Abstract

William Courtenay, 3rd Viscount Courtenay and 9th Earl of Devon (1768–1835), has been most remembered for his romantic relationship with author and slave owner, William Beckford (1760–1844), which scandalized London society in 1784. However, the 9th Earl’s life after this event has received little attention despite his artistic contributions to the built environment of his ancestral home of Powderham Castle in Devon. In the 1790s, he created a series of flower watercolors on paper and cabinets under the supervision of his drawing master, William Marshall Craig (c.1765–1827). These artworks complicate ideas about gendered expectations of amateur artistic subjects, with flower painting being largely understood as a feminine accomplishment. This article explores the Earl’s watercolors in the context of the spaces at Powderham to argue they are evidence of his effeminate behavior and participation in female activities alongside his thirteen sisters. The association of these objects with a man attracted to those of his own sex contribute to studies of queerness, amateur art, and the country house in the late eighteenth century.

1. Introduction

On the 6th of May 1784, William Beckford (1760–1844) wrote to Samuel Henley (1740–1815) reporting the activities of William Courtenay, 3rd Viscount Courtenay and 9th Earl of Devon (1768–1835).1 Beckford stated that “Wm I believe quite lost in flowers & foolery at present, perhaps you may raise him out of the lap of idleness, but the task will be difficult” (Beckford 1784). At this time, Beckford and the Earl had been in a romantic relationship that began in 1779.2 According to this letter, Beckford suggested cultivating, studying, and possibly even drawing flowers to be an idle pursuit that was a waste of time for his young love interest. Beckford wanted to steer the 9th Earl to loftier pursuits, including music and poetry, by having Henley, his friend, become Courtenay’s tutor. The 9th Earl had recently completed his education at Westminster School at the age of fifteen. Henley, a former professor of philosophy at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, then living in Suffolk, received this letter the same year he published the English translation of Beckford’s Vathak.3 An accomplished schoolteacher, well versed in languages, antiquity, and classical philosophy, he would be able to teach the Earl all the subjects associated with male aristocratic culture of the eighteenth century. These educational pursuits usually did not include the domestic and often feminized study of flowers. Henley’s tenure did not outlast the separation of Beckford and the 9th Earl in the same year of the letter, however. This meant that—as this article will explore—the Earl was able to pursue ‘flowers and foolery’ throughout his life.

When Beckford wrote his letter to Henley in May of 1784, he unwittingly foreshadowed the importance of flowers and floral design in the artistic atmosphere of Powderham Castle during the tenure of the 9th Earl of Devon. If the Beckford letter is referring to drawing flowers as well as growing them, then there may be earlier works by the Earl that are now lost. However, the existing evidence suggests that it was in the last decade of the eighteenth century that the Earl’s production of images of flowers and admiration for them reached their pinnacle. The surviving floral watercolors that he created on paper and furniture—working under the supervision of his drawing master, William Marshall Craig (c.1765–1827)—all date to the 1790s.4 By that time, the Earl was a mature man who had come into his title and estates, allowing him to participate in whatever activity he chose. His choice was the growth, study, and depiction of flowers that adorned both the exterior and interior spaces of Powderham. This article will examine the flower paintings of the Earl within the contexts of their country house setting, the Dutch still-life tradition, and the Courtenay family’s artistic legacy. The creation of these artworks served multiple purposes for the Earl, including providing the opportunity to capture his cultivated flowers in detailed arrangements and to engage in an activity that allowed him to spend time with some of his thirteen sisters. Alongside these motives, I will argue that, when considered in relation to gendered ideas about amateur art, the watercolors fortify the Earl’s status as an effeminate man and allowed him to engage with this element of his identity. These behaviors, combined with his attraction to adult males, indicate his belonging to the “third sex” of eighteenth-century society.5

Contemporary observers of the 9th Earl and his family commented on his effeminate nature. In her 1849 autobiography, Elizabeth Ham looked back on a visit to the park at Powderham that she had made with her two sisters in 1800. She recounted her thoughts on the behavior of the Earl:

Because he was always in the company of his sisters, the Earl appeared to Ham as actually a woman. Her use of the terms “fair” and “delicate” indicate feminine qualities, contrasting with masculine ideals of physical strength expected by the 1800s (Janes 2016, p. 100). Interestingly, one of the arguments for the association of women with depictions of flowers was the idea that they, like their subjects, were beautiful and delicate (Sloan 2000, p. 45). Ham’s comment on the Earl’s apparent resistance to socializing with members of his own sex also indicates his effeminacy and did not fit with her expectations of how a gentlemen should behave. Instead, he was always in the company of his sisters, creating flower paintings in a domestic, familial environment.He was the last of that branch of the family, and, I think, of ten children, all the rest girls. From the fair and delicate appearance of his Lordship, and from the circumstance of his being always seen with his sisters, and never with any gentlemen, I wove my own romance about him, and set him down to be really a daughter too.(Ham 1945, p. 51)

The Earl’s paintings of flowers created within this domestic environment do not fit within heteronormative ideas of gendered amateur arts of the late eighteenth century. Often associated with domestic craft, flower drawing was viewed as a pursuit practiced by female amateurs. Male aristocratic artists should, it was generally believed, focus on other subjects, such as architecture or landscape. Eighteenth-century amateur artists tended to be from the upper levels of society, since the practice required leisure time and expenditure on both materials and instruction. The Oxford English Dictionary traces the origin of “amateur” to the classical Latin word amator, which means “lover”.6 Thus, an amateur pursues painting and drawing out of a love for art, and not for monetary or professional gain. Kim Sloan has observed that it was around 1780 that the word “amateur” came to denote a person with a love for the arts who actually practiced them (Sloan 2000, p. 7). Following these definitions, the Earl was an amateur artist because he created flower watercolors for his own personal enjoyment.

In their studies of eighteenth-century amateur art, scholars disagree over the extent to which men participated in flower painting, but they do agree that this was a field dominated by women. The difficulty is those who observe that men did paint botanical and/or decorative paintings of flowers tend not to provide specific examples, in contrast to studies of women, which feature bountiful examples of surviving works. Ann Bermingham, for example, has shown that botany and flower painting became the perceived domain of female amateur practitioners in the late eighteenth century as part of an emerging consumer culture, which expected elite women to pursue leisure activities at home (Bermingham 2000, pp. 201–4). Marcia Pointon conversely argues that both men and women practiced flower drawing, citing professional male artists who practiced in the Dutch still-life and botanical traditions, including Richard Earlom, Thomas Green, Richard Anthony Salisbury, and Peter Brown. However, Pointon does not provide any examples of male amateur artists (Pointon 1997, p. 133). It is this apparent lack of male amateur flower painting and the genre’s firm association with women during both the period and in scholarship that makes the Earl’s work an important contribution to the discussion of the gendered nature of eighteenth-century art.

2. The Flowers and Their Sources

On display in what is now the White Drawing Room at Powderham are six framed flower watercolors by the 9th Earl.7 The primary evidence for this attribution are signatures on two of the artworks. The first is a painting of mixed flowers in a vase, inscribed “Courtenay 1796” (Figure 1). This signature matches the one used by the 9th Earl in account books and letters.8 In the second example, a painted group of mixed flowers on a smaller sheet, the Earl takes clear credit for the watercolor by stating his title at the time of its creation in the signature: “Ld. Visct. Courtenay fecit. 1799” (Figure 2). Further evidence of authorship is to be found in two flower watercolors located in the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge. Though they do not have a clear provenance, the date and signatures associate them with the Courtenay family. They are signed “Courtenay—1796” and “Courtenay—1797” and are similar in size to the 1799 Powderham artworks (Figure 3 and Figure 4). All four of the Earl’s signatures are in similar handwriting, further linking the artworks to the Courtenay family. When the Powderham works are compared to the two examples in the Fitzwilliam Museum, it is clear all these works were executed by the same hand. Despite the fading of the watercolor pigments over time making the identification of individual blooms complicated, the similarities in the overall color palettes used support the attribution.

Figure 1.

William Courtenay, 3rd Viscount Courtenay and 9th Earl of Devon, Flowers in a Vase, 1796. Watercolor on paper, 26 cm × 36 cm. Signed: “Courtenay 1796”. Powderham Castle. Credit line: by permission of the Earl of Devon.

Figure 2.

William Courtenay, 3rd Viscount Courtenay and 9th Earl of Devon, Mixed Flowers, 1799. Watercolor on paper, 14 cm × 23 cm. Signed: “Ld. Visct. Courtenay fecit. 1799”. Powderham Castle. Credit line: by permission of the Earl of Devon.

Figure 3.

William Courtenay, 3rd Viscount Courtenay and 9th Earl of Devon, A White Rose, 1796. Watercolor on paper, 29 cm × 22 cm. Signed: “Courtenay—1796”. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Credit line: Photograph© The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge.

Figure 4.

William Courtenay, 3rd Viscount Courtenay and 9th Earl of Devon, Mixed Flowers, 1797. Watercolor on paper, 30 cm × 24 cm. Signed: “Courtenay 1797”. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Credit line: Photograph© The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge.

As floral watercolors are an art form associated with predominantly female domestic accomplishments, the Earl’s sisters are sometimes mentioned as artists working alongside their brother. In his 1963 Country Life article about Powderham, for example, Mark Girouard pointed to the flower watercolors as evidence of the artistic talent of both the 9th Earl and his sisters (Girouard 1963, p. 143). It is likely, given their close relationship, that the paintings were created by the Earl during drawing lessons taken alongside one or more of his sisters. During these sessions, the Earl and his sisters could copy examples of flowers in drawing manuals or their tutor’s own works as well as live flowers. At the time the paintings were produced, Lucy, Harriet, Caroline, Matilda, Sophia, and Louisa were all living at Powderham alongside the Earl. This raises the possibility of one or more of the sisters being involved in the works; however, all the evidence, as laid out above, points to the six watercolors in the White Drawing Room being solely the work of the Earl. It would be instructive if any of the sisters’ independent works could be located and compared to those by the Earl. All the sisters eventually married and moved to their husbands’ estates, so they probably took their flower pieces with them while the Earl’s arrangements stayed at Powderham. However, the decorations of the cabinets in the room provided an opportunity for the siblings to collaborate, as will be discussed below.

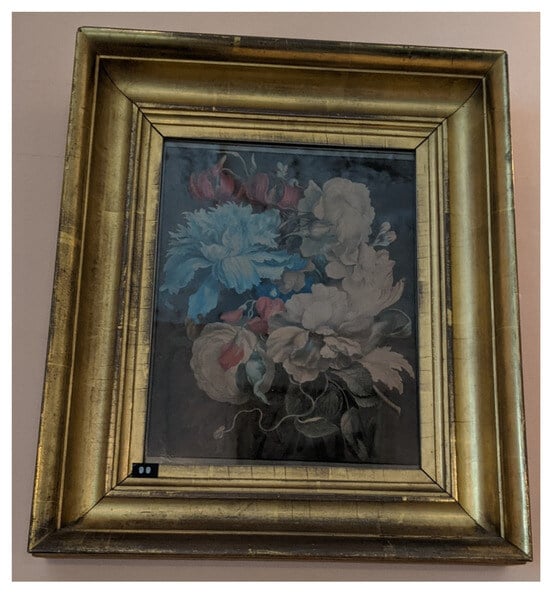

A major source of inspiration for the Earl’s watercolors was the instruction of his drawing master, William Marshall Craig. For amateur artists, technical ability was formed during lessons with such tutors. It is not clear when Craig became drawing master to the Courtenay family, although it was likely after he moved to his London address at 80 Charlotte Street from Manchester in 1791 (Edwards 1930, p. 200). In the years thereafter, Craig presented works at the Royal Academy’s annual exhibition, including landscapes of the Devon countryside, views of Powderham Castle, and a portrait of the 9th Earl (Royal Academy 1799, p. 27; Mallalieu 2002, p. 102).9 The Earl and Craig thus had a close working relationship as patron and artist as well as pupil and master. Furthermore, the Earl, together with the Chamberlain to Queen Charlotte and George Douglas, Earl of Morton, was sponsor to Craig’s sixth son, Henry Douglas, when he was born in 1800 (Edwards 1930, p. 200). The main evidence of Craig’s position as drawing master is artwork by him in the Earl’s collection. Flower watercolors created by Craig are listed in the catalogue of an 1816 sale of the Earl’s artworks, including six loose drawings of flowers (Christie 1816, p. 7). There are also Craig’s paintings which remain at Powderham today, including a still life with mixed flowers, signed and dated 1800 (Figure 5). While this painting was created later than the majority of the 9th Earl’s watercolors, there could well have been earlier flower paintings by Craig at Powderham that have since been sold, which were used as instructional examples in accordance with common practice.

Figure 5.

William Marshall Craig, Summer Flowers in a Porcelain Vase, 1800. Watercolor on paper, 57 cm × 66 cm. Signed: “W.M. Craig 1800”. Powderham Castle. Credit line: by permission of the Earl of Devon.

Drawing lessons would have taken place at either Powderham or the Courtenays’ London House in Grosvenor Square. Unfortunately, documentation of Craig’s lessons with the Earl is scarce. There is no record of payments for drawing lessons in either the Devon Heritage Centre or the Powderham archive. The timing of Craig’s instruction in watercolor is interesting because by the 1790s, the 9th Earl was a mature man and not a young boy. He would presumably have already learned to draw and paint during his time at Westminster from 1779 to 1784 (Presswell 2009, p. 13). As Kim Sloan has shown in the case of Eton College, if an aristocratic public school did not offer drawing lessons as part of its official curriculum, then drawing masters would offer services near the institutions so that children could take supplementary lessons (Sloan 1997, p. 290). However, Craig arrived in London after the Earl had left school, so all the instruction he provided must have come later.

That the Earl was in his late twenties when he started painting the extant flower watercolors is very striking. It indicates that he purposely chose to take up this art form as a matter of personal interest. His younger sisters would presumably have been learning to draw at around this time in the late 1790s, and so he probably participated in this activity with them at Powderham. Formal and informal drawing instruction at home was a well-established part of young ladies’ education in the later part of the eighteenth century (Sloan 1997, p. 260). As Amy Harris has demonstrated, siblings would typically learn at home together at a young age before boys went off to boarding schools for formal education (Harris 2012, p. 40).

To guide them in their endeavors, amateur artists and their drawing masters had access to drawing manuals devoted to flower painting, including information on the coloring, shape, and seasonality of plants. Alongside in-person instruction, Craig would likely have taught his pupils using his own drawing manuals and extant treatises. His instruction may well have drawn on a Dutch treatise by Gerard de Lairesse, entitled A Treatise on the Art of Painting, in all its Branches, which Craig later republished in 1817. However, the text had already been translated into English in 1728, and Craig’s commentary in his new edition indicates that he had used it previously. In his concluding essay, Craig states the following: “I have done no more, on the present occasion, than to supervise the former English translation, which I found to be very scarce; and I had repeatedly recommended it in my lectures at the Royal Institution, as the best work on art that my auditors could consult” (de Lairesse 1817, p. 275). It thus seems likely that Craig would have used de Lairesse’s Treatise in his early tutoring practice at Powderham.

There is evidence that the Earl owned at least one of Craig’s later texts. A single folio from Craig’s The Complete Instructor in Drawing, published in 1806, is tucked into the Courtenay papers in the Devon Heritage Centre archive. It is unclear what happened to the rest of the book. Dedicated to the directors of the British Institution, Craig’s book was nevertheless aimed at a broad audience. He promises that “the Work may be given as a means of study to any Child able to hold a pencil, and will lead him regularly forwards through a Complete Series of Instructive Drawing” (Craig 1806, p. 2). The manual then provides examples of shapes and landscape motifs that the student is intended to copy in order to understand line, shape, and shading. While the inventories of books in the castle for 1803 and 1835 do not list any drawing manuals, it is possible that the 9th Earl took such books, perhaps including ones by Craig, when he left the country in 1811 to escape a charge for sodomy (Hicks 1803; Cardwell 1835; Hyde 1970, pp. 73–74).

Drawing manuals routinely defined both botanical and decorative flower painting as a practice available to women artists. The 1728 English translation of de Lairesse’s Treatise states that “amidst the various choices in the art of painting, none is more feminine, or proper for women than flower painting” (de Lairesse 1817, p. 240). As the century progressed, amateur artistic instruction became increasingly marketed towards women. Sloan attributes this to increased demand around 1760, when women wanted to have access to instruction in drawing, especially in drawing landscapes, because they had not received the same formal training as their male relatives. The increasing number of drawing manuals dedicated to representing flowers after 1760 certainly describe the art as an amateur feminine pursuit. Their titles include Drawing Book for Ladies, or Complete Florist; A New Treatise on Flower Painting, or Every Lady her Own Drawing Master; and A New Practical Treatise on The Art of Flower Painting and Drawing with Water Colours, for the Amusement and Instruction of All Young Ladies who have a Taste for Drawing (Heckle 1785; Brown 1803; G. Riley 1813). As Ann Bermingham has observed, these titles suggest that by the end of the eighteenth century, flower painting was considered a female accomplishment (Bermingham 2000, p. 203). Therefore, by the time the 9th Earl was consulting drawing manuals and discussing his work with Craig, the literature that identified flower painting as an occupation specifically for ladies was well established.

In the analysis of the Earl’s watercolors, certain blooms from these manuals will be referenced to demonstrate the techniques utilized, trace trends in eighteenth-century flower art, and attribute meaning to individual flowers. The objective of identifying the flowers here is not to unpack any precise symbolism but rather to place the watercolors in conversation with each other. The symbolic meaning of flowers, known as “the language of flowers”, outside of religious contexts was only in the early stages of its development in the late eighteenth century. The floral lexicon of emotions did not become mainstream until the nineteenth century. The Earl would not, for example, have had access to instructional books on the meaning of individual blooms, such as Charlotte de La Tour’s La Langage des Fleurs, published in 1819 in France (Bermingham 2000, p. 208; Coats 1975, p. 15). However, placing the 9th Earl’s watercolors within the context of his life and botanical pursuits provides valuable insights into his interests and identity.

The main goal of these floral paintings—as with all botanicals, decorative florals, or other images of nature—was to preserve the beauty and elegance of a fleeting experience. As Gill Saunders has written, “illustration stands as a substitute for the thing itself, which is ephemeral, fragile, and often unable to survive removal from its original environment” (Saunders 1995, p. 7). Each of the Earl’s four larger compositions at Powderham depict groups of mixed flowers set within an interior space. His watercolors specifically preserve blooms from certain seasons and flowers he cultivated within the grounds at Powderham. The growing and scientific study of flowers in gardens on aristocratic estates was considered appropriate for upper-class men. Collections of exotic shrubbery and flowers were planted in ornamental gardens for the enjoyment of families and their visitors. As Mark Laird observes, though creating flower gardens appealed to women, there are examples of single men participating in this activity, including William Constable at his home of Burton Constable (Laird 1999, p. 18). Specimens from these flower collections were captured in illustrations that were usually kept in albums rather than displayed in frames on the walls of homes. In the eighteenth century, amateur artists, predominantly women, would paint florilegia in watercolor and label individual parts of the plants (Sloan 2000, p. 228). A group of 136 flower collages produced by Booth Grey in the 1790s follow this tradition of botanical imagery, though they were created using cut paper.10 Grey, a younger son of the Countess of Stamford, was an amateur artist thought to be a member of Mrs. Mary Delany’s circle who had access to the Duchess of Portland’s botanical collection at Bulstrode, Buckinghamshire (Reeder 2009, p. 225). Unlike the still-life tradition followed by the Earl, in which a variety of flowers are assembled together, thereby deemphasizing their individual traits, Grey’s collages are detailed creations of singular plants that are individually labeled. The 9th Earl’s larger paintings are more closely associated with the compositions of another amateur artist, Princess Elizabeth (1770–1840), who used elements of seventeenth-century Dutch painting to create images of flowers in neoclassical vases (Sloan 2000, p. 76; Roberts 2004, p. 146).11

As the Earl’s paintings represent floral arrangements, they can depict different flowers in bloom during a particular season, suggesting the timing of his artistic activity within the calendar of social events of the aristocracy. There are two watercolors with a similar composition, featuring the same grey vase but showing different types of flowers (Figure 1 and Figure 5). The flowers in the 1796 picture bloom in the same season, thereby linking their collection, display, and depiction to the changing environment of the landscape at Powderham. The painting depicts white roses, irises, lilium superbum (turk-cap lilies), passiflora caelurea (blue passionflower), white foxglove, and other flowers that bloom in summer (Figure 1). These flowers are recorded as summer blooms in eighteenth-century drawing manuals. Bowles’s Florist (1785), for instance, lists the iris as a June bloom, the fox-glove as flowering in July, the lily as an August flower, and the passionflower as a September bloom (Bowles 1785a, pp. 13–17). However, these flowers could well be seen at the same time, depending on the conditions of a particular year. It is likely that summer flowers were chosen because it was a season particularly abundant in blooms, with fresh flowers readily available. Furthermore, the Earl was also at Powderham in the months of July and August, as the social season in London usually took place from November to June (Greig 2013, p. 6). It is likely, given his access to fresh flowers at home in Devon, that the Earl painted arrangements set in a container in front of him, with the blooms and their position in the bunch having been carefully considered. This amateur practice contrasts strikingly with professional flower painting in which artists often relied on sketches of flowers made at different times of the year to incorporate into their compositions (Talley 1983, pp. 152–53).

The other watercolor with a grey vase has a more artificial arrangement in terms of bloom month (Figure 6). The roses, irises, and lilies depicted bloom together in summer, but the yellow and purple black auricula in the lower left of the bouquet appear in spring. Bowles identifies auriculas as a May flower and states that it is “by the Gardener’s art, so varied that a particular Description of its Varieties would be endless” (Bowles 1785a, p. 11). The representations of flowers with different blooming periods suggest that this arrangement is a formulated depiction of late spring and early summer flowers, using preliminary paintings or drawings executed at different times. Certainly, scholars of Dutch still life have demonstrated that flower compositions involved bringing together individual parts of the natural world in an artificial formulation of the artist’s creation. For example, Celeste Brusati has explored how Dutch floral still lifes give the illusion of being faithfully copied from nature even though the combination of flowers would have been impossible to achieve in real life. This is because many of these seventeenth-century paintings depict flowers that do not bloom in the same season (Brusati 1997, p. 145). Professional flower artists of this Dutch tradition were mostly men, something that the Earl would have been aware of based on his art collection, which included paintings by Simon Pietersz Verelst, Jan Davidsz De Heem, and Rachel Ruysch, a relatively rare professional woman floral painter. (Christie 1816, p. 9). It seems, however, that in eighteenth-century England, amateur artists working in this Dutch style of decorative painting were mostly women.

Figure 6.

William Courtenay, 3rd Viscount Courtenay and 9th Earl of Devon, Mixed Summer Flowers. Watercolor on paper, 49 cm × 36 cm. Powderham Castle. Credit line: by permission of the Earl of Devon.

While flowers are the focus of the Earl’s watercolors, other details such as the butterfly in Mixed Summer Flowers (Figure 6) relate to the Dutch tradition. Butterflies were regularly included in botanical studies and decorative florals during the eighteenth century, but their inclusion in still life painting comes from an older tradition (Saunders 1995, p. 86). In seventeenth-century Dutch art, they were symbols of transformation or the fleeting nature of life because of their short life span. In this way, the butterfly relates to the flowers in their temporary beauty, thereby reminding viewers of their own transient existence on this earth. Alternatively, when the butterfly is read through a Christian lens, it can be viewed as a promise of life after death. In his analysis of symbolism in Dutch flower painting, Paul Taylor points to a poem by Jan Luiken about the transformation of a caterpillar into a butterfly to demonstrate the use of the insect as a symbol of the resurrection of the human body after the Last Judgment (Taylor 1995, p. 75). The Earl could have been aware of one or more of these symbolic traditions, or he could simply have been using the butterfly as a decorative addition to his still life.

Craig would have been well placed to teach the Earl about the symbolism of Dutch still lifes. There are notable similarities between Craig’s 1800 work and the Earl’s compositions (Figure 5). All the arrangements are set against grey-black backgrounds in order to highlight the colorful blooms. According to Craig’s edited version of de Lairesse, “all flowers and greens look well on a grey ground” (de Lairesse 1817, p. 244). Furthermore, white blooms are placed in the center of all these works, framed by colorful flowers and green leaves. This conceit can also be linked to de Lairesse, who recommended placing white in the middle of a bunch of flowers in order to set off the colors of the other blooms (de Lairesse 1817, p. 247). Such dialogue between treatise, drawing master, and pupil demonstrate how techniques in flower painting could be passed on through reading, conversation, observation, and practice.

3. Creating Floral Interiors

The flowers came from the natural world outside Powderham Castle, but the objects and spaces with which they interacted were indoors. The inventories of Powderham taken in 1803 and 1835 reflect the family’s interest in collecting and displaying fresh flowers, listing flower stands and pots and vases used for these purposes. The 1803 inventory, for example, lists “a pair of vases on pedestals” and “2 China flower potts on gilded stands” in the Music Room (Hicks 1803, p. 5). Lord Courtenay’s dressing room, meanwhile, had “2 Elegantly Enameld china jars on chimney piece”, whilst his bedroom had “2 flower stands and 8 glasses, 1 flower pot” (Hicks 1803, pp. 11–12). The sitting room next to the library included “a marble vase on chimneypiece.” Two of the Earl’s watercolors feature vases which were presumably part of this collection (Figure 1 and Figure 6). The grey jasperware vase with designs similar to those created by Josiah Wedgwood indicates a late eighteenth-century material culture that was readily available. Indeed, the 1835 inventory of Powderham records a pair of Wedgwood urns in the storeroom of the west tower (Cardwell 1835, p. 9). As was typical of Wedgwood’s designs for flower containers, these vases are neo-classical in shape, with stylized acanthus leaf detailing at the base (Reilly 1992; Hunt 2021; Marcus 1952, p. 172).

The interiors of Powderham were not only decorated with flowers and paintings of flowers; they also contained furniture decorated with floral motifs. The White Drawing Room at Powderham now also houses two cabinets painted by the 9th Earl (Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9). Previous scholarship and contemporary accounts of the cabinets attribute them solely to the Earl, although mention is also made of the artistic activities of his sisters. Lady Pepys commented that the two painted cabinets were thought to be the work of the Earl. However, in the same sentence, she indicated that silk needlework inserted on a different marble-top table in the same room was the work of the Earl’s sisters (Pepys 1983, p. 25).

Figure 7.

Member of Courtenay Family, Cabinet (upper registers), c. 1790s. Rosewood and Parcel-Gilt. In the style of Elward, Marsh and Tatham. Powderham Castle. Credit line: by permission of the Earl of Devon.

Figure 8.

Member of Courtenay Family, Cabinet (lower registers), c. 1790s. Rosewood and Parcel-Gilt. In the style of Elward, Marsh and Tatham. Powderham Castle. Credit line: by permission of the Earl of Devon.

Figure 9.

Member of Courtenay Family, Small Cabinet on Stand, c. 1790s. Rosewood and Parcel-Gilt. Powderham Castle. Credit line: by permission of the Earl of Devon.

Earlier visitors to Powderham claimed that the cabinets had been painted by the 9th Earl. On her visit in May 1799, Anne Rushout recalls in her diary that in the Breakfast Room, “several of the pier tables are painted by Lord Courtney” (Rushout 1799). Her account also dates to the same year as one of the mixed flower paintings signed by the Earl. This suggests that the identity of the artist behind the tables, and possibly also the framed pictures, was shared with guests when they toured the castle. Based on the date of the Rushout account, the cabinets currently at Powderham must have been completed by 1799, putting them within a few years of the execution of the watercolors on paper. It is possible therefore that they were worked on at the time when Craig was drawing master at the house, and during the period when the Earl’s sisters—Caroline, Matilda, Sophia, and Louisa—were still living there. Rushout does not mention the Courtenay sisters as possible artists here, which is striking, as this would have been a likely assumption based on social expectations. Although the Courtenay family tradition recounted in guidebooks and Rushout’s account does not mention the involvement of the Earl’s sisters in the painting of the cabinets, the technique used in their creation allows for the possibility of the siblings’ participation. Unlike the flower paintings, which are by a single hand, these cabinets include separate pieces of floral decoration brought together to form one scheme, raising the possibility of multiple artists. Additionally, the flower pieces inserted into the furniture do not have signatures, further opening up the possibility of their being family endeavors and not the work of a single person.

The marble-topped cabinets are made from rosewood with parcel-gilding along the edges and feet. When the individual elements are examined, there is a sense that the designs were created in different stages from the piece of furniture. The larger of the two cabinets features nine main flower designs and three border motifs (Figure 7 and Figure 8). The placement of the wooden pieces which divide each design raises questions about the process of the cabinet’s creation. It is likely that the Earl and his sisters painted the watercolors, and then the craftsman designed the cabinet accordingly. The larger cabinet is in the style of Elward, Marsh and Tatham, the main furniture suppliers for the Earl in the 1790s to whom payments are listed in the Powderham account books (Anonymous 1781–1795, p. 166).

The second cabinet, also perhaps the work of Elward, Marsh and Tatham, has three main flower watercolors including the central panel depicting a group of roses (Figure 9). Unlike the first cabinet, the sections within the main panels are not divided by wooden borders. Instead, the main floral designs and their borders are separated by lines drawn or traced by the artist. Thus, each panel on this cabinet could have been developed, executed, and placed on the object without adjusting or accounting for the woodwork. Detailed examination of the cabinets demonstrates the diversity and complexity of the elements, revealing the involvement of the multiple hands of the craftsman and the artist (or artists).

The style and formation of the paintings on the cabinets confirm the connection to the Earl but also possibly to his sisters. Throughout the different registers depicting various floral patterns and arrangements, the blue-grey backgrounds match those in the watercolor paintings. The compositions themselves follow the same structuring of colors to be found in the framed watercolors. Take, for example, the lower right register of the larger cabinet (Figure 8) and the mixed flower painting (Figure 6). In the center, there is the standard white flower—roses in each of these cases—with the darker, purple-rimmed auricula below or slightly to the right. Above the roses in both compositions are flowers in warmer colors of yellow and red. Cooler blue flowers are furthest away from the light center, on the outer edges of the arrangements. Such stylistic similarities suggest a certain formulaic approach, at least in the organization of the flowers based on color.

The central lower register of the larger cabinet features a basket containing yellow and blue flowers and white roses placed on a surface that resembles a mantlepiece (Figure 8). Such baskets, together with the vases, were a common feature of eighteenth-century flower presentation. Indeed, there are records of the Earl purchasing such baskets in the 1790s (Anonymous 1781–1795, p. 197). These would have been used both to gather the flowers from the Powderham gardens and to display them in the castle. As Mary Rose Blacker explains, when examining re-creations of eighteenth-century arrangements at Osterley Park, a variety of flowers could be presented in such baskets, typically in a natural manner, with tall and short plants placed together in one container (Blacker 2000, p. 197).

The designs of such baskets can be traced to French decorative arts in which the Earl took an interest. Examples of professionally designed floral imagery for furniture in the French style were available to elite consumers. The Earl did not purchase such items, although he could have been inspired by those he likely knew of, as an elite member of society. Examples of flower baskets with bows that tie at the top, like those on the Powderham cabinet, could be found on cabinets decorated with Sèvres porcelain tiles in the Saloon at Carlton House in London, residence of George, Prince of Wales (1762–1830). The French manufacturing company Sèvres created the ten soft-paste floral plaques included in this piece in the 1780s.12 British artists including George Brookshaw (1751–1823), whose clients included the Prince of Wales, were inspired by French porcelain design, indicating the circulation of floral decorations within artistic networks (Wood 1991, p. 392). The Prince was part of the same artistic circle as the 9th Earl, with both commissioning objects from the furniture manufacturers Elward, Marsh and Tatham, for example (Heard 2019, p. 91). Enthusiasm for these motifs could likely have been transferred to the Earl’s amateur practice through interactions with such fellow collectors, as well as design books. The Prince of Wales’s possession of cabinets with floral ornamentation demonstrates that such objects were socially acceptable for both genders. It was, significantly, specifically the creation of them as a form of amateur artistic leisure activity that was perceived as feminine.

This gendered division can also be seen in the activities of other members of the Royal family. Queen Charlotte acquired Frogmore House in the Home Park at Windsor in 1792 to use as a retreat rather than a residence (Royal Collection 1997, pp. 8–9). While George collected flower furniture, his sister, Princess Elizabeth, painted her own pieces at Frogmore, including a pair of side tables for the Green Pavilion (Roberts 2004, p. 152).13 Compared to the Earl’s floral furniture, both these pieces have a clearer composite design, with less attention paid to the individual details of each flower. The flower garlands painted on the walls of the Cross Gallery at Frogmore by Elizabeth in the 1790s also attest to the interest that both she and her mother had in flower painting and botany (Shteir 1996, p. 37).

4. Celebrating the Powderham Grounds and Gardens

A similarity between the projects at Frogmore and Powderham is the decoration of rooms with motifs of plants and flowers. Bringing painted flowers and greenery into interior spaces celebrated the gardens, parklands, and grounds which surrounded these houses. While the watercolors and cabinets provided interior decoration at Powderham, they also emphasized the Courtenay family’s love of the surrounding gardens and grounds. One of the Earl’s paintings of a bouquet suspended in a shawl, the most elaborate of his works, infers that the stems have come from the painted landscape outside the window (Figure 10). This picture also underscores how these products of nature were made to interact with the man-made environment around them. The bouquet, wrapped in blue patterned fabric, is tied onto a latticed window shutter. The flowers—again a mix of blooms which appear in different months—includes roses, an iris, a tulip, an auricula, jasmine, and a sunflower. There is a shadow under the shawl, suggesting light coming from the outside—the location of the Earl’s other collection: his living plants.

Figure 10.

William Courtenay, 3rd Viscount Courtenay and 9th Earl of Devon, Flowers in a Blue Shawl, c. 1790s. Watercolor on paper, 57 cm × 73 cm. Powderham Castle. Credit line: by permission of the Earl of Devon.

A few of the flowers depicted by the 9th Earl relate directly to plants which he cultivated at Powderham. For example, the main feature of another of the larger watercolors is a magnolia set in the center of an arrangement with a sunflower, poppies, roses, a foxglove, and an iris (Figure 11). The location and size of this magnolia bloom highlights its significance. Originating in the south-eastern part of North America, the magnolia grandiflora, commonly called the bull bay, was introduced to Britain around 1728 (Blacker 2000, p. 239). There is evidence that the Earl grew magnolia trees as part of his American garden at Powderham. In Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum, John Claudius Loudon wrote about a magnolia grandiflora or Southern Magnolia at Powderham in 1854 (Loudon 1854, p. 63). Likewise, a description of the plants in the American garden in the 1882 Gardeners Chronicle states that the “Magnolias grow and flower as freely as the commonest Rhododendron” (Anonymous 1882, p. 590). Rebecca Flemer has rightly pointed out that from this later description, the date of the original planting of the garden is unclear (Flemer 2018, p. 98). However, the life span of a magnolia is long enough for these to have been potentially planted by the Earl.

Figure 11.

William Courtenay, 3rd Viscount Courtenay and 9th Earl of Devon, Still life with flowers in a tall vase, c. 1790s. Watercolor on paper, 98 cm × 71 cm. Powderham Castle. Credit line: by permission of the Earl of Devon.

The majority of the Earl’s flower works on both paper and cabinets are part of the decorative, still-life tradition rather than botanical practice. While botanical studies of individual flowers could be used to sharpen the skills needed to create multi-bloom still lifes, there are notable differences in the two pursuits. Botanical illustrations have their roots in the tradition of the European Herbals that started in the Middle Ages and were intended to capture plants for scientific classification and study. Flower painting focused more on aesthetics and was associated with the genre of still life (Saunders 1995, p. 85). Decorative painters could certainly use botanical drawing for practice or as the basis for larger compositions.

The 1796 watercolor in the Fitzwilliam of a single rose does have characteristics of a botanical drawing (Figure 3). The rose is depicted here in two phases of bloom. The fully blossoming flower on the left shows what the bud on the right would have eventually become if it had not been severed from the plant. The cutting has been necessary for the moment to be captured and the details studied, including the very finely rendered thorns. As is common in botanical works, this composition focuses on a single plant, which is silhouetted against a plain, light background. Roses are featured in all of the Earl’s watercolors, suggesting that this study was most likely an exercise for him to practice their depiction.

Roses were standard in late eighteenth-century floral imagery. The painter Thomas Parkinson stated in his Flower Painting Made Easy of c. 1766 that “the Rose is, and very justly, the Favourite of the Painters; seldom left out in any Composition, where it can be admitted” (Parkinson 1766, p. 5). However, the Earl’s roses have perhaps a more personal meaning, since they were noted by visitors as part of his horticultural pursuits in the gardens at Powderham. In her visit to the grounds in 1800, for example, Elizabeth Ham admired his specimens, stating that:

It is thus interesting that in the Fitzwilliam watercolor, the Earl chose to focus on the details of a flower with more of a botanical or botanist’s approach, which was particularly associated with him and his gardens.It was there I first saw the China or monthly rose growing in the open air. It covered the whole front of a beautiful Pavilion and was in full flower. I thought I had never before seen anything so pretty.(Ham 1945, p. 51)14

Flower watercolors created on a smaller scale such as the single rose painting could be sent to other family members and friends or placed in albums for more intimate viewing. The smaller works by the Earl in the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum are only thirty centimeters in height, compared to the magnolia piece which is ninety-eight centimeters high. Another of these smaller Fitzwilliam examples dating from 1797 depicts blooms in a bundle without a vase (Figure 4). The flowers depicted include two types of irises, magnolia, and different types of leaves. The composition, with groups of flowers against a grey-blue background and grey borders, allows us to connect the work to the framed watercolors at Powderham, especially the 1799 Mixed Flowers which depicts roses, irises, and deutzia crenata (Figure 2). Deutzia crenata is another plant recorded as growing in the American garden at Powderham in the 1882 list (Anonymous 1882, p. 590). An additional watercolor at Powderham has a similar grey border (Figure 12). The flowers depicted here are a mixture of roses and lilies, with the stems extending downwards as in the case of the painting of mixed flowers at the Fitzwilliam. These smaller examples demonstrate the Earl’s ability to commemorate his botanical endeavors on different scales, depending on the intended purpose of the artwork.

Figure 12.

William Courtenay, 3rd Viscount Courtenay and 9th Earl of Devon, An arrangement of roses and lilies, c. 1790s. Watercolor on paper, 22 cm × 18 cm. Powderham Castle. Credit line: by permission of the Earl of Devon.

Since the flowers depicted in the watercolors at Powderham appear to have been from the Earl’s own gardens, they relate to the idea that objects in a collection represent the biography and interest of their owner. Freya Gowrley has explored this idea in her study of the Courtenays’ neighbors, Jane and Mary Parminter, who lived at A la Ronde in Exmouth. The Parminters collected items from the surrounding Devonshire countryside, such as shells, which they then displayed alongside objects in their house brought back from their Grand Tour. Gowrley argues that A la Ronde was a domestic space formed from “the interconnecting and subjective identities of its inhabitants, in which they are simultaneously women, family members, travellers and residents of Devon” (Gowrley 2022, p. 118). The floral still lifes at Powderham likewise speak of the Earl’s identity. They denote him to be a collector of plants, an artist who records his cultivations, and a member of a family which pursues art to express their interests.

5. Courtenay Family Artists

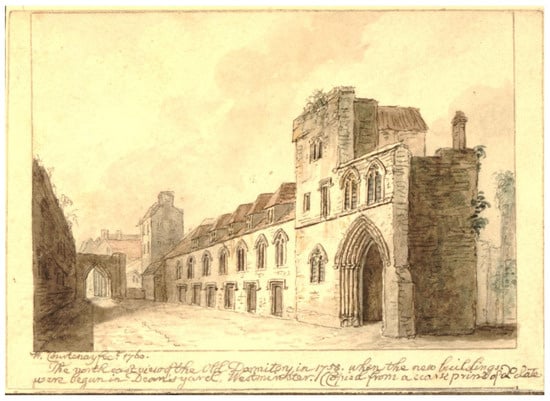

Unlike the 9th Earl, members of the Courtenay family a generation before him followed gendered expectations of amateur art. This meant that male amateurs often engaged with architecture, drawing buildings based on classical and medieval sources. Elite women, conversely, were more likely to record domestic scenes with figures, alongside floral and landscape motifs. William Courtenay, 2nd Viscount Courtenay, the 9th Earl’s father, drew architecture. One of his extant drawings depicts the old dormitories at Westminster School, created when he was a pupil there in 1760 (Figure 13). The image is executed in black and brown ink, with shades of brown wash to create a sense of depth and the shadows of the building. Other than the small quantity of green foliage to the right of the composition, the color scheme is monochrome, and the focus is on the architectural features, such as the window tracery and doorways. Unlike his son’s watercolors, in which line is softened to capture the effects of delicate blooms, the Viscount deploys lines that are well defined and rather hard-edged to underscore the solidity of the building. The dormitory drawing is signed in the same declarative manner as one of the Earl’s watercolors, with “W. Courtenay fecit 1760” written in the lower left margin. As the 2nd Viscount created the Westminster drawing before he inherited his title, the signature includes his first initial. Prints after other drawings by the 2nd Viscount likewise survive, showing the Westminster Abbey and the dormitories.15 The male space of the school and abbey and an understanding of their Gothic forms were clearly deemed proper subject matter for the 2nd Viscount.

Figure 13.

William Courtenay, 2nd Viscount Courtenay, A small view of the northeast of the old Dormitory in Westminster School, 1760. Watercolor, 7 cm × 10 cm. British Museum (1880, 1113.2528). Credit line: © The Trustees of the British Museum, Open Access Policy.

Significantly, while the 2nd Viscount drew architectural subjects, his sister (the 9th Earl’s aunt) Mary Courtenay painted flowers. Examples of their artworks sit alongside each other in the Andover albums at Kenwood House (Sloan 2000, pp. 167–68). These albums were owned by Mary Howard (nee Finch), Viscountess Andover, who was a relative of the Courtenay family.16 Two of the drawings in the albums by the 2nd Viscount depict ships. Since Powderham was situated on the river Exe, the family consistently owned yachts and other craft. The Earl’s father had two large ships: his yacht, the Neptune, and an 80-ton vessel called the Dolphin (Cusack 1996, p. 120). Whilst his son would later paint the flowers he observed and cultivated on the grounds of Powderham, the 2nd Viscount drew the boats that were part of his daily life.

It is important to note that all the flower drawings in these albums were created by women in the Howard–Finch–Courtenay family network. Two of Mary Courtenay’s pieces in the albums depict flowers, including one showing a tulip and rose. She signed and dated these “M Courtenay fecit 1762”. Unlike the majority of her nephew’s flower pieces, Mary displays her selected blooms on a white background in a style more akin to botanical drawings than to still life painting. The artworks of both the 2nd Viscount and Mary demonstrate an artistic legacy in the family that was passed down to the 9th Earl and his sisters, who also participated in various art practices. However, the Earl decided to create flower paintings as his aunt before him rather than architectural and nautical drawings like his father.

6. Flowers and Queerness

While the painting of flower watercolors was seen as feminine and in opposition to subjects associated with men, the reality of gender in the eighteenth century was not, of course, so binary. Men of the “third sex” who displayed effeminate behaviors were associated with hermaphrodites and called “fribbles” (Reeve 2020, p. 140). A number of men associated with this category in the period appreciated art that was typically viewed as a female accomplishment. Horace Walpole, for example, proclaimed that works of embroidery by women revived a form of art older than drawing, arguing that they “maintained a rank amongst the works of genius” (Sloan 2000, p. 215). He thus listed pictures created by women using embroidery as part of his notes on the art of the time of George III (Walpole 1765, pp. 335–36). It is possible that by choosing a feminine form of amateur art to practice, the 9th Earl was engaging with his identity as someone of this “third gender” long before notions of queer identity existed.

Visually, men perceived to be members of the “third sex” could be shown with female gestures and attributes. In some cases, this significantly included bouquets or floral-patterned clothing. In Thomas Holloway’s “Contrasted Attitudes of a Man and a Fribble,” for example, a man of the “third sex” is shown in extravagant dress holding a bunch of flowers (Figure 14). This engraving is in Johann Caspar Lavater’s Essays on Physiognomy (Lavater 1789, vol. 3, p. 213). Matthew Reeve argues that the tall, younger man in the image is the figure of the fribble’s affections, but his slenderness indicates that he is not a member of the “third sex,” given into moral decay. Reeve goes further in identifying the taller man as a representative of the manly classical column of the Doric order; this, as opposed to forms of Gothic architecture associated with members of the “third sex” (Reeve 2020, p. 140). If such stereotyped images can be associated with architectural forms and styles, then it is quite possible that they also represented other art practices or subjects. For members of the Earl’s aristocratic circle familiar with such images and descriptions of the fribble, the connection between the 9th Earl’s interest in flowers, his effeminate behavior, and his social interactions would have been readily evident.

Figure 14.

Thomas Holloway, Contrasted Attitudes of a Man and a Fribble in Essays on Physiognomy by Johann Caspar Lavater. London, 1789, vol. 3, p. 213. Internet Archive.

It is also arguable that the way in which the Earl chose to depict certain flowers—especially the exotic and sensuous magnolia—alludes to their sexual nature. Flowers, love, and sexuality were already associated with one another by the late eighteenth century. There was also a belief in the period that the study of botany would help women to learn about sexual reproduction, while maintaining their spiritual purity and modest sensibility. Discussing the benefits of women using botany to learn about reproduction, Bermingham argues that the subject “had none of the unpleasantness of the dissecting room and raised none of the awkward religious questions that had begun to plague the study of geology” (Bermingham 2000, p. 206). Women did not need to enter male-dominated scientific spaces or question the Christian teaching of the Creation to engage with this science.

The new sexual classification of plants—named the Linnaean system after the Swedish botanist, Carl Linnaeus—made botany accessible to women without formal education in the subject. Linnaeus was the first scientist to classify plants using a two-name system in the 1730s (Hulton and Smith 1979, pp. 137–38). In Britain, the Linnaean system became popular through the work of Erasmus Darwin, who published a two-part poem on the subject in 1791. In the second part, entitled The Loves of the Plants, Darwin uses terms such as “unallow’d desires” when describing plant reproduction. He also includes classifications such as “feminine males” and “masculine ladies” in his translation of Linnaeus’s Latin terms (Darwin 1825, Canto IV, l. 304). The Linnaean system as described by Darwin thus complicated heteronormative systems, as not all flowers were of one gender, and they could reproduce in different ways from humans. Some aristocratic women viewed this botanical study as dangerous. In Viridarium: Coloured Plates of Green House Plants, with the Linnean Names, and with Concise Rules for their Culture (1806), for example, Henrietta Mary Moriarty worried that the Linnaean system could be “dangerous to the young and the ignorant” (Bermingham 2000, p. 207). These were the texts and ideas about the sexuality of plants that were circulating amongst the elite when the Earl created his flower pieces.

Knowledge of the sexual system of plants is present in the Earl’s depiction of the magnolia entirely open, thereby displaying its female reproductive pistil. Magnolias are bisexual flowers, as they have both male and female reproductive features, allowing bees to transfer pollen from stamen to pistil in a single bloom (Figure 11). In the eighteenth century, bisexuality literally referred to having the characteristics of both sexes. This emphasis on the reproductive parts of a bisexual flower in the Earl’s watercolor connects him, furthermore, to another flower artist associated with queerness: Mary Delany (Reeder 2009). According to Lisa Moore, Delany had intimate relationships with women while married to a man. She relates this fact to Delany’s paper collages, which depict flowers that are sometimes bisexual in nature. Delany was following the ideas of Linnaeus, for whom the sexual reproduction of plants was expressive of human sexual variation (Moore 2005, p. 50).

In her discussion of Delany’s Magnolia Gradiflora (1776) in the British Museum, for example, Moore argues that the position of the flower is unique amongst contemporary depictions of magnolia blooms (Figure 15). This is because Delany positions the flower to reveal the pistil, highlighting its similarity to the human clitoris. Other renditions of the magnolia, including examples by French painter Pierre-Joseph Redoute, instead show the flower from the back, therefore hiding the reproductive organs (Moore 2005, p. 63). It could be telling that, unusually, these two individuals (the 9th Earl of Devon and Mary Delany) whose sexual relationships did not fit within expectations of the period chose to depict this flower in positions that displayed its bisexual reproductive parts and to liken them to human sexual organs.

Figure 15.

Mary Delany, Magnolia Grandiflora, 1776. Paper, 33.8 cm × 23.4 cm. British Museum (1897, 0505.557). Credit line: © The Trustees of the British Museum, Open Access Policy.

7. Conclusions

When viewed as a collection, the Earl’s watercolors constitute a queer legacy. He went against the expected duties of an aristocratic gentleman by not marrying and not generating an heir who would continue the family line. He did, however, participate in the Courtenay family legacy of amateur artistic practice. Artworks produced by members of the Courtenay family show amateur art to have been an inheritance that passed through each generation.

Whilst it was common for elite women and men in the late eighteenth century to paint and draw as a sign of their gentility, it is striking that there were two generations of keen sibling creators in the Courtenay family, from the 1760s to the early 1800s. This can also be related to a sense in the period that the subjects of drawings could provide a dialogue with items or people from the past. The printer Carington Bowles (1724–1793) posited that drawing “brings to our remembrance things long past, the deeds of people and nations long since dead, and presents us with the features and resemblances of our ancestors for several generations” (Bowles 1785b, p. 1). The Earl’s father wanted to be remembered for his observations of architecture and ships on the river Exe. The Earl, however, wanted to be remembered for the flowers he cultivated and painted.

Never to produce a legacy in the form of an heir to the estate, the Earl did, however, contribute to the artistic legacy of his family. As Elizabeth Freeman has outlined in Time Binds, queer stories are often described as ones of loss or destruction and not of creation. She notes that “Queers have, it is fair to say, fabricated, confabulated, told fables, and done so fabulously—in fat and thin art, and more—in the face of great pain” (Freeman 2010, p. xxi). While her reference is to twentieth-century queerness, the idea behind this statement can be applied to the Earl’s watercolors as well. In the face of hardship at a young age, the Earl later developed interests that connected him to the female members of his family, both alive and deceased.

The Earl’s floral watercolors, on paper and embedded in furniture, can be considered part of his queer story because, as shown in this article, such work was considered a feminine practice by the end of the eighteenth century. As observed by his contemporaries, the Earl wanted to remain close with his sisters in his adult years. His floral artistic creations at Powderham constituted one way of doing so. They also reflect his interest in cultivating and celebrating his exotic collection of plants on the grounds of his estate. Choosing flowers as his subject, their pre-existing connection to queer sexuality and gender alluded to his own effeminate character. In the end, “flowers and foolery” were not an effeminate waste of time, as Beckford had viewed them. They were rather powerful forms of artistic expression and creation, which formed a key component of the Earl’s queer artistic legacy.

Funding

This research received external funding from a Paul Mellon Centre Research Support Grant (03-2022-RSG/37).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Charles Courtenay, 19th Earl of Devon for allowing access and permission to research the 9th Earl’s watercolors. Thanks to the teams at Powderham Castle, Kenwood House, and the Fitzwilliam Museum, especially Louise Cooling, Katie Cormack, Katie Edwards, Felicity Harper, Amy Marquis, and Derry Tydeman for facilitating viewing of the artworks. My gratitude to Matt Cook, Lynda Nead, and Kate Retford for their feedback on earlier versions of this research. My thanks also go to Freya Gowrley, Kim Sloan, and David Whitfield.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For clarity I will refer to William Courtenay as the 9th Earl or Earl for the remainder of this article though he was not given that title until 1831 (Presswell 2009, p. 51). |

| 2 | The 9th Earl met Beckford when he was eleven and their relationship ended with the publication of their affair in London newspapers during 1784 (Haggerty 1999, pp. 136–51). |

| 3 | Guy Chapman and Terry L. Meyers provide a full account of the working partnership of Henley and Beckford (Chapman 1937, p. 106; Meyers 2012, pp. 347–50). |

| 4 | There have not been an in-depth study of these artworks though they have been mentioned in histories of the country house including Gervase Jackson-Stops’s catalogue of the 1985 exhibition, Treasure Houses of Britain, at the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (Jackson-Stops 1985, p. 19). |

| 5 | Queer theorists and historians of homosexuality, including Randolph Trumbach, have identified the development of a so called “third gender” or “third sex” in the early 1700s. This term applied to adult men who were sexually attracted to other adult men and displayed feminine behaviors (Trumbach 2007, p. 77). Throughout this article I also follow Dominic Janes’s definition of the term queer that states it is used “in the exploration of circumstances in which there is some form of overlap between cultural politics of transgression and the constuction of alternative to normative sexual identities” (Janes 2016, p. 2). |

| 6 | “amateur, n. and adj.”. OED Online. June 2022. Oxford University Press. https://www-oed-com.ezproxy.lib.bbk.ac.uk/view/Entry/6041?redirectedFrom=amateur& (accessed 12 July 2022). |

| 7 | According to an 1803 inventory, during the lifetime of the 9th Earl this room was called the Dining Room and the watercolors were located in a “Dressing Room” on the first floor (Hicks 1803, p. 13). The Dining Room became the White Drawing Room at the beginning of the twentieth century. |

| 8 | See a clear example of this signature in a letter from William Courtenay, 9th Earl of Devon to William Pitt, 22 December 1800. Devon Heritage Centre (Courtenay 1800). |

| 9 | A few of Craig’s paintings of Powderham are currently in the castle but the location of the 9th Earl’s portrait is unknown. |

| 10 | See “Botanical Collages from the Circle of Booth Grey, 1790s”, Yale Center for British Art, https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/orbis:12659132 (accessed 29 February 2022). |

| 11 | See “Flower Piece with Bird’s Nest”, Royal Collection Trust, https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/48/collection/452491/flower-piece-with-birds-nest (accessed 25 May 2023). |

| 12 | See “Martin Carlin”, Royal Collection Trust, https://www.rct.uk/collection/21697/cabinet (accessed 3 March 2022). |

| 13 | See “Side Table, c. 1800”, Royal Collection Trust, https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/4/collection/53107/side-table (accessed 3 March 2022). |

| 14 | The pavilion which Ham mentions was likely in the American Garden created by the Earl (Flemer 2018, p. 75). |

| 15 | After William Courtenay, 2nd Viscount Courtenay, “The South View of the Abbey & Dormitory in Westminster,” British Museum (1880, 1113.2532), https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1880-1113-2532 (accessed 15 November 2022). |

| 16 | Members of the Finch family, including Mary Howard (nee Finch) herself, were prolific amateur artists during the latter part of the eighteenth century. Louisa Finch, wife of Heneage Finch, 4th Earl of Aylesford, produced nearly 3000 flower drawings, inscribed with the Latin name of each plant (N. Riley 2017, p. 289). |

References

- Anonymous. 1781–1795. Cash Book. 1508M/O/E/Accounts/v/15. Exeter: Devon Heritage Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1882. Powderham Castle. Gardeners Chronicle & New Horticulturist 17: 589–90. [Google Scholar]

- Beckford, William. 1784. Letter from William Beckford to Samuel Henley. GEN MSS 102, Box 2. New Haven: Yale Library. [Google Scholar]

- Bermingham, Ann. 2000. Learning to Draw: Studies in the Cultural History of a Polite and Useful Art. London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blacker, Mary Rose. 2000. Flora Domestica: A History of Flower Arranging, 1500–1930. London: National Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, Carington. 1785a. Bowles’s Florist Containing Sixty Plates of Beautiful Flowers. London, printed by author. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, Carington. 1785b. Drawing Book for Ladies; or Complete Florist. London, printed by author. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G. 1803. A New Treatise on Flower Painting, or Every Lady Her Own Drawing Master. London, printed by author. [Google Scholar]

- Brusati, Celeste. 1997. Natural Artifice and Material Values in Dutch Still Life. In Looking at Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art: Realism Reconsidered. Edited by Wayne Franits. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cardwell, William. 1835. An Inventory: The Effects at Powderham Castle. Exeter: Powderham Castle Archive. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, Guy. 1937. Beckford. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Christie, James. 1816. A Catalogue of a Truly Capital and Distinguished Collection of Italian, French, and Dutch Pictures, the Genuine Property of a Nobleman, Lately Brought from His Mansion, Nearly the Whole of Which Have Been Preserved in the Family Untouched for Upwards of the Last Fifty Years. London, printed by author. [Google Scholar]

- Coats, Alice M. 1975. The Treasury of Flowers. London: Phaidon in Association with the Royal Horticultural Society. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay, William. 1800. Letter from William Courtenay, 9th Earl of Devon to William Pitt. 1508M/12/Z/1. Exeter: Devon Heritage Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, William Marshall. 1806. The Complete Instructor in Drawing. London: Charlotte-Street. [Google Scholar]

- Cusack, Janet. 1996. The Rise of Aquatic Recreation and Sport: Yachting and Rowing in England and South Devon, 1640–1914. Ph.D. thesis, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, Erasmus. 1825. The Botanic Garden: A Poem, in Two Parts; Containing the Economy of Vegetation and the Loves of the Plants, with Philosophical Notes. London: Jones and Company. [Google Scholar]

- de Lairesse, Gerard. 1817. Treatise on the Art of Painting in All Its Branches. Edited by William Marshall Craig. London: E. Orme. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Ralph. 1930. Queen Charlotte’s Painter in Water Colours. The Collector XI: 198–201. [Google Scholar]

- Flemer, Rebecca. 2018. The American Garden at Powderham: ‘Delightful Retreat in the Plantation’. Master’s thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, Elizabeth. 2010. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Girouard, Mark. 1963. Powderham Castle—III: The Seat of the Earl of Devon. Country Life 134: 140–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gowrley, Freya. 2022. Domestic Space in Britain, 1750–1840: Materiality, Sociability and Emotion. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Greig, Hannah. 2013. The Beau Monde: Fashionable Society in Georgian London. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty, George. 1999. Men in Love: Masculinity and Sexuality in the Eighteenth Century. New York and Chichester: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, Elizabeth. 1945. Elizabeth Ham by Herself 1783–1820. Introduced and Edited by Eric Gillett. London: Faber & Faber Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Amy. 2012. Siblinghood and Social Relations in Georgian England. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heard, Kate. 2019. George IV, Art and Spectacle. London: Royal Collection Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Heckle, Augustin. 1785. Bowles’s Drawing Book for Ladies, or Complete Florist. London: Carington Bowles. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, William. 1803. An Inventory of the Furniture, Plate, Linen, China, Books, Paintings. L1508M/F/Household/1. Exeter: Devon Heritage Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Hulton, Paul, and Lawrence Smith. 1979. Flowers in Art from East and West. London: British Museum Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Tristram. 2021. The Radical Potter: Josiah Wedgwood and the Transformation of Britain. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, Harford Montgomery. 1970. The Other Love: An Historical and Contemporary Survey of Homosexuality in Britain. London: Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson-Stops, Gervase. 1985. The Treasure Houses of Britain: Five Hundred Years of Private Patronage and Collecting. London and New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Janes, Dominic. 2016. Oscar Wilde Prefigured: Queer Fashioning and British Caricature, 1750–1900. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laird, Mark. 1999. The Flowering of the Landscape Garden: English Pleasure Grounds, 1720–1800. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lavater, Johann Caspar. 1789. Essays on Physiognomy. Translated by Henry Hunter. 3 vols. London: Printed for Murray and Highley. [Google Scholar]

- Loudon, John Claudius. 1854. Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum. London: Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden. [Google Scholar]

- Mallalieu, Huon. 2002. The Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists: Up to 1920. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, Margaret Fairbanks. 1952. Period Flower Arrangement. New York: M. Barrows & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, Terry L. 2012. Samiel Henley’s ‘Dark Beginnings’ in Virginia. Notes and Queries 59: 347–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Lisa. 2005. Queer Gardens: Mary Delany’s Flowers and Friendships. Eighteenth-Century Studies 39: 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, Thomas. 1766. Flower Painting Made Easy Being a Collection of Correct Outlines after Nature. London: Printed for & Sold by Robt Sayer. [Google Scholar]

- Pepys, Paulina. 1983. Powderham Castle. Derby: English Life Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pointon, Marcia. 1997. Strategies for Showing: Women, Possession, and Representation in English Visual Culture, 1665–1800. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Presswell, Dorothy. 2009. The Exiled Earl: William Courtenay—Fact and Fiction. Kingsbridge: Dorothy Presswell. [Google Scholar]

- Reeder, Kohleen. 2009. The ‘paper mosaick’ Practice of Mrs. Delany & Her Circle. In Mrs. Delany & Her Circle. Edited by Mark Laird and Alicia Weisberg-Roberts. London and New Haven: Yale Center for British Art in Association with Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, Matthew. 2020. Gothic Architecture and Sexuality in the Circle of Horace Walpole. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, Robin. 1992. Josiah Wedgwood 1730–1795. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, George. 1813. A New Practical Treatise on The Art of Flower Painting and Drawing with Water Colours, for the Amusement and Instruction of All Young Ladies who have a Taste for Drawing. London, printed by author. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, Noël. 2017. The Accomplished Lady: A History of Genteel Pursuits, c. 1660–1860. Warwickshire: Oblong. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Jane. 2004. George III & Queen Charlotte: Patronage, Collecting and Court Taste. London: Royal Collection Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Academy. 1799. The Exhibition of the Royal Academy MDCCXCIX: The Thirty-First. London: Printed by J. Cooper. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Collection. 1997. Frogmore House and the Royal Mausoleum. London: St. James’s Palace. [Google Scholar]

- Rushout, Anne. 1799. Diary for May 1799. Transcribed by Jon O’Donoghue. 2005. Exeter: Powderham Castle Archive. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, Gill. 1995. Picturing Plants: An Analytical History of Botanical Illustration. London: The Victoria and Albert Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Shteir, Ann. 1996. Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science: Flora’s Daughters and Botany in England, 1760–1860. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, Kim. 1997. Industry from Idleness?: The Rise of the Amateur in the Eighteenth Century. In Prospects for the Nation: Recent Essays in British Landscape, 1750–1880. Edited by Michael Rosenthal, Christiana Payne and Scott Wilcox. New Haven and London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, Kim. 2000. A Noble Art: Amateur Artists and Drawing Masters, c. 1600–1800. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Talley, M. Kirby. 1983. ‘Small, Usuall, and Vulgar Things’: Still-Life Painting in England, 1635–1760. The Volume of the Walpole Society 49: 133–233. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Paul. 1997. Dutch Flower Painting: 1600-1720. London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trumbach, Randolph. 2007. Modern Sodomy: The Origins of Homosexuality, 1700–1800. In A Gay History of Britain: Love and Sex between Men Since the Middle Ages. Edited by Matt Cook. Oxford: Greenwood World Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Walpole, Horace. 1765. Anecdotes of Painting in England, III. London: Printed by Thomas Kirgate. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Lucy. 1991. George Brookshaw, ‘Peintre Ebeniste par Extraordinaire’: The case of the vanishing cabinet-maker: Part 2. Apollo 133: 383–98. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).