Abstract

Background/Objectives: As precision medicine advances, attention to sex and gender determinants across epidemiological and clinical domains has intensified. However, in the audio-vestibular field, knowledge on sex- and gender-related aspects remains relatively limited. The main aim of this review has been to analyze the available gender medicine-based evidence in vestibular disorders. In particular, our investigation considered the following: (i) pathophysiology and clinical presentation, including differences in predominant signs and symptoms, diagnostic modalities and findings, underlying biological mechanisms associated with vestibular disorders across sex-specific groups; (ii) prognostic variables, including response to treatment, recovery rates, and long-term functional outcomes; (iii) the potential role of sex- and gender-specific diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in the management of vestibular disorders. Methods: Our protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42025641292). A literature search was conducted screening PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science databases. After removal of duplicates and implementation of our inclusion/exclusion criteria, 67 included studies were identified and analyzed. Results: Several studies reported a higher incidence of vestibular dysfunctions among females, with proposed associations involving hormonal fluctuations, calcium metabolism and vitamin D. Estrogen receptors within the inner ear and their regulatory effects on calcium homeostasis have been proposed as potential mechanisms underlying these sex-specific differences. Furthermore, lifestyle factors, comorbidities and differential health-seeking behaviors between males and females may also modulate disease expression and clinical course. Conclusions: Gender-specific variables could not be independently analyzed because none of the included studies systematically reported gender-related data, representing a limitation of the available evidence. Current evidence suggests the presence of sex-related differences in the epidemiology and clinical expression of vestibular disorders, but substantial gaps remain regarding mechanisms, outcomes, and clinical implications. Future research should prioritize prospective, adequately powered studies specifically designed to assess sex and gender influences, integrating biological, psychosocial, and patient-reported outcomes, and adopting standardized sex- and gender-sensitive reporting frameworks.

1. Introduction

The emerging interest in precision medicine approaches has led to an increasing attention on differences in prevalence and clinical presentation with respect to gender and biological sex [1]. In several clinical fields, the limited availability of sex and gender-balanced evidence has made research on this topic particularly compelling. In clinical conditions in which a strong male or female prevalence exists, the skewed distribution of cases has often led to disregarding possible clinical differences in patients from the less prevalent gender [2].

In the scientific literature, the terms sex and gender have been distinctly employed to point to different concepts. While sex refers to the biological attributes (such as genetic composition, endocrine profiles, tissue-specific responses, and reproductive anatomy) which typically classify individuals as female or male, gender encompasses the social and cultural constructs that shape roles, identities, behaviors, and relations within a given society [3]. As a result, sex-based differences often underlie fundamental biological mechanisms, while gender-based differences may influence health-seeking behaviors, treatment adherence, and access to care [4].

In response to this, gender medicine, a form of precision medicine, has emerged as a novel clinical paradigm, allowing for a more comprehensive evaluation of the influence of sex and gender on many conditions in terms of risk factors, prognosis, clinical signs, pathophysiology, epidemiology, and therapy [5]. Despite these advances, knowledge of sex- and gender-related aspects in the audio-vestibular field remains relatively limited [6]. Although the information is rather heterogeneous, an overall female epidemiological prevalence in vestibular disorders has been reported for many conditions [7,8]. The recognition of such differences is crucial to the development of tailored treatment approaches for vestibular disorders.

The main aim of this systematic review was to collect and analyze the available sex and gender evidence in vestibular disorders. In particular, the investigation has considered: (i) pathophysiology and clinical presentation, including differences in signs and symptoms, diagnostic findings, and underlying biological mechanisms; (ii) prognostic variables, including response to treatment, recovery rates, and long-term functional outcomes; (iii) the potential role of sex- and gender-specific therapeutic approaches in the management of vestibular disorders.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

The protocol of this review was registered on PROSPERO, an international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews in health and social care (Center for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York, UK) on 19 February 2025 (registry number CRD42025641292).

2.2. Definitions

For the purposes of this review, ‘sex’ was defined as a biological attribute in accordance with Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) Guidelines [9]. ‘Gender’, defined as a sociocultural identity, was not independently studied as gender data were not consistently reported in the vestibular literature. However, the term ‘gender’ was used in our search query to capture articles that may have used sex- and gender-related terminology interchangeably or with alternative definitions.

2.3. Search Strategy

A systematic literature review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations [10]. (see Supplementary Materials, too). The electronic databases Scopus, PubMed and Web of Science were searched, considering a time frame from 2000 to 2025, according to the following keywords: “gender medicine” OR (gender OR sex) AND (distribution OR difference) AND (vertigo OR benign paroxysmal positional vertigo OR vestibular migraine OR vestibular neuritis OR Ménière’s disease). The reference lists of all the included articles were screened for further relevant studies.

After duplicates removal, 3 reviewers (GB, AV, MT) independently screened all titles and abstracts and then evaluated the full texts of the eligible articles based on the inclusion criteria. Any disagreement between these reviewers was resolved through discussion with all authors to reach a consensus.

2.4. Selection Criteria, Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The retrieved articles were included in the systematic review based on the following inclusion criteria: (i) original reports (including prospective or retrospective studies, with or without control groups); (ii) availability of epidemiological, clinical, or outcomes data with respect to sex or gender; (iii) English publication language. The exclusion criteria were: (i) lack of relevant data; (ii) non-original studies (i.e., reviews, recommendations, letters, editorials); (iii) publication date earlier than 1 January 2000; (iv) case reports and small case series (fewer than 10 subjects), in order to reduce small-sample bias and improve the interpretability of sex-stratified analyses.

Once the included studies were defined, the extracted data together with study characteristics were collected in an electronic database. Furthermore, the quality of the studies eligible for inclusion was independently assessed by three reviewers (GB, AV, MT) and categorized as Poor, Fair, and Good, in agreement with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) quality assessment tool for Observational Cohorts and Cross-Sectional Studies (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools, accessed on 20 July 2025). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus through discussion.

2.5. Qualitative and Quantitative Synthesis

The included investigations were qualitatively synthetized. Quantitative synthesis was not feasible for other domains, including diagnostic findings, treatment response, and prognostic outcomes, due to heterogeneity in outcome definitions, measurement tools, and reporting formats, as well as the frequent absence of sex-stratified data. Because cohorts and settings were expected to vary, we prespecified a random-effects model using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) to estimate the pooled mean difference and between-study variance (τ2). In view of the anticipated heterogeneity, any quantitative synthesis was considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory. Statistical heterogeneity was quantified with Cochran’s Q, I2 and H2. Two-sided α = 0.05 was used for significance testing. Analyses were conducted with the Meta suite of STATA 16.1 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Search Results, Quality Assessment and Study Design

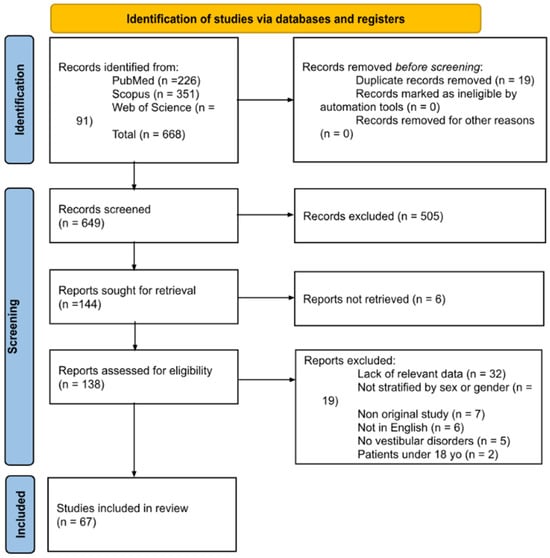

A total of 668 papers were retrieved from the literature search. After duplicate removal, records were screened, full-text reports were assessed for eligibility, and 67 studies were included in the review (Figure 1). A list of full-text articles assessed for eligibility but excluded, with reasons, is provided in Supplementary Material S1 in accordance with PRISMA 2020.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram summarizing Electronic Database Search and Inclusion/Exclusion process of the review (date of last search 17 February 2025).

The 67 included studies were analyzed for design, quality, population, vestibular disorder type, outcomes and main conclusions [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77]. A total of eleven studies were prospective cohort studies [13,16,22,27,33,41,42,52,53,67,72]. Thirty articles employed a retrospective cohort design [12,20,21,25,26,31,32,37,40,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,55,56,58,60,61,63,64,66,69,70,74,75,76,77]. Three studies used a case–control design [27,59,71]. In addition, ten papers were cross-sectional studies [14,17,18,23,26,38,62,65,68,73]. One study was a randomized controlled trial [24], two were non-randomized controlled trials [19,51], and one was a non-controlled clinical trial [29]. Finally, eight papers were population-based studies [11,17,34,35,36,43,44,57]. Twenty-two out of 67 considered a multicentric setting [11,13,17,18,21,34,35,36,38,39,40,41,43,44,48,55,56,57,61,68,73,76]. In agreement with the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the quality assessment analysis reported good quality for 27 papers, fair quality for 38 papers, poor quality for 2 papers (Supplementary Material S1).

Eleven articles included in this review explicitly aimed to highlight potential sex differences in the considered series [13,19,30,34,42,46,47,49,63,72,74]. Among the 67 studies included in this review, 53 studies [11,12,13,14,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] reported significant sex-related differences regarding epidemiology, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, risk factors, comorbidities and clinical presentation. Conversely, 14 studies [15,20,22,24,27,29,50,54,59,65,66,69,70,74] did not report significant differences. None of the studies included in the review explicitly applied or referenced the SAGER guidelines [78].

3.2. Population, Epidemiology and Demographic Characteristics

All of the included articles reported a stratification of demographics and/or clinical characteristics by sex. In 9 studies, the exact vestibular diagnosis was not available [13,14,26,38,43,45,57,65,69], while the remaining 58 reported data about the vestibular conditions affecting their populations. Specifically, 34 included cases of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) [11,12,13,15,16,17,18,20,21,22,24,25,27,29,30,32,34,35,36,37,38,42,46,47,48,49,50,52,53,59,62,63,66,70,71,72,73,75,76], 25 Ménière’s disease (MD) [11,12,16,17,19,25,26,33,34,35,36,37,38,40,42,48,55,56,60,61,62,70,71,73,76], 5 vestibular migraine (VM) [26,28,37,40,62], 11 vestibular neuritis (VN) [34,35,36,37,40,60,61,70,71,72,73,75,76], and 5 persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD) [15,20,31,37,77]. Most of these studies included cases of more than one vestibular condition.

Table 1 reports the 18 studies investigating the epidemiology and demographic characteristics of vestibular disorders with possible sex-specific differences [15,17,34,35,36,37,38,43,55,56,60,61,63,65,67,68,73,74,75].

Table 1.

Studies focusing on the epidemiology and demographic characteristics of vestibular disorder.

3.3. Diagnostic Approaches, Therapeutic Interventions and Outcomes

As shown in Table 2, sex-related differences in diagnostic approaches for vestibular disorders were investigated by six studies [11,23,33,50,54,72]. Four studies [11,23,33,72] reported significant differences between male and female patients, whereas two [50,54] did not.

Table 2.

Diagnostic approaches and findings in vestibular disorders.

As summarized in Table 3, nine studies investigated treatment strategies for vestibular disorders [19,24,27,28,29,40,51,53,58]. Six studies [19,28,40,51,53,58] reported significant differences between female and male patients, whereas three [24,27,29] did not report any significant differences.

Table 3.

Therapeutic interventions.

As illustrated in Table 4, 34 studies investigated sex-related differences [12,13,14,16,18,20,21,22,25,26,30,31,32,36,39,41,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,52,57,59,62,64,66,69,70,71,76,77]. Among them, 28 studies [12,13,14,16,18,21,25,26,30,31,32,36,39,41,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,52,57,62,64,71,76,77] reported significant differences between males and females, while six studies [20,22,59,66,69,70] found no significant differences.

Table 4.

Symptoms, comorbidities, prognosis and quality of life outcomes.

3.4. Exploratory Quantitative Synthesis

Among the assessed domains, only dizziness-related quality of life measured using the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) was reported in a sufficiently homogeneous and sex-stratified manner to allow quantitative synthesis. Fourteen articles [15,18,24,28,29,31,41,45,50,51,52,53,69,77] included in this review used the DHI to assess patients’ quality of life. Two of those [52,53] did not report DHI scores; one [28] reported only the difference in DHI scores between study groups; and seven [15,24,31,41,50,69,77] did not stratify DHI values by sex or gender. Four studies [18,29,45,51], including a total of 323 female and 140 male participants with vestibular disorders (PC-BPPV, unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction, long-COVID dizziness), reported DHI details and were eligible for an exploratory quantitative synthesis. As represented in Supplementary Material S1, the pooled analysis revealed a negligible overall mean difference of −0.13 points (95% CI −8.00 to 7.75; z = −0.03; p = 0.97), indicating no consistent sex-related difference in perceived dizziness handicap across studies. However, between-study heterogeneity was substantial (τ2 = 53.77; I2 = 92.2%; H2 = 12.82), with a significant Q test (Q(3) = 20.87; p < 0.001), limiting the interpretability of the pooled estimate.

4. Discussion

Vestibular disorders may exhibit sex-specific variations due to differences in hormonal regulation, inner ear anatomy and neurophysiological processing between males and females [78,79]. Psychosocial, cultural and economic factors can also contribute to potential gender differences [80,81].

In this regard, the overall certainty of evidence across key outcome domains reported in this systematic review can be considered low to moderate based on the NIH quality assessment. While many epidemiological studies report a higher prevalence of vestibular disorders among females [34,35,38,43,68], some population-based and clinical investigations did not identify significant sex-related differences in prevalence, clinical presentation, or patient-reported outcomes, underscoring the heterogeneity of available evidence [15,65,74]. Moreover, epidemiological sex differences do not in themselves imply causal biological mechanisms; therefore, mechanistic interpretations discussed below—predominantly derived from retrospective or cross-sectional designs with heterogeneous methodologies—should be regarded as biologically plausible hypotheses rather than established explanations. These aspects will be addressed in the subsequent sections and in view of the different vestibular disorders considered in this review.

4.1. The Role of Hormones in Vestibular Disorders

Recent reviews have comprehensively highlighted the critical role of sex hormones—specifically estrogen and progesterone—in modulating vestibular function and symptom severity in several conditions [78,79]. The rapid decline in estrogen levels during menopause may correlate with impaired otoconial metabolism, contributing to an increased risk of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) in post-menopausal women [72,82,83,84]. These hypotheses originate from mechanistic and epidemiological studies [84], but also from analyses on animal models [72]. Furthermore, hormonal imbalances have been associated with symptom exacerbation in Ménière’s disease (MD), where estrogen-related changes in inner ear microcirculation might play a role [85]. Estrogen replacement might be beneficial in reducing vestibular symptoms in post-menopausal MD patients [85]. These findings underscore the influence of gonadal hormones on vestibular disorders and point to the potential benefits of incorporating hormonal evaluations into routine clinical assessments [79]. Moreover, emerging evidence suggested that the differences extend beyond hormonal regulation alone [8]. Epidemiological data supported this hypothesis. Hülse et al. (2019) analyzed a sample of over 70 million individuals and found that women were disproportionately affected by vestibular disorders such as BPPV, MD and vestibular migraine (VM) in comparison to men, with the sex difference remaining significant even after menopause [34]. Vereeck et al. (2008) also found that, beside age, sex significantly influenced postural control and balance performance [86]. Analyzing 318 participants (180 women, 138 men), they observed that women exhibited significantly poorer results than men in the Romberg test with eyes closed, standing on one leg with eyes closed, and parallel stance on foam with eyes closed [86]. Anatomical and neuro-chemical variations between male and female vestibular systems provided reasonable explanations for the different manifestations of vestibular dysfunction in women. Moriyama et al. (2007 and 2016) highlighted that females tended to have fewer myelinated axons in the vestibular nerve compared to males, which might influence vestibular signal transmission [87,88]. Additionally, considering an animal model, Ayyildiz et al. (2008) reported differences in size and structure of vestibular nuclei, with reduced volumes in female rats [89]. Neuro-chemical systems, including serotonin, dopamine and GABA, which differ between males and females, may influence vestibular processing by modulating conscious perception, anxiety responses to vestibular symptoms and sensitivity to medications like antihistamines and benzodiazepines, which are commonly prescribed for vestibular disorders [8].

4.2. Ménière’s Disease

MD has increasingly been examined through the prism of sex and gender medicine, as the emerging literature suggests potential differences in epidemiology, clinical presentation and therapeutic response between males and females. Several studies have highlighted the female predominance of MD [17,35,50,84,86,89]. A large population-based study in the United Kingdom on 5508 MD patients reported that 65.4% of cases occurred in women, with a mean age at diagnosis of approximately 55 years [17,90,91,92]. Similar findings emerged from an Italian nationwide survey, where 72% of the 520 enrolled patients were females [93]. Analogous epidemiological trends were observed in Japan, with a consistently higher prevalence in females compared to males over several decades [51]. Additionally, in a nationwide Korean large cohort of MD patients from 2008 to 2020, the annual incidence rose from 12.4 per 100,000 persons in 2008 to 50.5 per 100,000 in 2020, with females showing significantly higher prevalence rates than males (70.6% in 2008 and 68.8% in 2020, respectively) [35]. Sex-stratified analyses revealed that in females the incidence was significantly higher in spring and autumn and significantly lower in winter than in summer, whereas males only demonstrated a winter reduction without significant increases in spring or autumn [36].

Seasonal variation in MD might be related to weather conditions, as high humidity and low atmospheric pressure—common in Korean summers—have been linked to vertigo, tinnitus and ear fullness [7,94]. Pressure changes could influence endolymphatic hydrops, while greater physical activity and fatigue in spring through autumn could further trigger symptoms, particularly in males and younger patients [7,94].

Beyond incidence, differences in symptoms and disease burden have also been described. Women frequently report greater symptom severity, including more intense vertigo and higher levels of psychosocial distress, particularly anxiety and depression, compared to men [78]. Moreover, fluctuations in symptom expression have been associated with hormonally sensitive periods, such as the menstrual cycle, pregnancy and menopause, suggesting a potential hormonal modulation of endolymphatic hydrops or fluid homeostasis in the inner ear [33,42,78].

In a comparative study on stress hormones across inner ear disorders, Horner and Cazals [33] found that MD patients showed altered stress-hormone regulation, including a distinctive positive correlation between cortisol and prolactin in females, a pattern absent in males and in other inner ear disorders. This sex-specific coupling supported the hypothesis that prolactin might play a prominent role in symptom expression of female MD patients, potentially contributing to both the observed female predominance and the seasonal vulnerability to environmental and physiological stressors [33]. Furthermore, menstrual-cycle phases could influence MD responses, with some women experiencing post-menstruation symptom reduction, while others with premenstrual magnification patterns showed no changes [42].

An Italian pilot non-randomized controlled study [19] investigated the impact of combined oral contraceptives containing drospirenone and ethinyl estradiol, associated with vestibular rehabilitation therapy, in women with MD who experienced premenstrual exacerbation of symptoms. The combined treatment significantly reduced the frequency and severity of vertigo, tinnitus and hearing fluctuations during the luteal phase [19]. These preliminary findings suggested that drospirenone’s anti-mineralcorticoid and hormonal regulatory effects might help modulate inner ear fluid regulation/balance, and drospirenone-containing contraceptives might represent a promising therapeutic option for managing hormonally influenced fluctuations in MD.

The association with migraine is also worth mentioning. Epidemiological studies have long noted a higher prevalence of migraine among MD patients than in the general population, raising the possibility of shared pathophysiological mechanisms [8,88,89,95]. In a cohort of 95 individuals with unilateral intractable MD, Diao et al. [25] reported that patients with comorbid migraine were more frequently female (72%), experienced a longer disease duration and higher vertigo attack frequency, yet paradoxically showed better residual hearing compared to MD patients without migraine. Interestingly, anatomical variations were also noted, with the migraine subgroup patients displaying poor mastoid pneumatization and reduced sigmoid sinus–external ear canal distance. These findings might indicate a migraine-associated MD subtype, potentially driven by overlapping vascular, neurogenic and inflammatory pathways [96], and the recognition of this phenotype could improve diagnostic precision and guide individualized management, particularly in women, who appear disproportionately affected when migraine and MD coexist [97].

These insights collectively highlight the importance of incorporating a gender-sensitive perspective into MD, as considering hormonal status or stress-related factors in clinical assessment may help targeted interventions and could improve symptom management and guide future research.

4.3. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

BPPV is the most common form of vertigo, with an annual incidence rate of 10.7–600.0/100,000, accounting for 20–30% of vestibular diagnoses [98]. Like other vestibular disorders, BPPV affects women more frequently than men [7,8,34]: several studies showed a statistically significant female predominance in BPPV [7,12,36,63]. According to the studies by Taura, Yang, and Wang, the prevalence among females was approximately twice than in males (2:1 ratio) [60,67,72]. Additionally, in 8611 patients with BPPV, Adams et al. [10] found that women and patients over 70 years of age were significantly more likely to be diagnosed compared to men and people aged 66 to 69.

As previously stated, sex hormones, particularly estrogen and progesterone, are now widely recognized as crucial in modulating vestibular function and symptom severity in various conditions [78,79]. Moreover, estradiol (E2) is essential for bone growth and the development and maintenance of bone health in adulthood. E2 is involved in the prevention of bone loss by changing the natural regulators of bone mass and maintaining the production of osteoprotegerin. The decline of estrogen levels decreases the rate of bone turnover and consequently causes bone loss. E2 levels are known to decline with age, with a marked decline during menopause. This is potentially relevant for BPPV pathophysiology, since the calcium–vitamin D metabolism is known to affect the stability of the otoconia within the semicircular canals’ ampullae. During the menopausal period, as well as in late pregnancy epochs, fluctuating estrogen levels may be associated with otoconial degeneration, which represents the pathophysiological base for the development of BPPV [47,99].

Additionally, in females, it has been recognized that with increasing age, serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D3) and estradiol (E2) decreased [72]. Yang et al. [72] evaluated 102 postmenopausal women, 52 with BPPV and 50 controls, and highlighted that serum E2 and vitamin 25(OH)D3 levels were significantly lower in patients with BPPV than in age-matched controls. This suggests that E2 and 25(OH)D3 deficiency may be an important risk factor for idiopathic BPPV in postmenopausal female patients. A large survey by Ogun et al. [47] confirmed the role of menopause, showing that 48.1% of BPPV women experienced their first episode after menopause. The study by Li et al. [39] on 484,303 participants aged 40 to 69 years recruited using the UK Bank proved that elderly females (aged ≥ 60 years old) with osteoporosis had a higher risk of developing BPPV.

Insufficient and lower serum 25(OH)D3 was also reported to be associated with BPPV relapse, but without a significant difference in gender-based risk distribution [23,41]. However, Otsuka [49], considering 53 out of 357 with recurrent BPPV, found that the incidence of relapse was higher in females than in males, with 69.8% females versus 30.2% males at the first recurrence, 81.8% versus 18.2%, and 100% versus 0% at the second and third recurrences, respectively. Maintaining adequate levels of vitamin D could help to reduce the risk of otolith-related dizziness and improve the clinical situation in those who suffer from it. Vitamin supplementation should therefore be considered as an adjuvant, as it is easily available and accessible; however, prospective studies are still lacking to confirm whether it can prevent or reduce relapses [41].

Regarding non-pharmacological treatments, the Epley maneuver was reported to be effective and safe for posterior canal BPPV (PC-BPPV), although female gender, sleep disorders and inner ear diseases were associated with recurrence. Analyzing 243 patients with PSC-BPPV, Su et al. [58] found that after canalith repositioning with the Epley maneuver, the recurrence was significantly higher in females than in males. Considering 234 patients with PC-BPPV, Domínguez-Durán et al. [27] reported no significant gender-related differences in recovery, defined as loss of nystagmus regardless of loss of symptoms, 7 days after the same Epley maneuver. The absence of gender difference could be related to residual disability, as demonstrated by Petri’s study, which found an early higher DHI score with severe and moderate handicaps both in women and men with BPPV, that substantially resolved one month after treatment [51]. Also, Carrillo Muñoz patients diagnosed with BPPV-PC in primary care perceived their condition as disabling based on DHI scores, with women reporting higher levels of handicap than males [18]. In 132 BPPV patients, Martens [41] concluded that a higher dizziness handicap was associated with the female gender.

The diagnosis of BPPV is based on the medical history, associated symptoms and the presence of nystagmus; Choi et al. [22], by a questionnaire evaluating the directionality of linear vertigo, found that female gender did not represent an independent risk factor for variations in the clinical presentation of vertigo in BPPV. Regarding the medical history, we should not forget to consider some disorders which, as we found in this review, were more frequent in women with BPPV. Female and younger age (<60 years) with a history of BPPV had a higher likelihood of concurrent comorbidities of BPPV and migraine [33]. Furthermore, in BPPV, metabolic syndrome was more prevalent in females [71]. Female gender was also an independent risk factor for developing BPPV in patients with anxiety disorder, as reported by Chen [21] and Ferrari [30]. In the analysis of some psychological comorbidities and especially their relationship with the handicap reported through self-assessment questionnaires in a sample of patients with dizziness, a greater disability was found in females [21,30,51,52].

The association of BPPV and MD has been reported [100,101]. The percentage of patients with MD experiencing BPPV ranges between 10% and 70% [102,103]. Several authors described that patients with BPPV associated with MD differed from patients with idiopathic BPPV in terms of epidemiological and clinical features [12,101,103,104,105]. Apart from a longer duration of symptoms and a higher recurrence rate [12,101,103,104], a significant female predominance was observed, with an even higher percentage (93%) of female patients affected when the two disorders co-exist [12,101,103,105]. This consistent gender imbalance suggests that women may have increased susceptibility to otoconial detachment in the context of endolymphatic hydrops, potentially mediated by hormonal influences, bone metabolism differences, or inner ear microstructural vulnerability. These findings underscore the need for sex-specific considerations in both diagnostic evaluation and therapeutic strategies for BPPV in MD patients.

4.4. Vestibular Migraine

The association between vertigo and migraine, and vice versa, has been widely described, and nowadays it is well established, with VM being a recognized disorder diagnosed according to the criteria defined by the Consensus of Bárány Society [106] and the Third Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society [107]. However, the female preponderance of migrainous vertigo was reported even before the proposal of diagnostic criteria for VM [108], with a reported female-to-male ratio ranging between 1.5 and 5 to 1 [109,110,111,112]. The female predominance was confirmed by two large epidemiological studies reporting 75.8% and 81% of women among 584 and 2515 patients affected by VM, respectively [37,113]. Also, the more recent study by Lin et al. (2024) showed a significant female preponderance of VM, with a female-to-male ratio of approximately 3.3:1 [40]. Notably, the female predominance fluctuated with age, being 2.2:1 in patients < 30 years, 4.2:1 in those aged 31–60 years, and 2.9:1 in patients > 60 years. Hormonal influences, particularly fluctuations in estrogen levels and Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide release, affect the vestibular and trigeminal systems and imply that women are more likely to develop migraine and related vestibular symptoms across reproductive years [114,115]. VM symptoms may worsen due to the hormonal shifts that occur during the menstrual cycle, particularly the drop in estrogen levels in the days leading up to and during menstruation [116,117]. Also, pregnancy can influence vestibular disorders [118], and VM may either improve during gestation due to loss of cyclical fluctuation of estrogen levels or exacerbate and occur ex novo towards the end of pregnancy and early postpartum period, possibly influenced by sleep deprivation, stress and hormonal fluctuations [119].

Evidence for male and female differences in VM treatment response is limited but suggestive. In their series of VM patients primarily treated by trigger management alone, Lin et al. (2024) observed a comparable success rate between males and females by the end of the first-year treatment course, both being greater than 70% [40]. Selectively for females, they observed that women aged > 45 years showed a significantly better improvement from trigger management than younger women. This better control of VM observed in older females, presumably peri- or postmenopausal, may arise from the concomitant stabilization of their reproductive hormone status after menopause [40]. A single-center cohort study [28] found female sex to be a positive predictor of better response to standard VM therapies (i.e., antidepressants, antiepileptics, beta blockers, vestibular rehabilitation); women on average had greater reductions in DHI compared to men, particularly in the emotional and functional domains. The evident sexual dimorphism in VM prevalence may reflect hormonal fluctuations that explain the better response in females [28]. This dimorphism may also represent a gender disparity in reporting VM symptoms, especially non-specific vestibular complaints, as men seem to be more likely to report abnormal anxiety or depression in comparison to women [120]. The previously mentioned finding that women improve more than men suggests that biological sex might be considered when counseling patients about prognosis in VM.

4.5. Vestibular Neuritis

VN is traditionally considered a benign, self-limited peripheral vestibular disorder, yet emerging perspectives in gender medicine suggest that sex-related biological and socio-cultural determinants may influence its incidence, clinical expression and outcomes. In many studies [38,60,65,69], which analyzed the epidemiology of vertigo, although VN cases were grouped with other conditions, the sex imbalance suggests potential gender-related vulnerability or healthcare-seeking behavior differences. The incidence of VN was significantly different by sex, age and residence, with the highest values in females, people aged 60 years or older, and people who resided in metropolitan cities. VN is thought to be caused by reactivation of latent virus infection, autoimmunity, or microvascular ischemia [36]. Furthermore, VN could induce anxiety, because it appears with acute severe vestibular symptoms. The higher incidence of VN in women can be related to anxiety, which is more common in females [36]. However, considering the many possible causes of VN, the higher incidence of VN in females cannot be explained by anxiety alone. Hülse et al. emphasized that VN accounted for a notable fraction of acute vestibular presentations and 62.3% were women [34].

Beyond incidence, gender differences may emerge in seasonality and environmental susceptibility. Jeong et al. (2024) demonstrated that the risk of VN in males was lower in autumn and winter than in summer; conversely, in females, the risk of VN was lower in winter than in summer but higher in spring and autumn than in summer [36]. While VN is classically linked to viral etiologies, sex-specific immunological responses may modulate susceptibility and recovery. Future research examining whether hormonal status or gender-related occupational exposures contribute to seasonality would be valuable.

A crucial dimension in gender medicine is symptom perception and healthcare utilization. Petri et al. (2017) assessed quality of life and disability in acute vestibular disorders and found significant impacts on daily functioning [51]. In this study, the most frequent diagnosis in both genders was VN, without significant differences between the two sexes. The study highlighted how the higher improvement in functional, emotional and physical pre-treatment DHI scores at one month after treatment was for patients with vestibular neuritis, a well-treatable condition. In their series, Wilhelmsen et al. (2009) found that sex significantly predicted dizziness and autonomic/anxiety-related symptoms, underlining how the classification of patients was crucial to provide a better basis for specific rehabilitation [70]. In patients with VN, recovery from acute vertigo is within days/weeks. However, residual balance problems are not unusual, because the neuro-otologic condition may have started a process triggering anxiety.

4.6. Limitations and Strengths

This review has several limitations. First, the available evidence on sex- and gender-related differences in vestibular disorders remains heterogeneous, as most studies are retrospective, single-center, and lack standardized diagnostic or therapeutic protocols. Sample sizes are often limited, and information on hormonal status is rarely documented or controlled for, limiting the ability to draw robust conclusions about sex-related biological mechanisms. Furthermore, the absence of standardized sex- and gender-sensitive reporting reduces data comparability and precludes comprehensive meta-analytic synthesis. Accordingly, the exploratory quantitative synthesis performed in this review was characterized by substantial statistical heterogeneity and should be interpreted with caution. Finally, the inclusion of multiple vestibular disorders with distinct pathophysiological mechanisms may limit the generalizability of cross-condition comparisons. It should also be noted that the literature is predominantly focused on BPPV and Ménière’s disease, reflecting the distribution of available studies. Recognizing this imbalance is important when interpreting the findings, as the overrepresentation of these conditions might limit the generalizability of our conclusions to less-studied vestibular disorders, such as vestibular migraine, vestibular neuritis, and PPPD.

Despite its limitations, this systematic review comprehensively highlights, in the context of gender medicine, how biological sex- and gender-related factors exert an influence on disease presentation, prevalence and outcomes of many vestibular disorders. Several studies reported a higher incidence of vestibular dysfunctions among women, suggesting that hormonal fluctuations, calcium metabolism, and vitamin D deficiency may contribute to this predisposition. Estrogen receptors within the inner ear and their regulatory effects on calcium homeostasis have been proposed as potential mechanisms underlying these sex-specific differences. Furthermore, lifestyle factors, comorbidities, and differential health-seeking behaviors between men and women may also modulate disease expression and clinical course. These findings underscore the importance of integrating a gender-based approach into the assessment and management of vestibular disorders, to achieve more accurate diagnosis, targeted prevention and individualized treatment strategies.

5. Conclusions

From a clinical perspective, the findings of this review suggest that sex- and gender-related factors may represent relevant modifiers of disease risk and clinical expression in vestibular disorders. Although sex- and gender-specific treatment algorithms cannot yet be recommended, awareness of factors such as hormonal status, menopausal transition, and alterations in calcium and vitamin D metabolism may help refine diagnostic assessment and patient counseling. Incorporating molecular and hormonal pathways that underlie sex differences in vestibular dysfunction with psychometric assessments and quality-of-life measures may contribute to disentangling the biological and psychosocial factors influencing disease onset, progression and treatment response.

Future research should prioritize prospective, adequately powered studies specifically designed to assess sex and gender influences in vestibular disorders.

Finally, adopting standardized frameworks for sex/gender data collection and reporting—such as the SAGER guidelines—would improve reproducibility and support a more equitable and personalized approach to vestibular medicine.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diagnostics16020197/s1, S1: PRISMA Checklist, Excluded studies, Table “Quality Assessment in agreement with the National Institutes of Health quality assessment tool for Observational Cohorts and Cross-Sectional Studies”, Random-effects (REML) forest plot of mean Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) differences (Female—Male).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M.; methodology, L.F., A.F. and D.P.; validation, all authors; formal analysis, G.B., A.F. and L.F.; investigation, all authors; data curation, G.B., A.F. and L.F., writing—original draft preparation, L.F., A.F., D.P. and G.M.; writing—review and editing, L.F., A.F., D.P., C.P., R.C. and G.M.; visualization, all authors; supervision, C.d.F., E.Z. and G.M.; funding acquisition, G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded with grant DOR2399707/23 (G. Marioni) from the University of Padova, Italy. The funding source had no role in study design and conduction.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alison Garside for checking the English version of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Piani, F.; Baffoni, L.; Strocchi, E.; Borghi, C. Gender-specific medicine in the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines from 2018 to 2023: Where are we going? J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alswat, K.A. Gender disparities in osteoporosis. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2017, 9, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.; Cliffe, C.; Hillyard, M.; Majeed, A. Gender identity and the management of the transgender patient: A guide for non-specialists. J. R. Soc. Med. 2017, 110, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.; Diamond, M.; Green, J.; Karasic, D.; Reed, T.; Whittle, S.; Wylie, K. Transgender people: Health at the margins of society. Lancet 2016, 388, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, G.; Corsini, A.; Floreani, A.; Giannini, S.; Zagonel, V. Gender medicine: A task for the third millennium. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2013, 51, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanon, A.; Sorrentino, F.; Franz, L.; Brotto, D. Gender-related hearing, balance and speech disorders: A review. Hear. Balance Commun. 2019, 17, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.O.; Choi, J.Y.; Kim, J.S. Etiologic distribution of dizziness and vertigo in a referral-based dizziness clinic in South Korea. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 2252–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.F.; Agrawal, Y.; Darlington, C.L. Sexual dimorphism in vestibular function and dysfunction. J. Neurophysiol. 2019, 121, 2379–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, S.; Babor, T.F.; De Castro, P.; Tort, S.; Curno, M. Sex and gender equity in research: Rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2016, 1, 2, Erratum in Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2024, 9, 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-024-00155-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.E.; Marmor, S.; Yueh, B.; Kane, R.L. Geographic variation in use of vestibular testing among Medicare beneficiaries. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2017, 156, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balatsouras, D.G.; Ganelis, P.; Aspris, A.; Economou, N.C.; Moukos, A.; Koukoutsis, G. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo associated with Meniere’s disease: Epidemiological, pathophysiologic, clinical, and therapeutic aspects. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2012, 121, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baré, M.; Lleal, M.; Sevilla-Sánchez, D.; Ortonobes, S.; Herranz, S.; Ferrandez, O.; Corral-Vázquez, C.; Molist, N.; Nazco, G.J.; Martín-González, C.; et al. Sex Differences in multimorbidity, inappropriate medication and adverse outcomes of inpatient care: MoPIM Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisdorff, A.; Bosser, G.; Gueguen, R.; Perrin, P. The epidemiology of vertigo, dizziness, and unsteadiness and its links to co-morbidities. Front. Neurol. 2013, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittar, R.S.; Lins, E.M. Clinical characteristics of patients with persistent postural-perceptual dizziness. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 81, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantberg, K.; Baloh, R.W. Similarity of vertigo attacks due to Meniere’s disease and benign recurrent vertigo, both with and without migraine. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011, 131, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruderer, S.G.; Bodmer, D.; Stohler, N.A.; Jick, S.S.; Meier, C.R. Population-based study on the epidemiology of Ménière’s disease. Audiol. Neurootol. 2017, 22, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo Muñoz, R.; Ballve Moreno, J.L.; Villar Balboa, I.; Matos, Y.R.; Puertolas, O.C.; Ortega, J.A.; Perez, E.R.; Curto, X.M.; Ripollès, C.R.; Moreno Farres, A.; et al. Disability perceived by primary care patients with posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, S.; Mauro, D.; Maiolino, L.; Grillo, C.; Rapisarda, A.M.C.; Cianci, S. Effects of combined oral contraception containing drospirenone on premenstrual exacerbation of Meniere’s disease: Preliminary study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 224, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casani, A.P.; Ducci, N.; Lazzerini, F.; Vernassa, N.; Bruschini, L. Preceding benign paroxysmal positional vertigo as a trigger for persistent postural-perceptual dizziness: Which clinical predictors? Audiol. Res. 2023, 13, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.J.; Chang, C.H.; Hu, L.Y.; Tu, M.-S.; Lu, T.; Chen, P.-M.; Shen, C.-C. Increased risk of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in patients with anxiety disorders: A nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.Y.; Park, Y.M.; Lee, S.H.; Choi, J.; Hyun, S.W.; Song, J.-M.; Kim, H.-J.; Oh, H.J.; Kim, J.-S. Linear vertigo in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: Prevalence and mechanism. Cerebellum 2021, 20, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, L.H.; Bailey, V.O.; Liu, Y.F.; Teixido, M.T.; Rizk, H.G. Relationship of vitamin D levels with clinical presentation and recurrence of BPPV in a Southeastern United States institution. Auris Nasus Larynx 2023, 50, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, H.S.; Kimball, K.T. Increased independence and decreased vertigo after vestibular rehabilitation. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2003, 128, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, T.; Han, L.; Jing, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Yu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, H.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; et al. The clinical characteristics and anatomical variations in patients with intractable unilateral Meniere’s disease with and without migraine. J. Vestib. Res. 2022, 32, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlugaiczyk, J.; Lempert, T.; Lopez-Escamez, J.A.; Teggi, R.; von Brevern, M.; Bisdorff, A. Recurrent vestibular symptoms not otherwise specified: Clinical characteristics compared with vestibular migraine and Menière’s disease. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 674092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Durán, E.; Domènech-Vadillo, E.; Álvarez-Morujo de Sande, M.G.; González-Aguado, R.; Guerra-Jiménez, G.; Ramos-Macías, Á.; Morales-Angulo, C.; Martín-Mateos, A.J.; Figuerola-Massana, E.; Galera-Ruiz, H. Analysis of risk factors influencing the outcome of the Epley maneuver. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 274, 3567–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornhoffer, J.R.; Liu, Y.F.; Donaldson, L.; Rizk, H.G. Factors implicated in response to treatment/prognosis of vestibular migraine. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 278, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeltagy, R.; El-Hafeez, M.A. Efficacy of vestibular rehabilitation on quality of life of patients with unilateral vestibular dysfunction. Indian J. Otol. 2018, 24, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Monzani, D.; Baraldi, S.; Simoni, E.; Prati, G.; Forghieri, M.; Rigatelli, M.; Genovese, E.; Pingani, L. Vertigo “in the pink”: The impact of female gender on psychiatric-psychosomatic comorbidity in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo patients. Psychosomatics 2014, 55, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habs, M.; Strobl, R.; Grill, E.; Dieterich, M.; Becker-Bense, S. Primary or secondary chronic functional dizziness: Does it make a difference? A DizzyReg study in 356 patients. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, D.B.; Luryi, A.L.; Bojrab, D.I.; Babu, S.C.; Hong, R.S.; Rivera, O.J.S.; Schutt, C.A. Comparison of associated comorbid conditions in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with or without migraine history: A large single institution study. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2020, 41, 102650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horner, K.C.; Cazals, Y. Stress hormones in Ménière’s disease and acoustic neuroma. Brain Res. Bull. 2005, 66, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hülse, R.; Biesdorf, A.; Hörmann, K.; Stuck, B.; Erhart, M.; Hülse, M.; Wenzel, A. Peripheral vestibular disorders: An epidemiologic survey in 70 million individuals. Otol. Neurotol. 2019, 40, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Youk, T.M.; Choi, H.S. Incidence of peripheral vestibular disorders based on population data of South Korea. J. Vestib. Res. 2023, 33, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Youk, T.M.; Jung, H.T.; Choi, H.S. Seasonal variation in peripheral vestibular disorders based on Korean population data. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2024, 9, e1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Cheon, C. Epidemiology and seasonal variation of Ménière’s disease: Data from a population-based study. Audiol. Neurootol. 2020, 25, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.T.; Wang, T.C.; Chuang, L.J.; Chen, M.H.; Wang, P.C. Epidemiology of vertigo: A National Survey. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2011, 145, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, L.; An, P.; Pang, W.; Yan, X.; Deng, D.; Song, Y.; Mao, M.; Qiu, K.; Rao, Y.; et al. Low bone mineral density and the risk of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2024, 170, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.Y.; Rauch, S.D. Current demography and treatment strategy of vestibular migraine in neurotologic perspective. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2024, 171, 1842–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, C.; Goplen, F.K.; Aasen, T.; Nordfalk, K.F.; Nordahl, S.H.G. Dizziness handicap and clinical characteristics of posterior and lateral canal BPPV. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 276, 2181–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, G.G.; House, J.W. Changes in Ménière’s disease responses as a function of the menstrual cycle. Nurs. Res. 2001, 50, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, T.; Itoh, A.; Misawa, H.; Ohno, Y. Clinicoepidemiologic features of sudden deafness diagnosed and treated at university hospitals in Japan. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2000, 123, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhauser, H.K.; von Brevern, M.; Radtke, A.; Lezius, F.; Feldmann, M.; Ziese, T.; Lempert, T. Epidemiology of vestibular vertigo: A neurotologic survey of the general population. Neurology 2005, 65, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, F.S.; Alghwiri, A.A.; Whitney, S.L. Predictors of dizziness and hearing disorders in people with long COVID. Medicina 2023, 59, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogun, O.A.; Büki, B.; Cohn, E.S.; Janky, K.L.; Lundberg, Y.W. Menopause and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Menopause 2014, 21, 886–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogun, O.A.; Janky, K.L.; Cohn, E.S.; Büki, B.; Lundberg, Y.W. Gender-based comorbidity in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuki, J.; Takahashi, M.; Odagiri, K.; Wada, R.; Sato, R. Comparative study of the daily lifestyle of patients with Meniere’s disease and controls. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2005, 114, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, K.; Ogawa, Y.; Inagaki, T.; Shimizu, S.; Konomi, U.; Kondo, T.; Suzuki, M. Relationship between clinical features and therapeutic approach for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo outcomes. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2013, 127, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelosi, S.; Schuster, D.; Jacobson, G.P.; Carlson, M.L.; Haynes, D.S.; Bennett, M.L.; Rivas, A.; Wanna, G.B. Clinical characteristics associated with isolated unilateral utricular dysfunction. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2013, 34, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, M.; Chirilă, M.; Bolboacă, S.D.; Cosgarea, M. Health-related quality of life and disability in patients with acute unilateral peripheral vestibular disorders. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 83, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piker, E.G.; Jacobson, G.P.; McCaslin, D.L.; Grantham, S.L. Psychological comorbidities and their relationship to self-reported handicap in samples of dizzy patients. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2008, 19, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plescia, F.; Salvago, P.; Dispenza, F.; Messina, G.; Cannizzaro, E.; Martines, F. Efficacy and pharmacological appropriateness of Cinnarizine and Dimenhydrinate in the treatment of vertigo and related symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.I.; Park, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Jeon, E.J. Correlation between serum vitamin D level and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo recurrence. Auris Nasus Larynx 2023, 50, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaku, H.; Watanabe, Y.; Fujisaka, M.; Tsubota, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Yasumura, S.; Mizukoshi, K. Epidemiologic characteristics of definite Ménière’s disease in Japan. A long-term survey of Toyama and Niigata prefectures. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 2005, 67, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaku, H.; Watanabe, Y.; Yagi, T.; Takahashi, M.; Takeda, T.; Ikezono, T.; Ito, J.; Kubo, T.; Suzuki, M.; Takumida, M.; et al. Changes in the characteristics of definite Meniere’s disease over time in Japan: A long-term survey by the Peripheral Vestibular Disorder Research Committee of Japan, formerly the Meniere’s Disease Research Committee of Japan. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009, 129, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skøien, A.K.; Wilhemsen, K.; Gjesdal, S. Occupational disability caused by dizziness and vertigo: A register-based prospective study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2008, 58, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Liu, Y.C.; Lin, H.C. Risk factors for the recurrence of post-semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo after canalith repositioning. J. Neurol. 2016, 263, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, M. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo comorbid with hypertension. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2017, 137, 482–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taura, A.; Ohgita, H.; Funabiki, K.; Miura, M.; Naito, Y.; Ito, J. Clinical study of vertigo in the outpatient clinic of Kyoto University Hospital. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2010, 130, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taybeh, E.O.; Naser, A.Y. Hospital admission profile related to inner ear diseases in England and Wales. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toupet, M.; Van Nechel, C.; Hautefort, C.; Heuschen, S.; Duquesne, U.; Cassoulet, A.; Grayeli, A.B. Influence of visual and vestibular hypersensitivity on derealization and depersonalization in chronic dizziness. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutar, B.; Berkiten, G.; Saltürk, Z.; Kumral, T.L.; Göker, A.E.; Ekincioglu, M.E.; Uyar, Y.; Tuna, Ö.B. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: Analysis of 516 cases. B-ENT 2018, 14, 251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Wada, M.; Takeshima, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Nagasaka, S.; Kamesaki, T.; Kajii, E.; Kotani, K. Association between smoking and the peripheral vestibular disorder: A retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahat, N.H.A.; Sevasankaran, R.; Abdullah, A.; Ali, R.A. Prevalence of vestibular disorders among otology patients in a tertiary hospital in Malaysia. Int. Med. J. 2013, 20, 312–314. [Google Scholar]

- Waissbluth, S.; Becker, J.; Sepúlveda, V.; Iribarren, J.; García-Huidobro, F. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo secondary to acute unilateral peripheral vestibulopathy: Evaluation of cardiovascular risk factors. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 2023, 19, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chi, F.L.; Jia, X.H.; Tian, L.; Richard-Vitton, T. Does benign paroxysmal positional vertigo explain age and gender variation in patients with vertigo by mechanical assistance maneuvers? Neurol. Sci. 2014, 35, 1731–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, B.K.; Agrawal, Y.; Hoffman, H.J.; Carey, J.P.; Della Santina, C.C. Prevalence and impact of bilateral vestibular hypofunction: Results from the 2008 US National Health Interview Survey. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2013, 139, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassermann, A.; Finn, S.; Axer, H. Age-associated characteristics of patients with chronic dizziness and vertigo. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2022, 35, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsen, K.; Ljunggren, A.E.; Goplen, F.; Eide, G.E.; Nordahl, S.H. Long-term symptoms in dizzy patients examined in a university clinic. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2009, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, T.; Fukuda, T.; Shirota, S.; Sawai, Y.; Murai, T.; Fujita, N.; Hosoi, H. The prevalence and characteristics of metabolic syndrome in patients with vertigo. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Gu, H.; Sun, W.; Li, Y.; Wu, H.; Burnee, M.; Zhuang, J. Estradiol deficiency is a risk factor for idiopathic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in postmenopausal female patients. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.H.; Xirasagar, S.; Cheng, Y.F.; Wu, C.S.; Kuo, N.W.; Lin, H.C. Peripheral vestibular disorders: Nationwide evidence from Taiwan. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetiser, S.; Ince, D. Demographic analysis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo as a common public health problem. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 2015, 5, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Ishikawa, K.; Wong, W.H.; Shibata, Y. A clinical epidemiological study in 2169 patients with vertigo. Auris Nasus Larynx 2009, 36, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zborayova, K.; Barrenäs, M.L.; Granåsen, G.; Kerber, K.; Salzer, J. Dizziness and vertigo sick leave before and after insurance restrictions—A descriptive Swedish nationwide register linkage study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, W.; Tang, L.; Liu, H.; Li, F. Older patients with persistent postural-perceptual dizziness exhibit fewer emotional disorders and lower vertigo scores. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazzi, V.; Ciorba, A.; Skarżyński, P.H.; Skarżyńska, M.B.; Bianchini, C.; Stomeo, F.; Bellini, T.; Pelucchi, S.; Hatzopoulos, S. Gender differences in audio-vestibular disorders. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2020, 34, 2058738420929174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucci, V.; Hamid, M.; Jacquemyn, Y.; Browne, C.J. Influence of sex hormones on vestibular disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2022, 35, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertelt-Prigione, S. The influence of sex and gender on the immune response. Autoimmun. Rev. 2012, 11, A479–A485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brescia, G.; Contro, G.; Ruaro, A.; Barion, U.; Frigo, A.C.; Sfriso, P.; Marioni, G. Sex and age-related differences in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps electing ESS. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2022, 43, 103342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Liu, F.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Q. Association between osteoporosis and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: A systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Vijayakumar, S.; Jones, S.M.; Lundberg, Y.Y.W. Mechanism underlying the effects of estrogen deficiency on otoconia. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2018, 19, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.H. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo risk factors unique to perimenopausal women. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, M.C.; Maiolino, L.; Rapisarda, M.C.A.; Caruso, G.; Palermo, G.; Caruso, S. Effects of hormone therapy containing drospirenone and estradiol on postmenopausal exacerbation of Ménière’s disease: Preliminary study. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereeck, L.; Wuyts, F.; Truijen, S.; Van de Heyning, P. Clinical assessment of balance: Normative data, and gender and age effects. Int. J. Audiol. 2008, 47, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, H.; Itoh, M.; Shimada, K.; Otsuka, N. Morphometric analysis offibers of the human vestibular nerve: Sex differences. Eur. Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2007, 264, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, H.; Hayashi, S.; Inoue, Y.; Itoh, M.; Otsuka, N. Sex differences inmorphometric aspects of the peripheral nerves and related diseases. NeuroRehabilitation 2016, 39, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, M.; Kozan, R.; Agar, E.; Kaplan, S. Sexual dimorphism in the medialvestibular nucleus of adult rats: Stereological study. Anat. Sci. Int. 2008, 83, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, L.B.; Schessel, D.A.; Carey, J.P. Ménière’s disease. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2004, 17, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrrell, J.S.; Whinney, D.J.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Fleming, L.E.; Osborne, N.J. Prevalence, associated factors, and comorbid conditions for Ménière’s disease. Ear Hear. 2014, 35, e162–e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Lee, C.H.; Yoo, D.M.; Kwon, M.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Park, B.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, H.G. Association between Meniere disease and migraine. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 148, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammarella, F.; Loperfido, A.; Keeling, E.G.; Bellocchi, G.; Marsili, L. Ménière’s disease: Insights from an Italian nationwide survey. Audiol. Res. 2023, 13, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.; Sarran, C.; Ronan, N.; Barrett, G.; Whinney, D.J.; Fleming, L.E.; Osborne, N.J.; Tyrrell, J. The weather and Ménière’s disease: A longitudinal analysis in the UK. Otol. Neurotol. 2017, 38, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, A.; Lempert, T.; Gresty, M.A.; Brookes, G.B.; Bronstein, A.M.; Neuhauser, H. Migraine and Ménière’s disease: Is there a link? Neurology 2002, 59, 1700–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ravin, E.; Quimby, A.E.; Bartellas, M.; Swanson, S.; Hwa, T.P.; Bigelow, D.C.; Brant, J.A.; Ruckenstein, M.J. An update on the epidemiology and clinicodemographic features of Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 3310–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, J.M.; Balaban, C.D. Vestibular migraine. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1343, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cui, Q.; Gong, S. Knowledge mapping of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo from 2002 to 2021: A bibliometric analysis. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 2024, 20, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, P.G.; Napolitano, B.; Alessandrini, M.; Girolamo, S.D.; Magrini, A. Recurrent paroxysmal positional vertigo related to oral contraceptive treatment. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2006, 22, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, C.A.; Proctor, L. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope 1997, 107, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlberg, M.; Hall, K.; Quickert, N.; Hinson, J.; Halmagyi, G.M. What inner ear diseases cause benign paroxysmal positional vertigo? Acta Otolaryngol. 2000, 120, 380–385. [Google Scholar]

- Paparella, M.M. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and other vestibular symptoms in Ménière disease. Ear Nose Throat J. 2008, 87, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zeng, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Huang, X. Clinical analysis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo secondary to Menière’s disease. Sci. Res. Essays 2010, 5, 3672–3675. [Google Scholar]

- Riga, M.; Bibas, A.; Xenellis, J.; Korres, S. Inner ear disease and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: A critical review of incidence, clinical characteristics, and management. Int. J. Otolaryngol. 2011, 2011, 709469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.H.; Ban, J.H.; Lee, K.C.; Kim, S.M. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo secondary to inner ear disease. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2010, 143, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lempert, T.; Olesen, J.; Furman, J.; Waterston, J.; Seemungal, B.; Carey, J.; Bisdorff, A.; Versino, M.; Evers, S.; Kheradmand, A.; et al. Vestibular migraine: Diagnostic criteria (Update)1: Literature update 2021. J. Vestib. Res. 2022, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhauser, H.; Lempert, T. Vertigo and dizziness related to migraine: A diagnostic challenge. Cephalalgia 2004, 24, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cass, S.P.; Ankerstjerne, J.K.P.; Yetiser, S.; Furman, J.; Balaban, C.; Aydogan, B. Migraine-related vestibulopathy. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1997, 106, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.D. Medical management of migraine-related dizziness and vertigo. Laryngoscope 1998, 108, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, M.; Brandt, T. Episodic vertigo related to migraine (90 cases): Vestibular migraine? J. Neurol. 1999, 246, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhauser, H.; Leopold, M.; Von Brevern, M.; Arnold, G.; Lempert, T. The interrelations of migraine, vertigo and migainous vertigo. Neurology 2001, 56, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formeister Eric, J.; Rizk Habib, G.; Kohn Michael, A.; Sharon Jeffrey, D. The epidemiology of vestibular migraine: A population-based survey study. Otol. Neurotol. 2018, 39, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, J.M.; Marcus, D.A.; Balaban, C.D. Vestibular migraine: Clinical aspects and pathophysiology. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Sanchez, J.M.; Lopez-Escamez, J.A. New insights into pathophysiology of vestibular migraine. Front. Neurol. 2015, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allais, G.; Chiarle, G.; Sinigaglia, S.; Mana, O.; Benedetto, C. Migraine during pregnancy and in the puerperium. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 40, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khiati, R.; Tighilet, B.; Besnard, S.; Chabbert, C. Vestibular disorders and hormonal dysregulations: State of the art and clinical perspectives. Cells 2023, 12, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, L.; Frosolini, A.; Parrino, D.; Badin, G.; Piccoli, V.; Poli, G.; Bertocco, A.G.; Spinato, G.; de Filippis, C.; Marioni, G. Balance control and vestibular disorders in pregnant women: A comprehensive review on pathophysiology, clinical features and rational treatment. Sci. Prog. 2025, 108, 368504251343778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Yu, X.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhan, T.; He, Y. Clinical significance of serum sex hormones in postmenopausal women with vestibular migraine: Potential role of estradiol. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 3000605211016379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurre, A.; Straumann, D.; van Gool, C.J.; Gloor-Juzi, T.; Bastiaenen, C.H. Gender differences in patients with dizziness and unsteadiness regarding self-perceived disability, anxiety, depression, and its associations. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2012, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.