Abstract

Background: The world health goal of eliminating tuberculosis (TB) is heavily hinged on timely and efficient diagnosis and treatment. The interferon-γ release assays (I.G.R.A.s) can diagnose Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and offer an alternative to the centuries-old tuberculin skin test (T.S.T.). Yet there is disagreement over replacing the T.S.T. with I.G.R.A.s as a standard tool. Objective: We aim to assess the diagnostic ability of I.G.R.A.s compared with T.S.T. for detecting active TB cases. Methods: A systematic review identified relevant studies from four databases. In the diagnostic meta-analysis conducted with OpenMeta Analyst software, we calculated the sensitivity (SN) and specificity (SP) for active TB detection via I.G.R.A. and T.S.T. methods compared to TB culture. Results included pooled estimates for SN and SP with 95% confidence intervals (CI), stratified by age, immunity, I.G.R.A. type, and T.S.T. cut-off. Results: Our meta-analysis revealed that TB diagnosis using T.S.T. showed an SN of 72.4% and SP of 79.3%, while I.G.R.A. demonstrated higher accuracy with an SN of 78.9% and SP of 85.7%. Subgroup analysis by age indicated that I.G.R.A. consistently outperformed T.S.T. in both adult and pediatric populations. Among immunocompromised individuals, T.S.T. had low SN (23%) but high SP (91.2%), whereas I.G.R.A. had higher SN (65.6%) but lower SP (81.9%). Immunocompetent subjects showed that T.S.T. had SN of 72% and SP of 87.3%, while I.G.R.A. had higher SN (82.9%) and SP (89.1%). Evaluation by I.G.R.A. type revealed that T-SPOT.GIT demonstrated a higher SN but lower SP compared to QFT-GIT. Assessing T.S.T. cut-offs, SP was highest (88.8%) at ≥15 mm, while SN peaked (71.6%) at ≥5 mm. Conclusions: I.G.R.A. consistently showed higher diagnostic accuracy than T.S.T. across most studied subgroups, indicating its potential superiority in active TB diagnosis.

1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), a preventable and typically curable disease, remains a significant global health concern. Despite advancements in medicine, it was the second leading cause of death from a single infectious agent in 2022, surpassed only by COVID-19, and resulted in nearly double the number of deaths compared to HIV/AIDS [1]. Over 10 million new cases of TB are reported annually, underscoring the urgent need for action. Ending the global TB epidemic by 2030 is a crucial goal adopted by all Member States of the United Nations and the World Health Organization, requiring immediate and concerted efforts to achieve this target [1].

Ending TB as a public-health problem requires early diagnosis and effective treatment of active cases. Although the direct detection of TB bacilli in sputum through microscopy, culture growth or molecular tests remains the gold standard of diagnosis, they do not rule out TB in every patient suspected to be infected. In the case of patients with negative acid-resistant bacillus sputum smear microscopy, diagnosis and treatment decisions become challenging. Often, further TB diagnosis and effective management of active infections require other approaches [1,2].

The tuberculin skin test (T.S.T.) has remained a keystone of the public-health strategy for detecting LTBI and active TB due to its low cost, ease of use and limited cross-reactivity. However, its use has been limited by a high likelihood of false-positive results arising from prior Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination or infection with non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) pathogens, and patients routinely undergo further testing to rule out these disorders. Recently, interferon-γ release assays (I.G.R.A.s) have emerged as the newest generation of testing to screen for infection with M tuberculosis. Both the commercially available T-SPOT.TB test and QuantiFERON-TB Gold assays exploit the unique M tuberculosis proteins absent in BCG and most environmental mycobacteria to improve specificity, largely overcoming the limitations of the T.S.T. [3,4].

Several meta-analyses have shown significantly improved sensitivity and specificity of I.G.R.A.s over the T.S.T. for detection of TB infection, but the stability of these diagnostic procedures remained unsettled [5,6,7,8,9,10]. To address this, the present meta-analysis aims to compare the diagnostic performance of I.G.R.A.s and T.S.T. in detecting active TB, considering patient-specific characteristics and epidemiological factors, which have been overlooked in previous studies.

2. Methods

Our study adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and followed the recommendations outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [11,12].

2.1. Literature Search

An extensive literature search was conducted across multiple databases, including Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and Cochrane, covering publications up to May 2024. Additionally, a manual search of reference lists and meta-analyses was performed to identify further relevant citations. The search strategy involved combining various terms related to tuberculosis diagnostics, interferon-gamma release assays, and tuberculin skin tests: (“QFT” OR “T-SPOT” OR “SPOT” OR “Interferon-gamma Release Test*” OR “Release Test*, Interferon-gamma” OR “Test*, Interferon-gamma Release” OR “Interferon-gamma Release Assay*” OR “Interferon gamma Release Assay*” OR “Assay*, Interferon-gamma Release” OR “Interferon gamma Release Assay” OR “Release Assay*, Interferon-gamma” OR “I.G.R.A.”) AND (“Tuberculin Test” OR “Test, Tuberculin” OR “Tests, Tuberculin” OR “Tuberculin Tests” OR “T.S.T.” OR “PPD-B” OR “PPD B” OR “PPD-L” OR “PPD L” OR “Purified Protein Derivative of Tuberculin” OR “PPD” OR “PPD-S” OR “PPD-S” OR “PPD-CG” OR “PPD CG” OR “PPD-F” OR “PPD F”) AND (“Tuberculosis” OR “Tuberculoses” OR “Kochs Disease” OR “Koch’s Disease” OR “Koch Disease” OR “Infection*, Mycobacterium tuberculosis” OR “Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection*”).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Two independent reviewers screened references and assessed their eligibility criteria. Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) enrollment of patients with active TB infection confirmed by a positive culture, (2) utilization of both I.G.R.A. and T.S.T. for assessing active TB, with culture as the gold standard, and (3) provision of essential data allowing the calculation of true-positive, false-positive, true-negative, and false-negative values. Exclusion criteria encompassed basic research, non-English publications, inaccessible full texts, and unpublished data.

2.3. Data Collection

A standardized data extraction process was employed using an offline data extraction sheet to gather pertinent information from each included study systematically. The extracted data encompassed: the first author and publication year, study location, active patient numbers, control numbers, age categories, I.G.R.A. type, T.S.T. cut-off values, number of participants who had BCG vaccination, inclusion criteria, study conclusions, and primary outcomes.

2.4. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was systematically evaluated utilizing the QUADAS-2 instrument, which comprehensively assesses study validity across four primary domains: participant recruitment and selection, index test methodology, reference standard criteria, and study flow and timing [13]. This evaluation enabled the appraisal of both bias risk and applicability concerns within these domains.

2.5. Data Synthesis

The meta-analysis was performed using the OpenMeta Analyst software v0.24.1, an open-source tool, to synthesize data and explore sources of heterogeneity. Sensitivity (SN) and specificity (SP) for active TB detection were calculated for both the I.G.R.A. and T.S.T. methods in comparison to the gold standard (TB culture), with sensitivity defined as the ratio of true positives to the sum of true positives and false negatives. Specificity was determined by dividing true negatives by the cumulative total of true negatives and false positives. The meta-analysis provided pooled sensitivity and specificity estimates, each accompanied by 95% confidence intervals (CI). Our analysis incorporated stratification based on age, immunity status, type of I.G.R.A., and T.S.T. cut-off values. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated with I-squared (I2) and chi-squared (X2) statistics; X2 p < 0.10 and I2 ≥ 50% indicated significant heterogeneity.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

An extensive literature search yielded an initial pool of 7430 studies, which, after removing duplicates, resulted in 5030 unique articles for further evaluation. Title and abstract screening narrowed the selection to 90 records for full-text screening. Of these, 35 studies were excluded based on predefined criteria. Eventually, 55 studies met the eligibility criteria and were incorporated into our systematic review and meta-analysis, ensuring a thorough and rigorous assessment of the available evidence [4,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. The PRISMA flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

3.2. Included Studies Characteristics

Our meta-analysis aggregated data from 55 studies, comprising a total of 3382 cases of active tuberculosis. The majority of the included studies were conducted in China and India. All studies evaluated the diagnostic performance of the T.S.T. and I.G.R.A.s for active tuberculosis, although the specific I.G.R.A. type utilized differed across studies, with the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) assay being the most frequently employed. The study populations varied, with 24 studies exclusively enrolling adults, 30 studies focusing on pediatric populations, and one study [27], both adult and pediatric participants. A comprehensive summary of the included studies, including baseline characteristics. The TST cut-off values varied across studies (5 mm, 10 mm, or 15 mm). These thresholds were generally selected according to the epidemiological context: ≥5 mm was used in high-burden countries or immunocompromised patients to maximize sensitivity; ≥10 mm was commonly applied in intermediate-burden populations to balance sensitivity and specificity; and ≥15 mm was used in low-burden or BCG-vaccinated populations to reduce false positives. Several studies reported using multiple thresholds (5–15 mm) to allow comparison across settings as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary and baseline characteristics of the included studies.

3.3. Quality Assessment Results

Application of the QUADAS-2 tool revealed that the majority of included studies exhibited low applicability concerns across three domains: participant selection, index test methodology, and reference standard criteria. In contrast, assessment of bias risk indicated that most studies demonstrated a low risk of bias in the patient selection domain, whereas the index test domain was characterized by an unclear risk of bias. A detailed breakdown of these judgments is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Quality assessment of the included studies.

3.4. Diagnostic Meta-Analysis Outcomes

3.4.1. Overall

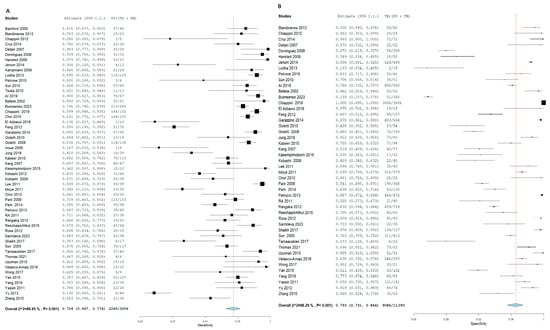

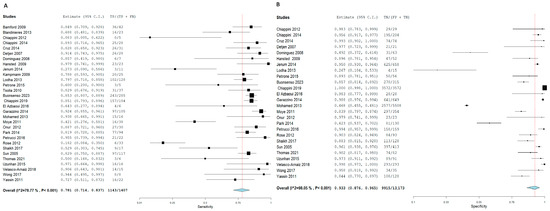

TB diagnosis via T.S.T. yielded an SN of 72.4% (95% CI: 66.7, 77.4) and an SP of 79.3% (95% CI: 73.1, 84.4). In contrast, I.G.R.A. demonstrated superior diagnostic accuracy, with an SN of 78.9% (95% CI: 74.2, 83) and an SP of 85.7% (95% CI: 81.2, 89.3). In the pooled studies for both approaches exhibited significant heterogeneity was observed across studies (I2 > 50%, p < 0.001). This heterogeneity likely reflects differences in geographic settings, the variety of IGRA platforms used, and the application of different TST cut-off values. Sensitivity analyses confirmed that our pooled estimates remained robust despite these variations.%. The high heterogeneity detected across studies highlights the influence of epidemiological setting, diagnostic platform, and threshold selection on test performance. While sensitivity analyses supported the stability of our findings, these variations must be considered when applying pooled estimates to local clinical practice, Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via T.S.T in all population.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via I.G.R.A in all population.

Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity: The red dotted line indicates the overall pooled estimate. The blue diamond represents the summary effect size with its 95% confidence interval. Each black square shows the effect estimate of an individual study, with the square size proportional to the study’s weight in the analysis. (A) Forest plot showing pooled sensitivity estimates with 95% confidence intervals for included studies. (B) Forest plot showing pooled specificity estimates with 95% confidence intervals for included studies.

3.4.2. According to Age

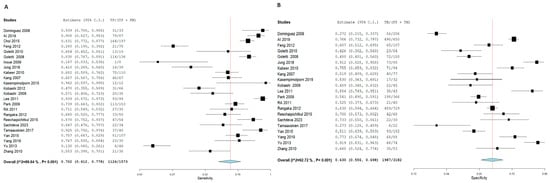

Adult

T.S.T. demonstrated an SN of 70.2% (95% CI: 61.2, 77.8) and an SP of 63% (95% CI: 55.6, 69.8) for active TB diagnosis. In contrast, I.G.R.A. exhibited superior diagnostic performance, with an SN of 82.3% (95% CI: 75.6, 87.5) and an SP of 72.5% (95% CI: 66.3, 78). Notably, significant heterogeneity was observed among the pooled studies for both approaches, characterized by χ2 p < 0.001 and I2 > 50%. Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via T.S.T in the adult population.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via I.G.R.A in the adult population.

Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity: The red dotted line indicates the overall pooled estimate. The blue diamond represents the summary effect size with its 95% confidence interval. Each black square shows the effect estimate of an individual study, with the square size proportional to the study’s weight in the analysis. (A) Forest plot showing pooled sensitivity estimates with 95% confidence intervals for included studies. (B) Forest plot showing pooled specificity estimates with 95% confidence intervals for included studies.

Children

For T.S.T., the SN and SP for Active TB diagnosis were 74.1% and 89.1%, with corresponding 95% CI of [66.6, 80.5] and [81, 94.1], respectively. On the other hand, I.G.R.A. had a higher SN and SP as follows: 78.1% and 93.3% with corresponding 95% CI of [71.4, 83.7] and [87.6, 96.5], respectively. The pooled studies in both approaches were heterogeneous, with X2-p and I2 being < 0.001 and > 50%, respectively. Figure 7 and Figure 8, respectively.

Figure 7.

Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via T.S.T in the children population.

Figure 8.

Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via I.G.R.A in the Children population.

Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity: The red dotted line indicates the overall pooled estimate. The blue diamond represents the summary effect size with its 95% confidence interval. Each black square shows the effect estimate of an individual study, with the square size proportional to the study’s weight in the analysis. (A) Forest plot showing pooled sensitivity estimates with 95% confidence intervals for included studies. (B) Forest plot showing pooled specificity estimates with 95% confidence intervals for included studies.

3.4.3. According to the Immunity Status

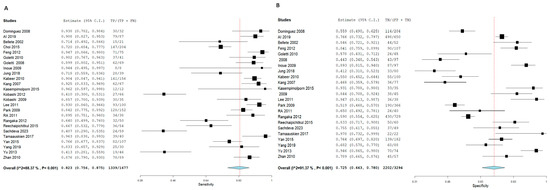

Immunocompromised

T.S.T. yielded an SN of 23% (95% CI: 8.5, 48.8) and an SP of 91.2% (95% CI: 85.5, 94.8) for active TB diagnosis. In contrast, I.G.R.A. demonstrated a higher SN of 65.6% (95% CI: 34.5, 87.3) but a lower SP of 81.9% (95% CI: 36.9, 97.2). Notably, significant heterogeneity was observed among the pooled studies for both approaches, characterized by χ2 p < 0.001 and I2 > 50%, except for the SP of T.S.T., which exhibited homogeneity with χ2-p = 0.49 and I2 = 0%. Supplementary Materials Figures S1 and S2, respectively.

Immunocompetent

For T.S.T., the SN and SP for diagnosing active TB were 72% and 87.3%, with corresponding 95% CIs of [53.1, 85.4] and [73.5, 94.5], respectively. Conversely, I.G.R.A. exhibited higher SN and SP, at 82.9% and 89.1%, with corresponding 95% CIs of [76.3, 87.9] and [76.2, 95.4], respectively. The pooled studies for both methods were heterogeneous, with X2-p < 0.001 and I2 > 50%. Supplementary Materials Figures S3 and S4, respectively.

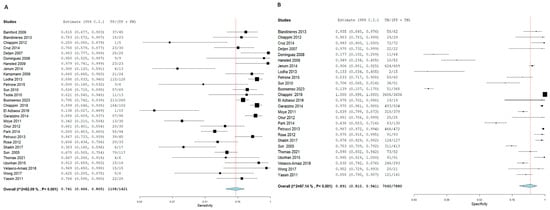

3.4.4. According to I.G.R.A. Type

In the QFT-GIT, the SN and SP for diagnosing active TB were 78.8% and 85.6%, with corresponding 95% CIs of [73.4, 83.2] and [80.3, 89.6], respectively. On the contrary, T-SPOT.GIT demonstrated a higher SN but lower SP, at 80.6% and 83.7%, with corresponding 95% CIs of [72.5, 86.8] and [73.9, 90.3], respectively. The pooled studies for both approaches were heterogeneous, with X2-p < 0.001 and I2 > 50%. Supplementary Materials Figures S5 and S6, respectively.

3.4.5. According to the T.S.T. Cut-Off Value

The diagnostic performance of T.S.T. at different induration cut-offs for active TB was evaluated. At ≥5 mm, SN and SP were 71.6% and 70.7%, respectively; at ≥10 mm, SN and SP were 70.6% and 75.8%, respectively; and at ≥15 mm, SN and SP were 62.7% and 88.8%, respectively. Heterogeneity was observed in pooled studies for all cut-offs. Collectively, the SP was highest in the subgroup with a cut-off value of ≥5 mm, reaching 88.8%. In contrast, the SN was highest in the ≥5 mm subgroup, at 71.6%. Supplementary Materials Figures S7–S9, respectively.

4. Discussion

Our diagnostic meta-analysis of 55 studies assessed active TB detection via T.S.T. and I.G.R.A. across various subgroups. Overall, I.G.R.A. showed superior accuracy over T.S.T., with higher SN and SP in most studied subgroups. Immunocompromised individuals showed varied results, with T.S.T. having higher SP but lower SN compared to I.G.R.A. Our subgroup analyses showed reduced diagnostic accuracy in immunocompromised, pediatric, and co-infected populations. In immunocompromised patients, impaired T-cell responses explain the lower sensitivity of both TST and IGRA. In children, immaturity of the immune system and higher rates of indeterminate IGRA results reduce reliability. In HIV/TB co-infected patients, immune dysregulation lowers concordance across tests. These findings highlight the importance of interpreting results within the context of patient characteristics. Reduced diagnostic accuracy in immunocompromised, pediatric, and co-infected populations can be attributed to biological and clinical factors. In immunocompromised patients, impaired T-cell responsiveness contributes to low sensitivity. In children, immature immune responses and a higher frequency of indeterminate IGRA results reduce test reliability. In HIV/TB co-infected populations, immune dysregulation limits the accuracy of both assays. These subgroup differences underscore the need for careful interpretation of diagnostic results based on patient characteristics. T-SPOT.GIT demonstrated a higher SN but lower SP compared to QFT-GIT. T.S.T.’s performance varied based on induration cut-offs, with a cut-off of ≥15 mm exhibiting the highest SP, while a cut-off of ≥5 mm had the highest SN. Our findings underscore the superior performance of I.G.R.A.s compared to the T.S.T. The heightened specificity of I.G.R.A.s translates to a reduction in false-positive results, thereby minimizing the need for additional, unnecessary tests and avoiding potential side effects from unwarranted treatments. Moreover, the enhanced sensitivity of I.G.R.A.s results in fewer false-negative outcomes, which is particularly crucial in the context of immunosuppressive therapy. Including I.G.R.A. in screening algorithms for individuals undergoing immunosuppressive treatment can potentially identify more TB infections.

The importance of early detection and intervention in tuberculosis control cannot be overstated, as it significantly contributes to successful patient outcomes and disease management [69,70,71]. However, we encounter a significant challenge with the conventional smear microscopy method for acid-fast bacilli, which often yields low detection rates, and the lengthy culture cycle required for Mycobacterium tuberculosis further impedes prompt diagnosis [69,70,71]. Consequently, the utility of microbiological techniques in this context is somewhat constrained.

T.S.T. is the recommended test for the diagnosis of tuberculosis because of the relative ease of performing it in non-laboratory settings with non-invasive procedures. In addition, it is less costly than I.G.R.A.s [72,73,74]. T.S.T. can be falsely positive in people vaccinated with the BCG vaccine or infected with non-tuberculous mycobacteria. It must be injected intradermally so that a consistent needle depth is inserted beneath the skin, and its interpretations are subjective, causing variability in results [72,73,74]. On the other hand, I.G.R.A.s require blood and specialized equipment. They are more expensive than T.S.T. and more difficult to give in low-income countries or in low-resource, non-laboratory settings. However, previous BCG vaccination or infection with non-tuberculous mycobacteria will not give false positive results with I.G.R.A.s. They also have less variability in results than T.S.T. [73,75,76,77]. However, I.G.R.A.s can be falsely indeterminate due to non-specifically high background reactivity or inadequate interferon-gamma response. If this happens, it is possible to repeat the test or to use another type of I.G.R.A. [73,75,76,77].

Our study revealed a notable variation in sensitivity and specificity across both the T.S.T. and I.G.R.A.s, which can be attributed to several factors, including epidemiological context, demographic differences, comorbidities, detection thresholds, and procedural variations. In order to minimize the heterogeneity of these factors and permit a more comparable assessment of T.S.T. versus I.G.R.A., we applied a strong selection criterion for both T.S.T. and I.G.R.A., if one was used, the other had to be as well within the same population, hence minimizing the number of studies deemed eligible. Second, by stratifying according to age groups, immunity status, type of I.G.R.A. and cut-off used for the T.S.T., we could compare the two diagnostic modalities more robustly. Significant heterogeneity was observed across studies (I2 > 50%, p < 0.001). This heterogeneity likely reflects differences in geographic settings, the variety of IGRA platforms used, and the application of different TST cut-off values. Sensitivity analyses confirmed that our pooled estimates remained robust despite these variations.

Our findings aligned with those of the UK Prognostic Evaluation of Diagnostic I.G.R.A.s Consortium (PREDICT) TB study conducted by Abubakar et al., which demonstrated the superior performance of I.G.R.A.s compared to the T.S.T. [78]. The UK PREDCTTB investigators found a greater difference in favor of the T-SPOT.TB assay. We similarly found that the T-SPOT.GIT had greater SN with a lower SP than QFT-GIT. One possible explanation for this difference could be the use of standardized cut-offs with the UK PREDCTB TB study, which could be the basis for the difference. In their 2011 study, Sester et al. compared the T.S.T. and I.G.R.A. methods by using active TB infection as a surrogate for latent TB infection (LTBI). They concluded that I.G.R.A.s demonstrated higher sensitivity compared to T.S.T. However, a direct comparison with our findings is challenging due to the differing cohorts utilized for T.S.T. and I.G.R.A. testing by Sester et al. [6]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis conducted by Diel et al. in 2010 supported the superior sensitivity of I.G.R.A.s over T.S.T. [69]. Nonetheless, direct comparability with our study is limited since only I.G.R.A.s were performed in the control population, precluding the determination of specificity [69].

Our findings, consistent with those of Dekeyser et al. and Nasiri et al., suggest that I.G.R.A.s are more sensitive and specific than T.S.T. in detecting TB infection [9,10]. In contrast, Auguste et al. (2017) found that the evidence was sparse and uncertain and did not indicate that I.G.R.A.s were superior to T.S.T. or vice versa [7]. The meta-analysis by Nasiri et al. reported pooled sensitivity and specificity values for T.S.T., QFT-G, and T-SPOT.TB, which was similar to our findings [10]. Similarly, Ai et al.’s study found that the interferon-γ release test was superior to T.S.T. as a screening tool for active tuberculosis [14]. However, our study differed from Auguste et al.’s (2019) study, which found no significant difference between I.G.R.A.s and T.S.T. in predicting progression to clinical tuberculosis [8].

This is the most extensive and updated meta-analysis comparing I.G.R.A. and T.S.T. for detecting active TB infections. Our study is distinguished by its comprehensive approach, incorporating stratifications based on age groups, immunity status, specific I.G.R.A. types, and T.S.T. cut-off points. Despite demonstrating higher accuracy, IGRA implementation faces practical challenges. Compared with TST, IGRA requires greater laboratory infrastructure, specialized equipment, and trained personnel. Costs are substantially higher, limiting feasibility in many high-burden, resource-limited settings. Policymakers should therefore evaluate cost-effectiveness and logistical feasibility before recommending IGRA as a replacement for TST. In such contexts, TST may remain the more practical option despite its lower accuracy. IGRAs require prompt sample processing and controlled laboratory conditions, which restrict their use outside urban or specialized centers. Reproducibility also varies by epidemiological context, with performance differences observed between high-prevalence and low-prevalence regions, and between rural and urban healthcare settings. These operational and contextual barriers limit the universal applicability of IGRA despite its superior accuracy. Furthermore, we applied stringent criteria by including only studies that utilized TB culture as the gold standard and those that compared I.G.R.A. and T.S.T. within the same study setting. These rigorous methods ensure the validity and consistency of our findings, offering valuable insights into the diagnostic efficacy of these tools in identifying active TB infections. While our study employed rigorous stratification methods, several limitations must be acknowledged. Future research should incorporate factors such as previous immunization and infection status by utilizing multivariate risk prediction models that account for prior TB exposure.

Emerging approaches such as machine learning may enhance TB diagnostics by integrating demographic, immunological, and epidemiological data. These predictive models could provide more nuanced interpretation of IGRA performance, particularly in populations with high BCG vaccination coverage or non-tuberculous mycobacteria exposure. This would enable a more comprehensive comparison between I.G.R.A.s and T.S.T. Additionally, the cost-effectiveness of T.S.T. and I.G.R.A. warrants consideration in upcoming studies. Other limitations include the retrospective nature of our study, potential selection bias introduced by physician discretion in choosing I.G.R.A. type and T.S.T. performance, and the lack of consideration for the endemic TB burden. To enhance the robustness of future studies, it is essential to account for these limitations and include stratification based on TB endemicity.

Future research should investigate the use of combined diagnostic strategies, such as integrating IGRAs with host biomarker panels or emerging molecular tools, to improve accuracy and provide rapid, point-of-care options. These combined approaches could enhance diagnostic precision and support global initiatives aimed at strengthening TB elimination strategies.

5. Conclusions

Our diagnostic meta-analysis reveals that I.G.R.A. outperforms T.S.T. in detecting active TB across different subgroups, but T.S.T. shows higher specificity in immunocompromised individuals. This suggests that patient characteristics should be considered when choosing a test. While our study used rigorous stratification methods, future research should address limitations such as prior TB exposure, immunization, and infection status, as well as cost-effectiveness comparisons between T.S.T. and I.G.R.A.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diagnostics15182343/s1, Figure S1: Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via T.S.T in the Immunocompromised population; Figure S2: Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via I.G.R.A in the Immunocompromised population; Figure S3: Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via T.S.T in the Immunocompetent population; Figure S4: Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via I.G.R.A in the Immunocompetent population; Figure S5: Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via QFT-GIT; Figure S6: Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via T-SPOT.TB; Figure S7: Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via T.S.T as the cut-off value is ≥5 mm; Figure S8: Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via T.S.T as the cut-off value is ≥10 mm; Figure S9: Forest plot of estimates of sensitivity and specificity for TB diagnosis via T.S.T as the cut-off value is ≥15 mm.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and M.A.T.; methodology, M.A.T., M.N.A., S.S., H.A.F. and A.B.M.; formal analysis, S.S. and H.A.F.; data curation, M.A.T., M.N.A., S.S., M.A. and A.B.M.; writing—original draft, M.A.T., M.N.A., S.S. and H.A.F.; writing—review and editing, M.A.T., M.N.A., S.S., H.A.F., M.A. and A.B.M.; supervision, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This scientific paper was derived from a research grant funded by the Research, Development, and Innovation Authority (RDIA)—Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—with the grant number (12982-iau-2023-TAU-R-3-1-HW-).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it is a systematic review and meta-analysis of previously published data.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because all data were obtained from previously published studies.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Dinnes, J.; Deeks, J.; Kunst, H.; Gibson, A.; Cummins, E.; Waugh, N.; Drobniewski, F.; Lalvani, A. A systematic review of rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of tuberculosis infection. Health Technol. Assess. 2007, 11, 1–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, M.; Zwerling, A.; Menzies, D. Systematic review: T-cell-based assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: An update. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 149, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kong, W.; Xv, N.; Huang, X.; Chen, X. Correlation between the tuberculin skin test and T-SPOT.TB in patients with suspected tuberculosis infection: A pilot study. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 2250–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Xiao, J.; Miao, Q.; Feng, W.; Wu, X.; Yin, Q.; Jiao, W.; Shen, C.; Liu, F.; Shen, D.; et al. Interferon gamma release assay in diagnosis of pediatric tuberculosis: A meta-analysis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 63, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sester, M.; Sotgiu, G.; Lange, C.; Giehl, C.; Girardi, E.; Migliori, G.B.; Bossink, A.; Dheda, K.; Diel, R.; Dominguez, J.; et al. Interferon-γ release assays for the diagnosis of active tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 37, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auguste, P.; Tsertsvadze, A.; Pink, J.; Court, R.; McCarthy, N.; Sutcliffe, P.; Clarke, A. Comparing interferon-gamma release assays with tuberculin skin test for identifying latent tuberculosis infection that progresses to active tuberculosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auguste, P.; Madan, J.; Tsertsvadze, A.; Court, R.; McCarthy, N.; Sutcliffe, P.; Taylor-Phillips, S.; Pink, J.; Clarke, A. Identifying latent tuberculosis in high-risk populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of test accuracy. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2019, 23, 1178–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keyser, E.; De Keyser, F.; De Baets, F. Tuberculin skin test versus interferon-gamma release assays for the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection. Acta Clin. Belg. 2014, 69, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, M.J.; Pormohammad, A.; Goudarzi, H.; Mardani, M.; Zamani, S.; Migliori, G.B.; Sotgiu, G. Latent tuberculosis infection in transplant candidates: A systematic review and meta-analysis on TST and IGRA. Infection 2019, 47, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.G.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, L.; Feng, P.; Chen, D.; Chen, S.; Xu, H. Clinical value of interferon-γ release assay in the diagnosis of active tuberculosis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 1253–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azbaoui, S.E.; Sabri, A.; Ouraini, S.; Hassani, A.; Asermouh, A.; Agadr, A.; Abilkassem, R.; Dini, N.; Kmari, M.; Akhaddar, A.; et al. Utility of the QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube assay for the diagnosis of tuberculosis in Moroccan children. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2016, 20, 1639–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamford, A.R.J.; Crook, A.M.; Clark, J.E.; Nademi, Z.; Dixon, G.; Paton, J.Y.; Riddell, A.; Drobniewski, F.; Riordan, A.; Anderson, S.T.; et al. Comparison of interferon- release assays and tuberculin skin test in predicting active tuberculosis (TB) in children in the UK: A paediatric TB network study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2010, 95, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellete, B.; Coberly, J.; Barnes, G.L.; Ko, C.; Chaisson, R.E.; Comstock, G.W.; Bishai, W.R. Evaluation of a Whole-Blood Interferon-g Release Assay for the Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection in 2 Study Populations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Blandinières, A.; De Lauzanne, A.; Guérin-El Khourouj, V.; Gourgouillon, N.; See, H.; Pédron, B.; Faye, A.; Sterkers, G. QuantiFERON to diagnose infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Performance in infants and older children. J. Infect. 2013, 67, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boom, J.A.; Tate, J.E.; Sahni, L.C.; Rench, M.A.; Quaye, O.; Mijatovic-Rustempasic, S.; Patel, M.M.; Baker, C.J.; Parashar, U.D. Sustained Protection from Pentavalent Rotavirus Vaccination During The Second Year of Life AT A Large, Urban United States Pediatric Hospital. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2010, 29, 1133–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonsenso, D.; Noguera-Julian, A.; Moroni, R.; Hernández-Bartolomé, A.; Fritschi, N.; Lancella, L.; Cursi, L.; Soler-Garcia, A.; Krüger, R.; Feiterna-Sperling, C.; et al. Performance of QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus assays in paediatric tuberculosis: A multicentre PTBNET study. Thorax 2023, 78, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappini, E.; Storelli, F.; Tersigni, C.; Venturini, E.; de Martino, M.; Galli, L. QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test performance in a large pediatric population investigated for suspected tuberculosis infection. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2019, 32, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappini, E.; Bonsignori, F.; Mazzantini, R.; Sollai, S.; Venturini, E.; Mangone, G.; Cortimiglia, M.; Olivito, B.; Azzari, C.; Galli, L.; et al. Interferon-Gamma Release Assay Sensitivity in Children Younger Than 5 Years is Insufficient To Replace The Use of Tuberculin Skin Test In Western Countries. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2014, 33, 1291–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappini, E.; Della Bella, C.; Bonsignori, F.; Sollai, S.; Amedei, A.; Galli, L.; Niccolai, E.; Del Prete, G.; Singh, M.; D’Elios, M.M.; et al. Potential Role of M. tuberculosis Specific IFN-γ and IL-2 ELISPOT Assays in Discriminating Children with Active or Latent Tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.C.; Jarlsberg, L.G.; Grinsdale, J.A.; Osmond, D.H.; Higashi, J.; Hopewell, P.C.; Kato-Maeda, M. Reduced sensitivity of the QuantiFERON® test in diabetic patients with smear-negative tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2015, 19, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.T.; Geltemeyer, A.M.; Starke, J.R.; Flores, J.A.; Graviss, E.A.; Smith, K.C. Comparing the Tuberculin Skin Test and T-SPOT.TB Blood Test in Children. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e31–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detjen, A.K.; Keil, T.; Roll, S.; Hauer, B.; Mauch, H.; Wahn, U.; Magdorf, K. Interferon- Release Assays Improve the Diagnosis of Tuberculosis and Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease in Children in a Country with a Low Incidence of Tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 45, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domınguez, J.; Ruiz-Manzano, J.; Souza-Galvao, M.D.; Latorre, I.; Mila, C.; Blanco, S.; Jiménez, M.A.; Prat, C.; Lacoma, A.; Altet, N.; et al. Comparison of Two Commercially Available Gamma Interferon Blood Tests for Immunodiagnosis of Tuberculosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2008, 15, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Diao, N.; Shao, L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S.; Jin, J.; Wang, F.; Weng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W. Interferon-Gamma Release Assay Performance in Pulmonary and Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garazzino, S.; Galli, L.; Chiappini, E.; Pinon, M.; Bergamini, B.M.; Cazzato, S.; Dal Monte, P.; Dodi, I.; Lancella, L.; Esposito, S.; et al. Performance of interferon-γ Release Assay for the Diagnosis of Active or Latent Tuberculosis in Children in the First 2 Years of Age: A Multicenter Study of the Italian Society of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2014, 33, e226–e231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goletti, D.; Raja, A.; Kabeer, B.S.A.; Rodrigues, C.; Sodha, A.; Butera, O.; Carrara, S.; Vernet, G.; Longuet, C.; Ippolito, G.; et al. IFN-γ, but not IP-10, MCP-2 or IL-2 response to RD1 selected peptides associates to active tuberculosis. J. Infect. 2010, 61, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goletti, D.; Stefania, C.; Butera, O.; Amicosante, M.; Ernst, M.; Sauzullo, I.; Vullo, V.; Cirillo, D.; Borroni, E.; Markova, R.; et al. Accuracy of Immunodiagnostic Tests for Active Tuberculosis Using Single and Combined Results: A Multicenter TBNET-Study. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansted, E.; Andriuskeviciene, A.; Sakalauskas, R.; Kevalas, R.; Sitkauskiene, B. T-cell-based diagnosis of tuberculosis infection in children in Lithuania: A country of high incidence despite a high coverage with bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination. BMC Pulm. Med. 2009, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Nakamura, T.; Katsuma, A.; Masumoto, S.; Minami, E.; Katagiri, D.; Hoshino, T.; Shibata, M.; Tada, M.; Hinoshita, F. The value of QuantiFERON®TB-Gold in the diagnosis of tuberculosis among dialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 2252–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jenum, S.; Selvam, S.; Mahelai, D.; Jesuraj, N.; Cárdenas, V.; Kenneth, J.; Hesseling, A.C.; Doherty, T.M.; Vaz, M.; Grewal, H.M.S. Influence of Age and Nutritional Status on the Performance of the Tuberculin Skin Test and QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube in Young Children Evaluated for Tuberculosis in Southern India. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2014, 33, e260–e269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.Y.; Lim, J.E.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.M.; Cho, S.-N.; Kim, S.K.; Chang, J.; Kang, Y.A. Questionable role of interferon-γ assays for smear-negative pulmonary TB in immunocompromised patients. J. Infect. 2012, 64, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampmann, B.; Whittaker, E.; Williams, A.; Walters, S.; Gordon, A.; Martinez-Alier, N.; Williams, B.; Crook, A.M.; Hutton, A.-M.; Anderson, S.T. Interferon-γ release assays do not identify more children with active tuberculosis than the tuberculin skin test. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 33, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.A.; Lee, H.W.; Hwang, S.S.; Um, S.-W.; Han, S.K.; Shim, Y.-S.; Yim, J.-J. Usefulness of Whole-Blood Interferon-γ Assay and Interferon-γ Enzyme-Linked Immunospot Assay in the Diagnosis of Active Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Chest 2007, 132, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasempimolporn, S. Performance of a Rapid Strip Test for the Serologic Diagnosis of Latent Tuberculosis in Children. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, DC11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobashi, Y.; Abe, M.; Mouri, K.; Obase, Y.; Miyashita, N.; Oka, M. Usefulness of Tuberculin Skin Test and Three Interferon-Gamma Release Assays for the Differential Diagnosis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Intern. Med. 2012, 51, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobashi, Y.; Mouri, K.; Yagi, S.; Obase, Y.; Miyashita, N.; Oka, M. Clinical utility of a T cell-based assay in the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Respirology 2009, 14, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.E.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, S.W. The clinical utility of tuberculin skin test and interferon-γ release assay in the diagnosis of active tuberculosis among young adults: A prospective observational study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodha, R.; Mukherjee, A.; Saini, D.; Saini, S.; Singh, V.; Singh, S.; Grewal, H.M.S.; Kabra, S.K.; Delhi Tb Study Group. Role of the QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube test in the diagnosis of intrathoracic childhood tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2013, 17, 1383–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahomed, H.; Ehrlich, R.; Hawkridge, T.; Hatherill, M.; Geiter, L.; Kafaar, F.; Abrahams, D.A.; Mulenga, H.; Tameris, M.; Geldenhuys, H.; et al. Screening for TB in high school adolescents in a high burden setting in South Africa. Tuberculosis 2013, 93, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, S.; Isaacs, F.; Gelderbloem, S.; Verver, S.; Hawkridge, A.J.; Hatherill, M.; Tameris, M.; Geldenhuys, H.; Workman, L.; Pai, M.; et al. Tuberculin skin test and QuantiFERON® assay in young children investigated for tuberculosis in South Africa. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2011, 15, 1176–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onur, H.; Hatipoğlu, S.; Arıca, V.; Hatipoğlu, N.; Arıca, S.G. Comparison of Quantiferon Test with Tuberculin Skin Test for the Detection of Tuberculosis Infection in Children. Inflammation 2012, 35, 1518–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Park, H.; Shin, J.A.; Kim, H.J.; Ahn, C.M.; Chang, Y.S. Whole Blood Interferon-γ Release Assay Is Insufficient for the Diagnosis of Sputum Smear Negative Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Yonsei Med. J. 2014, 55, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Park, S.Y.; Jeon, K.; Um, S.-W.; Kwon, O.J.; Kang, E.-S.; Koh, W.-J. Clinical utility of the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test for the diagnosis of active pulmonary tuberculosis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 41, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrone, L.; Cannas, A.; Aloi, F.; Nsubuga, M.; Sserumkuma, J.; Nazziwa, R.A.; Jugheli, L.; Lukindo, T.; Girardi, E.; Reither, K.; et al. Blood or Urine IP-10 Cannot Discriminate between Active Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases Different from Tuberculosis in Children. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 589471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, R.; Lombardi, G.; Corsini, I.; Reggiani, M.L.B.; Visciotti, F.; Bernardi, F.; Landini, M.P.; Cazzato, S.; Dal Monte, P. Quantiferon-TB Gold In-Tube Improves Tuberculosis Diagnosis in Children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2017, 36, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ra, S.W.; Lyu, J.; Choi, C.-M.; Oh, Y.-M.; Lee, S.-D.; Kim, W.S.; Kim, D.S.; Shim, T.S. Distinguishing tuberculosis from Mycobacterium avium complex disease using an interferon-gamma release assay. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2011, 15, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaka, M.X.; Gideon, H.P.; Wilkinson, K.A.; Pai, M.; Mwansa-Kambafwile, J.; Maartens, G.; Glynn, J.R.; Boulle, A.; Fielding, K.; Goliath, R.; et al. Interferon release does not add discriminatory value to smear-negative HIV-tuberculosis algorithms. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 39, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reechaipichitkul, W.; Pimrin, W.; Bourpoern, J.; Prompinij, S.; Faksri, K. Evaluation of the QuantiFERON?-TB Gold In-Tube assay and tuberculin skin test for the diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in northeastern Thailand. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2015, 33, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.V.; Kimaro, G.; Nissen, T.N.; Kroidl, I.; Hoelscher, M.; Bygbjerg, I.C.; Mfinanga, S.G.; Ravn, P. QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube Performance for Diagnosing Active Tuberculosis in Children and Adults in a High Burden Setting. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, K.; Kumar, P.; Kante, B.; Vuyyuru, S.K.; Mohta, S.; Ranjan, M.K.; Singh, M.K.; Verma, M.; Makharia, G.; Kedia, S.; et al. Interferon-gamma release assay has poor diagnostic accuracy in differentiating intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease in tuberculosis endemic areas. Intest. Res. 2023, 21, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, N.; Gupte, A.; Dharmshale, S.; Pokkali, S.; Thakar, M.; Upadhye, V.J.; Ordonez, A.A.; Kinikar, A.; Gupte, N.; Mave, V.; et al. Novel interferon-gamma assays for diagnosing tuberculosis in young children in India. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2017, 21, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Tian, J.; Yin, Q.; Xiao, J.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Feng, G.; Peng, X.; Qi, H.; Xu, F.; et al. Performance of the Interferon Gamma Release Assays in Tuberculosis Disease in Children Five Years Old or Less. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yan, H.; Hu, Y.; Jiao, W.; Gu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Li, H.; Jiao, A.; Guo, Y.; Shen, A.-d. IFN-γ release assay: A diagnostic assistance tool of tuberculin skin test in pediatric tuberculosis in China. Chin. Med. J. 2010, 123, 2786–2791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Syed Ahamed Kabeer, B.; Raman, B.; Thomas, A.; Perumal, V.; Raja, A. Role of QuantiFERON-TB Gold, Interferon Gamma Inducible Protein-10 and Tuberculin Skin Test in Active Tuberculosis Diagnosis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamašauskienė, L.; Hansted, E.; Vitkauskienė, A.; Miliauskas, S.; Naudžiūnas, A.; Šitkauskienė, B. Use of interferon-gamma release assay and tuberculin skin test in diagnosing tuberculosis in Lithuanian adults: A comparative analysis. Medicina 2017, 53, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Verghese, V.P.; Chacko, A.; Michael, J.S.; Jeyaseelan, V. Accuracy and agreement of the Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) and the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-tube test (QFT) in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in Indian children. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 40, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunhan, O.; Törün, S.H.; Somer, A.; Salman, N.; Köksalan, K. Comparison of tuberculin skin test and QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube for the diagnosis of childhood tuberculosis. Pediatr. Int. 2015, 57, 893–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Arnaiz, E.; Soriano-Arandes, A.; Latorre, I.; Altet, N.; Domínguez, J.; Fortuny, C.; Monsonís, M.; Tebruegge, M.; Noguera-Julian, A. Performance of Tuberculin Skin Tests and Interferon-γ Release Assays in Children Younger Than 5 Years. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2018, 37, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.-S.; Huang, Y.-C.; Hu, H.-C.; Huang, Y.-C.; Wen, C.-H.; Lin, T.-Y. Diagnostic utility of QuantiFERON–TB Gold In-Tube test in pediatric tuberculosis disease in Taiwanese children. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2017, 50, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yan, L.; Xiao, H.; Han, M.; Zhang, Q. Diagnostic value of T-SPOT.TB interferon-γ release assays for active tuberculosis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 10, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, M.A.; Petrucci, R.; Garie, K.T.; Harper, G.; Arbide, I.; Aschalew, M.; Merid, Y.; Kebede, Z.; Bawazir, A.A.; Abuamer, N.M.; et al. Can Interferon-Gamma or Interferon-Gamma-Induced-Protein-10 Differentiate Tuberculosis Infection and Disease in Children of High Endemic Areas? PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W.; Wu, H.; Chen, M.; Hua, W.; Wang, H.; Wei, T.; Jiao, Y.; Sun, G.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of Interferon-Gamma Releasing Assay in HIV-Infected Patients in China. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Shao, L.; Mo, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Meng, C.; Zhong, M.; Qiu, L.; Wu, M.; Weng, X.; et al. Evaluation of Gamma Interferon Release Assays Using Mycobacterium tuberculosis Antigens for Diagnosis of Latent and Active Tuberculosis in Mycobacterium bovis BCG-Vaccinated Populations. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2010, 17, 1985–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolia, M.N.; Mavrikou, M.; Critselis, E.; Papadopoulos, N.G.; Makrinioti, H.; Spyridis, N.P.; Kafetzis, D.A. Whole blood interferon-γ release assay is a useful tool for the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection particularly among Bacille Calmette Guèrin-vaccinated children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2010, 29, 1137–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diel, R.; Loddenkemper, R.; Nienhaus, A. Evidence-based comparison of commercial interferon-γ release assays for detecting active TB: A metaanalysis. Chest 2010, 137, 952–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galloway, K.M.; Parker, R. Could an increase in vigilance for spinal tuberculosis at primary health care level, enable earlier diagnosis at district level in a tuberculosis endemic country? Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2018, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenti, P.; Raponi, M.; de Waure, C.; Marino, M.; Ricciardi, W.; Damiani, G. Performance of interferon-γ release assays in the diagnosis of confirmed active tuberculosis in immunocompetent children: A new systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldenhuys, H.; Verver, S.; Surtie, S.; Hatherill, M.; van Leth, F.; Kafaar, F.; Tameris, M.; Kleynhans, W.; Luabeya, K.K.; Moyo, S.; et al. The tuberculin skin test: A comparison of ruler and calliper readings. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2010, 14, 1266–1271. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, L.M.; Grenier, J.; Schumacher, S.G.; Denkinger, C.M.; Steingart, K.R.; Pai, M. Immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis: State of the art. Med. Princ. Pract. 2012, 21, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ATS/CDC. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. American Thoracic Society. MMWR Recomm. Rep. Morb. 2000, 49, 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek, G.H.; Jereb, J.; Vernon, A.; LoBue, P.; Goldberg, S.; Castro, K.; IGRA Expert Committee; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated guidelines for using Interferon Gamma Release Assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection—United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2010, 59, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Oni, T.; Gideon, H.P.; Bangani, N.; Tsekela, R.; Seldon, R.; Wood, K.; Wilkinson, K.A.; Goliath, R.T.; Ottenhoff, T.H.M.; Wilkinson, R.J. Risk factors associated with indeterminate gamma interferon responses in the assessment of latent tuberculosis infection in a high-incidence environment. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012, 19, 1243–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfield, S.; Pascoe, E.; Thambiran, A.; Siafarikas, A.; Burgner, D. Factors associated with the performance of a blood-based interferon-γ release assay in diagnosing tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, I.; Drobniewski, F.; Southern, J.; Sitch, A.J.; Jackson, C.; Lipman, M.; Deeks, J.J.; Griffiths, C.; Bothamley, G.; Lynn, W.; et al. Prognostic value of interferon-γ release assays and tuberculin skin test in predicting the development of active tuberculosis (UK PREDICT TB): A prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).