Abstract

Background/Objectives: Propionic acidemia (PA) and methylmalonic acidemia (MMA) affect methionine, threonine, valine (Val), and isoleucine (Ile) (MTVI) metabolism, leading to the production of highly neurotoxic organic acids. Treatment involves a diet restricted in natural proteins and supplemented with a protein substitute (PS) with traces of MTVI. The aim was to analyze natural protein and PS intake in relation to linear growth impairment in individuals with PA and MMA. Methods: We followed the PRISMA protocol. We considered articles published between 1970 and 2025. We determined the eligibility criteria for selecting articles and evaluated the quality. Results: Thirteen studies were selected: two case reports, eight longitudinal, three cohorts, and one cross-sectional. Articles demonstrated that natural protein intake decreases with age, consistent with previous reports, underscoring the need for PS supplementation to meet protein requirements. Subjects with PA and non-responsive MMA had greater restriction of natural proteins, and the majority required PS; a higher PS intake was negatively correlated with a higher height-for-age (H/A) z-score. When analyzing the ratio of protein to energy (P:E), a negative correlation was found between the intake of natural proteins and energy, and a positive correlation with H/A z-score (p-value < 0.05). Supplementation with PS increased leucine levels, causing an imbalance with MTVI amino acids. This imbalance led to the paradoxical need to supplement L-Val and L-Ile, both propiogenic amino acids. As a result, a decrease in the H/A z-score was observed, particularly in PA and non-responsive MMA. Responsive MMA tolerated more natural proteins, received a lower intake of PS, and had a better H/A z-score. Conclusions: Restriction of natural proteins and PS is associated with a lower H/A z-score, primarily in subjects with PA and non-responsive MMA.

1. Introduction

Organic acidemias are caused by deficiencies of enzymes or cofactors involved in the catabolism of propiogenic amino acids such as methionine (Met), threonine (Thr), valine (Val), and isoleucine (Ile) (MTVI). Propionic Acidemia (PA) is caused by a deficiency of the propionyl-CoA carboxylase (PCC) enzyme, leading to propionic acid accumulation. Methylmalonic acidemia (MMA) is caused by a defect in the mitochondrial enzyme methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (MUT). When the enzymatic defect is complete, the condition is classified as non-responsive MMA (MUT0). In contrast, responsive MMA refers to cases in which the defect is partial, with some residual enzymatic activity (MUT-), or to cases in which the defect lies in the uptake, synthesis, or transport of the vitamin B12 cofactor (CblA, CblB, CblC). In these cases, vitamin B12 is supplemented, restoring the activity of the mutase enzyme and allowing greater tolerance of natural proteins [1,2]. All forms of MMA cause the accumulation of methylmalonic acid [1,3,4]. It is essential to mention that propionyl-CoA, a key precursor of propionic acid, is derived not only from the catabolism of amino acids (MTVI) but also from the metabolism of odd-chain fatty acids and from propionate produced by intestinal bacterial activity. The implications of these sources are significant, as they require chronic management strategies to ensure metabolic stability [1,4].

Pharmacological management in the chronic phase of PA and MMA aims to minimize the production of toxic organic metabolites, maintain metabolic stability, and support anabolism [1,4]. A key component of this approach is systematic L-carnitine supplementation, which is routinely prescribed in organic acidemias and is widely used in patients with PA (98% of centers) and non-responsive MMA (93% of centers) due to its effectiveness in releasing trapped CoA and preventing secondary carnitine deficiency. Ammonia scavenger drugs are also part of chronic management and are used by 37% of centers for PA and 16% for non-responsive MMA to address hyperammonemia [5,6]

An essential part of the treatment for PA and MMA is nutritional management, which consists of providing a protein-restricted diet that limits natural proteins, particularly those of animal origin, to reduce the intake of propiogenic amino acids [4,7]. Protein restriction does not cover the requirements established by the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) [8]; thus, a particular protein substitute (PS) for these pathologies has been developed [4,9]. The PS is an amino acid mixture that does not contain, or contains only trace amounts of MTVI, has been enriched with leucine (Leu), and has been supplemented with vitamins and minerals, allowing it to meet the RDA for age and sex [8,9,10]. The Leu is added to compete for transfer across the LAT-1 transporter into the blood–brain barrier (BBB) since it has a greater affinity and decreases the entry of MTVI into the brain [10,11]. The Leu is one of the most abundant amino acids in foods. For example, egg protein has an optimal amino acid profile for promoting anabolism, and one gram of egg protein provides approximately 100 mg of Leu. In contrast, PS used in organic acidemias provides about 158 mg of Leu per gram of protein. An imbalance in this PS’s amino acid profile can adversely affect anabolism [12].

It is important to note that Leu’s effects on hypothalamic and brainstem processes related to satiety may contribute to appetite loss in patients with PA and MMA. When exposed to excessive Leu, malnourished individuals may experience reduced growth hormone levels due to an underlying amino acid imbalance [13,14,15,16,17].

Daly and Pinto et al. surveyed within the European Society of Inborn Errors of Metabolism to quantify natural protein intake and the use of PS in subjects with PA and MMA from birth to 16 years of age. They reported that 77% of the centers met the safe protein intake recommendation established by WHO/FAO/UNU (1.0 to 2.2 g/kg/day) [8] and that 81% of the centers used a PS. They also observed that approximately 50% of the total protein requirement was derived from these PS [5,6].

A study in healthy children showed that an intake of 7104 mg of Leu per day, in the absence of Ile and Val (Leu:Ile:Val = 1:0:0), resulted in low protein synthesis. However, when Ile and Val were reintroduced (Leu:Ile:Val = 1:0.26:0.28 and 1:0.35:0.40), optimal protein synthesis was restored [18]. Other studies conducted in individuals with MMA and natural protein restriction reported a decrease in plasma Leu levels, along with reductions in the Leu:Val and Leu:Ile ratios. These changes are thought to result from competition among branched-chain amino acids, both for affinity to the LAT-1 transporter and for tissue utilization [19,20].

Considering the scientific evidence supporting the essential role of dietary treatment in maintaining metabolic stability in PA and MMA, we conducted a systematic review to assess whether restricting natural protein intake and supplementing PS impacts linear growth in individuals with these conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [21] (Supplementary Material File S1) and was registered in PROSPERO under the ID 1240154. Our research question, based on the PRISMA protocol, was defined as follows (PICOS): Population (Subjects with Propionic and Methylmalonic acidemias in growth period); intervention (protein intake); comparator (Child growth standard); outcome (z-score height per age); and study design (case reports, observational studies, clinical trials).

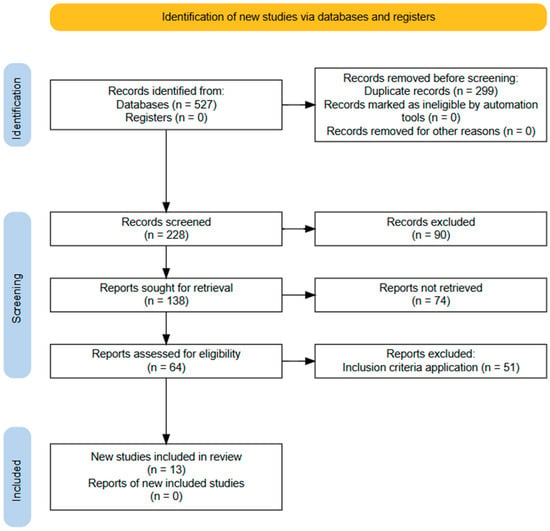

We conducted research in PubMed, Scielo, Science Direct, and EBSCO databases, considering studies published between 1970 and 2025. Our strategy for searching through the keyword combinations is found in the supplementary material (Supplementary Material File S2), and the selection process and application of exclusion criteria are summarized in Figure 1. All articles were independently reviewed by two reviewers, and a third reviewer was consulted to resolve disagreements or to determine inclusion in cases of uncertainty. The exclusion criteria were studies that included subjects with: pathologies associated with growth; renal failure in subjects with methylmalonic acidemia, other organic acidemias, or liver transplant; pharmacological treatment that could interfere with growth; or subjects who received parental nutritional therapy.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the information search and collection process in the systematic review.

To evaluate linear growth, we used the z-score height-for-age (H/A), a WHO reference that represents the distance between the subject’s height and the median for their age.

The quality of each selected article, except case reports, was assessed through the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools) (accessed on 2 February 2024). This tool evaluates 13 items and classifies the article as poor, fair, or good (Supplementary Material File S3) [22].

3. Results

Table 1 describes the relevant variables of each selected article. Those that did not accomplish the criteria were excluded (number of articles = 587) (Supplementary Material File S2).

Table 1.

Description of articles selected for the systematic review.

We identified 587 articles, and 13 studies were selected: 2 case reports [23,24], 8 longitudinal studies [25,26,29,30,31,32,33,35], and 3 cohort studies [27,28,34] (Figure 1).

Among the studies reviewed, 9 included subjects diagnosed with PA [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,35]. Similarly, 8 studies examined subjects with non-responsive MMA [23,25,26,27,30,31,34,35], 3 of which specifically included MMA CblA and CblB [25,26,27], and 1 of which included subjects with MMA CblC [28]. This detailed breakdown of the subjects’ conditions provides a clear context for the research findings.

Of the selected articles, 13 provided insights into natural protein intake [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Nine studies described the utilization of the PS for supplementation [23,25,27,28,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Four articles expressed the energy intake [25,29,32,35] and calculated the protein:energy ratio (P:E) [29,30,32,35]. Additionally, five articles highlighted the amino acid imbalance [25,27,30,33].

Eight reviewed works considered the H/A z-score as an indicator of growth when investigating ponderal growth [25,27,28,29,30,32,33,34,35].

Satoh et al. [23], in 1981, published a case report about subjects with MMA who received a natural protein intake of 0.6 to 1.2 g/kg/d, which is below the requirement established by the FAO/WHO/UNU for children under two years of age (reference value: 1.6 g/kg/d) [9] and had insufficient weight and height gain. In 1982, Queen et al. [24] reported a 34-month-old case with PA who received a protein intake of 1.0 g/kg/d and was below the 25th percentile for height.

Hauser et al. [25] reported that children (2–9 years old) and adolescents (10–18 years old) with non-responsive MMA (MUT0) received restricted natural protein and required substantial supplementation from PS. Despite this, both age groups showed suboptimal growth, as demonstrated by lower H/A z-scores, particularly in girls. Responsive MMA (CblA/CblB) presented slightly higher natural protein intakes and less dependence on PS. Overall energy intake across MMA participants was modest, and several cases required additional Val and Ile supplementation due to low plasma levels [25].

Fujisawa et al. (2013) [26], included 119 cases with MMA (non-responsive and responsive) and PA, and evaluated the natural protein intake in the acute phase (period of metabolic decompensation) and in the chronic phase (period without decompensation), observing that 88% (22/25) of the non-responsive MMA had undergone natural protein restriction in the acute phase and 93% (14/15) in the chronic phase; they reported failure to thrive in 69% of cases. However, in the acute phase, only 39% of responsive MMA required a restriction in natural proteins, 25% in the chronic phase, and only 30% of the total failed to thrive. Concerning PA, 47% had natural protein restrictions in the acute phase and 50% in the chronic phase. Failure to thrive was associated with mortality in patients with MMA [26].

Manoli et al. (2016) [27] found different results; subjects between 2 and 9 years old received a natural protein intake of 1.06 ± 0.29 g/kg/d, and 0.94 ± 0.45 g/kg/d between 10 and 18 years old. They were also supplemented with PS at 0.98 ± 0.68 g/kg/d and 0.72 ± 0.55 g/kg/d, respectively. These subjects had a H/A z-score of −2.07 ± 1.71 SD. Also, they evaluated natural protein intake in 9 subjects with CblA and reported a protein intake of 1.26 ± 0.56 g/kg/d and, among the 6 cases with CblB, an intake of 0.56 ± 0.15 g/kg/d. They found that cases with non-responsive MMA had an H/A z-score of −2.07 ± 1.71 SD, whereas responsive MMA had a z-score of −1.0 ± 1.0 SD. Furthermore, 66% of boys and 25% of girls in this group also had heights below the 10th percentile. They determined that protein intake from the PS showed a non-significant negative trend between Leu/Val and Leu/Ile intake and plasma valine concentration (r = −0.569) and between dietary intake of Leu/Val and height (r = −0.341). This association improved when serum creatinine and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) were added to the model, yielding R2 values of 0.296 and 0.478, respectively [27].

After that, Manoli et al. (2016) [28] evaluated growth in 28 subjects with MMA, considering CblC cofactor deficiency, of which 14 had congenital microcephaly and seizures, 21% (number of subjects = 6) received less than 85% of the RDA for proteins, and had a H/A z-score of −2.16 ± 1.04 SD. These results are much lower than those of the MMA subjects who received the PS, whose H/A z-score was −1.72 ± 1.01 SD. The authors noted a positive correlation between height and natural protein intake (r = 0.575) [28].

Evans et al. [29] conducted a study on 14 subjects with PA and MMA, of which 50% had an H/A z-score of −1 SD, and the other 50% between −1 and +1 SD. Natural protein intake at 3, 6, and 11 years was 1.5, 1.2, and 0.95 g/kg/d, respectively, making intake comparable with requirements according to the FAO/WHO/UNU. The study also calculated basal metabolic rate using Schofield’s predictive equation, accounting for age, sex, height, and weight. The natural protein-to-energy (P:E) ratio was expressed as grams of protein per 100 calories (kcal)/day (d), within the optimal range of 1.5–2.9 g/100 kcal/d [29].

Molema et al. (2019) [30] analyzed a longitudinal study with 263 subjects who had PA and MMA, whose H/A z-score was classified as standard at birth (−0.52 SD), and who started diet therapy for the diagnosed pathology. An average height of −2 SD was detected at the first medical check-up. Non-responsive MMA were the most compromised (−1.7 SD), despite having 105% protein adequacy according to the RDA and a P:E ratio of 1.23 (a suitable range is 0.37–3.33). They also evaluated plasma levels of MTVI amino acids. They observed that subjects who received only natural protein had lower Val levels (p < 0.001). When they received additional PS, they maintained significantly low Val and Ile levels (p < 0.001) [30].

Mobarak et al. [31] retrospectively analyzed 20 subjects with PA and MMA. In that case, they used a height percentile and observed that 65% of subjects were below the 10th percentile. They found that lower natural protein was associated with a lower height percentile. Also, they observed a positive correlation between albumin level and natural protein (r = 0.8) and a negative correlation with PS (r = 0.5) [31].

Saleeman et al. [32] evaluated 4 cases during the first five years of life; the authors reported a H/A z-score of −0.72 SD, with a 95% confidence interval of −1.36 to −0.2 SD. The same subjects evaluated between 5 and 10 years had an H/A resulting in a mean of −1.03 SD; after 10 years, the H/A z-score was −1.4 SD. It is important to note that the height of the parents and siblings of the study subjects was within normal ranges. The note indicates that one case received growth hormone treatment at age 9, which improved height. They analyzed protein and energy intake at three years of age, determining a P:E ratio of 2.75 g/100 kcal. When only natural protein intake was considered, this ratio decreased by 0.9 g/100 kcal, well below the optimal reference range (1.5–2.9 g/100 kcal) [29]. The authors concluded that low natural protein intake and a high protein intake from the PS (0.5–1.5 g/kg/day) could be negative factors for linear growth [32].

Mobarak et al. in 2021 [33] evaluated four subjects with PA and observed a total protein intake mean of 1.81 ± 0.51 g/kg/d, of which 0.79 ± 0.15 g/kg/d was natural protein and 1.02 ± 0.49 d/kg/d was PS protein. For subjects whose Val plasma concentration was below the reference range, supplementation with L-Val (180 mg/d) was indicated. Furthermore, they reported that the average intake of Leu was above the RDA (362 ± 165%) and observed a H/A z-score of −1.08 ± 0.96 SD [33].

Molema et al. (2021) [34] evaluated 76 subjects with PA and MMA. They found that 78% maintained a diet restricted in natural protein throughout follow-up and that 37% had intakes above the RDA recommendations, for which PS supplementation had been indicated in 84%. In all forms of MMA and late PA diagnosis, a negative association was found between z-score and restriction of natural proteins, except for early PA diagnosis. By associating the P:E ratio with the H/A z-score, the authors observed a more significant positive association in non-responding MMA [34].

Busiah et al. [35] in 2024 distinguished four periods: early infancy, prepubertal, pubertal, and final height. For each period, they measured each subject’s height. The average of total protein intake in early infancy was 1.1 ± 0.4 g/kg/d with H/A z-score of −0.1 SD, in the prepuberal period was 1.1 ± 0.4 g/kg/d with H/A z-score of −0.3 SD, in the puberal period was 0.8 ± 0.3 g/kg/d with H/A z-score of −1.0 SD, and the final height was H/A z-score of −0.9 SD. In early childhood patients, overall height (SD) correlated positively with the total protein/energy ratio (r = 0.215, p = 0.004), but not with IGF1, underscoring the importance of nutrition for growth [35].

4. Discussion

The first reports on treatment application were in non-responsive MMA and later in PA [23,24]. Due to nutritional restriction, formulas were manufactured with a low content of MTVI that managed to control acute metabolic decompensation. However, secondarily, a deterioration in linear growth (i.e., an H/A z-score under −1 SD) was observed. This situation is exacerbated with each acute decompensation, as the restriction of natural proteins must be increased. After all, the accumulation of organic acids derived from MTVI triggers a metabolic catastrophe characterized by hyperammonemia [36,37].

It was observed that subjects with PA and non-responsive MMA had a lower H/A z-score than those with responsive MMA, although all these groups evaluated had growth retardation observed with a low H/A, and that increased with age [25,27,29,30,32,33,35].

4.1. Protein and Energy Intake Concerning Ponderal Growth

After our analysis, selected studies showed that natural protein intake (g/kg/day) decreases with age in individuals with organic acidemias. This decline does not solely reflect the expected age-related reduction in protein requirements, as outlined in RDA/WHO/FAO guidelines. Instead, it appears to result from a combination of disease-specific metabolic considerations and clinical practice trends in which the stringency of natural protein restriction relative to body weight is maintained or even intensified as patients grow to prevent metabolic decompensation. As a result, in many cases, actual protein intake falls below age-appropriate recommendations, particularly during adolescence and adulthood, potentially contributing to suboptimal growth outcomes [27,29,35]. A European study conducted with 53 centers specialized in the follow-up of subjects with these pathologies observed that 44% and 74% had an intake of natural protein below the recommended safe level in non-responsive MMA and PAs, respectively [5,6,8]. Notably, most PA and non-responsive MMA subjects evaluated had low intake of natural proteins or were within the WHO/FAO/UNU (2007) recommended limit [4,8,9], unlike studies of responsive MMA, which showed greater tolerance to natural proteins, especially those of animal origin.

Natural protein recommendations for a safe minimum intake to maintain growth and development are established quantitatively based on total nitrogen requirements and qualitatively on the amount of essential amino acids and the protein’s digestibility [4,9,38]. The published evidence indicates that natural protein restriction reverses the clinical and biochemical symptoms in the pathologies discussed here. Various case and cohort analyses have been conducted to prevent metabolic decompensation and to avoid deterioration in linear growth caused by low intake of natural proteins [26,30,31]. Thus, it was proposed that diet therapy should be complemented with the PS formulated for these pathologies, based on amino acids, restricted in MTVI, and enriched with Leu [1,4,9]. Since the introduction of PS into long-term diet therapy, new evidence has emerged linking lower intake of natural proteins to PS supplementation and its effect on linear growth, as reflected in the H/A z-score [35,39,40]. The balance between natural protein and protein from PS is essential to decrease adverse effects on linear growth, as reflected by the H/A z-score.

From the studies included in this systematic review, we found that the PS is mainly used among non-responsive MMA and, in most cases, accounts for more than 60% of the total planned proteins [33,34]. Some authors noted that adding PS resulted in 100% of the recommended proteins across age groups being exceeded, and that the contribution of natural proteins remained low or at the limit of the established requirements [5,6,25,27,28,29,32,33]. When determining whether the contribution of natural proteins and that from the PS affected the H/A z-score, six studies observed z-scores below −1 SD, with lower z-scores among non-responsive MMA [29,30,31,32,33,35]. One author found a relationship between higher PS intake and a lower H/A z-score [33].

It should be noted that responsive MMA had a better H/A z-score than the non-responsive MMA [25,27]. That could be because this presentation tolerates more natural protein, as the cofactor’s defects depend on vitamin B12. When supplemented with megadoses of this vitamin, the activity of the mutase enzyme is restored to normal, achieving metabolic stability; hyperammonemia disappears, and the amount of methylmalonic acid is substantially lowered [1,40].

Energy intake is another highly relevant nutritional variable. Protein requirements depend on an adequate energy supply that allows for optimal tissue synthesis and compensates for nitrogen losses, thereby supporting normal growth and metabolic balance. When the diet is deficient in energy, the body uses proteins as an energy source [38,41]. An optimal protein-to-total-energy (P:E) ratio for adequate protein synthesis is 1.5 to 2.9 g/100 kcal, depending on age, body weight, sex, and physical activity [29,42,43]. Different validated equations are used in children, accounting for growth variables, basal energy expenditure, and physical activity [44]. In the studies reviewed, they used the Schofield, WHO/FAO/UNU, and Fleisch equations for subjects under 18 years of age, and the Harris-Benedict and Mifflin-St Jeor equations for subjects older than 18 years [45,46].

Among the studies reviewed, four included an analysis of the P:E ratio, and higher or optimal P:E ratios correlated with better H/A z-scores or optimal growth [29,30,32,35]. Thus, we posit that it is vital to determine the total energy contribution based on the amount of natural protein to prevent the optimal P:E ratio. It is essential to maintain a harmonious protein synthetic process and promote linear growth in diet therapy for these hereditary metabolic pathologies.

Evidence from other inherited amino acid metabolic disorders, such as phenylketonuria (PKU), also supports the notion that dietary management can influence growth trajectories. Evans et al. in 2019 reported that children with PKU frequently present with lower weight-age and H/A z-scores by [4,5] years despite apparently adequate energy and protein intakes, highlighting that dietary composition, not only total intake, may contribute to suboptimal growth [47]. Their study showed that reliance on protein substitutes during the weaning period can reduce natural protein (Phe) intake to very low levels, a factor that may affect growth patterns even when total protein intake meets recommendations. These observations from PKU studies parallel those in PA and MMA, where reduced natural protein intake and a high prescription of protein substitutes may also contribute to impaired linear growth, reinforcing the need to assess both protein quantity and amino acid profile when evaluating growth outcomes in inherited metabolic disorders.

4.2. Amino Acids Imbalance

The PS contains traces of MTVI and has been supplemented with Leu, 4–5 times the content of infant formula. Thus, bioavailability and digestibility differ from those of natural protein, which could adversely affect growth due to an imbalance in essential amino acids during this process or reduced availability for protein synthesis [10,38,48]. This generated the hypothesis that PS consumption could alter the relationship between the amino acids Leu/Val or Leu/Ile, which are essential for anabolic processes, and affect linear growth in subjects with PA and MMA [27,32,33].

A recent study in healthy subjects demonstrated that maintaining a balanced ratio of Leu:Val:Ile favors protein synthesis [18]. Three of the articles reviewed showed that subjects presented plasma with low levels of Val, Ile, and Met, leading to the paradoxical need for supplementation with L-Val and L-Ile, both propiogenic amino acids [27,29,32]. When evaluating the cause of this decrease and quantifying the intake of these amino acids, they observed that the intake of PS was the cause of the imbalance between Leu/Met, Leu/Val, and Leu/Ile, obtaining a Leu intake of 362% according to the established recommendations, and the intake of Val and Ile was 91% below the recommendations. Some studies examine whether the imbalance in these amino acids affects growth, focusing on recording their intake and measuring plasma levels. Then, they observed a negative correlation between levels of Val and Ile and linear growth in subjects with MMA, with a higher effect among non-responsive MMA. It was also observed that greater PS intake was negatively correlated with growth, with an H/A z-score of −2 SD [27,30,33]. However, among subjects with responsive MMA who tolerate greater intake of natural proteins, a better result was observed in the H/A z-score [27,28]. Thus, Leu may compete with MTVI amino acids to cross the BBB, considering that the PS has more Leu than international organizations recommend (39 mg/kg/day) [9,10,18]. One study reported a negative correlation between Met and Leu across the BBB (p < 0.001) [28]. This finding implies that excessive supplementation of Leu would compete with MTVI amino acids and directly affect the imbalance between them.

Based on our systematic review, which included 13 articles, we can conclude that restricting natural protein intake and increasing PS intake is associated with amino acid imbalance (Met, Ile, and Val). This alteration negatively correlates with the H/A z-score among subjects with PA and non-responsive MMA. Responsive MMA, because they tolerate a more significant number of natural proteins and require a lower or almost null contribution of the PS, achieve a better H/A z-score than those with the non-responsive MMA forms. These studies, along with one excluded research [49] that did not report natural protein intake, support the theory that subjects with organic acidemias have a smaller H/A than children without pathology, which is associated with a higher risk of short stature. It would be interesting to include other propiogenics substrates and their relationship with linear growth in different analyses.

The main limitations of this systematic review are the limited number of scientific publications that assess natural protein intake (particularly from animal sources, considered high-protein), PS, and linear growth in individuals with PA and MMA. The included studies were predominantly longitudinal or cohort follow-ups with small sample sizes, which inherently limit the strength of the inferences. In addition, there was substantial heterogeneity across studies in terms of study design, age ranges, clinical severity, dietary practices, and outcome measures, which limits comparability and reduces the possibility of drawing generalized conclusions. Ethical considerations make double-blind or controlled interventional studies unfeasible in life-threatening metabolic disorders such as PA and MMA, further constraining the available evidence. The cohort studies provided moderate-quality evidence, while the cross-sectional study offered fair-quality evidence. Finally, it was not possible to perform a quality assessment of the case reports due to the lack of a validated evaluation tool for this study type.

One of our exclusion criteria was to exclude studies that considered patients with PA and MMA who had undergone liver transplantation, as liver transplantation fundamentally alters protein tolerance and metabolic control. However, it is interesting to note that in four of the excluded articles [50,51,52,53], improvements in weight and height z-scores post-transplant were observed, mainly due to diet relaxation and increased natural protein intake. Gathering more information to delve deeper into this topic would be interesting.

5. Conclusions

Subjects with non-responsive MMA and PA generally showed lower natural protein intake, greater reliance on PS, and lower H/A z-scores. However, these observations are based on a limited number of studies and should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Across the available evidence, natural protein intake (g/kg/day) tended to decrease with age. At the same time, PS consumption was often high enough to result in total protein intakes exceeding RDA recommendations.

Only a few studies reported plasma concentrations of Met, Ile, and Val; therefore, conclusions regarding potential alterations in these amino acids must also be considered preliminary. Although some reports suggest that amino acid imbalances may contribute to the paradoxical need for L-Val and L-Ile supplementation, stronger and more consistent data are required to support this interpretation.

Overall, while the current evidence raises important considerations regarding dietary practices in non-responsive MMA and PA, more robust, homogeneous studies are needed before firm conclusions or clinical recommendations can be established. Nevertheless, these findings support the need for individualized dietary prescriptions that prioritize natural protein intake whenever metabolically feasible.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jpm16010004/s1, File S1: PRISMA 2020 checklist; File S2: Strategies to Articles selection; File S3: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R., M.J.L.-W. and V.C.; methodology, M.J.L.-W., J.R.; software, J.R.; validation, J.R., M.J.L.-W., J.F.C. and V.C.; formal analysis, M.J.L.-W. and V.C.; investigation, M.J.L.-W., V.C. and J.R.; resources, V.C. and M.J.L.-W.; data curation, M.J.L.-W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.L.-W., V.C. and J.R.; writing—review and editing, M.J.L.-W., J.F.C. and V.C.; visualization, J.R. and M.J.L.-W.; supervision, V.C.; project administration, M.J.L.-W.; funding acquisition, V.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Self-funded by the Laboratory of Genetics and Metabolic Diseases of INTA-University of Chile.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all the laboratory staff at the Laboratory of Genetics and Metabolic Diseases of INTA, University of Chile, for their assistance and contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| Met Thr | Methionine Threonine |

| Val | Valine |

| Ile | Isoleucine |

| Leu | Leucine |

| MTVI | Methionine, Threonine, Valine, Isoleucine |

| PA | propionic acidemia |

| MMA | methylmalonic acidemia |

| PCC | Propionyl-CoA carboxylase |

| MUT0 | Non-responsive MMA |

| MUT- | Responsive MMA |

| MMA CblA, CblB, CblC | Cofactor deficiency of the mutase enzyme |

| RDA | Recommended Dietary Allowances |

| PS | Protein substitute protein |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| LAT-1 | Transporter of large, branched, and aromatic neutral amino acids |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis |

| PICOS | The acronym is used to help formulate a well-defined research question. P: population; I: Intervention/exposure; C: comparison; O: outcome; S: Study design |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| H/A | Height per age |

| P:E | Protein energy and Energy ratio |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor-1 |

References

- Baumgartner, M.R.; Hörster, F.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Haliloglu, G.; Karall, D.; Chapman, K.A.; Huemer, M.; Hochuli, M.; Assoun, M.; Ballhausen, D.; et al. Proposed Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Methylmalonic and Propionic Acidemia. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2014, 9, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyfi, F.; Talebi, S.; Varasteh, A.-R. Methylmalonic Acidemia Diagnosis by Laboratory Methods. Rep. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, R.J.; Venditti, C.P. Gene Therapy for Methylmalonic Acidemia: Past, Present, and Future. Hum. Gene Ther. 2019, 30, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forny, P.; Hörster, F.; Ballhausen, D.; Chakrapani, A.; Chapman, K.A.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Dixon, M.; Grünert, S.C.; Grunewald, S.; Haliloglu, G.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of methylmalonic acidaemia and propionic acidaemia: First revision. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2021, 44, 566–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, A.; Pinto, A.; Evans, S.; Almeida, M.F.; Assoun, M.; Belanger-Quintana, A.; Bernabei, S.M.; Bollhalder, S.; Cassiman, D.; Champion, H.; et al. Dietary practices in propionic acidemia: A European survey. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2017, 13, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, A.; Evans, S.; Daly, A.; Almeida, M.F.; Assoun, M.; Belanger-Quintana, A.; Bernabei, S.M.; Bollhalder, S.; Cassiman, D.; Champion, H.; et al. Dietary practices in methylmalonic acidaemia: A European survey. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 33, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurecki, E.; Ueda, K.; Frazier, D.; Rohr, F.; Thompson, A.; Hussa, C.; Obernolte, L.; Reineking, B.; Roberts, A.M.; Yannicelli, S.; et al. Nutrition management guideline for propionic acidemia: An evidence- and consensus-based approach. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 126, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint FAO; WHO; UNU Expert Consultation on Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization; United Nations University. Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43411 (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- U.S. Food and Drugs Administration (FDA). Medical Foods Guidance Documents & Regulatory Information. 2022 [Accessed 7 December 2022]. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/guidance-documents-regulatory-information-topic-food-and-dietary-supplements/medical-foods-guidance-documents-regulatory-information (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Myles, J.G.; Manoli, I.; Venditti, C.P. Effects of medical food leucine content in the management of methylmalonic and propionic acidemias. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2018, 21, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.A.; Joshi, M.; Jeoung, N.H.; Obayashi, M. Overview of the Molecular and Biochemical Basis of Branched-Chain Amino Acid Catabolism. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 1527S–1530S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, L.E.; Burns, C.; Drumm, M.; Gaughan, S.; Sailer, M.; Baker, P.R., II. Impact on Isoleucine and Valine Supplementation When Decreasing Use of Medical Food in the Nutritional Management of Methylmalonic Acidemia. Nutrients 2020, 12, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, J.W.; Badaloo, A.; Wilson, L.; Taylor-Bryan, C.; Chambers, B.; Reid, M.; Forrester, T.; Jahoor, F. Dietary Supplementation with Aromatic Amino Acids Increases Protein Synthesis in Children with Severe Acute Malnutrition1–4. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manary, M.J.; Yarasheski, K.E.; Berger, R.; Abrams, E.T.; Hart, C.A.; Broadhead, R.L. Whole-Body Leucine Kinetics and the Acute Phase Response during Acute Infection in Marasmic Malawian Children. Pediatr. Res. 2004, 55, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.A.; Suryawan, A.; Orellana, R.A.; Gazzaneo, M.C.; Nguyen, H.V.; Davis, T.A. Differential effects of long-term leucine infusion on tissue protein synthesis in neonatal pigs. Amino Acids 2011, 40, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cota, D.; Proulx, K.; Smith, K.A.B.; Kozma, S.C.; Thomas, G.; Woods, S.C.; Seeley, R.J. Hypothalamic mTOR Signaling Regulates Food Intake. Science 2006, 312, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, F.; Guo, Q.; Duan, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yin, Y. Leucine Supplementation: A Novel Strategy for Modulating Lipid Metabolism and Energy Homeostasis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleemani, H.; Horvath, G.; Stockler-Ipsiroglu, S.; Elango, R. Determining ideal balance among branched-chain amino acids in medical formula for Propionic Acidemia: A proof of concept study in healthy children. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2022, 135, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, H.B. Nutricion. In Fisiología Humana; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. 987. [Google Scholar]

- Nyhan, W.L.; Borden, M.; Childs, B. Idiopathic hyperglycinemia: A new disorder of amino acid metabolism. II. The concentrations of other amino acids in the plasma and their modification by the administration of leucine. Pediatrics 1961, 27, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHLBI. Study Quality Assessment Tools. 2021. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Satoh, T.; Narisawa, K.; Igarashi, Y.; Saitoh, T.; Hayasaka, K.; Ichinohazama, Y.; Onodera, H.; Tada, K.; Oohara, K. Dietary therapy in two patients with vitamin B12-unresponsive methylmalonic acidemia. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1981, 135, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queen, P.M.; Acosta, P.B.; Fernhoff, P.M. The effects of spacing protein intake on nitrogen balance and plasma amino acids in a child with propionic acidemia. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1982, 1, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, N.S.; Manoli, I.; Graf, J.C.; Sloan, J.; Venditti, C.P. Variable dietary management of methylmalonic acidemia: Metabolic and energetic correlations. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujisawa, D.; Nakamura, K.; Mitsubuchi, H.; Ohura, T.; Shigematsu, Y.; Yorifuji, T.; Kasahara, M.; Horikawa, R.; Endo, F. Clinical features and management of organic acidemias in Japan. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 58, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoli, I.; Myles, J.G.; Sloan, J.L.; Shchelochkov, O.A.; Venditti, C.P. A critical reappraisal of dietary practices in methylmalonic acidemia raises concerns about the safety of medical foods. Part 1: Isolated methylmalonic acidemias. Genet. Med. 2016, 18, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoli, I.; Myles, J.G.; Sloan, J.L.; Carrillo-Carrasco, N.; Morava, E.; Strauss, K.A.; Morton, H.; Venditti, C.P. A critical reappraisal of dietary practices in methylmalonic acidemia raises concerns about the safety of medical foods. Part 2: Cobalamin C deficiency. Genet. Med. 2016, 18, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Truby, H.; Boneh, A. The Relationship between Dietary Intake, Growth, and Body Composition in Inborn Errors of Intermediary Protein Metabolism. J. Pediatr. 2017, 188, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molema, F.; Gleich, F.; Burgard, P.; van der Ploeg, A.T.; Summar, M.L.; Chapman, K.A.; Lund, A.M.; Rizopoulos, D.; Kölker, S.; Williams, M.; et al. Decreased plasma l-arginine levels in organic acidurias (MMA and PA) and decreased plasma branched-chain amino acid levels in urea cycle disorders as a potential cause of growth retardation: Options for treatment. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 126, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobarak, A.; Dawoud, H.; Nofal, H.; Zoair, A. Clinical Course and Nutritional Management of Propionic and Methylmalonic Acidemias. J. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 2020, 8489707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleemani, H.; Egri, C.; Horvath, G.; Stockler-Ipsiroglu, S.; Elango, R. Dietary management and growth outcomes in children with propionic acidemia: A natural history study. JIMD Rep. 2021, 61, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobarak, A.; Stockler, S.; Salvarinova, R.; Van Karnebeek, C.; Horvath, G. Long term follow-up of the dietary intake in propionic acidemia. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2021, 27, 100757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molema, F.; Haijes, H.A.; Janssen, M.C.; Bosch, A.M.; van Spronsen, F.J.; Mulder, M.F.; Verhoeven-Duif, N.M.; Jans, J.J.M.; van der Ploeg, A.T.; Wagenmakers, M.A.; et al. High protein prescription in methylmalonic and propionic acidemia patients and its negative association with long-term outcome. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3622–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busiah, K.; Roda, C.; Crosnier, A.-S.; Brassier, A.; Servais, A.; Wicker, C.; Dubois, S.; Assoun, M.; Belloche, C.; Ottolenghi, C.; et al. Pubertal origin of growth retardation in inborn errors of protein metabolism: A longitudinal cohort study. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2024, 141, 108123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häberle, J.; Chakrapani, A.; Ah Mew, N.; Longo, N. Hyperammonaemia in classic organic acidaemias: A review of the literature and two case histories. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, K.A.; Ah Mew, N.; Mickle, N.; Starin, D.; MacLeod, E. Propionic acidemia and methylmalonic aciduria: A portrait of the first 3 years—Admissions and complications. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2025, 146, 109289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, C.; Tomé, D. Dietary Protein and Nitrogen Utilization. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1868S–1873S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannicelli, S. Nutrition therapy of organic acidaemias with amino acid-based formulas: Emphasis on methylmalonic and propionic acidaemia. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2006, 29, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, V.; Raimann, E.; Pérez, B.; Desviat, L.; Arias, C. Errores innatos del metabolismo de los aminoácidos. In Errores Innatos en el Metabolismo del Niño, 4th ed.; Universitaria: Santiago, Chile, 2017; pp. 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; WHO; UNU. Human Energy Requirements. 2004. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/y5686e/y5686e00.HTM (accessed on 2 June 2013).

- Millward, D.J.; Jackson, A.A. Protein/energy ratios of current diets in developed and developing countries compared with a safe protein/energy ratio: Implications for recommended protein and amino acid intakes. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Mejía, L.A.; Fernández-Lainez, C.; Vela-Amieva, M.; Ibarra-González, I.; Guillén-López, S. The BMI Z-Score and Protein Energy Ratio in Early- and Late-Diagnosed PKU Patients from a Single Reference Center in Mexico. Nutrients 2023, 15, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, V.; Cruchet, S. Recomendaciones y requerimiento de micro y macronutrientes. In Nutrición en el Ciclo Vital; Santiago, Chile, 2013; pp. 17–39. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog/101627301 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Harris, J.A.; Benedict, F.G. A Biometric Study of Human Basal Metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1918, 4, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mifflin, M.D.; St Jeor, S.T.; Hill, L.A.; Scott, B.J.; Daugherty, S.A.; Koh, Y.O. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990, 51, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.; Daly, A.; Wildgoose, J.; Cochrane, B.; Chahal, S.; Ashmore, C.; Loveridge, N.; MacDonald, A. Growth, Protein and Energy Intake in Children with PKU Taking a Weaning Protein Substitute in the First Two Years of Life: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmelcman, S.; Guggenheim, K. Interference between leucine, isoleucine and valine during intestinal absorption. Biochem. J. 1966, 100, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robredo García, I.; Grattarola, P.; Correcher Medina, P.; Abu-Sharif Bohigas, F.; Vélez García, V.; Vitoria Miñana, I.; Martínez Costa, C. Nutritional status in patients with protein metabolism disorders. Case-control study. An. Pediatría Engl. Ed. 2024, 101, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorifuji, T.; Muroi, J.; Uematsu, A.; Nakahata, T.; Egawa, H.; Tanaka, K. Living-related liver transplantation for neonatal-onset propionic acidemia. J. Pediatr. 2000, 137, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morioka, D.; Kasahara, M.; Horikawa, R.; Yokoyama, S.; Fukuda, A.; Nakagawa, A. Efficacy of Living Donor Liver Transplantation for Patients with Methylmalonic Acidemia. Am. J. Transplant. 2007, 7, 2782–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, R.; Nakamura, K.; Kido, J.; Matsumoto, S.; Mitsubuchi, H.; Inomata, Y.; Endo, F. Improvement in the prognosis and development of patients with methylmalonic acidemia after living donor liver transplant. Pediatr. Transplant. 2016, 20, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, N.R.; Stroup, B.M.; Poliner, A.; Rossetti, L.; Rawls, B.; Shayota, B.J.; Soler-Alfonso, C.; Tunuguntala, H.P.; Goss, J.; Craigen, W.; et al. Liver transplantation in propionic and methylmalonic acidemia: A single center study with literature review. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 128, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.