Abstract

Commercial pedestrian streets serve as vital urban public spaces for residents’ daily leisure and social interaction. However, amid rapid urbanization, many such streets exhibit a tendency towards homogenization, raising practical concerns about the capacity of these environments to consistently deliver rich psychological restorative experiences. Existing research on the restorativeness of urban streets has primarily focused on macro or meso scales, leaving the restorative impacts of micro-scale elements, such as public art within streetscapes, insufficiently explored. To address this research gap, this study takes Tanhualin Historic Cultural Street in Wuhan as its research setting. Employing a streetscape image simulation experiment combined with an online questionnaire survey, it assesses the influence of public art on the perceived restorativeness of commercial pedestrian streets. The results indicate that public art substantially enhances the perceived restorative capacity of commercial pedestrian streets. Further analysis reveals clear independent main effects of both the form and theme of public art on perceived restorativeness, with the influence of form being more pronounced, and no statistically significant interaction effect between the two. These findings offer novel insights for enhancing the restorative potential of commercial pedestrian streets and provide design recommendations for future urban street renewal and sustainable development.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Urban Modern Environment and Human Predicament

The high-pressure mode of modern life continues to exacerbate the public’s mental load [1,2]. A growing awareness of the relationship between urban spaces and well-being has placed a premium on urban environments with strong restorative potential for body and mind [3,4,5]. In recent years, extensive research has confirmed the restorative value of natural environments and urban green spaces [6,7]. The academic community has also broadened its perspective to explore the restorative roles of other urban spaces, such as spaces for leisure and socialization, like commercial pedestrian streets [8]. However, amid rapid urbanization, commercial pedestrian streets commonly face issues of homogenization in both their business mix and visual appearance, exemplified by the ubiquitous presence of identically designed global chain franchises such as McDonald’s, KFC, and Starbucks, alongside repetitive domestic chain brands. This loss of regional identity and its consequent anonymity, resulting from the excessive extension of the “International Style,” undermines the street’s potential as a vessel for emotional attachment [9]. It negatively impacts deeper human needs for a sense of belonging, diverse experiences, and mental restoration. As the cultural atmosphere and intangible quality of urban public spaces become increasingly faint in their ability to move and be perceived, we are compelled to consider a critical urban design question: How can cities mitigate homogenization? How can effective interventions enhance a street’s “genius loci,” transforming it into a positive space that fosters mental health? In this regard, the theory of “urban acupuncture” proposed by Spanish urbanist Manuel de Solà-Morales offers inspiration. This theory, which advocates for small-scale, precise, and lightweight interventions to activate declining or underutilized areas [10,11,12], thereby achieving a ripple-effect renewal, constitutes a form of “urban micro-regeneration” [13]. Within this framework, public art, as an intervention medium combining artistry, publicness, and cultural expressiveness, demonstrates unique advantages. While mitigating adverse conditions stemming from urban development, it responds to the need for spatial improvement with relatively low cost and short cycles [14], playing a role in cultivating a sense of place, community consciousness, and civic identity [15].

In summary, from the perspective of environment and human health, this study investigates the restorative capacity of public art in urban commercial pedestrian streets through questionnaire surveys and analysis. It aims to explore the impact of different forms of public art on human perceived restorativeness and encourages the academic community to further explore the restorative potential of public art in cities.

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Restorativeness

“Recovery” refers to the process through which an individual’s physical, psychological, and social functions are restored to a positive state after coping with stressors from the external environment [16]. “Restorative experience” emphasizes the state of this recovery as achieved through contact with specific environments [17]. With the accelerating pace of urbanization and daily life, attentional fatigue has become increasingly prevalent, posing a persistent challenge to mental well-being [18]. Consequently, attention restoration and stress reduction among urban populations have garnered growing attention from multiple disciplines, spanning fields such as psychology, landscape architecture, education, and tourism studies [19,20,21,22].

Among numerous studies, Attention Restoration Theory (ART) and Stress Recovery Theory (SRT) are two predominant restorative theories [23,24,25]. ART posits that prolonged or intense use of directed attention leads to mental fatigue, manifesting as irritability, impulsivity, diminished task performance, and weakened planning capacity. In contrast, environments possessing certain qualities can engage involuntary attention, thereby allowing the fatigued directed attention system to recuperate. This process involves restorative environments facilitating the recovery of an individual’s cognitive clarity and emotional stability through “soft fascination,” which replaces the active inhibition required by directed attention [26]. Based on this, ART proposes key attributes for measuring an environment’s restorative quality, notably Fascination, Being Away, Extent, and Compatibility. Fascination involves configurations that naturally attract and hold focus; Being away describes a condition of separation, whether spatial or cognitive, from the routine setting; Extent relates to the breadth and consistency that foster continued involvement; Compatibility indicates alignment with and support for an individual’s intentions or inclinations [24,27].

1.2.2. Restorative Environments

Current research confirms that natural environments and green spaces are beneficial for psychological and physical restoration [28,29], and possess higher restorative potential compared to urban environments in general [7]. However, with 932.67 million urban residents in China, accounting for approximately 66.2% of the total population [28], a vast number of people live in high-density urban spaces where frequent contact with nature is difficult. For them, obtaining restorative experiences within their daily living environments is particularly crucial. Indeed, a growing number of scholars are recognizing the relationship between the urban context and mental health, acknowledging that beyond natural environments, urban spaces such as buildings, transportation facilities, and infrastructure also possess restorative attributes [29]. Wang, S. and Li, A. argue that various urban public environments, such as urban green spaces, exhibition spaces, commercial spaces, and sports facilities, all exhibit restorative properties. Through contact with these environments, residents’ psychological stress and negative attitudes can be reduced [30].

1.2.3. The Restorative Potential of Urban Commercial Streets

Previous research suggested that urban green spaces possess superior restorative potential compared to streets [31,32,33]. However, subsequent studies have shown that well-planned urban streets can exhibit restorative qualities comparable to those of green spaces. In metropolitan areas, streets occupy 25% to 35% of the land area and are among the most frequently used spaces by residents in high-density cities [34,35]. They not only support daily urban activities such as commuting, shopping, dining, and socializing, but also offer the possibility, through various experiences that occur within them, to temporarily alleviate fatigue and restore energy, thus being closely related to residents’ lives and well-being [36]. Currently, academic research has explored the restorative qualities of various street typologies and their constituent elements. For instance, Yin, Y. T. et al. investigated the anticipated restorativeness of four types of streets in Shanghai, China, ranking them from highest to lowest as: landscape and leisure streets, commercial streets, service-oriented streets, and traffic-oriented streets [37]. Yin, Y. et al. assessed the restorative qualities of various streetscape elements, considering elements such as greenery, pedestrians, and vehicles as significantly influencing users’ restorative experience [38]. This study also noted that different streetscape elements affect the four key characteristics of a restorative environment to varying degrees. Through experimental research, Zhao, J. W. concluded that streets with high green coverage and plant diversity, low volumes of non-motorized traffic, and clear traffic signage contribute to enhanced environmental restorativeness [39].

Among various street types, commercial streets present a complex environmental composition, encompassing functions such as retail, dining, offices, and residences. Consequently, they are expected to contribute to the maintenance of residents’ physical and mental health [5]. Barros et al. comparatively analyzed the restorative potential of commercial streets in the United States and Brazil, suggesting that elements such as interesting street configurations, urban greenery, small businesses, tables and chairs, and shade umbrellas can all contribute to mental relaxation [29]. Barros and Mehta further argued that street furniture, independent businesses, diverse commercial services, building permeability, seating, and personalized spaces can effectively enhance environmental restorativeness, proposing strategies for creating commercial streets that are economically vibrant, healthy, and offer diverse social benefits [40]. These studies collectively demonstrate that streets possess considerable restorative potential and can be intentionally planned and designed as spaces for psychological recovery.

Despite the growing body of research examining the restorativeness of streets, a gap remains in understanding the restorative roles of various specific streetscape elements. A review of the academic literature reveals that current studies primarily focus on assessing the overall restorative level of street environments, aiming to identify the perceived restorative benefits of different environmental components. In general, these studies suggest that elements such as vegetation, landscape features, clear traffic signage, and clean public spaces contribute positively to the restorative quality of a place. Conversely, disorderly and dirty streets, non-motorized traffic, and potential traffic hazards diminish it. These investigations into the restorative effects of streetscapes have concentrated on macro and meso scales [41,42,43], leaving the restorative capacity of micro-scale elements, such as public art within urban neighborhoods, systematically underexplored. Therefore, this study selects commercial pedestrian streets as the test environment to investigate the role of public art within the streetscape, aiming to provide a foundation for designing street environments that enhance residents’ well-being.

1.2.4. Restorativeness of Public Art

Public art refers to artworks created for display in public spaces. It encompasses a range of forms including sculpture, urban furniture, streetscape installations, architectural elements integrated into the built fabric, land art, and temporary works like festival decorations [44,45]. Previous research on it has predominantly leaned towards esthetic considerations. For instance, Tang, J. et al. explored tourists’ esthetic responses to iconic public art, finding that esthetic factors can serve as indicators for measuring the public art experience [46]. Peruzzi, G. et al. analyzed the esthetic and cultural characteristics of 34 urban sculptures across Italy, revealing stereotypes in the portrayal of female figures and shortcomings in cultural policies within the Italian urban environment [47]. Cheng, Y. et al. evaluated public preferences regarding public art [48]. Literature of this kind often treats urban public art as an isolated entity, seldom situating it within a specific environmental context.

In recent years, the definition of public art has continued to expand, accompanied by an increasing number of interdisciplinary studies. Within urban design research, Remesar, A. argued that public art moves beyond the constraints of “fine art” as it becomes integrated into the urban environment, and thus classifies aestheticized urban furniture as a form of public art [49]. This functional turn has become a growing trend, and some scholars have suggested that governments should legally incorporate public-art-oriented urban furniture into street governance frameworks [50]. In municipal public art master plans in the United States, functional public art has likewise been recognized as part of urban infrastructure [51]. In environmental psychology, public art has also shifted from being viewed merely as a decorative element of streetscapes to being understood as a cue that can facilitate psychological restoration in everyday urban environments. Abdulkarim, D. reported that sculptures can significantly enhance the perceived restorativeness of public squares [52]. Li, L. et al. found that virtual immersive public art also has restorative potential, influencing restorative experiences primarily through interactive themes, modes of interaction, and artistic characteristics [53].

1.3. Research Objectives

To bridge the research gap concerning street restorativeness, this study investigates the effect of public art in commercial pedestrian streets on human perceived restorativeness. This investigation is conducted from a dual perspective of design and environmental psychology, grounded in ART, and employs a quantitative assessment methodology. The research aims to enrich the body of knowledge of environmental psychology, provide references for urban residents’ healthy living and sustainable urban design, and provide designers with strategies for optimizing the environmental quality of urban neighborhoods. Consequently, the study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1.

In commercial pedestrian street environments, an environment containing public art will have a higher restorative capacity than one without public art.

H2.

In commercial pedestrian street environments, the restorative capacity of public art varies with its form and theme.

1.4. Research Framework

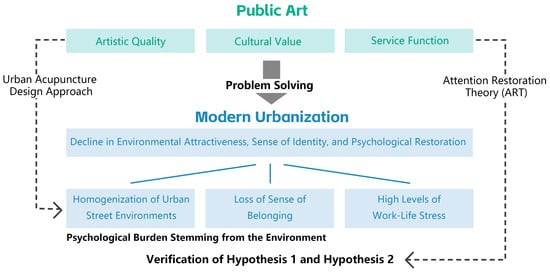

Based on the foregoing, the study proposes a theoretical framework (Figure 1). First, public art is integrated into commercial street environments through the concept of “urban acupuncture.” In this process, public art seeks to address the issue of urban environmental homogenization at the material level, aiming to compensate for a diminished sense of place and emotional connection to the city, and to mitigate the potential psychological problems caused by urban living. Second, the restorative capacity of different types of public art is assessed using the Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS), which is grounded in ART. These two steps are progressive: the first verifies Hypothesis 1 as stated in the research objectives, and the second further discusses Hypothesis 2.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

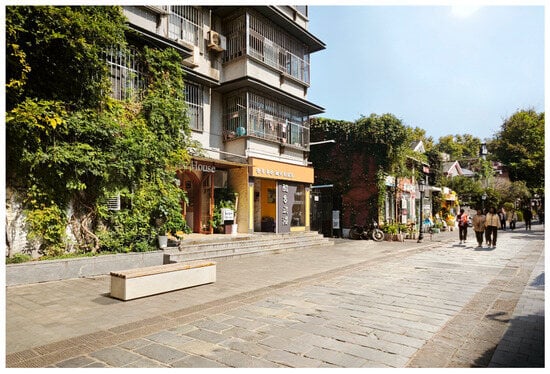

This study selected the Tanhualin commercial pedestrian street in Wuhan, China, as the research site (Figure 2), which aligns with the study’s required conditions. Wuhan is a typical high-density city. It ranks 9th in GDP among Chinese cities, with a permanent population of 13.774 million and an urbanization rate of 75.9% [54]. The Tanhualin street is a landmark destination popular with both locals and tourists. It is a safe, comfortable, and well-maintained commercial pedestrian street featuring shopping, dining, and entertainment functions, situated near numerous residential districts. We selected this pedestrian street as the study site for two main reasons. One reason is that local authorities have placed substantial emphasis in recent years on environmental upgrading and renewal in this area, making it a government-recognized and representative case. Tanhualin commercial pedestrian street is the main thoroughfare of the Tanhualin Historic District. The district has a long history, gradually taking shape after the expansion of Wuchang City in the fourth year of the Hongwu reign of the Ming Dynasty (1371). The area contains 52 historic buildings dating from the Ming and Qing dynasties as well as the early Republican period, and it was included in the third batch of “National Tourism and Leisure Districts” in November 2023 [55,56]. Another reason is that the street aligns with public perceptions of a typical commercial pedestrian street and therefore offers broader applicability. Commercial pedestrian streets are commonly characterized by independent commercial activities, diverse storefronts, public seating, and relatively wide sidewalks. In this sense, Tanhualin Street corresponds to the widely recognized and general concept of a commercial pedestrian street [40]. The specific study location is at the western entrance section of the Tanhualin Street. This spot is adjacent to an animation toy store and a jewelry store, with a café, Hanfu rental shop, and souvenir shops across the street, resulting in relatively high pedestrian flow. The entrance area was chosen to represent a typical and highly frequented node within the commercial pedestrian street.

Figure 2.

Map of Tanhualin Commercial Pedestrian Street, Wuhan, China.

2.2. Visual Stimulus Materials

This study used standardized static photographs of streetscapes as visual stimulus materials for two main considerations. One consideration is that this approach helps ensure internal validity. While restorative experiences are influenced by multisensory environmental factors such as sounds, temperature, and smells [57,58], public art as the studied object is itself a primarily visual medium within the space. To precisely examine the independent effect of its visual attributes, it is necessary to control for multisensory cues and other potential confounds present in real street settings. Using static photographs as an experimental control strategy allows irrelevant variables to be minimized, enabling a clearer logical link between the manipulated variables and the observed outcomes [56]. This also provides a more accurate indication of the potential effect magnitude and the mechanism through which the visual characteristics of public art may operate when they are fully attended to. Another consideration is that this method is widely recognized as valid and practical in environmental perception research. A substantial body of evidence has shown that photo-based environmental evaluations are highly consistent with and reliable relative to in situ assessments [59,60]. Its efficiency and cost-effectiveness also make it well suited for large-scale controlled experiments [61], which explains its extensive use in studies on environmental health effects [62,63].

The production of the visual stimulus materials in this study proceeded in two steps:

- Step 1: Assessment of Wuhan Cultural Symbols

Prior to creating the visual stimuli, an assessment titled “Please select cultural symbols you believe represent Wuhan” was conducted with 45 participants who were either local residents of Wuhan or had lived there for more than two years. This aimed to filter appropriate visual materials to serve as themes for public art. Research by Andrew Lothian suggests that involving over 30 participants in subjective evaluations yields reliable results [64]; thus, the sample size in this study meets the research requirements. The assessment materials were categorized into three groups: Artifact types, Flora & fauna types, and Architecture types. Each subcategory represents local Wuhan culture. The assessment results indicated that Zeng Houyi’s chime bells, the phoenix, and the Yellow Crane Tower received the highest scores (Table 1).

Table 1.

Assessment Results of Local Wuhan Cultural Symbols.

- Step 2: Generation of Images for Evaluation

To investigate the impact of the presence or absence of public art, as well as its different forms and themes, on perceived restorativeness in urban commercial pedestrian streets, we visited the Tanhualin Street in Wuhan for photography. The photographs were taken on 23 October 2025. To ensure ample sunlight and consistent lighting conditions, the shooting was conducted between 12:00 and 14:00. The photographer stood in the middle of the street, shooting horizontally at a height of 1.5 m to simulate the average eye level of the Chinese population. Subsequently, one photograph was selected from dozens taken, underwent fine-tuning using Adobe Photoshop 2022 software, and was used as the base visual stimulus material (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Environmental Setting of the Tanhualin Commercial Pedestrian Street.

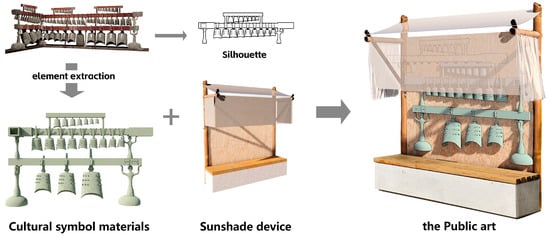

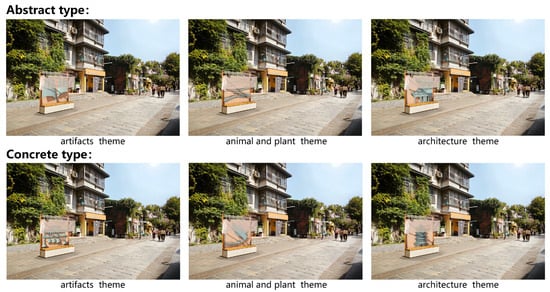

The public art piece assessed at the site integrates with existing seating, forming a combined art installation that incorporates a shade structure with relief sculpture. The model was created using SketchUp 2022 software (Figure 4). This design employs a framework constructed from bamboo, a material representative of traditional Chinese culture, with relief panels affixed to its backboard. The framework is covered by a translucent gauze printed with silhouette patterns of the theme to enhance its recognizability and achieve a layered visual effect. Each piece of public art possesses two attributes: theme and form. The themes were the three representative symbols selected from the assessment in Step 1, which corresponded to three thematic categories: Artifact, Flora & Fauna, and Architecture—namely, Zeng Houyi’s chime bells, the phoenix, and the Yellow Crane Tower, respectively. The forms were categorized into two styles: abstract and figurative. Combining these two attributes resulted in six distinct designs for public art. These were then digitally integrated into the scene using Adobe Photoshop 2022 software (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Design Process of the Public Art.

Figure 5.

Six Street Scenes with Public Art.

2.3. Questionnaire Design

In this study, an online questionnaire was developed and administered between October and November 2025. Collecting data through an online survey is more efficient and convenient than traditional face-to-face interviews. Admittedly, responses to an online questionnaire may be influenced by the screen resolution of the electronic device used by participants. However, the survey also provided detailed written instructions to support participants’ understanding of the questions, which helps mitigate potential bias. As a result, variations in device resolution are unlikely to have a significant impact on the overall findings [65]. Moreover, online questionnaires have been successfully applied in prior studies and have yielded valid results in research related to environmental evaluation [37,66,67]. Furthermore, while psychological restoration involves multiple senses [68], this study primarily focuses on visual characteristics, as people primarily rely on visual cues to gather information and navigate when walking on streets [69].

Specifically, the web-based questionnaire comprised three sections with a total of 85 items.

Part 1: Demographic Characteristics. Five items collected participants’ background information, covering gender, age, educational attainment, mental health status, and whether they had a history of residence in Wuhan. The inquiry regarding residence history was intended to lay groundwork for later exploring whether an individual’s local experience influences their perceived restorativeness of public art with local themes. Participants reporting significant mental health issues were screened out in this section.

Part 2: Pre-test. Three pre-test items were included to familiarize participants with the questionnaire’s general content. Responses in this section were not included in the total score.

Part 3: Assessment of Perceived Restorative Effectiveness. The scale selected was the Perceived Restorativeness Scale-11, in its Chinese version (PRS-11 into Chinese), which was translated and revised by Li, Y. H. et al. based on Pasini et al.’s original scale [70,71]. This scale was developed based on the four dimensions of ART, making it more semantically appropriate for Chinese respondents and minimizing significant measurement error. The Perceived Restorativeness Scale-11 into Chinese demonstrated good reliability, with an overall Cronbach’s α of 0.924. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for its four factors—Fascination, Being Away, Coherence, and Scope—ranged from 0.789 to 0.939, indicating good internal consistency.

During the assessment, participants were presented with the following instruction on the webpage: “Imagine you are in a state of fatigue after a busy week and are strolling through these scenes during your leisure time.” Subsequently, participants used the PRS-11 into Chinese to evaluate the perceived restorative benefits of seven sets of images from the Tanhualin Street: one set without public art and six sets with public art. The order of image presentation was randomized to prevent systematic bias in ratings potentially caused by questionnaire fatigue. Each scene required evaluation using 11 items, scored on a 0 to 10-point Likert scale, where 0 = not at all, 6 = rather much, and 10 = completely. The minimum evaluation time for each set of images is 30 s. This decision was informed by Berto, R.’s study on the restorative potential of images, which reported that participants could achieve a satisfactory restorative experience after an average viewing time of 7 s [72]. In addition, because participants had already become familiar with the questionnaire items during the pilot test, their response speed was expected to increase as they repeated the evaluation tasks. Setting a minimum response time was therefore intended to prevent noise caused by careless rapid clicking.

2.4. Participants

The sampling invitation was initiated by the author and distributed through online channels, with participants recruited from various regions across China. To prevent the same participant from completing the questionnaire multiple times, we designed the questionnaire to allow only one response per individual. A total of 204 questionnaires were collected. After excluding 9 invalid responses due to extreme mental health conditions, skipped items, or a total score of zero, 195 valid questionnaires were retained for analysis. Among the valid participants, 45.13% were male and 54.87% were female. The primary age range was 18 to 35 years old, accounting for 90.26% of respondents. In terms of educational attainment, 79.49% held a bachelor’s or associate degree. Additionally, 44.1% of the evaluators had a residence history in Wuhan of more than two years (Table 2).

Table 2.

Description of characteristics of participants (n = 195).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

This study will employ the PRS-11 into Chinese to assess participants’ perceived restorative potential of urban commercial pedestrian streets. Statistical analysis will be conducted using SPSS 27.0 software. First, the Cronbach’s α coefficient will be calculated for the ratings of the six street scenes with public art to evaluate their internal consistency. If the reliability coefficients reach an acceptable level (α > 0.70), the subsequent analysis will use the mean score of each participant’s six ratings to represent their overall perceived restorativeness level for environments with public art. Second, to examine whether public art confers restorative benefits, a paired-samples t-test will be conducted to compare the difference between each participant’s overall mean score for scenes “with public art” and their score for the scene “without public art.” Furthermore, to investigate differences in restorativeness among different types of public art, a two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) will be performed on the data from the six scenes with public art. Form and theme will serve as within-subjects independent variables, with the perceived restorativeness score for each scene as the dependent variable, to test the main effects of form and theme and their interaction. If the data violate the sphericity assumption, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction will be applied. Finally, to explore the potential influence of demographic variables, participants will be grouped based on whether they have a history of residence in Wuhan. An independent-samples t-test will then be used to compare the differences in overall perceived restorativeness scores between the two groups.

3. Results

3.1. Reliability

The internal consistency of the restorative ratings for the six street scenes with public art was assessed using Cronbach’s α. The analysis yielded Cronbach’s α = 0.963. Given that α > 0.80 is considered an acceptable standard [73], this indicates good internal consistency for the six street scenes as a measurement tool. Consequently, in subsequent analyses, the mean score of each participant’s ratings across these six scenes was used to represent the overall perceived restorativeness level for environments “with public art”.

3.2. Comparison of Restorative Capacity Between Streets with and Without Public Art

To examine whether public art enhances the restorative benefit of commercial pedestrian streets, a paired-samples t-test was conducted to compare the difference between each participant’s overall mean score for scenes “with public art” and their score for the scene “without public art.” The results revealed a statistically significant difference between the two street environments, t (194) = 2.368, p = 0.019 (Table 3). The restorative rating for streets with public art (M = 6.35, SD = 1.65) was significantly higher than that for streets without public art (M = 6.03, SD = 2.03), with a mean difference of 0.32 and a 95% confidence interval for the difference of [0.05, 0.59]. Furthermore, a significant positive correlation was found between the two sets of ratings (r = 0.493, p < 0.001), indicating that while individuals’ baseline perception was consistent, public art systematically improved the restorative quality of the commercial pedestrian street environment. This finding supports Hypothesis 1.

Table 3.

Comparison of Perceived Restorativeness Scores for Streets With and Without Public Art (n = 195).

3.3. Comparison of Restorative Capacity Among Public Art with Different Forms and Themes

To investigate the effects of different design attributes of public art on perceived restorativeness, a 2 × 3 two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on the ratings of the six street scenes with public art. Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated that the assumption of sphericity was met for Form (W = 1.000), Theme (W = 0.983, p = 0.193), and the Form × Theme interaction (W = 0.998, p = 0.864). All p values were greater than 0.05. Therefore, the results for all within-subjects effects are reported based on the assumption of sphericity. The results revealed a highly significant main effect of Form, F (1, 194) = 33.446, p < 0.001; a significant main effect of Theme, F (2, 388) = 5.161, p = 0.006; and a non-significant Form × Theme interaction effect, F (2, 388) = 2.036, p = 0.132 (Table 4). These findings support Hypothesis 2, indicating that the restorative capacity varies among public art pieces with different forms and themes, with both attributes independently exerting significant effects on individual perceived restorativeness, and no significant interaction was observed between them. Following the non-significant interaction, we examined its effect size and observed power. The interaction yielded a small effect (Partial η2 = 0.010), consistent with Cohen’s convention for a “small” effect [74], and was associated with low observed power (0.419). A post hoc calculation indicated that, given the current sample size (n = 195, α = 0.05), the design had sufficient power (>0.80) to detect a medium or larger interaction effect (Partial η2 ≥ 0.06). Therefore, the non-significance likely indicates the absence of a practically meaningful synergistic effect between form and theme.

Table 4.

Tests of Within-Subjects Effects of Form and Theme on Perceived Restorativeness Scores.

To examine the specific influence of the “Form” of public art on perceived restorativeness, pairwise comparisons were conducted following the confirmation of its significant main effect. The estimated marginal means showed that public art in figurative form (M = 6.49, SE = 0.12) received higher restorative ratings than that in abstract form (M = 6.21, SE = 0.12) (Table 5). Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction further confirmed that the difference between the two forms reached statistical significance (mean difference = 0.280, p < 0.001) (Table 6). Specifically, the perceived restorativeness score for figurative-form public art was significantly higher than that for abstract-form public art.

Table 5.

Estimated Marginal Means of Restorative Ratings by Public Art Form.

Table 6.

Pairwise Comparisons of Restorative Ratings Across Public Art Forms.

To examine the specific influence of the “Theme” of public art on perceived restorativeness, pairwise comparisons were conducted following the confirmation of its significant main effect. The estimated marginal means showed that the restorative ratings for different themes, from highest to lowest, were: Architecture theme (M = 6.41, SE = 0.12), Flora & Fauna theme (M = 6.39, SE = 0.12), and Artifact theme (M = 6.24, SE = 0.12) (Table 7). Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction further confirmed that, among the public art themes, the differences between the Artifact theme and the Flora & Fauna theme, and between the Artifact theme and the Architecture theme, both reached statistical significance (Artifact vs. Flora & Fauna: mean difference = −0.142, p = 0.021; Artifact vs. Architecture: mean difference = −0.166, p = 0.014) (Table 8). In contrast, the difference between the Flora & Fauna theme and the Architecture theme was not significant (mean difference = −0.024, p = 1.000). In summary, the public’s perceived restorativeness ratings for the Artifact theme were significantly lower than those for both the Flora & Fauna and Architecture themes, while no significant difference was found between the ratings for the Flora & Fauna and Architecture themes.

Table 7.

Estimated Marginal Means of Restorative Ratings by Public Art Theme.

Table 8.

Pairwise Comparisons for Different Themes of Public Art.

3.4. The Influence of Residence History in Wuhan on Perceived Restorativeness of Public Art

To explore the potential influence of demographic variables, participants were grouped based on whether they had a residence history in Wuhan of more than two years. An independent-samples t-test was then conducted to compare the differences in perceived restorativeness scores between the two groups. The statistical data showed that participants with a residence history in Wuhan (n = 86) had slightly higher overall restorative scores (M = 6.44, SD = 1.76) compared to those without such a history (n = 109, M = 6.19, SD = 1.42) (Table 9). Levene’s test for equality of variances yielded F = 2.972, p = 0.086 (>0.05), indicating homogeneity of variances between the two groups and thus meeting the assumption for the t-test. Therefore, the results from the “Equal variances assumed” row were interpreted. The independent-samples t-test indicated that there was no statistically significant difference in the overall perceived restorativeness scores between participants with and without a residence history, t (193) = 1.108, p = 0.269, with a mean difference of 0.252 and a 95% CI of [−0.197, 0.702].

Table 9.

Perceived Restorativeness Scores: Comparison Between Participants With and Without Wuhan Residence History.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Restorative Potential of Public Art in Commercial Pedestrian Streets

The process of global urbanization is an unstoppable trend, particularly pronounced in developing countries, generating various urban issues that negatively impact mental health. The academic community has recognized the severity of this problem and has focused on the restorative effects of urban street environments. Numerous studies have identified factors such as vehicles, traffic signage, buildings, vegetation, and sound as significant factors influencing street restorativeness [38,39,58]. Furthermore, we observe that public art can enhance the cultural dimension of urban spaces. This observation motivates our exploration of its restorative role, thereby enriching research on sustainable urban development. Our study demonstrates that public art can enhance the restorative effect of commercial pedestrian streets. This finding aligns with the work of Paula Barros et al., who suggested that interesting configurations within the street environment improve people’s assessment of its potential for psychological restoration [29]. Furthermore, the support for Hypothesis 1 aligns with the fundamental principles of ART. The presence of public art may enhance the restorative experience by engaging fascination and enriching the visual experience of the streetscape, thereby consciously or unconsciously capturing pedestrians’ attention. This mechanism contributes to fulfilling the key restorative conditions posited by ART and thus resonates with subsequent research by Paula Barros et al. on the vitality of commercial streets [40], and it is also consistent with Abdulkarim, D. et al.’s argument that public art can enhance the “attractiveness” of public squares [52].

As public art becomes increasingly integrated with the urban environment, it is also being assigned multiple urban functions. For instance, through its combination with street furniture, interactive installations, and architecture, public art has evolved into a diverse category of design that can be viewed, sat on, walked through, and interacted with. Research has confirmed that, beyond greenery, elements such as facilities, furniture, and sculptures are also correlated with restorative experiences and satisfaction [57], while improvements in physical conditions can influence states of fatigue and recovery [75]. By integrating form and function, public art enriches the range of experiences that may occur in a place, thereby strengthening its compatibility within street environments. This compatibility may facilitate deeper engagement with restorative experiences associated with public art. As noted by Li, L. et al., the restorative role of compatibility appears particularly salient in experiential public art that emphasizes interaction and participation [53].

From a broader environmental perspective, Zhao, J. W., in a study on the restorativeness of urban cultural landscapes, posited that landscape features such as sculptures, pavilions, and seating can enhance the restorative potential of an environment [76]. These features share similarities with public art and warrant targeted investigation in future research.

4.2. Differences in Restorativeness Among Different Types of Public Art

Although street environments with public art were overall rated higher than those without, significant differences also exist within the former category. First, in the evaluation of restorative quality for different forms of public art, the figurative form was rated higher than the abstract form. This finding aligns with Cheng, Y. et al., who reported that people tend to show stronger esthetic preference for figurative public art [48]. Similar patterns have also been documented in studies on images and painting [77,78]. The subjective experience of artworks is a complex process involving perception, cognition, and memory, and it varies with the degree of abstraction [79]. Figurative art typically depicts existing objects with accurate proportions and detailed features [80], whereas abstract art often abandons specific recognizable forms to emphasize formal qualities, spatial relationships, and material expression [81]. As a result, figurative works are generally more readily perceived, while abstract works require deeper perceptual and cognitive processing. At the level of affect and interest, prior research suggests that images that are complex yet easy to understand are more likely to elicit interest [82]. This may help explain why figurative types are often preferred, as abstract images are typically distilled and simplified from the complexity of the real world, making them comparatively minimal yet harder to identify or interpret.

Second, in the evaluation of restorative quality for different public art themes, the Architecture theme scored the highest, the Flora & Fauna theme followed closely with a marginal difference, and the Artifact theme scored the lowest. This may be because historical buildings and flora & fauna are more commonly encountered in daily life, whereas cultural relics associated with the Artifact theme are less common. Specifically, the Yellow Crane Tower is a famous historical building in Wuhan and across China, renowned as one of the “Three Great Towers South of the Yangtze River,” and has been celebrated in numerous literary works [83]. Therefore, when people encounter public art with the Yellow Crane Tower theme, it may evoke knowledge about the building or fond memories of past visits. This urban memory serves as an important source and cue for reflection and reverie [84], which may explain its higher restorative quality. The second-place ranking of the Phoenix within the Flora & Fauna theme may be related to the historical and cultural context of Hubei Province and Wuhan City. The Phoenix pattern is a totem of Jing-Chu culture, and there is even a local folk saying associating “people of Hubei” with the “Phoenix” [85]. Furthermore, the Phoenix totem, alongside the dragon totem of the Yellow River basin, constitutes two fundamental auspicious totems at the roots of Chinese civilization, regarded as symbols of good fortune in China, which may also evoke spiritual resonance. Finally, the lowest ranking of Zeng Houyi’s chime bells might be because they are displayed in museums, making them less familiar and more distant from people’s daily lives compared to the former two themes. This sense of unfamiliarity and detachment may account for their relatively lower restorative ratings.

Finally, the study found that the influences of public art “Form” and “Theme” on restorativeness are independent of each other. This suggests that form and theme may affect individual perceived restorativeness through distinct psychological pathways. Specifically, participants’ ratings for the three themes showed a consistent rank order—Architecture > Flora & Fauna > Artifact—and this order did not change with variations in form. More importantly, the figurative form provided a relatively constant enhancement to the restorative ratings across all themes compared to the abstract form. This indicates that form may influence the legibility of information and perceptual fluency [79,86], potentially enhancing the positive experience for all themes by reducing cognitive load.

4.3. The Influence of Residence History on Perceived Restorativeness of Public Art

In the questionnaire, this study used “a residence history in Wuhan of more than two years” as the screening criterion, aiming to distinguish groups with more substantial exposure to the local cultural environment. The data analysis revealed that the restorative benefit derived from public art did not show a significant difference between groups with different residence histories. This suggests that the restorative effect of public art may possess a degree of cross-group universality, as its mechanism of action may not necessarily rely on a profound understanding of specific regional culture or long-term lived experience. Furthermore, the local cultural elements integrated into the themes of public art, in terms of their form and thematic content, might inherently possess strong perceptibility and emotional resonance. This could, to some extent, mitigate the influence of differences in cultural familiarity, allowing individuals from diverse backgrounds to derive comparable positive psychological experiences from it.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Summary

The study demonstrates that public art can effectively enhance the perceived restorativeness of commercial pedestrian streets. This finding supports the established view that “environments possessing attraction and fascination can augment restorative experiences in urban streets.” Furthermore, the restorative benefit varies depending on the form and theme of the public art. Specifically, the main effect of form is particularly significant, with figurative-form public art yielding higher restorative benefits than abstract form. The main effect of theme is significant, with the Architecture and Flora & Fauna themes offering significantly higher restorative benefits than the Artifact theme, with the Architecture theme scoring highest, though its difference from the Flora & Fauna theme was not statistically significant. No significant interaction effect was found between form and theme. Additionally, to control for the potential systematic influence of demographic background on overall evaluation, this study incorporated residence history in Wuhan as a grouping variable in the analysis. No significant difference was found in the evaluation results, preliminarily indicating that the restorative effect of public art in commercial pedestrian street environments possesses a degree of cross-group universality. These conclusions provide new insights for restorative streetscape theory and offer valuable references for urban environmental design practice. They suggest that designers, when selecting public art for commercial pedestrian streets, may prioritize figurative forms and then comprehensively consider appropriate themes based on factors such as site context and culture. In addition, designers are encouraged to adopt appropriate strategies to enhance the public’s esthetic literacy and appreciation of public art, which may contribute to more diverse and inclusive urban environments.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that may affect the validity of the research or the generalizability of its findings.

- The participant sample consisted primarily of young adults (aged 18–35). Because recruitment relied mainly on online academic and social media channels, the sample showed limited diversity in age and sociodemographic characteristics, and systematically excluded individuals with limited access to digital resources, particularly older adults. While research has established the validity of using university student samples [59], subsequent studies should expand to include broader and more diverse participant groups to derive more precise and generalizable conclusions. Specifically, such future studies need to analyze whether and how participants from different age groups vary in their understanding of and preference for digital images, artistic themes, and representational forms, and whether these differences influence the restorative efficacy.

- Due to the lack of comprehensive sociodemographic data collection, the present questionnaire-based study could not fully examine the influence of background factors such as occupation, income, or household characteristics. Missing data may limit the depth and generalizability of the findings. For example, some studies suggest that art professionals tend to prefer figurative art, whereas non-professionals may show no clear preference in artistic form, potentially because professionals can better perceive artistic meaning, craftsmanship, and decorative qualities [48,87,88]. Other studies report contrasting patterns, indicating that professionals may prefer abstract art [89]. These divergent perspectives were not examined in the current study. Future research should investigate how such demographic and professional variables shape evaluations, thereby improving the robustness and relevance of the conclusions.

- The study context was a typical commercial pedestrian street in China, and the cultural background of the public art themes was rooted in the Central China region associated with Wuhan. To overcome this limitation, the findings should also be tested in other regions across China and worldwide.

- This study only evaluated the impact of the form and theme of public art on restorativeness. However, public art is a complex artistic category, and factors such as its shape, color, material, scale, quantity, and location—which may influence restorative quality—were not assessed and warrant further investigation.

- Photographic stimuli cannot represent the full, multisensory experience of a streetscape. When entering a pedestrian street, additional sensory stimuli such as auditory, olfactory, and tactile inputs may influence restorative evaluations. Future research could employ methods such as immersive virtual reality (VR) to more authentically simulate streetscape environments, thereby enhancing the practical relevance of the studies.

- This study’s online questionnaire approach has certain limitations. Although large-scale random sampling helped balance individual and device variations, participants evaluated the scenes under an instructed, assumed state of fatigue. Their actual physiological and emotional states at the time of response were not measured, which could have introduced variability into the ratings. Future research could validate these findings in controlled laboratory settings by incorporating physiological measurements and employ more covert experimental designs to reduce potential demand characteristics.

Overall, despite these limitations, this study offers a new perspective for research on restorative public spaces. Future work is encouraged to further explore the mechanisms through which public art supports psychological restoration, adopt richer research approaches and paradigms, and develop a more systematic theoretical framework for the perceived restorativeness of public art. Such efforts may provide scientific evidence for designing healthier, more diverse, inclusive, and sustainable urban environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, and writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; supervision, writing—review and editing, and formal analysis, L.L. and X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the 2021 General Program of the National Social Science Fund of China (Arts) “A Study on the Design Trends in Century-Long Modern China” (Grant No. 21BG36).

Institutional Review Board Statement

We believe this study does not require formal ethics committee review/approval. According to the responsible person’ words of the first author’s university, an anonymous, non-invasive questionnaire survey involving adult participants is generally exempt from formal IRB approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study may be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Linfan Pan from Jiangnan University for her valuable suggestions during the development of this manuscript. We also extend our thanks to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive feedback, which have helped to significantly improve the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hartig, T. Restorative Environments. Encycl. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Zhang, T.; Sullivan, W.C. Healthy Cities: Mechanisms and Research Questions Regarding the Impacts of Urban Green Landscapes on Public Health and Well-Being. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2015, 3, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, L.E. The Relationship of Urban Design to Human Health and Condition. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 64, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Myron, R.; Stansfeld, S.; Candy, B. A Systematic Review of the Evidence on the Effect of the Built and Physical Environment on Mental Health. J. Public Ment. Health 2007, 6, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Place Value: Place Quality and Its Impact on Health, Social, Economic and Environmental Outcomes. J. Urban Des. 2019, 24, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Weinstein, N.; Bernstein, J.; Brown, K.W.; Mistretta, L.; Gagné, M. Vitalizing Effects of Being Outdoors and in Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.M.; Trojan, J. The Restorative Value of the Urban Environment: A Systematic Review of the Existing Literature. Environ. Health Insights 2018, 12, 1178630218812805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, M.P.; Hidalgo, M.C. Aesthetic Preferences and the Attribution of Meaning: Environmental Categorization Processes in the Evaluation of Urban Scenes. Int. J. Psychol. 2005, 40, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, B.; Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Cui, C.; Zeng, S. What Do Local People Really Need from a Place? Defining Local Place Qualities with Assessment of Users’ Perceptions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlotti, P. “Architectural Acupuncture” in Urban Morphology Studies. Land 2024, 13, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Solà-Morales, M. A Matter of Things; NAi Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, J. Urban Acupuncture: Celebrating Pinpricks of Change That Enrich City Life; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Xie, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y. A Multi-Objective Crossover Parallel Combinatorial Optimization (MCPCO) Model for Site Selection of Catalyst Elements in Urban Micro-Renewal. Land 2025, 14, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, J.M.; De Castro Mazarro, A. Pinning down Urban Acupuncture: From a Planning Practice to a Sustainable Urban Transformation Model? Plan. Theory Pract. 2022, 23, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.; Robertson, I. Public Art and Urban Regeneration: Advocacy, Claims and Critical Debates. Landsc. Res. 2001, 26, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Bowler, P.A. Further Development of a Measure of Perceived Environmental Restorativeness; Institute for Housing Research, Uppsala University: Uppsala, Sweden, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Subiza-Pérez, M.; Pasanen, T.; Ratcliffe, E.; Lee, K.; Bornioli, A.; de Bloom, J.; Korpela, K. Exploring Psychological Restoration in Favorite Indoor and Outdoor Urban Places Using a Top-down Perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 78, 101706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peen, J.; Schoevers, R.A.; Beekman, A.T.; Dekker, J. The Current Status of Urban-Rural Differences in Psychiatric Disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2010, 121, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.; Hartig, T. Restorative Qualities of Favorite Places. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, X.Y. Assessing the Perceived Restorative Qualities of Vacation Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.M.; Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Fuhrer, U. Restorative Experience and Self-Regulation in Favorite Places. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, G. In Search of Fresher Air: The Influence of Relative Air Quality on Vacationers’ Perceptions of Destinations’ Restorative Qualities. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and Affective Response to Natural Environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1983; pp. 85–125. ISBN 978-1-4613-3541-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. Meditation, Restoration, and the Management of Mental Fatigue. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 480–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S.; Brown, T. Environmental Preference: A Comparison of Four Domains of Predictors. Environ. Behav. 1989, 21, 509–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01&zb=A0301&sj=2023 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Barros, P.; Mehta, V.; Brindley, P.; Zandieh, R. The Restorative Potential of Commercial Streets. Landsc. Res. 2021, 46, 1017–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, A. Demographic Groups’ Differences in Restorative Perception of Urban Public Spaces in COVID-19. Buildings 2022, 12, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Hartig, T.; Staats, H. Psychological Benefits of Walking: Moderation by Company and Outdoor Environment. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2011, 3, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnafick, F.-E.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. The Effect of the Physical Environment and Levels of Activity on Affective States. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Corazon, S.S.; Sidenius, U.; Kristiansen, J.; Grahn, P. It Is Not All Bad for the Grey City—A Crossover Study on Physiological and Psychological Restoration in a Forest and an Urban Environment. Health Place 2017, 46, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, A.B. Keynote: Looking, Learning, Making [Streets: Old Paradigm, New Investment]. Places 1997, 11, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Merriman, P. Driving Places: Marc Augé, Non-Places, and the Geographies of England’s M1 Motorway. Theory Cult. Soc. 2004, 21, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M.; Gabrieli, T.; Hickman, R.; Laopoulou, T.; Livingstone, N. Street Appeal: The Value of Street Improvements. Prog. Plan. 2018, 126, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Thwaites, K.; Simpson, J. Exploring the Use of Restorative Component Scale to Measure Street Restorative Expectations. Urban Des. Int. 2022, 27, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuting, Y.; Yuhan, S.; Zhenying, X.; Thwaites, K.; Kexin, Z. An Explorative Study on the Identification and Evaluation of Restorative Streetscape Elements. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2020, 8, 76–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, H. Characteristics of Urban Streets in Relation to Perceived Restorativeness. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2020, 30, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, P.; Mehta, V. Does Restorativeness Support Liveliness on Commercial Streets? J. Urban Des. 2024, 29, 400–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dillen, S.M.E.; de Vries, S.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Greenspace in Urban Neighbourhoods and Residents’ Health: Adding Quality to Quantity. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2012, 66, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Tsai, C.-C.; Sullivan, W.C.; Chang, P.-J.; Chang, C.-Y. Does Awareness Affect the Restorative Function and Perception of Street Trees? Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindal, P.J.; Hartig, T. Effects of Urban Street Vegetation on Judgments of Restoration Likelihood. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binoy, P. The Role of Public Art Has Changed in Recent Times: A Study. Liño 2024, 30, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, T.; Gadaloff, S. Public Art for Placemaking and Urban Renewal: Insights from Three Regional Australian Cities. Cities 2022, 127, 103747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yan, L.; Xu, J. Tourists’ Experience of Iconic Public Art in Macau. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2021, 19, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzzi, G.; Bernardini, V.; Riyahi, Y. Women’s Statues in Italian Cities. A Study of Public Art and Cultural Policies. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2024, 30, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Hou, G.; Xiao, X. Research on the Preference of Public Art Design in Urban Landscapes: Evidence from an Event-Related Potential Study. Land 2023, 12, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remesar, A. Urban Regeneration: A Challenge for Public Art; Edicions Universitat Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 1997; ISBN 978-84-475-1737-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tekle, A.M. Rectifying These Mean Streets: Percent-For-Art Ordinances, Street Furniture, and the New Streetscape. Ky. Law J. 2015, 104, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Brown. Keener Cary Public Art Master Plan. Available online: https://townofcary.uberflip.com/i/320439-cary-public-art-master-plan/0? (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Abdulkarim, D.; Nasar, J.L. Are Livable Elements Also Restorative? J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shukor, S.F.A.; Noor, M.S.B.M.; Hasna, M.F.B. The Impact of Virtual Immersive Public Art on the Restorative Experience of Urban Residents. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuhan Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Available online: https://tjj.wuhan.gov.cn/tjfw/tjnj/202511/t20251111_2675660.shtml (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Gao, S.; Liang, Y.; Sun, M. The characteristics of OGC and TGC pictures and their applications in the construction and online dissemination of tourist destination image: A case of Tanhualin historical and cultural district. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. 2025, 60, 280–297. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H. Self-organized Renew Phenomenon in Hybrid Historic Neighborhoods Update and Its Implications: Tanhualin Neighborhoods in Wuchang Old City for Example. Zhuangshi 2015, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Du, J.; Chow, D. Perceived Environmental Factors and Students’ Mental Wellbeing in Outdoor Public Spaces of University Campuses: A Systematic Scoping Review. Build. Environ. 2024, 265, 112023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xu, J.; Lange, E.; Cao, J. Which Factors Enhance the Perceived Restorativeness of Streetscapes: Sound, Vision, or Their Combined Effects? Insights from Four Street Types in Nanjing, China. Land 2025, 14, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamps, A.E., III. Demographic Effects in Environmental Aesthetics: A Meta-Analysis. J. Plan. Lit. 1999, 14, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Böök, A.; Garvill, J.; Olsson, T.; Gärling, T. Environmental Influences on Psychological Restoration. Scand. J. Psychol. 1996, 37, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Luo, P.; Wang, R.; Cai, Y. Correlations between Aesthetic Preferences of River and Landscape Characters. J. Environ. Eng. Landsc. Manag. 2013, 21, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.F.; Hoffman, R.E. Rating Reliability and Representation Validity in Scenic Landscape Assessments. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 54, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazhouhanfar, M.; Kamal, M.S.M. Effect of Predictors of Visual Preference as Characteristics of Urban Natural Landscapes in Increasing Perceived Restorative Potential. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lothian, A. Landscape and the Philosophy of Aesthetics: Is Landscape Quality Inherent in the Landscape or in the Eye of the Beholder? Landsc. Urban Plan. 1999, 44, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Guo, W.; Wei, F.; Luo, Y.; Liu, C. Improving the Environmental Health Benefits of Modern Community Public Spaces: Taking the Renovation of Residential Facades as an Example. Systems 2023, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M. Validating the Use of Internet Survey Techniques in Visual Landscape Assessment—An Empirical Study from Germany. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wherrett, J.R. Issues in Using the Internet as a Medium for Landscape Preference Research. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1999, 45, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, L.; Hubbard, P. People and Place: The Extraordinary Geographies of Everyday Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-315-83869-4. [Google Scholar]

- Amundsen, I. The Road through the Landscape. In Road Development and Landscape Architecture in Norway; Edition Topos; Callwey: München, Germany, 2004; pp. 43–55. ISBN 978-3-7667-1604-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pasini, M.; Berto, R.; Brondino, M.; Hall, R.; Ortner, C. How to Measure the Restorative Quality of Environments: The PRS-11. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 159, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Du, X.; Wu, J. Revision of the Chinese version of the Perceived Restorative Scale(PRS-11). China J. Health Psychol. 2024, 32, 1883–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. Exposure to Restorative Environments Helps Restore Attentional Capacity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.T.E. Eta Squared and Partial Eta Squared as Measures of Effect Size in Educational Research. Educ. Res. Rev. 2011, 6, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, S.; Smolders, K.; van der Meij, L.; Demerouti, E.; de Kort, Y. A Higher Illuminance Reduces Momentary Exhaustion in Exhausted Employees: Results from a Field Study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 102, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhao, J.; Ye, L. Culture Is New Nature: Comparing the Restorative Capacity of Cultural and Natural Landscapes. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2018, 75, 847–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, D.M.; McDougall, K.H.; Jalava, S.T.; Bodner, G.E. Prediction of Beauty and Liking Ratings for Abstract and Representational Paintings Using Subjective and Objective Measures. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leder, H.; Gerger, G.; Dressler, S.G.; Schabmann, A. How Art Is Appreciated. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2012, 6, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellotti, S.; Scipioni, L.; Mastandrea, S.; Viva, M.M.D. Pupil Responses to Implied Motion in Figurative and Abstract Paintings. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautamäki, R.; Laine, S. Heritage of the Finnish Civil War Monuments in Tampere. Landsc. Res. 2020, 45, 742–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, W.; He, X.; Tang, X.; Lai, S.; Dai, Z. The Role of Understanding on Architectural Beauty: Evidence From the Impact of Semantic Description on the Aesthetic Evaluation of Architecture. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 125, 1438–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P.J. Cognitive Appraisals and Interest in Visual Art: Exploring an Appraisal Theory of Aesthetic Emotions. Empir. Stud. Arts 2005, 23, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L. A Historical Study of the Relationship Between the Yellow Crane Tower and Daoism. Relig. Stud. 2016, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Semiz, S.N.C.; Özsoy, F.A. Transmission of Spatial Experience in the Context of Sustainability of Urban Memory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. The Ideological Connotation and Heritage Significance of the Phoenix Culture in Jing-Chu. Hubei Soc. Sci. 2015, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastandrea, S.; Bartoli, G.; Carrus, G. The Automatic Aesthetic Evaluation of Different Art and Architectural Styles. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2011, 5, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Else, J.E.; Ellis, J.; Orme, E. Art Expertise Modulates the Emotional Response to Modern Art, Especially Abstract: An ERP Investigation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darda, K.M.; Cross, E.S. The Role of Expertise and Culture in Visual Art Appreciation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihko, E.; Virtanen, A.; Saarinen, V.-M.; Pannasch, S.; Hirvenkari, L.; Tossavainen, T.; Haapala, A.; Hari, R. Experiencing Art: The Influence of Expertise and Painting Abstraction Level. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.