1. Introduction

The fields of sociology, economics, political science, and psychology had once been particles of one integrated field. However, the consistent division of labor across social sciences generated a structural mechanism of intellectual schisms. Former documented research exemplified the notion of the extensive division of labor and its tremendous impact on the intellectual formation of the intellectual boundaries [

1].

Since the mid-twentieth century, sociologists have shown a rigorous research interest in exploring, describing and explaining the intellectual division within the sociological field [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Early studies on the intellectual space of sociology identified the structure of topical divisions determining the intellectual pluralism of the discipline. More recent studies attributed the fractures of the field based on differences in epistemological and methodological styles [

1]. Most scholars provided conceptual—rather than empirical— approaches on the issue, debating over factors of knowledge generation mechanisms, while a few used empirical models, mapping the intellectual space of their discipline. A few scholars focused on co-authorship networks [

3,

4], while others focused on the associational affiliations and professional memberships [

9,

10], and the content analysis of the mainstream academic journals describing the topical patterns based on which they detected the thematic structure of their sociological discipline [

11,

12,

13,

14]. They all employed different modes of knowledge production (i.e., academic journals, conference proceedings, etc.), identifying that such scholarly endeavors contribute to knowledge production. However, we must ask ourselves how the importance of journal articles theoretically is informed, and what are the institutional mechanisms that establish topical fields based on the negotiation of meaning.

In this paper, I first provide an overview of several vanguard scholarly works with an emphasis on the theoretical frameworks and methodological styles, examining the intellectual landscape and the knowledge frames in sociology [

1,

8,

9,

13,

14,

15]. Many scholars studied knowledge production mechanisms, as well as described the intellectual landscape of sociology and other disciplines with an emphasis on the content analysis of abstracts, articles, conference proceedings, and other intellectual commodities. However, most of such scholarly works analyzing the intellectual commodities have not provided a theoretical explanation regarding the intrinsic process of knowledge generation that is commodified by the production of articles. The significance and potential contribution of this paper is to initiate a discussion on the mechanisms of knowledge production through a conceptual glance.

Knowledge production is highly regulated in the generic academic domain. Yet, how can the institution of knowledge be modeled? How are the fields formed? What is the role of academic agency in that process? The purpose of this paper is to introduce a meta-theoretical synthesis informing us about the structures and processes of knowledge production. The proposed meta-theoretical scheme incorporates conceptual components of the institutional theory, field theory, and theory of practice. These three theoretical models can be incorporated in the detection of a conceptual continuum, revealing a transitional stage from the structuration of knowledge, to the agency of knowledge. Knowledge structuration can be seen as a highly regulated institution, in which fields act as independent organizations with distinct practices involved. Within these fields, the role of intellectual agency is observed among academicians’ shaping “communities of scholars.” Mohr’s and White’s [

16] institutional model is employed to describe the holistic domain of knowledge, exemplifying the linkages between the micro, meso and macro structures, while Bourdieu’s [

17] field theory provides the domain of the objectification of knowledge, where the independence of meaning serves a

priori leading to the formation of fields within the knowledge space. Finally, Wegner [

18] focuses on the micro-perspective focusing on the interaction, negotiation, and reification of meanings as a continuous process that reveal the fluidity of the meanings.

The synthesis of these three theoretical models are grounded on the scope of providing a three-level explanation of the formation of the institution of knowledge as a whole, the organization of knowledge frames into fields, and the process of negotiating an intra disciplinary esoteric approach on reifying meanings. For instance, within the domain of sociological disciplines, the knowledge production mechanism is structured by regulatory practices informed by the selection of epistemological selections (theoretical vs. methodological) across sociological schools of thought. Such practices involve the creation of academic journals as a mode of scholarly interaction favoring a specific epistemological selection. That is, the formation of organizational entities of knowledge production mechanisms in institutional settings occurs through the creation of fields; within such fields, the processes of knowledge generation are reified by the negotiation of meanings (i.e., epistemological selections) by scholars who form intellectual communities or camps.

Using a theoretical synthesis constituted by Mohr’s and White’s [

16] approach on how to model an institution, Bourdieu’s field theory, and Wegner’s theory of practice, my proposed theoretical scheme on sociological knowledge production is as follows:

(1) Conditioned by the structural arrangements formed by a generic institution of scientific knowledge [

16]]; (2) classified in fields based on selected practices [

17]; (3) established by communities of scholars who negotiate, reify, and produce meanings [

18].

2. Knowledge Frames

The classification of distinct scientific disciplines forms the institution of human knowledge. Auguste Comte [

19] in his early writings (1819–1828) described the internal mechanisms of the philosophical structure ordered into six scientific disciplines; (1) Mathematics, (2) Astronomy, (3) Terrestrial Physics, (4) Chemistry, (5) Physiology, and (6) Social physics (sociology). Since the establishment of sociology as a distinct scientific discipline, there has been a continuous process of specializations forming an

influx discipline. Bourdieu [

20] and Polanyi [

21] exemplified the competitive character of the scientific fields, and theoretically analyzed the factors arranging the disciplines in the academic market place.

Since its establishment, sociology has been a multifaceted discipline with interstitial intellectual tendencies [

1,

22]. Sociology is an established field of thematic specializations, subject to intellectual needs, social sources, and division of labor [

1,

23]. Various scholars have attempted to investigate the evolving structure of sociological thematic entities by employing different theoretical and methodological perspectives. Several vanguard theoretical and empirical models explored and described the structure of the discipline from the glance of associational memberships [

9,

10,

24]. Another group of scholars described the geography of sociological knowledge from a collaborative network approach, and a topic centrality perspective [

3,

4], while others focused on the emergence of institutional isomorphisms of the sociological thematic structure in global settings [

15,

23]. Findings of former research regarding the homomorphic or heteromorphic topic structures appeared to be controversial. From an institutional perspective, DiMaggio and Powell [

25] argued that the institutional pressures tend to increase the homogeneity of organizational structures in institutional environments. On the other hand, institutional knowledge could be often partitioned in the process of reification, shaping topic distinctions in the field.

The notion of topic structural deficiencies within the sociological discipline highlight the lack of cohesiveness and the limited degree of methodological and theoretical consensus examining identical social issues. There are several theoretical approaches which attempt to describe sociological thematic structures by highlighting the network of specialties. Cappell & Guterbock [

24] discussed four theoretical perspectives that explain factors contributing to the holistic structure of sociology: (1) ideational theory, (2) political–economic theory, (3) professional power theory, and (4) intellectual network circle/network theory. Ideational theory suggests that specialty structures are formed by the differentiation and integration of ideas [

24,

26]. Political–economic theory exemplifies a polarized group of specialties constituted by functional and critical sociologists [

8,

24] while professional power theory focuses on status, prestige, and classification among sociological researchers [

27,

28]. Finally, the intellectual circle/network theory suggests that co-specializations fabricate thematic diffusions in the discipline [

29,

30,

31,

32]. These factors—identified in the general framework discussed—are independent from internal factors shaping the intellectual landscape.

3. Social Conditioning of Knowledge

Institutional theory suggests that institutions are enduring mechanisms, arranging and consolidating social structures. Mohr and White [

16] argued that institutional practices establish linkages between micro, meso and macro structures. At any level (local or global), the institutional agents interact symbolically within a frame of arrangements producing material, and ideational cultures. This mechanism relies on the cultural interactions within the organizational substructures ensuring the functional role of the institutional constructs. Most research on institutional modeling utilizes network analysis techniques underlying cultural practices revealing the interaction between agents in the institutional space [

10,

16,

33]. Also, the use of network analysis has been a vanguard methodological approach to map the divides and linkages of cultural elements and structural domains in the institutional contexts [

3,

34]. Hence, one could argue that the methodological selections used for institutional analysis affirm the obscure role of institutional agency, where a consensus, or lack thereof, is a manifest factor contributing to the formation of the intellectual space of the field [

35].

Two reasonable questions can be posed at this point: (1) How does scientific knowledge form an institution, and (2) which arrangements hold the institution of knowledge together? Relying on the relational and duality model [

16], and the “new institutionalist” model [

36], the theoretical proposition of this paper focuses on the conceptual scheme of knowledge production, where agents (editors, reviewers, and authors of scholarly articles) interact and fabricate meanings (topics) based on epistemological and methodical approaches reflecting the global and local orders of knowledge; these together shape the holistic intellectual fabrication of knowledge.

The role of structure and agency is vital with respect to identifying the knowledge generation processes. Conceptualizing the modality of agency is a very challenging task. There have been numerous research papers describing the crucial role of agency on the formation of social institutions [

16,

36]. Besides their institutional role, agents develop unique styles that may be in accordance, or in contradiction to the institutional objectives. Fligstein [

36] argued that a “new institutionalist” approach explains the local orders based on the social skills of the agents acting within fields, domains, or games. Social skills are developed through social actions, and practices among the agents producing or reproducing local orders. The new institutional model focuses on styles serving the functional, or conflictual role of actors within an institution. This approach can be applied to describe the divides in the institution of knowledge where the agents contribute to the epistemological divisions across disciplines at micro, meso and macro levels with, sometimes, controversial approaches. Mohr and White [

16] argued that institutions can be described as systems establishing a connection of relational symbolic materials within fields. Such symbolic materials generate meanings, through which a mechanism of topics’ generation gives shape to the intellectual landscape of the disciplines. Therefore, following this perspective, the topical taxonomy in sociology is based on the hermeneutic capacity of the agents to identify the fluid knowledge generation practices derived from a model of structural relationality among other agents [

16]. Relationality can be described as a system of social networks detecting the position of actors, agents, or objects, whereby the structural core can be identified by role structures generated by networks of actors that could take the role of editors, reviewers, researchers, or professionals within a field.

Following Mohr’s and White’s theoretical model [

16], peer sociological journal articles can be seen as artifacts of agency forming the intellectual landscape within the field of sociology. Within scientific fields, authors, editors, and researchers form social networks, and produce sociological knowledge-based negotiating meanings.The production of meaning is formalized by topics of published works in mainstream sociological journals.

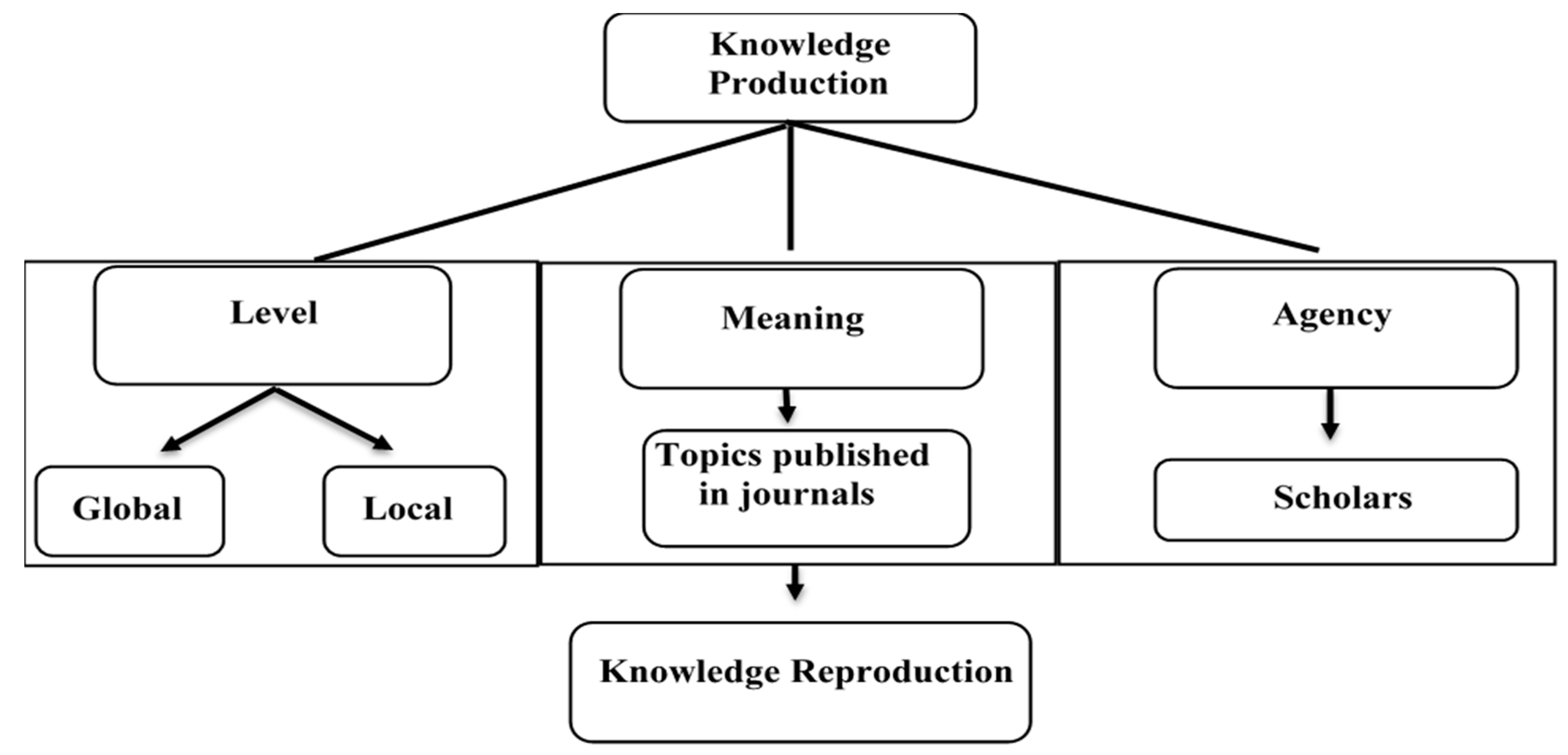

Figure 1 schematically presents the hierarchy and the interaction of agency, meaning, and level, forming the intellectual landscape of the sociological field within the institution of knowledge.

Conceptualizing the proposed theoretical scheme, I argue that, if we try to analyze from the institutional theory perspective, there are three dimensions contributing to the knowledge production processes: (1) the level at which knowledge is produced, (2) the meaning produced based on the cultural component (structured by the topics published in journals), and (3) the agency of the actors involved in the knowledge generation process. The first dimension, the level, identifies the terrain of knowledge production. Knowledge is produced at both local and global levels, and it can establish a continuum, but also, the ways of knowing (epistemology) can differ due to cultural diversity, ties to traditions, and authority. The second dimension, meaning, is a more complex factor of knowledge production. Consensus over meaning of conceptus is part of a negotiation of all parties involved. One way to detect and measure the degree of consensus is to compare the epistemological and methodological similarities as they appear in academic journals. Yet, there could be latent factors (i.e., research agendas, etc.) in that dimension that could be very difficult to detect (i.e., political agendas, personal interest, etc.). Finally, the decision over the topic preference is subject to agency, which is the third dimension of knowledge generation process. That is, the interaction of editors, reviewers, and researchers form the topical structure of the discipline, and they all contribute to the consolidation of meaning of topics (and concepts) that lead to knowledge reproduction. The topics preferred by the editors, reviewers, and researchers of established sociological journals at the local and global levels shape the intellectual landscape of sociology.

4. Fields and Practices

Constructing a single theoretical model explaining fields and practices is an extremely complex task due to the autonomous and interactive nature of institutions, fields, spaces, agents, and practices [

16]. Bourdieu’s field theory [

17,

37] exemplifies that fields and practices are inseparable theoretical elements defining social spaces. Pointing out the classification of fields and practice, one could argue that they are interdependent components ensuring the functionality of an institution [

38]. A continuum of interactions between institutions, agency, and practice, reproduce local orders within the macro structures [

36]. Following Ennis [

10] and Bourdieu [

17,

37] the sociological knowledge can be analyzed as a social field considering topical domains as distinct spaces divided by epistemological boundaries. The theoretical framework of field theory and practice substantiates the symbolic entities, so that ideas, meanings, and topics form communities acting as autonomous agents in a given institutional space. The categorization and distinction of knowledge have become far too schematic [

39]. It has been almost 50 years since Mauss considered all schools of thought as “fuzzy,” “futile,” and easily “transgressed” [

39]. The fields of knowledge are constructed by the dominant manifested ideas originated by an internal competition among the agents of knowledge production (professors, universities, scientific journals, etc.).

The process of communicating ideas and philosophies classify distinct communities of meaning within the boundaries of a field. That said, the process of meaning production distinguishes the frontiers of unique epistemological entities and draws boundaries based on the selection of methodological and theoretical orientations [

1]. The institutional mechanisms generating distinctive symbolic meanings are included in Bourdieu’s field theory. For Bourdieu, fields and practices (

praxis) are two inseparable elements forming grand theories

1. Fields are constituted by social spaces, or domains, in which agents are involved to a functional form of action (

praxis). The structural constructivist perspective explains their formation through individuals’ intrinsic consensus of taking action

(praxis). Shared mental images, common patterns of meanings assigned to linguistic terms, and identical perceptions on values, beliefs, and views over social artifacts are some characteristics of

habitus. That said, fields can be viewed as equivalent to institutional spaces, where the social positions of their agents are featured by “cultivated dispositions” [

41,

42]. Fields also refer to macro structures setting the

loci of social spaces. There are no formal rules within a field, but there is a set of practices and strategies internally inherited by the agents. Therefore, fields generate dynamic systems of expectations inherited by the agents who act based on the field-specific regulations [

37,

43]

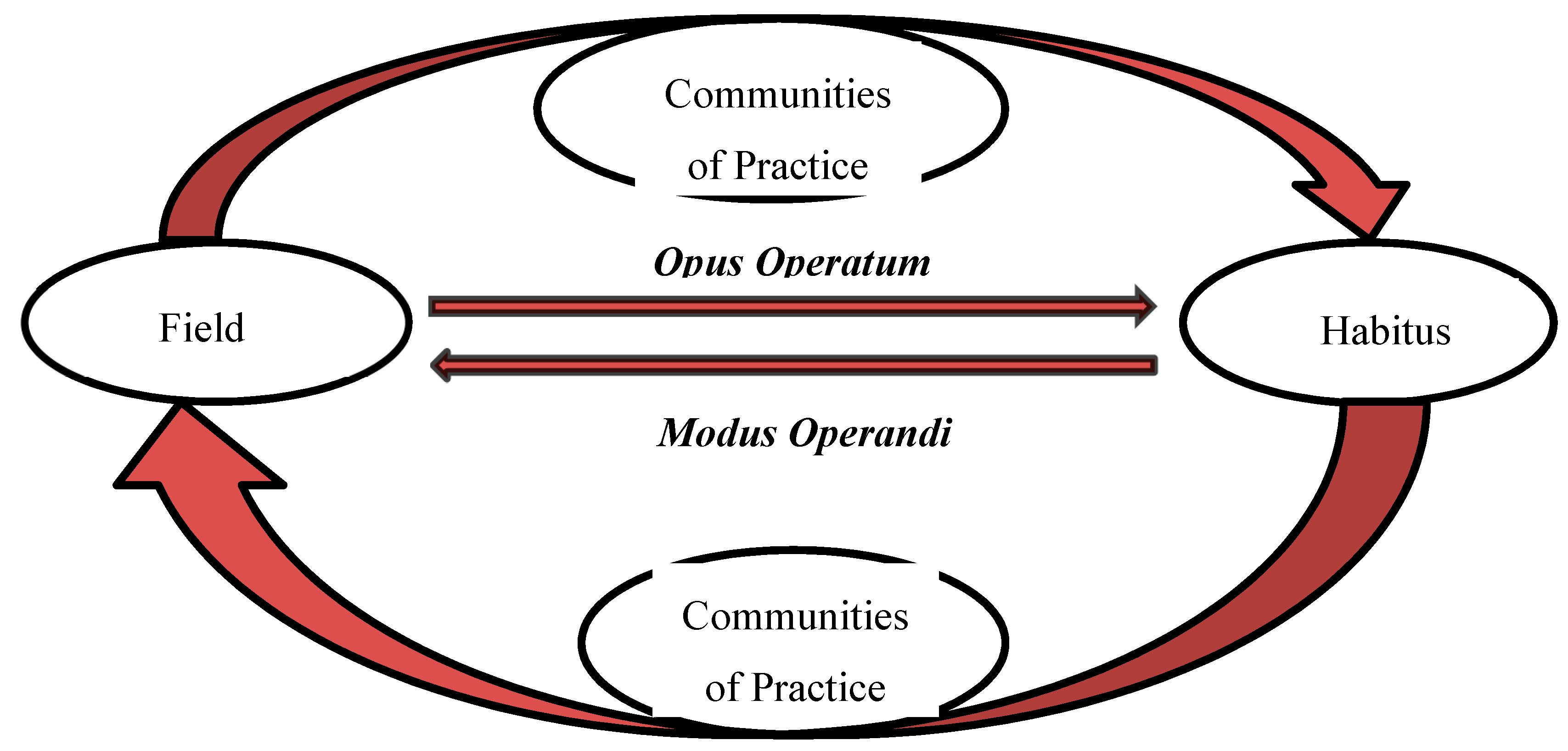

The dialectic between fields and practices is based on the interplay between

habitus and

fields. According to Bourdieu, there is a bi-directional relationship between

fields and the

habitus. The meaning of knowledge derived by

habitus can be approached as a product of

modus operandi (method of operation), while a field is the outcome of

opus operatum (work wrought). The interaction of the two form communities of practice that lead to the normalization of procedures, shaping fields in the domains of knowledge production mechanism (see

Figure 2).

The formation of a field begins with one fundamental rule; agents must act in their social space. The entire framework of actions is accumulated to a single conceptual term: practice (

praxis). In

Distinction, Bourdieu proposed a theoretical model where he denoted the association between field and practice. In simplistic terms, agents develop routinized activities dependent on the availability of resources and produce a symbolic system of shared meanings.

Habitus refers to the active role of the agent in the process of constructing a social reality through conceptual schemata, feelings, thoughts, verbal expressions of ideas, and practical manifestations [

37,

42,

44].

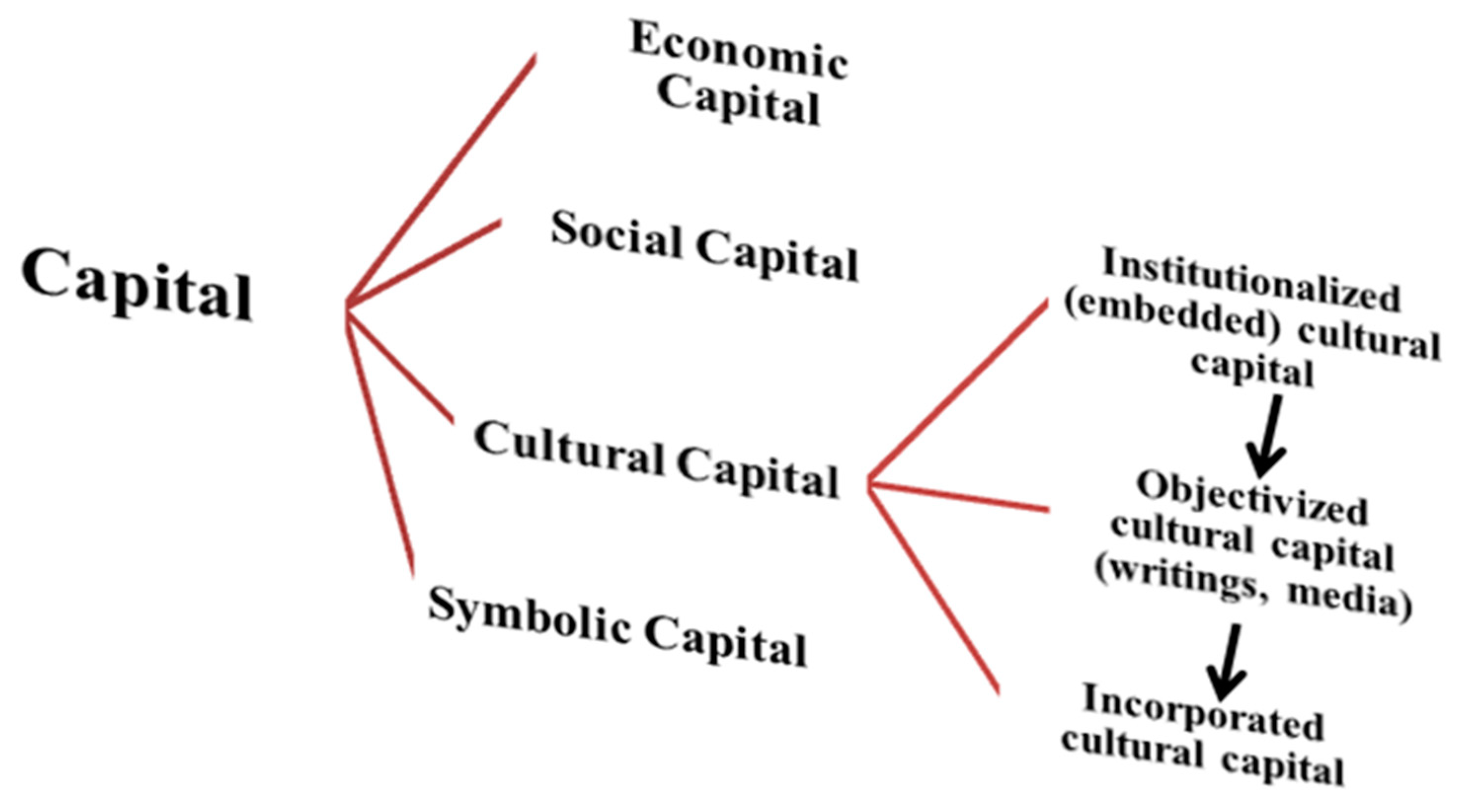

Figure 3 below graphically classifies Bourdieu’s forms of capital, with an emphasis on the cultural capital, where the institutionalized cultural (knowledge) capital generates objectivized forms of knowledge (i.e., journal articles) that results an incorporated mode of cultural capital.

Following Bourdieu’s theoretical assertions, scholarly works can be viewed as the artifacts of a routinized processes (habitus) of reifying concepts that generate consensual modes of knowledge (meanings). These are organized in structural thematic domains (fields), where the interplay between habitus and practice work as contributing factors in shaping fields of knowledge.

In the following section, I incorporate Wenger’s theoretical framework of communities of practice in Bourdieu’s field theory and theory of practice to expand the notion of generation, which is vital to explain the “institutionalized” knowledge production processes.

5. Communities of Scholars

Based on Wenger’s [

18] general theoretical scheme, scholars and social researchers publishing in academic journals form a community of practice. Communities of practice are created by the process of reifying ideas and concepts, and are transformed into frames of meanings derived by continuous interactions. The concept of meaning is a product of negotiation among agents, actors, and participants within a community. The process of negotiation of meaning is based on a “mechanical realization of a routine or a procedure” [

18]. The negotiation of meaning refers to the product of exchange of material and nonmaterial products. It consists of a continuous action, constant interaction, functional or conflictual interpretations, and gradual achievements. Although the negotiation of meaning applies to all modes of human interactions (i.e., language schemes, scripts, gestures, and social relations), for Wegner, there is no

priori meaning. For him, meaning is an elusive concept with high levels of abstraction evolving in intellectual spaces. In simplistic terms, meaning can be viewed as an intangible and socially constructed entity, which is then objectified by social artifacts or other types of human activity. The production of meaning is a result of a process of interchange between participation and reification. Participation is defined as an individual’s effort to take part and contribute to a collective (group) activity. According to Wenger [

18], part of human experience is to act and interact with others, and to engage in a series of collective activities. Participation requires membership, and consensual modes of comprehension, expression, and interpretation. In Bourdieu’s perspective, participation is a precondition of agency, where an individual, or a symbolic product becomes a member of a community construed by

habitus. The theoretical model of Wenger’s communities of practice implicitly refers to Bourdieu’s

practice and

habitus. For Wenger, participation is a dynamic process of negotiation of meaning. Therefore, Wenger’s approach on participation refers to a dynamic

habitus which constructs a meaning generation mechanism complemented by a process of reification of meaning.

Reification is the second crucial element forming the communities of practice. Wenger’s conceptual approach on reification refers to the “process giving form to experience by producing objects that congeal this experience into

thingness” [

18]. Via reification, abstract symbolic entities are transformed into tangible entities. The process involves an array of practices including encoding, decoding, interpreting, perceiving, and describing a situation, an idea or thought. The tangible outcome yields with the production of scripts, conversations, historical records, speeches, journal articles, and more. It forms consensual attributions based on an array of routinized practices. Having revisited Bourdieu’s theoretical framework and having applied the conceptual scheme of the communities of practice, I maintain that the two theoretical frameworks can be viewed as complementary and that they can be incorporated in the framework of the knowledge production explanation from the institutional theory perspective.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, I provided a meta-theoretical framework that discusses the knowledge frames produced within a broad spectrum of knowledge. I proposed a conceptual model based on a meta-theoretical synthesis of the institutional theory, field theory complemented by the theoretical scheme of the communities of practice I argued that frames contributing to the internal structuration of the sociological discipline is characterized by a procedural plurality that could be explained by a variety of theoretical niches and methodological styles that develop communities of scholars organized in diverse intellectual camps. Various approaches and explanations of social phenomena create knowledge frames that are subject to social conditioning on which, cultural production mechanisms are founded, established, and consolidated through a circuit of interactions of agents—via academic journals—within fields forming the communities of scholars.

Through the institutional model, sociological knowledge is informed by agency and is organized by structures. The process of participation in communities of practice constituted by a network of ideas published in academic journal articles denotes the continuum of agency and structures through a process of reification of meanings by the practice of knowledge. Within the communities of scholars, the notion of intellectual meaning is based on the expression of knowledge satisfying the condition of reification bringing intangible ideas into the realm of pragmatism. That is, the consensual form of meaning is created by cycles of participation and reification occurring in several domains of academic fields that all contribute to the holistic structuration of the institution of knowledge. The process of participation, negotiation and reification of meaning is justified by a range of professional and scholarly activities, while reification constitutes the symbolic entities specifying meanings and ideas forming fields with specified epistemological boundaries. Knowledge is organized by collective arrangements forming communities of scholars who belong to fields, producing central thematic entities published in academic journals sponsored by publishers, as well as by institutions of higher education. Further discussion on the conceptual niches could help describe the processes revealing the internal structuration of the field, detect the factors leading to the objectification of knowledge, and explore the internal dynamics of the meaning production mechanisms across different scholarly camps. Future research could help in detecting the applicability of this theoretical proposition by focusing on the description of the knowledge frames based on the epistemological preferences in local, national, and international settings.