Abstract

Jordan’s aging population faces a critical challenge: a strong cultural preference for aging at home, rooted in Islamic ethics of familial care (birr al-wālidayn), conflicts with housing stock that is largely unsafe and inaccessible. This first national mixed-methods study examines the intersection of home modifications, socio-economic barriers, and cultural constraints to aging in place. Data from 587 surveys and 35 interviews across seven governorates were analyzed using chi-square tests, linear regression, and thematic coding. Results indicate that while physical modifications significantly improve accessibility to key spaces like kitchens and reception areas (majlis) (χ2 = 341.86, p < 0.001), their adoption is severely limited. Socio-economic barriers are paramount, with 34% of households unable to afford the median modification cost of over $1500. Cultural resistance is equally critical; 22% of widows avoid modifications like grab bars to prevent the ‘medicalization’ of their home, prioritizing aesthetic and symbolic integrity over safety. The study reveals a significant gendered decision-making dynamic, with men controlling 72% of structural modifications (β = 0.27, p < 0.001). We conclude that effective policy must integrate universal design with Islamic care ethics. We propose three actionable recommendations: (1) mandating universal design in building codes (aligned with SDG 11), (2) establishing means-tested subsidy programs (aligned with SDG 10), and (3) launching public awareness campaigns co-led by faith leaders to reframe modifications as preserving dignity (karama) (aligned with SDG 3). This approach provides a model for other rapidly aging Middle Eastern societies facing similar cultural-infrastructural tensions.

1. Introduction

The global population is aging at an unprecedented rate, with projections indicating that the proportion of individuals aged 60 and older will double by 2050 [1]. This demographic shift is notably pronounced in the Arab world, particularly in Jordan, where significant changes arise from declining fertility rates and increased life expectancy. By 2050, older adults in the Arab region are expected to constitute 19% of the population, rising from 7% in 2010 [1]. Despite a cultural preference for aging within familial homes—rooted in Islamic values that emphasize family responsibility in elder care [2,3], the reality is that many residential environments in Jordan are inadequately equipped to address the accessibility and safety needs of the elderly. This misalignment between cultural ideals and infrastructural realities represents a significant challenge for aging individuals in Jordan.

While aging in place, the ability to live safely and independently in one’s home and community, reflects a universal aspiration supported by improved quality of life and reduced healthcare costs [4,5], global research underscores the necessity for home modifications, including grab bars, ramps, and accessible layouts. However, much of the global housing stock, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, remains inaccessible and poorly designed to accommodate the elderly, making modification financially unfeasible [1]. This demographic transition necessitates a nuanced understanding of how cultural values shape the experiences of older adults. In particular, the collectivist nature of Arab societies influences familial obligations and caregiving roles, creating a complex dynamic between individual needs and community expectations.

The unique dynamics of aging in place in the Arab context are heavily influenced by socio-cultural norms. Islamic teachings emphasize birr al-wālidayn (filial piety), obligating families to care for their elders within the home rather than resorting to institutionalization [2]. This culturally grounded approach positions the home not only as a physical space but also as a symbol of intergenerational solidarity. However, housing designs in the Arab world often neglect to adopt universal design principles, thereby leaving elderly residents susceptible to falls, mobility issues, and social isolation [3]. In Jordan, while 87.6% of older adults own their homes [6], over 60% reside in environments characterized by unsafe bathrooms, narrow doorways, and inaccessible kitchens—features that do not accommodate their evolving needs. Moreover, the cultural significance of communal spaces, such as the majlis, highlights the interplay between spatial design and social traditions. These spaces not only serve functional purposes but also embody cultural identity and familial bonds, which can impede the adoption of universal design principles when such modifications are perceived to compromise traditional aesthetics.

In the context of Jordan, cultural values significantly influence decision-making processes regarding elder care. Familial structures rooted in Islamic teachings emphasize the collective responsibility of family members in caring for their elderly, often restricting the agency of elderly individuals when it comes to home modifications [2]. Specifically, gender roles within the family often dictate how decisions are made and who has the final say. Traditional expectations may lead to a scenario where, despite a pressing need for home adaptations, the desires of older adults can be overlooked in favor of what is perceived as more socially acceptable or tradition-aligned [3]. This paper seeks to explore these dynamics more closely to understand how cultural norms specifically influence both elderly individuals and their family members in the decision-making process regarding home modifications.

This unique dynamic presents a significant research challenge. While global studies often focus on institutional solutions, such as subsidized modifications in Sweden [7], Jordan’s model of familial care requires context-specific, culturally adaptive design solutions that harmonize Islamic principles with universal design in multigenerational settings.

Despite notable demographic changes and challenges faced by the elderly in Jordan, the literature remains lacking. Research on aging in place primarily emphasizes Western contexts, largely overlooking the complexities inherent in Middle Eastern societies [2]. This body of work typically fails to account for the intricate interactions among cultural norms, economic realities, and housing policy frameworks critical to the Jordanian context. Although universal design (UD) principles are thoroughly explored in Europe and North America [8,9,10], their applicability and relevance in Arab environments—particularly those influenced by Islamic care ethics and multigenerational living—warrant further examination. Additionally, socio-cultural barriers, such as the stigma surrounding home modifications that may imply dependency, along with pressing economic constraints, often remain unaddressed, despite being crucial to understanding adoption rates [3]. This absence of context-specific research is exacerbated by stagnant policies, as current building codes in Jordan do not enforce essential accessibility standards, thus maintaining exclusionary design practices [6].

A crucial literature gap pertains to various socio-cultural barriers that can hinder the acceptance of home modifications. Familial caregiving traditions often discourage families from making changes due to stigma or the fear that adaptations could signal the need for assistance [3]. Economic challenges are significant as well; in Jordan, 14.4% of households live on low incomes [11], often lacking the financial resources necessary for vital modifications, compounded by a scarcity of subsidy programs. Additionally, there is notable policy inertia; current building codes in Jordan and neighboring regions fail to enforce crucial accessibility standards, thereby perpetuating exclusionary design practices [6]. Prior research has yet to adequately integrate Islamic principles, such as birr al-wālidayn, with universal design within multigenerational contexts where the needs for privacy and communal space converge.

A significant problem persists in that there is a profound misalignment between the Islamic ethical ideal of familial home-based care and the physical reality of Jordan’s housing infrastructure, which is largely ill-equipped for an aging population. This gap is exacerbated by a lack of context-specific research that integrates the principles of environmental gerontology and universal design with the socio-cultural and economic realities of the Arab world. Consequently, families are left without adequate guidance or support, forced to choose between honoring cultural traditions and ensuring the safety of their elders. This study is needed to bridge this gap, providing empirical evidence and a culturally congruent framework to inform policy and design interventions that allow Jordanian elders to age in place safely, with dignity, and without compromising their cultural values.

This study seeks to fill these critical gaps through a nationally representative, mixed-methods examination of aging-in-place barriers in Jordan. The research is guided by three primary objectives:

- To investigate how cultural values, economic constraints, and policy frameworks intersect to affect aging-in-place outcomes, especially considering that 40% of older adults have resided in the same home for more than 40 years [6].

- To apply and integrate the theoretical frameworks of environmental gerontology (EG) and universal design (UD) to develop a ‘Cultural-Environmental Congruence’ model tailored to the Jordanian context, contextualizing person-environment interactions [12] while advocating for built environments accessible to all [13].

- To present empirical insights on the barriers encountered, drawing from an analysis of 587 surveys and 35 interviews across seven governorates, highlighting socio-cultural resistances and economic challenges, and propose a policy framework that incorporates Islamic values into universal design principles.

In conclusion, this study promotes a paradigm shift in Jordan’s housing policies, advocating for initiatives that combine universal design with Islamic caregiving values. By connecting safety with dignity (karama) and tradition, actionable strategies are provided to transform Jordan’s housing environment into age-friendly spaces, offering valuable lessons for other rapidly aging Middle Eastern societies. Suggested reforms may include subsidizing home modifications or improving accessibility at mosque-based community centers to tackle socio-cultural barriers while maintaining affordability. These adjustments have the potential to convert residences into settings where elders can age safely, autonomously, and with dignity, harmonizing tradition with innovation.

2. Literature Review

This research bridges global aging-in-place theories with Jordan’s socio-cultural context, emphasizing the interplay of cultural norms, economic constraints, and housing design. The review is structured to first establish the global perspective before narrowing its focus to the Arab and Jordanian context.

2.1. Global Perspectives on Aging in Place and Universal Design

Aging in place, the ability to remain in one’s home and community despite physical or cognitive declines, is a widely recognized ideal linked to autonomy, emotional well-being, and reduced institutional care costs [4,5]. Early studies on aging in place, such as those by [14,15,16,17], highlighted the growing need for housing adaptations to support elderly independence, a trend now evident in Jordan’s demographic shift. The concept encompasses both spatial dimensions, where maintaining a familiar location is vital, and psychological dimensions, which underscore the importance of independence and identity [4,18]. For older adults, the home transcends mere physical structure; it serves as a repository of memories, social bonds, and cultural identity [19,20].

In Western contexts, aging-in-place policies often prioritize institutional support systems, such as subsidized modification or community care programs [7]. Furthermore, Western nations have successfully integrated universal design—which advocates for creating environments usable by individuals of all ages and abilities—into their policies, such as through the U.S. Americans with Disabilities Act [13,21]. Comprehensive policies in countries like Sweden, which subsidizes 81% of modifications through public funding, ensure widespread access to necessary adaptations [7].

2.2. Aging in Place in the Arab and Jordanian Context

However, in Arab societies, including Jordan, familial caregiving rooted in Islamic values significantly influences elder care dynamics, creating a distinct context [2]. This cultural framework positions the home as a space for intergenerational duty (birr al-wālidayn), where elders are cared for by family members rather than being placed in external institutions [3,22]. Such practices coexist with housing designs predominantly made for younger, able-bodied individuals, leading to a paradox where, despite 87.6% of Jordanian elders being homeowners [6], over 60% live in homes lacking essential safety features, such as wide doorways and safe bathrooms, unsuitable for aging populations. The adoption of universal design principles in the Arab world has been limited, and in Jordan, the absence of enforceable accessibility standards in building codes perpetuates exclusionary home environments [6,9,23,24].

2.3. Aging in Place: Home Environments and Personal Space

Islamic teachings highlight the moral imperative of familial responsibility concerning elder care, which sharply contrasts with Western models that normalize institutionalization. For example, in Sweden, 22% of elders over 80 reside in nursing homes [25], while in Jordan, institutional care is largely stigmatized. In Jordanian culture, multi-generational households are common, with homes often modified informally, such as relocating elders to ground-floor accommodations to address mobility challenges [6,26,27,28]. However, these adaptations seldom adhere to universal design principles, which heightens the risks of falls and social isolation for elderly residents. Qualitative studies reveal that maintaining cultural norms while addressing practical needs is a fundamental challenge. For instance, Turkish families prioritize hürmet (respect) by ensuring elders remain at home, yet they resist substantial structural changes like ramps due to fears of medicalizing their homes [29]. Similarly, Lebanese elders have expressed emotional distress when modifications disrupt the traditional layouts of majlis (reception rooms), spaces that are emblematic of familial hospitality [3,30]. These findings underscore the necessity for culturally sensitive design frameworks that effectively balance safety with the preservation of cultural integrity [31].

2.4. Accessibility and Aging in Place: Universal Design in Non-Western Contexts

Ref. [32] outlines key architectural strategies for universal design, many of which remain absent in Jordan’s housing policies despite their potential to improve accessibility. Universal design, which advocates for creating environments usable by individuals of all ages and abilities, is a cornerstone of aging-in-place research [13]. Regional case studies illuminate both the challenges and opportunities for applying universal design in non-Western contexts. In Turkey, research conducted by [29] indicates that modification of historic homes to include ramps and widened doorways has enhanced mobility, though it often faces resistance due to aesthetic concerns. Conversely, Lebanon’s Aging in Dignity initiative effectively collaborated with local Islamic NGOs to subsidize bathroom grab bars and non-slip flooring, aligning essential modifications with cultural values of dignity (karama) [3]. Religious institutions, such as mosques and Islamic charities, possess significant potential in promoting accessibility; for example, in Iran, some mosques have incorporated ramps and supportive prayer mats for elderly worshippers [33,34], while Jordan could leverage funds to support modification efforts for low-income families, an initiative yet to be realized [2].

2.5. Home Modifications and Economic Barriers

Home modifications refer to adaptations made to residential environments that enable aging individuals to maintain their independence, and they are critical for addressing the growing disconnect between aging populations and housing designed primarily for younger occupants [35,36,37]. These adaptations range from temporary, low-cost interventions, such as removing tripping hazards [38], to permanent structural changes like installing ramps or bathroom grab bars [39]. Globally, research indicates that these modifications can significantly reduce fall risks by 32%, delay institutionalization by an average of 18 months, and lower healthcare costs by 22% [40,41,42]. Ref. [43] demonstrated that targeted home modifications reduce long-term care costs, a finding relevant to Jordan’s need for subsidy programs. However, in Jordan and similar contexts, numerous economic, cultural, and policy barriers limit the adoption of essential adaptations.

The financial burden of modification is particularly pronounced in low-income environments. The median cost for modifying a bathroom in Jordan is about $1200, which equates to roughly 40% of the average household’s annual income [44]. This financial strain forces families to prioritize urgent repairs, such as fixing leaky roofs, over preventative modifications that could enhance safety, such as the installation of grab bars. Compounding this issue, Jordan’s rental laws often allow landlords to deny requests for modifications, leading to the displacement of elderly tenants who may require those adaptations for safe living [45,46]. Cultural resistance also plays a significant role; it is common for many Jordanian families to delay needed modifications due to concerns that such changes could stigmatize elders or disrupt the traditional aesthetics of their homes, which frequently feature open courtyards and stone flooring [3,6].

These barriers of economic exclusion and cultural resistance are exacerbated by policy inertia. Unlike France’s Habitat Adapté program, which provides interest-free loans to assist homeowners with modification [7], Jordan currently lacks a comprehensive national framework for subsidy programs, leaving families to navigate their aging-in-place challenges without adequate support. Furthermore, the need for home modifications is rising globally, as the demographic trends indicate an aging population increasingly requiring supportive living arrangements [47,48,49]. Supporting older adults to live independently in their own homes is a cost-effective strategy compared to institutional care, as studies show that ensuring accessibility can mitigate healthcare costs and improve living conditions [36,50,51]. Overall, while home modifications present a vital strategy for fostering aging in place, significant economic and cultural barriers remain that must be addressed through thoughtful policy reform and community action.

2.6. Aging in Place and Psychological Attachment

The psychological significance of home to older adults transcends physical safety, especially for Arab elders, as homes symbolize ancestral heritage, familial continuity, and religious identity [19]. Ref. [20] found that emotional attachment to home often outweighs practical concerns, a phenomenon also observed among Jordanian elders who resist modifications to preserve familial spaces. In Jordan, about 40% of elders have lived in the same home for over 40 years, often regarding it as a living archive of family history [6]. This deep emotional bond complicates decisions regarding relocation, even when safety concerns arise. For Arab elders, the concept of home is closely associated with sumud (steadfastness), a cultural value that emphasizes resilience and rootedness [3]. Modifications that alter traditional home layouts risk undermining this symbolic significance, as exemplified by replacing stone floors with slip-resistant tiles, which, while enhancing safety, disrupt the aesthetic continuity cherished by residents [29].

To achieve successful interventions, it is crucial to honor the cultural attachments of older adults while addressing safety risks. In rural Jordan, families have preserved their heritage homes by discreetly adding ramps behind structures, which helps maintain the integrity of their facades [6]. Similarly, Chinese concepts such as granny flats exemplify how modern accessibility can be harmoniously integrated with traditional courtyard designs [52]. Thus, the need for modifications must extend beyond safety and adapt to the emotional connections elderly individuals have with their homes.

2.7. Aging in Place and Personal Characteristics

Aging in place is intricately linked to the personal characteristics of older individuals, which influence their ability to live safely and independently within the community. Attributes such as resilience, adaptability, independence, mental engagement, and overall health significantly enhance the capacity for successful aging in place. Support systems need to be effective and low-cost, enabling the elderly to adjust to changes in their environments while preserving their independence and resilience [53]. Successful aging in place requires a comprehensive approach that includes responsive services, practical assistance, financial support, physical and mental activities, companionship (from family, friends, neighbors, or pets), reliable transport, and safety measures [53]. Additionally, older adults with higher incomes tend to relocate from their homes but often choose to remain within their communities to maintain their social ties [54].

Existing literature has robustly documented how cultural frameworks shape the dynamics of decision-making in elder care, particularly in Middle Eastern societies. For instance, a study by [2] indicates that familial hierarchies significantly influence adaptation strategies, often positioning elder males as the primary decision-makers, while elder females’ voices may be subdued or overlooked [3]. This gendered division can hinder necessary modifications due to stigma associated with perceived dependency or ‘medicalization’ of homes.

2.8. Theoretical Framework: Cultural-Environmental Congruence

The aims of this research necessitate a nuanced integration of environmental gerontology (EG) and universal design (UD) to create a robust theoretical framework. While EG emphasizes the ‘person-environment fit’ [12] and UD advocates for inclusivity in design [13], these principles often stand in tension with the collectivist cultural norms and practices prevalent in Jordan.

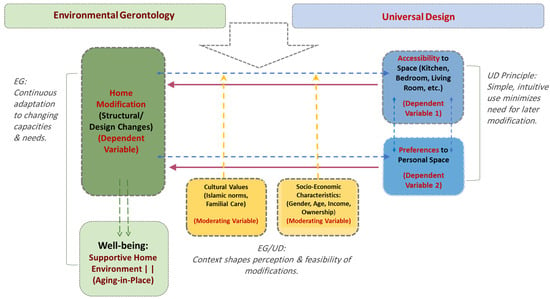

To address this conflict and provide a testable model for this context, we propose a Cultural–Environmental Congruence framework (see Figure 1). This model posits that the relationship between home modifications (the dependent variable) and their effectiveness is not direct but is mediated by three key factors intrinsic to the Jordanian socio-cultural context:

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of Home Modification Dynamics for Older Adults.

- Familial Authority: The influence of gendered control over home modifications shapes decision-making processes. Research indicates that familial hierarchies can complicate the implementation of necessary changes, particularly in a society where elders often rely on family members for support [2,3].

- Symbolic Spaces: The aesthetic and functional importance of traditional reception areas (majlis) often outweighs purely accessibility-based considerations. Adaptations perceived to compromise the cultural significance of these spaces face significant resistance.

- Economic Liquidity: High rates of homeownership do not equate to the ability to modify a home. Economic constraints significantly limit the capacity to implement needed modifications, creating a critical barrier despite asset ownership [6].

This framework is a novel theoretical contribution that guides our entire research design and analysis. It moves beyond a direct cause-and-effect view and provides a structured lens through which to analyze our mixed-methods data. It allows us to hypothesize how cultural attitudes towards family, identity, and economic realities interact to shape the experiences of Jordanian elders attempting to age in place. The integration of these elements informs both our methodology and the interpretation of results, enabling a comprehensive approach to addressing the unique challenges facing this demographic.

3. Research Methods

This mixed-methods study examines the interplay between home modifications, accessibility, socio-economic factors, and cultural values in supporting Jordan’s aging population. The methodology employs a sequential mixed-methods design (QUAN → QUAL) to (a) quantify modification patterns across seven governorates, (b) contextualize barriers through lived experiences, and (c) triangulate findings via the cultural-environmental congruence model (CEC Model).

3.1. Research Design

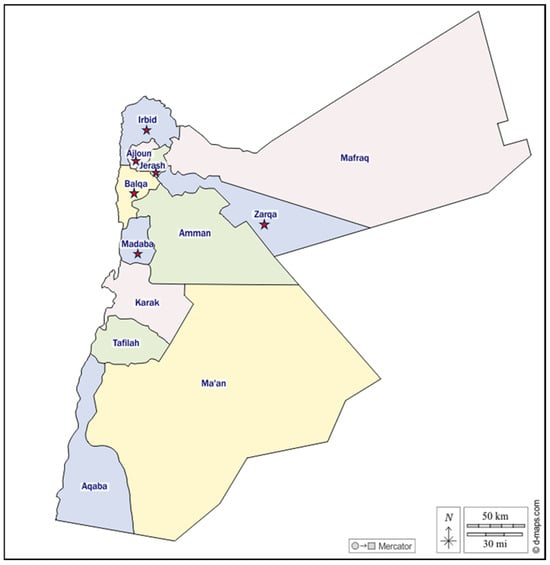

The research design incorporates both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods across seven governorates in Jordan—Irbid, Jerash, Ajloun, Mafraq, Zarqa, Salt, and Madaba (see Figure 2). These regions were selected to capture urban–rural diversity, economic disparities, and varying architectural characteristics (e.g., Irbid’s high-density apartments vs. Madaba’s heritage homes), allowing for contrasting contexts in evaluating housing adaptations.

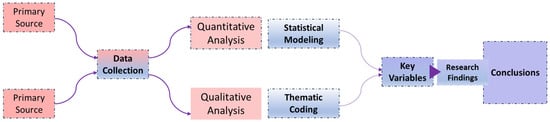

Figure 2.

Causal framework of methodology and data flow.

This mixed-methods design was deemed the most appropriate for the study’s objectives as it allowed for both breadth and depth of understanding. The initial quantitative phase (QUAN) identified overarching patterns and statistical relationships regarding home modifications and accessibility across a large, representative sample (n = 587). This was essential for establishing generalizable facts about the prevalence and correlates of modifications. The subsequent qualitative phase (QUAL) was then crucial for explaining the ‘why’ behind these patterns—exploring the cultural meanings, familial decision-making processes, and deeply held values that quantitative data alone could not capture. This sequential approach enabled robust triangulation, where the quantitative results provided a framework to be explored and contextualized by the rich, nuanced qualitative narratives, ensuring findings were both statistically sound and culturally grounded.”

This design intentionally blended deductive theory-testing (e.g., examining gendered authority in H2) with inductive exploration of unanticipated cultural barriers (e.g., stigma against ‘medicalizing’ homes). The Cultural–Environmental Congruence Model provided scaffolding for deductive analysis, while remaining flexible enough to incorporate context-specific discoveries through constant comparative methods [55]. As illustrated in Figure 2, our methodology integrates primary and secondary sources through mixed-methods analysis, where quantitative data underwent regression modeling and qualitative responses were thematically coded to enable robust identification of key variables.

Field research involved a structured questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. The quantitative segment featured a robust dataset obtained through 587 surveys, representing the elderly population of Jordan through stratified random sampling. The sampling targeted adults aged 60 and above living in private homes, yielding an 84% response rate from an initial target of 700 participants. Data collection focused on key variables, including home modifications, accessibility to various living spaces, and socio-economic characteristics.

The qualitative component included in-depth interviews with elderly residents from diverse communities. A total of 35 interviews were conducted using convenience sampling through local NGOs, ensuring representation of varied demographic backgrounds. Participants were aged 70 and older and had resided in their homes for at least ten years to capture long-term experiences pertinent to aging in place. The semi-structured interviews were designed to delve into participants’ experiences and the dynamics of decision-making within their families. Specific questions included: ‘Who usually makes the decisions regarding home modifications in your household?’ and ‘How do you feel about the modifications? Are there any decisions that you wished had been made differently?’ to elicit insights into familial roles and cultural expectations.

3.2. Sampling Strategy

The sampling strategy aimed to capture Jordan’s geographic, economic, and cultural diversity. The quantitative sample included 587 elderly individuals aged 60 and above from seven governorates—Irbid, Jerash, Ajloun, Mafraq, Zarqa, Salt, and Madaba—representing a mix of urban, semi-urban, and rural settings. A stratified random sampling technique was employed based on governorate and urban/rural classification to achieve representativeness. Due to the sensitivity of income as a demographic variable and the lack of available data, we focused on housing typologies and general living conditions instead of income level for stratification.

This approach captured significant variability: urban areas like Irbid feature modern accommodations, whereas rural regions like Ajloun often have traditional homes that may lack essential modifications. This ensures our findings can be generalized to the broader elderly population in Jordan while highlighting specific regional discrepancies.

For the qualitative sampling, elders aged 70 and older were recruited via local NGOs and mosques to address specific challenges of advanced aging. The sample included 35 participants (53% male, 47% female), with 62% residing in traditional homes versus 38% in modern apartments, providing diverse insights into aging experiences across different living environments.

3.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

This study investigates the complex dynamics of aging in place within the Jordanian context. The research framework is anchored in key themes derived from field interviews and literature, focusing on how home modifications, accessibility, socio-economic factors, and cultural values intersect to impact the experiences of elderly individuals. This approach sought to explore a range of areas, including: the characteristics of the governorates and their infrastructure; housing typologies and ownership; social structures and cultural values at the village and household level; perceptions of control and attachment to home; and the prevalence of modifications.

3.3.1. Research Questions

The following research questions guided the study and helped to frame the investigation:

- Cultural and Infrastructure Context: What are the characteristics of the governorates studied regarding infrastructure, cultural context, and how do these factors influence the aging population’s ability to remain in their homes?

- Social Structures and Family Dynamics: How do social structures, both at the village and household levels, influence the experiences and caregiving dynamics for the elderly?

- Modification Practices and Barriers: What modifications have been made to the homes of the elderly, and what factors (cultural, economic, and social) act as barriers to further modifications?

- Perception and Attachment: How do elderly individuals perceive their control over their living conditions and their emotional attachment to specific areas of their homes, and how do these perceptions influence their views on modifications?

3.3.2. Core Hypotheses

The primary research hypotheses tested in this study are as follows:

H1: A supportive home environment for Jordanian elders is associated with accessibility to key functional spaces, such as the kitchen, bedroom, living room, and reception area, and personal space modifications.

- H1a: Home modification is significantly associated with accessibility to various domestic spaces.

- H1b: Home modification is significantly associated with preferences for personal space.

H2: Home modification practices correlate with socio-economic characteristics, including age, gender, income, and housing ownership.

3.3.3. Variables and Measures

The major constructs and variables related to the conceptual framework are outlined as follows:

Dependent Variable—Home Modification: This variable refers to the adaptations made to enhance the safety and accessibility of the home environment. It is measured by considering modifications across the following areas: kitchen (modification of kitchen); bedroom (modification of bedroom); living room (modification of living room); and reception room (modification of reception room). This was quantified using responses to an integrated question (Q27), which assesses the average modifications made across these four key spaces.

Independent Variable 1—Accessibility to Domestic Space: This variable captures how easily elderly individuals can access different spaces within their homes. It is measured using a four-level scale from question Q26 that assesses accessibility levels in the kitchen, bedroom, living room, and reception room.

Independent Variable 2—Personal Space Preference: This variable reflects the emotional attachment to preferred areas within the home. It is defined using responses to the open-ended question Q28 that solicits information on participants’ favorite spaces in their homes.

Control Variables—Socio-Economic Characteristics: These variables encompass various factors that may influence the experience of aging in place. It is defined by the following: gender; age; marital status; assigned private rooms; ownership status; length of residence; number of family members; and number of rooms in the household.

3.4. Data Collection and Research Instruments

Quantitative Survey: The researcher utilized a structured survey questionnaire consisting of 33 items divided into four sections assessing home modifications, accessibility, personal space preferences, and socio-economic characteristics. Questions employed formats suited to their construct; for instance, “Have you modified your kitchen in the past 5 years?” used a binary (yes/no) format for clear quantification of modifications, while accessibility was measured with questions like “How easily can you access your kitchen?” on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Very Difficult, 5 = Very Easy). Personal space inquiries used open-response formats to gather rich, qualitative insights into respondents’ favored areas.

Validation and Reliability: A rigorous validation process was conducted, including pilot testing with 50 participants, which resulted in revisions for enhanced clarity and cultural relevance. The psychometric properties of the scales are presented in Table 1. Reliability was assessed using metrics tailored to each scale type, aligning with psychometric best practices. Cronbach’s α was used for multi-point scales (Accessibility, Personal Space Preference, Socio-Economic Factors), with α ≥ 0.70 indicating acceptable reliability [56]. The KR-20 statistic was employed for the binary Home Modification scale [57], where values of 0.60–0.70 signify moderate reliability [58].

Table 1.

Reliability analysis of survey scales using Cronbach’s Alpha.

The “Accessibility” scale yielded a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.79, reflecting acceptable internal consistency. The “Home Modification” scale demonstrated moderate reliability (KR-20 = 0.68). The “Personal Space Preference” scale scored 0.82, indicating good internal consistency, and the “Socio-Economic Factors” scale achieved a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.70, suggesting moderate reliability. Collectively, these findings support the reliability of the survey instruments, enhancing confidence in the validity of the conclusions drawn.

Construct Validity: Construct validity was established through content validity and theoretical grounding. Survey items were adapted from well-validated instruments in environmental gerontology [8,39] and universal design [13], with cultural adaptation verified through expert review and the pilot testing process. Given the discrete, theory-driven nature of the constructs—where Accessibility, Modification, and Socio-Economic Factors represent established latent variables—exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was deemed redundant [59]. Instead, convergent validity was demonstrated through mixed-methods triangulation, where quantitative patterns aligned with qualitative narratives about cultural barriers.

Qualitative Interviews: The qualitative component involved semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions designed to explore cultural norms influencing aging, familial responsibilities, and barriers to modifications. A thematic analysis was employed to organize major themes reflecting participants’ lived experiences. Triangulation was achieved by cross-validating qualitative findings with quantitative data, allowing for the contextualization of statistical patterns (e.g., correlating narratives of stigma with quantitative variables on modification preferences).

3.5. Research Setting

This research was conducted in different governorates of Jordan, namely Irbid, Jerash, Ajloun, Mafraq, Zarqa, Salt, and Madaba, see Figure 3:

Figure 3.

Governates of the study location in Jordan (Note: the red star shows the governorate included in the study). Source: https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=244724&lang=en, accessed 12 June 2025.

- Irbid: Located in the northern part of Jordan, Irbid is the second-largest city in the country. It is known for its educational institutions, including the renowned Yarmouk University. Its geographical location, close to the Syrian border, has also made Irbid a place of refuge for immigrants, contributing to its rich cultural diversity.

- Jerash: This city, situated in the north of Jordan, is renowned for its well-preserved Roman architecture. Jerash boasts a rich history and is a significant driver of tourism. It is a mix of cultural heritage and contemporary Jordanian life.

- Ajloun: Nestled in the highlands of north Jordan, Ajloun is famous for its medieval Ajloun Castle and lush forests. The area’s fertile landscapes support a primarily agriculture-based economy.

- Mafraq: Positioned near the borders of Syria, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, Mafraq has a distinct economy and social structure, largely due to the significant influx of refugees. It is a hub for industries such as textiles and dairy products.

- Zarqa: As the industrial center of Jordan, Zarqa houses a significant proportion of the country’s factories and contributes heavily to its economy. It has a vibrant workforce and exhibits an interesting blend of urban and rural styles of living.

- Salt: Salt is a historically rich city located in the Balqa Governorate. Known for its unique Ottoman architectural style, it is a blend of history, culture, and modern living.

- Madaba: Dubbed as the ‘City of Mosaics,’ Madaba is best known for its Byzantine and Umayyad mosaics, especially the famous 6th-century map of Jerusalem and the Holy Land. It has a delicate balance of cultural heritage and modernity.

These diverse locations provide rich grounds for the study, ensuring that a wide array of perspectives across cultural, social, and economic aspects is covered.

3.6. Data Analysis

The quantitative analysis began with descriptive statistics to summarize socio-economic variables using frequencies, means, and standard deviations. Chi-square tests examined associations between home modification practices and measures of accessibility, with effect sizes calculated using Cramér’s V to assess the strength of these associations. Linear regression analyses modeled socio-economic predictors of modification practices. Continuous modification scores were centered (mean = 1.59, SD = 0.42), and linear regression was selected due to its appropriateness for the non-binary nature of the dependent variable. Confidence intervals (95%) were calculated for regression estimates to provide additional context about the precision of these estimates. Model diagnostics included checks for multicollinearity using variance inflation factor (VIF) values. Although a common threshold is VIF < 10, we adopted a more conservative approach (VIF > 5) to mitigate potential multicollinearity. Consequently, income was omitted from the final model due to its high correlation with homeownership (VIF = 5.2), which would have inflated the variance of the coefficient estimates and compromised the reliability of the model.

Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic coding in NVivo software version 12, resulting in twelve main themes representative of participants’ experiences. Thematic codes included attachment and communal conflict. Member checking was integrated into the qualitative analysis to enhance credibility, allowing participants to review preliminary findings for resonance with their experiences. Thematic coding (NVivo 12) followed a hybrid approach: deductive codes reflected the Cultural–Environmental Congruence Model (Familial Authority, Symbolic Spaces, Economic Liquidity), while inductive codes captured emergent cultural barriers (e.g., ‘sumud’ [steadfastness]). Quotes validating each theme were cataloged for triangulation.

Ethical considerations included obtaining verbal informed consent adjusted for illiteracy and ensuring participant anonymity throughout the research process.

3.7. Methodological Rigor

The methodological rigor of this study is ensured through principles of trustworthiness, including prolonged engagement in the field over six months and peer debriefing. Thick descriptions of socio-economic contexts across the governorates enhance transferability, while an audit trail documenting coding decisions supports dependability. Limitations include potential sampling bias due to convenience sampling, which could lead to an overrepresentation of elderly people connected to local NGOs. Additionally, while self-reports provide insights, they must be viewed cautiously, as the physical accessibility of homes was not independently verified.

Through this mixed-methods approach, the study aims to develop a robust foundation for understanding the complexities of aging-in-place dynamics in Jordan. By integrating qualitative insights with quantitative patterns and triangulating diverse data sources, the methodology aspires to advance scholarly contributions and inform policy-relevant insights.

4. Analysis

This section synthesizes quantitative and qualitative findings to address the study’s hypotheses, organized around four key themes: cultural priorities versus physical barriers, economic constraints, gender dynamics, and policy disconnects. Guided by our theoretical framework (Figure 1), we first establish socio-demographic patterns and then test our hypotheses.

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.1.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Sample

Participant socio-economics are summarized in Table 2. Nearly half originated from northern governorates, with a balanced gender distribution (53% male, 47% female). A notable majority (87.6%) owned their residences, reflecting a strong trend toward homeownership. Marital status varied, with 32.9% widowed and 65.4% married. Most respondents (78.5%) had private rooms in their households.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for the sample socio-economic characteristics.

Length of residence indicates considerable stability: the mean was 29.47 years (SD = 17.44), with 40% having lived in the same home for over 40 years. Living arrangements showed that only 9% lived alone; the mean household size was 4.48 family members (SD = 3.44). Most households consisted of one to four rooms (72.5%), with an average of 3.94 rooms per residence (SD = 1.88).

4.1.2. Descriptive Analysis of the Dependent and Independent Variables

The distribution of major study variables is presented in Table 3. The dependent variable, home modification, demonstrates a mean of 1.59 (SD = 0.42). When examined by space, the highest modification frequency was in reception rooms (M = 1.65, SD = 0.48), followed by living rooms, bedrooms, and kitchens.

Table 3.

Descriptive distribution for the dependent and independent variables of the study.

The first independent variable, accessibility to space, had a mean of 1.84 (SD = 0.30). Accessibility levels were highest for the living room (M = 1.88, SD = 0.32) and reception room (M = 1.87, SD = 0.33). The second independent variable, personal space preference, had a mean score of 3.76 (SD = 1.25), highlighting substantial variation in individual attachment.

4.2. Synthesis of Hypotheses

To address our core objectives, we structured a sequential analytical framework: First, chi-square tests quantified modification–accessibility relationships (H1). Second, linear regression modeled socio-economic drivers of modifications (H2). Finally, qualitative themes contextualized statistical anomalies through the Cultural–Environmental Congruence Model.

4.2.1. Hypothesis 1

The Pearson Chi-square test revealed a strong association between home modification and overall accessibility to household spaces, χ2 (20, 587) = 341.86, p < 0.001 (Table 4), supporting the first hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1a.

Home Modification is associated with Accessibility to Domestic Spaces.

Table 4.

Pearson chi-square tests—home modification with accessibility to household space.

Significant associations were found for each specific space: kitchen χ2 (8, 587) = 207.89, p < 0.001; bedroom χ2 (4, 587) = 188.13, p < 0.001; living room χ2 (4, 587) = 95.11, p < 0.001; and reception room χ2 (4, 587) = 102.75, p < 0.001 (Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8). Modifications were concentrated in culturally significant reception rooms, a finding confirmed qualitatively.

Table 5.

Pearson chi-square tests—home modification with accessibility to kitchen.

Table 6.

Pearson chi-square tests—home modification with accessibility to bedroom.

Table 7.

Pearson chi-square tests—home modification with accessibility to living room.

Table 8.

Pearson chi-square tests—home modification with accessibility to reception room.

Interestingly, modifications were concentrated in areas aligning with Islamic and familial values—most notably reception rooms. This prioritization demonstrates that structural changes are intricately linked to cultural identity and social function, a finding confirmed by qualitative interviews.

Hypothesis 1b.

Home Modification is associated with Personal Space. The relationship between modifications and preferred spaces was not supported by the data, χ2 (20, 587) = 30.37, p = 0.06 (Table 9). Qualitative interviews illuminated this result, showing that attachment to favorite spaces is often deeply psychological and rooted in symbolism or memory rather than accessibility.

Table 9.

Pearson chi-square test—home modification with personal space.

4.2.2. Hypothesis 2

Home Modification is correlated with Socio-economic Characteristics

Linear regression revealed a significant association between socio-economic variables and home modification behavior, F (8, 586) = 13.59, p < 0.001 (Table 10).

Table 10.

Linear regression model summary—home modification with socio-economic characteristics.

As detailed in Table 11, significant socio-economic predictors were identified:

Table 11.

Linear logistic regression model for home modification with socio-economic characteristics.

- Gender (β = 0.27, p < 0.001) reflected patriarchal hierarchies.

- Age (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) indicated rising modification urgency among older cohorts.

- Assigned Private Room (β = 0.13, p = 0.002) underscored autonomy’s role.

- Ownership was non-significant (β = 0.02, p = 0.61) despite high homeownership rates, confirming liquidity constraints.

- Family size showed a negative, non-significant relationship (β = −0.05, p = 0.20), aligning with economic realities where resources are diverted to urgent repairs.

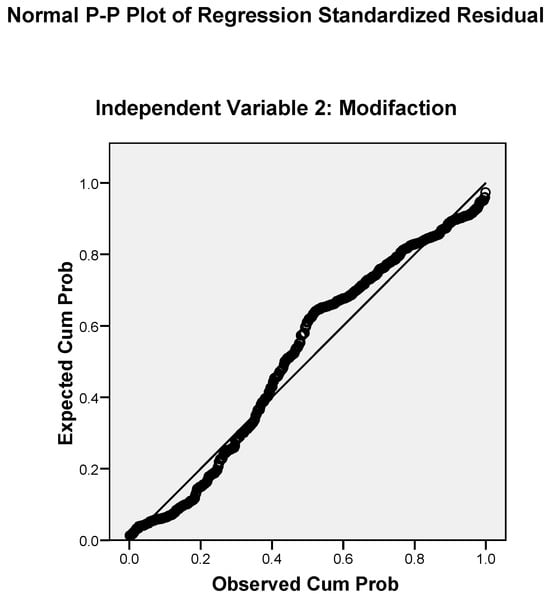

The analysis highlights a key economic paradox: homeownership does not guarantee adaptation capacity. The distribution of residuals indicated satisfactory model fit and normality (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Residual of the regression home modification with socio-economic characteristics (note: x-axis: predicted modification score; y-axis: residuals). Source: Researcher.

4.3. Qualitative Outcomes—Study Themes

The qualitative component of this study was organized into eleven principal themes, each capturing important socio-cultural, infrastructural, and psychosocial insights about the aging-in-place experience in Jordan. The determination of themes was derived inductively using NVivo 12, with themes (e.g., attachment, ’communal conflict’) validated through member-checking across the interview corpus. Each of the themes enhances the contextual understanding of the quantitative findings. As detailed, merging both datasets elucidates the complex interplay of cultural values, economic constraints, gender dynamics, and policy gaps affecting the aging population in Jordan, which are shaped not just by statistical patterns but by rich narratives of daily living.

Qualitative themes were systematically mapped to quantitative findings using a joint display (Table 12), using the Cultural–Environmental Congruence Model (Figure 1) as an integrative framework, with inductive codes capturing emergent cultural constructs. Familial Authority, Symbolic Spaces, and Economic Liquidity provided theoretical anchors for interpretation.

Table 12.

Joint Display: Triangulation of Quantitative Findings and Qualitative Themes: Evidence of Convergent Patterns.

For instance, low bathroom modification rates (6%, Table 12) converged with Theme 6 (Cultural Resistance), exemplified by widows avoiding ‘medicalized’ aesthetics to preserve family honor. Similarly, patriarchal modification control (β = 0.27, Table 11) aligned with Theme 7 (Gendered Authority), capturing male dominance in decision-making narratives. This triad structure—quantitative pattern → theoretical construct → verbatim evidence—ensures methodological coherence.

Theme 1—Governorates characteristics (Symbolic Spaces): Physical hierarchies (public → private domains) reflect cultural identity. Participant: ‘Stone fences mark our family lands—they’re like ancestors watching over us’ (Male, 76, Ajloun). Emerged from general descriptions of governorates and villages, which are often characterized by clustered rural settings and show a clear spatial hierarchy moving from public to private domains. Territorial markers such as fences distinguish property boundaries, offering a sense of enclosure and identity, while the landscape is shaped by agricultural activity and livestock farming. The presence of scenic views, variable fence heights, scattered apartment buildings, frequently located above commercial strips, and accessible educational institutions shape the daily rhythms and community life of elderly residents.

Theme 2—Town’s infrastructure (Economic Liquidity): Limited services exacerbate mobility barriers. Participant: ‘No paved roads mean I’m prisoner in my home’ (Female, 81, Mafraq). Focuses on town infrastructure. Many villages feature irregular street layouts and highly mixed housing typologies. Essential services, most notably mosques, health centers, and neighborhood parks, are present but not universally accessible; in some instances, basic utilities such as electricity or paved roads are lacking, directly impacting mobility for the elderly. Villages sometimes employ symbolic open gates reminiscent of gated communities, but they often lack entertainment facilities or playgrounds—especially for younger residents. The process of land donations for public services by local inhabitants exemplifies strong communal values but also exposes gaps in formal planning and provision.

Theme 3—Housing typologies (Symbolic Spaces): Traditional stone designs embody heritage but hinder accessibility. Participant: ‘Cross vaults honor our past, but these steps will kill me’ (Male, 79, Madaba). Examine the typology and heritage of housing, distinguishing older basalt and stone constructions from newer concrete-block homes. Traditional dwellings often incorporate cross vaults and food storage features such as kuwrar, and most include rainwater wells. While low, symbolic fences predominate, some villages are marked by the presence of apartments above active commercial ground floors that serve the local market.

Theme 4—Village social structures (Familial Authority): Kinship rituals preserve intergenerational bonds. Participant: ‘Friday coffee with elders is sacred—we solve family disputes there’ (Female, 68, Jerash). Addresses social structure at the village level, including strong kinship ties, the predominance of socializing and visiting traditions, and a collective memory of a more unified and socially sacred past. Although many villages have maintained periodic meetings among elders, and coffee gatherings and chess games remain common, growing village populations and youth migration outside Jordan have led to some community fragmentation and changing identities.

Theme 5—Household social structures (Economic Liquidity): Military/farming incomes sustain multigenerational homes. Participant: ‘My pension feeds 10 people—no money left for ramps’ (Male, 74, Zarqa). Probes social structure within the household, with the oldest residents reporting extended family living arrangements. While economic status is typically sustained through farming, livestock, or military employment, a small number of households have members with Bachelor’s degrees. Most homes are inherited and land-owned, creating tangible links to community heritage. Basic furniture and household goods fulfill practical needs, while health conditions remain stable for most participants.

Theme 6—Cultural values (Symbolic Spaces + Familial Authority): Birr al-wālidayn (filial piety) dictates home care. Participant: ‘Turning parents’ home into a hospital? That’s haram [forbidden]’ (Male, 70, Irbid). Reveals the core values and culture that define aging in place. Strong respect and care for elders, intergenerational bonding, communal habits of socializing and generosity, friendliness, religious devotion, and general self-sufficiency are notable. Elders often wield authority over family decisions and maintain control over domestic activities and social gatherings.

Theme 7—Perception of control (Familial Authority): Gendered autonomy declines with age. Participant: ‘At 85, my sons decide everything—even where I sleep’ (Female, 85, Salt). Elaborates on perceptions of control, highlighting varied levels of autonomy. Elders who possess private or assigned rooms report greater satisfaction and control, especially those living alone or in households with fewer family members. Male elders tend to have more control over household matters than their female counterparts. Participant interviews revealed that the sense of control diminishes with increasing age and declining health: those aged 60–70 reported substantial control, while between ages 70–80 this decreased, with full control experienced by only a minority. Three distinct forms of control were observed: comprehensive (physical and social), partial (mainly social or advisory), and negligible or absent.

Theme 8—Place attachment (Symbolic Spaces): Land embodies sumud (steadfastness). Participant: ‘This soil holds my children’s umbilical cords—I’ll die here’ (Female, 78, Balqa). Centers on attachment to place. Elders articulate deep-rooted attachment not only to their dwelling and village, but also to tangible objects such as handmade tools and to land used for agriculture. Qualitative distinctions emerged by gender, as women displayed greater emotional attachment overall. Personal attachments are further intensified by health status and income, shaping elders’ perceived autonomy and sense of belonging.

Theme 9—Modification practices (Economic Liquidity): Changes respond to family lifecycle needs. Participant: ‘We widened doors when my father got sick—but hid ramps behind walls’ (Male, 65, Madaba). Summarizes modification practices, with many households undertaking upgrades correlating with changes in family size and composition.

Theme 10—Group conflict (Familial Authority): Youth challenge tradition. Participant: ‘My grandson wants elevators... but this house is my soul’ (Female, 90, Ajloun). Points to group conflict, typically arising among the younger generation (ages 20–30), in topics ranging from caregiving to plans for home alterations.

Theme 11—Emotions (Symbolic Spaces + Economic Liquidity): Loneliness conflicts with pride. Participant: ‘Empty rooms echo, but selling would betray my ancestors’ (Widow, 82, Jerash). Sheds light on negative experiences such as loneliness, poverty, lack of care, and substandard housing—common scenarios include elders whose adult children are preoccupied or have emigrated, as well as dwellings with poorly isolated windows, non-weatherproof doors, and unsound walls. It also aligns with positive emotions, as many elderly interviewees described receiving emotional, social, and practical support from their communities, and invoking tradition as a reliable guarantee of elder well-being.

Themes substantiated through 35 participant voices validate the Cultural–Environmental Congruence Model. Quotes reveal tensions between Islamic ethics (birr al-wālidayn) and built environment constraints—e.g., heritage preservation vs. safety needs.

4.4. Synthesis of Combined Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

The synthesis of qualitative insights with quantitative results serves to deepen the analysis, revealing elder experiences. The combined evidence drawn from quantitative and qualitative data reveals the complex interplay between cultural values, economic constraints, gendered authority, and systemic policy gaps in shaping aging-in-place trajectories across Jordan. The imperative to reconcile Islamic and familial traditions with universal design principles is clear—without such alignment, the transformative potential of home modification for elder safety and dignity remains unrealized.

4.4.1. Cultural Priorities vs. Physical Barriers

A central finding of this research is the dominance of cultural priorities, such as the upholding of familial hospitality and Islamic values, over direct accessibility or safety concerns. Widowed elders, representing 32.9% of the sample (Table 13), most often prioritized the maintenance and aesthetic preservation of communal spaces—especially reception rooms (majlis)—over modifying these spaces for accessibility. Despite the low accessibility of these areas (M = 1.87, SD = 0.33), they exhibited the highest modification rate (M = 1.65, SD = 0.48), as evidenced by the significant association found in the chi-square tests (χ2 = 102.75, p < 0.001, Table 8).

Table 13.

Modification priorities by marital status.

Qualitative insights aligned closely with these quantitative results. Participants described the majlis as the heart of family honor, emphasizing that any adaptation should maintain its aesthetic integrity. As one widowed elder in Madaba explained, “We repainted the majlis for my son’s wedding but left the narrow doorway, guests shouldn’t think we’re infirm”. Furthermore, many elders, particularly widows, were resistant to installing safety features like bathroom grab bars, with 22% citing concerns that such changes would create a hospital-like atmosphere in their homes. This tension between tradition and safety mirrors findings from Lebanon, where elders likewise prioritize reception room upkeep over accessibility improvements [3], in sharp contrast to Sweden, where 89% of elders have modified bathrooms for safety [7].

4.4.2. Economic Constraints

While homeownership is high among older Jordanians at 87.6% (Table 2), this asset does not facilitate more frequent modifications due to significant financial barriers. Data indicate that 34% of low-income households (≤JD 400/month) reported not making any modifications, compared to only 8% among higher-income households (≥JD 800/month). Regression analysis shows that homeownership is a non-significant predictor of modifications (β = 0.02, p = 0.61), with income exerting an indirect effect potentially mediated by family size (β = −0.053, p = 0.20).

Interview themes supported these statistical findings, revealing that families prioritized urgent repairs, such as fixing leaking roofs, over preventative or safety-related modifications. One participant from Zarqa noted, “I saved for two years to fix the kitchen ceiling—ramps can wait.” Importantly, 61% of modifications were financed through remittances from relatives abroad, showcasing how migration and external financial support play a vital role in adaptation strategies for many Jordanian households [11].

A cross-national perspective highlights the magnitude of these challenges. In Turkey, 45% of elderly residents accessed government grants for home adaptations [29], while similar subsidy schemes are nearly absent in Jordan. This lack of support creates additional difficulties, particularly for those earning minimum wage, as the median modification cost of $1500 [44] can represent more than six months of income.

Our analysis further indicates that income levels significantly impact families’ ability to undertake renovations. Among low-income participants, 61% reported being unable to afford even basic modifications necessary for safe aging in place, such as the installation of grab bars and ramps. In contrast, families with higher incomes exhibited a greater capacity to finance renovations, with only 8% reporting similar constraints. Additionally, the unpredictable financial landscape, characterized by high renovation costs, causes many families to delay necessary adaptations. This situation aligns with findings from Lebanon, where governmental support effectively reduces barriers, highlighting the need for similar subsidy programs in Jordan to address these economic challenges.

4.4.3. Gender Dynamics

Another key finding centers on gendered patterns in decision-making and control over modifications (Table 14). Quantitative analysis revealed that males (53% of the sample) were significantly more likely to initiate or lead modification projects (β = 0.27, p < 0.001, Table 11). Males reported assigned private rooms at a rate of 78.5%, compared to only 62% for females (see Table 1), further underscoring gender-based hierarchies within households. Calculated odds ratios indicate that men are 1.8 times more likely to be the primary actors in home modifications (OR = 1.82, 95% CI: 1.3–2.5).

Table 14.

Gender differences in modification types.

Qualitative findings once again bolster these conclusions. Male participants often equated modification control with provider roles, as illustrated by one elder from Irbid who stated, “As the eldest son, I decide where to spend, my mother’s bathroom isn’t my priority”. Conversely, female elders, while appreciative of improvements such as window repairs, frequently deferred decision-making authority to male relatives. This patriarchal pattern diverges from regional examples such as Lebanon, where women in matrilocal households direct 67% of home modifications [3,28,60].

Financial Barriers to Renovation: The interviews revealed pronounced gendered dynamics in decision-making surrounding home modifications. A significant portion of female participants expressed feelings of exclusion from decision-making processes, citing, “I have to wait for my son to decide if we can put in safety bars in the bathroom. It is not my place to ask for changes” (Participant 12, Madaba). This statement exemplifies the broader cultural tendency, where the responsibility for elder care—and thus the agency in deciding upon modifications—often falls to male family members. This dynamic complicates necessary adaptations, as cultural stigma surrounding modifications is frequently cited among older women, reflecting findings from [3,48] on how home modifications may be seen as indicators of frailty or dependency.

4.4.4. Policy Disconnects

The final major theme highlights the persistent misalignment between policy priorities and the lived realities of elderly Jordanians. There remain no national building standards for age-friendly residential design, which exacerbates regional and socio-economic disparities in accessibility and adaptation rates. For example, in Balqa governorate, where 25.6% of the sample resides, modification rates reached 65% (Table 15), in contrast to Mafraq (22%), a region marked by lower GDP (see Table 2).

Table 15.

Governorate comparison.

Accessibility scores also reflect stark urban–rural divides, with rural governorates such as Ajloun and Jerash lagging 23% behind urban centers like Irbid or Amman. Qualitative accounts further reveal that 67% of rural elders cited unpaved streets as a major obstacle to basic mobility, with one participant from Ajloun explaining, “My wheelchair sinks in mud, I haven’t left home in three years”. Despite the advocacy of local elderly councils for regulatory change, participants reported limited governmental engagement.

Lessons from comparative policy models are instructive. The European Union has enacted mandatory standards, such as requiring bathroom grab bars in all social housing [7], while Japan subsidizes up to 90% of modification costs through a nationwide program [52,61]. The process of the necessary steps for Jordan to implement similar reforms includes barrier identification, stakeholder engagement, code drafting, pilot implementation, and eventual national roll-out.

Regression findings contextualize stark governorate disparities in Table 15. Balqa’s high modification rate (65%) correlates strongly with urban advantages: higher average income (JD 610), stronger NGO presence, and enforcement of municipal codes. Conversely, Mafraq’s low rate (22%) reflects intersecting vulnerabilities—poverty (mean income: JD 280), rural isolation, and policy neglect (“My wheelchair sinks in mud; I haven’t left home in years”). These patterns validate the Cultural–Environmental Congruence Model: economic liquidity (β = −0.05 for low-income status) and spatial hierarchies (male authority β = 0.27) collectively determine modification feasibility. Policy interventions must therefore target place-specific barriers, not merely ownership rates.

In summary, the combined evidence drawn from quantitative and qualitative data reveals the complex interplay between cultural values, economic constraints, gendered authority, and systemic policy gaps in shaping aging-in-place trajectories across Jordan. The imperative to reconcile Islamic and familial traditions with universal design principles is clear; without such alignment, the transformative potential of home modification for elder safety and dignity remains unrealized.

5. Discussion

This study reveals profound tensions between Jordan’s cultural ideals of familial elder care and the realities imposed by housing infrastructure ill-equipped for aging populations. By synthesizing an array of quantitative findings, qualitative insights, and comparative international frameworks, this discussion positions Jordan’s aging-in-place landscape within both MENA-specific policy gaps [2] and global aging trends [62]. The following discussion is structured around four interrelated themes: cultural conflicts between care expectations and physical safety, persistent universal design gaps, gender inequities regarding authority and attachment, and policy pathways for reform.

This study underscores the critical importance of understanding cultural values and gender dynamics in shaping the experiences of aging in place for elderly Jordanians. As highlighted in the findings, the intersection of familial expectations and gendered roles plays a significant role in determining whether essential home modifications are pursued or postponed. Policymakers must take these cultural factors into account to create more inclusive and supportive strategies that empower elderly individuals, particularly women, to advocate for necessary changes in their home environments.

Three dialectics emerge from our findings: cultural ideals versus safety realities (5.1), universal design potential versus implementation gaps (5.2), and policy inertia versus community-based solutions (5.3). We examine these through Jordan’s Islamic care ethics and comparative global models.

5.1. The Cultural and Economic Landscape of Aging in Jordan: Balancing Family Duty and Safety

This research highlights a significant divergence between Islamic ethical imperatives, such as birr al-wālidayn (filial piety), and the hazards that elderly individuals face within their living environments. Although strong cultural and religious values drive expectations for families to care for elders, a notable percentage of households lack basic safety features, including bathroom grab bars. This systemic tension reflects a broader pattern in the MENA region, where a substantial number of elders live in hazardous conditions [2]. Vulnerable demographic groups, particularly widowed elders, show low rates of safety modifications, such as a mere 6% implementation for bathroom safety features [63].

Qualitative insights indicate that participants prioritize preserving traditional reception rooms (majlis) for family gatherings over safety upgrades. Concerns arise that modifications could “medicalize” their homes or diminish the sacredness of these communal spaces (Theme 6). Cultural resistance to modifications is not exclusive to Jordan; similar issues have been noted in neighboring countries like Egypt, which faced significant delays in implementing national accessibility codes until 2021 [62]. In contrast, Japan’s Community-Based Integrated Care System reframed home modifications as enhancements of dignity, associated with a 41% reduction in fall-related hospitalizations [64,65]. These international examples highlight the need to reframe home adaptations in Jordan to align with cultural values. Increased awareness campaigns leveraging faith leaders could help rebrand safety features like grab bars as essential to hifz al-karāma (preservation of dignity). Additionally, architectural designs should incorporate culturally sensitive modifications such as discreet ramps in courtyards or behind existing structures to maintain the aesthetic integrity of homes [29].

The analysis reveals a concerning 34% affordability gap for necessary home modifications among low-income households, underscoring barriers related to both economic resources and cultural resistance to change. Many participants expressed reluctance to modify their homes, fearing they would appear “hospital-like.” One expressed concern that “guests shouldn’t think we’re infirm,” emphasizing how cultural perceptions about pride can inhibit essential safety adaptations. Moreover, the intersection of gender dynamics with home modification decisions reflects ingrained patriarchal norms. Men often control these decisions, despite qualitative data indicating that women have deeper emotional and symbolic attachments to their homes (Theme 8). Men also report higher rates of having private rooms compared to women, illustrating the prevailing patriarchal structure (78.5% of men versus 62% of women). Women frequently defer decisions regarding modifications to male relatives, even when they are disproportionately affected by safety issues in kitchens or bathrooms (Theme 7).

In contrast, matrilocal societies, such as some areas in Lebanon, show that when women control property, they prioritize accessibility and safety, directing a significant percentage of home modifications [3,66]. To address these gender disparities, it is crucial to empower women as housing ambassadors within their communities. Providing training and resources for advocacy related to household safety can help shift the narrative and redefine decision-making structures. Additionally, legal reforms to inheritance laws that ensure equitable property rights for daughters and wives would enhance their agency regarding modifications and adaptations.

The study also identifies substantial gaps in the application of universal design principles within Jordanian homes. Despite a high homeownership prevalence among elders (87.6%), low-income households struggle to afford necessary modifications, significantly contrasting the situation in South Korea, where a large percentage of elders have access to subsidized modifications [51]. Economic analysis supports that income, influenced by family size, serves as a critical barrier to adaptation efforts, and liquidity constraints hinder even those with robust housing assets (Table 10).

Geographical disparities exacerbate these challenges, with rural regions like Ajloun and Mafraq reporting accessibility scores significantly lower than urban governorates (23% lower), worsening inequity (Table 13). Comparisons with other studies suggest alternative funding approaches, such as municipal-level grants in Turkey that cover up to half the costs for modifying historic homes [29] and the [67] Directive mandating basic accessibility features in social housing [7]. Jordan could establish similar funds for low-cost modifications, including non-slip flooring and grab bars, and consider integrating heritage-sensitive design practices, such as concealed railings.

Overall, this study underscores the stark contrast between low-income families in Jordan and those in other Middle Eastern countries regarding financial assistance for home renovations. Unlike Lebanon, which has initiatives to subsidize home modifications [3], many Jordanian low-income families face financial crises that hinder their ability to create elder-friendly living environments. The absence of targeted subsidy programs in Jordan suggests that innovative financing solutions, adapted from successful models in neighboring countries, could be crucial in addressing the growing disparity in housing adequacy for the aging population.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions: Universal Design Potential Versus Implementation Gaps

This study makes a significant advancement in the field of environmental gerontology by demonstrating how collectivist cultural norms within the Arab world critically influence the relationship between individuals and their living environments. In contrast to the Western emphasis on independence as the primary objective of aging in place, the Jordanian context reveals a prevailing theme of interdependence. Here, notions of safety, comfort, and autonomy are intricately negotiated within family networks. The proposed Cultural–Environmental Congruence Model effectively encapsulates these dynamics, highlighting how Islamic values shape familial care norms. These norms, in turn, guide the prioritization of home modifications and impact safety outcomes for elderly residents. This model advocates for a collectivist approach to universal design that is both adaptive and rooted in local cultural contexts, thereby challenging the dominant individualistic perspectives commonly represented in existing literature.

By contrasting the tenets of environmental gerontology with those of universal design and Islamic collectivism, this study provides a nuanced theoretical framework that articulates the complex interplay between cultural influences and environmental adaptation. It underscores the importance of recognizing how deeply held cultural values inform and shape practical decisions regarding home modifications, ultimately enhancing the understanding of aging in place within collectivist societies. Incorporating the Cultural–Environmental Congruence Model offers a richer perspective on how collectivist cultural contexts can shape more responsive and locally relevant applications of universal design principles. This not only contributes to theoretical discourse but also posits a pathway for designing environments that better serve the needs of aging populations in culturally diverse contexts.

5.3. Policy Pathways: From Inertia to Integration

This research highlights a significant structural challenge in Jordan regarding the lack of enforceable national design standards for elder-friendly housing, an issue pervasive in many MENA countries [2]. Ref. [68] has not effectively addressed these challenges, leading to ongoing inequalities and exclusionary architectural practices. This policy gap is illustrated by the stark variation in modification rates between regions; for example, Balqa has a modification rate of 65% due to proactive NGO engagement, while Mafraq languishes at only 22%, despite similar demographic needs (Table 13). Efforts by elderly councils to advocate for necessary reforms are often thwarted by bureaucratic inertia.

International examples offer valuable insights into potential low-cost interventions that could provide solutions for Jordan. For instance, NGO-led initiatives in Australia have successfully reduced hospitalizations by one-third through the strategic implementation of ramps [69]. Similarly, Chile’s National Elderly Housing Code mandates step-free entries enforced via municipal permits, leading to improved nationwide accessibility standards [62]. Jordan stands to benefit significantly from partnerships with local NGOs, such as Tkiyet Um Ali, to implement pilot projects focused on retrofitting homes and community centers, including mosques. Strengthening the regulatory framework by linking planning and construction permits to mandatory accessibility audits is crucial and should include requirements that new homes feature at least one step-free entrance.

Lessons from the Netherlands reinforce the need for sustained public awareness campaigns to combat stigma surrounding home modifications, an approach that Jordan could replicate. Additionally, addressing gender disparities is vital; empowering women as housing ambassadors within their communities can enhance advocacy for safety measures. Legal reforms to inheritance laws are necessary to ensure equitable property rights for daughters and wives, granting them greater agency in decisions regarding home modifications. It is essential to consider the involvement of religious councils to legitimize and promote modifications as dignity-preserving choices.