Abstract

This purpose of this research is to understand the role of networked narratives in social media in modulating viewer prejudice toward ethnic neighborhoods. We designed experimental videos on YouTube based on intergroup contact theory and narrative frameworks aimed at (1) gaining knowledge, (2) reducing anxiety, and (3) fostering empathy. Despite consistent storytelling across the videos, we observed significant variations in viewer emotions, especially in replies to comments. We hypothesized that these discrepancies could be explained by the influence of the surrounding digital network on the narrative’s reception. Two-stage research was conducted to understand this phenomenon. First, automated emotion analysis on user comments was conducted to identify the varying emotions. Then, we explored contextual factors surrounding each video on YouTube, focusing on algorithmic curation inferred from traffic sources, region, and search keywords. Findings revealed that negative algorithmic curation and user interactivity result in overall negative viewer emotion, largely driven by video placement and recommendations. However, videos with higher traffic originating from viewers who had watched the storyteller’s other videos result in more positive sentiments and longer visits. This suggests that consistent exposure within the channel can foster more positive acceptance of cultural outgroups by building trust and reducing anxiety. There is the need, then, for storytellers to curate discussions to mitigate prejudice in digital contexts.

1. Introduction

Can digital media content reduce intergroup prejudice among ethnic groups, or does it exacerbate hate? This paper reports action research aimed at advancing empathy by creating videos about ethnic communities around the globe and subsequently analyzing how these videos affect viewers. Ethnic enclaves refer to neighborhoods or communities where a particular ethnic group is predominant and maintains its cultural identity. Despite efforts to maintain consistency and create a fair narrative across all featured ethnic enclaves in the videos, we found in practice that the nature of the platform significantly influenced audience perception [1,2,3].

The popularity of video-sharing social media platforms like YouTube has raised concerns about their inadvertent role in fostering prejudice and discrimination, particularly toward cultural outgroups [4]. These platforms, designed to capture attention, often unintentionally perpetuate biases by obscuring balanced and nuanced perspectives [5] and amplifying existing societal divisions, leading to increased animosity toward these groups. With recommendation algorithms, the platform design creates echo chambers and exposes users to divisive content, fueling intergroup prejudice and even hatred. By obscuring balanced and nuanced perspectives, these platforms may reinforce stereotypes and hinder the development of empathy and understanding between groups. This paradox highlights the need for strategies to reduce prejudice despite the unprecedented connectivity provided by social media [4,6].

To address this issue, we turn to intergroup contact theory by Allport [7] and Pettigrew and Tropp [8], who highlighted the importance of intergroup contact in mitigating prejudice, identifying three key mediators—knowledge, anxiety, and empathy—that contribute to reducing negative attitudes through intergroup contact. Knowledge gain helps dispel stereotypes and misconceptions about outgroups, anxiety reduction helps foster positive emotions and reduces fear of the unknown, and empathy development helps individuals understand and relate to the experiences and perspectives of outgroup members. Social media platforms like YouTube have become venues where users can experience closer intergroup contact with content through viewing and participation, gaining real-life experiences [9,10] and evoking a sense of shared experience and connection [11]. Such digital settings transcend physical interactions and manifest themselves in diverse ways as if experiencing direct contact firsthand [12]. This approach is often applied in vlogs and tourist videos on social platforms, captivating viewers and providing vicarious experiences through simply watching the videos [13,14]. In the context of intergroup contact theory, this contact on social media allows viewers to learn about different cultures and perspectives through the experiences of others, enabling emotionally charged, imagined contact [15], and fostering empathy and understanding.

Despite the potential for social media to facilitate positive intergroup contact, research on how video narratives can mitigate prejudice toward cultural outgroups remains limited. Existing studies often focus on the negative aspects of social media, such as its contribution to polarized perspectives, echo chambers, and the spread of misinformation, which can increase prejudice and discrimination [4,16]. Furthermore, experimental action research on the implementation of intergroup contact theory in digital contexts remains in short supply.

To bridge this gap, we began our research by exploring how video narratives on social media could be designed to address intergroup prejudice by incorporating elements that promote the key mediators identified by intergroup contact theory. We applied and adapted intergroup contact theory to design experimental videos within social media contexts, aiming to enhance positive intergroup contact by creating video content that embodies the principles of intergroup contact theory—knowledge gain, anxiety reduction, and empathy creation [8]. Knowledge gain is promoted by providing accurate and balanced information about the featured ethnic communities, anxiety reduction is facilitated by showcasing positive interactions and experiences, and empathy creation is encouraged by highlighting shared human experiences and emotions. These principles are incorporated into the video content to provide viewers with opportunities for vicarious participation and foster a sense of shared experience.

We have created a series of videos on a YouTube channel called “Ethnic Neighborhoods”, owned by one of the researchers. This video project began in 2017, with the aim of reducing prejudice toward ethnic communities through video narratives, particularly in the East Asian region, where issues of discrimination and prejudice have been prevalent [17,18]. By focusing on ethnic communities in this region, we aimed to address specific instances of intergroup tension and promote understanding and empathy. The videos, hosted by two presenters—one of whom is the lead researcher—showcase ethnic enclaves worldwide in a friendly and engaging manner. By sharing experiences of interacting with new cultures and people from cultural outgroups, the project believes indirect contact can lead to awareness toward the communities that are perceived as foreign. A consistent narrative format across our videos is maintained, featuring the same creators, filming style, editing, and storytelling composition.

Nevertheless, in applying intergroup contact theory through YouTube content, we have observed significant variation in user emotions expressed in the comments, despite consistency in our storytelling approach. When examining the most liked comments in practice, we noticed the top comments had different emotions and attitudes that varied according to where and how viewers encountered the content. These variations often originated from controversial discussions about the depicted ethnic groups. However, an underlying reason for these differences does seem to exist in that storytellers in our videos consistently focus on real-life representations of cultural outgroups.

This suggests that the narrative in today’s digital media is shaped not only by its content but also by the medium itself—how and by whom it is conveyed [19]. To understand the underlying theory, we looked into the concept of “networked narratives”, as explored by Kozinets et al. [20], which primarily focuses on the interplay between narrative content and the dynamics within online communities, particularly blogger–reader relationships and communal norms. However, in today’s context, further exploration is needed to understand the specific mechanisms at play and their impact on audience perception, as influenced by the design of the platform. As a result, we hypothesize that three key elements shape how content is influenced: algorithms, user interactions, and the video narrative itself [15]. We extend current networked narrative theory to include the influence of algorithms and user interactions on how the message is perceived [21].

To investigate the phenomenon, we conducted two-stage research using three videos from the “Ethnic Neighborhoods” series. The narrative structure of the three videos was controlled: all were filmed in the same African town in Guangzhou, China, during a single time period, featured identical narrators, and employed consistent editing styles and storytelling compositions. The sole variation among the videos was the featured ethnic group: Somalis, Congolese, or Uyghurs. These three cases were selected for their having particularly similar narrative design and region but distinctly different emotion and discrimination expressed by the viewers/[22,23].

The two-stage research approach was structured as follows:

- In Stage 1, automated emotion analysis using a Large Language Model (LLM) was employed to systematically assess the varying emotions expressed in the comments.

- In Stage 2, we conducted a qualitatively comparative case study by analyzing raw data from YouTube Studio. We examined types of videos suggested to the viewers, including suggestions appearing alongside or after the video, keywords searched, region of access, traffic, and viewing hours for each group. This analysis aimed to identify how the networked narratives affected users’ perceptions toward cultural outgroups.

These two stages provide an in-depth understanding of both emotional responses of viewers and the broader context of how the videos were presented and consumed on the platform.

The purpose of this research is to examine the role of networked narratives in shaping intergroup prejudice on social media platforms. We derived our insights from observations of varying emotional user responses, documented through an actual YouTube project initiated in 2017, which applied intergroup contact theory to video content. By investigating how prejudicial attitudes are formed and disseminated through the underlying mechanisms of networked narratives, this study aims to address the limited understanding of the interconnected nature of today’s media in relation to intergroup prejudice. We emphasize that research should not focus on a single mechanism but rather on the interplay of multiple factors within these networked environments.

We propose ways to mitigate the harmful effects of networked narratives and promote healthy intergroup contact, which refers to interactions that foster positive attitudes, reduce anxiety, and increase empathy between members of different groups, in line with the principles of intergroup contact theory. By identifying the causes of division in digital contexts, we aim to contribute to the development of effective interventions for prejudice reduction, advancing both intergroup contact theory and networked narrative theory.

Following this introduction, the chapter on theoretical background explores intergroup contact theory, the nature of digital media platforms, and networked narrative, laying the theoretical foundation for this research. Then, the section on materials and methodology describes the action research site—“Ethnic Neighborhoods”—and applies the theoretical framework to the narrative. Next, we present the design of our two-stage research, with each stage followed by its respective results. Finally, we discuss the insights and implications derived from the results, followed by the limitations of this study and suggestions for future research.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Intergroup Contact Theory

Intergroup contact theory emphasizes that interactions between individuals from diverse social, ethnic, or cultural groups can effectively reduce prejudice and foster positive intergroup attitudes [7,24,25,26]. Previous studies highlight the potential of these interactions to lessen prejudice and enhance intergroup relations, particularly through opportunities for friendship and meaningful engagement [8,27]. The concept of “contact” encompasses a wide range of interaction scenarios, settings, and conditions that aim to improve attitudes and relationships between groups [28,29]. Traditionally focusing on in-person interactions, intergroup contact theory has expanded to encompass digital media platforms, offering diverse forms of interaction [8,30]. In this paper, we define intergroup contact as interactions between individuals from different cultural backgrounds with the goal of reducing prejudice and fostering positive intergroup relationships.

Gordon Allport’s work, “The Nature of Prejudice”, emphasizes the role of intergroup contact in reducing prejudice [7,31]. He suggests that bringing individuals from diverse groups together under conditions of equal status and shared goals can foster cooperation, interaction, and even friendship, ultimately leading to reduced prejudice. The decategorization model builds on this, advocating for interactions that downplay social categories and promote individual rather than group-based interactions [32,33,34].

Pettigrew extends this concept with the idea of recategorization, where a unified group identity emerges as outgroup members feel connected, transforming them into an ingroup [24]. However, maintaining some group salience is seen as beneficial, particularly for minority groups, balancing interpersonal interaction with group identity [31,32]. The dual identity model addresses this by allowing individuals to retain their personal identities while also being part of a larger group, fostering a balanced identity that reduces prejudice [35,36]. In our attempt to find the key to reducing prejudice toward cultural outgroups, particularly for locals interacting with immigrants or refugees that have relocated to their neighborhood, creating decategorization and equal status among the members is important for empathy creation [7]. At the same time, we also value a sense of belonging within one’s ingroup as vital to counter relocation loneliness. Thus, our goal is to acknowledge the importance of having a sense of belonging in one’s existing ingroup, while encouraging understanding and respect for outgroup members. This approach aims to foster conditions for recategorization, bringing people together and developing a shared sense of identity.

2.1.1. Forms of Intergroup Contact

Building on the foundation of intergroup contact theory, it is essential to understand contact diversity in digital media environments. Intergroup contact takes various forms [37]: 1. direct, 2. indirect, 3. imagined, and 4. extended. For instance, direct contact involves face-to-face interaction with outgroup members, like friendships across different racial or cultural groups [7,28,38]. Indirect contact includes learning about interactions from secondary connections, without personal, direct interactions [12,38]. Imagined contact, a subset of indirect contact, entails visualizing positive interactions with outgroup members [39,40,41]. Extended contact involves friendships between ingroup and outgroup members, promoting cross-group relationships, especially where direct contact is limited [34].

Technological advancements have facilitated the integration of contact diversity within digital media environments [39]. Different forms of contact can create a sense of participation in the experience, influencing decision-making and encouraging individuals to engage with outgroups [9,10,14] and reduce prejudice [42]. In this paper, we acknowledge the role of video content in extending viewers’ experiences to include imagined contact through visualization and extended contact along a spectrum of parasocial to interpersonal relationships with the creators. As a result, we view intergroup contact as a dynamic and multifaceted phenomenon, encompassing various forms of interaction that occur concurrently within digital narratives and online communities.

2.1.2. Mediators of Intergroup Contact and Prejudice Reduction

Prejudice reduction is the ultimate goal of fostering positive intergroup contact through digital media, as it minimizes negative attitudes, stereotypes, and discriminatory behaviors toward individuals from different social, ethnic, or cultural groups [25,43]. The three key mediators—knowledge, anxiety, and empathy—work together to facilitate this process [8].

- Knowledge

Firstly, increasing knowledge about cultural outgroups helps to dispel myths, challenge stereotypes, and provides a more accurate understanding of diverse communities [44]. As Allport states, “Prejudgments become prejudices only if they are not reversible when exposed to new knowledge” [7]. Knowledge about cultural outgroups, gained from indirect to imagined experiences, like travel vlogs, is pivotal for awareness. With advancements in connectivity and content creation, such knowledge influences audience perceptions and trustworthiness [35]. Although less potent than anxiety reduction, knowledge remains crucial in dispelling fears and stereotypes about cultural outgroups [45,46]. In the narrative we embed, sharing the facts is crucial.

- Anxiety

Reducing anxiety associated with intergroup interactions is essential for building positive relationships and creating a more comfortable environment for engagement [8]. Anxiety in this context is defined as discomfort or apprehension during intergroup interactions, largely shaped by media narratives and stereotypes [47,48]. Mass media often portray ethnic communities negatively, frequently highlighting instances of hatred or mistreatment they face. This negative portrayal contributes to increased anxiety about intergroup contact, as much of the fear stems from uncertainty and apprehension toward unfamiliar cultural groups. Studies have shown that lower levels of contact lead to higher anxiety [44]. While initial contact with an outgroup can be challenging, perceptions can change through interaction. At the same time, we believe that the rise of personalized content on platforms presents opportunities to reduce such anxiety by offering nuanced cultural insights when content is curated effectively by the platform [5].

- Empathy

Finally, fostering empathy allows individuals to connect emotionally with others, share their experiences, and develop a deeper appreciation for their perspectives [49]. Empathy is closely interconnected with anxiety, as anxiety can affect one’s empathy toward a group [50]. It involves emotional congruence with others and a deep emotional bond [51]. The sense of feeling what others are experiencing as if it were one’s own [52,53] allows individuals to transcend the gap between differences, particularly among people from diverse backgrounds and experiences. This leads to deeper understanding, trust-building, and a reduction in conflicts, ultimately fostering a more inclusive world [8,25,46,54]. By cultivating these emotional connections, digital media have the potential to bridge cultural and social divides, enhancing global understanding and inclusivity.

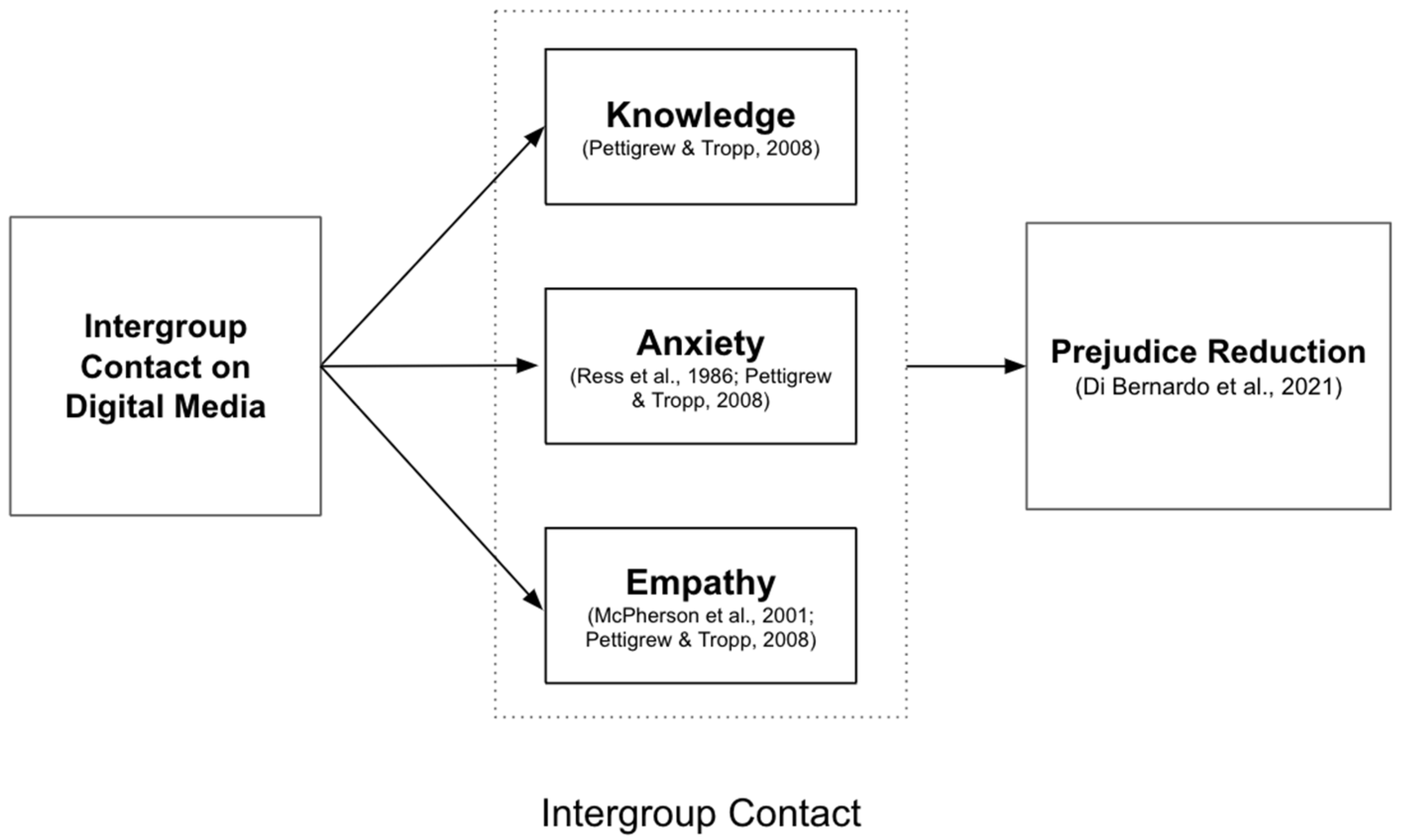

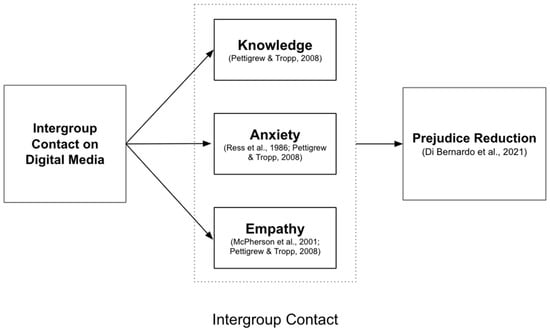

As the three mediators of intergroup contact suggest, reduction of prejudice is essential for creating a more inclusive, harmonious, and respectful society (Figure 1). Such a society enables individuals from diverse backgrounds to interact, collaborate, and thrive without the barriers of negative stereotypes and discrimination [7,8].

Figure 1.

Mediators of intergroup contact for prejudice reduction [8,12,48,55].

2.2. Intergroup Contact on Digital Media

Despite the potential for digital media content to facilitate positive intergroup contact through narratives, social media platforms have inadvertently fostered prejudice and discrimination, particularly among individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds [5]. This issue largely stems from platform designs that promote engagement with polarized perspectives and foster prejudicial attitudes toward outgroups, contributing to the spread of hate speech and dehumanized language [4,6]. These negative aspects of social media can undermine the effectiveness of the key mediators of intergroup contact, such as knowledge, anxiety, and empathy, by reinforcing stereotypes and promoting divisive content. Although this issue is recognized [15,25,39], previous studies do not fully capture the complex nature of today’s digital media landscape and its impact on how stories are perceived.

In fact, with increasing algorithmic curation and user involvement, a narrative in today’s digital media is shaped not only by its content but also by the medium—how and by whom it is conveyed—and that it attracts different types of people to watch the video, resulting in different sentiment outcomes and also exacerbating hatred in replies. For instance, Joi Ito emphasizes that in the internet world, context acts as the medium [56], suggesting that the live connectivity of the internet makes information reliant on the context that carries it as an influencing factor [57]. These outcomes, depending on what is in the comments, can also affect viewers’ anxiety or empathy toward cultural outgroups.

For instance, throughout the practices of creating content on the research site of this article, “Ethnic Neighborhoods”, we observed that the networked nature of narratives may alter or even amplify prejudice toward outgroups due to how messages are carried and perceived in digital spaces. Thus, while intergroup contact theory provides a framework for designing narrative content, it became necessary to understand how social media platforms carry our narrative, impacting the perception of messages about cultural outgroups.

2.3. Networked Narrative

Reflecting on how digital media platforms impact intergroup contact and perceptions toward outgroups, we incorporated the concept of “networked narrative” into our framework. This concept has been previously explored by researchers such as Kozinets et al. [20], who focused on the relationship between bloggers and readers and the communal norms that shape their interactions. Our research extends this concept to include the more interconnected nature of video-based social media platforms, examining how the platform, through recommendation engines, carries the message and affects how the narrative is perceived, particularly in the context of intergroup relations and prejudice reduction [58].

We hypothesize that, in addition to storytelling and interactivity [20] in networked narratives, algorithmic influence [59,60], a key feature of social media platforms, may play an important role in shaping the perception of stories related to cultural outgroups. We use the term “algorithmic influence” because home feeds on social media are now fully recommendation-based, and search results also show algorithmically curated feeds. Depending on individual behavior on the platform, such as the video chosen, the region of the viewer, and interests identified by the algorithm, the information you receive varies—the algorithm plays a key role in carrying the content [21], which can also lead to outcomes such as echo chambers [55].

The recommendation algorithms also curate and deliver content to users based on their preferences and viewing history, potentially exposing them exclusively to specific types of content and influencing their perception of the narrative [58]. The varying sentiment outcomes and the exacerbation of hatred in replies we observed throughout this project suggest that algorithmic influence may be attracting different types of viewers to a video, ultimately affecting the impact of intergroup contact on these platforms. This algorithmic aspect of networked narratives extends beyond the current framework [35] and warrants further investigation in the context of intergroup contact.

In summary, the exploration of intergroup contact theories has guided our understanding of how such contact occurs in digital media content, and networked narrative theory helps us to further understand how a digital media platform contributes to, or amplifies, perceptions toward cultural outgroups. Therefore, we have initiated the present action research within an ongoing YouTube project to investigate the role of networked narratives in intergroup contact on social media. Action research is particularly relevant for this study, as it allows for reflection on real-world phenomena and network narratives in actual contexts, which is critical for research on prejudice reduction [25,28,29]. By engaging in this action research project, our goal is to contribute to identifying actual elements in video content on digital media platforms that effectively reduce intergroup prejudice and promote empathy and understanding.

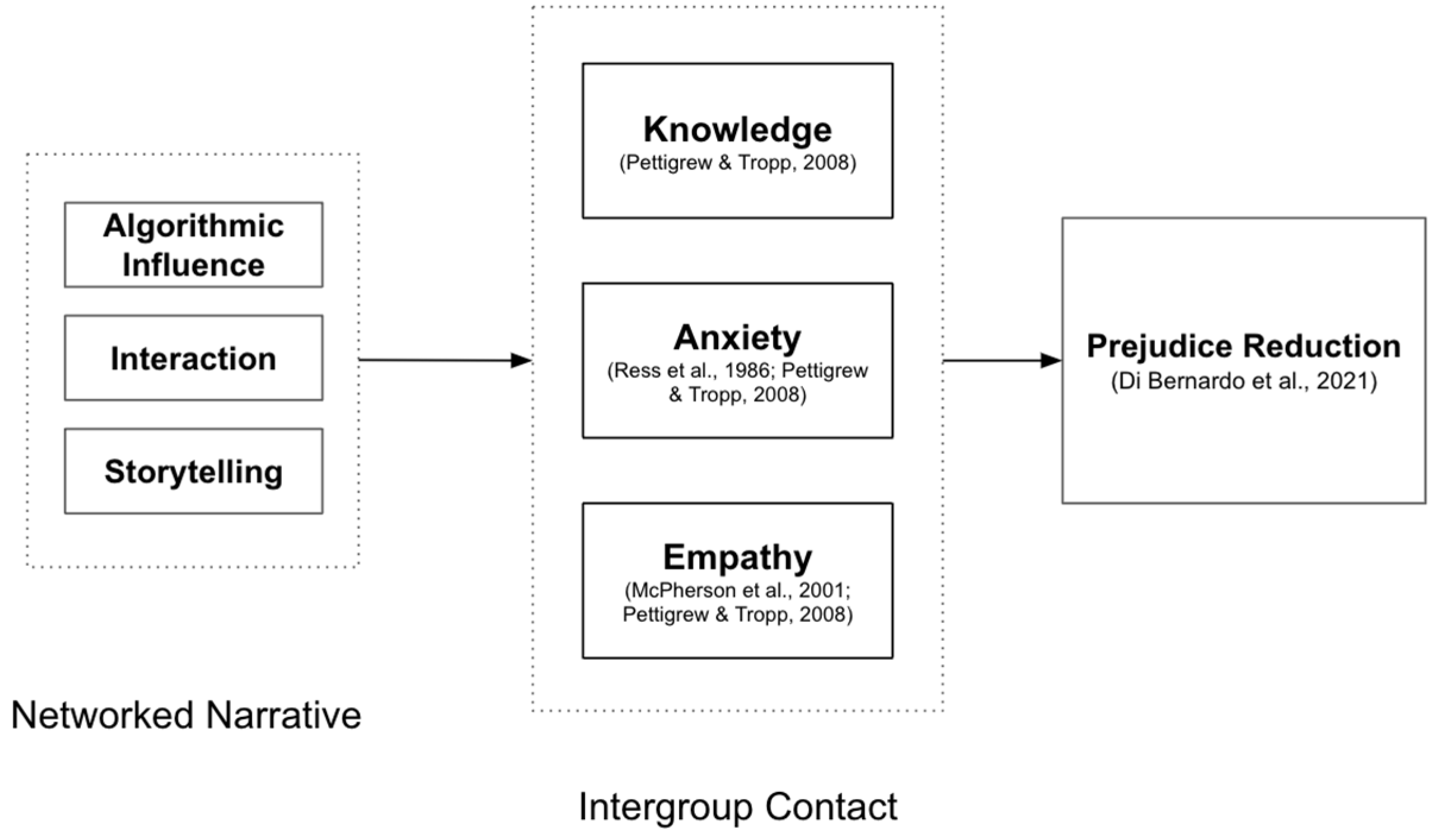

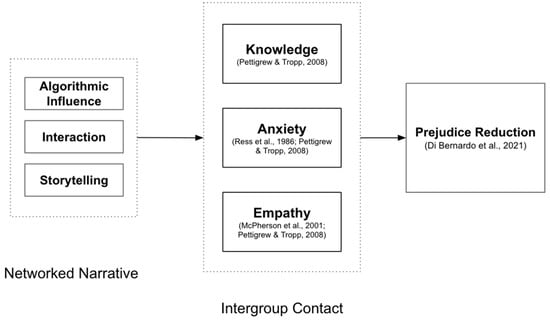

Therefore, we expanded Figure 1, “Intergroup Contact on Digital Media”, to include the elements of networked narratives in our research model (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mediators of intergroup contact on networked narratives for prejudice reduction [8,12,29,48,55,59,60].

3. Materials and Methods

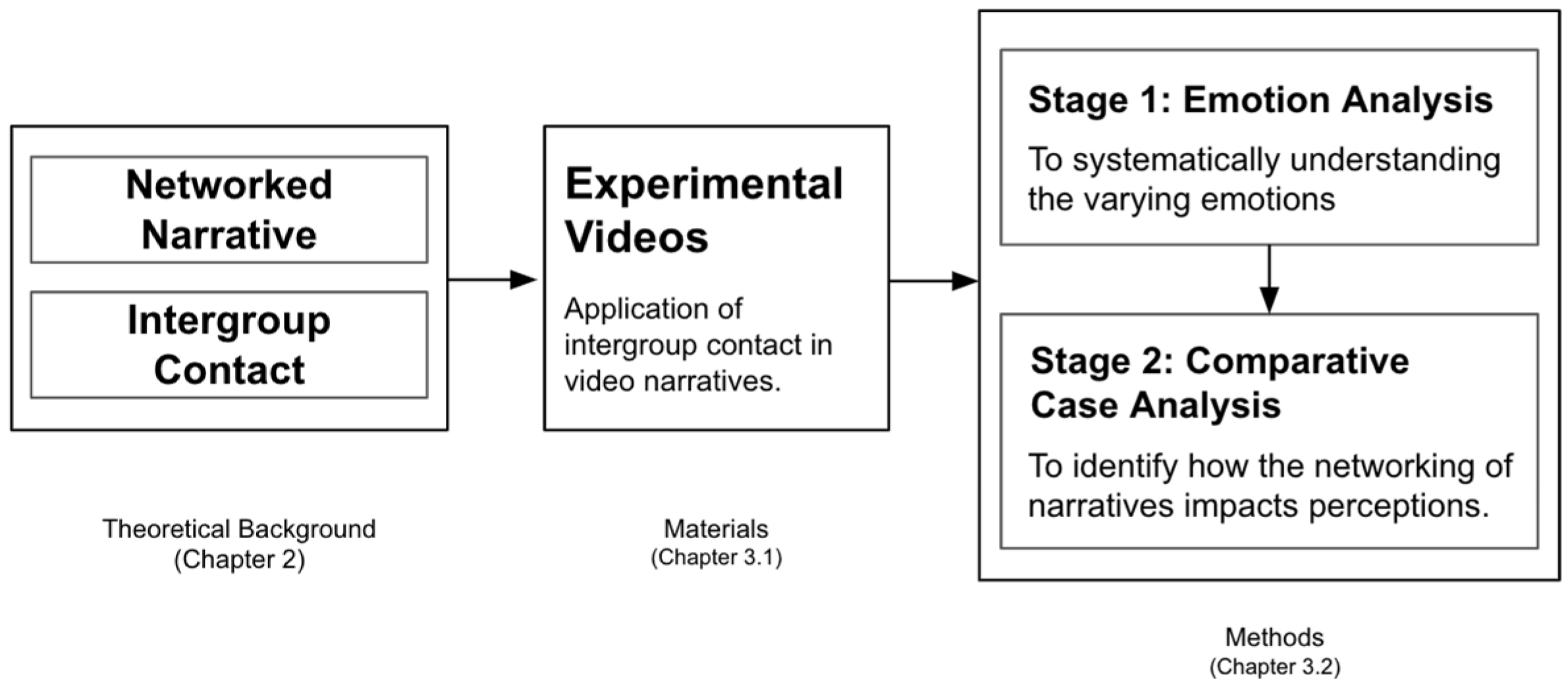

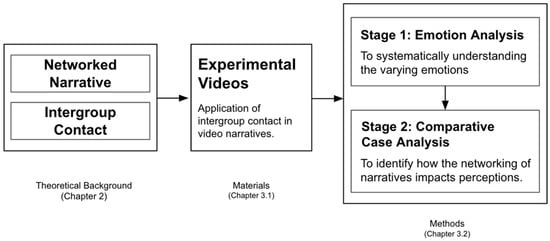

In this section, we describe the research site and the methodologies used to explore the objectives of this paper (Figure 3). First, we describe the designed experimental videos on a YouTube channel based on intergroup contact theory, and then we describe how the study employed a two-stage research approach, first analyzing emotions in the user comments and then conducting comparative case studies to explore how networked narrative elements affect user perception and engagement with the content.

Figure 3.

Flow of materials and methods.

3.1. Application of Intergroup Contact Model in Experimental Videos

To apply narratives reflecting intergroup contact theory, we have been producing videos on a YouTube channel titled “Ethnic Neighborhoods” (EN) since 2017 (Figure 4). This YouTube channel, with approximately 34,000 subscribers worldwide as of April 2024, showcases ethnic enclaves around the globe through casual, documentary-style content. It depicts the creators’ experiences with various cultural traditions, interactions with immigrants, and explorations of ethnic foods [17,61].

Figure 4.

Screenshot of the YouTube channel profile.

We adopted Pettigrew and Tropp’s [8] intergroup contact model, a widely adopted framework that identifies the most studied mediators of prejudice reduction through meta-analysis. Specifically, we designed our video narratives for our experiment based on this theory to reduce prejudice. These key mediators serve as essential links between intergroup contact and prejudice reduction. Through storytelling and direct interactions with users, the aim is to impact three mediating factors: (1) enhancing audience knowledge about the cultural outgroup, (2) reducing anxiety about the group by featuring trustworthy narrators sharing their experiences, and (3) fostering empathetic feelings.

The video narratives consistently feature the same storytellers, incorporating elements of their interactions with outgroups. This includes genuine reactions to exposure to outgroup culture and presentations of real-life videos showcasing daily life, neighborhoods, food, and stories through interviews. We have also opened up the comments section and moderated it as minimally as possible to foster an open, transparent, and welcoming interactive environment among viewers, reflecting the importance of interactivity in intergroup contact theory. Additionally, we have actively engaged with user comments to the greatest extent possible. However, when misinformation or hate speech arises, comments are either hidden or addressed with factual information to correct any misunderstandings.

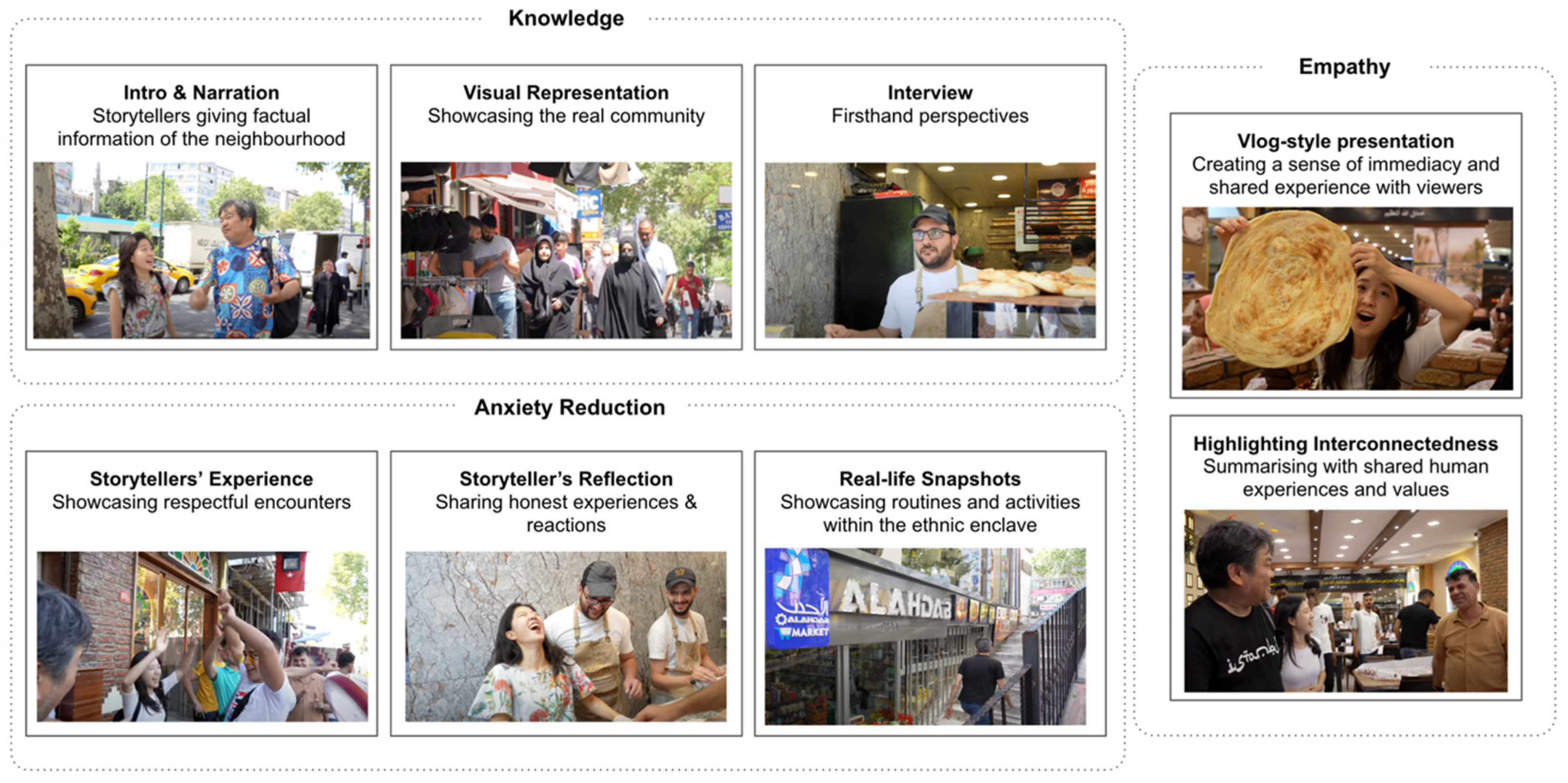

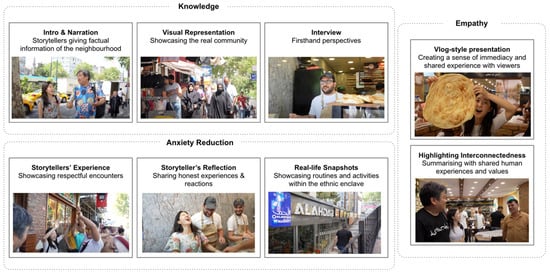

The Three Key Mediators in Video Narrative

To effectively implement the intergroup contact model in our videos, we focused on incorporating elements that address each of the three key mediators: knowledge gain, anxiety reduction, and empathy building.

For knowledge gain, we included narration and factual information about the ethnic community and the region [62] along with interviews with local residents to provide a fair and authentic perspective. One storyteller begins each video by explaining the location of the neighborhood, the purpose of the visit, and what to expect, followed by an insert shot of the location featuring the lives of the people in the neighborhood to show real-life images. The interviews were conducted ad hoc, with no questions given in advance, and were all filmed on the spot to ensure originality and honesty. This approach aims to provide viewers with genuine, unfiltered insights into the lives and experiences of people from cultural outgroups, thereby increasing knowledge and understanding.

To reduce anxiety toward ethnic communities, we placed a primary focus on having the storytellers, who come from different cultural backgrounds and share honest experiences and reflections to break down fear toward the cultural outgroup [63]. For instance, if any part of the cultural experience, such as an exotic food or a restaurant with a foreign ambiance, was new or unfamiliar to the storyteller, we honestly captured their reaction. In the process of selecting neighborhoods to feature, we conducted location scouting and prior research with local residents to ensure the safety of the location and the individuals featured in the video. We also showcased the everyday lives of the people to demonstrate that these neighborhoods, at their core, are places where people live, eat, love, and socialize with friends, just like in any other community. This approach humanizes the cultural outgroup and highlights the commonalities shared by all people, regardless of their cultural background.

Finally, while the elements in anxiety reduction also contribute to empathy building, we incorporated two additional elements in our video design to further foster empathy. First, we adopted a vlog-style format to create a sense of intimacy, immediacy, and a more immersive experience for the audience, promoting a closer connection. Second, at the end of each video, we provided a summary of the experience, highlighting the interconnectedness the storytellers felt throughout the process. It is important to acknowledge that empathy is a complex emotion that is interconnected with various emotional experiences, such as anxiety reduction and knowledge acquisition [64,65].

Figure 5 shows the narrative elements designed to reflect Table 1 through these screenshots. Despite introducing different ethnic neighborhoods, all the videos feature consistent elements.

Figure 5.

Screenshots of the narrative elements in the experimental videos.

Table 1.

Intergroup contact mediators and designed narrative element.

3.2. Two-Stage Research Approach

For the analysis, we first selected three videos featuring Somali, Congolese, and Uyghur communities in Guangzhou, China, that are particularly similar in their narrative to better understand the factors contributing to the varied user emotions observed in our YouTube content (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Screenshots from the three videos used in methods.

These videos were published between 2019 and 2020. Filmed in 2017 at the same location, Guangzhou, the videos maintained a consistent style, background music, hosts, and narrative across the different ethnic neighborhoods (See Figure 6). The Somali video showcased the Somali community in Guangzhou, introduced by an immigrant engaged in business in China. The hosts visited a Somali restaurant and experienced a Somali-style haircut at a local barber shop. The Congolese video highlighted a Congolese restaurant and interactions with Congolese immigrants in the region while also introducing the broader African community in China through street interviews. The Uyghur video provided an introduction to the Muslim community in Guangzhou, featuring one of the hosts making Uyghur naan alongside locals despite the language barrier and the two hosts sampling Uyghur cuisine together.

3.2.1. Stage 1: Emotion Analysis

Preliminary observations from our practice revealed varying user emotions across our YouTube content. To move beyond anecdotal evidence and develop a methodological analysis of these emotional variations, we first employed GPT-3.5 for autonomous text analysis using prompts to assess the emotions conveyed in comments across the three videos (n = 2354). We categorized the emotions based on the six basic emotions identified by Ekman and Friesen [66]: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust. These universally recognized emotions [67,68] provided a foundation for understanding the universality of emotional experiences. Following Rathje et al. [69], we refrained from providing specific definitions for these emotions, as prompts without detailed definitions can still yield accurate results when using GPT for emotion analysis.

We scraped all comments (n = 2354) from the three YouTube videos, including the timecode of each comment, the number of replies, and whether the comment was independent or a reply to another comment. We then programmed Python to run with GPT to analyze the comments, identify the expressed emotion, and explain the rationale for each categorization. The prompt used was as follows:

“Identify which basic emotion—anger, fear, enjoyment, sadness, disgust, or surprise—is most prominently reflected in the following text. Explain your choice by discussing the specific words, phrases, and overall emotional tone that led to your decision.”

The stage 1 methodology enables the identification of patterns in emotional responses, providing insights into the varying sentiments expressed by users. However, it offers limited understanding of how the platform’s networked nature influences these reactions [20]. To address this gap and gain further understanding of how the message was transmitted and interpreted through networked narratives, we conducted a qualitative comparative case study in stage 2.

3.2.2. Stage 2: Comparative Case Studies

In this stage, we examined how the combination of storytelling, user interactivity, and algorithmic influence affects the discovery, interaction, and consumption of narratives presented in our videos [20,58,59,60]. Building on the reactions identified in stage 1, we find it necessary to explore how this networked narrative impacts the audience’s appreciation of the message. Our qualitative approach facilitated an analysis of the factors inherent in networked narratives that shape user perceptions and interactions.

Given that the storytelling design has been previously addressed in Section 3.1, this stage focused on two additional aspects: user interactivity and algorithmic influence. The comparative case study methodology employed in this stage comprised the following components:

- User interactivity: we analyzed user comments to understand how viewers engaged with the content and each other.

- Algorithmic influence: to identify the algorithmic influence of YouTube, data spanning the videos’ lifetime (from the initial publishing date to May 2024) were analyzed. The following metrics were examined:

- Traffic sources: we analyzed how viewers discovered the content, whether through browse features like suggested videos or direct searches, and we examined viewing hours to understand engagement patterns.

- Geographic distribution: we looked at the geographic location of viewers to understand the reach within diasporic communities and local populations.

- Search trends: we examined the keywords viewers used to find content related to each cultural group, revealing insights into audience interests and information-seeking behavior.

In summary, our two-stage research approach combined automated emotion analysis and qualitative examination of networked narratives for the three case videos. The following section presents the results of the methods.

4. Results

4.1. Stage 1: Emotion Analysis

We first examined the top 15 comments based on the number of likes. Top comments here are identified as comments with most likes.

Table 2 shows that while the Uyghur (73.3%) and Somali (81.3%) videos exhibited a similar pattern for happiness as the dominating emotion, the Congolese episode had a higher proportion of comments recorded for anger (47.1%). The comment with most likes indicates anger as follows:

Table 2.

Frequency of emotion in the top 15 comments.

That not fair, that the Chinese won’t let the Africans own there own restaurant in China but the Chinese can come to Africa and own all kinds of Businesses. China is very prejudice in that way!!!

GPT analysis described the reason for categorizing this comment as anger:

“The text expresses frustration and anger towards the unfair treatment of Africans in China compared to the privileges given to Chinese in Africa. The use of words like ‘not fair’, ‘prejudice’, and multiple exclamation marks highlights the strong negative sentiment. The emotion of anger is evident from the tone and the feelings of injustice expressed in the text.”

We understood from the comment that people were expressing frustrations or concerns toward the geopolitical challenges Africans face in the region. In fact, the most liked comments were those that reflected concern about issues in that region. While it was unclear whether they belonged to the ingroup or outgroup, it was evident that regardless of the video’s content, they would leave a comment to portray their frustration with the issue itself rather than express a reaction to the video.

The Somali and Uyghur videos produced a much higher level of happiness, but we also found a difference in the context surrounding happiness. For instance, the top comments indicating happiness in the Somali video suggest that these were possibly from ingroup people watching the content:

I’m watching in garowe the capital city of puntland state of somalia One love both japanese and somali JPSO❤

Hehehe Somali people are pretty much everywhere. The entrepreneurship is imbedded in our DNA. Besides Somalis holding on tight to their religion this is my second main reason why i’m proud of my people.

Here, from the Somali video, we noticed that while happiness was the predominant category, Somalis from around the world gathered in the comments, forming a bond and expressing pride in their community. The community also expressed strong support for their outgroup, especially toward Chinese and Japanese individuals, as the two storytellers were identified as Japanese, and the region was in China:

I am from muqdishu somalia SO. Been living and studying Zhejiang province CN for the last 3 years:) China is such a great place and a very good experience. This video made me miss our ethnic food.

In contrast, the comments recorded for happiness in the Uyghur video were more focused on the content creator and on support for the Uyghur community by an outgroup. For instance, the top comments included the following:

I loved this video. It’s really heartwarming and you’re a great person.

Ah, I think I am going to go eat laghman + somsa today. You guys really increased my appetite.

Greetings to all muslim brothers and sisters in Guangzhou. Uyghur—Turkish style of bread. We bake and eat similar style bread in Turkey.

The difference in the level of happiness between the Somali and Uyghur videos could also be attributed to the language spoken in the videos. While the Uyghur video primarily featured English with some spoken Chinese and English subtitles, the other videos were mainly in English. As English is not a primary language for the Uyghurs, the storyteller communicated with them in Chinese in the video. This suggests that our Uyghur video might not have been exposed to the Uyghur community as much as the Somali video was exposed to Somali communities.

To identify the overall pattern, we have further conducted the same autonomous text analysis on all comments (n = 2354) from the three videos, including replies to comments. The Uyghur video recorded n = 102 comments; the Congolese video, n = 1501 comments; and the Somali video, n = 1647 comments.

Results of Emotion Analysis of Comments and Replies

Unlike the results of the top comments analysis, happiness was the most commonly expressed emotion in the overall comments of all three videos (Table 3). The Somali video had the highest overall percentage recorded for happiness in both comments (71.7%) and replies (39.3%), suggesting a more positive discussion tone, likely reflecting ingroup support and pride [4]. The Congolese video, despite recording comparatively fewer expressions of happiness, still produced a higher percentage overall than it did in its top comments. We found that there were comments with few or no likes that recorded happiness, either supporting Africa or praising the two storytellers for covering the story. This interesting finding suggests that while the top comments were mostly expressing anger, there were more supporting comments underneath.

Table 3.

Results of emotion analysis, expressed in percentages.

However, the Congolese video overall still elicited more varied emotions, leading to higher levels of anger and disgust in the replies. In contrast, the Uyghur video produced less happiness, especially in replies (39.3%), possibly indicating more appreciation of the content by outgroup individuals than ingroup support. The anger expressed in comments on the Congolese video, such as the quote above, was directed toward the region. In contrast, anger in the Somali video comments stemmed from religious arguments among Muslims and Somalis, as seen in comments like the following:

Guys you can’t understand the different and every foreign youtuber comment section i see somalis bullying each other only based about their qabil or gobol…

Notably, instances of anger were consistently more numerous, and those of happiness were fewer in replies compared to comments across all videos, with the largest differences observed in the Uyghur (−10.8%) and Congolese (−15.5%) videos. This suggests that replies were more emotionally charged and negative, reflecting a “negativity spiral” [4] and aligning with Taecharungroj’s [70] finding that negative emotions like anger are more prevalent in replies than in original comments. We can infer how the YouTube platform shapes the emotional dynamics of intergroup discussions in the comments section, potentially causing psychological shifts after reading others’ reactions [71]. The reply feature facilitates the development of sub-conversations and emotional exchanges distinct from the initial comments [70], which can amplify positive or negative sentiments toward the featured ethnic groups.

In summary, our emotional analysis findings indicate the following:

- (1)

- Hatred or anger is exacerbated in replies over time, especially after people read a comment that fosters their anger, whether directed at ingroups or outgroups. This could potentially affect the anxiety of the audience in intergroup contact watching the content, as they are exposed to extreme conversations or fights among users [44], which also exacerbates the gap in empathy [50].

- (2)

- Our audience varies significantly across the three videos, attracting different people despite being on the same channel, possibly due to YouTube’s search engine-like features [70].

- (3)

- Although the emotions expressed in comments provide insight into the audience’s feelings, there are more complex dynamics at play that are difficult to identify through individual comments and emotions alone [20].

4.2. Stage 2: Comparative Case Studies

The stage 2 research results present each video individually, providing details of the findings of the networked narratives surrounding the three cases. In Table 4, we first present a table comparing the suggested videos, which are recommended on the watch page for viewers to watch next, in order of most traffic. This indicates the traffic source and view duration of the viewers from that source. Then, we report the findings for each video featuring the Uyghur, Congolese, and Somali communities in Guangzhou.

Table 4.

Details of suggested videos and average view duration.

4.2.1. Uyghurs in Guangzhou

The Uyghur video had the lowest number of views (14,752) among the three videos, with the United States (644 views), Japan (163 views), and India (153 views) as the top viewing countries. The video’s traffic was primarily driven by YouTube search (4451 views), suggesting active interest in the Uyghur community. However, unlike the other videos, this video was not significantly promoted by the algorithm, resulting in a lower number of views.

The top search keywords, such as “uyghur” (207 views), “guangzhou” (188 views), and “uyghurs in china” (92 views), indicate an interest in the Uyghur community’s experiences in China. Interestingly, people who accessed the video through a search had the shortest average view duration (02:51). In contrast, people who accessed the video through suggested videos recorded a longer watch duration. Notably, the second highest view duration among the suggested videos was for those with content featuring different ethnic communities created by the storyteller on “Ethnic Neighborhoods”. This finding suggests that viewers who explore other videos on the channel may develop a more positive interest that leads to loyalty or trust in the content creator. This engagement potentially reduces anxiety toward other ethnic communities and facilitates the acquisition of new knowledge through exploration of diverse content.

As the emotion analysis in stage 1 revealed, the user interactivity with this video showed positive support for the cultural outgroup and expressed appreciation for the channel creator. A top comment showed that the viewer has viewed our other experimental videos in Guangzhou:

So glad to see you back in Guangzhou! Multiculturalism has always been flowing in the veins of the Guangzhou local people! Islam, in its imported and localised forms, has always been one of our cherished blossoms in this millennia-old yet lively garden that is Guangzhou!

However, upon examination of the replies in the comments, particularly in the context of the substantial disparity in emotional responses within the Uyghur video replies (Table 3, 36.1% difference in happiness), we found that a comment with a positive message with the most likes had negative replies that highlighted issues faced by the outgroup in the Guangzhou region, though not specifically directed at the cultural outgroup as, for instance, in the comment below:

Top Comment: This is probably one of my favourite episodes by far! Loved the diverse community in Guangzhou so much <3

Replies: I hope you reply to those speculations in the comments section that Uyghurs are followed by government agents to not say a thing about their situation. Tell them if you see sadness in those faces. Tell them if you see agents around them. (…)

This result indicates that the positive emotional reactions are likely derived from audiences previously exposed to the creator’s other content. However, the interaction pattern in replies suggests that it also served as a catalyst for discussing more complex regional issues.

4.2.2. Congolese in Guangzhou

The Congolese video had the second-highest number of views (244,289), with the United States (58,853 views), United Kingdom (15,060 views), and Canada (11,131 views) as the top viewing countries. These viewership patterns could indicate that people from the African continent, rather than specifically Congolese individuals, were accessing the video. The video’s traffic was primarily driven by suggested videos (119,317 views) and browse features (84,703 views), highlighting the influence of YouTube’s recommendation system on content discovery.

The top search keyword “guangzhou” (4039 views) sheds light on why the comments often focused on the geopolitical issues of the region. Moreover, the suggested videos indicate that negative portrayals of the African community and the Guangzhou region were being recommended after the Congolese video. Despite this, the Congolese video had the longest average view duration (4:35 min), suggesting higher engagement and potential for knowledge acquisition among viewers. We perceive the viewers to be a mixture of ingroup (Africans) and outgroup (non-Africans interested in the region or African culture) individuals watching the content, likely to acquire more knowledge on the subject.

Nevertheless, the data on recommended videos indicate that the Congolese video is the most viewed among all ethnic neighborhood videos on the channel through suggested video recommendations (“Little Africa in Guangzhou|Congolese Food in China 1”). This suggests that the video may be functioning as a form of extended contact, potentially encouraging viewers to engage with content featuring other outgroups created by the same channel, despite the initial negative context.

Furthermore, we found that negative user interactions in this Congolese video (47.1% anger in top 15 comments) were due to a strong division between locals and outgroups (both Chinese and non-Chinese), with varying perceptions even among the outgroups. The most frequently endorsed comments displayed at the top of the comment section exhibit a range of sentiments. For instance, some comments express political critiques:

African can not own a business in China but Chinese have a whole lot of businesses in Africa. What is wrong with Africa policy makers? Wake up Africa!!

That not fair, that the Chinese won’t let the Africans own there own restaurant in China but the Chinese can come to Africa and own all kinds of Businesses. China is very prejudice in that way!!!

Conversely, while it was the lowest proportion of the positive top comments among the three videos, these comments were as follows:

These two are so kind and respectful! Love the way they were fearless to try new stuff

“How beautiful life is if we loved one another and coexisted worldwide.” Life would be so much fun

In summary, despite achieving the longest average view duration among the three cases, the Congolese video sparked divisive discussions. Comments often focused on geopolitical issues between Africa and China, reflecting a polarization that was mirrored in the recommended videos, which frequently portrayed the African community in Guangzhou negatively. However, amid the controversy, a few highly engaged comments expressed positive sentiments about cultural exchange and coexistence.

4.2.3. Somalis in Guangzhou

The Somali video had the highest number of views (285,570) among the three videos, with the United States (40,128 views), Kenya (24,289 views), and Canada (13,904 views) as the top viewing countries. The high viewership from Kenya, a country with a significant Somali population, suggests that the video resonated with the Somali diaspora. The top search keywords, such as “somali” (2538 views), “somali food” (419 views), and “somali community in guangzhou” (144 views), indicate a strong interest in Somali culture and experiences, primarily from the ingroup.

The video’s traffic was largely driven by browse features (193,222 views), suggesting that viewers discovered the content through YouTube’s recommendations. This is common for videos with a high number of views, as the video is featured on the home feed of users who are not subscribed to the content. An analysis of the recommended videos reveals that the viewership comes from people who have watched content related to Somali culture, indicating that viewers have a high interest in or desire for knowledge gain about Somali culture. The prevalence of search terms and recommended videos related to Somali culture and experiences suggests that the video effectively promoted knowledge and understanding of the Somali community.

One important finding is that the Somali video had the shortest average view duration (3:11 min) among the three videos, despite having the highest number of comments (n = 1647). Considering that the comments on the Somali video were primarily from Somalis supporting their ingroup across the world, we can infer that viewers spent a short amount of time watching the video and may be commenting without fully engaging with the narrative. Our analysis revealed that viewers of the Somali video tend not to watch other videos featuring different ethnic groups on the channel. Instead, they predominantly seek out more positive videos about Somali people. This trend is reflected in the top recommended videos, where the most viewed content consisted of other Somali-focused videos created by the same storyteller on the channel. The only exception among the top suggested videos was the Congolese video, which, despite being recommended, had the shortest average view duration. While an outgroup person could gain a positive influence from such curation, the comments and demographics suggest that this Somali video is primarily being recommended to ingroup individuals.

The high positive emotion (81.3% happiness) in user interactivity was largely driven by Somalis’ excitement about being highlighted in the video content. At the same time, we also found high levels of support, advocacy, and appreciation from Somali viewers toward other cultural outgroups. For instance, in the Congolese video, we found messages from Somalis such as the following:

From somalia 2019 I was congo Is good country CDSO I am very like food of congales like that (fuufu)

Love and support from Somalia SO

Furthermore, in a video on “Ethnic Neighborhoods” featuring Pakistanis in Japan, we received various comments from Somalis, including the following:

Masha Allah Pakistanis brothers Allah/God bless you.❤ PK Pakistan and JP Japan. From Somalia SO. But now I’m in Turkey Istanbul for studying.❤ also TR Turkish brothers.

As the search trends and the location of the viewers indicate, unlike the Uyghurs and Congolese videos, individuals who watch Somali videos are largely ingroups, who enjoy positive portrayals of their culture. Yet, despite the high view counts and comment numbers, the Somali video had the shortest average view duration (for more details, see Supplementary Materials). Furthermore, while Somalis’ high level of positivity may imply limited intercultural interactions in the interactivity of the specific video, their extended behavior of positivity on other channels can also be a positive indicator of how recognition of an ethnic group by a cultural outgroup could lead to effects similar to shared intergroup contact [7].

5. Discussion

Similarity breeds connection [19], so our research was driven by the belief that diversity breeds intercultural understanding and empathy. Unfortunately, the more connected we are technologically, the more disconnected and polarized we become emotionally. Nevertheless, social media networks were initially designed to create spaces for individuals to form healthy bonds across diverse cultural and geographical contexts—an ethos we must strive to revive. This action research, based on a real-life case, addresses the research gap in intergroup contact within today’s networked narratives by utilizing actual data from a YouTube channel, a resource seldom explored in academic research. By identifying what amplifies and what reduces prejudice toward cultural outgroups through actual implementation, we hoped to bring insights on how we can design spaces where humanity connects heartfully, bringing individuals together rather than amplifying hatred. Through specific elements in today’s digital media platforms that influence human perception of cultural outgroups, this research provided a deeper understanding of how networked narratives advance intergroup contact and how platforms can be utilized to better bridge individuals across cultures. In this process, we advance the “networked narrative” to fit today’s social media context, which extends traditional narrative research by incorporating the influence of algorithmic curation, user interactions, and platform design in today’s connected environment. The case studies and experiments presented in this paper provide actual findings and applications of how networked narratives work and how they should be managed.

The findings from our analysis of the Uyghur, Congolese, and Somali videos on the “Ethnic Neighborhoods” YouTube channel provide insights into the dynamics between networked narratives, intergroup contact theory, and prejudice reduction in the digital age. By examining the YouTube analytics data and emotion analysis of comments, we can better understand how network narratives shape viewers’ knowledge, anxiety, and empathy toward cultural outgroups, as outlined in Pettigrew and Tropp’s [8] intergroup contact model.

5.1. Knowledge Acquisition

While knowledge was found to make a weaker contribution to prejudice reduction [8], an accurate understanding of information from various perspectives, especially concerning ethnic communities, is important in raising awareness and reducing fear. Our videos serve as a platform for viewers to acquire new knowledge about different ethnic communities, their cultures, and their experiences. The presence of search keywords related to the ethnic groups, such as “uyghur” (207 views), “congolese” (119 views), and “somali” (2538 views), or the region “guangzhou”, suggests an interest among some viewers in learning more about these entities. The inclusion of factual information, interviews with community members, and immersive visual representations of the neighborhoods in our videos aims to contribute to viewers’ understanding and awareness of these cultural outgroups [3,25,42].

However, the network narrative not only attracts different types of viewership to the video but also results in varying emotions, especially in replies, often leading to the growth of negative sentiments and arguments, especially when dealing with sensitive topics [4]. This highlights the importance of considering the potential impact of networked narratives on knowledge acquisition and the need for the careful curation of content and engagement to promote a more nuanced understanding of cultural outgroups.

In the examination of user interactivity, we have also found that viewers co-construct knowledge through interactions. For instance, when the portrayed food appears inauthentic, or when there are misinterpretations or typographical errors in the video narrative, viewers actively correct these issues, with other users endorsing such revisions. Additionally, some viewers contribute by sharing additional knowledge about the region or community. This reflects the originating definition of “networked narrative”, where the narrative is co-created by participants in the online community [20]

Nevertheless, we have found that the role of storytelling is still highly important in conveying the right knowledge. While this knowledge can be curated in ways in which the algorithm drives people to negative content (like the Congolese video) or deeper into a specific content (like the Somali video), it is through the real-life raw footage of the experience that the video content contributes new knowledge in an accessible way, such as through the daily lives of Uyghur, Congolese, and Somali communities, potentially fostering a deeper understanding of their cultures.

5.2. Anxiety Reduction

Our experimental videos incorporate several elements designed to reduce viewers’ anxiety toward unfamiliar cultures and promote positive intergroup attitudes. The storytellers’ experiences, such as sharing a dance with locals, having a haircut at the local barber, and expressing genuine appreciation for the communities they visit, can help create a sense of familiarity and comfort for viewers [47,63,64,69]. By showcasing respectful interactions and the universality of the human experience, our videos have the potential to reduce viewers’ apprehension toward interacting with cultural outgroups. Furthermore, engaging with food-related content can help reduce anxiety by highlighting the shared enjoyment and appreciation of diverse culinary traditions. Watching storytellers try new dishes and express enthusiasm for the flavors and customs of different ethnic communities can create a sense of connection and commonality, potentially reducing viewers’ anxiety toward unfamiliar cultures.

Nevertheless, our analysis reveals that networked narratives can inadvertently amplify anxiety. The search keywords directing users to negative portrayals of cultural outgroups, leading to divisive debates and discussions in the comments section and escalating negative emotions in replies, indicate that algorithmic influence and user interactivity can exacerbate existing tensions and increase discomfort and fear among viewers [4,63]. As observed in the Congolese video, negative algorithmic curation led to adverse emotional reactions from viewers, contrary to our intentions. This algorithmic curation of the video display impacts viewers’ fear toward the region or the outgroup, subsequently affecting user interactions in the comments section negatively.

At the same time, we observed that while the proportion of negative and positive emotions in the top 15 comments of the three videos varied, they appeared interspersed among each other. This could be attributed to YouTube’s algorithmic design intended to display diverse emotions and perspectives in the comments. Furthermore, suggested viewership and average view duration of the Uyghur and Congolese videos show that continuous exposure to content designed to reduce anxiety can in fact foster positive new connections and interest in other ethnic neighborhoods featured on the same channel.

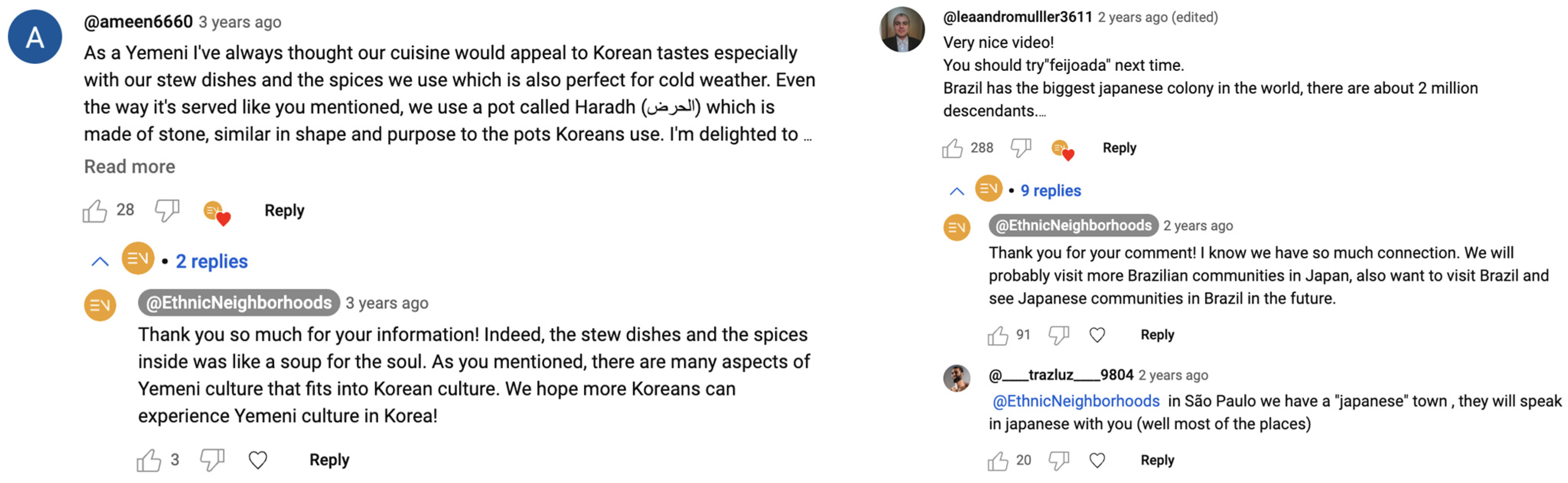

5.3. Empathy Development

Our videos aim to foster empathy and emotional connection between viewers and cultural outgroups through various narrative elements. The vlog-style presentation and the storytellers’ sharing of personal learning experiences and vulnerability help create a sense of immediacy and shared experience with viewers [28,72,73]. By highlighting the interconnectedness of human experiences and values, our videos encourage viewers to understand and relate to the perspectives of individuals from different ethnic communities. We have found, especially, that appreciation of another culture results when viewers witness respect for that culture, such as how the Somalis appreciated the Japanese and the Chinese for highlighting their culture. Other example also include the following:

Omg it was so cool to see the lady speak the Congolese native language. I love seeing all the different languages and cultures.

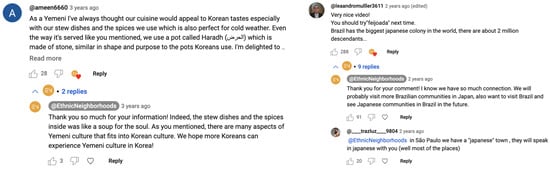

However, the networkedness of the narrative can also lead to varying emotions and the growth of negative sentiment, particularly when dealing with sensitive topics. This highlights the importance of the storyteller’s intervention, such as replying to comments or leaving a comment (see Figure 7), in promoting a more constructive dialogue and fostering empathy [74]. As seen in the Somali and Uyghur videos, where the storyteller actively participated in the comments section, the sentiment was generally more positive, whereas in the Congolese video, where the storyteller did not intervene, the top comments were predominantly angry and furious.

Figure 7.

Screenshots of the comments and replies. The Haradh (الحرض) pot is a traditional cooking pot that originates from Yemen.

Thus, to reduce prejudice in networked narratives, storytellers should participate in the user interactions to curate and positively impact intergroup contact.

5.4. The Role of Storyteller in Networked Narratives

YouTube’s diverse user base attracts viewers with varying intentions to our videos. Our analysis of geographic distribution and search keywords revealed distinct viewer groups: ingroups watching ingroup content (e.g., Somalis); individuals interested in geopolitics, seeking information on Africans in China; supporters of the channel or the intergroup topic; and those drawn by culinary interests. While this research primarily focuses on perceptions of cultural outgroups through online intergroup contact, the convergent nature of our study precludes a precise identification of viewer demographics.

Nevertheless, our findings suggest that the role of the storyteller in navigating networked narratives, particularly in polarized discussions, emerged as a potentially significant factor.

For instance, despite the presence of negative sentiments in the Congolese video comments and misinterpretations of the storyteller’s intentions, we observed consistent viewership of the videos across the channel. The Uyghur video, which had the longest average view duration among viewers who had watched other channel content, also demonstrated the most positive outgroup user emotions in interactions. These viewer retention patterns suggest an increasing interest in the storyteller and narrative, potentially influencing viewers’ readiness to acquire new knowledge, reduce anxiety, and develop empathy toward cultural outgroups [8].

Furthermore, Somali viewers expressing support for other cultural outgroups indicated that the storyteller’s recognition of their own group through empathy motivated intercultural solidarity. Also, the highly endorsed comments from other videos on our project indicated the possibility of positive interest:

Funny how this video pops up after Africans/blacks have been mistreated in China and everywhere else in world, Africa has laid the foundation for humanity. I wish more people appreciated us like the reporter in the video! Oh and the food looks great!

Thank you for making these amazing videos! I have been watching since the Somali videos and I must say this is by far one of the best channels. Truly fascinating to watch.

We have also observed that in videos where the storyteller actively participated in the comments section, such as in the Somali and Uyghur videos, the sentiment was generally more positive. In contrast, the Congolese video, where the storyteller did not intervene, had predominantly angry and furious top comments. This observation suggests that storyteller intervention might be necessary in promoting more constructive dialogue and fostering empathy.

While our study did not directly measure factors such as trust in the storyteller, the patterns we observed extend beyond our initial model (Figure 2). Even amidst algorithmic curation that can amplify negativity and foster heated debates through networked narratives, positive engagement with the storyteller and content may influence viewer’s readiness for intergroup contact for prejudice reduction. Positive engagement with the storyteller can facilitate a virtuous cycle of positive intergroup contact, where viewers who have positive experiences engaging with the content and the community are more likely to seek out additional opportunities for learning and interaction, further reinforcing their positive attitudes and behaviors toward cultural outgroups.

When this positive experience extends into trust, it can also help to mitigate the potential negative effects of networked narratives [7], such as the spread of negative sentiments and misinformation, by contributing to a more resilient and supportive digital community. However, this influence could potentially be used maliciously if the storyteller’s intentions are not aligned with promoting positive intergroup relations.

5.5. Summary of Findings

Our research, which involved designing videos based on intergroup contact theory and conducting a two-stage study to understand the role of networked narratives in intergroup contact for prejudice reduction, yielded several findings:

- (1)

- Negative algorithmic influence leads to negative emotion. Despite storytelling designed with mediated intergroup contact theory, networked narratives impact overall user emotions toward the cultural outgroup. While this concept has been previously postulated, empirical evidence from action research in previous studies has been limited.

- (2)

- Audience engagement patterns vary, and the same channel attracts different audience types and engagement levels.

- (3)

- Emotion trends in user interactivity indicated that replies generally exhibited more negative emotions than initial comments across all videos.

- (4)

- Consistent viewership and positive interactions across different videos suggested the potential for building positive intergroup relations through the storyteller over time and that there is the possibility of positive engagements with the storyteller, fostering a supportive digital community and potentially mitigating some negative effects of networked narratives.

These findings indicate that the interconnected nature of networked narratives, combined with user interactivity and algorithmic influence, together with the role of the storyteller, can lead to complex outcomes in digital intergroup contact scenarios. Importantly, they reveal that the storyteller has very little control over these outcomes despite the dependency that some viewers may develop on the storyteller.

Building on these insights, our research makes several contributions to the theoretical foundations of online intergroup contact:

- (1)

- Our research extends intergroup contact theory by applying it to contemporary social media environments characterized by networked narratives. It contributes to the framework of networked narratives by encompassing the influences of algorithmic curation, user interactivity, and storytelling.

- (2)

- It expands the application of intergroup contact theory to an actual social media channel, thereby providing empirical evidence of its dynamics within networked narrative environments.

- (3)

- It offers empirical insights into how algorithmic influence, user interactivity, and storyteller engagement collectively shape intergroup attitudes within digital spaces, thus advancing our understanding of prejudice reduction mechanisms in online contexts.

In conclusion, our research highlights the need for careful consideration of these factors in designing and implementing strategies for prejudice reduction in online environments.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Our action research, based on real-life experiments with the Uyghur, Congolese, and Somali videos on the “Ethnic Neighborhoods” YouTube channel, provides valuable insights into the complex dynamics of prejudice reduction through networked narratives in the digital age. By integrating intergroup contact theory with network narrative theory, we aimed to contribute to an understanding of how social media impacts efforts to promote positive intergroup contact and reduce prejudice. Through real-life experiments involving video design and analysis of actual user engagement data and comments, we provide empirical evidence for potential benefits and challenges.

While our research offers valuable insights into the dynamics of networked narratives and prejudice reduction on YouTube, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. The study focuses on a specific set of videos featuring three ethnic communities in Guangzhou, China, and the findings may be relevant only to this context and those communities. Moreover, the analysis relies on a limited sample of comments and views, and the data provided by the platform do not give us a clear understanding of whether the viewers were ingroup or outgroup members. Pre-existing prejudices may influence viewers’ perceptions more than the networked narrative itself. Future research should explore a broader range of content, covering different communities and geographic locations, such as ethnic enclaves in other major cities or regions with significant cultural diversity. Additionally, since the findings may be specific to the context of Guangzhou, comparative studies in other regions would help determine the generalizability of the observations.

Future research could explore the dynamics of networked narratives and prejudice reduction across different social media platforms, geographic contexts, and ethnic communities. Additionally, more in-depth qualitative analysis of user comments and interactions could provide further insights into the complex processes of knowledge acquisition, anxiety reduction, and empathy development in digital spaces.

To better understand the impact of networked narratives on prejudice reduction, future studies should also consider the role of other factors, such as viewers’ pre-existing attitudes, demographic characteristics, and exposure to diverse content over time. Longitudinal research tracking viewers’ attitudes and behaviors toward outgroups before and after exposure to networked narratives could provide valuable insights into the long-term effectiveness of digital storytelling aimed at promoting positive intergroup relations.

Such research would also have a direct bearing on the emergence of trust. The present analysis primarily relied on quantitative data provided by YouTube Studio, such as view counts, traffic sources, and geographic distribution. Incorporating qualitative data, such as in-depth analysis of viewer comments and engagement patterns, or individualized tracking of long-term behavior in initially prejudiced people, could yield a more nuanced understanding of audience reactions and sentiments. To this, trust would need to be added, in both its emotional (reassurance) and rational (judgment) components. Future research could also explore the lasting impact of exposure to diverse cultural content on viewers’ attitudes and behaviors toward different ethnic groups. Longitudinal studies tracking viewer engagement and sentiment over time could offer valuable insights into the effectiveness of such content in promoting intercultural understanding and reducing prejudice.

Our findings suggest the potential importance of storyteller engagement and trust in networked narratives for prejudice reduction. Future research can directly measure trust and its influence on viewer attitudes toward cultural outgroups in networked narratives through surveys or behavioral studies.

While the focus of network narratives was on context through this action research involving meeting ethnic communities around the world, we have found that by approaching cultural outgroups as friends, we can truly appreciate their diversity and recognize their humanistic value.

There is a profound human value that binds us with collective emotion and boundless generosity, such as that expressed in empathy. This value, transcending the grasp of language, is something we can experience through meaningful interactions. While the digital world may not fully convey this value, it can certainly guide us in the right direction. Digital media networks were initially designed to create environments for individuals to form healthy bonds across diverse cultural and geographical contexts—an ethos we should strive to revive. By better understanding networked narratives, we can design environments where humanity connects full-heartedly, bringing individuals together rather than amplifying animosity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/soc14090192/s1. We are sharing the raw data exported directly from YouTube Studio that were used for the analysis of the three videos. Table S1: Top 10 regions of user traffic, Table S2: Traffic sources of the three videos, Table S3: Search keywords and average view duration (AVD), Table S4: Recommended videos.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K. and J.K.; methodology, D.K.; software, D.K.; validation, D.K.; formal analysis, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.; writing—review and editing, D.K. and J.K.; visualization, D.K.; supervision, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chapman, A.; Dilmperi, A. Luxury brand value co-creation with online brand communities in the service encounter. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 902–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V.; Ryu, E. “I’ll buy what she’s #wearing”: The roles of envy toward and parasocial interaction with influencers in Instagram celebrity-based brand endorsement and social commerce. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotun, S.; Lamarche, V.M.; Samothrakis, S.; Sandstrom, G.M.; Matran-Fernandez, A. Parasocial relationships on YouTube reduce prejudice towards mental health issues. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathje, S.; Van Bavel, J.J.; van der Linden, S. Out-group animosity drives engagement on social media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2024292118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odell, J. How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy; Melville House Publishing: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Varennes, F.d. Tsunami of Hate and Xenophobia Targeting Minorities Must Be Tackled, Says UN Expert; United Nations Human Rights: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2021/03/tsunami-hate-and-xenophobia-targeting-minorities-must-be-tackled-says-un (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.W.; Hsiao, C.H.; Sung, P.Y. Effects of YouTube advertising on intergroup contact: An experimental study. J. Advert. 2024, 53, 203–222. [Google Scholar]