Abstract

Background: Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) is the most common congenital heart defect, and its complications (namely, dilatation of the thoracic ascending aorta) raise concerns regarding the proper timing of aortic surgery. The study aim is to unravel the genetic basis of BAV and its complications through a high-throughput sequencing (HTS) approach and segregation analysis if family members were available. Methods: Fifty-two Italian BAV patients were analyzed by HTS using the Illumina MiSeq platform. Targeted sequencing of 97 genes known to be or plausibly associated with connective tissue disorders or aorthopathy was performed. Thirty-five first-degree relatives of N = 10 probands underwent mutational screening for variants identified in the index cases. Results: HTS identified 194 rare (MAF < 0.01) variants in 63 genes. Regarding previously reported genes, five NOTCH1 variants in four BAV patients, four FBN1 variants in two patients and one GATA5 variant in one patient were identified. Interestingly, among further loci, the possible contribution of PDIA2, LRP1 and CAPN2 was suggested by (a) the increased prevalence of rare genetic variants, independently from their ACMG classification in the whole BAV cohort, and (b) segregation analyses of variants identified in family members. Moreover, the present data also suggest the possible contribution of rare variants to BAV complications, specifically MYLK in aortic dilatation, CAPN2 in BAV calcification and VHL and AGGF1 in valve stenosis. Conclusions: Our results underline clinical and genetic diagnosis complexity in traits considered monogenic, such as BAV, but characterized by variability in disease phenotypic expression (incomplete penetrance), as well as the contribution of different major and modifier genes to the development of complications.

1. Introduction

Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) represents the most common congenital cardiac defect (0.5–2%) and is the result of the fusion between adjacent aortic cusps during valvulogenesis [1]. BAV genetic determinants have been investigated by a large number of studies in both isolated as well as syndromic presentations. Indeed, a higher BAV prevalence was observed in patients affected by several genetic syndromes, including connective tissue disorders as Marfan, Loeys–Dietz and vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndromes [2,3,4]. From early analyses of aortic valves in genetically engineered mice to more recent next-generation sequencing (NGS) approaches on selected genes, several studies have been carried out to unravel the molecular mechanisms associated with BAV development and complications [5,6,7]. Moreover, the coexistence of BAV with syndromic disorders, increasing both morbidity and mortality [8], strengthens the genetic heterogeneity hypothesis in BAV pathogenesis and severity according to the different associated genes. Indeed, association with the abovementioned syndromes raises the issue of the role of their causative genes (e.g., FBN1, 15q21.1; TGFBR2, 3p24.1; TGFBR1, 9q22.33; ACTA2, 10q23.3) in BAV onset and complications. BAV often occurs in association with thoracic aortic aneurysms (TAAs), independently of age and severity of aortic valve hemodynamic impairment. Moreover, an increased incidence of thoracic aortic dissections is reported in BAV [8]. Other clinical consequences associated with BAV might be represented by aortic stenosis and insufficiency [9], as well as calcification [10].

These observations led to the hypothesis of a genetic architecture of BAV in which many different genetic variants interact in an integrated/synergic manner to influence BAV onset and complications [1]. Increasing knowledge on BAV genetic bases could improve clarification of its underlying molecular mechanisms, which could be translated into the clinical practice in order to predict its most feared complication, i.e., TAD, to establish individualized genetic risk profiles and to exclude syndromic traits in patients with suggestive manifestations [6,11]. In this respect, high-throughput sequencing (HTS) provides the opportunity to analyze a wide number of genes in order to confirm and identify novel candidate loci in BAV. Accordingly, the aim of this study is to unravel the genetic bases of BAV and its complications (TAA, calcification, aortic insufficiency and stenosis) using a 97-gene panel targeted HTS approach, focusing on 52 Italian index cases with non-syndromic BAV and using segregation analysis if family members were available.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

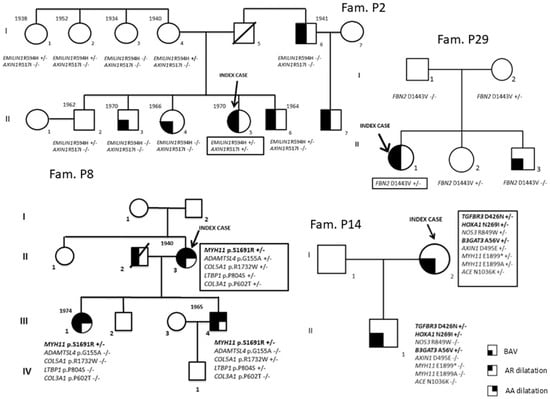

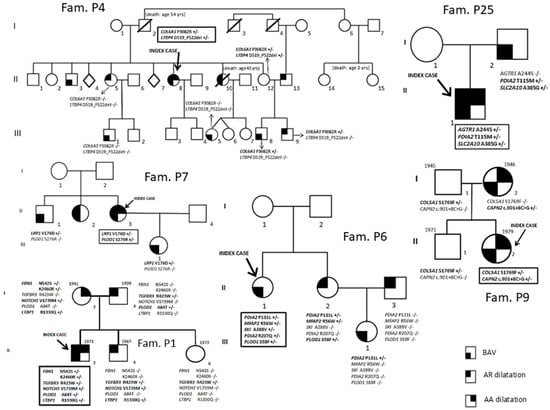

Fifty-two patients [34 males (65.4%); median age 42.5 years [interquartile (IQR) range 31–51.5 years]] diagnosed with BAV and referred from outpatient cardiologists to the Center for Marfan Syndrome and Related Disorders (Careggi Hospital, Florence) and the Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine (University of Florence) for clinical evaluation and differential diagnosis were included in the study. A multidisciplinary clinical evaluation is routinely performed for these patients, including cardiovascular investigation/imaging, ophthalmologist investigation, physical examination and genetic counseling/investigation. Concerning the timing of patients’ follow-up, patients are managed according to specific guidelines [12,13,14]. The study cohort comprised 9 patients without thoracic aortic dilatation and 43 patients with thoracic aortic dilatation. For 10 index cases, first-degree relatives were also available (n = 35) and underwent mutational screening for variants identified in index cases (P1, P2, P4, P6, P7, P8, P9, P14, P25, P29). Among the enrolled families, nine had at least two affected family members (all except P1). Family structures (number of affected/unaffected relatives with the genotype) are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Segregation analyses (P2, P8, P14 and P29 families).

Figure 2.

Segregation analyses (P1, P4, P6, P7, P9 and P25 families).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the BAV patients are reported in Table 1. Probands whose family members have been included in the study are marked in Table 2. The experimental protocol was approved by the Local Ethical Committee. All patients underwent genetic counseling and signed a written informed consent for diagnosis and research purposes in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of BAV patient cohort.

Table 2.

Principal phenotypic features of the 52 BAV patients.

2.2. Echocardiographic Evaluation

All echocardiographic examinations were conducted by senior cardiologists (S.N., S.C., M.P.F.), and aortic measurements were performed by S.N. BAV was diagnosed when only two cups were unequivocally identified in systole as previously described [2,15] and classified as type 1 (left and right cusps fusion) and type 2 (right and non-coronary cusp fusion). Aortic dimensions were assessed at end-diastole in the parasternal long-axis view at the sinuses of Valsalva and proximal ascending aorta by the leading edge method [15,16], and Z-scores were calculated according to age-adjusted nomograms [17]. Aortic or mitral regurgitation was evaluated and graded by multiple criteria combining color Doppler and continuous wave Doppler signals, and aortic valve stenosis was evaluated and graded by peak aortic valve velocity [15]. Echocardiographic assessment of the aortic valve calcification degree [no calcification, mild calcification (small isolated spots), moderate calcification (multiple larger spots) and severe calcification (extensive thickening and calcification of all cusps)] was also performed [18].

2.3. DNA Extraction, Custom Targeted NGS

Peripheral venous blood was collected in EDTA Vacutainer tubes and stored at −20 °C. Genomic DNA was extracted from blood samples using a FlexiGene Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The custom targeted NGS panel included 97 genes relevant in BAV, syndromic and non-syndromic aortopathy or involved in vessel or valve growth and remodeling processes (Supplementary Table S1). Genomic DNA libraries were prepared according to the SureSelectQXT protocol (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The pooled libraries were paired-end sequenced on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). An analytical pipeline developed, implemented and validated for data analysis of targeted sequencing for diagnostic/research purposes was available in our laboratory.

2.4. Alignment and Variant Calling

Fastq file quality was checked with FASTQC. Trimmed reads were aligned to the human reference genome (Human GRCh37/hg19) using BWA-MEM. Bam file quality was evaluated with Qualimap 2.2.2d. Variant calling was performed using GATK4 HaplotypeCaller in GVCF mode and the joint genotyping tool GenotypeGVCFs. Variants were annotated using VEP 99. Ninety-nine percent of targeted regions were covered. Variants were filtered according to Phred quality score (Q) ≥ 30 and minimum coverage depth of 30×. Variants were called following guidelines suggested by the Broad Institute, commonly accepted as standard and identified according to (a) MAF < 0.01; (b) potential role, according to variant classification recommendation [19], literature genotype–phenotype association data and biological plausibility; (c) in silico predictor tools; (d) type of genetic variants; (e) localization (exonic, splicing region variants); and (f) allele balance > 0.2. NGS experiments showed at least 99.8% coverage and 250–300× average coverage depth; intron regions were analyzed and covered for ±50 bp from exon–intron boundaries. In the rare cases in which low coverage depth was observed in exons or flanking regions (<0.01% of total target bases on average), Sanger technology was used to further evaluate these regions.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS package v29 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous data are given as median and IQR. The χ2 test was used to compare dichotomous data. Statistical significance was accepted at p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

The global demographic and clinical characteristics and principal phenotypic features of the 52 index BAV cases are reported in Table 1 and Table 2.

As missense, in-frame indel, frameshift, nonsense and splice site/synonymous variants suggestive of alteration of the splicing process and classified as uncertain significance variants were considered, globally in the whole BAV cohort (n = 52), 194 rare variants in 63 genes were identified. In particular, among the 194 rare variants identified, 177 (91.2%) were missense (60 classified as benign, 21 as likely benign, 92 as uncertain significance, 3 as likely pathogenic, 1 as pathogenic), 3 (1.5%) in-frame indel (likely benign/benign), 3 (1.5%) frameshift (2 classified as benign and 1 as pathogenic), 2 (1%) nonsense variants (likely pathogenic), 5 (2.6%) splice site and 4 (2.1%) synonymous variants (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rare genetic variants identified in the 52 BAV patients.

Among the genes previously described to be associated with BAV and present in our NGS gene panel, five variants in the NOTCH1 gene in four BAV patients (7.7%), four variants in the FBN1 gene in two patients (3.8%), one variant in the GATA5 gene (1.9%) and one variant in the SMAD4 gene (1.9%) were identified. Furthermore, a comprehensive evaluation of the most represented variants in the BAV cohort shows a greater burden of genetic variants in the PDIA2 gene [13 variants in 11 patients (21.1%)], LRP1 [7 variants in 7 patients (13.5%)], LTBP1 [10 variants in 9 patients (17.3%)], COL6A3 [9 variants in 8 patients (15.4%)] and LTBP2 [6 variants in 6 patients (11.5%)]; moreover, 6 patients (11.5%) carried a rare variant in CAPN2 and FN1, respectively, and 5 out of the 52 BAV patients (9.6%) carried a rare variant in the MYLK gene.

For 10 out of the 52 BAV patients (Table 3), relatives to perform segregation analyses of the variants identified in the probands were available. In particular, 9 out of the 10 probands have at least two available affected members (all except P1).

The possible contribution of PDIA2, LRP1 and CAPN2, suggested by the high prevalence in our patients of genetic variants with a potential effect on the phenotype of these loci in the whole cohort of BAV patients, was further explored through segregation analyses of identified variants in these genes in family members of P6, P25, P7 and P9 probands. In fact, for (1) PDIA2 p.Pro131Leu in the P6 family and p.Thr115Met in the P25 family, (2) LRP1 p.Val176Asp in the P7 family, (3) CAPN2 c.901+8C>G in the P9 family, segregation data are compatible with gene involvement in the clinical phenotype, even if they do not prove a causal role (Figure 2).

Moreover, data from further segregation analyses are compatible with the role of the following variants: MYH11 p.Ser1691Arg variant in the P8 family (Figure 1), TGFBR3 p.Asp426Asn, HOXA1 p.Asn269Ile and B3GAT3 p.Ala56Val in the P14 family (Figure 1) and SLC2A10 p.Ala385Gly in the P25 family (Figure 2).

Concerning the four likely pathogenetic and the two pathogenetic variants, they were identified in FBN1, MYH11, MYLK, COL6A3, ABCC6 and CBS genes in index cases without family member availability or informative families (Table 3).

In the BAV cohort, 43 patients exhibited thoracic aortic dilatation, whereas 9 did not show the presence of aortic root as well as ascending aorta dilatation (Table 1 and Table 2). Rare variant prevalence evaluation of the targeted genes according to the presence or absence of aortic dilatation showed a statistically significant higher prevalence of MYLK variants in patients without aortic dilatation than in those with dilatation (33.3% vs. 4.6%; p = 0.03).

Fifteen patients showed the presence of aortic calcification (Table 2). Among patients with calcification, a higher prevalence of CAPN2 rare variant carriers is observed if compared with those without calcification (26.7% vs. 5.4%, respectively; p = 0.05).

Among patients with stenosis, a significantly higher prevalence of VHL and AGGF1 rare variant carriers was observed with respect to those without stenosis (40% vs. 0%, p = 0.008 and 40% vs. 0%, p = 0.008, respectively).

No significant difference in rare variant prevalence in the targeted genes according to the presence of absence of aortic insufficiency was found.

Rare variant distribution according to the presence or absence of thoracic aorta dilatation, calcification, aortic insufficiency and stenosis is reported in Supplementary Table S2.

4. Discussion

In this paper, 52 consecutive BAV patients enrolled in an Italian Referral Regional (Tuscany) Center for Marfan syndrome, Heritable Thoracic Aortic Disease (HTAD) and related disorders were studied. Mutation analysis of 97 genes regarded as relevant in BAV, syndromic and non-syndromic aortopathy or involved in vessel or valve growth and remodeling processes confirms the involvement in BAV disease of NOTCH1, FBN1, GATA5 and SMAD4 genes and suggests the contribution of novel genes. In particular, according to the evidence of high-prevalence rare variants with a potential effect on the phenotype in the whole cohort of the 52 BAV patients and the further segregation analyses in the 10 BAV families, the study suggested that n = 3 genes emerge as promising candidates for association in BAV, namely PDIA2, LRP1 and CAPN2. Moreover, present data also suggest the possible contribution of rare variants in BAV complications and in particular MYLK in aortic dilatation, CAPN2 in BAV calcification and VHL and AGGF1 in valve stenosis.

The contribution of PDIA2 and LRP1 was first suggested by their high prevalence in BAV patients (21.1% PDIA2 and 13.5% LRP1 variant carriers) and investigated and supported by segregation analyses in families P6 and P25 (PDIA2) and P7 (LRP1), which evidence that these loci may be no longer excluded for association with the BAV phenotype. Moreover, in a non-negligible percentage of BAV patients (11.5%), rare variants in CAPN2 were identified. In the P9 familial case, the CAPN2 variant was also shown to segregate with the BAV phenotype, thus supporting its involvement in this phenotypic trait.

As concerns PDIA2, previous Genome-Wide Association Study data suggested its possible implication in BAV. In a cohort of 68 BAV probands and 830 control subjects, a haplotype within the AXIN1-PDIA2 locus was found to be associated with BAV [21]. Moreover, data from Dargis et al. [22] reporting targeted NGS sequencing results from 48 BAV patients showed the presence of rare and common genetic variants in the PDIA2 gene. Our data contribute to strengthening the association of PDIA2 with BAV pathogenesis. In fact, beside the identification of 13 PDIA2 rare variants in 11 BAV patients, segregation analysis carried out on P6 and P25 family members did not exclude the contribution of PDIA2 mutations (p.Pro131Leu and p.Thr115Met) in framing BAV.

Data from the present study also suggested the contribution of the LRP1 gene, encoding a multifunctional LDL receptor gene family member, in BAV predisposition; LRP1 is actually suggested to have a major role in smooth muscle cell (vSMC) proliferation control, as well as protection against atherosclerosis [23]. Moreover, a gene expression study revealed that the LRP1 gene was differentially expressed in both TAV and BAV subjects with dilation [24]. Interestingly, whole-exome sequencing analysis carried out on a cohort of 20 BAV subjects showed the presence of heterozygous missense mutations in 36 genes, also including LRP1 [25]. Moreover, data from the literature also reported LRP1 locus contribution in abdominal aortic aneurysm susceptibility [26].

Based on the abovementioned evidence, considering the different biological pathways in which LRP1 is implicated, its possible involvement in BAV should also be considered.

Rare genetic variants in the CAPN2 gene have also been identified in 6 out of the 52 (11.5%) BAV patients investigated; CAPN2 encodes one of the main calpain isoforms, calcium-dependent cysteine proteases able to cleave different structural proteins and involved in different intracellular signaling pathways. Data from the literature reported their contribution to angiotensin II-induced cardiovascular remodeling [27]. Moreover, increased protease activity in both MFS and BAV aortic aneurysm was detected [28]. Data from Werner et al. [29] also reported a significant difference in the expression of calpain-I and calpastatin, specifically inhibiting calpain-I and calpain-II proteolytic activity, in patients exhibiting ascending aorta aneurysm, thus supporting calpain involvement in aortic tissue structural alteration.

Moreover, data from the present study also showed a higher prevalence of CAPN2 rare variant carriers among BAV patients with calcification with respect to the non-calcification group. Further deepening of the CAPN2 variant effect as well as of the pathogenetic mechanisms might allow a better definition of CAPN2’s role in BAV development and complications.

Among BAV patients without available family members, a non-negligible percentage of subjects also carried rare variants in LTBP1 (17.3%), COL6A3 (15.4%), LTBP2 (11.5%) and FN1 (11.5%), thereby supporting the involvement of genes encoding TGF-β pathway components (i.e., LTBP, latent transforming growth factor β binding proteins) as well as the involvement of genes encoding collagen chains.

Moreover, rare variants in the MYLK gene, encoding myosin light chain kinase, were identified in 5 out of the 52 BAV (9.6%) patients. Although a higher percentage of MYLK rare variant carriers was present in BAV patients without aortic dilatation, gene variant classification according to ACMG guidelines [19] allows only one likely pathogenic variant (c.388C>T, p.Gln130*) to be identified in a subject with aortic dilatation (P51 subject, Table 3). Conversely, MYLK variants detected in the patient group without aortic dilatation showed a clinical significance ranging from likely benign to uncertain. Actually, the MYLK locus is associated with familial thoracic aortic aneurysm, type 7 (OMIM 613780), an autosomal dominant condition. Nevertheless, the role of the MYLK gene in the BAV phenotype should be further investigated in larger cohorts.

Among genes previously associated with BAV, five NOTCH1 mutations were found in 4 out of the 52 (7.7%) BAV patients (P1, P30, P37, P46, Table 3). NOTCH1 missense mutations were previously reported in the ClinVar/literature in subjects with Adams–Oliver syndrome 5 and/or left ventricular outflow tract malformation (LVOT) including BAV [30]. Previous data from targeted NGS studies also reported a NOTCH1 mutation prevalence among BAV-unrelated subjects ranging from 1% to 9% [22,31,32]. In the present work, a higher prevalence of NOTCH1 variants was observed in BAV patients with aortic dilatation, although the difference with respect to the patient group without aortic dilatation did not reach statistical significance. Ma et al. [32] observed among BAV patients a higher, though not statistically significant, prevalence of rare NOTCH1 variants in subjects with normal aortas than in those with aortopathy. These conflicting data on NOTCH1, due to the limited number of patients investigated in the two studies, require further confirmation in larger BAV patient cohorts.

Concerning the FBN1 gene, we found the same two missense rare variants (p.Lys2460Arg and p.Asn542Ser) in P1 and P52 (Table 3). Subject P1 represents a 45-year-old Caucasian male with a complex BAV phenotype, including thoracic aortic root and ascending aorta dilatation and connective features inconclusive for Marfan syndrome, previously reported to be investigated through a high-throughput sequencing approach [20]. In the P1 family, these variants were inherited by P1 from his mother, clinically suggestive of a fibrillinopathy responsible for a mild Marfan phenotype (Figure 2). The current study confirms this but does not add decisive new evidence regarding these specific variants. Intriguingly, subject P1 was also a carrier of variants in other genes, including NOTCH1 [20].

Data from the present study evidencing a higher prevalence of VHL and AGGF1 variants in subjects with valve stenosis also suggest the possible contribution of these loci in influencing the occurrence of this BAV complication. Actually, data from the literature show their involvement in vascular homeostasis. AGGF1 encodes an angiogenic factor involved in the modulation of neointimal formation and restenosis associated with vascular injury due to phenotypic VSMC switching mediated by the MEK-ERK-Elk signaling pathway [33]. As concerns VHL, it was previously reported that germline genetic variants in the oxygen-sensing pathway (VHL-HIF2A-PHD2-EPOR) might result in erythrocytosis, thus possibly influencing hemodynamic stress on the valve [34].

The strength of our study is the availability of families for segregation analyses and homogeneity of clinical/instrumental evaluation, whereas the limitations are the low number of subjects investigated in order to reach a strong statistical power and unapplied correction for multiple comparisons, as well as the lack of a control group. Moreover, a further study limitation lies in the impossibility for NGS technology to detect large insertions/deletions in the target regions.

In conclusion, our data deriving from NGS targeted gene analysis and from segregation analyses where possible support the contribution of further loci (PDIA2, LRP1, CAPN2) beyond those still known (NOTCH1, FBN1, GATA5, SMAD4) to be previously associated or suspected to be associated with BAV. Nonetheless, the effect of modulatory loci that could be able to further modulate patient clinical complications (MYLK, CAPN2, VHL and AGGF1), thus contributing to delineate the genetic profile underlying the BAV phenotype, should also be considered. Nevertheless, the findings concerning MYLK, CAPN2, VHL and AGGF1 genes role are exploratory and should be interpreted with caution, given the small number of events, multiple testing and the lack of correction for these tests. Moreover, variable penetrance of the trait should be responsible for lacking information from segregation analysis. Actually, a “negative” segregation with incomplete penetrance does not necessarily exclude pathogenicity; conversely, cosegregation in a small series of relatives does not represent decisive evidence.

Our results underline the complexity of clinical and genetic diagnosis in traits considered monogenic such as BAV but characterized by variability in disease phenotypic expression (incomplete penetrance), as well as the contribution of different major and modifier genes due to low/moderate or high effect genetic variants in complication development. Further evaluation in larger cohorts representative of the general BAV population as well as functional studies might allow further confirmation of the present data.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diagnostics16010104/s1, Supplementary Table S1: Custom targeted 97 genes NGS panel details; Supplementary Table S2: Rare variants according to the presence or absence of thoracic aorta dilatation, calcification, aortic insufficiency and stenosis.

Author Contributions

B.G., E.S. and G.P. were responsible for conception or design of the work; G.P., M.B., M.P.F., S.C., S.N., F.G., E.F. and A.M.G. contributed to data collection and data analysis interpretation; R.D.C., S.S., A.K., L.S., G.B., R.O. and E.S. contributed to genetic profile characterization; B.G., E.S. and R.D.C. drafted the article; B.G., E.S. and R.M. critically revised the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence institutional funding (RICATEN2024 and RICATEN2025 Prof. Betti Giusti).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study (Bicuspid Aortic Valve project) was approved by Regional ethical committee [Comitato Etico Regione Toscana—Area Vasta Centro (CEAVC)] (n.11114_bio, approval date: 12 September 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (E.S.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Prakash, S.K.; Bossé, Y.; Muehlschlegel, J.D.; Michelena, H.I.; Limongelli, G.; Della Corte, A.; Pluchinotta, F.R.; Russo, M.G.; Evangelista, A.; Benson, D.W.; et al. A roadmap to investigate the genetic basis of bicuspid aortic valve and its complications: Insights from the International BAVCon (Bicuspid Aortic Valve Consortium). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nistri, S.; Porciani, M.C.; Attanasio, M.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Pepe, G. Association of Marfan syndrome and bicuspid aortic valve: Frequency and outcome. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012, 155, 324–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran, A.C.; Frescura, C.; Sans-Coma, V.; Angelini, A.; Basso, C.; Thiene, G. Bicuspid aortic valves in hearts with other congenital heart disease. J. Heart Valve Dis. 1995, 4, 581–590. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, N.D.; Crawford, T.; Magruder, J.T.; Alejo, D.E.; Hibino, N.; Black, J.; Dietz, H.C.; Vricella, L.A.; Cameron, D.E. Cardiovascular operations for Loeys-Dietz syndrome: Intermediate-term results. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 153, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforest, B.; Nemer, M. Genetic insights into bicuspid aortic valve formation. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 180297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, B.; Sticchi, E.; De Cario, R.; Magi, A.; Nistri, S.; Pepe, G. Genetic Bases of Bicuspid Aortic Valve: The Contribution of Traditional and High-Throughput Sequencing Approaches on Research and Diagnosis. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoorshahi, S.; Yetman, A.T.; Bissell, M.M.; Kim, Y.Y.; Michelena, H.I.; De Backer, J.; Mosquera, L.M.; Hui, D.S.; Caffarelli, A.; Andreassi, M.G.; et al. Whole-exome sequencing uncovers the genetic complexity of bicuspid aortic valve in families with early-onset complications. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 111, 2219–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelena, H.I.; Khanna, A.D.; Mahoney, D.; Margaryan, E.; Topilsky, Y.; Suri, R.M.; Eidem, B.; Edwards, W.D.; Sundt, T.M., 3rd; Enriquez-Sarano, M. Incidence of aortic complications in patients with bicuspid aortic valves. JAMA 2011, 306, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabagi, H.; Levine, D.; Gharibeh, L.; Camillo, C.; Castillero, E.; Ferrari, G.; Takayama, H.; Grau, J.B. Implications of Bicuspid Aortic Valve Disease and Aortic Stenosis/Insufficiency as Risk Factors for Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 24, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, M.D.; Urbania, T.H.; Yu, J.P.; Chitsaz, S.; Tseng, E. Incidental aortic valve calcification on CT scans: Significance for bicuspid and tricuspid valve disease. Acad. Radiol. 2012, 19, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepe, G.; Giusti, B.; Colonna, S.; Fugazzaro, M.P.; Sticchi, E.; De Cario, R.; Kura, A.; Pratelli, E.; Melchiorre, D.; Nistri, S. When should a rare inherited connective tissue disorder be suspected in bicuspid aortic valve by primary-care internists and cardiologists? Proposal of a score. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2021, 16, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahanian, A.; Beyersdorf, F.; Praz, F.; Milojevic, M.; Baldus, S.; Bauersachs, J.; Capodanno, D.; Conradi, L.; De Bonis, M.; De Paulis, R.; et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 561–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praz, F.; Borger, M.A.; Lanz, J.; Marin-Cuartas, M.; Abreu, A.; Adamo, M.; Ajmone Marsan, N.; Barili, F.; Bonaros, N.; Cosyns, B.; et al. 2025 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 4635–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VASCERN. HTAD-WG. Available online: https://vascern.eu/group/heritable-thoracic-aortic-diseases-2/clinical-decision-support-tools/clinical-practice-guidelines/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Nistri, S.; Basso, C.; Marzari, C.; Mormino, P.; Thiene, G. Frequency of bicuspid aortic valve in young male conscripts by echocardiogram. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 96, 718–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, M.J.; Devereux, R.B.; Kramer-Fox, R.; O’Loughlin, J. Two-dimensional echocardiographic aortic root dimensions in normal children and adults. Am. J. Cardiol. 1989, 64, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campens, L.; Demulier, L.; De Groote, K.; Vandekerckhove, K.; De Wolf, D.; Roman, M.J.; Devereux, R.B.; De Paepe, A.; De Backer, J. Reference values for echocardiographic assessment of the diameter of the aortic root and ascending aorta spanning all age categories. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 114, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenhek, R.; Binder, T.; Porenta, G.; Lang, I.; Christ, G.; Schemper, M.; Maurer, G.; Baumgartner, H. Predictors of outcome in severe, asymptomatic aortic stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sticchi, E.; De Cario, R.; Magi, A.; Giglio, S.; Provenzano, A.; Nistri, S.; Pepe, G.; Giusti, B. Bicuspid Aortic Valve: Role of Multiple Gene Variants in Influencing the Clinical Phenotype. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 8386123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooten, E.C.; Iyer, L.K.; Montefusco, M.C.; Hedgepeth, A.K.; Payne, D.D.; Kapur, N.K.; Housman, D.E.; Mendelsohn, M.E.; Huggins, G.S. Application of gene network analysis techniques identifies AXIN1/PDIA2 and endoglin haplotypes associated with bicuspid aortic valve. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargis, N.; Lamontagne, M.; Gaudreault, N.; Sbarra, L.; Henry, C.; Pibarot, P.; Mathieu, P.; Bossé, Y. Identification of Gender-Specific Genetic Variants in Patients With Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016, 117, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, P.; Herz, J. Signaling through LRP1: Protection from atherosclerosis and beyond. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011, 81, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkersen, L.; Wågsäter, D.; Paloschi, V.; Jackson, V.; Petrini, J.; Kurtovic, S.; Maleki, S.; Eriksson, M.J.; Caidahl, K.; Hamsten, A.; et al. Unraveling divergent gene expression profiles in bicuspid and tricuspid aortic valve patients with thoracic aortic dilatation: The ASAP study. Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jin, Q.; Hou, S.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, L.; Pan, W.; Ge, J.; Zhou, D. Identification of recurrent variants implicated in disease in bicuspid aortic valve patients through whole-exome sequencing. Hum. Genom. 2022, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bown, M.J.; Jones, G.T.; Harrison, S.C.; Wright, B.J.; Bumpstead, S.; Baas, A.F.; Gretarsdottir, S.; Badger, S.A.; Bradley, D.T.; Burnand, K.; et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with a variant in low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 89, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letavernier, E.; Perez, J.; Bellocq, A.; Mesnard, L.; de Castro Keller, A.; Haymann, J.P.; Baud, L. Targeting the calpain/calpastatin system as a new strategy to prevent cardiovascular remodeling in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilop, C.; Aregger, F.; Gorman, R.C.; Brunisholz, R.; Gerrits, B.; Schaffner, T.; Gorman, J.H., 3rd; Matyas, G.; Carrel, T.; Frey, B.M. Proteomic analysis in aortic media of patients with Marfan syndrome reveals increased activity of calpain 2 in aortic aneurysms. Circulation 2009, 120, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, I.; Schack, S.; Richter, M.; Stock, U.A.; Ahmad, A.E.-S.; Moritz, A.; Beiras-Fernandez, A. The role of extracellular and intracellular proteolytic systems in aneurysms of the ascending aorta. Histol. Histopathol. 2016, 31, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Riley, M.F.; McBride, K.L.; Cole, S.E. NOTCH1 missense alleles associated with left ventricular outflow tract defects exhibit impaired receptor processing and defective EMT. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1812, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonachea, E.M.; Zender, G.; White, P.; Corsmeier, D.; Newsom, D.; Fitzgerald-Butt, S.; Garg, V.; McBride, K.L. Use of a targeted, combinatorial next-generation sequencing approach for the study of bicuspid aortic valve. BMC Med. Genom. 2014, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Li, Z.; Mohamed, M.A.; Liu, L.; Wei, X. Aortic root aortopathy in bicuspid aortic valve associated with high genetic risk. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Hu, Z.; Ye, J.; Hu, C.; Song, Q.; Da, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, C.; Chen, Q.; et al. Targeting AGGF1 (angiogenic factor with G patch and FHA domains 1) for Blocking Neointimal Formation After Vascular Injury. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangat, N.; Szuber, N.; Tefferi, A. JAK2 unmutated erythrocytosis: 2023 Update on diagnosis and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 965–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.