Abstract

Globally, youth satisfaction with democracy is declining—not only in absolute terms, but also relative to how older generations felt at the same stage in their lives. Young people’s democratic political identity is lower than any other age group. One can point to concrete factors to explain such declines—ranging from the growth of youth unemployment to the persistence of corruption and poverty in new democracies. Growing discontent with living conditions is taken advantage of by populist leaders. This populist rule—whether from the right or the left—has a highly negative effect on democratic political identities (especially on youth) and can lead to a significant risk of democratic erosion. Our research aims to explore the significance of youth identification with democracy, and their participation approaches as an alternative to the decline in democratic quality in Barcelona, Spain. Using quantitative data collection and analysis, in this article we present the first results of our research and suggest a path for further investigation.

1. Introduction

Democracy and youth are challenging issues for contemporary political sciences, since youth democratic disaffection is increasing everywhere. Young people’s democratic political identity is lower than any other age group. By their mid-thirties, 55% of global millennials say they are dissatisfied with democracy [1].

One can point to concrete factors to explain such declines—ranging from the growth of youth unemployment to the persistence of corruption and poverty in new democracies [1] and the construction of new identities [2]. But a close literature review on the subject shows that young people’s participation patterns and behavior give evidence of an alternative and more hopeful approach, as shown in teenage support for the Black Lives Matter movement or Fridays for Future, a youth-led and -organized global climate strike movement.

Considering this approach, our research aims to contribute to the issue of young people’s democratic disaffection and the quality of their democratic participation, focusing on examples of young people who participate in civil community-based youth-led organizations in Barcelona, Spain. In this article, we present the preliminary results that provide evidence for the significance of youth identification with democratic values and their alternative democratic approaches through civil organization.

1.1. The Decline of Democracy, the Rise of Populism, and the Youth Today

The decline of youth satisfaction with democracy is not a phenomenon particular to youth, as adults also show low levels of engagement. Young people, however, seem to be particularly disengaged from the democratic institutional framework, leaving them at best apathetic or at worst alienated [3]. This leads us to our first research question: does this disaffection really correspond to a lack of identification with democratic values, or does it indicate a strong criticism of the current political atmosphere? There is ample evidence of the fact that young people are less involved in politics, with lower levels of political interest and negative political attitudes than the older population [1,4]. So much evidence exists, in fact, that we can characterize youngsters as pessimistic, disaffected citizens [5,6,7,8]. Indeed, young adults vote less today than they did in the past and are less likely to join political parties [9] but does this mean we can conclude that youth is not for democracy?

If we examine the factors that explain such attitudes—ranging from economic to political reasons—we immediately observe that youth unemployment [10] and political corruption [11] underlie this democratic disaffection [1]. We are exiting a pandemic, and we are suffering from wars in neighboring countries with a deep global impact. Satisfaction with the functioning of democratic political institutions drops in times of recession [12,13]. These issues give rise to a second research question: can this current disaffection be related to recent global crises? What is sure is that the public expression of this disaffection involves a high risk for democracy itself, as it appears to correspond to electoral support for populist parties that advocate for isolationism, the scapegoating of particular social or ethnic groups, and denouncing mainstream parties [10]. This may have a negative effect on youth democratic political identities as well, while concurrently dramatically eroding democracy [14]. Political polarization, the cultivation of a climate of animosity and the desire to dismantle democratic institutions are part of this democratic predicament [15]. This social behavior reveals a certain lack of democratic ideology among the youth, since the great appeal of these populist parties is based on their radical esthetics, simple reasoning and permanent counter-dependency [16].

1.2. New Forms of Participation and Democratic Political Identity of Youth in Public Life

The literature already provides some answers to the research questions presented above, but the idea of pessimistic, disaffected citizens should be confronted with other data that back an alternative view of the problem. The concepts of participation and politics have been undergoing a process of redefinition that gives place to more diverse ways of understanding democracy and action in the public sphere for quite some time. It is essential to make distinctions between institutionalized political participation and non-institutionalized participation [17], between conventional ways of participation (e.g., voting, joining or campaigning for a political party) and unconventional ways (e.g., protest activities and participation in new social movements) [18].

According to this argument, there is evidence that young people are disaffected with certain forms of participatory democracy, but not apathetic with the whole [5,9]. Almost nine in ten (87%) respondents of the 2021 European Parliament Youth Survey had engaged in at least one political or civic activity [19]. Almost half (46%) had voted in the last local, national or European election, and two-fifths (42%) had created or signed a petition; around a quarter had engaged in other, more direct forms of action, including boycotting or buying certain products on political, ethical or environmental grounds (25%), and taken part in street protests or demonstrations (24%) [19]. A similar proportion had engaged in online activities, including posting opinions on social media about a political or social issue (26%). In short, younger European citizens are not intrinsically distant from politics, but they prefer to experience politics in a different (i.e., non-conventional) way [20].

Some concrete examples of this are well known, both in Europe and elsewhere. We find examples of increasing youth participation in civil organizations and social movements, as shown in teenage support for the Black Lives Matter or Fridays for Future movements. Young people act through a wide variety of participatory practices and their civic and political engagement have extended to a “wider variety of channels” that may require “different listening skills among political and social analysts” [4]. Direct interactions with socializing agents can significantly influence youth involvement in politics and community projects [21], and educated but unemployed young people often show the most willingness to volunteer: young people are not disconnected from the civic life of their communities [5]. Now, however, these forms break through the aggressive action of populism (with a particular use of social networks), and, thanks to Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), the local is connected to the global.

It could be argued that the current generation of young people is not more apathetic than their predecessors but rather they create diverse repertoires of democratic political participation, and their preference is geared toward engaging in issues on a case-by-case basis rather than embedding themselves within institutions [22,23]. Given the benefits that civic engagement provides to democracy, our challenge as democratic societies is to promote a committed and participatory citizenship [17]. This would act as a barrier to the rise of populist parties, since it promotes community practices and contact activities among groups, all of which seem to be good ways to tackle the prejudices that are the basis of intolerance [24]. Civic organizations, including youth organizations, perform a number of necessary functions for promoting and safeguarding basic human rights, democracy and the rule of law. An open, civil society is one of the most important safeguards against tyranny, oppression, and other anti-democratic tendencies. A review of the literature reveals that young people are not indifferent or antithetical to democracy but against old-fashioned models that understand representative democracy in a globalized and complex world. With our research, we hope to contribute to and further understanding on this subject.

1.3. Democracy, Participation and Youth in Spain and Catalonia

Spain is not an exception to this global context. On the one hand, we observe a strong political disaffection, among Spanish citizens, and evidence shows that young people are even more critical than adults [25]. This is the end result of a long-term evolution. More than a decade prior, Frances-Garcia [26] (p. 40) found that Spanish youngsters showed “an increase in abstention from voting, a decrease in the involvement in political parties and traditional citizen organizations, a general distancing from the conventional participative activities, and a growing distrust in the performance of democratic political institutions”.

Spanish youth also behave in a manner similar to their European peers, however. In their study about university youth and political interest, Martinez-Cousinou et al. [17] found that the impact of the current health and economic crises increased a sort of distrust towards institutions and dissatisfaction with the functioning of the democratic political system in Spain. This should be understood as apathy, however, as the pandemic promoted a politicization of Spanish youth, in terms of greater interest and participation in politics, especially in non-institutionalized ways [27]. On a more localized level, the results of the 2020 Barcelona Youth Survey showed that a majority of young people are interested in politics [28]. We must acknowledge, however, that these results differ slightly from those drawn by the 2022 Youth Status Report in the Catalonia region, which shows that only 25% of young people are satisfied with democracy and less than 50% interested in participating in society [29]. All these data align with Frances-Garcia’s [26] findings, which indicated a contrast between youth’s high appreciation of the democratic system as preferable to any other system (79.2%) and approximately half of those surveyed not being very satisfied with the way democracy works in Spain.

Spanish youth also take this approach to democratic development. Their forms of participation are often ‘non-electoral’ and ‘non-institutionalized’ and are sometimes categorized as ‘protest activities’. A fundamental aspect of the current youth condition is the result of experiences of social and political re-existence that include protest and resistance practices, as well as the creation of alternative projects in open dispute with hegemonic sectors, institutions and the procedures of formal democracy [30]. Research also indicates an evolution from a generalist movement, to movements of a single subject, and finally to mobilization for discrete events [31]. This contradicts previous findings, which indicated that the structures of youth groups tend to abandon excessively rigid institutional frameworks in favor of horizontal networks that enable communication between different fields of action [26]. They also refute a previously observed rise in the mechanism of specific activations and deactivations, often multi-subject in nature, in which young people constantly enter and exit participatory processes characterized by an increasing flexibility and transience in their actions [26].

In Catalonia, findings have long been in accord with these global trends. According to San Martin [32], “young people are more active in those ways of participation -such as social associationism or protest participation- in which they can better defend their interests, work together and/or express their discomfort with the functioning of traditional democratic political institutions”. The 2017 Participation and Politics Survey in Catalonia highlighted youth distancing itself from involvement in institutional and party-based politics, accompanied by the emergence of an engagement more strongly linked to causes and everyday political experiences, as this cohort was clearly most in favor of a more participative democratic model [33].

2. Materials and Methods

To find answers to our two questions, the Barcelona Youth Council 1 and the ERDISC Research Group 2, from the Autonomous University of Barcelona, initiated a study in January 2023. The target population were young people participating in one of the 247 community-based, youth-led organizations registered in the city of Barcelona.

2.1. Research Design

For the successful achievement of our research goals, we designed a process in three phases based on Creswell’s mixed methodology, so that each phase could fulfill a specific dimension of the research. The first phase was devoted to mapping youth attitudes, opinions and values concerning politics and civic participation through a quantitative survey based on previous validated instruments. The second phase was focused on a qualitative approach to the youth voices so that we could identify the main categories that are underpinning those attitudes, opinions and values. Through focus group interviews we aimed to raise these comprehensive categories. Finally, from a prescriptive approach, we wished to design some policy recommendations and some training aids for youth organizations, based on the needs and expectations previously detected. A Delphi method with experts and youngsters was the most convenient tool.

The results we explore in this paper are based on the first phase, aiming to make a first introduction to mapping youth attitudes, opinions and values regarding democracy and civic participation. We implemented quantitative data collection to examine youngsters’ self-perceptions regarding their behavior in their organizations. In order to collect data, we applied a validated instrument adapted to the Catalan reality and the purpose of our research.

We identified an instrument that was a suitable base for our aim: the Tiffany–Eckenrode Program Participation Scale (TEPPS), a reliable scale measuring the quality of youth programs’ participation, developed as part of the Complementary Strengths Research Project (CSRP), a community-based participatory research (CBPR) project carried out in 2005 in New York City involving Cornell University, government agencies and community-based organizations (Tiffany, 2012).

The original measure is a 20-item scale, with responses measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all true for me) to 5 (very true for me). Higher TEPPS scores indicate higher levels of program participation. The items are divided into 4 subscales, from which we used only 3, measuring personal development (PD), voice/influence (VI), and community engagement (CE). The scale we used was also translated and adapted to the language and reality of the target group of participants (Catalan).

Confirmatory analysis was used to examine the optimal subscale structure and global consistency after our adaptation, using Cronbach’s alpha index. Cronbach’s alpha for the global scale was 0.78, and the values for the 3 subscales were 0.7 (PD), 0.75 (VI) and 0.61 (CE).

In addition, we designed the questionnaire to provide a socio-demographic profile of the sample population. On this basis, we included 13 socio-demographic items (e.g., age, gender, education, and current occupational status of the respondents), as well as a series of questions about their organizations and participation patterns.

Apart from the socio-demographic items and the participation scale items, we added to the questionnaire 4 political attitude questions and 4 organizational governance questions, all of them with responses measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale. These items were not included in the statistical bivariate analysis of the scale, and we analyze the answers separately in the results chapter, for the key information they provide in the study of youth political attitudes and governance.

Finally, we also included three open-ended questions to the questionnaire, to generate a more in-depth understanding of youth participatory experiences, which they could choose not to answer: (1) please tell us your main motivation to participate in your organization, (2) please tell us an action carried out in your organization that enhanced or still enhances your participation, and (3) please tell us the best and worst aspect of how your organization is being managed.

The whole instrument was peer-reviewed by 9 academic experts and 2 members of Barcelona Youth Council before its administration to the target population.

2.2. Sample: Selection Criteria and Respondents

As we have already mentioned, the target group of our research was the whole universe of young people aged 16–29 participating in community-based youth-led organizations in the city of Barcelona.

The questionnaire was administered online and disseminated among the whole target group by the Barcelona Youth Council’s internal and external communication channels (e-mail, social networks), and the individual consent was included within the questionnaire form. By the end of April 2023, we had a total of 129 responses to the questionnaire, and 70 of these also responded to the open-ended questions. The main characteristics of the final sample can be found in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample. Source: authors.

Descriptive analysis revealed the following modal value of our data set: women (58.91%), less than 23 years old (78.65%), born in the city of Barcelona (89.1%), having finished post-compulsory studies (92%); 79.84% were employed—albeit only 13.95% full-time. Despite this fact, 82.17% still live in the family residence, and only 0.78% declare to live alone in an independent home.

Analysis of the sociodemographic answers is consistent with previous studies [34], and the reliability of the responses to the items of the scale makes the sample adequate for the purposes of our research. A larger sample could produce more accurate results.

Quantitative data analysis was performed using SAS V9.4 statistical analysis software, and consisted of a univariate and bivariate descriptive analysis, obtaining the figures corresponding to each item, as well as some statistically significant correlations between items and sample variables.

3. Results

3.1. Young People’s Participation Patterns

Results of univariate analysis of respondents’ participation patterns show a high participation in leisure time educational groups (63.57%), in front of self-managed youth centers (24.81%), cultural groups (3.88%), political organizations (4.65%) and social and political advocacy groups (3.1%).

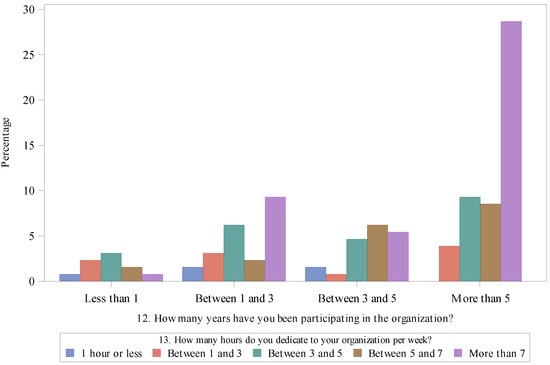

According to the analysis, respondents are long-term members of their organizations: 50.39% have been participating for 5 years or more, while only 8.53% have been participating for 1 year or less (see Table 2 and Table 3). The fact that 44.19% of respondents spend more than 7 h per week (only 3.88% participate 1 h per week or less) is also a reflection of the intensity of their participation, as we can clearly see in Figure 1. It is also important to note that 31.01% of respondents were engaged in more than one organization at the time they answered the questionnaire.

Table 2.

Engagement in youth-led organizations. Years of membership. Source: authors.

Table 3.

Engagement in youth-led organizations. Intensity of participation. Source: authors.

Figure 1.

Years of membership and intensity of participation in youth-led organizations. Source: authors.

The following figure clearly shows that a majority of the respondents are long-term members of their organizations and dedicate many hours per week to participating in them.

3.2. Participation Scale Results

The results of the univariate analysis of the adapted TEPPS participation scale shows a high participation index of the respondents in Barcelona, with a global index of 4.14 out of 5. The index was calculated by considering internal consistency. The figures for each item can be found in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Mean and standard deviation of adapted TEPPS participation scale items. Source: authors.

3.2.1. Personal Development Subscale (PD)

Concerning their personal development, 88.4% of the respondents found their participation stimulating or very stimulating, and 93.8% felt that it was a space for them to learn. Only 55.8% thought their participation would help them find a job, 86.1% of the respondents felt respected by responsibility-holders in their organizations and 89.9% felt safe or very safe when participating in the activities.

Results in this subscale show that respondents consider their participation in a youth-led organization to be a very positive space for their personal development. The type of organization or the intensity of their participation (hours/week) does not make a statistically significative difference in their responses.

3.2.2. Voice/Influence Subscale (VI)

Results in this subscale give a very interesting point of view about respondents’ perception of their involvement in organizations and their influence in decision-making processes—two of the main motivations for young people to participate in youth organizations, according to the analysis of the open-ended questions in our questionnaire. As many as 79.8% expressed it was easy to become involved, while 82.2% felt very involved in the organization’s activities. A large majority (94.6%) declared that they participate in decision-making processes—none of them answered 1 in this item. Thus, 75.2% stated that they have influence in their organization’s regular decision-making areas.

Results from bivariate analysis showed that the ones that perceived that they have slightly more voice and influence in their organization were 18–23-year-olds, currently working, with post-graduate studies, and having spent more years in the organization. There were no significative differences determined by gender.

We also found a significative difference in the answers based on the intensity of participation: the more intensity, the more voice/influence young respondents perceive they have in their organization.

3.2.3. Community Engagement Subscale (CC)

Although 67.4% of the respondents considered that their organization collaborates with other services from the neighborhood, and 66.6% of them assert that they have changed the way they treat their neighbors, only 40.3% asserted that the way people from their neighborhood treat them has changed since they have been participating in the organization. The most positive aspect from this subscale is the fact that 82.1% of the respondents would like to keep participating in community projects after they leave their organization.

The results of the bivariate analysis showed that youth centers/assemblies were the type of organizations where respondents felt more engaged with the community.

3.3. Political Attitudes and Organizational Governance

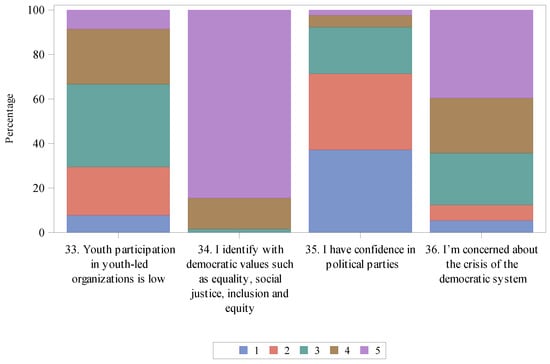

Apart from the adapted TEPPS participation scale, there were eight items to measure political attitudes and organizational governance of youth. The four items measuring political attitudes gave very significant information about respondents’ views on democracy, as we can see in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Political attitude answers. Source: authors.

With respect to democratic attitudes, a substantial majority (98.5%) of respondents identify with democratic values such as equality, social justice, inclusion and equity, presenting women and people aged under 26 with slightly higher identification values. This identification with democratic values rises in proportion to the number of years the respondent has been a member of the organization. We observed a tendency—the more years respondents have been participating, the more they identify with democratic values, as seen in Table 5.

Table 5.

Bivariate analysis of items 34 and 12. Source: authors.

When asked about their concern for the crisis of the democratic system, 64.3% of respondents declared themselves to be concerned, while only 5.4% said they were not at all concerned. However, we need to highlight that only 7.7% of the respondents declared that they trust political parties, compared to 71.3% who report having no or almost no trust at all.

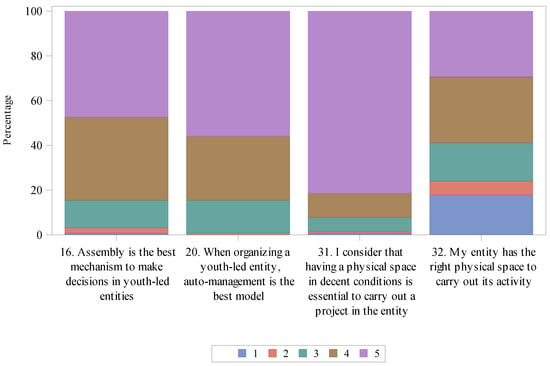

Finally, an overview of young people’s answers about what would be the best system to organize and manage a youth-led entity shows us that 84.5% believe that self-management is the best option, and that assembly is the best decision-making mechanism for taking decisions, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Organizational governance answers.

We can find some coincidences between the high marks in item 20 (self-management as the best model) and the high marks in item 14 (participation in decision-making). More than half of the respondents (65.6%) who participate in decision-making processes in their own organizations consider self-management to be the best model. A similar pattern can be found between item 16 and item 14 (the 52.2% who answered 5 in item 14 also answered 5 in item 16 (assembly as the best decision-making mechanism).

3.4. Open-Ended Questions

When explaining what motivates them to participate in their organizations (open-ended question 1), respondents mention aspects in two directions: personal benefits (a sense of belonging, emotional bond with the organization, learning and personal development, fulfillment, socialization and meeting people, connection with the organization’s values), as well as social benefits (to give back what they have received, local and global social transformation, impact on children).

The connection I have for the years I passed in it, the people who welcomed me, everything that it has given me as a person, and the little bit I can give back to leave the world better than I have found it.(R34)

What mainly motivates me is to break with the institutionalized spaces that we find everywhere and to organize young people to build things for ourselves is a very nice thing. To give space and voice to a part of the population who that does not usually have it, because of their precarious situation or for the simple fact of being young(R49)

We find internal consistency between these answers and the high values registered in the participation subscales PD and CC.

The participation of respondents in their organizations is enhanced by numerous actions (open-ended question 2). We highlight two: to take part in the preparation of the activities, and to hold roles of representation or leadership inside the organization. Special activities carried out to improve the quality of participation of members are also considered as positive (for instance, team building, peer tutoring or training programs).

To be part of the organizational staff of the entity and to participate in the organization of events beyond our entity (with other entities in the neighborhood, for example)(R119)

Peer-mentoring activities between more experienced people and new people, activities to know each other and to do teambuilding(R80)

When giving examples about the best practices in the management of their organization (open-ended question 3a), they mostly point to assemblies, real inclusion of all voices, self-management and taking care of people as the most valued. As for the worst practices (question 3b), they write about financial dependence on external bodies, long and ineffective decision-making processes, inadequate leadership and low engagement.

A very positive aspect is that we work in an assembly and we all know how the entity works and this makes us feel that we belong to it and a stronger identity.(R176)

Depending on who takes the lead within the steering committee, you have to carry a heavy workload, or people get relaxed and don’t do much.(R125)

4. Discussion

Our results allow us state that, as a matter of fact, civic engagement and volunteer participation in community-based organizations promotes high-quality participation experiences, improves civic attitudes, enhances democratic political behavior and provides a background for democratic political activism. Such groups help people learn how to address problems collectively, and to self-organize to improve common life [35]. Social, civic, and political youth-led organizations strengthen youths’ social bonds and develop their sense of community. Thus, they both are and should be an active part of the structural associative framework in any healthy democracy.

At the beginning of our research, we asked ourselves if the declining satisfaction tendency of young people towards democracy is the real attitude of the youth. First, the results of our research dismantle this argument. Our findings indicate that our respondents are long-term members of community-based, youth-led organizations, who believe in democratic values, are concerned with the crisis of the democratic system and, at the same time, believe in a bottom-up democratic system that they translate to their organization’s decision-making processes and management.

These results align with previous studies and are consistent with former conclusions—that young people are not disconnected at all from the civic life of their communities [5] and that they are turning to democratic horizontal organizations and community networks instead of engaging in traditional formal democratic institutions.

However, there is a cause for concern in the data. The intense involvement of respondents in youth-led organizations, their strong alignment with democratic values (98.5%) and, simultaneously, their remarkably low trust in political parties (7.7%), prompt us to consider the critical importance of the crisis facing our current democratic political system. We believe that the erosion of trust in institutional democratic representation, particularly from an educated and socially engaged youth, creates an opening through which populism can gain a foothold. This phenomenon poses a significant challenge to the future legitimacy of the democratic system.

That said, here comes the key challenge to be considered: how to transfer this activism that comes from youth activism to those non-organized young people, as well as to democratic institutions. Data tells us about a gap. Both youth in general and democratic institutions should be more aware about the significant social task that young activists are performing from their own organizations, and likely these youngsters’ organizations should spend more effort on communicating and establishing bonds with their mates and institutions. Young civic organizations are called to become the subject of a counter-narrative that promotes a social ethos where both polarization and populism make no sense. Since our research also provides evidence that enlightens our comprehension of the disaffection of youth with formal democratic political participation, in the upcoming phases we will explore the root causes of the loss of trust in political parties and how to build up this counter-narrative, by using qualitative methods.

At the same time, our study underscores that, in line with Martinez-Cousinou et al. [17], one of our core challenges as a democratic society is to nurture and promote an engaged and participatory citizenship. Public administration plays a major role in providing this support. Further research in this direction should attempt to describe and analyze the ways in which youth-led organizations receive support from administrative institutions and propose measures to encourage and enhance the performance of these organizations. Research can also explore its role in city decision-making processes and their integration into formal community networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.À.E.; methodology, M.À.E.; validation, M.À.E.; formal analysis, A.T.; investigation, M.À.E., M.N. and A.T.; data curation, A.T. and M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N. and A.T.; writing—review and editing, M.À.E.; visualization, M.N.; supervision, M.À.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the National and Regional Rules on Research Ethics.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the reported results are available by communicating with the authors and describing the purpose of the use of these data.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the essential support of the Barcelona Youth Council, the Barcelona City Council, and all the youth-led organizations involved.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | https://www.cjb.cat (accessed on 22 November 2023). |

| 2 | https://webs.uab.cat/erdisc/equip (accessed on 22 November 2023). |

References

- Foa, R.S.; Klassen, A.; Wenger, D.; Rand, A.; Slade, M. Youth and Satisfaction with Democracy: Reversing the Democratic Disconnect? Centre for the Future of Democracy: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Identidad; Losada: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, P. Young People & Political Activism: From the Politics of Loyalties to the Politics of Choice? [Report for the Council of Europe Symposium: “Young People and Democratic Institutions: From Disillusionment to Participation.”]; Harvard Kennedy School: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, C.; Keeter, S.; Andolina, M.; Jenkins, K.; Delli Carpini, M.X. A New Engagement? Political Participation, Civic Life, and the Changing American Citizen; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cammaerts, B.; Bruter, M.; Banaji, S.; Harrison, S.; Anstead, N. The Myth of Youth Apathy: Young Europeans’ Critical Attitudes Toward Democratic Life. Am. Behav. Sci. 2014, 58, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, M.; Weinstein, M.; Forrest, S. Uninterested Youth? Young People’s Attitudes towards Party Politics in Britain. Political Stud. 2005, 53, 556–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberlee, R.H. Why Don’t British Young People Vote at General Elections? J. Youth Stud. 2002, 5, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattenberg, M. Is Voting for Young People? Pearson Longman: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta, M.; Cancela, J.; Martín, I.; Tsirbas, Y. Trust, Satisfaction and Political Engagement during Economic Crisis: Young Citizens in Southern Europe. South Eur. Soc. Politics 2021, 26, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janmaat, J.G. The Impact of the Recession on Young People’s Satisfaction with Democratic Politics. In Young People’s Development and the Great Recession, 1st ed.; Schoon, I., Bynner, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 372–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, G.G.; De Sousa, L. Legal Corruption and Dissatisfaction with Democracy in the European Union. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 140, 653–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armingeon, K.; Guthmann, K. Democracy in crisis? The declining support for national democracy in European countries, 2007-2011: Democracy in crisis? Eur. J. Political Res. 2014, 53, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, B.; Wolfers, J. Trust in Public Institutions over the Business Cycle. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, J.; Mounk, Y. The Populist Harm to Democracy: An Empirical Assessment; Tony Blair Institute for Global Change: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boese, V.; Alizada, N.; Lundstedt, M.; Morrison, K.; Natsika, N.; Sato, Y.; Tai, H.; Lindberg, S. Autocratization Changing Nature? Democracy Report 2022; Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem): Gothenburg, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Diaz, L.J.; Danet, A. De lo ideológico a lo afectivo. Lecturas actuales sobre la participación y la polarización juvenil ante el auge de la derecha radical. Rev. Int. Pensam. Político 2022, 17, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Cousinou, G.; Camus-Garcia, E.; Alvarez-Sotomayor, A. Juventud universitaria e interés por la política: Análisis de un estudio piloto. Rev. Int. Pensam. Político 2022, 17, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deth, J.W. Studying Political Participation: Towards a Theory of Everything? Paper presented at the Joint Sessions of Workshops of the European Consortium for Political Research; ECPR: Mannheim, Germany, 2001.

- European Parliament; Directorate General for Communication; Ipsos European Public Affairs. European Parliament Youth Survey: Report; EP Publications Office: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2861/60428 (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Dalton, R.J. The Good Citizen: How a Younger Generation Is Reshaping American Politics; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, R.; Wicks, R.H. Political Socialization: Modeling Teen Political and Civic Engagement. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2011, 88, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnå, E.; Ekman, J. Standby citizens: Diverse faces of political passivity. Eur. Political Sci. Rev. 2014, 6, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P. Democratic Phoenix: Reinventing Political Activism; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Juanatey, A.G. El extremismo de Derecha Entre la Juventud Española: Situación Actual y Perspectivas; Instituto de la Juventud: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, M. Formes de participació i actituds polítiques del jovent a l’Estat espanyol: Són tan diferents? Nous Horitzons. 2010, 199, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Francés García, F.J. El laberinto de la participación juvenil: Estrategias de implicación ciudadana en la juventud. OBETS Rev. De Cienc. Soc. 2008, 2, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J. What Is Youth Political Participation? Literature Review on Youth Political Participation and Political Attitudes. Front. Political Sci. 2020, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. Enquesta a la Joventut de Barcelona 2020. Informe de Resultats; Àrea de Drets Socials, Justícia Global, Feminismes i LGTBI; Ajuntament de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- de la Joventut, O.C. Estat de la Joventut 2022; Generalitat de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2022.

- Amador-Baquiro, J.C.; Muñoz-Gonzalez, G. Del alteractivismo al estallido social: Acción juvenil colectiva y conectiva (2011 y 2019). Rev. Latinoam. De Cienc. Soc. Niñez Y Juv. 2020, 19, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, F.J. Qué sabemos de la participación política de los jóvenes en democracia. Una revisión de las problemáticas sobre los jóvenes, la participación política y la democracia: Presentación del monográfico. Rev. Int. Pensam. Político 2022, 17, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martin, J. Participació política i joves: Una revisió del grau de participació en funció de l’edat. Nous Horitz. 2010, 199, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Soler-Marti, R. Joventut, implicació i context polític a Catalunya: Una anàlisi de l’Enquesta de participació i política 2017. Col·lecció Estudis. 2019, 37. Available online: https://dretssocials.gencat.cat/web/.content/JOVENTUT_documents/arxiu/publicacions/col_estudis/estudis37.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Nadeu, M.; Tarrés, A.; Essomba, M.A. Actitudes y prácticas interculturales de educadoras y educadores en el tiempo libre en Cataluña. In Ocio Educativo y Acción Sociocultural: Construyendo Modelos Para el Desarrollo de Personas y Comunidades; Morata, T., Palasí, E., Graó, Eds.; Revista de pedagogía: Bordón, Spain, 2023; pp. 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, L.; Geurts, P. Associational involvement. In Citizenship and Involvement in European Democracies; Van Deth, J.W., Montero, J.R., Westholm, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).