Abstract

The cracking of link slabs in jointless bridges presents significant challenges due to the complexity of their stress conditions. This study focused on analyzing the transverse stresses in link slabs of jointless steel–concrete composite bridges. Utilizing linear elasticity theory and partial differential equations of plates, the deflection and stress distribution functions for the link slabs were determined. The validity of these analytical solutions was confirmed through comparisons with finite element models and load tests. Results from both the load tests and the finite element model indicate that the upper face of the girder end link slabs experiences maximum tensile stresses in both transverse and longitudinal directions. The stress values obtained from the analytical method align well with these results, showing that the total stress, when considering transverse stresses, reaches 107% of the longitudinal stresses alone. Furthermore, a 40% reduction in longitudinal girder spacing or a 50% increase in girder end length can lead to link slab stresses of 128% and 145% of the longitudinal stresses, respectively. This finding suggests that even loads lower than those designed based solely on longitudinal stresses can result in cracking. Therefore, it is recommended that transverse stresses be considered in the design of link slabs for jointless bridges. Relying solely on conventional longitudinal stress analyses may underestimate actual stress conditions and contribute to the formation of cracks.

1. Introduction

Steel–concrete composite bridges have been widely adopted since the 20th century due to their effective utilization of the mechanical properties of both materials, particularly in small to medium-span, multi-span, simply supported girder bridges [1,2]. Traditional, multi-span, simply supported girder bridges require expansion joints to accommodate bridge deck deformation caused by temperature fluctuations, shrinkage, creep, and vehicle loads. These joints also serve to meet essential bridge requirements, including waterproofing, smoothness, wear resistance, and noise reduction [3,4]. However, in practice, these joints are susceptible to issues such as debris accumulation, water erosion, and corrosion from snow-melting agents, which can lead to a significantly reduced service life and increased maintenance costs [5,6]. Jointless bridges with link slabs connecting adjacent spans have been developed since the 1930s, addressing many drawbacks of expansion joints [7,8,9]. A field investigation by Alampalli and Yannotti demonstrated that jointless bridges exhibit a superior performance compared to those with expansion joints [10].

However, due to mechanical complexities, unclear force properties, and challenges in ensuring construction quality, cracking frequently occurs in link slabs. This can lead to additional issues, such as bridge deck leakage and corrosion of the reinforcing steel. Ulku et al. conducted field inspections on the link slabs of eight bridges and identified full-depth cracking at the centerline of all the link slabs [11]. Liu et al. investigated 75 simply supported girder bridges with link slabs and found that 26.7% exhibited cracking in the link slabs [12].

Utilizing materials with superior mechanical properties is an effective strategy to prevent cracking in link slabs. Ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) is particularly suitable for manufacturing link slabs due to its high strength and tensile capacity [13]. Graybeal presented a case study in 2013 that involved repairing a damaged joint using cast-in-place UHPC link slabs [14]. In 2017, the New York State Department of Transportation issued design guidelines for UHPC link slabs. Based on these guidelines, Tan et al. designed and constructed link slabs with low-shrinkage, high-early-strength UHPC for a bridge with damaged joints. Performance monitoring over two years demonstrated that the slabs met all structural stress requirements [15]. Additionally, Lin et al. conducted model tests to evaluate the load–deflection–cracking behavior of UHPC link slabs, finding a 17% increase in load-bearing capacity and a 57% reduction in deflection compared to normal concrete (NC) link slabs [16]. This indicates the significant potential of UHPC in link slab applications. However, research on UHPC remains limited, with only a few codes and design guidelines currently available [13,17].

Accurately calculating the stress distribution under a load is essential for link slabs made from any material, to ensure they meet strength requirements for all operating conditions. Numerous studies have investigated the force properties, load types, and force mechanisms of link slabs. The stiffness of the link slab, which primarily bears the bending load, is significantly lower than that of the main beam. In light of this, Caner and Zia proposed a simplified calculation model to analyze the mechanical performance of link slabs without considering their influence on the simply supported beam [18]. Wing and Kowalsky conducted monitoring and load tests on a jointless bridge with link slabs, validating Caner’s test procedure [19]. Au et al. conducted experimental and load tests on link slabs, enhancing Caner’s theory by incorporating the compatibility of displacements between the link slab and the supporting beams below [20]. Okeil and ElSafty analyzed the structural parameters of the link slab, employing a modified three-moment equation to assess its bending resistance and deriving stress expressions for the link slab under two commonly used bearing types [21]. El-Safty and Okeil further utilized the three-moment equation method to evaluate the mechanical performance and service life of the link slab [22]. Ding et al. proposed a simply supported beam model with a boundary rotation spring to simulate simply supported beam bridges with link slabs [23]. They used the stiffness of the boundary rotation spring to simulate the effect of the link slab on the main beam. Gergess et al. investigated the mechanical behavior of the link slab under dead and live loads, providing deformation and stress data for various support configurations [24]. They presented a numerical solution for the link slab and suggested ways to optimize the design [25,26]. Wang et al. derived a force calculation formula for the link slab based on linear theory [27], demonstrating that upward girder ends and the tensile effect, along with girder end rotation, are primary contributors to link slab failure. Zhang et al. proposed a nonlinear analysis model based on Ding’s boundary rotation model to evaluate crack depth and analyze the stress in steel reinforcement within link slabs [28].

In the aforementioned studies, the stress analysis theory of link slabs was based on beam structure theory, which only considered longitudinal stress and deformation and ignored transverse stress, in order to simplify engineering design calculations. However, in real-world bridge structures, link slabs are subjected to complex states of stress, which can lead to significant stresses in both the longitudinal and transverse directions. Liu et al. investigated 75 bridges with link slabs and found that due to the more complex stresses experienced in actual bridge structures, link slabs still developed cracks, with some even developing grid-like cracks in both longitudinal and transverse directions [12]. Moreover, in bridges without joints, the wide link slab often causes deformation in the transverse direction. The bi-directional stresses in the link slab during loading cannot be accurately analyzed using the simplified beam structure theory, which neglects the effect of transverse stresses. As a result, the simplified theory leads to unsafe crack resistance results, causing cracking to occur earlier than the design load. In the practical application of bridges, the cracking of link slabs is mainly attributed to the bending moment effect caused by the rotation of the girder ends, which results in excessive tensile stresses on the upper surface of the link slabs. The compression deformation and shear deformation of the link slab in the thickness direction are small, so the link slab can be analyzed according to the plate theory.

This study aimed to address the problem of transverse stresses in link slabs. A novel analysis method is proposed for link slabs based on the partial differential equations (PDEs) of plates. The proposed analysis method was verified through load tests on a bridge equipped with UHPC link slabs and a finite element model, and the results aligned well with the load test results and FEM. On that basis, this study identified the locations on the link slab that were most susceptible to transverse stresses and investigated how the width and thickness of the link slab, as well as the spacing of the main girders, affected transverse stresses in the link slab. These findings provide valuable insights for optimizing the design of such bridges.

2. Analytical Theory of Link Slab Stress

2.1. Mechanical Model of Link Slabs

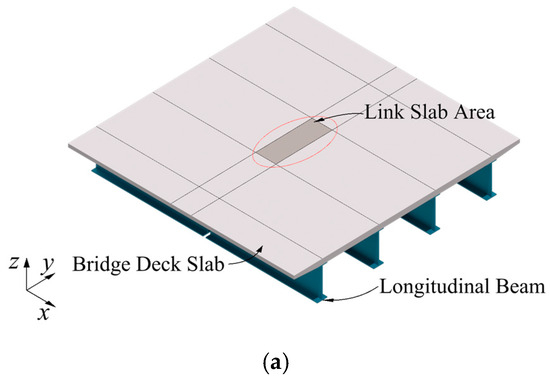

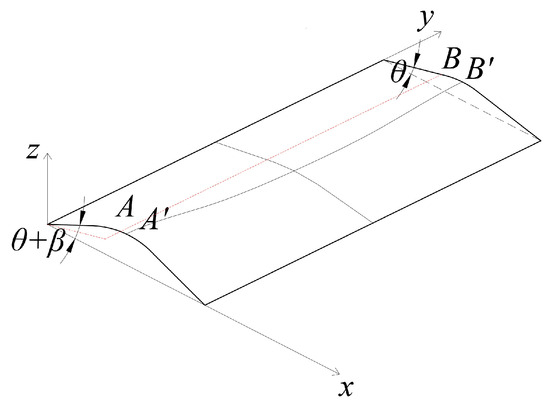

The link slabs are located at the ends of the longitudinal girders of the two adjacent spans, as shown in Figure 1a, subjected to bending due to the rotation of the longitudinal girder ends, which is the main cause of cracking of the link slabs. Since a link slab is supported by the longitudinal girder discretely along the transverse direction, the bending moment in the link slab is also non-uniform along the transverse bridge direction. Figure 1b shows the deflection of the link slab when the end of the longitudinal girder is rotated. In the longitudinal direction, the deflection curve of the link slab at the longitudinal girder is shown by the green curve in Figure 1b, in which the edge OA is driven to rotate by the longitudinal girder (the displacement in the vertical direction is mainly considered, so the influence of the link slab debonding can be neglected), and the deformation mainly occurs in the edge AA′. The deflection curve of the link slab at the middle position of the adjacent longitudinal girder is shown by the red curve in Figure 1b, and since it is not constrained by the longitudinal girder, the deformation can be uniformly distributed on the whole link slab. In the transverse direction, the link slabs exhibit deflection curves due to the inconsistency of the longitudinal deflection, as illustrated in Figure 1b by the blue curve. The transverse deflection curve of the link slab is analogous to that of a beam with fixed supports at both ends under symmetrical loading conditions, as the link slab is continuous along the transverse direction. Consequently, for the link slab at the non-side girder, a negative moment zone will be present at both ends of the link slab in the transverse direction. This will result in transverse tensile stresses on the upper surface of the link slab.

Figure 1.

Partial diagram of the structure: (a) whole; (b) partial.

In order to consider the effect of transverse stresses on the link slab, the mechanical model used for the analysis will be developed below based on the boundary conditions of the link slab. The longitudinal girders and end crossbeams are used to divide the link slab as an isolated region for analysis. This region has fixed boundaries at both longitudinal girders and end crossbeams, and the symmetric line A′B′ is the symmetric boundary under symmetric loading. Nevertheless, it is challenging to devise a universal solution for the deflection function that fulfills the specifications for a three-sided fixed support.

According to the above analysis, the link slab will exhibit a positive and negative bending moment area in the transverse direction. The zero moment position can be used as an alternative simple support boundary with zero moment and non-zero shear. In this way, a generalized solution of the deflection function can be established that meets the boundary conditions and can be solved. The distribution of positive and negative moment zones is only related to the type of load and its location of action. The bending moment distribution of the link slab after rotation at the girder end cannot be obtained directly, and the bending moment distribution of the fixed beam under a distributed load is used here as an approximation, which is a more unfavorable situation for the link slab.

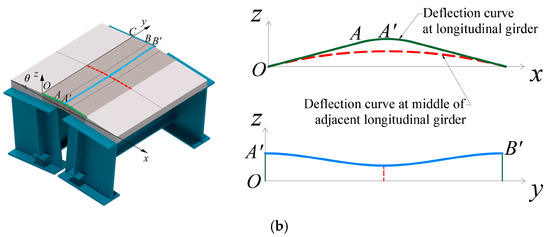

Thus, the process of analyzing the link slab is as follows. First, the deflection function of the positive moment zone of the link slab will be established, and then the deflection and stress in the negative moment zone will be analyzed based on the deflection in the positive moment zone. Based on the above analysis, the structural diagram of the positive moment region of the link slab was drawn up, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structural diagram of the link slab.

In the figure, DEFG is the entire link slab area, DG and EF are the longitudinal girder locations, and the longitudinal girder spacing is b′. OA and CB are the simple support boundaries, located in the zero moment position of the transverse bridge direction of the link slab, with the length a. The areas without girder support are denoted by AA’ and BB’, while A’B’ represents the line of symmetry between the two adjacent spans of the link slab. OC is the fixed boundary of the link slab at the end crossbeam, the length of which is the width of the positive moment zone b.

Based on these considerations, we propose the following assumptions:

- (1)

- Neglect the down deformation of the steel longitudinal girder and end crossbeam;

- (2)

- Neglect the shearing force and slip between the concrete and longitudinal girders;

- (3)

- Neglecting longitudinal displacement when the longitudinal girders rotate around the bearing.

2.2. Deflection Function of the Link Slab under Identical Steel Beam Rotation

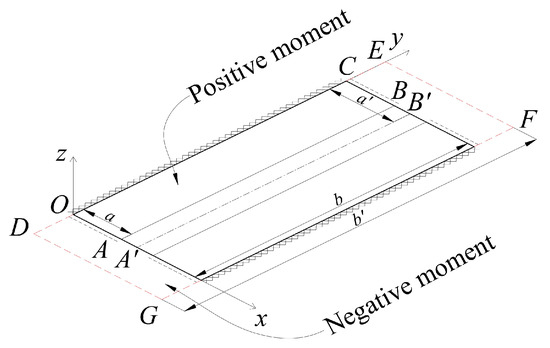

Firstly, it is assumed that the two adjacent longitudinal girders have the same rotation angle, which is a special case but helpful for building the analytical model, despite minor differences that may exist in the actual structure. Girders with the same rotation angle, which is more general case, will also be discussed in the later section. The structural diagram of the simplified link plate with identical rotation angles is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Diagram of link slabs at identical rotation angles.

Due to the existence of the unsupported area, the calculation can only use the edge AB as the actual calculation boundary. The first-order derivative of the rotation angle along the longitudinal bridge direction of the link slabs at the original boundary edge A’B’ without antisymmetric internal forces is 0. Moreover, the width of the area without steel beam support is small when compared with the total width of the area, so the actual calculation of the increment of the rotation angle at the boundary edge is tiny. However, as the edge of the link slab moves closer to the steel longitudinal girder, the deflection constraint from the beam becomes more assertive, making it less compliant with the symmetry boundary condition. Therefore, the calculation only considers the midline of the link slab as the symmetric boundary condition since it is farthest from the steel stringer constraint and closest to the symmetric boundary condition.

The deflection function for the region can be derived by satisfying the following differential equation of the elastic surface [29]:

The boundary condition can be expressed as follows, based on the boundary simplification:

The deflection function can be obtained using the single trigonometric series solution method based on the boundary conditions at y = 0 and y = b and adding the primary term of the girder end rotation about x to the equation. The deflection function references the Kirchhoff–Love plate theory with the addition of a term for the rotation of the girder end. The expression is as follows [29]:

The general solution of the partial differential equation satisfying all the boundary conditions and the plate is as follows:

Furthermore, the deflection function should also satisfy the following stress boundary conditions:

In Equations (9) and (10), is the thickness of the link slab. Substitute the deflection function into all the boundary conditions to solve the undetermined coefficients and solve each coefficient. Let α represent the following:

After solving the above, we obtain , and the implicit series expression for is as follows:

Furthermore, we can derive the expressions of , , and as follows:

It is important to note that, to ensure that the above boundary conditions are met even when the actual number of stages is finite, a correction factor should be applied to the coefficients , , and . For example, when the actual number of stages is n, the correction factor is as follows:

The final expression for the series of the deflection function is given below:

The range of values of the independent variable x in the deflection function obtained from the solution is , the rotation angle at the symmetric line is 0, and the longitudinal bridge direction rotation angle is considered to vary in a uniform manner in the unsupported region.

in the region of the unsupported area can be determined from , .

This equation is the deflection function of the link slab at the end of the longitudinal girder. The terms and in this equation show that the deflection and stress of the link slabs at the end of the steel girder are related to the length of the steel girder from the support to the end and the spacing between the two adjacent main girders.

2.3. Deflection Function of Link Slabs for Different Steel Beam Rotations

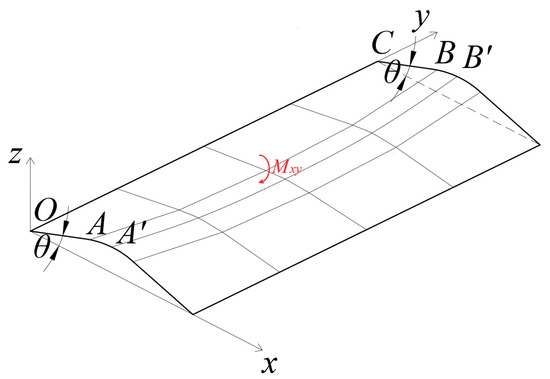

The deflection function given by Equation (18) comprises two terms: the first represents the deflection of the link slabs due to the girder end rotation, while the second corresponds to the girder end rotation angle. This function is applicable when the two longitudinal girders have the same rotation angle, as the rotation term is constant along the y-axis. However, in the case of different rotation angles, the link slabs together form a torsional member, as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Diagram of link slabs at different rotation angles.

In this case, one side of the link slabs has a rotation angle of θ, while the other has a rotation angle of θ + β, with an incremental β along the transverse direction. To obtain the rotation angle of each position along the transverse, linear interpolation of the primary function is used and can be expressed as follows:

Substituting back into the rotation angle term of the original deflection function is as follows:

Replacing the term θx in Equation (18) with the term in Equation (23) can be used to obtain the deflection function at different rotation angles.

2.4. The Transverse Stress in the Negative Moment Region of the Link Slab

To calculate the transverse stress in the negative moment region of the link slab, the steel longitudinal girder is typically simplified as having a simply supported boundary condition. However, the link slab is a fixed support structure on both sides, and the area near the top of the steel beam represents a negative moment zone. The stress in this negative moment zone can be calculated by considering the simplified simply supported boundary conditions of the link slab’s end rotation angle and the width of the negative moment zone.

First, the rotation angle of the link slab’s edge (e.g., at y = 0) in the transverse direction is calculated under the simply supported condition as follows:

It is reasonable to approximate that the rotation angle of the link slab decreases uniformly to zero along the transverse direction in the region of the negative bending moment.

The (b′ − b) in Equation (25) represents the width of the negative moment zone of the fixed beam under a uniformly distributed load, with the following equation:

The transverse stress in the negative moment zone of the link slabs can be calculated as follows:

2.5. Longitudinal Bridge Stress of the Link Slab

The longitudinal stress of the link slab can be determined based on the relationship between the girder end rotation angle and bending moment [21]. It is assumed that the rotational deflection of the bridge deck link slab is uniformly distributed in the area between two adjacent spans. The maximum strain of the bridge deck link slab can be calculated by considering the longitudinal girder end rotation angle , width , and thickness of the link slab area in the geometric deflection relationship.

The maximum stress in the longitudinal direction of the bridge can be determined by substituting the maximum strain, denoted as , into the material constitutive model.

3. Analysis in Engineering Applications

3.1. Background

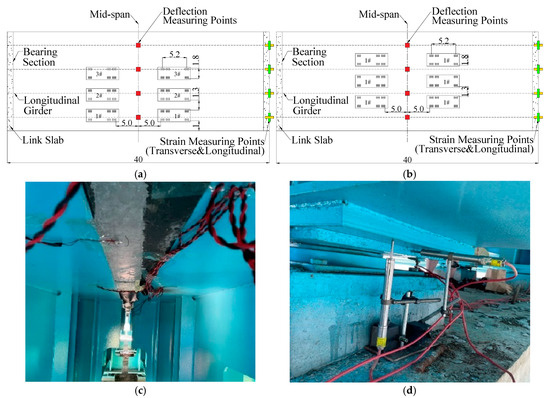

To apply and validate the proposed theoretical method, load tests were carried out on a composite bridge equipped with link slabs, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Load test on composite bridge with UHPC link slab: (a) in situ UHPC link slab; (b) load test site.

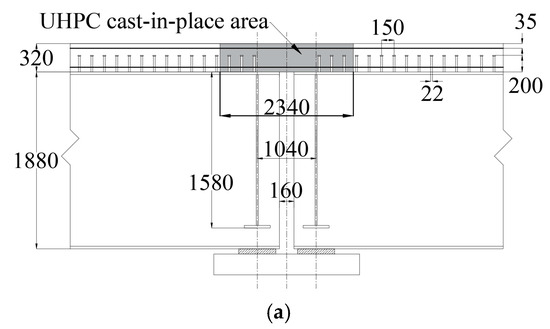

The bridge configuration is shown in Figure 6. The bridge is 40 m each span, 12.4 m wide, and has four longitudinal I-girders and a concrete deck. The spacing between adjacent steel longitudinal girders is 3.4 m. The I-beam height is 1.88 m, with crossbeams placed every 5 m within the spans.

Figure 6.

Bridge configuration diagram: (a) longitudinal section; (b) bearing transverse section (unit: mm).

The link slabs are positioned at the joints of the two-span simply supported beams and have a height of 0.32 m. These cast-in-place slabs feature reinforcing bars interconnected with reserved bar joints in the concrete deck slabs on the existing girders on both sides. Shear connections to the steel girders are achieved through studs welded into the top plates of the end crossbeams.

The longitudinal girders are fabricated from Q345 steel, while the transverse connections and stiffening ribs are composed of Q235 steel. The bridge deck is precast using C50 concrete. The link slabs are constructed by casting UHPC120 and reinforced with HRB400 to enhance their crack resistance and prolong their service life. The thickness of the link slab is 0.32 m, and a solid web end crossbeam with a height of 1.58 m is located at the support section. The distance between the ends of a two-adjacent-span longitudinal girder is 0.16 m, with the bearing distance from the two-span symmetric surface measuring 0.52 m. The properties of the material are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Material properties.

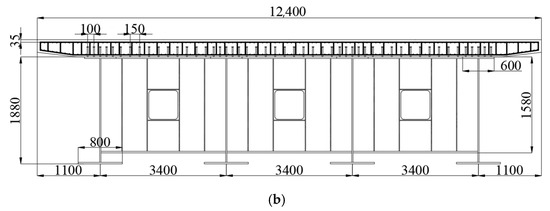

Figure 7 shows the symmetrical and eccentric loading positions as well as the deflection and strain measurement points for the load test. Both symmetric and eccentric loading are symmetric about the midspan. For the eccentric load condition, as shown in Figure 7a, the vehicles were loaded in three steps. In the first step, two trucks in one line were arranged 1 m away from the edge of the bridge. For the other two load steps, trucks were loaded in lines at an interval of 1.3 m transversely between the load steps. For the symmetric load condition, as shown in Figure 7b, all six 360 kN vehicles were symmetrically arranged in two rows at 5.0 m away from the bridge’s midspan section. During the load test, midspan deflections of the longitudinal girders were collected using a digital level, and strains were measured with vibrating wire strain gauges installed on the symmetrical line of the link slabs.

Figure 7.

Load position and measuring points: (a) eccentric load; (b) symmetric load; (c) strain measuring points (underside); (d) rotation measuring points (unit: m).

3.2. Finite Element Modeling and Verification

In this section, we present how a finite element model was developed to simulate both symmetric and eccentric loading conditions based on the background bridge. The results from the eccentric loading were primarily used to validate the finite element model against the load test results. Additionally, the results under symmetric loading from both the finite element analysis and the load tests were used to confirm the accuracy of the proposed method for analyzing the link slab.

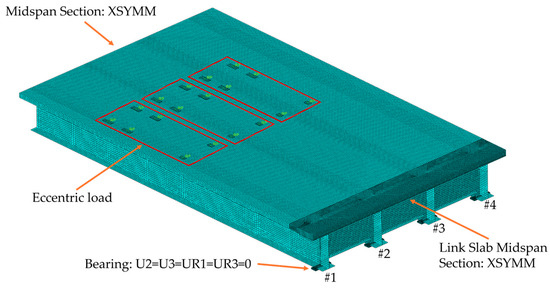

Since the loads in the load test were symmetric about the midspan, a half-bridge finite element model was used to simulate the behavior of the bridge in ABAQUS 2021. The model included C3D8R solid elements representing the concrete bridge deck and link slabs, S4R shell elements representing the longitudinal girder and crossbeams, and T3D2 truss elements representing the steel reinforcement. Cohesive contacts were set between the concrete deck slab and longitudinal girders to simulate bolted connectors [30].

In the finite element model, symmetric constraints were applied to both the midspan section and the symmetric section of the link slab. Transverse translation and rotation were also constrained. The element size for the bridge concrete deck was 100 mm, and the steel girders were meshed with a size of 50 mm. The total number of elements in the model was 700,000.

Ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) was modeled using the Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) model in Abaqus 2021. The material properties included a modulus of elasticity of 54.7 GPa (from a 2-inch, 50 mm cube test) and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.18. The expansion angle was set at 56°, with an eccentricity of 0.1, and the fb0/fc0 ratio was 1.1. Additionally, the values for k, peak tensile stress, and peak compressive stress were defined as 0.66, 9.7 MPa, and 138 MPa, respectively. These parameters, along with the stress–strain and damage curves for UHPC, were referenced from Shafieifar et al. [31]. The strength of C50 concrete was determined according to Fib 2010 [32]. The Tri-line constitutive model was employed for the steel girder and reinforcement [33,34].

Figure 8 shows the numerical model, taking the eccentric loading case as an example. Symmetric constraints in the ZY plane (XSYMM) were set in the midspan section and adjacent-span symmetric section, and translations and rotations around both the Y-axis and Z-axis were also constrained at the supports. The rigid blocks in the red ovals denote the positions for arranging the vehicle wheel load.

Figure 8.

Finite element model.

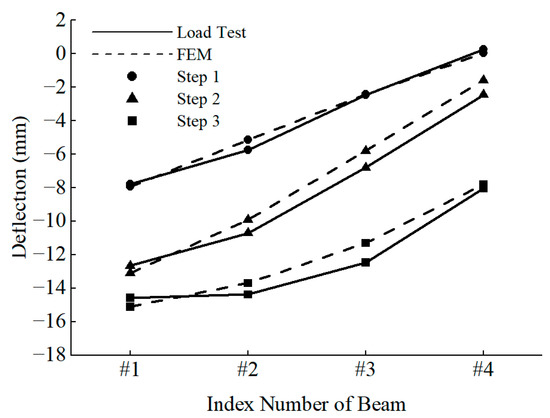

The top deflection values of the four longitudinal girders were compared under the eccentric load condition with the load test to validate the accuracy of the finite element model. This condition accounts for both the longitudinal stiffness and the transverse stiffness of the bridge, thereby providing a more accurate verification of the finite element model.

Under the eccentric load conditions, the lower deflection exhibited distinct transverse distribution characteristics. The deflection values of the four girders in the span were compared to those of the load test and the finite element simulation to verify the validity of the finite element model, which is more accurate for assessing the bridge’s longitudinal and transverse stiffness. Figure 9 shows that under the second-step loading, the average deflection measured in the load test was 8.15 mm, while the average deflection predicted by the finite element simulation was 7.60 mm, yielding a difference of 6.78%. Similarly, under the third-step loading, the average deflection measured in the load test was 12.36 mm, and the average deflection predicted by the finite element simulation was 11.98 mm, resulting in a difference of 3.13%. The differences between the finite element model and load test results were less than 10%, demonstrating the validity of the finite element model.

Figure 9.

Comparison of load test and FEM results.

3.3. Results and Analysis

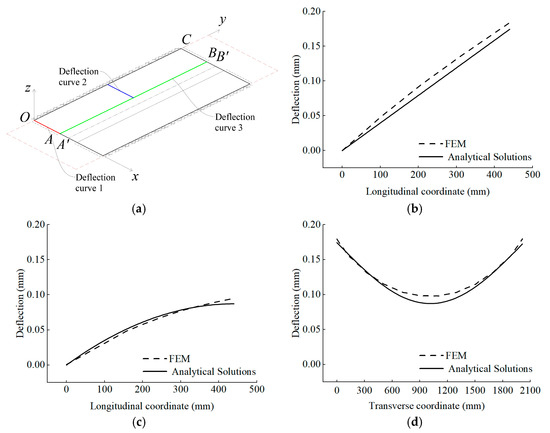

To further investigate the deflection of the link slab, the rotation angle of the two middle steel longitudinal girders was obtained from the load test and used in the deflection function equation. Then, the deflection curves at three representative positions in the link slab, obtained by the finite element and deflection function, were compared to analyze the validity and accuracy of the deflection function. The three positions of the link slab and their deflection curves are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Deflection curves of three feature locations form FEM and deflection function: (a) feature locations; (b) deflection curve 1; (c) deflection curve 2; (d) deflection curve 3.

Deflection curve 1 was located on the boundary line of the positive moment zone of the link slab (red line in Figure 10a), and the deflection curve is shown in Figure 10b. The curves had generally consistent slopes, indicating that the results from the finite element and the load tests were similar. However, the maximum deflection of the finite element model was slightly larger than that of the theoretical curve, with a difference of 5.4%. This difference resulted from the neglect of longitudinal beam deflection in assumption (1) in Section 2.1. The minimal difference between the two curves served as evidence for the validity of this assumption.

Deflection curve 2 was located on the centerline of the link slab (blue line in Figure 10a), and the deflection curve is shown in Figure 10c. The analytical solution at this position yielded a larger slope than that of FEM simulation at the support position, which was due to the simplification of the border conditions at the concrete plate and end crossbeam in the theoretical model. The concrete slab and the end crossbeam at this section were subjected to the bending moment, causing the concrete deck-slab to deform due to its low stiffness, while the end crossbeam was subjected to an out-of-plane bending moment, resulting in torsional deflection around the transverse direction, which was much less stiff than the longitudinal girder. Therefore, the actual structure at this position had torsional deflection of the end crossbeam around the transverse direction. The FEM result at this position reflected the effect of steel beam deflection as well. In the second half of the curve, the influence of neglecting the torsions of the deck plate and end crossbeam decreased while the effect of neglecting steel longitudinal girder deflection increased, which meant the theoretical analysis solution was smaller than the FEM numerical solution. The theoretical analysis solution used an approximate symmetric boundary condition, resulting in a slope of 0 at the end of the curve. The maximum deflections were 0.08725 mm from the theoretical analysis solution and 0.09381 mm from the FEM simulation, with a standard deviation of 6.99%. The overall trend of the two curves was consistent, indicating the feasibility of simplifying the boundary conditions of the link slab.

Deflection curve 3 was located on the end of the longitudinal girders, along the transverse direction (green line in Figure 10a), and the deflection curve is shown in Figure 10d. At the position of the longitudinal girders, the theoretical and numerical curves were in close agreement, with almost identical slopes. However, at the center position of the link slab, the difference between the two curves increased. The difference in the curves arose from the limited number of terms n included in the calculations when using Equation (18). This variation indicated that the accuracy of the calculations with a smaller value of n met the necessary requirements.

4. Transverse Stress of the Link Slab and Parametric Study

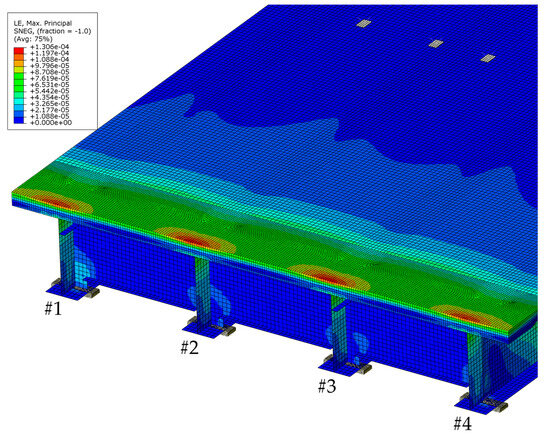

4.1. Transverse Stress

Based on the concrete strain map extracted from the FEM results (LE, Max, Principal), as shown in Figure 11, the maximum strain was observed at the upper edge of the link slabs situated at the end of the steel longitudinal girder. This position is characterized by the discontinuity of the steel beam from the longitudinal bridge upwards, resulting in a sudden change in cross-sectional stiffness and longitudinal stress concentration. The link slabs at the top of the steel beam are in the transverse negative moment zone, and the upper edge of the link slabs is subjected to the maximum transverse tensile stress. The combined effect of tensile stress in both directions results in the most severe stress concentration at this location, thus making it more susceptible to cracking.

Figure 11.

Concrete strain cloud map.

The peak transverse and longitudinal stresses obtained from three methods are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Peak transverse and longitudinal stresses.

The calculated transverse and longitudinal stress results from the theoretical analysis revealed a transverse-to-longitudinal bridge stress ratio of 0.38:1, indicating that the link slabs at the end of the steel longitudinal girder were under significant tensile stress in both directions. According to the biaxial stress theory of concrete [35], increased bi-directional tensile stresses do not diminish the overall tensile strength of concrete. However, the total tensile stress must be calculated by jointly considering both transverse and longitudinal stresses. In the bridge analyzed in this study, the total tensile stress, after accounting for transverse stresses, was 7% greater than the longitudinal tensile stress. This difference may be even more pronounced under various link slab design parameters, potentially leading to the early onset of cracks in the link slabs and worsening their deterioration.

4.2. Parametric Study

Based on the above analysis, the peak stress of the link slab occurred at the end of the steel longitudinal girder, and the influence of the design parameters of the link slab on the peak stress is analyzed herein. In the proposed analytical method, the three parameters that are most directly related to the link slab are the length from the from the bearer to the end of the steel beam (a), the distance between adjacent main beams (b′), and the thickness of link slab (δ). The labeling for these parameters is shown in Figure 2.

In the following, the transverse stress at the peak stress location will be calculated by the proposed analysis method for different values of the three parameters (a, b′, and δ) and the ratio of the transverse stress to the longitudinal stress, using the original structural dimensions of the link slab in the engineering example as 100% (original value a = 0.44 m, b′ = 3.4 m, δ = 0.32 m).

- (1)

- Bearer to steel longitudinal girder end length a:

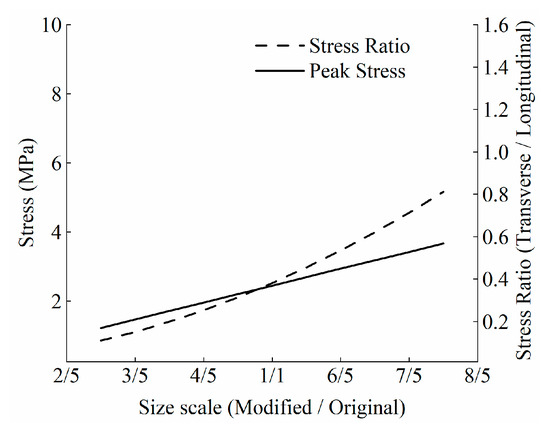

Figure 12 shows the linear relationship between the peak transverse stress and the overhanging distance from the interior bearer to the end of the steel longitudinal girder (i.e., the length of the steel girder end). As the length of the steel girder end increases, the maximum deformation of the link slab at the steel girder end section also increases. This means that the curvature of the downward deflection curve of the link slab at the steel girder end section is larger, the deflection curve of the negative bending moment is greater, and the strength of the negative bending moment is increased. The tensile stress at the edge of the link slab is also higher. When the length of the steel girder end increases, the width of the link slab area increases, and the deflection capacity is enhanced. The longitudinal stress decreases, while the proportion of transverse stress increases. Both the transverse stress and its ratio to the longitudinal stress increase with the length of the longitudinal girder end, after the length of the longitudinal girder end is increased by 3/2 of the original size, the transverse stress increases by 50% compared to the original size, and the ratio of transverse and longitudinal stresses increases from 0.38 to 0.81. This indicates that the total stresses are actually 129% of the longitudinal stresses, and the impact of transverse stress on the link slab increases with a longer girder end.

Figure 12.

Effect of the length from the bearer to the end of the beam on the peak stress.

- (2)

- Spacing b′ of adjacent steel longitudinal girders.

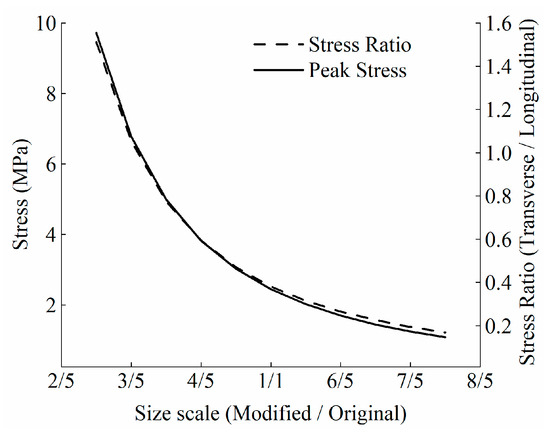

The curve in Figure 13 indicates that when the distance from the bearer to the end of the steel longitudinal girder and the girder end angle remain constant, the maximum deflection of the link slab also remains constant. When the distance b′ between adjacent steel longitudinal girders is larger, the structure stiffness is smaller and the negative bending moment area is wider, which reduces the tensile strain and stress at the upper edge of the link slab. The distance between adjacent longitudinal girders has little effect on the longitudinal bridge stress of the link slab, but has a significant effect on the transverse bridge stress. When the distance is reduced to 3/5 of the original bridge length, the ratio of transverse to longitudinal bridge stress reaches 1.05, resulting in total stress reaching 145% of the longitudinal stress. This indicates that in the case of smaller distances between steel beams, ignoring the effect of transverse bridge stress on the stress and cracking calculation of the link slab can have a significant impact.

Figure 13.

Relationship between the spacing of adjacent steel longitudinal girders and peak stress.

- (3)

- Both a and b′ change in the same proportions.

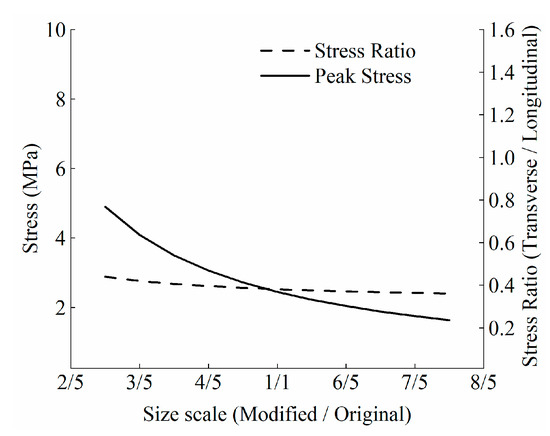

The curves in Figure 14 show that when the ratio of the two parameters mentioned above is constant, the peak transverse stress decreases with the increase in the overall size of the structure, which reflects that the spacing between the longitudinal girders has a more significant impact on stress. Moreover, when the end length of the beams and the spacing between the beams are fixed, both the transverse and the longitudinal stresses increase or decrease simultaneously with a constant ratio.

Figure 14.

Relationship between size and peak stress at constant a and b ratio.

- (4)

- Thickness δ of link slab.

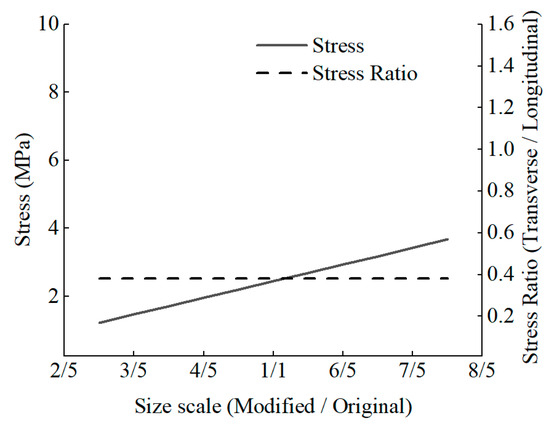

Figure 15 shows the relationship between the stresses and the thickness δ of the link slab. In the range of linear elasticity considered in this investigation, the transverse and longitudinal stresses are linearly related to the thickness of the link slab, and the transverse and longitudinal stress ratios do not change with the variation in the thickness of the link slab, which indicates that the transverse stresses may have an effect in any thickness of link slab.

Figure 15.

Relationship between thickness δ and peak stress.

Based on the aforementioned investigation, it can be inferred that bridges with link slabs, especially those featuring longer longitudinal lengths in the link slab area, are more susceptible to transverse stress issues. This susceptibility is heightened when the number of longitudinal girders increases and the spacing between them decreases. Therefore, it is advisable to enhance the calculation of transverse stress in the link slab structure for bridges with a multi-girder deck system. Additionally, reducing the spacing between adjacent span supports within a reasonable range is recommended.

According to the theoretical results, the link slab regions at the girder ends are identified as the most vulnerable location for crack development. It is critical to maintain a continuity of reinforcement in order to enhance crack resistance at this particular location, as well as to provide sufficient reinforcement to resist flexural stresses and to ensure that crack widths are within allowable limits. To enhance crack resistance at this specific locations, it is crucial to maintain reinforcement continuity. This ensures optimal crack resistance. In cases where transverse stress exerts a more significant influence, additional measures can be implemented to further improve crack resistance in this region. One effective measure may be employing transverse prestressing tendons. By incorporating transverse prestressing tendons in this section, the regional resistance to cracking can be further enhanced.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces a new analysis method for link slabs that accounts for transverse deformation and stresses. Utilizing the partial differential equations (PDEs) of plates, two-dimensional distribution equations for deflection and stress in the link slab were derived. The proposed method was validated through load tests on a bridge equipped with UHPC link slabs and finite element modeling (FEM). Additionally, the proposed method was used to conduct a parametric study of the spacing between steel girders, the length of girder ends, and the thickness of the link slabs. The following conclusions can be drawn from this study:

- (1)

- Based on the proposed deflection and stress distribution equations for the link slab, bending due to beam end rotation induces deflection and stress not only in the longitudinal direction but also in the transverse direction. Both transverse and longitudinal peak stresses occur at the upper edges of the girder ends, which represent the most concentrated stress areas and are particularly susceptible to cracking. In the case of the bridge analyzed in this study, which utilizes UHPC link slabs, transverse stresses reached 38% of the longitudinal stresses, resulting in actual tensile stresses that were 107% of those designed based solely on longitudinal considerations.

- (2)

- This study analyzed the factors influencing peak stresses using theoretical analytical solutions and identified the trends of peak transverse tensile stresses under three parameter variations. With constant beam end rotation, an increase of 50% in the distance from the bearing section to the longitudinal girder end resulted in a 50% increase in transverse stress. Additionally, reducing the transverse spacing between main girders by 40% led to transverse stress levels reaching 105% of the longitudinal stress. Furthermore, the thickness of the link slab affects both transverse and longitudinal stresses simultaneously and linearly, without altering their ratio.

- (3)

- This study also found that increasing the length of the girder ends by 50% or reducing the spacing of the longitudinal girders by 40% resulted in total stresses, considering transverse stresses, rising to 129% and 145% of the longitudinal stresses, respectively. Therefore, if only longitudinal stresses are considered as a controlling factor in the design of the link slab, the impact of transverse stresses on the overall stress analysis is significant and must be included in the evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.D. and Z.H.; methodology, W.D. and Z.H.; software, W.D. and Z.Z.; validation, W.D. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, W.D.; investigation, W.D.; resources, Z.H.; data curation, W.D.; writing—original draft preparation, W.D.; writing—review and editing, Z.H. and Z.Z.; visualization, W.D.; supervision, Z.H.; project administration, Z.H.; funding acquisition, Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the people who have supported this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bernabeu Larena, J. Evolución Tipológica y Estética de Los Puentes Mixtos En Europa. Ph.D. Thesis, E.T.S.I. Caminos, Canales y Puertos (UPM), Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gervásio, H.; da Silva, L.S. Comparative Life-Cycle Analysis of Steel-Concrete Composite Bridges. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2008, 4, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, J.P.; Matsumoto, Y.; Yamaguchi, H.; Kurahashi, I. Numerical Investigation of Noise Generation and Radiation from an Existing Modular Expansion Joint between Prestressed Concrete Bridges. J. Sound Vib. 2009, 328, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveall, C.L. Jointless Bridge Decks. Civ. Eng. 1985, 55, 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Marques Lima, J.; de Brito, J. Inspection Survey of 150 Expansion Joints in Road Bridges. Eng. Struct. 2009, 31, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepech, M.D.; Li, V.C. Application of ECC for Bridge Deck Link Slabs. Mater. Struct. 2009, 42, 1185–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Shah, Y.I.; Yu, S. Cracking Analysis of Pre-Stressed Steel–Concrete Composite Girder at Negative Moment Zone. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 10771–10783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, A.; Aleti, A.R. Behavior of FRP Link Slabs in Jointless Bridge Decks. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2012, 2012, 452987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolde-Tinsae, A.M.; Klinger, J.E.; White, E.J. Performance of Jointless Bridges. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 1988, 2, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alampalli, S.; Yannotti, A.P. In-Service Performance of Integral Bridges and Jointless Decks. Transp. Res. Rec. 1998, 1624, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulku, E.; Attanayake, U.; Aktan, H. Jointless Bridge Deck with Link Slabs: Design for Durability. Transp. Res. Rec. 2009, 2131, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Zhao, S.C.; Li, L. Study on Bridge Deck Link Slabs of Simply Supported Girder Bridges. AMR 2014, 1079, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Briseghella, B.; Huang, F.; Nuti, C.; Tabatabai, H.; Chen, B. Review of Ultra-High Performance Concrete and Its Application in Bridge Engineering. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 260, 119844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graybeal, B.A. Emerging Uhpc-Based Bridge Construction and Preservation Solutions. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Ultra-High Performance Fibre-Reinforced Concrete, Montpellier, France, 2–4 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L.B.; Hafezolghorani, M.; Mohamed, A.; Voo, Y.L.; Gopal, B.A.; Ghaedid, K. The First Application of Ultra-High Performance Concrete Link Slab in Malaysia. ASEAN Eng. J. 2024, 14, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Briseghella, B.; Xue, J.; Pan, X. Research on Flexural Performance and Crack Width Calculation Method of Ultra-High Performance Concrete Link Slab. Bridge Constr. 2022, 52, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Abdal, S.; Mansour, W.; Agwa, I.; Nasr, M.; Abadel, A.; Onuralp, Y.O.; Akeed, M.H. Application of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete in Bridge Engineering: Current Status, Limitations, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Buildings 2023, 13, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caner, A.; Zia, P. Behavior and Design of Link Slabs for Jointless Bridge Decks. PCI J. 1998, 43, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, K.M.; Kowalsky, M.J. Behavior, Analysis, and Design of an Instrumented Link Slab Bridge. J. Bridge Eng. 2005, 10, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, A.; Lam, C.; Au, J.; Tharmabala, B. Eliminating Deck Joints Using Debonded Link Slabs: Research and Field Tests in Ontario. J. Bridge Eng. 2013, 18, 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeil, A.M.; ElSafty, A. Partial Continuity in Bridge Girders with Jointless Decks. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2005, 10, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Safty, A.; Okeil, A.M. Extending the Service Life of Bridges Using Continuous Decks. PCI J. 2008, 53, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Huang, Q.; Huang, J. Theoretical Analysis for Static and Dynamic Characteristics of Multi-Simple-Span Bridge with Continuous Deck. Eng. Mech. 2015, 32, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergess, A.N. Analysis Of Bonded Link Slabs In Precast, Prestressed Concrete Girder Bridges. PCI J. 2019, 64, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergess, A.N.; Douaihy, E.Z. Effects of Elastomeric Bearing Stiffness on the Structural Behavior of Bonded Link-Slabs. Transp. Res. Rec. 2020, 2674, 428–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergess, A.N.; Hawi, P.F. Structural Behavior of Debonded Link-Slabs in Continuous Bridge Decks. J. Bridge Eng. 2019, 24, 04019030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shen, Y.; Zou, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, T. Analysis of Mechanical Characteristics of Steel-Concrete Composite Flat Link Slab on Simply-Supported Beam Bridge. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 3571–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, Q.-S.; Jia, B.-Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Yu, X.-L. An Analytical Method for Full-Range Mechanical Behavior of Continuous Slab-Deck in Multi-Span Simply Supported Concrete Bridges. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2022, 25, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, A.E.H. XVI. The Small Free Vibrations and Deformation of a Thin Elastic Shell. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 1888, 179, 491–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Chen, L.; Wen, M.; Xu, C. Static Behavior of Stud Shear Connectors in High-Strength-Steel–UHPC Composite Beams. Eng. Struct. 2020, 218, 110827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafieifar, M.; Farzad, M.; Azizinamini, A. Experimental and Numerical Study on Mechanical Properties of Ultra High Performance Concrete (UHPC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 156, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fib Special Activity Group, N.M.C.; Taerwe, L.; Matthys, S. Fib Model Code for Concrete Structures 2010; Ernst & Sohn, Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-3-433-60409-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ansi, B. AISC 360-16, Specification for Structural Steel Buildings; Chicago AISC: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gang, S.; Xi, Z. Study on Constitutive Model of High-Strength Structural Steel under Monotonic Loading. Eng. Mech. 2017, 34, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupfer, H.; Hilsdorf, H.K.; Rusch, H. Behavior of Concrete Under Biaxial Stresses. ACI J. Proc. 1969, 66, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).