Abstract

The seismic design philosophy based on resilience represents the latest development in structural seismic design theory and is currently the most advanced concept in the field of seismic design research. A building site serves as the foundation and environment for structures, and evaluating its seismic resilience is a crucial aspect of designing and assessing buildings’ seismic resilience. To meet the needs of evaluating building seismic resilience, the concept of seismic resilience for building sites is introduced in this paper. This evaluation is approached from three dimensions: seismic action, site seismic capacity, and site recovery capability. An indicator system for evaluating the seismic resilience of building sites is constructed using 23 key indicators that reflect the site’s seismic resilience. A seismic resilience evaluation model for building sites is established based on the TOPSIS model and the entropy method. The feasibility and rationality of the proposed evaluation method are demonstrated through application examples. The research findings in this paper provide a valuable reference for advancing the evaluation of both building seismic resilience and site seismic resilience.

1. Introduction

Throughout the long history of human society, cities have suffered greatly from the devastation of earthquakes. Many cities have been destroyed by seismic disasters, resulting in significant loss of life and extensive property damage. As a result, earthquake resistance and disaster prevention have become enduring concerns for human civilization. An important part of these losses is attributed to the severe damages incurred to buildings, infrastructure, and structures of the production sector [1].

The building site plays a pivotal role in the seismic damage sustained by structures, acting as both the foundation and the surrounding environment. Its importance is related to a range of critical factors, including geological conditions, topographical features, soil composition, and hydrological characteristics, all of which significantly influence a building’s seismic performance. In various seismic design codes, site classification serves as the foundation for seismic design, with specific seismic requirements established accordingly for different types of sites [2,3,4,5]. The current standards primarily classify sites based on indicators such as lithology, overlying soil thickness, soil shear wave velocity, standard penetration test (SPT) blow count, and undrained shear strength. These classifications are then used to determine seismic design coefficients, which represent the intensity of strong ground motion. The impact of the site on buildings during an earthquake includes not only strong ground motion but also hazards such as sand liquefaction, soft soil settlement, landslides, surface rupture, and tsunamis [6,7,8,9,10]. Studies on the 2011 Tōhoku and Christchurch earthquakes have shown that the reconstruction of buildings was delayed considerably due to site damage. This led to prolonged recovery times and affected practical driving performance [11,12,13,14,15]; therefore, it is essential to assess the suitability of building sites comprehensively.

Seismic resilience is the further refinement and development of performance-based seismic design, offering a newer and more comprehensive approach to urban and building seismic planning and design. The urgent need for urban and building seismic safety provides a vast space and great motivation for research in the field of seismic resilience. As early as 2009, the San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR) proposed a seismic resilience evaluation system for cities [16]. FEMA-P58 (Federal Emergency Management Agency) [2] is a seismic performance evaluation method for buildings proposed by FEMA, which uses indicators such as casualties, repair costs, and repair time to assess the seismic performance of structures. In 2013, ARUP Group developed the Resilience-based Earthquake Design Initiative for the Next Generation of Building (REDi™) framework, a rating system for building seismic resilience [17]. NIST released seismic resilience guidelines that establish performance objectives for buildings and infrastructure, promoting collaboration among stakeholders for enhanced resilience [18,19]. Furthermore, in 2020, United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) launched the “Resilient Cities” initiative, advocating for sustainable urban development and disaster risk reduction strategies on a global scale [20]. Researchers have followed the concepts of robustness, redundancy, resourcefulness, and rapidity to devise evaluation indicators for subsystems such as building structures [21,22,23,24], medical systems [25,26,27,28], and lifeline systems [29,30,31]. Several seismic resilience standards have also been subsequently established. Researchers have established evaluation frameworks and resilience assessment methods, driving the rapid development of seismic resilience research. It must be emphasized that both building structures and infrastructure are situated on sites, making site resilience a crucial component of overall resilience; however, current seismic resilience indicators and evaluation systems lack site resilience assessments, rendering the seismic resilience evaluation framework incomplete.

Building on the introduction of the concepts of site resilience and seismic resilience of building sites [32], an indicator system for evaluating site seismic resilience is systematically established in this paper. This system is based on the seismic response characteristics of building sites and the functional requirements that buildings impose on these sites. By integrating the entropy weight method and the TOPSIS method, a model for evaluating site seismic resilience is developed. Using this indicator system, the seismic resilience of 60 building sites in Beijing, China, is analyzed, with resilience values and classifications provided for each site. The findings of this study offer significant theoretical insights for advancing the evaluation of urban and building seismic resilience and provide valuable reference points for further exploration of site seismic resilience assessment.

2. The Concept and System of Seismic Resilience for Sites

2.1. Concept of Seismic Resilience for Sites

A site is a complex geological system composed of rock, soil, geological structures, groundwater, and other elements. An urban construction site refers to an area within a city’s boundaries. A site is defined as the location of an engineering group characterized by similar response spectrum features. The area of such a site is equivalent to that of industrial parks, residential areas, or natural villages, or it covers a planar area greater than 1.0 km² [5].

The seismic performance of a site is controlled by site conditions, which significantly impact seismic motion [33,34,35]. Site conditions typically include topography, geomorphology, soil composition, geological structures, hydrogeological conditions, and physical geological phenomena [36]. From a seismic perspective, when selecting a site for engineering construction, it is essential to choose sites or locations favorable for seismic resistance and to avoid unfavorable sites or locations. The impact of site conditions on seismic motion is the core content of site seismic performance evaluation.

It is crucial to emphasize that site seismic performance is an important aspect of evaluating site stability. In addition to seismic action, site stability is also affected by other geological processes, their evolution, and human engineering activities. Different engineering projects have different requirements for site stability based on their usage functions, leading to different demands for on-site seismic performance.

Resilience can be defined as the ability of a system to resist, absorb, recover from, and adapt to various disturbances. These disturbances can be natural or human-made, with varying implications across different academic disciplines [37]. In civil engineering, resilience primarily refers to the ability to maintain and restore original functions under various disturbances, including the ability to resist wind, explosions, floods, and earthquakes, as well as to restore these functions after such disturbances.

The original functions include wind resistance, explosion resistance, flood resistance, seismic performance, basic functions, and comprehensive functions. Basic functions refer to the necessary performance required to ensure the normal use, structural safety, and proper operation of equipment in civil engineering projects. Comprehensive functions refer to the ability to maintain basic functions while keeping the appearance and interior intact. The design requirements for these functions are based on the needs of the project. Recovery refers to the restoration of these functions after repairs.

According to the “Standard for Seismic Resilience Assessment of Buildings” (GB/T38591-2020) published by the Standards Press of China in 2020 [38], it defines the seismic resilience of buildings as the ability of a building to maintain and restore its original functions after a specified level of seismic action. This standard uses post-earthquake repair costs, repair time, and casualties caused by the earthquake as indicators to evaluate the seismic resilience of buildings; however, the standard only specifies seismic input and does not address the role of building sites in evaluating seismic resilience. Nevertheless, the seismic resilience of buildings is closely related to the seismic resilience of building sites, with the latter being an essential component of the former; therefore, evaluating the seismic resilience of buildings should begin with evaluating the seismic resilience of building sites.

Based on the above discussion, the seismic resilience of building sites is defined in this paper as the ability of a site to resist seismic damage and maintain and restore its original functions and environmental conditions after a specified level of seismic action. According to Bo et al. [32], site resilience can be defined as the ability of a site to maintain and restore its original functions and environmental conditions after being subjected to a certain intensity of geological processes and human engineering activities. Site resilience is an important indicator of the resilience of cities and engineering structures.

Since seismic resilience of sites primarily considers the ability to maintain and restore original functions and environmental conditions under seismic action, it is a critical indicator of site resilience. The site is both the supporting body for buildings and the medium through which seismic waves propagate. When subjected to a certain level of seismic action, the geotechnical body of the site may change, sometimes altering its original functions. Strong earthquakes may cause seismic geohazards, such as soil liquefaction, soft soil settlement, surface rupture, and slope instability, leading to foundation failure and the loss of original functions, ultimately resulting in severe damage to the superstructure. Additionally, earthquakes can trigger landslides, collapses, rockfalls, tsunamis, and lake surges, altering the original environment and functions of the site and damaging buildings; therefore, seismic performance is a critical factor in determining site resilience.

The original environment and functions of the site refer to the environmental conditions and site performance necessary to ensure the safety, stability, and proper operation of the building project, as required during site planning and design. Seismic action on the site can be understood as the dynamic action produced by seismic motion within the site, which is related not only to the characteristics of the seismic motion itself but also to the dynamic characteristics of the site. Considering the need for seismic resilience evaluation of buildings, the seismic action level adopted in this paper corresponds to a rare earthquake, i.e., an earthquake with a 2% probability of exceedance in 50 years.

Based on the above discussion, it is proposed in this paper that the evaluation of seismic resilience of building sites can be achieved by assessing the stability of the site under seismic action within a certain range and the recovery of the site’s original functions after the earthquake. The seismic resilience of building sites is influenced by multiple factors, with multiple indicators reflecting different aspects of site resilience; therefore, the evaluation of the seismic resilience of building sites can be approached as a multi-criteria comprehensive evaluation problem. There are many multi-criteria comprehensive evaluation methods [39,40,41]. In this paper, we explore the evaluation of seismic resilience of building sites using an integrated approach combining the TOPSIS model and entropy method.

2.2. Evaluation Indicator System

In mathematical terms, a multi-indicator comprehensive evaluation method requires determining the evaluation object and evaluation indicators and establishing an evaluation indicator system. The evaluation object (or goal) in this study is the seismic resilience of building sites. The evaluation indicators, in principle, include all the factors affecting the seismic resilience of building sites. The entire set of evaluation indicators across different hierarchical levels constitutes the evaluation indicator system. This system is an organic whole composed of multiple interrelated and interacting evaluation indicators structured in a certain hierarchy. The selection of evaluation indicators needs to focus on key factors and critical indicators, adhering to the principles of simplicity, independence, representativeness, and feasibility.

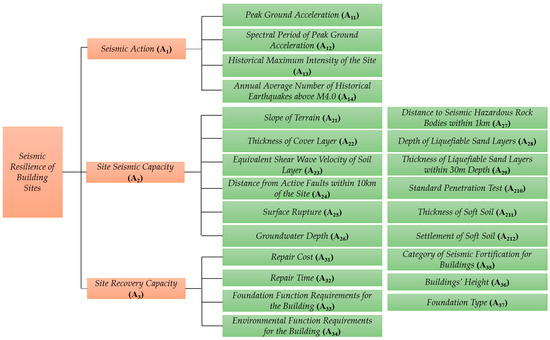

Following the requirements of the multi-indicator comprehensive evaluation method and based on the definition and connotation of seismic resilience of building sites, an evaluation indicator system is constructed consisting of three levels: the goal level, dimension level, and indicator level. As shown in Figure 1, the goal level is the seismic resilience of building sites (denoted as A). The dimension level includes seismic action (denoted as A1), seismic capacity of the site (denoted as A2), and recovery capability of the site (denoted as A3); therefore, in this study, we evaluate the seismic resilience of building sites from three dimensions: the potential seismic action the site may experience, the seismic capacity (seismic stability) under a certain level of seismic action, and the recovery capability of the site after experiencing seismic action.

Figure 1.

Building site seismic resilience indicator system.

Based on the characteristics and attributes of each dimension, as well as the principles for selecting evaluation indicators, several indicators are used to describe each dimension, forming the indicator level. As shown in Table 1, 23 indicators have been selected to represent these dimensions.

Table 1.

Seismic resilience indicator system and value requirements for building sites.

In this study, three indicators—Peak Ground Acceleration (PGA), Response Spectrum Characteristic Period (Tg), and Site Intensity—are employed to represent the effects of seismic motion on a site under the dimension of seismic action. The risk levels of these indicators can be set at exceedance probabilities of 2%, 10%, and 63% over 50 years. To align with the national standard GB/T38591-2020, this study adopts the PGA and Tg values corresponding to a 2% exceedance probability over 50 years. Research [33,34,35,36] has shown that the seismic resistance of a site is primarily governed by its seismic engineering geological conditions, including topography and geomorphology, soil and rock properties, active tectonics, groundwater, and seismic, geological hazards; therefore, in this study, we select the following 15 indicators to evaluate the site’s seismic resistance dimension: slope, elevation difference within 1000 m, soil and rock type, overburden thickness, equivalent shear wave velocity, site classification, distance from the active fault to the site, surface rupture, groundwater depth, distance from seismic hazardous rock masses within 1000 m to the site, depth of liquefiable sand layers, thickness of liquefiable sand layers within 30 m, standard penetration resistance of liquefiable sand layers, soft soil thickness, and soft soil settlement.

The evaluation of site recovery capability is more complex and involves a high degree of subjectivity. To simplify the problem, only four evaluation indicators are considered in this study: repair costs, repair time, building requirements for foundation functions, and building requirements for environmental functions.

The system of indicators and the corresponding criteria for evaluating the seismic resilience of building sites are presented in Table 1. All of these indicators can be obtained from site seismic safety evaluation reports and geotechnical engineering investigation reports.

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Methods

The resilience of a building site reflects its ability to resist and absorb stress and maintain and recover its original functions and site environment after being disturbed. In engineering practice, this ability needs to be evaluated so that it can be applied in urban and building resilience evaluation. There are many comprehensive evaluation methods used locally and internationally, and each method has its scope of application and advantages and disadvantages [43]. From the perspective of weight determination, the evaluation method mainly consists of two types: the weight that can be determined directly, including the Analytic Hierarchy Process, entropy method, and Rough Set Multi-Attribute Decision Making, and the weight that is determined indirectly, including the Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation, Grey Correlation Analysis, Material Element Analysis, TOPSIS model, and Catastrophe Progression Method. A single method or a combination of several methods is often used in the study of urban construction and disaster resilience evaluation [44,45,46,47,48]. The determination of indicator weights is key in resilience index system evaluation, and different weights for each indicator will lead to completely different evaluation results. The entropy method belongs to the objective weighting method, a commonly used method for determining weights, which can effectively eliminate subjective factor interference in determining the indicator weights and objectively reflect the evaluation object information. The advantage of the TOPSIS model is that it has no strict restrictions on the sample, and it can make fuller use of these original data. In this paper, a resilience evaluation model for building site seismic resilience is proposed by integrating the TOPSIS model and entropy value method, and the building site’s seismic resilience is evaluated through the model to obtain its seismic resilience grade.

3.1.1. TOPSIS Model

The TOPSIS model, proposed by Hwang. C.L and Yoon. K. in 1981 [49] has since been continuously improved by researchers to become a widely used multi-criteria (or attribute) decision-making analysis model for limited alternatives [50,51,52,53]. The idea comes from the discriminant problem in multivariate statistical analysis, and its basic principle is to assume the existence of an optimal solution among multiple solutions, which is called the ideal solution or optimal solution. Using multiple evaluation indicators for each solution, the distance between each solution and the ideal solution (optimal solution) is calculated, and its proximity to the ideal solution (optimal solution) is given based on this distance. The higher the proximity, the closer the solution is to the optimal solution. The proximity is used to rank or classify the solutions [54], providing a basis for solution selection. The seismic resilience of building sites reflects the ability to withstand seismic interference, which is affected by many indicators. If each site is taken as an evaluation object and several evaluation indicators are given for each site, the site’s resilience is defined in the range of [0,1], where 1 is an ideal solution theoretically; the closer the site is to the ideal solution, the higher the resilience is. Consequently, the proximity degree derived from the TOPSIS model can be utilized to evaluate the seismic resilience of building sites.

The primary computational steps of the TOPSIS model are outlined as follows:

- Step 1.

- Creating the initial matrix X

If m sites are evaluated and each site has n evaluation indicators, the distribution of the site set and indicator set of the TOPSIS model is M(M1, M2,…, Mm); N(N1, N2,…, Nn). If the value of the site Mi() under the indicator Nj() is , the initial matrix of multiple sites is

- Step 2.

- Data standardization processing, establishing the standard discriminant matrix Y

Due to the different dimensions and sizes of the indicators, in order to reflect the commonness of each indicator in the comprehensive evaluation, the extreme value method is used to obtain dimensionless and normalized indicators, and the standard discriminant matrix Y is given as follows:

For positive indicators

For negative indicators

) are, respectively, the maximum and minimum values of the jth indicator. After removing dimensions and normalizing,

- Step 3.

- Constructing the weighted decision matrix Z

Because there are differences between indicators for the seismic resilience of sites, a weighted decision matrix considering the weights of indicators is constructed on the basis of the standard discrimination matrix Y:

where is the weight of the jth indicator, . After research and comparison, the entropy weighting method, which highlights local differences, is used to determine the weights of each indicator.

- Step 4.

- Determining the positive ideal solution and the negative ideal solution for the jth indicator

In the TOPSIS model, the positive ideal solution and negative ideal solution are defined. The positive ideal solution, which is a set of data composed of the most advantageous indicators for evaluation results, is given by Equation (6). The negative ideal solution, which is a set of data composed of the most disadvantageous indicators for evaluation results, is given by Equation (7).

and represent the subscript of the positive indicator and the subscript of the negative indicator, respectively.

- Step 5.

- Determining the distance and to positive and negative ideal solutions on indicators of each site, and giving the proximity degree to positive ideal solutions

In the seismic resilience of building sites, a set of indicators is given for each site according to the indicator evaluation system. In actual evaluation, there is a distance that is expected to be close to the positive one between the set and the positive and negative ideal solutions. In this paper, the Euclidean distance is calculated, the distance to the positive ideal solution is determined with Equation (8), and the distance to the negative ideal solution is determined with Equation (9).

By using and , the proximity degree between the indicator set of each site and the positive ideal solution set can be calculated using Equations (1)–(9), which is defined as the proximity degree of building sites.

- Step 6.

- Evaluating the seismic resilience and rank division of building sites by the proximity degree

The proximity degree represents the close degree between the indicator set and the positive ideal solution set; the value range is (0, 1), which means the larger the value, the closer the indicator set is to the positive ideal solution set, and the higher the seismic resilience, and vice versa. It should be emphasized that seismic resilience, such as seismic intensity, is not a measurable physical quantity but a relative standard to measure the seismic performance of the site; therefore, the site proximity degree is used to evaluate the seismic resilience of building sites. In order to be consistent with the national standard GB/T38591-2020, the seismic resilience of building sites is divided into three parts, shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Seismic resilience division of building sites.

3.1.2. Entropy Method

The TOPSIS model needs to give the weight of each indicator. After research and comparison, the entropy weighting method, which highlights local differences, is adopted to determine the weight of each indicator. Entropy is a thermodynamic and statistical physical concept. In the 1940s, C.E. Shannon, an American mathematician, electrical engineer, and founder of information theory, introduced the concept of entropy into communication engineering and proposed the concept of information entropy. Information entropy is a measure of information. Entropy reflects the amount of information on different signals in the system, also reflecting the importance of different signals. In multi-indicator synthesis, the concept of entropy is used to reflect the importance of different indicators in evaluation, and the entropy weighting method is formed. It is an objective weighting method with no interference from human factors, objectively reflecting the importance of each indicator in the comprehensive evaluation system. The steps for calculating indicator weights by the entropy method are as follows:

- Step 1.

- Creating the initial matrix

The initial matrix is constructed according to Equation (1).

- Step 2.

- Data standardization processing

Initial matrix data are processed according to Equations (3) and (4), and Equation (2) is obtained.

- Step 3.

- Calculating the proportion of the jth indicator in the ith site

- Step 4.

- Calculating the information entropy of the jth indicator

, according to Equation (11); when , , it does not meet the mathematical requirements of Equation (12). In this situation, coordinate translation can be used to process these data to meet the mathematical requirements [55,56,57]. When , .

- Step 5.

- Calculating the weight of the jth indicator

3.2. Data

In order to investigate the applicability and feasibility of the proposed method, 60 building sites in the Beijing area are selected as examples for analysis. It should be noted that because soft soil does not exist in Beijing, and there is no dangerous rock mass within 1 km, the A27, A211, and A212 are excluded from the actual calculation.

3.2.1. Basic Information of Sites

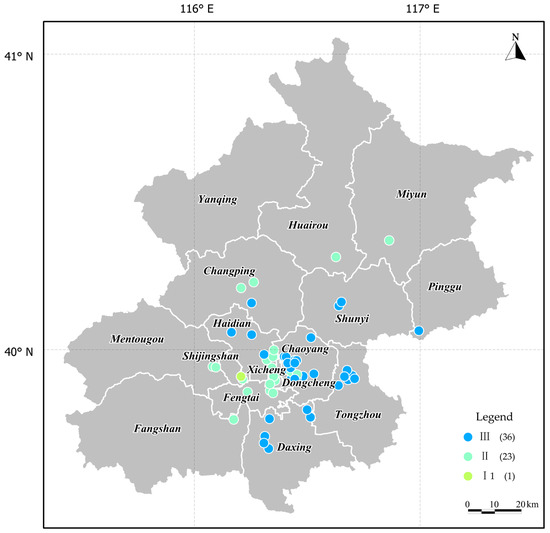

We selected 60 representative building sites as evaluation subjects, with their locations shown in Figure 1. The information for these sites was obtained from seismic safety evaluation reports and geotechnical investigation reports. As an example, we provide the seismic resilience indicator values for five of these sites, as shown in Table 3. Figure 2 shows the distribution of sites. Building sites in Beijing are mainly of type II and type III (Figure 3). Type II sites are mostly concentrated in the western part of Beijing, such as Xicheng District, Shijingshan District, Fengtai District, and the eastern part of Mentougou District, while type III sites are mostly concentrated in the eastern part of Beijing, such as Chaoyang District, Dongcheng District, Tongzhou District, and the northern part of Daxing District.

Table 3.

Basic information for five building sites.

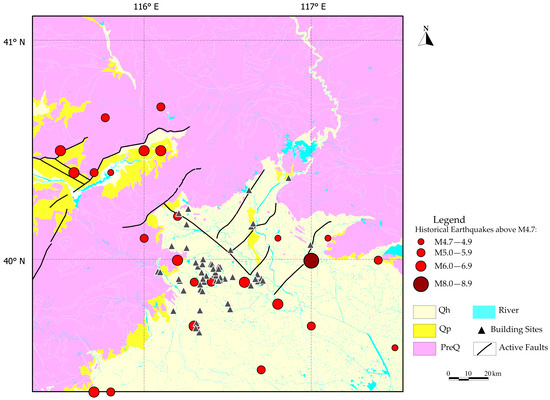

Figure 2.

Maps of 60 building sites.

Figure 3.

Category distribution map of 60 building sites in Beijing (The numbers in parentheses represent the number of building sites).

3.2.2. Creating the Initial Matrix

According to the seismic resilience evaluation system for building sites (Table 1), indicator data are extracted, and the initial matrix is established; some site data extracted are listed in Table 4. Equations (3) and (4) are used to standardize data from the 60 building sites listed in Table 4, and the standard discrimination matrix is given. Using the entropy method, the weights of each indicator are given by Equations (11)–(13), detailed in the Supplementary Materials. The results are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Site initial matrix data and indicator weights.

3.2.3. Calculating the Proximity Degree of Sites

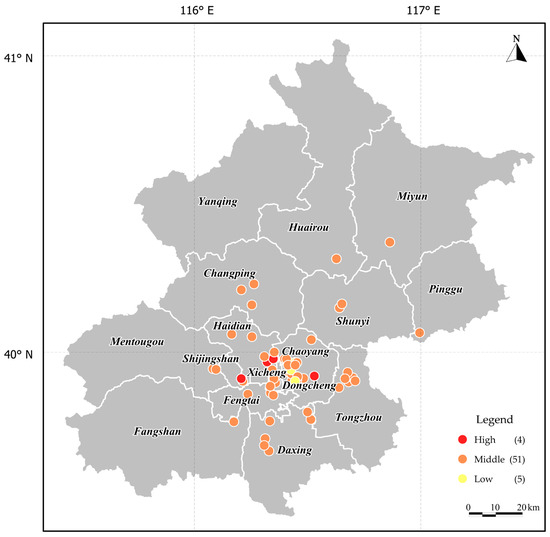

According to data provided in Table 4 and the weight of indicators, the TOPSIS model can be used to calculate the proximity degree between the indicator set and the positive ideal solution set of 60 sites from Equations (3)–(10). Specifically, the site proximity degree is defined. The results are listed in Table 5. The seismic resilience of sites is ranked by the site proximity degree, and the resilience levels of sites are divided according to the division standards in Table 2. The results are listed in Table 5, and the proximity distribution of sites is shown in Figure 3.

Table 5.

Proximity degree and resilience rank of building sites.

4. Discussion

Based on the analysis of Table 4, it can be seen that, in the criteria layer, the seismic capacity of sites has the greatest weight, indicating that the seismic capacity of sites has the greatest influence on the sites’ seismic resilience. In the 20 indicators, the Peak Ground Acceleration, the highest intensity of influence on the site, and equivalent shear wave velocity of the soil layer have the greater influence on building sites. SPT, surface rupture, category of seismic fortification for buildings, spectral period, and average annual occurrence times of earthquakes above M4.0 are the second. The foundation function requirements for buildings, height, and thickness of liquefiable sand layers within 30 m depth are the least. The above results are basically consistent with the common understanding within the engineering field at present, indicating that the method proposed in this paper can be applied to the evaluation of seismic resilience of building sites and is practically applicable to the Beijing area.

It can also be seen from Table 5 that the four sites with high resilience are characterized by no geological disasters such as sand liquefaction, shallow thickness of cover layer, weak fault activity, and little influence of groundwater; therefore, the resilience value is higher. The five sites with low resilience are characterized by severe sand liquefaction, deep thickness of cover layer, and high historical seismic intensity. In general, the site with low resilience has strong seismic activity, poor site conditions, and serious seismic geological disasters. After an earthquake, the basic functions of the site are restored slowly. The results align with the definition of the seismic resilience of building sites in this paper.

As can be seen from Figure 4, the sites with high resilience are in Shijingshan District, the southern part of Haidian District, and the eastern part of Chaoyang District, while the sites with low resilience are located at the border of Chaoyang District and Dongcheng District, which is closely related to site conditions. According to the analysis in Table 5, although the level of site resilience does not exactly correspond to the site category, the trend is that the sites with low resilience are all type III, which is consistent with the usual recognition. The reason why the resilience of the site is not completely consistent with the site category is that the resilience of the building site is determined by more than 20 indicators, including seismic action, site seismic capacity, and recovery capability, while the category of the site is determined by the double indicators including the thickness of the site covering layer and equivalent shear wave velocity of the soil layer. The selection of evaluation indicators needs further exploration, especially the site recovery ability after the earthquake, which has many influencing factors. The entropy method is objective with no interference from human factors, and can objectively reflect the importance of each indicator in the comprehensive evaluation system; however, the determination of the weight of each indicator by using the entropy method is affected by the number and type of sites, so it is necessary to explore further the number and type of sites that must be satisfied by the stable weight of each indicator. In summary, the study of the seismic resilience evaluation of building sites is still in the initial stage, and some problems need to be further explored. It can be predicted that the study of site seismic resilience will become a rich field in geotechnical engineering seismic research in the future. This paper is only a preliminary exploration of this aspect.

Figure 4.

Resilience distribution map of 60 building sites in Beijing (The numbers in parentheses represent the number of building sites).

5. Conclusions

The seismic resilience of sites is an important part of the seismic resilience of buildings. The seismic resilience of building sites and their evaluation is a brand new concept and, thus, an important research direction in the seismic field of geotechnical engineering. The purpose of evaluating the seismic resilience of sites is to facilitate the assessment of the seismic resilience of buildings and compensate for the deficiencies in the evaluation of the seismic resilience of buildings regarding the influence of the site; it further enhances the evaluation criteria for assessing the seismic resilience of buildings. In this paper, the seismic resilience of building sites mainly refers to the ability of the site to withstand earthquake damage and recover after an earthquake. Therefore, 23 indicators are used to evaluate the seismic resilience of the building sites from three dimensions: the possible seismic action, the site seismic capacity, and the site recovery capability. The selection of evaluation indicators is a problem that needs further in-depth research, especially the ability of the site to recover after experiencing seismic action, which is affected by many factors.

The entropy method is an objective weighting method unaffected by human factors, which can objectively reflect the importance of each evaluation indicator in the comprehensive evaluation system. However, determining the weights of each evaluation indicator in the site using the entropy method is influenced by the number and type of sites, and further exploration is needed to determine the number and type of sites required for each evaluation index to have a stable weight.

In addition to the determination of weights, the choice of evaluation method is also very important. In subsequent research, the suitability and rationality of various mathematical methods for application to the evaluation of site resilience will be further argued and verified. Based on the characteristics of site seismic resilience evaluation, new comprehensive mathematical evaluation methods will be explored. With the increase in engineering site investigation reports and seismic safety evaluation reports, statistical data on seismic resilience evaluation of building sites in Beijing will be enriched in the future, providing more scientific and comprehensive seismic resilience evaluation for building sites in Beijing.

In summary, the research on the seismic resilience evaluation of building sites is still in its infancy, and there are still some issues that need further discussion. It can be predicted that, in the future, this will become a rich field of research in seismic engineering. This paper is only a preliminary exploration in this regard.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings14113667/s1, Table S1. Normalized Data; Table S2. Proportions; Table S3. Weights.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Y.W., D.P. and J.B.; Software, D.P.; Validation, T.B.; Formal analysis, Y.W.; Data curation, Y.W., D.P., T.B. and X.Z.; Writing—original draft, Y.W.; Writing—review & editing, Y.W. and D.P.; Project administration, J.B.; Funding acquisition, J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Key Science and Technology Project of Ministry of Emergency Managementof the People’s Republic of China (Grant No. 2024EMST040408), Scientific Research Fund of Institute of Engineering Mechanics, China Earthquake Administration: 2020EEEVL0201.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xinlong Zhao was employed by the company Transport Engineering Branch of China Railway Sixth Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Verdugo, R. Seismic site classification. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 124, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEMA. Seismic Performance Assessment of Buildings; Volume 1—Methodology; Federal Emergency Management Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Civil Engineers. Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2022.

- BS EN 1998-1:2004; Price, C. Eurocode 8: Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance-Part 1: General Rules, Seismic Actions and Rules for Buildings. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2005; Volume 10.

- GB 50011-2010; National Standard of the People’s Republic of China. Code for Seismic Design of Buildings. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Bray, J.D.; Dashti, S. Liquefaction-induced building movements. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2014, 12, 1129–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, K.; Hamada, J.; Onimaru, S.; Higashino, M. Seismic behavior of piled raft with ground improvement supporting a base-isolated building on soft ground in Tokyo. Soils Found. 2012, 52, 1000–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasowski, J.; Keefer, D.K.; Lee, C.T. Toward the next generation of research on earthquake-induced landslides: Current issues and future challenges. Eng. Geol. 2011, 122, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.D. Improving the Seismic Performance of Existing Buildings and Other Structures—Designing buildings to accommodate earthquake surface fault rupture. In Proceedings of the American Society of Civil Engineers ATC and SEI Conference on Improving the Seismic Performance of Existing Buildings and Other Structures, San Francisco, CA, USA, 9–11 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Paulik, R.; Gusman, A.; Williams, J.H.; Pratama, G.M.; Lin, S.-L.; Prawirabhakti, A.; Sulendra, K.; Zachari, M.Y.; Fortuna, Z.E.D.; Layuk, N.B.P.; et al. Tsunami hazard and built environment damage observations from Palu City after the 28 September 2018 Sulawesi earthquake and tsunami. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2019, 176, 3305–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokimatsu, K.; Tamura, S.; Suzuki, H.; Katsumata, K. Building damage associated with geotechnical problems in the 2011 Tohoku Pacific Earthquake. Soils Found. 2012, 52, 956–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshimura, S.; Hayashi, S.; Gokon, H. The impact of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake tsunami disaster and implications to the reconstruction. Soils Found. 2014, 54, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyrou, E.; Tasiopoulou, P.; Bal, İ.E.; Gazetas, G. Ground motions versus geotechnical and structural damage in the February 2011 Christchurch earthquake. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2011, 82, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisio, M.R.; Pawson, E. Building resilience through post-disaster community projects: Responses to the 2010 and 2011 Christchurch earthquakes and 2011 Tōhoku tsunami. Australas. J. Disaster Trauma Stud. 2016, 20, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Frangopol, D.M. Performance-based seismic assessment of conventional and base-isolated steel buildings including environmental impact and resilience. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2016, 45, 739–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPUR. The Resilience City: Defining What San Francisco Needs from Its Seismic Mitigation Policies; San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Almufti, I.; Willford, M. REDi Rating System: Resilience-Based Earthquake Design Initiative for the Next Generation of Buildings Version1.0; Arup: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams, L.; Van Pay, L.; Sattar, S.; Johnson, K.; McCabe, S. NIST-FEMA Post-Earthquake Functional Recovery Workshop Report; US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2021.

- Beyzaei, C.; Johnson, K.; Nikolaou, S.; Sattar, S.; Dukes, J.; Saadat, Y. NIST Transportation Systems and Functional Recovery Workshop Report; US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023.

- Helen, C. United Nations Human Settlements Programme—UN-Habitat. In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2021; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 234–240. [Google Scholar]

- Cubrinovski, M.; Bradley, B.; Wotherspoon, L.; Green, R.; Bray, J.; Wood, C.; Pender, M.; Allen, J.; Bradshaw, A.; Rix, G.; et al. Geotechnical aspects of the 22 February 2011 Christchurch earthquake. Bull. New Zealand Soc. Earthq. Eng. 2011, 44, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murao, O. Recovery curves for permanent houses after the 2011 great east Japan earthquake. In Proceedings of the 16th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Tokyo, Japan, 9 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kosič, M.; Dolšek, M.; Fajfar, P. Pushover-based risk assessment method: A practical tool for risk assessment of building structures. In Proceedings of the 16th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Santiago, Chile, 9–13 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Snoj, J.; Dolšek, M. Expected economic losses due to earthquakes in the case of traditional and modern masonry buildings. In Proceedings of the 16th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering (16WCEE), Santiago, Chile, 9–13 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cimellaro, G.P.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Bruneau, M. Seismic resilience of a hospital system. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2010, 6, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimellaro, G.P.; Piqué, M. Resilience of a hospital emergency department under seismic event. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2016, 19, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimellaro, G.P.; Malavisi, M.; Mahin, S. Using discrete event simulation models to evaluate resilience of an emergency department. J. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 21, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, S.; Zamani Noori, A.; Cimellaro, G.P. Cascading hazard analysis of a hospital building. J. Struct. Eng. 2017, 143, 04017100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Dueñas-Osorio, L. An approach to design interface topologies across interdependent urban infrastructure systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2011, 96, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondini, F.; Capacci, L.; Titi, A. Life-cycle resilience of deteriorating bridge networks under earthquake scenarios. Network 2017, 5, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoni, A.; Borlera, S.L.; Malandrino, F.; Cimellaro, G.P. Seismic vulnerability and resilience assessment of urban telecommunication networks. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Bo, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Y. Concept of Site Resilience and Discussion on Relevant Issues. World Earthq. Eng. 2022, 38, 1–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. The soil conditions affect the seismic loads on the building. In Collected Reports on Seismic Engineering from the Institute of Engineering Mechanics; Chinese Academy of Sciences; China Science Publishing & Media Ltd.: Beijing, China, 1965; pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Sun, P.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, Q. Effects of Site Conditions on Earthquake Damage and Ground Motion. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Dyn. 1980, 35–41. Trial Publication 1.(In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bo, J.; Li, X.; Li, S. Some Progress of Study on the Effect of Site Conditions on Ground Motion. World Earthq. Eng. 2003, 19, 11–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bo, J.; Li, Q.; Qi, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y. Research Progress and Discussion of Site Condition Effect on Ground Motion and Earthquake Damage. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 2021, 51, 1295–1305. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bo, J.; Duan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y. Meaning Analysis and Application of “Resilience”. World Earthq. Eng. 2003, 39, 38–48. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- GB/T38591-2020; Standard for seismic resilience assessment of buildings. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Clarke, A. Evaluation Research: An Introduction to Principles, Methods and Practice; Sage: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.L. Comparison of weights in TOPSIS models. Math. Comput. Model. 2004, 40, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Xiu, C.; Bai, L.; Zhong, Y.; Wei, Y. Comprehensive evaluation of urban resilience based on the perspective of landscape pattern: A case study of Shenyang city. Cities 2020, 104, 102722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Standards of the People’s Republic of China. Specification for Geotechnical Investigation in Soft Clay Area; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; He, N. Study on Classification and Applicability of Comprehensive Evaluation Methods. Stat. Decis. 2022, 6, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, J.; Liu, W.; Han, L. Research on Evaluation Index System of Chinese City Safety Resilience Based on Delphi Method and Cloud Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Hu, Z.; Shu, R. Study on Substation Seismic Resilience Evaluation Index and Resilience Matrix. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 562, 012052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, J.; Xu, J.; Zhe, O. Evaluation of the moderate earthquake resilience of counties in China based on a three-stage DEA model. Nat. Hazards 2018, 91, 587–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, J.; Dun, Z.; Cheng, J.; Li, H.; Dun, Z. Resilience Evaluation of High-Speed Railway Subgrade Construction Systems in Goaf Sites. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, D. Research on Resilience Evaluation of Green Building Supply Chain Based on ANP-Fuzzy Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications, a State-of-the-Art Survey; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y. The Improved Method for TOPSIS in Comprehensive Evaluation. Math. Pract. Theory 2002, 32, 572–575. [Google Scholar]

- Behzadian, M.; Otaghsara, S.K.; Yazdani, M.; Ignatius, J. A state-of the-art survey of TOPSIS applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 13051–13069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhai, D.; Zhang, S.; Hu, D. Application of Improved TOPSIS Comprehensive Evaluation Model to Optimization of River Regulation Schemes. J. Hohai Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2013, 41, 222–228. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chu, T.C.; Lin, Y.C. An interval arithmetic based fuzzy TOPSIS model. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 10870–10876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, P.; Li, W.; Guo, Y. Comprehensive Evaluation Theory and Methods; Economy & Management Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2019; pp. 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Tian, D.; Yan, F. Effectiveness of entropy weight method in decision-making. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 3564835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekinezhad, H.; Sepehri, M.; Pham, Q.B.; Hosseini, S.Z.; Meshram, S.G.; Vojtek, M.; Vojteková, J. Application of entropy weighting method for urban flood hazard mapping. Acta Geophys. 2021, 69, 841–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudabadi, R.; Mousavi, S.M.; Sharifi, E. An integrated weighting and ranking model based on entropy, DEA and PCA considering two aggregation approaches for resilient supplier selection problem. J. Comput. Sci. 2020, 40, 101074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).