Abstract

Specific aspects and territorial characteristics of migration have been extensively studied, while the primary living conditions of foreigners have been less compared in-depth. Using data from the Labor Force Surveys and EU-Silc for the year 2019, relating to six key aspects of daily life, in this study, foreign-born people living in the five main European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom) and the European Union were compared for the frequency of costs (e.g., for welfare services) and benefits (e.g., for employment) for the host society. Subsequently, the comparison of them, made by juxtaposing natives and non-natives, allowed for a definition of the level of primary integration (distance of immigrants from natives on the same aspects). The results show that the degree of congruence between the frequency of costs and that of benefits in the immigrant population is strongly influenced by the economic situation, favorable for Germany and the United Kingdom in 2019, with a lower recurrence of hardship cases among immigrants, but high wealth did not automatically reduce their differences. Instead, a small gap between immigrants and natives may also be due to the progressive impoverishment of the latter (Italian case). Therefore, especially in periods of economic stagnation, the different impact of it and of welfare measures on the immigrant population compared to natives requires the analysis of their actual living conditions, as the traditionally used economic aggregates (especially GDP) do not reveal the disparities in the distribution of resources between the various social and ethnic groups.

1. Introduction

The political and social upheavals in North Africa, induced by the so-called “Arab Springs” in 2011, have accentuated and led to continuous emigration to Europe from the northern and central African regions. Added to this are the Asian migratory currents mainly caused by wars and inter-ethnic conflicts in the Middle East, Afghanistan and certain interior and border regions of Pakistan. Such a transfer of foreign ethnic groups into European societies has profoundly changed their internal structure, and although immigration can contribute to collective wealth, it entails, especially initially, costs and a consumption of public resources [1] for the receiving society (more frequently for initial reception, learning the national language, starting work through training initiatives, and support for housing autonomy). This has forced individual countries to redistribute funds among the different items of the national budget and to find additional resources, taking into account the financial constraints imposed on the public finances of the member states by the European Union [2], temporarily reduced in the 2020–2023 pandemic period, with direct repercussions on the financing of the services offered to citizens. No less pronounced have been the difficulties of the UK’s public budget since leaving the European Union.

Hence, an appropriate and efficient use of available public resources is necessary, which requires, first of all, the knowledge and quantification of the recurrence of basic needs that are not met autonomously by immigrants and the native population in the specific European society to which they belong. In fact, it will be mainly the welfare state services of the host country that will take care of them [3], so their presence and activity with respect to migration issues should be a component of organic, targeted and sustainable migration policies, oriented towards bringing the living conditions of foreigners closer to those of natives.

Numerous indicator systems dedicated to migration phenomena are now available [4,5], which vary in the specific aspects observed, the number of countries considered and the span of years surveyed. Among the most authoritative, the Demig POLICY (Determinants of International Migration POLICY) database may be mentioned [3,6], constructed by the International Migration Institute and the University of Oxford, which analyzes changes in migration policies (immigration and emigration) of 45 countries, which have occurred in response to changes in migration flows. In 2015, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), through the Migration Governance Framework (MiGOF), defined the characteristics of a “well-managed migration policy” [7] at the national level, which is necessary to ensure humane, orderly and beneficial migration for migrants and the receiving society. In an effort to assess the management of migration by individual IOM member countries in compliance with the MiGOF principles and goals, indicators of migration governance (MGI) were subsequently developed, directed at assessing the comprehensiveness of national migration policies, their gaps, and their priorities to be addressed, in order to achieve what is envisaged by SDG Target 10.7 (security, regularity and orderly management of population movements) [8] of Agenda 2030 [6,9].

The legal implications involved in migration processes, on the other hand, have been explored in depth by the international program IMPALA (The International Migration Policy and Law Analysis) [10], while on the social side, the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX 2020) [11], with a unique indicator, measures the effectiveness of immigrant integration policies in 52 developed countries, including the member states of the European Union. The social condition of immigrants finds a more in-depth examination in the periodic Settling in reports [12] of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) which, using data from sample surveys conducted in member states, show the results of their integration policies with regard to employment, education, social inclusion, active citizenship and social acceptance of received immigrants and their children. These five areas also structure the 46 European Union indicators inspired by the “Zaragoza Declaration” [10,13], defined between 2010 and 2013 and adopted to monitor and improve the comparability of integration policy outcomes at the European, national and regional levels.

Narrowing the focus to the European context, despite this variety and multiplicity of indicators dedicated to the condition of immigrants, the European Court of Auditors itself highlights their limitations, from their narrow and non-systematic use to the lack of quantification of the volume of foreigners living in critical situations [14]. Similarly, the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union already propose others in Regulation No 1301/2013 on the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) 2014–2018 [15]. For that reason, it is necessary to identify a system of indicators that are not inhomogeneous, but are correlated and focused on the aspects that have the greatest impact on the daily quality of life of immigrants, as well as being easily available, determinable, of limited number and of real benefit to those responsible for planning and evaluating interventions and policies (including local) in the field of migration. If, in fact, there are areas such as health care, pension benefits or basic demographic characteristics (age, gender, citizenship, etc.) that imply for both immigrants and natives an administrative registration of individuals, other phenomena related to migratory flows should not be overlooked which, due to their fragmentation, different legal nature, and plurality of social agencies involved, are not fully and organically detectable administratively and require structured sample surveys to be defined and for their recurrence to be recognized.

In addition, it should be remembered that sample surveys, without neglecting their critical aspects [16,17,18,19] collect field data of both registered households and households not represented or only partially represented in public registers, so as to be able to intercept events that have not yet been reported to public authorities and that may not be reported in the future. These non-formalized facts are nevertheless reflected in the material living conditions of immigrants, contributing to the possible problematic aspects of their integration into the host society, which inevitably constitute a cost for the latter, for example, in the form of economic aid, in parallel with the benefits they normally bring to it, especially through their work. In a broader and more comprehensive perspective, this balancing of disadvantages and benefits should be considered for all parties involved in the migration process, from the individual migrating, to their country of origin, to the country of destination [17,20], which, for migrants not originating from the old continent, is almost always achieved after long and perilous journeys by land or sea, or by crossing both.

Restricting it to immigrants’ destination countries, such a balance between the burdens and advantages of migration should first of all concern the fundamental existential aspects (work, housing, essential public services, socializing, etc.), which are the basis of civil coexistence in any advanced society, not only European. An immigrant subject who has become economically autonomous, especially through direct and indirect taxation, can contribute to financing these needs, which will arise in immigrant individuals who, even for limited periods of time, are unable to provide for their basic needs themselves. A similar consideration can be made for the native population.

Also demonstrated by the periods of severe economic recession (think, for example, of the years following the financial crisis of 2008), when the frequency of contributions of resources for these needs tends to reduce and is accompanied, instead, by a sharp increase in the demand for them, due to the extension of cases of social hardship, an imbalance is produced between the funds set aside and those to be given for interventions and support of various kinds intended for those who have fallen into a state of need. Accordingly, in the case of immigration, an imbalance between benefits and costs is generated in the host country when a low frequency of resources provided by those who have immigrated to it is combined with a high recurrence of immigrants who request them, a condition that undermines the sustainability of the immigrant population settled in a country in the short term.

The existence of this equilibrium must be produced, in the first place, for the fundamental existential aspects, which cannot be ignored in order not to fall into the condition of deprivation, and requires that there be individuals who contribute to each specific aspect a quantity of resources at least equal to those that are taken away from them by other individuals who, for various reasons, need them. Consequently, an imbalance is generated when a low frequency of the former is accompanied by a high recurrence of deducted resources, a condition that undermines the sustainability of the immigrant population settled in a country. In these cases, few immigrants would have to bear the social costs induced by many immigrants.

It should be underlined that, through the two sample surveys examined, the recurrence of positive or negative existential conditions among the immigrant population and within the native population was reported by the immigrants and natives themselves who constituted the sample, so that even the economic repercussions of the migratory presence in a country were not considered using traditional national accounting criteria (GDP, transfers to the pension system, remittances, etc.), but for their peculiar reverberations on immigrant families. The data analyzed are therefore the voice, for example, of that large proportion of immigrants who are employed in tasks that are currently considered unattractive by the native population, sometimes underpaid, or carried out in less than hospitable environments, or without a long-lasting or regular contract—just as they also refer to that share of foreigners who bear onerous rents compared to their income, or who go through periods of socio-economic difficulty. In this way, economic and social trends (primarily the interventions of the welfare state) are grasped for their real and different effects they have on the immigrant population and on the natives, ordinarily generated by an unequal distribution of the resources collectively produced but also by the access to services and goods of a public nature, a fact often relegated to the background by social communication, which is more interested in directing the attention of public opinion to information on general economic trends and large public investment programs.

On the basis of these premises, the ratio of benefit-generating and cost-generating immigrants can be considered an index of the short-term social sustainability of the volume of immigrants who can be assured of a minimally acceptable standard of living in the host country.

To define the value of this equivalence between social costs and benefits, this study investigated its prevalence in foreign-born and native-born population of each of the five most populous countries in Europe and the EU as a whole. In particular, using national banking sources and drawing on the results of some large European sample surveys, whose data were subsequently statistically explored through correlation calculations and correspondence analysis, the present study had the following objectives:

- -

- Identify the aspects that decide the daily living conditions of immigrants, defining their scope and reciprocal relationships;

- -

- Determine, for the various aspects identified (level of education, work, household expenses, etc.), the recurrence of costs and benefits, derived by individuals of foreign origin, which flow to the country in which they have settled, as well as a quantitative measure of the complementary advantages/burdens (difference between the frequency of costs and that of benefits) brought by them to the host country;

- -

- Quantify, in the identical way and for the same aspects, the magnitude of the corresponding complementary advantages/burdens procured by the native population, with a subsequent comparison of the complementary advantages/burdens of the latter with respect to those of foreign origin.

Underlying the above-mentioned objectives are the two powers that inspire them and that will have to be verified:

- -

- Subjects of foreign origin, even if they come from another European country, generally experience a certain distance of their existential condition from that of the native population, a fact that will determine the steps in their life path, starting from the ability to cope autonomously with basic living needs (housing, payment of household supplies, access to work, etc.), which the majority of natives can face with greater resources, capable of satisfying higher-level needs (living in more comfortable neighborhoods, greater home comforts, etc.). Thus, the generally lower availability of resources of foreign groups compared to natives suggests that the primary aspects of existence have a greater weight for the immigrant population than they have for natives, who can use part of their resources for goods and services of a higher order, selected according to individual preferences.

- -

- With reference to the living conditions of natives, the generally higher availability of resources compared to the immigrant population allows them both to use them to a greater extent for goods and services of a higher level than the strictly primary ones and to increase the quality of the latter, so it is to be expected that the native population will differentiate itself more internally with regard to the satisfaction of the priority needs considered in this study, given its wider possibilities of choice.

The pursuit of the above objectives will make it possible to specify and validate the recurrence and the relationship between the different cases of cost and benefit found in the immigrant population. This knowledge cannot be ignored for an objective determination of the social sustainability of the foreign presence in a given country, but also indicative of its ability to receive new migratory flows. Similarly, the difference between contributions and requests of resources attributable to foreign-born individuals and to the native population satisfies the comparative principle that should lead to the equalization of individuals of different territorial backgrounds [21], at least with respect to the fundamental existential conditions, for a primary integration of the foreign population that has become part of a given society. This study can thus show, through the comparison of homogeneous and interconnected elements, the condition of foreign ethnic groups present in the five countries examined and throughout the European Union, information necessary for the planning of adequate actions within them that are aimed at resolving the critical issues that have arisen in the fundamental areas of existence, but also for conscious migration policies at the EU level, firstly, for an objectively weighted relocation of asylum seekers.

2. Methods

In this study, the primary aspects of the existence of persons of foreign origin and the native population, corresponding to the ordinary and indispensable needs of life in the society to which they belong, were circumscribed by first analyzing the data on family budgets published between 2015 and 2019 by the national central banks of the five largest European countries considered, i.e., France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom (UK), which in 2019 was still a member of the European Union.

The information obtained made it possible to identify income, monetary transfers received from local or national public institutions, housing, employment and education as the main factors determining the circulation and volume of available household resources.

Similarly, data from the Labor Force Survey (LFS) [22] and EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-Silc) [23] sample surveys relating to the year 2019, published by Eurostat [24], also made it possible to recognize the incompressible family needs that generate outlays of resources, as well as to know the share of individuals (foreign-born and native-born) who experience difficulties of various kinds in one or more of the aforementioned primary areas of their life. With regard to immigrant individuals, being born in another country normally exposes them to greater hardship than subsequent generations born in the host country, regardless of whether or not they have acquired citizenship of that country. In addition, in the different European countries, the age and the method of acquisition of citizenship of the host state vary, so that the criterion for the recruitment of the immigrant survey units to be analyzed was the birth in a foreign territory and not the citizenship [9,12].

Subsequently, by coordinating the above-mentioned essential existential areas, the following fundamental and interdependent aspects were defined that determine the life of immigrants and natives between the ages of 18 and 64 (or, in some cases, between 15 and 64 years of age), which generate costs or benefits for them or for the country in which they reside:

- -

- The level of education, which can translate into a cost factor of some importance in the case of immigrants who are unemployed and have an education not exceeding the compulsory schooling required in the country of residence;

- -

- Employment or inactivity;

- -

- Possession and adequacy of the inhabited house;

- -

- Regularity in the payment of the costs of providing services related to the use of one’s home;

- -

- Disposable income and absence of risk of poverty;

- -

- Existence or lack of a minimum level of material goods and participation in social or recreational activities.

The quantitative analysis of these aspects was conducted by associating each of them with specific variables capable of detecting them, indicated in Table 1, whose percentage values (see Table 2) were taken from the aforementioned LFS and EU-Silc surveys referring to individuals of working age, i.e., with an age range between 18 and 64 years or, for some variables, between 15 and 64 years, in relation to access to and permanence in the labor market, which generate costs and benefits for them and for the country in which they reside. Table 3 reports the values of the same variables detected in the natives. The educational levels correspond to the classification of educational qualifications contained in the current version of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) [22,25]. From the perspective of assessing the costs and benefits associated with immigration, as regards the basic educational level, attention was focused only on those who did not have a higher one and were without employment, as this status required onerous interventions burdensome for the receiving society, which had to take on a demanding education and professional qualification path to make them employable.

Table 1.

Aspects considered and corresponding variables.

Table 2.

Percentage and absolute values (income) of the variables detected in the immigrant population. Year 2019 (Source: Eurostat, [21,24]).

Table 3.

Percentage and absolute values (income) of the variables detectedin the natives. Year 2019 (Source: Eurostat, [24]).

As for labor activity, the active population aggregates employed and unemployed people (or first-time jobseekers), while the inactive grouping includes those who do not belong to the active population, as reported by Eurostat [23,26], in accordance with the definitions of the International Labor Organization. The absence of work or sufficient and continuous sources of income can lead to the risk of poverty (disposable income not exceeding 60% of the national median income) [24,27]. Finally, the contents of the other aspects observed are included in Eurostat’s definitions: conditions of housing overcrowding (unavailability of a minimum number of rooms for the household) [25,28], excessive incidence (overburdening) of total housing costs (possible rent, in addition to energy supplies, condominium or ancillary running costs, insurance premiums, etc., exceeding 40% of disposable household income) [26,29], and material and social deprivation (limited access to certain essential food, personal and household goods and social or recreational activities) [30,31].

For the five European countries observed and for the EU, using the statistical package R, the correlation coefficients between these variables were calculated, which was followed by an analysis of the correspondences, which made it possible to visualize their mutual position. This procedure was then replicated for the native population residing in the same territories. Once the significance and magnitude of the inertia (explained variance) of the variables introduced were verified, for each aspect, one or two variables and their opposing modalities were identified, representative of the entire working-age population explored by them, which always entail a burden or an advantage for the society in which the immigrant has settled. For all aspects, the sum of the difference between the recurrence of costs and the frequency of benefits for each of them showed the frequency of cases that cause burdens and those that generate benefits for a certain country and the EU territory. From the calculation of the ratio between these two flows of resources (“chances” and “risks” for integration) [32], a value was derived that can be considered as the social weight exerted by the migratory presence in specific national and EU contexts, at the basis of the effective sustainability of current immigration (and, consequently, also of future immigration), which was finally summarized in a punctual value for each country studied and for the EU.

Likewise, on the basis of the same variables, the recurrence of costs and advantages among the natives present in the six territories examined was calculated. The sum of these internal differences in each aspect, measured among the natives, compared with the corresponding difference among immigrants, made it possible to obtain an index of distance, in terms of the diffusion of costs and advantages for the native country (and with reference to the EU), between the condition of the natives and that of individuals born abroad, characterized by their own contributions and subtractions of resources towards the country to which they immigrated (or in relation to the EU). The calculation of the inverse of this range gave rise to an index that can be considered a measure of the primary integration of foreign-born individuals, i.e., relating to the indispensable elements for a non-deprived existence in the host social environment.

3. Results

This section presents the main findings concerning the existential situation and the reception capacity of migratory flows in the individual countries considered, as well as comparisons between the living standards of immigrants and natives.

3.1. The Condition of Immigrants

Table 4 presents the linear correlation coefficients obtained for the six European territories examined through the previously indicated variables. Firstly, the closeness of the living conditions of those who immigrated to Spain, France or Italy is quite evident (correlation coefficients above 0.80), while the similarities between the existential situations experienced by foreigners in Germany, France and the United Kingdom were less similar. In particular, although Germany and the United Kingdom experienced a period of sustained economic growth in the decade 2011–2019, the social integration of migratory flows within them was not similar, as their economic systems have different characteristics and needs (the German industrial apparatus, which requires technical skills, compared to the development of the British tertiary and financial sector, which mainly employs personnel specializing in direct services to businesses, communities and individuals [33]).

Table 4.

Pearson linear correlation matrix relative to the observed territories (year 2019).

In the case of France, however, the daily life of foreigners arriving on French territory shows a much closer proximity to the condition of immigrants in Germany than that which was found for Germany itself with Spain and Italy. Furthermore, in migratory terms, Germany turned out to be the closest country (with a correlation index of 0.42, among the five countries considered) to the average value estimated for the entire European Union for the year 2019, which represented the dominant trend in the EU territory.

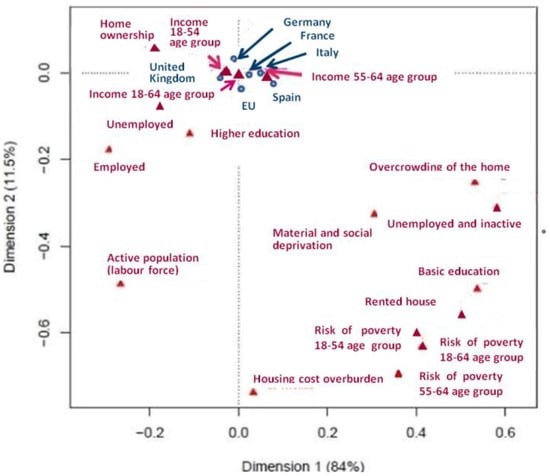

With respect to the relationships between the individual variables, the strength and pattern of their correlations were confirmed by the analysis of the principal components, which provided the configuration of their links shown in Figure 1. It immediately highlights the fact that the first two factor dimensions can explain more than 95% of the overall inertia (i.e., total variance) of the entire data distribution. The model of the six aspects focused on the fundamental needs of the existence of immigrants was thus able to reflect a set of areas of their real life that influenced each other and imposed themselves on higher-level needs, which turn out to be marginal in their daily life experience. Specifically, the horizontal axis of the graph explained 84% of the total variability (p-value: 0.0013), while the vertical axis reflect 11.5% of the same (p-value: 0.00018), so that the 17 variables considered appear to be almost entirely based on these two underlying dimensions.

Figure 1.

Correspondence analysis graph of the global model related to the 17 independent variables (in red) and the six dependent variables (in blue) observed in foreign-born individuals (year 2019).

As for the horizontal axis, on the one hand, it points out the housing inadequacy of those who came from other countries and had a low level of education, or personal or family limitations that distanced them from the labor market, especially in Italy and, to a lesser extent, in France. On the other hand, in the United Kingdom and Germany, most immigrants had work from which they derived sufficient resources to live without particular deprivation, and were more active in the labor market, committing themselves to seeking work if, temporarily, they were not employed, so their inclusion in the inactive segment of the population was very limited.

Differently, in the second axis (vertical axis), the risk of poverty in all age groups, which made the cost of rent and other services connected to the use of the inhabited house onerous, is contrasted with the ownership of it by foreigners with an adequate income guaranteed by a generally continuous working condition. It was mainly immigrants in Germany and, less frequently, those who arrived in the French territory who enjoyed a better patrimonial condition (in terms of home ownership and income), when instead it was mainly in Spain that the marginal situations of people of foreign origin manifested themselves, more often without a job, with little education and housed in cramped dwellings.

From reading Figure 1, it emerges that immigrants differed from each other mainly due to the fact of having a job, even if, in many cases, discontinuous, or, on the contrary, for different reasons (personal, family, social, religious, etc.), of finding themselves in a condition of inactivity, in which immigrants with low levels of education were more frequently involved. Less significant, although not negligible, was the gap between immigrants in terms of available resources, which pitted a minority of them on the poverty line and a consequent and recurring difficulty in covering housing costs, with a small number of other immigrants who, conversely, enjoyed sufficient and long-lasting incomes to become owners of the house in which they had settled.

Having ascertained the ability of the model of the six primary aspects of existence to accurately represent the fundamental needs of the foreign-born population settled in the territories studied, we proceeded to determine appropriate indicators capable of translating what emerged from the variables used into timely terms. Thus, for each of the six aspects considered, applying the cost–benefit criterion, the attributes that determined burdens and others that, conversely, led to an increase in resources for the social or economic institutions of a country or, at least, to a saving of them, were identified. For example, in the case of home ownership, one can mention the municipal property tax (tax paid by the home owner), while in the case of rented houses, tax deductions granted to disadvantaged categories of tenants (low income, large families, place of work far from home, etc.). (citizens below certain national established income limits, young families, individuals who must periodically move elsewhere for work carried out far from their place of residence, etc.), much more frequently in the immigrant population. This translates into a dynamic flow of resources that generates a cost for society when there is a monetary provision, or concessions for public goods or services in favor of the immigrant, which constitute an advantage for them.

In contrast, the transfer of resources from the immigrant to national or local public institutions, mainly through direct and indirect taxation, results in a benefit for public authorities and a burden for the foreigner. Following this approach, for each of the six aspects considered, among the 17 variables analyzed, one or two were selected that were exhaustively representative of the aspect itself and their relative opposites (e.g., home owned and home rented) in order to summarize the aspect considered. In Table 5, the variables thus identified were defined by the frequency of cases that bring costs (charges) or consideration in the form of actual benefits of various kinds, especially in relation to direct taxation, indirect taxation, and growth in demand for goods and services in a given country or the EU (the low level of personal education was crossed with unemployment status, due to the public economic burden required to qualify the individual).

Table 5.

Percentage frequency distribution of charges and usefulness related to the six aspects observed in the foreign-born population in the five largest European countries and the EU (year 2019).

The data in Table 5 highlight the favorable living conditions of most of the population of foreign origin received by the German society, to which they have brought limited costs as there have been very few states of need requiring its intervention. The low number of homeowners, with the consequent burden of rent on immigrant families, also does not seem to have affected the overall family situation much, not having strong repercussions on other basic existential needs. The position is different for individuals of foreign origin in Spain who, while maintaining a positive contribution to the host society (confronting the frequency of benefit cases with the recurrence of cost cases), in many areas of their lives, experience difficulties that require public intervention. Compared to the average of the other countries studied here, of particular note is the frequent low educational level of individuals of foreign origin, which was repeatedly associated with a state of unemployment or inactivity, as well as the extensive risk of poverty, the burden of rent and other housing expenses, and the notable recurrence of cases of material and social deprivation.

As for France, especially on a quantitative level, the situation of the population of foreign origin present in its territory appears better, as it has been less involved in housing problems In fact, their frequency was in line with the European average, while compared to it, the availability of resources to independently cover the costs of rent and costs associated with the use of one’s home was much greater. This was contrasted, however, by the high share of unemployed and inactive people, the highest of all the countries observed, accompanied by the strong extension of material and social deficiencies and, to a lesser extent, the risk of poverty.

In the neighboring Italian territory, however, the critical issues are associated with some specific needs, which have remained highly unsatisfied. In fact, in Italy, foreign-born individuals were heavily affected by housing problems, both because of widespread rent costs and the inadequacy of occupied housing in relation to family size (with a percentage twice the EU average). Another critical issue, common to Mediterranean countries (Spain and France), was the high level of unemployed or inactive individuals, without underestimating the existence of an irregular labor component that may have escaped sample surveys. On the opposite side, in terms of employment, was the United Kingdom, which had the highest rate of employed foreign residents and the lowest number of foreign individuals who did not participate in the labor market. The positive performance of the British economy in the second decade of the 21st century has allowed immigrants to frequently experience a good, or at least not distressed, living condition, similar to what has occurred in Germany.

Compared to those who immigrated to Germany, a slightly higher share of the employed foreign population emerges in the UK, which is accompanied by a slightly lower housing need. But in comparison with people who do not come from British society, individuals of foreign origin present in Germany seem to have less difficulty coping with the cost of housing and, with a smaller gap, material and social deprivation and the spread of poverty risk are also lower

Finally, at the community level, the condition of people not originally from the state to which they immigrated reflects this polarity of situations, ranging from frequently meeting their basic needs in Germany and the United Kingdom to more problematic integration in Spanish, French and Italian society, with widespread cases of hardship in many areas of existence. In this sense, the two issues that seem to impose themselves most at the community level concern the burden of rent, and more generally, the costs of using a house, and the risk of poverty, already relevant in 2019 and exacerbated in the early years of the third decade of this century by rising energy prices and inflation.

In order to briefly represent the weight that all cost components have with respect to the set of advantage components attributable to the migratory presence in a given country, the congruence between them can be expressed in formal terms:

where MCIk is the congruence index for a given country; yi is an element (indicator) of utility associated with one of the six aspects observed for that country; and xi is an element of charge associated with one of the same six aspects.

Migration congruence index: MCIk = nΣ i=1 (yi)/nΣ i=1(xi),

Thus, for 2019, such a congruence index can take the following values:

3.44 for Germany (492.6/143.0);

1.63 for Spain (400.1/244.9);

2.11 for France (434.4/206.1);

1.69 for Italy (410.9/243.0);

3.08 for the United Kingdom (466.0/151.2);

2.29 for the European Union of 28 member states (442.1/193.2).

The results of the calculations clearly show how an increase in the frequency of critical cases (lower index value) fatally decreases the value of benefits brought by the presence of immigrants for the host country. In this way, one can arrive at a cost–benefit frequency equal to 1, in which in the immigrant population there is a percentage of cost cases equal to the recurrence of their contributions of resources to the society of which they are part (therefore, if this ratio were less than 1, the volume of costs would exceed that of benefits).

Consequently, the closer the ratio is to 1, the more the possibilities of welcoming new foreigners shrink, since the same immigrants present in a certain country produce a propagation of costs for the host society that would largely exhaust the flow of benefits generated by them. In this sense, an index value of 1.63, found for Spain (or 1.69 for Italy), implies that for every immigrant already present who generates a cost, there are 1.63 foreigners who procure a benefit. So, the difference between how many individuals of foreign origin bring costs and those who bring benefits, here equal to 0.63 and thus less than the value 1, implies that the benefit derived from an immigrant already included in the society that sheltered them would not be sufficient to meet the burden actually required for the inclusion of a new immigrant. Quite different, however, is the situation in Germany, which has an index equal to 3.44, whereby a foreign national who brings a cost to German society is matched by 3.44 immigrants from whom, on the other hand, it derives a benefit, which translates into the possibility of potentially receiving 2.44 (3.44-1) foreigners for one immigrant who has already joined.

3.2. Comparison of the Life Situations of Immigrants and Natives

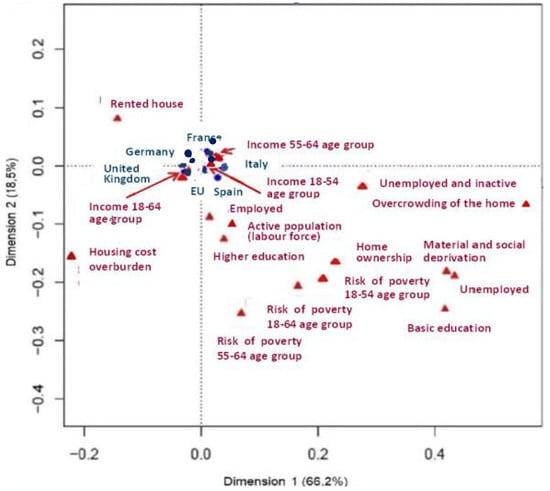

The aspects considered in relation to individuals of foreign origin refer to conditions and behaviors that cannot be ignored by any human community, whether immigrant or native, as they are indispensable factors for physical survival and personal autonomy in the host society. Hence, they have been taken as a basis for a comparison between the native population and that of foreign origin, with the aim of defining a measure of the distance between their basic existential conditions, a difference that can constitute a parameter of the degree of primary integration achieved by immigrants, the foundation of the equality of the standard of living between different communities also desired at an international level for integration policies [12,34]. In this perspective, Graph 2 visually shows the structure of the fundamental existential conditions referring only to the population born in the State in which they reside (regardless of whether the individual was born into a native, immigrant or mixed family), represented through the technique of the correspondence analysis, as for the analogous graph made for the population of foreign origin.

The generated graph shows that the first two factors, taken together, explain about 84.7 percent of the inertia of the entire data distribution (with a p-value of 0.0007 for the first axis, which reaches a value of 0.0002 for the second axis), compared with 95.5 percent of the inertia explained overall by the first two dimensions in the case of the immigrant population (Graph 1). With that, it can be an empirical demonstration of the fact that immigration is part of a system of living conditions and social needs in which the inequality between the natives themselves has already been consolidated, normally higher than the disparities that arise between individuals of foreign origin, despite their cultural differences. It follows that where the distances between the people of the country of immigration are more deep-rooted, migratory pressures will only aggravate them, creating fertile ground for the formation and public expression of social tensions between the different ethnic communities.

As for peculiarities of the native individuals present in the five observed countries and in the EU, the first axis of this second graphical representation, to which 66.2 percent of the variance produced by the studied variables can be ascribed, opposes the cases of housing overcrowding detected in the native citizenry, concentrated mainly in Italy, and the high incidence of housing cost overburden, which were much more frequent for natives who resided in Germany than the EU average. Otherwise, the second axis, to which 18.5 percent of the total variance can be ascribed, places the limited number of Spanish natives who lived in rented housing in an inverse position to the lower prevalence, with respect to the territories examined, of poverty risk among French natives in the closing years of their working age.

Thus, compared to foreign-born individuals, for whom labor market participation has played a decisive role in differentiating them, inequalities among native individuals are more articulated. In particular, among the latter, it is, above all, the house that marks the differences, since when it is not owned (remembering that the ownership of the house is very extensive) it increases the weight of rent and the expenses associated with it, as well as the tendency for the inadequacy of its size compared to the size of the family, especially in the presence of other factors of social weakness such as the state of unemployment and the risk of poverty in old working age (55–64 years). That is, the underlying orientation of the native population to converge toward an average living situation does not occur homogeneously, as individual and family conditions are more heterogeneous and varied, although cases of economic hardship within it are more reduced. Unlike natives, for those coming from a foreign country, the impact of the six areas of life considered is more marked due to their greater repercussions on personal existence and the tighter material and social constraints on freedom of choice regarding the possible life alternatives (hence the close relationship between the variables previously described).

By superimposing Figure 1 and Figure 2, it is possible to circumscribe the situations that, by intersecting existential aspects experienced simultaneously by natives and immigrants, are most likely to generate tensions between different ethnic communities. In this regard, the most recurrent critical events occur, first of all, when the tenant status of the natives intersects with the overcrowding of housing by the foreign population, often with precarious jobs. Another fertile ground for possible inter-ethnic disputes is the coexistence in the same urban areas of foreigners living in rented houses and unemployed natives with basic education and who experience states of material deprivation and insufficient participation in social life.

Figure 2.

Correspondence analysis graph of the global model related to the 17 independent variables (in red) and the six dependent variables (in blue) observed in the native population (year 2019).

The comparison between Figure 1 and Figure 2 also allows us to verify the two hypotheses formulated in the present study. In this regard, the greater magnitude of the variance explained by the first two dimensions of the first graph (over 95%), relating to the population of foreign origin, confirms the prediction that their specific life situation limits their existential options, which will be determined mainly by their basic living needs and their reciprocal interactions. On the other hand, as mentioned earlier, other variables (above all, the generally higher income, but also age, better education, wider employment opportunities, etc.) differentiate the natives more from each other, so that the weight and reciprocal relationships between the essential aspects of existence have a more subjective character, less reducible to a model of mechanically reproducing correlations, a trend reflected statistically by the smaller amplitude of the variance explained by the first two dimensions of Graph 2 (over 84%).

Similarly to the synthetic index obtained regarding the congruence between burdens and advantages of migration flows, it was possible to identify, for the six existential aspects considered, a specific comparative index that highlighted the differences, and therefore the level of integration, of individuals of foreign origin compared to the native population, taken as a reference parameter. Table 6 below, which comparatively reproduces the structure of Table 4, shows the elements with which this comparison has been made. A reading of it shows that the most frequent disparities between the native population and those born abroad concerned housing, especially home ownership, with the percentage of natives owning a home being 30% higher than that of those born in another country.

Table 6.

Percentage frequency distribution of charges and usefulness related to the six aspects observed on the foreign-born and native-born population in the five largest European countries and the EU (year 2019). (In the “Immigrants” and “Natives” sections, the left column shows the “Charges” and the right column the “Usefulness”.).

Rent and overcrowding of homes, housing cost overburden and material and social deprivation were the other aspects that most marked the inequality between those born in the country in which they reside and those born abroad. In contrast, their differences in educational levels (especially university education), employment rate and income were reduced. Furthermore, immigrants appeared more involved than natives in temporary or irregular jobs, since, although their level of unemployment in working age (15–64 years) was decidedly higher, the sum of inactive and unemployed immigrants reached values close to those experienced by natives, also in terms of income, taking into account that the performance of the German economy allowed it.

The favorable economic situation in the UK tertiary sector has also improved the living conditions of those who have immigrated there. The more pronounced housing inequalities (low frequency of home ownership, rent burden, overcrowding, excessive housing costs compared to the benchmark defined by Eurostat) and difficulties in meeting normal material and social needs seem to be the greatest obstacles to equality of living conditions between foreigners and natives within British society, where a certain equality between different ethnic groups in relation to income has been established. The share of individuals at risk of poverty and with a university education is more common among foreign-born people than among native citizens.

The French situation lies halfway between the recurrence of elements that promote equality between natives and immigrants and those that widen the differences between them. In fact, for expatriates living in French territory, there is a certain equality in the spread of university education and in the size of the labor force, while there is still a marked disparity between natives and people of foreign origin in terms of unemployment rate, frequency of income received and risk of poverty. Not far from this condition is the Italian situation, where the elements of equality stopped substantially stopped at the employment condition (employment rate and insertion in precarious activities, often irregular or carried out with atypical contracts, which united natives and people of foreign origin) and where the enormous distance between immigrants and natives stood out in terms of the percentage of homeowners and the share of household expenditure compared to income available. Similarly, in Spanish society, the areas of life that affected the native population and immigrants equally were limited. In this country, natives and foreigners were broadly equal in primary education attendance and employment rates, while there were significant distinctions in the other aspects considered.

As far as the territory of the entire European Union (28 member states, including the United Kingdom) is concerned, from which the average value of the living conditions of immigrants present within its borders derive, the greatest distance between foreigners and natives has emerged with regard to housing. In particular, this is due to the difference between the share of housing owned by the two populations (natives were twice as likely to own a home as foreign groups), and considering cases of overcrowding of the interior space of the house. Secondly, the other aspect that most divided them was represented by the volume of economic resources available, revealed above all by the higher frequency of the risk of poverty and cases of material and social deprivation of immigrants compared to natives. But despite these limitations, people of foreign origin proved to be better able to manage their resources adequately, falling less than natives among those who had difficulty in meeting the costs of using the occupied housing.

Similarly to the synthetic index obtained regarding the congruence between burdens and advantages of migration flows, it was possible to identify, for the six existential aspects considered, a specific comparative index that highlighted the differences, and therefore the level of integration, of individuals of foreign origin compared to the native population, taken as a reference parameter. Table 6 shows that the most frequent disparities between the native population and those born abroad concerned housing, especially home ownership, with the percentage of natives owning a home 30% higher than that of those born in another country.

Wanting to summarize the specific national and EU situations by means of an index, one can calculate the distances within them that separate the different ethnic origins, as shown in column three of Table 7. This shows the distance between foreign-born and native-born individuals on the basis of the ratio between the recurrence of the burdens and benefits they bring to the host country (detailed in Table 5), starting from the assumption that the less inequality there is between different ethnic groups, as regards the distribution of the costs and benefits on which personal autonomy is based in the society to which they belong, the greater the integration at a primary level between the various components that make up the society.

Table 7.

Degree of inequality in the six aspects studied between native and foreign-born residents in the five largest European countries and the EU (year 2019).

In formal terms, one can translate this process of determining the level of primary integration of migrants into the following expression:

where PIMk is the immigrant primary integration index for a given country; yn is a utility element associated with each of the six aspects observed for those born in that country; xn is a burden element associated with each of the same six aspects observed for those born in that country; vi is a utility element associated with one of the six aspects observed for those born outside that country (or the EU); zi is a burden element associated with one of the same six aspects observed for those born outside that country (or the EU).

PIMk = 1/[(nΣ i=1 (vi)/nΣ i=1 (zi)) − (nΣ i=1 (yi)/nΣ i=1 (xi))],

Applying the above formula, one can calculate the distance of each country from a 0 point of full integration, yielding the following results, shown in tabular form in Table 7:

PIMGermany = 1/[(497.6/122.0) − (492.6/143.0)] = 1/(4.07 − 3.44) = 1/0.63

- PIMSpain = 1/[(535.4/97.5) − (400.1/244.9)] = 1/(5.49 − 1.63) = 1/3.86

- PIMFrance = 1/[(511.2/112.3) − (434.1/206.1)] = 1/(4.55 − 2.11) = 1/2.44

- PIMItaly = 1/[(500.7/140.9) − (410.9/243.0)] = 1/(3.55 − 1.69) = 1/1.86

- PIMUnited Kingdom = 1/[(518.4/102.2) − (466.0/151.2)] = 1/(5.07 − 3.08) = 1/1.99

- PIMUE = 1/[(508.1/117.0) − (442.1/193.2)] = 1/(4.34 − 2.29) = 1/2.05

We can consider the values obtained in this way as a measure of the integration deficit, indicative of the distance between the integration achieved and its maximum level, which zeroes the inequalities between the native population and the immigrant population (with no difference between them in the aspects studied here). Knowing this distance from the 0 point of parity between natives and immigrants from other countries, by transforming the values into its inverse, the primary integration indices of the different countries can be defined:

| PIMGermany | = | 1/0.63 | = | 1.59 |

| PIMSpain | = | 1/3.86 | = | 0.26 |

| PIMGFrance | = | 1/2.44 | = | 0.41 |

| PIMItaly | = | 1/1.86 | = | 0.54 |

| PIMUnited Kingdom | = | 1/1.99 | = | 0.50 |

| PIMEU | = | 1/2.05 | = | 0.49 |

It can easily be deduced that the higher the values of these indices, the smaller the difference between the native population and that of foreign origin in the aspects examined which, as they are essential for daily existence in a European society, can be considered the necessary requisites for primary (i.e., basic) integration within it.

In this sense, taking into account the specific national situations presented in Table 6, it is possible to clarify the reference reality they express. It follows that a value of 0.63 for the primary integration index for Germany, accompanied by high benefits attributable to immigration (first column of Table 7, with a value of 3.44 for Germany), is indicative of a high level of inclusion of individuals arriving from other countries, in a socio-economic context in which the presence of immigrants increases the well-being of German society as a whole. This results in minimum costs for income support measures for foreigners received, or for welfare interventions in their favor, mainly limited to the residential sector, for example, due to overcrowding of housing and rental costs.

The situation is different in Spain, whose the degree of inequality of 3.86 (Table 7, third column) highlights a significant gap between the living conditions of the native population and those of immigrants, who many times represent a burden for Spanish society (first column of Table 7 with a value of 1.63, recalling that at 1.0 the frequency of cost and benefit factors generated by immigrants are equivalent). In particular, in the Spanish case, immigrants are distinguished from native individuals by the greater prevalence in the former of criticalities linked to one or more of the aspects observed, starting with both the higher rate of the immigrant population that does not work (to which the low qualification of many foreigners also contributes) and the accentuated possibility of being on the poverty line, to which are added the limited access to home ownership, a certain overcrowding of the inhabited house and the sustainability of all housing costs, as well as insufficient resources for essential goods and services and for social life.

In contrast, the value of 2.44 for the degree of inequality for the French places the level of integration of those who have settled in France in an intermediate position compared to the other four countries. For French society, the cost–benefit relationship of immigration remains positive (first column of Table 7, with a value of 2.11 for France), but large influxes of migrants, without programs to make their stay in France productive, would reduce the value of the benefits brought by new immigration, putting France’s situation on a par with that of other countries (such as Spain and Italy) where the weight of migratory flows is difficult to manage and control. Compared to the conditions of the native population, immigrants experience lower participation in the labor market, a higher incidence of housing costs on the household budget and a higher level of material and social deprivation, resulting from the wide gap between their income and that of the natives, which is reflected in the spread of the risk of poverty, much more pronounced among those who come from another country.

In the Italian case, it emerges first of all that the gaps between the various immigrant communities and the local population are much less marked, as evidenced by the value of 1.69 in the first column of Table 7. This reflects the fact that, while bringing a certain advantage to Italian society, the migratory influx has increased the structural fragilities that pre-date the substantial migratory flows that began in the last decade of the twenty-first century. This is the basis for a degree of inequality of 1.86, which, after that of Germany, marks the closest proximity of conditions between natives and immigrants, even though their respective national socio-economic circumstances are very different. In particular, natives and immigrants share an accentuated share of individuals who seem to be excluded from the world of work (regular or unregulated), with the foreign component slightly more involved in productive activities than the natives, although among the former, the risk of poverty and the difficulty of meeting housing costs remain more frequent. But these specific shortcomings of the population of foreign origin are outweighed by the housing problem they experience, both in terms of the prevalence of renter status and the recurrence of residential overcrowding, which are the most relevant in the five countries surveyed, even when comparing the native national population to immigrants.

As far as the United Kingdom is concerned, beyond its current location outside the European Union, which, in any case, has not interrupted or altered migratory flows to its territory, together with Germany, it is the European country that has benefited most from the impact of immigrants between 2011 and 2019, with limited burdens for the British state, as evidenced by the value of 3.08 in the first column of Table 7, substantially limited to housing issues. However, in the comparison with Germany, the gap between the living conditions of the native population compared to individuals from other countries is greater, as evidenced by the value of 1.99 taken by the degree of inequality. In this regard, it should be mentioned that there is a higher prevalence of owner-occupied homes among native Britons and their low involvement in the problem of housing overcrowding, as well as the limited number of cases of material and social deprivation in which they are involved compared to immigrants, despite the latter’s frequently higher level of education.

Finally, the index relating to the European Union, which necessarily refers to the average living conditions of native citizens and immigrants residing in the territory of the Union but born in a country other than the one in which they reside, suggests the advantage for European societies of an organized and rationally distributed reception in the various member states. But this takes into account the real conditions that can make it profitable, so as not to accentuate the shortcomings already present in the various EU territories where the immigrant population has settled (a value of 2.29 for the European Union in the first column of Table 7). In the last decade, despite the growth of the immigrant population in Europe, the frequency of homeowners of foreign origin has not increased, who have therefore largely borne the cost of rent. The incidence of it and household expenditure, but also the low level of family income, have favoured the search for cheap housing by immigrant groups, often of limited size compared to the members of the family, with the consequent overcrowding of the home. These difficulties represent the main cost factors of the migration policies of the European Union as a whole. These are the main deprivations suffered by the most disadvantaged sections of the community population, which require onerous assistance interventions. The fact that immigrants are more frequently involved in these difficulties is also the reason for the gap between the living conditions of the former and the latter, summarized by a degree of inequality of 2.05 for the EU.

4. Discussion

The availability of a set of indicators that are reduced in number, easily available and calculable, and focused on aspects of existence that correspond to well-defined primary needs of everyday life [35,36,37], the satisfaction of which implies the circulation of social resources, remains a fundamental issue for the non-conflictual, or at least less conflictual, management of immigration by European societies with a larger foreign population. Indeed, as primary needs, they are experienced by the entire community occupying a given territory, composed of both natives and immigrants, so that in some situations, the problems of one may overlap with those of the other, fueling overt or latent tensions between the more disadvantaged native and foreign population groups. The social mobility of immigrants, while indicative of the greater openness of a society to other ethnic groups, is strongly conditioned by the system of social selection of the ruling class of a country (also with respect to individuals of local origin) and can coexist with the maintenance of widespread inequalities between different ethnic groups (the case of the black population in the United States is emblematic).

The social inequalities highlighted by the indices produced in this work appear to be indicative of the level of efficiency of national social and economic systems. In fact, apart from the ability of national welfare systems to intervene in them, which is also influenced by the specific power relations between the social groups in the different countries, the most efficient national socio-economic systems are capable of ensuring greater economic development (in the second decade of the 21st century, the German and British ones) to employ immigrants more productively and raise their standard of living, albeit rarely to a similar extent to that of the natives, and to obtain a better cost–benefit ratio linked to their presence. Otherwise, the lower efficiency of the national administrative and economic apparatus (e.g., with respect to the level of performance and procedural transparency of the public administration, the support of technological innovation, the control of the spread of undeclared work and the effective management of the migrant labor force) has translated into lower productivity indices of immigrant groups, as occurred above all in the South Mediterranean countries (Spain and Italy). Decades of demographic decline have made immigration’s contribution to the functioning of the social and economic structure of the major European countries indispensable, without this having promoted a corresponding renewal of the old national regulatory and organizational orders, whose frequent inadequacy increases the social cost of immigration, which could be reduced by removing the internal imbalances and inefficiencies still present, especially in some national social and economic systems.

Not surprising are the different living conditions among the same immigrants in relation to the distinct European country in which they settled, whose quantitative magnitude with respect to basic existential needs has been highlighted by this study. Hence, there is a need for systemic innovations as well as adequate policies and costly interventions, diversified for the various countries, to overcome the criticalities manifested by the foreign population (and by the more marginal segments of the native citizenship), but also the implementation of constant and capillary monitoring of their evolution, from which to draw objective indications on the necessity and reception capacity of future flows.

Secondly, in accordance with what has been underlined above, the comparison between the inequalities of the native community of a country with those of people of other ethnic origins has made it possible to verify that the good economic performance of a country, while it may increase the level of living conditions of the foreign population, does not have an automatic and equivalent impact in terms of reducing the differences between natives and foreigners as far as concerns the needs of citizens.

Consequently, the measures of the political system oriented towards greater control of the inequalities generated by the economic and social organization of a country, which tends to influence the same choices of political power, play a decisive role in the prevention of the frequency of disadvantaged situations in the immigrant population with respect to the recurrence of cases of deprivation in the native community (as the comparison between Germany and the United Kingdom has shown).

This is even more evident in the weak phases of a country’s economic cycle, which end up widening the gap between immigrants and natives, as the latter often become beneficiaries of welfare state interventions that mitigate the negative effects of economic stagnation, provisions that only to a more limited extent reach those who come from other countries, especially non-EU ones (as in the case of France and Spain). But when the welfare state’s contribution is deficient or insufficient, the condition of the native population tends to worsen and come closer to the generally more modest condition of immigrants, so that the distance between natives and foreigners also narrows, hence the apparent better integration of immigrant groups (Italian situation). This does not necessarily increase antagonism between ethnic communities, as immigrant groups perceive the difficulties of natives and the latter cannot reasonably blame the former for their condition.

It follows that each country has its own specific capacity and availability of resources to receive new migratory flows, which vary over time and involve both the economic and social dimensions (welfare services). Within these limits, it can guarantee foreign groups effective equality with the native population, at least as far as basic existential needs are concerned. In this work, by comparing native and foreign-born people with respect to these fundamental aspects of daily life, which entail burdens and advantages for the host society, it has been possible to determine a representative index of the degree to which, in the main European countries, a real integration of immigrants has been achieved relating to the basic components of their existential condition.

What emerged from this study implies for decision-makers and public managers that policies and interventions in the field of migration are able to act in a coordinated and not disjointed way on the basic needs of the immigrant population (from work, to housing, to maintenance costs) because in foreign communities they are more interconnected with each other than the interaction they can have for individuals in the native community.

This study has been limited to the observation of the aspects which ordinarily underlie an existence that is not deprived for those who come from another country but, of course, they do not exhaust the complex of events that can occur throughout an individual’s life. Health care, professional and social positions attained, adherence to religious faiths, participation in associations of various kinds, and judicial sanctions for unlawful conduct or facts are all phenomena, occasional or complementary to the factors that determine the basic conditions of personal existence in daily life, which can be experienced by both native and foreign populations. The social need to administer them has led to their transposition into public registers from which to start specific analyses, but there has frequently been a lack of coordination between different sources of administrative data and between them and the results of sample surveys. The latter, in fact, can capture new or unexpected events and phenomena in the making and provide an on-the-spot verification of public policies on migration, beyond the indicators produced by the institutions appointed to deal with it, which on many occasions are more attentive to the number of cases dealt with than to the effect of their work on the foreign subjects they have been entrusted with because they have arrived in their area of action.

Coordination between data of a different nature (in this case between administrative data and sample data) is not only functional to the territorial management of migratory flows, but also to their progressive integration and equalization with the native population. This requires, first of all, the removal of the criticalities that still characterize, as the study conducted shows, a not indifferent part of the immigrant population (and segments of the native population itself), especially in certain territories and with regard to certain aspects (mainly housing). Relieved of basic needs, as already represented in this work in relation to the native population, the immigrant (and the natives who shares their existential condition) can also cultivate other and richer existential levels of a cultural, relational, professional and economic nature. Social agencies and institutions (mostly educational ones), with their administrative data, will be able to show the evolution of the more formal aspects of this process (e.g., in the educational field, the courses attended), but it will be the field survey, and thus the sample survey, that will reveal how they integrate with other, more private or informal aspects (professional position, family home of appropriate size, leisure time, etc.), which bring the immigrant population’s living conditions closer to those of the native population, and thus enable effective integration.

This is without underestimating the limitations implied in the collection and evaluation of sample data. In this sense, in the analysis carried out here, an attempt has been made to reduce as far as possible the negative effects implicit in sample surveys by taking into consideration highly populated statistical categories (e.g., the entire employed population without further breakdowns by sub-category), which better guarantee that one can operate on data with sufficient control over their variability. Secondly, one should not overlook the difficulty, at the time of data collection itself, of intercepting those individuals who are less inserted in the social fabric of the places where it is carried out, and this concerns first and foremost foreign individuals as compared to native ones. For this reason, in order to compensate for the respective gaps, the joint and coordinated use of administrative data and sample data appears to be the best solution to capture the various aspects of the living conditions of the immigrant population and its evolution over time.

5. Conclusions

Generally, the impact of immigration on an advanced society is evaluated for the economic contribution it provides to the host country (e.g., participation in GDP growth, subsidizing national social security and health systems) [38,39,40,41,42,43], but the large financial aggregates of national economies alone do not shed light on the real repercussions that the migratory presence has on the population, in particular on the most disadvantaged segments of it. This fuels latent or expressed tensions which increase popular support for demonstrations and movements against immigration.

Furthermore, it should not be forgotten that migration is one of the ways in which the transfer of population from one geographical place to another manifests itself and that it may be this movement in itself, even before being recognized as a migratory flow, that can generate certain negative responses in those who live in a place reached by waves of foreign population. A clear example of this are the reactions, even recent ones (e.g., in some Spanish tourist locations), of people living in places with a strong tourist attraction (regardless of national origin), on whom the negative consequences of mass tourism fall (e.g., increased rental costs and expenses for local public services), despite the economic benefits it brings to some local economic sectors.

Migration phenomena, however, in addition to the spatial dimension, also influence and are influenced by the temporal dimension, since the needs of the near future may not be reconciled with the current socio-economic situation experienced by a given host territory. Thus, the foreseeable need for a new immigrant labor force, to cope with the aging and declining birth rate of the European population, may in the present run up against the problematic living conditions (inadequate housing, irregular work, low income, etc.) already endured by many immigrant families, especially in some European regions (e.g., the Mediterranean basin), as shown in this study.

Hence, the multiple and often conflicting interests and needs that, in space and time, come into play in the reception of foreign populations require an analysis of migration issues based on empirical and verifiable data, which oppose the facts and occurrences actually detected for the simplistic and performative rhetoric on migration that frequently populates the means of social communication, favored by the complexity of this phenomenon, which allows different conclusions to be reached depending on the perspective of observation taken.

In this sense, without underestimating their limitations, sample surveys appear to be a useful tool to observe the actual social consequences of immigration. But to be able to intervene, with scarce public resources, in those that have negative repercussions, it is necessary to select, within the many topics they deal with, some salient indicators relating to the recurrence of the factors that have the greatest impact on the daily lives of the native population and the immigrant population itself. It follows that each country has its own specific structural and organizational capacity to receive foreigners, to which it can guarantee effective equality with the native population, at least as regards the primary existential needs, which are the basis of its future improvements in the social position of immigrant groups. And the political decision-maker themself, more than for their formal positions manifested in the public debate on immigration (which naturally have their own weight in shaping society), should be considered for their impact on this capacity, which signals their actual direction in migration matters.

Having a small set of integrated indicators, capable of capturing the evolution of the fundamental aspects of life of those coming from other countries, may in the future allow them to be monitored in a coordinated manner, correcting any unbalanced trends that become apparent in a country (e.g., the relationship between the housing needs of new foreign workers, the income and available housing in the territory [44], within the local physical and human ecosystem [45]) in which they will settle and which they will contribute to forming.

Finally, at the territorial level, within the EU, the persistent difficulty and repeated agreements [46,47] between member states for the relocation of migratory flows deserving of international protection require the definition of significant, homogeneous and interconnected indicators. But for their measures to appear acceptable to the native population that will receive other immigrants (especially when the national economy weakens), they should be based on its actual living conditions, which can be reflected in the aspects such as those explored in this work. This is because the existential situation experienced does not necessarily correspond either to the GDP trend, which does not have a uniform distribution at a territorial level and with respect to the different social categories, or to the volume of the national population, which is currently the main criterion used for the distribution of legal immigrants among EU countries [45,48]. Similarly, at a national level, a coordinated set of aspects that refer to the basic existential conditions of the native community and immigrant groups living in a given region, within a country, will allow us to compare the needs and strengths of both the natives and the foreigners who populate it, from which to draw rapid, punctual and coordinated information on the capacity of the same territory to receive a influx of new immigrants.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

The data on which it is based was taken from the Eurostat website, in particular from its section dedicated to immigrant populations. Eurostat is the statistical institute of the European Union and is subject to the rules and controls of the latter’s bodies, Consequently, the data published on its website necessarily comply with European legislation on the protection of confidentiality of information (privacy) and statistical secrecy.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Brücker, H.; Epstein, G.S.; McCormick, B.; Saint-Paul, G.; Venturini, A.; Zimmermann, K.F. Managing migration in the European welfare state. Immigr. Policy Welf. Syst. 2002, 74, 1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, J.; Siter, J. The European Union budget and the European refugee and migration crises. OECD J. Budg. 2018, 17, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]