Possibilities for the Utilization of Recycled Aggregate from Railway Ballast

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aggregate from Railway Ballast

2.2. Cement, Additives, Water

2.3. Determination of Grain Size and Shape Index

2.4. Determination of Harmful Substances

2.4.1. Solid Phase

2.4.2. Water Extract–Cement Matrix

- OAA-06-01A, based on EPA method No. 6010, using an inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer, ICP-AES SPECTRO ARCOS (determination of Ba, Be, Cd, Cr, Cu, Mo, Ni, Pb, and Zn);

- OAA-05-01A, based on US EPA methods and using an atomic absorption spectrometer with flame atomization, FL-AAS, UNICAM 969 (for control analysis of selected concentrations of aqueous extracts);

- OAA-05-02A, based on US EPA methods and using an atomic absorption spectrometer with electrothermal atomization, contrAA 800D (determination of As, Sb, and Se);

- OAA-05-04, based on the procedures described in the operating instructions for the atomic absorption spectrometer for the determination of Hg, ALTEC, type AMA 254 (determination of Hg);

- OOA-80-15, based on US EPA method No. 1011B using a WATERS ion chromatograph, conductivity detectors, and UV/VIS (determination of anions—chlorides, fluorides, and sulfates).

2.5. Methodology for Testing Concrete Properties

2.5.1. Determination of Fresh Concrete Mixture Properties

2.5.2. Bulk Density of Hardened Concrete

2.5.3. Determination of Resistance to Water Pressure

2.5.4. Determination of Strength Characteristics

2.5.5. Image Analysis

2.6. Designing the Recipes

- R250—This is a recipe based on waste from recycled railway ballast, represented by fr. 0/25 mm (100%). CEM I 42.5 R (250 kg per m3), water (311 kg per m3), and a plasticizing additive in the amount of 0.9% of the cement weight are used as binders.

- R400—This is a recipe based on recycled railway ballast waste, represented by fr. 0/25 mm (100%). CEM I 42.5 R (400 kg per m3), water (358 kg per m3), and a plasticizing additive in an amount of 0.8% of the cement weight are used as binders.

- R250N—This is a recipe based on waste from excavated platforms, represented by fr. 0/32 mm (55%), and natural aggregate 0/4 mm (45%). CEM I 42.5 R (250 kg per m3), water (174 kg per m3), and a plasticizing additive in an amount of 0.9% of the cement weight are used as a binder.

- R400N—This is a recipe based on waste from excavated platforms, represented by fr. 0/32 mm (55%) and 0/4 mm (45%). CEM I 42.5 R (400 kg per m3), water (257 kg per m3), and a plasticizing additive in an amount of 0.8% of the cement weight are used as binders.

2.7. Production of Test Specimens

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Determination of Grain Size and Shape Index

3.2. Determination of Harmful Substances—Solid Phase

- 01/24 Gravel from railway superstructure waste after recycling fr. 0/25 mm (used for recipes R250 and R400).

- 02/24 Gravel from railway superstructure from platform layers fr. 0/32 mm (used for recipes R250N and R400N).

3.3. Fresh Concrete Properties

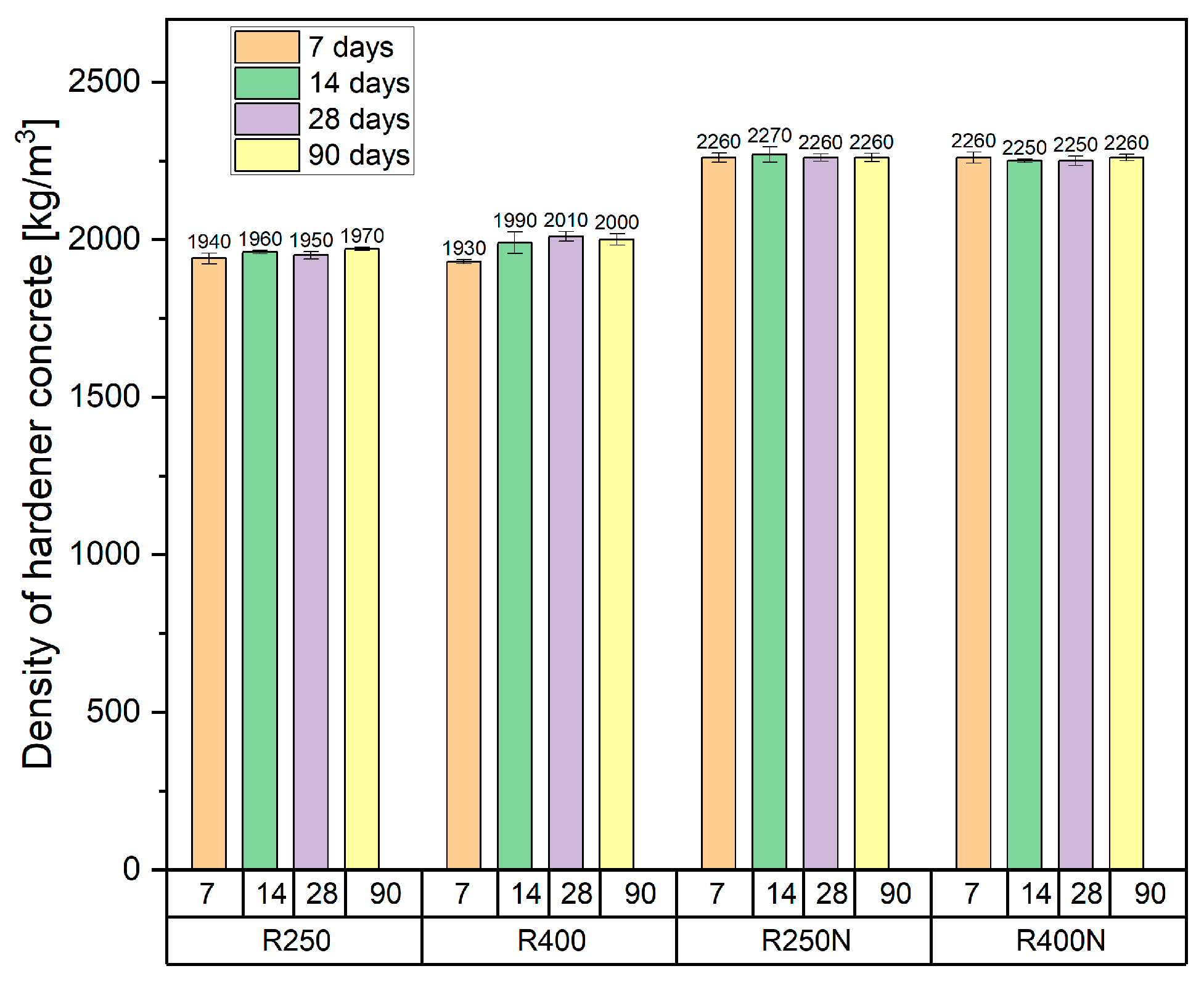

3.4. Determination of the Bulk Density of Hardened Concrete

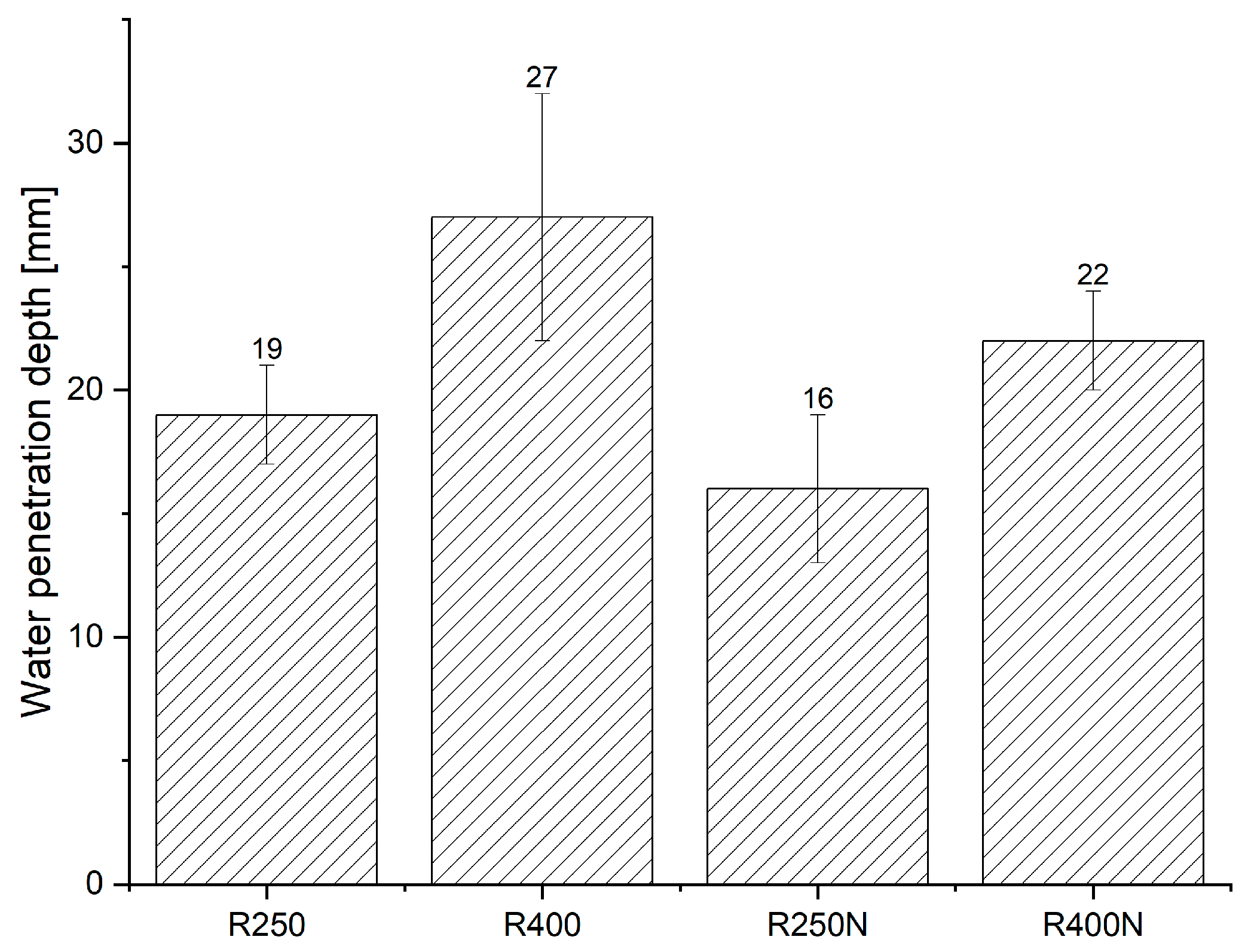

3.5. Determination of Resistance to Water Pressure

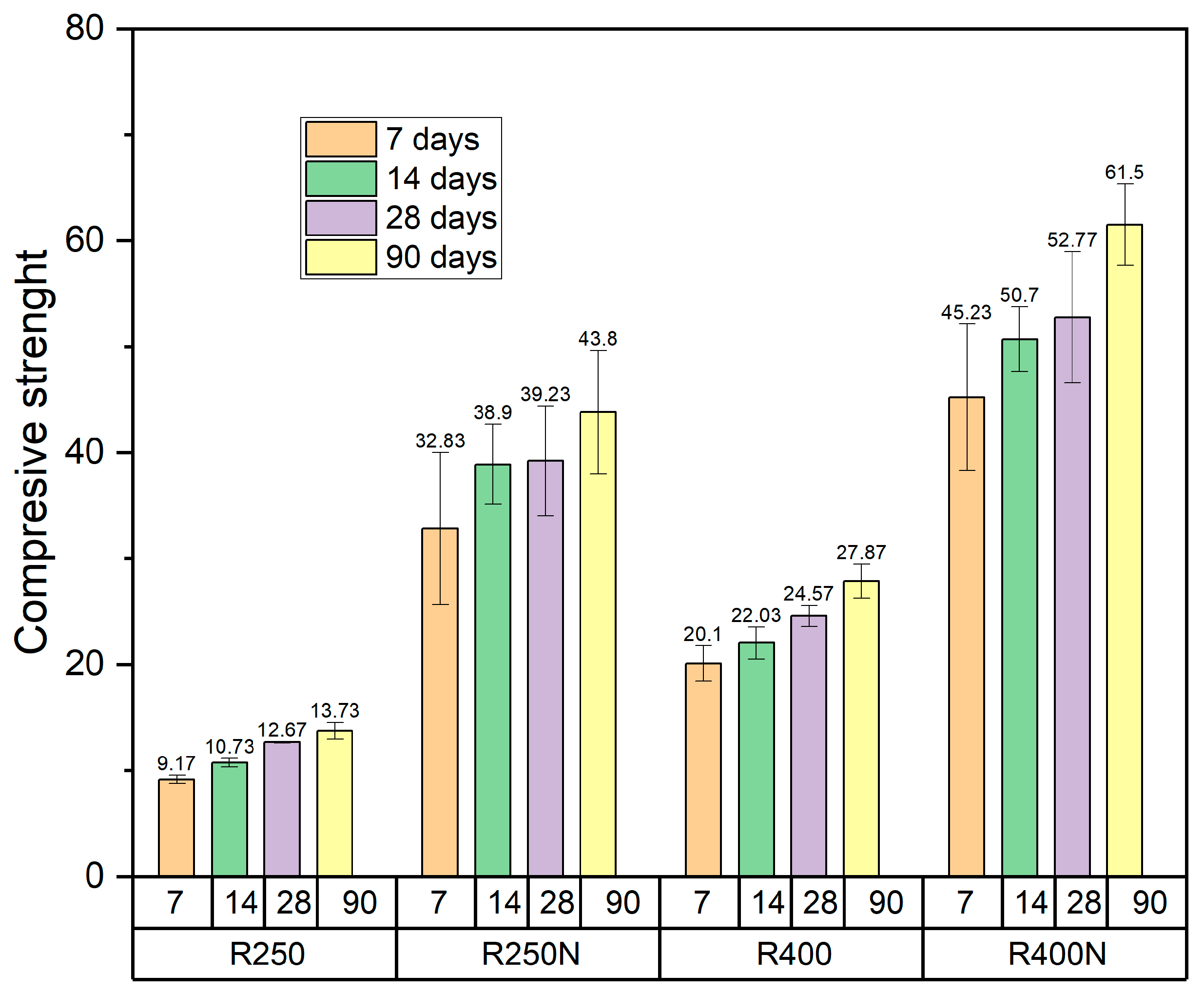

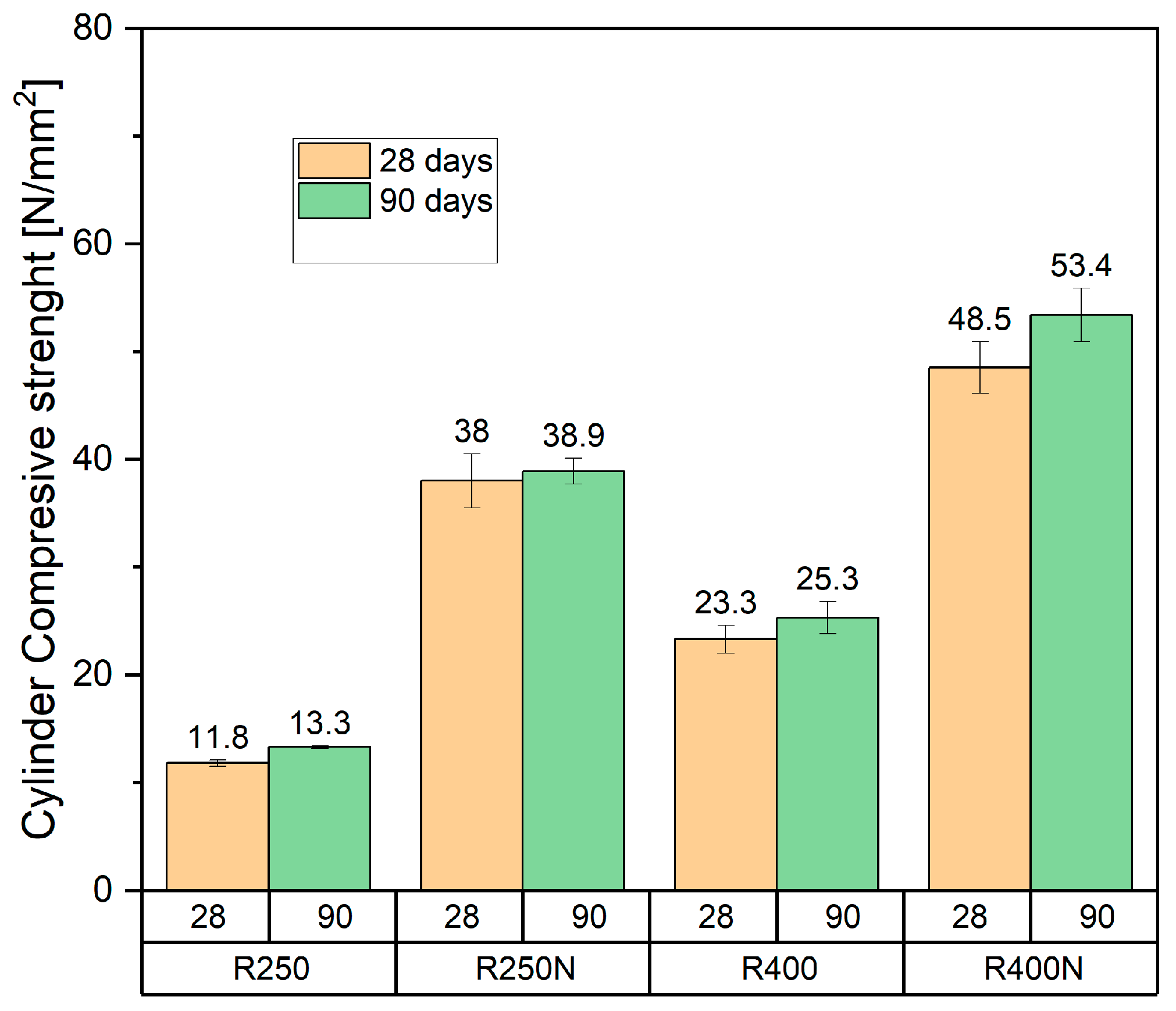

3.6. Strength Characteristics of Concrete

- At the same cement dosage, the mixture with the 0/32 mm recycled aggregate had a statistically significantly higher strength than the mixture with the 0/25 mm aggregate (p < 0.001).

- Increasing the cement dosage from 250 to 400 kg/m3 led to a significant increase in strength for both types of aggregate (p < 0.01).

- The effect of increasing the cement was more pronounced in the mixture with the 0/32 mm recycled aggregate than in the mixture with the 0/25 mm aggregate.

- This supplementary statistical analysis thus quantitatively supports the main conclusions of the study on the importance of suitable aggregate composition and cement dosage optimization to achieve a higher strength in recycled concrete.

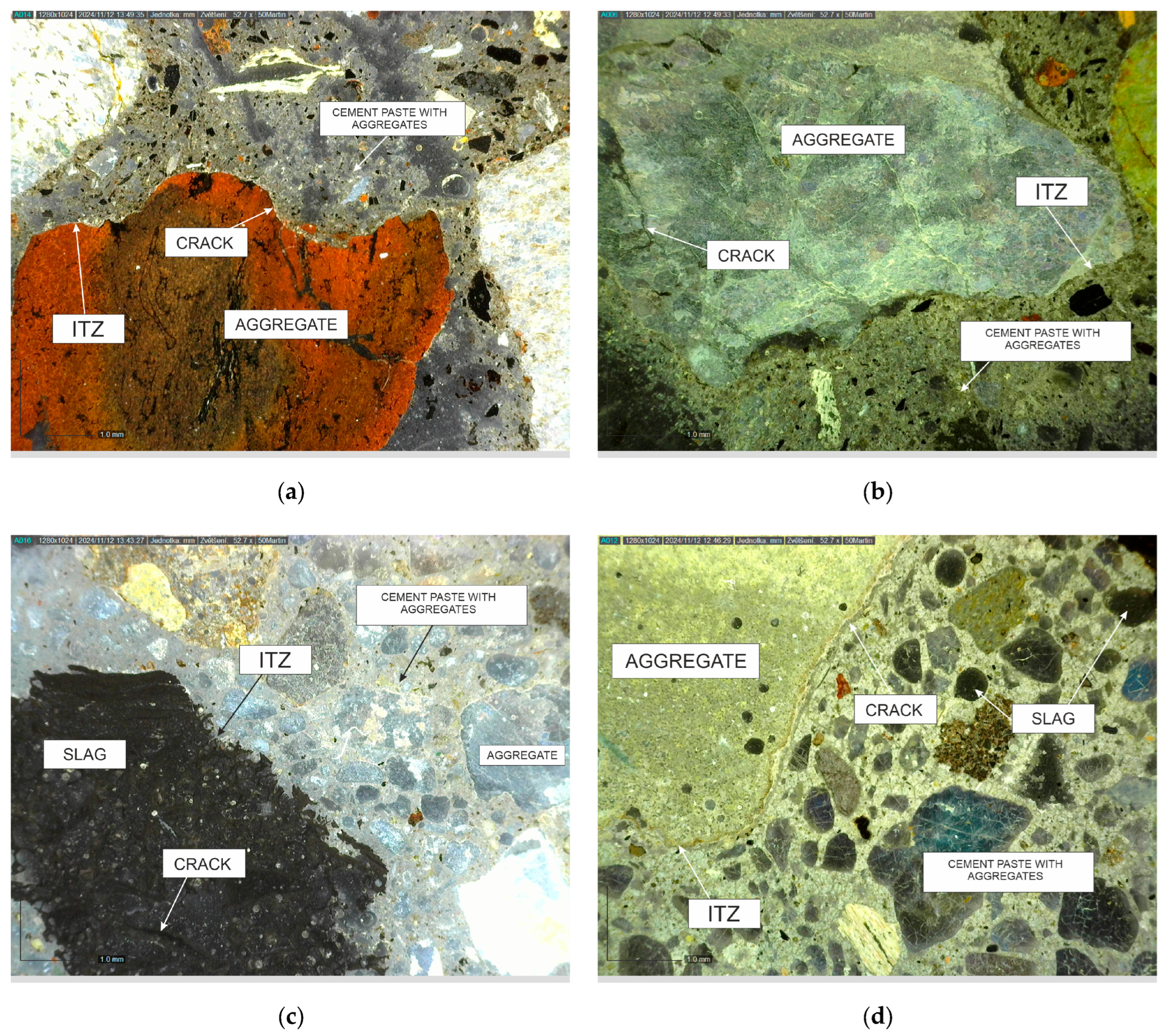

3.7. Image Analysis of Concrete

3.8. Content of Harmful Substances in Concrete Water Leachate

4. Conclusions

- Mixtures with a fr. 0/25 mm aggregate from railway ballast recycling achieved lower bulk densities (R250 = 1950 kg/m3, R400 = 2100 kg/m3), which reflect the presence of fine particles that impair the compaction of the mixture. On the contrary, mixtures with recycled material from platforms (0/32 mm) achieved values close to those of conventional structural concrete (R250N = 2260 kg/m3, R400N = 2250 kg/m3), which indicate a more compact structure and a more suitable grain size distribution.

- The 28-day strengths clearly showed the significant influence of the type of recycled material used. Concrete with the recycled aggregate fr. 0/25 mm (R250 and R400) achieved significantly lower strength values, even with a higher cement dosage (400 kg/m3), while R250N concrete with a lower cement content (250 kg/m3) showed a comparable or higher strength. The best results were achieved with concrete containing recycled material from the platform, 0/32, with the addition of 0/4 natural sand, where the R400N formula exceeded 50 MPa, proving that optimized recycled material granulometry in combination with a cement matrix can achieve parameters close to those of conventional structural concrete. The testing of railway ballast concrete with a fraction of 0/32 without the addition of a natural sand fraction of 0/4 was not performed.

- The R250 mixture achieves only low strengths, corresponding to the strength class of C8/10, and is more suitable for non-structural applications. The R250N mixture shows strengths of classes C25/30 to C30/37, which are commonly used for reinforced concrete elements in building construction. The R400 mixture consistently corresponds to strength class C16/20, which is applicable for foundations and less stressed structures. The highest strengths were achieved with the R400N mixture, which achieves strength classes of C35/45 to C45/55 and is intended for highly stressed structures and civil engineering works.

- The average penetration depth after 28 days was 19–27 mm for concrete with an undersized aggregate and 16–22 mm for concrete with the recycled platform aggregate. The results confirm that the fine undersized aggregate increases the porosity and thus the permeability of concrete, while the coarser recycled aggregate supplemented with sand creates a more compact base with better watertightness.

- All concrete mixtures showed a weakened transition zone (ITZ) between the grain and the cement matrix, as well as the presence of microcracks in the paste. These phenomena are typical for concretes with recycled fillers, but the overall structure of the composites remained stable and without major defects.

- The cement matrix reliably retained hazardous substances, and leaching tests demonstrated their complete stabilization, as none of the monitored indicators exceeded the specified legislative limits.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yücel, H.E.; Dutkiewicz, M.; Yıldızhan, F. The Effect of Waste Ballast Aggregates on Mechanical and Durability Properties of Standard Concrete. Materials 2023, 16, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.W.Y.; Soomro, M.; Evangelista, A.C.J. A Review of Recycled Aggregate in Concrete Applications (2000–2017). Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 172, 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indraratna, B.; Qi, Y.; Malisetty, R.S.; Navaratnarajah, S.K.; Mehmood, F.; Tawk, M. Recycled Materials in Railroad Substructure: An Energy Perspective. Railw. Eng. Sci. 2022, 30, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xie, J.; Fan, Z.; Markine, V.; Connolly, D.P.; Jing, G. Railway Ballast Material Selection and Evaluation: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 344, 128218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozioł: Kruszywa w Budownictwie. Cz. 1. Kruszywa Naturalne. Available online: https://bibliotekanauki.pl/articles/364015.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Hussain, A.; Hussaini, S.K.K. Use of Steel Slag as Railway Ballast: A Review. Transp. Geotech. 2022, 35, 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Nimbalkar, S.; Singh, S.; Choudhury, D. Field Assessment of Railway Ballast Degradation and Mitigation Using Geotextile. Geotext. Geomembr. 2020, 48, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rak, A.; Klosok-Bazan, I.; Zimoch, I.; Machnik-Slomka, J. Analysis of Railway Ballast Contamination in Terms of Its Potential Reuse. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 378, 134440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz-Aja, J.; Carrascal, I.; Polanco, J.A.; Thomas, C.; Sosa, I.; Casado, J.; Diego, S. Self-Compacting Recycled Aggregate Concrete Using out-of-Service Railway Superstructure Wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sañudo, R.; Goswami, R.R.; Ricci, S.; Miranda, M. Efficient Reuse of Railway Track Waste Materials. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagüe García, S.; González Gaya, C. Reusing Discarded Ballast Waste in Ecological Cements. Materials 2019, 12, 3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, I.; Wee, G.N.; No, J.H.; Lee, T.K. Pollution Level and Reusability of the Waste Soil Generated from Demolition of a Rural Railway. Environ. Pollut. Barking Essex 1987 2018, 240, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, A. Treatments for the Improvement of Recycled Aggregate. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2004, 16, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P. Methods for Improving the Durability of Recycled Aggregate Concrete: A Review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 6367–6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Palma, L.; Petrucci, E. Treatment and Recovery of Contaminated Railway Ballast. Turk. J. Eng. Environ. Sci. 2014, 38, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech Geological Survey. Mineral Commodity Resources of the Czech Republic—Non-Metallic Minerals, Edition 2024 (Status 2023); Czech Geological Survey: Prague, Czech Republic, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ČSN EN 197-1 Ed. 2; Cement—Part 1: Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2012.

- ČSN EN 1008; Mixing Water for Concrete—Specification for Sampling, Testing and Assessing the Suitability of Water, Including Water Recovered from Processes in the Concrete Industry. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2003.

- Heidelberg Materials CZ, a.s. Aggregate Test Report—Grain-Size Distribution of Aggregate Fraction 0/4 Mm, Tovačov Quarry. Betotech Ltd., Accredited Testing Laboratory No. 1195.3, Mokrá–Horákov, Czech Republic, 2025. Available online: https://www.heidelbergmaterials.cz/system/files/2025-07/Tovacov_0-4_2025_TT.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- ČSN EN 12620+A1; Aggregates for Concrete. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2009.

- ČSN EN 933-1; Tests for Geometrical Properties of Aggregates—Part 1: Determination of Particle Size Distribution—Sieving Method. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2012.

- ČSN EN 933-2; Tests for Geometrical Properties of Aggregates—Part 2: Determination of Particle Shape—Flakiness Index. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2012.

- ČSN EN 933-4; Tests for Geometrical Properties of Aggregates—Part 4: Determination of Shape Index. Czech Technical Standard: Prague, Czech Republic, 2008.

- Decree No. 273/2021 Coll.; On the Details of Waste Management. Ministry of the Environment: Prague, Czech Republic, 2021.

- ČSN EN 12350-2; Testing Fresh Concrete—Part 2: Slump Test. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2019.

- ČSN EN 12350-7; Testing Fresh Concrete—Part 7: Air Content—Pressure Methods. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2019.

- ČSN EN 12350-6; Testing Fresh Concrete—Part 6: Density. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2019.

- ČSN EN 12390-2; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 2: Making and Curing Specimens for Strength Tests. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2019.

- ČSN EN 12390-7; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 7: Density of Hardened Concrete. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2019.

- ČSN EN 12390-8; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 8: Depth of Penetration of Water under Pressure. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2019.

- ČSN EN 12390-3; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 3: Compressive Strength of Test Specimens. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2019.

- Knaack, A.M.; Kurama, Y.C. Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Beams with Recycled Concrete Coarse Aggregates. J. Struct. Eng. 2015, 141, B4014009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Setién, J.; Polanco, J.A.; Alaejos, P.; Sánchez de Juan, M. Durability of Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 40, 1054–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, H.; Kurda, R.; Kurda, R.; Al-Hadad, B.; Mustafa, R.; Ali, B. A Critical Review on the Influence of Fine Recycled Aggregates on Technical Performance, Environmental Impact and Cost of Concrete. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi, I.G.; Beushausen, H.; Alexander, M.G. Multi-Technique Approach to Enhance the Properties of Fine Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 893852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Taboada, I.; González-Fonteboa, B.; Martínez-Abella, F.; Carro-López, D. Study of Recycled Concrete Aggregate Quality and Its Relationship with Recycled Concrete Compressive Strength Using Database Analysis. Mater. Constr. 2016, 66, e089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, C.; Gaddo, V. Mechanical and Durability Characteristics of Concrete Containing EAF Slag as Aggregate. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2009, 31, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, C.; Cavagnis, P.; Faleschini, F.; Brunelli, K. Properties of Concretes with Black/Oxidizing Electric Arc Furnace Slag Aggregate. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 37, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, F.; Harun, M.; Ahmed, A.; Kabir, N.; Khalid, H.R.; Hanif, A. Influence of Bonded Mortar on Recycled Aggregate Concrete Properties: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 432, 136564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, C.; Liu, L.; Lu, X.; Zhu, D.; Sun, Y.; Yu, L.; OuYang, Y.; Cao, X.; Wei, Q. The Durability of Recycled Fine Aggregate Concrete: A Review. Materials 2022, 15, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosa, M.E.; Zega, C.J.; Di Maio, A.A. Understanding the Influence of Properties of Fine Recycled Aggregates on Recycled Concrete. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Constr. Mater. 2020, 176, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-H.; Gjorv, O.E. Permeability of High-Strength Lightweight Concrete. Mater. J. 1991, 88, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ČSN P 73 2404:2024; Concrete—Specification, Performance, Production and Conformity—Additional Information. Czech Technical Standard: Prague, Czech Republic, 2024.

- ČSN EN 206+A2; Concrete—Specification, Performance, Production and Conformity. Czech Technical Standard: Prague, Czech Republic, 2021.

- Faleschini, F.; Brunelli, K.; Zanini, M.A.; Dabalà, M.; Pellegrino, C. Electric Arc Furnace Slag as Coarse Recycled Aggregate for Concrete Production. J. Sustain. Metall. 2016, 2, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Wei, H.; Yang, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C. Effect of Mixed Recycled Aggregate on the Mechanical Strength and Microstructure of Concrete under Different Water Cement Ratios. Materials 2021, 14, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bosque, I.S.; Zhu, W.; Howind, T.; Matías, A.; De Rojas, M.S.; Medina, C. Properties of Interfacial Transition Zones (ITZs) in Concrete Containing Recycled Mixed Aggregate. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 81, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.S.; Shui, Z.H.; Lam, L. Effect of Microstructure of ITZ on Compressive Strength of Concrete Prepared with Recycled Aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2004, 18, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, W.; Sun, Z.; Lange, D.A.; Shah, S.P. Properties of Interfacial Transition Zones in Recycled Aggregate Concrete Tested by Nanoindentation. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 37, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xiao, J.; Sun, Z.; Kawashima, S.; Shah, S.P. Interfacial Transition Zones in Recycled Aggregate Concrete with Different Mixing Approaches. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 35, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Wang, Z. A Review of the Interfacial Transition Zones in Concrete: Identification, Physical Characteristics, and Mechanical Properties. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 300, 109979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Recycled Aggregate Source | Collection Location (Date) | Sample Collection and Preparation Procedure | Use in Mixes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Railway ballast (0/25 mm) | Reconstruction of the Havířov railway junction (3 July 2024) | The gravel was extracted from the switch using an excavator and sorted into 0/25 mm and 25/65 mm fractions on a Mc Closkey R155 sorting machine (Mc Closkey, Keene, Canada). The fine fraction was then transported to the laboratory for analysis. | Used in R250, R400 |

| Platform waste (0/32 mm) | Various station platforms, Havířov (11 July 2024) | Samples of the subbase layers under the platform were taken using an excavator, with samples taken from various locations and loaded onto a truck. The sample was then taken to the laboratory for subsequent analysis. | Used in R250N, R400N |

| Na2O | MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | SO3 | Cl | K2O | CaO | Fe2O3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEM I 42.5R SUPERCEMENT | 2.52 | 3.82 | 4.29 | 19.31 | 3.18 | 0.07 | 0.53 | 56.62 | 3.30 |

| Type of Cement | Water Demand [wt.%] | Initial Setting Time [min.] | Final Setting Time [min.] | Specific Surface [cm2·g−1] | Bulk Density [g·cm−3] | Compressive Strength [MPa] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Days | 28 Days | ||||||

| CEM I 42.5R SUPERCEMENT | 26.6 | 192 | 271 | 3670 | 3.13 | 29.7 | 59.5 |

| Bulk Density [kg/m3] | pH | Dry Matter Content [w.%] | Chloride Content [w.%] | Equivalent of Na2O [hm.%] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sika ViscoCrete-4035 | 1060 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 33 | ≤0.1 | ≤1.0 |

| Components | Recipe R250 | Recipe R400 | Recipe R250N | Recipe R400N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [kg per m3] | [kg per m3] | [kg per m3] | [kg per m3] | |

| Cement CEM I 42.5 R SUPERCEMENT, Cement Hranice, a.s. | 250.00 | 400.00 | 250.00 | 400.00 |

| Natural aggregate 0/4 mm Tovačov | 0.00 | 0.00 | 831.00 | 677.00 |

| Railway ballast aggregate 0/25—waste after recycling | 1297 | 1082.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Railway ballast aggregate 0/32—platform waste | 0.00 | 0.00 | 896.00 | 730.00 |

| Additives—plasticizer | 2.25 | 3.20 | 2.25 | 3.21 |

| Water | 311 | 358.00 | 174.00 | 257.00 |

| Aggregate fraction | 0/25 mm | 10/32 mm |

| SI value | 19 | 31 |

| Indicator | 01/24 [mg/kg Dry Matter] | 02/24 [mg/kg Dry Matter] | I. Limit Value * [mg/kg Dry Matter] | II. Limit Value * [mg/kg Dry Matter] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | 19.3 | <1 | 10 | 30 |

| Cd | 1 | <1 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Cr total | 266 | 98 | 100 | 200 |

| Hg | 0.063 | 0.014 | 0.8 | 1 |

| Ni | 68.6 | 12.5 | 65 | 80 |

| Pb | 43.5 | 25.9 | 100 | 200 |

| V | 122 | 205 | 180 | 180 |

| Cu | 121 | 38 | 100 | 170 |

| Zn | 142 | 29.5 | 300 | 600 |

| Ba | 1030 | 7460 | 600 | 600 |

| Be | 3.77 | 2.26 | 5 | 5 |

| Hydrocarbons C10–C40 | 130 | <50 | 200 | 300 |

| Benzene | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Total PAH | <0.05 | <0.05 | 3 | 6 |

| PCB | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.2 |

| EOX | <1 | <1 | 1 | 2 |

| Result | R250 | R400 | R250N | R400N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slump test [mm] | 100 | 126 | 40 | 170 |

| Bulk density [kg/m3] | 1950 | 1990 | 2270 | 2270 |

| Air content [%] | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Mixture | Slump [mm] | Slump Class | w/c | Plasticizer [% of Weight of Cement] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R250 | 100 | S2 | 1.244 | 0.9% |

| R400 | 126 | S3 | 0.895 | 0.8% |

| R250N | 40 | S1 | 0.696 | 0.9% |

| R400N | 170 | S4 | 0.643 | 0.8% |

| Mixture | Slump [mm] | n | Mean [mm] | SD (%) | VC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R250 | 91···105···102 | 3 | 100 | 13 | 13.0 |

| R400 | 118···122···138 | 3 | 126 | 15 | 11.9 |

| R250N | 37···43···41 | 3 | 40 | 11 | 27.5 |

| R400N | 171···167···173 | 3 | 170 | 16 | 9.4 |

| Mixture | Air Content (%) | n | Mean | SD (%) | VC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R250 | 2.2···2.4···2.6 | 3 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 8.3 |

| R400 | 2.1···2.3···2.5 | 3 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 8.7 |

| R250N | 2.0···2.4···2.5 | 3 | 2.3 | 0.265 | 11.5 |

| R400N | 2.1···2.4···2.4 | 3 | 2.3 | 0.173 | 7.5 |

| Mixture | Bulk Density of Fresh Concrete [kg/m3] | n | Mean | SD (%) | VC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R250 | 1890···1961···1997 | 3 | 1950 | 42 | 2.2 |

| R400 | 1995···1961···2010 | 3 | 1990 | 38 | 1.9 |

| R250N | 2290···2242···2280 | 3 | 2270 | 20 | 0.9 |

| R400N | 2275···2251···2290 | 3 | 2270 | 50 | 2.2 |

| Mixture | Water Penetration [mm] | Max [mm] | Median [mm] | Mean [mm] | CV [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R250 | 22, 17, 18 | 22 | 18 | 19 | 13.90 |

| R400 | 30, 25, 26 | 30 | 26 | 27 | 9.80 |

| R250N | 19, 16, 12 | 19 | 16 | 16 | 22.40 |

| R400N | 28, 19, 20 | 28 | 20 | 22 | 21.20 |

| Mixture | Age [Days] | n | Mean [MPa] | SD | CV [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R250 | 7 | 3 | 9.17 | 0.4 | 4.4 |

| 14 | 3 | 10.73 | 0.42 | 3.9 | |

| 28 | 3 | 12.67 | 0.06 | 0.5 | |

| 90 | 3 | 13.73 | 0.8 | 5.8 | |

| R250N | 7 | 3 | 32.83 | 7.16 | 21.8 |

| 14 | 3 | 38.9 | 3.76 | 9.7 | |

| 28 | 3 | 39.23 | 5.17 | 13.2 | |

| 90 | 3 | 43.8 | 5.84 | 13.3 | |

| R400 | 7 | 3 | 20.1 | 1.66 | 8.3 |

| 14 | 3 | 22.03 | 1.52 | 6.9 | |

| 28 | 3 | 24.57 | 0.99 | 4.0 | |

| 90 | 3 | 27.87 | 1.6 | 5.7 | |

| R400N | 7 | 3 | 45.23 | 6.92 | 15.3 |

| 14 | 3 | 50.7 | 3.05 | 6.0 | |

| 28 | 3 | 52.77 | 6.2 | 11.7 | |

| 90 | 3 | 61.5 | 3.86 | 6.3 |

| Mixture | Age [Days] | n | Mean [MPa] | SD | CV [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R250 | 28 | 3 | 11.8 | 0.3 | 2.5 |

| 90 | 3 | 13.3 | 0.1 | 0.8 | |

| R250N | 28 | 3 | 38 | 2.5 | 6.6 |

| 90 | 3 | 38.9 | 1.2 | 3.1 | |

| R400 | 28 | 3 | 23.3 | 1.3 | 5.6 |

| 90 | 3 | 25.3 | 1.5 | 5.9 | |

| R400N | 28 | 3 | 48.5 | 2.4 | 4.9 |

| 90 | 3 | 53.4 | 2.5 | 4.7 |

| Mixture | Strength Class After 28 Days | Strength Class After 90 Days |

|---|---|---|

| R250 | C8/10 | C8/10 |

| R400 | C16/20 | C20/25 |

| R250N | C25/30 | C30/37 |

| R400N | C35/45 | C45/55 |

| Effects | F(1, 20) | p | Partial η2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggregate type (0/25 vs. 0/32 + sand) | 2328 | <0.001 | 0.99 |

| Cement quantity (250 vs. 400 kg/m3) | 752 | <0.001 | 0.97 |

| Interaction (Typ × Cement) | 17.3 | <0.001 | 0.46 |

| Simple effects | |||

| – Cement: 250 vs. 400 (with 0/25 aggregate) | – | <0.001 | – |

| – Cement: 250 vs. 400 (with 0/32 aggregate + sand) | – | <0.001 | – |

| – Aggregate: 0/25 vs. 0/32 + sand (with 250 kg of cement) | – | <0.001 | – |

| – Aggregate: 0/25 vs. 0/32 + sand (with 400 kg of cement) | – | <0.001 | – |

| Indicator | R250 | R400 | R250N | R400N | I | IIa | IIb | III |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample no. | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L |

| DOC | unsp. | unsp. | unsp. | unsp. | 50.000 | 80.000 | 80.000 | 100.000 |

| Monohydric phenols | unsp. | unsp. | unsp. | unsp. | 0.100 | |||

| Chlorides | 1.858 | 1.894 | 0.762 | 0.665 | 80.000 | 1500.000 | 1500.000 | 5000.000 |

| Fluorides | 0.040 | 0.013 | 0.028 | <0.02 | 1.000 | 30.000 | 15.000 | 50.000 |

| Sulfates | 13.886 | 8.524 | 5.516 | 3.730 | 100.000 | 3000.000 | 2000.00 | 5000.000 |

| As | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | 0.050 | 2.500 | 0.200 | 2.500 |

| Ba | 0.019 | 0.038 | 0.155 | 0.145 | 2.000 | 30.000 | 10.000 | 30.000 |

| Cd | <0.004 | <0.004 | <0.004 | <0.004 | 0.004 | 0.500 | 0.100 | 0.500 |

| Cr total | <0.030 | <0.030 | <0.030 | <0.030 | 0.050 | 7.000 | 1.000 | 7.000 |

| Cu | 0.029 | <0.030 | <0.030 | <0.030 | 0.200 | 10.000 | 5.000 | 10.000 |

| Hg | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.200 | 0.020 | 0.200 |

| Ni | <0.030 | <0.030 | <0.030 | <0.030 | 0.040 | 4.000 | 1.000 | 4.000 |

| Pb | <0.030 | <0.030 | <0.030 | <0.030 | 0.050 | 5.000 | 1.000 | 5.000 |

| Sb | <0.006 | <0.006 | <0.006 | <0.006 | 0.006 | 0.500 | 0.070 | 0.500 |

| Se | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.010 | 0.700 | 0.050 | 0.700 |

| Zn | <0.030 | <0.030 | <0.030 | <0.030 | 0.400 | 20.000 | 5.000 | 20.000 |

| Mo | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | 0.050 | 3.000 | 1.000 | 3.000 |

| SS (sol. substances) | 232.600 | 310.400 | 106.000 | 128.800 | 400.000 | 8000.000 | 6000.000 | 10,000.000 |

| pH | 11.244 | 11.488 | 11.044 | 11.198 | ≥6.000 | ≥6.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Halík, M.; Dvorský, T.; Václavík, V.; Široký, T.; Eštoková, A.; Hospodárová, V.; Kępys, W.; Jaš, M. Possibilities for the Utilization of Recycled Aggregate from Railway Ballast. Buildings 2025, 15, 4361. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234361

Halík M, Dvorský T, Václavík V, Široký T, Eštoková A, Hospodárová V, Kępys W, Jaš M. Possibilities for the Utilization of Recycled Aggregate from Railway Ballast. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4361. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234361

Chicago/Turabian StyleHalík, Martin, Tomáš Dvorský, Vojtěch Václavík, Tomáš Široký, Adriana Eštoková, Viola Hospodárová, Waldemar Kępys, and Martin Jaš. 2025. "Possibilities for the Utilization of Recycled Aggregate from Railway Ballast" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4361. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234361

APA StyleHalík, M., Dvorský, T., Václavík, V., Široký, T., Eštoková, A., Hospodárová, V., Kępys, W., & Jaš, M. (2025). Possibilities for the Utilization of Recycled Aggregate from Railway Ballast. Buildings, 15(23), 4361. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234361