Abstract

Providing older people with quality long-term care (LTC) contributes to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3—Good Health and Well-being. Person-Centered Care (PCC) is the optimal approach that enhances the quality of life for older adults residing in LTC facilities. This study develops the Long-Term Care Unit Environment Assessment Tool (LTCU-EAT) to assess how LTC environments support PCC goals. The study was conducted in five steps. (1) Reviewing and revising assessment items based on existing literature; (2) Preliminary assessment and protocolling with expert opinions; (3) On-site assessments conducted by two raters among 21 LTC units across 13 facilities; (4) Reliability test of assessment items; (5) Scoring and reliability test of LTC unit samples. The LTCU-EAT, comprising 89 items distributed across 12 subscales within four themes, was developed based on a summary of 14 PCC goals. A total of 82 items (92.13%) demonstrated strong inter-rater reliability. The assessments of all LTC unit samples displayed good criterion-related validity. The LTCU-EAT is a valuable tool for conducting post-occupancy evaluation (POE) of LTC facilities, systematically evaluating the level of environment support for PCC, and providing empirical evidence for future research, policy and practice.

1. Introduction

We are living on a rapidly aging planet. From 2020 to 2050, the global population aged over 60 years will double from 1 billion to 2.1 billion, reaching 22% of the total population. Notably, the number of the oldest-old people (aged 80 years or above) is expected to triple between 2020 and 2050, reaching 426 million [1]. Providing older people with high quality long-term care (LTC) has become a major action of the UN Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030), thereby supporting the realization of the United Nations Agenda 2030, and contributes to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3—Good Health and Well-being [2,3].

In response to the growing pressure on aging care, efforts have been made globally for decades to explore improved approaches. Person-Centered Care (PCC) has been empirically validated as the optimal approach that enhances the quality of life for older adults residing in LTC facilities [4]. A long-term care facility is described as a skilled nursing facility which provides a range of personal and health care with a focus on medical, nursing care, safety, and support with activities of daily living, especially for the older adults [5]. PCC acknowledges and comprehends the personal value of each individual, which should be respected during caregiving [6]. In the 1980s, a Culture Change movement in long-term care was initiated in the United States. It advocated for a shift from medical care models to PCC models within LTC facilities [7]. This movement emphasizes that LTC facilities should be perceived not merely as healthcare institutions but rather as homes with comprehensive care services [8].

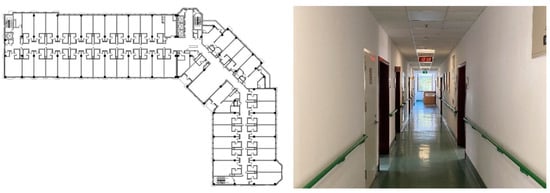

Under the influence of PCC and the Culture Change movement in long-term care, the physical environment design of LTC facilities has undergone a significant transformation. This transformation is primarily characterized by deinstitutionalization and the adoption of small-scale layout approaches. A notable change can be observed in the emphasis on detailed requirements for LTC units. For instance, there has been a shift towards reducing double-loaded corridor configurations (Figure 1) in preference for small group clusters of units (Figure 2), aiming to create an environment that promotes familiarity and a sense of home [9,10]. Each unit is equipped with comprehensive activity, dining, and support spaces that can be managed independently. Each unit provides access to outdoor areas. Nursing stations are designed to be open and less institutionalized [11,12]. Some studies have demonstrated that these innovative PCC-based LTC facilities significantly improve residents’ quality of life compared to traditional ones [13]. Moreover, they contribute to better family satisfaction as well as staff motivation and efficiency at work [14,15].

Figure 1.

Traditional Double-loaded Corridor Layout. (The left figure is a standard floor plan example of a LTC facility in Beijing, China, designed with double-loaded corridor configurations; the right figure is the photo of the corridor of a welfare LTC facility in Shanghai, China).

Figure 2.

Small Group Clusters of LTC Units. (The left figure is a standard floor plan example of a LTC facility in Japan designed for group home mode; the right figure is the shared living room of a LTC facility in Beijing, China, which is the No. 4 facility sample in this study).

In recent years, China’s long-term care has been influenced by the progressive nursing concepts introduced by PCC from the western world. However, comparative cultural backgrounds significantly diverge, particularly among the older generation. Chinese older adults, influenced by traditional cultural values and collectivism memories, exhibit distinct preferences in terms of privacy, interpersonal communication, and living arrangements when compared to their western counterparts. Some Chinese scholars have attempted to integrate the PCC concept with the local context and propose design strategies for LTC facilities [16,17].

However, it is important to acknowledge the variation in the quality of LTC facility environmental design worldwide. A considerable number of facilities fall short in supporting PCC goals. For instance, a study conducted on LTC facilities in Sweden revealed satisfactory safety measures for older individuals but lower quality regarding cognitive support and privacy [18]. Similarly, Wahlroos et al. assessed LTC facilities in Finland and identified a need for improvement in the domains of normalness and cognitive support in the physical environment [19]. Furthermore, the deficiencies of LTC facilities in supporting PCC goals have been exposed in developing countries that entered the aging society later, due to a lack of studies, assessment tools, and design guidelines [20]. Identified problems in China’s LTC facilities include neglecting basic principles, such as fall prevention, resulting in reducing residents’ safety [21], or having a hospital-like decoration style that makes people feel depressed [22]. Since there will be a significant future demand, it is urgent to assess the extent to which existing LTC facility environments support PCC goals, thereby facilitating evidence-based design (EBD).

There are currently numerous assessment tools available for LTC facilities. This paper identifies 13 widely utilized tools through a literature review (Table 1). Many of these instruments underwent systematic development processes. For instance, MEAP, SCEAM, TESS-NH, and EAT were developed through comprehensive literature reviews followed by expert judgment [23]. However, most of these tools were developed before PCC concepts gained widespread application in environmental design practices. Therefore, none of these instruments targeted PCC as the assessment focus, limiting their applicability in meeting contemporary demands for LTC services. Due to the lack of valid and reliable instruments for assessing the matching relation between the environment design of LTC units and PCC goals, post-occupancy evaluations (POE) are seldom conducted adequately, especially in China. In contrast to Western practices of identifying issues through POE, Chinese studies lack effective evaluation methods and practices for addressing the user needs [24]. Consequently, there is a lack of feedback to building planners, architects and care staff on how environmental elements works with PCC in practice. Additionally, it had been reported that most instruments suffered from shortcomings, such as relying on professional expertise [25,26], and the assessment items were organized by design principles rather than physical environment elements. In China, the evaluation criteria of relevant existing standards mainly focus on meeting the basic needs of residents, such as accessible design and environmental sanitation, instead of paying much attention to the older adults and staffs’ quality of life [27,28]. These factors contributed to confusing assessment procedures and limited usability. Considering the significant impact of cultural values on care preferences and facility design [29,30], it is essential to develop assessment tools that are adaptable to Chinese cultural contexts.

Table 1.

Widely Used Existing Assessment Tools for LTC Facilities.

Therefore, this paper develops the Long-Term Care Unit Environment Assessment Tool (LTCU-EAT) to address the above research gaps, aiming to provide a practical guide for assessing the physical environment quality of LTC units from a person-centered perspective. The assessment results are expected to identify current issues, provide empirical evidence for future environment design and revision of relevant policies and standards, enhance the quality of built environment in LTC units, and improve quality of person-centered care for the older adults.

2. Methods

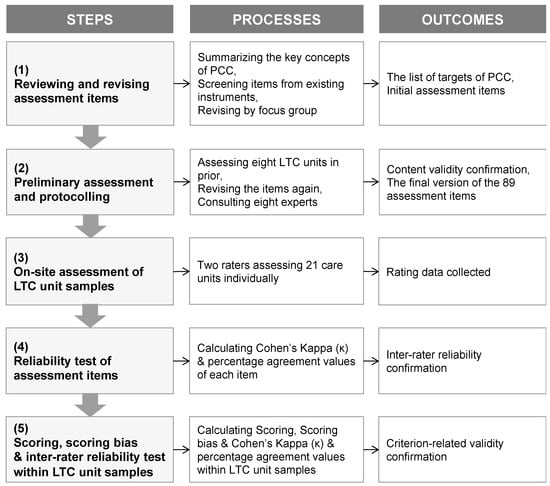

This study developed the LTCU-EAT following five steps. (1) Reviewing and revising assessment items: summarizing the key concepts of PCC, screening items from existing instruments, and revising by focus group method; (2) Preliminary assessment and protocolling: prior assessment of eight LTC units and revising the items again, consulting eight experts, confirming content validity, and determining the final 89 items; (3) On-site assessment of LTC unit samples: two raters assessing 21 LTC units individually; (4) Reliability test of assessment items: inter-rater reliability test of each item; (5) Scoring, scoring bias and inter-rater reliability test within LTC unit samples: confirming the criterion-related validity.

The tool was tested among LTC facilities for older adults in China. The detailed study procedure is described as follows (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Flow Chart of the Methods of Development of the LTCU-EAT.

2.1. Step (1) Reviewing and Revising Assessment Items

This study summarized the key concepts of PCC through a systematic literature review. Compared to traditional care models, the concept of PCC primarily influences the environmental design of LTC units [8]. Therefore, this instrument focused on assessing LTC units. Other aspects, such as location selection, central kitchen, and staff living space that were not closely associated with PCC concepts, were excluded from the scope of assessment.

On this basis, according to existing assessment tools, scales, empirical studies, reviews, guidelines and other literature related to PCC-based environment design of LTC units, key points were extracted and revised as assessment items. The research team conducted a preliminary screening of the key points and determined the assessment items using the focus group method, which involved following three routes.

International references: the LTCU-EAT incorporated certain items from existing tools. For example, assessment item 23 (see Supplementary Materials S1), regarding personalization of bedroom layout, was derived from PEAP (Japanese version), the E–B Model, and EAT [31,36,37].

Local references: existing studies have emphasized that the development of assessment tools necessitates a strong foundation in policies and culture [44]. Therefore, it is not possible to completely detach from the main cultural background. Nevertheless, the methodologies, processes, and conceptual frameworks employed in tool development possess a universal nature that allows for adaptation and translation across diverse cultural backgrounds. Since the LTCU-EAT was developed and tested in China, some items referred to Chinese policy documents, design standards and codes, especially the Guidelines of Classification and Accreditation for Long-term Care Organization, which was co-authored by a researcher involved in this study [45].

Integration and composition: a majority of items were derived through a comprehensive analysis of different categories of references, including existing instruments, scales, design standards, codes, research papers, and guidelines. During the development of the LTCU-EAT, there were instances where certain content requiring assessment may have multiple sources that can be referenced, or no direct reference items available. In either of the situations, an integration and composition method were utilized.

2.2. Step (2) Preliminary Assessment and Protocolling

To validate the applicability of the assessment indicators and ensure their adaptation to the construction and occupancy state of LTC units in the Chinese context, the study conducted a preliminary assessment to determine the suitability of items derived from literature research in eight LTC facilities. Subsequently, modifications were made to nine items that posed challenges in evaluation or did not align with actual usage scenarios.

This study then consulted the opinions of eight experts to assess the content validity. These experts had backgrounds, including the architecture, gerontology, geriatrics, nursing, and urban planning fields, related to the preliminarily identified items. All the experts had strong experience in either research or practice. These experts made comments on each individual item concerning (a) the relevance to PCC; (b) the relevance to local settings (i.e., China in this research); (c) the importance of unit environment design; (d) clarity and operability. The procedure partially referred to the COSMIN model steps [46,47]. According to the results of expert evaluation, items were further screened and optimized to improve the validity of assessment indicators.

2.3. Step (3) On-Site Assessment of LTC Unit Samples

A total of 13 LTC facilities were selected for the on-site assessment procedure (Table 2). Supplementary Materials S2 presents plans and photos of the 13 facilities. The selection strategy for the facilities took into consideration facility types (independent, community embedded, or within a retirement community), construction type (newly built or renovated), geographical location (North/South/East/West; metropolis or small city), opening time (before 2000, between 2000 and 2010, or after 2010), building area (large, medium, or small scale), and number of floors (lower floors or higher floors). Each selected facility had one to three LTC units for assessment purposes. In total, there were 21 LTC units included in the assessment.

Table 2.

Features of LTC Unit Samples in this Study.

The assessment was conducted by two research managers acting as independent raters. Each LTC unit was observed on the same day through systematic on-site visits, without any coordination between the raters. Each item was scored “0 or 1”, with certain items including a “0.5” score to differentiate the degree. Items not applicable were marked “NA”. Data were collected using either paper sheets or electronic spreadsheets. Furthermore, the raters captured detailed photos of environmental features within each LTC unit for future reference.

2.4. Step (4) Reliability Test of Assessment Items

The reliability of each item was measured. Inter-rater reliability was determined by comparing the assessment results of the two raters as part of the reliability analysis. In order to evaluate the reliability of the individual items, the inter-rater reliability of the repeated assessment data of the same item by the two raters was evaluated. Cohen’s Kappa statistic (κ) was calculated for the effects of the chance agreement to assess the reliability of both dichotomous and Likert-like variables, and it is widely used in assessment tool development [48,49]. Cohen’s Kappa value can be evaluated using Landis and Koch’s classification: Excellent to good (κ ≥ 0.60); Moderate (0.60 > κ ≥ 0.40); Fair to poor (κ < 0.40) [49,50,51,52].

Given that Cohen’s Kappa calculations rely on the presence of variability in ratings, the value may be low or with p > 0.05 when one or both raters exhibit limited rating variability [53,54]. In this study, certain items exhibited inadequate variability in the responses of the raters. Consequently, the percentage agreement was also calculated for these items to exclude those that were misjudged due to insufficient variability. The results of the percent agreement were classified to indicate reliability as follows: percent agreement ≥75% (for dichotomous response items: 0/1) and percent agreement ≥60% (for ordinal or continuous response items: 0/0.5/1, 0/1/NA, 0/0.5/1/NA) were considered reliable [54,55]. All the analysis processes were performed through the SPSS 27 Software.

2.5. Step (5) Scoring, Scoring Bias and Inter-Rater Reliability Test within LTC Unit Samples

Existing literature on the assessment of LTC facility environments typically focuses solely on reliability testing of the item scale. However, we have identified that the difference in environment quality of LTC unit samples may also exhibit variations in agreement between two raters’ assessment results, leading to bias in the total score assigned to an LTC unit sample by the two raters. Therefore, we also performed three calculations which could contribute to confirming criterion-related validity:

Scoring: summing up each rater’s responses for every item and dividing it by the number of valid items (89 minus the number of “N/A” items). The score for each LTC unit sample is the average rating from both raters.

Scoring bias: calculating the difference value between scores given by the two raters.

Reliability of ratings within LTC unit samples: calculating Percent Agreement and Cohen’s Kappa value for these samples.

3. Results

3.1. The 89-Item LTCU-EAT Supporting the 14 PCC Goals

14 goals of PCC were summarized through literature review. These goals were classified into three major needs: physiological needs of older adults, psychological needs of older adults, and needs of staff. The basic concept of each PCC goal is explained in Table 3.

Table 3.

14 PCC goals and related items in the LTCU-EAT.

Based on the 14 PCC goals, the 89-item version of the LTCU-EAT was developed. Each item may contribute to 1–4 targets. The items were primarily organized by 12 subscales under 4 themes: Overall Layout (8 items), Functional Space (62 items), Facilities and Equipment (6 items), and Sensory Environment (13 items) (Table 4). The judging criteria were explained through comprehensive descriptions provided for each individual item. The complete tool is available in Supplementary Materials S1.

Table 4.

Four themes and 12 subscales of the LTCU-EAT.

3.2. Inter-Rater Reliability of Items

Table 5 displays the results of the inter-rater reliability test of each item of the LTCU-EAT. A total of 82 items (92.13%, among the 89 items) exhibited excellent to moderate Cohen’s Kappa values (with adequate variability) or high level of percentage agreement values (with inadequate variability), which indicated sufficient inter-rater reliability. The remaining seven items (7.87%) showed low reliability.

Table 5.

Item inter-rater reliability.

3.3. Scoring, Scoring Bias and Inter-Rater Reliability within LTC Unit Samples

In addition to the reliability test of the assessment items, the analysis of the scoring of each LTC unit also contributes to the criterion-related validity confirmation of the tool (Table 6).

Table 6.

Scoring, scoring bias and inter-rater reliability of LTC unit samples.

Scoring: In this study, we tried to choose different LTC units in PCC support quality based on information from the pre-assessment step. The results of scoring indicated that the LTCU-EAT can identify the difference in PCC support quality. The lowest score of the 21 LTC unit samples was 49.61, while the highest was 92.98. The average score was 74.62.

Scoring bias: The scores given by two raters for each LTC unit sample exhibited slight variation, with an average bias of 4.35 (out of 100). Only one sample demonstrated a significant high scoring bias, reaching 14.49.

Inter-rater reliability within LTC unit samples: all the LTC unit samples showed both high percent agreement and excellent to moderate Cohen’s Kappa value, indicating that the raters using the LTCU-EAT generally have consistent assessment results for the same LTC unit. The average percentage agreement was 82.10%, and the average Cohen’s Kappa was 0.714.

4. Discussion

4.1. Reliability and Validity

The inter-rater reliability of 82 items (92.13%) among the total of 89 items indicated a satisfactory level. This suggests that LTCU-EAT demonstrates high reliability, which can be attributed to multiple rounds of revisions based on expert consultations, focus group discussions, and pre-assessments. The tool aimed to minimize unclear assessment criteria and enhance objectivity in subjective judgments, resulting in greater consistency among different raters’ scoring results.

The content validity was confirmed during the expert consultation process. The analysis of scoring for each LTC unit sample demonstrated that the tool effectively discriminates between units with varying levels of design quality, thereby confirming its criterion-related validity.

Although the LTCU-EAT demonstrated overall reliability, there were still seven items (7.87%) that exhibited low levels of reliability. The factors influencing the reliability of these items can be primarily classified into three situations.

Firstly, due to inevitable subjective judgments, there was a significant amount of discretion in scoring. For example, item 19 stated: “The storage spaces within the room are sufficient, with no stacked things impeding movement or daily activities.” The two raters had a discrepancy in determining how much storage space should be considered sufficient for an older adult’s resident room. This difference may stem from varying understandings of environmental design quality among raters. Similar issues could also be observed in item 54, assessing as “dead-end corridor”, item 82, about “homelike lighting atmosphere”, and item 84, regarding “well-ventilated environment”.

Secondly, in one item, there were too many scoring points, which made it easy to ignore certain details during the assessment process. For example, item 73 stated: “All types of signs must meet the following requirements: a. They should be securely installed and free from any defects that may pose a safety risk to residents. b. They should be accurately positioned and highly visible for residents, avoiding obstruction from lights, cameras, plants, or other facilities. c. They should be designed with consideration for residents’ visual characteristics by using larger texts and high-contrast colors for easy recognition.” This item contained the comprehensive requirements of the signage system. However, its excessive content rendered it complex and made it easy to make mistakes by raters. Similar challenges could also be observed in item 65 on “design details in the laundry room”.

Thirdly, some items required certain professional knowledge to allow judgement. For example, item 7 stated: “The layout of each LTC unit is flexible and adaptable, for example, units can be separated or combined to fit varying needs because of the complete functional configurations.” This requires raters to have knowledge of nursing and environmental design. In the future popularization of this tool, consideration still needs to be given on how individuals without a professional background can use it effectively. The LTCU-EAT had made efforts to avoid this issue, so the problem was not very common.

4.2. Advantages in Operability

Compared to existing tools, the LTCU-EAT had advantages in terms of operability.

Firstly, the LTCU-EAT classified items based on environmental design elements that correspond to the walking route of an LTC unit. This approach effectively streamlined raters’ assessment procedures without frequent backtracking to locate evaluation scenarios. In contrast, most existing instruments organize assessment items according to environmental design principles, such as accessibility and safety [31,33]. This mismatch between the organizational logic of assessment tools and the built environment may lead to confusing assessment processes and limited tool operability.

Secondly, the items of the LTCU-EAT were detailed and generally straightforward to evaluate, requiring minimal professional expertise from raters and ensuring ease of future popularization and utilization. Notably, it has been reported that certain items in existing assessment tools for LTC facilities, such as PEAP and the E–B Model, were found to lack detail and were considered to be too professional. Many of their items required expert judgment based on knowledge and experience, which made the assessment difficult to operate [25,26]. However, during the field test of the LTCU-EAT, these issues were significantly reduced.

Thirdly, the LTCU-EAT demonstrated a relatively unbiased approach, ensuring fair assessments for both larger high-end projects and smaller community projects. Throughout the tool development process, this study considered different types of LTC unit samples to ensure compatibility with all facilities. This included large-scale new facilities, renovated facilities, as well as extremely small-scale ones. This consideration was prompted by literature suggesting that certain instruments, like PAF and EQUAL, may exhibit a bias towards larger facilities, which has led to limited applicability to smaller ones [41,43].

Additionally, the LTCU-EAT was expected to be applicable to regions with similar cultural backgrounds, and explored a comprehensive methodology for developing an operational assessment tool. Previous research has highlighted the importance of grounding assessment tool development in local policies and cultures [44]. Therefore, it is essential to acknowledge that complete detachment from a local cultural background is not feasible. Nevertheless, although the LTCU-EAT was developed and tested in China, its methodologies, processes, and conceptual frameworks possess a universal nature that facilitates adaptation and translation across diverse cultural contexts.

4.3. Effectiveness of Assessing the Environmental Support for PCC

The development of the LTCU-EAT aimed to effectively address evolving needs and support for residents and staff in LTC facilities, reflecting current PCC concepts. Multiple items contributed to physiological and psychological needs of older adults. For instance, item 23 emphasized that “The rooms have spaces and facilities for personal photographs, books, and furniture, offering residents the flexibility to arrange their rooms as they wish.” This assessment item facilitated recognition of a diverse and flexible physical environment within LTC units, enabling residents to exercise choice and control over their living spaces based on personal preferences (PCC Target (7)—Choice and Control). Additionally, the convenience of staff service also significantly impacts residents’ quality of life. The LTCU-EAT included assessments that highlight this aspect too. For example, item 8 stated that “The layout of each LTC unit is easy for staff to serve residents, providing convenient working paths.” This assessment item helped determine whether the physical environment adequately supports staff in providing care and services without encountering difficulties (PCC Target (12)—Service Support). Based on the 14 goals of PCC, the LTCU-EAT showed potential for the person-centered improvement of LTC unit environment.

4.4. Implications for Policy and Practice

The LTCU-EAT can play a crucial role in policy development and various stages of practice. During the planning and design process, the LTCU-EAT can serve as a valuable guide for designing PCC-based LTC units and facilitating interdisciplinary communication among experts from architecture, engineering, and nursing. During the occupancy period, care staffs can utilize this user-friendly tool to learn how to implement PCC principles in different environments. During the post-occupancy evaluation (POE) procedure, the LTCU-EAT holds significant value due to its validity, reliability, and ease of use in exploring variations in environmental quality. Consequently, it can offer valuable insights to enhance future policies, design codes, and standards.

4.5. Limitations and Future Research

This study is subject to certain limitations. Firstly, despite efforts made to ensure accuracy, clarity, and objectivity in formulating the items, it was challenging to completely avoid incorporating some subjective judgment-based items into the tool. Moreover, due to the extensive number and detailed nature of the LTCU-EAT items, assessing a single LTC unit requires a considerable amount of time (raters typically report needing approximately 2 h), which may lead to fatigue and potential errors during the assessment process. Furthermore, this study had a limited sample size under examination, making further validation through additional samples highly valuable.

There are potential directions for further research on the LTCU-EAT. The first future research direction involves optimizing the items to enhance their precision, objectivity, and conciseness. Additionally, apart from revising the items for increased detail and specificity, an alternative approach with potential is integrating a condensed version of the assessment tool (e.g., LTCU-EAT mini version) with a small selection of highly reliable and important indicators, aiming to improve efficiency and universality. The second direction focuses on promoting widespread implementation of the LTCU-EAT as a tool for evaluating the quality of built environments in LTC facilities, identifying current issues, and proposing optimization strategies. The third direction entails utilizing LTCU-EAT for interdisciplinary studies that investigate how residential environmental factors impact the physical and mental health of older adults.

5. Conclusions

PCC concepts are now widely adopted in long-term care LTC facilities worldwide. However, there is a lack of reliable and valid instruments to assess how LTC environments support PCC goals. This study presents the development and evaluation of the LTCU-EAT, specifically designed to assess the provision of PCC in LTC units, aiming to address existing research gaps. The tool comprised 89 items across 12 subscales under four themes, supporting the 14 PCC goals. A field test involving 21 LTC units was conducted to establish the reliability and validity of the tool. Notably, 82 items (92.13%) demonstrated high inter-rater reliability, while the tool also exhibited satisfactory content and criterion-related validity. The LTCU-EAT classified items based on environmental design elements that correspond to the walking route of a LTC unit, effectively streamlining raters’ assessment procedure. The assessment items were detailed, comprehensible and did not necessitate raters to possess much professional expertise. The LTCU-EAT was expected to effectively identify issues related to PCC support, providing empirical evidence for future construction projects and revisions of design standards. It had potential to enhance the quality of built environments in LTC facilities, improving the quality of life for older adults, supporting the realization of the United Nations Agenda 2030, and contributing to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on people’s good health and well-being.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings14092726/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C. and C.W.; Data curation, Y.C. and C.W.; Formal analysis, Y.C., J.Z. and C.W.; Funding acquisition, Y.C. and C.W.; Investigation, Y.C. and C.W.; Methodology, Y.C. and C.W.; Project administration, Y.C. and C.W.; Resources, Y.C. and C.W.; Software, J.Z. and C.W.; Supervision, C.W.; Validation, Y.C. and C.W.; Visualization, Y.C.; Writing—original draft, Y.C. and C.W.; Writing—review and editing, Y.C., J.Z. and C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 52308010]; ZJU100 Young Professor Program [grant number 113000*1942224R3/012]; the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [grant number 2024CDJXY014]; and Chongqing Municipal Construction Science and Technology Program [grant number 2023—No. 6-7]. The funding bodies did not influence this paper in any way prior to circulation.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to the management staff, caregivers and residents in the LTC facilities mentioned in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to resolve typographical errors. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- WHO. Ageing and Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- United Nations. The 17 Goals | Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- WHO. WHO’s work on the UN Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030). 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Chaudhury, H.; Hung, L.; Badger, M. The role of physical environment in supporting person-centered dining in long-term care: A review of the literature. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 2013, 28, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute on Aging. Residential Facilities, Assisted Living, and Nursing Homes. 2020. Available online: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/residential-facilities-assisted-living-and-nursing-homes (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Kitwood, T.M. Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Holder, E.L. Consumer Statement of Principles for the Nursing Home Regulatory System; National Citizens’ Coalition for Nursing Home Reform: Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, M.J. Person-centered care for nursing home residents: The culture-change movement. Health Aff. 2010, 29, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regnier, V. Housing Design for an Increasingly Older Population: Redefining Assisted Living for the Mentally and Physically Frail; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley, A.; Calderon, R.; Faghri, A.; Yuan, D.; Li, M. Contemporary Designs for Long-Term Care (LTC) Facilities. J. Build. Constr. Plan. Res. 2022, 10, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geboy, L. Linking person-centered care and the physical environment: 10 design principles for elder and dementia care staff. Alzheimer’s Care Today 2009, 10, 228–231. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkowski, E.T. Implementing Culture Change in Long-Term Care: Benchmarks and Strategies for Management and Practice; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Adlbrecht, L.; Nemeth, T.; Frommlet, F.; Bartholomeyczik, S.; Mayer, H. Engagement in purposeful activities and social interactions amongst persons with dementia in special care units compared to traditional nursing homes: An observational study. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2022, 36, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownie, S.; Nancarrow, S. Effects of person-centered care on residents and staff in aged-care facilities: A systematic review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2012, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Weng, R.H.; Wu, T.C.; Hsu, C.T.; Hung, C.H.; Tsai, Y.C. The impact of person-centred care on job productivity, job satisfaction and organisational commitment among employees in long-term care facilities. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2967–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Hu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Han, H. Research on the design of living room in nursing home for the elderly with dementia with the concept of person-centered care. Archit. Cult. 2021, 8, 211–215, In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Research on physical environments of dementia car facility under “person-centered care” philosophy: A case study of facilities in the United States. Archicreation 2020, 5, 48–55, In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- Nordin, S. The quality of the physical environment and its association with activities and well-being among older people in residential care facilities. Ph.D. Thesis, Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlroos, N.; Stolt, M.; Nordin, S.; Suhonen, R. Evaluating physical environments for older people—Validation of the Swedish version of the Sheffield Care Environment Assessment Matrix for use in Finnish long-term care. Int. J. Older People Nursing 2021, 16, e12383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bian, X.; Wang, J. Understanding person-centered dementia care from the perspectives of frontline staff: Challenges, opportunities, and implications for countries with limited long-term care resources. Geriatr. Nurs. 2022, 46, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Ran, H.; Deng, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, L. Paid caregivers’ experiences of falls prevention and care in China’s senior care facilities: A phenomenological study. Frontiers 2023, 11, 973827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, M.; Li, J.J. Adaptive design of elderly care facilities: Problems and suggestions. Des. Community 2018, 1, 32–41, In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- Elf, M.; Nordin, S.; Wijk, H.; Mckee, K.J. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of instruments for assessing the quality of the physical environment in healthcare. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 2796–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Du, J.; Mohammadpourkarbasi, H. A systematic review of investigations into the physical environmental qualities in Chinese elderly care facilities. In Human Factors in Architecture, Sustainable Urban Planning and Infrastructure, Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics (AHFE 2022), New York, NY, USA, 24–28 July 2022; Maciejko, A., Ed.; AHFE International: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 58, pp. 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S. Group, D.I.C.E. The design of caring environments and the quality of life of older people. Ageing Soc. 2002, 22, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloane, R.D. The therapeutic environment screening survey for nursing homes (TESS-NH): An observational instrument for assessing the physical environment of institutional settings for persons with dementia. J. Gerontology. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2002, 57, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Standard for Design of Care Facilities for the Aged, JGJ450-2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/gongkai/zhengce/zhengcefilelib/201807/20180702_236618.html (accessed on 20 November 2023)In Chinese.

- State Administration of Market Supervision and Administration, Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China. Classification and Accreditation for Senior Care Organization; State Administration of Market Supervision and Administration, Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China. Available online: http://c.gb688.cn/bzgk/gb/showGb?type=online&hcno=DDB955F6E857C91A6534921ACF8725CA (accessed on 20 November 2023). In Chinese.

- Xiao, L.D.; Shen, J.; Paterson, J. Cross-Cultural Comparison of Attitudes and Preferences for Care of the Elderly Among Australian and Chinese Nursing Students. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2013, 24, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.W.B. Advance Care Planning in Chinese Seniors: Cultural Perspectives. J. Palliat. Care 2018, 33, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, J.; Silverstein, N.M.; Hyde, J.; Levkoff, S.; Lawton, M.P.; Holmes, W. Environmental correlates to behavioral health outcomes in Alzheimer’s special care units. Gerontol. 2003, 43, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P.; Weisman, G.D.; Sloane, P.; Norris-Baker, C.; Calkins, M.; Zimmerman, S.I. Professional environmental assessment procedure for special care units for elders with dementing illness and its relationship to the therapeutic environment screening schedule. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2000, 14, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, S.E.; Morgan, D.G. Functional outcomes of nursing home residents in relation to features of the environment: Validity of the professional environmental assessment protocol. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2012, 13, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, R. An environmental audit tool suitable for use in homelike facilities for people with dementia. Australas. J. Ageing 2011, 30, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slaughter, S.; Calkins, M.; Eliasziw, M.; Reimer, M. Measuring physical and social environments in nursing homes for people with middle- to late-stage dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2006, 54, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, K.; Koga, T.; Numata, K. Practice Manual for Facility Environment Construction for Dementia Care Based on PEAP; Chuo Hoki Publishing Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2010. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.; Fleming, R.; Chenoweth, L.; Jeon, Y.; Stein-Parbury, J.; Brodaty, H. Validation of the environmental audit tool in both purpose-built and non-purpose-built dementia care settings. Australas. J. Ageing 2012, 31, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C. Auditing design for dementia. J. Dement. Care 2009, 17, 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, F.; Innes, A.; Dincarslan, O. Improving care home design for people with dementia. J. Care Serv. Manag. 2011, 5, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, R.; Bennett, K. Assessing the quality of environmental design of nursing homes for people with dementia: Development of a new tool: The Environmental Audit Tool-High Care. Australas. J. Ageing 2015, 34, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linney, J.A.; Arns, P.G.; Chinman, M.J.; Frank, J. Priorities in community residential care: A comparison of operators and mental health service consumers. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 1995, 19, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Barnes, S.; McKee, K.J.; Morgan, K.; Torrington, J.M.; Tregenza, P.R. Quality of life and building design in residential and nursing homes for older people. Ageing Soc. 2004, 24, 941–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, L.J.; Kane, R.A.; Degenholtz, H.B.; Miller, M.J.; Grant, L. Assessing and comparing physical environments for nursing home residents: Using new tools for greater research specificity. Gerontol 2006, 46, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, S.; Elf, M.; McKee, K.; Wijk, H. Assessing the physical environment of older people’s residential care facilities: Development of the Swedish version of the Sheffield Care Environment Assessment Matrix (S-SCEAM). BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People′s Republic of China. (2020, April 28). The National Standard – Guidelines of Classification and Accreditation for Long-term Care Organization (Trial Version) Released. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-04/28/content_5507024.htm (accessed on 30 December 2023)In Chinese.

- Kaup, M.L.; Calkins, M.P.; Davey, A.; Wrublowsky, R. The environmental audit screening evaluation: Establishing reliability and validity of an evidence-based design tool. Innov. Aging 2023, 7, igad039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Knol, D.L.; Stratford, P.W.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: A clarification of its content. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleiss, J.L.; Cohen, J. The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1973, 33, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrekar, J.N. Measures of interrater agreement. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E. Measurement reliability and agreement in psychiatry. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 1998, 7, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerin, E.; Chan, K.; Macfarlane, D.J.; Lee, K.; Lai, P. Objective assessment of walking environments in ultra-dense cities: Development and reliability of the Environment in Asia Scan Tool—Hong Kong version (EAST-HK). Health Place 2011, 17, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikora, T.J.; Bull, F.C.L.; Jamrozik, K.; Knuiman, M.; Giles-Corti, B.; Donovan, R.J. Developing a reliable audit instrument to measure the physical environment for physical activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 23, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D.; Auffrey, C.; Whitaker, R.C.; Burdette, H.L.; Colabianchi, N. Measuring physical environments of parks and playgrounds: EAPRS instrument development and inter-rater reliability. J. Phys. Act Health 2006, 3, S190–S207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).