Abstract

Background: Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) continues to be underrecognized and inadequately treated. We aimed to investigate the current status of FH diagnosis and treatment in South Korea. Methods: Patients from two tertiary hospitals in South Korea between 2010 and 2023 with either a diagnosis of FH (ICD-10 code: E7800), had LDLR, APOB, or PCSK9 mutations, or had low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels exceeding 325 mg/dL were considered for inclusion. Demographic and laboratory characteristics as well as pharmacologic treatment patterns were assessed. Results: A total of 148 patients were retrospectively identified. The mean age at diagnosis was 49.3 years, and 33 (22.3%) had a history of established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). The majority of patients were diagnosed in the cardiology or endocrinology departments. The LDL-C level at enrollment was 247 ± 98 mg/dL (conversion to treatment-naïve LDL-C: 343 ± 141 mg/dL), which decreased to 122 ± 60 mg/dL after one year, achieving guideline-recommended target levels in 11.5%. A high proportion of patients were treated with statins (80.2%) and ezetimibe (64.9%), but the use of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors was low (11.7%). Patients diagnosed after 2020 achieved significantly lower LDL-C levels at one year compared to those diagnosed between 2020 and 2019 (107 ± 50 vs. 152 ± 68 mg/dL, p = 0.003). Two ischemic strokes and two myocardial infarctions occurred during a median follow-up of 25.3 months. Conclusions: FH is frequently diagnosed late after the onset of clinical ASCVD and is undertreated, although recent trends show improvement. Our results again underline the need for proper screening and identification of patients with FH.

1. Introduction

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is an autosomal dominant disorder affecting low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) metabolism, primarily caused by mutations in the LDLR, APOB, and PCSK9 genes [,]. These genetic alterations result in significantly elevated LDL-C levels, substantially increasing the risk of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) from childhood []. Recent global prevalence estimates for FH range from 1:200 to 1:250, with variations across populations [,,]. A meta-analysis conducted in 2020 estimated the prevalence of FH in Asia at 0.19% compared to 0.32% in Europe and North America []. The exact prevalence of FH in Korea is yet to be reported, although it is estimated to be largely similar to other countries [,]. However, the prevalence in any given population depends on factors such as the diagnostic criteria used, ethnicity, and the age distribution of the population [].

Diagnosis of FH is typically based on clinical presentation and is often made through the identification of a positive family history of premature ischemic heart disease and personal hypercholesterolemia []. The most widely used diagnostic criteria include the Dutch Lipid Clinic Network (DLCN) and Simon Broome criteria [,]. The detection rate for pathologic variants (PVs) in patients diagnosed with FH is 40–80% [,,,], and the presence of PVs has been shown to correlate with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and poorer response to lipid-lowering therapy [,,]. Despite advancements in FH treatment, a significant proportion of affected individuals remain undiagnosed or inadequately treated [,,]. In Korea, the General Health Screening Program mandates LDL-C testing every 4 years for individuals aged 20 and older, providing a potential platform for identifying high-risk individuals []. However, challenges persist in FH detection and management due to factors such as insufficient awareness among healthcare providers and the general population []. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the current status of FH diagnosis and treatment in two large tertiary hospitals in South Korea.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Participants

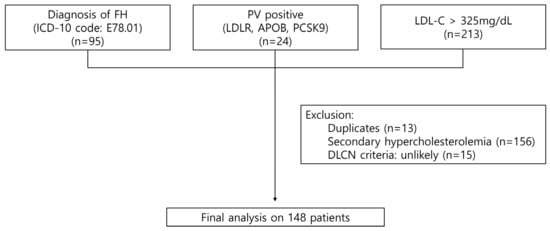

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients from two major tertiary hospitals in Korea between 2010 and 2023. The study included three groups: (1) individuals with a diagnosis of FH based on the ICD-10 code E78.01 (n = 95); (2) patients with PVs in the LDLR, APOB, or PCSK9 genes (n = 24); and (3) individuals with LDL-C levels > 325 mg/dL, corresponding to 8 points on the DLCN criteria and meeting the definition of probable FH based LDL-C levels alone (n = 213). After excluding overlapping cases (n = 13), patients with secondary hypercholesterolemia (n = 156), and those classified as “unlikely” based on the DLCN criteria (n = 15), a total of 148 patients were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). The Institutional Review Board of each participating institution including Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital approved this study (KC24RISI0109), and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to its retrospective nature. This study is in accord with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1.

Selection process of the study population. FH, familial hypercholesterolemia; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; DLCN, Dutch Lipid Clinic Network.

2.2. Definitions

To assess the baseline LDL-C levels of patients who were already on lipid-lowering therapy at the time of diagnosis, we adjusted LDL-C levels to pretreatment levels using the following formula: Treatment-naïve LDL-C = Current LDL-C/(1 − LDL-C reduction percentage), which has been reported to correlate with pretreatment LDL-C levels in FH patients with good accuracy []. The LDL-C reduction percentage was based on the known efficacy of the specific lipid-lowering therapy the patient was receiving at the time of measurement, where the reduction percentages for each lipid-lowering medication are listed in Supplementary Table S1 [,,]. Target LDL-C levels were defined as <55 mg/dL in patients with established ASCVD or another major risk factor, and <70 mg/dL in those without these conditions [].

A patient was considered to have been diagnosed with FH at the time (1) the ICD code E78.01 was assigned, or (2) results for LDLR, APOB, or PCSK9 mutations were confirmed. Baseline data including demographics, medical history, and laboratory data were recorded at this time point. For the patients with LDL-C levels > 325 mg/dL, but who had not received an ICD-10 diagnosis of FH or did not have LDLR, APOB, or PCSK9 mutations, baseline data were defined as those obtained at the time of the laboratory test that first recorded an LDL-C value > 325 mg/dL. The “diagnosis” was defined as having been made in the department where lipid-lowering therapy was first initiated. Lipid profiles and medical treatment data at one year were obtained from the visit closest to one year after the initial diagnosis. Clinical outcomes, including new myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, and ischemic stroke, were identified through a review of medical records and followed-up for the maximum available duration. Mortality status was verified based on records of disqualification from the National Health Insurance Service.

2.3. Genetic Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples. The LDLR gene was analyzed by direct sequencing, covering all exons and exon–intron boundaries; this testing has been available at our institution since 2019. In addition, we reviewed the records of patients who underwent next-generation sequencing (NGS) between 2019 and 2023 to identify PVs in FH-related genes (LDLR, APOB, or PCSK9), detected either as primary findings or secondary findings from broader testing. NGS was performed using the TruSight One Expanded Sequencing Panel (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), which targets approximately 6700 genes associated with Mendelian disorders. Library preparation followed Illumina’s on-bead tagmentation and hybrid-capture enrichment workflow with 50–100 ng of input genomic DNA. Sequencing used 2 × 150 bp paired-end reads on an Illumina NextSeq platform, and data were processed using standard enrichment-based pipelines, including alignment to the GRCh37/hg19 reference genome and variant calling with Illumina’s recommended analysis suite. Variants were subsequently annotated and reviewed using VariantStudio (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The pathogenicity of all identified variants was determined according to the 2015 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology guidelines []. All PVs are reported using standard Human Genome Variation Society nomenclature. In the primary analysis, only patients with a positive PV result were included. However, baseline characteristics were also compared between PV-positive and PV-negative patients among all individuals who underwent PV testing.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Categorical data are presented as numbers and frequencies and compared using the χ2 test, or Fisher’s exact test when more than 20% of cells had an expected count of less than 5 in a 2 × 2 table. Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range], depending on variable distribution, and compared using the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test as appropriate. Data on family history were not systematically recorded and contained a high proportion of missing values; for statistical analysis, these missing entries were considered as negative findings. Use of lipid-lowering medications and corresponding changes in lipid profiles were analyzed among patients with available one-year follow-up data. To analyze temporal trends in FH treatment, patients were stratified according to the year of diagnosis: 2010–2019 and 2020–2023, to reflect changes in lipid-lowering management following the introduction of lower LDL-C targets in the 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines and the initiation of national insurance coverage for Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors in 2020. Changes in LDL-C over time were analyzed using a repeated-measures linear mixed-effects model including time (baseline and 1-year), diagnosis period (2010–2019 vs. 2020–2023), and their interaction as fixed effects, with a random intercept for each participant. The model was adjusted for age, sex, and ASCVD history to assess whether LDL-cholesterol reduction differed between diagnosis periods after accounting for covariates. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software version 4.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

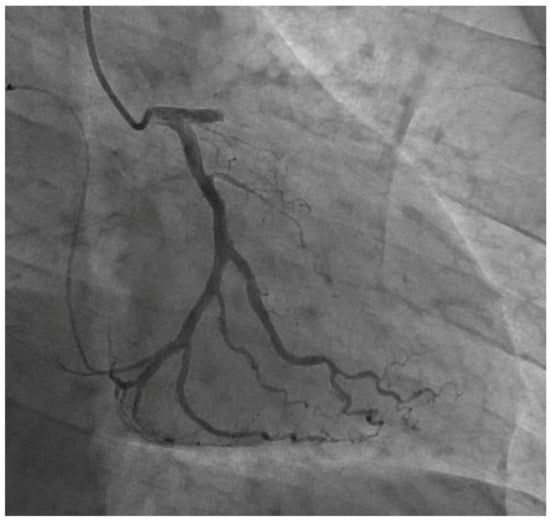

The baseline characteristics of our study subjects are presented in Table 1. The mean age at diagnosis was 49.3 years, and 60.8% were female. There were 9 (6.1%) patients with a history of previous myocardial infarction, 16 (10.8%) patients with a history of percutaneous coronary intervention, and 5 (3.4%) patients with a history of stroke. The initial LDL-C levels averaged 242.0 ± 97.9 mg/dL, which, when converted to treatment-naïve LDL-C levels, corresponded to 343.3 ± 140.9 mg/dL. When we categorized our study subjects according to the DLCN criteria, possible FH (score 3–5), probable FH (score 6–8), and definite FH (score > 8) were found in 27 (18.2%), 57 (38.5%), and 64 (43.2%), respectively. A representative coronary angiogram of a 42-year-old male with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction is shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

Figure 2.

Representative coronary angiogram of a 42-year-old male with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

3.2. Clinical Presentation and Reasons for Referral

We investigated the pathways leading to the diagnosis of FH. The most common referral reason was marked dyslipidemia, observed in 55 (37.2%) patients, of whom 30 (20.3%) were referred without prior lipid-lowering therapy and 25 (16.9%) after persistently elevated LDL-C levels despite treatment. Coronary artery disease (CAD) accounted for 26 (17.6%) cases—5 (3.4%) with asymptomatic CAD, 17 (11.5%) with angina, and 4 (2.7%) with myocardial infarction—in which persistently high LDL-C levels despite lipid-lowering therapy prompted further evaluation for FH. Seven (4.7%) patients were diagnosed after embolic events, such as stroke or retinal artery occlusion. Referrals based on xanthomas and family history were less common, with 2 (1.1%) patients and 3 (2.0%) patients, respectively. Additionally, 48 (32.4%) patients were referred after elevated LDL-C levels were incidentally detected during evaluations for other conditions, such as arrhythmias, diabetes, hypertension, or pre-operative assessments. Of note, 7 (4.7%) patients with elevated LDL-C levels > 325 mg/dL did not receive lipid-lowering treatment and were presumably undiagnosed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical presentation leading to evaluation and diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia.

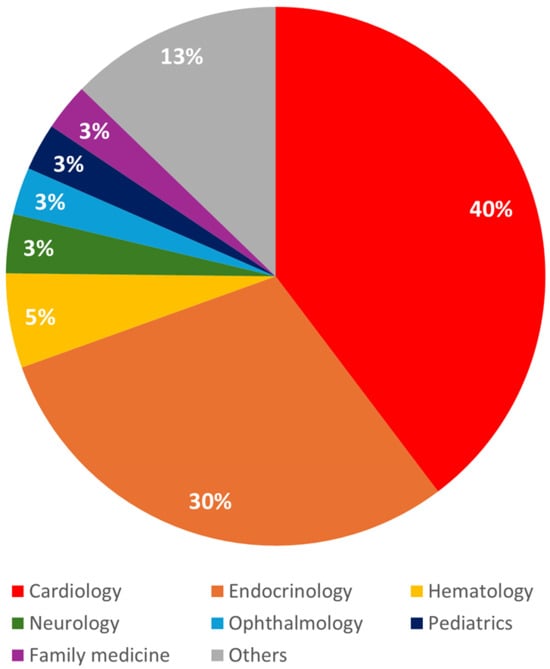

Among the medical specialties involved in the diagnosis and treatment of FH, cardiology accounted for the largest proportion at 40%, followed by endocrinology at 30% (Figure 3). Neurology accounted for a relatively smaller proportion at 3%. FH was also diagnosed in various specialties including hematology and ophthalmology when elevated LDL-C levels were identified as an incidental finding during evaluations for other medical conditions.

Figure 3.

Distribution of familial hypercholesterolemia diagnoses by clinical department.

3.3. Pathologic Variant Testing

Out of 148 participants, 47 underwent genetic testing. Among them, 45 individuals from the cardiology and endocrinology departments underwent LDLR gene testing due to elevated LDL-C levels, with 22 identified as PV-positive. The list of PVs are shown in Table 3. A broad spectrum of pathogenic or likely pathogenic LDLR variants was identified, encompassing missense, nonsense, frameshift, splice-site, and indel mutations. Among these, three recurrent variants were observed: c.361T>G [p.Cys121Gly] in five patients, c.2054C>T [p.Pro685Leu] in two patients, and c.682G>T [p.Glu228]* in two patients. In addition, NGS identified PVs in the LDLR gene in two pediatric patients who underwent testing for retinal disorders, where these findings were incidental and unrelated to the primary clinical indication. One of these patients also carried a PV in APOB, and no PVs were detected in PCSK9.

Table 3.

Pathologic variant list.

In a supplementary analysis of all patients who underwent LDLR gene testing, out of a total of 73 individuals who were tested, 24 (33.9%) were positive, and 49 (67.1%) were negative (Supplementary Table S2). The PV-positive patients were slightly younger (mean age 55.2 vs. 47.5 years) and had slightly higher LDL-C levels, although this did not reach statistical significance. PV-positive patients also had lower blood pressures, lower triglycerides, and lower platelet count, and were more likely to be prescribed PCSK9 inhibitors.

3.4. Lipid Profiles and Lipid Lowering Treatments

Follow-up data on lipid profiles and lipid-lowering treatments up to one year were available for 96 patients (Table 4). After one year of treatment, the mean LDL-C decreased to 121.6.1 ± 60.0 mg/dL, achieving target levels in 11 (11.5%) patients. Lipid-lowering therapies at the one-year point included statin therapy for 77 (80.2%) patients, ezetimibe for 61 (64.9%) patients, fibrates for 7 (7.4%) patients, and Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors for 11 (11.7%) patients.

Table 4.

Lipid-lowering treatments and lipid profiles in patients with follow-up data.

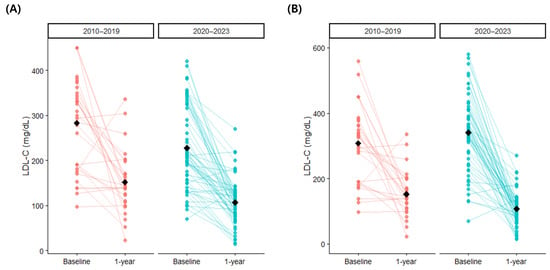

When the patients were stratified according to the year of diagnosis, 33 (34.4%) were diagnosed between 2010 and 2019, and 63 (65.6%) were diagnosed in 2020 or later. Those diagnosed from 2020 onwards had lower baseline LDL-C levels, but there was no significant difference after conversion to treatment-naïve LDL-C levels (Figure 4, Table 4). Patients diagnosed from 2020 onwards were more likely to be receiving statins, higher statin doses, and ezetimibe. At one year after follow-up, the patients diagnosed from 2020 onwards had significantly lower LDL-C (2010–2019: 152.1 ± 68.3 mg/dL vs. 2020–2023: 106.8 ± 49.8 mg/dL, p = 0.003), total cholesterol (p < 0.001), and triglycerides (p = 0.021) compared to those diagnosed between 2010 and 2019. Achievement of guideline-recommended target LDL-C levels were low in both groups. The proportion of patients on statins and statin doses were similar between the two groups, but those diagnosed from 2020 onwards were more likely to receive ezetimibe (2010–2019: 43.8% vs. 2020–2023: 75.8%, p = 0.004) and PCSK inhibitors (2010–2019: 0.0% vs. 2020–2023: 17.7%, p = 0.028), and less likely to receive fibrates (p = 0.010).

Figure 4.

One-year changes in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol according to diagnosis period: (A) uncorrected values and (B) converted treatment-naïve baseline values. LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Analysis on LDL-C levels across the period of diagnosis using linear mixed-effects models showed that there was a significant interaction between the degree of LDL-C reduction and the period of diagnosis when the baseline LDL-C was estimated using conversion to treatment-naïve levels (Table 5). The magnitude of LDL-C reduction from treatment-naïve baseline levels for patients diagnosed in 2020 or later was 73.2 mg/dL (95% confidence interval, 12.2–134.8 mg/dL; p = 0.026) greater than those diagnosed between 2010 and 2019, even after adjustment for overall LDL-C levels, age, sex, and prior ASCVD. When unadjusted LDL-C levels were used for baseline values, no difference in 1-year LDL-C reduction was noted across diagnosis periods, but overall LDL-C levels were significantly lower in the patients diagnosed in 2020 or later (p = 0.002).

Table 5.

Changes in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol between baseline and at one year analyzed using linear mixed-effects models.

3.5. Clinical Outcomes

During a median follow-up period of 25.3 months, the clinical outcomes included two cases of ischemic stroke and two cases of myocardial infarction. No mortality was reported.

4. Discussion

This study retrospectively identified patients with FH through ICD-10 code diagnosis, genetic testing, and elevated LDL-C levels. The main findings are as follows: (1) a substantial proportion of patients with suspected FH are diagnosed later in life, often after the cumulative effects of prolonged LDL-C elevation have manifested; (2) many patients are incidentally diagnosed during evaluation for unrelated medical conditions; and (3) despite lipid-lowering therapy, attainment of guideline-recommended LDL-C targets remains suboptimal. Our study, in line with previous research, provides evidence of the persistent insufficient awareness of FH, resulting in significant underdiagnosis and undertreatment [,,].

There is no universally accepted diagnostic standard for FH, and different clinical criteria are applied across countries []. The most commonly used diagnostic criteria worldwide are the DLCN and the Simon Broome criteria [,]. Both incorporate LDL-C levels as a key component of the diagnostic algorithm, as well as physical examination findings, patient and family history, and the presence of PVs. Of note, these criteria were largely derived and validated in Western populations. In an analysis of the LDL-C distribution of FH patients from the 2020 Korean Familial Hypercholesterolemia (KFH) Registry, an LDL-C level of 177 mg/dL was suggested as a threshold for suspecting FH, while the median LDL-C level was 221 mg/dL []. The LDL-C levels in the present study were somewhat higher, with a mean of 242 mg/dL and an estimated treatment-naïve level of 327 mg/dL. This may have been in part due to the selection criteria of LDL-C > 325 mg/dL, corresponding to a diagnosis of probable FH on LDL-C levels alone. Consistent with this, our cohort included a higher proportion of patients with definite or probable FH compared with the 2020 KFH registry, suggesting that our study population may represent a cohort with greater phenotypic specificity for FH.

The most common reason for referral was dyslipidemia, followed by manifestations of ASCVD such as CAD, stroke, and retinal artery occlusion. Nearly half of the cases were identified in cardiology, often after initiation of lipid-lowering therapy for established CAD. Early screening beginning in childhood, combined with cascade testing, has been implemented in several European countries to facilitate timely identification and treatment of FH []. In Korea, integration of a targeted screening approach of those with high LDL-C levels through the General Health Screening Program has shown efficacy for the detection of FH in the general population []. In our study, the high proportion of FH diagnoses made only after the onset of clinical ASCVD indicates delayed detection, further supporting the need for earlier diagnosis such as through national screening initiatives. In addition, a substantial proportion of FH diagnoses occurred incidentally when elevated LDL-C levels were detected during evaluations for unrelated conditions—including arrhythmias, diabetes, hypertension, malignancy work-ups, routine health examinations, and pre-operative assessments. These incidental cases often had LDL-C levels far exceeding guideline thresholds and frequently met the DLCN criteria once evaluated, suggesting delayed recognition rather than milder phenotypes. These findings highlight gaps in Korea’s FH screening infrastructure and underscore the need for more proactive detection strategies to enable earlier intervention.

Accurate identification of PVs and their clinical interpretation is important in FH management, especially as those with PVs have markedly higher cardiovascular risk even after accounting for LDL-C levels [,]. However, there is no official national guideline for genetic testing in FH screening, and insurance coverage criteria for genetic testing are limited in Korea. Currently, it is performed in cases where FH is strongly suspected clinically, in individuals with a family history of early onset CVD, in first-degree relatives of diagnosed FH patients, and in patients with severe high LDL-C who show an insufficient response to lipid-lowering therapy [,]. In our study, only 31.8% underwent PV testing, which is likely due to barriers such as cost and insufficient awareness, and reflects the current challenges of FH treatment in Korea. In our study, positive findings were found in 34% of the patients tested for PVs, similar to the 35% found in the 2020 Korean Registry Project [], but further large-scale studies will be needed to accurately estimate the prevalence of PVs in Korea, which is known to vary significantly across ethnicities [,,]. Several of the recurrent variants in our cohort have been reported as pathogenic in multiple FH families and are listed among recurrent LDLR mutations in East Asian and global FH variant compilations []. However, most of the remaining variants in our series were observed only once or twice and were not among the pan-Asian founder mutations, consistent with the extensive allelic heterogeneity described in FH [].

In addition, two pediatric patients were incidentally found to harbor PVs in the LDLR and/or APOB genes through clinical exome sequencing initially performed for retinal disorders. Such findings illustrate that when genetic testing involves broad sequencing approaches, such as whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing, clinically relevant variants unrelated to the primary indication may be detected. However, the practice of using wide genomic coverage for the purpose of identifying incidental findings remains controversial in clinical genetics, given the potential for numerous secondary findings and the complexities they raise for patient counseling and management [].

Treatment for FH typically follows a stepwise approach, starting with high-intensity statins at maximum tolerated doses, followed by the addition of ezetimibe [,]. If this fails to achieve target LDL-C levels, PCSK9 inhibitors should be considered [,]. As patients with FH have increased ASCVD risk beyond LDL-C levels, stringent lipid level control is key to preventing ASCVD []. The optimal treatment targets for FH patients are a 50% reduction in LDL-C and levels < 70 mg/dL, or <55 mg/dL in the presence of ASCVD [,], but achievement of these targets is difficult in the majority of patients []. LDL-C < 70 mg/dL in patients with established ASCVD or major risk factors and <100 mg/dL in those without these conditions are recommended as more realistic targets in many guidelines [,]. Our findings support the efficacy of contemporary lipid-lowering therapy, demonstrating a reduction in mean LDL-C levels from 247 mg/dL to 122 mg/dL after one year of treatment. However, achievement of target LDL-C levels was limited to only 11.5% of the population. Although this is comparable to global data showing that only 2.8% and 13.6% of FH patients achieve an LDL-C level of <70 mg/dL and <100 mg/dL, respectively, substantial room for improvement remains []. Previous studies have shown limited probability of achieving targets even with maximal statin-based lipid-lowering therapies [,,]. Recent advances in lipid-lowering therapy, including PCSK9 inhibitors and bempedoic acid, have demonstrated efficacy in patients who fail to achieve target LDL-C levels or are intolerant to statin-based regimens, and may offer additional therapeutic options for those with FH [,]. The low proportion of patients receiving PCSK9 inhibitors (11.7%) at one year despite limited LDL-C target attainment reflects persistent barriers at both the system and clinician levels. Early in the study period, PCSK9 inhibitors were not widely accessible, and national insurance reimbursement for FH and very high-risk ASCVD patients only began in 2020, markedly limiting uptake among those diagnosed earlier. Even after reimbursement, out-of-pocket costs likely remained a deterrent. Institutional prescribing patterns, availability constraints, and clinical inertia may also have contributed, particularly when existing therapy was perceived as sufficient despite suboptimal control. Because PCSK9 inhibitors provide substantial additional LDL-C lowering in patients with suboptimal response to statin-based regimens [,], reducing financial and administrative obstacles will be important to improve long-term lipid management and cardiovascular outcomes in this population.

In our study, patients diagnosed from 2020 onward had significantly lower LDL-C levels at baseline and at one year. The absolute magnitude of LDL-C reduction from baseline to one year was similar between diagnosis periods; however, when baseline LDL-C was estimated using conversion to treatment-naïve levels, patients diagnosed from 2020 onward showed significantly greater LDL-C reduction. This enhanced response likely reflects a broader use of ezetimibe and the increased availability and reimbursement of PCSK9 inhibitors beginning in 2020, consistent with the significantly higher use of these therapies in patients diagnosed during this later period. In addition, evolving clinical practice influenced by the publication of guidelines recommending lower LDL-C targets, the introduction of PV testing for more definite FH diagnoses (which was available in our institutions from 2019), and heightened clinician awareness may have contributed to earlier recognition and more intensive therapy. As seen by the higher use of PCSK9 in PV positive patients, limited genotyping may obscure true genotype–phenotype relationships and hinder optimal risk stratification and treatment planning, highlighting the need for systematic PV testing. Early and intensive lipid-lowering is known to reduce cardiovascular risk in FH, consistent with the low number of cardiovascular events observed during follow-up in our cohort. Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of active screening for early FH diagnosis and aggressive lipid-lowering treatment to improve long-term cardiovascular outcomes.

5. Limitations

Our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, this study was conducted at two tertiary hospitals with a relatively small cohort size. As such hospitals often manage more severe or well-resourced patients, the cohort may not fully reflect the general FH population, particularly given that diagnoses were made in the cardiology department after clinical ASCVD. Second, some patients with an ICD-10 code diagnosis of FH may have been misdiagnosed. In addition, the different methods used to identify patients with FH may have resulted in heterogeneity of the study cohort. However, we applied the DLCN criteria and excluded those who did not meet diagnostic criteria. Third, due to the retrospective nature of the study, we were unable to comprehensively assess important patient characteristics, including xanthomas, medical and family histories, and laboratory data such as lipoprotein(a). Finally, the rate of adverse events in the study population was low, limiting the ability to analyze outcome data.

6. Conclusions

In this real-world analysis of patients with FH, many were diagnosed later in life and initiated treatment only after the onset of clinical ASCVD. Although LDL-C levels decreased substantially and cardiovascular events were infrequent during lipid-lowering therapy, attainment of target LDL-C levels was low. Our study underscores the persistent challenges in the diagnosis and management of FH, highlighting its underdiagnosis and undertreatment. However, comparison across diagnosis periods suggests improvement in the treatment of FH, as evidenced by lower LDL-C levels in recent years. Active screening for early diagnosis of FH and intensive lipid-lowering treatment will be crucial in addressing the cardiovascular burden associated with FH and enhancing long-term outcomes for affected individuals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diagnostics15233062/s1, Table S1: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reduction percentages for each lipid-lowering medication for use in conversion to treatment-naïve low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels; Table S2: Baseline characteristics of the patients who underwent testing for pathologic variants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-C.Y.; Data curation, D.K. and J.K.; Formal analysis, K.A.K.; Funding acquisition, J.-C.Y.; Investigation, K.A.K.; Methodology, K.A.K.; Project administration, J.-C.Y.; Resources, K.A.K. and H.S.K.; Supervision, J.-C.Y.; Validation, E.-S.K.; Visualization, K.A.K. and M.-k.J.; Writing—original draft, K.A.K. and M.-k.J.; Writing—review and editing, K.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00455661, No. RS-2024-00440824: Bio & Medical Technology Development Program) and by the Korean National Institute of Health (NIH) research project (2025-ER0904-00). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board of each participating institution including Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital approved this study (KC24RISI0109, 15 January 2024), and this study is in accord with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Requirement for informed consent was waived due to its retrospective nature by the Institutional Review Board of each institution.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Access will be provided in minimally anonymized form as required by IRB regulations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Defesche, J.C.; Gidding, S.S.; Harada-Shiba, M.; Hegele, R.A.; Santos, R.D.; Wierzbicki, A.S. Familial hypercholesterolaemia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.J.; Yoon, M.; Kang, H.J.; Kim, B.J.; Choi, S.H.; Jeong, I.K.; Lee, S.H.; Task Force Team for Familial Hypercholesterolemia; Korean Society of Lipid and Atherosclerosis. 2022 Consensus Statement on the Management of Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Korea. J. Lipid Atheroscler. 2022, 11, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Task Force Members; ESC Comm Practice Guidelines CPG; ESC Natl Cardiac Societies; Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Taskinen, M.-R. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis 2019, 290, 140–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, M.; Watts, G.F.; Tybjaerg-Hansen, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Mutations causative of familial hypercholesterolaemia: Screening of 98 098 individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study estimated a prevalence of 1 in 217. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 1384–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, D.S.; Bestwick, J.P.; Morris, J.K.; Whyte, K.; Jenkins, L.; Wald, N.J. Child-Parent Familial Hypercholesterolemia Screening in Primary Care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1628–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S.; Chen, Z.; Deerochanawong, C.; Shyu, K.G.; Tan, R.S.; Tomlinson, B.; Yeh, H.I. Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Asia Pacific: A Review of Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management in the Region. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2021, 28, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beheshti, S.O.; Madsen, C.M.; Varbo, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Worldwide Prevalence of Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Meta-Analyses of 11 Million Subjects. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2553–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, M.A.; Hutter, C.M.; Zimmern, R.L.; Humphries, S.E. Genetic causes of monogenic heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: A HuGE prevalence review. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 160, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon Broome Register Group. Risk of fatal coronary heart disease in familial hypercholesterolaemia. Scientific Steering Committee on behalf of the Simon Broome Register Group. BMJ 1991, 303, 893–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Lee, C.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Kang, H.J.; Park, K.S.; Cho, B.R.; Kim, B.J.; Sung, K.C.; et al. Phenotypic and Genetic Analyses of Korean Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Results from the KFH Registry 2020. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2022, 29, 1176–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, H.; Liu, Z.; Cui, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Yin, K.; Li, W.; Zhou, Z. Targeted Genetic Analysis in a Chinese Cohort of 208 Patients Related to Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2020, 27, 1288–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futema, M.; Whittall, R.A.; Kiley, A.; Steel, L.K.; Cooper, J.A.; Badmus, E.; Leigh, S.E.; Karpe, F.; Neil, H.A.; Simon Broome Register, G.; et al. Analysis of the frequency and spectrum of mutations recognised to cause familial hypercholesterolaemia in routine clinical practice in a UK specialist hospital lipid clinic. Atherosclerosis 2013, 229, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, K.; Mizobuchi, A.; Ying Fu, H.; Ishikawa, S.; Tada, H.; Kawashiri, M.A.; Yokota, I.; Sasaki, T.; Ito, S.; Kunikata, J.; et al. Universal Screening for Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Children in Kagawa, Japan. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2022, 29, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, H.; Kawashiri, M.A.; Nohara, A.; Inazu, A.; Mabuchi, H.; Yamagishi, M. Impact of clinical signs and genetic diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia on the prevalence of coronary artery disease in patients with severe hypercholesterolaemia. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 1573–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Lee, C.J.; Pak, H.; Kim, D.I.; Rhee, M.Y.; Lee, B.K.; Ahn, Y.; Cho, B.R.; Woo, J.T.; Hur, S.H.; et al. GENetic characteristics and REsponse to lipid-lowering therapy in familial hypercholesterolemia: GENRE-FH study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.V.; Laurie, A.D.; Reid, N.J.; Leath, M.A.; King, R.I.; Chan, H.K.; Florkowski, C.M. Association of Clinical Characteristics With Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Variants in a Lipid Clinic Setting: A Case-Control Study. J. Lipid Atheroscler. 2024, 13, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordestgaard, B.G.; Chapman, M.J.; Humphries, S.E.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Masana, L.; Descamps, O.S.; Wiklund, O.; Hegele, R.A.; Raal, F.J.; Defesche, J.C.; et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: Guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: Consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 3478–3490a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallejo-Vaz, A.J.; Stevens, C.A.; Lyons, A.R.; Dharmayat, K.I.; Freiberger, T.; Hovingh, G.K.; Mata, P.; Raal, F.J.; Santos, R.D.; Soran, H.; et al. Global perspective of familial hypercholesterolaemia: A cross-sectional study from the EAS Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Studies Collaboration (FHSC). Lancet 2021, 398, 1713–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayikcioglu, M.; Basaran, O.; Dogan, V.; Mert, K.U.; Mert, G.O.; Ozdemir, I.H.; Rencuzogullari, I.; Karadeniz, F.O.; Tekinalp, M.; Askin, L.; et al. Misperceptions and management of LDL-cholesterol in secondary prevention of patients with familial hypercholesterolemia in cardiology practice: Real-life evidence from the EPHESUS registry. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2023, 17, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Cho, K.H.; Hong, Y.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Shin, M.H. Enhancing Familial Hypercholesterolemia Detection in South Korea: A Targeted Screening Approach Integrating National Program and Genetic Cascade Screening. Korean Circ. J. 2024, 54, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.H. Advancing Familial Hypercholesterolemia Detection and Management in South Korea. Korean Circ. J. 2024, 54, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruel, I.; Aljenedil, S.; Sadri, I.; de Varennes, E.; Hegele, R.A.; Couture, P.; Bergeron, J.; Wanneh, E.; Baass, A.; Dufour, R.; et al. Imputation of Baseline LDL Cholesterol Concentration in Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia on Statins or Ezetimibe. Clin. Chem. 2018, 64, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, W.C. The rule of 5 and the rule of 7 in lipid-lowering by statin drugs. Am. J. Cardiol. 1997, 80, 106–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ose, L.; Budinski, D.; Hounslow, N.; Arneson, V. Comparison of pitavastatin with simvastatin in primary hypercholesterolaemia or combined dyslipidaemia. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2009, 25, 2755–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrone, D.; Weintraub, W.S.; Toth, P.P.; Hanson, M.E.; Lowe, R.S.; Lin, J.; Shah, A.K.; Tershakovec, A.M. Lipid-altering efficacy of ezetimibe plus statin and statin monotherapy and identification of factors associated with treatment response: A pooled analysis of over 21,000 subjects from 27 clinical trials. Atherosclerosis 2012, 223, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, N.; Koenig, W. Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Pitfalls and Challenges in Diagnosis and Treatment. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 24, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groselj, U.; Wiegman, A.; Gidding, S.S. Screening in children for familial hypercholesterolaemia: Start now. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3209–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khera, A.V.; Won, H.H.; Peloso, G.M.; Lawson, K.S.; Bartz, T.M.; Deng, X.; van Leeuwen, E.M.; Natarajan, P.; Emdin, C.A.; Bick, A.G.; et al. Diagnostic Yield and Clinical Utility of Sequencing Familial Hypercholesterolemia Genes in Patients with Severe Hypercholesterolemia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 2578–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagahara, K.; Nishibukuro, T.; Ogiwara, Y.; Ikegawa, K.; Tada, H.; Yamagishi, M.; Kawashiri, M.A.; Ochi, A.; Toyoda, J.; Nakano, Y.; et al. Genetic Analysis of Japanese Children Clinically Diagnosed with Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2022, 29, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Wang, D.; Patel, K.; Whittall, R.; Wood, G.; Farrer, M.; Neely, R.D.; Fairgrieve, S.; Nair, D.; Barbir, M.; et al. Mutation detection rate and spectrum in familial hypercholesterolaemia patients in the UK pilot cascade project. Clin. Genet. 2010, 77, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umans-Eckenhausen, M.A.; Defesche, J.C.; Sijbrands, E.J.; Scheerder, R.L.; Kastelein, J.J. Review of first 5 years of screening for familial hypercholesterolaemia in the Netherlands. Lancet 2001, 357, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdieh, N.; Heshmatzad, K.; Rabbani, B. A systematic review of LDLR, PCSK9, and APOB variants in Asia. Atherosclerosis 2020, 305, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R.; O’Kane, M.; McGilligan, V.; Watterson, S. The genetics and screening of familial hypercholesterolaemia. J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 23, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plon, S.; Jarvik, G. Ten Years of Incidental, Secondary, and Actionable Findings. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1813–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada-Shiba, M.; Arai, H.; Ohmura, H.; Okazaki, H.; Sugiyama, D.; Tada, H.; Dobashi, K.; Matsuki, K.; Minamino, T.; Yamashita, S.; et al. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Adult Familial Hypercholesterolemia 2022. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2023, 30, 558–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Lee, C.J.; Kim, D.I.; Rhee, M.Y.; Lee, B.K.; Ahn, Y.; Cho, B.R.; Woo, J.T.; Hur, S.H.; Jeong, J.O.; et al. Target achievement with maximal statin-based lipid-lowering therapy in Korean patients with familial hypercholesterolemia: A study supported by the Korean Society of Lipid and Atherosclerosis. Clin. Cardiol. 2017, 40, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, S.; Masuda, D.; Harada-Shiba, M.; Arai, H.; Bujo, H.; Ishibashi, S.; Daida, H.; Koga, N.; Oikawa, S. Effectiveness and Safety of Lipid-Lowering Drug Treatments in Japanese Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Familial Hypercholesterolemia Expert Forum (FAME) Study. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2022, 29, 608–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez de Isla, L.; Alonso, R.; Watts, G.F.; Mata, N.; Saltijeral Cerezo, A.; Muniz, O.; Fuentes, F.; Diaz-Diaz, J.L.; de Andres, R.; Zambon, D.; et al. Attainment of LDL-Cholesterol Treatment Goals in Patients With Familial Hypercholesterolemia: 5-Year SAFEHEART Registry Follow-Up. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 1278–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.A.; Park, H.J. New Therapeutic Approaches to the Treatment of Dyslipidemia 2: LDL-C and Lp(a). J. Lipid Atheroscler. 2023, 12, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duell, P.B.; Banach, M.; Catapano, A.L.; Laufs, U.; Mancini, G.B.J.; Ray, K.K.; Broestl, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, L.; Goldberg, A.C. Efficacy and safety of bempedoic acid in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: Analysis of pooled patient-level data from phase 3 clinical trials. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2024, 18, e153–e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, R.; Arroyo-Olivares, R.; Muniz-Grijalvo, O.; Diaz-Diaz, J.L.; Munoz-Torrero, J.S.; Romero, M.J.; de Andres, R.; Zambon, D.; Manas, M.D.; Fuentes-Jimenez, F.; et al. Persistence with long-term PCSK9 inhibitor treatment and its effectiveness in familial hypercholesterolaemia: Data from the SAFEHEART study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2023, 30, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).