New Globalization and Energy Transition: Insights from Recent Global Developments

Abstract

1. Introduction

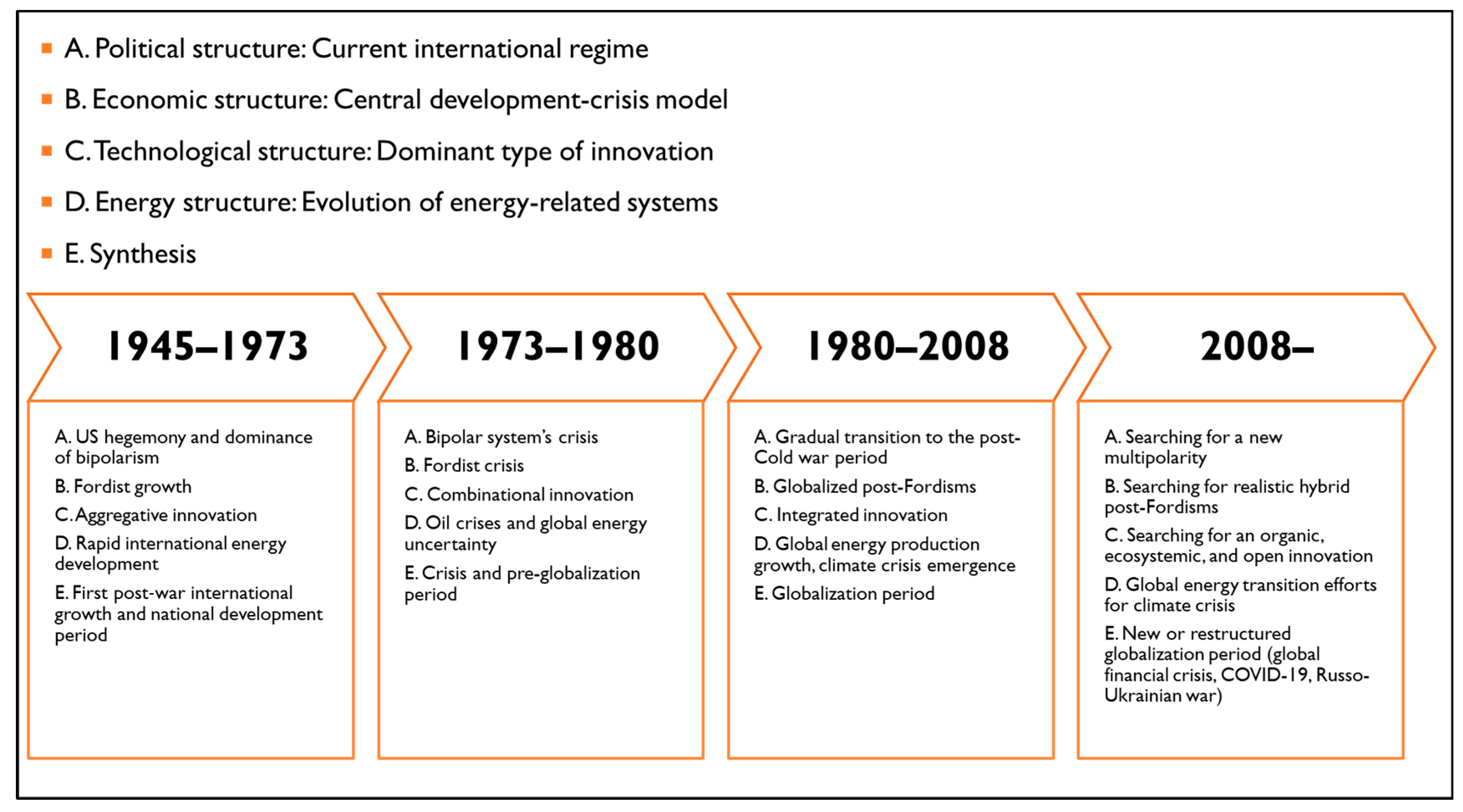

2. Background: Periodization of the Development Phases of the Global System after World War II and the Coevolution of the Global Energy System

- (I)

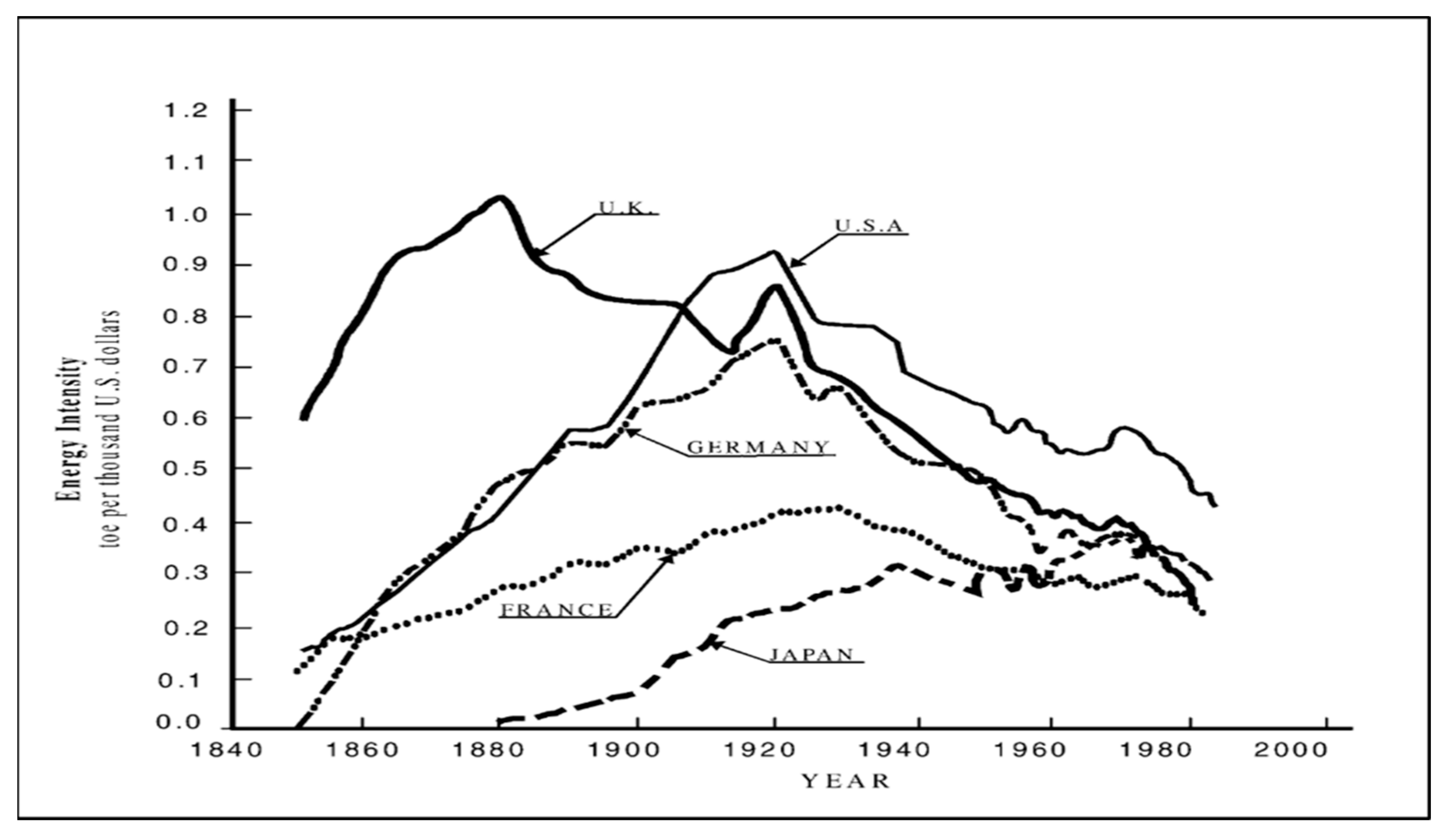

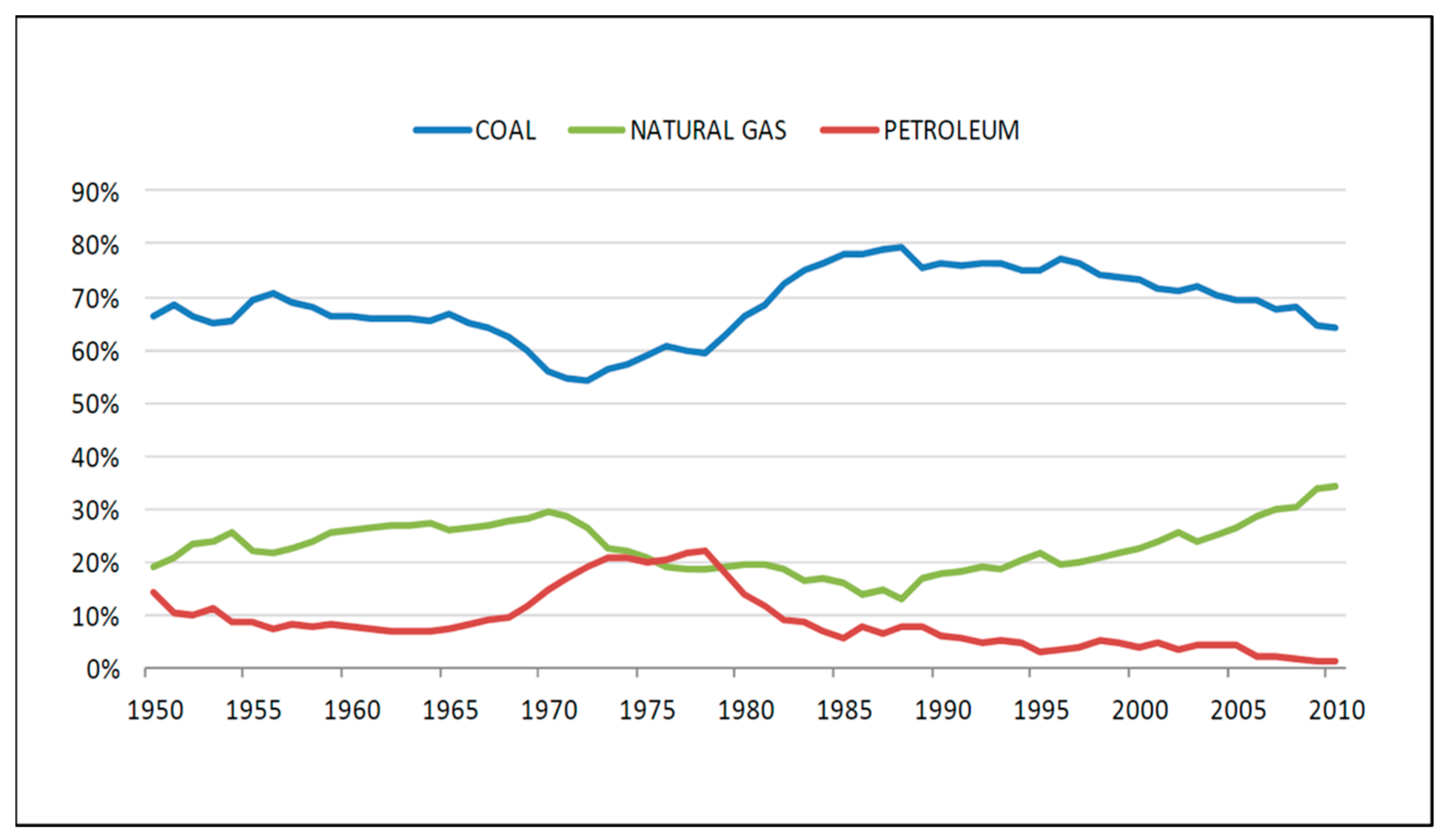

- The Era of US Hegemony (1945–1973): International politics were dominated by US hegemony, despite the presence of a strong geopolitical rival, the USSR. This established a robust bipolarity anchored in the “nuclear balance of terror” and the Cold War [11]. The growth of central economies was fueled by Fordist mass production and the increasing consumption of standardized consumer products alongside a growing welfare state supported by Keynesian-style public spending and innovation driven by economies of scale 1.

- (II)

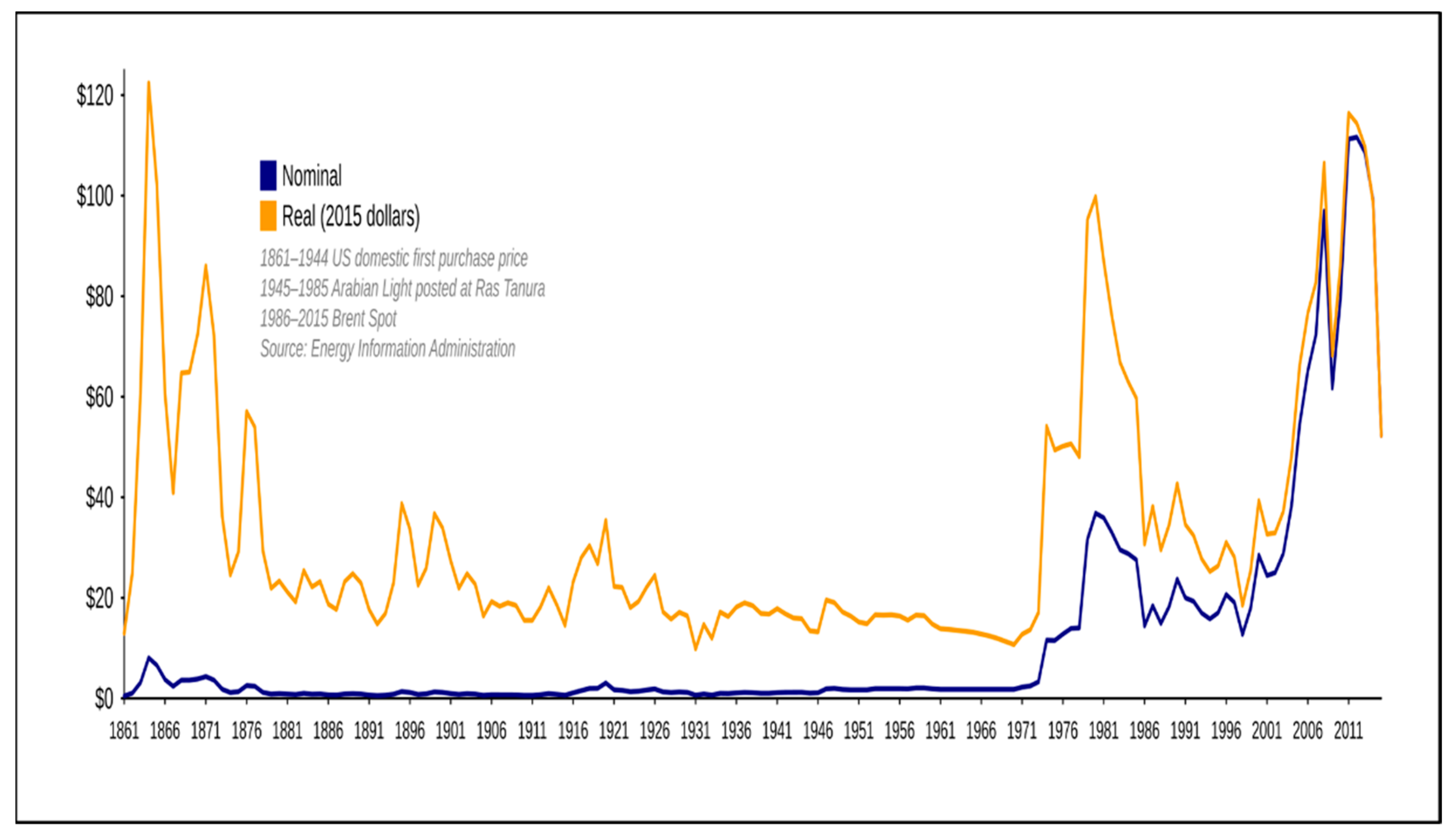

- The Phase of Crisis and Pre-globalization (1973–1980): The subsequent phase was marked by a series of crises within the bipolar system and Fordism [14], accompanied by the emergence of combinational innovation [18]. The simultaneous production and consumption crises of Fordism constituted the crisis matrix of this transitional period, as large-scale businesses increasingly targeted specific market segments through more sophisticated marketing strategies, emphasizing qualitative product differentiation and increasing their outward orientation, particularly through foreign direct investments [19].

- (III)

- The Phase of Globalization (1980–2008): This phase saw a gradual shift to a post-Cold War era and globalized post-Fordism. This period was marked by the dissolution of the USSR and the rise of the BRICS countries as major new political-economic poles [25]. Combined and rapid structural changes at international political, economic, and technological levels drastically reshaped existing global balances, shifting the center of gravity of socioeconomic architecture globally. These changes created the backdrop for a period of remarkably rapid growth in most parts of the world, with many less developed countries experiencing significant improvements in living standards for the first time [26].

- (IV)

- The Restructured Globalization Phase (2008–Present): This phase began in 2008, initiated by the global financial crisis—although structurally incubated earlier [30]—and continues to the present day [30,31]. This period is defined by a search for new multipolarity and realistic hybrid post-Fordisms, with a growing emphasis on organic, ecosystemic, and open innovation [32]. These trends indicate a need for substantial restructuring in the global socioeconomic system [6,33]. Many developments today indicate a clear reversal of globalization as it was previously known [34].

3. Methods

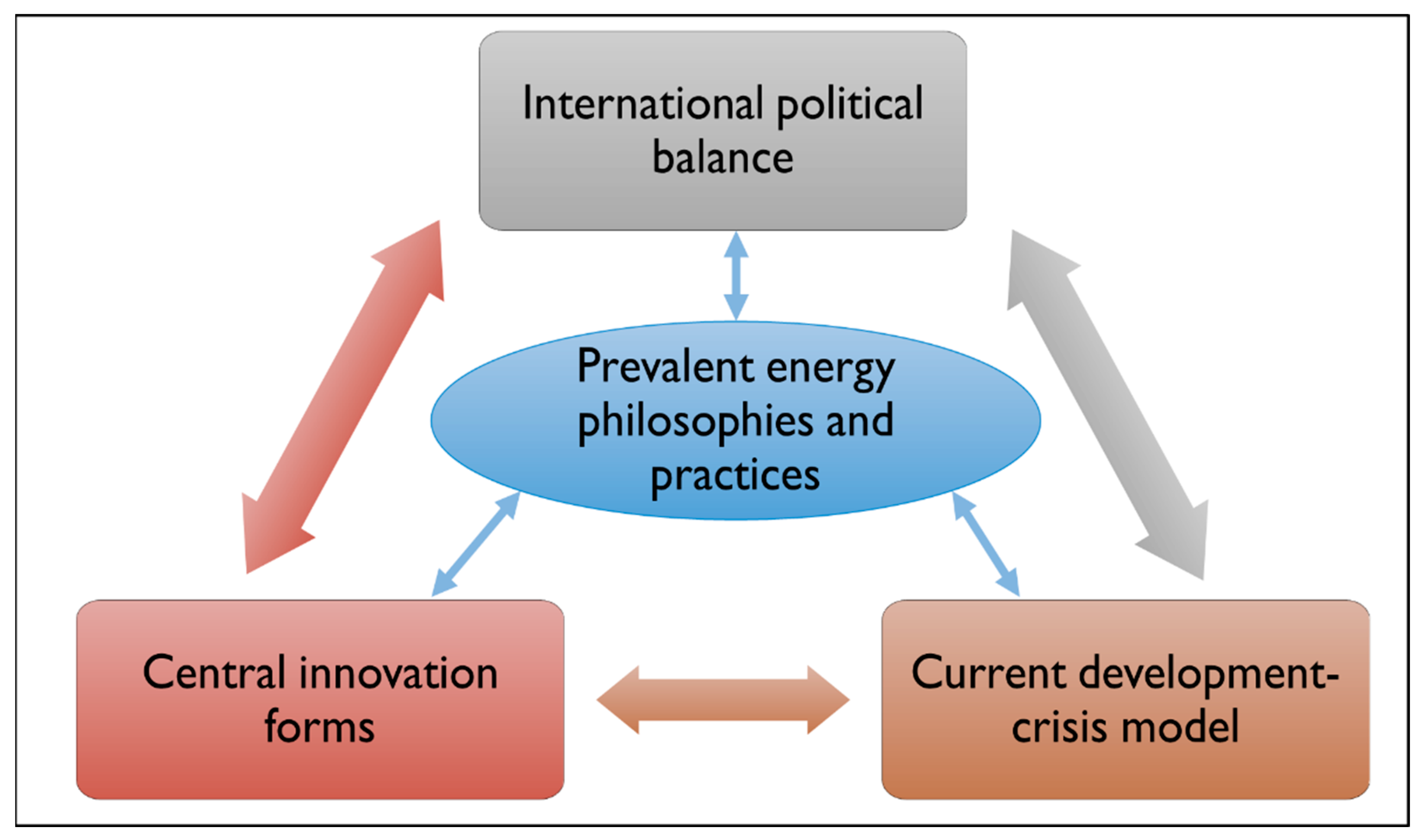

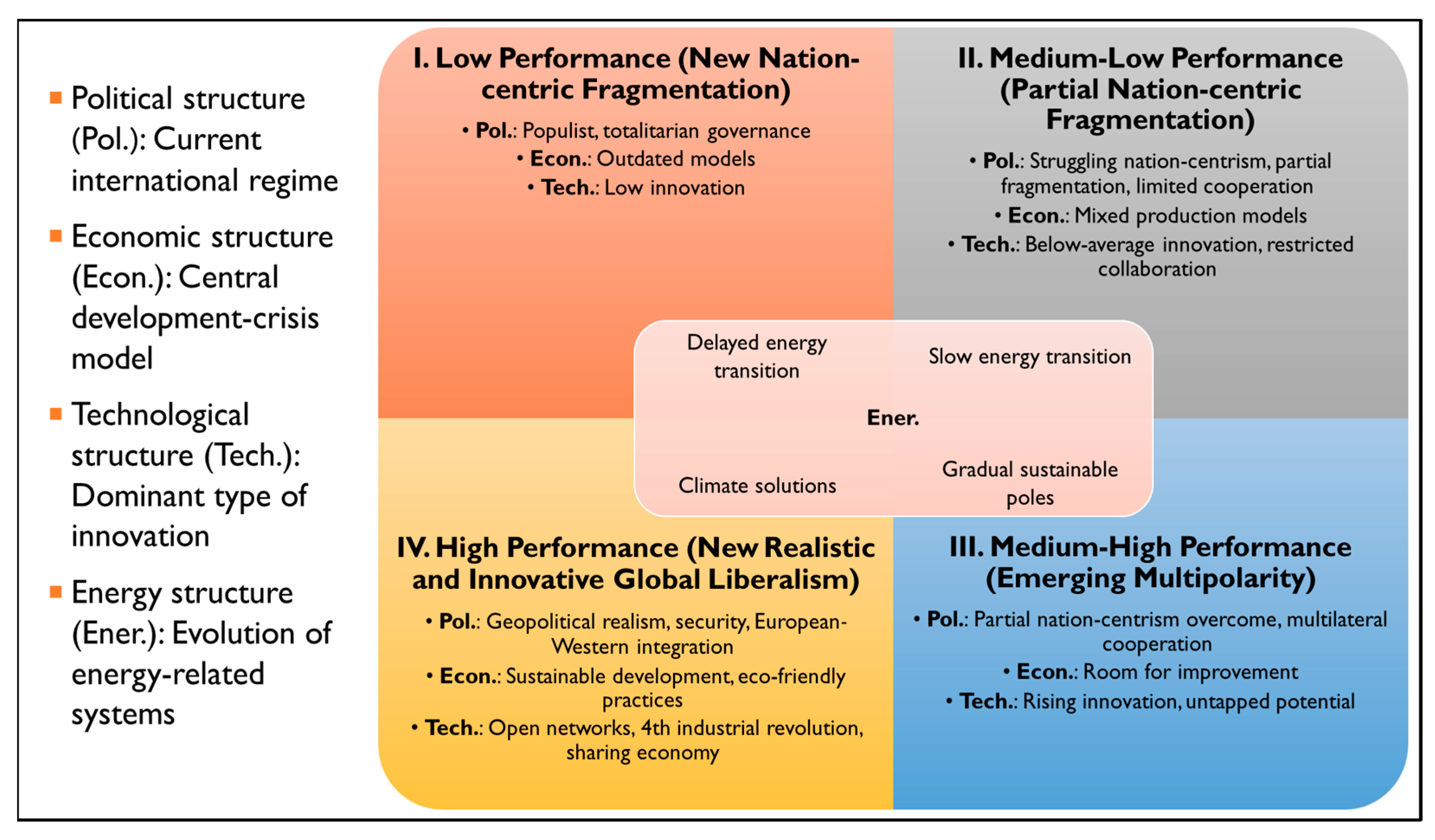

3.1. The Framework of the New Globalization Scenario Matrix (NGSM) and the Energy Sector

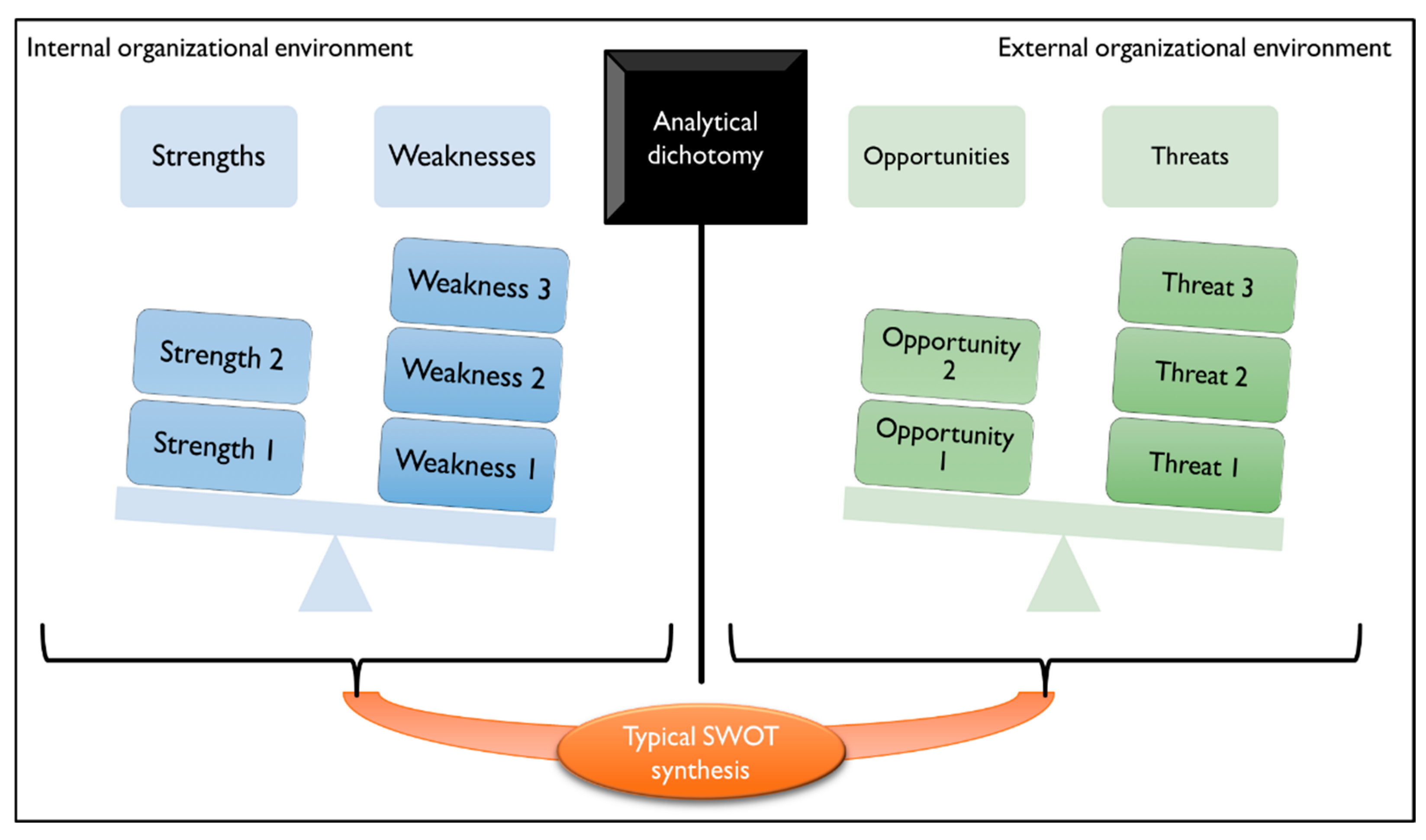

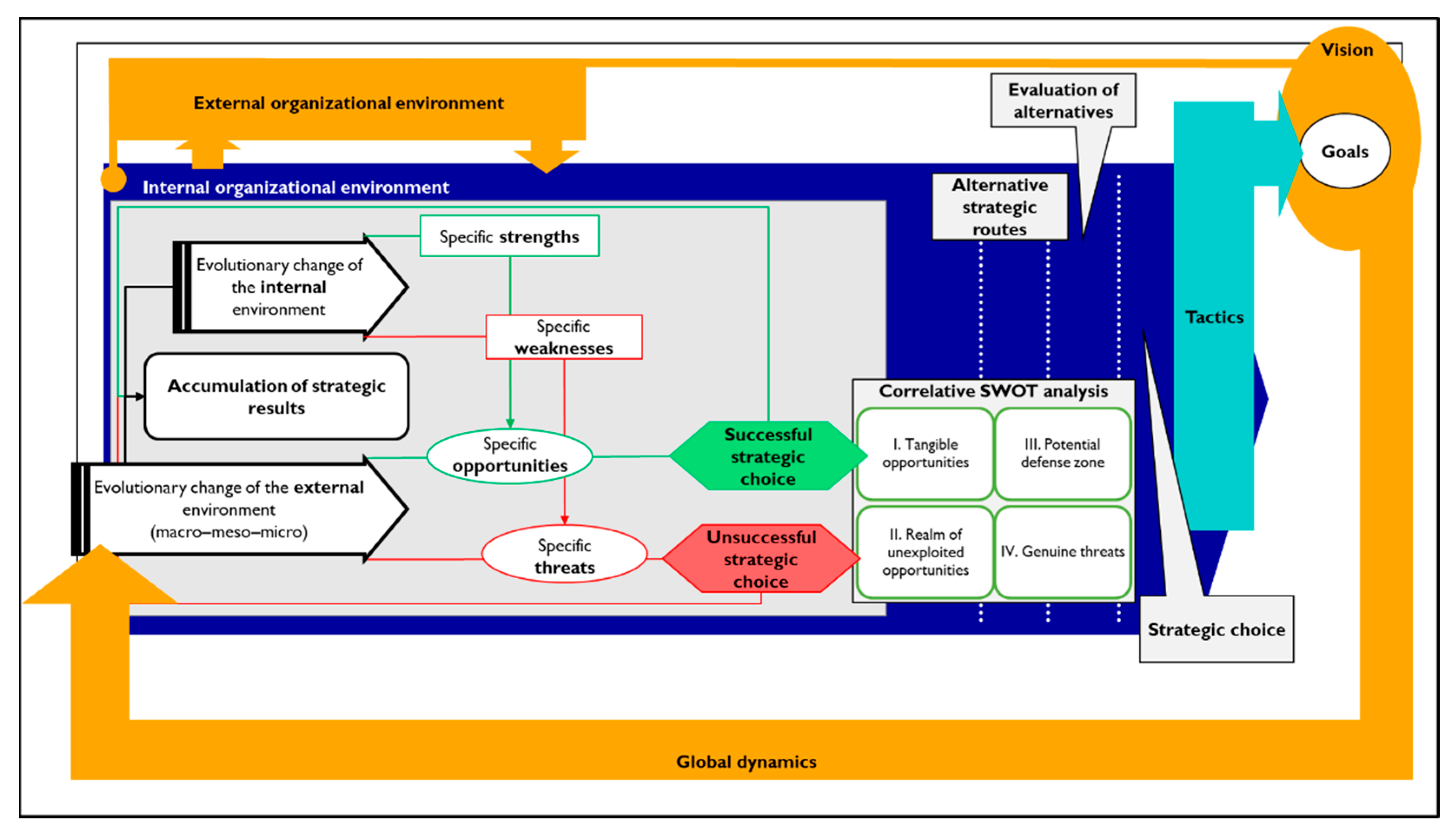

3.2. The Correlative SWOT Analysis in Geoeconomics and Modern Geopolitics

4. Results

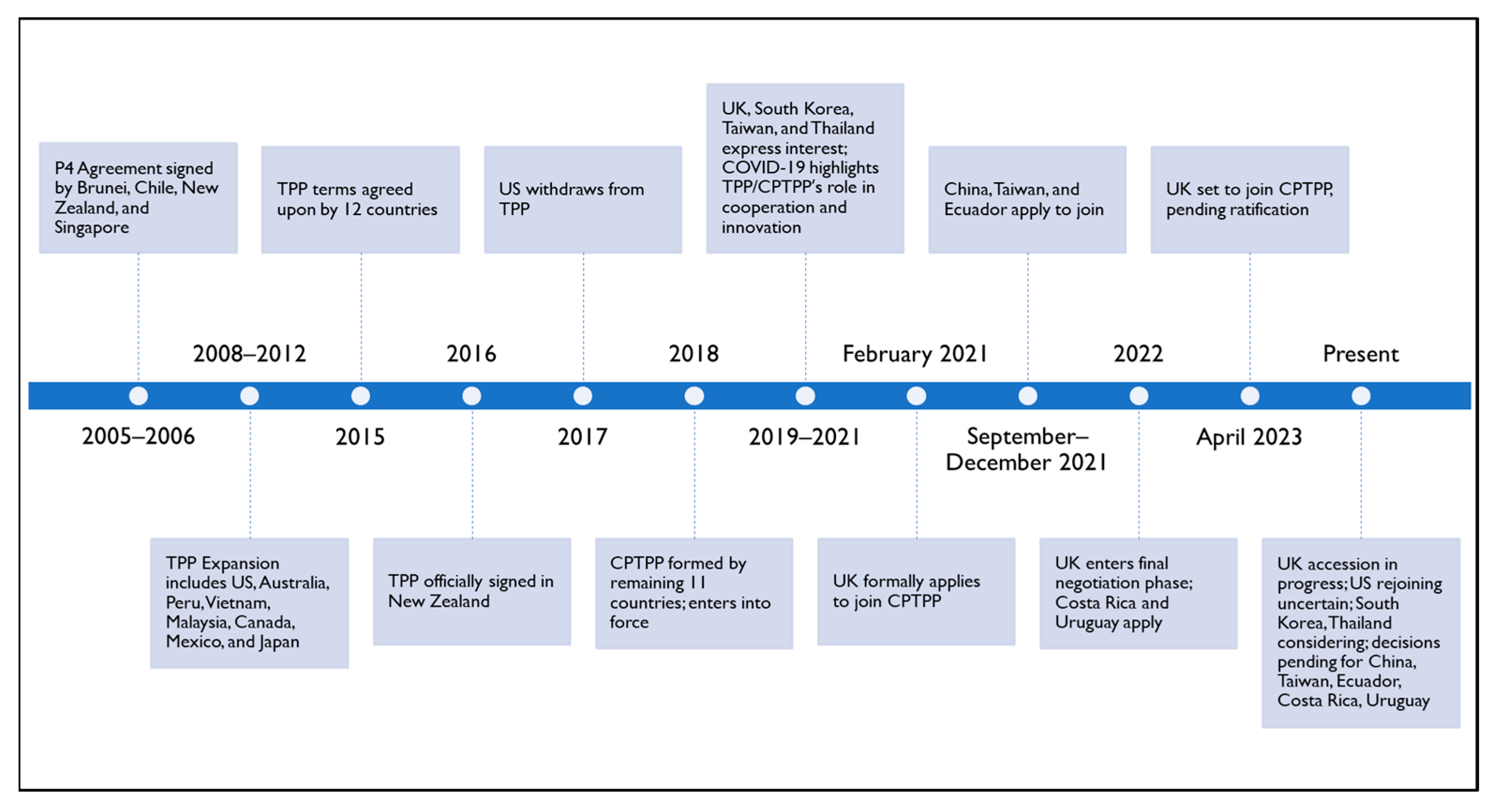

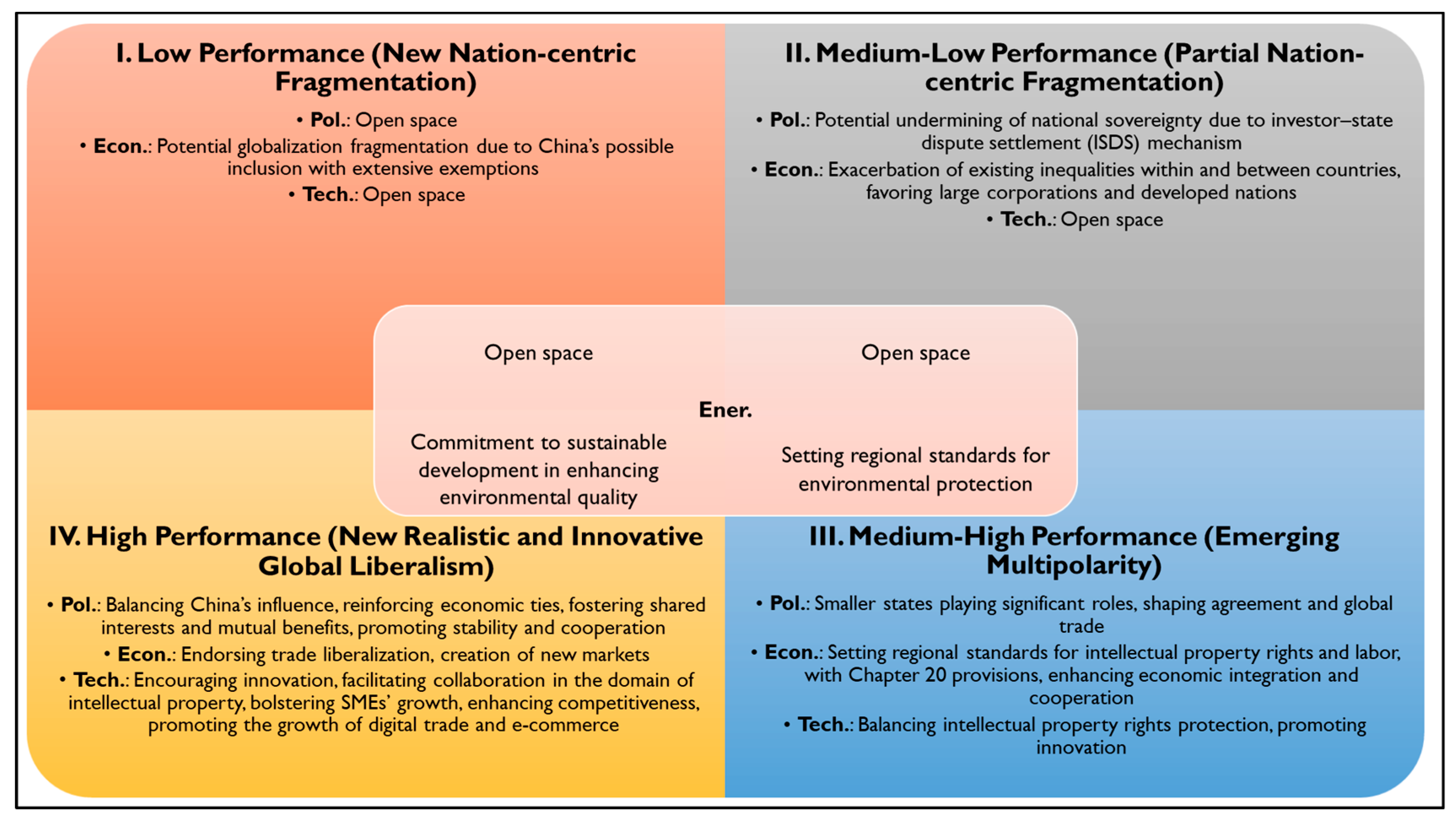

4.1. TPP/CPTPP Agreements

- Tangible opportunities: strengthening economic interdependence; promoting a rule-based global order; balancing economic growth with environmental conservation; facilitating the growth of digital trade.

- Realm of unexploited opportunities: limitation due to incomplete inclusion; power asymmetry affecting smaller states; risks of overemphasis on trade liberalization.

- Potential defense zone: regulatory influence on labor and environment; intellectual property rights; incentivization of domestic economic reforms; balanced protection of intellectual property rights.

- Genuine threats: potential fragmentation of globalization; risk of dilution of standards; adverse impacts of overemphasized market liberalization.

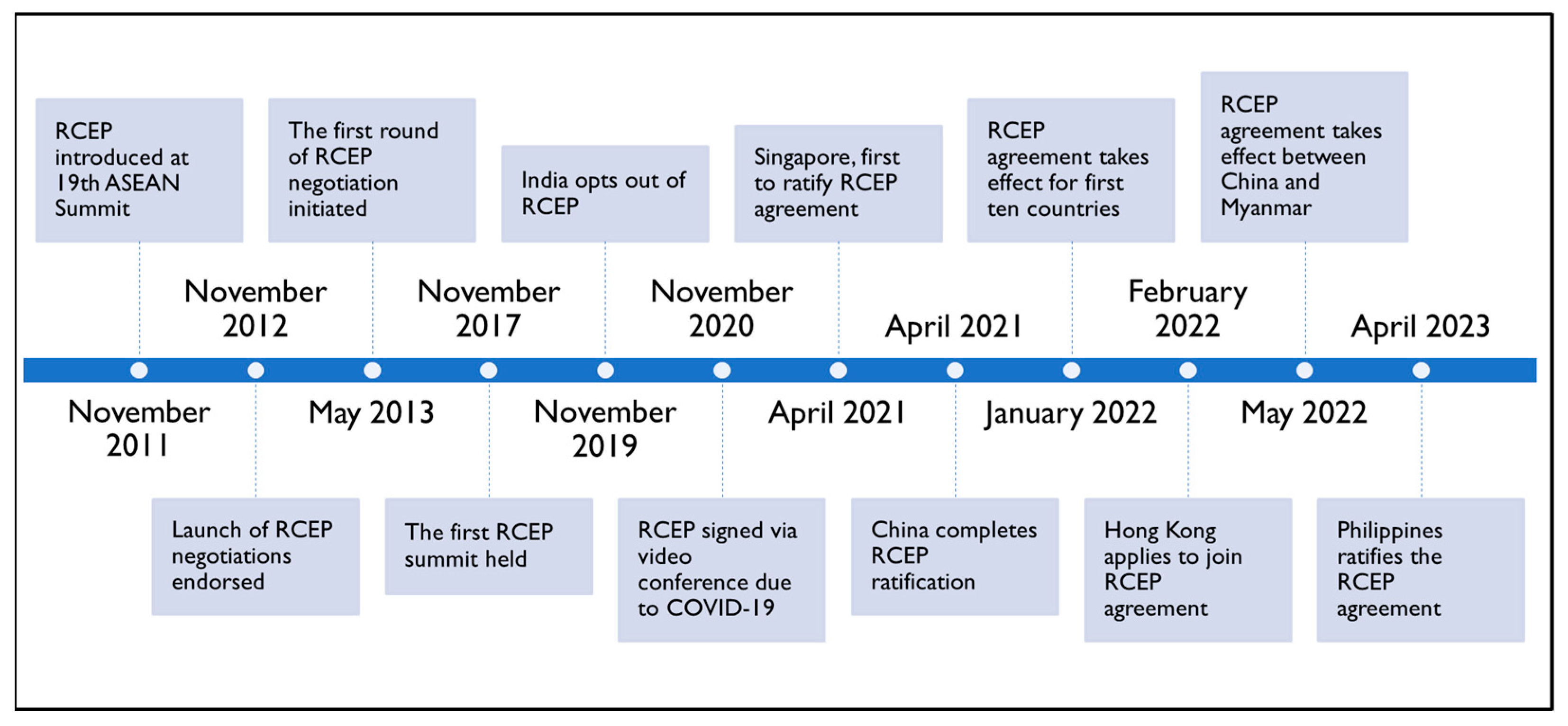

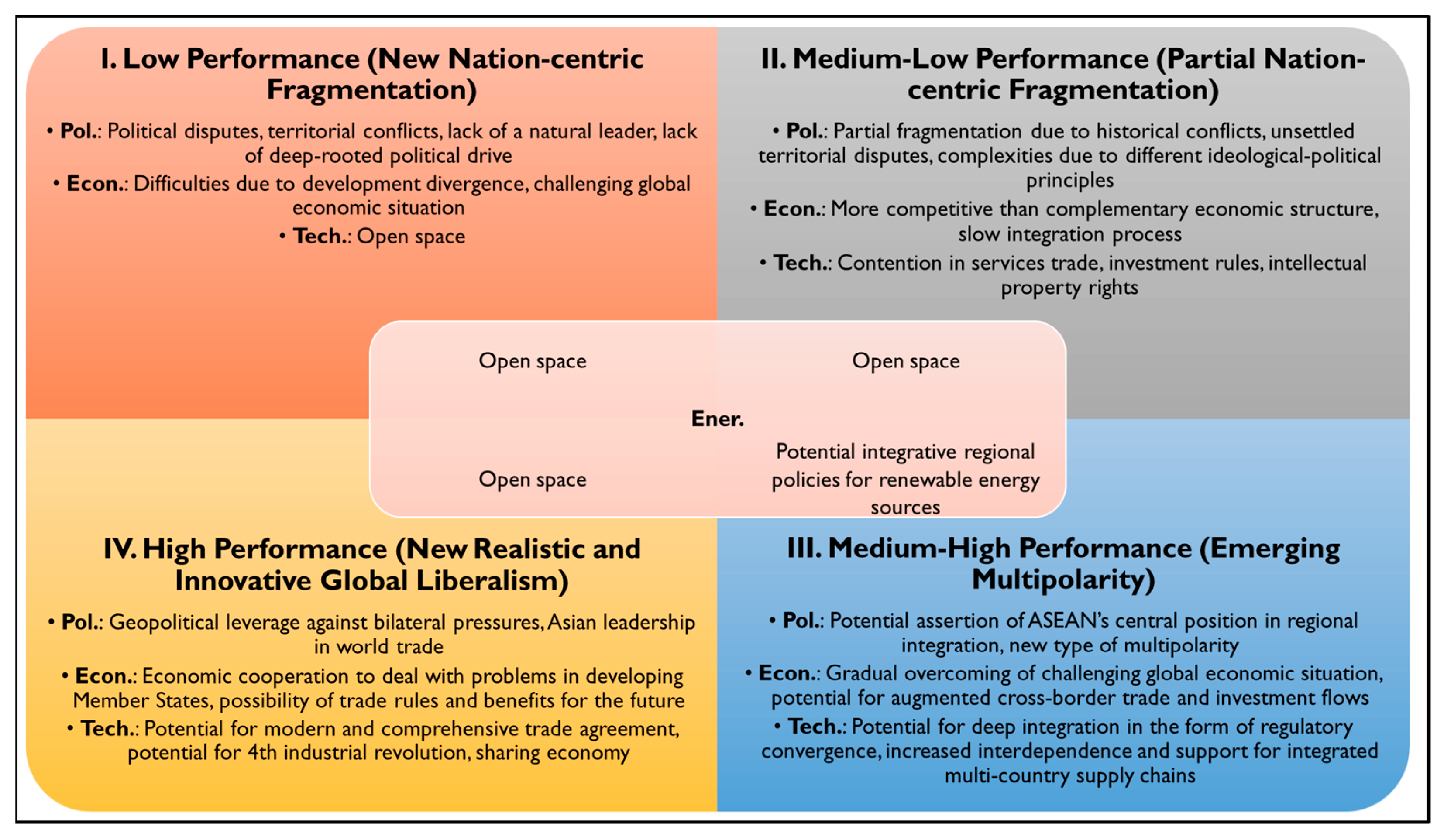

4.2. RCEP Agreement

- Tangible opportunities: leveraging inclusive East Asia economic model; step-by-step comprehensive trade agreement approach; geopolitical advantage against bilateral pressures; established bilateral agreements and deepening trade links.

- Realm of unexploited opportunities: historical conflicts and ideological divergences; lack of single economic leadership; contentious negotiations in service trade, investment rules, and intellectual property rights; competitive rather than complementary economic structures.

- Potential defense zone: ASEAN-led consolidation of smaller FTAs; alignment with WTO rules against global protectionism; ASEAN-led deep integration and regulatory convergence; fostering market-driven economic integration to offset US–China barriers.

- Genuine threats: diplomatic relations and sovereignty disputes; massive economic and developmental disparity among members; potential mimicry of less attractive ASEAN FTAs; erosion of WTO’s central role due to mega-regional FTAs.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Fordism, emerging as a dominant development model during the “thirty glorious years”, refers to Henry Ford’s mass production techniques and high wages, enabling mass consumption. Initially developed in the pre-WWII USA, it spread after WWII throughout the Western world, marking a new era of prosperity and consumer capabilities for the working class. This model, according to the regulation school’s perspective [14], is characterized by the coevolving forces of mass production and consumption, balanced by the Keynesian welfare state and counter-cyclical policies, thereby shaping national and international regulatory systems [15,16]. |

| 2 | The data utilized inherently possess a cumulative nature, which tends to homogenize a reality that, in its various facets, remains heterogeneous. This heterogeneity results in distinct situations and trends within the individual socio-economic systems that influence globalization during the specific period under study. |

| 3 | Rising prices and the reduced availability of natural gas are leading countries to explore other routes, such as increased coal-fired energy production and liquefied natural gas (LNG). The US has strengthened its position as a major LNG exporter, redirecting its exports to meet Europe’s needs. While LNG is a viable alternative, it remains more expensive than dry gas supplied by pipelines [41]. Nuclear energy is also being reconsidered as a viable energy source, with countries such as Germany, France, and the UK either postponing the closure of nuclear plants or investing in new nuclear stations. Innovations such as small modular reactors offer a safer and more cost-effective solution, despite the challenges of waste disposal [38]. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | In this article, we propose a methodological expansion by conceptualizing the global system as an “organism” at the highest level of complexity, similar to recent analyses [62,63]. This perspective requires defining the mechanism that directs this global system. Specifically, it involves clarifying the current global governance framework, which today comprises a diverse array of international state and non-state decision-making and action bodies [67]. As we seek a new phase of globalization, this framework is undergoing a process of re-evaluation and is searching for a new architectural foundation. |

| 6 | As previously mentioned, this study aims to explore how and to what extent these two global events influence the development of various scenarios. If there appears to be a lack of clear trends in the scenarios studied and the different aspects of NGSM-based agreements, this suggests an area of uncertainty regarding the final shape and progression of this global event. Simply put, as this event continues to unfold, a clearer trend may emerge over time. This uncertainty represents an “open space” because the process is ongoing, and definitive conclusions cannot yet be drawn. This indicates that the event is still developing and, under certain conditions, will eventually become clearer. These open spaces could present opportunities for potential improvement that enable better exploitation of the existing strengths of the agreements while addressing their weaknesses. However, these same open spaces could lead to negative outcomes in the future if the agreements’ weaknesses are exacerbated or their strengths are reduced. |

References

- Belyi, A.V. Energy in International Political Economy. In Transnational Gas Markets and Euro-Russian Energy Relations; Belyi, A.V., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2015; pp. 9–39. ISBN 978-1-137-48298-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzemko, C.; Lawrence, A.; Watson, M. New Directions in the International Political Economy of Energy. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2019, 26, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P. Trasformismo or Transformation? The Global Political Economy of Energy Transitions. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2019, 26, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Graaf, T.; Sovacool, B.K.; Ghosh, A.; Kern, F.; Klare, M.T. States, Markets, and Institutions: Integrating International Political Economy and Global Energy Politics. In The Palgrave Handbook of the International Political Economy of Energy; Van de Graaf, T., Sovacool, B.K., Ghosh, A., Kern, F., Klare, M.T., Eds.; Palgrave Handbooks in IPE; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2016; pp. 3–44. ISBN 978-1-137-55631-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, T. The Energy System: Technology, Economics, Markets and Policy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-0-262-03752-5. [Google Scholar]

- Vlados, C. The Phases of the Postwar Evolution of Capitalism: The Transition from the Current Crisis into a New Worldwide Developmental Trajectory. Perspect. Glob. Dev. Technol. 2019, 18, 457–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, D. Japan’s Policy on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in Light of IR Theory and Analytical Eclecticism. J. Int. Glob. Stud. 2019, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís, M. China Moves to Join the CPTPP, but Don’t Expect a Fast Pass; Brookings: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, F. “RCEP from the Middle Powers’ Perspective”. China Econ. J. 2021, 14, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlados, C.; Chatzinikolaou, D.; Iqbal, B.A. New Globalization and Multipolarity: A Critical Review and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Case. J. Econ. Integr. 2022, 37, 458–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, V.; Sagan, S.D. (Eds.) The Fragile Balance of Terror: Deterrence in the New Nuclear Age; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-5017-6701-2. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Today in Energy; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Cleveland, C.J. Energy Transitions: A Historical Perspective; Ramapo College of New Jersey: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, R.; Durand, J.-P. L’après-Fordisme; Série Poche; Syros: Paris, France, 1993; ISBN 978-2-86738-884-2. [Google Scholar]

- Edgell, S.; Gottfried, H.; Granter, E. The SAGE Handbook of the Sociology of Work and Employment; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4462-8066-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P.A. The Political Power of Economic Ideas: Keynesianism across Nations; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-0-691-07799-4. [Google Scholar]

- Goldemberg, J. Leapfrog Energy Technologies. Energy Policy 1998, 26, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, R. Towards the Fifth-generation Innovation Process. Int. Mark. Rev. 1994, 11, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.A.; Soskice, D.W. (Eds.) Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-19-924775-2. [Google Scholar]

- Michalet, C.A. La Seduction des Nations ou Comment Attirer les Investissements [Seduction of Nations or How to Attract Investments]; Economica: Paris, France, 1999; ISBN 978-2-7178-3924-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl, D.M. The Arab Oil Embargo and Its Impact on Winter Fuel Shortages; Environmental Policy Division 73-189 EP; Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bini, E.; Garavini, G.; Romero, F. (Eds.) Oil Shock: The 1973 Crisis and Its Economic Legacy; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-78453-556-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, A.S. Showdown at Doha: The Secret Oil Deal That Helped Sink the Shah of Iran. Middle East J. 2008, 62, 567–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- File: Oil Prices Since 1861. Svg-Wikipedia. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oil_Prices_Since_1861.svg (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Duggan, N. BRICS and the Evolution of a New Agenda within Global Governance. In The European Union and the BRICS: Complex Relations in the Era of Global Governance; Rewizorski, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Held, D.; McGrew, A.; Goldblatt, D.; Perraton, J. Global Transformations: Politics, Economics and Culture. In Politics at the Edge; Pierson, C., Tormey, S., Eds.; Macmillan: London, UK, 2000; pp. 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Holdren, J.P. The Energy Innovation Imperative: Addressing Oil Dependence, Climate Change, and Other 21st Century Energy Challenges. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2006, 1, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, A.O.; Opoku, E.E.O.; Dogah, K.E. The Political Economy of Energy Transition: The Role of Globalization and Governance in the Adoption of Clean Cooking Fuels and Technologies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 186, 122156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Fuel Competition in Power Generation and Elasticities of Substitution; Independent Statistics & Analysis; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Vlados, C.; Deniozos, N.; Chatzinikolaou, D.; Demertzis, M. Towards an Evolutionary Understanding of the Current Global Socio-Economic Crisis and Restructuring: From a Conjunctural to a Structural and Evolutionary Perspective. Res. World Econ. 2018, 9, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Andrikopoulos, A.; Nastopoulos, C. Κρίση Και Ρεαλισμός [Crisis and Realism]; Propobos Publications: Athens, Greece, 2015; ISBN 978-618-5036-16-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bogers, M.; Chesbrough, H.; Heaton, S.; Teece, D.J. Strategic Management of Open Innovation: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2019, 62, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzinikolaou, D.; Vlados, C. Unravelling the New Globalization: An Evolutionary Structural Analysis of Postwar World Capitalism and Policy Implications; EAEPE: Leeds, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, S.A. Will Covid-19 Have a Lasting Impact on Globalization? Harvard Business Review. 2020. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/05/will-covid-19-have-a-lasting-impact-on-globalization (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Selmi, R.; Bouoiyour, J. From COVID-19 to “Political Virus”: Implications for Business. In Proceedings of the Disrupting Thinking Event, TU Dublin, Dublin, Ireland, 14 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Benabess, N. The Evolution of Geoeconomics and the Need for New Theories of Governance. In Advances in Geoeconomics; Munoz, J.M., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 209–216. ISBN 1-315-31213-1. [Google Scholar]

- Czifra, G.; Molnár, Z. COVID-19 and Industry 4.0. Res. Pap. Fac. Mater. Sci. Technol. Slovak Univ. Technol. 2020, 28, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollfrass, A.K.; Herzog, S. The War in Ukraine and Global Nuclear Order. Survival 2022, 64, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grekou, C.; Hache, E.; Lantz, F.; Massol, O.; Mignon, V.; Ragot, L. La Dépendance de l’Europe Au Gaz Russe: État Des Lieux et Perspectives [Europe’s Dependence on Russian Gas: State of Play and Prospects]. Rev. Déconomie Financ. 2022, 147, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleva, P.; Marinova, T. Financer La Transition Énergétique En Europe Centrale et Orientale: Un Levier Pour Surmonter La Dépendance de Sentier à l’égard de La Russie? [Financing the Energy Transition in Central and Eastern Europe: A Catalyst for Overcoming Path Dependence on Russia?]. Rev. Déconomie Financ. 2022, 147, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faudot, A.; Rossiaud, S. Le Régime Rentier En Russie et Son Évolution Après La Guerre En Ukraine. Rev. Déconomie Financ. [CrossRef]

- Herman, L.; Ariel, J. Comparative Energy Regionalism: North America and the European Energy Community. Rev. Policy Res. 2024, 41, 382–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quitzow, R.; Nunez, A.; Marian, A. Positioning Germany in an International Hydrogen Economy: A Policy Review. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 53, 101361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menu, D. L’Asie Centrale Sous le Coup de la Guerre En Ukraine: Conséquences et Perspectives. Rev. Déconomie Financ. 2022, 3, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Wind Energy Council. Global Wind Statistics 2015; Global Wind Energy Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Liu, B.; Tawiah, V.; Zakari, A. Greening African Economy: The Role of Chinese Investment and Trade. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laimon, M.; Yusaf, T.; Mai, T.; Goh, S.; Alrefae, W. A Systems Thinking Approach to Address Sustainability Challenges to the Energy Sector. Int. J. Thermofluids 2022, 15, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heurtebise, J.-Y. Philosophy of Energy and Energy Transition in the Age of the Petro-Anthropocene. J. World Energy Law Bus 2020, 13, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmer, M.F.; Easton, S.; Eisenhut, M.; Epstein, E.; Kromoser, R.; Peterson, E.R.; Rizzon, E. Introduction. In Disruptive Procurement: Winning in a Digital World; Strohmer, M.F., Easton, S., Eisenhut, M., Epstein, E., Kromoser, R., Peterson, E.R., Rizzon, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-3-030-38950-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell, A.; Møller, J.; Skaaning, S.-E. Democratic Stability in an Age of Crisis: Reassessing the Interwar Period; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-19-189906-5. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution; Crown Business: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-5247-5886-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. New Regionalism Reshaping the Future of Globalization. China Q. Int. Strat. Stud. 2020, 6, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, S.T. Disrupting Globalization: Prospects for States and Firms in International Business. In COVID-19 and International Business; Marinov, M.A., Marinova, S.T., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 365–377. ISBN 1-00-310892-X. [Google Scholar]

- Luttwak, E.N. From Geopolitics to Geo-Economics: Logic of Conflict, Grammar of Commerce. Natl. Interest 1990, 20, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lorot, P. Introduction à la Géoéconomie [Introduction to Geoeconomics]; Institut Européen de Géoéconomie: Paris, France, 1999; ISBN 978-2-7178-3962-3. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, R. Seize the Moment: America’s Challenge in a One-Superpower World, 2012 edition; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA; London, UK; Toronto, ON, Canada; Sydney, Australia; New Delhi, India, 1992; ISBN 978-1-4767-3186-5. [Google Scholar]

- Søilen, K.S. Geoeconomics; Ventus Publishing ApS/Bookboon: London, UK; Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Søilen, K.S. Why the Social Sciences Should Be Based in Evolutionary Theory: The Example of Geoeconomics and Intelligence Studies. J. Intell. Stud. Bus. 2017, 7, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søilen, K.S. The Shift from Geopolitics to Geoeconomics and the Failure of Our Modern Social Sciences; The Telos Institute: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vlados, C.; Deniozos, N.; Chatzinikolaou, D. Dialectical Prerequisites on Geopolitics and Geo-Economics in Globalization’s Restructuration Era. J. Econ. Soc. Thought 2019, 6, 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Vlados, C. On a Correlative and Evolutionary SWOT Analysis. J. Strategy Manag. 2019, 12, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlados, C. On Evolutionary Geoeconomics and the RCEP Case: A Correlative SWOT Analysis. China WTO Rev. 2023, 9, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzinikolaou, D.; Kapaltzoglou, F.; Vlados, C. The Evolutionary and Correlative SWOT Analysis in Geoeconomics: Examining the RCEP within Today’s Global Political Economy; EAEPE: Leeds, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, T.; Westbrook, R. SWOT Analysis: It’s Time for a Product Recall. Long Range Plan. 1997, 30, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, J.; Helms, M.M. Exploring SWOT Analysis—Where Are We Now?: A Review of Academic Research from the Last Decade. J. Strategy Mgt 2010, 3, 215–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotou, G. Bringing SWOT into Focus. Bus. Strategy Rev. 2003, 14, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, C.B. The Origins of Informality: Why the Legal Foundations of Global Governance Are Shifting, and Why It Matters; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-19-094796-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, M. The TPP and CPTPP: Truths about Power Politics. In The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership: Implications for Southeast Asia; Lee, C., Bhattacharya, P., Eds.; ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute: Singapore, 2021; pp. 30–50. ISBN 978-981-4818-88-9. [Google Scholar]

- Draper, P.; McDonagh, N. The Missing Anchor: Why the EU Should Join the CPTPP; Lowy Institute Policy Brief; Lowy Institute: Sydney, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oba, M. Further Development of Asian Regionalism: Institutional Hedging in an Uncertain Era. J. Contemp. East Asia Stud. 2019, 8, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, H. Is the Liberal International Order Dead? Global Value Chains and the CPTPP; UBC: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Biegon, R. US Hegemony and the Trans-Pacific Partnership: Consensus, Crisis, and Common Sense. Chin. J. Int. Politics 2020, 13, 69–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Huang, J.J. What Should China Learn from the CPTPP Environmental Provisions? Asian J. WTO Int. Health Law Policy 2018, 13, 511–550. [Google Scholar]

- Meidinger, E. C8TPP and Environmental Regulation. In Megaregulation Contested: Global Economic Ordering After TPP; Kingsbury, B., Malone, D.M., Mertenskötter, P., Stewart, R.B., Streinz, T., Sunami, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 175–195. ISBN 978-0-19-882529-6. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Á. C7The Lessons of TPP and the Future of Labor Chapters in Trade Agreements. In Megaregulation Contested: Global Economic Ordering After TPP; Kingsbury, B., Malone, D.M., Mertenskötter, P., Stewart, R.B., Streinz, T., Sunami, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 140–174. ISBN 978-0-19-882529-6. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, D.H.; Tran, Q.; Tran, T. Economic Growth, Renewable Energy and Financial Development in the CPTPP Countries. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, I. E-Commerce in Free Trade Agreements and the Trans-Pacific Partnership. In Developing the Digital Economy in ASEAN; Chen, L., Kimura, F., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 91–108. ISBN 978-0-429-50485-3. [Google Scholar]

- Nath Upreti, P. From TPP to CPTPP: Why Intellectual Property Matters. J. Intellect. Prop. Law Pract. 2018, 13, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, C.M. Paths Ahead for East Asia and Asia-Pacific Regionalism. Int. Aff. 2013, 89, 963–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, P.A.; Plummer, M.G.; Urata, S.; Zhai, F. Going It Alone in the Asia-Pacific: Regional Trade Agreements without the United States; Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper; Peterson Institute for International Economics: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, D.; Chaisse, J.; Qian, X. Is It Finally Time for India’s Free Trade Agreements? The ASEAN “Present” and the RCEP “Future”. Asian J. Int. Law 2019, 9, 359–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.S. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership: New Paradigm or Old Wine in a New Bottle? Asian-Pac. Econ. Lit. 2015, 29, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wignaraja, G. What Does RCEP Mean for Insiders and Outsiders? The Experience of India and Sri Lanka; ARTNeT Working Paper Series; ARTNeT: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cadot, O.; Ing, L.Y. Non-Tariff Measures and Harmonisation: Issues for the RCEP; ERIA: Tokyo, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Petri, P.A.; Plummer, M.G. East Asia Decouples from the United States: Trade War, COVID-19, and East Asia’s New Trade Blocs; Peterson Institute for International Economics: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gnyawali, D.R.; Park, B.-J. (Robert) Co-Opetition between Giants: Collaboration with Competitors for Technological Innovation. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaro, V.F. Universal Co-Opetition: Nature’s Fusion of Cooperation and Competition... and How It Can Save Our Finances, Our Families, Our Future and Our World; Betty Youngs Book Publishers: Gardena, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-936332-08-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzemko, C.; Keating, M.F.; Goldthau, A. Nexus-Thinking in International Political Economy: What Energy and Natural Resource Scholarship Can Offer International Political Economy. In Handbook of the International Political Economy of Energy and Natural Resources; Goldthau, A., Keating, M.F., Kuzemko, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-1-78347-563-6. [Google Scholar]

- Koutroukis, T.; Chatzinikolaou, D.; Vlados, C.; Pistikou, V. The Post-COVID-19 Era, Fourth Industrial Revolution, and New Globalization: Restructured Labor Relations and Organizational Adaptation. Societies 2022, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Molina, L. COVID-19 on Route of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlados, C.; Chatzinikolaou, D. Mutations of the Emerging New Globalization in the Post-COVID-19 Era: Beyond Rodrik’s Trilemma. Territ. Politics Gov. 2022, 10, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losee, J. A Historical Introduction to the Philosophy of Science, 2001 edition; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chatzinikolaou, D.; Vlados, C.M. New Globalization and Energy Transition: Insights from Recent Global Developments. Societies 2024, 14, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14090166

Chatzinikolaou D, Vlados CM. New Globalization and Energy Transition: Insights from Recent Global Developments. Societies. 2024; 14(9):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14090166

Chicago/Turabian StyleChatzinikolaou, Dimos, and Charis Michael Vlados. 2024. "New Globalization and Energy Transition: Insights from Recent Global Developments" Societies 14, no. 9: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14090166

APA StyleChatzinikolaou, D., & Vlados, C. M. (2024). New Globalization and Energy Transition: Insights from Recent Global Developments. Societies, 14(9), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14090166