Ground Settlement Susceptibility Assessment in Urban Areas Using PSInSAR and Ensemble Learning: An Integrated Geospatial Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Study

1.2. Literature Review

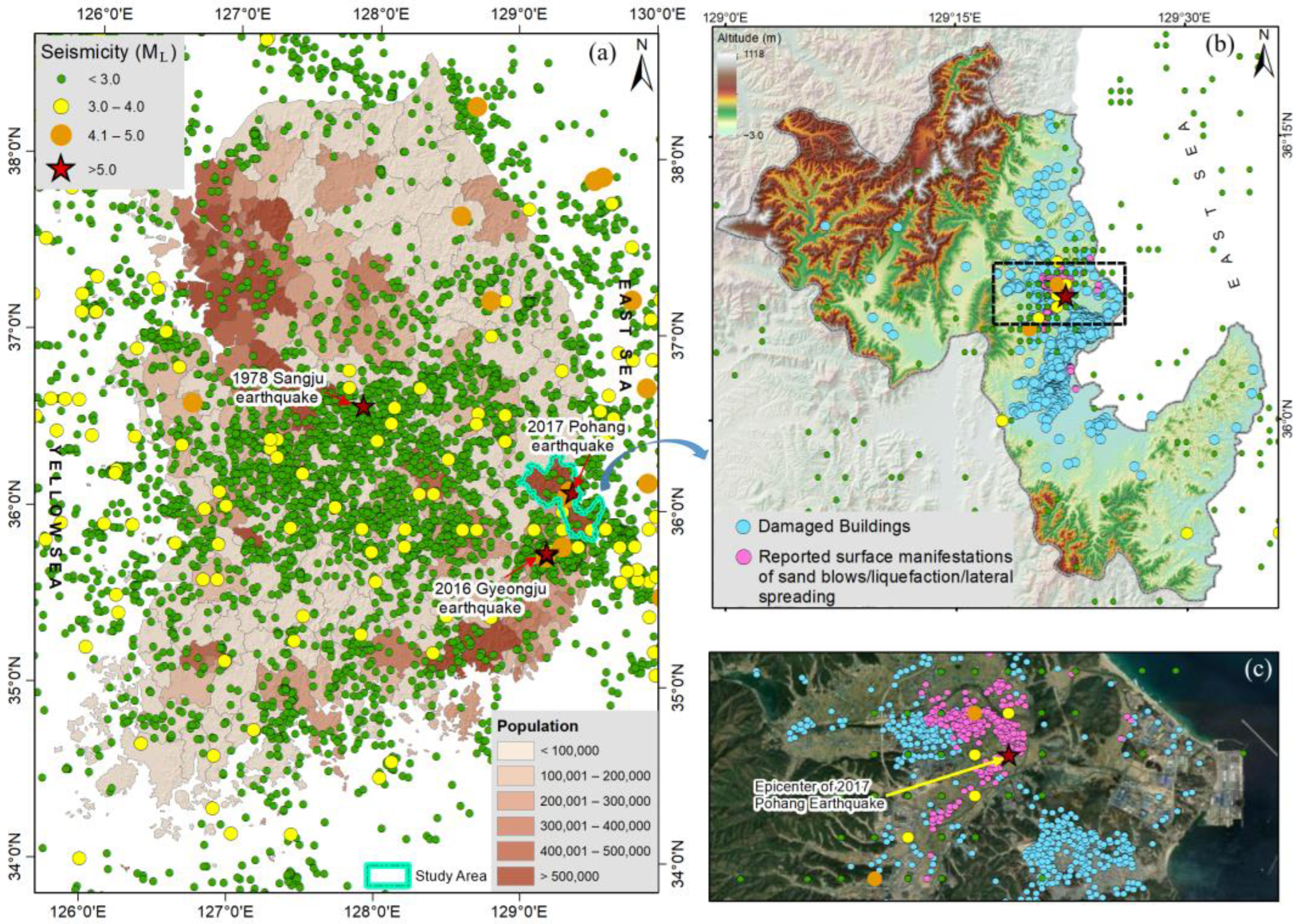

2. Study Area

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

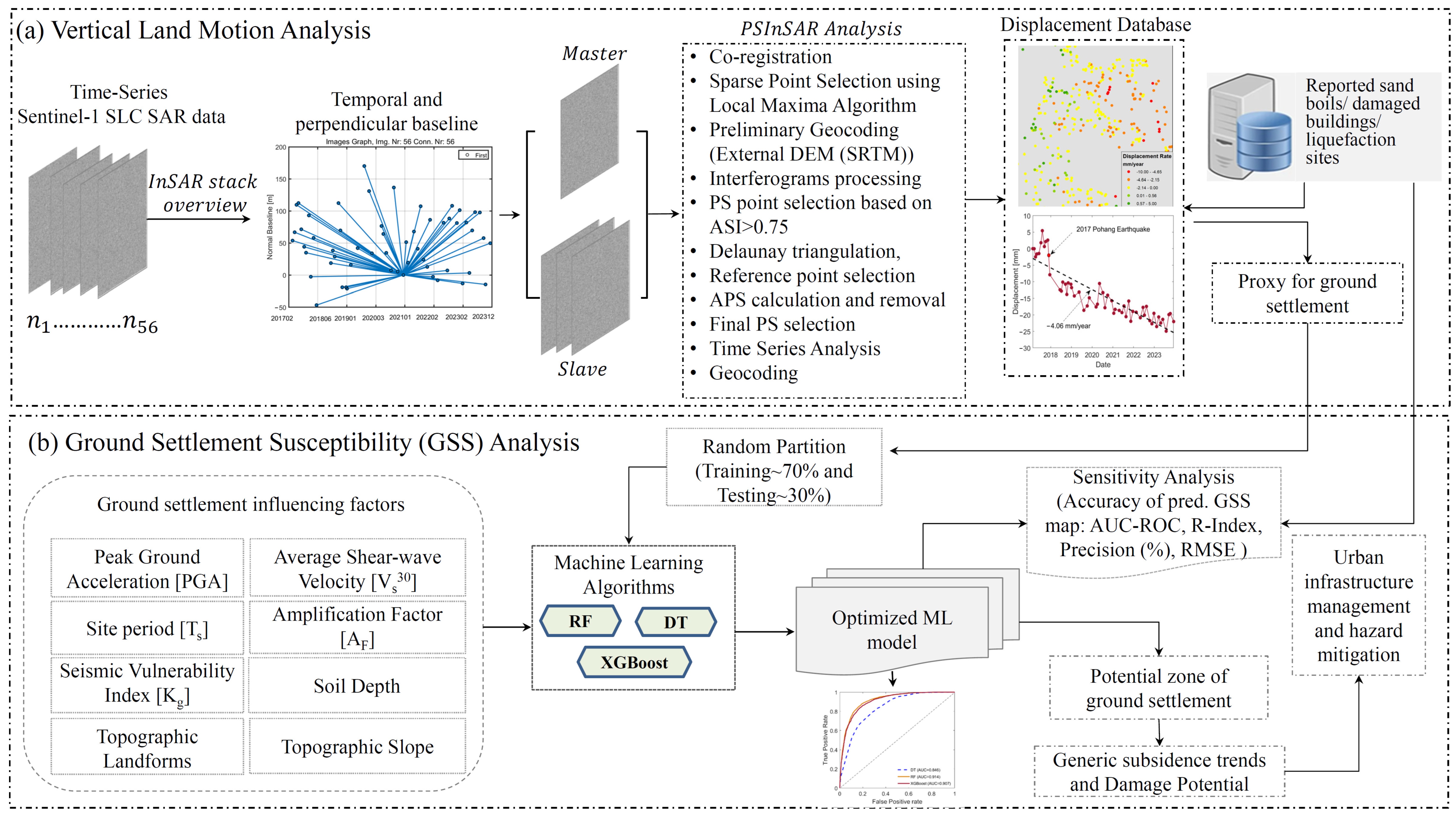

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. PSInSAR-Based Vertical Ground Displacement Analysis

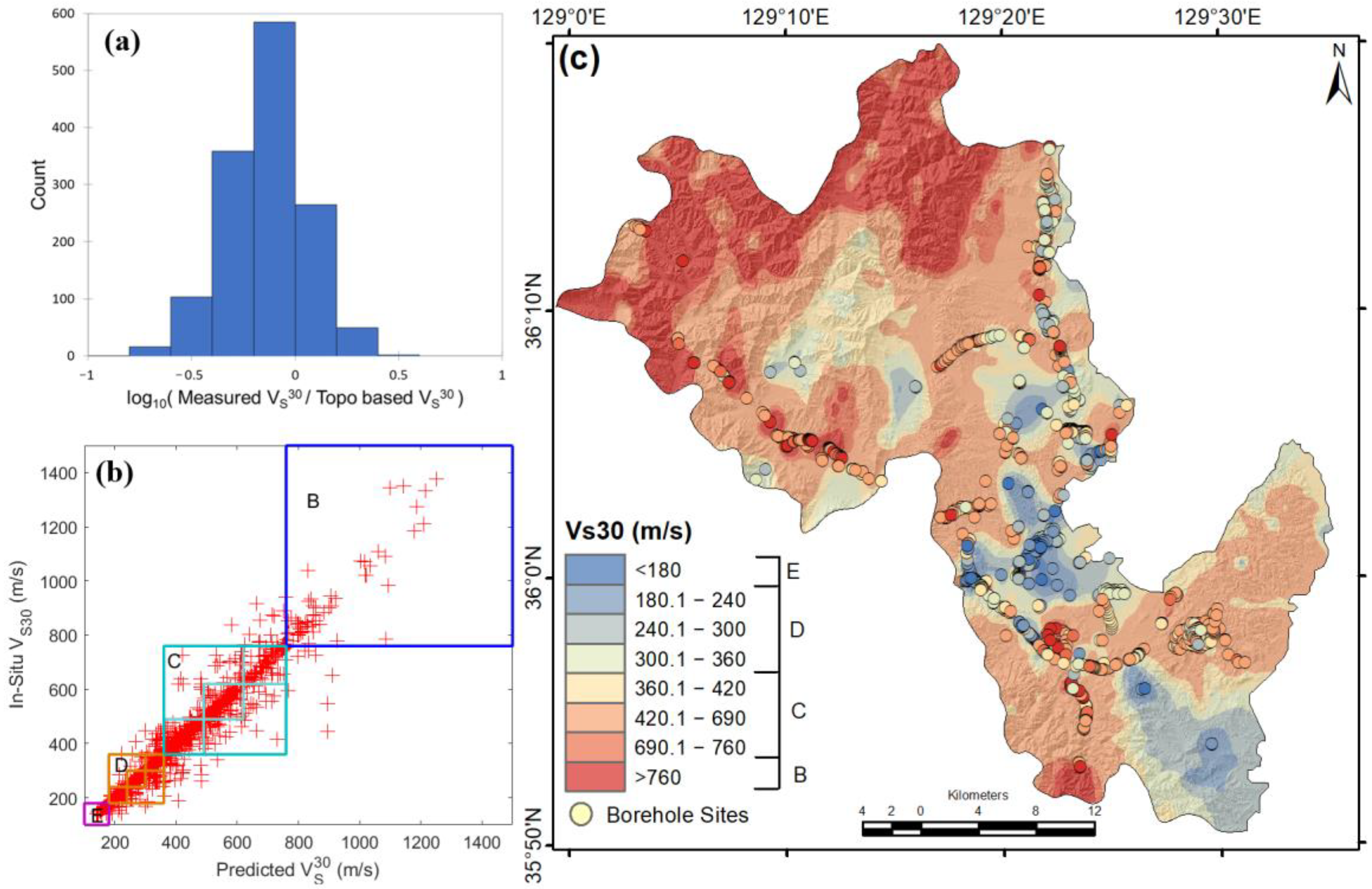

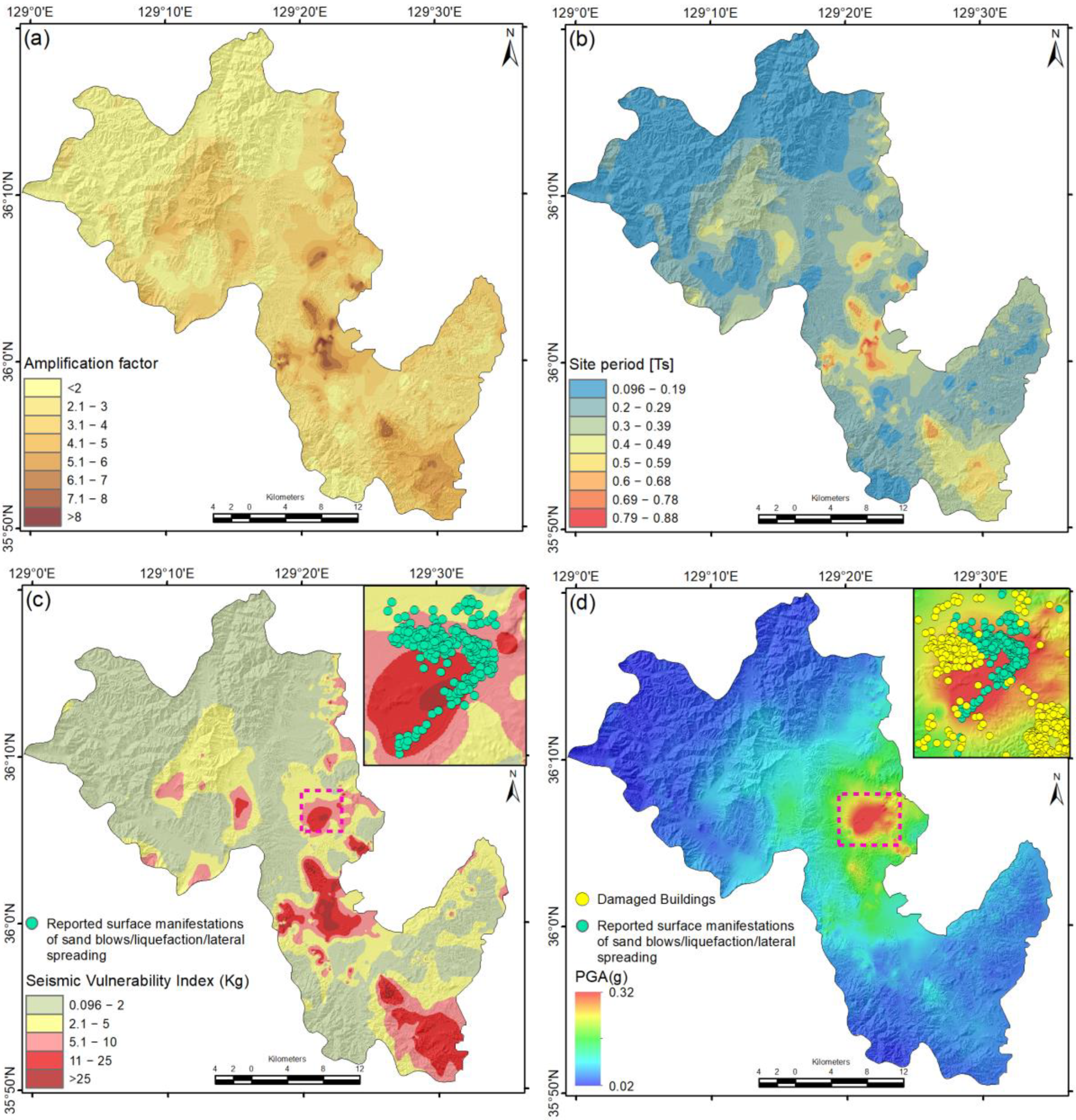

3.2.2. Influencing Factor Analysis (Geotechnical, Seismological, and Topographical)

3.2.3. Ground Settlement Susceptibility Analysis Using ML Models

3.2.4. Model Validation

4. Results

4.1. Spatial Distribution of PSInSAR-Derived VLM

4.2. Ground Settlement Susceptibility (GSS) Mapping

4.3. Structural Vulnerability Assessment Based on the Optimal GSS Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| AF | General Amplification Factor |

| APS | Atmospheric Phase Screen |

| ASI | Amplitude Stability Index |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GMPE | Ground Motion Prediction Equation |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| GSS | Ground Settlement Susceptibility |

| GSSM | Ground Settlement Susceptibility Zonation Map |

| IDW | Inverse Distance Weighted |

| IW | Interferometric Wide |

| Kg | Seismic Vulnerability Index |

| KRDA | Korea Rural Development Administration |

| LOS | Line of Sight |

| LPI | Liquefaction Potential Index |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| NEHRP | National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program |

| NGA | Next Generation Ground Motion Prediction Equation |

| NGII | National Geographic Information Institute |

| NSDI | Korea National Spatial Data Infrastructure |

| PGA | Peak Ground Acceleration |

| PS | Persistent Scatterers |

| PSInSAR | Persistent Scatterer Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| AUC–ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| SBAS | Small Baseline Subset |

| SLC | Single Look Complex |

| SPT | Standard Penetration Testing |

| TOPS | Terrain Observation with Progressive Scans |

| Ts | Site Period |

| VLM | Vertical Land Motion |

| Vs30 | Effective Shear-Wave Velocity |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Dhahir, M.K.; Nadir, W.; Rasool, M.H. Influence of Soil Liquefaction on the Structural Performance of Bridges During Earthquakes: Showa Bridge as A Case Study. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, W.; Song, M.S.; Adhikari, M.D.; Yum, S.G. Monitoring the Integrity and Vulnerability of Linear Urban Infrastructure in a Reclaimed Coastal City Using SAR Interferometry. Buildings 2025, 15, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaussard, E.; Amelung, F.; Abidin, H.; Hong, S.H. Sinking cities in Indonesia: ALOS PALSAR detects rapid subsidence due to groundwater and gas extraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 128, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.C.; Wei, M.; D’Hondt, S. Subsidence in coastal cities throughout the world observed by InSAR. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL098477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, C.; Lindsey, E.O.; Chin, S.T.; McCaughey, J.W.; Bekaert, D.; Nguyen, M.; Hua, H.; Manipon, G.; Karim, M.; Horton, B.P.; et al. Sea-level rise from land subsidence in major coastal cities. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral-Cano, E.; Dixon, T.H.; Miralles-Wilhelm, F.; Díaz-Molina, O.; Sánchez-Zamora, O.; Carande, R.E. Space geodetic imaging of rapid ground subsidence in Mexico City. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2008, 120, 1556–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, C.; Xu, H.; Hou, X. Spatial and temporal characteristics analysis for land subsidence in Shanghai coastal reclamation area using PS-InSAR method. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1000523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seed, H.B.; Idriss, I.M. Analysis of soil liquefaction: Niigata earthquake. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1967, 93, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Haq, A.; Hryciw, R.D. Ground settlement in Simi Valley following the Northridge earthquake. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 1998, 124, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ayala, D.; Free, M.; Bilham, R.; Doyle, P.; Evans, R.; Greening, P.; May, R.; Stewart, A.; Teymur, B.; Vince, D. The Kocaeli, Turkey Earthquake of 17 August 1999; Institution of Structural Engineers: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Karanth, R.V.; Sohoni, P.S.; Mathew, G.; Khadkikar, A.S. Geological observations of the 26 January 2001 Bhuj earthquake. J. Geol. Soc. India 2001, 58, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubrinovski, M.; Bradley, B.; Wotherspoon, L.; Green, R.; Bray, J.; Wood, C.; Pender, M.; Allen, J.; Bradshaw, A.; Rix, G.; et al. Geotechnical aspects of the 22 February 2011 Christchurch earthquake. Bull. New Zealand Soc. Earthq. Eng. 2011, 44, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokimatsu, K.; Tamura, S.; Suzuki, H.; Katsumata, K. Building damage associated with geotechnical problems in the 2011 Tohoku Pacific Earthquake. Soils Found. 2012, 52, 956–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Sun, C.G.; Cho, H.I. Geospatial assessment of the post-earthquake hazard of the 2017 Pohang earthquake considering seismic site effects. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gihm, Y.S.; Kim, S.W.; Ko, K.; Choi, J.-H.; Bae, H.; Hong, P.S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H.; Jin, K.; Choi, S.-J.; et al. Paleoseismological implications of liquefaction-induced structures caused by the 2017 Pohang Earthquake. Geosci. J. 2018, 22, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, S.P.; Gwon, O.; Park, K.; Kim, Y.S. Land damage mapping and liquefaction potential analysis of soils from the epicentral region of 2017 Pohang Mw 5.4 earthquake, South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.S.; Doan, N.P.; Nong, Z. Numerical prediction of settlement due to the Pohang earthquake. Earthq. Spectra 2021, 37, 652–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Kim, H.S.; Baise, L.G.; Kim, B. Geospatial liquefaction probability models based on sand boils occurred during the 2017 M5. 5 Pohang, South Korea, earthquake. Eng. Geol. 2024, 329, 107407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, S.P.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, T.; Su-Ho, J. Geological and structural control on localized ground effects within the Heunghae Basin during the Pohang Earthquake (MW 5.4, 15th November 2017), South Korea. Geosciences 2019, 9, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Ko, K.; Gihm, Y.S.; Cho, C.S.; Lee, H.; Song, S.G.; Bang, E.S.; Lee, H.J.; Bae, H.K.; Kim, S.W.; et al. Surface deformations and rupture processes associated with the 2017 Mw 5.4 Pohang, Korea, earthquake. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2019, 109, 756–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Ji, Y.; Kim, M.; Lee, Y.-J.; Kang, H.; Yun, N.-R.; Kim, H.; Lee, J. Building damage caused by the 2017 M5.4 Pohang, South Korea, earthquake, and effects of ground conditions. J. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 26, 3054–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, M.; Baise, L.G.; Kim, B. Local and regional evaluation of liquefaction potential index and liquefaction severity number for liquefaction-induced sand boils in Pohang, South Korea. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 141, 106459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Kim, B.; Bae, S.; Lee, H.; Kim, M. Earthquake-induced ground deformations in the low-seismicity region: A case of the 2017 M5. 4 Pohang, South Korea, earthquake. Earthq. Spectra 2019, 35, 1235–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, A.S.; Achmad, A.R.; Lee, C.W. Land subsidence measurement in reclaimed coastal land: Noksan using C-band sentinel-1 radar interferometry. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 102, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; Hong, S.H. Nonlinear modeling of subsidence from a decade of InSAR time series. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL090970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Kim, Y.J.; Chen, J.; Nam, B.H. InSAR-based investigation of ground subsidence due to excavation: A case study of Incheon City, South Korea. Int. J. Geo-Eng. 2024, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, D.; Chen, R.; Meadows, M.E.; Banerjee, A. Gaining or losing ground? Tracking Asia’s hunger for ‘new’coastal land in the era of sea level rise. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 732, 139290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.W.; Kong, S.M.; Lee, D.Y.; Yoo, Y.S.; Lee, Y.J. Effects of Reinforced Pseudo-Plastic Backfill on the Behavior of Ground around Cavity Developed due to Sewer Leakage. J. Korean Geoenvironmental Soc. 2015, 16, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Nam, J.; Park, J.; Hong, G. Numerical Analysis of Factors Influencing the Ground Surface Settlement above a Cavity. Materials 2022, 15, 8301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.S.; Park, Y.K.; Eum, K.Y. Stability assessment of roadbed affected by ground subsidence adjacent to urban railways. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 2261–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohenhen, L.O.; Zhai, G.; Lucy, J.; Werth, S.; Carlson, G.; Khorrami, M.; Onyike, F.; Sadhasivam, N.; Tiwari, A.; Ghobadi-Far, K.; et al. Land subsidence risk to infrastructure in US metropolises. Nat. Cities 2025, 2, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-García, G.; Ezquerro, P.; Tomás, R.; Béjar-Pizarro, M.; López-Vinielles, J.; Rossi, M.; Mateos, R.M.; Carreón-Freyre, D.; Lambert, J.; Teatini, P.; et al. Mapping the global threat of land subsidence. Science 2021, 371, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirzaei, M.; Freymueller, J.; Törnqvist, T.E.; Galloway, D.L.; Dura, T.; Minderhoud, P.S. Measuring, modelling and projecting coastal land subsidence. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wu, H.; Zhou, S.; Guo, D.; Chen, R. Land subsidence in coastal reclamation with impact on metro operation under rapid urbanization: A case study of Shenzhen. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 970, 179020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanjani, F.A.; Amelung, F.; Piter, A.; Sobhan, K.; Tavakkoliestahbanati, A.; Eberli, G.P.; Haghighi, M.H.; Motagh, M.; Milillo, P.; Mirzaee, S.; et al. Insar observations of construction-induced coastal subsidence on Miami’s barrier islands, Florida. Earth Space Sci. 2024, 11, e2024EA003852. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, W.; Zhou, X.; Wang, L.; Yao, Y. Using insar and polsar to assess ground displacement and building damage after a seismic event: Case study of the 2021 baicheng earthquake. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, D.; Yarrakula, K. InSAR based deformation mapping of earthquake using Sentinel 1A imagery. Geocarto Int. 2020, 35, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.W.; Kim, J.R.; Yoon, H.; Choi, Y.; Yu, J. Seismic surface deformation risks in industrial hubs: A case study from Ulsan, Korea, using DInSAR time series analysis. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy Vadivel, S.K.; Kim, D.J.; Jung, J.; Cho, Y.K.; Han, K.J.; Jeong, K.Y. Sinking tide gauge revealed by space-borne InSAR: Implications for sea level acceleration at Pohang, South Korea. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, R.; Lee, S.R.; Kwon, T.H. Long-term remote monitoring of ground deformation using sentinel-1 interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR): Applications and insights into geotechnical engineering practices. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; Xie, X.; Wang, C.; Tang, G.; Song, Z. Ground subsidence risk assessment method using PS-InSAR and LightGBM: A case study of Shanghai metro network. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2297842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Peng, M.; Motagh, M.; Guo, X.; Xing, M.; Quan, Y. Mapping susceptibility and risk of land subsidence by integrating InSAR and hybrid machine learning models: A case study in Xi’an, China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 3625–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadhillah, M.F.; Achmad, A.R.; Lee, C.W. Integration of InSAR time-series data and GIS to assess land subsidence along subway lines in the Seoul metropolitan area, South Korea. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Pan, B.; Afzal, Z.; Sajjad, M.M.; Kakar, N.; Ahmed, N.; Hussain, W.; Ali, M. SBAS-InSAR Analysis of tectonic derived ground deformation and subsidence susceptibility mapping via machine learning in Quetta City, Pakistan. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2441926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Xu, H.; Yao, Q.; Liu, Q.; Bricker, J.D.; Jonkman, S.N.; Yin, J.; Wang, J. Tracking 30-year evolution of subsidence in Shanghai utilizing multi-sensor InSAR and random forest modelling. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 140, 104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Singh, M.S.; Nayak, K.; Dutta, P.P.; Sarma, K.K.; Aggarwal, S.P. Earthquake Damage Susceptibility Analysis in Barapani Shear Zone Using InSAR, Geological, and Geophysical Data. Geosciences 2025, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, H.H.; Wang, C.; Chang, F.N.; Li, H.Z.; Tan, D.Y. Multi-temporal InSAR-based landslide dynamic susceptibility mapping of Fengjie County, Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaragunda, V.R.; Vaka, D.S.; Oikonomou, E. Land Subsidence Susceptibility Modelling in Attica, Greece: A Machine Learning Approach Using InSAR and Geospatial Data. Earth 2025, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Wu, L.; Hayakawa, Y.S.; Yin, K.; Gui, L.; Jin, B.; Guo, Z.; Peduto, D. Advanced integration of ensemble learning and MT-InSAR for enhanced slow-moving landslide susceptibility zoning. Eng. Geol. 2024, 331, 107436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Miao, F.; Wu, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gong, S.; Sun, D. Land subsidence susceptibility mapping in urban settlements using time-series PS-InSAR and random forest model. Gondwana Res. 2024, 125, 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Zeng, T.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Gui, L.; Yin, K.; Zhao, B. Advanced risk assessment framework for land subsidence impacts on transmission towers in salt lake region. Environ. Model. Softw. 2024, 177, 106058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S. Geospatial data-driven assessment of earthquake-induced liquefaction impact mapping using classifier and cluster ensembles. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 140, 110266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Miao, F.; Wu, Y.; Ke, C.; Gong, S.; Ding, Y. Refined landslide susceptibility mapping in township area using ensemble machine learning method under dataset replenishment strategy. Gondwana Res. 2024, 131, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiao, Y.Y.; He, L.L.; Tan, F.; Zhu, H.M.; Wei, H.L.; Zhang, Q.B. Susceptibility mapping and risk assessment of urban sinkholes based on grey system theory. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 152, 105893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Hong, T.K.; Rah, G. Seismic hazard assessment for the Korean Peninsula. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2021, 111, 2696–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.K.; Lee, J.; Park, S.; Kim, W. Major influencing factors for the nucleation of the 15 November 2017 Mw 5.5 Pohang earthquake. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2022, 323, 106833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Yang, W.S. Historical seismicity of Korea. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2006, 96, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seon, C.G.; Kim, H.S.; Cho, H.I. Investigation and analysis of Pohang Earthquake in Relation to Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Characteristics of Pohang Earthquake and Countermeasures for Geotechnical Structure, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 7 February 2018; Available online: https://www.ksce.or.kr/not/Default.asp?page=1&bidx=48219&sfield=>xt=&gbn=13&bcat=&ctop=&htop=&ptop=&idx=&bgbn=R (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Chough, S.K.; Kwon, S.T.; Ree, J.H.; Choi, D.K. Tectonic and sedimentary evolution of the Korean peninsula: A review and new view. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2000, 52, 175–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Choi, S.J. Identification of a suspected Quaternary fault in eastern Korea: Proposal for a paleoseismic research procedure for the mapping of active faults in Korea. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 113, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.J.; Shin, J.S.; Heo, T.Y.; Lee, J.L. Behavioral characteristics of the Yangsan fault based on geometric analysis. In Proceedings of the 1999 Autumn Meeting of the Korean Nuclear Society, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 29–30 October 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Nur, A.S.; Syifa, M.; Ha, M.; Lee, C.W.; Lee, K.Y. Improvement of Earthquake Risk Awareness and Seismic Literacy of Korean Citizens through Earthquake Vulnerability Map from the 2017 Pohang Earthquake, South Korea. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, R.F. Radar Interferometry: Data Interpretation and Error Analysis; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Zhou, L.; Lee, H. Ground displacement variation around power line corridors on the loess plateau estimated by persistent scatterer interferometry. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 87908–87917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirui, P.; Oiro, S.; Waithaka, H.; Odera, P.; Riedel, B.; Gerke, M. Detection, characterization, and analysis of land subsidence in Nairobi using InSAR. Nat. Hazards 2022, 113, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Perissin, D.; Bai, J. Investigations on the coregistration of Sentinel-1 TOPS with the conventional cross-correlation technique. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Hong, T.K. A national Vs30 model for South Korea to combine nationwide dense borehole measurements with ambient seismic noise analysis. Earth Space Sci. 2022, 9, e2021EA002066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.I.; Wald, D.J. On the use of high-resolution topographic data as a proxy for seismic site conditions (VS30). Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2009, 99, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.A. Seismic microzonation map of Syria using topographic slope and characteristics of surface soil. Nat. Hazards 2016, 80, 1323–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y. Seismic vulnerability indices for ground and structures using microtremor. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Railway Research, Florence, Italy, 16–19 November 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sil, A.; Sitharam, T.G. Detection of Local Site Conditions in Tripura and Mizoram Using the Topographic Gradient Extracted from Remote Sensing Data and GIS Techniques. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2017, 18, 04016009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emolo, A.; Sharma, N.; Festa, G.; Zollo, A.; Convertito, V.; Park, J.; Chi, H.; Lim, I. Ground-motion prediction equations for South Korea Peninsula. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2015, 105, 2625–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, A.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F. Permanent scatterers in SAR interferometry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perissin, D.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T. The SARPROZ InSAR tool for urban subsidence/man-made structure stability monitoring in China. In Proceedings of the 34th International Symposium on Remote Sensing of Environment, ISRSE, Sidney, Australia, 10–15 April 2011; p. 1015. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Chen, F.; Zhou, W. A comparative case study of MTInSAR approaches for deformation monitoring of the cultural landscape of the Shanhaiguan section of the Great Wall. Herit. Sci. 2021, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhi, M.; An, Y. Revealing large-scale surface subsidence in Jincheng City’s mining clusters using MT-InSAR and VMD-SSA-LSTM time series prediction model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, R.A.; Lee, G.J.; Choi, S.K.; Kwon, T.H.; Kim, Y.C.; Ryu, H.H.; Kim, S.; Bae, B.; Hyun, C. Monitoring of construction-induced urban ground deformations using Sentinel-1 PS-InSAR: The case study of tunneling in Dangjin, Korea. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 108, 102721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Pan, B.; Afzal, Z.; Ali, M.; Zhang, X.; Shi, X.; Ali, M. Landslide detection and inventory updating using the time-series InSAR approach along the Karakoram Highway, Northern Pakistan. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Wang, C.; Hu, C.; Luo, X. PS-ESD: Persistent scatterer-based enhanced spectral diversity approach for time-series Sentinel-1 TOPS data co-registration. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshlahjeh Azar, M.; Hamedpour, A.; Maghsoudi, Y.; Perissin, D. Analysis of the deformation behavior and sinkhole risk in Kerdabad, Iran using the PS-InSAR method. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, M.D.; Park, S.; Yum, S.G. Coastal vulnerability to extreme weather events: An integrated analysis of erosion, sediment movement, and land subsidence based on multi-temporal optical and SAR satellite data. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 374, 124025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Chu, T.; Tissot, P.; Holland, S. Sentinel-1 InSAR-derived land subsidence assessment along the Texas Gulf Coast. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 125, 103544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorrami, M.; Abrishami, S.; Maghsoudi, Y.; Alizadeh, B.; Perissin, D. Extreme subsidence in a populated city (Mashhad) detected by PSInSAR considering groundwater withdrawal and geotechnical properties. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fárová, K.; Jelének, J.; Kopačková-Strnadová, V.; Kycl, P. Comparing DInSAR and PSI techniques employed to Sentinel-1 data to monitor highway stability: A case study of a massive Dobkovičky landslide, Czech Republic. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.A.; Chen, Z.; Shoaib, M.; Shah, S.U.; Khan, J.; Ying, Z. Sentinel-1A for monitoring land subsidence of coastal city of Pakistan using Persistent Scatterers In-SAR technique. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Kim, D.J.; Palanisamy Vadivel, S.K.; Yun, S.H. Long-term deflection monitoring for bridges using X and C-band time-series SAR interferometry. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chen, J.; Valseth, E.; Wells, G.; Bettadpur, S.; Jones, C.E.; Dawson, C. Subtle land subsidence elevates future storm surge risks along the gulf coast of the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2024, 129, e2024JF007858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, M.D.; Song, M.S.; Yum, S.G. The impact of climate change and localized land subsidence along the Korean Peninsula Coastline: An Overview of future coastal inundation and vulnerability. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 144, 104894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzanga, B.; Bekaert, D.P.; Hamlington, B.D.; Kopp, R.E.; Govorcin, M.; Miller, K.G. Localized uplift, widespread subsidence, and implications for sea level rise in the New York City metropolitan area. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadi8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Choi, M.; Park, S.C. Ground vulnerability derived from the horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio: Comparison with the damage distribution caused by the 2017 ML 5.4 Pohang earthquake, Korea. Near Surf. Geophys. 2021, 19, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, D.J.; Allen, T.I. Topographic slope as a proxy for seismic site conditions and amplification. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2007, 97, 1379–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, M.; Hussain, M.L.; Khan, M.A.; van der Meijde, M.; Khan, S. Geology as a proxy for Vs30-based seismic site characterization, a case study of northern Pakistan. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilder, C.E.; De Risi, R.; De Luca, F.; Mohan Pokhrel, R.; Vardanega, P.J. Geostatistical framework for estimation of VS30 in data-scarce regions. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2022, 112, 2981–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, G.; Okalp, K.; Kockar, M.K.; Yilmaz, M.T.; Jalehforouzan, A.; Temiz, F.A.; Askan, A.; Akgun, H.; Erberik, M.A. Development of a GIS-Based Predicted-VS 30 Map of Türkiye Using Geological and Topographical Parameters: Case Study for the Region Affected by the 6 February 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2024, 95, 2044–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, H.; Anbazhagan, P. Geology, geomorphology and Vs30-based site classification of the Himalayan region using a stacked model. Eng. Geol. 2025, 355, 108229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borcherdt, R.D. Estimates of site-dependent response spectra for design (methodology and justification). Earthq. Spectra 1994, 10, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBC 2006. International Building Code; International Code Council, Inc.: Country Club Hills, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.T.; Boore, D.M.; Stokoe, K.H. Comparison of shear-wave slowness profiles at 10 strong-motion sites from noninvasive SASW measurements and measurements made in boreholes. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2002, 92, 3116–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, P.M. Introduction to Seismology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Boore, D.M.; Joyner, W.B. Site amplifications for generic rock sites. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1997, 87, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mase, L.Z.; Sugianto, N. Seismic hazard microzonation of Bengkulu City, Indonesia. Geo-Environ. Disasters 2021, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.C.; Tseng, Y.S. Characteristics of soil liquefaction using H/V of microtremors in Yuan-Lin area, Taiwan. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2002, 13, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, B. Assessment of seismic vulnerability using the horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio (HVSR) method in Haenam, Korea. Geosci. J. 2020, 25, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.P.; Shukla, A.; Kumar, M.R.; Thakkar, M.G. Characterizing Surface Geology, Liquefaction Potential, and Maximum Intensity in the Kachchh Seismic Zone, Western India, through Microtremor Analysis Characterizing Surface Geology, Liquefaction Potential, and Maximum Intensity in the Kachchh Seismic Zone. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2017, 107, 1277–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choobbasti, A.; Naghizaderokni, M.; Naghizaderokni, M. Reliability analysis of soil liquefaction based on standard penetration: A case study in Babol city. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Sustainable Civil Engineering (ICSCE 2015), Chengdu, China, 19–20 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani, J.; Enner. Unraveling the Ground Subsidence Disaster Caused by Rock Salt Mining in Maceió (Northeast Brazil) from 2020 Until Rupture Using Sentinel-1 Data. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3826573/v1 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Youd, T.L.; Perkins, D.M. Mapping liquefaction-induced ground failure potential. J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 1978, 104, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, G.P.; Rajawat, A.S. Evaluation of liquefaction potential hazard of Chennai city, India: Using geological and geomorphological characteristics. Nat. Hazards 2012, 64, 1717–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Hernández, E.; Chunga, K.; Toulkeridis, T.; Pastor, J.L. Soil liquefaction and other seismic-associated phenomena in the city of Chone during the 2016 Earthquake of Coastal Ecuador. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Cao, L.; Li, S.; Ye, F.; Boloorani, A.D.; Liang, Z.; Huang, J.; Liu, G. Multisource geoscience data-driven framework for subsidence risk assessment in urban area. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 113, 104901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, H.; Sun, D.; Zhu, X.; Ji, Q.; Wen, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, R. A heterogeneous ensemble landslide susceptibility assessment method based on InSAR and geographic similarity extended landslide inventory. Gondwana Res. 2025, 144, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.H.; Larocque, D. Robustness of random forests for regression. J. Nonparametric Stat. 2012, 24, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, H. The multicollinearity effect on the performance of machine learning algorithms: Case examples in healthcare modelling. Acad. Platf. J. Eng. Smart Syst. 2024, 12, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Lin, Y.; Liaw, B.; Kerby, L. Evaluation of tree based regression over multiple linear regression for non-normally distributed data in battery performance. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Intelligent Data Science Technologies and Applications (IDSTA), San Antonio, TX, USA, 5–7 September 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, M.D.; Yum, S.G.; Yune, C.Y. Geospatial-based risk analysis of solar plants located in the mountainous region of Gangwon Province, South Korea. Renew. Energy 2025, 251, 123408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A.; Hill, J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 0-521-86706-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tuganishuri, J.; Yune, C.Y.; Kim, G.; Lee, S.W.; Adhikari, M.D.; Yum, S.G. Prediction of the volume of shallow landslides due to rainfall using data-driven models. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 25, 1481–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; He, T.; Benesty, M.; Khotilovich, V.; Tang, Y.; Cho, H.; Chen, K.; Mitchell, R.; Cano, I.; Zhou, T.; et al. xgboost: Extreme Gradient Boosting. R Package Version 1.6.0.1. 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=xgboost (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Arabameri, A.; Saha, S.; Roy, J.; Chen, W.; Blaschke, T.; Tien Bui, D. Landslide susceptibility evaluation and management using different machine learning methods in the Gallicash River Watershed, Iran. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabi, H.; Hashim, M. Landslide susceptibility mapping using GIS-based statistical models and Remote sensing data in tropical environment. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, L.; Yamagishi, H.; Marui, H.; Kanno, T. Landslides in Sado Island of Japan: Part II. GIS-based susceptibility mapping with comparisons of results from two methods and verifications. Eng. Geol. 2005, 81, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaro, G.; Koseki, J. Liquefaction and Failure Mechanisms of Sandy Sloped Ground during Earthquakes: A Comparison between Laboratory and Field Observations. In Proceedings of the Australian Earthquake Engineering Society Conference 2012, Gold Coast, Australia, 7–9 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dashti, S.; Bray, J.D.; Pestana, J.M.; Riemer, M.; Wilson, D. Mechanisms of seismically induced settlement of buildings with shallow foundations on liquefiable soil. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 2010, 136, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElGharbawi, T.; Tamura, M. Increasing spatial coverage in rough terrain and vegetated areas using InSAR optimized pixel selection: Application to Tohoku, Japan. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 25, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, S.; Xu, L.; Peng, J. Monitoring and stability analysis of the deformation in the Woda landslide area in Tibet, China by the DS-InSAR method. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.S.; Inoue, T.; Lee, S.L. Hyperbolic method for consolidation analysis. J. Geotech. Eng. 1991, 117, 1723–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Sources | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Sentinel-1SLC ascending orbit data | https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 27 March 2024) | Multi-temporal SLC Data (total images = 56), acquired between February 2017 and December 2023; Incident angle ~39.2243° |

| Building Inventories | NSDI (Korea National Spatial Data Infrastructure) | Building footprints |

| Digital Elevation Model (DEM) | National Geographic Information Institute (NGII); USGS | 5 × 5 m LiDAR DEM; 90 m SRTM DEM |

| Soil Depth | Korea Rural Development Administration (KRDA) | Digital soil map |

| Geotechnical Data | Kim and Hong [67] | In situ effective shear wave velocity (Vs30) distribution |

| Regional Site Class Map | https://earthquake.usgs.gov/data/vs30/ (accessed on 15 August 2025) | Topography gradient-based Vs30 |

| Liquefaction/sand boils/lateral spreading Sites | Gihm et al. [15]; Kim et al. [22]; Kang et al. [23]; Seon et al. [58] | Surface manifestations of Liquefaction/sand boils/lateral spreading due to the 2017 Pohang earthquake |

| Reported building damaged | Kim et al. [21] | Building damage caused by the 2017 Pohang earthquake |

| Datasets | RFAUC | DTAUC | XGBoostAUC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training | 0.918 | 0.846 | 0.916 |

| Testing | 0.914 | 0.836 | 0.907 |

| Difference (%) | 0.4% | 1.2% | 0.9% |

| Average | 0.916 | 0.841 | 0.912 |

| ML Models | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.89 |

| XGBoost | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.88 |

| DT | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.93 | 0.85 |

| GSS Zones | Spatial Extent of Susceptibility Levels (km2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| RF Model | DT Model | XGBoost Model | |

| Very Low | 657.83 | 557.79 | 692.32 |

| Low | 141.61 | 215.16 | 113.38 |

| Moderate | 101.56 | 150.30 | 78.67 |

| High | 98.69 | 79.94 | 94.62 |

| Very High | 136.75 | 133.24 | 157.44 |

| GSS Zones | Pi (%) | Oi (%) | R-Index | P | MSE | MAE | RMSE | Accuracy (Cutoff = 0.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Low | 57.9 | 5.5 | 1.03 | 81.9 | 0.176 | 0.33 | 0.419 | 73.99 |

| Low | 12.5 | 12.5 | 10.9 | |||||

| Moderate | 8.9 | 17.2 | 20.8 | |||||

| High | 8.7 | 24.2 | 30.2 | |||||

| Very High | 12.0 | 40.47 | 36.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, W.; Song, M.-S.; Yum, S.-G.; Adhikari, M.D. Ground Settlement Susceptibility Assessment in Urban Areas Using PSInSAR and Ensemble Learning: An Integrated Geospatial Approach. Buildings 2025, 15, 4364. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234364

Jeong W, Song M-S, Yum S-G, Adhikari MD. Ground Settlement Susceptibility Assessment in Urban Areas Using PSInSAR and Ensemble Learning: An Integrated Geospatial Approach. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4364. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234364

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, WoonSeong, Moon-Soo Song, Sang-Guk Yum, and Manik Das Adhikari. 2025. "Ground Settlement Susceptibility Assessment in Urban Areas Using PSInSAR and Ensemble Learning: An Integrated Geospatial Approach" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4364. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234364

APA StyleJeong, W., Song, M.-S., Yum, S.-G., & Adhikari, M. D. (2025). Ground Settlement Susceptibility Assessment in Urban Areas Using PSInSAR and Ensemble Learning: An Integrated Geospatial Approach. Buildings, 15(23), 4364. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234364