Abstract

The effects of intergroup dialogues on intercultural relations in digital societies and the growing conflict, inflammatory and hate speech phenomena characterizing these environments are receiving increasing attention in socio-psychological studies. Based on Allport’s contact theory, scholars have shown that online intercultural contact reduces ethnic prejudice and discrimination, although it is not yet clear when and how this occurs. By analyzing the role of the Dialogical Self in online intercultural dialogues, we aim to understand how individuals position themselves and others at three levels of inclusiveness—personal, social, and human—and how this process is associated with attitudes towards the interlocutor, intergroup bias and prejudice, whilst also considering the inclusion of the Other in the Self and ethnic/racial identity. An experimental procedure was administered via the Qualtrics platform, and data were collected among 118 undergraduate Italian students through an anonymous questionnaire. From ANOVA and moderation analysis, it emerged that the social level of inclusiveness was positively associated with ethnic/racial identity and intergroup bias. Furthermore, the human level of inclusiveness was associated with the inclusion of the Other in the Self and ethnic/racial identity, and unexpectedly, also with intergroup bias. We conclude that when people interact online as “human beings”, the positive effect of online dialogue fails, hindering the differentiation processes necessary to define one’s own and the interlocutor’s identities. We discuss the effects of intercultural dialogue in the landscape of digital societies and the relevance of our findings for theory, research and practice.

1. Introduction

Intercultural relations in digital societies, especially when characterized by phenomena such as inflammatory and hate speech, are an issue of pregnant social and political relevance. For this reason, it is urgent that psychosocial research focuses on strategies useful for reducing these negative online phenomena. Among the strategies highlighted in literature to promote positive intergroup relations, Allport’s contact theory [1] seems to be one of the most successful [2]. Since its formulation, many scholars have applied the contact theory in order to reduce prejudice towards different target groups (i.e., ethnic and sexual minorities or people with illnesses) and in different contexts (i.e., schools, workplaces). Moreover, given the difficulty involved in making people from different groups meet face-to-face, and given the growing pervasiveness of the Internet, contact theory has recently been applied to online contexts as well. Since direct face-to-face contact may be threatening and anxiety-provoking, [1,3], hosting an online interaction with an outgroup member allows not only to overcome physical barriers, [4], but also makes people feel more comfortable and in control of the situation [5]. Despite some authors, [6,7], have well underlined the efficacy of online intergroup contact in reducing prejudice, it is still not clear which variables could influence this relation. Imperato et al.’s [7] meta-analysis on this topic demonstrated that many moderation and mediation variables classically considered in the literature on offline intergroup contact could not be applied in online environments, or, when applied, fail to explain the process by which online contact reduces prejudice.

In this study, we aimed to analyze the relationship between online intercultural contact and ethnic prejudice by focusing on the role of the Self in the levels of inclusiveness—personal, social, and human—that people activate during an online intercultural dialogue. In the literature, there was a burgeoning array of different theories defining the Self. For instance, Mancini [8] distinguished modern and post-modern theories: modern Self theories generally defined the Self as located within individuals’ minds and as a propriety of individuals (i.e., the Identity Status Model [9]); while post-modern Self theories generally defined the Self located outside individuals’ minds and as a propriety of social interaction (i.e., the Dialogical Self [10]). Starting with the post-modern Self perspective, the goal of the present study was to provide a new theoretical contribution to the literature on online intergroup dialogue, by considering the intersubjective perspective proposed by the Dialogical Self Theory [10]. Moreover, by proposing an experimental design implemented online, our goal was to suggest a methodology that facilitates the collection of data on online intergroup dialogue by researchers. Lastly, considering the growing level of conflict, flaming and hate speech phenomena that characterize online environments, our practical purpose was to collect empirical evidence which would be useful not only to sensitize web users, but also to provide managers and web designers with useful ideas for designing digital societies that can favor intercultural dialogue and more generally positive contacts between people belonging to different social groups.

1.1. The Role of the Self in Prejudice Reduction

In the studies related to offline contexts, some authors, e.g., [11,12,13], have underlined the central role of the Self, seen as a variable that could partially explain the prejudice reduction. Considering the concept of social identity complexity—the relationships among individuals’ multiple memberships [14]—the literature has highlighted that individuals who perceive their multiple memberships as strongly overlapping (i.e., low social identity complexity) tend to be less inclusive and tolerant towards the outgroups, [15], increasing both explicit and implicit negative racial attitudes, [16,17], compared with individuals who perceive their multiple memberships as distinct and cross-cutting (e.g., high social identity complexity). Furthermore, studying the conflict relations between young people from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia, Brankovic et al. [13] found that the relationship between intergroup contact and prejudice reduction was partially mediated by social identity inclusiveness and complexity. Nevertheless, the literature focused on the identity processes that could mediate the relationship between intergroup contact and prejudice reduction is still lacking with regard to offline contexts and it is even scarcer with regard to online ones. White et al. [6] pointed out that the Self may be a variable key to understanding how online intergroup contact reduces prejudice. Moreover, classical literature on CMC has also focused on the identity processes that take place in online interactions. The Social Identity Model of Deindividuation Effects (SIDE) [18,19] assumed that on the one hand, the Internet provides a context in which people can develop new social identities, while also breaking down social boundaries between ingroups and outgroups, and on the other hand, an anonymous CMC increases the group’s influence, stereotyping and discriminations. Despite both the literature about online intergroup contact and the literature about CMC have underlined the importance of considering the Self, to the best of our knowledge, only a few studies to date [20,21] have considered the role of the Self in influencing the contact–prejudice relation in online contexts. In the present study, we focused on Hermans et al.’s [10] theory, which considered the Self as a product of social interactions.

The Dialogical Self, as defined by Hermans et al. [10], is multi-voiced and composed of a multiplicity of internal and external positions. Therefore, no clear boundaries divide what is typically inside the person (i.e., the Self; internal positions) and what is typically outside the person (i.e., the Other in the Self; external positions), thus what is external is considered part of the person’s identity. In other words, individuals’ identities are literally defined by the dialogue that takes place between internal positions and external positions. In line with Imperato et al. [22], studying intergroup contact in light of Dialogical Self theory enables one to make a new theoretical contribution to the literature on online intergroup contact because it redefines interaction—the ways in which contacts occur—in terms of intersubjectivity, moving from the idea that contact requires interdependent actions to the idea that contact requires interdependent positions. Therefore, the Dialogical Self enables one to analyze an intergroup phenomenon in light of Self processes, in order to empirically understand whether and to what extent the Dialogical Self explains the process by which intercultural contacts reduce ethnic/racial prejudice in online contexts.

1.2. Levels of Inclusiveness and Intergroup Contact

In studying contacts between different groups, the social identity approach highly influenced the way in which many intergroup and group-based dynamics are observed, considering both Social Identity Theory (SIT) [23,24] and Self Categorization Theory (SCT) [25,26]. These two theories allow one to better understand how individuals identify themselves and act as a group member, and since their formulation, these theories have led to a considerable amount of empirical research, e.g., [27]. Based on SCT assumptions, one could categorize themself on a personal, social or human level of inclusiveness. The levels at which individuals categorize themselves have implications for both intergroup relations as well as prejudice towards outgroups.

Some studies have shown that interaction on a personal level might favor the perception of overlap between the Self ingroup and the Other outgroup; hence, a great number of traits used to describe the Self will be attributed to the outgroup member [28]. Furthermore, this attribution will likely to lead a more positive evaluation of the Other, which, however, was not generalized to the outgroup as a whole [29]. On the other hand, Pettigrew [30] and Pettigrew and Tropp [31,32] pointed out that interpersonal processes, such as intergroup friendship—based on a personal level of inclusiveness—had a positive impact on intergroup relations. Davies and Aron [24] identified some interpersonal friendship processes that led to positive attitudes towards the outgroup: reciprocal caring, reciprocal trust, intimacy, affection, self-disclosure, inclusion of the Other in the Self and behaviors related to friendship. Through two studies, other authors [24] have found that these processes, when they occur between two members from different groups, resulted in more positive attitudes towards the outgroup as a whole, and thus the positive evaluation was generalized towards the entire group. Consequently, when summarizing these results, it emerges that when individuals interact on a personal level without developing an intergroup friendship, the positive attitude towards the outgroup member with whom they have interacted is not attributed to the outgroup as a whole, while individuals who interact with an outgroup friend tend to also extend positive attitudes to the entire outgroup.

When individuals interact categorizing themselves and others on a social level of inclusiveness, group membership become salient. As is well known, social categorization allows individuals to accentuate perceived differences between groups and similarities between members of the same group, e.g., [33], to such an extent that the mere categorization may contribute to maintaining prejudice towards the outgroup, e.g., [26]. Moreover, social categorization strengthens positive identification with one’s ingroup norms and values, which, in line with SIT, positively affects prejudice towards the outgroup [23]. Scheepers et al. [34] experimentally determined that an individual’s tendency to categorize and differentiate groups had both an identity and an instrumental function. The identity function was linked to the individuals’ need to distinguish one’s meaningful social identity from the other ones, while the instrumental function was linked to the achievement of group goals. Based on their results, the authors [34] proposed to theoretically consider both functions in interplay when analyzing people’s need for categorization, as well as the interaction at a social level of inclusiveness.

Lastly, when people categorize themselves and others based on superordinate membership, they activate the human level of inclusiveness. The literature has underlined that a more inclusive and abstract level of categorization (e.g., human identity) facilitates intergroup relations [25]. In fact, this level of categorization could be considered as a social identity shared by both the ingroup and the outgroup [35]. For instance, Levine et al. [36] experimentally induced a shift in the salience of social categorization and observed participants’ helping behaviors. The authors found that when the category boundaries were more inclusive, helping behaviors were also extended to the outgroup members, as long as they were part of a superordinate category inclusive of both ingroup and outgroup members. Furthermore, Wohl and Branscombe [37] experimentally determined that a more abstract level of human categorization increased positive responses towards the outgroup, concluding that “negative group-based feelings toward (outgroup) can be reduced with more inclusive levels of categorization” (p. 301). Thus, interaction at the human level could favor intergroup relations by including both the Self (ingroup) and the Other (outgroup) in a common, more general and abstract ingroup. In addition, this was also consistent with the common ingroup identity model [38].

1.3. Democratic Organization of the Self

Starting from SCT [25], Hermans et al. [39] recently proposed the model of the Democratic Organization of the Self, considering it as particularly useful when a dialogue takes place in a situation of conflict. It is well known that conflict phenomena such as discrimination, [21,40], hate speech, [41], and misinformation, [42], widely occur online, to the extent that it is possible to argue that the Internet could both facilitate, [43], and obstruct, e.g., [44] harmonious relations. Thus, applying the Democratic Organization of the Self model to online dialogues could be particularly useful. In this model, starting from the SCT’s three levels of inclusiveness [25], the authors focused on three different levels at which dialogue takes place, considered here as three different levels of responsibility: personal, social and human. From this perspective, the personal level of responsibility was defined as the ability to provide a dialogical answer to the Other and to oneself from a personal position (i.e., “I as an empathic person”). The social level of responsibility was defined as the ability to give a dialogical answer to the Other and to oneself from a joint social position, considering the groups to which one belongs (i.e., “I as an Italian”). Lastly, the human level of responsibility was defined as the ability to give a dialogical answer to the Other and to oneself from an inclusive and abstract human position (i.e., “I as a human being”). Since during a dialogue the individuals could move through personal, social, and human levels of inclusiveness, it was predicted that shifting towards a more abstract and inclusive level (e.g., human) could reduce conflicts. Furthermore, the ability to shift among the different levels of inclusiveness itself, i.e., the ability to re-position one’s identity in the dialogue, could foster higher harmonious interpersonal and intergroup relations. In particular, this happens in conflict situations, as theoretically pointed out by Hermans et al. [39] and experimentally explored by Imperato et al. [22].

Despite the promising premises of Hermans’ theoretical model, to date, no studies have analyzed intergroup relationships in light of the Democratic Organization of the Self model. However, we argue that applying the Democratic Organization of the Self to intergroup contacts can complexify what happens during the interactions between different groups. In addition, this helps to better understand the Self implications of the intergroup contacts, namely what people put in place in terms of Self levels of inclusiveness when they dialogue with an outgroup member.

Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, very few studies have analyzed individuals’ positionings and re-positionings in dialogue with an outgroup member. O’Sullivan-Lago and De Abreu [45] explored the impact of a cultural contact zone on identity processes in a sample of Irish nationals, immigrants and asylum seekers, arguing that re-positionings could be a strategy to maintain identity continuity when interacting with a different culture. More recently, Imperato et al. [22] analyzed data from four couples of undergraduate students of different ethnicities/cultures interacting online, finding that individuals activated different positions (i.e., different levels of inclusiveness/responsibility) based on their membership to the majority or minority ethnic/cultural group, although personal positions were the ones that were more activated during dialogue for both the majority and minority group. The authors also found that monologicity—the lack of shifts among positions during dialogue (in contrast to dialogicity)—was positively related to intergroup bias. Consequently, going beyond the specific levels of inclusiveness, the individuals’ ability to circularly shift between the personal, social, and human levels could foster less conflict in intergroup relations. Despite these findings, no study has extensively analyzed the role of the dialogue that takes place between internal positions and external positions in online intergroup contacts, and its relations with ethnic prejudice towards different ethnic/cultural groups.

1.4. The Present Study

The main aim of this study was to focus on the role of the Dialogical Self in intercultural relations occurring in online contexts. Specifically, we aimed to analyze how positioning oneself and others at three levels of inclusiveness—salience of the personal, social and human positions—and shifting from one level of inclusiveness to another during the dialogue—from monologicity to dialogicity and from coordination to incoordination—were associated with intercultural outcomes of inclusion of the Other in the Self, ethnic/racial identity, attitude toward the outgroup member with whom users dialogued, and the explicit (intergroup bias) and implicit prejudices. To this aim, an experimental study was conducted online with a sample of Italian undergraduate students who were induced to position themselves and the “Other”, i.e., a member of a cultural/ethnic outgroup, at different levels of inclusiveness/responsibility during online dialogue. These levels included the personal, the social and human levels, as indicated by the Democratic Organization of the Self, and they were experimentally manipulated through the way that the “Other” was introduced into the online dialogue and measured during the pre-dialogue and post-dialogue procedure. Based on the literature previously reviewed, we formulated four hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Given the central role of dialogism in Hermans et al.’s model [39] in fostering harmonious relations and Imperato et al.’s results [22], we expect that dialoguing with an outgroup member can favor an individual’s ability to shift between the personal, social and human levels of inclusiveness, i.e., to decrease monologicity regardless of the level of inclusiveness we manipulated. Thus, we hypothesize that online intergroup contact per se decreases the monologicity from pre-dialogue to post-dialogue, regardless of the experimental conditions, i.e., through online contact, participants’ dialogue shifts between the personal, social, and human levels of the Self’s and the Other’s positions, regardless of the experimental conditions.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

As a consequence of monologicity, we expect that dialogue with the outgroup member disfavors an individual’s ability to coordinate the Self’s and the Other’s positions. In other words, we hypothesize that online intergroup contact per se decreases the coordination of positions from pre-dialogue to post-dialogue, regardless of the experimental conditions.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

As regards the different levels of inclusiveness we manipulated (personal, social, human), we expect the salience of the Self’s and the Other’s positions to follow the level of inclusiveness we manipulated, so that participants position themselves (internal positions) and the Other (external positions) in line with the experimental conditions. Specifically, we hypothesize that participants report higher levels of individuation (i.e., greater sa-lience of internal and external personal positions; H3.1) in the personal condition; higher levels of categorization (i.e., greater salience of internal and external social positions; H3.2) in the social condition; and higher levels of humanization (i.e., greater salience of external human positions; H3.3) in the in human condition.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

In line with the findings on different levels of inclusiveness from SIT and SCT perspectives [27,28,36] and since we expect the salience of the positions to follow the level of inclusiveness we manipulated (H3), we assume some associations among dialogue monologicity, dialogue coordination and the salience of the three levels of inclusiveness in the dialogue on the one hand, and the inclusion of the Other in the Self, ethnic/racial identity, attitude toward the outgroup member, intergroup bias, and prejudices among different conditions on the other hand. More specifically, we hypothesize that monologicity is associated with negative intercultural outcomes, i.e., with a lower level of inclusion of the Other in the Self and a lower level of positive attitude towards the outgroup member, with a higher level of ethnic/racial identity, intergroup bias and prejudice. Based on the Hermans et al.’s Democratic Organization of the Self, we assume that these associations are higher in the human condition than in personal and social conditions (H4.1). As regards dialogue coordination, we expect the same associations: we assume that dialogue coordination is negatively associated with the inclusion of the Other in the Self and with the attitude towards the outgroup member, while it is positively associated with ethnic/racial identity, intergroup bias and prejudice. However, based on SIT, we assume that these associations are higher in the social condition than in personal and human conditions (H4.2). Regarding the salience of the three levels of inclusiveness during the dialogue, we hypothesize that high levels of individualization (i.e., greater salience of internal and external personal positions) positively relate to attitude towards the outgroup member. Thus, based on studies on SCT, we assume that such an association is higher in personal, medium in human and lower in social condition (H4.3). Furthermore, high levels of categorization (i.e., greater salience of internal and external social positions) positively relate to ethnic/racial identity, intergroup bias and prejudice. Nonetheless, we assume that these associations are higher in social, medium in personal and lower in human condition (H4.4). Lastly, high levels of humanization (i.e., the greater salience of internal and external human positions) positively relate to both the inclusion of the Other in the Self and ethnic/cultural identity, as well as to positive attitude towards the outgroup member, and negatively relate to intergroup bias and prejudice. Following studies at a human level of inclusiveness, we assume that these associations are higher in the human condition than in personal and social conditions (H4.5).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Procedure, and Measures

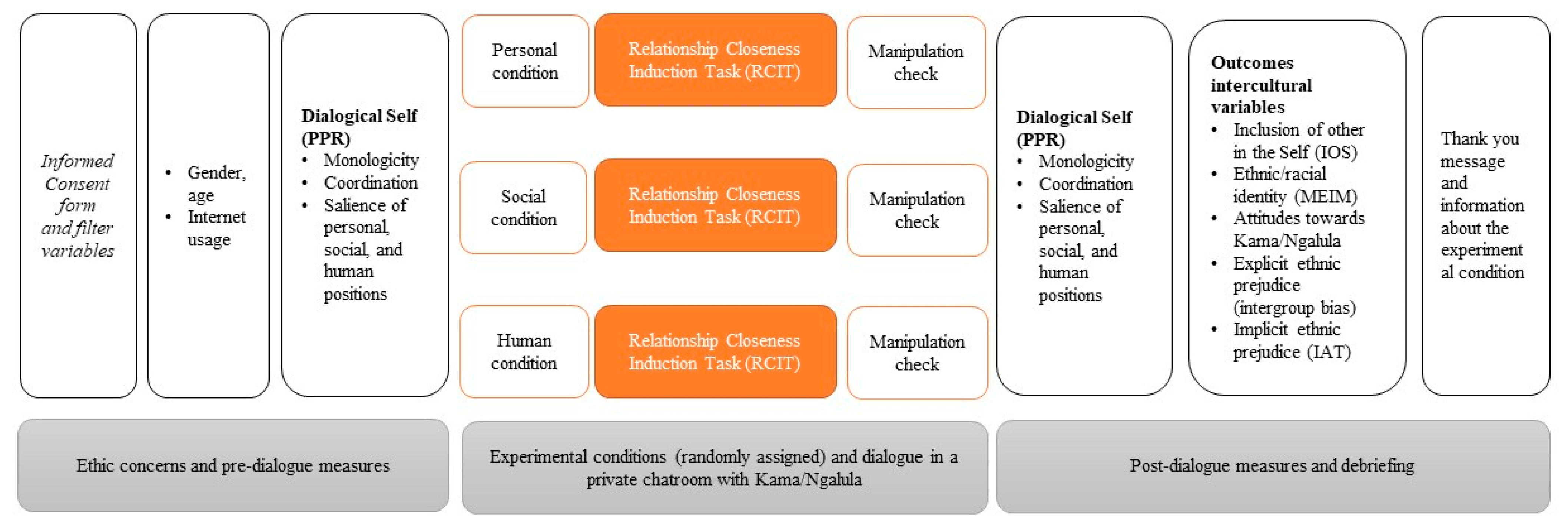

An experimental design was implemented on the Qualtrics platform. Taking advantage of the possibility of using a JavaScript code on Qualtrics, a private chatroom was programmed in which participants had to dialogue online with a fictitious outgroup member and answer a series of questions. Fictitious outgroup member’s answers were programmed based on real online intergroup dialogues provided in the study by Imperato et al. [22]. The design procedure included: an informed consent form, pre-dialogue measures, the implementation of three experimental conditions, dialogue, post-dialogue measures and debriefing. Design and measures are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Design and measures used.

2.1.1. Informed Consent Form

Complying with both GDPR and university ethical standards, and in line with the Italian Psychology Association’s (AIP) research ethics code, the first page of the questionnaire contained an informed consent form presenting information about the aim of the study and ensuring confidentiality, anonymity, and data protection. Participants were asked to give their consent to participate in the study by clicking “yes, I agree to participate” (or “no”) at the end of the informed consent form. Participants who did not give their consent were automatically redirected to the acknowledgments page. Through a filter, participants who claimed to be under 18 years old or who claimed they were not undergraduate students were led to the final “thank you” message placed at the end of the questionnaire. Furthermore, the participants had to have a keyboard to complete the Implicit Association Test measure, and those who connected through smartphones were shown a message asking them to change their device.

2.1.2. Pre-Dialogue

During the pre-dialogue phase, after some socio-demographic questions (i.e., gender, age, nationality and profession), participants were asked to complete scales related to their Internet usage and their Dialogical Self.

Internet usage. The participants were asked to complete the Internet Intensity Scale (IIS). The scale was adapted from Ellison et al.’s [46] Facebook Intensity Scale, translated into Italian and in this study adapted to refer not only to Facebook, but also to social platforms in which users can interact each other (i.e., social networks, forums and chatrooms). The scale was composed of eight items. The first two items measured online contacts and the frequency of Internet usage (e.g., “How many of your online contacts are also your friends in real life?”; “In the past week, approximately how many minutes have you spent with these people online (on social network, chat, or forum)?”). The other six items measured the intensity of Internet usage on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = completely disagree, 5 = completely agree; e.g., “Chatting online is one of my daily activities”; α = 0.80).

Dialogical Self (pre-dialogue). Participants completed a short version of Hermans’ Personal Positions Repertoire (PPR; [47]). In this pre-dialogue version, participants were asked to think about an undergraduate student similar to them and complete the PPR. The PPR was used to assess the extent to which each internal position (row) was connected to each external position (columns). The positions were adapted to the participants’ characteristics (i.e., participants’ name and ethnicity/race). In line with Hermans et al.’s Democratic Self Model [39] and with Imperato et al.’s cluster analyses findings [22], we chose the positions referring to personal, social and human levels of inclusiveness. According to Filip and Kovářová [48], despite the PPR’s remarkable flexibility, it requires a great deal of cognitive effort and time from the respondent, who must rate relationships between every internal position with every external position. Additionally, considering that the procedure took place online, therefore in a fairly ecological context without researcher control, we decided to use PPR, i.e., a short version of the sheet, including a single position for each level of inclusiveness. Specifically, the internal positions were: I as participants’ name, I as Italian, I as human being; and the external positions were: other student’s name, Senegalese, the human beings. Participants were asked to indicate on a scale ranging from 0 to 5 the extent to which each internal position was prominent in relation to each external position (0 = not at all, 5 = very considerably).

2.1.3. Experimental Conditions

Regardless of the experimental conditions, all users were told that they were about to chat online with Kama or with Ngalula, depending on the participants’ gender, a 22-year-old Senegalese undergraduate student. Then, the participants were randomly assigned to one of the three experimental conditions—personal, social, or human. We constructed the experimental manipulations based on results of Imperato et al. [22], then three experts in the field approved them. Thus, based upon the experimental condition, the interlocutor was introduced as follows:

- (a)

- Personal condition: “Kama/Ngalula really likes to chat online, especially to get to know the people he talks to in a “deep” way. Kama/Ngalula is in fact a boy/girl who is very attentive to the needs and characteristics of the people he interacts with. People who know him/her praise him/her as a friendly, open and empathetic guy/girl”.

- (b)

- Social condition: “Kama/Ngalula really enjoys chatting online, especially to meet other people who come from his own country. Kama/Ngalula is in fact a boy/girl very eager to learn about Senegalese traditions, customs, and habits. People who know him/her praise him/her as a boy/girl who is very attached to his family and his country of origin”.

- (c)

- Human condition: “Kama/Ngalula really enjoys chatting online, especially to get to know people regardless of their affiliations or diversity. Kama/Ngalula is in fact a boy/girl very desirous to know the human side of people. People who know him/her praise him/her as a boy/girl who feels himself/herself as a citizen of the world and loves justice and equality”.

2.1.4. Dialogue

With the help of a computer scientist, a private chatroom was implemented within the questionnaire in the Qualtrics platform, and participants had to chat with a “fake” outgroup member. The usage of a bot to simulate the outgroup member was widely used in the literature on online intergroup contacts. Notably, it has been shown that even contact with a fake outgroup member can reduce prejudice towards the outgroup e.g., [49]. Since establishing a cross-group friendship favors prejudice reduction, according to Davies et al. [50] and to contact literature results [31], the Relationship Closeness Induction Task [51] (RCIT) was used during the dialogue. RCIT consists of three lists of questions with a growing level of intimacy (i.e., “How old are you?” for the first list; “If you could travel anywhere in the world, where would you go and why?” for the second list; and “What is your biggest fear?” for the third list). In order to reduce participant dropout, we only asked 18 of the 29 questions from the original protocol. The questions were initially written with the aim of inducing intimacy between two unknown individuals in offline contexts, and they were recently successfully applied to the online context [52]. The RCIT questions appeared to participants who were asked to read the outgroup members’ answers and then answer to the same question. To make the dialogue as plausible as possible, the bot’s responses appeared with a slight pre-programmed latency. Furthermore, the answers were based on real dialogues that occurred between two students of different ethnicity/races that can be found in Imperato et al. [22].

Attention checks. To check that participants were attentive to the instructions of the experimental procedure, three attention checks were immediately presented after the dialogue. The questions were: “What is the name of the person you dialogue to?”; “Where did the person you dialogue with come from?”; and “Why does the person you dialogue with love to chat?”.

2.1.5. Post-Dialogue

During post-dialogue phase, the participants completed the measures of the Dialogical Self, inclusion of the Other in the Self, a measure of their ethnic/racial identity, as well as implicit and explicit ethnic prejudice measures.

Dialogical Self. The participants completed a short version of the PPR [47], which was very similar to the one presented in the pre-dialogue phase. They were asked to think about the dialogue that took place with the other student and answer the related question. Additionally, in this PPR, the internal positions were “I as participants’ name”; “I as Italian”; and “I as human being”, while external positions were the other student’s name (e.g., Kama or Ngalula, based on the participant’s gender); Senegalese; and the human beings. Participants had to indicate on a 0–5 scale the extent to which each internal position was prominent in relation to each external position.

Inclusion of the Other in the Self. It was measured through the Inclusion of the Other in the Self scale (IOS; [53]). IOS is composed of two increasingly overlapping circles. In our version, one circle represented the participant (i.e., “Me”) and the other circle represented Kama or Ngalula (i.e., “He” or “She”). Participants were asked to assess their relationship with the outgroup member with whom they interacted, selecting one out of seven couples of circles. IOS has been successfully used in studies on prejudice reduction, i.e., considering the inclusion of the Other in the Self as a mediating variable of the relationship between compassionate love and prejudice towards immigrants [54].

Ethnic/racial identity. It was measured through an Italian and cultural adaptation of the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure—Revised (MEIM-R [55]). The MEIM-R is composed of six items on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) measuring ethnic/cultural exploration and commitment (e.g., “I spent some time trying to find out more about my culture, my history, my traditions.”; α = 0.86).

Attitudes towards Kama/Ngalula. It was measured through an emotional thermometer ranging from 0 (=extremely unfavorable) to 100 (= extremely favorable) to assess the attitudes towards the outgroup member with whom participants interacted.

Explicit ethnic prejudice (intergroup bias). It was measured through two emotional thermometers ranging from 0 (= extremely unfavorable) to 100 (= extremely favorable) to assess attitudes towards the ethnic/cultural group to which the interlocutor with whom participants interacted belonged (i.e., Senegalese), and the participants’ ethnic/cultural group (i.e., Italians). An intergroup bias measure was computed by subtracting the attitude towards the outgroup (i.e., Senegalese) to the attitude towards the ingroup (i.e., Italians); thus, positive scores indicated a high preference for participants’ ingroup.

Implicit ethnic prejudice. Participants were asked to complete the Implicit Association Test (IAT; [56]) procedure. The IAT procedure was executed on the Qualtrics platform, following the guidelines suggested by Carpenter et al. [57] and published by the authors on the Open Science Framework (OSF). The IAT assessed the degree to which target pairs (e.g., Occidental people vs. non-Occidental people) and categories (e.g., pleasant vs. unpleasant) are mentally associated. We used images provided by Harvard’s Project Implicit (www.implicit.harvard.edu, accessed on 3 January 2021) to assess Occidental vs. non-Occidental target, and adjectives provided by Dasgupta et al. [58] to assess the pleasant vs. unpleasant categories. Participants completed seven blocks of stimuli sorting trials, alternating between compatible blocks (“Occidental people” + “pleasant”) and incompatible blocks (“non-Occidental people” + “unpleasant”), as well as between practice trials and critical trials. The seven blocks order was randomized among the participants presenting randomly compatible blocks or incompatible blocks first. The same procedure was used in Imperato et al. [22], showing no differences between pre- and post- dialogue; for this reason, we decided to present it only in the post-dialogue phase.

2.1.6. Debriefing

At the end of the questionnaire, participants were thanked and informed that they did not chat with a real person, and that they could contact the researcher in case they had any questions or felt upset.

2.2. Data Collection Process and Dataset Composition

A power analysis using G*Power v3.1 [59] was computed to determine the sample size. Results from Imperato et al.’s meta-analysis [7] were used to set the effect size. Thus, in order to detect an effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.39 with 80% power (alpha = 0.05), we needed 118 participants. Inclusion criteria were being university students; Italian citizenship; and users of Social Networks forums and chatrooms. The only exclusion criterion was being under 18 years old.

The participants were recruited between October 2020 and January 2021, in three stages: the first stage, from October to November 2020, involved undergraduate students from the psychology Master’s degree of the University of Parma. The experiment link was sent to the students before they were given any instruction other than those contained in the survey. The students did not receive any extra credit for their participation. In the second stage, the participants were recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk subject pool in December 2020 and in January 2021, and they received a compensation of EUR 2.50. Only those of Italian citizenship, of age (older than 18), and undergraduate students were allowed to participate. MTurk has been extensively used to recruit participants for online surveys, as the literature demonstrated that these samples reflect the general population’s characteristics, e.g., [60]. Given the lack of many Italian users on MTurk panels, we started with the third stage, recruiting participants from Prolific platform (Online participant recruitment for surveys and market research Available online: www.prolific.ac, accessed on 3 January 2021) during almost the same period in January 2021. The criteria to be eligible to participate in the study were the same as those used in MTurk recruitment, and participants received a compensation of EUR 3.00. Despite Prolific is a relatively new subject pool, the literature has highlighted its utility to distribute online questionnaires, [61].

After collecting data, we merged the three databases into a unique dataset, and we computed a recruitment stage variable to identify the participants recruited during stages 1, 2 and 3. A total sample of 207 participants opened the questionnaire and gave their consent to participate in the study (n = 99 in recruitment stage 1, n = 35 in stage 2, and n = 73 in stage 3). However, 5 were excluded because they were not Italians born in Italy, and 15 were excluded because they were not undergraduate students. In the remaining sample of 187 participants, 66 were excluded because they failed the attention checks, and 3 because of missing values for the Dialogical Self measure.

2.3. Sample Characteristics

The final sample was composed of 118 Italian participants (80 females, 67.8%; 38 males, 32.2%) aged between 18 and 35 (M = 23.58, SD = 2.79). As regards social platform use, 101 participants (85.6%) declared that they often used social networks, forums and chatrooms, while only 17 (14.4%) declared that they sometimes used the same platforms. On average, the majority of the sample (n = 99, 83.9%) declared that they had approximately 100 or less online friends who were also friends in the offline context; 18 (15.3%) declared that they had approximately 101–400 online friends; and only 1 (0.8%) declared to have more than 400 online friends. Regarding the time spent online, 23 (19.5%) spent less than an hour per week chatting, 43 (36.4%) spent approximately 5 h per week chatting, 25 (21.2%) spent approximately 15 h per week chatting, 11 (9.3%) spent approximately 20 h per week chatting, 12 (10.2%) spent approximately 30 h per week chatting, and only 4 (3.4%) spent 40 h or more per week chatting.

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis Strategy

The analysis was computed using SPSS v.27. To test the study’s hypotheses and analyze the pre- and post-dialogue PPRs, an index of monological versus dialogical dialogue was first computed. To do this, Filip and Kovářová [48,62] suggested running a principal component analysis on the external positions for each PPR sheet separately, and consider the percentage of variance explained by the first latent factor of the model as an index whose high values indicated monologicity and whose low values indicated dialogicity. However, since we used short versions of the PPR for both pre- and post-dialogue measures, it was not possible to compute PCA given the lack of variance in too many cases. Thus, inspired by this procedure, we computed a coefficient of variation for each participant, considering the ratio of the standard deviation of all nine cells of the matrix to the mean of all nine cells of the matrix. In this sense, the resulting index could be interpreted as well as the index presented by Filip and Kovářová [62]. Consequently, high levels of this index indicated high levels of monological dialogue and vice versa. Furthermore, to assess the extent to which people position themselves and the Other at the same level of inclusiveness, we computed a dialogue coordination of positions index, subtracting the values of the cells outside the diagonal (i.e., internal personal position–external social position) from the values of the cells on the diagonal (i.e., internal personal position–external personal position). As a result, high levels of this index indicated high levels of dialogue coordination. Moreover, we also computed indices of the salience of internal and external personal, social and human positions, by the arithmetic means of the cell values, as performed in Hermans et al. [47].

As regards the IAT procedure, aszccording to Greenwald, Nosek and Banaji [63], a standardized difference score within subjects (D-Score) was computed on critical trials, subtracting the mean response latency in compatible blocks by the mean response latency in incompatible blocks for both pre- and post-dialogue measures. Therefore, positive scores indicated a preference for the majority group (i.e., Occidental people), zero indicated no preferences and negative scores indicated preference for the minority group (i.e., non-Occidental people).

3.2. Descriptive Analysis

Given that the participants’ recruitment took place at different stages, we tested whether there were differences between participants recruited in stages 1, 2 and 3 in terms of participants’ characteristics and pre-dialogue design variables. Comparing all three recruitment stages, no differences were found between the second and the third stages (e.g., MTurk and Prolific recruitment stages). For this reason, we compared the first stage (e.g., undergraduate students from the University of Parma) with the second and third stages together.

The participants’ characteristics, pre-dialogue descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations are presented in Table 1. Since some of these variables were not normally distributed (i.e., monologicity and dialogue coordination), we transformed these variables by computing the square root for monologicity, and reciprocal transformation for dialogue coordination, according to the suggestions of Tabachnick and Fidell [64].

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations among pre-dialogue variables (n = 118).

Results show a small negative correlation between participants’ age and Internet usage, indicating that the younger the participants were, the more they used the Internet. As expected, all indicators of internal and external positions’ salience were related to each other, except for the relation between internal personal positions and internal human positions. As regards the two PPR indices computed, pre-dialogue monologicity was negatively related to each internal and external position’s salience. Therefore, it indicates that monologicity (square root) decreased with the salience of the Self and the Other positions, regardless of the inclusiveness level. Finally, pre-dialogue coordination (reciprocal) was positively related to internal personal and human positions’ salience, external personal, social, and human positions, and negatively associated with monologicity. Therefore, it indicates that coordination decreased with the salience of internal and external positions and increased with monologicity.

Regarding the socio-demographics and participants recruitment stage, gender was significantly related to the recruitment stage. In fact, female participants were overrepresented in recruitment stage 1. Participants in recruitment stage 1 were undergraduate psychology students, thus the difference in the percentage of males and females in the sample may be related to the higher percentage of females attending the faculty of psychology where the data were collected. Recruitment stage was significantly related to the internal personal and human, as well as external personal and social positions’ salience, as well as monologicity.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics between post-dialogue variables. Since some of these variables were not normally distributed (i.e., monologicity, dialogue coordination, intergroup bias and attitude towards the outgroup member), we transformed these variables according to the suggestions of Tabachnick and Fidell [64]. Specifically, we computed reciprocal transformation for dialogue coordination and intergroup bias variables, since the skewness was positive and greater than 2. We also computed the square root transformation for monologicity and attitude towards the outgroup member variables, since the skewness was between |1| and |2|.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations among post-dialogue variables (n = 118).

As for pre-dialogue variables, post-dialogue indicators of internal and external positions’ salience were also all positively related to each other. Furthermore, monologicity (square root) was negatively related to all positions’ salience, while dialogue coordination (reciprocal) was only significantly and negatively related to external personal positions’ salience. When it comes to the inclusion of the Other in the Self, it was positively related to internal personal and social as well as external personal and human positions’ salience. Ethnic/racial identity was positively related to internal personal and social as well as external human positions’ salience, and negatively related to monologicity. Additionally, the attitude towards the outgroup member (square root) was positively related to dialogue coordination (reciprocal) and negatively related to the inclusion of the Other in the Self. The intergroup bias (reciprocal) was negatively related to internal personal positions’ salience and ethnic/racial identity, while it was positively related to dialogue coordination; thus, it indicates that intergroup bias increased with the salience of internal positions, with ethnic/racial identity, and with dialogue coordination. Lastly, the prejudice was negatively related to the attitude towards the outgroup member, and it was positively related to ethnic/racial identity.

As for the recruitment stage, it was significantly associated with internal personal positions’ salience, ethnic/racial identity, and attitude towards the outgroup member.

3.3. Testing the Hypotheses

Since recruitment stage variables were significantly related to some design variables (see Table 2), we used the recruitment stage as a covariate when considering their interaction. Testing the hypotheses, we used the transformed indicator for variables that were not normally distributed.

To test hypotheses 1, 2 and 3, we ran repeated measures ANOVA, considering the dummy recruitment stage variable (1 = MTurk/Prolific) as a covariate, and the experimental condition as a factor. In all ANOVA models, Bonferroni adjusted confidence intervals was used.

Through the analysis of the repeated measures ANOVA results, it emerged that monologicity (square root) generally decreased in post-dialogue as we expected, but differences between pre (M = 0.76, SD = 0.24) and post-dialogue (M = 0.69, SD = 0.30) were not significant. This is also valid considering the interaction with the experimental condition and recruitment stage variable, hence not confirming hypothesis 1. As regards dialogue coordination (reciprocal), coordination generally decreased in post-dialogue as we expected, but differences between pre- (M = 1.78, SD = 0.44) and post-dialogue (M = 1.94, SD = 0.72) were not significant, although they were close to the statistical significance (p = 0.053), also interacting with the experimental condition, and hence not confirming hypothesis 2.

Furthermore, we hypothesized that individuals positioned themselves and other according to the experimental condition, considering both internal and external positions’ salience (hypothesis 3). However, no effects of experimental condition were found on the salience of either internal or external personal (H3.1), social (H3.2) and human (H3.3) positions, therefore they did not confirm hypotheses 3.

To test hypotheses 4, we performed a series of simple moderation analyses using Hayes’ PROCESS v3.5 macro for SPSS [65], adding the recruitment stage as a covariate for the variables correlated with it (i.e., internal personal positions’ salience, ethnic/racial identity and intergroup bias). Since the moderator, i.e., the given experimental conditions, was a categorical variable, we set the coding system in line with the hypotheses, thus using the indicator method to test H4.1 and H4.2, and effect method to test the remaining hypotheses [66].

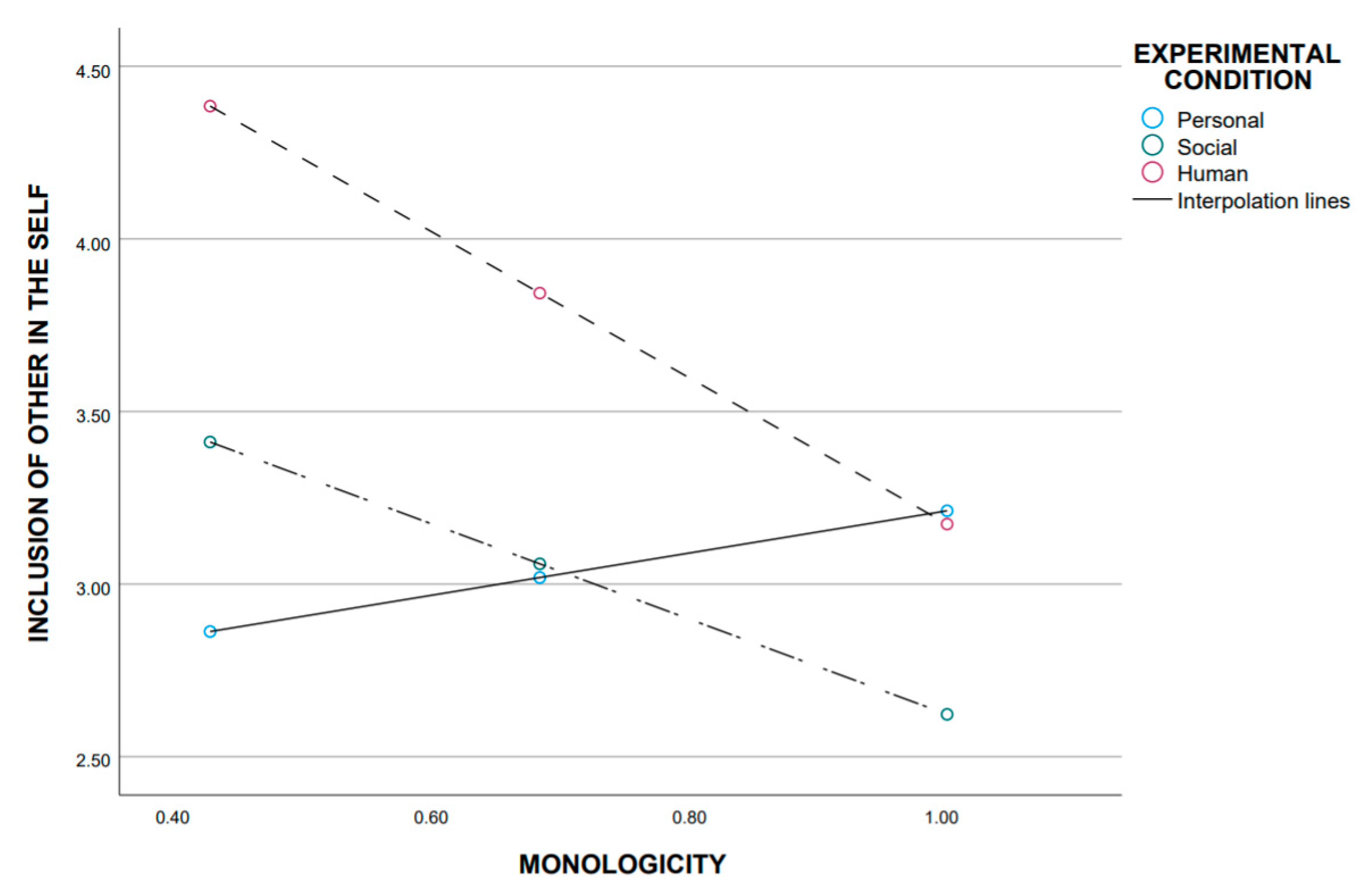

It emerged that monologicity (square root) per se (H4.1) did not significantly relate with the inclusion of the Other in the Self, while the interaction with the experimental condition was significant (β = −2.73, SE = 1.18, p = 0.02). By specifically analyzing the conditional effects, the results show that the relation between monologicity and the inclusion of the Other in the Self was negative, and it was significant only for the participants in the human condition (β = −2.11, SE = 0.91, t = −2.34, 95%CI [−3.91, −0.32], p = 0.02), thus in the expected direction (see Figure 2.)

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of the relations between monologicity (square root) and inclusion of the Other in the Self for each experimental condition. Note: experimental condition 1 = personal level of inclusiveness; experimental condition 2 = social level of inclusiveness; and experimental condition 3 = human level of inclusiveness.

No significant main or any interaction effects were found between monologicity and the attitude towards the outgroup member, ethnic/racial identity, intergroup bias, and prejudice, thus monologicity did not relate with these variables regardless of experimental condition. Therefore, our moderation analyses only partially confirmed H4.1.

As regards H4.2, the results show that the reciprocal of dialogue coordination did not significantly relate to the inclusion of the Other in the Self, attitude towards the outgroup member, ethnic/racial identity, intergroup bias and prejudice regardless of experimental conditions, therefore not confirming H4.2.

Concerning the Self and the Other personal positions’ salience, the results show that individualization (i.e., internal and external personal positions) did not significantly relate to attitudes towards the outgroup member as expected. Considering the interaction with the experimental condition, it did not confirm H4.3.

When we analyzed the Self and the Other social positions’ salience, the results show positive relations between the categorization of both internal (β = 0.14, SE = 0.04, p = 0.001) and external (β = 0.16, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001) positions and ethnic/racial identity; however, no significant interaction with the experimental condition emerged, showing that the salience of both participants’ and interlocutor’s social Self was positively associated with participants’ ethnic/racial identity, regardless of experimental conditions. Furthermore, the results show a significant interaction effect of the experimental condition on the relationship between internal social positions and intergroup bias (β = 0.07, SE = 0.03, p = 0.02): However, the conditional effects were not significant. No significant relations emerged between external social positions and intergroup bias. Lastly, no significant results were found on prejudice. Thus, our moderation analyses very partially confirmed H4.4.

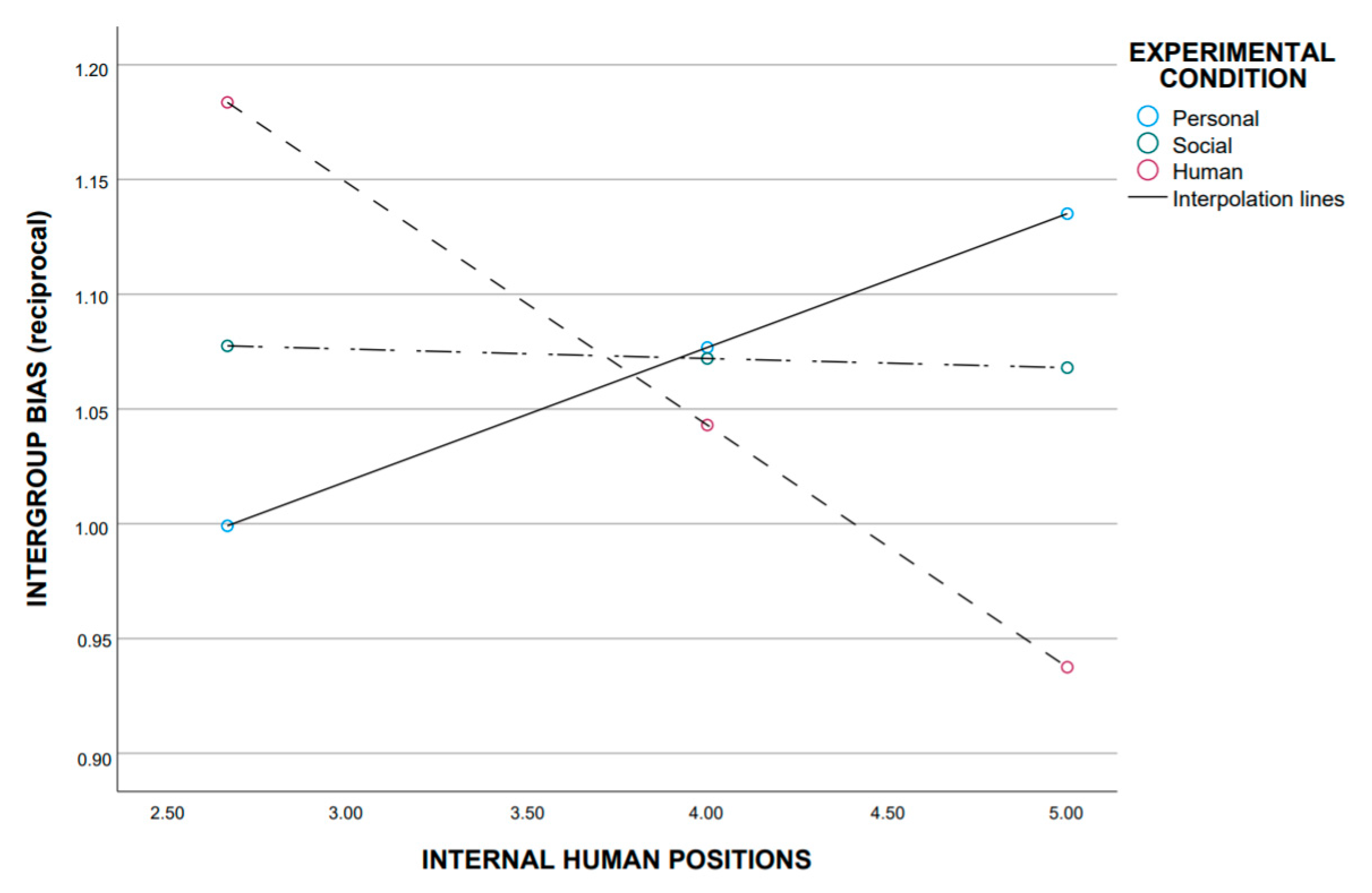

As regards humanization (the Self and the Other human positions’ salience), the results only show external and not internal human positions’ salience as positively related to the inclusion of the Other in the Self (β = 0.27, SE = 0.10, p = 0.01). At the same time, no significant interaction effect emerged, showing that the salience of the interlocutor’s human identity was positively associated with the inclusion of the Other in the Self regardless of experimental conditions. Furthermore, the results indicate only external and not internal human positions’ salience as positively related to ethnic/racial identity (β = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p = 0.03). However, no significant interaction was found, indicating that the salience of the interlocutor’s human identity was positively associated with the awareness of participants’ ethnic/racial identity, regardless of experimental conditions. No significant results were found between humanization and the attitude towards the outgroup member. Finally, as regards the relationship between internal human positions’ salience and intergroup bias, the analyses showed a significant interaction effect (reciprocal: β = −0.09, SE = 0.04, p = 0.02). Conditional effects were only significant for participants for the human condition (β = −0.11, SE = 0.05, t = −2.16, 95%CI [−0.20, −0.01], p = 0.03), in the opposite direction to what we expected (see Figure 3): in the human condition, intergroup bias increased with internal human positions’ salience, while the reverse occurred in the social condition, although not in a statistically significant way. No relations of external human positions’ salience were found. Lastly, no significant results were found on prejudice. Therefore, our mediational analyses partially confirmed H4.5.

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of the relations between internal human positions’ salience and intergroup bias (reciprocal) for each experimental condition. Note: experimental condition 1 = personal level of inclusiveness; experimental condition 2 = social level of inclusiveness; and experimental condition 3 = human level of inclusiveness.

4. Discussion

We sought to examine the Dialogical Self’s role in explaining the processes by which intergroup contact can foster harmonious relations between different ethnic groups and reduce prejudice in online contexts. The theoretical framework that guided the present investigation was found in Hermans et al.’s [39] Democratic Organization of the Self, and particularly, in the three levels of inclusiveness/responsibility identified by the authors and derived from the Self Categorization Theory [25]. We experimentally manipulated these three levels of inclusiveness (i.e., personal, social and human), and we analyzed the differences between experimental groups in terms of dialogue monologicity, dialogue coordination, salience of personal, social and human internal as well as external positions in the dialogue, as well as in terms of the inclusion of the Other in the Self, ethnic/racial identity, attitude towards the outgroup member with whom participants interacted, intergroup bias and prejudice.

We found that there were no significant differences among the experimental conditions on the salience of personal, social, and human internal and external positions. Given these results, we can conclude that the experimental manipulation was not strong enough to determine changes in the positions’ salience, and therefore we considered their relations with the outcome variables. Nevertheless, by generalizing and analyzing our results from a constructivist perspective, we can assume that the individuals strategically chose their positionings during the dialogue with the outgroup member, regardless of how the Other could be introduced to them or was perceived by them. In other words, from a constructivist perspective, it is precisely during the dialogue that people activate different levels of inclusiveness, also—and perhaps above all—based on the interlocutor’s answers, circularly. With this in mind, in our study, inducing individuals to position themselves on a specific level did not work, since the effect of the dialogue with an outgroup member itself was stronger than the experimental introduction of the outgroup member as a person, as a social category member, or as a human being. Moreover, this result’s explanation could be partially confirmed by the fact that we found relations between the salience of individualization, categorization and humanization positions and some of the outcome variables not mediated by the experimental condition. In other words, considering the positions spontaneously chosen by participants leads to different conclusions.

Furthermore, through the present study, we analyzed the extent to which online intergroup contact per se decreased the monologicity and the dialogue coordination of positions and how monologicity and coordination were related to our outcome variables. We found that monologicity only slightly and not significantly decreased from the pre- to the post-dialogue. Similarly, the dialogue coordination only slightly decreased from the pre- to post-dialogue, closely to statistical significance. This occurred regardless of the three experimental conditions, which may have at least partially confused the effect of the mere contact we expected. In fact, having introduced the partner as a person or as a human being rather than as a member of a group, i.e., Senegalese, may have, respectively, activated a lower or a greater monologicity, with the result of calming the effect of contact on monologicity. However, the less individuals shifted among the different levels of inclusiveness during the dialogue (i.e., high levels of monologicity), the less they included the Other in the Self. It must be remembered that the results show that this relationship was significant only for those in the human condition. Therefore, introducing the outgroup member as a human being facilitated the perception of a greater overlap between the Self and the Other, especially when individuals shifted among the different levels of inclusiveness/responsibility. Thus, coherently with Hermans et al.’s [39] theorization, our results confirm that both the ability to shift across different levels of inclusiveness/categorization and the ability to shift from more concrete levels of personal and social identity to the higher abstract level of human beings increased the inclusion of the Other in the Self. Some authors, e.g., [38] affirmed that individuals in the human condition considered both themselves and the interlocutor to belong to a more general and abstract ingroup. Thus, some literature results [38] showed that when individuals did not anchor their identities to one specific level of inclusiveness/responsibility, they perceived numerous similarities with the outgroup member. However, our study did not confirm these results: dialogicity and humanization, i.e., human positions’ salience, did not relate with prejudice, even if they related with the inclusion of the Other in the Self. We must not forget that according to the literature reviewed, e.g., [24,29], the greater inclusion of the Other in the Self mediates the relationship between the contact and the variables linked to the quality of intergroup relationships, e.g., [24]. Returning to our study, this could mean that to shift among positions considering the interlocutor as a human being could influence the prejudice by only including the Other in the Self. Although this interpretation is in line with other studies on online intergroup contact, e.g., [52], our results show that a lack of relation between humanization and prejudice that could also be due at least partially to the limited time of dialogue interaction.

Through the analysis of the salience of the different levels of inclusiveness/responsibility introduced by Hermans et al. [39], we also found that individuals who activated social positions during dialogue tended to strongly identify themselves as members of their ethnic/racial group, and to report high levels of intergroup bias, regardless the experimental condition. This result is in line with those of the literature based on SCT [25], and therefore allows us to confirm that categorization activates a defensive position by the outgroup, bringing people to strongly identify themselves with their ethnic/racial group and to evaluate their own group better than the other group in digital societies.

Lastly, we found that humanization (high internal and external human positions’ salience) was positively related to the inclusion of the Other in the Self. Thus, in line with both classical studies on common ingroup identity model [38] and Hermans et al. [39] insights, our results confirm that human positions can foster harmonious relations because individuals share membership to the more abstract group of human beings. For this reason, our participants perceived themselves and the member of the outgroup as partially overlapping, regardless of the experimental condition. Nevertheless, we also found that, regardless of the experimental condition, seeing the Other as a human being associated with ethnic/racial identity. Ethnic/racial identity was a precondition for the activation of an intergroup comparison process, as the interaction effect we found in the human condition between the internal human positions’ salience and ingroup bias showed. When the interlocutor was presented as a human being and internal human position was made salient, people felt the need to differentiate their ingroup (i.e., Italian) from the outgroup (i.e., Senegalese). In agreement with what SIT stated, they did so by increasing the unfavorable bias towards the outgroup. Scholars well underlined that high ingroup identification was generally an obstacle to harmonious intergroup relations, by positively affecting ethnic prejudice, e.g., [67], the perception of outgroup threat, e.g., [68], and negative emotional responses to discrimination, e.g., [69]. Therefore, the human level, though extremely abstract and literally including every person, does not always allow the individual to answer to their needs of distinctiveness [70], acting in some cases [71], including in our study, as a “threat” towards which individuals react strongly, identifying themselves with their own group and strongly preferring their own group when compared to the outgroup. When the intersubjective dimension of intergroup contact, i.e., a dialogic perspective, is taken into account, the dialogue occurring between two human beings can represent an obstacle to the the identity function of categorization [34], and individuals can react by anchoring themselves to their social memberships to protect who they think they are.

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study in which the role of the Dialogical Self in online intergroup contact was experimentally analyzed. Although the present work certainly has some limitations, its results suggest new insights for contact theory and its applications in both digital and analogical societies. Moreover, from a methodological point of view, the results of this study suggest that an experimental manipulation of the level of self-inclusiveness was not completely in line with a complex, dialogical and co-constructed conception of the Self, and we think that this is the reason why manipulation worked poorly in inducing the salience of different levels of inclusiveness. With this in mind and considering that what happens during a “dialogue” is that individuals’ positions are more relevant compared to how the interlocutor is introduced, further studies should explore the spontaneous individuals’ positionings, by extensively analyzing the singular positionings during an online and offline intergroup dialogue. Furthermore, despite the fact that this was not the first study to use a fictitious outgroup member, it is possible that the low ecological validity participants perceived reduced the magnitude of the expected effects. Further studies should analyze the sense of presence in the fictious dialogues and/or the intergroup dialogue of the Self positions in more organic online context such as social network sites and virtual worlds. Further studies should also take also into consideration that a social level of inclusiveness more abstract than social group belonging and more concrete than human group belonging, i.e., a social level of inclusiveness that explicitly includes both ingroup and outgroup members in order to understand whether and to what extent this level of abstraction affects the outcome variables. Moreover, further studies should consider other indirect measures and techniques to assess online prejudice, e.g., [72]. Despite its limitations, the present study is useful to increase the knowledge of the Dialogical Self as a variable that influences the relationship between online intergroup contact and prejudice.

5. Conclusions and Practical Implications

In psychosocial literature, the positive effect of intergroup contact in promoting harmonious relations is well known and supported by a large number of empirical findings. However, when it comes to online contexts, it is still not clear by what process online intergroup contact reduces prejudice. Through this paper, we sought to contribute to a deeper understanding of how intergroup contact affects ethnic/racial prejudice in online contexts, while taking the Dialogical Self into account. We started from the assumption that the way in which individuals in dialogue positioned themselves and others impacts users’ positions, the evaluation of the interlocutor and the evaluation of the outgroup as a whole. Overall, we showed that during online dialogues, categorization mechanisms hinder prejudice reduction, while humanization mechanisms both strengthen and hinder prejudice reduction. Specifically, we found that individuals who interacted online with an outgroup member, positioning at a social level of inclusiveness (i.e., when they activate categorization mechanisms), reported high levels of ethnic/racial identity and intergroup bias. Furthermore, individuals who dialogued online with an outgroup member, positioning at a human level of inclusiveness (i.e., when they activate humanization mechanisms), reported high levels of inclusion of the Other in the Self, ethnic/racial identity and intergroup bias. Beyond the theoretical relevance of the present work, complexifying the reflection on online hate phenomena and online discrimination, such results could be socially useful, addressing relevant issues for both online social platforms designers and Internet users. Indeed, designers could find starting points to reduce the hate speech problem in social media, to thus design social platforms in which Internet users are encouraged to explore different ways to relate with others, increasing the positive forms of intercultural dialogue. On the other hand, Internet users could be sensitized to a more functional use of online platforms, going beyond the easy path of the mere social categorization, i.e., considering themselves and the Other as both group members and human beings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.I. and T.M.; methodology, C.I. and T.M.; formal analysis, C.I.; investigation, C.I.; data curation, C.I.; writing—original draft preparation, C.I.; writing—review and editing, C.I. and T.M.; supervision, T.M.; project administration, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Since our study did not involve clinical trials on human participants, our University policy did not require us to have a formal approval for this study. However, data collected were totally anonymous, as well as processed in an aggregate manner, in compliance with Italian ethical standards, the European GPDR and the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley Pub: Cambridge, UK, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. When Groups Meet: The Dynamics of Intergroup Contact; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- White, F.A.; Borinca, I.; Vezzali, L.; Reynolds, K.J.; Lyshol, J.K.B.; Verrelli, S.; Falomir-Pichastor, J.M. Beyond Direct Contact: The Theoretical and Societal Relevance of Indirect Contact for Improving Intergroup Relations. J. Soc. Issues 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoter, E.; Shonfeld, M.; Ganayim, A. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in the Service of Multiculturalism. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2009, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amichai-Hamburger, Y.; Mckenna, K.Y.A. The Contact Hypothesis Reconsidered: Interacting via the Internet. J. Comput. Commun. 2006, 11, 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, F.A.; Harvey, L.J.; Abu-Rayya, H.M. Improving Intergroup Relations in the Internet Age: A Critical Review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2015, 19, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperato, C.; Schneider, B.H.; Caricati, L.; Amichai-Hamburger, Y.; Mancini, T. Allport Meets Internet: A Meta-Analytical Investigation of Online Intergroup Contact and Prejudice Reduction. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2021, 81, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, T. Psicologia Dell’identità; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meeus, W. Studies on Identity Development in Adolescence: An Overview of Research and Some New Data. J. Youth Adolesc. 1996, 25, 569–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, H.J.; Kempen, H.J.; Van Loon, R.J. The Dialogical Self: Beyond Individualism and Rationalism. Am. Psychol. 1992, 47, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenhausen, G.V. Diversity in the Person, Diversity in the Group: Challenges of Identity Complexity for Social Perception and Social Interaction. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 40, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuyten, M.; Martinovic, B. Social Identity Complexity and Immigrants’ Attitude Toward the Host Nation: The Intersection of Ethnic and Religious Group Identification. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branković, M.; Žeželj, I.; Turjačanin, V. How Knowing Others Makes Us More Inclusive: Social Identity Inclusiveness Mediates the Effects of Contact on out-Group Acceptance. J. Theor. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 4, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccas, S.; Brewer, M.B. Social identity complexity. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 6, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.B.; Pierce, K.P. Social Identity Complexity and Outgroup Tolerance. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, K.P.; Brewer, M.B.; Arbuckle, N.L. Social Identity Complexity: Its Correlates and Antecedents. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 2009, 12, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, K.; Hewstone, M.; Tausch, N.; Cairns, E.; Hughes, J. Antecedents and Consequences of Social Identity Complexity: Intergroup Contact, Distinctiveness Threat, and Outgroup Attitudes. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 1085–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spears, R.; Lea, M.; Postmes, T. Onside: Purview, Problems and Prospects. In SIDE Issues Centre Stage: Recent Developments in Studies of De-Individuation in Groups; KNAW: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Postmes, T.; Spears, R.; Lea, M. Computer-Mediated Communication Breaching or Building Social Boundaries? SIDE-Effects of Computer-Mediated Communication. Commun. Res. 1998, 25, 689–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, F.A.; Abu-Rayya, H.M. A Dual Identity-Electronic Contact (DIEC) Experiment Promoting Short- and Long-Term Intergroup Harmony. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, T.; Imperato, C. Can Social Networks Make Us More Sensitive to Social Discrimination? E-Contact, Identity Processes and Perception of Online Sexual Discrimination in a Sample of Facebook Users. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Imperato, C.; Mancini, T. A Constructivist Point of View on Intergroup Relations. Online Intergroup Contact, Dialogical Self and Prejudice Reduction. SUBMITTED 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C.; Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In Organizational Identity: A Reader; Oxford Management Readers: Oxford, UK, 1979; pp. 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, K.; Aron, A. Friendship Development and Intergroup Attitudes: The Role of Interpersonal and Intergroup Friendship Processes. J. Soc. Issues 2016, 72, 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Hogg, M.A.; Oakes, P.J.; Reicher, S.D.; Wetherell, M.S. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory; Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.; Judd, C.M. Rethinking the Link between Categorization and Prejudice within the Social Cognition Perspective. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 9, 108–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A.; Terry, D.J. Social Identity and Self-Categorization Processes in Organizational Contexts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenworthy, J.B.; Turner, R.N.; Hewstone, M.; Voci, A. Intergroup Contact: When Does It Work, and Why. In On the Nature of Prejudice: Fifty Years after Allport; Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Hewstone, M.; Brown, R. Contact Is Not Enough: An Intergroup Perspective on the “Contact Hypothesis”. In Contact and Conflict in Intergroup Encounters; Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F. Intergroup contact theory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1998, 49, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 751–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. How Does Intergroup Contact Reduce Prejudice? Meta-Analytic Tests of Three Mediators. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Social Categorization, Depersonalization and Group Behavior. In Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 56–85. [Google Scholar]

- Scheepers, D.; Spears, R.; Doosje, B.; Manstead, A.S.R. Integrating Identity and Instrumental Approaches to Intergroup Differentiation: Different Contexts, Different Motives. Intergr. Differ. 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.J.; Turner, J.C.; Haslam, S.A. Social Identity and Self-Categorization Theories’ Contribution to Understanding Identification, Salience and Diversity in Teams and Organizations. In Research on Managing Groups and Teams; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2003; pp. 279–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.; Prosser, A.; Evans, D.; Reicher, S. Identity and Emergency Intervention: How Social Group Membership and Inclusiveness of Group Boundaries Shape Helping Behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, M.J.A.; Branscombe, N.R. Forgiveness and Collective Guilt Assignment to Historical Perpetrator Groups Depend on Level of Social Category Inclusiveness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovidio, J.F.; Gaertner, S.L.; Anastasio, P.A.; Bachman, B.A.; Rust, M.C. The Common Ingroup Identity Model: Recategorization and the Reduction of Intergroup Bias. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, H.J.M.; Konopka, A.; Oosterwegel, A.; Zomer, P. Fields of Tension in a Boundary-Crossing World: Towards a Democratic Organization of the Self. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2017, 51, 505–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, H.; Blain, H. Tongzhi on the Move: Digital/Social Media and Placemaking Practices among Young Gay Chinese in Australia. Media Int. Aust. 2019, 173, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, N.; Alathur, S. Hate Speech Review in the Context of Online Social Networks. In Aggression and Violent Behavior; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vicario, M.; Bessi, A.; Zollo, F.; Petroni, F.; Scala, A.; Caldarelli, G.; Stanley, H.E.; Quattrociocchi, W. The Spreading of Misinformation Online. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glaser, J.; Kahn, K.B. Prejudice, Discrimination, and the Internet. In The Social Net: Understanding Human Behavior in Cyberspace; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 247–274. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, K.B.; Spencer, K.; Glaser, J. Online Prejudice and Discrimination: From Dating to Hating. In The Social Net: Understanding our Online Behavior; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 201–219. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan-Lago, R.; de Abreu, G. The Dialogical Self in a Cultural Contact Zone: Exploring the Perceived ‘Cultural Correction’ Function of Schooling. J. Commun. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 20, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C.; Lampe, C. The Benefits of Facebook “Friends:” Social Capital and College Students’ Use of Online Social Network Sites. J. Comput. Commun. 2007, 12, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hermans, H.J. The Construction of a Personal Position Repertoire: Method and Practice. Cult. Psychol. 2001, 7, 323–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]