Abstract

This research explores the concept of open building (OB) in the context of low-cost housing, focusing on its historical applications in Egypt during the 1980s. By evaluating past experiences, the study aims to extract key lessons that can inform the design and implementation of contemporary social housing projects. The goal is to foster resilience and diversity in housing typologies to ensure they align with the evolving needs of residents. To achieve these objectives, the research employed a multi-dimensional strategy, beginning with a comprehensive literature review of the open building movement (OB); then, the study traced the evolution of the OB movement in Egypt using a qualitative analysis approach, which involved analyzing its implementation in low-cost housing projects over the past four decades. Through this historical lens, the study identifies design principles and strategies that can enhance social housing projects by applying OB. Considering the life cycle cost, OB enables an incremental process that would align with users’ financial capacities. The research revealed the substantial capacity of open building (OB) to address Egypt’s social housing challenges, primarily by fostering user-driven flexibility in housing unit design and area selection. This empowers occupants to choose spaces perfectly suited to their family’s evolving needs. Moreover, the findings provide a roadmap for revitalizing the OB movement by analyzing and overcoming past implementation difficulties, consequently balancing the initial cost and long-term economics for citizens and significantly reducing the governmental sector’s expenditure.

1. Introduction

The open building (OB) movement, which emphasizes flexibility, adaptability, and user participation in housing design, has gained global recognition as a sustainable approach to urban development. It was started in 1961 by John Habraken [], where “Supports are part of the public domain and are permanent, while the infill belongs to the individual and is changeable. Participation and freedom of choice for the user is the key objective” [].

Habraken [] first introduced the concept of open building in his 1961 publication, “De Dragersen de Mensen”. He initially focused on the relationship between the support structure and the infill within the industrial production process. In his later works, he expanded the concept, emphasizing the integration of the support structure into the everyday built environment and prioritizing user needs over structural and design considerations []. Open buildings focus on flexibility, adaptability, circularity, and improved resilience. Their unique architecture helps them to enhance urban vibrancy, while co-creation with future users fosters inclusivity and a strong sense of community [].

The open building approach has been implemented across various scales, ranging from urban and campus designs to the development of different architectural prototypes, such as office, retail, and educational buildings in the Shenzhen University Engineering School, and the health care building in the INO Intensive Care Facility []. This approach can be used for the adaptive reuse of different prototypes [,]. Open building is considered a sustainable approach in residential design, such as in high-rise buildings [,] and in different residential prototypes [,].

From a global perspective, significant residential projects, such as the Byker Wall in Newcastle upon Tyne (1969–1982) by Ralph Erskine and the Quinta Monroy Housing project in Iquique, Chile (2004, Aga Khan Award 2016), by Alejandro Aravena, are important examples of open buildings (OBs). By incorporating resident feedback through its on-site office, Erskine’s Byker Wall features OB’s participatory practice. Its adaptable design complied with OB’s flexibility principles by enabling residents to personalize their unit’s master plan []. Quinta Monroy in Aravena also offered partially built residential units, enabling residents to incrementally build their own units gradually, increasing their affordability and adaptability [].

The aforementioned projects exemplify OB’s core principles (user participation, modularity, and life cycle adaptability) and provide important insights for Egypt’s affordable housing market. They also showcase global OB applications that highlight various resident-driven, sustainable housing solutions.

Open building is an internationally recognized approach, where recent global research trends emphasize its evolving role in addressing sustainability and adaptability in urban housing, extending beyond Egypt’s context. Global case studies were discussed by (Kendall, 2023) [] in his book “Open Building for Architects”. It emphasizes an OB approach to steward the planet’s resources and contribute to the global economy in a manner that benefits all people. On the other hand, in his book “ZEMCH: Toward the Delivery of Zero Energy Mass Custom Homes”, (Noguchi, 2016) [] explored the OB concepts of mass customization, mass personalization, and inclusive design. The Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction, 2022 [], emphasizes the importance of applying OB principles to high-density urban areas to fulfill national targets for decarbonization and resilient building practices through modular housing projects that decrease waste. In summary, the international research shows how OB can fulfill user requirements while supporting Egypt’s objective of making housing more affordable.

In Egypt, there was a successful experience with open residential housing in 1987, known as the “Low-Cost Housing Project”. This initiative provided affordable housing options for low-income families []. However, this approach has since been largely neglected in subsequent Egyptian housing strategies.

This research aims to address this research gap by reviving the concept of open building by examining the strengths of the past implementation while looking toward future applications. Specifically, this research explores how open building principles can be successfully applied to social housing projects now, which is currently considered the primary public project for low-income populations in Egypt.

1.1. Open Building Movement

Open building (OB) principles are adopted by professionals across various environmental contexts and in diverse practice settings worldwide. This has led to the emergence of a wide range of concepts, products, methods, and best practices, as OB is implemented with varying participants, approaches, and desired outcomes. It can be applied at the urban design or architectural scales. It started with a focus on mass housing projects; since then, it has developed broader applications than housing.

Key Open Building Concepts

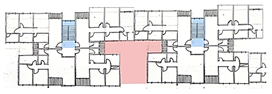

- Levels: Due to nearly four decades of rigorous investigation, a substantial corpus of knowledge has been generated, encompassing both theoretical and applied research pertaining to the environmental and decision-making levels (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The five-level model of physical systems related to a territorial hierarchy. Source: authors.

Figure 1. The five-level model of physical systems related to a territorial hierarchy. Source: authors. - Support: Support is not the structure, but it is a finished building, ready to be occupied by variable infill. It is also the permanent, shared zones of a building that supply serviced space for users. Support elements typically include structural components, such as the building’s frame and facade, as well as essential infrastructure, such as entrances; staircases; elevators; and main lines for various utilities, including electricity, communications, water, gas, and drainage [].

- Infill: In an open building, infill refers to the interior components or customizable elements of a building that are designed to be adaptable, flexible, and independent from the building’s permanent structural framework, known as the base building or support structure. In open building, many of the technical and organizational challenges associated with building elements are transferred to the less complex infill level, resulting in significant benefits [].

- Unbundling decision-making: In open building, unbundling decision-making refers to the method of separating and distributing decision-making power and roles among different stakeholders, such as the government or users, throughout the building’s life cycle.

- Capacity: Capacity analysis, a fundamental aspect of open building, rests on two key principles: first, designing structures with inherent flexibility and adaptability; second, creating spaces at various scales, capable of accommodating multiple functions over time [].

- Sustainability: Sustainability can be defined as the construction, operation, and maintenance of structures in a way that meets the needs of the present without compromising future generations. Open building aligns with sustainability principles by promoting the development of standardized interfaces, enabling builders and end users to easily integrate products from various manufacturers. A further alignment between open building and sustainability concerns the development of standardized technical interfaces, which allows the builder or end user greater flexibility for “plug-and-play” regarding product selection and encourages the use of components from different manufacturers, fostering a more sustainable and competitive market. Moreover, open building (OB) aligns with sustainability in terms of separating the support elements and infill and allows buildings to evolve over time without major demolition or reconstruction, reducing material waste. OB allows users to complete their units based on their financial capacity, which enables a reduction in the initial construction costs for governments.

1.2. Open Residential Building Concept

Residential open building is a flexible, multi-disciplinary approach that reimagines the entire life cycle of residential development, encompassing the design; financing; construction; fit-out; and long-term management, including mixed-use projects [,].

One of the defining characteristics of residential open building is the active engagement of residents, individually and collectively, in the design procedure. The development of innovative technologies within the realms of design, logistics, and production has considerably enhanced the potential for customized building elements. While the architect maintains a pivotal role in establishing the overall design framework, this approach fosters a more participatory decision-making process, empowering residents to have a greater influence on the built environment [].

OB Objectives

There are many objectives for the open building movement, where participation and freedom of choice for the user are the key objectives. The OB objectives can be classified as the following:

- Economic objectives and sustainability: Open building transforms the way control and costs are allocated among stakeholders, often unlocking opportunities for innovation in project financing and long-term asset management strategies, while enabling more precise methods for evaluating projects [].Moreover, OB helps with supplying affordable housing since it enables users to complete the dwelling incrementally, in alignment with their financial capacity and means. It also helps with increasing the affordability of the housing unit by decreasing the cost of internal walls and finishing that could be changed due to user adaptation and needs.Open building also helps to bridge the gap between supply and demand in the housing market. By enabling the supply of diverse housing units with varying sizes and price points, it caters to a broader range of user needs.

- Social objectives: The significance of user participation in community development processes, including housing projects, has long been acknowledged. Its effective implementation can contribute to a range of objectives, encompassing socio-cultural, political, and economic dimensions. Habraken [,] underscored the significance of user participation in achieving dwelling flexibility and adaptability. This approach facilitates the accommodation of diverse and evolving resident needs [,]. The open building method enables diverse resident needs through user-friendly systems that non-experts can modify to customize their spaces, thus democratizing design. The design process and construction and finishing of partially completed housing projects allow users to participate, leading to higher engagement and adaptability.Design approach: This enables buildings to evolve over time by separating the base structure (support) from interior systems (infill), allowing unrelated renovation without major interferences []. By applying more flexible features and supplying more than one design for the dwelling with different areas and different properties, this makes housing adaptable with family life cycle changes [].

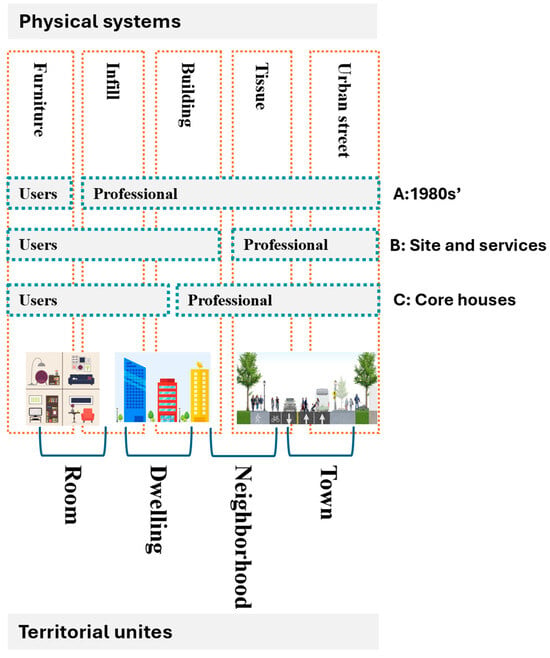

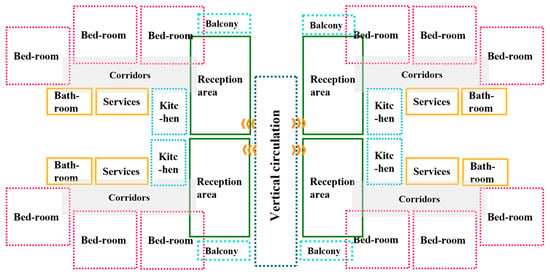

1.3. Capacity Analysis: Zone and Margin Analysis

When designing a building, architects often face the challenge of creating a structure that can be used in many ways. Zones are designated areas within the built environment possessing specific architectural significance yet characterized by general spatial qualities. The zone concept is applicable across all scales, where zone type definitions vary according to the specific level of the built environment under consideration. In housing design, a zone area could be a reception area; bedroom; or even a service, such as a kitchen or bathroom. Meanwhile, a margin refers to a specific area of overlap belonging to two spatial planning zones, such as corridors or a balcony (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Zone and margin grid. Source: authors.

Space capacity links a given form to a function. It is important to recognize that the concept of zone and margin distribution can be applied to characterize other housing types, such as double-loaded corridor buildings and deep/shallow prototypes []. A sector is characterized by a particular length that includes multiple zones with their adjacent margins []. In a base building, the space between structural elements, like load-bearing walls or columns, can be defined as a sector, and it is always related to the span of a structural system.

The way zones are distributed can vary widely depending on the cultural and geographical contexts. This flexibility allows for design solutions such as creating functional spaces within dwellings that may not have direct access to natural light or ventilation [].

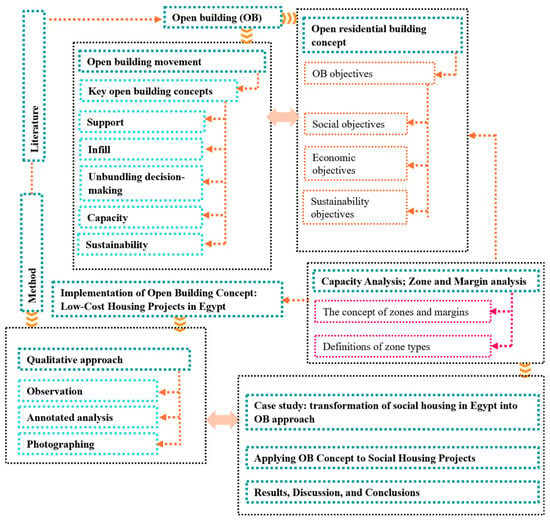

2. Materials and Methods

This study utilizes a mixed-methods case study approach with a focus on qualitative analysis [] to investigate the open building concept within low-cost housing projects in Egypt. First, this research employs archival data analysis by drawing upon a comprehensive range of governmental reports, published academic papers and books, and reports from international organizations pertaining to Egypt’s housing sector and urban development. Then, the research documents existing physical conditions by utilizing tools such as observations, maps, and photography. The archival documentation also involves formal references, where our primary data sources include official Ministry of Development and Housing archives, such as project briefs and construction drawings (Figure 3). This research adopts a qualitative method to assess how the open building (OB) movement affects the low-income housing market in Egypt. The research data collection included the Egyptian Social Housing Program’s archival records alongside a case study-based analysis, which revealed user participation and adaptability themes that support the development of scalable housing policies. The research methodology provides a strong assessment of OB’s suitability for Egypt through metrics that help stakeholders achieve optimal affordability and sustainability.

Figure 3.

Research methodology. Source: authors.

2.1. Case Study Selection

Our research centers on the Egyptian context, which was strategically chosen due to Egypt’s role as a critical housing market, particularly concerning low-income housing developments. The country is notably positioned as a leading innovator in accessible housing solutions within the developing world.

2.2. Implementation of Open Building Concept: Low-Cost Housing Projects in Egypt

In 1987, the Ministry of Development and Housing started to apply the concept of low-cost housing for low-income groups, which was assumed to be a key factor in reducing the initial cost of the dwellings and increasing the role of user participation in the accommodation of their different needs. These initiatives were implemented on a significant scale, resulting in the construction and delivery of several hundred thousand partially completed housing units across Egypt [].

This research investigates open building (OB) in Egyptian low-cost housing to determine its ability to improve existing social housing policies. OB promotes adaptable and user-participatory design approaches that enable residents to customize their own units according to their diverse needs and financial capacities. Open building (OB), which was used to focus on adaptability and user participation in Egyptian low-income housing, demonstrates great potential for addressing sustainability and affordability through a life cycle cost approach. Open building designs offer flexible layouts that reduce material use while optimizing energy consumption by using durable materials that reduce maintenance expenses throughout the building’s lifetime. Open building enables affordable housing solutions through material selection that matches long-term cost allocation plans to achieve construction affordability and operational and environmental sustainability. This comprehensive approach enhances open building’s role in sustainable urban development in Egypt by combining economic feasibility with reduced energy usage and better living standards.

The 1987, OB housing projects provided partially finished units (45–90 m2). Post-1987, Egypt’s housing policies shifted away from Open Building principles to construct standardized fully finished units, which became the standard in the Social Housing Program through its 90 m2 uniform apartments [,]. The transition occurred because of multiple factors, including government policy changes toward simple scalable construction models and institutional limitations in handling participatory approaches. The economic pressures and challenges of Egypt’s socio-cultural context were the main cause behind these major shifts [,]. This study addressed this policy gap through proposed OB-based approaches, which aim to restore flexible and cost-efficient housing solutions and seek to improve Egypt’s social housing through the reintroduction of open building principles, which will achieve affordability alongside resilience and alignment with diverse user needs.

The objectives of this housing prototype comprise two main goals. The first is an economic goal, which is achieved by reducing the cost of constructing interior walls and finishes for the government. The second is a social goal, which is achieved by encouraging user participation in the housing development process. This is achieved by allowing residents to choose interior designs according to their needs and build partitions and interior finishes themselves.

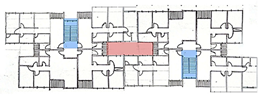

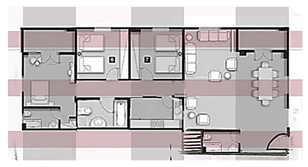

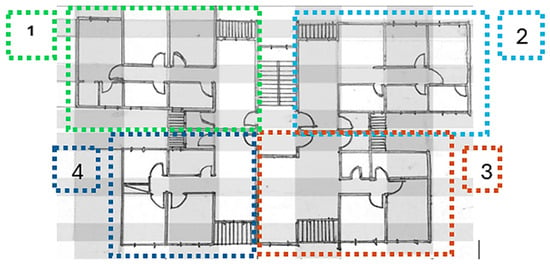

Figure 4 shows the project offering partially completed housing with different areas: 45, 60, 75, and 90 m2, with different building types: deep prototypes, such as A, B, C, and G (4 dwellings per floor), and shallow units, such as prototypes E and F (2 dwellings per floor) [].

Figure 4.

Plans for Low-cost housing project for low-income group. Source: authors.

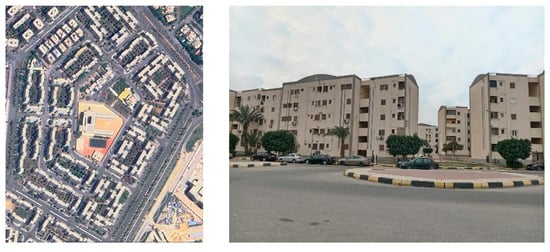

The Ministry of Development and New Communities, along with associated entities, such as the Housing and Development Bank and the Sheik Zayed New City Development Office, revised the Master Plan for the entire settlement following a shift in the allocation policy. This change prioritized housing provision for middle- and higher-income groups. Entire neighborhoods were allocated to private developers for the construction of gated communities and upscale resorts. To enhance the appeal of these new developments, the facades of partially completed apartment buildings were renovated, and landscaping improvements were made to the surrounding spaces [] (Figure 5). These upgraded and more costly projects began to attract residents with higher incomes and social status compared with the originally intended socio-economic groups.

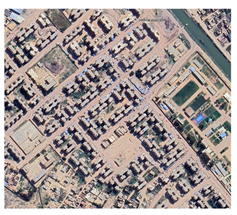

Figure 5.

Low-cost project in EL Sheikh Zayed city, 1st district. Sources: Google Earth and the authors December 2024.

According to a city case study on 6 October [], a significant number of residents undertook interior design modifications, which were primarily focused on maximizing the living space through structural adjustments, such as integrating balconies into bedroom areas or incorporating laundry drying spaces (small terraces) into kitchen and bathroom layouts. Furthermore, residents preferred to own the unfinished housing unit. Depending on the area, residents reported that 45 m2 was insufficient for the average family.

Table 1 illustrates the different examples of low-cost housing projects in different new cities in Egypt using the same prototype.

Table 1.

Examples of low-cost housing projects in Egypt. Source: Google Earth 2025.

2.3. Case Study: Transformation of Social Housing in Egypt into OB

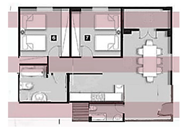

The Social Housing Program (SHP) has been the low-income public housing project in Egypt since 2013. It offers one 90 m2 housing prototype with three bedrooms, a kitchen, and a bathroom []. It is also named the Million-Housing Project, as it aims to supply 1 million fully finished apartment for low-income families, distributed in all new cities in Egypt [,]. Figure 6 shows the ground floor plan and project examples.

Figure 6.

Social housing project. Source: authors.

Housing units offered by the Ministry of Housing, including the Social Housing Program and previous initiatives, often fall short of meeting the needs of low-income populations. These units are frequently unaffordable, inadequate in terms of quality and suitability, and insufficient in number to address the significant demand []. This is why the research aims to apply the open building approach to enhance the social housing design and increase the flexibility by offering different prototypes with different areas, and help to decrease the construction cost, which could help with enhancing the affordability.

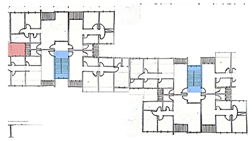

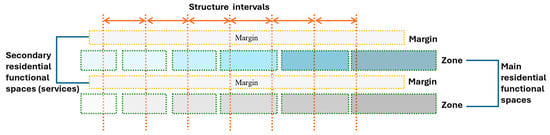

This section explains the goal of applying OB to social housing projects to create more affordable and flexible units. It explains the grid of zone and margin analysis based on the Egyptian housing codes, where for each alternative plan (A1, A2, A3, A4), it lists a detailed breakdown of the sector numbers, bedrooms, bathrooms, and kitchen, in addition to the total area. The proposed alternatives show how the structural system uses “sectors”, “zones”, and “margins” to distinguish the permanent “support” from the flexible “infill”, which enables future flexible additions while demonstrating the adaptability of OB through diverse interior arrangements to fulfil diverse users’ needs. The proposed alternatives enable user choices when customizing internal layouts, which supports the fundamental OB goal of resident participation during housing development.

2.4. Applying OB Concept to Social Housing Projects

The aim of applying OB to social housing projects is to offer several different housing units with different areas that can be more affordable and flexible with user needs after learning from the past.

By applying a zone and margin analysis, according to the Egyptian housing code for designing house and residential areas [], the minimum dimension for a bedroom was found to be 2.7 m and 1 m for a toilet, but for living, the minimum area is 10 m2 and kitchen 3 m2. The zones could be 2.4, 3.0, or 3.6 m; the margins could be 0.8, 1.0, or 1.2 m; and the sectors related to the structure system could be 3.6 m for bedrooms or 3.6, 4.0, or 5.2 m for a reception area.

The open building framework for Egypt’s social housing presents four dwelling typologies that measure 57.6, 79.2, 100.6, and 122.4 m2, expanding on the 1987 Low-Cost Housing Project’s original typologies (45, 60, 75, and 90 m2). The modifications to unit sizes demonstrate an effort to align with the changing needs of low-income residents through OB principles, which emphasize flexibility and user participation. The dimensions resulted from the zone and margin analysis, which used 3 m sectors, 2.4 m zones, and 1.2 m margins to create modular layouts that adjust to family life cycle changes. The increase in size matches the current demand, which notes that low-income families often require larger living spaces due to average household sizes of 4.5–5 persons according to the UN-Habitat Egypt Housing Profile (2016) [].

Table 2 illustrates various housing unit configurations, offering floor areas from 57.6 to 122.4 m2. This allows occupants to select a unit that aligns with their specific requirements and family life cycle. The design adheres to a 3-m sector grid, a 2.40-m zone, and a 1.2-m margin. Each sector’s total area, ranging from 21.6 to 28.8 m2, is further detailed in Figure 7 and Table 2.

Table 2.

Different alternatives for housing units with different areas by applying OB.

Figure 7.

Proposed design for social housing (each number presents a design alternative). Source: authors.

Furthermore, the alternatives present a range of attachments options that can be used in the layout to be more efficient in site planning.

2.5. Actors in the Development Process

The three main phases of housing development (conceptual design, implementation, and maintenance/management) are described in Table 3. It identifies two main actor groups: users (residents) and professionals (such as architects; engineers; and government organizations, such as the New Urban Communities Authority). Their roles in each stage under the current (actual) and intended (OB-based) conditions are explained below.

Table 3.

Stages of social housing development and actors, actual and proposed. Source: authors.

2.5.1. Conceptual Design Stage

- Current situation: The conceptual design stage is dominated by experts in Egypt’s social housing projects. Standardized home prototypes are created by contracted architects and engineers and government organizations with little input from users. The cost-effectiveness and speed of delivery are given priority in this top-down method, which frequently leads to homogeneous designs that do not consider the residents’ diverse needs.

- Proposed OB condition: OB presents a framework for active user participation in the design process. Within predetermined “support” structures, residents work with experts to personalize the house layouts (e.g., choosing from alternative plans A1–A4). Professionals become facilitators, offering technical advice and adaptable design choices, rather than being the sole decision-maker. This development is consistent with OB’s focus on user participation and involvement.

2.5.2. Implementation Stage

- Current situation: The construction process is managed by experts, including contractors and governmental organizations. Users receive fully finished units with minimal post-occupancy adjustments, and they play no part in the implementation. This method limits the flexibility and raises the internal finishing costs.

- Proposed OB condition: OB redefines implementation by differentiating between the “support” (basic structure) and “infill” (interior systems). While users help complete the infill (such as internal walls and finishes), professionals build the support. This enables users to customize the spaces to their needs and budgets while reducing government expenses on finishes. As their financial capacity increases, residences can choose to start with smaller units (such as A1, which is 57.6 m2) and upgrade to larger ones (such as A4, which is 122.4 m2).

2.5.3. Maintenance and Management Stage

- Current situation: Users usually have limited impact within the maintenance stage, which is mainly managed by governmental agencies or private entities. This causes inefficiencies, where users’ evolving needs are not effectively addressed.

- Proposed OB condition: OB encourages sustained user participation in maintenance. By creating flexible infill systems, residents can make changes to their units without significant structural changes. Professionals offer continuing technical assistance, guaranteeing that adjustments adhere to safety regulations.

A shift in responsibilities is how the transition takes place. Professionals move from prescriptive to enabling roles, offering frameworks that guide user modifications (such as a zone and margin analysis). Residents then actively participate in design choices and implementation duties.

3. Discussion

This research thoroughly investigated the open building (OB) movement’s potential revival as a strategic response to the escalating disparity between housing costs and residents’ incomes in developing nations, with a particular focus on Egypt’s low-income social housing sector. By rigorously analyzing past global successes and proposing context-specific, adaptable design strategies tailored for low-cost housing projects in Egypt, this study clearly demonstrated how OB principles can significantly enhance Egypt’s housing landscape. A key finding is the proposed renovation framework, which introduces four distinct dwelling typologies. These typologies prioritize inherent flexibility, fundamentally empowering residents to adapt their living space layouts over time in alignment with their shifting familial structures and evolving economic capabilities. This approach shifts housing from a static product to a dynamic system that can grow and change with its occupants.

The hierarchical framework of built environments facilitates the identification of immutable structural elements and temporally adaptable systems. At the “Building” tier, foundational components integral to the structural system are categorized as “Supports,” representing permanent features resistant to modification. Conversely, the “Infill” tier encompasses mutable physical systems designed for periodic adaptation, such as non-load-bearing partitions and modular service-oriented fixtures (e.g., kitchens and bathrooms), as well as upgradable utility networks, including electrical wiring; HVAC systems; and plumbing infrastructure for water, gas, and drainage.

This research contributes to the literature by highlighting the OB movement’s potential to address systemic challenges in Egypt’s housing sector. By decentralizing the design control and empowering residents to modify their spaces or select between more than one prototype with a constant area and design, OB strategies align with global discourses on participatory design and circularity.

The paper discusses the implementation obstacles of OB optimization strategies in Egypt’s Social Housing Program and their impacts on stakeholder dynamics, including a comprehensive discussion about the identified limitations. Implementing OB principles in Egypt’s social housing context faces several challenges. The main obstacles are institutional and regulatory barriers. The current housing policies in Egypt follow standardized top-down approaches, which prioritize rapid delivery instead of flexibility, following the strategies managed by governmental entities. The participatory and modular framework of OB needs substantial regulatory changes to enable flexible designs and user-driven modifications; proposing potential changes to building codes would support the suggested strategies. In addition, cultural resistance and a lack of awareness might create a challenging context for OB. The residents of social housing projects in Egypt have traditionally received their units in a fully finished state. The participatory approach of OB, which involves user co-design, may encounter resistance because of users’ unfamiliarity or uncertainty about quality and durability standards. The feasibility of OB-based solutions heavily relies on stakeholder dynamics. The current project dynamics show that professionals lead all stages, starting from conceptualization up to design, implementation, and maintenance, while the OB system changes the stakeholder roles by involving users. The shift in control between professionals and users could lead to conflicts because professionals might oppose user involvement due to worries about the design quality and legal responsibility. Users who lack experience with participatory processes face challenges in making well-informed decisions, which results in project delays and substandard results.

The successful implementation of OB in Egypt’s SHPs requires addressing institutional, financial, cultural, and technical challenges through collaborative stakeholder dynamics. OB redefines the professional and user roles, which results in more affordable solutions, better adaptability, and stronger community involvement.

Furthermore, a novel aspect of this research was the proposed integration of service courts and attached building blocks. This introduces a unique application of OB principles that are specifically designed to address Egypt’s unique urban density challenges. This innovation is particularly significant, as it bridges a notable gap in the literature, which has historically predominantly focused on detached or semi-detached OB models. Our findings demonstrate that the adaptability and flexibility inherent in OB can be successfully applied to high-density, attached housing configurations, offering a viable pathway for scalable, user-centric housing solutions in rapidly urbanizing environments where land is scarce and vertical growth is inevitable. This provides a new lens through which to consider OB’s global applicability, extending its relevance beyond suburban or lower-density contexts.

4. Conclusions

This study features one of the first housing design proposals made with OB principles in Egypt. Driven by rising housing costs and declining household incomes, it addresses a critical gap in the literature. It examines the revival of the open building movement in low-income housing, particularly in Egypt, by analyzing past successes and future potential, with a focus on Egypt’s low-income social housing projects to determine how open building strategies can optimize current designs.

The open building movement helps with creating resilient and adaptive housing that can accommodate users’ needs and adapt with the family life cycle. The proposed renovation of the social housing project, employing open building principles, offers four distinct dwelling types with varying sizes and designs. This allows residents to select the dwelling best suited to their needs and provides flexibility to adapt or modify the design over time. The proposed alternatives incorporate the concept of sectors, zones, and margins, enabling the creation of service courts or pockets that efficiently group kitchens and toilets for easier maintenance and allow semi-attached or attached building blocks for more layout efficiency.

This research demonstrates how open building (OB) addresses Egypt’s low-income housing challenges by enhancing the affordability and flexibility. The proposed framework presents four dwelling typologies (ranging from 57.6 to 122.4 m2) incorporating a zone and margin analysis to create adaptable layouts that align with diverse family requirements and economic capabilities. The designs enable user participation through incremental implementation and facilitating unit expansion, which reduces the initial construction costs and promotes socio-cultural engagement. The study’s focus is low-income housing, which presents discussions and findings unique to the Egyptian context, though this limits the generalizability to other income levels or regions with different regulatory systems.

The research offers a theoretical analysis of OB-based designs to urge Egyptian government policy makers to update its social housing guidelines by adopting modular design principles, standardized infill systems, and resident-driven design approaches to create adaptable housing that bridges the gap between supply and demand while promoting sustainable urban development. However, while the proposed OB-based renovation is theoretically sound, its practical implementation remains untested.

Future research could apply OB to different housing projects for middle- and high-income groups or different prototypes in Egypt, such as educational and administrative buildings, as a tool for renovation and rehabilitation.

The originality of this contribution is underscored through revisiting historical applications of OB in Egypt and proposing actionable guidelines for policymakers and real estate developers to revive this approach in modern social housing projects to incorporate modularity and infill standardization (Table 4).

Table 4.

Guidelines summary for social housing projects as open building concept. Source: authors.

Author Contributions

R.N.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, supervision and visualization, investigation, and resources. D.A.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, supervision and visualization, investigation, and resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to our professors who supported our research process. Their contributions have significantly enriched our understanding of the subject.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OB | Open building |

| SHP | Social Housing Program |

References

- Habraken, N.J. Supports an Alternative to Mass Housing; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habraken, J. The Structure of the Ordinary Form and Control in the Built Environment; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, S. Open Building For Resilient cities conference. In Four Decades of Open Building Implementation, Realizing Individual Agency in Architectural Infrastructures Designed to Last; Kendall, S., Ed.; Council on Open Building: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, S.H.; Habraken, N.J. Open Building for Architects, Professional Knowledge for an Architecture of Everyday Environment; Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, Z.; Li, Y. Open Building as a Design Approach for Adaptability in Chinese Public Housing. World J. Eng. Technol. 2019, 7, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, S. Open Building: An Approach to Sustainable Architecture. J. Urban Technol. 1999, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, W.K.; Ho, D.C.W. Open Building Implementation In High-Rise Residential Buildings In Hong Kong. Open House Int. 2011, 36, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, S.; Teicher, J. Residential Open Building; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yingying, J.; Beisi, J. The Tendency of ‘Open Building’ Concept in the Post-Industrial Context. Open House Int. 2011, 36, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errante, L.; Caniglia, M.R. Challenging Contemporary Housing: Ralph Erskine’s Byker Wall. In Networks, Markets & People; Calabrò, F., Madureira, L., Morabito, F.C., Mantiñán, M.J.P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, D.; Carrasco, S. Contested incrementalism: Elemental’s Quinta Monroy settlement fifteen years on. Front. Archit. Res. 2021, 10, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, M. ZEMCH: Toward the Delivery of Zero Energy Mass Custom Homes; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Environment Program. Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction; UN Environment Program: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Elttouny, S.; Abdelkader, N. Shaping-Development-in-Limited-Resources-Settings; LAP Lambert Academic Publisher: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2013; Available online: https://publication-cpas-egypt.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Shaping-Development-in-Limited-Resources-Settings.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Estaji, H. A Review of Flexibility and Adaptability in Housing Design. Int. J. Contemp. Archit. “New ARCH” 2017, 4, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manifesto OpenBuilding.co. 2021. Available online: https://www.openbuilding.co/manifesto (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Habraken, N.J. The Uses of Levels. Open House International. 2002. Available online: https://www.habraken.com/html/downloads/the_uses_of_levels.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Habraken, N.J. Transformations_of_the_Site; Atwater Press: Atwater, MI, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Nasreldin, R.; Ibrahim, A. How the Covid-19 Pandemic Affects Housing Design to Adapt with Households’ New Needs in Egypt? In Proceedings of the Research and Innovation Forum 2022, RIIFORUM 2022, Athens, Greece, 27–29 April 2022; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 791–807. [Google Scholar]

- Habraken, N.J.; Boekholt, J.T.; Dinjens, P.J.D.; Thijssen, A. Variations: The Systematic Design of Supports. 1976. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:107204328 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Elttouney, S.; Abdelkader, N. Planning & Development of a Residential District; Alaraby: Lusail, Qatar, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Groat, L.N.; Wang, D. Architectural Research Methods; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Rahman, H.M.; Elsayed, Y.M.; Abouelmagd, D. Assessing the Egyptian Public Housing Policies and Governance Modes (1952–2020)—Towards Achieving a Sustainable Integrated Urban Approach. J. Arts Archit. Res. Stud. 2020, 1, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, N.M.; Kamel, R.R.; Elsherif, D.M.; Nasreldin, R.I. Realization of the key aspects of the right to adequate housing in affordable housing programs in Egypt. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2021, 68, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawkat, Y. Egypt’s Housing Crisis: The Shaping of Urban Space; AUC Press: Cairo, Egypt, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nasreldin, R. Cultural Adequacy and Visual Privacy in Public Housing Design: Between Integration and Isolation. J. Urban Res. 2025, 49, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elttouney, S.; Abdelkader, N. Decrying Sensible Housing Development—Recapitulating Incremental, Partially Completed Low-Cost Housing, Egypt; Decades Later. In Shaping Development in Limited Resources Settings; Elttouney, S., Abdelkader, N., Eds.; Lap Lambert: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rehan, R. Review and Evaluation of Low Cost Housing Prototypes, Referring to 6 October City. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Engineering, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- NUCA. New Urban Communities Authority (NUCA). Available online: http://www.newcities.gov.eg/Default.aspx (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- UN-Habitat. United Nations Human Settlements Programme. Egypt Housing Profile. 2016. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/1525977522wpdm_Egypt%20housing%20EN_HighQ_23-1-2018.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- UN-Habitat. United Nations Human Settlements Programme. Egypt Housing Strategy. 2020. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/09/egypt_housing_strategy.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Egyptian Code No. 602; Egyptian Code for Designing the House and Residential Group. HBRC: Cairo, Egypt, 2009.

- UN-Habitat. EGYPT Housing Profile; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).