1. Introduction

Selecting appropriate building materials is crucial for ensuring structural integrity, longevity, and cost efficiency while promoting sustainability. Historically, natural materials such as stone, sand, earth, and wood were widely used, but modern construction has shifted toward energy-intensive materials like cement and concrete [

1]. These innovations have improved performance but significantly increased carbon emissions, which account for nearly 37% of global greenhouse gas emissions, with cement production alone contributing approximately 8% [

2,

3]. Achieving net-zero embodied carbon by 2050 requires reducing cement use and adopting low-carbon alternatives such as compressed stabilized earth bricks (CSEBs).

Building materials also account for approximately 50–66% of housing costs [

4,

5]. Improved traditional building materials can offer affordable, durable alternatives to expensive imports while aligning with global decarbonization goals. This is particularly relevant in developing regions, where the rising costs of cement and steel exacerbate financial burdens. Continued reliance on conventional materials contributes to ecological harm, including deforestation and soil erosion, and highlights the need for innovative solutions that balance affordability with environmental responsibility.

Within this framework, interest in earth-based construction materials, especially compacted earth, is growing, largely due to the substantial energy demands and environmental consequences, such as elevated carbon emissions, linked to conventional building materials [

6,

7,

8]. Soil has been a fundamental building material for millennia, and it continues to be among the most prevalent worldwide, especially in less developed areas [

7]. According to UNESCO data, about half of the world’s population lives in homes built from earth [

9], with higher percentages in developing regions, particularly Africa, Latin America, and Asia. In some places, like Cameroon, over 95% of traditional housing is made from earth [

10]. However, raw earth has notable drawbacks, including significant water uptake caused by its permeability, contraction as it dries, and poor moisture resistance.

CSEBs are a modern adaptation of adobe, one of the earliest known building materials [

4]. Despite their potential advantages—such as affordability, structural stability, and aesthetic value—the quality of CSEBs produced has been inconsistent. This is largely due to the absence of standardized production procedures and limited scientific data on raw material compositions. Previous studies [

4,

11,

12,

13] and institutions such as Auroville (India), CRATerre (France), and Hydraform (South Africa) have advanced CSEB development, but further research is needed to establish uniform production methods and optimize material compositions for consistent performance. Given these limitations, the application of CSEBs in most developing countries remains limited [

4]. Regulatory support and industry standards are also lacking [

2]. At the same time, rising costs of conventional building materials and the growing demand for sustainable local alternatives worldwide [

14] underscore the urgency of promoting CSEBs as a viable solution for affordable, low-carbon construction.

Despite growing interest and the urgent need for sustainable alternatives discussed above, empirical evidence quantifying the environmental benefits of CSEBs remains scarce. These benefits include cement savings and embodied carbon reduction, particularly in the context of low-income housing and climate mitigation. Most prior studies have focused narrowly on mechanical properties, with few linking material optimization to global decarbonization targets or assessing scalability for affordable housing. This study addresses these gaps by introducing an integrated approach that combines technical performance evaluation with environmental impact analysis, using locally sourced Ethiopian soils and providing global projections of climate benefits.

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the technical viability of CSEBs as a sustainable wall construction material. Specifically, the study aims to (i) identify the most suitable soil-cement proportion for stabilization, (ii) examine how compaction pressure influences the physical characteristics of CSEBs, and (iii) quantify the potential for cement savings and embodied carbon reduction compared to conventional masonry units.

By combining performance evaluation with a targeted carbon impact analysis, this research aims to deliver an integrated perspective on the role of CSEBs in advancing sustainable, low-emission construction practices. Rather than a full life cycle assessment, the study adopts a focused approach that quantifies embodied carbon savings through cement reduction, aligning with global decarbonization goals. This work is organized around the following research questions.

What is the optimal soil–cement proportion for producing high-quality CSEBs?

How does compaction pressure affect the compressive strength and water absorption of CSEBs?

To what extent can the use of CSEBs reduce cement consumption and embodied carbon emissions compared to conventional masonry units?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Building Materials and Economic Development

The construction sector accounts for nearly 40% of global raw material use and plays a major role in environmental degradation. It is responsible for about 37% of total CO

2 emissions [

2,

15], with a significant portion arising from building material manufacturing processes. It exerts considerable strain on environmental systems. Therefore, acknowledging the crucial role of building materials in global decarbonization efforts is essential [

16]. Despite this, the sector plays a pivotal role in economic and social development, stimulating demand for goods and services in related industries and generating millions of jobs annually across different economies [

17]. Its activities are essential for achieving national socio-economic goals, such as providing housing, infrastructure, and employment opportunities, among others.

The construction industry is vital for national prosperity, creating jobs through new projects, repurposing existing buildings, and refurbishment efforts across the entire economy. Its interconnectedness with other sectors highlights how economic growth and social equity are heavily reliant on the construction sector. In many developing nations, the construction sector accounts for an estimated (6–9%) of gross domestic product, reflecting its significant role in economic development. Amid sustained economic growth, the sector recorded an 8.2% increase, with the construction industry typically representing (40–60%) of capital investment in developing nations [

18]. The industry’s sensitivity to socio-economic conditions underscores the need for clear policies and strategies to guide sustainable development.

Research shows that construction impacts nearly every aspect of the economy, making it a crucial contributor to economic growth [

19] and a key candidate for adopting circular economy principles. This can be achieved through measures such as incorporating green technologies, prioritizing sustainable and recycled materials, and minimizing waste throughout the building life span [

20]. To address these environmental and economic challenges, the construction industry must adopt sustainable practices.

Ensuring the implementation of sustainable building practices can be achieved by utilizing sustainable components [

21]. Investing significantly in the sustainable sourcing of materials is crucial for minimizing potential environmental damage. As environmental concerns continue to grow, selecting sustainable materials is no longer optional but imperative for construction organizations [

22]. This approach aligns with global initiatives.

2.2. Key Features of Earth for Eco-Friendly Building

Earth is a versatile and sustainable building material with several advantages that make it suitable for environmentally conscious construction.

Low environmental impact: Soil blocks have a minimal environmental footprint [

23,

24,

25]. They require minimal energy for extraction and preparation, resulting in reduced embedded energy related to conventional materials such as concrete and steel.

Strength: For instance, the New Mexico adobe code mandates that traditional adobe units achieve at least 2 MPa in compressive strength [

26]. Soil blocks exhibit notable strength, durability, and longevity, often outlasting typical wood frame buildings, which have an average lifespan of 60–80 years [

27]. The advent of hydraulic press technology has further enhanced the durability, simplicity, and sustainability of earthen construction. This technology merges traditional materials with modern innovations, enhancing their structural performance and consistency.

Energy Efficiency: Soil blocks are made from readily available materials: sand, clay, silt, cement, and water. One of the most compelling advantages of soil block buildings is their exceptional energy efficiency. The thermal mass properties of soil blocks help regulate indoor temperatures, resulting in notable reduction in energy costs for residents and the wider community. Compressed soil blocks require substantially lower energy during production than conventional fired bricks or concrete blocks, consuming only about one-fifth to one-fifteenth of the energy needed for fired bricks [

28]. According to findings reported in [

29], earth wall systems can reduce embodied energy by approximately (62–71%) when compared to conventional wall construction methods. Research has shown that compressed soil blocks have a heat transfer coefficient of around 2.66 W/(m

2·K) [

30], indicating good thermal performance.

Acoustic Performance: Soil blocks are incredibly dense, providing excellent sound insulation. Their ability to dampen sound makes them particularly advantageous in acoustically sensitive settings, such as music production spaces. Compressed stabilized soil blocks exhibit sound absorption coefficients between 0.71–0.99 at frequencies of 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz, and 4000 Hz [

31]. This makes them practical substitutes for conventional options like fiberglass insulation and acoustic plasterboard. Earth block buildings create a serene interior environment, which many occupants find to be an added benefit.

Durability: Durability refers to the ability of soil blocks to maintain their mechanical integrity, shape stability, and resilience to climate exposure over the entire life of the structure [

32]. Soil blocks must be durable and waterproof to withstand environmental factors such as rain, wind, and rising damp. The longevity of ancient earthen structures around the world attests to their durability. Soil blocks also offer good resistance to fire and pests [

33]. Cement-stabilized soil blocks are durable units that retain structural integrity after compaction, allowing easy handling and proper curing.

Aesthetic Appeal: Soil block buildings offer versatile design possibilities, allowing them to mimic any finished structure. Supporters of this building technique often appreciate this visual appeal of the blocks and the traditional adobe-style finish. In most cases, the outer surfaces are treated with protective coatings that shield against weathering, which may be tinted or retain the material’s original appearance. Interior surfaces may be treated with different types of plaster or left bare to achieve a rustic aesthetic. Design elements like arches and rounded corners enhance flexibility and visual appeal, harmonizing seamlessly with the natural surroundings.

Thermal Properties: Building materials are assessed for thermal performance using R-values and U-values. The R-value serves as an indicator of a material’s ability to resist heat flow; materials with greater R-values offer enhanced thermal insulation. To determine this value, the wall’s thickness is divided by its thermal conductivity. The U-value, which is the inverse of the R-value, reflects how quickly heat passes through a material. Total R- and U-values for a wall are obtained by summing the values of each component, including insulation, sheathing, framing, and masonry [

34]. For masonry-mass walls like adobe, heat capacity is crucial as it determines the time required to reach steady-state heat flow. Higher heat capacity means a longer time to reach this state. Due to ongoing temperature variations, achieving a truly stable state is uncommon. The flywheel effect describes how these walls capture daytime heat and discharge it overnight, ensuring consistent comfort [

34].

2.3. The Research Gap and Objectives

The literature reviewed highlights the growing interest in compressed stabilized earth blocks (CSEBs) as an affordable and environmentally sustainable alternative to conventional masonry. However, several critical gaps remain. Existing studies report inconsistent quality and performance of CSEBs due to variations in soil composition, stabilizer content, and compaction methods. There are no universally accepted standards for mix design or production. While CSEBs are widely promoted as low-carbon materials, empirical evidence quantifying their benefit remains scarce. In particular, data on cement savings and embodied carbon reductions compared to conventional masonry units are limited, especially in the context of low-income housing. Furthermore, most research originates from regions such as India, France, and South Africa, resulting in a lack of context-specific data for Ethiopian soils and local construction practices. These limitations hinder the widespread adoption of CSEBs in sustainable housing projects.

To address these gaps, this study aimed to (i) determine the optimal soil–cement proportions for producing high-quality CSEBs using locally available Ethiopian soils; (ii) assess the influence of compaction pressure on compressive strength and water absorption to establish performance benchmarks; and (iii) quantify cement savings and embodied carbon reduction achieved by CSEBs compared to hollow concrete blocks. By integrating technical performance evaluation with environmental impact analysis, the research provides standardized data and practical guidance for incorporating CSEBs into affordable and climate-conscious construction.

3. Historical Background and Technical Foundations

While using earth as a building material dates back thousands of years, the introduction of compressed stabilized earth blocks marks a significant advancement in this traditional practice. The technique originated in the 1950s as part of a rural housing research program in Colombia. This method represents an improvement over traditional adobe production. In contrast to adobe, which is traditionally shaped manually using wooden molds, compressed soil blocks are produced by compacting damp soil under pressure within a steel mold or press. Initially, wooden tamps were used to create the first compressed soil blocks [

35]. This process results in blocks that are more uniform in size and shape and have greater density compared to hand-molded blocks.

Since its inception in the 1950s, compressed earth block (CEB) technology has steadily advanced, demonstrating both scientific and technical value in construction applications [

35]. Compressed soil blocks have supported multi-story residential and recreational construction globally. Despite their functional advantages, the technique has seen limited application to date in many parts of the world. However, there is a growing revival of this traditional building material, driven by its cost-effectiveness, natural aesthetic appeal, environmental friendliness, and energy conservation benefits. Research centers such as Auroville (India), CRATerre (France), and Hydraform (South Africa) have played significant roles in advancing CEB technology. Their intensive research, experimentation, and architectural innovations have led to the development of technical documentation and academic curricula supporting its use. Current efforts aim to establish norms and standards for compressed soil blocks to legitimize the technique and promote wider adoption in both developing and developed countries [

4,

6].

3.1. Soil Properties and Key Parameters for Compressed Stabilized Blocks Production

Proper analysis of soil properties along with insight into the local climate is fundamental for the production of stabilized soil blocks. Soil properties exhibit significant variability depending on the prevailing climate, whether it be dry, temperate, rainy, or tropical. Soil properties play a crucial role in producing compressed stabilized soil blocks and affect processes such as blending, molding, de-molding, void-ratio, permeability, dimensional change, strength, and bulk density.

CSEB manufacturing demands soil with minimal silt and clay content to ensure structural integrity. For best results, the fines should make up about 25% of the soil, with clay accounting for at least 10% of that portion. An ideal particle size distribution generally includes (40–75%) sand or gravel, (10–30%) silt, and (15–30%) clay [

36].

3.2. Soil Stabilization Using Cement

A range of soil stabilization methods are used worldwide to improve the structural and mechanical characteristics of soil. These include approaches such as mechanical compaction, and chemical treatments using materials like cement, lime, bitumen, gypsum, and pozzolana. This study employed cement-based stabilization, which involved incorporating varying cement proportions into a soil–water mixture and then compacting it under pressure.

Cement chemistry revealed that the material mainly consists of lime and silica. When water and additional components are introduced, hydration reactions occur, forming compounds such as CaO·SiO

2·H

2O [

37]. These reactions create a dense, interlocking matrix that secures coarse aggregates like sand, thereby improving structural stability. Cement was chosen for this research because of its strong adhesive characteristics, proven performance in prior investigations, and broad commercial availability.

Standard Portland cement typically contains around 54% tricalcium silicate (C

3S) and approximately 16.6% dicalcium silicate (C

2S, which are key components influencing its strength and setting behavior [

37]. In moist soil environments, the primary cement compounds—tricalcium silicate (C

3S) and dicalcium silicate (C

2S)—react to form calcium silicate hydrate gels, which contribute to the stabilization process.

These reactions can be simplified as follows [

37]:

The free lime, Ca(OH)

2 undergoes a pozzolanic reaction with the clay fraction, extracting silica from its minerals, thereby generating additional calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H). Over time, C–S–H crystallizes and forms a dense, interlocking matrix within the soil pores, creating strong cohesion among particles. The formed structure does not dissolve in water and provides a robust mechanism that limits soil deformation, thereby mitigating the weakening effects of moisture. Under an electron microscope, cured soil–cement samples revealed interwoven calcium silicate formations arranged in a fibrous network [

38].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sampling Location

Soil samples were obtained from Kara; approximately 20 km to the east of Addis Ababa. This site was selected because local communities traditionally use soil for adobe block production, indicating its suitability for stabilized soil block manufacturing.

4.2. Study Design

The experimental program was designed to evaluate the technical performance of compressed stabilized earth blocks (CSEBs). The study began with material characterization, followed by block production and performance testing. In the first step, the samples were ground and processed to meet the specified particle size range. Then, the gradation was determined using sieve and hydrometer analysis in accordance with ASTM D422 [

39]. Plasticity characteristics (liquid limit, plastic limit, and plasticity index) were measured in accordance with ASTM D4318 [

40] and BS 1377-2 [

41]. Linear shrinkage was determined in accordance with BS 1377-2 [

41]. Soil chemistry was analyzed at the Geological Survey of Ethiopia laboratory using standard procedures, and the results are presented in

Table 1.

Following the initial assessments, a Standard Proctor Test (ASTM D698 [

42] Method A) determined the optimum water content and relative density. The results showed an optimum water content of 19% and a relative density of 1610 kg/m

3. Based on these results, the target moisture content for block production was set at 24%. Locally produced Portland pozzolana cement (PPC) was used as the stabilizing agent, with its properties obtained from [

43]. Potable water was used for mixing and curing in compliance with relevant standards.

After conducting suitability tests for the materials, the mix design and specimen preparation commenced. The mix design followed the literature guidelines, with cement contents ranging from (2–12%), calculated as a percentage of the soil mass, and a fixed water content of 24%. The soil–cement blocks were compacted using a hydraulic press at different pressures from 4–10 MPa, applied in 2 MPa increments. After production, the blocks were cured under controlled conditions and evaluated for mechanical properties and durability in accordance with the test plan.

4.3. Material Suitability Analysis

The soil’s suitability was assessed based on its particle size distribution, plasticity, and chemical composition—key properties influencing its strength and durability [

44]. The soil exhibited a relative density of 2.61 g/cm

3, an optimum moisture content of 19%, and a maximum dry weight of 1610 kg/m

3. Its particle size distribution comprised approximately 70% sand, 16.25% silt, and 13.75% clay, which falls within the recommended range for CSEB production. Plasticity tests yielded a liquid limit (LL) of 31.91%, a plastic limit (PL) of 25.75%, and a plasticity index (PI) of 6.16, indicating low plasticity suitable for stabilization. Linear shrinkage (LS) was measured at 7.14%. Chemical analysis revealed a predominance of silica (SiO

2—65.32%), alumina (Al

2O

3—15.27%), and iron oxide (Fe

2O

3—7.68%), with negligible calcium oxide content (<0.01%).

Table 2 summarizes the soil characteristics and consistency limits.

4.3.1. Soil Gradation Results and Compliance with CSEB Standards

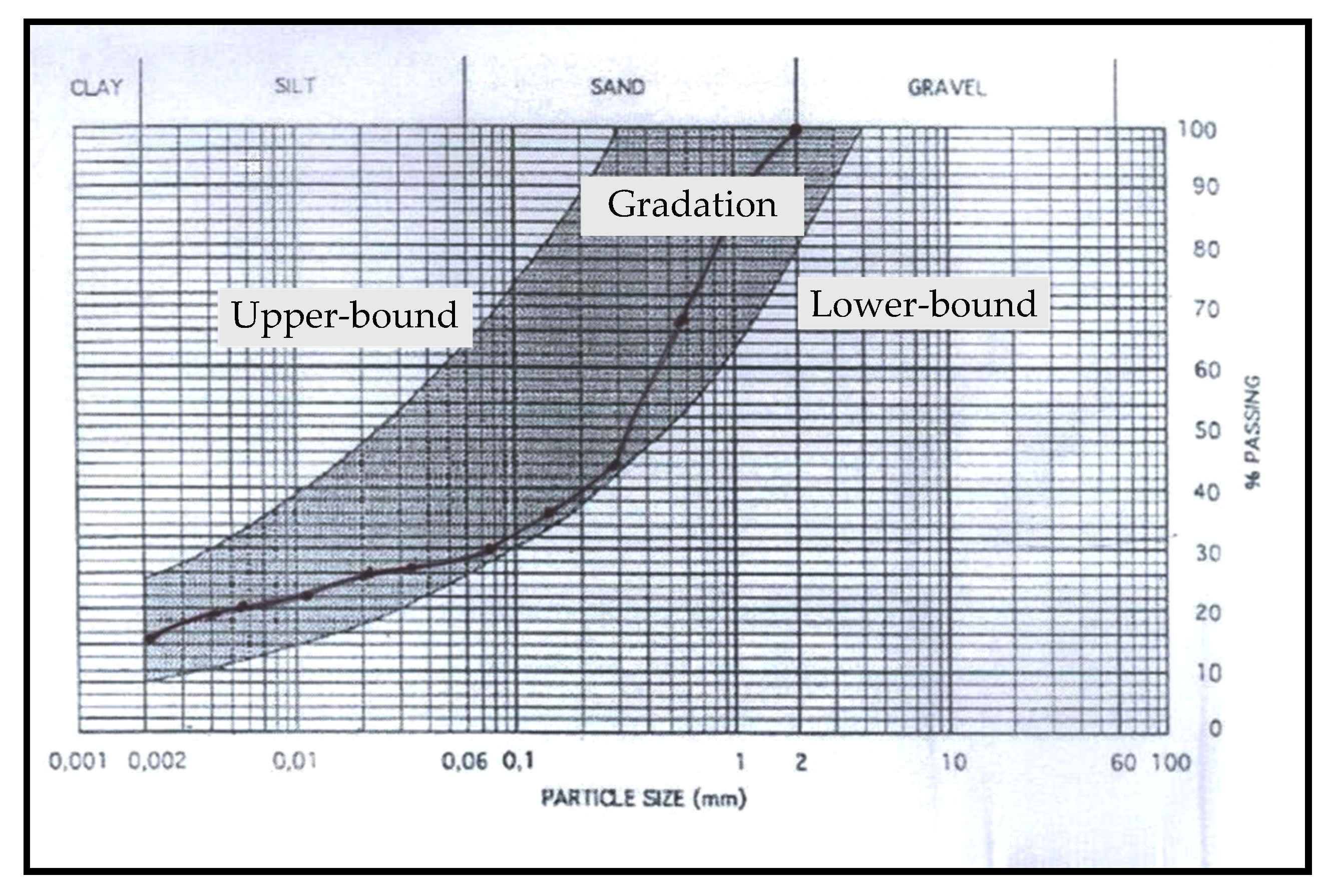

Gradation analysis was performed using sieve and hydrometer methods in accordance with ASTM D422 to determine the particle size distribution of the soil.

Figure 1 presents the resulting gradation curve alongside the recommended range for soil block production. The results indicate that the soil falls within the recommended particle size distribution range for CSEB production, suggesting its potential suitability for block manufacturing.

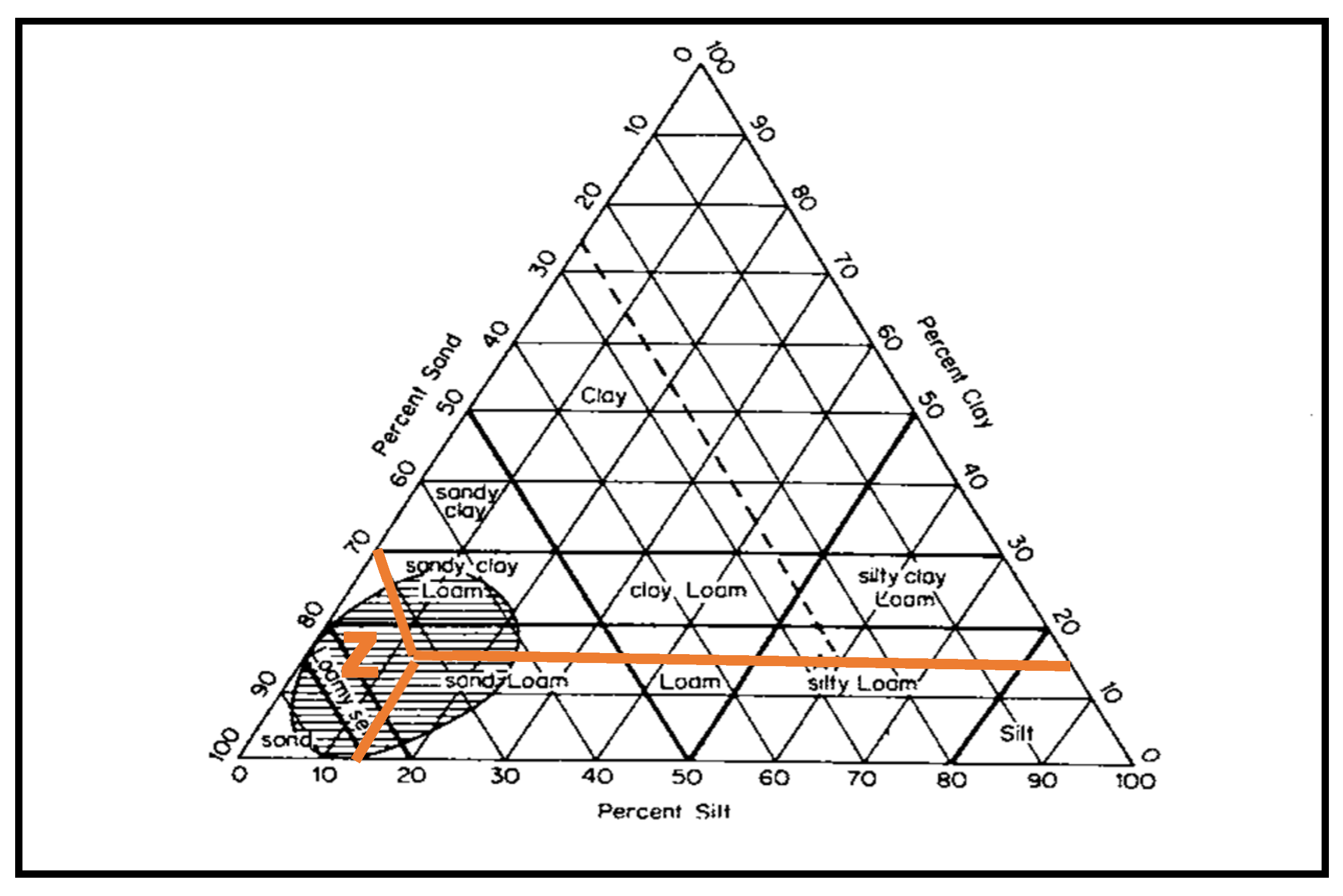

The shaded area in

Figure 2 indicates the soils most suitable for stabilization. The soil sample, which had a composition of 70% sand, 16.25% silt and 13.75% clay as plotted as point “Z” in

Figure 2, falls within the shaded area, indicating the soil’s suitability for CSEB production.

4.3.2. Soil Plasticity Results and Consistency Limits

The Atterberg tests identify moisture thresholds where soil changes state—from liquid to plastic and then to semi-solid. These limits, known as the liquid and plastic limits, are key indicators of soil plasticity and suitability [

45]. In this study, these consistency limits were determined following ASTM D4318 [

40]. Linear shrinkage, which reflects soil volume reduction during moisture loss and provides insight into grading and clay type, was measured according to BS 1377-2 [

41]. It provides a general understanding of soil performance and appropriateness for stabilization.

Table 3 presents the consistency limit test results.

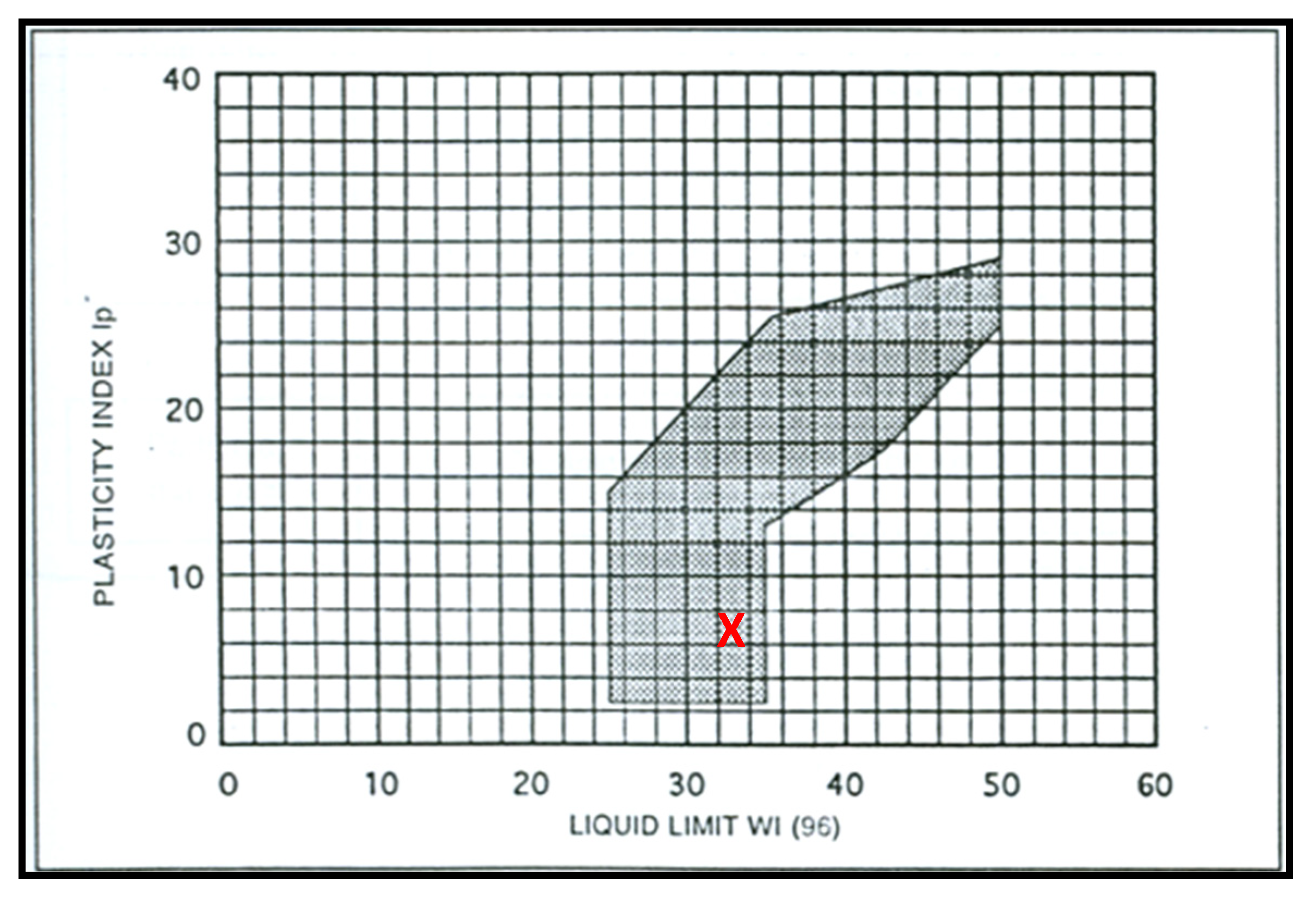

The soil test results presented in

Table 3 were analyzed and plotted on a standard suitability chart for soil stabilization in

Figure 3. The plotted point (marker ’X’) lies within the highlighted zone, indicating compliance with the recommended criteria for CSEB manufacture. Additionally, laboratory findings were compared against the CDI and CRATerre-AEG guidelines [

46]. The soil’s gradation and plasticity characteristics align with the acceptable thresholds in both standards, confirming its suitability for stabilization and justifying investigation.

4.3.3. Cement

Portland pozzolana cement (Mugher cement factory, Biyo, Ethiopia) was used as the binding material. The chemical composition of this cement is provided in a separate source [

43].

4.3.4. Water

During the investigation, domestic drinking water was used, in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the African CSEB standard (WD-ARS 1333:2018) [

47]. This standard specifies that water used in the production and curing of CSEBs must be clean and free from harmful substances. The use of potable tap water in this study meets these criteria, ensuring suitability for both mixing and curing processes in CSEB production.

4.4. Soil-Cement-Water Ratio

Two test plans were prepared to examine the effect of cement–soil–water proportioning.

4.4.1. Test Plan One

The initial set of mixes, comprising five variations, was designed to evaluate changes in compressive strength with the curing age of blocks produced using Pozzolana cement. Each mix had a fixed water content of 24%, while the cement content varied from 4% to 12% in 2% increments calculated as a percentage of the soil mass. The mix codes were labeled as CxW24, where x represents the cement percentage and W24 indicated 24% water content (e.g., C4W24, C6W24, C8W24, C10W24, C12W24). Soil weight was kept constant at 100.45 kg for all mixes.

4.4.2. Test Plan Two

The second set of mixes was conducted to evaluate the effect of molding pressure on the compressive strength of the blocks and the effectiveness of the cement stabilizer. Sixteen mixes were prepared, with cement content ranging from 6% to 12% in 2% increments by weight of soil, and molding pressure varying from 4–10 MPa in 2 MPa increments. Mix codes followed the pattern CxPy, where x represents cement percentage and y represents molding pressure (e.g., C6P4, C8P6, C10P8, C12P10). Soil weight was kept constant for all mixes.

4.5. Test Block Preparation

All block samples were produced using a Hydraform block-making machine operating under a controlled static compression system. Before each compression cycle, the mold lining was lightly coated with a thin layer of lubricant to facilitate smooth demolding. Pre-weighed soil, packaged in clear polyethylene sleeves, was introduced into the mold in measured portions and leveled after each addition to ensure uniform distribution.

Compaction was performed using a side-mounted hydraulic pump applying a pressure of 10 MPa. Upon attaining the specified pressure, the system was slowly relieved through the flow valve, allowing the upper compression ram to retract and expose the freshly formed block. Each block was then removed, placed on base plates, and immediately enclosed in clear polyethylene sleeves for curing under shaded conditions. Pre-curing measurements included block dimensions and weight.

4.6. Tests on Blocks

4.6.1. Compressive Strength Test

This test aimed to evaluate block performance under wet conditions. Testing was carried out in accordance with ASTM standards (ASTM Volume 04.08—Soil and Rock [

39]). Blocks underwent wet curing for 7, 14, 28, and 56 days. After each curing period, dimensions and weights were recorded. A 100 kN compression testing machine, certified and calibrated by Hydraform (Hydraform Building Technology Company, Johannesburg, South Africa), was used throughout the process.

For each mix proportion, three specimens were prepared, and the average of the three recorded values was taken as the representative figure. The mold dimensions were 22 × 22 × 11 cm. Before testing commenced, all specimens were immersed in tap water for 24 h, then allowed to drain for a half-hour period to remove excess surface water. Each specimen was carefully positioned within the marking pins of the compression-testing machine, after which it was prepared for loading and subjected to a constant loading rate equivalent to 3.5 MPa per minute until failure occurred. Compressive strength under wet conditions was calculated using the ratio of peak load to the loaded area.

4.6.2. Water Absorption Test

The specimens were initially weighed in their dry state, then immersed in water for a 24 h period and subsequently weighed again in their saturated condition. All measurements were performed using a digital balance with an accuracy of 0.05 g.

Water absorption by weight was determined using the following formula:

where:

The acceptable range for water absorption in CSEBs, as per the guidelines, is between 15% and 20% [

32].

5. Results and Discussion

The subsequent analysis presents the experimental findings and discusses their implications for CSEB performance and sustainability. The analysis focused on three key aspects: compressive strength, water resistance, and environmental impact.

Compressive strength tests confirmed that blocks stabilized with 6% cement satisfied the structural requirements for wall construction. Water absorption assessments, based on controlled drying and soaking cycles, demonstrated adequate resistance across stabilization levels. Preliminary calculations further revealed substantial cement savings compared to conventional hollow concrete blocks, contributing to notable reductions in embodied carbon and global emissions. These findings underscore CSEBs’ potential for sustainable construction and set the stage for detailed analysis in the following sections.

5.1. Compressive Strength

CSEB strength is influenced by multiple production factors, such as soil composition, stabilizer proportion, the pressure applied, moisture level, and curing conditions. In this study, the cement proportion was the only variable, all other production parameters were kept constant. Previous studies identified stabilizer content as a key factor influencing strength, dimensional stability, and durability in earthen construction materials.

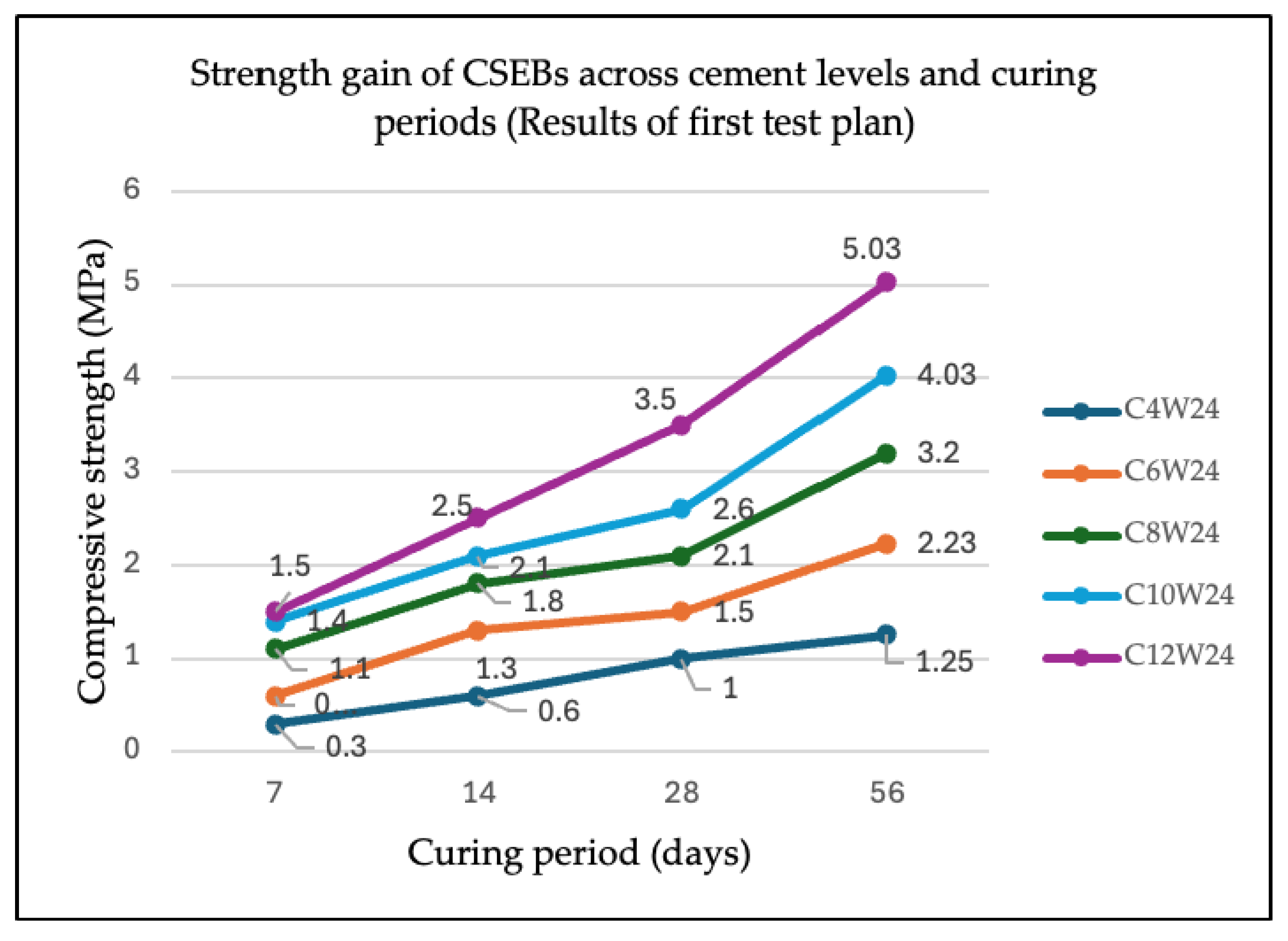

5.1.1. Relationship Between Cement Proportion and Compressive Strength in Stabilized Soil Units

Figure 4 presents the outcomes of the compressive strength evaluations. The data revealed a consistent pattern: compressive strength improved with increased cement content and extended curing durations. Blocks with 6% or more cement content consistently achieved or exceeded the 28-day compressive strength benchmark of 2 MPa, which is the threshold required for class C hollow concrete blocks under ES [

48]. This finding is consistent with previous studies that identified stabilizer content as a critical factor in achieving structural performance [

12,

37], thereby supporting the results of this research. Furthermore, blocks with 6% cement tested at 56 days also met the specified standard.

These findings suggest that when properly manufactured, CSEBs can offer a competitive alternative to conventional hollow concrete blocks. Moreover, with higher cement content, these blocks can achieve superior performance compared to the hollow concrete blocks commonly available in the local market, which often do not meet standard specifications.

The results revealed both general and localized trends. Under constant compaction pressure, increasing cement content led to higher compressive strength. Higher cement content enhances bonding between soil particles through the development of cementitious compounds, leading to improved structural integrity. This mechanism is comparable to the hydration reaction of concrete production, where cement and water interact to create a network of interwoven crystalline structures. This network binds soil particles and inert materials into a dense, cohesive framework, significantly enhancing strength and long-term stability [

37,

38].

Blocks with cement contents ranging from (4–12%) in 2% increments, were produced under a constant compaction pressure of 10 MPa. Their compressive strength measured at 28 days exceeded most specified baseline requirements for structural applications, except for those containing 4% cement. The literature reports various minimum values for 28-day wet compressive strength, all above 1.0 MPa [

4,

10,

11,

26,

38]. All blocks exceeded these minimum values at 56 days.

The graphical data in

Figure 4 illustrate the rate of strength development. While the absolute strength increased steadily, the rate of increase was more pronounced at higher cement contents. For example, doubling the cement proportion from C4W24 to C8W24, as planned in Test Plan One under a compaction pressure of 10 MPa, resulted in about a 110% increase in compressive strength. Likewise, raising from C6W24 to C12W24 at the same pressure was estimated to produce up to a 135% improvement in strength.

5.1.2. Pressure Driven Gains in Compressive Strength of CSEBs

Compressive strength of CSEBs increases consistently with higher compaction pressure. The test results showed that raising the pressure from 4–10 MPa nearly doubled the strength, demonstrating the critical role of pressure in achieving structural integrity. For example, at 8% cement content, strength improved from 1.3 MPa at 4 MPa to 2.6 MPa at 10 MPa, while at 12% cement, it rose from 1.8 MPa to 3.4 MPa. These gains demonstrate that compaction pressure is as influential as cement content in determining block performance. A pressure range of 8–10 MPa emerged as optimal for producing high-strength CSEBs.

Table 4 summarizes the compressive strength ranges at different compaction pressures, with each range representing the variation across cement contents (6–12%). This highlights how pressure and stabilizer proportion interact, showing that higher cement content consistently achieved the upper end of each range, where pressure amplifies those gains.

While stabilizer content is essential for binding and stabilizing the soil matrix, compaction pressure plays a critical role in densifying the material and reducing internal voids. This densification improves the effectiveness of the stabilizer, enhances strength and impact resistance, and reduces the potential for shrinkage, swelling, cracking, and provides a degree of water resistance. The benefits of stabilization are significantly amplified when the soil is adequately compacted.

All specimens in this investigation were compacted at 10 MPa before curing— a level considered sufficient for producing high-quality blocks. However, in practice, many CSEB producers apply pressures much lower than this benchmark, which compromises block strength and durability.

The combined influence of cement content and compaction pressure revealed an important optimization insight: pressure can partially substitute for higher cement content. For instance, a block with 8% cement at 10 MPa (2.6 MPa strength) performs comparably to one with 10% at 8 MPa (2.6 MPa strength). This means producers can achieve blocks that meet the required strength (>2 MPa) by prioritizing compaction pressure rather than increasing cement content, reducing costs and embodied carbon.

In addition to their mechanical performance, CSEBs contribute meaningfully to climate mitigation efforts by offering a significantly lower embodied carbon footprint compared to conventional concrete blocks. According to the UNEP [

2], shifting to regenerative materials such as stabilized soil blocks is essential for achieving a carbon-neutral construction sector by the mid-century. Supporting this, a full-cycle assessment of two projects in India showed that a CSEB building emits only 192 kg CO

2 e/m

2 compared to 747 kg CO

2 e/m

2 for a conventional concrete structure [

49]. The findings underscore the potential of CSEBs as a technically viable and environmentally responsible alternative for sustainable construction.

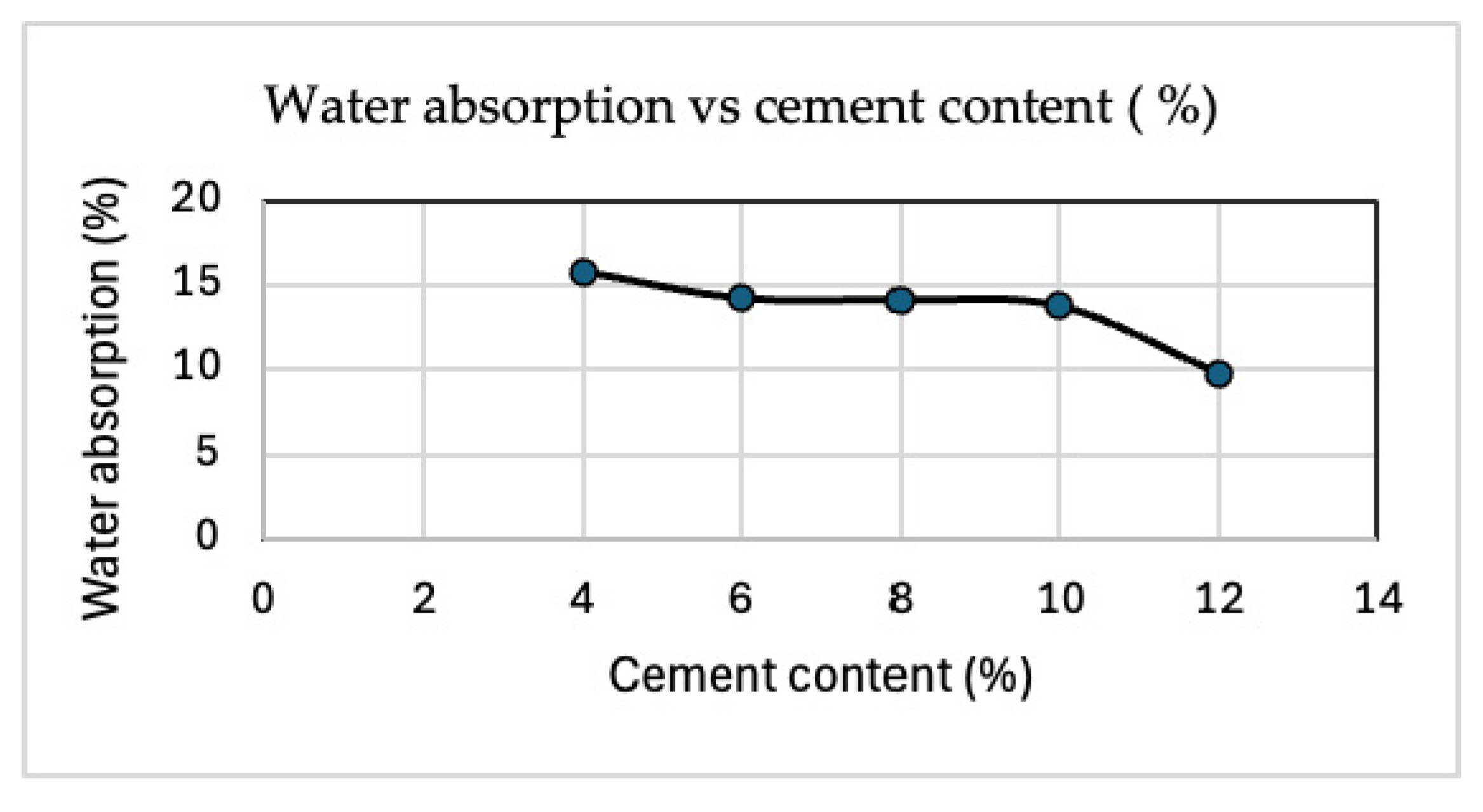

5.2. Water Absorption

As shown in

Table 5 and

Figure 5, water absorption decreases as cement content increases, confirming a clear inverse relationship between stabilization level and moisture uptake. Average absorption dropped from 15.81% at 4% cement to 9.8% at 12%, indicating improved density and reduced porosity. Even at the lowest cement content, absorption remained within the 15% limit recommended by Kerali [

32], validating the adequacy of these mixes for durability under standard conditions.

The variation between 6% and 10% cement was minimal, suggesting that 6% cement may be sufficient to meet the sorptivity requirements, while higher contents further enhance moisture resistance. Overall, increasing cement from 4% to 12% reduced the water absorption by about 38%, confirming that the higher cement content significantly improves resistance to moisture ingress. These findings align with Kerali’s recommendations [

32] and reinforce the role of cement stabilization in improving long-term performance.

Moisture ingress into the block can occur in liquid form, through precipitation or capillary rise, or as vapor processes such as condensation or adsorption. Evaporation is the main route for moisture loss, so wall moisture depends on both liquid exposure and overall vapor dynamics. Seasonal fluctuations strongly affect moisture levels, with higher values during rainy periods and lower levels in dry seasons. These fluctuations add complexity to moisture behavior and should be factored into durability evaluations and design planning. Moreover, the role of moisture transport mechanisms and seasonal impacts has been extensively studied in relation to the hydraulic performance of stabilized soil blocks, highlighting their relevance in assessing long-term durability [

50].

5.3. Cement Savings and Decarbonization Potential

The experimental results confirmed that blocks stabilized with 6% cement content met the minimum structural strength requirements for wall construction, making this the optimal mix for technical and environmental performance. Each block (22 cm × 22 cm × 10 cm) requires approximately 0.502 kg of cement. With 21 blocks per m2, the cement consumption per square meter is: 21 × 0.502 = 10.54 kg (plus 1.5 kg for pointing), approximately 12.04 kg/m2.

For a 100 m2 wall, this equals 1204 kg (approximately 1.2 tons). In comparison, Hollow Concrete Blocks (HCBs), including plastering and mortar, consume:

This represents cement savings of:

Given that each ton of cement emits approximately 0.8 tons of CO

2 [

51], these savings correspond to 1.4–2.0 tons of CO

2 emissions avoided per 100 m

2 wall.

Global projection: Low-income housing and decarbonization potential.

According to UN-Habitat, an estimated 96,000 new homes need to be built daily, approximately 35 million affordable homes annually to close the global housing gap by 2030 [

52].

Assuming an average house size of 50 m2 and wall area of 50 m2:

HCB Class C: 1490 kg per house → 52.15 million tons/year

CSEB (6%): 630 kg per house → 22.05 million tons/year

Annual savings: ~30 million tons of cement

CO2 avoided: ~24 million tons/year

These projections underscore the significant potential of CSEBs in achieving Paris Agreement targets and advancing SDGs 1, 11, 12, and 13. Scaling up CSEB adoption globally could significantly reduce the embodied carbon while addressing housing affordability and social equity. The confirmation of 6% cement content as optimal aligns with the theory of decarbonization, which emphasizes reducing embodied carbon in building materials. Cement production accounts for approximately 8% of global CO

2 emissions [

3], making material substitution critical for climate mitigation. By reducing cement consumption by over 50%, CSEBs offer a practical solution for low-carbon construction.

This performance advances the following global goals:

Paris Agreement and UNEP’s Net-Zero Roadmap: Promotes regenerative, locally sourced materials;

SDG 1 (No Poverty): Enables affordable housing through local production;

SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities): Encourages resilient, resource-efficient building;

SDG 12 (Responsible consumption): Advances circular economy principles;

SDG 13 (Climate Action): Reduces embodied carbon in construction.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study investigated the performance of compressed stabilized soil blocks (CSEBs) stabilized with Pozzolana cement, with a focus on mechanical strength, water absorption, and environmental sustainability. The findings demonstrate that CSEBs, when properly designed and produced, can meet the structural and durability requirements while offering significant environmental advantages over conventional masonry units. Key results include confirming 6% cement as optimal for strength and durability, achieving >2 MPa compressive strength and <15% water absorption, and demonstrating over 50% cement savings compared to hollow concrete blocks. These findings are discussed under technical performance, environmental implications, practical considerations, social dimensions, and future research

6.1. Technical Performance

Experimental results confirmed that increasing cement content significantly improves compressive strength and durability in CSEBs. At a constant compaction pressure of 10 MPa, raising cement content from 4% to 8% yielded a 110% gain in compressive strength. Blocks with 6% cement achieved 2.1 MPa at 28 days and 3.2 MPa at 56 days, meeting the ES structural requirements (>2 MPa). Water absorption decreased with higher cement content, with blocks containing 6% cement recording 14.2%, well below the recommended 15–20% threshold for durability.

A key optimization insight is the combined influence of cement content and compaction pressure: pressure can partially substitute for higher cement content. For example, a block with 8% cement at 10 MPa (2.6 MPa strength) performed comparably to one with 10% cement at 8 MPa (2.6 MPa strength), both exceeding the ES standards. This finding is critical because many small-scale producers apply pressures below 8 MPa, which compromises strength and durability. Prioritizing compaction pressure rather than increasing cement content reduces the costs and embodied carbon, making CSEB production more sustainable and affordable.

The ideal soil composition for CSEBs was approximately 75% sand and 25% combined silt and clay, with a minimum of 10% clay to ensure cohesion and workability. Soil sourced from the Kara area of Addis Ababa (70% sand, 16.25% silt, 13.75% clay) proved suitable for block production, highlighting the importance of site-specific soil testing and mix optimization.

6.2. Environmental Implications

The investigation establishes CSEBs as an environmentally advantageous and sustainable alternative to conventional masonry units. By utilizing locally available soil and incorporating Portland Pozzolana Cement (PPC) at an optimal 6% content, CSEBs achieve the necessary structural performance while substantially reducing cement consumption. For a standard 100 m2 wall, CSEBs require approximately 1.2 tons of cement compared to 2.98–3.68 tons for hollow concrete blocks (HCBs), resulting in cement savings of 1.8–2.5 tons—an over 50% reduction. Given that each ton of cement emits approximately 0.8 tons of CO2, this translates to 1.4–2.0 tons of CO2 emissions avoided per 100 m2 wall.

When scaled to meet global affordable housing needs, estimated at 35 million homes annually, CSEBs could reduce cement demand by approximately 30 million tons per year, avoiding up to 24 million tons of CO2 emissions annually. These results demonstrate that CSEBs not only meet the technical and durability standards but also align with global decarbonization goals, including the Paris Agreement and UNEP’s Net-Zero Roadmap. Furthermore, the use of PPC, which incorporates industrial by-products, enhances the environmental performance of CSEBs by further lowering the embodied carbon. Thus, CSEBs offer a practical and scalable solution for reducing the carbon footprint of the built environment, particularly in low- and middle-income contexts where sustainable and affordable housing is urgently needed.

6.3. Practical Considerations

Effective quality control is essential for ensuring consistent block performance. Key factors include soil selection, moisture content, compaction pressure, and curing practices. Based on the study findings, producers should prioritize achieving compaction pressures of at least 8–10 MPa, as this significantly enhances strength and allows for lower cement content without compromising durability. For example, blocks with 8% cement at 10 MPa performed comparably to those with 10% cement at 8 MPa, both exceeding the structural standards. This optimization reduces costs and embodied carbon.

Moisture control measures are equally critical. Given the observed water absorption trends, plastering the first two courses of walls and designing roof overhangs are recommended to minimize moisture ingress. In small-scale or rural contexts, simple field tests for soil grading and trial block production can serve as cost-effective quality assurance measures. Training local producers on soil testing, compaction techniques, and curing practices can further improve block quality and support the wider adoption of CSEBs in affordable housing projects.

6.4. Social and Policy Dimensions

Despite their technical and environmental merits, CSEBs often face social resistance due to perceptions of earth construction as inferior or “low-cost”. Addressing this requires coordinated efforts from architects, engineers, policymakers, and educators to promote awareness and acceptance. Integrating CSEBs into affordable housing initiatives can simultaneously address housing shortages and advance sustainable development goals.

6.5. Future Research

To enhance the versatility of CSEBs, it is advisable to pursue further investigations in the following domains:

Development of long-term durability models under varying climatic conditions;

Performance evaluation of CSEBs made from diverse soil types, including clay-rich and marginal soils;

Investigation of chemical and organic soil components that inhibit cement hydration;

Exploration of alternative or supplementary stabilizers to enhance performance and reduce costs.

These findings affirm that CSEBs stabilized with Pozzolana cement represent a technically viable and eco-friendly option for sustainable construction. When supported by proper design, quality control, and policy support, CSEBs can significantly contribute to lowering the carbon impact of the built environment. Moreover, they present an opportunity to address urgent housing needs in a resource-efficient and socially inclusive manner.

_Su.png)