Abstract

Background: The current biomarker classification system does not fully explain the increased prevalence of both Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular risk factors for AD—such as diabetes and hypertension--among African Americans (AAs) compared to White participants. Research on cognitive aging has traditionally focused on how declines in cortical and hippocampal regions influence cognition. However, tau pathology emerges decades before amyloid pathology, initially appearing in the brainstem, particularly in the locus coeruleus (LC), the primary source of the brain’s norepinephrine (NE). Further, postmortem studies suggest that the loss of LC neurons is a better predictor of AD symptom severity than amyloid-beta/neurofibrillary tangle pathology in any other brain region. Methods: Our decade-long studies in humans using a norepinephrine transporter (NET)-selective radiotracer ([11C]MRB) have demonstrated that LC is uniquely vulnerable to aging and stress. In this retrospective study, regression slopes with age (RSAs) for regional NET availability were compared across groups and tested for statistical significance. Results: In our primary analysis, higher NET availability was observed in AAs (N = 14; 7 males aged 23–49), particularly at younger ages, as compared to White (N = 16; 11 males aged 24–55) participants. Our preliminary data also suggest that the rate of decline in NET availability is faster in AAs, with a potential trend toward a more pronounced effect in AA males as compared to White males (e.g., in the left thalamus, RSA was −3.03%/year [95%CI: −5.80% to 1.19%] for AA males vs. RSA = −0.14 for White males [95%CI: −0.79% to 0.47%]. Additionally, in the right anterior cingulate cortex, RSA was −3.4%/year [95%CI: −4.6% to −1.4%] for AA males, compared to RSA = 0.3%/year [95%CI: 0.04% to 1.03%] for White males). Conclusions: This report reveals that NET availability (measured with [11C]MRB) can serve as a biomarker to index the function of the LC-NE system and that the fast-decline rate of NET in AAs implicates a potential molecular mechanism underlying health disparities observed in the disproportionate AD prevalence.

1. Introduction

Despite the racial and ethnic diversity of the global population, significant gaps exist in the scientific literature regarding Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk factors—including stress, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and vascular disorders—among African Americans (AAs). AAs have been underrepresented in many prominent AD biomarker studies and clinical trials [1]. By 2050, minorities are projected to account for 42% of the nation’s older adults [2], posing critical challenges for aging AAs due to evidence suggesting a two- to three-fold higher prevalence of AD in this group compared to White individuals [2,3,4,5]. The precise reasons for this disparity remain unclear, but limited studies suggest that biological mechanisms may exhibit race-dependent variability, potentially contributing to differences in the manifestation of AD.

Neuroimaging biomarkers in AD have increasingly been used to facilitate earlier diagnoses, enable disease staging, and recruit participants for clinical trials. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has played a pivotal role in AD research over the past decade, enabling in vivo accurate detection of Aβ (amyloid-beta) plaques and tau pathology. This has resulted in the well-established ATN framework as follows: amyloid (A), tau (T), and neurodegeneration (N). While a robust connection exists between Aβ and tau, the relationship between Aβ and neurodegeneration remains weak. Current evidence suggests that tau pathology, rather than Aβ, is more strongly associated with brain atrophy, hypometabolism, and cognitive decline [6]. However, racial and ethnic differences in AD biomarkers remain underexplored, and existing data often present conflicting results. For instance, in one of the largest studies to date, performed on the ARIC-PET [7], a community-based cohort without dementia, AAs exhibited a higher burden of amyloid plaques ([18F] florbetapir PET imaging) after adjusting for vascular risk factors [7]. Conversely, subsequent study in Washington University cohorts reported no racial differences in brain Aβ burden ([11C]PIB) or for Aβ concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), while CSF total tau (T-tau) and p-tau were lower in AAs than in White participants when both carried APOE ε4 gene (p < 0.001) [8]. These results were similar to other studies [9,10], and showed that the degree of cognitive impairment in AAs with lower CSF tau remained comparable to that of White individuals with higher CSF tau burden. This suggests that lower tau levels in AAs do not necessarily offer protection against AD.

Autopsy studies corroborate this complexity. Among confirmed AD cases, AAs and White participants with similar clinical dementia severity demonstrated no significant differences in either Aβ or neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) burdens [11]. Additionally, findings on hippocampal volumetric differences between AAs and Whites have been inconsistent. From the same studies described above, smaller hippocampal volume for AAs than White participants was indicated in one study [8], while other studies reported no racial differences even among cohorts with cognitive normality (CN) or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [9,10]. However, AAs appear to be more vulnerable to the cognitive effects of cerebrovascular disease than their White counterparts [10].

These findings highlight limitations in the current ATN biomarker classification system (the ATN model [12]: amyloid (A), tau (T), and neurodegeneration (N)), which falls short of explaining the disproportionate prevalence of both AD and vascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) in AAs compared to Whites [3,4,5,13,14,15]. Dr. Williams and others [16,17,18,19,20] have proposed that systemic factors—including residential segregation, discriminatory healthcare practices, and chronic stressors—may influence higher rates of stress [21], anxieties [22], poorer sleep [23,24], and increased prevalence of cigarette smoking, alcohol and substance use, and depression and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders (ADHD) [25], and increased prevalence of both AD and vascular disorders such as hypertension [26,27,28,29,30,31,32], diabetes [33,34], obesity [35], and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) in AAs [17,22,36,37,38,39], when compared to White participants. Together, they contribute to significantly higher rates for premature mortality [38,40] and AD in this population.

Cognitive aging research has historically focused on cortical and hippocampal decline in relation to cognition, but tau pathology often predates amyloid pathology by decades. Tau pathology initially manifests in the brainstem, particularly in the locus coeruleus (LC), which serves as the brain’s primary source of norepinephrine (NE) [41]. Further, postmortem studies suggest that LC neuron loss is a stronger predictor of the clinical severity of AD symptoms than Aβ or neurofibrillary pathology in cortical or subcortical regions [42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. LC neurons also exert a broad influence over CNS function, particularly in the integration of the adaptive CNS response to various stressors or challenges [49,50], and are a major factor in the pathophysiology of most stress-induced disorders.

Our decades-long research using a norepinephrine transporter (NET)-selective radiotracer ((S,S)-[11C]O-methyl reboxetine; [11C]MRB) [51,52] has demonstrated the significant vulnerability of the LC-NE system to numerous conditions, including addiction [53], ADHD [54,55,56], obesity [57,58,59,60,61,62,63], brown fat [64,65], diabetes [66], cardiovascular dysfunction [67], and sleep disorders (review [51,52] and references cited within). Preliminary data on ethnicity- and race-associated differences show that NET availability diminishes more rapidly in AAs compared to Whites. This investigation seeks to elucidate molecular mechanisms underlying health disparities linked to increased AD prevalence and associated vascular risk factors in AAs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Healthy adult Black/African American (AA) and non-Hispanic White (nhW, abbreviated as White) participants without current medical conditions and no psychiatric histories were recruited as part of ongoing projects. These participants served as controls for comparison against subjects exhibiting specific disorders (e.g., cocaine addiction, ADHD, obesity, etc.), as described in the Introduction for this retrospective study. All imaging scans were conducted at Yale University using the same MRI and PET scanners with the same acquisition protocol and preprocessing pipeline. All studies employed the same NET-selective radiotracer ([11C]MRB), utilizing consistent production and imaging protocols under Dr. Ding’s IND (IND 071928). Each study received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at either Yale University (the Yale University School of Medicine Human Investigation Committee, HIC) or New York University School of Medicine (NYU Grossman School of Medicine Federal wide Assurance (FWA00004952)). An informed consent was obtained from each participant following a comprehensive explanation of the study. Self-identification served as the basis for race/ethnicity classification.

For this report, data analysis was performed on healthy adults, including AA participants (N = 14; 7 M, ages 23–49; mean age = 33.79 ± 7.49) and White participants (N = 16; 11 M, ages 24–55; mean age = 39.50 ± 11.04).

2.2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was conducted using a 3T Trio (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a circularly polarized head coil. MRI acquisition utilized a sagittal three-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence (MPRAGE) with the following parameters: echo time (TE) = 3.34 ms, repetition time (TR) = 2500 ms, inversion time (TI) = 1100 ms, flip angle = 7°, and bandwidth = 180 Hz/pixel. Images were acquired at a resolution of 256 × 256 × 176, with a voxel size of 0.98 × 0.98 × 1.0 mm.

2.3. PET Imaging and Data Analysis

[11C]MRB (a carbon-11 radiolabeled methyl reboxetine) was synthesized using a precursor ((S,S)-desethyl reboxetine) with high enantiomeric purity (>99.5%), as described previously [68]. Dynamic [11C]MRB images were acquired over a duration of 120 min using a High Resolution Research Tomograph (HRRT, CTI/Siemens) scanner and individual structure MRI images were acquired for co-registration purposes.

Post-processing and data analysis on the image data collected from healthy controls (AA and nhW) were conducted at NYU School of Medicine to investigate the potential effects of ethnicity/race on NET availability for this retrospective study. All identifiable info from each participant was erased, and only age, gender, race, and participant code number were used for post-processing and data analysis. Segmentation of cortical and subcortical regions of interest (ROIs) was performed using FreeSurfer (FS2005) based on the MRI atlas templates. Left and right olfactory (L and R Ofac) regions were also generated using the Destrieux Atlas [69]. Subsequent co-registration of PET, MRI, and the FreeSurfer atlas images for each participant was performed using Firevoxel software (developed at NYU, https://firevoxel.org), via mutual information algorithm with autofocus transformation. Time-activity curves (TACs) for each region were generated and [11C]MRB uptake in regional NET was quantified as binding potential (BPND). BPND reflects the density of transporters available for binding [70] and was calculated automatically using the multilinear reference tissue model 2 (MRTM2), with the occipital cortex serving as the reference region (a region with low density of NET and the absence of specific binding, based on our previous studies [55,56]). Further, we have previously shown that MRTM2-derived BPND estimates highly correlated with BPND values derived using arterial blood data [56], obviating the need for invasive blood sampling techniques.

The regional NET availability decline rate was then determined via linear regression models of the regional BPND values regressed on subject ages. The regression slopes with age (RSA, also known as annual percent change (APC) [71]) for each ROI was then estimated based on the linear regression (RSA = 100 × (exp(m) − 1), where m is the estimated slope of the age-decline rate of the regional BPND. The RSA was calculated for all 16 ROIs stratified by race and also by race and sex as four subgroups.

Statistical Analysis: Our primary analysis focused on differences in BPND by race. The distributions of BPND by race across all 16 ROIs were first evaluated using exploratory graphical methods. For the 14 bilaterally measured ROIs, values were then averaged across hemispheres to yield 7 ROIs, reducing the number of comparisons and preserving statistical power. Due to the small sample size, the regional differences in BPND between the two racial groups (classified as African American [AA] vs. White) were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank sum exact test, a nonparametric method that compares the ranks of observations between two independent groups without assuming a normal distribution [72]. The false discovery rate (FDR) was controlled using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to adjust for multiple comparisons across the Wilcoxon rank sum exact tests of the bilateral composite ROIs. Both the unadjusted p-values and the FDR-adjusted p-values (q-values) are reported [73].

Differences in age between the two racial groups (classified as African American [AA] vs. White) were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank sum exact test and differences in the distribution of sex across the two racial groups were evaluated using the Fisher exact test [72]. Since there were differences in the age range for AA (age 23 to 49) and White (age 24 to 55) participants, a subset of 12 White participants between the ages of 24 and 49 were selected to match the age range of the 14 AA participants. The mean age of the 12 White participants was 35 (95%CI: 31,39) and for the 14 AA participants it was 34 (95%CI: 30,38).

In sensitivity analyses, an overall composite measure of BPND was derived by averaging BPND values across all 16 ROIs for each participant. This composite outcome was intended to provide a global summary of BPND while reducing regional variability. Linear regression models were then fit with the composite BPND measure as the dependent variable and race as the primary independent variable, adjusting for age and sex as covariates. These analyses were conducted in both the complete sample (n = 30) and a restricted age-matched sample (n = 26) to evaluate the robustness of the findings of our primary analysis.

In exploratory analyses, the rate of decline in regional NET availability was determined for each ROI within subgroups defined by sex and race, using linear regression models with regional BPND values as the dependent variable and age as the predictor. The regression slopes with age (RSAs) for regional BPND values were then estimated using the following formula: RSA = 100 × (exp(m) − 1), where m is the estimated regression slope of age on the regional BPND values. The bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) method was employed to derive 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for the RSAs. The subgroups were compared in terms of RSA using a matched-pairs Wilcoxon signed-rank test, as the RSA measurements were considered matched because they were derived from the same ROIs. All statistical tests were conducted at a two-sided 5% significance level using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and IBM SPSS statistics version 28.0.1.1 (14).

3. Results

3.1. Associations of NET Availability with Race, Sex, and Age

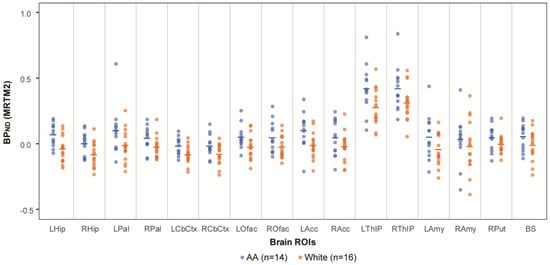

Across all sixteen investigated brain ROIs, the mean BPND values (representing NET availability) were consistently higher in AA participants compared to White participants (Figure 1). In the primary analyses, racial differences in BPND were statistically significant in six of the seven bilaterally averaged ROIs with false discovery rate-adjusted assessment (q-value), with AA participants having consistently higher BPND compared to White participants (Table 1). In the sensitivity analysis of the composite measure of BPND, AA participants had significantly higher BPND than White participants, both in the model including all participants (N = 30, p = 0.02) as well as in the age-matched sample (N = 26, p = 0.02). The covariates of age and sex did not reach significance in either model (all p > 0.45).

Figure 1.

NET availability comparison between AA and White. NET availability (measured as BPND values of [11C]MRB) comparison of AA (N = 14; ages 33.8 ± 7.2, blue symbols) vs. White participants (N = 16; ages 39.5 ± 10.7; orange symbols). Mean values are shown as a horizontal line for each racial group and ROI.

Table 1.

Analysis of regional NET availability (BPND) with race.

3.2. Race Effects and Sex Effects on Age-Associated Decline Rate of Regional NET Availability

Although neither age nor sex were significantly different between racial groups (Wilcoxon rank sum exact test for age by race, p = 0.15; Fisher exact test for sex by race, p = 0.46), the absence of statistically significant differences does not imply covariate balance, particularly given the limited sample size. Accordingly, results from subsequent analyses were interpreted as exploratory rather than confirmatory.

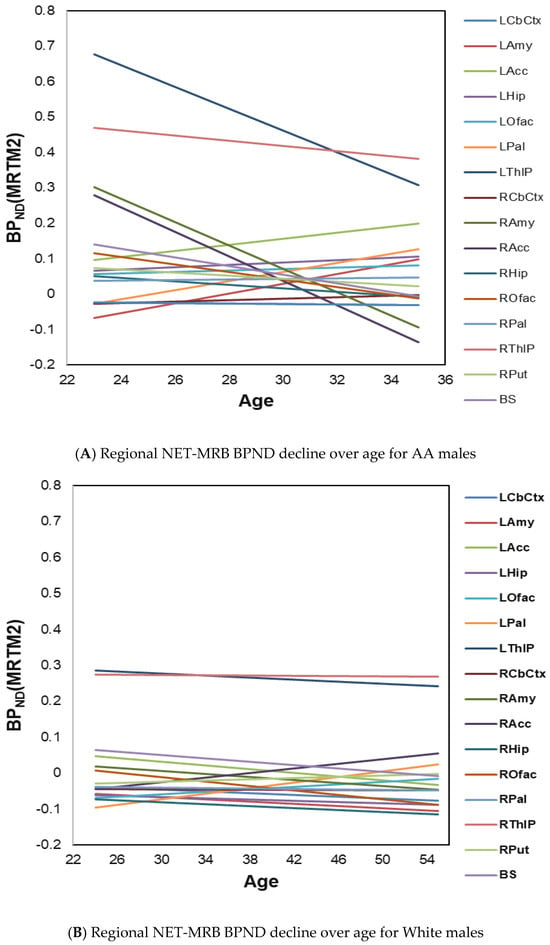

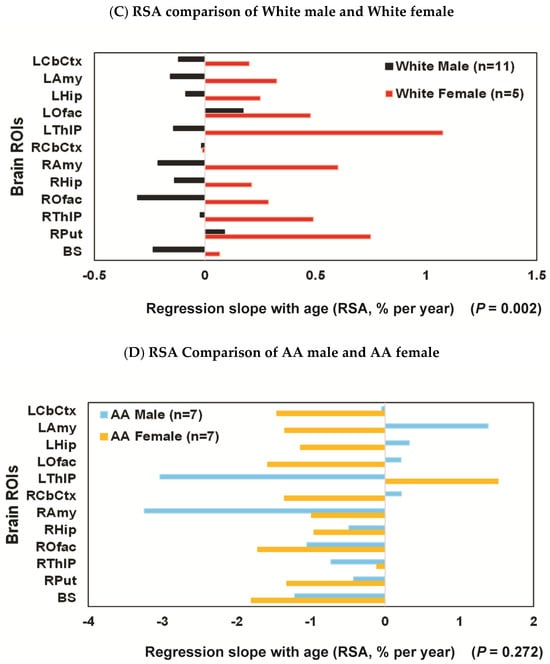

In exploratory analyses, the regression slopes with age (RSAs) in regional BPND values were then estimated using linear regression models of age predicting NET-MRB BPND for each ROI within subgroups defined by sex and race. Out of all healthy adults, including both sexes and races (AAs, N = 14, ages 33.8 ± 7.2; White, N = 16, ages 39.5 ± 10.7), substantially greater age-related decline rates in regional NET-MRB BPND were observed in AA males (n = 7, ages 29.7 ± 4.3). Specifically, AA males showed negative slopes in more brain regions and much steeper declines in some brain regions (Figure 2A) compared to White males (n = 11, ages 40.4 ± 10.9) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Age-effects on regional NET-MRB BPND decline rates in healthy AA males (n = 7, ages 29.7 ± 4.3); (B) age-effects on regional NET-MRB BPND decline rates in White males (n = 11, ages 40.4 ± 10.9).

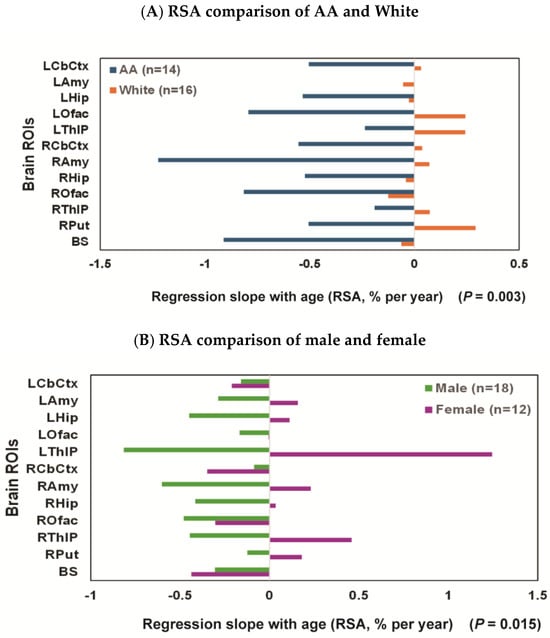

In the exploratory analysis for the effects of race, the decline rates of regional brain ROIs were faster in AAs: e.g., decline rates in BS and ROfac were −0.91% and −0.81%/year, respectively, for AA; by comparison, decline rates in BS and ROfac were −0.06 and −0.13%/year, respectively, for White (Figure 3A). The difference in RSA by race reached significance in the summary measure over 16 ROIs and 12 ROIs both in all participants and in age-matched groups (all p ≤ 0.003) (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Regression slopes with age (RSAs) comparisons: (A) the RSA decline rate for each ROI was consistently faster for AA (N = 14; ages 33.8 ± 7.2, blue bars) than for White participants (N = 16; ages 39.5 ± 10.7; orange bars); (B) female (N = 12; ages 25–54 (37.8 ± 9.5); purple bar) vs. male (N = 18; ages 23–55 (36.2 ± 9.9); green bar), with the RSA decline rate faster for males than females; (C) White female (n = 5; ages 37.6 ± 12.4; red bar) vs. White male (n = 11; ages 40.4 ± 10.9; black bar), with the RSA decline rate faster for males than females; (D) AA female (n = 7; ages 37.9 ± 8.0; light orange bar) vs. AA male (n = 7; ages 29.7 ± 4.3; light blue bar), the RSA decline rates were high for both AA females and AA males, and the sex difference did not reach significance in this subgroup.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of RSA by race.

In the exploratory analysis for sex effects [female (N = 12, ages 25–54 (37.8 ± 9.5)) and male (N = 18, ages 23–55 (36.2 ± 10.2))], there was a significant difference in RSA (p = 0.01) with decline rates faster for males, e.g., −0.8, −0.6, −0.5, −0.4, and −0.4%/year for left thalamus (LThlP), right amygdala (RAmy), right olfactory (ROfac), hippocampus (Lhip & RHip), and right thalamus (RThlP), respectively. While the difference in RSA by sex did not quite reach significance in the summary measure over 16 ROIs (p = 0.063) (Table 3), it did reach significance when only 12 ROIs (LCbCtx, Lamy, LHip, LOfac, LThlP, RCbCtx, RAmy, RHip, ROfac, RThlP, RPut, and BS) were included in the computation (p = 0.015) (Figure 3B and Table 3).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of RSA by sex.

The sex effect was also significant within all Whites (n = 5, females aged 37.6 ± 12.4 and n = 11, males aged 40.4 ± 10.9) with the RSA decline rate faster for males than females both over 16 ROIs (p < 0.001) (Table 3) and 12 ROIs (p = 0.002) (Figure 3C and Table 3). When AA females (n = 7; ages 37.9 ± 8.0) and AA males (n = 7; ages 29.7 ± 4.3) were compared, the RSA decline rates were high in most regions for both sexes (e.g., −3%/year in LThlP and RAmy and over −1.2%/year in BS and ROfac for AA males vs. −1.8%/year in BS and Ofac for AA females), and the sex difference did not reach significance in these AA subgroups (p = 0.272) (Figure 3D and Table 3). Notably, there appeared a trend suggesting a more pronounced effect in AA males compared to White males (e.g., RSA = −3.03%/year [bootstrap 95%CI: −5.80% to 1.19%] in the left thalamus for AA males vs. RSA = −0.14 for White males [bootstrap 95%CI: −0.79% to 0.47%]. Additionally, in the right anterior cingulate cortex, RSA was −3.4%/year [bootstrap 95%CI: −4.6% to −1.4%] for AA males, compared to RSA = 0.3 cyr [bootstrap 95%CI: 0.04% to 1.03%] for White males).

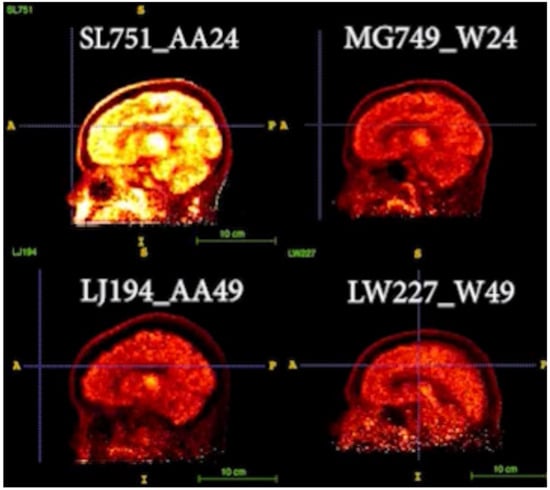

3.3. Representative Images

Two pairs of age-matched AA vs. White images were compared in Figure 4 [video images are presented in the Supplemental Section (Video S1) to demonstrate the kinetics of regional tracer uptake over 100 min of the PET dynamic scans after the injection of [11C]MRB, starting at t = 20 min].

Figure 4.

Two pairs of age-matched AA vs. White images are displayed [images of age-24 pair of AA and White (top panel; participant codes of SL751_AA24, MG749_W24, respectively) and age-49 pair of AA and White participants (bottom panel; participant codes of LJ194_AA49, LW227_W49, respectively)]. Their static PET images at the same time frame were compared (occipital was used as the reference region and for setting the contrast). Hot yellow (or bright white) indicated high signal intensity (i.e., higher tracer uptake and binding).

In Figure 4, the static PET BPND images (occipital as the reference region) at the same time frame after the injection of [11C]MRB were compared. As shown in the top panel, the intensity of AA24 is much higher than W24, suggesting higher NET availability of AA than White at younger age (e.g., 24). However, NET density is decreased with age, particularly with a faster decline rate in AA than that in White, as shown in the bottom panel for age 49 participants as follows: the intensities of these images are lower, and the differences between AA and White are not as significant as those displayed in the top panel.

4. Discussion

Our current understanding of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) biomarkers and pathological changes derives almost exclusively from research studies involving White participants. For example, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) has provided major insights into the pathological cascade and timeline of AD; however, ADNI-1 included less than 5% African American (AA) participants, limiting its ability to determine whether significant racial differences exist. If AD does exhibit racial disparities, AAs may have increased vulnerability to the disease.

In this relatively young cohort (ages ~20–50), our preliminary results demonstrated that NET availability, measured as binding potential (BPND), is higher in AAs than Whites. This is consistent with research suggesting that stress triggers the release of NE from neurons, leading to increased activity in LC, the brain’s primary source of NE. Chronic stress, a prominent risk factor, has been shown to upregulate NET protein on neuron surfaces, altering how NE is cleared from the synapse and driving dysregulated stress responses [74]. These findings align with the hypothesis that AAs may experience greater chronic stress due to systemic socioeconomic and psychosocial factors.

Furthermore, our results revealed that AAs exhibit significantly faster age-related declines in NET availability compared to Whites, as indicated by regression slopes with age (RSAs) measurements. These findings suggest that PET imaging of NET availability may serve as a potential early biomarker for preclinical AD in midlife—a critical time of biological and psychosocial transition, thus creating a “window of opportunity” for targeting prevention and treatment strategies. This study provides novel insights into the molecular mechanisms potentially underpinning racial and ethnic disparities within the preclinical stages of AD.

In contrast to NET findings, previous imaging studies using [11C]PIB have reported no racial differences in brain amyloid burden. Although CSF tau levels showed group differences, current tau radioligands cannot reliably detect early tau pathology in the LC due to their off-target binding with neuromelanin, which is abundant in the LC [75,76,77]. Similarly, recent studies using synaptic vesicle tracers (e.g., [11C]UCBJ) to measure synaptic density do not appear sensitive to age effects in most brain regions (the LC remains unexplored) [78]. However, based on our preliminary research across various disorders (e.g., cocaine addiction [53], ADHD [54,55,56,79], obesity [57,58,59,60,61], brown fat [64,65], diabetes [66], cardiovascular dysfunction [67], and sleep disorders; review [51,52] and references cited within), we have demonstrated that (S,S)-[11C]O-methyl reboxetine ([11C]MRB) is one of the most effective tracers to date for in vivo imaging of LC-NE function in humans. Findings from these studies underscore the broad influence of LC neurons on CNS adaptive responses to stress [49,50], and suggest that LC-NE dysfunction plays a critical role in stress-related disorders [80,81]. This highlights the importance of disrupted LC-NE tone in treating stress-related pathologies and understanding racial health disparities.

Degeneration of the LC has been implicated as a key feature of AD [82,83,84,85], more closely associated with cognitive decline than cell loss in other cortical or subcortical nuclei [86]. Postmortem studies suggest that the loss of LC neurons better predicts the onset and severity of clinical symptoms of AD than Aβ plaques, NFTs, or degeneration in other brain regions [42,43,44,45,46,47]. Our preliminary findings align with social behavioral research on socioeconomic adversity and chronic stress to health disparities in the United States. AAs experience higher rates of chronic stress-related conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity, all of which are also significant risk factors for AD. Understanding these population-level differences can pave the way for interventions, novel therapeutic targets, and public health strategies aimed at reducing racial/ethnic health disparities, thereby improving the quality of life for aging populations. Continued research should prioritize understanding, preventing, and treating health disparities as a public health imperative.

To conclude, this research provides critical insights into the following: (i) a novel potential marker (NET availability) to detect LC dysfunction associated with increased AD pathology during normal aging; (ii) a potential mechanism linking chronic stress to the disproportionately high prevalence of AD and vascular diseases—including hypertension [26,27,28,29,30,31,32], diabetes [33,34], obesity [35], and cardiovascular conditions—among AAs compared to Whites [17,22,36,37,38,39]; and (iii) the dysfunction of the LC-NE system as a possible driver of health disparities observed in AD expression.

There are some limitations of the study as it did not include information on the measurement of stress levels and other factors that might affect the outcome, such as BMI, socioeconomic status (SES), and education. Additionally, this study did not incorporate our newly adapted imaging methodology using state-of-the-art PET/MR combined scanner with simultaneously acquired and co-registered PET and MR images with a specific neuromelanin-MR sequences, which could provide more precise delineation of the LC region and a more accurate quantification of NET binding. For future studies, we will conduct all these measurements, and include clinical labs, biomarker analysis (e.g., A-beta and tau), and cognitive testing.

Finally, the study is limited by its small sample size, and while our preliminary findings reveal race- and sex-associated effects on NET availability, further studies with larger, systematically matched cohorts are necessary to validate these results. The purpose for publishing these pilot data as a Brief Research Report is to rapidly disseminate our initial findings to the scientific research field and provide a framework for future research to confirm and expand these novel, exploratory but critical observations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diagnostics16020190/s1, Video S1: Comparison of Two Pairs of Age-matched AA vs. White MRB-NET video images. Ref. [87] is cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Y.-S.D. contributed to the idea, initiation, and design of the study, worked on data collection, and secured research fundings. E.P. undertook formal statistical analysis, methodology, and software use. Y.-S.D. composed the manuscript, and Y.-S.D. and E.P. interpreted the study outcomes and edited the manuscript. J.W. contributed to data analysis and preparation of figures, A.M. contributed to data analysis software resources, J.C. contributed to data collection, H.R. contributed to manuscript editing, and J.B. performed and supervised the statistical analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Data presented in this report were collected from several research projects supported by Dr. Ding’s research grants and her collaborative grants (e.g., DA-06278, DA019062, R56DA190, K12 DA00016, R01 DK20495, and UL1RR024139). Data analysis and statistical analysis for this retrospective study performed at NYU School of Medicine are also supported by Ding’s research grants (R21AG064474, R01AG072644). The funding agency had no input on the study design, data analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Each study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at either Yale University (the Yale University School of Medicine Human Investigation Committee, HIC) or New York University School of Medicine (NYU Grossman School of Medicine Federal wide Assurance (FWA00004952)).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings presented in this study are available within the article. Because the primary study is ongoing, data will not be shared at this time.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| L (left) or R (right) of CbCtx, Amy, Acc, Hip, Ofac, Pal, ThlP, BS | |

| CbCtx | cerebellar cortex |

| Amy | amygdala |

| Acc | anterior cingulate cortex |

| Hip | hippocampus |

| Ofac | olfactory lobe |

| Pal | pallidum (Globus Pallidus) |

| THIP | thalamus |

| BS | brain stem |

References

- Shin, J.; Doraiswamy, P.M. Underrepresentation of African-Americans in Alzheimer’s Trials: A Call for Affirmative Action. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, L.L.; Bennett, D.A. Alzheimer’s Disease in African Americans: Risk Factors and Challenges for the Future. Health Aff. 2014, 33, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilworth-Anderson, P.; Hendrie, H.C.; Manly, J.J.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Fazio, S. Diagnosis and Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease in Diverse Populations. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2008, 4, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurland, B.J.; Wilder, D.E.; Lantigua, R.; Stern, Y.; Chen, J.; Killeffer, E.H.; Mayeux, R. Rates of Dementia in Three Ethnoracial Groups. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1999, 14, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, G.G.; Plassman, B.L.; Burke, J.R.; Kabeto, M.U.; Langa, K.M.; Llewellyn, D.J.; Rogers, M.A.; Steffens, D.C. Cognitive Performance and Informant Reports in the Diagnosis of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in African Americans and Whites. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2009, 5, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagust, W. Imaging the Evolution and Pathophysiology of Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, R.F.; Schneider, A.L.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.; Green, E.; Gupta, N.; Knopman, D.S.; Mintz, A.; Rahmim, A.; Sharrett, A.R.; et al. The Aric-Pet Amyloid Imaging Study: Brain Amyloid Differences by Age, Race, Sex, and Apoe. Neurology 2016, 87, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.C.; Schindler, S.E.; McCue, L.M.; Moulder, K.L.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; Cruchaga, C.; Fagan, A.M.; Grant, E.; Gordon, B.A.; Holtzman, D.M.; et al. Assessment of Racial Disparities in Biomarkers for Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, S.L.; McDaniel, D.; Obideen, M.; Trammell, A.R.; Shaw, L.M.; Goldstein, F.C.; Hajjar, I. Racial Disparity in Cerebrospinal Fluid Amyloid and Tau Biomarkers and Associated Cutoffs for Mild Cognitive Impairment. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1917363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.C.; Watts, K.D.; Parker, M.W.; Wu, J.; Kollhoff, A.; Wingo, T.S.; Dorbin, C.D.; Qiu, D.; Hu, W.T. Race Modifies the Relationship between Cognition and Alzheimer’s Disease Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2017, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, C.H.; Grant, E.A.; Schmitt, S.E.; McKeel, D.W.; Morris, J.C. The Neuropathology of Alzheimer Disease in African American and White Individuals. Arch. Neurol. 2006, 63, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological Definition Of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.Y.; Panegyres, P.K. The Role of Ethnicity in Alzheimer’s Disease: Findings from the C-Path Online Data Repository. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016, 51, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayeda, E.R.; Glymour, M.M.; Quesenberry, C.P.; Whitmer, R.A. Inequalities in Dementia Incidence between Six Racial and Ethnic Groups over 14 years. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2016, 12, 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, L.L.; Leurgans, S.; Aggarwal, N.T.; Shah, R.C.; Arvanitakis, Z.; James, B.D.; Buchman, A.S.; Bennett, D.A.; Schneider, J.A. Mixed Pathology Is More Likely in Black Than White Decedents with Alzheimer Dementia. Neurology 2015, 85, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Lawrence, J.A.; Davis, B.A. Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 105–125. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A. Racism and Health II: A Needed Research Agenda for Effective Interventions. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 1200–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A. Racism and Health I: Pathways and Scientific Evidence. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 1152–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R. Race and Health: Basic Questions, Emerging Directions. Ann. Epidemiol. 1997, 7, 322–333. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman, P.A.; Cubbin, C.; Egerter, S.; Williams, D.R.; Pamuk, E. Socioeconomic Disparities in Health in the United States: What the Patterns Tell Us. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, S186–S196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R. Stress and the Mental Health of Populations of Color: Advancing Our Understanding of Race-Related Stressors. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2018, 59, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, S.J.; Logel, C.; Davies, P.G. Stereotype Threat. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slopen, N.; Lewis, T.T.; Williams, D.R. Discrimination and Sleep: A Systematic Review. Sleep Med. 2016, 18, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicken, M.T.; Lee, H.; Ailshire, J.; Burgard, S.A.; Williams, R.D. “Every Shut Eye, Ain’t Sleep”: The Role of Racism-Related Vigilance in Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Sleep Difficulty. Race Soc. Probl. 2013, 5, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, A.M.; Cho, J.; Andrabi, N.; Barrington-Trimis, J. Association of Reported Concern About Increasing Societal Discrimination with Adverse Behavioral Health Outcomes in Late Adolescence. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrell, L.N.; Crawford, N.D.; Barrington, D.S.; Maglo, K.N. Black/White Disparity in Self-Reported Hypertension: The Role of Nativity Status. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2008, 19, 1148–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondolo, E.; Love, E.E.; Pencille, M.; Schoenthaler, A.; Ogedegbe, G. Racism and Hypertension: A Review of the Empirical Evidence and Implications for Clinical Practice. Am. J. Hypertens. 2011, 24, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiscella, K.; Holt, K. Racial Disparity in Hypertension Control: Tallying the Death Toll. Ann. Fam. Med. 2008, 6, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, F.D. Why Do Black Americans Have Higher Prevalence of Hypertension?: An Enigma Still Unsolved. Hypertension 2011, 57, 379–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjar, I.; Kotchen, T.A. Trends in Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA 2003, 290, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, I.; Kip, K.E.; Mulukutla, S.R.; Aiyer, A.N.; Marroquin, O.C.; Huggins, G.S.; Reis, S.E. Biogeographic Ancestry, Self-Identified Race, and Admixture-Phenotype Associations in the Heart Score Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 176, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolezsar, C.M.; McGrath, J.J.; Herzig, A.J.M.; Miller, S.B. Perceived Racial Discrimination and Hypertension: A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peek, M.E.; Cargill, A.; Huang, E.S. Diabetes Health Disparities: A Systematic Review of Health Care Interventions. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2007, 64, 101S–156S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller-Rowell, T.E.; Homandberg, L.K.; Curtis, D.S.; Tsenkova, V.K.; Williams, D.R.; Ryff, C.D. Disparities in Insulin Resistance between Black and White Adults in the United States: The Role of Lifespan Stress Exposure. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 107, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, C.O.; Bastos, J.L.; Gonzalez-Chica, D.A.; Peres, M.A.; Paradies, Y.C. Interpersonal Discrimination and Markers of Adiposity in Longitudinal Studies: A Systematic Review. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, J.; Burgess, D.; Phelan, S.M.; Juarez, L. Unhealthy Interactions: The Role of Stereotype Threat in Health Disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, J.B.; Hehman, E.; Ayduk, O.; Mendoza-Denton, R. Blacks’ Death Rate Due to Circulatory Diseases Is Positively Related to Whites’ Explicit Racial Bias. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 27, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Wildeman, C.; Wang, E.A.; Matusko, N.; Jackson, J.S. A Heavy Burden: The Cardiovascular Health Consequences of Having a Family Member Incarcerated. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.T.; Williams, D.R.; Tamene, M.; Clark, C.R. Self-Reported Experiences of Discrimination and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Cardiovasc. Risk Rep. 2014, 8, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, D.H.; Clouston, S.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Kramer, M.R.; Cooper, H.L.; Wilson, S.M.; Stephens-Davidowitz, S.I.; Gold, R.S.; Link, B.G. Association between an Internet-Based Measure of Area Racism and Black Mortality. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122963. [Google Scholar]

- Braak, H.; Thal, D.R.; Ghebremedhin, E.; Del Tredici, K. Stages of the Pathologic Process in Alzheimer Disease: Age Categories from 1 to 100 Years. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2011, 70, 960–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, S.C.; He, B.; Perez, S.E.; Ginsberg, S.D.; Mufson, E.J.; Counts, S.E. Locus Coeruleus Cellular and Molecular Pathology during the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2017, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gannon, M.; Che, P.; Chen, Y.; Jiao, K.; Roberson, E.D.; Wang, Q. Noradrenergic Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 220. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, W.J.; Chung, H.D.; Huang, J.S.; Huang, S.S.; Haring, J.H.; Strong, R.; Marshall, G.L.; Joh, T.H. Evidence for Retrograde Degeneration of Epinephrine Neurons in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann. Neurol. 1988, 24, 532–536. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, D.M.; Yates, P.O.; Hawkes, J. The Noradrenergic System in Alzheimer and Multi-Infarct Dementias. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1982, 45, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondareff, W.; Mountjoy, C.Q.; Roth, M. Selective Loss of Neurones of Origin of Adrenergic Projection to Cerebral Cortex (Nucleus Locus Coeruleus) in Senile Dementia. Lancet 1981, 1, 783–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondareff, W.; Mountjoy, C.Q.; Roth, M.; Rossor, M.N.; Iversen, L.L.; Reynolds, G.P.; Hauser, D.L. Neuronal Degeneration in Locus Ceruleus and Cortical Correlates of Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 1987, 1, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, M.; Harley, C.W. The Locus Coeruleus: Essential for Maintaining Cognitive Function and the Aging Brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2016, 20, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrousos, G.P. Stress and Disorders of the Stress System. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2009, 5, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrousos, G.P.; Gold, P.W. The Concepts of Stress and Stress System Disorders. Overview of Physical and Behavioral Homeostasis. JAMA 1992, 267, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.S.; Lin, K.S.; Logan, J. Pet Imaging of Norepinephrine Transporters. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006, 12, 3831–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.S. Progress in PET imaging of the norepinephrine transporter system. In PET and SPECT of Neurobiological Systems; Dierckx, R.A.J.O., Otte, A., de Vries, E.F.J., van Waarde, A., Lammertsma, A.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 561–584. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.S.; Lin, K.S.; Garza, V.; Carter, P.; Alexoff, D.; Logan, J.; Shea, C.; Xu, Y.; King, P. Evaluation of a New Norepinephrine Transporter Pet Ligand in Baboons, Both in Brain and Peripheral Organs. Synapse 2003, 50, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.S.; Naganawa, M.; Gallezot, J.D.; Nabulsi, N.; Lin, S.F.; Ropchan, J.; Weinzimmer, D.; McCarthy, T.J.; Carson, R.E.; Huang, Y.; et al. Clinical doses of atomoxetine significantly occupy both norepinephrine and serotonin transports: Implications on treatment of depression and ADHD. NeuroImage 2014, 86, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallezot, J.D.; Weinzimmer, D.; Nabulsi, N.; Lin, S.F.; Fowles, K.; Sandiego, C.; McCarthy, T.J.; Maguire, R.P.; Carson, R.E.; Ding, Y.S. Evaluation of [(11)C]MRB for assessment of occupancy of norepinephrine transporters: Studies with atomoxetine in non-human primates. NeuroImage 2011, 56, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannestad, J.; Gallezot, J.D.; Planeta-Wilson, B.; Lin, S.F.; Williams, W.A.; van Dyck, C.H.; Malison, R.T.; Carson, R.E.; Ding, Y.S. Clinically relevant doses of methylphenidate significantly occupy norepinephrine transporters in humans in vivo. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 68, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.S.; Potenza, M.N.; Lee, D.E.; Planeta, B.; Gallezot, J.D.; Labaree, D.; Henry, S.; Nabulsi, N.; Sinha, R.; Ding, Y.S.; et al. Decreased Norepinephrine Transporter Availability in Obesity: Positron Emission Tomography Imaging with (S,S)-[(11)C]O-Methylreboxetine. NeuroImage 2014, 86, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, S.; Becker, G.A.; Rullmann, M.; Bresch, A.; Luthardt, J.; Hankir, M.K.; Zientek, F.; Reissig, G.; Patt, M.; Arelin, K.; et al. Central Noradrenaline Transporter Availability in Highly Obese, Non-Depressed Individuals. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2017, 44, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melasch, J.; Rullmann, M.; Hilbert, A.; Luthardt, J.; Becker, G.A.; Patt, M.; Villringer, A.; Arelin, K.; Meyer, P.M.; Lobsien, D.; et al. The Central Nervous Norepinephrine Network Links a Diminished Sense of Emotional Well-Being to an Increased Body Weight. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinke, C.; Hesse, S.; Rullmann, M.; Becker, G.A.; Luthardt, J.; Zientek, F.; Patt, M.; Stoppe, M.; Schmidt, E.; Meyer, K.; et al. Central noradrenaline transporter availability is linked with HPA axis responsiveness and copeptin in human obesity and non-obese controls. Stress 2018, 22, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettermann, F.J.; Rullmann, M.; Becker, G.A.; Luthardt, J.; Zientek, F.; Patt, M.; Meyer, P.M.; McLeod, A.; Brendel, M.; Bluher, M.; et al. Noradrenaline Transporter Availability on [(11)C]Mrb Pet Predicts Weight Loss Success in Highly Obese Adults. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2018, 45, 1618–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresch, A.; Rullmann, M.; Luthardt, J.; Becker, G.A.; Patt, M.; Ding, Y.S.; Hilbert, A.; Sabri, O.; Hesse, S. Hunger and Disinhibition but Not Cognitive Restraint Are Associated with Central Norepinephrine Transporter Availability. Appetite 2017, 117, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bresch, A.; Rullmann, M.; Luthardt, J.; Becker, G.A.; Reissig, G.; Patt, M.; Ding, Y.S.; Hilbert, A.; Sabri, O.; Hesse, S. Emotional Eating and in Vivo Norepinephrine Transporter Availability in Obesity: A [(11) C]Mrb Pet Pilot Study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.J.; Yeckel, C.W.; Gallezot, J.D.; Aguiar, R.B.; Ersahin, D.; Gao, H.; Kapinos, M.; Nabulsi, N.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, D.; et al. Imaging Human Brown Adipose Tissue under Room Temperature Conditions with (11)C-Mrb, a Selective Norepinephrine Transporter Pet Ligand. Metabolism 2015, 64, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.F.; Fan, X.; Yeckel, C.W.; Weinzimmer, D.; Mulnix, T.; Gallezot, J.D.; Carson, R.E.; Sherwin, R.S.; Ding, Y.S. Ex Vivo and in Vivo Evaluation of the Norepinephrine Transporter Ligand [11c]Mrb for Brown Adipose Tissue Imaging. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2012, 39, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfort-DeAguiar, R.; Gallezot, J.D.; Hwang, J.J.; Elshafie, A.; Yeckel, C.W.; Chan, O.; Carson, R.E.; Ding, Y.S.; Sherwin, R.S. Noradrenergic Activity in the Human Brain: A Mechanism Supporting the Defense against Hypoglycemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 2244–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.S.; Holmes, C.; Ding, Y.-S.; Sharabi, Y. Neuroimaging evidence for decreased cardiac sympathetic innervation and a vesicular storage defect in residual nerves in Lewy body forms of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. In Proceedings of the American Autonomic Society 2018, Newport Beach, CA, USA, 28 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.S.; Singhal, T.; Planeta-Wilson, B.; Gallezot, J.D.; Nabulsi, N.; Labaree, D.; Ropchan, J.; Henry, S.; Williams, W.; Carson, R.E.; et al. Pet Imaging of the Effects of Age and Cocaine on the Norepinephrine Transporter in the Human Brain Using (S,S)-[(11)C]O-Methylreboxetine and Hrrt. Synapse 2010, 64, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Destrieux, C.; Fischl, B.; Dale, A.; Halgren, E. Automatic Parcellation of Human Cortical Gyri and Sulci Using Standard Anatomical Nomenclature. NeuroImage 2010, 53, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innis, R.B.; Cunningham, V.J.; Delforge, J.; Fujita, M.; Gjedde, A.; Gunn, R.N.; Holden, J.; Houle, S.; Huang, S.C.; Ichise, M.; et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2007, 27, 1533–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, L.X.; Hankey, B.F.; Tiwari, R.; Feuer, E.J.; Edwards, B.K. Estimating Average Annual Per Cent Change in Trend Analysis. Stat. Med. 2009, 28, 3670–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agresti, A. A Survey of Exact Inference for Contingency Tables. Stat. Sci. 1992, 7, 131–177. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Fan, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Z.; Bissette, G.; Zhu, M.Y. Chronic Social Defeat up-Regulates Expression of Norepinephrine Transporter in Rat Brains. Neurochem. Int. 2012, 60, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, A.K.; Knudsen, K.; Lillethorup, T.P.; Landau, A.M.; Parbo, P.; Fedorova, T.; Audrain, H.; Bender, D.; Østergaard, K.; Brooks, D.J.; et al. In Vivo Imaging of Neuromelanin in Parkinson’s Disease Using 18 F-Av-1451 Pet. Brain 2016, 139, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint-Aubert, L.; Lemoine, L.; Chiotis, K.; Leuzy, A.; Rodriguez-Vieitez, E.; Nordberg, A. Tau Pet Imaging: Present and Future Directions. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, L.; Leuzy, A.; Chiotis, K.; Rodriguez-Vieitez, E.; Nordberg, A. Tau Positron Emission Tomography Imaging in Tauopathies: The Added Hurdle of Off-Target Binding. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 10, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R.E.; Naganawa, M.; Matuskey, D.; Mecca, A.; Pittman, B.; Toyonaga, T.; Lu, Y.; Dias, M.; Nabulsi, N.; Finnema, S.; et al. Age and sex effects on synaptic density in healthy humans as assessed with SV2A PET. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 59, 541. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, S.; Muller, U.; Rullmann, M.; Luthardt, J.; Bresch, A.; Becker, A.G.; Zientek, F.; Patt, M.; Meyer, M.P.; Bluher, M.; et al. The Association between in Vivo Central Noradrenaline Transporter Availability and Trait Impulsivity. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2017, 267, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressler, K.J.; Nemeroff, C.B. Role of Norepinephrine in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Mood Disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 1999, 46, 1219–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerauer, M.; Fedorova, T.D.; Hansen, A.K.; Knudsen, K.; Otto, M.; Jeppesen, J.; Frederiksen, Y.; Blicher, J.U.; Geday, J.; Nahimi, A.; et al. Evaluation of the Noradrenergic System in Parkinson’s Disease: An 11c-Mener Pet and Neuromelanin Mri Study. Brain 2018, 141, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudzien, A.; Shaw, P.; Weintraub, S.; Bigio, E.; Mash, D.C.; Mesulam, M.M. Locus Coeruleus Neurofibrillary Degeneration in Aging, Mild Cognitive Impairment and Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2007, 28, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haglund, M.; Sjobeck, M.; Englund, E. Locus Ceruleus Degeneration Is Ubiquitous in Alzheimer’s Disease: Possible Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment. Neuropathology 2006, 26, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofilas, P.; Ehrenberg, A.J.; Dunlop, S.; Di Lorenzo Alho, A.T.; Nguy, A.; Leite, R.E.P.; Rodriguez, R.D.; Mejia, M.B.; Suemoto, C.K.; Ferretti-Rebustini, R.E.D.L.; et al. Locus Coeruleus Volume and Cell Population Changes during Alzheimer’s Disease Progression: A Stereological Study in Human Postmortem Brains with Potential Implication for Early-Stage Biomarker Discovery. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017, 13, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, B.E.; Irving, D.; Blessed, G. Cell Loss in the Locus Coeruleus in Senile Dementia of Alzheimer Type. J. Neurol. Sci. 1981, 49, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Nag, S.; Boyle, P.A.; Hizel, L.P.; Yu, L.; Buchman, A.S.; Schneider, J.A.; Bennett, D.A. Neural Reserve, Neuronal Density in the Locus Ceruleus, and Cognitive Decline. Neurology 2013, 80, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, T.; Pieper, S.; Fedorov, A.; Fillion-Robin, J.C.; Halle, M.; O’Donnell, L.; Lasso, A.; Ungi, T.; Pinter, C.; Finet, J.; et al. Increasing the Impact of Medical ImageComputing Using Community-Based Open-Access Hackathons: The Na-Mic and 3d SlicerExperience. Med. Image Anal. 2016, 33, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.