Interestingly, it seems the 20th and/or 21st Dynasty Theban agents reformed and idealized kingship at the same time that they restored its markers on these coffins. Indeed, all surviving royal images of 21st and 22nd Dynasty kings from the tombs of Tanis show single cobra uraei with no hint of double vulture and cobra versions (Montet 1947, 1951, 1960).

13. Restoring Coffins Originally Made for Kings

Only in the case of Thutmose I can we say that the coffin in question was originally made for the king for whom it was originally decorated. Of course, Thutmose I himself was removed from the coffin, presumably when his tomb was stripped in the 20th and 21st Dynasties, and that same coffin later modified for Panedjem I who sometimes styled himself as a king in the 21st Dynasty (Cooney 2024, pp. 299–305). The coffin in which Kamose was buried may also have been the coffin originally crafted for that king. The style of the rishi design lines up with a 17th Dynasty date (Miniaci 2011), but the coffin was modified after its removal from the original Dra Abu el-Naga tomb, likely having been stripped of precious metals and almost certainly repainted (Cooney 2024, pp. 285–89). Likewise, the coffin in which Seqenenre Taa was buried may have been originally crafted for him, but it was stripped of precious metals and redecorated for the king. However, the style and portraiture of the coffin for Seqenenre Taa seem later in style than the typical rishi and later than the style of the coffin of Kamose; it is also not cut from a single tree trunk but has more separately crafted elements (Cooney 2024, pp. 119–26). The coffins of Kamose and Seqenenre Taa are both early in date relative to the other coffins found in the royal caches and were both originally made for kings, but given their later redecoration and reuse, it is entirely possible that they were originally made for different kings than those reburied in them. Both of these coffins could have been reassigned to preferred pharaohs for display and reburial actions in the 20th and 21st Dynasties.

As for the coffin in which Ramses II was buried, Reeves (2017) has already argued for a post-Amarna date, suggesting it was originally made for Horemheb, a conclusion based on style, construction, and portraiture. Because there is clear evidence it was thoroughly modified and redecorated, the coffin in which Thutmose III was reburied could have originally belonged to another mid 18th Dynasty king entirely, perhaps Thutmose II or Amenhotep II. It may also have been made for Thutmose III, but any evidence about its original ownership has been irretrievably lost.

There is another interesting feature regarding coffin size and placement in a nested set. Indeed, all of these reused kings’ coffins indicate they were middle or outer coffins in a given royal set, and perhaps we should surmise that the inner pieces in the original coffin set included much more gold, or were even made of solid gold, and were thus completely recommodified at the end of the New Kingdom, providing the reason that only outer coffins of wood remain in the archaeological record. In other words, it is argued here that the corresponding inner pieces in a given king’s coffin set do not survive because they included so many precious materials that their structure could not be saved.

Only 18th Dynasty royal coffins are preserved in the Theban royal caches, suggesting that 19th and 20th Dynasty royal coffins were made of so many valuable materials that they were reused as commodities, rather than as coffins. In other words, the evidence for surviving kings’ coffins indicates that most of the Ramesside royal coffins were even made of solid gold, rather than wood with gold sheeting. The best comparison would be Tutankhamun’s innermost coffin and mummy mask (Reeves 2022) or the solid gold and silver coffins from Tanis (Montet 1947, 1951). Such solid gold pieces were almost certainly entirely recommodified during the 20th and 21st Dynasty crises and are therefore not preserved to us. Nesting solid gold coffins for Ramesside period kings helps explain some of the more extravagant burial systems, like the nesting sarcophagi preserved for the 19th Dynasty king Merneptah (Brock 1992). Such nesting sarcophagi would have provided security for that amount of gold in one of the more accessible and visible tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Indeed, given that one of the sarcophagi of Merneptah was reused for the 21st Dynasty king Pasebakhaenniut at Tanis, it is quite possible that the solid silver and gold coffins found in that same Tanite tomb were made of precious metals recycled from Theban royal funerary objects, like inner coffins. This cannot be proved without additional scientific investigation, however.

Except for Kamose’s coffin, which only shows the piece to have been opened once, the other four preserved king’s coffins show multiple instances of opening, indicating the removal of valuable commodities, followed by re-embellishment and reuse as a burial container, and then another opening for commodities. The same four king’s coffins show the need of the 21st Dynasty Theban agents to display their piety by reburying the kings in the appropriate body containers. I argue in Recycling for Death that this was a legal method of claiming power, in that the one who buries inherits, according to P. Bulaq X (Janssen and Pestman 1968; Cooney 2024, p. 74). Though it was not included in the High Priest’s cache in TT 320, the coffin of Kamose was likewise carefully redecorated for the king after it was opened and stripped of valuables.

The 20th and 21st Dynasty High Priests of Amen used these recrafted coffins as a means of claiming their political and ideological legitimacy. But how did their actions affect the value of the funerary objects in question or of the kings who were placed in them? It seems that 20th and 21st Dynasty agents knew that stripping the valuable gold, silver, and inlay materials rendered the craftsmanship less visible and thus less valuable. Therefore, even if they removed gold sheeting, there was an initial attempt to recover the surface with precious materials inside and out. The multiple openings of the coffins for Seqenenre Taa and Thutmose III, however, point towards the likelihood of coffins having been stripped of valuables again after restoration and reburial—which in and of itself indicates the later Theban agents felt the need to give back to their ancestors a bit of what they had taken. Thus, the 21st Dynasty High Priests of Amen had an appreciation of funerary art’s value, and they maintained as much of it as they could, albeit using lesser materials and just one redecorated coffin from a much larger ensemble. In their final forms, these king’s coffins were reduced to a fraction of the value compared to their original instantiations; they have much thinner case and lid sides, having had much of the thickness removed along with inlaid gold sheeting. They have been stripped of any gold leaf. They have lost their nesting sets. Royal implements have been removed. And so on.

That being said, within the group of ancestor kings, it seems to have been important to rebury some of these kings in royally bespoke coffins. Thus, some kings’ wooden coffins were assiduously maintained, regilded, and redecorated. Indeed, one particular king’s coffin was believed so valuable given its association with the foundational king, Thutmose I, that it was reused for Panedjem I. Interestingly, this is the only king’s coffin of the five that does not display an obvious royal nemes headdress; instead, the 18th Dynasty coffin was made with a simple Osirian head cloth, displaying vertical, inlaid stripes under the painted 21st Dynasty stripes (Cooney 2024, pp. 299–305). Perhaps Panedjem I felt it was more appropriate to take such a coffin rather than having himself buried in a coffin with a nemes-headdress. Whatever the reasoning behind this choice, he wanted his close inner circle to know he would occupy Thutmose I’s burial container.

Not every foundational king was reburied in a king’s coffin; Amenhotep I was reburied in a coffin with no clear markers of kingship original to the piece, though a uraeus was carefully crafted out of wood to update the coffin for this king (Cooney 2024, pp. 143–48). While the high priests systematically removed objects from the royal necropolis, they also re-embellished recycled, elite coffins to rebury the kings and queens. Some of those important personages were set apart in special objects reworked for a king, like Amenhotep I. But a special few—Seqenenre Taa, Thutmose III, and Ramses II—were reburied within obviously royal coffins.

These restorations were artistic actions, but few of these restorations seem particularly beautiful or aesthetically pleasing to us today, and we can imagine they were not impressive to 21st Dynasty ancient Egyptian priestly elites either. In short, it does not seem the 21st Dynasty Theban agents were acting out of motivation to create beautifully crafted miracles they could display to astonished onlookers. Rather, these Theban agents were looking to restore perceived royal powers to the dead and to showcase their own attempts to act piously, using the correct materials with the right magical properties. Theirs was arguably a very exclusive audience of fellow priests and ritualists, meaning a rough wash of yellow paint might have worked well enough in a ritual–magical context to create the golden element required to mark a king and to thus absolve them of any perceived wrongdoing from past recycling.

Finally, we must also remember that these craft actions occurred over a length of time, each king’s coffin showing multiple actions taking place over a few hundred years, indicating the continued ideological power of this funerary art (and of the human materiality contained therein) over the 20th and 21st Dynasty Theban agents. The divinized occupants within anthropoid coffins demanded reburial with markings showing their kingship. Many of the ancestor kings were thus at first reburied in re-gilded wooden objects in the late 20th and early 21st Dynasties. Many kings may even have been interred within nested sets after the first sweeps for valuables, rather than leaving each king to make do with just one coffin. The coffin lid of queen Ahhotep found in a reburial at Dra Abu el-Naga provides an example of one such, initial, 20th or early 21st Dynasty style reburial treatment; Ahhotep’s ensemble retains a thin layer of gilding as well as inlaid eyes, even though the many extra mortis and tenon joins indicate that this coffin was opened and sourced for valuables at least once (Cooney 2024, pp. 149–53). Since she was left in Dra Abu el-Naga, for whatever reason, and not cached with the others, this coffin did not suffer further recommodification. But other coffins did as later generations of Amen Priests modified the burials of these kings, taking more valuables each time. This is most visible on the coffin used to rebury Thutmose III. So important was this royal ancestor that the coffin was likely regilded twice, but with a thinner layer each time, until the coffin and its inhabitant were finally put away into the Royal Cache, after one final and brutal removal of whatever gold it had left to give. When they were finally cached, the ancestor kings were clearly no longer useful to the rulers of Thebes. In an ideological sense, 22nd Dynasty Theban agents had finally thrown off the yoke of these ancestor kings, in favor of embellishing the cults of Amen-Re, king of the gods, and Osiris, king of the duat.

Funding

This research was funded by the Antiquities Endowment Fund, courtesy of the American Research Center in Egypt, the Ahmanson Fund through the Cotsen Institute, UCLA, and multiple faculty research grants from UCLA.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the author.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Alisée Devillers, Amber Myers Wells, Nicholas Brown, and Kylie Thomsen for reading and commenting on this article. I would like the thank the Egyptian Museum Cairo at Tahrir Square for permission to study and publish the coffins mentioned here, in particular museum director, Sabah Abdelrazek, and curator, Sara Hassan. The research on these pieces was conducted during month long seasons in 2016 and 2018. Nicholas Brown and I also conducted another short season of work in 2019.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Royal Caches Chart

| Name | Date of Mummy & Coffin | Mummy Accession Number & Image | Coffin Accession Number & Image | Original Burial | Cache Reburial |

| Sekhemre-Wepmaat Intef | 17th Dynasty | Louvre E 3019 | Dra Abu el-Naga | ||

| Nubkheperre Intef | 17th Dynasty | British Museum EA 6652 | Dra Abu el-Naga | ||

| Sekhemre-Heruhirmaat Intef | 17th Dynasty | Louvre E 3020 | Dra Abu el-Naga | ||

| Sequenere-Taa | 17th Dynasty | CG 61051 | CG 61001 | Unknown | TT 320 |

| Mummy of Ahmose-Inhapi & Coffin of Ray | 17th Dynasty | CG 61053 | CG 61004 | WN A | TT 320 |

| Kamose | 17th Dynasty | TR 14.12.27.12 | Unknown | Dra Abu el-Naga | |

| Unknown Woman B – Tetisheri (?) | 17th Dynasty | CG 61056 | Unknown | TT 320 | |

| Ahhotep | 17th–18th Dynasty | CG 61006/JE 28501 | Unknown | Dra Abu el-Naga | |

| Ahmose-Meryetamen I | 18th Dynasty | CG 61052 | JE 53140 (outer) & JE 53140 (inner)  | Unknown | Deir el-Bahri 358 |

| Nebwenefer | 18th Dynasty | TR.2.5.15.1 | Unknown | TT 320 | |

| Ahmose I | 18th Dynasty | CG 61057 | CG 61002 | Unknown | TT 320 |

| Ahmose-Nefertari | 18th Dynasty | CG 61055 | CG 61003 | AN B? | TT 320 |

| Amenhotep I | 18th Dynasty | CG 61058 | CG 61005 | AN B?/KV 39? | TT 320 |

| Sa-Amun | 18th Dynasty | CG 61059 No image available | CG 61008 | Unknown | TT 320 |

| Satamun | 18th Dynasty | CG 61060 No image available | CG 61009 | Unknown | TT 320 |

| Senu | 18th Dynasty | CG 61010 | Unknown | TT 320 | |

| Ahmose-Henttimehu | 18th Dynasty | CG 61061 | CG 61012 | Unknown | TT 320 |

| Ahmose-Henttempet | 18th Dynasty | CG 61062 | CG 61017/JE 26222 | Unknown | TT 320 |

| Ahmose-sa-paari | 18th Dynasty | CG 61064 | CG 61007 | Unknown | TT 320 |

| Amenhotep II | 18th Dynasty | CG 61069* | SR 7/23516 * | KV 35 | KV 35 |

| Amenhotep III | 18th Dynasty | CG 61074 | CG 61036 (lid, originally for Seti II) & CG 61040 (case, originally for Ramses III)  | WV 22 | KV 35 |

| Thutmose II | 18th Dynasty | CG 61066 | CG 61013 | DB 358? | TT 320 |

| Thutmose III | 18th Dynasty | CG 61068 | CG 61014 | KV 34 | TT 320 |

| Thutmose I | 18th Dynasty | CG 61073 | CG 61035 | KV 43 | KV 35 |

| 18th Dynasty Amenhotep IV /Akhenaten (?) or Smenkhare (?) | 18th Dynasty | CG 61075 | JE 39627 ** | TA 26 (Akhenaten ?) or TA 28 (Smenkhare ?) | KV 55 |

| Unknown Woman-Baket (?) | 18th Dynasty | CG 61076 | CG 61015 | Unknown | TT 320 |

| Mummy of Unknown Man C & Coffin of Nebseni | 18th Dynasty | CG 61067 | CG 61016 | Unknown | TT 320 |

| Anonymous Elder Woman | 18th Dynasty (?) | CG 61070 | Unknown | KV 35 | |

| Anonymous Boy (Wabkhausenu?) | 18th Dynasty (?) | CG 61071 | Unknown | KV 35 | |

| Anonymous Younger Woman | 18th Dynasty (?) | CG 61072 | Unknown | KV 35 | |

| Seti I | 19th Dynasty | CG 61077 | CG 61019 | KV 17 | TT 320 |

| Mummy of Anonymous Man & (replacement) Coffin of Ramses I | 19th–21st Dynasty | CG 61018/JE 26225 | KV 16 | TT 320 | |

| Ramses II | 19th Dynasty | CG 61078 | CG 61020 | KV 7 | TT 320 |

| Ramses III | Mummy: 20th Dynasty & Coffin: 18th–19th Dynasty | CG 61083 | CG 61026 (replacement cartonnage)/CG 61040 (original case, reused for Amenhotep III)  | KV 11 | TT 320 |

| Mummy of Ray & Coffin of Paherypedjett | 19th–20th/17th Dynasty | CG 61054 | CG 61022 | Unknown | TT 320 |

| Mummy of Merenptah & Coffin Case of Setnakht | 19th Dynasty | CG 61079 | CG 61039 (coffin case of Setnakht) | KV 8 | KV 35 |

| Seti II | 19th Dynasty | CG 61081 | CG 61036 (lid, reused for Amenhotep III)/CG 61037 (case) | KV 15 | KV 35 |

| Saptah | 19th Dynasty | CG 61080 | CG 61038 | KV 47 | KV 35 |

| Ramses IV | 20th Dynasty | CG 61084 | CG 61041 | KV 2 | KV 35 |

| Ramses V | 20th Dynasty | CG 61085 | CG 61042 No image available | KV 9 | KV 35 |

| Ramses VI | 20th Dynasty | CG 61086 | CG 61043 | KV 9 | KV 35 |

| Mummy of Satkames & Coffin of Padiamen | 19th–20th Dynasty | CG 61063 | CG 61011/JE 26200 | Unknown | TT 320 |

| Mummy of Unknown Woman D (Tawosret?) & Coffin Lid of Setnakht | 21st Dynasty | CG 61082 | CG 61039 | KV14/ Unknown | KV 35 |

| Nodjmet | 21st Dynasty | CG 61087 | CG 61024/JE 26215 | WN A? | TT 320 |

| Maatkare-Mutemhet | 21st Dynasty | CG 61088 | CG 61028/JE 26200 | TT 320? | TT 320 |

| Duathathor-Henttawy | 21st Dynasty | CG 61090 | CG 61026/JE 26204 | WN A? | TT 320 |

| Tayuheret | 21st Dynasty | CG 61091 | CG 61032/JE 26196 | TT 320? | TT 320 |

| Masaharta | 21st Dynasty | CG 61092 | CG 61027/JE 26195 | TT 320 | TT 320 |

| Panedjem II | 21st Dynasty | CG 61094 | CG 61029/JE 26197 | TT 320 | TT 320 |

| Nesikhonsu | 21st Dynasty | CG 61095 | CG 61030/JE 26199 | TT 320 | TT 320 |

| Nesitanebetishru | 21st Dynasty | CG 61096 | CG 61033/JE 26202 | TT 320 | TT 320 |

| Djedptahiuefankh | 22nd Dynasty | CG 61097 | CG 61034/JE 26201 | TT 320 | TT 320 |

| Unknown Man E | 20th Dynasty | CG 61098 | CG 61023 | Unknown | TT 320 |

| Ramses IX | 20th Dynasty | SR 1/10211/CG 61030 No Image Available | KV 6 | TT 320 | |

| Isetemkhebit | 21st Dynasty | CG 61093 | CG 61031/JE 26198 | TT 320 | TT 320 |

| Mummy of Thutmose I (?) & (Reused) Coffin of Pinudjem I | Mummy: 18th Dynasty & Coffin: 18th & 21st Dynasty | CG 61065 | CG 61025/JE 26217 | KV 20 & KV38 | TT 320 |

| Images with * courtesy of the Egyptological Archives and Library of the Università degli Studi di Milano. All other B&W images after Smith 1912; Daressy 1909; Winlock 1924. Image with ** courtesy of Nicholas R. Brown. | |||||

Notes

| 1 | One could also conduct a separate study on queens’ coffins and the precise means of social separation for these elite women from the rest of society, but a queen’s identity was less divinely defined than the king and more nuanced in terms of iconography. As for those New Kingdom women who became king—like Hatshepsut, Nefertiti, and Tawosret—we do not have their coffins preserved to perform such a material/iconographic study, unless the coffins made for Tutankhamun were reused from Nefertiti’s set as co-king (Reeves 2015). |

| 2 | I have not been able to examine the coffins of Intef Sekhemre Heruhirmaat (Louvre E3020), Intef Sekhemre-Wepmaat (Louvre E 3019), and Nubkheperre Intef VI (British Museum EA6652) in person. Photographic examination of the exterior of the British Museum coffin from online photos (https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA6652 URL accessed 8 May 2025) shows pinholes typical for the attachment of sheet gold even though the coffin lid is finished with a thin layer of gilding. Photographic examination of the interior of the British Museum Intef coffin shows modifications, including thinned out lid sides, unfinished and rough seams and an application of dark resin over the edges of those modifications, suggesting the removal of valuable commodities before the coffin was potentially re-embellished and the king reburied. Louvre E3020 has an inscription written in black on the chest over the polychrome decoration, suggestive of redecoration for reburial. In-person analysis is necessary to prove any of these suppositions. For more on these coffins see (Winlock 1924; Polz 2022; Galán 2017). |

References

- Abdel–Maksoud, Gomaa, and Abdel–Rahman El-Amin. 2011. A review on the materials used during the mummification processes in ancient Egypt. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 11: 129–50. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle MacLeod, Caroline. Forthcoming. Transformations in the Materiality of Death: Rishi Coffins and the Second Intermediate Period. In Proceedings of the Second Vatican Coffins Conference. Edited by Alessia Amenta and Capozzo Mario. Rome: Musei Vaticani.

- Aufrère, Sydney. 1991. L’univers minéral dans la pensée égyptienne. 2 vols. Bibliothèque d’étude 105. Le Caire: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Bertsch, Julia, Katja Broschat, and Christian Eckmann. 2017. Die Arbeiten der Jahre 2014 bis 2016. In e-Forschungsberichte des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts (August 2017). Kairo: Die Goldblechbeschläge aus dem Grab des Tutanchamun, pp. 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscagli, Maurizia. 2014. Stuff Theory: Everyday Objects, Radical Materialism, 1st ed. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, Edwin C. 1992. The tomb of Merenptaḥ and its sarcophagi. In After Tut’Ankhamūn: Research and Excavation in the Royal Necropolis at Thebes. Edited by Edwin C. Brock. London: Kegan Paul, pp. 122–40. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Nicholas R. 2020. Raise Me Up and Repel My Weariness! A Study of the Coffin of Thutmose III (CG 61014). MDAIK 76: 11–35. [Google Scholar]