Abstract

The paper aims to analyze, on one hand, the evolution and interpretation of graffiti and street art phenomenon in the Romanian capital, Bucharest, and at international level, and on the other hand how this subculture is related to aspects of culture and heritage. The analysis of the evolution followed by graffiti and street art in Bucharest is doubled by the investigation of the messages transmitted in relation to the national and local culture and history, as street art may be seen as an efficient tool contributing to local cultural identity building. The methods used rely on a complex approach, combining observation and photos from field research, documentation, and data collection from different organizations and online communities. Street art works have various positive effects on the urban landscape, including in relation to culture and heritage in time. The results demonstrate that in Bucharest, street art contributes to highlighting mainly the key-moments and the personalities in culture and history that contribute to shaping a part of cultural identity.

1. Introduction: Understanding Graffiti and Street Art as Concepts and Urban Subculture

Graffiti, etymologically originating from the Italian word “graffiare” which means to scratch [1], is a very complex phenomenon. The history of graffiti may be associated to epigraphs and representations discovered in archaeological sites or on the walls of various buildings, which date from antiquity and are testimonies of the time in which they were carried out, as well as to hoboglyphs developed in the early 20th century in the USA during the great economic crisis of the 1930s. The so-called hobos, whose name means, in English, homeless people, were, in fact, a very specific type of homeless traveler, “nomadic” workers who voyaged without tickets on freight trains searching for a job, communicating with each other through various graphic signs [2,3]. These secret codes on trains and in train stations were intended to give information on the best places to camp or find a meal, or dangers that lay ahead [4]. Their representation was made not only on trains but, as in the case of contemporary graffiti, on buildings, telegraph poles, fences, gates, bridges, etc., through geometric shapes (circles, squares, rectangles, and triangles), numbers, arrows, and other type of lines. Hobo graffiti is a part of the larger overall history of graffiti, where wall markings are about illegally emplacing a name on property, symbolically stating their presence as a member of minority subculture [3].

Graffiti and street art, an important urban subculture in the 21st century, are nowadays almost pervasive in public spaces and represent an international phenomenon as a whole of artistic expression and a subculture referring to groups within a culture with shared values, behaviors, and sometimes experiences. The contemporary graffiti and street art phenomenon has known several main stages: the 1950s—an initial stage of using stickers was inspired by publicity methods, in which stickers are used to tag a surface without writing; these were usually designed and printed well ahead, containing traits of an artist’s style as well as their message [5]; the late 1960s—the first tags arise in Philadelphia [5,6] and are developed in New York City [7] as a need to develop a place for socialization or organization of groups at the level of large multicultural cities, based on the idea of creation and expression [8]; the 1970s—spraying of letters, nicknames, and tags (firstly in New York subway) come with more obvious challenges of defending public spaces from these inscriptions, followed by anti-graffiti laws; in certain areas, the lack of exhibition spaces in the 1970s is at the basis of the phenomenon explosion (e.g., in Berlin) [6]; the mid-1970s—stylistic standards, bombing methods, painting techniques, and aesthetic frameworks are evident and the representation supports are becoming more and more diverse, especially in New York: trains, bridges, walls, tunnels, windows, doors, derelict and abandoned buildings [9]; the 1980s—hip-hop, rap, punk, and rock culture enhance more durable to already existing political and social slogans; at the same time, new laws will join those adopted in the USA [9]; the mid-1980s—more laws restrict the sale of spray to minors; the 1990s—this new subculture is brought more in Europe, different types of American-inspired representations developing in European countries (Belgium, France, Germany, etc.) with postal stickers free of charge, development of tags, stencils graffiti, posters and stickers; as it happened in USA, in Europe more anti-graffiti laws were adopted in order to control the phenomenon, especially after 2000 (Germany, France, United Kingdom, Spain, Netherlands etc.); in the last two decades, graffiti evolves towards and together with street art.

In former socialist countries (Poland, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Romania, Bulgaria, etc.), graffiti and street art representations have become increasingly visible since the 1990s. Their spread did not happen in exactly the same order as in the country of origin, USA, when talking about media types, causal factors, and, therefore, typology of representations.

This artistic movement has developed in time into a sophisticated cultural phenomenon [10] from which street art detached. Even if street art emerged from graffiti, the boundary between these two ways of expression is very unclear. The differentiation between graffiti and street art is often arbitrary and lacks consistency [11]. Like any art, it can be subjective. Nevertheless, there are significant differences that separate the two currents which go beyond the main difference imposed by illegal actions, such as vandalism, versus authorized interventions, with the permission of buildings’ owners or commissioned walls in street art projects. Subcultural graffiti is related to illegal interventions [12] or so-called “graffiti vandalism” to separate it from street art (or so-called “graffiti art” in the 1990s) [13]. However, street art, like graffiti, is more often than not done without permission and practiced by people coming from the graffiti subculture [11]. The other important differences may be seen in terms of: (a) beginnings—graffiti precedes and inspires street art; (b) visual representations and their interpretation—if graffiti typically relates to a range of practices from tagging to “pieces” with a focus on stylized words and text, very complex and difficult to be understood by the wider public, street art forms present a more public address, a broader set of artistic practices less tied to the subcultural practices and conventions associated with graffiti [11,14,15,16] or, otherwise, graffiti relies mainly on words (letters and sprays that give birth to different shapes and styles) compared to street art representations, which do not involve a decoding of letters as graffiti but of transmitted symbols and messages; (c) authors—although writers and street artists often share similar backgrounds [17], graffiti authors are mostly self-taught versus those of street art who require in general formal training and skills in painting and art; (d) impact in the landscape—some research focus on the valorization of the “street art” power to activate space versus increasing criminalization of “graffiti” [11]. At the same time, they have similarities when viewed in relation to development and affirmation: graffiti emerged both from inner city neighborhoods and peripheries as a type of self-expression for urban youth, similar to street art, which certainly is developing more in the central and semi central areas but for another reason. The city centers and nearby neighborhoods are areas that are intensively transited and visited. In this way, the respective representations become pieces of art in an open-air museum, so in places full of history and culture. As for temporality, there are both similarities and differences. Indeed, both graffiti and street art are ephemeral, being placed in open spaces and, therefore, with a degree of resistance depending on a number of factors (weather conditions, colors’ quality, local urban policies, subsequent interventions over works undertaken by the communities, etc.). However, while street art is in essence permitted, graffiti is often an act of resistance or challenge (e.g., illegal bombing etc.).

Graffiti representations, whether they are stencils, stickers, tags, etc. can be found in a wider range of media: fences, gangways, abandoned industrial buildings (temporary uses in brownfield areas), walls, high walls, depots, garages, shutters, billboards, fire alarms, including moving media such as cars, trucks, trains, or cargo ships [5,18]. In general, abandoned places are preferred because they may not imply authorization, or at least at first sight, and places in transition (neighborhoods). On the contrary, street art is more linked to commissioned walls and fences, sometimes in the framework of urban regeneration projects [18].

The evolution of graffiti phenomenon towards street art has led to the shaping of two perceptions of this subculture as mentioned above, which are not always correct—negative versus positive. Usually, graffiti has remained at the stage of stencils on various media and is seen in general as a form of vandalism on the building aesthetics and design features [12,19,20,21]. Street art is characterized by more esthetic representations, having fewer rules and a wide range of styles and techniques, sometimes combined and imported from graffiti. It becomes interesting when graffiti finds as media not only bare walls, but walls covered with murals that represent a piece of the local graffiti history and of this subculture as a whole: e.g., high-profile murals dedicated to 1984 Olympics [22].

Street art may be seen as a subversive art, the subversive being understood as the capacity to challenge the corporate regime of visibility, meaning “those social norms regulating visibility in the modern city, by appropriating public space in carnivalesque ways”. This makes street art stand apart from official public art, while graffiti is at its very core [17]. These are related to urban art, a validated and acclaimed artistic field, referring to “a combination of techniques and pictorial formats (spray painting, stencil, reverse graffiti, stickers, etc.) generally associated with art practices developed originally in urban public spaces” [23].

2. Materials and Methods

The purpose of the study is to analyze the main differences in the evolution of graffiti and street art phenomenon, internationally and in Romania, with an in-depth investigation inside the Romanian capital, Bucharest, and from the perspective of the relationship in time between graffiti and street art/local culture and heritage. Culture and heritage are perceived as an important component of identity. The cultural dimension is important in the identity building, a complex and multifaceted process [24]. Beside referring to collective knowledge such as traditions, heritage, language, aesthetics, norms, and customs [25], the cultural identity is a social construct involving questions about conceptions, understandings, and lived experiences regarding the self in relation to others across time, space, and context [26]. The study does not aim to investigate the perception of this subculture in general, namely the appreciation of representations, where graffiti stops and street art begins, or the participants in this creative activity. To enable this international comparative analysis, the field research was limited to large and very large urban areas, capitals, or cities with a cultural function.

At a national level, Bucharest was chosen as a case study because it is the largest city and the capital of Romania, the phenomenon experienced here being the most dynamic evolution in time after 1990. In order to identify the progress trajectories, respectively, the similarities and differences in development and in relation to culture and heritage, the study relied on the following research questions: (1) What is the path of the international and national graffiti and street art phenomenon? (2) What are the main media for graffiti and street art representations in the urban landscapes? (3) Where is the place of culture and heritage on different types of representations in Bucharest and in the messages transmitted?

In the process of finding the answers to these research questions, the methodological steps included: (1) Inventory of different components in the urban landscape with graffiti and street art works based on field research; (2) Typology of urban components hosting art works; (3) Interpretation of typology’s different components (called in the article graffiti and street art media or new canvas) based on: similarities and differences in relation to most sought canvas; temporal discrepancies between international and local levels; place of culture and heritage among the topics addressed; (4) In-depth analysis of culture and heritage dimensions in the representations of graffiti and street art in Bucharest, with concrete examples in different areas.

The research methods included: documentation in scientific articles, books, and other publications for graffiti and street art analysis at international level and then in Bucharest [27,28,29] and mass-media; field research (observation and comparison methods) and photos taken in different moments and places with graffiti and street art between 2012 and 2022 as source material; collecting online data from different organizations, groups of interests and social media. In the description of the different art works, details were mentioned about the work, author, and year of execution. Despite assiduous research, unfortunately incomplete information was found in some cases. Where information was not identified, no data was mentioned below the photos.

3. Graffiti and Street Art—Approaches and Meanings

The scientific research about graffiti and street art phenomenon takes into account, to a large extent, aspects of legality, namely authorized interventions or acts of vandalism, but also social insight given its context of occurrence, from recognition of artistry to interpreting it as a sign of urban decay and disorder [30]. There is not much research regarding the impact that this phenomenon as a whole has in communities. Recent research is more about focused approaches in certain directions that help in understanding cities at a general level or in a city or community and analyzing graffiti works in particular, or in association with murals: e.g., a critical social and spatial practice, an alternative approach to cultural development by and for young people in areas marginalized by the mainstream practice of culture-led economic development, relying on different assets, like hip-hop etc. [31]; a way of communication [32]; spatial practices as markers of a globalizing and glocalizing world, in relation to migrants [33]; a feminist urban subculture and how women negotiate their place in the subcultures from different positions [34]; as a form of communication or advertising in a context where graffiti is seen as a sign of social disorder [30]; as contemporary forms of youth leisure: role of skateboarding, graffiti and the augmented reality game Pokémon Go, as youth leisure practices, in the restructuring of the urban imaginary and the production of the public space [35]; semiotics approach of street art from metaphoric point of view [36]; territorial approach: reappropriation and rearrangement of urban areas (e.g., in Berlin—after unification [37]); political graffiti [38].

To these, numerous analyses and volumes can be added that make a radiography of the phenomenon and present the situation of this movement at some moments in different geographical areas (from metropolitan cities to larger geographical areas, even global interpretations), e.g., [5,39,40,41]). Together with articles from the media (the first to pay attention to this phenomenon in the 1960s), these publications have the role of contributing to the promotion and recognition of this subculture and, usually, include a presentation of the works themselves accompanied by a short story of the authors and topics covered. It reveals the importance that media has had on the graffiti movement. Lately, online media has promoted this phenomenon considerably more, which proves that graffiti has always been dependent on communication.

However, graffiti and street art may be considered an art form, not just a subculture, as it is proven by an ongoing project put into practice in 2014 by a street artist, Julien de Casabianca, who goes further to state the place of this artistic current and creates a bridge between art in closed and open spaces, supporting and promoting it from museums into the street, closer to people. Thus, in the period 2014–2022, within the project entitled ”Outings”, which consists in bringing paintings from museum walls into the streets, a series of representations in the form of murals of famous paintings were made in many cities from Europe, and also from America and Asia [42]: France (Paris, Montargis, Angers, Bordeaux, Orthez, Cugny, La Roche Sur Yon, Langres, Bayonne, Montauban, Ivry); Belgium (Brussels); Turkey (Istanbul); Germany (Berlin, Lübeck); Corsica; Switzerland; Scotland; several capitals of Central and Eastern European countries: Riga, Sofia, Belgrade, Zagreb, Ljubljana, Warsaw; USA (New York, Memphis, Galesburg, Jacksonville); Mexico (Torreon); Nepal (Kathmandu). Paste-ups in other cities around the world come in addition in the framework of the project.

Murals become a tool for making neighborhoods more attractive in many European cities (e.g., Belgrade, Kaunas, Gdansk, Antwerp, Ostend, Bristol, Malmo, Reykjavik, Budapest, Waterford) [43].

4. Results: Graffiti and Street Art at International and Local Level—A Comparative Analysis in Terms of Media for Works and Topics Related to Culture and Heritage

The representations chosen for the comparative analysis at an international and local level, Bucharest, are obtained in the field research and considered in a complex approach following the relationship with the territory. Thus, a series of particularities of the landscape in which street art representations are located are taken into account, including functional characteristics of the place and the degree of the buildings’ conservation.

The countries from Eastern Europe did not follow all the distinct steps of Western street art [44]. From a temporal point of view, the beginning of contemporary graffiti and street art dates back around the 1960s in USA, compared to Romania, which knows the first steps of this subculture only with the transition to the capitalist system in 1990. During the communist era in Bucharest some repetitive political messages could frequently be found on different types of walls and fences. These promoted a political movement in the 1946 elections, which saw the installation of the communist regime in Romania the following year. Larger representations took the form of mosaic murals concerning messages about the economic status, prosperity, and progress of the Romanian people [18]. In Bucharest, graffiti emerges gradually as a form of expression, decoded as a new way of life as it was at its origins, less artistic at first, and in which authors are seeking to relate to a modern culture rather than to the idea of delimiting their territory and recognizing others. If its early evolution was difficult, Romania’s accession to the European Union in 2007 opened new ways of asserting this subculture, from which street art becomes more visible. Therefore, street art is developing and gaining more consideration through the experience of international artists who paint murals in various projects, next to local artists. The projects are supported in general by the municipality, various institutions, associations, or private companies.

The ephemerality of the works and sometimes their overlap on the same media, elements that still characterize graffiti and street art, make an accurate analysis of their dynamics and typology in time and space impossible. The field analysis emphasized that the representations on different components in the urban landscape respond to various approaches and artistic experiences, including in relation to local and national culture and heritage. The research focused, as well, on those representations that do not transmit directly cultural and heritage messages, but which are found on media frequently encountered at both a national and international level.

The representations selected for the comparative analysis, international versus Bucharest (some of them are exemplified below—Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26, Figure 27, Figure 28, Figure 29, Figure 30, Figure 31, Figure 32, Figure 33 and Figure 34), capture the main types of media on which graffiti and street art works find their place. Some media that appear mainly only in certain cities (e.g., shutters, stairs, etc.) were not taken into account in the comparative research. The selected photographs are part of the author’s personal archive, except for those of the trains wagons from the 1970s and 1980s of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) in New York, important to be integrated in the analysis of the phenomenon evolution. Despite some limitations in conducting a comparative scientific study of graffiti and street art at an international and local level (e.g., ephemerality of work arts, possible bias in relation to field research etc.), several relationships could be established and general findings could be obtained, starting with the repetitive media and paying attention to cultural and heritage aspects as well.

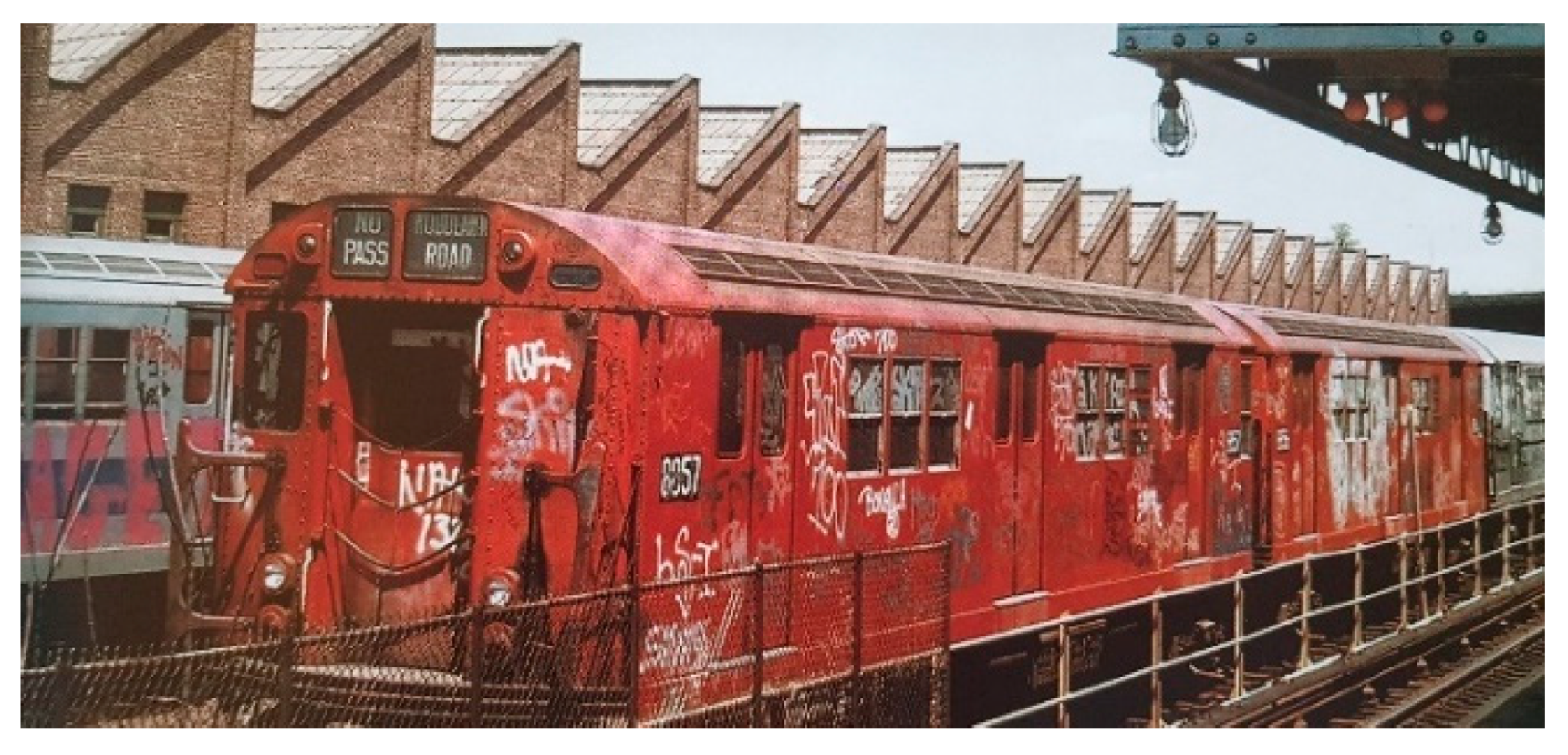

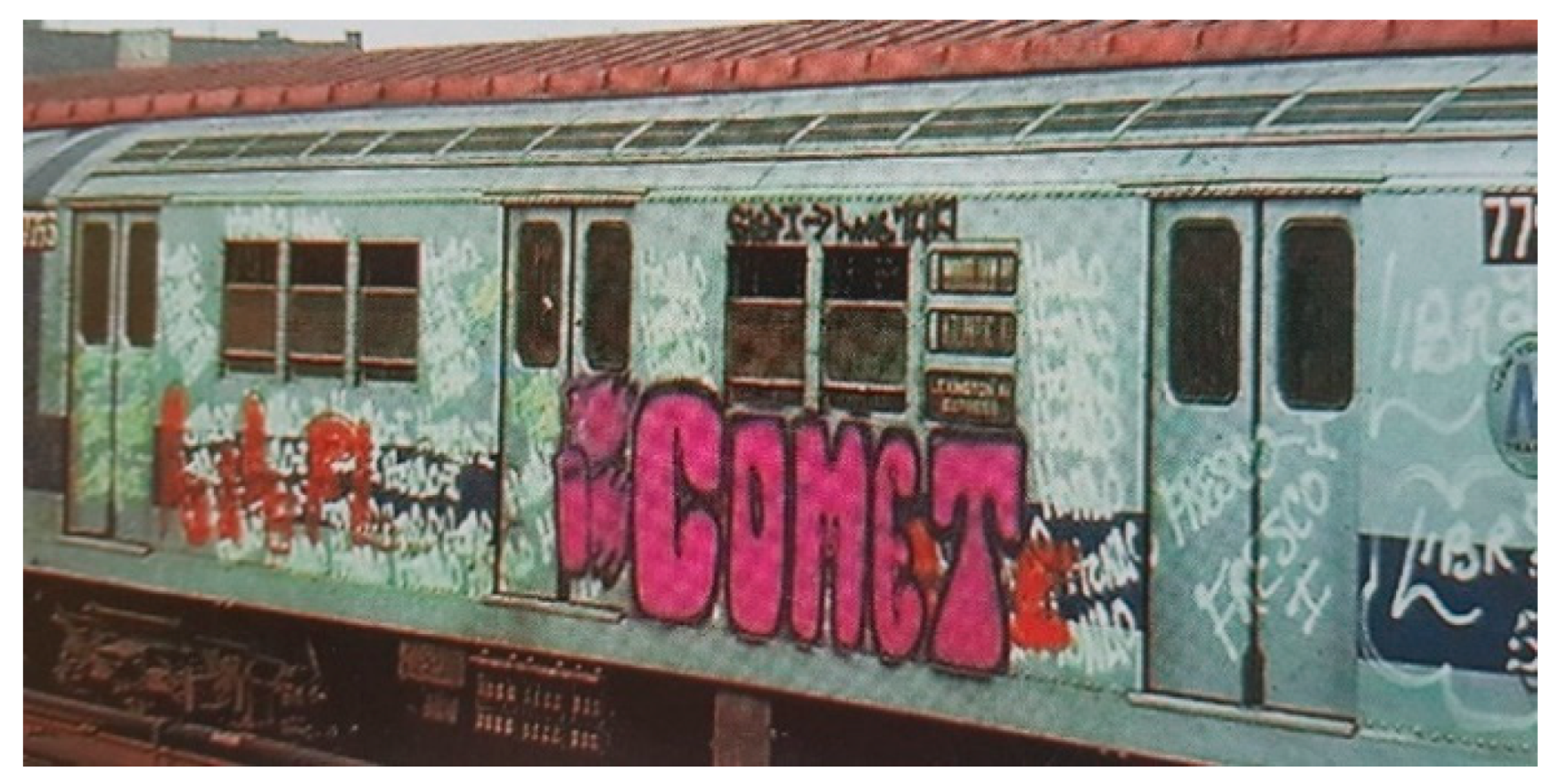

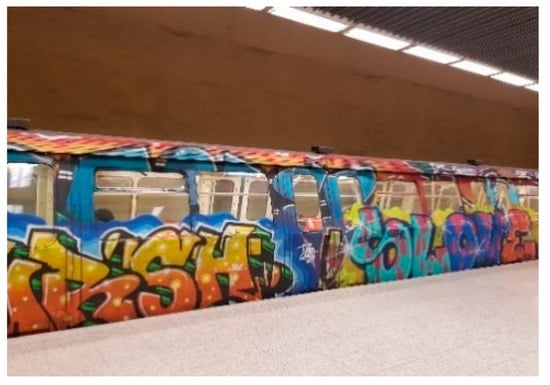

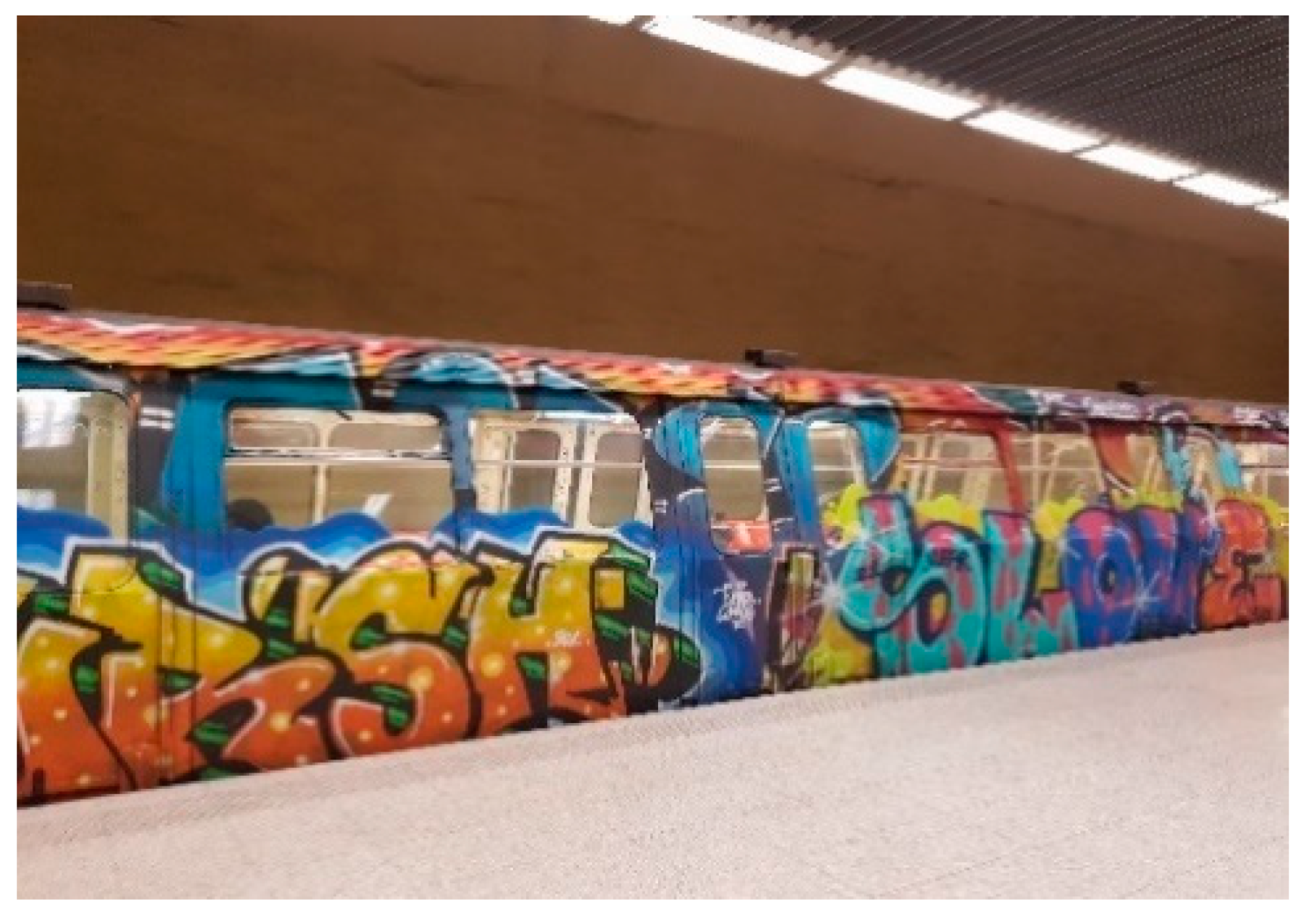

Regarding the first type of media identified, the wagons of the trains and subway system represented the starting step for this subculture in USA and for graffiti works (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). In time, this subculture moved in the interior, and nowadays, the mural mosaics in New York subway are the proof that identity is important, if we take into consideration the representations of some artists exhibited in various museums and, at the same time, art works in connection to culture and history in some subway stations. In Bucharest, subway coaches with graffiti (Figure 5 and Figure 6) and street art projects carried out by the surface and underground transport networks in partnership with various institutions or private companies can be exemplified. In 2008, at the North Railway Station, Bucharest metroArt project took place, with thematic paintings on existing mosaic walls related to Bucharest architecture and various older or newer means of transport. In 2020, on the occasion of celebrating 561 years of documentary attestation of Bucharest, the City Hall conducted the “Bucharest—One Heart. One Story” project, during which seven trams on different routes in the city have been personalized with different themes to express a part of the capital’s cultural identity. Carried out by the Center for Creation, Art and Tradition of Bucharest City Hall, the street artists had to express their perception about the public spaces and the architecture in Bucharest. On one tram, the representations of some emblematic personalities can be discovered: e.g., Queen Marie of Romania (1914–1927) (Figure 7), Mihail Kogălniceanu (Prime Minister of Romania in the second part of the 19th century), I. L. Caragiale (considered one of the greatest playwrights in Romanian language and literature), Toma Caragiu (a prolific Aromanian theatre, television, and film actor), and Ana Aslan (famous doctor who put the foundations of Romanian geriatrics and invented revolutionary products for treating diseases specific to the elderly). In 2020 and 2021, more street art projects were conducted in three other subway stations in order to add color to these urban underground spaces, sometimes accompanied by cultural elements. For instance, in 2021 at Ștefan cel Mare metro station, there was painted a mural as a tribute to Romanian champion canoeist Ivan Patzaichin who won the gold medal at Munich Olympics Games in 1972 (Figure 8).

Figure 1.

MTA trains, New York, in early 1970s Source: [5].

Figure 1.

MTA trains, New York, in early 1970s Source: [5].

Figure 2.

MTA trains, New York, 1972 Source: [5].

Figure 2.

MTA trains, New York, 1972 Source: [5].

Figure 3.

MTA trains, New York, 1979 Source: [5].

Figure 3.

MTA trains, New York, 1979 Source: [5].

Figure 4.

MTA trains, New York, 1980s Source: [5].

Figure 4.

MTA trains, New York, 1980s Source: [5].

Figure 5.

Subway wagon, Line 4, Bucharest, no data (photo taken in 2014).

Figure 5.

Subway wagon, Line 4, Bucharest, no data (photo taken in 2014).

Figure 6.

Subway wagon, Line 4, Bucharest, no data (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 6.

Subway wagon, Line 4, Bucharest, no data (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 7.

41 Tramway Line, Bucharest by Sweet Damage Crew, 2020 (photo in detail with the portrait of Queen Marie of Romania, taken in 2021).

Figure 7.

41 Tramway Line, Bucharest by Sweet Damage Crew, 2020 (photo in detail with the portrait of Queen Marie of Romania, taken in 2021).

Figure 8.

Ștefan cel Mare metro station, Bucharest, Ivan Patzaichin by Obie Platon, 2021 (photo taken in 2021).

Figure 8.

Ștefan cel Mare metro station, Bucharest, Ivan Patzaichin by Obie Platon, 2021 (photo taken in 2021).

Regarding the media represented by educational units’ high walls and fences, it records, all over the world, the widest range of topics addressed in relation to the different facets of education (Figure 9 and Figure 10): environment protection, tolerance and communication, culture, including cultural personalities etc. Figure 9 represents the largest rendering of the campaign named “Education Is Not A Crime” across Harlem. It all started in New York City in the early 1980s, when large-scale murals saw the day as a collaborative work in Spanish Harlem. Graffiti Hall of Fame was the first legal venue with several large walls in a school yard. In Bucharest, in recent years, a number of famous street artists have been involved in transmitting messages through street art not only on the walls of some schools or high schools but also on the corridors or walls of some higher education institutions. The messages can be related to education, history, artistic themes, or about humanity needs like respecting the environment more (Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Figure 9.

School in Harlem, New York by Elle, 2016 (photo taken in 2020).

Figure 9.

School in Harlem, New York by Elle, 2016 (photo taken in 2020).

Figure 10.

Bohermore Community Centre, Galway, no data, 2014 (photo taken in 2019).

Figure 10.

Bohermore Community Centre, Galway, no data, 2014 (photo taken in 2019).

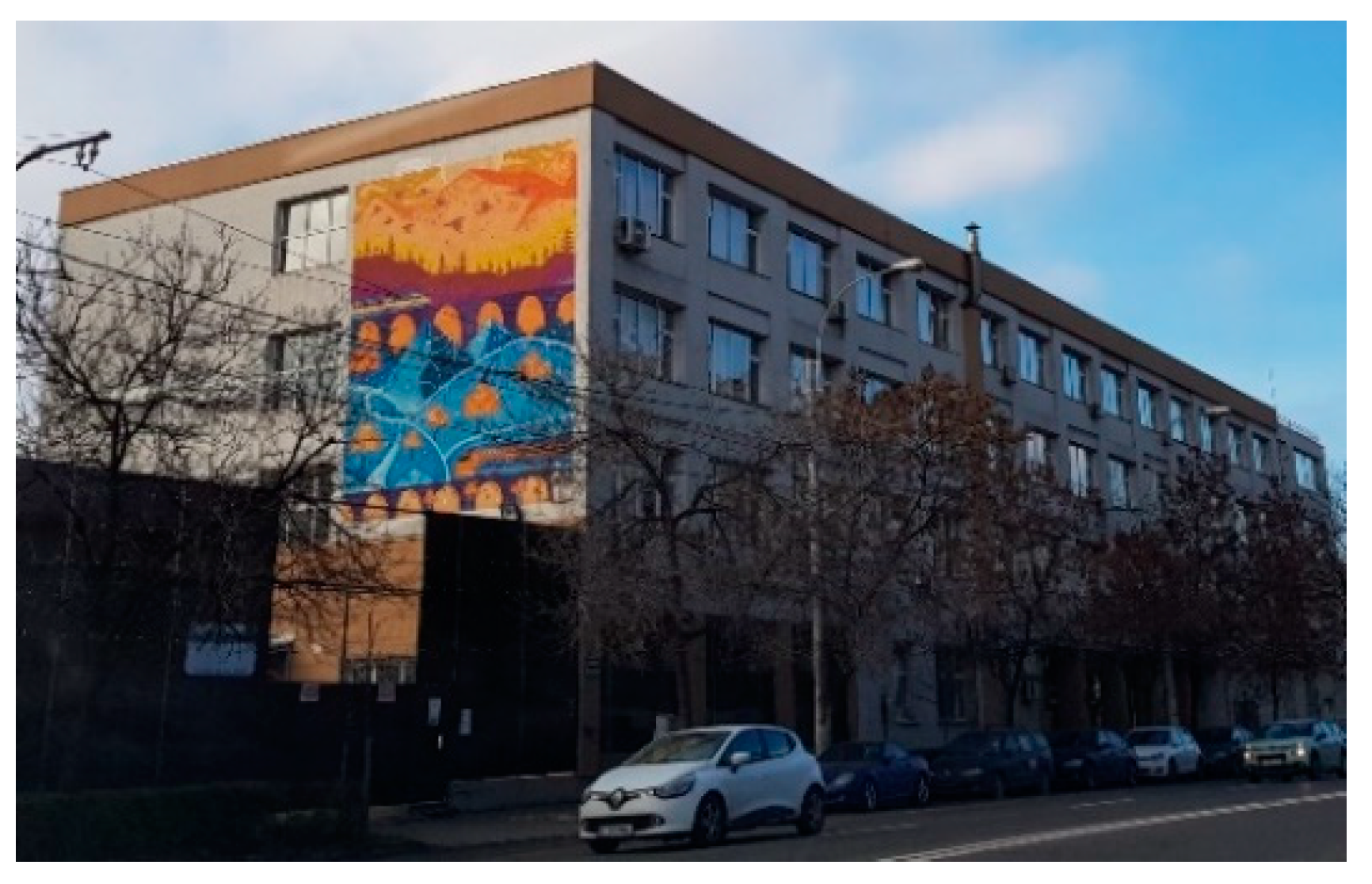

Figure 11.

Grivița Mechanical Technical College, Bucharest by Score–KAPS, 2018 (photo taken in 2020).

Figure 11.

Grivița Mechanical Technical College, Bucharest by Score–KAPS, 2018 (photo taken in 2020).

Figure 12.

CINETIC, National University of Theatre and Film “I.L. Caragiale”, Bucharest by Pisica Pătrată, 2017 (photo taken in 2021).

Figure 12.

CINETIC, National University of Theatre and Film “I.L. Caragiale”, Bucharest by Pisica Pătrată, 2017 (photo taken in 2021).

However, perhaps the most popular category among street artists is given by different other categories of walls and fences that convey various messages: e.g., cultural identity in Quiberon, a century-old seaside resort and a former sardine port in Brittany with a mural showing fisher folk dancing in their normal costumes from the 19th century (Figure 13), representations related to the traditional port, local economic activities and personalities from different fields in Praia, Capo Verde (Figure 14 and Figure 15), or just a piece of color to increase the visibility of old buildings representing an important stage in the history of the city in Budapest (Figure 16—the Fire Hall, situated next to an old and abandoned important building, Merlin Theater). At a national level, fences are hosting similar works, but those coming from graffiti component abound. Usually, the following general types of host fences are encountered as media: fences of some abandoned constructions, of former technical and industrial units (Figure 17), and along the railway and soundproof fences. Fences with street art representations emerged recently (Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20).

Figure 13.

Quiberon, no data (photo taken in 2018).

Figure 13.

Quiberon, no data (photo taken in 2018).

Figure 14.

Mural in Plato District, Praia, no data (photo taken in 2019).

Figure 14.

Mural in Plato District, Praia, no data (photo taken in 2019).

Figure 15.

Mural in Plato District, Praia, no data (photo taken in 2019).

Figure 15.

Mural in Plato District, Praia, no data (photo taken in 2019).

Figure 16.

Fire Hall and Merlin Theater, Budapest, no data (photo taken in 2012).

Figure 16.

Fire Hall and Merlin Theater, Budapest, no data (photo taken in 2012).

Figure 17.

Former industrial fences in the North part of Bucharest, no data (photo taken in 2021).

Figure 17.

Former industrial fences in the North part of Bucharest, no data (photo taken in 2021).

Figure 18.

Arthur Verona st., Bucharest by VVANDERBUTCH, 2019 (photo taken in 2021).

Figure 18.

Arthur Verona st., Bucharest by VVANDERBUTCH, 2019 (photo taken in 2021).

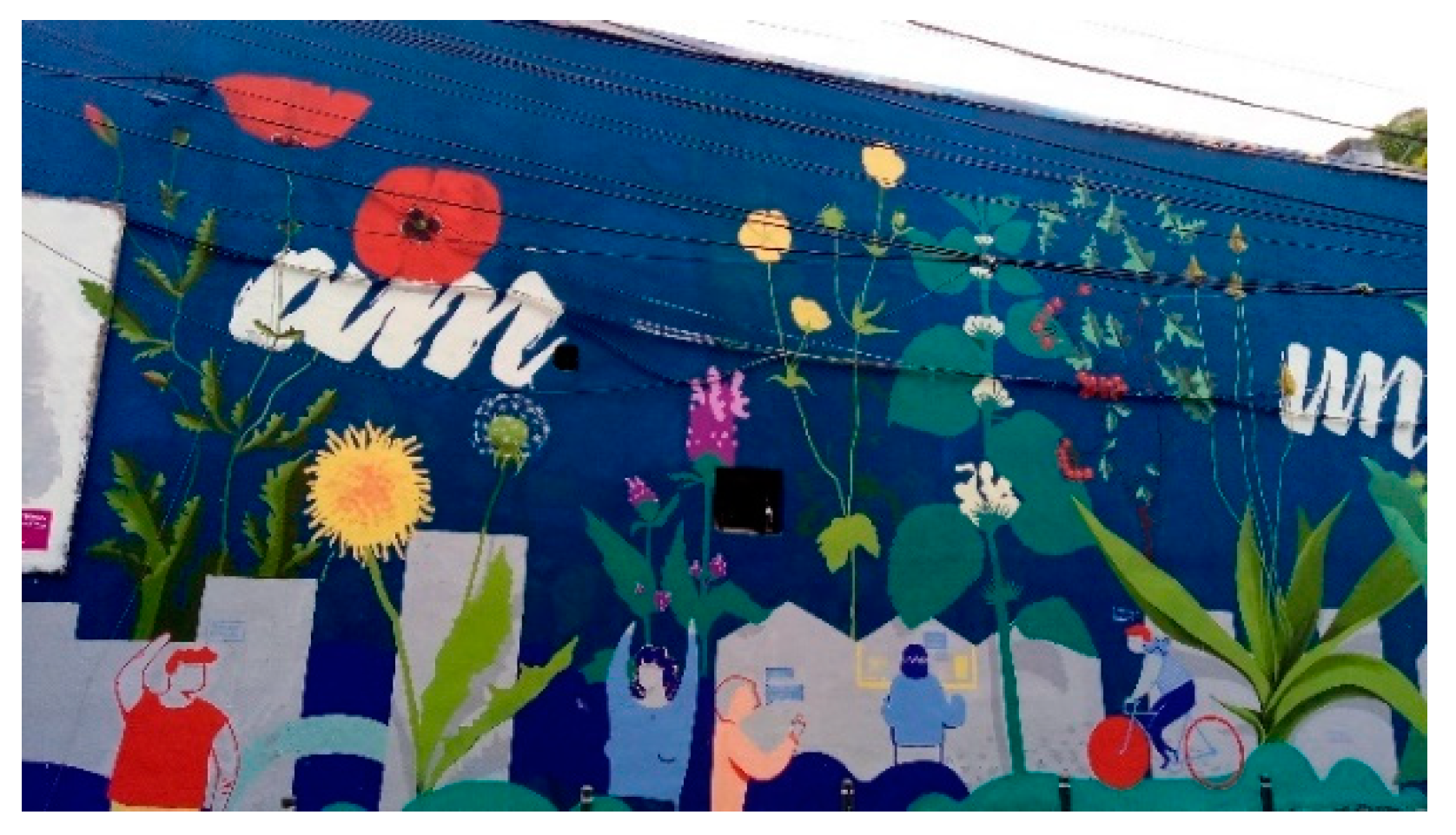

Figure 19.

Campus 6.3. offices area, Bucharest, no data (photo taken in 2021).

Figure 19.

Campus 6.3. offices area, Bucharest, no data (photo taken in 2021).

Figure 20.

Ion Creangă Theater, Administrative headquarters, Bucharest, no data (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 20.

Ion Creangă Theater, Administrative headquarters, Bucharest, no data (photo taken in 2022).

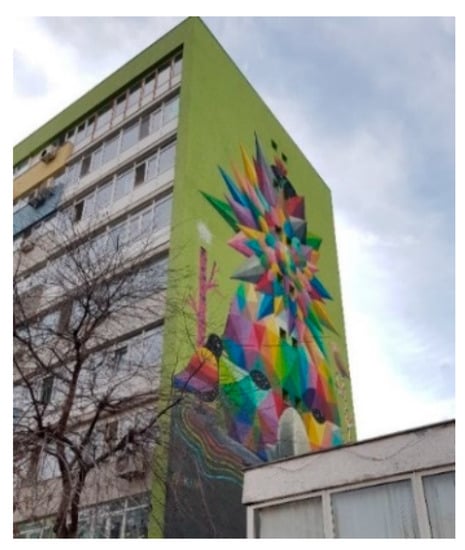

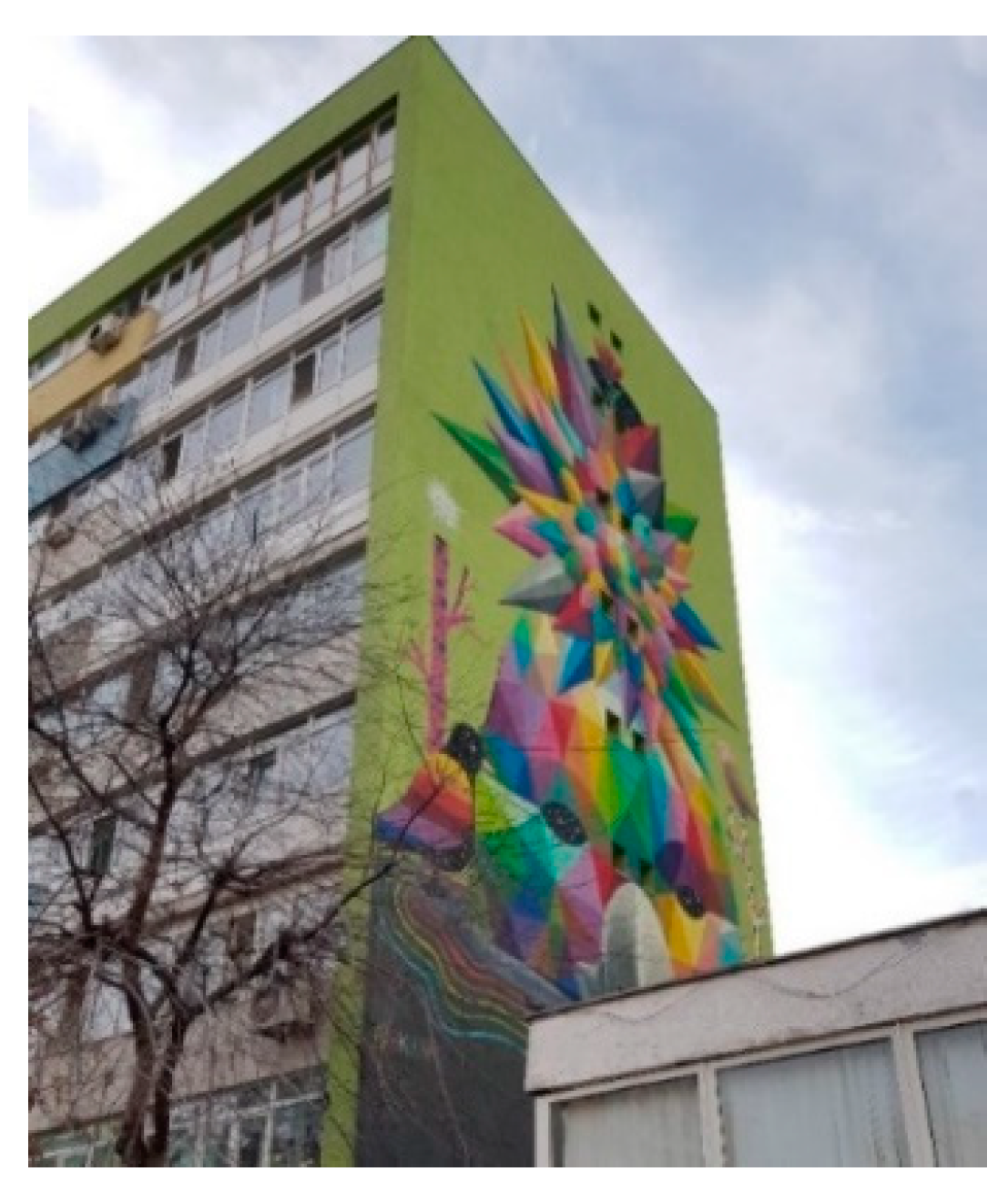

Regarding the residential buildings high walls, they are suitable for large-scale murals, the themes being very generous, including in relation to the local culture: e.g., the history of comics in Brussels with the mural “The Adventures of Tintin”, a series of 24 comic book series created by the Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi, who wrote under the pen name Hergé (Figure 21); in Madrid, the life of the neighborhoods in the past can be admired on a mural representing thirty-six figures dressed in clothes from the beginning of the 20th century, along with numerous objects that remind us of how Sundays were when Rastro flea market was organized (Figure 22); in Galway, a mural which refers to the richness of the local literature, including a quote from a poetry of a Irish novelist, Dermot Healy (Figure 23). In Bucharest, more and more large-scale murals can be found, with various representations that bring color to the buildings partially or completely and are associated with some already reputable street artists: e.g., in the framework of the Street Delivery Festival (Figure 24) that takes place every year on Arthur Verona street, considered the start of street art in Bucharest [18]). In 2021, the largest mural from Bucharest was completed, an entire block of flats situated in a crowded intersection being painted during its process of thermal rehabilitation (Figure 25). However, the representations may also have a direct message to transmit: e.g., a mural that is part of the project “Murales para la Libertad” (carried out by the Embassy of Spain in Budapest, Sofia, and Bucharest) dedicated to the Spanish diplomats that helped save Jewish citizens during the second world war: to Jóse Rojas and Manuel Gómez-Barzanallana, ministers of the Spanish Legation in Romania between 1940–1945, who saved from extermination over 100 Sephardic Jews in Bucharest during the Second World War (Figure 26).

Figure 21.

“The Adventures of Tintin of Hergé”, Brussels by Oreopoulos G. and Vandegeerde D., 2005 (photo taken in 2015).

Figure 21.

“The Adventures of Tintin of Hergé”, Brussels by Oreopoulos G. and Vandegeerde D., 2005 (photo taken in 2015).

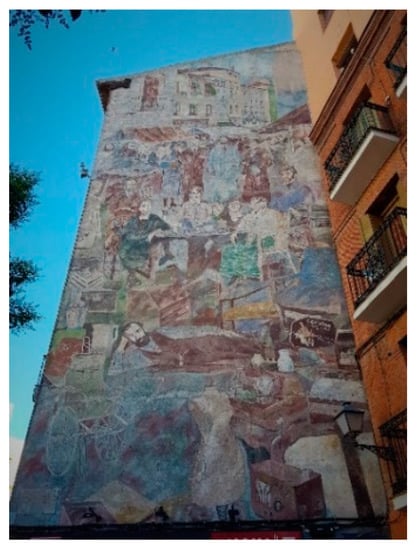

Figure 22.

Mural Plaza de Cascorro, Madrid by Enrique Cavestany, 1983 (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 22.

Mural Plaza de Cascorro, Madrid by Enrique Cavestany, 1983 (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 23.

“But someone has missed the bend for home”, Galway by Finbar247, 2015 (photo taken in 2019).

Figure 23.

“But someone has missed the bend for home”, Galway by Finbar247, 2015 (photo taken in 2019).

Figure 24.

“I have a city”, Arthur Verona st., Bucharest by Livi Po and other street artists, 2018 (photo taken in 2018).

Figure 24.

“I have a city”, Arthur Verona st., Bucharest by Livi Po and other street artists, 2018 (photo taken in 2018).

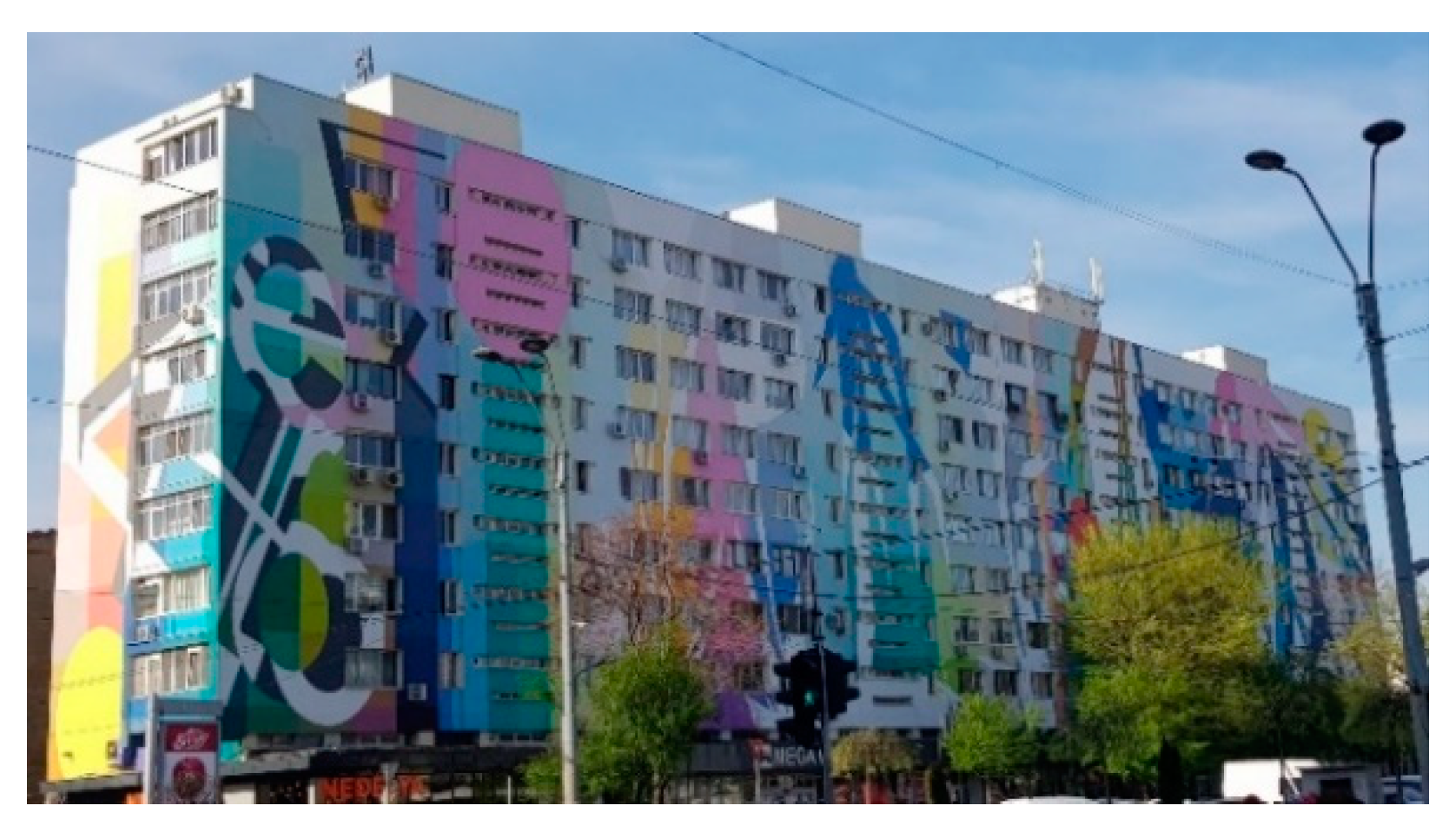

Figure 25.

42 Marășești st., Bucharest by Dumitru Gurjii and Mircea Modreanu, 2021 (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 25.

42 Marășești st., Bucharest by Dumitru Gurjii and Mircea Modreanu, 2021 (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 26.

“Bird of Freedom Paradise”, Unirii Square area, Bucharest by San Miguel Okuda, 2017 (photo taken in 2021).

Figure 26.

“Bird of Freedom Paradise”, Unirii Square area, Bucharest by San Miguel Okuda, 2017 (photo taken in 2021).

Old and derelict (including heritage) buildings present an evident interest for graffiti and street art authors. Graffiti inscriptions on this category of media are less visible at international level especially when it happens to historical monuments because of the legislation that protects the built heritage by applying harsh sanctions: e.g., some small representations in the port area of Dublin—The British and Irish Steam Packet Company building or in Brussels—the old Belle-Vue brewery in Molenbeek, today reconverted in hotel. Sometimes, graffiti and street art come within functional reconversion projects and commissioned art works: e.g., in Milano, Fabbrica del Vapore, from production of rolling stock for trains and tramways to creative activities nowadays and a mural celebrating 20 years of freedom in South Africa and representing Nelson Mandela (Figure 27).

Figure 27.

“20 Years of Freedom and Democracy”, Milano by Pao Pao, Nais, Orticanoodles, and Ivan, 2014 (photo taken in 2018).

Figure 27.

“20 Years of Freedom and Democracy”, Milano by Pao Pao, Nais, Orticanoodles, and Ivan, 2014 (photo taken in 2018).

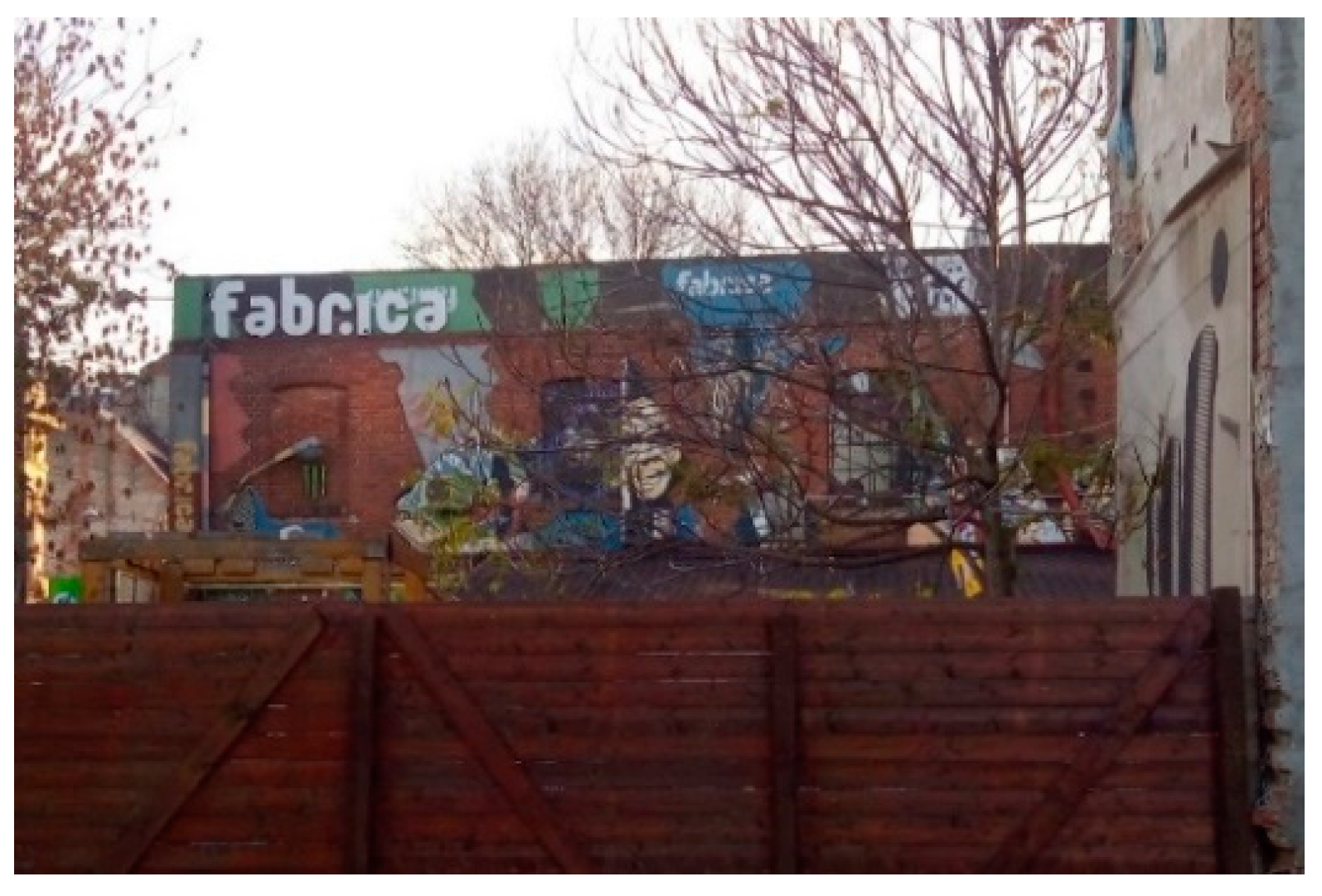

On the contrary, at a national level, the legal recognition of some buildings in the category of those that are and should be protected and preserved does not always weigh in the decision-making process of graffiti and street art. By abandoning them, they become an easier target of the graffiti and street art phenomenon. However, there are also positive examples in which old constructions find a new functionality, usually in the direction of creative industries, but remain at risk on long term: e.g., Republica ex-industrial platform, an important former steel pipe factory with a mural by Robert Obert and Pisica Pătrată (also known as Alexandru Ciubotariu) or Fabrica (Figure 28), a former socks factory that today hosts a club, together with creative activities.

Figure 28.

Fabrica Club, June 11 st., Bucharest by Valentino Vasile and other street artists, no data (photo taken in 2019).

Figure 28.

Fabrica Club, June 11 st., Bucharest by Valentino Vasile and other street artists, no data (photo taken in 2019).

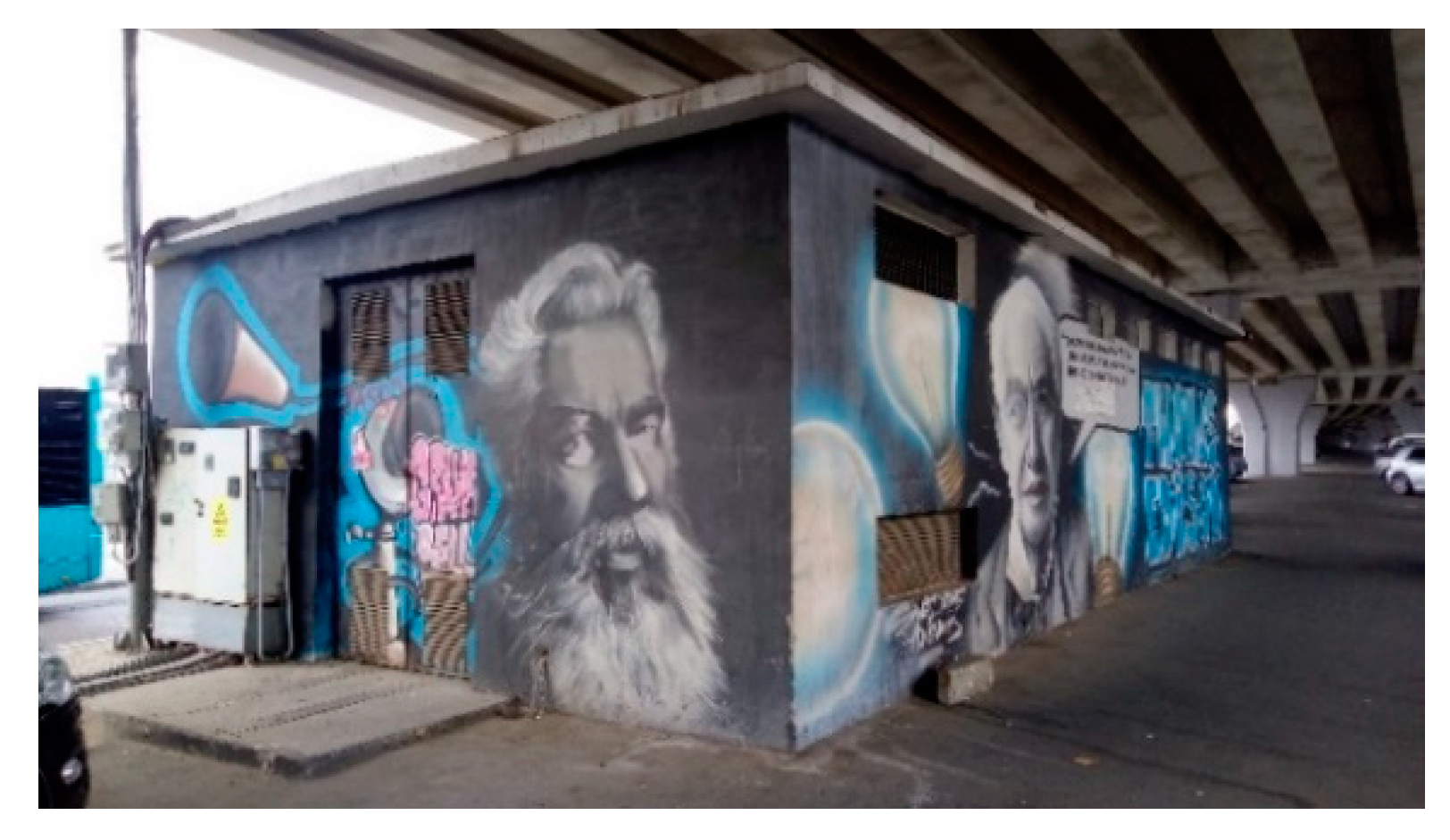

Electric transformer stations are another common support for graffiti and street art in the last years, sometimes transmitting messages in relation to culture and heritage. Electricity transformation stations, together with distribution power stations, heating stations, and other elements of technical and municipal infrastructure, including garbage cans, have already become customary canvases for street art in Western Europe: e.g., in Berlin, within a bar that, before 1990, was a permanent representation of the Federal Republic of Germany (Figure 29), or in Dublin (Figure 30). In Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria, representations of the traditional costumes can be found on an electricity transformation station (Figure 31). In Bucharest, it can be mentioned a project carried out by an electricity supplier for the reintegration of old energy transformation stations in the Bucharest landscape and called “City of Energy”: e.g., in an area with administrative, cultural, and tourism importance for the capital, on one energy transformation station, the pioneers of Romanian aviation were highlighted (Figure 32—Aurel Vlaicu, described below in the Discussion section); on another one, situated in an area of the city with the highest concentration of ITC multinational companies, the personalities are represented to whom a series of innovations are related to: Thomas Edison, Graham Bell, Nikola Tesla, and Guglielmo Marconi (Figure 33). Examples of the representations on this media have increased lately in Bucharest, many of them transmitting artistic messages or in relation to the city in general (Figure 34).

Figure 29.

Schiffbauerdamm st., Berlin, no data (photo taken in 2018).

Figure 29.

Schiffbauerdamm st., Berlin, no data (photo taken in 2018).

Figure 30.

Dublin, no data (photo taken in 2019).

Figure 30.

Dublin, no data (photo taken in 2019).

Figure 31.

Veliko Tarnovo, no data (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 31.

Veliko Tarnovo, no data (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 32.

Aurel Vlaicu, Kiseleff Park, Bucharest by Fear and Suflo, 2014 (photo taken in 2017).

Figure 32.

Aurel Vlaicu, Kiseleff Park, Bucharest by Fear and Suflo, 2014 (photo taken in 2017).

Figure 33.

Under Pipera Bridge, Bucharest by Mihai Comănescu (Boeme), 2013 (photo taken in 2020).

Figure 33.

Under Pipera Bridge, Bucharest by Mihai Comănescu (Boeme), 2013 (photo taken in 2020).

Figure 34.

Mihail Kogălniceanu Square, Bucharest, no data (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 34.

Mihail Kogălniceanu Square, Bucharest, no data (photo taken in 2022).

The selected and presented above examples highlight the idea that the graffiti and street art phenomenon in Bucharest followed an approximately similar path to the international level. However, the more recent visibility of this subculture in Romania also explains certain disproportions given by a higher share of graffiti representations, more frequent cases of historical monuments with graffiti representations and unauthorized street art, but at the same time an effervescence of art works that emerge on all types of urban media. Evident differences can also be found: in the case of the walls or fences media, the cultural component is less encountered than at an international level; railroad graffiti is much less encountered than internationally, and rather on freight trains; instead, it exists on a certain subway line in Bucharest. In general, as for the European examples, many countries have pursued solid policies to stop the phenomenon on the trains and subway system wagons. In Romania, a law that will introduce harsher sanctions for unauthorized representations is in progress for approval.

As mentioned at the beginning of this section, the different representations chosen for the comparative analysis were studied and observed in a more complex approach, taking into account their relationship with the territory. The following conclusions could be drawn both at an international and local level: (1) There is a correlation between the functional state of the media, a good degree of buildings’ conservation, and the legality of the interventions both internationally and in Bucharest. In almost all situations, the impact that the representations have in the territory is positive in terms of good image, social, and economic development; (2) When referring to low degree of buildings’ conservation, neglected, abandoned, and non-functional spaces, the number of illegal graffiti and street art interventions is increasing. Less often, this type of intervention can lead to an increase in the visibility and appreciation of the area for future investments; (3) Regarding their location, the central areas have an advantage (less applied in the case of representations on educational units) and the works contribute to the growth of tourism in comparison to the media from the peripheries, rather associated to former industrial buildings where creative activities are currently carried out. However, it becomes difficult to analyze at a particular level and fully confirm these findings in the absence of databases, with details regarding graffiti and street art works and difficulties in obtaining information in the field for each case study.

5. Discussion

Having an impact on communities and intercultural exchanges, graffiti and street art reveal, through various representations, the historical, cultural, and heritage dimensions in contemporary spaces. The phenomenon facilitates the connection of some symbols from a local context to the neighborhood. Specific forms of cultural identity become more noticeable thanks to street art, which may contribute to recovering and developing urban areas with the support of the local population and associations [45]. The same reality starts to be more visible in Bucharest and proves, to a certain extent, the fact that the phenomenon of street art contributes to the identity saving of some areas of the capital. Examples of preserving or saving the cultural identity of a place can take many forms, from simple warning signs on the situations’ gravity to cultural identity coagulation initiatives and, in the happiest cases, to projects implemented with positive results for the community. Street art, along with graffiti, tells stories of the city and they become, in many cases, a tool to regain it. Frequently, the motto for graffiti and street art is positive, seen to some extent as a realignment of the city as a place for people who live in it: e.g., a message on a wall in Bucharest says: “The city must be won back!”. This means a further reappropriation of the city by the younger generation, who subject it to new challenges in its development and cultural identity.

Graffiti and street art can thus serve as a powerful means for reading, writing, and knowing the city [7]. Field research has revealed that street art pieces on topics related to local or national culture and heritage are not predominant in the city center but frequently appear on various media in the dormitory neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city. In addition to those mentioned in the results section, other examples can be highlighted for Bucharest. The central area can be exemplified in the following: on the wall of a block entrance near Nicolae Tonitza High School of Fine Arts are represented the Arch of Triumph from Bucharest, Intercontinental Hotel (a symbol for the capital architecture from the last 50 years and recently renamed Grand Hotel Bucharest) and the famous sculpture of Constantin Brâncuși, the “Endless Column” from Târgu Jiu, along with the Eiffel Tower from Paris, Big Ben from London, and skyscrapers from New York. Thus, the emphasis of the local cultural identity is doubled by the national one, and the representation of some internationally renowned architectural symbols can be translated by trying to highlight the importance of local ones, a way of saying that they are not inferior but connected and just as important and positioned accordingly alongside international benchmarks.

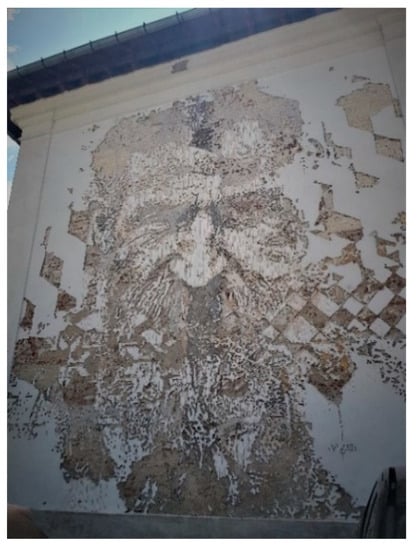

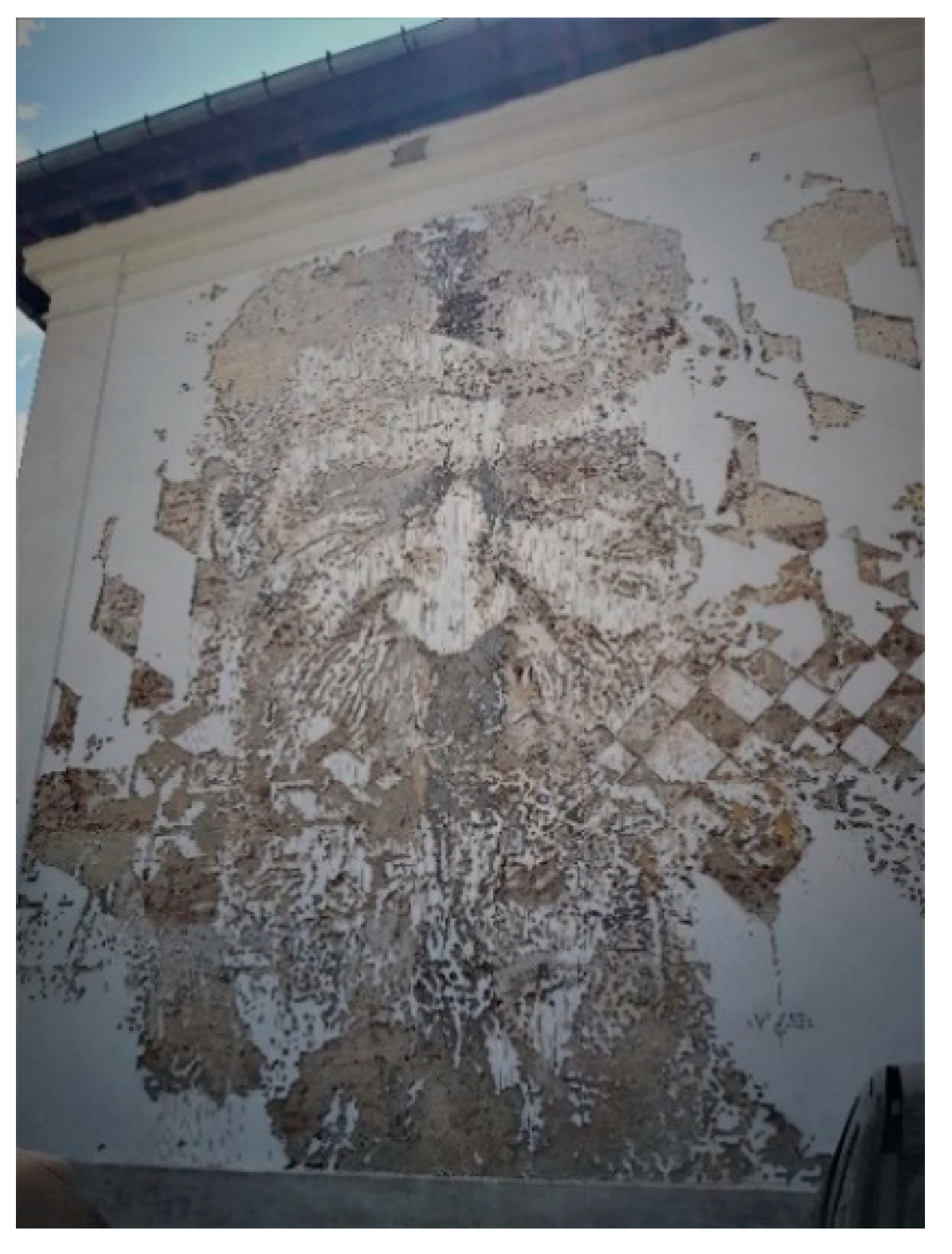

On the district heating stations media, portraits of Romanian personalities coming from different fields (political, cultural, artistic etc.) and their achievements are encountered: e.g., representations with Tudor Vladimirescu, a Romanian revolutionary hero on a district heating station from a neighborhood and the portrait of the sculptor Constantin Brâncuși and one of his worldwide known works of art, “Miss Pogany”, on another one (Figure 35). The first mural representation of Constantin Brâncuși took place in 2016 on one of the walls of the Bucharest National University of Arts (UNArte) (Figure 36). Additionally, in 2016, in the yard of the University of Architecture and Urbanism Ion Mincu, the portrait of the architect that gave the name to this educational institution was painted (Figure 37).

On a mural painted for a pub in the city center of Bucharest one can admire street art pieces with Bram Stoker and Vlad Tepeș, the prince of Wallachia, who inspired his character Dracula (Figure 38). On a side of a socialist bloc of flats, one can observe at first sight the representations of a girl who shoots at the spindle, a theme inspired by the “evening sittings”, small gatherings in the villages in which the participants work and spend time, telling stories and jokes. With a more detailed analysis of “Moira” by Recis, Sweet Damage Crew, the face of an old woman is also perceived, the message sent being related to the transmission of the customs’ importance from one generation to another.

Figure 35.

Brâncuși, Ștefan cel Mare neighborhood, Bucharest by Ortaku, 2018 (photo taken in 2021).

Figure 35.

Brâncuși, Ștefan cel Mare neighborhood, Bucharest by Ortaku, 2018 (photo taken in 2021).

Figure 36.

Brâncuși, UNArte, Bucharest by Vhils, 2016 (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 36.

Brâncuși, UNArte, Bucharest by Vhils, 2016 (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 37.

Ion Mincu, UAIM, Bucharest by Obie Platon, Sandu Milea Lucian, and Alex Brat, 2016 (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 37.

Ion Mincu, UAIM, Bucharest by Obie Platon, Sandu Milea Lucian, and Alex Brat, 2016 (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 38.

Vlad Țepes and Bram Stoker, Știrbei Vodă st., Bucharest by Obie Platon, 2014 (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 38.

Vlad Țepes and Bram Stoker, Știrbei Vodă st., Bucharest by Obie Platon, 2014 (photo taken in 2022).

Another example comes from the cinematographic Romanian history. In 2020, with the 100th anniversary of the first Romanian animated film, in the framework of the “Animest—International Animation Film Festival”, organized in Bucharest, an exhibition was dedicated to the most important moments in the history of local animated cinema and hosted by the cultural hub BRD Scena9 Residence. There, Romanian cartoon characters in relation to the history of the Romanian cartoons by Sorina Vazelina, Gri, Suzi, and Jo were represented: the first cartoon character, the well-known old children’s story transposed in animation and the evolution of films in socialist times (e.g., “Gopo’s Little Man”, the creation of Ion Popescu-Gopo, a prominent personality in the Romanian cinematography and the founder of the modern Romanian cartoon school, or “Mihaela and Azorel”, a cartoon series from the 1970s and 1980s). The national symbols are accompanied by representations of some international animation characters (e.g., “Pinocchio”) [18].

Murals of larger or smaller dimensions have spread as well in other areas of Bucharest: e.g., near the Romanian Orthodox Patriarchal Cathedral a paste-up as a tribute to two emblematic artists for the national culture can be found, Anda Călugăreanu and Margareta Pâslaru, an artwork signed by Sweet Damage Crew. On a transformation station located inside an important park in the northern part of the capital (and previously mentioned in the typology of media for graffiti and street art works) the pioneers of the Romanian aviation are highlighted (work of Fear and Suflo): Traian Vuia—inventor of the first aircraft with its own means of propulsion, with which he made the first flight in human history in 1906, rising from the ground by own means of the machine; Aurel Vlaicu—who designed the world’s first metal-built aircraft before the WWI, named A Vlaicu III; Henri Coandă—the inventor of the jet plane in 1910 and of the Coandă effect that will be named after him a few years later.

On the 30th anniversary of the Romanian Revolution from 1989, two murals were painted in 2020 in the hall of the Faculty of History of the University of Bucharest, highlighting the Revolution moments (Figure 39) and the phenomenon from the University Square (Figure 40).

Figure 39.

“Revolution from 1989”, University of Bucharest by Pisica Pătrată, 2020 (photo taken in 2022).

Figure 40.

“The University Square phenomenon from 1990”, University of Bucharest by Elann, 2020 (photo taken in 2022).

The examples described above are relevant for both local and national culture and history and are starting to see the light of the day more and more in the last years in Bucharest. However, there are also examples in which the graffiti and street art phenomenon, with the participation of the civil society, becomes an instrument that raises an alarm signal regarding the architectural heritage of Bucharest. At an international level, the growing involvement of the civil society in the direction of street art is evident [46]. At Halele Carol, a former metal construction fabric opened at the end of 19th century and integrated today into a cultural and creative reconversion project, a mural was painted by Sweet Damage Crew in 2018 as tribute for the father of cybernetics, Grigore Moisil. On the ruined walls of the Marconi Cinema, an historical monument that should be preserved by law but which is gradually decaying, were made some representations in red color in 2016 by Pisica Pătrată in order to draw attention to its destruction, within the project co-financed by the Creative Cultural Industries Association, Arcub Cultural Center, and the City Hall in the framework of the program “Bucharest, in-visible city”, and supported by the local economy and a school. The intervention aims to draw attention to the degraded built patrimony in a city which lacks renovation policies, as well to the decrease in the number of cinemas, some recently closed, representing a public danger [47]. Another example is the Capitol Cinema Garden, also an historical monument from the beginning of the 20th century, which fortunately was restored in 2021 [18], and together with it the street artwork made several years ago on the exterior metal door by Pisica Pătrată that became so a part of its history. However, the cinema room inside the building was definitely closed and a street artist from UK, J. Ace, raised an alarm signal regarding its degradation state, a cinema that, after documentation about its history, he compared to the old cinemas from New York. The artist left behind small figurines pasted on the wall of the building as a tribute to Queen Elisabeth of Romania, who gave the name of the street where the former cinema is located, but also of the architect who rebuilt the façade of the cinema in the late 1930s, Henriette Delavrancea.

Although in general it is seen like a whole phenomenon, graffiti and street art, the present study considers the street art representations more than graffiti works because they allow a clearer and more obvious highlighting of the transmitted messages in relation to culture, history and heritage. The identity of a city changes under physical, social, sensory, and memory aspects [48]. Graffiti and street art phenomenon becomes a part of the local identity as the authors are transposing in their work style their insight and/or experience about or in relation to a subject, etc., or their so-called subcultural identity [49]. Therefore, the place does not only have spatial and structural characteristics but cultural and aesthetic expressions that play an important role in the urban image and the development of identity [50]. Culture may be seen as a resource and condition for economic improvement [51]. Moreover, graffiti and street art represent a visible communication tool that gives a chance to become a significant educational or knowledge tool. In Bucharest, the messages sent through street art works are more about the national cultural identity and its connection to the international one. One explanation may be given by a shorter history of this subculture compared to what happened internationally. Street art consequently acquires a double role: directly, it changes the urban image and sometimes the functionality of some areas (it was already demonstrated that public art contributes to the processes of urban restructuring [52]) and indirectly charges or solidifies the cultural identity of a place. Additionally, like traditional art, contemporary murals need to be preserved and restored [53]. Furthermore, street art can be theorized as a heritage experience in relation to embodiment, affect, and everyday performative practice, in the sense that people construct meanings and feelings about a street artwork [54]: it is not about a dichotomy between tangible and intangible heritage or people and object, but an inseparable relationship; street artwork life may be interpreted taking into account the rapport between the physical context and community [54]. Therefore, conservation refers as well to performative and experimental approaches that use material practice to test an artwork’s potential as a heritage item and to study the interrelation between the object and the community [55]. The street art conservation requires a critical mass of people interested in its preservation, including digital mapping [56].

Following the analysis, and in order to answer more in detail to the research questions, it was stated that at the local level, street art representations are found both in non-functional or repulsive areas, related to the gray image of the socialist blocs and to a city whose socio-economic transition has left its mark on the architecture of the place, and places located in the city center in which they bring promotion, gradually becoming even more attractive and frequented, including for tourism purposes. A previous study has revealed the multidimensional importance of the street art subculture in Bucharest on economic, cultural, urban image, and perception levels [18] with the support of local authorities and different associations.

6. Conclusions

The present research highlights the place of the graffiti and street art phenomenon in the urban environments worldwide and in Bucharest as a subculture that contains cultural identity elements and diffuses local, national, and international messages. Thanks to more elaborated representations that bring it closer to art, street art conveys, in an artistical and easier form to understand, messages about cultural identity that graffiti transmits more simply and directly. The street art works contribute to the promotion of the Bucharest image and the local, national, or even international cultural heritage and, at the same time, participate in the aesthetic revitalization of the Romanian capital.

The history of graffiti from the first part of the article was considered essential to understand how the phenomenon evolved into its contemporary form. Bucharest is evolving in the same direction as other European urban areas. At a European level, it is presented as an artistic movement, encouraged in cities in a legal framework.

The limits of the study can be associated with the ephemerality of graffiti and street art works that can diminish the importance of the analyzed scientific issue. Secondly, although at first glance the subjectivity of the chosen case studies or their number may be questioned, it is considered that they are adequate to create a relevant association between local and international levels and an important foundation for the street art and cultural identity analysis in Bucharest. Third, when it comes to smaller-scale media interventions from the category of technical and municipal infrastructure, it has been proved to be more difficult to find information about the year and author, especially at an international level, despite assiduous documentation, but not to be translated as being less appreciated than other graffiti and street art representations in the urban landscape. Future research will continue to deepen the identity elements found in graffiti and street art works in Bucharest and the impact they may have on the city’s image and economy.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Glăvan, E. Murales Bolognese: Visual Representation of Italian Urban Culture. Sociol. Românească 2014, 12, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Piercy, J. Symbols: A Universal Language; Michael O’Mara Books Limited: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-78243-196-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, J.F. Trains, railroad workers and illegal riders: The subcultural world of hobo graffiti. In Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art; Ross, J.I., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 27–35. ISBN 978-1-315-76166-4. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanist. Hoboglyphs: Secret Transient Symbols and Modern Nomad Codes. Available online: https://weburbanist.com/2010/06/03/hoboglyphs-secret-transient-symbols-modern-nomad-codes/ (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Felisbret, E. Graffiti New York, 1st ed.; Harry, N., Ed.; Abrams: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0810951464. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell, J. Foreword—Graffiti, street art and the politics of complexity. In Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art; Ross, J.I., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. xxx–xxxviii. ISBN 978-1-315-76166-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dickens, L. Placing post-graffiti: The journey of the Peckham Rock. Cult. Geogr. 2008, 15, 471–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercleux, A.-L. Etică și Comunicare Interculturală cu Aplicații în Turism (Ethics and Intercultural Communication with Applications in Tourism); Universitară Press: Bucharest, Romania, 2015; ISBN 978-606-28-0312-4. [Google Scholar]

- Austin Joe, A. From the city walls to ‘Clean Trains’ Graffiti in New York City, 1969–1990. In Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art; Ross, J.I., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 223–233. ISBN 978-1-315-76166-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, H.M.; Ku, K.C.; Li, P.K.T.; Ng, H.K.; Ng, S.Y.M. Piece by piece: Understanding graffiti-writing in Hong Kong. Soc. Transform. Chin. Soc. 2016, 12, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, C. Graffiti or Street Art? Negotiating the Moral Geographies of the Creative City. J. Urban Aff. 2012, 34, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, S. Keeping it real? Subcultural graffiti, street art, heritage and authenticity. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M. The Writing on Our Walls: Finding Solutions through Distinguishing Graffiti Art from Graffiti Vandalism. J. Law Reform 1993, 26, 633–707. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell, J. Crimes of Style: Urban Graffiti and the Politics of Criminality; Northeastern University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; ISBN 9780367750169. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, N. The Graffiti Subculture: Youth, Masculinity and Identity in London and New York; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 9780333781906. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, G.J. Graffiti Lives: Beyond the Tag in New York’s Urban Underground; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 9780814740453. [Google Scholar]

- Baldini, A.L. What Is Street Art? Estet. Eur. J. Aesthet. 2022, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercleux, A.-L. Street Art Participation in Increasing Investments in the City Center of Bucharest, a Paradox or Not? Sustainability 2021, 13, 13697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warchalska-Troll, A. How to measure susceptibility to degradation in large post-socialist housing estates? Pr. Geogr. 2012, 130, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaha, E.; Ayssar Nahlé, R.; Bin Saifan, M.; Altan, H. The impact of Lighting on Vandalism in Hot Climates: The Case of the Abu Shagara Vandalised Corridor in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, C.; Colombini, M.P.; Lluveras-Tenorio, A.; La Nasa, J.; Striova, J.; Salvadori, B. Graphic vandalism: Multi-analytical evaluation of laser and chemical methods for the removal of spray paints. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 44, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, S. Why do Graffiti Writers Write on Murals? The Birth, Life, and Slow Death of Freeway Murals in Los Angeles. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2016, 40, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R.; Barbio, L.; Sequeira, Á. Urban Art in Lisbon: Emerging Opportunities and Career Aspirations. Cult. Sociol. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watzlawik, M. Cultural identity markers and identity as a whole: Some alternative solutions. Cult. Psychol. 2012, 18, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh-Hua Chen, V. Cultural Identity. In Key Concepts in Intercultural Dialogue; Center for Intercultural Dialogue: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Available online: https://centerforinterculturaldialogue.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/key-concept-cultural-identity.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Chen, Y.-W.; Mendy, M.G. Cultural Identity. In Communication; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, C.; Racovițan, A. Un-Hidden Street Art in Romania—A Short Book about the Recent Street art in Romania, 1st ed.; Save or Cancel: Bucharest, Romania, 2019; ISBN 978-973-0-30397-1. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, C.; Racovițan, A. Un-Hidden Street Art in Romania—A Short Book about the Recent Street Art in Romania, 2nd ed.; Save or Cancel: Bucharest, Romania, 2021; ISBN 978-973-0-35538-3. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, C.; Racovițan, A. Street Art—București; Save or Cancel and ARCUB: Bucharest, Romania, 2021; ISBN 978-973-0-35442-3. [Google Scholar]

- Megler, V.; Banis, D.; Chang, H. Spatial Analysis of Graffiti in San Francisco. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 54, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitas, R. Creative Cities, Graffiti and Culture-Led Development in South Africa: Dlala Indima (‘Play Your Part’). Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2020, 44, 821–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, C.P.; Sarmento, P.B. Thinking the Graffiti as a Way of Communication: Production of Meanings in the Symbolic-Identity Territory of The Street. Periferia 2019, 11, 304–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krase, J. Contested Terrains: Visualizing Glocalization in Global Cities. Open House Int. 2009, 34, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransberg, M. Performing gendered distinctions: Young women painting illicit street art and graffiti in Helsinki. J. Youth Stud. 2019, 22, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayon, F.; Cuenca, J.; Caride, J.A. Reimagining the City. Youth Leisure Practices and the Production of Public Urban Space. Obets. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2017, 12, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampoulidis, G.; Bolognesi, M.; Zlatev, J. A cognitive semiotic exploration of metaphors in greek street art. Cogn. Semiot. 2019, 12, 20192008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samutina, N.; Zaporozhets, O. Berlin, The City of Saturated Walls. Lab. Russ. Rev. Soc. Res. 2015, 7, 36–61. [Google Scholar]

- Velikonja, M. Post-Socialist Political Graffiti in the Balkans and Central Europe; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 9780367338152. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz, N. Graffiti la Feminin: Graffifi și Artă Stradală de pe Cinci Continente (Graffiti Women: Street Art from Five Continents); Hecate: București, Romania, 2015; ISBN 978-606-94047-3-7. [Google Scholar]

- Walde, C. Sticker City: Paper Graffiti Art; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0500286685. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, G. Urban Art: The World as a Canvas; Arcturus Publishing Limited: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1782120506. [Google Scholar]

- Julien de Casabianca Outings Project. Available online: https://www.outings-project.org/ (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Street Art Murals for Urban Renewal. Available online: https://urbact.eu/street-art-murals-urban-renewal (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Salcudean, I.N. Art and vandalism. CrossBreeding of street art (re)interpretation of street art from a sociological, aesthetical and interactivity perspective. J. Media Res. 2012, 5, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Crespi-Vallbona, M.; Mascarilla-Miro, O. Street art as a sustainable tool in mature tourist destinations: A case study of Barcelona. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2020, 27, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeira Mantiñán, M.J.; Durán Villa, F.R.; López Rodríguez, R. Citizen Action as a Driving Force of Change. The Meninas of Canido, Art in the Street as an Urban Dynamizer. Sustainability 2020, 12, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intervenție Pisica Pătrată pe Fațada Fostului Cinema Dacia. Available online: https://www.feeder.ro/2016/11/14/pisica-marconi/ (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- Barkat, I.; Ayad, H.; Elcherif, I. Detecting the physical aspects of local identity using a hybrid qualitative and quantitative approach: The case of Souk Al-Khawajat district. Alex. Eng. J. 2019, 58, 1339–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M. Graffiti, Aging and Subcultural Memory—A Struggle for Recognition through Podcast Narratives. Societies 2020, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogrmić, Z.; Đerčan, B. The Role of Street Art in Urban Space Recognition. Res. Rev. Dep. Geogr. Tour. Hotel. Manag. 2022, 50, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J. Cities of Cultural Heritage: Meaning, Reappropriation and Cultural Sustainability in Eastern Lisbon Riverside. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2021, 13, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, J.; Pollock, V.; Paddison, R. Just Art for a Just City: Public Art and Social Inclusion in Urban Regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1001–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzadri, P. Contemporary Murals in the Street and Urban Art Field: Critical Reflections between Preventive Conservation and Restoration of Public Art. Heritage 2021, 4, 2515–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomeikaite, L. Street art, heritage and embodiment. Str. Art Urban Creat. 2017, 3, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomeikaite, L. Street art and heritage conservation: From values to performativity. Str. Art Urban Creat. 2019, 5, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidakis, M. Street art conservation in Athens: Critical conservation in a time of crisis. Stud. Conserv. 2016, 61, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).