Abstract

Background: Lung cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Artificial intelligence (AI) holds significant potential roles in enhancing the detection of lung nodules through chest X-ray (CXR), enabling earlier diagnosis and improved outcomes. Methods: Papers were identified through a comprehensive search of the Web of Science (WOS), Scopus, and Ovid Medline databases for publications dated between 2020 and 2024. Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, 34 studies that met the inclusion criteria were selected for quality assessment and data extraction. Results: AI demonstrated sensitivity rates of 56.4–95.7% and specificities of 71.9–97.5%, with the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) values between 0.89 and 0.99, compared to radiologists’ mean area under the curve (AUC) of 0.81. AI performed better with larger nodules (>2 cm) and solid nodules, showing higher AUC values for calcified (0.71) compared to non-calcified nodules (0.55). Performance was lower in hilar areas (30%) and lower lung fields (43.8%). A combined AI-radiologist approach improved overall detection rates, particularly benefiting less experienced readers; however, AI showed limitations in detecting ground-glass opacities (GGOs). Conclusions: AI shows promise as a supplementary tool for radiologists in lung nodule detection. However, the variability in AI results across studies highlights the need for standardized assessment methods and diverse datasets for model training. Future studies should focus on developing more precise and applicable algorithms while evaluating the effectiveness and cost-efficiency of AI in lung cancer screening interventions.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Lung cancer remains a significant global public health issue, with substantial variation in incidence and mortality rates across different regions. While the American Cancer Society has reported a decrease in the cancer burden in the United States, China is experiencing a shift in its cancer burden epidemiology, increasingly resembling that of the United States [1]. It is estimated that approximately one-quarter of all cancers could be prevented if risk factors such as tobacco smoking and obesity were effectively controlled [2]. However, early diagnosis of the disease is crucial, as about 93% of patients are diagnosed with stage III and IV lung cancer, with an average survival time of just 18 weeks after diagnosis [3].

The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) demonstrated that lung cancer screening has the potential to enable early detection of the disease. The study reported a 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality among participants who underwent low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) compared to those who underwent chest radiography screening [4]. However, the implementation patterns and benefits of LDCT screening vary significantly across different groups. Factors such as race, ethnicity, rurality, and socioeconomic status have emerged as major determinants of access and use [5]. Notably, the rural population undergoes fewer LDCT scans compared to the urban population [6]. In the ASEAN region, the scarcity of imaging equipment compared to global standards exacerbates these disparities [7]. Geographic accessibility is another constraint, with 5% of the target population lacking a screening facility within 40 miles, and no facilities available in rural areas at any distance [8].

Thus, new methods for interpreting chest X-rays (CXRs) using AI have been developed to address the disparities in lung cancer screening. Computer-assisted detection (CAD) developed through AI has enhanced lung cancer nodule detection on chest X-rays (CXRs) for general physicians and radiologists, leading to increased accuracy, specificity, and positive predictive value (PPV) [9]. The authors of [10] demonstrated that applying a deep learning-based automatic detection algorithm (DLAD) to CXRs improved the average area under the alternative free-response receiver operating characteristic curve for all observers from 0.67 to 0.76. The DLAD also helped detect more lung cancers (53% vs. 40%, p < 0.001) [10]. The performance of AI models in diagnosing CXRs has been very impressive, with median area under the curve (AUC) values ranging from 0.979 [11] to 0.983 [12] for detecting CXRs with major thoracic diseases.

While AI shows great promise in lung cancer screening, several significant challenges impact its implementation. Technical limitations include AI’s difficulty in detecting small nodules and nodules with varying densities [13]. Additionally, AI systems often underperform when applied to populations that differ from the datasets used for training [14]. Poor image quality [15] and complex anatomical structures [16] further compromise performance, particularly in detecting nodules that overlap with other structures. Moreover, AI accuracy decreases with increasing case complexity [17], and challenges arise in comparing current images with past radiographs [18]. These implementation challenges highlight the need for enhanced AI systems capable of delivering consistent performance across diverse clinical settings and patient populations.

However, it is also important to realize that AI in medical imaging was never meant to replace radiologists but rather to serve as a tool that can help them. Research revealed that AI sensitivity for detecting early-stage lung cancer can increase to 83.3% when combined with radiologists [19]. The application of AI in CXRs has the potential to help in the early identification of lung cancer and lower the mortality rate. Furthermore, AI-assisted CXR analysis could help to address some of the disparities in lung cancer screening. It could provide a less costly, potentially more available first-screening test that might be available to regions that have limited access to LDCTs or few radiologists.

1.2. Objective of the Review

The primary objective of this systematic literature review (SLR) is to comprehensively assess the performance of AI algorithms compared to radiologists in detecting lung nodules in CXRs. This review aims to:

- Evaluate and compare the performance of AI algorithms against radiologists in detecting lung nodules in CXRs.

- Analyze performance variations of AI algorithms and radiologists based on nodule sizes, morphology, and locations of the nodules.

- Identify and examine factors contributing to discrepancies between AI and radiologist interpretations in lung nodule detection.

- Investigate patterns of missed lung nodules when comparing AI algorithms with radiologists in chest radiograph interpretation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reference Source (PRISMA)

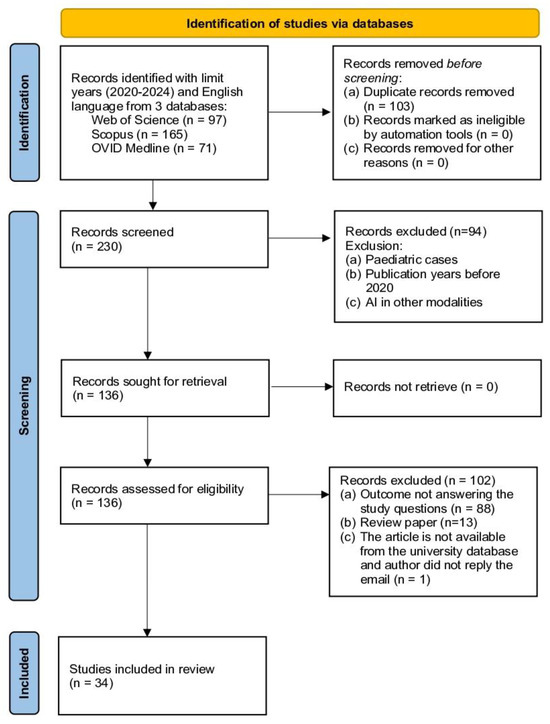

This study adopts the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) as the primary reference source (Figure 1). PRISMA, developed by the authors of [20], was selected due to its advantages in several aspects. Firstly, PRISMA provides researchers with clear guidelines for producing and writing SLR articles. The PRISMA checklist will guide the documentation of search strategies, study selection criteria, and data extraction processes, ensuring transparency and completeness in reporting. In addition, PRISMA supports quality control of the selected articles [20]. Referring to PRISMA has enabled researchers to develop this SLR based on four main methodological processes: namely (1) formation of research questions, (2) systematic search strategy (identification, screening, and eligibility), (3) article quality assessment, and (4) data extraction and analysis. By following PRISMA guidelines, this review aims to comprehensively present the methodological report on the current state of the study, allowing readers to evaluate the findings and their reliability for practical application.

Figure 1.

Study selection process following PRISMA guidelines.

2.2. Formation of Research Questions

Referring to the mnemonic PICO (Problem, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome), the research question for this SLR was formulated. PICO is particularly suitable for medical investigations as it offers a clear and systematic means of drawing questions, which, in turn, will increase the focus and relevance of the investigation [21]. PICO improves the efficiency of literature searches, the solidity of study designs, and the dependability of evidence syntheses. In this SLR, P refers to lung cancer, I refers to the use of AI in chest radiographs, C refers to a radiologist, and O refers to lung nodule detection. This reference to the mnemonic PICO has helped the researcher to produce these research questions and the motivation behind these questions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Research questions and motivations for evaluating AI performance in CXRs versus radiologists in lung nodule detection.

2.3. Systematic Search Strategy

The next process involves a systematic search strategy. This process helps researchers conduct a comprehensive material search, and it has three main steps: identification, screening, and eligibility. The search utilized three electronic databases, namely Web of Science (WOS), Scopus, and Ovid Medline.

2.3.1. Identification

The first author conducted the initial identification process to determine suitable keywords for this SLR. Based on the set of research questions formed, some keywords have been selected, such as “lung cancer”, “pulmonary cancer”, “lung nodule”, “pulmonary nodule”, “artificial intelligence”, “chest x-ray”, “chest radiograph”, and “radiologist”. Next, to maximize the number of articles that can be obtained, researchers have searched for synonyms of related words and variations to the keywords. These have been searched in two main sources: referring to the keywords of previous studies and keywords suggested by databases such as Ovid Medline.

This process has produced some additional keywords such as “lung neoplasm”, “pulmonary neoplasm”, “deep learning”, “machine intelligence”, “computer vision system”, “computational intelligence”, and “thoracic radiography”. In addition, researchers have also produced search strings for this SLR based on functions such as Boolean Operator, Phrase Searching, Truncation, Wild Card, and Field Code. The final search was performed on 23 July 2024. The search brought a total of 392 documents identified from the three databases (WOS Core Collection = 116, Scopus = 168, Ovid Medline = 108). The number was reduced to 333 articles using language (English) and the publication year (2020–2024) filters (WOS 97, Scopus 165, Ovid Medline 71). A total of 230 articles were selected after the duplication was removed and taken to the next process, which was screening.

2.3.2. Screening

Screening is a process of filtering articles comprising several standards that the researcher uses to choose articles of interest. Two reviewers were independently involved in the screening process. Among the 230 articles that were identified and screened, 94 articles were removed based on the exclusion criteria, including pediatric cases, papers published before 2020, and articles discussing AI in other medical imaging techniques. From this screening process, there was a reduction in the articles to 136 for further determination of their relevance to the study.

2.3.3. Eligibility

The eligibility process for the selection of articles is another important step of the systematic review in which the researchers take their time to assess the suitability of the selected articles about the objectives of the study. The process includes the evaluation of the title and abstract of each article and, if required, the main text. The first step is to check and ensure that the chosen articles are relevant to the research objectives and questions. In this review, the eligibility screening resulted in the removal of 102 articles for various reasons: they did not achieve the aims of the study, review articles rather than primary research, and the full text of the articles was not available in the university’s database. After the elimination process based on these criteria, 34 articles were considered to meet the inclusion criteria in the next step of the review, which was the quality assessment of the articles that were selected.

2.4. Evaluation of Article Quality

Next, the 34 articles selected earlier were evaluated for their quality. This process was carried out by the lead author of this SLR and assisted by two co-authors. The evaluation method by the authors of [22] was used to determine the selected articles. This method is based on six main criteria, which are as follows:

QA1. Is the purpose of the study clearly stated?

QA2. Is the interest and the usefulness of the work presented?

QA3. Is the study methodology established?

QA4. Are the concepts of the approach clearly defined?

QA5. Is the work compared and measured with other similar work?

QA6. Are the limitations of the work mentioned?

A scoring system was used to determine whether the selected articles were of good quality. Every time the researcher gave a yes answer to the evaluated criteria, 1.0 marks were given. If the researcher chooses an incomplete answer, 0.5 marks are given. If the researcher chooses the answer no, zero marks will be given. The condition for articles to be selected in this SLR is that the minimum score recorded should reach at least 3.0 and above [22]. Based on this process, the researchers found that all 34 articles that were evaluated passed the minimum score of 3.0 and were selected to be reviewed.

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two reviewers independently reviewed the selected articles and extracted relevant data systematically. Most of the data collection was conducted on the results and discussion sections of the selected articles, with other sections examined where the need for context or clarity exists. The authors have utilized Petal.ai to assist with initial data extraction and manually validate all extracted data points to ensure accuracy. Data synthesis was conducted using a narrative descriptive approach since the studies included in the review are heterogeneous. The findings were organized into four main themes aligned with our research objectives. Data from all independent research were summed up in a common table for further comparison and analysis. A meta-analysis was not conducted because the study was rather diverse in terms of study designs, populations, and outcome measures. The authors used Claude.ai to improve clarity and readability under the authors’ supervision and final approval.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Study

The number of research publications in AI-assisted lung nodule detection on chest radiographs, especially from 2020 to 2024, in which the number of articles has grown from 6 in 2020 to 13 in 2023 (Table 2). This SLR synthesizes the cross-national trends (Table 3) and findings from work conducted throughout this period (Table 4). These studies were conducted with participants from various geographical areas, such as Asia, including South Korea [13,17,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33], Japan [16,18,34], Taiwan [35,36], and India [14,37,38]; Egypt [39], the United States [15,37,40,41], Israel [42], and Australia [43]; and European countries, such as Germany [44], France [45], The Netherlands [46,47], the United Kingdom [48,49], and Switzerland [50].

Table 2.

Publication trends in AI-assisted lung nodule detection research.

3.2. Study Design and Population

From the analysis of 34 selected articles, the majority employed retrospective cross-sectional study designs (n = 26) [15,16,17,18,24,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,41,42,43,44,45,46,48,49]. The remaining studies utilized various other methodologies, including retrospective cohort studies (n = 3) [25,40,47] and retrospective case-control studies (n = 2) [13,27].

Out of all of these study designs, only one used a randomized control trial approach [23], one conducted an experimental study using mannequin-like models or anthropomorphic phantoms [50], and one used a prospective cross-sectional study design [14]. The distribution of study designs shows that authors employed cross-sectional studies as the primary source of AI performance assessment for lung detection in chest radiographs.

Variations in sample size and the representation of study subjects were observed in the 34 studies under analysis. The largest study was conducted on 759,611 chest radiographs of 538,390 patients in five regional centers from India [38], and other select studies were conducted on 100–300 participants [24,27,35]. Some of the large sample studies sourced participants from health screenings, with 10,476 participants from a tertiary hospital [23] and 6452 participants from a healthcare screening center [25]. Control subjects were generally selected using case-control studies, like in one study with 50 subjects of lung cancer patients and 50 controls [27] and another one with 168 patients in case groups and 50 controls [13]. Certain investigations targeted higher-risk people from NLST [15] or patients with lung cancer confirmed pathologically [18].

The studies used different criteria for defining the populations they included and excluded from their research. The majority of studies involved patients who were 18 years of age and older [23,26,35,39], and a few of them were designed exclusively for patients of a certain age, namely 55–74 years, in the case of lung cancer [15]. Some of the studies confirmed nodules by CT scans or pathology [16,28,30,33], while others excluded cases according to their specific characteristics, such as extensive infiltrative lesions [31], poor image quality [39], or multiple nodules [33]. Some investigations included data collected from more than one institution or source, such as more than thirty-five centers in India [14], seven medical centers in The Netherlands [47], national institutions, and public datasets [34,36].

Table 3.

Characteristics of selected articles.

Table 3.

Characteristics of selected articles.

| Author and Year | Country | Study Design | Study Population | Study Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nam et al., 2020 [13] | Republic of Korea | Retrospective case-control study | 168 patients (mean age 71.9 ± 9.5 years) with 187 initially undetected lung cancer nodules, plus 50 normal controls; CT or X-ray validated; from March 2017 until December 2018 | A single center |

| Sim et al., 2020 [30] | Republic of Korea | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 800 radiographs (200 per center: 150 cancer cases, 50 normal); from October 2015 until September 2017 | Four tertiary hospitals |

| Lee et al., 2020 [32] | Republic of Korea | Retrospective cross-sectional study | Two cohorts: validation (10,289 X-rays from 10,206 individuals) and screening (100,576 X-rays from 50,098 individuals) | Seoul National University Hospital |

| Koo et al., 2020 [33] | Republic of Korea | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 378 patients (61% male; mean age 61.4 years) with ≤three pathologically proven nodules; excluding nodules < 5 mm or calcified; from January 2016 until December 2018 | Tertiary hospital |

| Majkowska et al., 2020 [38] | India | Retrospective cross-sectional study | Two datasets: DS1 (759,611 X-rays from 538,390 patients) with natural prevalence; ChestX-ray14 (112,120 X-rays from 30,805 patients) enriched for abnormalities | Five Indian centers (DS1) and NIH database (ChestX-ray14) |

| Yoo et al., 2020 [15] | United States | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 5485 high-risk smokers (age 55–74 years; ≥30 pack-years; 55.2% male) receiving three annual screenings; from August 2002 until April 2004 | NLST multicenter trial (21 sites) |

| Teng et al., 2021 [35] | Taiwan | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 100 subjects with CXR (47 with CT-validated nodules or masses, 53 normal); mean age 55.07 ± 13.80 years | A single center |

| Yoo et al., 2021 [41] | United States | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 519 screening X-rays from 294 patients (98 cancer cases, 196 controls); from August 2002 until April 2004 | NLST trial dataset |

| Homayounieh et al., 2021 [44] | Germany | Retrospective cross-sectional study | Adult patients of both genders with PA chest radiographs; including cases with nodules, non-nodular abnormalities, and normal findings | Two sites (A and B) |

| Tam et al., 2021 [49] | United Kingdom | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 400 cases (200 tumors, 200 controls); mean ages 72.6 and 61.8 years; seven years retrospective review | NHS setting |

| Peters et al., 2021 [50] | Switzerland | Experiment study | 61 chest phantoms with 140 solid lung nodules were placed in artificial lung parenchyma (53 phantoms with lung nodules and eight without nodules). | A phantom study using PACS-workstation |

| Nam et al., 2022 [25] | Republic of Korea | Retrospective cohort study | 6452 health checkup participants (52% male; mean age 57.6 ± 13.0 years); a subset of 3073 with CT validation | Seoul National University Healthcare Screening Center |

| Bae et al., 2022 [31] | Republic of Korea | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 111 patients with PA chest radiographs including 49 patients with 83 pulmonary nodules; excluding complex pathologies and CT-only visible nodules; from April 2016 until December 2019 | A single center |

| Chiu et al., 2022 [36] | Taiwan | Retrospective cross-sectional study | Adults (≥20 years) with single lung nodule confirmed by biopsy/resection; plus, cases from four external datasets; from 2011 until 2014 | Taipei Veterans General Hospital |

| Kaviani et al., 2022 [37] | United States | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 2407 adults (≥21 years; 1248 males; mean age 39 years); de-identified CXR data; from 2015 until 2021 | Eight sites (three in India, five in the US); including quaternary and community hospitals |

| Govindarajan et al., 2022 [14] | India | Prospective cross-sectional study | 65,604 CXRs (median age 42 years); PA/AP views; excluding incomplete/artifact cases | 35 centers across Six Indian states |

| Ahn et al., 2022 [40] | United States | Retrospective cohort study | Adult patients with specific radiograph findings (pneumonia, nodules, pneumothorax, pleural effusion) | Deaconess Medical Centre and Massachusetts General Hospital |

| Nam et al., 2023 [23] | Republic of Korea | Randomized control trial | 10,476 adults (>18 years) undergoing chest radiography; median age 59 years; 5121 men; from June 2020 until December 2021 | Tertiary hospital health screening center |

| You et al., 2023 [24] | Republic of Korea | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 300 patients: 100 normal cases (50% male, mean age 46.5 years) and 200 with pulmonary nodules (57% male, mean age 60.0 years) | A single tertiary hospital |

| Hwang et al., 2023 [26] | Republic of Korea | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 73 first-visit outpatients (median age 70 years) with AI-detected incidental nodules; excluding known thoracic cases | Hospital outpatient clinic |

| Huh et al., 2023 [27] | Republic of Korea | Retrospective case-control study | 100 cases (50 pathologically confirmed lung cancers, 50 normal); December 2015 until February 2021 | Seoul National University Hospital (tertiary) |

| Kim et al., 2023 [28] | Republic of Korea | Retrospective cross-sectional study | Training set (n = 998; 54% male; mean age 54.2 years) plus two validation sets (n = 246 and n = 205); including normal and nodule cases; from November 2015 until July 2019 | Severance Hospital, Pusan National University Hospital and Dongsan Medical Centre |

| Kwak et al., 2023 [29] | Republic of Korea | Retrospective cross-sectional study | Patients with incidentally detected, pathologically proven resectable lung cancer; referred from various departments; from March 2020 until February 2022 | A single center |

| Lee et al., 2023 [17] | Republic of Korea | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 120 cases (60 biopsy-proven cancers from 5647 registry, 60 controls); expert-annotated with CT validation; from December 2015 until February 2021 | Seoul National University Hospital, Korea |

| Ueno et al., 2023 [16] | Japan | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 388 patients with suspected lung cancer; required both CT and CXR (PA view) within one-month intervals; from June 2020 until May 2022 | Single institution, |

| Higuchi et al., 2023 [34] | Japan | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 5800 CXRs total: 800 from Fukushima (50% normal, 50% nodules) and 5000 from the NIH dataset | Fukushima health centre and NIH database |

| Farouk et al., 2023 [39] | Egypt | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 150 adults with varied lung pathologies; requiring both X-ray and CT; excluding poor-quality images and complex cases; from May 2021 until July 2022 | Ain Sham University |

| Tang et al., 2023 [43] | Australia | Retrospective cross-sectional study | Volunteer radiologists evaluating three AI interfaces vs. no AI in paired-reader design | Royal Melbourne Hospital |

| Bennani et al., 2023 [45] | France | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 500 patients (52% female; mean age 54 ± 19 years) with paired CXR and CT within 72 h; From emergency, inpatient, and day hospital settings; from January 2010 until December 2020 | Cochin Hospital, Paris, France |

| Maiter et al., 2023 [48] | United Kingdom | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 5722 radiographs from 5592 adults (53.8% female; median age 59 years); from July 2020 until February 2021 | Sheffield Teaching Hospitals (tertiary) |

| Hamanaka et al., 2024 [18] | Japan | Retrospective cross-sectional study | Patients who underwent malignant lung tumor resection; from November 2021 until July 2023 | Shin-Yurigaoka General Hospital |

| Kirshenboim et al., 2024 [42] | Israel | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 683 chest radiographs from an initial pool of 50,286; excluding interpreted cases and duplicates | A single center |

| Topff et al., 2024 [46] | The Netherland | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 25,104 radiographs from 21,039 adults (≥18 years; mean age 61.1 ± 16.2 years); Institution 1 (April 2021–February 2022) and Institution 2 (January–December 2018) | Two institutions |

| van Leeuwen et al., 2024 [47] | The Netherland | Retrospective cohort study | Two cohorts: 95 hand radiographs (age range 0–18 years; from January 2017–January 2022) and 140 chest radiographs (January 2012–May 2022); CT-validated reference standard | Seven Dutch hospitals |

3.3. Performance in Lung Nodule Detection of AI Algorithms and Radiologists

Numerous studies demonstrate that AI algorithms are more sensitive than radiologists, with similar or slightly lower specificities in lung nodule detection [13,23,40]. The authors of [13] reported that AI has a significantly higher sensitivity (70% vs. 47%) and specificity (94% vs. 78%), as well as a significantly higher area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) (0.899 vs. 0.634–0.663) compared to the radiologist. Similarly, another study reported superior AI sensitivity of 56.4% compared to 23.2% of radiologists, while both had relatively high specificity of 99.0% and 98.2%, respectively [23]. Additional analysis of the AI also indicated impressive AUC, where one study showed an AUC of 0.99 [32] while the authors of [37] also demonstrated a high AUC of 0.935 for missed findings. These improvements were particularly perceived to be significant in the identification of smaller nodules and those located in the ‘‘danger zone’’ [18,24].

However, a more detailed comparison of other studies shows variation in AI performance. This variability was described by [26] that depending on the specific model and data characteristics, AI sensitivities can vary from 44.1% to 95.7% and specificity from 71.9% to 97.5%. Variability in performance has also been observed for the various types of nodules, including a study that reported an AUC of 0.71 on calcified nodules but only 0.55 on non-calcified clinically important nodules [37]. This variability is further demonstrated across different studies. The authors of [28] also showed that the sensitivity of the AI model was 91.5%, in contrast to the mean sensitivity of radiologists at 77.5%, whereas the authors of [36] suggested that the sensitivity of AI was 79% with 3.04 FPs per image compared to the pooled radiologists’ sensitivity of 76%.

In radiograph classification, the sensitivity of AI was 53.4%, and specificity was 84.3%, while the performance of radiologists resulted in 38.8% sensitivity and 94.1% specificity [25]. Overall, CXR classification AUC was achieved at 0.890 by AI, 0.816 by radiologists, and a combined 0.866 [39]. However, one study reported lower values of AI sensitivity of 35% compared to the pooled radiologists’ sensitivity of 50% [50]. The use of AI systems alone could be insufficient and will be prone to over, or misdiagnosis in some of the studies [42]. Nevertheless, the most effective use of the AI system is in combination with radiologist interpretation [30,49].

The integration of AI with radiologists demonstrates an enhanced diagnostic performance. Several studies that described AI as a second reader or assistant tool show that the performance advantage was higher for junior readers [33,41,44]. The authors of [33] and [49] identified an increase in radiologist sensitivity from 78 to 91% and from 88.6 to 93.9%, respectively. Another study reported that the sensitivity ranges from 38.8 to 45.1% [25], while the authors of [44] noted that the sensitivity mean of junior radiologists increases from 40 to 52% with the help of AI. The previous studies highlighted that by implementing the AI model, the sensitivity of radiologists has risen from 77.5% to 92.1% [28]. When applying per nodule analysis, the AUC of AI was 0.875, compared to the radiologist’s AUC of 0.772 and a combined AUC of 0.834 [39].

3.4. AI and Radiologist Performance Across Nodule Size, Morphological Type, and Location

A study found AI improved the identification of actionable lung nodules, specifically around the missed small-sized nodules [23]. Specifically, AI was 45% accurate in identifying nodules under 1 cm in size, while human readers were only 25% accurate [13]. AI algorithms demonstrated higher accuracy with nodules of higher visibility scores, especially when nodules exceeded 2 cm [24]. However, it was found that DLAD systems improved when detecting nodules larger than 15 mm [16]. The clinical data showed that, on average, resected lung cancers were 2.6 cm in size [29].

The ability to detect lung nodules also depends on the morphological characteristics of the nodules. Several studies included nodules of various types, such as solid, part-solid, and ground-glass opacity (GGO) [16,29,33]. DLAD systems reported significantly higher sensitivity for all the solid nodules compared with part-solid and pure GGNs [16]. For calcified nodules, AI systems had higher AUC values of 0.71 than non-calcified clinically important nodules (AUC 0.55) [37]. However, both AI and radiologists have difficulty detecting GGO-predominant nodules due to their subtle radiographic features [33]. Although part-solid nodules have diagnostic challenges, a study shows that AI can detect these lesions, including invasive adenocarcinomas measuring 0.75 cm [29].

The detection performance also differentiated significantly according to the location of nodules within the chest radiograph. Studies revealed AI has higher sensitivity and specificity in detecting apical lung nodules than para-mediastinal or retro-diaphragmatic locations, which are considered “danger zones” (DZ) [24]. The authors of [13] identified that the AI system could detect lung nodules better in the apical and hilar regions than the radiologist, but both have difficulty in retro-cardiac and retro-diaphragmatic areas, with only 21% to 22% of these lesions being detected. The detection rate was overall lower in the lower lung fields at 43.8% and hilar regions at 30% [18]. In particular, smooth, well-marginated nodules without marked overlap of the internal structure were found to have significantly higher detection rates [33]. It was also found that central nodules were particularly challenging for AI-CAD systems, where sensitivity was found to be as low as 9% as compared to 64% for peripheral nodules [50].

The presence of overlapping anatomical structures provided the greatest impact on the accuracy of detection, both in the AI systems and for human readers. It was further found that 86.4% of the cases were nodules missed due to being masked by other lesions, and the majority of them were hidden by bony structures such as ribs and costochondral junctions [33]. Both AI systems and radiologists consistently struggled with nodules obscured by various anatomical structures such as bone, heart, diaphragm, and mediastinum [27]. Particularly, difficulties were observed in areas contacting the left clavicle [41], behind the heart, and hilum [49]. Anatomical overlap was most prominent in the frontal view, where nodules could be masked by anatomical normal structures [32]. To mitigate these issues, a deep learning-based synthesized bone-suppressed (DLBS) model was developed to improve nodule detection in regions where ribs and clavicles overlap without the need for special equipment or extra-radiation exposure [28]. AI also assisted less experienced individuals in detecting nodules that overlapped with anatomical structures, while readers with experience were able to detect these nodules with and without AI [41].

3.5. Factors Contributing to AI-Radiologist Discrepancies

Lung nodule detection presents significant challenges in both AI systems and radiologists due to nodule characteristics, anatomical structure, and technical reasons. AI systems exceed radiologists in the overall performance of detecting small nodules, but they tend to produce more false positives in their interpretations [32]. However, both AI and radiologists share common challenges. They equally struggle to identify ground-glass opacity nodules based on their subtlety and fail to examine anatomically difficult regions such as para-mediastinal, retro-cardiac, and retro-diaphragmatic areas [13,33]. Further complicating these challenges is the interpretation of chest radiographs with low contrast resolution and overlapping anatomical structures, obscuring subtle findings for both AI systems and human readers [31].

With the human factor in radiological interpretation, the performance is affected by multiple variables. The authors of [13] identified that environmental conditions such as reading time, fatigue levels, and years of experience impact radiologist performance. The impact of AI depends on both radiologist experience and case complexity [44]. Studies observe particularly high variability in performance across these experience levels and how AI assistance impacts them. For instance, AI can increase sensitivity in less experienced readers and specificity in more experienced radiologists [41].

Integration of AI into clinical practice is promising to reduce missed diagnoses but also has its challenges. A study reported that a radiologist’s accuracy can be reduced by up to 18%, and sensitivity can be reduced by 30% because of distracting findings, including COPD and small pleural effusions [49]. Different AI user interfaces (UIs) also had a major impact on how radiologists performed and interpreted AI outputs [43]. A study also described that occasional correct AI detections were rejected by readers, even where AI assistance improves outcomes [45].

The transition to practical AI in real-world clinical implementation reveals several practical limitations of current AI systems. The authors of [50] described the key challenges, including a lack of well-curated datasets, generalization, and lack of adequate publication standards for reproducibility. Another study demonstrates the lack of generalizability in training and test datasets for the AI, and the demographic differences may affect performance in real-world patient cohorts [48]. Hamanaka and Oda [18] noted the system’s main limitation, which is it cannot compare past radiographs with new ones, a key feature used in clinical practice. This research of [47] attributed the discrepancy between the results of AI and those of radiologists to the lack of clinical information and the difference between the imaging reading platform of AI and clinical practice.

3.6. Pattern of Missed Lung Nodule Findings: AI Versus Radiologist

Several studies have shown the ability of the designed AI algorithm to identify missed nodules. The authors of [30] confirmed the possibility of AI-improved detection of 15% of missed nodules in standalone radiologist sessions. Similarly, it was highlighted the fact that AI revealed 54% (69/131) of undiagnosed lung nodules that were missed in routine clinical practice [37]. Radiologist interpretation integrated with AI was most effective, where AI was able to identify eight out of 15 cases that all the radiologists missed. Their combination was found to have reduced the missed tumors by 60% to 65.4% [49]. Another study discovered that AI performed well in identifying right mid- and left-lower lung nodules, which are often missed by radiologists [44].

These findings were followed by other patterns in nodule detection by AI and radiologists. Comparatively, the authors of [36] showed different detection patterns. AI would have missed 68 nodules, which were detected by radiologists, while radiologists failed to detect 91 nodules detected by AI. The authors also highlighted that none of the AI or radiologists was able to identify nodules in 89 patients during early assessment [36]. The authors of [50] further described that while the adopted AI-CAD systems achieved detection of the lesions that the radiologists missed, the overall sensitivity was poorer than that of radiologists. Meanwhile, a study observed comparable disparities in obscured regions where AI and radiologists exhibited similar miss rates, with lung nodules missed by AI in 38.7% and by radiologists in 38% [39].

Nevertheless, specific challenges were reported in AI missed cases. Several cases of AI failures with GGO-predominant nodules were reported [33]. For instance, in the case of a 75-year-old man, AI failed to detect the tumors, as well as two radiologists. Further, AI occasionally missed subsolid nodules with spiculated edges in the left upper lobe [33]. The authors of [48] found that AI failed to detect findings in real-world patient cohorts more than radiologists for lung nodule cases. Lung cancer detection specifically showed varying miss rates. The AI missed 12/48 lung cancer cases, whereas radiologists failed to identify 7/48 cases, and four cases were missed by both AI and radiologists [15].

Another study stated that AI failed to identify all 18 cases of adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) and three additional cases because of the flat appearance of tumors in radiographic interpretation [18]. Concurrently, AI-reported missed findings in 21.1% (5289/25,104) of cases, of which 0.9% (47/5289) were clinically significant; among the missed findings were 71.4% (25/35) of lung nodules [46]. It was found that AI had a detection rate of around 1% for unexpected nodules in initial CXRs, 70% of which were true positive nodules, and 20.5% needed further action [26].

Table 4.

AI versus radiologist performance in lung nodule detection across study parameters and outcomes.

Table 4.

AI versus radiologist performance in lung nodule detection across study parameters and outcomes.

| Author and Year | Performance | Nodule Characteristics (Morphology Type, Size, and Location) | Discrepancies Factors Between AI and Radiologists in Lung Nodule Detection | The Pattern of Missed Lung Nodule Finding | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | Radiologist | Combined | AI | Radiologist | |||

| Nam et al., 2020 [13] |

Software: Lunit INSIGHT CXR version 1.0.1.1 (Lunit Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) |

| AI-aided radiologists improve AUROC to 0.685–0.724 |

|

|

Radiologist challenges:

| N/A |

| Sim et al., 2020 [30] | Sensitivity: 67.3% FPPI: 0.2 Software: Samsung Auto Lung Nodule Detection-ALND, version 1.00 (Suwon, Republic of Korea) | Sensitivity: 65.1% FPPI: 0.2 | Radiologists’ sensitivity with DCNN: 70.3% FPPI: 0.18 | N/A |

| The DCNN software improved the sensitivity of radiologists, irrespective of radiologist experience, nodule characteristics, or the vendor of the radiography acquisition system | AI helped find 15% of missed nodules from standalone sessions |

| Lee et al., 2020 [32] | Validation test performance:

Screening cohort performance:

Software: Lunit INSIGHT CXR version 4.7.2 (Lunit Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | AI performance improved with increased visibility of lung cancer in radiographs | N/A |

| Koo et al., 2020 [33] |

Software: Lunit INSIGHT CXR, version 1.00 (Lunit Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) |

|

| DCNN is better at the detection of nodules larger than 5 mm, solid, round-shaped, well-marginated, and laterally located nodules. DCNN struggles with masked nodules due to overlapping structure and GGO-dominant nodules | The radiologist missed a masked nodule due to overlapping with bony lesions and a GGO-dominant nodule in the upper left lobe | Radiologist interpretation errors due to:

DCNN limitations:

|

|

| Majkowska et al., 2020 [38] | Sensitivity

CNN architecture: Xception | Sensitivity

| N/A | N/A | N/A |

| N/A |

| Yoo et al., 2020 [15] | All radiograph

Digital radiograph

Malignant nodule detection:

Software: Lunit INSIGHT CXR, version not stated (Lunit Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) | All radiograph

Digital radiograph

Malignant nodule detection:

| N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Missed cases in nodule detection

Missed cases in cancer detection

Missed cases in malignant nodules

|

| Teng et al., 2021 [35] |

Software: QUIBIM Chest X-ray Classifier (Valencia, Spain) |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Yoo et al., 2021 [41] | N/A | Radiology residents

Radiologist

| Radiology residents with AI

Radiologist with AI

Software: Lunit INSIGHT CXR version 2.4.11.0 (Lunit Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) |

|

| AI benefits for different experience levels:

|

|

| Homayounieh et al., 2021 [44] | N/A |

|

Software: AI-Rad Companion Chest X-ray Algorithm (Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany) | AI improved detection across all difficulty nodule levels (easy, moderate, and challenging) | N/A |

|

|

| Tam et al., 2021 [49] |

Software: Red Dot (Behold.ai, London, UK) |

|

| Overall sensitivity increases with tumor size 1–2 cm | N/A |

|

|

| Peters et al., 2021 [50] |

Software: InferRead®DR (Infervision Technology Ltd., Beijing, China) |

| N/A |

|

|

| AI-CAD identified lesions missed by radiologists although had reduced overall sensitivity compared to radiologists |

| Nam et al., 2022 [25] |

Software: Lunit INSIGHT CXR version 2.0, Lunit Inc, Seoul, Republic of Korea |

|

| The median nodule detection size was 1.2 cm | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Bae et al., 2022 [31] | N/A |

Sensitivity use of CXR alone:

| Sensitivity withBSt-DE:

Sensitivity with BSp-DL:

| BSt-DE has good performance with small nodules, bone overlapping, and peripheral location | N/A |

| |

| Chiu et al., 2022 [36] |

Deep Learning architecture: You Only Look Once version 4 (YOLOv4) |

| N/A |

| N/A |

|

|

| Kaviani et al., 2022 [37] |

Software: qXR (Qure.Ai Technology, Mumbai, India) | N/A | N/A | AI has higher performance on detection of calcified nodules—calcified nodules (AUC 0.71) vs. non-calcified nodules (AUC 0.55) | N/A | Radiologist challenges:

AI challenges:

| AI detected 69/131 (53%) of missed lung nodules |

| Govindarajan et al., 2022 [14] | AI performance in categorizing normal and abnormal CXR (use radiologist as reference standard)

AI performance in categorizing CXR into sub abnormality (in this case lung nodule)

Software: qXR (Qure.Ai Technology, Mumbai, India) | N/A | Turnaround time of radiologists is reduced with AI assistance specifically:

| N/A | N/A |

| N/A |

| Ahn et al., 2022 [40] |

Software: Lunit INSIGHT CXR, version 3.1.2.0 (Lunit Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) |

| Reading time improved with AI assistance with an overall reduction was 3.9 s (p < 0.001) | N/A | N/A | Factors that influence reader performance with AI:

Impact of extensive AI output:

| N/A |

| Nam et al., 2023 [23] |

Software: Lunit INSIGHT CXR version 2.0.2.0 (Lunit Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) |

| AI-based CAD improved actionable lung nodule detection (odds ratio: 2.4) | AI improved the detection rate of

| N/A | N/A | N/A |

| You et al., 2023 [24] |

Software: Med-Chest X-ray System, version 1.0.1, (VUNO, Seoul, Republic of Korea) | N/A | Non-expert radiologists: improved DZ nodule detection with DLD | DLD has better performance for:

| N/A | Factors affecting DLD performance:

Data quantity vs. performance:

| N/A |

| Hwang et al., 2023 [26] |

Software: Lunit INSIGHT CXR version 3, Lunit Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) | N/A | N/A | False positive due to:

| N/A | Imaging challenges:

|

|

| Huh et al., 2023 [27] | N/A | Expert performance (seven experts)

|

Software: Lunit INSIGHT CXR version 4.7.2 (Lunit Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) | Limitations in the detection of those non-visible malignant nodules or obscured by anatomical structure (bone, heart, diaphragm, and mediastinum) | Limitations in the detection of those non-visible malignant nodules or obscured by anatomical structure (bone, heart, diaphragm, and mediastinum) |

| N/A |

| Kim et al., 2023 [28] |

| Radiologists’ mean sensitivity: 77.5% |

| DLBS model improved detection across nodule types by suppressing bone structures (rib, clavicle, and other anatomic structures) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kwak et al., 2023 [29] |

Software: Lunit INSIGHT CXR, version 2 and 3 (Lunit Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) | N/A | N/A | Nodule Characteristics detected by AI:

| N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Lee et al., 2023 [17] | High Diagnostic Accuracy (full dataset) AI Performance:

CNN architecture: ResNet34 |

| Readers with high diagnostic accuracy AI:

Readers with low diagnostic accuracy AI (no significant improvement):

| N/A | N/A |

| N/A |

| Ueno et al., 2023 [16] |

Software: EIRL Chest X-ray Lung Nodule (LPIXEL Inc., Tokyo, Japan) | N/A | N/A |

| N/A | Challenges for radiologists:

| N/A |

| Higuchi et al., 2023 [34] | Sensitivity

Specificity

AUC

CNN architecture: CheXNet model |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | A massive teaching dataset is needed to increase the accuracy of the AI | N/A |

| Farouk et al., 2023 [39] |

Software: Lunit INSIGHT CXR version 2.4.11.0 (Lunit Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) |

|

|

|

| AI and radiologists cannot detect nodules at blind or obscured areas on CXR |

|

| Tang et al., 2023 [43] | N/A | Sensitivity of radiologists without AI: 64% Specificity of radiologists without AI: 88% AUC of radiologist without AI: 0.82 | Sensitivity of radiologist with

Specificity of radiologist with

AUC of radiologist with

Software: Annalise Enterprise CXR (Annalise.ai, Sydney, Australia) | N/A | N/A |

| N/A |

| Bennani et al., 2023 [45] | N/A | Sensitivity without AI

Specificity without AI

| Sensitivity with AI

Specificity with AI

Software: ChestView version 1.2.0 (Gleamer, Paris, France) | AI increase detection of small nodules that are usually overlooked | N/A | Reader-AI interaction:

|

|

| Maiter et al., 2023 [48] | Compared with suspicious nodules:

Compared with cancer diagnosis:

Software: ALND version 1.0 (Samsung Electronics, Suwon, Republic of Korea) |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | AI challenges:

|

|

| Hamanaka et al., 2024 [18] | AI detection rate:

Software: EIRL X-ray Lung Nodule version 1.12 (LPIXEL Inc., Tokyo, Japan) | N/A | N/A |

| N/A |

|

|

| Kirshenboim et al., 2024 [42] |

Software: Lunit INSIGHT CXR version 2.0.2.0 (Lunit Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) | N/A |

| N/A | N/A | AI software limitations:

|

|

| Topff et al., 2024 [46] | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| N/A |

|

|

| van Leeuwen et al., 2024 [47] |

*** Software used |

| N/A |

| Decrease performance with lower nodule conspicuity | The difference in image reading platforms compare to clinical practice and absence of clinical information may contribute to discrepancies between AI and radiologists | N/A |

Notes: Abbreviation: N/A, Not available; AI, Artificial Intelligence; AUC, Area under the curve; AUROC, Area under the receiver operating characteristic; BSp-DL: Bone suppression deep learning, BSt-DE, Bone subtraction dual energy; CAD, Computer-assisted detection; CI, confidence interval; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CNN, Convolutional Neural Network; CT, Computed tomography; CXR, Chest X-ray; DCNN, Deep convolutional neural network; DLAD, Deep learning-based automatic detection; DLD, Deep learning detection; DZ, Danger zone; EMR, Electronic medical record; FPPI, False positive per image; FRCR, Fellow of Royal College of Radiologist; GGO, Ground-glass opacity; MDT, Multidisciplinary team; NDZ, Non-danger zone; NPV, Negative predictive value; NLST, National Lung Screening Trial; PACS, Picture archiving and communication system; PET-CT, Positron emission tomography-computed tomography; PPV, Positive predictive value; UI, User interface. *** Software used in this study are as follows: Annalise Enterprise CXR v3.1, Annalise.ai, Sydney, Australia; InferRead DR Chest v1.0.0.1, Infervision, Beijing, China; Lunit INSIGHT CXR v3.1.4.4, Lunit Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea; Milvue Suite-Smart Urgences v1.24, Milvue, Paris, France; ChestEye v2.6, Oxipit, Vilnius, Lithuania; AI-Rad Companion Chest X-ray v9, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany; Med-Chest X-ray v1.1.x, VUNO, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

4. Discussion

The integration of AI in chest radiographs for lung cancer screening plays an important role due to the high global burden of lung cancer and the disparities of traditional screening approaches using LDCT. The evidence presented shows that AI algorithms generally obtain higher sensitivity (ranging from 56.4% to 95.7%) than radiologists (ranging from 23.2% to 76%) while maintaining comparable specificity [13,23,25,26,29,36]. This performance characteristic is highly important in screening settings, where early detection is critical. However, the 44.1% to 95.7% variability in the sensitivity of the AI model [26] is concerning and asks pertinent questions about standardization and reliability. The amount of variability in the AI performance is strongly related to the specific model, implementation context, and characteristics of the data used for training. Therefore, this highlights the need for standardized protocols to assess the AI performance and training datasets that accurately reflect the population to be screened.

The differential performance of AI systems across nodule characteristics has big implications for screening programs. AI performs better than radiologists for larger nodules (i.e., >2 cm) and solid nodules [13,16,24,37] but has considerable variation in performance for different nodule morphology and location. Current AI implementations may miss subtle early-stage cancers that are critical targets in screening programs based on the lower detection rates for GGO nodules [16,33] and nodules in anatomically challenging locations (such as the “danger zone”) [24]. Since these subtle findings are mostly early-stage lung cancer with a better prognosis if diagnosed early, this limitation is particularly concerning. Future AI development should, therefore, address these performance gaps to maximize the efficacy of such screening programs in capturing the full range of actionable findings.

The screening context offers both opportunities and challenges in the complementary relationship of AI and radiologists. Using AI as a second reader increased sensitivity by 5.3% to 15% [25,28,33,44,49] and may benefit the screening programs, especially for less experienced readers. Yet, the variable performance across different clinical contexts [26] and levels of experience [13,41,44] implies that thoroughly evaluating the integration of AI into current screening workflows is necessary. While there is potential for AI to improve missed diagnoses, it must be balanced with a risk of over-investigation, particularly given the reported PPV of 5.1% [48]. Future research and policy efforts should seek to develop evidence-based guidelines for AI-assisted screening that are consistent across diverse practice settings.

Current AI systems exhibit technical and practical limitations that may limit screening implementation. The AI system is unable to compare with prior radiographs [18], which is one of the critical features of screening programs. It also draws attention to the poor generalizability of this model to other populations of patients and the effect of demographic variables on AI performance [48]. Our findings demonstrate that successful implementation will require an understanding of both technical and human factors, such as variability in the dependence of performance on the different AI user interfaces [43]. On the other hand, radiologists tend to reject the correct AI detections occasionally [45]. Thus, robust validation studies, user-centered design, and performance monitoring are needed to realize the full potential of AI in lung cancer screening.

The role in lung cancer screening programs looks promising concerning AI but with careful optimization. The high negative predictive value (98.9%) for normal vs abnormal chest radiography [14] may make this a useful triaging tool in high-volume screening settings. Despite this, it is clear that the risk of missed diagnosis, in particular for nodule types and locations [18,33], dictates that AI should supplement, but not replace, the role of the radiologist. Future development in this area should be targeted toward better detection of the subtle findings, better generalizability between populations, and seamless integration into clinical workflow while maintaining the balance between sensitivity and specificity, which is needed for a successful lung cancer screening program. The transformative potential of AI in the early detection and management of lung cancer will depend on ongoing research, multi-stakeholder collaboration, and evidence-based policy initiatives.

There are several key limitations to this systematic review. The included studies were predominantly retrospective cross-sectional and thus may introduce selection bias and do not include the impact of AI on real-time clinical decision-making. Longitudinal follow-up studies are missing to rate patient outcomes in early cancer detection and mortality reduction. Most of the previous studies adopt the binary classification approach (detection or non-detection) on clinical diagnosis, which may oversimplify this complexity. In addition, there are only limited studies on the effect of AI on radiologist training, a lack of standardized reporting on performance-influencing factors, and few studies on practical clinical implementation difficulties, all of which limit the generalizability and clinical translation of findings.

5. Conclusions

This review shows the great promise of AI algorithms to improve lung nodule detection on chest radiographs. AI systems have better sensitivity than radiologists, especially for smaller or subtle nodules, and can be an excellent instrument in lung cancer screening programs. The impact of how those tools can be deployed in parallel with radiologists and produce a combined effect is what makes AI for radiology important in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and efficiency. Despite this, many obstacles in AI implementation remain, including inconsistency in AI performance across studies and characteristics of nodules studied, variability in evaluation methods used, and a balance between high sensitivity and an acceptable false-positive rate.

More effort should be directed toward future studies constructing screening-oriented AI algorithms that yield more consistent and generalizable results. More long-term comparative investigations of the effectiveness of AI-assisted screening for the patients’ outcomes and cost-effectiveness analyses are needed. AI deployment in clinical settings must enhance the value that both human expertise and AI can bring to clinical practices as technology advances. Data privacy and algorithmic bias, among other ethical considerations, should also be effectively addressed. The proposed strategies aim to enhance early detection rates and patients’ well-being regarding lung cancer diagnosis by using AI appropriately in radiology practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.N.M.R. and A.N.A.; methodology, P.N.M.R., Z.A.H. and K.I.I.; validation, A.N.A., N.A. and Z.A.H.; formal analysis, P.N.M.R.; investigation, P.N.M.R.; resources, P.N.M.R.; data curation, P.N.M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, P.N.M.R.; writing—review, and editing, A.N.A., N.A., Z.A.H. and K.I.I.; visualization, P.N.M.R.; supervision, P.N.M.R., A.N.A. and N.A.; project administration, P.N.M.R. and A.N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this systematic review are primary data obtained from scholarly articles that are cited in this review paper and published within the studies. The extraction and analysis protocols are reported in detail in the Materials and Methods section of the study. Specific additional data or analysis protocols may be requested from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the Petal.ai tool was used to assist with initial data extraction, with all data points manually verified against original source articles by the authors. The authors also used Claude.AI as writing assistance to improve clarity and language presentation. After using this AI tool, authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AUROC | Area under the receiver operating characteristic |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CAD | Computer-aided detection |

| CXR | Chest X-ray |

| DLAD | Deep learning-based automatic detection |

| GGO | Ground-glass opacity |

| LDCT | Low-dose computed tomography |

| NPV | Negative predictive value |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

References

- Xia, C.; Dong, X.; Li, H.; Cao, M.; Sun, D.; He, S.; Yang, F.; Yan, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, N. Cancer statistics in China and United States, 2022: Profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin. Med. J. 2022, 135, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teh, H.; Woon, Y. Burden of cancers attributable to modifiable risk factors in Malaysia. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajadurai, P.; How, S.H.; Liam, C.K.; Sachithanandan, A.; Soon, S.Y.; Tho, L.M. Lung cancer in Malaysia. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.L.; Vadagam, P.; Vanderpoel, J.; Cohen, C.; Lewing, B.; Tkacz, J. Disparities in lung cancer: A targeted literature review examining lung cancer screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survival outcomes in the United States. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2024, 11, 1489–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thames, M.; Liu, J.; Colditz, G.; James, A. Urban–Rural Disparities in Access to Low-Dose Computed Tomography Lung Cancer Screening in Missouri and Illinois. PCD Staff 2020, 17, E140. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto, N.R.I.; Alberto, I.R.I.; Puyat, C.V.M.; Antonio, M.A.R.; Ho, F.D.V.; Dee, E.C.; Mahal, B.A.; Eala, M.A.B. Disparities in access to cancer diagnostics in ASEAN member countries. Lancet Reg. Health–West. Pac. 2023, 32, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahar, L.; Douangchai Wills, V.L.; Liu, K.K.; Fedewa, S.A.; Rosenthal, L.; Kazerooni, E.A.; Dyer, D.S.; Smith, R.A. Geographic access to lung cancer screening among eligible adults living in rural and urban environments in the United States. Cancer 2022, 128, 1584–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, D.; Yamamoto, A.; Shimazaki, A.; Walston, S.L.; Matsumoto, T.; Izumi, N.; Tsukioka, T.; Komatsu, H.; Inoue, H.; Kabata, D. Artificial intelligence-supported lung cancer detection by multi-institutional readers with multi-vendor chest radiographs: A retrospective clinical validation study. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, S.; Song, H.; Shin, Y.J.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, K.W.; Lee, S.S.; Lee, W.; Lee, S.; Lee, K.H. Deep learning–based automatic detection algorithm for reducing overlooked lung cancers on chest radiographs. Radiology 2020, 296, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassagnon, G.; Vakalopoulou, M.; Paragios, N.; Revel, M.-P. Artificial intelligence applications for thoracic imaging. Eur. J. Radiol. 2020, 123, 108774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, E.J.; Park, S.; Jin, K.-N.; Im Kim, J.; Choi, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Goo, J.M.; Aum, J.; Yim, J.-J.; Cohen, J.G. Development and validation of a deep learning–based automated detection algorithm for major thoracic diseases on chest radiographs. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e191095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.G.; Hwang, E.J.; Kim, D.S.; Yoo, S.-J.; Choi, H.; Goo, J.M.; Park, C.M. Undetected lung cancer at posteroanterior chest radiography: Potential role of a deep learning–based detection algorithm. Radiol. Cardiothorac. Imaging 2020, 2, e190222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, A.; Govindarajan, A.; Tanamala, S.; Chattoraj, S.; Reddy, B.; Agrawal, R.; Iyer, D.; Srivastava, A.; Kumar, P.; Putha, P. Role of an automated deep learning algorithm for reliable screening of abnormality in chest radiographs: A prospective multicenter quality improvement study. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, H.; Kim, K.H.; Singh, R.; Digumarthy, S.R.; Kalra, M.K. Validation of a deep learning algorithm for the detection of malignant pulmonary nodules in chest radiographs. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2017135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueno, M.; Yoshida, K.; Takamatsu, A.; Kobayashi, T.; Aoki, T.; Gabata, T. Deep learning-based automatic detection for pulmonary nodules on chest radiographs: The relationship with background lung condition, nodule characteristics, and location. Eur. J. Radiol. 2023, 166, 111002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Hong, H.; Nam, G.; Hwang, E.J.; Park, C.M. Effect of human-AI interaction on detection of malignant lung nodules on chest radiographs. Radiology 2023, 307, e222976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamanaka, R.; Oda, M. Can Artificial Intelligence Replace Humans for Detecting Lung Tumors on Radiographs? An Examination of Resected Malignant Lung Tumors. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, S.; Fong, P.-C.; Blokhina, M. Artificial intelligence for early diagnosis of lung cancer through incidental nodule detection in low-and middle-income countries-acceleration during the COVID-19 pandemic but here to stay. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, W.S.; Wilson, M.C.; Nishikawa, J.; Hayward, R.S. The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J. Club 1995, 123, A12–A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abouzahra, A.; Sabraoui, A.; Afdel, K. Model composition in Model Driven Engineering: A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2020, 125, 106316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.G.; Hwang, E.J.; Kim, J.; Park, N.; Lee, E.H.; Kim, H.J.; Nam, M.; Lee, J.H.; Park, C.M.; Goo, J.M. AI Improves Nodule Detection on Chest Radiographs in a Health Screening Population: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Radiology 2023, 307, e221894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Park, J.H.; Park, B.; Shin, H.-B.; Ha, T.; Yun, J.S.; Park, K.J.; Jung, Y.; Kim, Y.N.; Kim, M. The diagnostic performance and clinical value of deep learning-based nodule detection system concerning influence of location of pulmonary nodule. Insights Into Imaging 2023, 14, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, J.G.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, E.H.; Hong, W.; Park, J.; Hwang, E.J.; Park, C.M.; Goo, J.M. Value of a deep learning-based algorithm for detecting Lung-RADS category 4 nodules on chest radiographs in a health checkup population: Estimation of the sample size for a randomized controlled trial. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Shin, H.J.; Kim, E.-K.; Lee, E.H.; Lee, M. Clinical outcomes and actual consequence of lung nodules incidentally detected on chest radiographs by artificial intelligence. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, J.E.; Lee, J.H.; Hwang, E.J.; Park, C.M. Effects of expert-determined reference standards in evaluating the diagnostic performance of a deep learning model: A malignant lung nodule detection task on chest radiographs. Korean J. Radiol. 2023, 24, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, K.H.; Han, K.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Im, D.J.; Hong, Y.J.; Choi, B.W.; Hur, J. Development and validation of a deep learning–based synthetic bone-suppressed model for pulmonary nodule detection in chest radiographs. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2253820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, S.H.; Kim, E.K.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, E.H.; Shin, H.J. Incidentally found resectable lung cancer with the usage of artificial intelligence on chest radiographs. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, Y.; Chung, M.J.; Kotter, E.; Yune, S.; Kim, M.; Do, S.; Han, K.; Kim, H.; Yang, S.; Lee, D.-J. Deep convolutional neural network–based software improves radiologist detection of malignant lung nodules on chest radiographs. Radiology 2020, 294, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, K.; Oh, D.Y.; Yun, I.D.; Jeon, K.N. Bone suppression on chest radiographs for pulmonary nodule detection: Comparison between a generative adversarial network and dual-energy subtraction. Korean J. Radiol. 2022, 23, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Sun, H.Y.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Hwang, E.J.; Goo, J.M.; Park, C.M. Performance of a deep learning algorithm compared with radiologic interpretation for lung cancer detection on chest radiographs in a health screening population. Radiology 2020, 297, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, Y.H.; Shin, K.E.; Park, J.S.; Lee, J.W.; Byun, S.; Lee, H. Extravalidation and reproducibility results of a commercial deep learning-based automatic detection algorithm for pulmonary nodules on chest radiographs at tertiary hospital. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 65, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, M.; Nagata, T.; Iwabuchi, K.; Sano, A.; Maekawa, H.; Idaka, T.; Yamasaki, M.; Seko, C.; Sato, A.; Suzuki, J. Development of a novel artificial intelligence algorithm to detect pulmonary nodules on chest radiography. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 2023, 69, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, P.-H.; Liang, C.-H.; Lin, Y.; Alberich-Bayarri, A.; González, R.L.; Li, P.-W.; Weng, Y.-H.; Chen, Y.-T.; Lin, C.-H.; Chou, K.-J. Performance and educational training of radiographers in lung nodule or mass detection: Retrospective comparison with different deep learning algorithms. Medicine 2021, 100, e26270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.-Y.; Peng, R.H.-T.; Lin, Y.-C.; Wang, T.-W.; Yang, Y.-X.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Wu, M.-H.; Shiao, T.-H.; Chao, H.-S.; Chen, Y.-M. Artificial intelligence for early detection of chest nodules in X-ray images. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaviani, P.; Digumarthy, S.R.; Bizzo, B.C.; Reddy, B.; Tadepalli, M.; Putha, P.; Jagirdar, A.; Ebrahimian, S.; Kalra, M.K.; Dreyer, K.J. Performance of a Chest Radiography AI Algorithm for Detection of Missed or Mislabeled Findings: A Multicenter Study. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majkowska, A.; Mittal, S.; Steiner, D.F.; Reicher, J.J.; McKinney, S.M.; Duggan, G.E.; Eswaran, K.; Cameron Chen, P.-H.; Liu, Y.; Kalidindi, S.R. Chest radiograph interpretation with deep learning models: Assessment with radiologist-adjudicated reference standards and population-adjusted evaluation. Radiology 2020, 294, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farouk, S.; Osman, A.M.; Awadallah, S.M.; Abdelrahman, A.S. The added value of using artificial intelligence in adult chest X-rays for nodules and masses detection in daily radiology practice. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2023, 54, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.S.; Ebrahimian, S.; McDermott, S.; Lee, S.; Naccarato, L.; Di Capua, J.F.; Wu, M.Y.; Zhang, E.W.; Muse, V.; Miller, B. Association of artificial intelligence–aided chest radiograph interpretation with reader performance and efficiency. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2229289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Lee, S.H.; Arru, C.D.; Doda Khera, R.; Singh, R.; Siebert, S.; Kim, D.; Lee, Y.; Park, J.H.; Eom, H.J.; et al. AI-based improvement in lung cancer detection on chest radiographs: Results of a multi-reader study in NLST dataset. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 9664–9674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirshenboim, Z.; Gilat, E.K.; Carl, L.; Bekker, E.; Tau, N.; Klug, M.; Konen, E.; Marom, E.M. Retrospectively assessing evaluation and management of artificial-intelligence detected nodules on uninterpreted chest radiographs in the era of radiologists shortage. Eur. J. Radiol. 2024, 170, 111241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.S.; Lai, J.K.; Bui, J.; Wang, W.; Simkin, P.; Gai, D.; Chan, J.; Pascoe, D.M.; Heinze, S.B.; Gaillard, F. Impact of different artificial intelligence user interfaces on lung nodule and mass detection on chest radiographs. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, e220079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayounieh, F.; Digumarthy, S.; Ebrahimian, S.; Rueckel, J.; Hoppe, B.F.; Sabel, B.O.; Conjeti, S.; Ridder, K.; Sistermanns, M.; Wang, L. An artificial intelligence–based chest X-ray model on human nodule detection accuracy from a multicenter study. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2141096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennani, S.; Regnard, N.-E.; Ventre, J.; Lassalle, L.; Nguyen, T.; Ducarouge, A.; Dargent, L.; Guillo, E.; Gouhier, E.; Zaimi, S.-H. Using AI to improve Radiologist performance in detection of abnormalities on chest Radiographs. Radiology 2023, 309, e230860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topff, L.; Steltenpool, S.; Ranschaert, E.R.; Ramanauskas, N.; Menezes, R.; Visser, J.J.; Beets-Tan, R.G.; Hartkamp, N.S. Artificial intelligence-assisted double reading of chest radiographs to detect clinically relevant missed findings: A two-centre evaluation. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 5876–5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Leeuwen, K.G.; Schalekamp, S.; Rutten, M.J.; Huisman, M.; Schaefer-Prokop, C.M.; de Rooij, M.; van Ginneken, B.; Maresch, B.; Geurts, B.H.; van Dijke, C.F. Comparison of commercial AI software performance for radiograph lung nodule detection and bone age prediction. Radiology 2024, 310, e230981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiter, A.; Hocking, K.; Matthews, S.; Taylor, J.; Sharkey, M.; Metherall, P.; Alabed, S.; Dwivedi, K.; Shahin, Y.; Anderson, E. Evaluating the performance of artificial intelligence software for lung nodule detection on chest radiographs in a retrospective real-world UK population. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e077348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, M.; Dyer, T.; Dissez, G.; Morgan, T.N.; Hughes, M.; Illes, J.; Rasalingham, R.; Rasalingham, S. Augmenting lung cancer diagnosis on chest radiographs: Positioning artificial intelligence to improve radiologist performance. Clin. Radiol. 2021, 76, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.A.; Decasper, A.; Munz, J.; Klaus, J.; Loebelenz, L.I.; Hoffner, M.K.M.; Hourscht, C.; Heverhagen, J.T.; Christe, A.; Ebner, L. Performance of an AI based CAD system in solid lung nodule detection on chest phantom radiographs compared to radiology residents and fellow radiologists. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).