Abstract

Tulou dwellings in Southeast China have captivated global interest due to their distinctive appearance, sustainable construction materials and technologies, and their defensive and collective housing functions. Despite several being recognized as World Cultural Heritage sites, the vast majority of tulou buildings are undergoing irreversible decline and destruction, necessitating a comprehensive and systematic study. Taking 83 tulou buildings in Raoping County, Chaozhou City, Guangdong Province as the research object, this study reconstructs the historical scenes and systematically reveals the emergence, popularity, and consolidation process of tulou dwellings as integrated defensive and residential buildings for ordinary people by conducting a comprehensive analysis of historical documents and local chronicles. Based on an extensive field investigation, the study systematically analyzes the geospatial distribution and the spatial characteristics of Raoping tulou and its residential unit. The results demonstrate the adaptability and flexibility of tulou dwellings, showcasing their developmental process and revealing the inclusive nature of these traditional residences, as well as the initiative of those who reside within them. The research findings contribute to a more dynamic, comprehensive, and authentic understanding of tulou and Chinese traditional residences, providing valuable references for the preservation and sustainable development of tulou architectural heritage.

1. Introduction: Tulou (the Rammed Earth Dwelling) of Chaozhou, Guangdong (Canton) Province, China

A recent study by the United Nations has revealed that approximately one-third of structures worldwide are constructed using earth as a primary construction material. This highlights the widespread and enduring use of earth in building practices globally [1]. Tulou, distinctive rammed earth residential structures predominantly found in the neighboring regions of Fujian, Guangdong, and Jiangxi provinces in China, were constructed between the 14th and 20th centuries. Due to their distinct form and ingenious construction technique, they are often referred to as “China’s most extraordinary folk dwellings [2]. The term “tulou” is derived from the Chinese characters (tǔ “±” «earth» and lóu “楼” «multi-story house»). It signifies multi-story dwellings built with earth materials such as rammed earth or adobe. These structures are highly regarded as the culmination of centuries of wisdom, reflecting the historical and social context of their time. They were consciously designed to blend harmoniously with the surrounding natural environment, adapt to local geographical conditions and climate, and efficiently utilize available resources to fulfill both physical and spiritual needs.

Tulou, along with being recognized as remarkable feats of sustainable architecture, are renowned for their utilization of local materials such as rammed earth, earth blocks, stone, and wood; the employment of traditional construction techniques; low energy consumption during construction; and the ability for discarded materials to seamlessly integrate with the natural environment.

The international acclaim bestowed upon these unique structures is evident by the designation of 46 tulou in Fujian Province as World Cultural Heritage sites. Additionally, numerous studies have been conducted to explore various aspects of tulou, including their typology, spatial organization, materials, construction technique, structural characteristics, and geographic distribution [3].

Nonetheless, it should be noted that the majority of research on tulou primarily consists of case studies focused on Fujian Province, with only a small portion dedicated to the Hakka region of Jiangxi Province and even fewer studies involving the Guangdong tulou. In fact, most studies tend to equate “tulou” solely with earthen Hakka structures in Fujian [4].

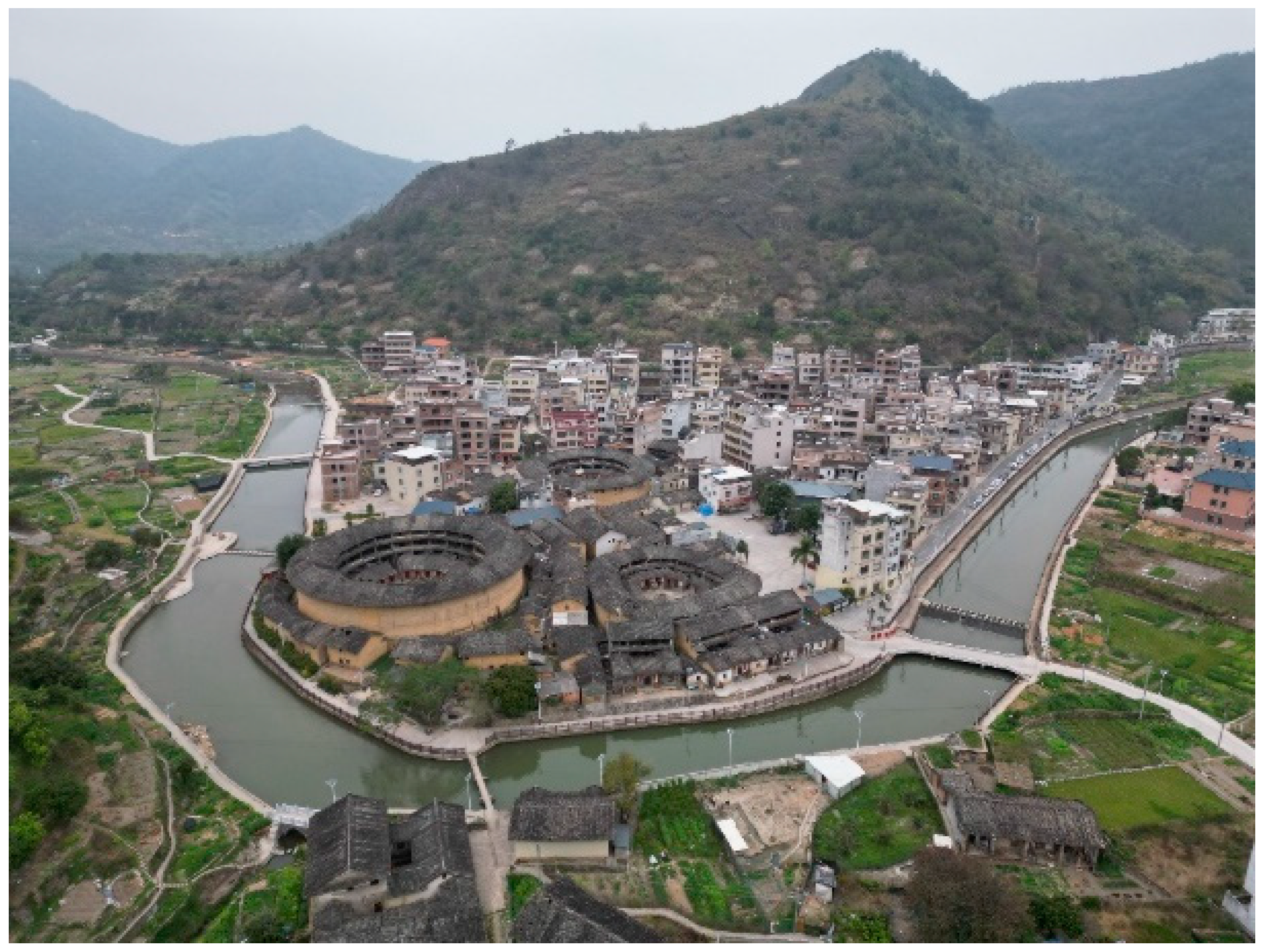

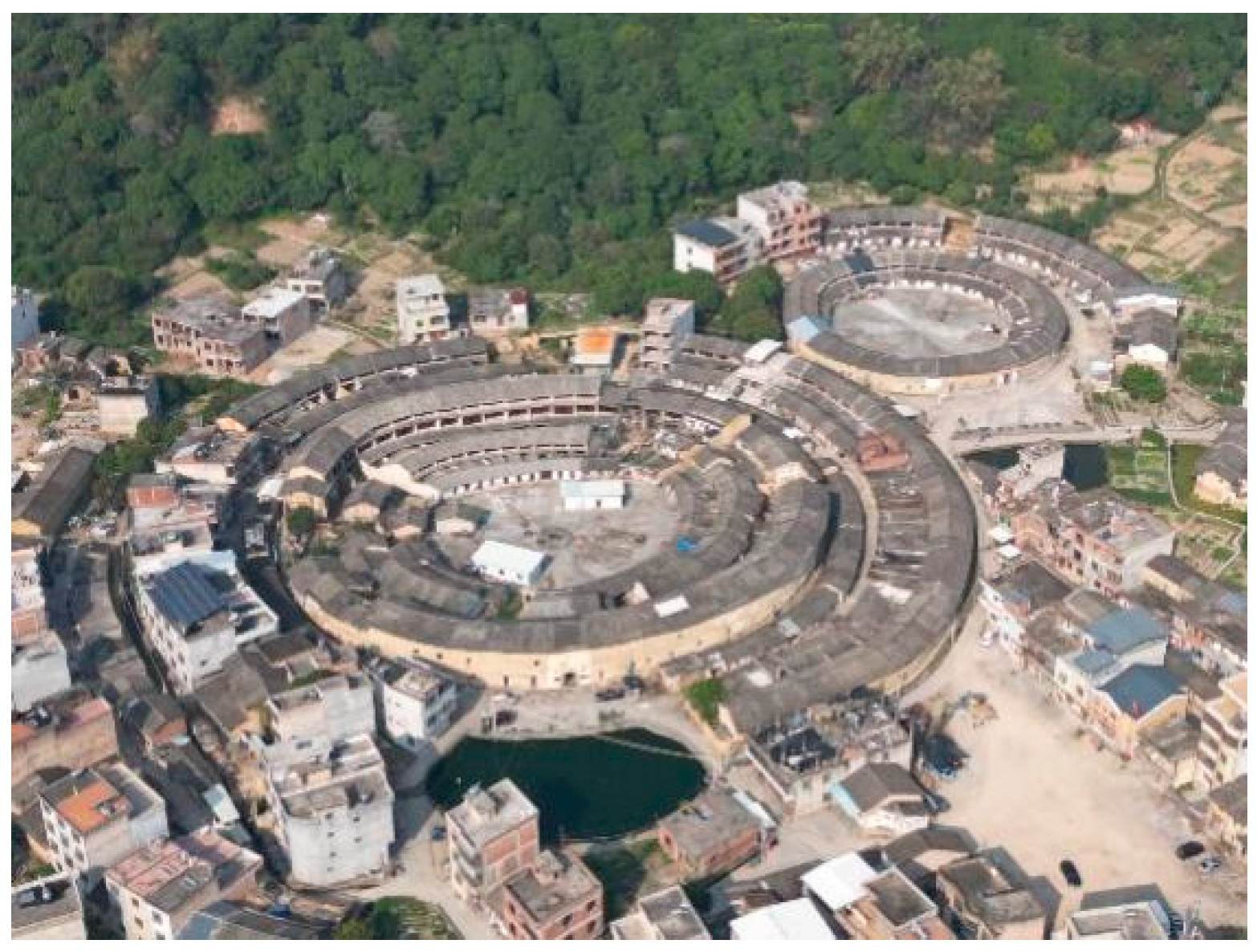

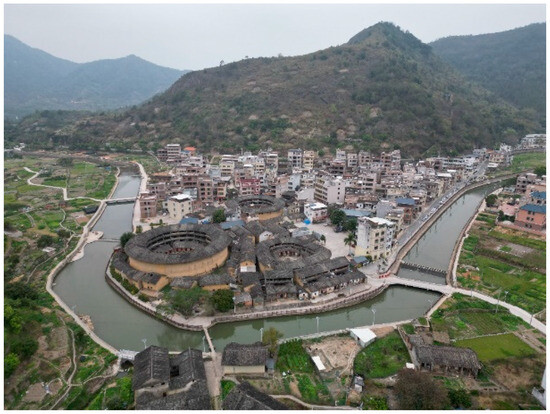

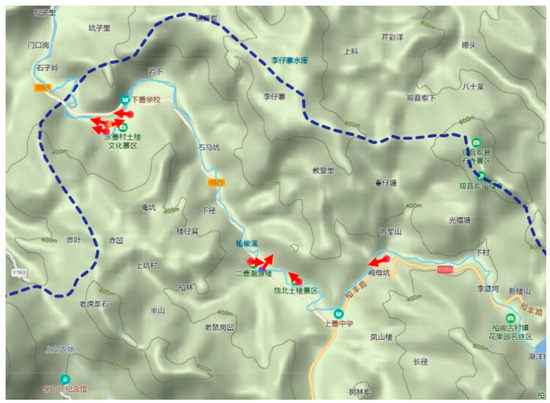

Tulou in Guangdong are predominantly found in Raoping County, Chaozhou City, which borders Fujian Province. As per the Raoping Xianzhi (Records of Raoping County), prior to the Reform and Opening-up, 781 tulou were documented and dispersed across 16 towns. Between 2007 and 2011, during the third national survey of immovable cultural relics, 217 tulou were registered in Raoping County. This included one national key cultural relic protection unit (“道韵楼”, Daoyun Lou), nine provincial cultural relic protection units, 10 county-level cultural relic protection units, and 63 immovable cultural relics (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Tulou in Raoping County, Chaozhou City, Guangdong Province, China.

Figure 2.

Donghua Lou, Nanyang Lou, Fuhai Lou in Shangrao Town.

Situated within a cultural transition zone, Raoping County borders the core region of Hakka culture (Meizhou City) to the north and the heartland of Fulao. (The Fulao, a sub-group of the Han ethnic group, originated from the central plains of the Yellow River in northern China and mainly reside in Minnan (Southern Fujian) and Chaozhou (Eastern Guangdong) areas. The Fulao and Hakka ethnic sub-groups, to whom tulou dwellings are attributed, migrated to this region via two distinct routes: the Minnan arrived from the southern coast and settled at the estuary of major waterways, whereas the Hakka crossed over the Wuyi Mountains and established themselves along river valleys. (For further information regarding the migration history of these two ethnic sub-groups, please refer to Knapp 2000, 223; Zhou and Dong 2015)) [5] culture (Chaozhou City) to the south [6].Raoping tulou are not only abundant in quantity but also boast unique regional characteristics in shape, form, structure, and spatial pattern. By taking Minnan unit tulou (despite their generic uniformity, Chinese tulou can be roughly divided into two groups: Minnan and Hakka tulou. These were built by the Minnan and Hakka populations, respectively, reflecting their different ways of life and ideas about living (corresponding to the unit layout and the circular corridor layout) as the basic prototype, while being noticeably influenced by the Hakka “Wei Long House” (Hakka residential buildings in different historical periods and different regions have different changes, including Tulou, Weilou, Diaolou, etc., while the most representative one is the Weilongwu in Meizhou, Guangdong Province) (“围龙屋”, round dragon house). Raoping tulou offer a glimpse into the rich diversity of “standard” tulou dwellings, shaped by the interplay between Hakka and Fulao ethnic cultures. This insight allows us to appreciate the remarkable adaptability and broad applicability of tulou residential structures, underscoring their significant cultural and architectural value, which warrants further systematic study.

The economic prosperity driving young and middle-aged individuals to seek employment in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area has resulted in severe depopulation in rural communities. This depopulation has led to the irreversible decline and abandonment of Raoping tulou, accompanied by the loss of associated knowledge and collective memory [7]. Inappropriate technical reinforcements, along with incongruous modifications and additions for various purposes and adaptations to modern living conditions, are prevalent even among those tulou officially designated as protected cultural relics [4,8].

Therefore, it is crucial to conduct an in-depth investigation into the morphological and spatial attributes of Raoping tulou. Past lessons have shown that only through scientific and genuine research can we develop effective conservation and development strategies to prevent further societal and human-induced harm to this architectural legacy [4].

Through thorough field surveys and a combination of qualitative and quantitative statistical analyses, this study aims to provide a comprehensive overview of Raoping tulou’s features. Their geospatial distribution, characteristics of location and orientation, spatial organization, and scale of the buildings and residential units will be examined, as will the external enclosure structures and communal spaces and amenities. The insights gained from this research will contribute to the academic understanding of tulou and global earthen architectural heritage. Moreover, it will delve into the uniformity and adaptable variations of tulou dwellings and residential units in relation to differing economic investments, site dimensions, and user group sizes. This accurately showcases the practicality and adaptability of ancient residential architecture. The versatile spatial planning and design methodology of tulou unveiled in this study also holds substantial relevance for contemporary architectural design.

2. Methodology

In general, the absence of direct written records for folk architectural heritage necessitates that associated research primarily depends on fieldwork, which presents both a challenge and an opportunity in this investigation. Firstly, a total of 83 tulou cases were selected, encompassing all cultural relic protection units and immovable cultural relic tulou in Raoping County, which were officially acknowledged for their integrity and authenticity. Secondly, high-definition satellite image analysis, comprehensive field surveys including aerial imagery via drones, architectural mapping, photography, and semi-structured interviews with villagers were conducted to acquire first-hand architectural and oral historical data for subsequent qualitative and quantitative assessments.

The field investigation team consisted of two lecturers, four undergraduate students, and two graduate students from the Department of Architecture at Guangdong University of Technology. The investigation was conducted in March 2023. To ensure the consistency and completeness of data collection, a comprehensive form was developed, covering five aspects: basic information about tulou, environmental characteristics, architectural features, preservation status, and causes of damage.

Upon arrival at the tulou sites, the survey team completed the required survey content in the form, duly filled out the form, conducted surveying and mapping activities, captured photographs and videos, and carried out random sampling interviews with residents. These interviews encompassed topics such as residents’ familial migration paths and ethnic affiliations, historical aspects related to tulou construction and maintenance practices, utilization of tulou space, experiences of living within a tulou, methods employed for renovation, and their underlying reasons. The investigation specifically focused on the spatial arrangement and functional distribution of both tulou and residential units, which are the fundamental characteristics and remarkable wisdom of traditional tulou residences. Additionally, the morphological and scale features of tulou were examined for statistical purposes using measurement tools such as tape measures and laser rangefinders. During the analysis phase, this paper initially reconstructs the historical and social contexts of tulou construction in the Chaozhou area by examining historical documents and local chronicles, thus uncovering the objectives and tactics employed in building tulou. Subsequently, the geospatial distribution of the 83 tulou is assessed using a map, and the form and scale (covering area, number of residential units/rooms) of tulou are quantitatively examined. Furthermore, the spatial arrangement, external enclosed space, and distribution of ancestral halls/public halls are qualitatively scrutinized. Lastly, the layout of residential units and their variants at different scales (width and depth) are qualitatively analyzed and summarized.

3. The Construction of Folk Collective Defense Dwellings in Chaozhou

In ancient times, conflicts among nations, tribes, and clans arose globally due to a scarcity of resources. These persistent conflicts prompted the development of various defensive structures. For instance, in medieval Germany, over 10,000 military castles were built. Similarly, in Southern China, civilians constructed tulou and weizhai (“围寨”, walled villages), which served as both dwellings and defensive structures amid widespread turmoil. Weizhai were typically found in coastal plains, while tulou were constructed in inland mountainous and hilly regions [9].

The ethnic groups responsible for constructing these fortified buildings were forced to migrate from the Central Plains to Southern China between the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty and the Southern Song Dynasty. The Hakka people primarily settled in the border regions of Guangdong, Fujian, and Jiangxi provinces, while the Fulao people mainly resided in Southern Fujian and Eastern Guangdong provinces. However, these migrants did not find the peace and prosperity they sought. Instead, they encountered challenging agricultural conditions due to the mountainous terrain and limited land, as well as a chaotic social environment.

During this period, defensive architecture was mainly represented by the Wufeng Lou (“五凤楼”), a residence built and inhabited by a single wealthy family. However, during the Ming Dynasty, tulou—collective dwellings funded and shared by multiple families (usually belonging to the same clan)—quickly emerged as a popular and dominant residential building type. Contrary to what many tourism campaigns suggest, these tulou dwellings were a response to the instinctive demands for security of common people during turbulent periods, rather than the rich and powerful individuals [10].

In the mid-to-late 14th century, China’s Ming Dynasty had just been established. During this time, Japan was embroiled in a war between the Southern and Northern dynasties. While the Northern regime was expected to have friendly relations with the Ming Dynasty, the Southern regime continued to encroach on the Chinese coast. After the defeat of the Southern regime, a large number of Japanese samurai fled to the sea and formed organized pirates. From Liaodong to Guangdong, China’s coastal regions suffered a prolonged period of depredations and massacres, particularly in the provinces of Zhejiang, Fujian, and Guangdong [3].

To address this issue, Zhu Yuanzhang, the Ming Dynasty emperor, on the one hand, imposed maritime prohibitions to block contact between the inland and sea, “Forbid coastal dwellers going to sea without permission”, “Forbid coastal dwellers communicating with foreigners”, “No fishing around the sea” [11]. On the other hand, he ordered the construction of a coastal defense system including pearl-chain-form military cities (“卫所”, Wei Cheng and its jurisdictional Suo Cheng), island fortresses, and watchtowers spanning from Liaodong to Guangxi provinces. Guards were also stationed at inland estuaries, transport hubs, important towns, and small islands.

The maritime prohibition led to the impoverishment of coastal communities reliant on salt and fishing for their livelihoods, forcing them to engage in risky dealings with pirates. Concurrently, the wealthy coastal gentry, who had previously profited from maritime trade and salt production, colluded with the pirates to accumulate wealth. [12]. This collusion between internal and external forces, underground trading, and unresolved commercial disputes all contributed to armed conflicts, resulting in the infestation of Japanese pirates, sea thieves, and mountain bandits in southeastern coastal regions. This period of turmoil and violence is historically known as the “Jiajing Rebellion” (嘉靖倭乱), which denotes a series of brutal massacres that occurred during the Jiajing era (1522–1566).

Raoping County, part of Chaozhou City, is nestled between mountains and the sea. It serves as the protector of the Huanggang River estuary and is home to flourishing inland towns and villages. The bay north of Nan’ao Island functions as a natural deep-water harbor, offering the sole navigable passage from Guangdong to Fujian—an advantage exploited by Japanese pirates. As a result, Chaozhou became the region most severely impacted by Japanese piracy, with historical records detailing an alarming number of attacks and casualties. The extended occupation of Nan’ao Island by Japanese pirates posed a significant threat to the nearby inland regions [12].

Regrettably, during pirate invasions, civilians could not always seek refuge in officially constructed and fortified military cities. According to the Dongli Annals (东里志), in the thirty-first year of Ming Hongwu’s reign (1398), Japanese pirates assaulted the Dongli Peninsula in Raoping, Chaozhou. On the peninsula, there was a military Suo city called “Da Cheng Suo Cheng” (大城所城) that was officially built to defend against Japanese pirates. Local residents sought refuge in this city, but the east gate military officer, Gu Shi (顾实), opened the gate to admit refugees. However, three other officers guarding the west, south, and north gates refused entry, resulting in the brutal deaths of numerous civilians [12].

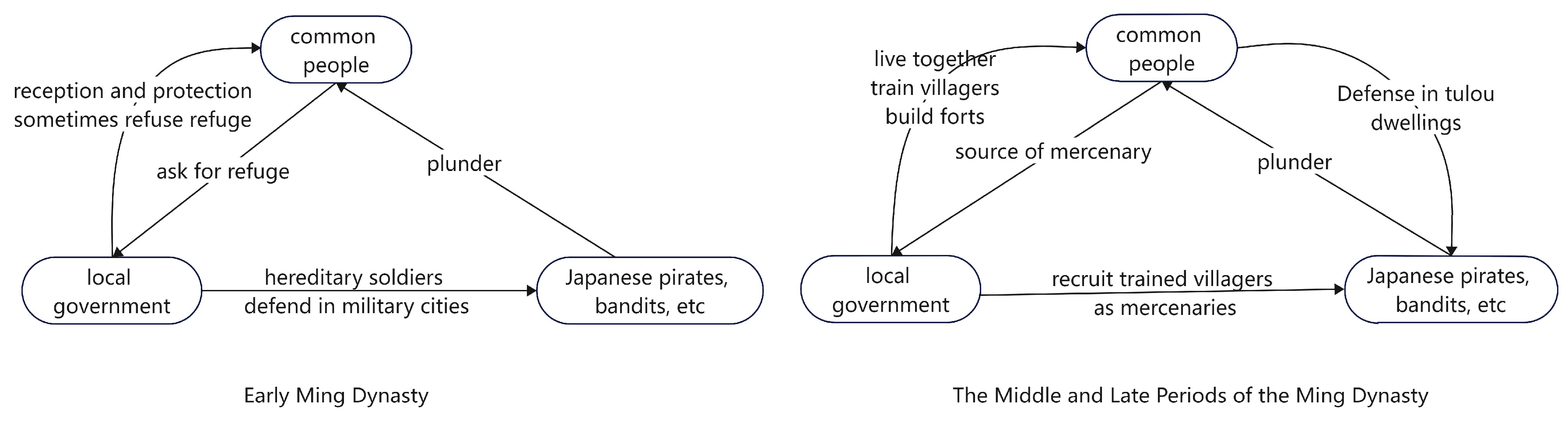

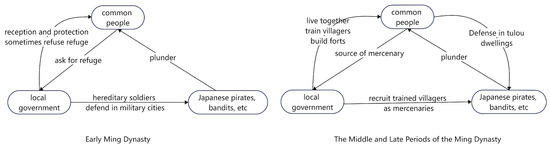

In the early Ming period, the coastal defense system played a significant role in combating piracy and maintaining regional stability to a certain extent. However, political corruption began to rise in the middle of the Ming dynasty, leading to a significant decline in the military’s ability to combat piracy. Many soldiers deserted as their rations were cut and their designated farmland (“Tuntian”, 屯田) intended for supporting their livelihoods was heavily seized by higher officials. According to Guangdong Tongzhi (广东通志), military cities such as Lianzhou (廉州), Leizhou (雷州), Shendian (神电), Guanghai (广海), Nanhai (南海), Jieshi (碣石), and Chaozhou (潮州) had a total of 8281 soldiers during the Jiajing period (1507–1567), with a shortage of 69.8%. In this social context, the common people had no choice but to organize themselves into ethnic groups for collective defense.

China’s coastal military system transitioned from the Weisuo Zhi (卫所制, hereditary soldiers defending coastal military cities) to the Mubing Zhi (募兵制, paid volunteers recruited to join the army for an agreed period). Coastal officials proposed training villagers as soldiers for self-protection, and these trained rural soldiers became an essential part of the Mubing group [13].

Local officials actively implemented the policy of “building civil forts and training civilian soldiers” to ensure local security. This provided authoritative support for the construction of defensive dwellings. The local government also encouraged smaller villages to merge and defend collectively [14]. For instance, scholar-official Huo Tao suggested that local people in Fujian and Guangdong should organize and build forts for self-defense [15]. Consequently, local clans became more closely connected based on kinship and geography, and the militarization of grassroots society rapidly increased [16].

The “training villagers” and “building forts” policies led to significant transformations in residential styles and rural landscapes in Guangdong and Fujian since the Jiajing period. In the mountainous and hilly regions bordering Fujian and Guangdong, large tulou dwellings with both defensive and communal living functions flourished (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The social context behind the prevalent of tulou.

By the end of the Ming Dynasty, a power struggle between the remnants of the Ming Dynasty and the Qing regime resulted in social unrest and frequent uprisings in the Fujian and Chaozhou areas. Large-scale riots, banditry, and conflicts among clan groups competing for limited resources and honor contributed to the enduring prominence of defense-dwellings until modern times [17]. Consequently, a clan-based collective defense system and corresponding tulou collective residential buildings were established, sustained by group forces and playing a long-term role.

4. Geospatial Distribution of Chaozhou Tulou

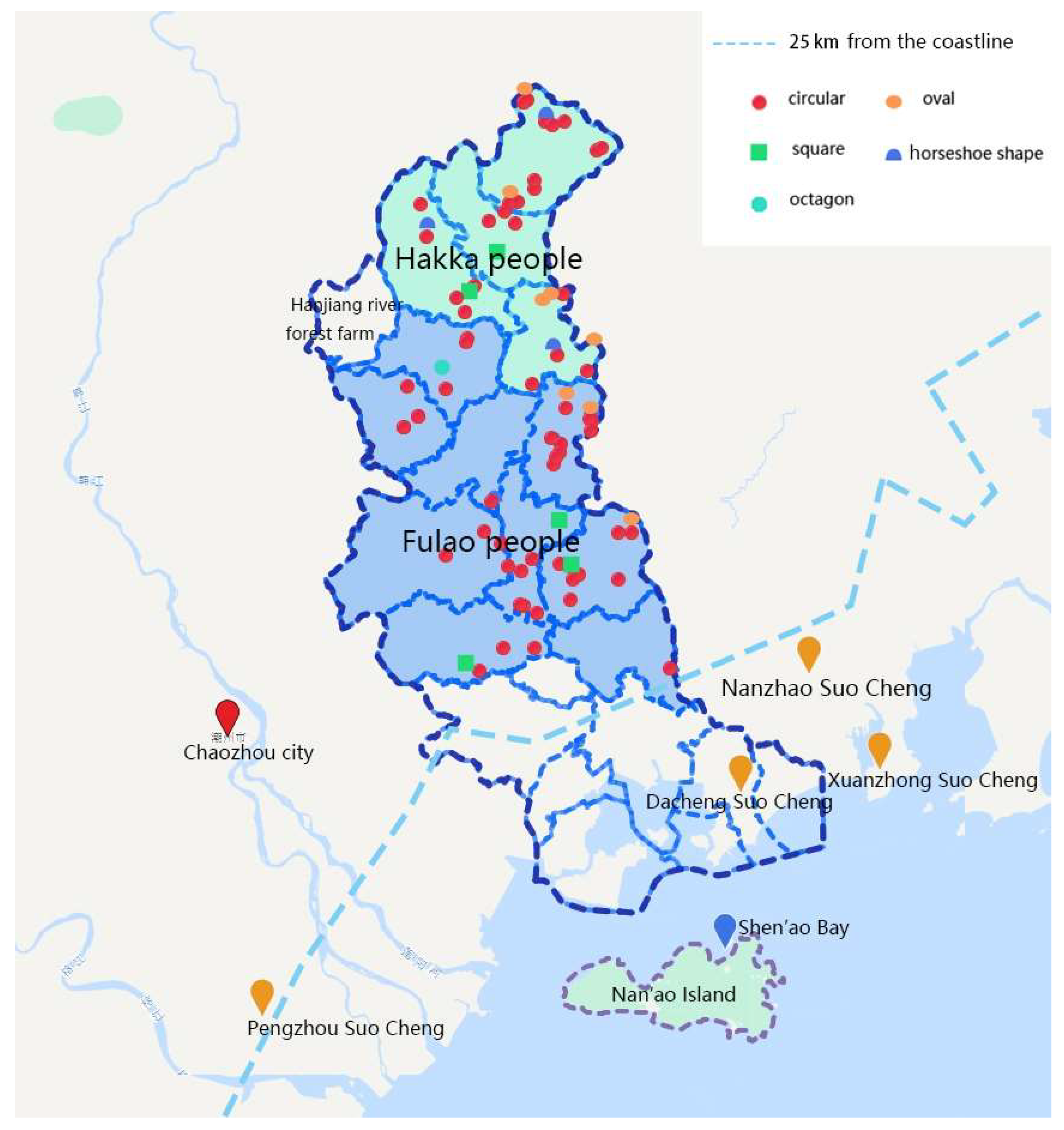

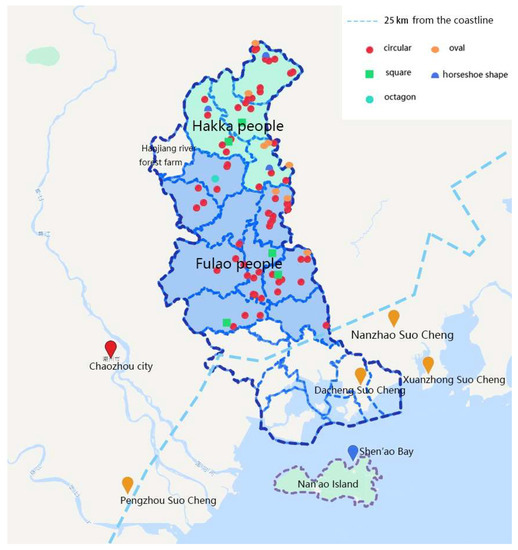

4.1. Distributed 25 km off the Coast

According to the map, Raoping tulou are uniformly distributed throughout the county, except for a 25 km area from the coastline. In 1636, the newly established Qing government sought to eliminate Zheng Chenggong’s forces, who had been defeated in the regime war and retreated to Taiwan Island. To achieve this, they issued a strict “Maritime Trade Ban”, prohibiting all forms of private maritime trade to cut off Zheng’s supplies. However, when this ban failed to achieve the desired outcome, the government implemented a “Coastal Evacuation Decree” in 1661, which compelled coastal residents to relocate 15–25 km inland. The Qing government employed aggressive tactics, including the destruction of homes, crops, and other essential resources, to drive out coastal inhabitants. Historians have verified that the “Coastal Evacuation Decree” inflicted significant damage on residential structures within dozens of kilometers of the coast, resulting in the complete demolition of coastal tulou buildings [18].

Following the “Return to the Coast” decree in 1689, the Fulao clan resettled in their original coastal locations, sparking a new wave of construction. However, during this period, the Qing dynasty was stable and society was peaceful. Consequently, people opted to construct courtyard dwellings that offered greater comfort and privacy rather than rebuilding tulou. This explains the current absence of tulou near the coast, despite the frequent conflicts that occurred during the Ming Dynasty (Figure 4).

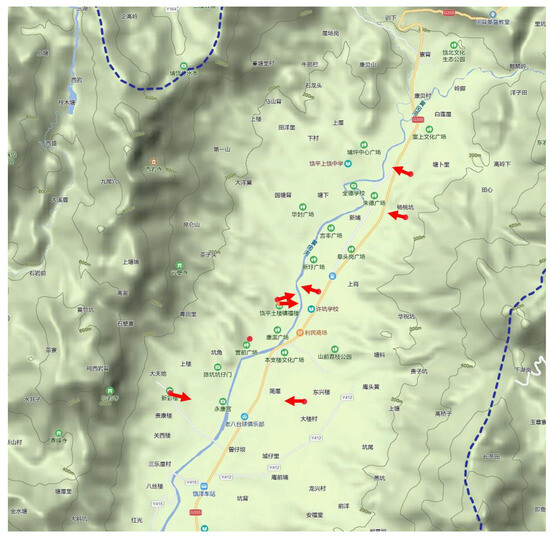

Figure 4.

Tulou in Raoping County.

4.2. Patterns of Site Selection and Orientation

In the mountainous region of Northern Raoping, tulou are typically found in fertile valleys along rivers or streams, accompanied by carefully terraced cultivated land. In the hills and plains of central Raoping, tulou continue to be distributed along rivers, which serve as communication and trade routes and provide essential water resources for agricultural fields. Generally, Raoping tulou are primarily dispersed along both sides of the Huanggang River and its tributaries: Baijun Creek, Jiucun Creek, Xintang Creek, Dongshan Creek, Fubin Creek, Xinwei Creek, Zhangxi River, and Lianrao Creek.

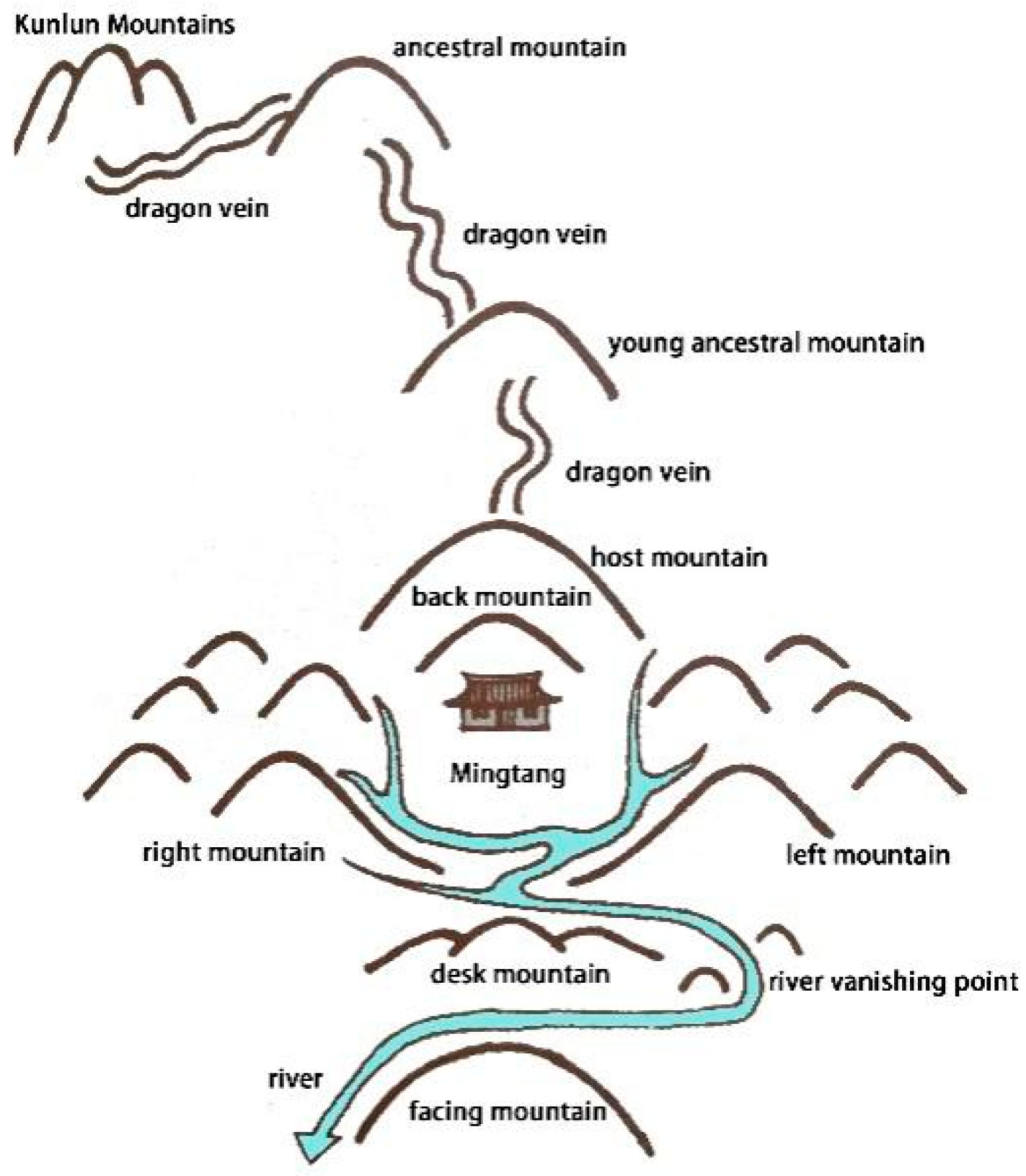

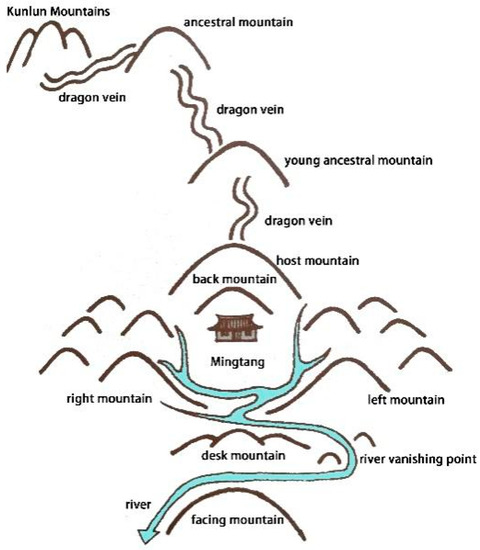

Feng-shui traditions are most prevalent in Guangdong and Fujian provinces within China. Based on interviews conducted with local residents, the building site, orientation, shape, and other aspects of tulou are typically determined according to traditional Chinese architectural planning theory, which is grounded in Feng-shui principles.

According to the principles of Feng-shui, an ideal house location should be backed by a continuous mountain range with a dragon vein passing through the ancestral mountain and young ancestral mountain before reaching the host and back mountains, while the building itself should be situated at the foot of the back mountain. The site should also be flanked by mountains on both the left and right sides. Additionally, the river should gracefully wind around the front of the house, providing irrigation to the expansive and fertile Mingtang. The Mingtang serves as a vital resource for agriculture. Furthermore, there ought to be a gentle hill (desk mountain) in proximity to the house, so that the river can meander leisurely and nourish the land instead of rushing downstream. Within the line of sight, it should face towards the facing mountain to create an opposite scenery and establish a stable geographical environment around it (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Optimal location for a house based on Feng-shui principles.

Based on the survey, it is uncommon for tulou to fully adhere to the ideal geomantic pattern, particularly in terms of meeting the mountains of varying heights in the four cardinal directions simultaneously. In contrast, proximity to a river and an open Ming Hall are common characteristics in the site selection of tulou, as they are essential prerequisites for agricultural activities and habitation.

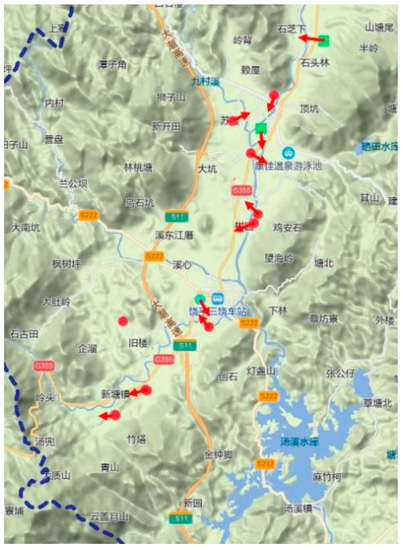

Shangrao and Jiangrao towns are both located in a mountainous region. Shangrao town boasts nine tulou along the Bajun Creek, with elevations ranging from 240 to 470 m. Due to the narrow valley, eight of these tulou face towards it in order to provide a wider view and larger Mingtang, while only Chaoyuan Lou faces the river directly. In Jiangrao town, there are a total of seven measured tulou with elevations ranging from 187 to 439 m. Out of these, five face towards the direction of the valley, while the two middle ones face towards the mountains (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Tulou along Baijun Creek of Shangrao Town.

The Huanggang River, the largest river in Raoping County, features an open and flat valley with low elevation. Tulou along the upstream river are predominantly oriented towards the waterway (Figure 7). In the middle reaches of the Huanggang River, the tulou facing the open valley also face towards the river, while those situated in the narrower valley at its bend all face towards the valley (Figure 8). The above analysis reveals that the availability of arable land, expansive views, and easily accessible water sources are pivotal factors influencing the siting and orientation of tulou.

Figure 7.

Tulou along the upstream of the Huanggang River.

Figure 8.

Tulou in the middle reaches of Huanggang River.

5. Space Layout of Tulou

5.1. Overall Spatial Layout

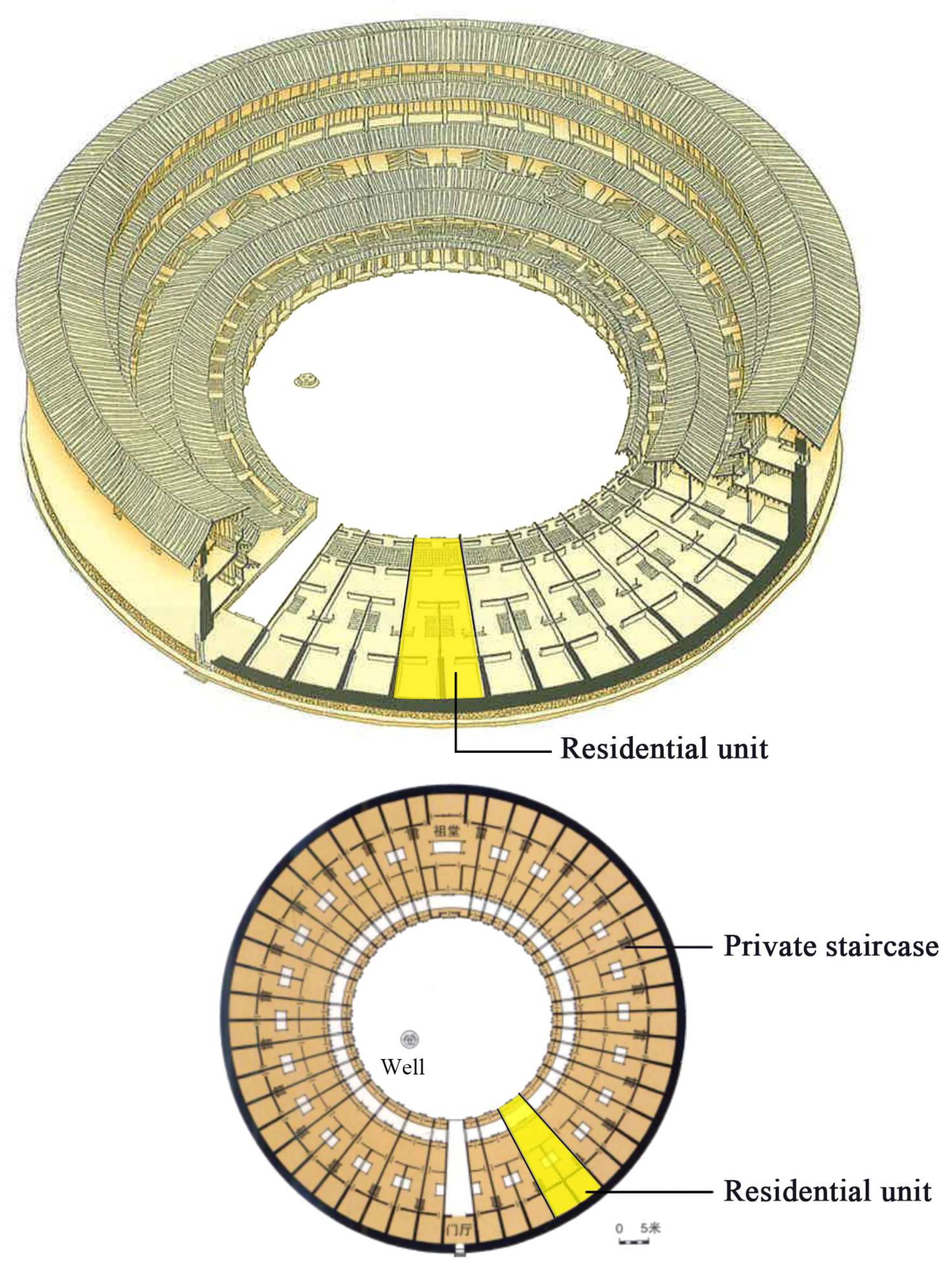

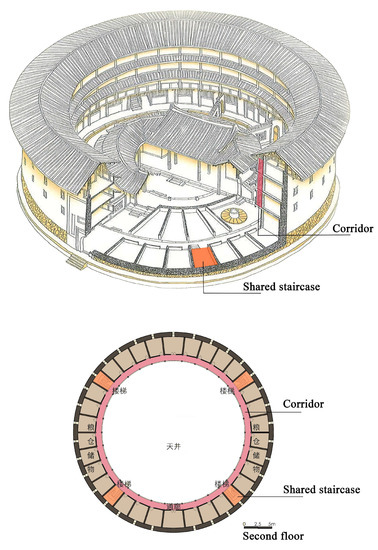

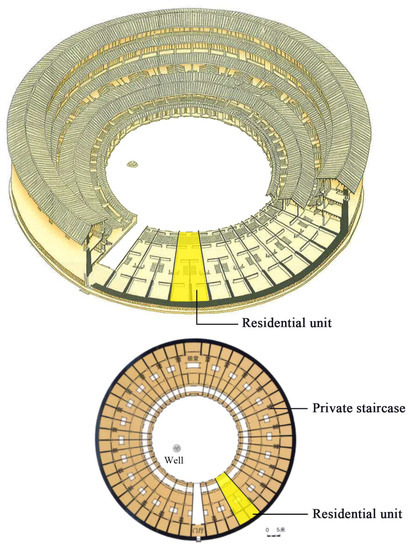

Although tulou display a variety of external appearances, such as circular, oval, square, octagonal, and half-moon shapes, their internal spatial layouts exhibit remarkable consistency. These layouts can be categorized into two distinct types in China: Hakka tulou and Minnan tulou. Hakka tulou is characterized by an inner corridor layout, where space is organized around circular corridors with multiple communal staircases (Figure 9). In contrast, Minnan tulou features a unit layout composed of identical, sequential residential units, each with its own separate entrance and private staircase that extends across all floors [19] (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Hakka Tulou—inner corridor layout (Huaiyuan Lou, Nanjing County, Fujian Province) 22, page 45.

Figure 10.

Minnan Tulou—unit layout (Longjian Lou, Pinghe County, Fujian Province) 22, page 50.

In both types, an equal amount of private space is allocated to each small family to maintain a harmonious collective life and demonstrate equality among family members. However, the two distribution methods have their respective pros and cons. In Hakka tulou, the rooms designated for each family are closely interwoven, fostering unity within the larger family. This arrangement encourages close family cooperation in overall maintenance and prevents arbitrary room sales among family members, reflecting a preference for sacrificing small-scale privacy for the benefit of larger families. In contrast, the Fulao tulou offers greater independence and privacy, creating more comfortable living conditions. Additionally, individuals can make independent decisions regarding the timing and selection of building materials for their housing construction based on their own family’s economic situation. However, this can make it challenging to collaborate on maintaining public affairs and prevent residents from converting, selling, or abandoning their units, which may not promote long-term family unity.

According to the field survey results, all tulou in Chaozhou use a unit layout. The residential units are separated by radial load-bearing walls constructed using pisè or adobe techniques, with floor purlins inserted into the middle and roof purlins placed on top of the walls. In Hakka tulou, rooms are distinguished by wooden frames and non-load-bearing adobe partitions. Thanks to the load-bearing walls in the longitudinal direction, each residential unit can be extended without restriction and accommodate more functions. For example, the residential unit may have a separate entrance hall, living room, semi-open yard and patio, and sometimes a private ancestor worship space—all shared by the big family in tulou with an inner corridor layout.

It is worth noting that the two types of tulou employ distinct external and internal scaling systems. When approaching a tulou, one is met with towering walls and a colossal structure in stark contrast to the human body, evoking a sense of self-insignificance. This external manifestation reflects tulou defensive nature, inspiring awe and conveying an unyielding invincibility that can create a sense of oppression—an effect of super-size. This external scale is meant to defend against external enemies. However, once inside the tulou, it becomes a completely different world where the scale system is centered around people: With unit widths of 2–4 m, delicate wooden doors and windows, appropriate heights, pleasant small scales, and friendly building materials all creating an ideal living environment for tulou residents. The extensive treatment of the exterior space contrasts with the intricate treatment of the interior space, which is a prominent feature and charm of tulou architectural spaces [20].

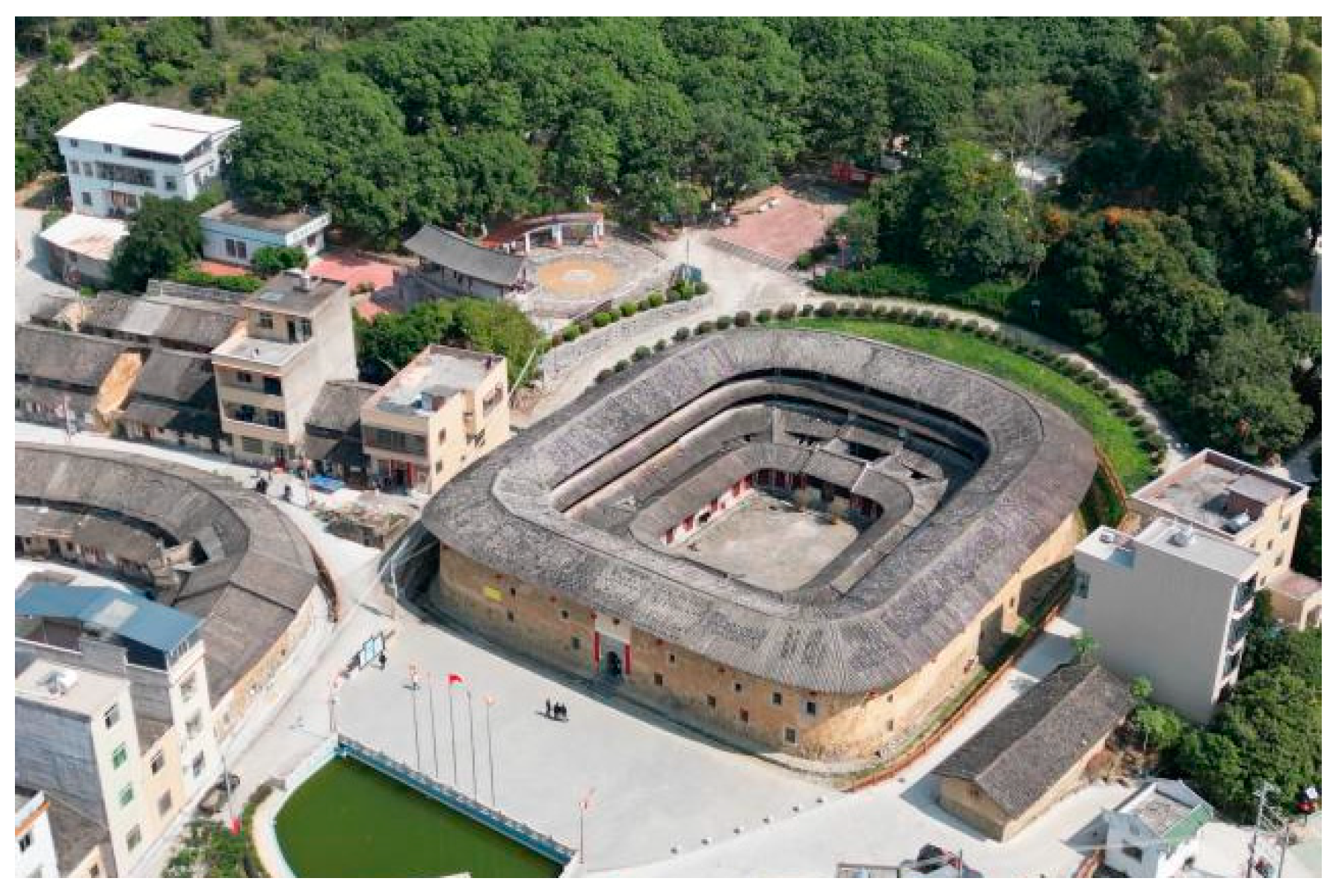

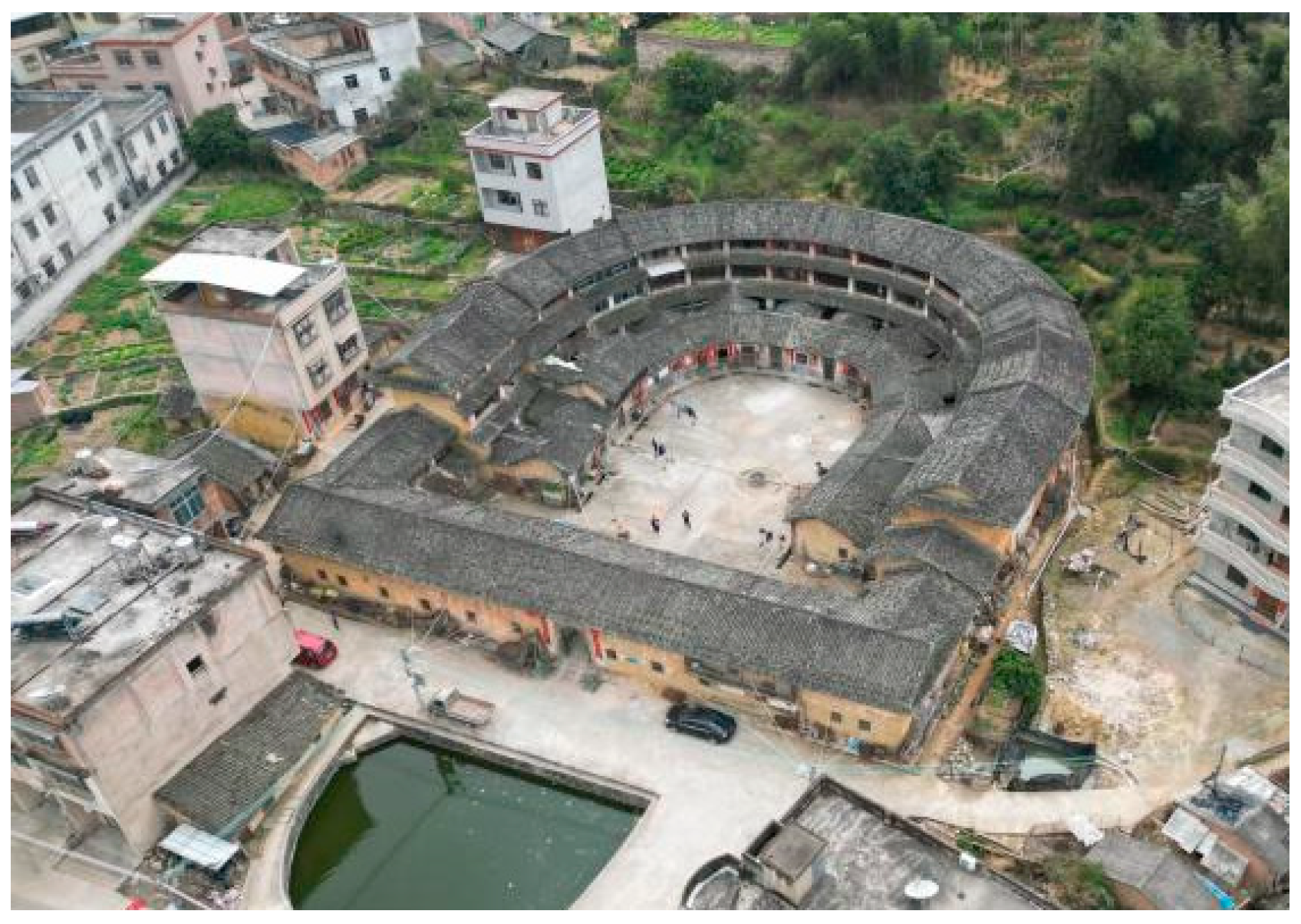

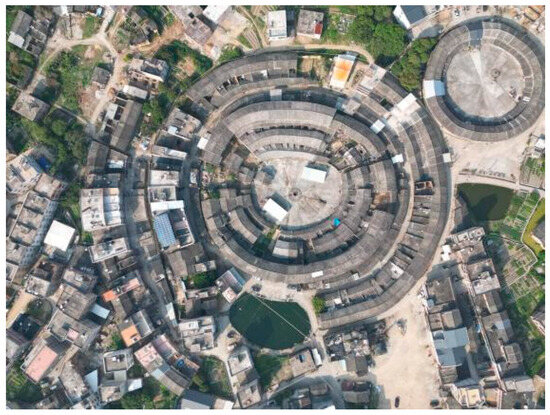

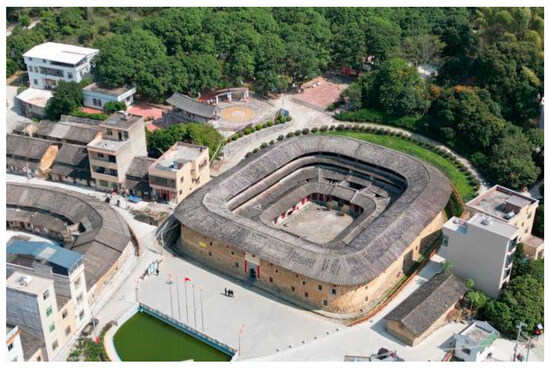

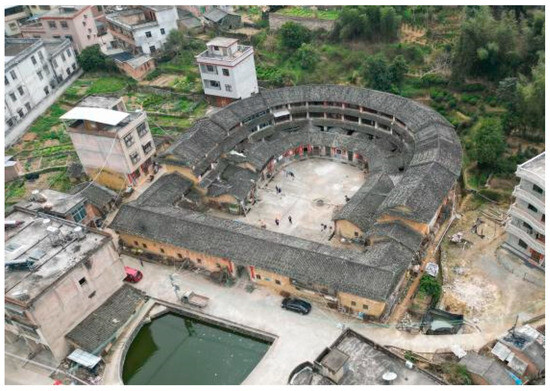

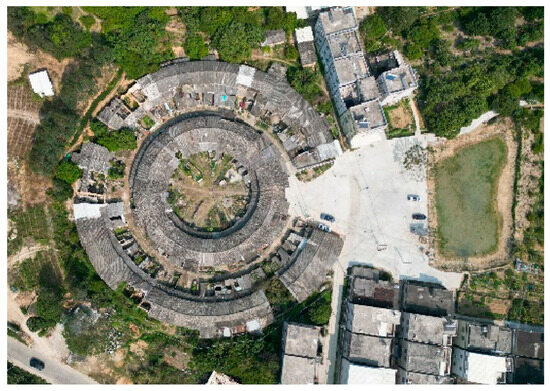

5.2. Shape and Scale

The sizes of Raoping tulou vary significantly, with the smallest ones covering an area of approximately 400 square meters, while the larger ones can span up to 7000 square meters. These tulou come in a variety of shapes, including round, oval, square, and horseshoe. Typically, they are two or three stories tall and house communities of around 150 to 400 individuals [21] (Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14).

Figure 11.

Zilai Lou in Zhangxi Town.

Figure 12.

Fuhai Lou in Shangrao Town.

Figure 13.

Taihua Lou in Raoyang Town.

Figure 14.

Hantian Lou in Dongshan Town.

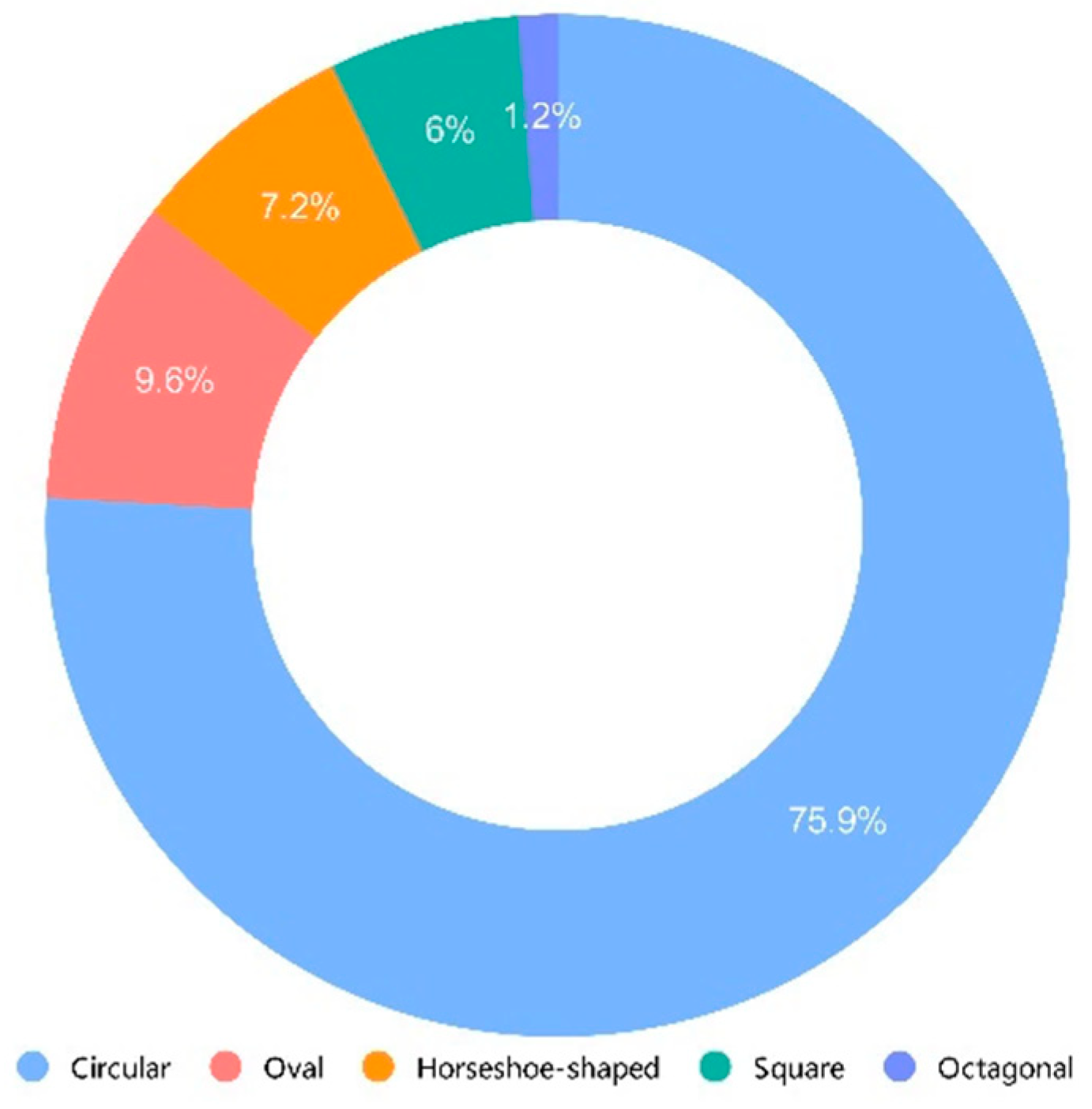

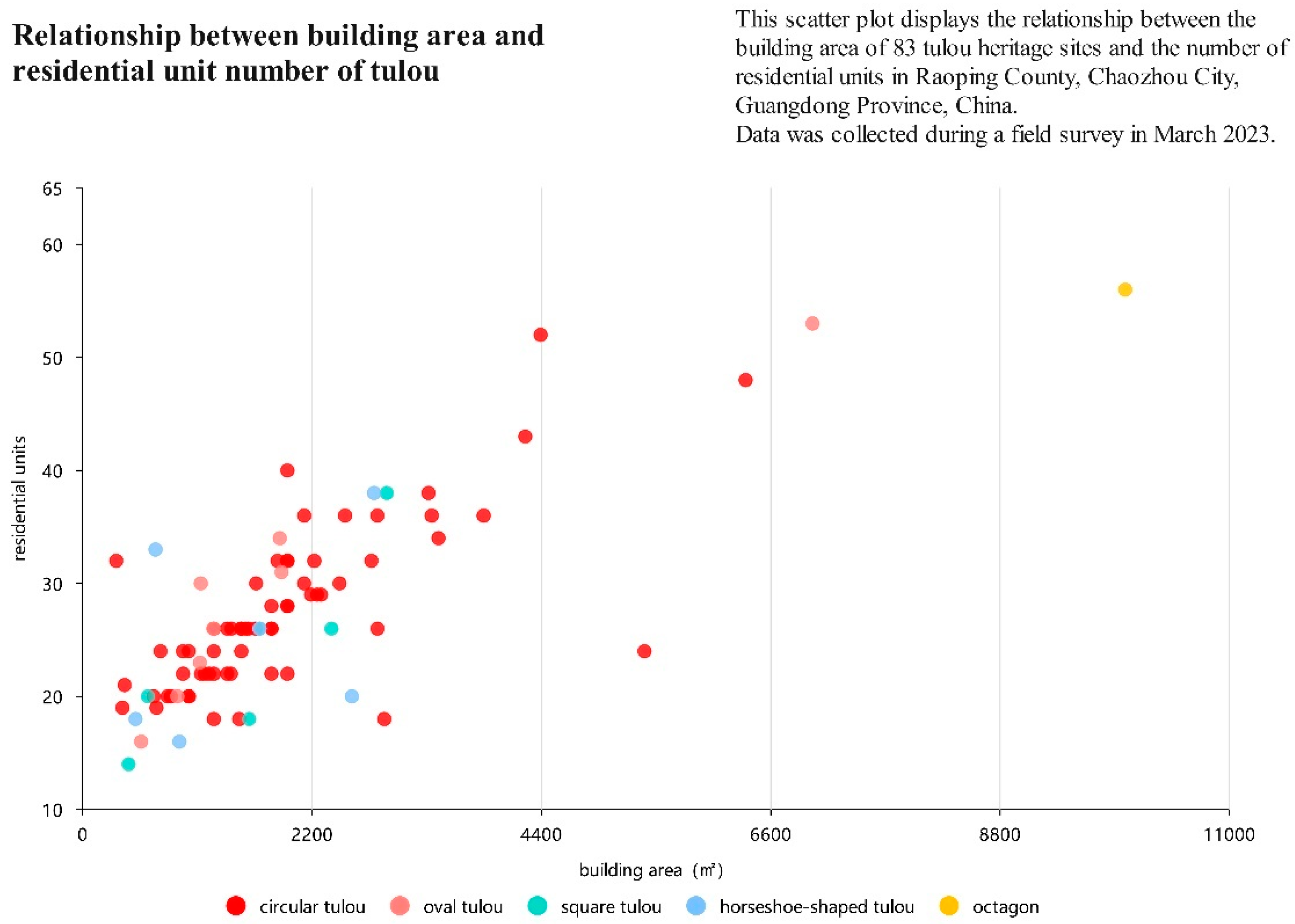

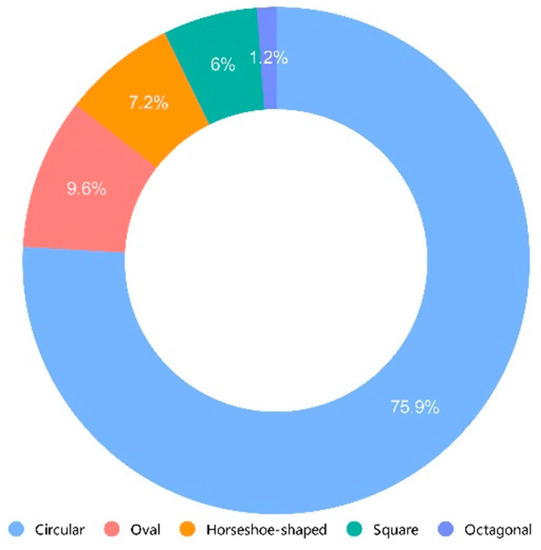

As illustrated in Figure 15, an analysis of 83 cases revealed that circular tulou were the most common, with 63 instances accounting for 75.90% of the total. Oval tulou were the second most prevalent, with eight instances (9.64%), followed by six horseshoe-shaped tulou (7.23%), five square tulou (6.02%), and one octagonal tulou.

Figure 15.

The distribution of tulou shapes.

Circular tulou come in a variety of sizes, ranging from ten meters to several hundred meters in diameter. In terms of their building area, 33 of them fall within the range of 1000 to 2000 square meters, representing 52.3% of the total. Additionally, 12 tulou have an area between 2000 and 3000 square meters (19%), 10 cover less than 1000 square meters (15.9%), and eight span more than 3000 square meters (12.7%).

The majority of circular tulou consist of 20 to 30 units, with 38 instances accounting for 60.3% of the total. There are also 16 tulou with 30 to 40 units (25.4%), five with 10 to 20 units (7.94%), and four with over 40 units (7.94%).

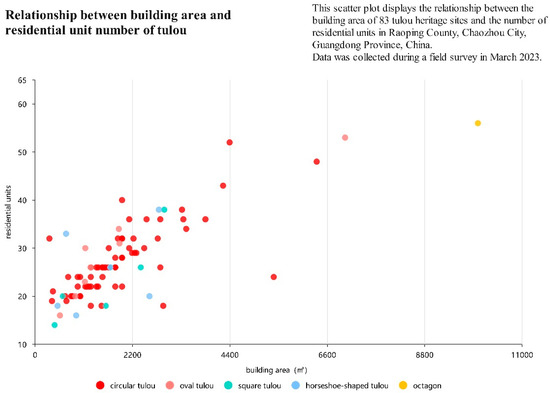

A comprehensive analysis of 83 Raoping tulou demonstrated that, regardless of their shape, the building area of these structures typically falls between 500 and 3000 square meters. Furthermore, each residential unit within a tulou has an average building area of approximately 70 square meters (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

The relationship between building area and residential unit number of tulou.

The circular shape of tulou has been a topic of discussion among scholars, with several theories proposed to explain this phenomenon. Some suggest that the circular shape is associated with wealth, as ancient copper coins were circular. Others argue that it represents the Chinese cultural belief in an “orbicular sky and square earth”, which is symbolized by circular tulou structures. There is also the view that the rounded shape avoids sharp angles that may create hostility towards neighbors or disrupt the surrounding environment.

The debate regarding whether tulou evolved from square to round or from round to square remains unresolved. Nevertheless, it is well established that the primary objective of tulou was to bolster the defensive capabilities of residential buildings. As shown inTable 1, the circular tulou, in particular, presents several advantages for defense, including a wider field of view and the absence of blind corners or areas susceptible to fire. Worth noting is that the fan-shaped design of each room within a circular tulou is in contrast to the “be horizontal and vertical” principles guiding traditional Chinese architecture. From a functional perspective, the fan-shaped design was found to have limitations in terms of its furnishing potential. After careful consideration of the pros and cons, it was decided that the circular building design would be more suitable. Table 1 illustrates several advantages of this design, including enhanced defense capability, structural stability, earthquake resistance, and cost effectiveness for construction and maintenance. These critical factors ultimately contributed to the selection of the circular building design [22].

Table 1.

Advantages of circular tulou.

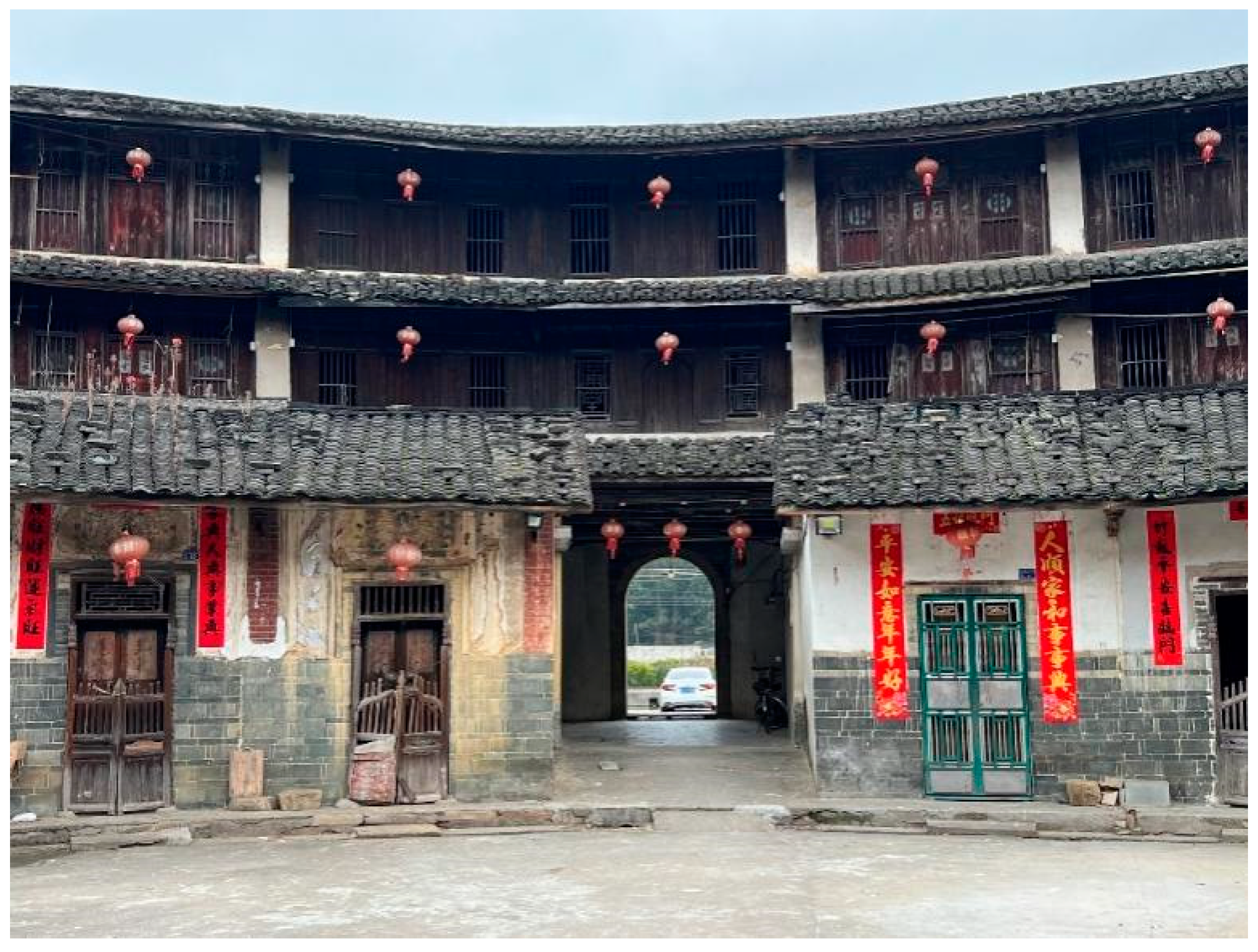

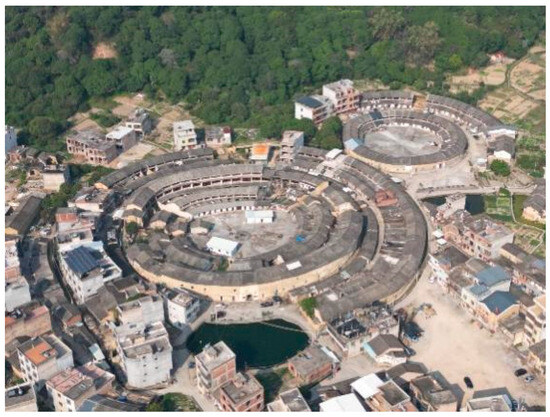

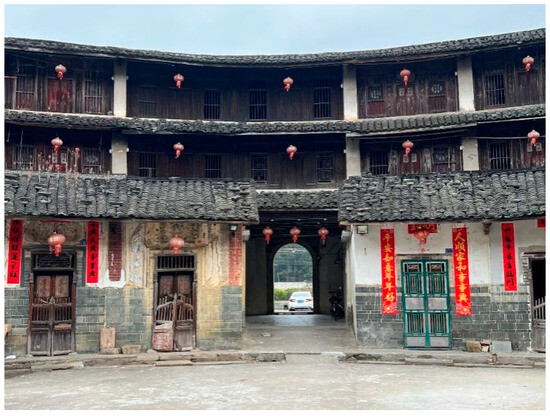

5.3. Lou Bao: Outer Ring Building of Tulou

Many Raoping tulou are accompanied by one or more outer rings of earthen buildings, locally known as “Lou Bao” (楼包), which were mostly built after the primary tulou. Loubao, like the principal tulou, feature a unit-based layout and rise 2–3 stories high (Figure 17). Encircling the central tulou, the Loubao breaks at its primary entrance, creating an entrance field referred to as “Wai Cheng” (外埕).

Figure 17.

Yangdong Lou in Dongshan Town.

The interior space of the primary tulou is highly compact, and after a few generations, it becomes too congested to support an entire family or clan. Constructing additional outer rings around the principal building has become a convenient and cost-effective strategy. Since small families may face varying circumstances when raising funds for another tulou, building units for the outer enclosure one by one is a practical and adaptable solution. This is an essential benefit of the unit-based layout of the tulou, as it demonstrates excellent adaptability in accommodating a growing household population with high derivative performance. Lou Bao units are typically preferred by residents since they are wider than those in the main building. This creates more spacious and comfortable living spaces, even though shared amenities such as a well and large interior courtyard are available in the central building (Figure 18).

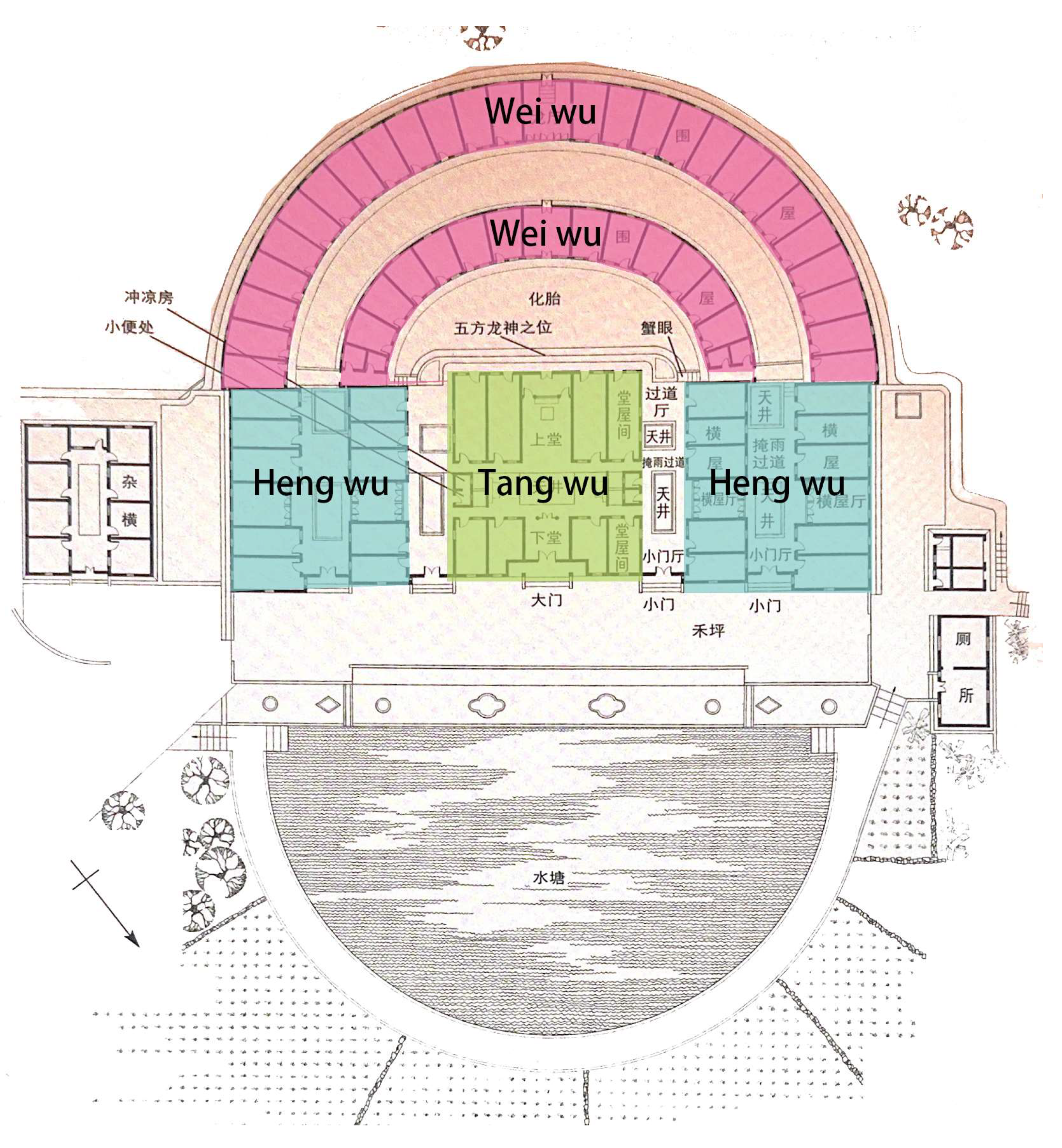

Figure 18.

Qingyang Lou in Shangrao Town.

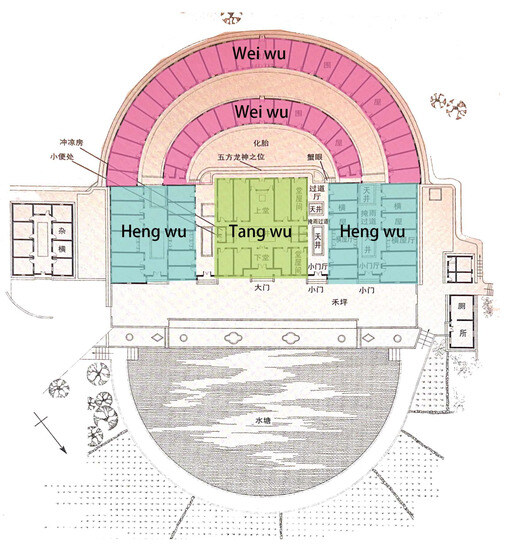

Adjacent to Raoping County, the Guangdong Hakka Cultural District features a prevalent residential architectural style known as “Wei Long House”. This architectural style is characterized by a central sequence of two or three halls, flanked by row houses named “Heng Wu” on the right and left sides and half-ring enclosure houses known as “Wei Wu” at the rear. The Dragon Hall, located at the center of Wei Wu, is where, according to Feng Shui theory, the mountain’s vital energy condenses. The Lou Bao buildings in Raoping tulou may have developed from “Wei Wu” and “Heng Wu” in the Hakka Wei Long House, as Lou Bao is rarely found in Fujian Hakka and Fulao tulou dwellings (Figure 19).

Figure 19.

Hakka Weiwu (Dexin Tang of Meizhou City) [24].

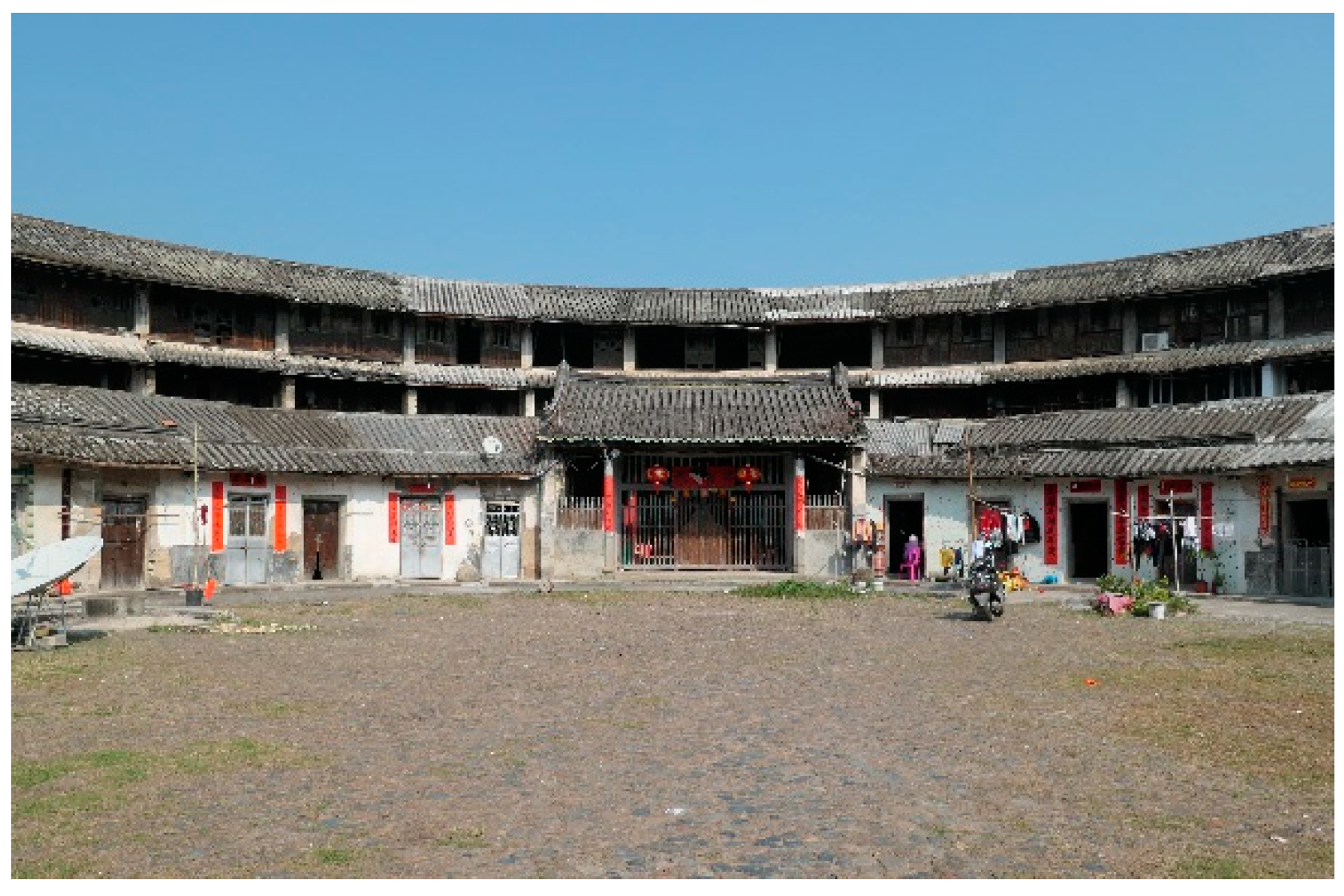

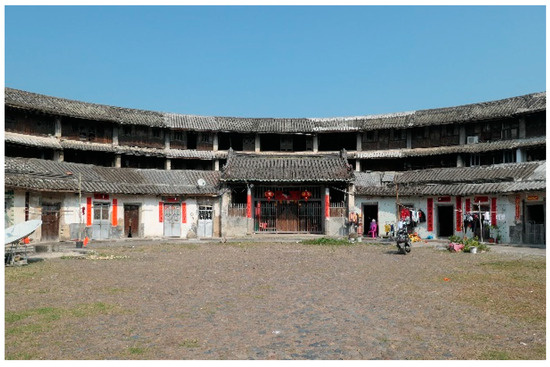

Tulou was once widely known as a fortified settlement with strong defensive capabilities. However, as Raoping tulou developed after the mid-Qing Dynasty and political and social stability prevailed, the defensive nature of tulou began to weaken, and living conditions improved. This is demonstrated by the construction of Lou Bao buildings with added balconies, although the overall form of tulou remained largely unchanged. Some defensive features common in Ming-era tulou were viewed as unnecessary and wasteful at the time, including a continuous gallery accessible from all residential units for effective defense organization and sighting balconies. Some tulou even lacked gates, being entirely open and facing the entrance field and half-moon pond (Figure 20).

Figure 20.

An ungated open tulou (Bei Lou in Dongshan Town).

Due to practical constraints imposed by rammed earth and adobe masonry construction materials, the placement of windows on the outer walls of the tulou is still limited to the top floor. Thus, openings cannot be too numerous or large. Moreover, traditional Chinese residential houses follow a “closed outside, open inside” tradition. For example, the famous “Beijing Si He Yuan” (四合院, courtyard house) does not have windows on the exterior walls. The villagers noted that the windows on the top floors of the tulou were scaled to meet their needs for transporting items (such as food and firewood) upstairs on pulleys, without mentioning their suitability for shooting.

Tulou dwellings evolved from a fortress for collective defense to an intensive settlement type adapted to the challenging terrain of mountainous regions with limited arable land. Consequently, tulou gradually shifted towards enhancing openness and comfort.

5.4. Public Space and Facilities

The public spaces of Raoping tulou primarily consist of the entrance field, commonly known as “Waicheng” (outer field), the spacious inner courtyard, referred to as “Neicheng” (inner field), and two significant units: The gate unit and the central axis unit opposite it. The gate unit is typically used for communal storage, while the central axis unit was traditionally utilized as a family ancestral hall for clan ancestor worship or a public hall for discussing family affairs. In cases where central axis units were used as ancestral halls, specific ones were widened to indicate a higher level of ritual importance than other residential units. A few ancestral temples are independently constructed within the inner courtyard of the tulou, frequently adopting the architectural style of standard ancestral temples rather than those found within tulou (Figure 21 and Figure 22).

Figure 21.

The ancestral hall unit located on the central axis (Wuquan Lou of Xinfeng Town).

Figure 22.

The ancestral hall alone in the center of Neicheng (in Double Luo village, Dongshan Town).

Public facilities primarily include ponds outside the gates and wells in the Neicheng. The pond serves as a firewater reserve and for fish farming. Villagers recall their past struggles with poverty when meat was rare except during the Spring Festival, when families would fish from the pond and cook together, filling the tulou with delicious food and deep affection.

The central area of tulou is a communal field typically paved with pebbles or gravel. This valuable open space serves as a hub for residents to carry out daily activities such as laundering and drying clothes, processing crops, and raising poultry and livestock such as chickens, ducks, and pigs. Additionally, it serves as an ideal location for hosting ceremonies and clan feasts during festivals or ancestral worship.

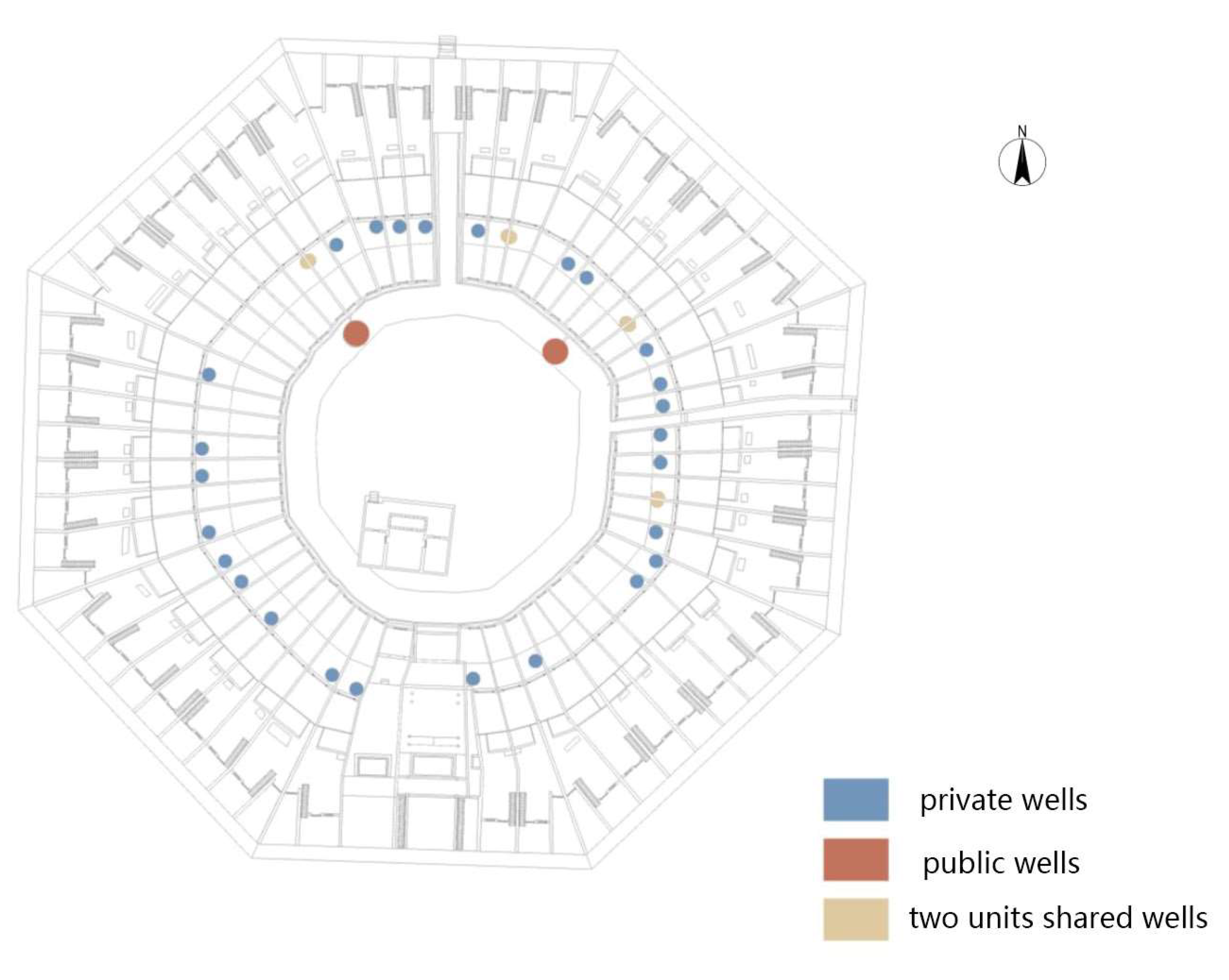

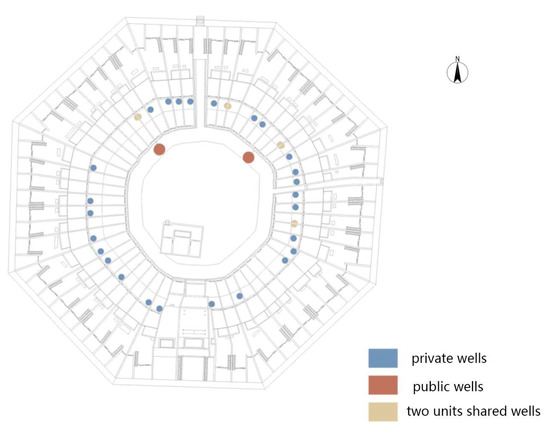

In Neicheng, it is common to find shared wells, with one or two typically present. Some residences also possess private wells, such as Daoyun Lou, which houses a total of 32 wells. These wells have an average inner diameter of approximately 51 cm and an outer diameter of around 95 cm. Among the 32 wells in Daoyun Lou, two are public, while the remaining 30 are privately owned. Of these private wells, 26 are located in the front courtyards between the foyer and mid-hall of each residential unit, while four can be found under the boundary walls of two units. Daoyun Lou was constructed in 1477 during the Chenghua period of the Ming Dynasty, a time of widespread Japanese pirate activity and public security turmoil. The abundance of wells in Daoyun Lou ensured a plentiful water supply for both domestic use and firefighting, even during times of attack or extended closure (Figure 23).

Figure 23.

Distribution of water wells in Daoyun Lou (in Sanyao Town).

6. Space Layout of Residential Unit

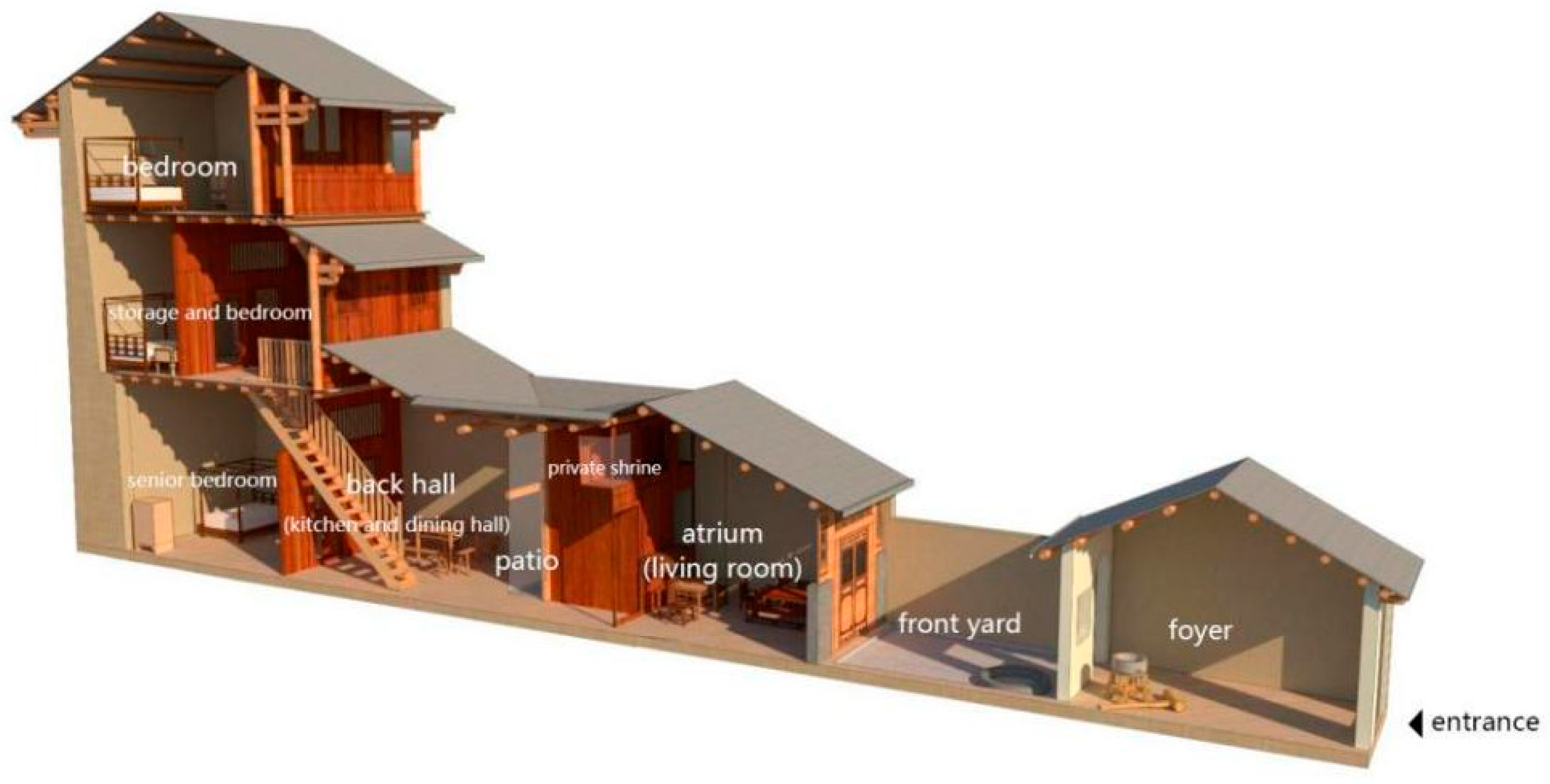

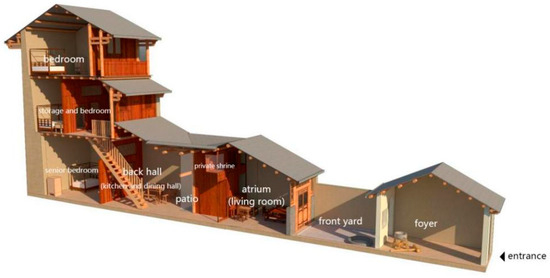

The residential units of Raoping tulou are divided by load-bearing walls made of pisé or adobe. Circumferential beams provide sufficient freedom in the depth direction by distributing the floor load from one load-bearing wall to another. Consequently, a residential unit typically encompasses a variety of domestic functions, including a foyer, living room, kitchen, dining room, storage, sleeping area, and occasionally, elevated shrines for sacrificial purposes (Figure 24).

Figure 24.

Space layout of a residential unit of Daoyun Lou in Sanrao Town.

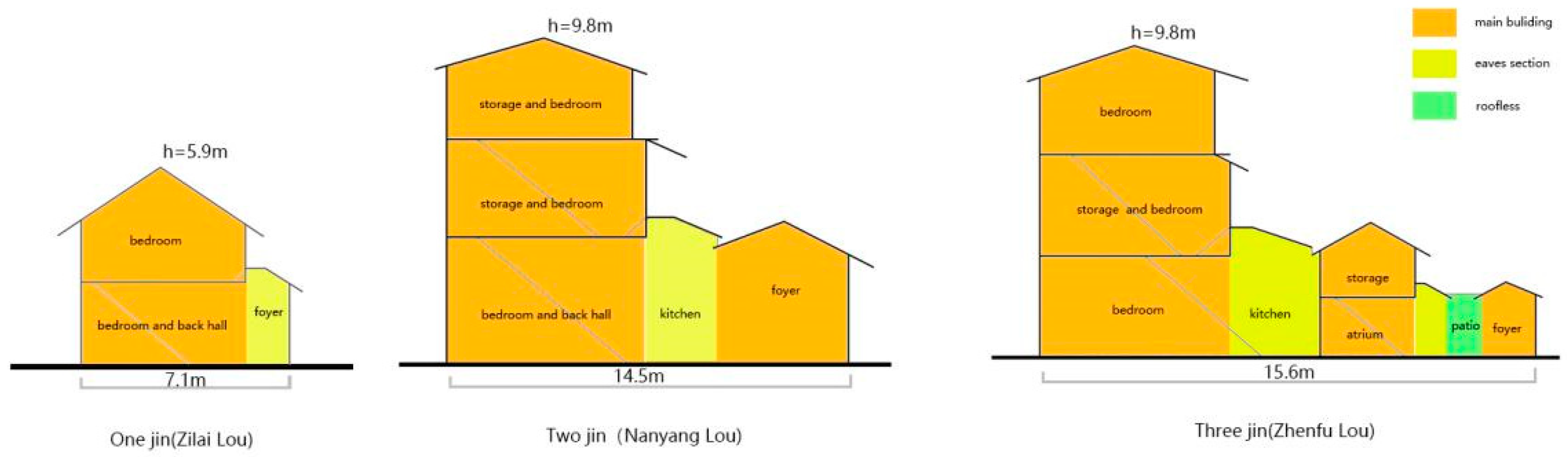

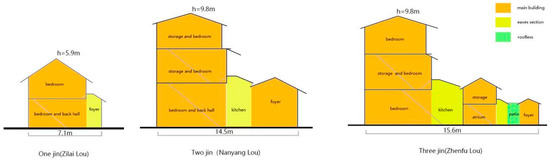

Tulou residential units can be classified into three types based on their spatial composition: One, two, and three “Jin”. “Jin” refers to a roofed space in the longitudinal direction of ancient Chinese architecture, separated from other “Jin” spaces by open areas, courtyards, or patios. The primary factor influencing the type of residential unit is the unit depth, which is determined by the size of the housing site and the available construction funds.

As the depth of living spaces increases, they become more spacious and comfortable. The most basic residential unit is the one-Jin type, which consists of a single room with a sloping eave. By extending the depth by three or four meters, a vestibule can be added, not only expanding the living area but also creating a skylight between its roof and the hall’s eaves for improved lighting. As the depth continues to increase, a small patio and sidewalk can be incorporated, with the front and rear halls opening up to the patio for enhanced ventilation and lighting. The latter two configurations belong to the two-Jin type. When the depth exceeds 12 m, a three-Jin residential unit can be formed, containing three interior spaces separated by a private courtyard and a patio (Figure 25).

Figure 25.

Space layout of residential units at varying depths.

The primary structures of Zilai Lou, Longgang Lou, and Huanan Lou are one-Jin tulou buildings with depths ranging from 7.0 to 7.5 m. The first floor is an open space without an inner courtyard or patio. These buildings vary in height. For example, Longgang Lou features a loft on the relatively higher ground floor, giving it a two-story exterior facade while having three stories inside, including an attic storage space. As residential dwellings, individuals may also undergo spatial transformations based on their evolving living needs and household economic conditions. The sloping entrance roof of the Huanan Lou residential unit was replaced with a concrete flat roof, creating a spacious terrace and enhancing daily convenience.

Two-Jin residential units are the most common type, differentiated from one-Jin units by the addition of a single-slope eave between the front and rear halls. Some incorporate narrow patios or courtyards where depth allows, and their height ranges from two to four stories.

As living spaces expand in depth, they can accommodate a three-Jin residential unit, which features a courtyard and patio or two patios. The average depth of a three-Jin unit is nearly 15 m, with the maximum depth found in “Daoyun Lou” reaching 25 m, and an impressive spatial sequence: Foyer–front yard–mid-hall–patio (sidewalk)–back hall. The front yard is spacious enough to house a private well. The generous depth and the presence of open spaces such as courtyards and patios allow for ample natural light and ventilation, significantly improving the quality of life.

Generally, the interior of a residential unit consists of a foyer, kitchen, living room, and elderly bedroom on the ground floor, with storage and bedrooms on the upper floors. The second floor is often used for grain storage, as the first floor tends to be damp and unsuitable for food storage. Since cooking is carried out over an open fire on the first floor, the second floor is elevated and relatively dry, making it less prone to insects and mildew.

Bedrooms on the second floor and above feature a wooden “door with side lights” window facing the spacious Neicheng. Outside this window, there is a small platform or corridor for drying crops. The layout of Raoping tulou adheres to the Chinese residential tradition of a “closed exterior, open interior” concept. The only small window is located on the uppermost floors, providing ventilation and serving as a lookout and shooting hole for defense purposes. Additionally, fixed pulleys are installed to transport goods upstairs for storage (Figure 26).

Figure 26.

The wooden “door with side lights” window on the second floor and above (Chaoyuan Lou of Shangrao Town).

7. Conclusions

Raoping tulou showcase a distinct local character, catering to both the physical and spiritual needs of its communities. It holds significant heritage value as an outstanding example of residential architecture in South China and a remarkable representation of earth architecture worldwide [25]. Initially, the unique shape of the building attracted attention, but in recent years, its design ingenuity as a vernacular dwelling constructed and inhabited collectively, along with its ecological construction technology utilizing local resources such as earth, cobblestone, and timber with minimal energy expenditure while harmonizing with the surrounding landscape, has gained increasing recognition. However, with the advancement of the economy and industrialization, tulou have experienced a significant decline due to abandonment, improper reinforcement, spatial transformation, material replacement, and other factors. The local government has actively implemented various strategies for the sustainable development of tulou, aiming to safeguard the architectural heritage and its associated value cognition while simultaneously meeting the living needs of individuals to the greatest extent possible.

Commissioned by the Raoping County government of Chaozhou City, the team conducted a comprehensive investigation into Raoping tulou. Firstly, this paper carries out a comprehensive analysis of historical documents and local chronicles to reconstruct historical scenes. It systematically reveals the emergence, popularity, and consolidation process of tulou dwellings as integrated defensive and residential buildings for ordinary people, under the combined pressures of Japanese pirates and bandits, as well as the local government’s call for “small village merge into big ones”, “build fortresses”, and “train villagers”.

Secondly, through analyzing geographic information, this paper provides a comprehensive overview of the spatial distribution characteristics of Raoping tulou along the Huanggang River and its tributaries, as well as an analysis of the factors influencing their location and orientation: ample cultivated land (Mingtang), expansive vistas, and convenient access to water. Consequently, in wider valleys, the tulou tend to face directly towards the river, whereas in narrower valleys, they exhibit a preference for orientations facing the valley. Additionally, the study reveals the underlying reasons for the absence of tulou dwellings within 25 km of the coast by examining both the “Maritime Trade Ban” and “Coastal Evacuation Decree” issued during the Qing Dynasty.

Thirdly, Raoping County is home to both Hakka and Fulao people, with the former residing in the north and the latter in the south. However, a comprehensive analysis of Raoping tulou and its residential units reveals no fundamental differences between these two ethnic groups in terms of dwelling types and spatial layouts. Ethnic cultural characteristics are primarily reflected in architectural decorations and non-load-bearing wooden components, such as doors, windows, and railings. In fact, variations in scale, spatial layout, materials, and construction techniques of tulou are often determined by economic factors (building funds, land areas, geographical locations, etc.). This highlights the adaptability and flexibility of traditional residential structures.

Furthermore, the Loubao building in Raoping tulou is a rare example within Fujian Tulou, likely influenced by the “Wei Long Wu”, the predominant Hakka residence style found to the north of Raoping, and evolved from part of its “Wei Wu” and “Heng Wu”. This emphasizes the inclusive nature of traditional dwellings.

Fourthly, it is important to note that tulou residential buildings are not static, although few studies have mentioned this. Tulou constructed during the Ming Dynasty placed a greater emphasis on defense, featuring higher and thicker rammed earth walls, high-quality hardwood, and iron-clad doors measuring 10–15 cm in thickness, as well as corridors built on the top floor to connect living units for coordinated defense.

By the mid-Qing Dynasty, with the recovery of Taiwan and improved domestic security, the defensive nature of tulou had gradually diminished. Instead, people focused on enhancing their living conditions through various creative means, such as constructing wider and more convenient residential units on the outer circle of the original tulou rather than building new ones. Some tulou were built without gates, allowing the entrance field to connect with the inner field. Today, investigations reveal that it is common for residential units to install separate doors and windows on the rammed earth exterior walls of tulou to improve lighting and ventilation. This demonstrates the potential for development and residents’ initiative in traditional residential architecture. People will always actively modify their homes to meet their growing spiritual and material needs, in accordance with their financial capabilities. This not only presents an intriguing aspect of residential architecture but also poses an inevitable challenge in preserving the heritage of residential architecture.

In the future, on the one and, we plan to systematically analyze the architectural characteristics and construction technologies of Raoping Tulou. Our goal is to inherit the wisdom passed down from generation to generation and explore its potential in realizing ecological harmony and sustainable development of architecture. We also aim to rethink the modern application of this ancient construction technique for future development.

On the other hand, we aim to thoroughly examine and summarize the preservation status and damage mechanism of Raoping Tulou. This will enable us to fully tap into their potential for multiple functions, for the original function currently cannot comprehensively support people’s higher quality of life and lead to an increase in rebuilding and renovation [26]. In the current social context, actively exploring the protection and inheritance mechanisms of tulou is an extremely critical and urgent task. Simultaneously, we must endeavor to re-establish a strong connection between the tulou heritage and contemporary communities in order to transform it from being solely a relic of the elderly into a collective memory for all.

Author Contributions

D.C. fieldwork, methodology, research and analysis, project administration, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; J.S. fieldwork, research and analysis; J.Y. fieldwork, research and analysis, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52108007); the Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Guangdong Province (No. GD21YYS04); and the Basic Research Planning Project of Guangzhou City (No. 2023A04J0981).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere thanks to the editors of this journal for a rigorous process and the significant contribution of the anonymous reviewers, which have produced a better article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bernardo, G.; Guida, A.; Pacente, G. The sustainability of raw earth: An ancient technology to be rediscovered. J. Archit. Conserv. 2022, 28, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, J. Science and Civilisation in China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1990; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Q.; Xiao, D.; Ma, J.; Tao, J. Using graphic comparison to explore the dynamic relationship between social conflicts and Fujian Defense-Dwellings in China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2021, 21, 2285–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porretta, P.; Pallottino, E.; Colafranceschi, E. Minnan and Hakka Tulou. Functional, Typological and Construction Features of the Rammed Earth Dwellings of Fujian (China). Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2022, 16, 899–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, R.G. China’s Old Dwellings; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2000; p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Dong, S. Impact of ethnic migration on the form of settlement: A case study of Tulou of South Fujian and the Hakkas. J. Landsc. Res. 2015, 7, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Yang, C.; Li, J. The Regeneration Path of Historical Buildings and Environment under the Concept of Community Building: Taking Fujian Qingpu TulouCultural Center as an Example. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 37, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Vegas, F.; Mileto, C.; Escobar, A.H.; de Miguel, M.L. Sustainability, Risks and Resilience of Vernacular Architecture. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2022, 16, 817–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, P. (Ed.) Chaoshan Folk Houses (潮州民居); South China University of Technology Press: Guangzhou, China, 2013; p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Jing Is an Associate Professor in the Department of Architecture at Wuhan University, Public Lecture. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/Px493kFcVjFOCEDdCx913Q (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Taizu Records of Ming, Taiwan, School of History and Language; Taipei Academy of Central Studies: Taipei, Taiwan, 1962; Volume 70, pp. 139+159+205.

- Chen, T.; Zhi, D. (Eds.) Annals of Dongli Peninsula; Xiangqiao Wenxing Printing Factory: Chaozhou, China, 2001; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. The Emperor of the Heavy Gate—The Transformation of the Guangdong Coastal Defense System in Ming Dynasty (重门之御—明代广东海防体制的转变); Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2017; p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. (Ed.) Tanghu Liu Gongyu Wobao Stele Inscription (塘湖刘公御倭保障碑记); History of Chaoshan Cultural Relics (Part 1) (潮汕文物志 上); Shantou Cultural Relics Administration Committee Office: Shantou, China, 1985; Volume I, p. 335. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Xi Yuan Wen Jian Lu (西园闻见录); Harvard Yanjing Xueshe: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 98, p. 3129. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z. The Village and the Country: The Traditional Society of Fujian and Taiwan in a Multi Perspective (乡族与国家—多元视野中的闽台传统社会); Sanlian Bookstore: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, M. Lineage Organization in Southeastern China; Athlone Press: London, UK, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. From “Japanese pirates rebellion” to “moving off the sea”—Local unrest and rural social changes in Chaozhou at the end of Ming and early Qing (从“倭乱”到“迁海”—明末清初潮州地方动乱与乡村社会变迁). In Treatises of Ming and Qing Dynasty (明清论丛); Forbidden City Press: Beijing, China, 2001; Volume 2, p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H. Fujian Tulou, Treasures of Traditional Chinese Dwellings; Yang, Y., Translator; SDX Joint Publishing Company: Beijing, China, 2009; Chapter 4. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H. Fujian Tulou: A Treasure of China’s Traditional Dwellings (福建土楼: 中国传统民居的瑰宝(修订版)), Revised ed.; Life-Reading-New Knowledge Sanlian Bookstore: Shanghai, China; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; p. 261. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G.; He, J.; Hu, D.; Lin, Y.; Jian, W.; Chang, H. Fujian Tulou; Print. Rep. no. 1113:4; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. National Treasure: Eryi Lou and Hua’an Earth Building Group (国之瑰宝—二宜楼和华安大地土楼群). Huazhong Archit. 2007, 25, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.L.; Yan, X.C.; Yu, P.Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, G.F.; He, W. Seismic resistance of timber frames with mud and stone infill walls in a chinese traditional village dwelling. Buildings 2021, 11, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, Q. Mei Xian San Cun (梅县三村); Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2007; p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Frangedaki, E.; Gao, X.; Lagaros, N.D.; Briseghella, B.; Marano, G.C.; Sargentis, G.F.; Meimaroglou, N. Fujian Tulou Rammed Earth Structures: Optimizing Restoration Techniques Through Participatory Design and Collective Practices. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 44, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, E.W.M.; Zhang, F.; Ho, J.K.C. Effectiveness and advancements of heritage revitalizations on community planning: Case studies in Hong Kong. Buildings 2022, 12, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).