Abstract

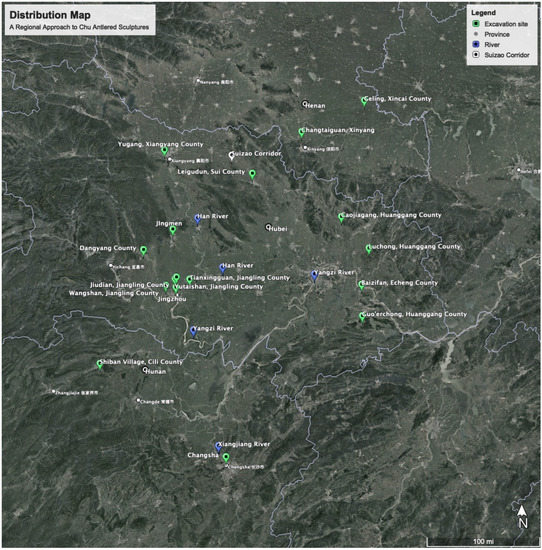

Lacquered wooden sculptures of fantastic hybrid beasts adorned with real deer antlers are among the most extraordinary examples of sculpture found in Chu tombs dated from the sixth through the third centuries BCE. Conventionally known as zhenmushou 镇墓兽 or “protecting tomb beasts”, the antlered sculptures have grotesque features, including bulging eyes, fangs, and protruding tongues. In the fourth century BCE, production and use of these sculptures increased and peaked in the Hanxi region of Hubei province. Although most of these figures have been found in tombs in Hanxi (west of the Han River), distinctive variations of antlered tomb sculptures are also documented in regional areas of the Chu polity, including the Nanyang Basin, the Upper Huai, Eastern Hubei, and Jiangnan. Through a systematic regional analysis of Chu antlered sculptures, this paper presents a spatial framework for analyzing this unique genre of Chu funerary sculpture. This approach provides fresh insight into the interregional networks of interaction across the Chu state and beyond, via waterways and the Suizao corridor from the sixth through the third centuries BCE.

1. Introduction

After the collapse of the Zhou ruling house in 771 BCE and the move of the Zhou capital near Xi’an in modern-day Shaanxi to Luoyang in modern-day Henan, dozens of independent polities arose across the landscape of ancient China. In this age of political intrigue and internecine warfare in which independent courts vied for hegemony over China, known as the Eastern Zhou dynasty (771–256 BCE), both intellectual thought and the arts blossomed. Art production, no longer centered on the Zhou court, took place at independent courts. By the sixth century BCE, one of the most important artistic centers could be found in the state of Chu, the largest and most powerful kingdom in the regional south. The Chu kingdom spread across modern-day Henan, Hubei, Hunan, and Anhui from south of the Yellow River to south of the Yangzi. Although elements of Chu art are derived from earlier Shang (ca. 1600–1046 BCE) and Western Zhou (ca. 1046–771 BCE) artistic traditions, it can be described as an amalgam of the many regional cultures that comprised the vast state. Chu art is diverse, imaginative, and innovative. This is especially evident in Chu animal art. Objects excavated from Chu tombs reveal that Chu had a special affinity for zoomorphic imagery, especially images of fantastic hybrid creatures, which appear in a variety of media, including bronze, wood, lacquer, and clay. Among the most extraordinary examples of hybrid animal imagery found in Chu tombs are wooden sculptures of long tongued hybrid beasts painted with lacquer and adorned with real deer antlers. These sculptures, conventionally known as zhenmushou1 镇墓兽 or “protecting tomb beasts”, are the focus of this paper.2

Herein, I analyze Chu antlered and tongued sculptures using a regional approach. This approach provides a new spatial framework for analyzing these sculptures and provides insight into the interregional networks of interaction across the Chu realm via waterways and the Suizao corridor. To date, over 300 sculptures of antlered hybrid creatures made of wood have been excavated from Chu tombs dated from the sixth through the third centuries BCE in Hubei, Henan, and Hunan provinces (Chaffin 2007; Ding 2012). I begin with the emergence of the earliest examples in the Hanxi (west of the Han River) region of Hubei province in the sixth century BCE, the same time a distinct Chu culture emerges in the archaeological record (Xu 1999, p. 21). In the Hanxi region, we can trace the development of these sculptures from the sixth through the fourth centuries BCE, when a mature style, which I refer to as the “Hanxi style,” emerged (Chaffin 2021, pp. 97–105).3 Although most antlered and tongued hybrid sculptures excavated to date have been discovered in tombs in the Hanxi region,4 Chu tombs to the north of Hanxi in the Nanyang Basin and the Upper Huai, to the east in Eastern Hubei, and as far south as Jiangnan have also yielded distinctive variations of these sculptures.5 By the third century BCE, the use of antlered and tongued sculptures declined as the Chu polity weakened and was eventually conquered by the northern state of Qin, which unified the Warring states in 221 BCE.

2. Hanxi

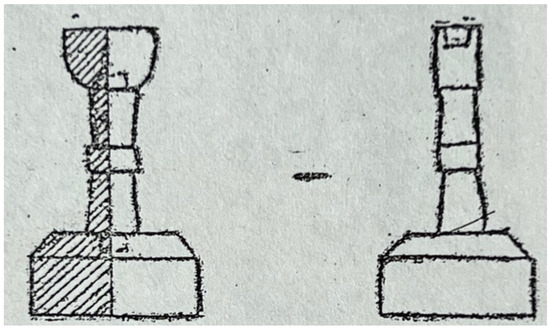

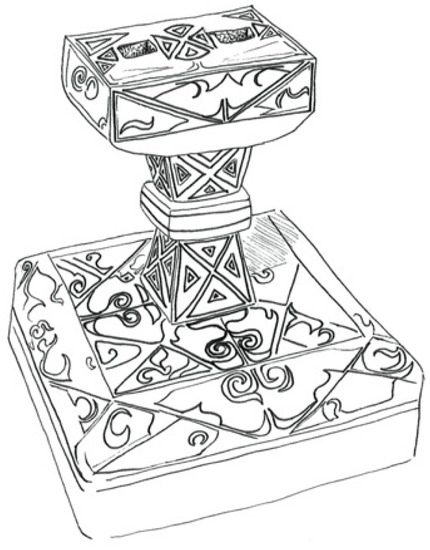

The earliest examples of antlered sculptures carved out of wood date from the late sixth through the early fifth centuries BCE during the Springs and Autumns period (771–453 BCE) and were excavated from Tombs 4 and 6 at Longwan, Xiaohuangjiatai, in Qianjiang County, Hubei (see Appendix A).6 One was excavated from Tomb 4 and two were excavated from Tomb 6 (Qianjiang bowuguan 1988).7 Antlered tomb sculptures dated to this period vary slightly in typology, and lack the zoomorphic facial features, such as the carved eyes, snouts, fangs, and long tongues that appear, characteristically, on the mature form of these sculptures. They are constructed of a series of parts using mortise and tenon joinery,8 including a straight body with a slightly angled neck and truncated round or oval head, a square or truncated pyramidal base, and real deer antlers. Moreover, some early examples include a square collar located at the midsection of the body, such as the example in Figure 1 excavated from Tomb 6 at Xiaohuangjiatai in Longwan, Qianjiang County.

Figure 1.

Front and side views of lacquered wood antlered tomb sculpture excavated from Tomb 6 at Xiaohuangjiatai, Qianjiang County, Hubei Province. Note the sockets for deer antlers in the side view. From Qianjiang bowuguan (1988, p. 39, fig. 7.10).

The Springs and Autumns period sculptures excavated at Xiaohuangjiatai were found in tombs belonging to members of the lower aristocracy.9 Tomb 4 contained a single-chambered wooden burial structure with a wooden coffin and space at the head end of the coffin for burial goods, while Tomb 6 was a larger paired burial consisting of a wooden burial structure divided into two side-by-side chambers (see Qianjiang bowuguan 1988, p. 35, figs. 3 and 36, fig. 4). In each of these tombs, an antlered sculpture was positioned in the space at the head end of the wooden burial structure near the coffin. As a paired burial, Tomb 6 had two antlered sculptures, one at the head end of each coffin. Other offerings, such as pottery vessels and lacquered wooden items, were also placed in this location, as well as along the side of the coffin at the head end.

As evidenced by sculptures discovered in tombs excavated in Dangyang County, Hubei (see Appendix A), minor changes to the form of antlered sculptures were made in the Hanxi region between the early and middle fifth century BCE. The main modification at this time was to the shape of the base, which became a square one carved into a pattern of raised and sunken sections.10 From the late fifth through the early fourth centuries BCE, the mature style (the Hanxi style) began to take form with modifications to the shape of the body and head of Dangyang sculptures.11 The head was enlarged and assumed a more square shape with carved facial features, including roundels at the brow, round eyes, a nose, fangs, and a protruding tongue. The neck was accentuated even further, taking on a serpentine C-form. Moreover, two square collars on the body became standard, with one located below the curved neck and the other forming a tenon shoulder where the body joins the carved square base.

One of the earliest instances of the mature Hanxi style is a sculpture excavated from Tomb 230 at Jinjiashan in Dangyang (see Hubei sheng Yichang diqu bowuguan and Beijing daxue kaogu xi 1992, p. 157, fig. 114.4). Tomb 230 belonged to a member of the lower aristocracy and contained a wooden burial structure and coffin. As with the Springs and Autumns period tombs excavated at Xiaohuangjiatai, Qianjiang County discussed above, burial offerings, including the antlered tomb sculpture, were placed at the head end of the tomb (Hubei sheng Yichang diqu bowuguan and Beijing daxue kaogu xi 1992, p. 58, fig. 39).

Although the earliest examples of antlered sculptures made of wood were discovered in tombs in Dangyang and Qianjiang counties, most documented examples have been excavated from tombs in Jiangling County, Hubei province. Hundreds of tombs excavated near Jinancheng, an ancient walled settlement site, yielded antlered figures related to those found in Dangyang and Qianjiang counties.12 The largest number of antlered sculptures excavated at any Chu mortuary complex to date have been found in tombs at Yutaishan and Jiudian (see Appendix A).13

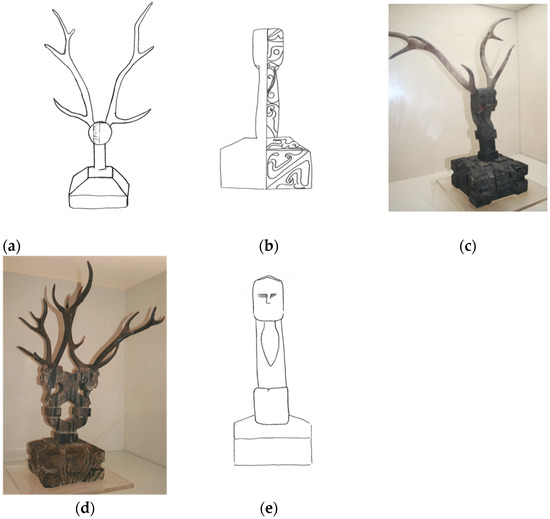

Antlered sculptures excavated from tombs in Jiangling County range in typology from stands for antlers,14 to single-headed hybrid beasts with long tongues; addorsed long tongued hybrids; and long tongued human-headed sculptures (Figure 2a–e). The earliest antlered sculptures found in tombs in Jiangling resemble the late sixth through the early fifth centuries BCE sculptures discovered in Qianjiang County discussed above, including the absence of apparent facial features, but they date somewhat later to the late fifth century BCE (Figure 2a).15 The next type, single-headed antlered hybrid sculptures with facial features (round eyes, snout, fangs, and tongue), can be divided into two subtypes: Those with painted facial features (Figure 2b) and those with carved facial features (Figure 2c). The former subtype has a curved neck and straight body fitted into a truncated smooth base. The latter subtype represents the mature Hanxi style characterized by its C-shaped neck, square body collars, and square base with geometric carvings. Hanxi style sculptures flourished and peaked in the Hanxi region in the fourth century BCE and represent more than half of known excavated examples in Jiangling.16 Addorsed versions, which appeared around the fourth century BCE and are generally only found in tombs belonging to the upper aristocracy, resemble singled-headed Hanxi style sculptures but have twin bodies and heads that rise from the same mortise at the center of the carved base (Figure 2d).17 Long tongued, human-headed sculptures are the rarest type; only one has been discovered in Jiangling County to date, excavated from Tomb 555 at Yutaishan dated to the third century BCE (Figure 2e).18 The sculpture has carved facial features reminiscent of wooden tomb figurines, but paired with a long tongue and crowned with real deer antlers. The body of the sculpture is straight and is fitted into a plain square plinth.

Figure 2.

Five typologies of lacquered wood antlered sculptures excavated in Jiangling County, Hubei. (a) Line drawing of antler stand excavated from Tomb 142 at Yutaishan. Adapted from Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan (1982, plate 67.1) courtesy of Zay Olsen. (b) Line drawing of antlered tomb sculpture with painted features excavated from Tomb 516 at Yutaishan. Antlers are not shown. Adapted from Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan (1982, plate 67.2) courtesy of Zay Olsen. (c) Single-headed antlered and tongued sculpture with carved features (mature Hanxi style) in the Jingzhou Museum. Photo by author. (d) Addorsed antlered and tongued sculpture with carved features in the Jingzhou Museum. Photo by author. (e) Line drawing of anthropomorphic antlered and tongued sculpture. Antlers are not shown. Adapted from Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan (1982, plate 68.3) courtesy of Zay Olsen.

As with the examples found in Dangyang and Qianjiang counties, antlered sculptures in Jiangling County were interred in tombs belonging to both high-ranking and low-ranking aristocrats. The majority of tombs excavated in Jiangling belong to lower ranking aristocrats and have wooden burial structures that are divided by wooden partitions into up to three compartments, including a main compartment for the interment of the deceased in a wooden coffin, and a head compartment and/or side compartment to house burial goods. Larger Chu burial structures in Jiangling have up to seven compartments, with the main chamber typically located at the center of the structure and compartments for burial goods at the sides. Although there are exceptions, such as the anthropomorphic antlered sculpture excavated from Tomb 555 at Yutaishan that was interred in a side compartment of the tomb, antlered sculptures in Jiangling tombs, such as other sites in the Hanxi region, are almost always found at the head end or in the head compartment of tombs (Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan 1984, p. 108).19

During the fourth century BCE, a general formula seems to have determined the decorative program on the surface of Hanxi style sculptures excavated in Jiangling. For instance, the painting on a sculpture from Tomb 264 at Yutaishan (see Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan 1984, p. 110, fig. 88.2) is related to the decoration on an addorsed antlered sculpture from Tomb 1 at Tianxingguan (Figure 3). Although there is a discrepancy between the status of the two tombs, as the former belonged to a low-ranking aristocrat and the latter belonged to a high-ranking aristocrat, and between the sizes of the sculptures, the decoration on the two sculptures is nearly identical.20 The necks of both figures are adorned with S-shaped profile dragons with protruding tongues, and the bodies and most of the bases are covered with the same S-shaped spirals and non-representational curvilinear patterns, also known as the scroll and axe pattern. Furthermore, the collars on the bodies of the sculpture and the lower central panels of the bases are embellished with the same angular zigzag pattern.21 A twin-headed sculpture from Tomb 1 at Wangshan (see Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 1996, p. 96, fig. 67) features a similar program of decoration, but the figure lacks representational decoration; namely, the S-shaped dragons on the neck.22 In place of dragons, which instead appear on the front side of the lower body of the Wangshan sculpture, the neck of the figure is embellished with S-shaped forms that mirror the shape of the profile dragons. In general, figures that lack the dragon motif often feature abstract S-shaped forms on the neck and body and those that lack the angular zigzag motif on the collars are instead embellished with angular or curvilinear volutes.

Figure 3.

Line drawing of addorsed antlered and tongued tomb sculpture made from lacquered wood and excavated from Tomb 1 at Tianxingguan, Jiangling County, Hubei Province. From Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan (1982, p. 104, fig. 28).

The vocabulary of painted motifs seen on the surface of Hanxi style antlered and tongued sculptures is not unique to the sculptures. The profile dragons and angular zigzag patterns are derived from bronze and textile designs, respectively, while the curvilinear scroll and axe forms originated from lacquer painting. The intersection of bronze, textile, and lacquer decorative styles during the Warring States period has long been acknowledged. Colin Mackenzie has emphasized the important role textile patterns played in the development of Warring States period decoration (Mackenzie 1999, pp. 82–91). For example, a textile from a fourth century BCE tomb at Mashan, in Jiangling County, features an angular zigzag pattern related to the pattern that appears on the collars and the lower rectangular panels of the carved base of Hanxi style antlered and tongued sculptures (Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan 1985, p. 43, fig. 35). This motif, which originated from textiles, appeared on a variety of objects during the Warring States period, including bamboo basketry, furniture, tableware, and armor. In Tomb 1 at Tianxingguan, which yielded the tall addorsed antlered and tongued sculpture mentioned above (Figure 3), the pattern decorates the lacquered wood rim of a drum, as well as door motifs on the walls of the four chambers (see Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan 1982, p. 98, figs. 7, 21, and 77). In addition to the antlered and tongued tomb sculptures and the painted doors in the Tianxingguan tomb, the angular zigzag motif most often appears on items made for personal use.

The curvilinear scroll and axe patterns comprising the decoration on the lower bodies of Hanxi style sculptures, as well as the carved panels of the base, were drawn directly from the fluid designs of contemporary lacquer painting. Moreover, curvilinear patterns were popular in embroidered textiles. Mackenzie (1999, p. 90) has shown that an interest in juxtaposing curvilinear and rectilinear designs; namely, placing curvilinear forms over an angular background on a singular object, did not take hold until the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE). The use of both types of patterns on Hanxi style antlered and tongued sculptures shows an interest in combining the two different patterns on one object for aesthetic appeal as early as the fourth century BCE.

The S-shaped dragons painted on the necks of Hanxi style sculptures were derived from two-dimensional images of dragons or felines inlaid into the surface of bronzes in colorful metals. Metal inlay was a technological innovation of the late Springs and Autumns period that continued to be popular throughout the Warring States period (So 1995, p. 25). An early example of inlay can be seen in two lidded cups, one elliptical and one round from Tomb 2 at Xiasi, which is dated to the second quarter of the sixth century BCE (see Henan sheng wenwu yanjiusuo et al. 1991, plate 56: 1–2). The vessels have copper inlaid dragons or felines that wrap around the circumference in two bands: One around the belly and one around the rim of the lid. The creatures alternate between forward and rear facing, with the latter serving as the cast-inlaid copper antecedents of the painted dragons on the Hanxi style antlered tomb sculptures.

Although the vocabulary of motifs seen on Hanxi style antlered sculptures excavated in Jiangling County is fairly consistent, the sculptures vary in size depending on the status of the tomb occupant. In large upper class aristocratic tombs, antlered sculptures are impressive in height. The addorsed antlered hybrid sculpture from Tomb 1 at Tianxingguan measures 5.57 feet tall (Figure 3), and one from Tomb 2 at Tianxingguan measures 4.39 feet tall (Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan 1982, p. 105; Hubei sheng Jingzhou bowuguan 2003, p. 187). Twenty-point racks augment the imposing quality of these sculptures and reflect the status of the tomb occupant.23 Sculptures found in medium-sized tombs with one to three burial compartments and belonging to occupants of lower status typically measure around 3 feet tall and have smaller racks. For example, the Hanxi style single-headed antlered sculpture from Tomb 264 at Yutaishan measures 3.46 feet tall and has, by comparison, a modest eight-point rack (Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan 1984, p. 108).24

Other sites in the Hanxi region yielded antlered sculptures related to those found in Jiangling. Tomb 1 at Baoshan, in Jingmen (see Appendix A), dated to the fourth century BCE and believed to belong to a high-ranking Chu court officer’s wife (Hubei sheng Jingsha tielu kaogu dui 1991, pp. 8–44), yielded a sculpture that does not significantly deviate from Hanxi style sculptures with carved features and bases excavated in Jiangling (see Hubei sheng Jingsha tielu kaogu dui 1991, p. 42, fig. 26). Moreover, the painted decoration is reminiscent of the Hanxi style sculptures excavated in Jiangling. Curvilinear S-shaped forms embellish the neck of the figure, volutes decorate the body and base, and the popular angular zigzag pattern decorates the two collars on the body of the sculpture. As with the majority of finds elsewhere in the Hanxi region, the Baoshan antlered sculpture was placed in the head compartment of the tomb.

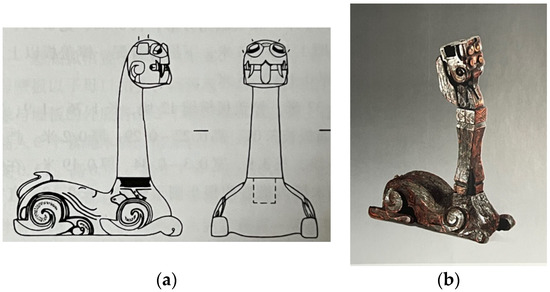

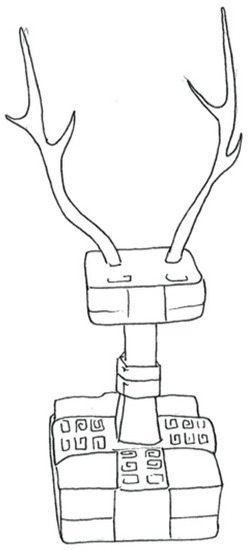

Excavations in Jingmen (see Appendix A) have revealed that the inclusion of antlered sculptures in tomb inventories was not limited to the upper and lower aristocracy. Four tombs dated from the fourth through the third centuries BCE excavated at Luopogang and Zilinggang and believed to belong to commoners also yielded antlered sculptures. Antlered sculptures excavated in regional centers across the Chu realm reflect the status of the tomb occupant through size and quality, and in some cases by the materials used to craft the sculpture. The majority of known examples of antlered sculptures are carved from wood and painted with lacquer, but those discovered in Tombs 30, 87, and 93 at Luopogang and Tomb 19 at Zilinggang were modeled from clay or clay and wood (Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Jingmen shi bowuguan 1996; Jingmen shi bowuguan 2008). The Luopogang sculptures were crafted from clay and wood, with the head and body made of clay and the base and the antlers possibly carved out of wood (Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Jingmen shi bowuguan 1996, p. 94).25 A terra cotta sculpture excavated from Tomb 19 at Zilinggang (Jingmen shi bowuguan 2008, p. 83, fig. 86) was assembled using three components similar to the carved wood antlered sculptures found at other sites: A head and body, base, and imitation antlers (Figure 4). The sculptures discovered at these two sites resemble Hanxi style figures excavated in late fifth through the early fourth centuries BCE tombs in Dangyang, Jiangling, and Jingmen. The figures have round eyes, protruding tongues, and roundels at the brow. Moreover, they have square collars around the neck, modeled in imitation of carved wood. However, the clay versions have three collars rather than two, one at the joint between the head and the body, and two at nearly equidistant intervals below. Holes at the top of the head allow for the insertion of modeled clay, carved wood or real antlers. An opening between the frontal face of the figure and the back of the head is unusual but may have been utilized to give the impression of the curved neck seen on the Hanxi style figures (see Jingmen shi bowuguan 2008, p. 83, fig. 86).

Figure 4.

Line drawing of terra cotta antlered and tongued tomb sculpture excavated from Tomb 19 at Zilinggang, Jingmen, Hubei Province. Adapted from Jingmen shi bowuguan (2008, plate 25.6) courtesy of Zay Olsen.

As with the antlered sculptures made of lacquered wood found in medium-sized tombs elsewhere in the Hanxi region, the ceramic sculptures from Luopogang and Zilinggang were buried at the head end of their respective tombs. The tombs at Luopogang and Zilinggang were poorly preserved, but at least two of the tombs that contained clay examples of antlered sculptures also contained wooden burial structures. Tomb 87 at Luopogang had a wooden burial structure divided into two compartments, a main compartment for the burial of the tomb occupant and a head compartment for burial objects, while the burial structure in Tomb 93 was more modest with a single chamber (Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Jingmen shi bowuguan 1996, p. 202, fig. 106 and 204, fig. 108). Tomb 30 at Luopogang was a rectangular pit tomb with an ercengtai 二层台 ledge around three sides (Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Jingmen shi bowuguan 1996, pp. 139–40). The remaining burial offerings that did not deteriorate over time were clustered at one end of the tomb. Unfortunately, the original structure of Tomb 19 at Zilingang could not be determined and the writers of the archaeological report do not indicate where in the tomb the sculpture was found (Jingmen shi bowuguan 2008, pp. 82, 238). Hopefully, future excavations of commoner graves will reveal how widespread pottery versions of antlered sculptures were. To date, they seem to have been reserved for those who could afford more than a simple earthen pit burial. Although a bronze knife was discovered in Tomb 30 at Luopogang, the tomb occupants at these sites were mainly supplied with a small arrangement of pottery objects for the afterlife, indicative of their low status.

3. The Nanyang Basin

To the north of sites in the Hanxi region, several examples of antlered sculptures made of lacquered wood and dated from the fifth through the fourth centuries BCE have been excavated from Chu tombs at Yugang, in Xiangyang County, Hubei Province (see Appendix A). Since 1987, over 300 Chu tombs have been excavated at the site (Xiangyang shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 2011a, 2011b). The antlered sculptures unearthed from the tombs are few in comparison to the overall number of tombs excavated, but they give us important insight into the network of cultural exchange between the people living in the Nanyang Basin (north of the Han River) and those living to the west and east of the Han River (Hanxi and Handong regions) from the fifth through the fourth centuries BCE.26 The Yugang antlered sculptures represent a unique combination of local and regional styles. As with finds in the Hanxi region, the sculptures were found at the head end of medium-sized tombs supplied with wooden burial structures, coffins, and up to three burial compartments. Three types of antlered sculptures were discovered, including sculptures with abstract and/or geometric painted decoration, sculptures of zoomorphic creatures with carved features and fitted into square-shaped plinths, and sculptures of hybrid beasts with crouching tiger-shaped bases. The former includes sculptures that are similar in typology to the earliest antlered figures unearthed in the Hanxi region, which lack carved facial features, and have round or oval faces with a flat profile and straight or slightly curved bodies. The figures that retain painted decoration feature curvilinear patterns and/or triangular spirals on the body and the base. Moreover, a painted sculpture from Tomb 124 (Figure 5a) features abstract decoration on the face, while an example from Tomb 101 has painted facial features that might be interpreted as eyes (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

(a) Lacquered wood antlered sculpture from Tomb 124; (b) lacquered wood antlered sculpture from Tomb 101. Both excavated at Yugang, Xiangyang, Hubei. Note the sockets for antlers. From Xiangyang shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (2011b, color plates 45.3 and 45.4).

Another sculpture with a square base but of slightly different typology highlights the transmission of artistic styles between the Nanyang Basin and Handong (east of the Han River), especially regarding the design of three-dimensional antlered hybrid creatures. Excavated from Tomb 134 dated to the late fifth century BCE, the sculpture has a round head and a slightly curved neck terminated in a square collar that functions as a tenon shoulder (Figure 6). Its almond-shaped eyes, carved in intaglio, contrast with the round raised eyes of Hanxi style figures. The eyes are carved toward the top of the beast’s round head, giving the figure a less ferocious appearance than the Hanxi style figures with frontal visage. Moreover, a pointed upturned nose and a short tongue set this figure apart. This is the only example excavated in Yugang that retained its original deer antlers. The antlers are painted at the tines and the branching points, such as those found in the Hanxi region, but the figure’s body is painted with vertical bands of S-shaped spirals bordered by narrow bands of concentric circles. The base features units of triangular spirals, which seem to have been a favored motif for Yugang artisans.

Figure 6.

Antlered and tongued sculpture from Tomb 134 at Yugang, Xiangyang County, Hubei. From Xiangyang shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (2011b, color plate 45.2).

The typology of the sculpture from Tomb 134 is related to contemporary objects found in the fifth century BCE tomb of the Marquis Yi of Zeng, excavated near Leigudun, Sui County (see Appendix A) in the Handong region of northeastern Hubei in 1978 (for the full tomb report see Hubei sheng bowuguan 1989). Three-dimensional animal-shaped appendages on bronze vessels found in the Marquis’ tomb feature the same round head, almond-shaped eyes, upturned snout, and smooth curved neck as the Yugang figure (Figure 7a). The round head of the bronze crane-like sculpture adorned with bronze deer antlers and discovered in the main coffin chamber of Marquis Yi’s tomb also resembles the Yugang sculpture, but the antlers emerge laterally from the round head rather than from the crown (Figure 7b). The bronze animal appendages and the crane have heretofore been considered distinctly Zeng in style, although many of the bronze vessels found in the tomb are derived from a Chu prototype (Yang 1999, p. 277). The comparison between the Yugang figure and the bronze sculptural images of fantastical animals found on bronzes in the Marquis Yi’s tomb provides yet another example of artistic and cultural exchange between the two regions, in this case, via the Suizao corridor (see Appendix A).27

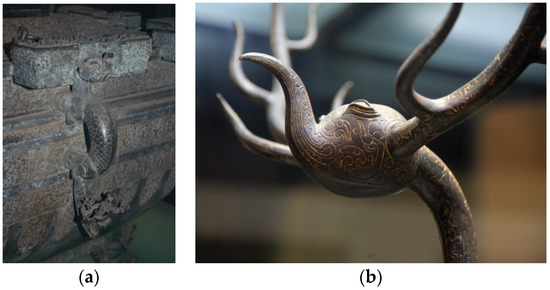

Figure 7.

(a) Detail of bronze jian fou excavated from the Tomb of the Marquis Yi of Zeng. Hubei Provincial Museum. Photo by author. (b) Detail of head of bronze crane excavated from the Tomb of the Marquis Yi of Zeng. Hubei Provincial Museum. Photo courtesy of Larry F. Ball.

The third type of sculpture unearthed at Yugang has a distinctive base carved in the shape of a recumbent tiger’s body. Five sculptures of this type were discovered in tombs dated to the fourth century BCE, slightly later than the Yugang figures with square bases. Two sculptures with long, smooth necks that rise from a crouching feline below represent a local style. The long-necked figure from Tomb 143 (Figure 8a) has a round head with carved features, including a short protruding tongue, and an upturned nose similar in style to the sculpture from Tomb 134 (Figure 6).28 The others have heads and bodies modeled after Hanxi style sculptures (Figure 8b). This indicates that the popular Hanxi style models discovered in Chu territory to the south of Yugang were known in the Nanyang Basin. The Hanxi style was likely transmitted to this northern region of the Chu state via the Han River. In this case, the Hanxi style was reinterpreted to suit local tastes by fitting a Hanxi style body and head into a feline-shaped base rather than into a square one.29 The use of the feline-shaped base appears to be a clever innovation but is probably inspired by the lacquered wooden sculptures of birds perched on crouching tigers found primarily in the Hanxi region (As an example, see Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan 1984, p. 112, fig. 90).

Figure 8.

(a) Line drawing of lacquered wood antlered and tongued sculpture from Tomb 143 at Yugang, Xiangyang County, Hubei. From Xiangyang shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (2011a, 219 fig. 195.16). (b) Lacquered wood antlered and tongued sculpture from Tomb 145 at Yugang, Xiangyang County, Hubei. From Xiangyang shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (2011b, color plate 46.1). Both sculptures were originally equipped with deer antlers.

Where decoration is concerned, the Yugang sculptures mainly feature curvilinear forms and triangular spirals. The abstract curvilinear forms painted on the necks and bodies of the figures with feline-shaped bases are related to designs seen on the Hanxi style antlered sculptures. However, the square collars decorating the Yugang sculptures are embellished with triangular spirals in place of the typical angular zigzag pattern. On a sculpture from Tomb 112, geometric spirals also decorate the body (Xiangyang shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 2011a, p. 134, fig. 100). As mentioned above, this motif seems to have been favored by Yugang artisans. Furthermore, it may corroborate artistic transmission between Nanyang and the Suizao corridor, as lacquered wooden objects in the tomb of the Marquis Yi of Zeng also feature this motif (for example, see Hubei sheng bowuguan 1989, fig. 79).

4. Eastern Hubei

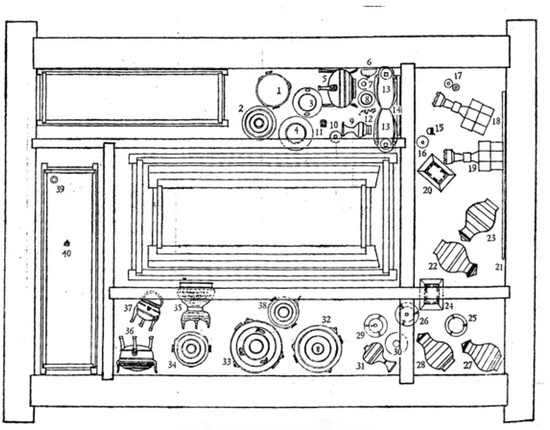

Beyond Hanxi and the Nanyang Basin, variations on the antlered tomb beast have also been excavated at tomb sites along the Yangzi River in Echeng and Huanggang counties in Eastern Hubei (see Appendix A). The typology of the earliest antlered sculpture found in this region, dated to the fourth century BCE, may have been inspired by a Hanxi prototype, but slightly later examples are more unique. The earliest were excavated from the large aristocratic Tombs 3 and 5 at Baizifan in Echeng County (Hubei sheng Echeng xian bowuguan 1983, pp. 223–54). Divided into a series of six compartments with the main coffin chamber at the center, the plans of the tombs are similar to large tombs in the Chu heartland. However, the head compartment of Tomb 5 (Figure 9) yielded two sculptures rather than only one, showing a departure from common practices in Hanxi and the Nanyang Basin (Hubei sheng Echeng xian bowuguan 1983, p. 226, fig. 4).30 Situated on square plinths carved into square sections, the bodies of the Baizifan sculptures are composed of two truncated pyramids, one inverted over the other. They are joined at the waist with a square collar reminiscent of those on contemporary Hanxi style sculptures. The heads of the figures mimic the shape of the collar on the bodies and lack carved facial features, including the characteristic long tongue. Unfortunately, the writers of the original tomb report do not indicate whether the Baizifan sculptures originally had mortises for deer antlers; however, based on the typology of the sculptures and their location in the tomb, they are likely related to antlered sculptures found in Hanxi and Nanyang.31

Figure 9.

Line drawing of Tomb 5 at Baizifan showing two sculptures in the head compartment of the tomb. From Hubei sheng Echeng xian bowuguan (1983, p. 226, fig. 4).

Three sculptures dated slightly later than the Baizifan sculptures from the late fourth through the early third centuries BCE and unearthed from medium and large tombs in Huanggang County are quite unusual in comparison to the Hanxi models and reflect more tenuous cultural ties with the Chu heartland.32 The head compartment of Tomb 1 at Luchong, a large tomb dated to the late fourth century BCE, only yielded fragments of an antlered sculpture (see Huanggang shi bowuguan 1999, p. 245, fig. 29.6), but the archaeologists were able to determine that the sculpture was supplied with wooden antlers rather than real ones (Huanggang shi bowuguan 1999, p. 246). Another poorly preserved, but distinctive example of similar date was unearthed from Tomb 1 at Guo’erchong (see Huangzhou gumu fajue dui 1999, p. 193, fig. 12.3-4).33 Found in an area to the side of the coffin, rather than at its head, this wooden sculpture has a squat oval head, reminiscent of a turtle or a snake, with a pair of beady eyes and a slight mouth. The figure lacks the characteristic tongue motif, and rather than a curved neck and a post-like body, the beast has a smooth, narrow neck that leads into a straight body decorated with a scale pattern.34 Holes were carved into the head, presumably for the insertion of antlers or horns, although none were found in the tomb. Perhaps artisans in this region had a predilection for wooden antlers. The turtle-like bust is fitted into a disproportionately large and square carved base, which is painted with scroll patterns confined in nine square and rectangular units. An antlered sculpture with a similar carved base was found in the head end of Tomb 5 nearby at Caojiagang in Huanggang (see Huanggang shi bowuguan 1999, p. 233, fig. 20.3). Future excavations may show that this type of base was standard for this region. However, the Caojiagang beast has a unique feline-shaped head and a curved neck. The upright pointed ears and protruding tongue that droop naturalistically off to one side are also unusual in comparison to Hanxi prototypes.

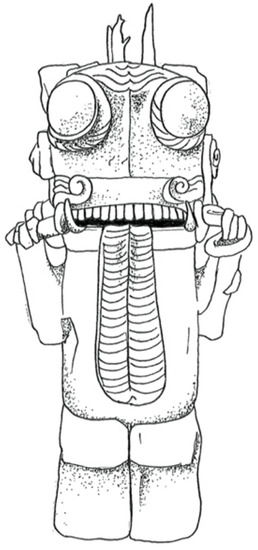

5. The Upper Huai

To the north of sites in Eastern Hubei and east of the tombs at Yugang in Nanyang, large aristocratic tombs excavated at Changtaiguan in Xinyang, Henan province (see Appendix A) dated to the early fourth century BCE yielded some of the most graphic examples of antlered tomb sculptures discovered to date (for the full excavation report see Henan sheng wenwu yanjiusuo 1986). The Changtaiguan tombs were equipped with wooden burial structures oriented roughly east-west and divided into seven to eight compartments. Tomb 1 had a central main coffin chamber with a large head compartment in the east, three rear compartments in the west, and two side compartments in the north and south. Tomb 2 had a central coffin chamber with two head compartments, three rear, and two side. The best preserved of the antlered tomb sculptures was excavated from Tomb 1 and measures a little over 4 feet tall (Figure 10). The sculpture, carved from one piece of wood, is in the form of a kneeling feline with antlers on its head and ears tucked back in agitation. It grasps a snake in its clawed forelegs and between its rapacious fanged teeth. The Changtaiguan sculpture shares the same basic facial features with antlered sculptures found in other regions of the Chu polity, but the features are far more exaggerated and detailed. The enormous eyes are bloodshot, and the long tongue is carved with repetitive grooves. A painted red and yellow scale pattern covers the surface of the body, and the creature’s humped back is further accentuated with a carved pattern of volutes.35 The sculpture was not placed in the head compartment of the tomb, as was common in most medium and large tombs in the Chu heartland during this period. It was discovered in a rear compartment to the west of the central main coffin chamber (see the fold out diagram of the tomb in Henan sheng wenwu yanjiusuo 1986, pp. 18–19).

Figure 10.

Line drawing of lacquered wood antlered kneeling sculpture from Tomb 1 at Changtaiguan, Xinyang, Henan. Adapted from Henan sheng wenwu yanjiusuo (1986, pl. 58) courtesy of Zay Olsen.

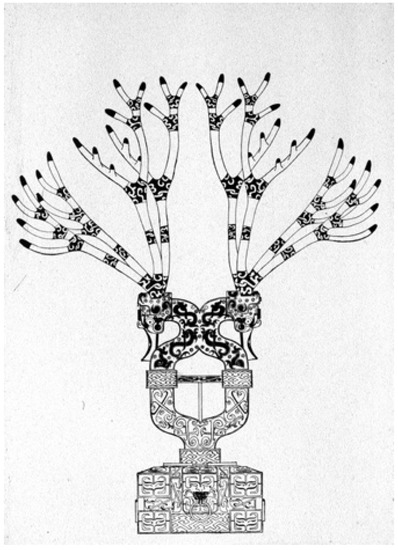

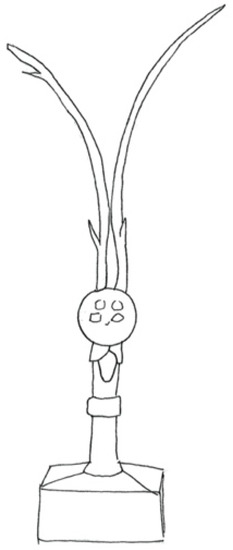

Graphic kneeling figures were not the only antlered objects made from lacquered wood found in the aristocratic tombs at Changtaiguan. The tombs were also provided with non-zoomorphic antler stands related to those found in the Hanxi region and Eastern Hubei. Tomb 1 contained one stand (Figure 11), in addition to the kneeling creature, while Tomb 2 contained two stands (see Henan sheng wenwu yanjiusuo 1986, pls. 70, 110-1, and 110-2).36 Each was found in a side compartment of the tombs, separate from the kneeling figures. The stand in Tomb 1 was interred in a side compartment to the northwest of the coffin chamber, while those in Tomb 2 were in a side compartment north of the main chamber. Although each stand is unique, they share a general typology. They are composed of a square base, a collared body, rectangular head, and deer antlers all fitted together by mortise and tenon. The bodies of the sculptures consist of two truncated pyramids, inverted one over the other at the waist, such as the Baizifan antlered sculptures discussed above. This feature, along with the rectangular shape of the heads on the Changtaiguan sculptures, may indicate a cultural link between the Upper Huai and Eastern Hubei.

Figure 11.

Line drawing of lacquered wood antler stand from Tomb 1 at Changtaiguan, Xinyang, Henan. Adapted from Henan sheng wenwu yanjiusuo (1986, pl. 70.1) courtesy of Zay Olsen.

The Changtaiguan stands were individually decorated with black and red lacquer. Two were painted with motifs shared by other lacquered wooden objects found in the tomb, including curvilinear tendrils, volutes, and triangular spirals reminiscent of those decorating the Yugang sculptures discussed earlier.37 The third stand, from Tomb 2, includes carved decoration (Figure 12). Four separate square panels of decoration are rendered to each side of the square mortise used to secure the body of the stand to the base. Each panel is carved with simple spirals above a pair of almond-shaped motifs below.38 The almond-shaped motifs are repeated on the top of the rectangular head and might be interpreted as pairs of eyes. Regardless of the interpretation of the motifs, these decorative stands emphasize the importance of deer antlers in understanding the antlered tomb sculpture, as it did not always seem necessary to represent something zoomorphic, the antlers were sufficient.

Figure 12.

Line drawing of lacquered wood antler stand from Tomb 2 at Changtaiguan, Xinyang, Henan. Adapted from Henan sheng wenwu yanjiusuo (1986, pl. 110.2) courtesy of Zay Olsen.

Although the antlered kneeling figures and display stands found in the tombs at Changtaiguan are distinctive in comparison to Hanxi models, a fragment of a Hanxi style tomb sculpture (see Henan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 2003, color plate 35.2) was found in the tomb of a vassal of the Chu state at Geling, in Xincai County, Henan (see Appendix A), northeast of Changtaiguan. The Geling tomb was plundered, and unfortunately, only the head of the sculpture in question remained, but it is strikingly similar to the carved figures found in the Chu heartland, especially Jiangling; it likely has its provenance there. The tomb is dated roughly to the fourth century BCE, contemporary with the flourishing of the Hanxi style sculptures in Jiangling County. The plan of the wooden structure of the Geling tomb is notably not Chu in design, as it has a ya-shaped (or ya-xing 亞形, “cross-shaped”) plan (Henan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 2003, p. 22). However, the head of a Hanxi style antlered sculpture was found in the head compartment, in accordance with common practice in the Chu heartland. To date, this is the northernmost example of a Hanxi style antlered sculpture.

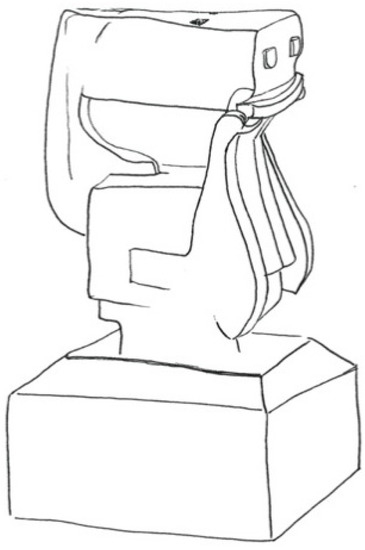

6. Jiangnan

The head fragment discovered in the Geling tomb is not the only example suggesting that the influence of the Hanxi region was far-reaching during the fourth century BCE. Another Hanxi style sculpture (Figure 13) was discovered far to the south in Tomb 89 at Changsha, Hunan province (see Appendix A). Over 2000 tombs dated from the late Springs and Autumns period through the end of the Warring States period have been excavated in this region.39 Notably, only eleven of these tombs yielded sculptures related to those found in other Chu regions, and unfortunately, only five sculptures of the eleven were preserved (Hunan sheng bowuguan et al. 2000a, p. 373 and Changsha shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 2003, fig. 10).40 All were carved from wood and were found in medium and large tombs with wooden burial structures dated from the fifth through the third centuries BCE. According to the excavation report, most of the Changsha antlered sculptures were found in the head compartments of tombs (Hunan sheng bowuguan et al. 2000a, p. 373). However, of the five preserved sculptures, only two were found at the head end of the tomb, the Hanxi style sculpture from Tomb 89 and an addorsed version in a local style discovered in Tomb 1 at Maotingzi in Changsha (Changsha shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 2003, fig. 2).41

Figure 13.

Lacquered wood antlered and tongued sculpture excavated from Tomb 89 at Changsha. Hunan Provincial Museum. Note, the antlers and the original base, which were carved in the Hanxi style, are not pictured. Photo by the author.

With the exception of the Hanxi style sculpture from Tomb 89, the other preserved sculptures unearthed from tombs at Changsha represent local interpretations of the Hanxi style sculpture, and interestingly, they also share some similarities with the antlered kneeling figures found far to the north in the tombs at Changtaiguan in the Upper Huai.42 Two versions of local Changsha style sculptures were discovered in the southern side compartments of Tombs 109 and 397, one with a single head and body (Figure 14) and one with addorsed heads and bodies (see Hunan sheng bowuguan et al. 2000a, p. 374, fig. 303.1-2). In addition to these, an addorsed version Changsha style sculpture was discovered in the head end of Tomb 1 at Maotingzi, in Changsha (see Changsha shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 2003, fig. 2).43 Situated on a smooth square base, the single-headed Changsha style sculpture from Tomb 109 dated from the late fifth to early fourth centuries BCE shares the common attributes of antlered sculptures found in other regions; namely, the round eyes, long extended tongue, and bent neck, but the head of the image is squat, and the figure has a broad arc-shaped jaw and lacks carved fangs.44 The body of the figure is block-like, in contrast to the post-like body of the Hanxi style sculptures. Moreover, the sculpture has clawed arms, which are raised to the creature’s mouth, such as the kneeling figures from Changtaiguan. However, with the absence of fangs and the reptilian prey, the figure lacks the menacing quality of the Changtaiguan sculptures. Unfortunately, only traces of paint remain on the sculpture, but the whole figure was originally covered with painted designs. The painted decoration may have been similar to the addorsed version from Tomb 397.

Figure 14.

Line drawing of lacquered wood, single-headed Changsha style antlered tomb sculpture from Tomb 109 at Changsha, Hunan. Note, the antlers are not pictured. Adapted from Hunan sheng bowuguan et al. (2000b, 2: pl.121.2-3) courtesy of Zay Olsen.

The addorsed sculpture from Tomb 397 dated to the fourth century BCE is in the same style as the single-headed version but has a carved square base, such as those seen on Hanxi style figures. The sculpture is painted with a black lacquer background and is covered with a variety of patterns depicted in red. The base and part of the body of the figure are covered with scroll patterns, and the arms bear feather patterns. Scroll patterns are repeated on the sides of the twin heads, and the nose and eye area are embellished with repeating circles, giving the creature’s face a scaly appearance. Although there are only two examples of Changsha style addorsed sculptures, it is significant that they were found in larger tombs. Future excavations in Changsha may reveal that addorsed sculptures were reserved for tombs belonging to the upper aristocracy, and thus a reflection of the tomb occupant’s status, as seen in the Hanxi region.

Finally, the authors of the tomb report classified an anthropomorphic figure excavated from Tomb 569 at Changsha as an antlered sculpture (Hunan sheng bowuguan et al. 2000a, pp. 373–74), most likely since it can be compared to the one found at Yutaishan in Jiangling. However, the Changsha version lacks some important features, including the elongated post-like body, the long tongue, and the deer antlers, making it seem more similar to a human bust than a fantastical hybrid creature (see Hunan sheng bowuguan et al. 2000b, pl. 121.4). The Changsha figure has human-like ears and a smooth neck. Its human-like torso has rounded shoulders and is fitted into a truncated pyramidal base at the waist. The sculptor even noted the collarbones of the figure with two slight impressions below the shoulders. It may be significant that, in addition to this bust-type object, Tomb 569 contained nearly fifty tomb figurines.45 The majority of these were stored in the northern side compartment of the eastern oriented tomb, while the bust was found in the southern side compartment among pottery and lacquer vessels (Hunan sheng bowuguan et al. 2000a, pp. 395–400). The placement of the tomb figurines and the bust-like sculpture in separate compartments of the tomb seems to distinguish them from one another, as does the use of the base to display the figure, but whether the bust should be categorized as an antlered sculpture is debatable.46 The sculpture adopts the basic format of antlered sculptures in discussion; namely, a figure fitted into a truncated pyramidal base using joinery techniques, but the absence of antlers and a gruesome long tongue is significant. Tomb 569 is dated to the third century BCE, coinciding with the change in burial practices that occurred in Chu toward the end of the Warring States period.

In addition to the figures excavated in Changsha, a few other significant variations of antlered tomb sculptures have been discovered in the Jiangnan region. Four examples were unearthed from three tombs dated to the fourth century BCE excavated to the north of Changsha in Shiban Village, Cili County, Hunan (see Appendix A) (Hunan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Cili xian wenwu baohu guanli yanjiusuo 1995, pp. 173–207). Of the four examples unearthed, all were found in a head compartment or head end of tombs consistent with practices in the Chu heartland, but only two were in good condition.47 These were found side-by-side in Tomb 23, a rare find for a medium-sized Chu tomb.48 Carved from wood and situated on painted square bases, the Shiban Village sculptures have straight bodies and dramatic C-shaped necks (see Hunan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Cili xian wenwu baohu guanli yanjiusuo 1995, p. 198, fig. 27). They retain the long tongue, carved fangs, and antlers characteristic of this genre of figures, but have almond-shaped eyes carved in intaglio on top of distinctive serpentine heads. The Cili sculptures seem to be a cross between Hanxi style figures with curved necks and the zoomorphic sculptures found in tombs in Eastern Hubei. Future excavations in this region of Hunan province will hopefully further clarify these connections.

7. Conclusions

This regional survey of antlered sculptures made from lacquered wood and excavated from Chu tombs dated from the sixth through the fourth centuries BCE confirms the notion that Chu culture was a unique amalgam of regional cultures (Xu 1999, p. 26). Distinct cultural zones can be distinguished in Hanxi, the Nanyang Basin, Eastern Hubei, the Upper Huai, and Jiangnan. The Hanxi region was an artistic center, where antlered sculptures assembled from carved wood made their first appearance and then were refined over time to form the mature Hanxi style. As we saw with sculptures excavated from tombs in the Nanyang Basin and Jiangnan, the mature Hanxi style, which was likely transmitted along the Han River and its tributaries, was adapted and/or manipulated by regional artisans to suit local aesthetic tastes. Artisans in these two regions also diverged from the Hanxi style altogether to create unique local iterations of the antlered tomb sculpture. In the case of the local style sculptures excavated at Yugang in the Nanyang Basin, we also see evidence of artistic exchange with the Zeng state via the Suizao corridor. In the Upper Huai and Eastern Hubei, antlered sculptures are highly localized, suggesting that these micro-regions of the Chu polity received less influence from the Chu heartland.

Traditionally, scholars have associated these sculptures with images illustrated in the Chu Silk Manuscript or with horned mythological deities described in ancient texts, such as the Chu ci 楚辞 (Songs of Chu) or Shanhaijing 山海经 (Classic of Mountains and Seas) (for example, see Hayashi 1972, pp. 157–63; So 1999, pp. 44–45). The most popular interpretation is that these sculptures represent the Earth God Tu Bo, described in the Chu ci (Chen and Yuan 1983, p. 66; Strassberg 2002, p. 58; Yang 1999, p. 347). A more recent analysis by Lai (2015, pp. 122–29) posits they are images of a fecundity god.49 Although this paper does not offer a new interpretation of the significance of Chu antlered sculptures, I believe this regional analysis raises an important question on the function and meaning of these sculptures for future research. Rather than interpreting these sculptures as one class of objects with a singular function and meaning, we should consider that the sculptures were multivalent, defined by regional and local populations across the Chu polity. In some regional contexts, the sculptures may have served multiple functions to benefit both the living and the dead.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Xu Shaohua at Wuhan University. Without his generous support of my research on Chu material culture over the last two decades, this project would not have been possible. I am also grateful to staff at the Hubei Provincial Museum, Jingzhou Museum, and Xiangyang Museum for access to archaeological objects used in this study. My sincere thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. Finally, I would like to express thanks to Zay Olsen, who helped create the line drawings featured in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Distribution map showing sites that yielded antlered tomb sculptures discussed in this article. Map by author.

Notes

| 1 | The term zhenmushou is frequently used in Chinese archaeological reports to refer to sculptures of long tongued hybrid beasts. It is also used to describe similarly grotesque anthropomorphic busts with lolling tongues and deer antlers, as well as simple antler stands. In scholarly literature in the West, the term “tomb guardian figure” is more commonly used to describe the sculptures. |

| 2 | For a selection of previous studies devoted to Chu zhenmushou see: Chaffin (2007), Chen and Yuan (1983), Demattè (1994), Ding (2012), Ding and Zhang (2015), Geng (2007), Huang (2011), and Salmony (1954). |

| 3 | I defined the Hanxi style in a paper presented at the International Conference on Chu Culture and Early Development of the Middle Reaches of the Yangzi River at Wuhan University in 2018 (Chaffin 2021, pp. 97–105). |

| 4 | The Hanxi region was part of the ancient Chu heartland, which also included Handong, the Dan valley, and the Nanyang Basin. See Blakeley (1999, p. 14). |

| 5 | For this analysis, I use the regional framework established by Xu (1999). |

| 6 | I exclude from this study a sculpture classified as a zhenmushou excavated from Tomb 5 at Caojiagang in Dangyang County, which is certainly related. The Caojiagang sculpture does not, however, include the mortises for deer antlers, a feature that characterizes this class of funerary sculpture. Fragments of deer antlers were discovered in the tomb, but their relationship to the wooden sculpture is unclear. Although dated slightly later than the Caojiagang sculpture to the early Warring States period, a sculpture of similar typology was discovered in a Chu tomb in Dangyang County, Tomb 239 at Jinjiashan. It included mortises for deer antlers. Despite the absence of holes for antlers on the Caojiagang sculpture, the similarities between the Caojiagang and Jinjiashan sculptures suggest that the Caojiagang figure may be an early wooden prototype of the antlered hybrid sculpture. For the Caojiagang sculpture see and Hubei sheng Yichang diqu bowuguan (1988, p. 488, fig. 36). For the Jinjiashan sculpture see Hubei sheng Yichang diqu bowuguan and Beijing daxue kaogu xi (1992, p. 157, fig. 114.1). |

| 7 | For the two sculptures from Tomb 6 see Qianjiang bowuguan (1988, p. 39, fig. 7). |

| 8 | Wooden burial structures, coffins, and furniture were also constructed using this joinery technique during the Eastern Zhou. Scholars have long acknowledged the sophisticated woodworking tradition of Chu as a distinctive feature of its culture. See Mackenzie (1987, pp. 82–102). On Chu woodworking techniques see Lin (1978). |

| 9 | For the full report see Qianjiang bowuguan (1988). On the different size classes of Chu tombs see Von Falkenhausen (2003). |

| 10 | For example, see the base on the sculpture excavated from Tomb 229 at Jinjiashan, in Dangyang County. Hubei sheng Yichang diqu bowuguan and Beijing daxue kaogu (1992, p. 157, fig. 114.2). |

| 11 | Two examples of this date were excavated from Tomb 2 at Yangjiashan and Tomb 230 at Jinjiashan, respectively. See Hubei sheng Yichang diqu bowuguan and Beijing daxue kaogu xi (1992, p. 157, figs. 114.3 and 114.4). |

| 12 | Jinancheng may have served as the Chu capital of Ying established in 690 BCE during the Springs and Autumns period. Barry Blakeley (1999), however, disputes this claim as Chu tombs excavated in Jiangling County mostly date to the Warring States period (Blakeley 1999, p. 12). |

| 13 | At Yutaishan, 156 antlered sculptures were unearthed from 156 tombs. At Jiudian, sixty-five examples were excavated from sixty-five tombs. In Jiangling, tombs with more than one antlered sculpture are rare. See Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan (1984, 107–8) and Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (1995, pp. 298–304). |

| 14 | I refer to sculptures that lack apparent zoomorphic facial features as stands. |

| 15 | For example, see the sculpture excavated from Tomb 142 at Yutaishan, which is painted with geometric designs over a black-colored background (Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan 1984, p. 110, fig. 88.1). |

| 16 | Of the sixty-seven preserved examples (out of 156) excavated at the mortuary complex at Yutaishan between 1973 and 1976, thirty-nine (58%) are Hanxi style figures with carved facial features. See Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan (1984, pp. 107–8). |

| 17 | Single-headed antlered sculptures outnumber the addorsed versions. At Yutaishan, seven (10%) of the sixty-seven preserved examples were addorsed. At Jiudian, only three (5%) of sixty preserved examples were addorsed. See Chaffin (2007, pp. 167–73). |

| 18 | An unprovenanced example that can be compared to the Yutaishan sculpture is in the collection of the British Museum in London. The British Museum sculpture was important to Salmony’s study of antlered tomb sculptures (Salmony 1954). |

| 19 | The interment of the anthropomorphic antlered sculpture in a side chamber may suggest that the function of antlered sculptures changed toward the end of the Warring States period in the third century BCE. |

| 20 | The wooden burial structure of Tomb 264 measures 2.8 × 1.08 × 1.18 meters; the wooden burial structure of Tomb 1 at Tianxingguan measures 8.20 × 7.50 × 3.16 meters. The sculpture from Tomb 264 measures 105.6 cm (3.46 feet), while the one from Tomb 1 at Tianxingguan measures 170 cm (5.57 feet). See Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan (1984, pp. 108, 169) and Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan (1982, pp. 74, 105). |

| 21 | Another example of a sculpture with the same formulaic painting program was excavated from Tomb 294 at Jiudian, in Jiangling County. See Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (1995, p. 304, fig. 200). |

| 22 | For the full tomb report see Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (1996). Additionally, see Hubei sheng wenhuaju wenwu gongzuo dui (1966, pp. 33–55). Tombs 1 and 2 at Wangshan are also known from Annette Juliano’s preliminary article on the burials published in 1972. She also discusses the nearby Tomb 1 at Shazhong. See Juliano (1972). |

| 23 | The antlers from Tomb 2 were badly deteriorated but appear to have had twenty points per rack. |

| 24 | By modern standards an eight-point rack is considered impressive. |

| 25 | The writers of the archaeological report suggest that the antlers were made of wood, but there is no evidence of this. |

| 26 | Ten tombs excavated from 2004 to 2005 at Yugang yielded antlered sculptures. |

| 27 | For a study of networks on the Suizao corridor, see Chen (2019). |

| 28 | The other sculpture with a feline-shaped base and long, smooth neck in the local style was excavated from Tomb 222. Unfortunately, the head was damaged and all that remains are two pointed ears. See Xiangyang shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (2011a, p. 76, fig. 48). |

| 29 | The tiger-shaped base on these images implies a potential for motion, in contrast to the stable form of a square base, perhaps symbolizing that these figures were seen as mobile in the tomb rather than fixed in space. |

| 30 | It should also be noted that in addition to the main tomb occupant, Tombs 3 and 5 at Baizifan held the remains of individuals that presumably accompanied the tomb owner into the afterlife. Tomb 3 held the remains of one additional human, while Tomb 5 held two. Each was supplied with a wooden coffin and placed in a side compartment of the tomb. From the thousands of tombs excavated to date, human sacrifice was not commonly practiced in the Chu state in the fourth century BCE. These instances are rare and must reflect regional beliefs. Hubei sheng Echeng xian bowuguan (1983, p. 227). |

| 31 | The authors of the report state that antlers were not found in the tomb. Hubei sheng Echeng xian bowuguan (1983, p. 248). |

| 32 | For the full excavation report see Huanggang shi bowuguan (1999, pp. 220–50). |

| 33 | For the full excavation report see Huangzhou gumu fajue dui (1999, pp. 187–96). |

| 34 | The sculpture was found in the eastern side compartment. The authors of the tomb report hypothesize that the head resembles a dog. Huangzhou gumu fajue dui (1999, p. 195). |

| 35 | The figure from Tomb 1 was painted reddish brown, and has red eyes and a red tongue, and the ears are yellow. The sculpture from Tomb 2 was painted black with red eyes, a yellow mouth and ears, and the body is embellished with running spirals in yellow (Henan sheng wenwu yanjiusuo 1986, pp. 60–61 and 114). |

| 36 | The kneeling figure from Tomb 1 measures 4.2 feet (without antlers), and the one from Tomb 2 measures 4.98 feet. The stand from Tomb 1 measures 1.31 feet (without antlers) and the two from Tomb 2 measure 3.60 and 2.84 feet (with antlers) (Henan sheng wenwu yanjiusuo 1986, pp. 60–61 and 114–116). |

| 37 | Geometric triangular patterns are repeated on many other artifacts in the Xinyang tombs. For example, they appear on a table from Tomb 1, and the bianzhong bell stand and the chime stand from Tomb 2. See Henan sheng wenwu yanjiusuo (1986, p. 38, fig. 27 and pp. 88–89, figs. 59 and 60). |

| 38 | The writers of the report describe the designs as zoomorphic. Henan sheng wenwu yanjiusuo (1986, p. 115). |

| 39 | Changsha tombs are reported in Hunan sheng bowuguan et al. (2000a, 2000b). Also see Changsha shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (2003). |

| 40 | The 2048 tombs excavated at Changsha and reported in Hunan sheng bowuguan et al. (2000a) were in poor condition at the time of excavation; only fifty-nine tombs had remnants of wooden burial structures and/or coffins. Ten of these fifty-nine were furnished with antlered sculptures (Hunan sheng bowuguan et al. 2000a, p. 10). Tomb 1 at Maotingzi reported in Changsha shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (2003, fig. 10) accounts for the additional sculpture discussed in this paper. |

| 41 | Changsha tombs differ from tombs in the Chu heartland in that there are not any tombs where burial furnishings are exclusively buried at the head end, or exclusively in an enclosed head compartment. |

| 42 | I refer to these as Changsha style sculptures. |

| 43 | For a full color image of the sculpture see Changsha shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (2003, color plate tuban lu 4). |

| 44 | The antlers are no longer preserved. According to the report, the sculpture has only one hole carved into its head for the insertion of a deer antler, but from the photograph in the tomb report, it appears that the sculpture has two holes (Hunan sheng bowuguan et al. 2000a, p. 373). |

| 45 | According to the report, the tomb occupant was a 30-something female (Hunan sheng bowuguan et al. 2000a, p. 57). |

| 46 | If the sculpture is indeed a bust, it is the only one known of its kind. |

| 47 | The sculptures were found in Tombs 23, 33, and 36. See Hunan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Cili xian wenwu baohu guanli yanjiusuo (1995, pp. 173–207). |

| 48 | The wooden structure of Tomb 23 measures 3.2 × 1.52 × 1.42 meters (Hunan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo and Cili xian wenwu baohu guanli yanjiusuo 1995, p. 182). |

| 49 | They have also been identified as tomb guardians, spirit guides, demons, demon quellers, and spirits of transformation. See Cook (2006, pp. 137–42) for a summary of previous research on the meaning of antlered and tongued tomb sculptures of Chu. |

References

- Blakeley, Barry B. 1999. The Geography of Chu. In Defining Chu: Image and Reality in Ancient China. Edited by Constance A. Cook and John S. Major. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin, Cortney E. 2007. Strange Creatures of Chu: Antlered Tomb Sculptures of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Periods. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin, Cortney E. 2021. From Zheng to Chu: Tracing the Stylistic Origins of Hanxi Style Antlered and Tongued Tomb Sculptures. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Chu Culture and Early Development of the Middle Reaches of the Yangzi River. Edited by Xu Shaohua, Lothar von Falkenhausen and Gu Kouman. Wuhan: Wuhan University Press, pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Changsha shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo. 2003. Changsha shi Maotingzi Chu mu de fajue. Kaogu 4: 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Beichao. 2019. Cultural Interactions during the Zhou Period (c. 1000–350 BC): A Study of Networks from the Suizao Corridor. Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yuejun 陳躍均, and Wenqing Yuan 院文清. 1983. Zhenmushou lue kao. Jianghan kaogu, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Constance A. 2006. Death in Ancient China: The Tale of One Man’s Journey. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Demattè, Paola. 1994. Antler and Tongue: New Archaeological Evidence in the Study of the Chu Tomb Guardian. East and West 44: 353–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Lan. 2012. Kaogu xue yanjiu shiyu xia zhi Chu shi “Zhenmushou”. Wuhan: Hubei renmin chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Lan, and Yingying Zhang. 2015. Dongzhou shiqi qingtong fangzuo yu Chu shi zhenmushou guanxi tantao. Jianghan kaogu, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Von Falkenhausen, Lothar. 2003. Social Ranking in Chu Tombs: The Mortuary Background of the Warring States Manuscript Finds. Monumenta Serica 51: 439–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Hualing. 2007. Chu ‘Zhenmushou’ de yuanqi yu Chu guo jinglei. Hengyang shifan xueyuan xuebao 28: 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, Minao. 1972. The Twelve Gods of the Chan-Kuo Period Silk Manuscript Excavated at Ch’ang-sha. In Early Chinese Art and Its Possible Influence in the Pacific Basin. Edited by Noel Barnard. New York: Intercultural Arts Press, vol. 1, pp. 157–62. [Google Scholar]

- Henan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo. 2003. Xincai Geling Chu mu. Zhengzhou: Daxiang chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Henan sheng wenwu yanjiusuo. 1986. Xinyang Chu mu. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Henan sheng wenwu yanjiusuo, Henan sheng Danjiang kuqu kaogu fadui, and Xichuan xian bowuguan. 1991. Xichuan Xiasi Chunqiu Chu mu. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Ying. 2011. Chu shi zhenmushou yanjiu. Zhongyuan Wenwu, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Huanggang shi bowuguan. 1999. Hubei Huanggang shi liang zuo zhong xing Chu mu. In Edong kaogu faxian yu yanjiu. Edited by Wu Xiaosong. Wuhan: Hubei kexue jishu chubanshe, pp. 220–50. [Google Scholar]

- Huangzhou gumu fajue dui. 1999. Hubei Huangzhou Guo’erchong Chu mu fajue jianbao. In Edong kaogu fajue yu yanjiu. Edited by Wu Xiaosong. Wuhan: Hubei kexue jishu chubanshe, pp. 187–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei sheng bowuguan. 1989. Zeng Hou Yi mu. 2 vols. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei sheng Echeng xian bowuguan. 1983. Echeng Chu mu. Kaogu xuebao, 223–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei sheng Jingsha tielu kaogu dui. 1991. Baoshan Chu mu. 2 vols. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei sheng Jingzhou bowuguan. 2003. Jingzhou Tianxingguan erhao Chu mu. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan. 1982. Jiangling Tianxingguan yihao Chu mu. Kaogu xuebao, 71–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan. 1984. Jiangling Yutaishan Chu mu. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei sheng Jingzhou diqu bowuguan. 1985. Jiangling Mashan yihao Chu mu. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei sheng wenhuaju wenwu gongzuo dui. 1966. Hubei Jiangling sanzuo Chu mu chutu dapi zhongyao wenwu. Wenwu, 33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo, ed. 1995. Jiangling Jiudian Dongzhou mu. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo. 1996. Jiangling Wangshan Shazhong Chu mu. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo, and Jingmen shi bowuguan. 1996. Jingmen Luopogang yu Zilinggang. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei sheng Yichang diqu bowuguan. 1988. Dangyang Caojiagang 5 hao Chu mu. Kaogu xuebao, 455–500. [Google Scholar]

- Hubei sheng Yichang diqu bowuguan, and Beijing daxue kaogu xi. 1992. Dangyang Zhaojiahu Chu mu. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hunan sheng bowuguan, Hunan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo, Changsha shi bowuguan, and Changsha shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo. 2000a. Changsha Chu mu. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hunan sheng bowuguan, Hunan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo, Changsha shi bowuguan, and Changsha shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo. 2000b. Changsha Chu mu. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hunan sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo, and Cili xian wenwu baohu guanli yanjiusuo. 1995. Hunan Cili xian Shiban cun Zhan Guo mu. Kaogu xuebao, 173–207. [Google Scholar]

- Jingmen shi bowuguan. 2008. Jingmen Zilinggang. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Juliano, Annette L. 1972. Three Large Ch’u Graves Recently Excavated in the Chiangling District of Hupei Province. Artibus Asiae 34: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Guolong. 2015. Excavating the Afterlife: The Archaeology of Early Chinese Religion. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Shoujin. 1978. Zhan Guo xi mu gong sun jie he gongyi yanjiu. Hong Kong: Zhongwen daxue chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, Colin. 1987. The Chu Tradition of Wood Carving. In Style in the East Asian Tradition: Colloquies on Art and Archaeology in Asia. Edited by Rosemary E. Scott and Graham Hutt. London: University of London, pp. 82–102. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, Colin. 1999. The Influence of Textile Designs on Bronze, Lacquer, and Ceramic Decorative Styles during the Warring States Period. Orientations 30: 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Qianjiang bowuguan. 1988. Qianjiang Longwan Xiaohuangjiatai Chu mu. Jianghan kaogu, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Salmony, Alfred. 1954. Antler and Tongue: An Essay on Chinese Symbolism and Its Implications. Ascona: Artibus Asiae Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- So, Jenny. 1995. Eastern Zhou Ritual Bronzes from the Arthur M. Sackler Collections. Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Foundation, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- So, Jenny. 1999. Chu Art. In Defining Chu: Image and Reality in Ancient China. Edited by Constance A. Cook and John S. Major. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Strassberg, Richard, ed. 2002. A Chinese Bestiary: Strange Creatures from the Guideways through Mountains and Seas. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xiangyang shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo. 2011a. Yugang Chu mu. Edited by Zhigang Wang. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Xiangyang shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo. 2011b. Yugang Chu mu. Edited by Zhigang Wang. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Shaohua. 1999. Chu Culture: An Archaeological Overview. In Defining Chu: Image and Reality in Ancient China. Edited by Constance A. Cook and John S. Major. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Xiaoneng, ed. 1999. The Golden Age of Chinese Archaeology. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).