1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of the global energy crisis, the photovoltaic industry has experienced rapid development. Due to the shortage of land for PV power plant construction and the demands of specific application scenarios, cable-supported PV systems [

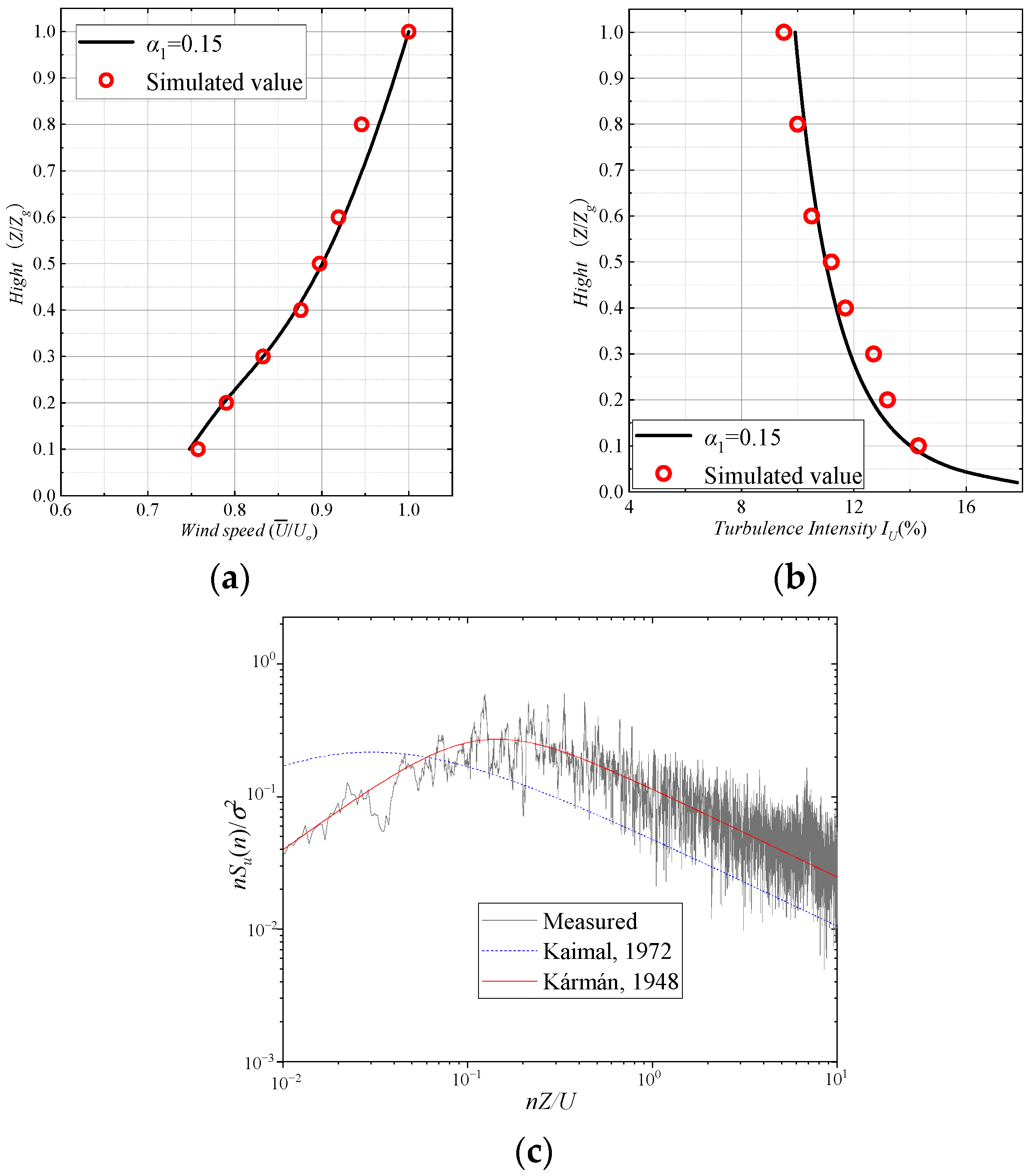

1] have been widely adopted in engineering projects. Traditional fixed supports not only consume substantial amounts of steel but also struggle to adapt to complex environments and terrains. In contrast, cable-supported PV systems, which support the photovoltaic modules via cables fixed between end columns, offer exceptional terrain adaptability. This configuration enables large-span arrangements while significantly reducing the required number of supporting components such as columns. However, these systems are characterized by large module dimensions, long spans, and low structural stiffness. Furthermore, as they are typically deployed in array configurations, they are highly susceptible to WIV, which can lead to extensive damage across the PV array.

Figure 1 shows field documentation of wind-induced damage to the cable-supported PV array, collected by the author during an investigation following the landfall of Typhoon Yagi in Hainan, China, in 2024.

Scholars worldwide have conducted extensive research on the wind loads affecting PV arrays. These studies have consistently identified significant interference effects between PV supports, which are influenced by factors such as module tilt angle, wind direction, ground clearance, and row spacing. Bitsuamlak [

2] employed numerical simulations to investigate the wind loads on both isolated and tandem PV modules, finding distinct differences between the two configurations. The significant interference effects generated in tandem arrangements substantially reduced the wind loads on adjacent panels. Abiola-Ogedengbe [

3] performed wind tunnel tests on a PV module comprising 24 components, revealing that the tilt angle, wind direction, and inter-panel gaps significantly affect the magnitude and distribution of surface pressures on PV modules. Shademan [

4] utilized numerical simulations to analyze the influence of longitudinal spacing, lateral gap spacing, ground clearance, and wind direction on the overall wind loads acting on PV panels. Jubayer [

5], using three-dimensional numerical simulations, found that the maximum wind loads typically occur near the leading edge of the modules. He also observed that the mean pressure distribution and wake structure exhibited symmetry characteristics along the flow centerline. Studies focusing solely on the wind loads of isolated modules or single-row supports are insufficient. Numerous researchers have investigated the interference effects on wind loads within PV arrays using rigid model pressure measurement tests and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations. These studies demonstrate that tilt angle, wind direction, array spacing, and structural configuration are all significant factors influencing the interference effects. Through rigid model pressure tests, Ginger [

6], Browne [

7], and Yemenici [

8] studied the interference effects on PV array wind loads. They concluded that the shielding effect becomes more pronounced with larger tilt angles, and the wind load stabilizes after the third row. Based on these interference effects, they provided recommendations for shape factor values, suggesting that different zones be designed according to varying wind load distributions. Warsido [

9] investigated the impact of shielding effects on both the wind load and wind-induced vibration of PV arrays, finding that leeward modules consistently experience lower wind loads than windward modules due to shielding, resulting in different wind-induced vibration responses for modules at different positions within the array. Ma [

10], conducting rigid pressure-measurement wind tunnel tests on multi-row PV supports, found that the interference effect manifested as a shielding effect on the mean pressure and torque coefficients of the solar tracker array, which was more significant at larger tilt angles. Regarding the fluctuating components, the interference effect showed a shielding effect at small tilt angles but an amplification effect at large tilt angles. Xu [

11] used numerical simulations to study the wind loads on multi-row PV supports, finding that support height and row spacing both influence the standard deviations of pressure and torque coefficients. Furthermore, vortex shedding from the PV supports affects the wind load fluctuations on the module surfaces, with pronounced vortex shedding observed at larger tilt angles, consistent with the findings of Suárez [

12]. Given that the WIV of cable-supported PV arrays is caused by fluctuating wind loads, it is reasonable to infer that significant interference effects are also present during their WIV response.

Existing research has revealed that cable-supported PV systems can undergo large-amplitude WIV, with forced vibrations caused by fluctuating wind loads at low wind speeds and self-excited vibrations induced by aerodynamic instabilities at high wind speeds being the most common. This phenomenon is influenced by numerous factors. To this end, Feltrin [

13] and Kim [

14] investigated the effects of sag, wind direction, inflow conditions, and wind speed on the WIV of single-row cable-supported systems through aeroelastic model wind tunnel tests. Their studies found that the fluctuating displacement of PV supports is closely related to factors such as the sag-to-span ratio, wind speed, and wind direction. Under certain conditions, these cable-supported systems experience self-excited vibrations due to fluid–structure interaction effects. Wu [

15] studied the effects of wind direction, PV module tilt angle, initial prestress of the stability cable, and flow field on the WIV response characteristics of a single-row cable-supported system. It was found that an increase in the tilt angle leads to a decrease in the critical wind speed; an increase in the initial prestress can raise the critical wind speed, but the effect is not significant; and the critical wind speed in a turbulent flow field is approximately 30% higher than that in a uniform flow field. The instability vibration was identified as a result of multi-mode coupling involving vertical bending and torsion. Xu [

16] employed aeroelastic and rigid model wind tunnel tests to study the WIV characteristics of a single-row cable-supported system. The wind-induced vertical vibration of the PV modules increased with a larger tilt angle and decreased with higher pre-tension force; the fluctuating displacement exhibited a quadratic increase with wind speed. Zhu [

17] used CFD numerical simulations to study the effect of tilt angle on the WIV of cable-supported systems. The results showed that as the tilt angle increased from 0° to 60°, the displacement wind-induced vibration coefficient ranged from 1.70 to 1.93, indicating that the influence of the tilt angle on the wind vibration coefficient must be considered in practical engineering design. However, cable-supported PV systems are typically deployed in large-scale arrays, where significant differences in wind load exist between rows. Vibration suppression measures are sometimes adopted to enhance the overall stability of the array, but these are not always implemented in mountainous or certain complex terrains. He [

18] conducted aeroelastic model wind tunnel tests on a double-layer cable-supported PV system and found that WIV initiates at relatively low wind speeds, with the amplitude increasing with wind speed. The windward modules and those at a 180° wind direction experienced greater vibration, with torsional vibration being stronger than vertical vibration. The study verified that adding inter-row connections effectively reduces the WIV of PV modules. Zhang [

19] investigated the WIV characteristics and shielding effects of a double-layer cable-supported PV array through aeroelastic wind tunnel tests. The research demonstrated that the WIV of the first row in the array is significantly greater than that of the downstream rows. The maximum WIV occurs when the wind direction is perpendicular to the supporting cables and the modules are subjected to wind suction. Within a certain range, a larger initial tilt angle of the PV modules leads to greater WIV. Ding [

20] studied the effects of shielding and wind direction on the WIV of a cable-supported PV array through wind tunnel tests. The WIV of PV modules in the central and leeward regions was significantly weaker than that in the windward region. Within the array, the windward modules provide a shielding effect for the downstream modules. The wind direction of the incoming flow also significantly affects the WIV of the structure, with crosswind directions (0° and 180°) producing the strongest WIV and being identified as the most critical conditions. The vibration amplitude decreases almost linearly as the wind direction deviates from the perpendicular. Yang [

21] studied the interference effects in a cable-supported PV array and conducted a comparative analysis with the vibration of a single-row support. The results indicated that both single-row and multi-row PV modules experience flutter instability as wind speed increases. Vertical vortex-induced vibration was observed in the multi-row array at low wind speeds prior to the onset of flutter instability, with the middle row exhibiting the most significant response. In summary, existing research has primarily focused on the aeroelastic response of individual cable-supported PV supports or simplified arrays. There remains a lack of in-depth understanding of the interference mechanisms governing the overall wind-induced response of multi-row cable-supported PV arrays. Li [

22] conducted wind tunnel tests on a sectional model of a cable-supported PV support system to investigate the critical flutter wind speeds at various tilt angles. Their study confirmed that installing a central stabilizer fin does not enhance the critical flutter wind speed. Chen [

23] performed aeroelastic model wind tunnel tests on a cable-supported PV support structure. Using a single-row model, they examined the aerodynamic stability under different tilt angles, wind directions, and both uniform and turbulent flow fields. Furthermore, with an array model, they investigated the interference effects resulting from varying wind directions, the number of PV supports, and the interconnections between adjacent PV modules. In summary, no study has yet clearly and systematically revealed how key design parameters, such as tilt angle and sag-to-span ratio, influence the interference effects, particularly their distinct impacts on the mean and fluctuating response components.

To address the unclear mechanisms of interference effects based on wind-induced responses in cable-supported photovoltaic arrays, this study investigates the interference effects on the WIV of an eight-row cable-supported PV array through aeroelastic wind tunnel tests. The research analyzes the influence of tilt angle, sag-to-span ratio, wind direction, and wind speed on the WIV characteristics of the array. An interference factor is defined for both the mean and fluctuating components of the displacement response for each row of the cable-supported PV array, aiming to elucidate the underlying interference mechanisms governing the wind-induced vibrations in such systems.

3. WIV Characteristics of Cable-Supported PV Array

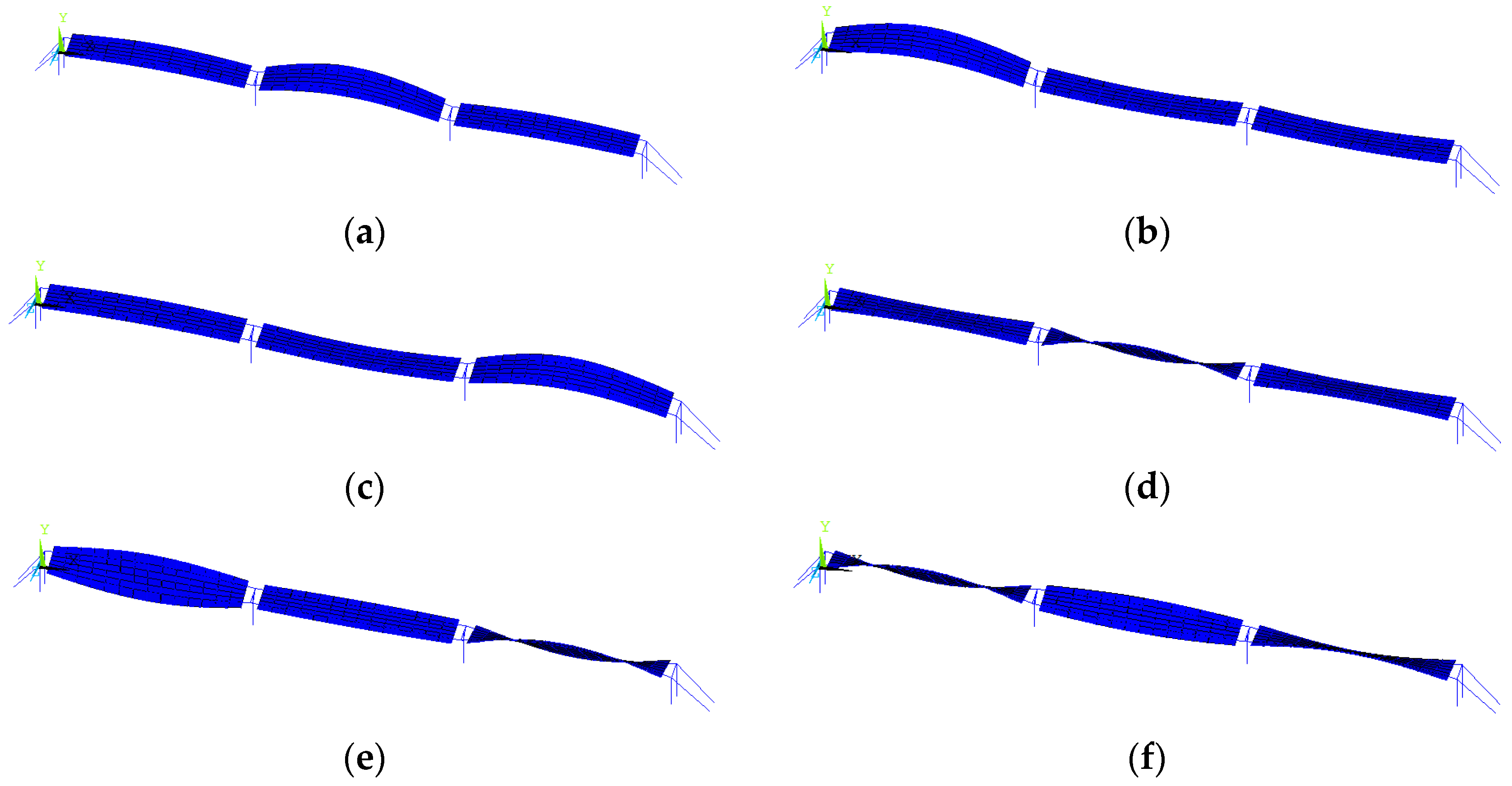

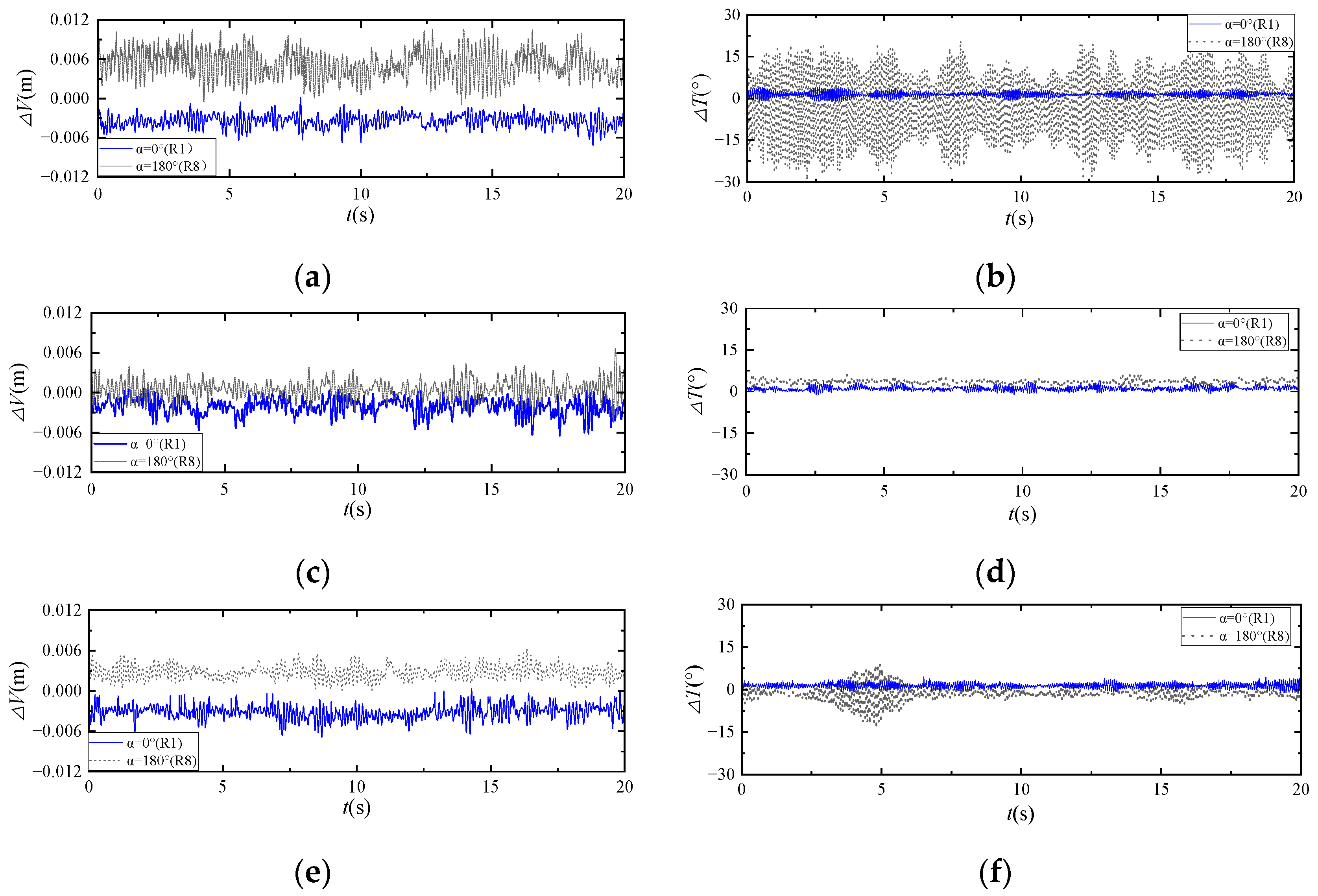

Figure 6 presents the time-history responses of vertical and torsional displacements for each row in three different structural configurations of the cable-supported array at a wind speed of

U = 5.2 m/s. Under all tested combinations of wind direction, sag-to-span ratio, and module tilt angle, the cable-supported PV array exhibits coupled vertical and torsional vibrations at this wind speed. The vibrational response is more intense at a wind direction of 180° than at 0°. Moreover, the coupling between vertical and torsional motions is more pronounced under the 180° condition. These directional differences become particularly significant in configurations combining larger tilt angles with greater sag-to-span ratios.

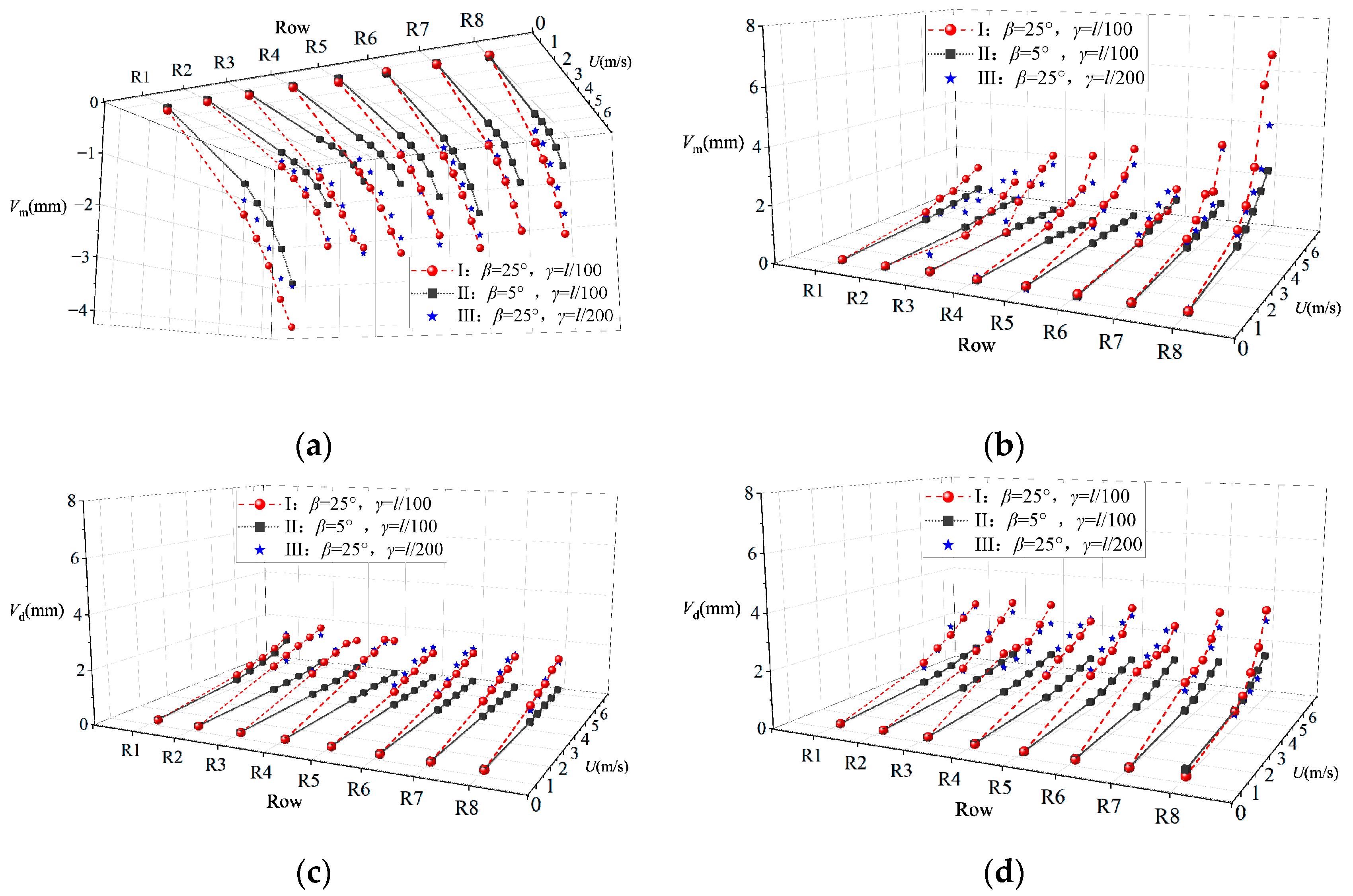

Figure 7 compares the variation in vertical displacement response with wind speed for the cable-supported PV array under different tilt angles and sag-to-span ratios. Under all test conditions, both

Vm and

Vd for each row exhibit a monotonic increasing trend with rising wind speed. Furthermore, the influence of the sag-to-span ratio on the vertical displacement response becomes progressively more pronounced at higher wind speeds. Reducing the sag-to-span ratio directly enhances the structural stiffness, thereby significantly improving the system’s resistance to deformation under static wind loads and effectively suppressing vertical vibrations across all positions. Regardless of wind direction, the first two windward rows represent the most critical positions in the array, with the maximum

Vm typically occurring at the first windward row and the maximum

Vd at the second. A reduction in the sag-to-span ratio substantially decreases both maximum

Vm and

Vd values. At a wind speed of 5.2 m/s, decreasing the sag-to-span ratio from

γ =

l/100 to

γ =

l/200 results in maximum reductions of 48.7% in

Vm and 54.1% in

Vd for the first windward row, while for the second windward row, the maximum reductions reach 30.1% in

Vm and 13.7% in

Vd.

The cable-supported PV array with β = 5° exhibits a more gradual increase in vertical displacement response with wind speed across all rows. Under varying wind directions, wind speeds, and span configurations, the vertical displacement response remains consistently smaller compared to arrays with greater tilt angles. At a wind speed of 5.2 m/s, for instance, compared to the β = 25° configuration, the array with β = 5° shows reductions of 34.9% in maximum Vm and 36.6% in maximum Vd at α = 0°. Under α = 180° conditions, the maximum Vm and Vd for the β = 5° array are reduced by 64.6% and 43.2%, respectively.

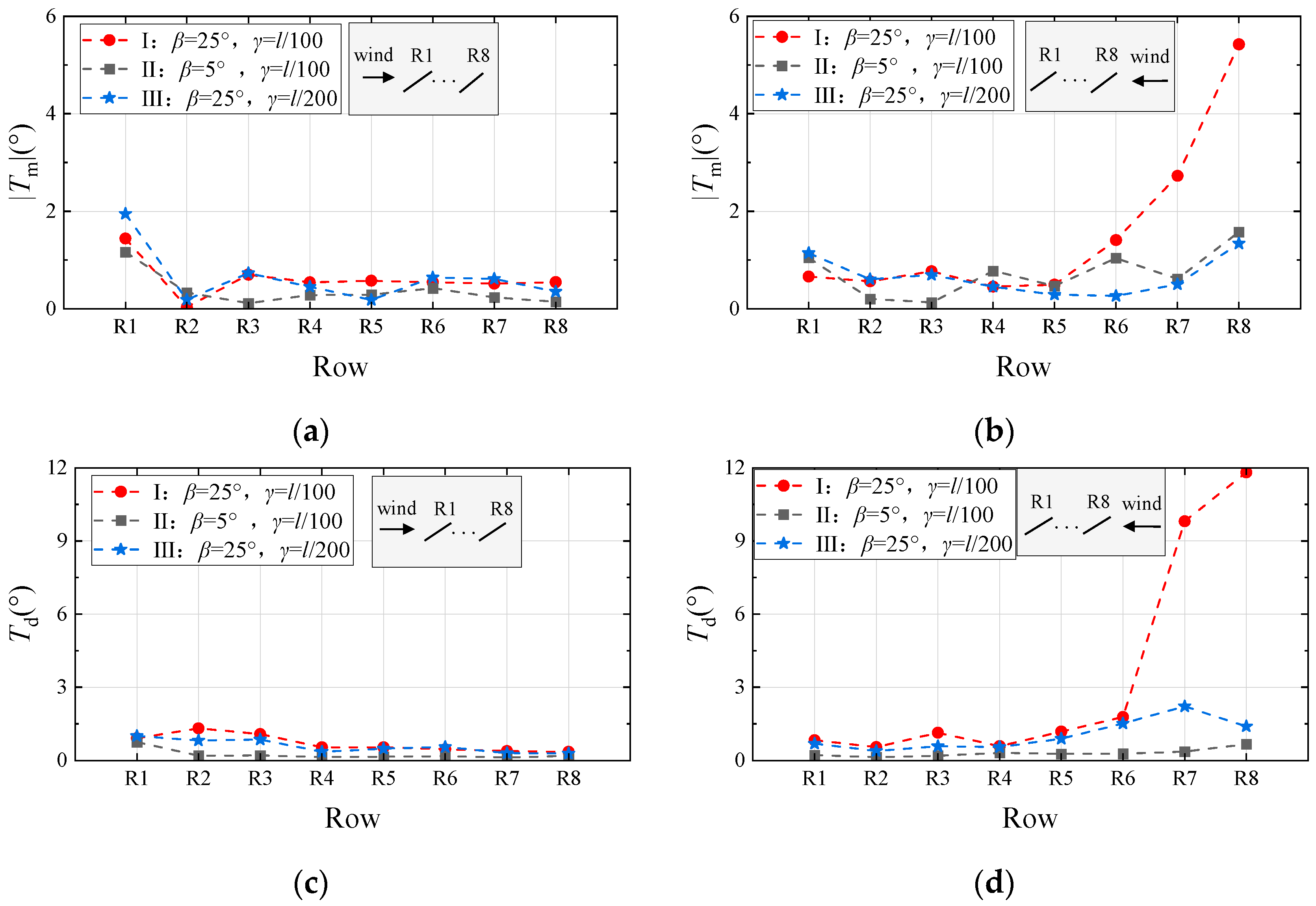

Figure 8 compares the variation in torsional displacement response with wind speed for the cable-supported PV array under different tilt angles and sag-to-span ratios. Under all test conditions, both the mean and fluctuating components of torsional displacement exhibit an increasing trend with rising wind speed across all rows.

Figure 8a and

Figure 8b show the variations of

Tm under wind directions of 0° and 180°, respectively. The results indicate that reducing the sag-to-span ratio has a more pronounced effect on

Tm at α = 180°. At a wind speed of 5.8 m/s, the maximum

Tm occurs at row R8 for the configuration with

γ =

l/100, while this maximum value is significantly reduced when

γ =

l/200.

Figure 8c and

Figure 8d present the variations of

Td under 0° and 180° wind directions, respectively. For the configuration with

γ =

l/100, aerodynamic instability occurs to varying degrees in the first two windward rows, exhibiting a sudden increase in

Td with increasing wind speed. At a wind direction of

α = 0°, the aerodynamic instability wind speed for both R1 and R2 is 5.8 m/s under the

γ =

l/100. Reducing the sag-to-span ratio decreases the torsional vibration amplitude during aerodynamic instability by 49% to 61.9% at the same wind speed, with the amplitude reduced to below 3.2°. Under

α = 180°, the aerodynamic instability wind speed decreases to 4.0 m/s for the

γ =

l/100, indicating that the 180° wind direction is more susceptible to aerodynamic instability compared to 0°. Reducing the sag-to-span ratio to

l/200 not only increases the critical wind speed for aerodynamic instability but also reduces the torsional amplitude during instability, thereby significantly enhancing structural safety. When the sag-to-span ratio is reduced from

γ =

l/100 to

γ =

l/200, the first windward row experiences reductions of 75.3% in

Tm and 88.1% in

Td, while the second windward row shows a 79% reduction in

Tm and a 77.4% reduction in

Td. The mitigating effect of reducing the sag-to-span ratio on wind-induced torsional vibration is more pronounced at

α = 180°.

The cable-supported PV array with

β = 5° exhibits a more gradual increase in torsional displacement response with wind speed across all rows. Under different wind directions and wind speeds, the torsional displacement response remains consistently smaller compared to the cable-supported PV array with

β = 25°. As shown in

Figure 8a,b, under both

α = 0° and 180° conditions, reducing the tilt angle demonstrates a more pronounced effect in decreasing

Tm at the first windward row of the array. In

Figure 8c,d, for the configuration with

β = 25° and

γ =

l/100, aerodynamic instability occurs in both the first and second windward rows under

α = 0° and 180° wind directions. The onset wind speeds for this instability are 5.8 m/s and 4.6 m/s, respectively. However, reducing the tilt angle significantly increases the critical wind speed for aerodynamic instability in the cable-supported PV array, with no instability observed even at 5.8 m/s. Taking a wind speed of 5.2 m/s as an example, compared to the

β = 25°, the array with

β = 5° shows reductions of 19.4% in maximum

Tm and 42.4% in maximum

Td at

α = 0°. Under

α = 180° conditions, the maximum

Tm and

Td are reduced by 70.8% and 94.4%, respectively, compared to the

β = 25°. The differences in displacement response between

β = 25° and 5° are more pronounced at

α = 180°.

4. Wind-Induced Interference Effects of Cable-Supported Photovoltaic Array

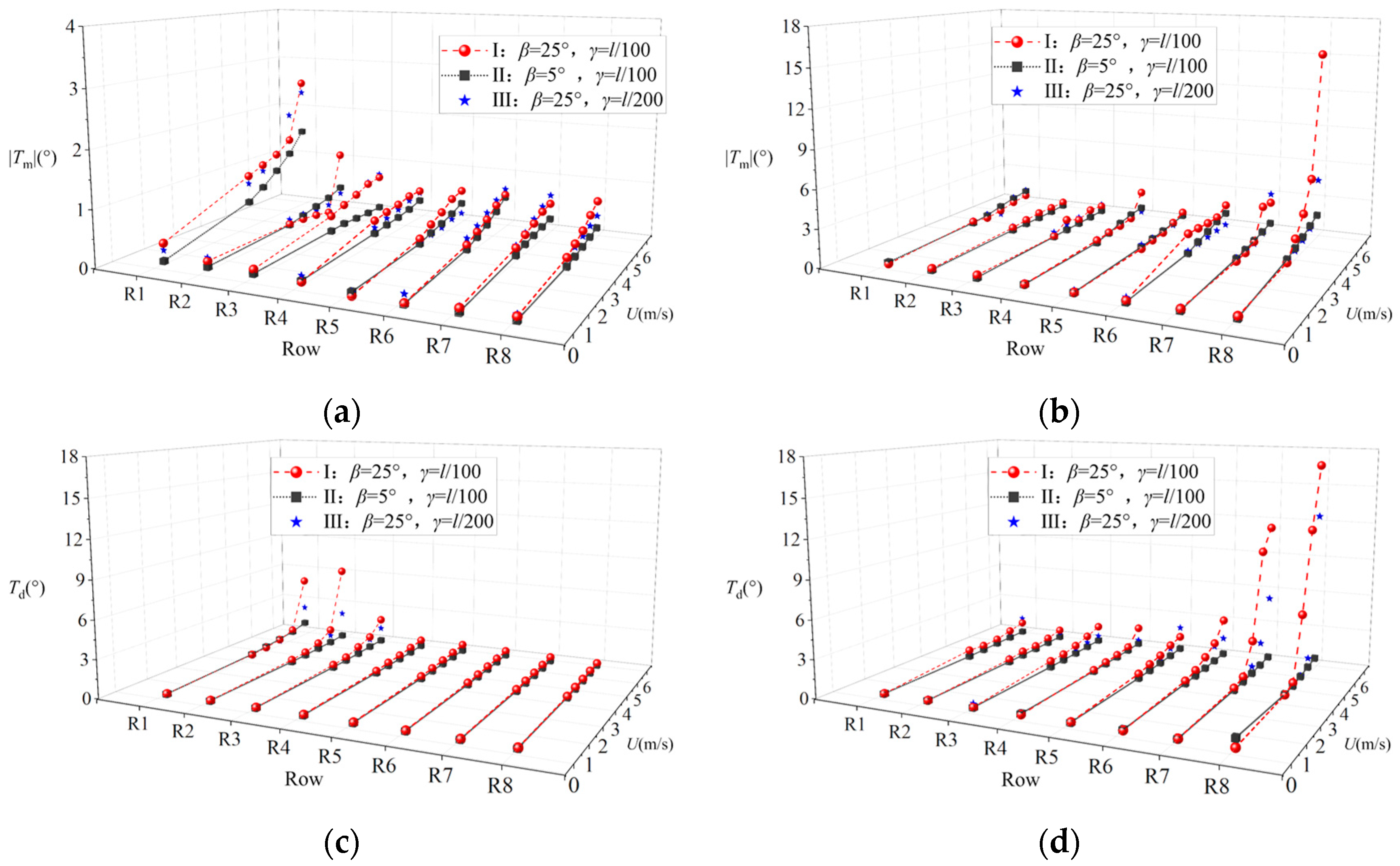

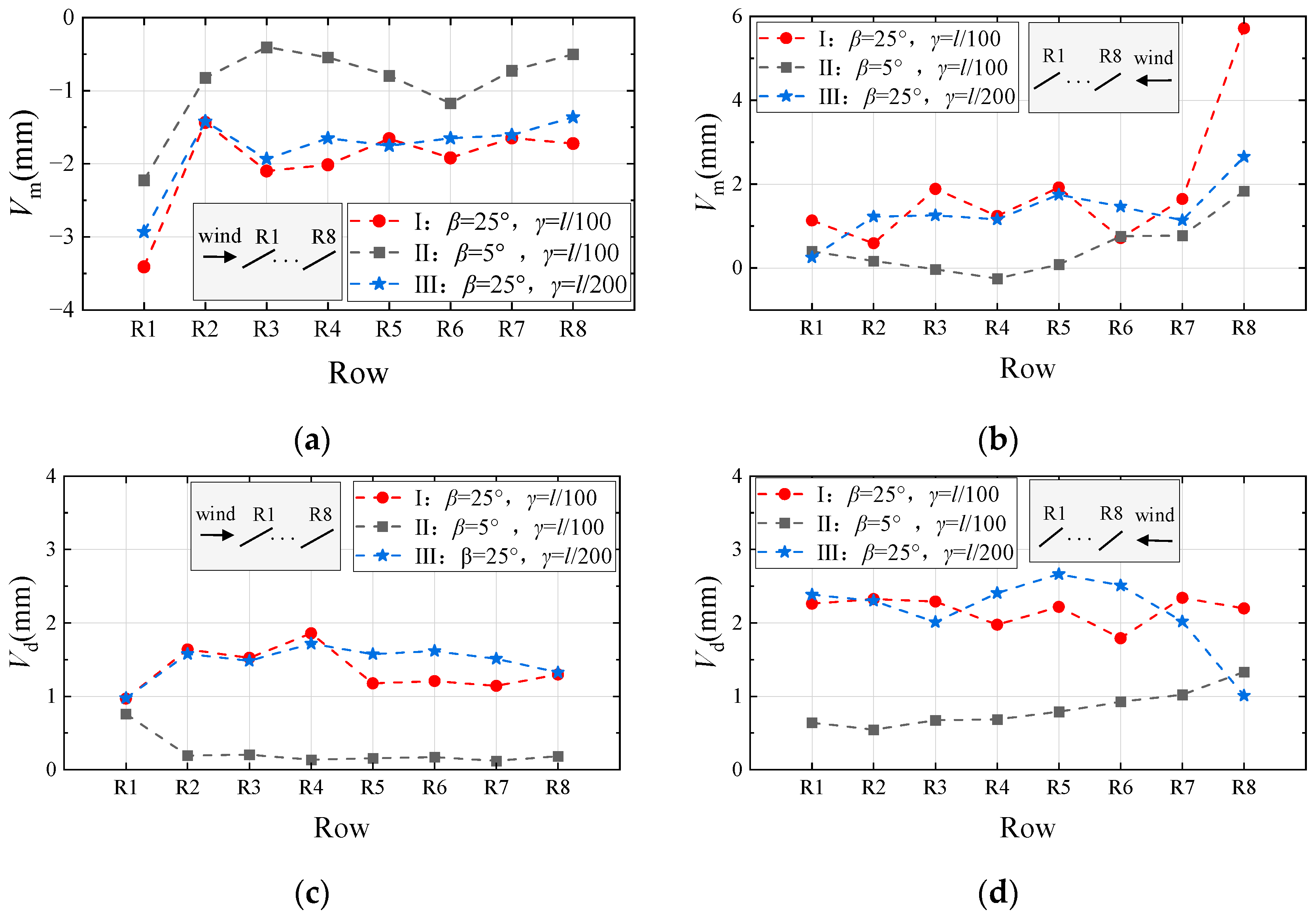

Having identified the wind-induced response characteristics of the cable-supported PV array, the mean and fluctuating components of the wind-induced vibration for each row at a wind speed of 5.2 m/s were extracted to further investigate the interference effects.

Figure 9 shows the variation in vertical displacement response with array position under different test conditions. Across all configurations, the maximum

Vm consistently occurs at the first windward row, followed by a substantial reduction at the second windward row. Under 0° wind direction, the reduction in

Vm reaches 58.8% for Case I, 63.1% for Case II, and 48.5% for Case III. Similarly, under 180° wind direction, the corresponding reductions are 71.3%, 57.9%, and 57.0% for Cases I, II, and III, respectively. Thus, across all tested tilt angles and sag-to-span ratios, the interference effect of the front rows on the rear rows consistently manifests as a pronounced shielding effect on

Vm. A comparison between Case I and Case III in

Figure 9 reveals that reducing the sag-to-span ratio may lead to increased

Vd values in the middle and rear sections of the array. The interference from front rows manifests as a more pronounced amplification of dynamic response in downstream rows. This phenomenon occurs because the reduced sag-to-span ratio, while increasing structural stiffness, subjects rear rows to more complex wake interference patterns. The enhanced structural stiffness may render rear rows more susceptible to excitation by specific frequencies present in the wake, consequently leading to amplified vibrations.

The interference effects in cable-supported PV arrays exhibit significantly different patterns in their influence on Vd depending on the module tilt angle. In Case II, the maximum Vd occurs at the first windward row, with the second windward row showing reductions of 75% and 22.6% under 0° and 180° wind directions, respectively. The rear windward rows consistently demonstrate lower Vd values than the first row. In contrast, Case I shows increases of 69.8% and 6.4% in Vd at the second row under 0° and 180° wind directions, with most rear rows exhibiting higher Vd values than the first windward row, where Vd generally remains the lowest in the array. This indicates that changes in tilt angle significantly alter the flow structures through the PV array, resulting in two distinct interference mechanisms governing the fluctuating response. For β = 5°, the consistent attenuation of both mean and fluctuating displacements along the downstream rows indicates the predominance of shielding effects. The wake generated by the front windward rows acts as a buffer, reducing the wind load intensity on the downstream supports. In contrast, for β = 25°, the significant amplification of fluctuating displacements from the second row onward reveals the dominance of wake excitation effects. The larger tilt angle promotes strong, periodic vortex shedding from the upstream panels. The second windward row, located directly within the impingement zone of these vortices, experiences enhanced forced vibration, creating potential risks for vortex-induced vibrations.

In summary, variations in the sag-to-span ratio exert minimal influence on the overall trend of interference effects within the array, whereas distinct patterns of interference mechanisms emerge across different module tilt angles. Specifically, under all tested configurations of tilt angle and sag-to-span ratio, the interference from front to rear rows consistently manifests as a shielding effect on Vm. However, for Vd, the interference characteristics diverge significantly: arrays with larger tilt angles exhibit an amplification effect from front to rear rows, whereas those with smaller tilt angles maintain a shielding effect on Vd.

Figure 10 presents the variation in torsional displacement response with position in the cable-supported PV array. The torsional displacement follows patterns generally consistent with those observed for vertical displacement. For the mean torsional displacement

Tm, the interference from windward to downstream rows demonstrates a clear shielding effect. Changes in the sag-to-span ratio show negligible influence on the overall interference trend across the array. However, distinct mechanisms govern the fluctuating torsional displacement

Td: arrays with

β = 25° exhibit an amplification effect from front to rear rows, while those with

β = 5° maintain a shielding effect on

Td. In Case I under 180° wind direction, as shown in

Figure 10d of this figure, the significantly higher

Td values observed at the first two windward rows R8 and R7 compared to downstream rows result from the occurrence of aerodynamic instability in these front rows.

Analysis of

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 reveals that the aerodynamic interference effects on the wind-induced response of the cable-supported PV array vary with module tilt angle and sag-to-span ratio. Unlike the consistent shielding effect observed in wind load studies where upstream panels protect downstream ones, the wind-induced vibration interference in cable-supported arrays does not uniformly manifest as shielding. It may also exhibit dynamic amplification effects. To further quantify the interference mechanism in the wind-induced vibration of cable-supported PV arrays, and with reference to the reduction factor defined in the literature [

11], this study defines the positional interference coefficient

η using Equations (3) and (4):

where

Vmi represents the mean vertical displacement of the

i-th windward row,

Vm1 denotes the mean vertical displacement of the first windward row,

ηmi is the positional interference coefficient of the

i-th row based on mean vertical displacement;

Vdi indicates the fluctuating vertical displacement of the

i-th windward row,

Vd1 represents the fluctuating vertical displacement of the first windward row, and

ηdi is the positional interference coefficient of the

i-th row based on fluctuating vertical displacement. In the wind-induced vibration analysis of cable-supported PV systems, both vertical and torsional displacements offer distinct advantages. This study adopts vertical displacement for defining the interference coefficient. Since the interference coefficient is derived from both mean and fluctuating components, vertical displacement provides a more accurate characterization of wind-induced response trends, while torsional displacement proves more suitable for investigating critical wind speed behavior.

In previous studies, research on interference coefficients has predominantly focused on wind loads, without accounting for the aeroelastic effects of cable-supported systems. The characteristics of wind-induced vibration interference may differ between mean and fluctuating. Studies on single-axis trackers have demonstrated significant shielding effects at the second and third windward rows [

11], which aligns with observations for cable-supported systems.

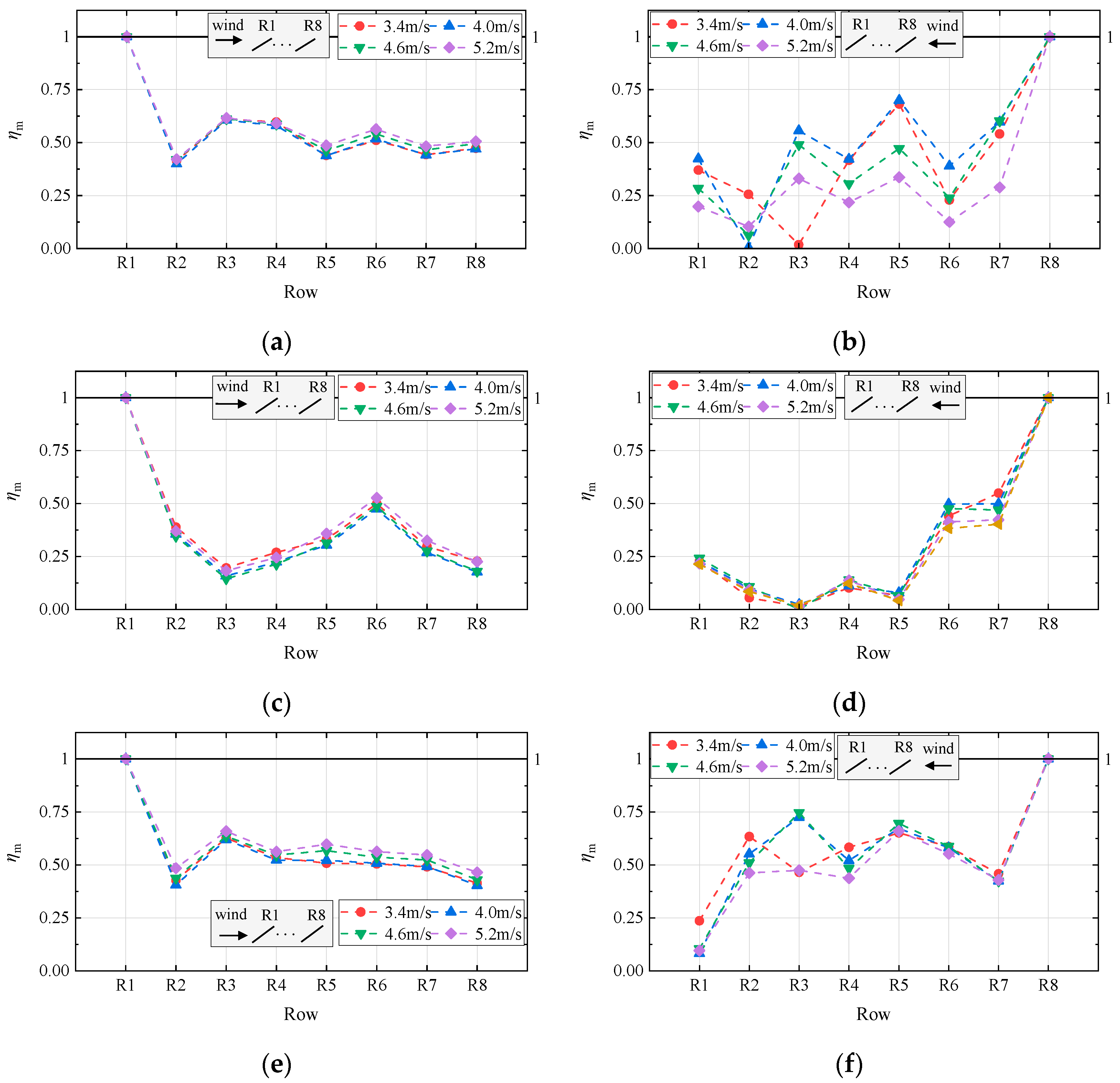

Figure 11 shows the variation of

ηm with array position across test cases at wind speeds ranging from 3.4 m/s to 5.2 m/s. At the mean, a strong correlation exists between load and response interference effects, leading to consistent conclusions regarding the decreasing trend from windward to leeward rows [

9]. The reduction coefficients

ηm for the second to eighth windward rows all remain below unity. However, differences emerge in the downstream trend, which exhibits greater instability compared to wind-load-based reduction coefficients, particularly under 180° wind direction. This instability arises from increased flow complexity due to more intense wind-induced vibrations of the cable-supported system at this wind direction. Therefore, investigating load reduction can provide reasonable predictions for the attenuation of mean.

In

Figure 11a,c, under 0° wind direction, the array with

β = 25° exhibits the minimum reduction coefficient

ηm at the second row, ranging between 0.40 and 0.42. For the

β = 5° configuration, the minimum

ηm occurs at the third row, with values between 0.14 and 0.20 across wind speeds. In

Figure 11b,d, under 180° wind direction, the array with

β = 25° displays a zigzag variation pattern of

ηm along windward rows, indicating that the larger tilt angle induces more complex flow field disturbances. In contrast, the

β = 5° array shows

ηm values around 0.5 at the second and third windward rows, while downstream rows maintain relatively stable reduction coefficients, all below 0.25.

In

Figure 11a,b,e,f, arrays sharing the same tilt angle but different sag-to-span ratios exhibit fundamentally consistent trends in

ηm variation. The array with

γ =

l/200, being stiffer and having higher natural frequencies, demonstrates greater sensitivity to wind speed variations. It also shows improved shielding effects from front to rear rows. Under 0° wind direction, the downstream

ηm trend remains more stable, displaying an initial increase followed by a gradual decrease from the second windward row backward. Although considerable variations persist between rows under 180° wind direction, similar to the 0° wind direction, the smallest

ηm consistently occurs at the last windward row. This pattern confirms that the overall performance of the shielding effect in the array with

γ =

l/200 is superior to that of the

γ =

l/100.

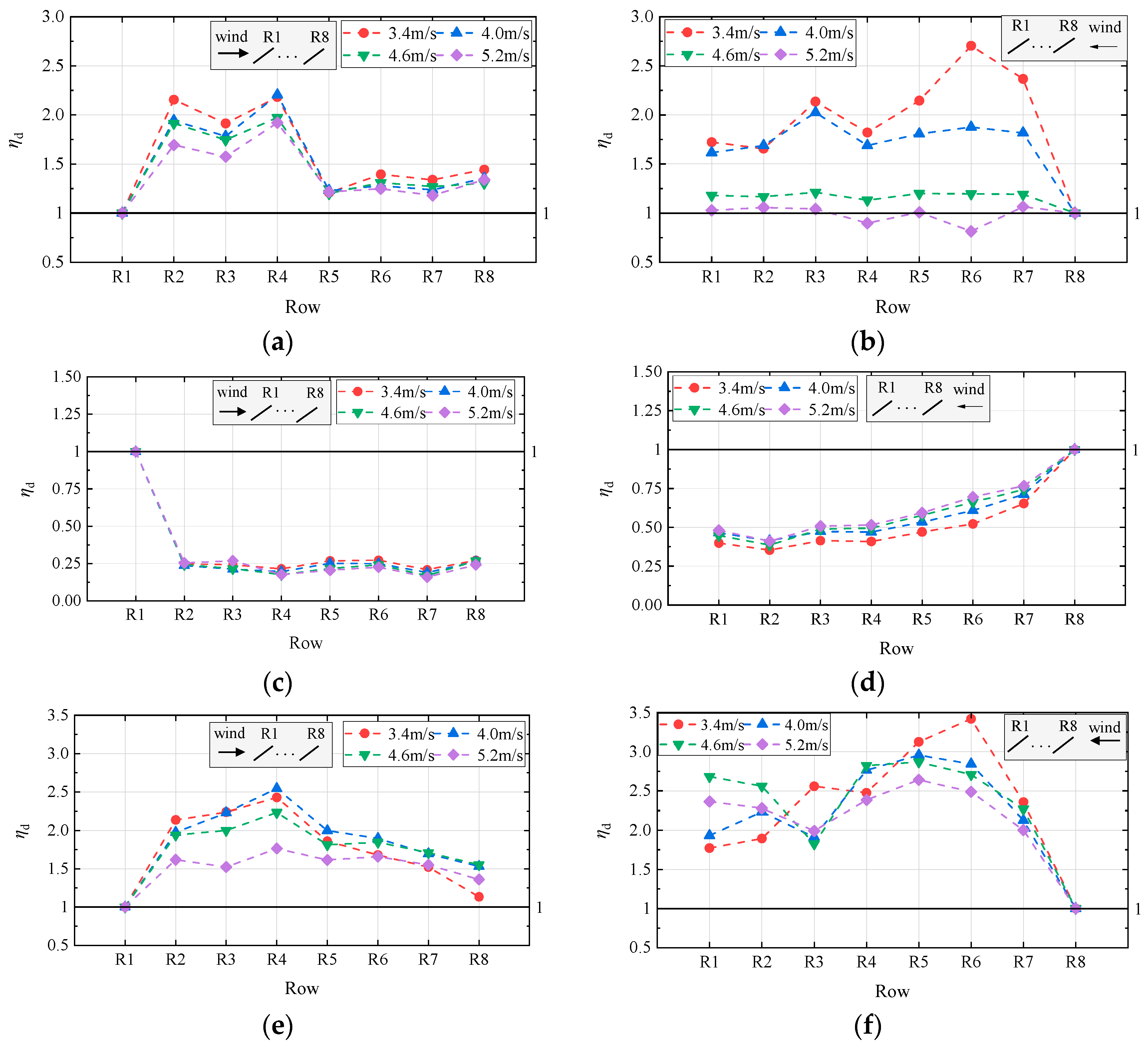

Figure 12 illustrates the variation of

ηd with array position under different wind speeds. In

Figure 12a,b,e,f, for the large-tilt-angle configuration within the wind speed range of 3.4–5.2 m/s,

ηd decreases with increasing wind speed, indicating a weakening interference effect of front rows on the dynamic response of downstream rows. In

Figure 12c,d, the arrays with small tilt angles show negligible variation in

ηd across different wind speeds.

For the cable-supported PV array with

β = 25° and

γ =

l/100, shown in

Figure 12a,b, the interference coefficient

ηd exhibits significant fluctuations in downstream rows. At lower wind speeds, the second to fourth windward rows experience strong wake effects from upstream rows, with

ηd reaching values as high as 2.7. The spatial evolution of

ηd from windward to leeward rows generally stabilizes after two complete cycles of initial increase followed by decrease, suggesting the development of a relatively uniform turbulent wake. In contrast, at higher wind speeds,

ηd values decrease substantially and demonstrate a more stable progression along the array.

In

Figure 12c,d, the variation trends of

ηd differ significantly under different tilt angles. For the cable-supported PV array with

β = 5° and

γ =

l/100, the interference from front to rear rows is pronounced and consistently manifests as a shielding effect. A substantial decrease in

ηd is observed at the second windward row across wind speeds, with values ranging between 0.23~0.25 under 0° wind direction and 0.35~0.42 under 180° wind direction. Furthermore, the variation in

ηd from the second to the last windward row remains relatively small under both wind directions: differences fall within 0.06~0.13 at 0° and 0.30~0.36 at 180°. In summary, the phenomenon of significant dynamic response in the central region of the array [

14,

21] occurs in configurations with large tilt angles rather than small ones. This behavior is attributed to vortex shedding from the first windward row, which induces notable fluctuations in the flow field across the central part of the array. Subsequently, the wake gradually stabilizes toward the downstream region of the array.