Abstract

The purpose of this research was to provide a “systematic literature review” of knee bone reports that are obtained by MRI, CT scans, and X-rays by using deep learning and machine learning techniques by comparing different approaches—to perform a comprehensive study on the deep learning and machine learning methodologies to diagnose knee bone diseases by detecting symptoms from X-ray, CT scan, and MRI images. This study will help those researchers who want to conduct research in the knee bone field. A comparative systematic literature review was conducted for the accomplishment of our work. A total of 32 papers were reviewed in this research. Six papers consist of X-rays of knee bone with deep learning methodologies, five papers cover the MRI of knee bone using deep learning approaches, and another five papers cover CT scans of knee bone with deep learning techniques. Another 16 papers cover the machine learning techniques for evaluating CT scans, X-rays, and MRIs of knee bone. This research compares the deep learning methodologies for CT scan, MRI, and X-ray reports on knee bone, comparing the accuracy of each technique, which can be used for future development. In the future, this research will be enhanced by comparing X-ray, CT-scan, and MRI reports of knee bone with information retrieval and big data techniques. The results show that deep learning techniques are best for X-ray, MRI, and CT scan images of the knee bone to diagnose diseases.

1. Introduction

This section gives a brief introduction to our study to elaborate on the all-important aspects related to the knee bone, knee bone diseases, and screening techniques, i.e., MRI, CT scans, and X-rays. This section also explains the importance of deep learning and machine learning techniques for medical image processing. The following subsections constitute an overview of our research.

1.1. Structure of Human Knee

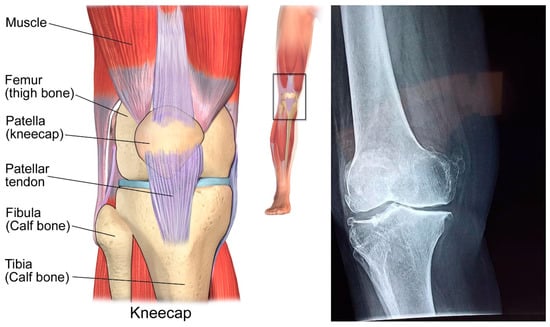

There are many joints in the human body, but the knee joint has a very important role among all the joints as it is the largest joint. Its purpose is to provide a crucial point between the thigh and the lower leg during development. It comprises bones (the femur, tibia, and patella), which are connected by the articular surfaces of the hyaline ligament (tibiofemoral and patellofemoral).

The femur cooperates with the tibia in two important zones: average (closer to the midline of the body) and parallel (far from the middle). Figure 1 demonstrates an attractive reverberation picture of the knee in a sagittal plane from an anatomical chartbook for reference. The ligament is noticeable as a splendid thin layer covering the bones.

Figure 1.

Structure of human knee.

The fat in this picture has been overemphasised, to make the ligament more conspicuous among the encompassing tissues. Splendid mass adjoins the femoral and tibial ligaments in the muscles [1].

1.2. Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is the most widely recognized type of joint pain in the knee. It is a degenerative, “wear-and-tear” sort of joint pain that happens regularly in individuals that are 50 years old and older; however, it may happen in more youthful individuals as well. In osteoarthritis, the ligament in the knee joint erodes step by step.

It is believed that as many as 30% of the general population older than 65 will eventually develop Osteoarthritis OA over time [1].

1.3. Screening Techniques

Tragically, the standard treatment for OA today does not completely fix the malady. It is subsequently of most significance to detect the degeneration of the ligament at the beginning before it becomes irreversible.

There are several approaches to determining the level of ligament degeneration in patients.

1.3.1. Radiography (X-ray)

Over the previous decades, X-rays of the joint space width (JSW) have been the customary technique for OA screening. They offer significant advantages over arthroscopy since they are non-obtrusive and can be performed again if necessary. Among the inconveniences of X-ray imaging is the lack of accuracy for momentary examinations, because of the way in which changes in the ligament must be determined through X-ray pictures over 2–3 years [1].

1.3.2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI is an almost new standard strategy for the screening of the ligament since it does not utilize ionizing radiation, is non-intrusive and repeatable, and gives decent picture quality with high contrast and detail. X-rays convey pictures in an advanced format, which can be stored and effectively recovered, and offer an assortment of parameters for ideal picture procurement. The drawbacks include the staggering expense of the device (particularly for high field quality magnets), the long examination times, and the inclination to image ancient rarities.

1.3.3. Computed Tomography (CT scan)

A CT scan is just like an X-ray that produces cross-sectional pictures of a particular site in one’s body. For instance, a CT output of one’s knee would enable specialists to analyze illness or investigate wounds on one’s knee.

A CT scanner circles the body and sends pictures to a PC. The PC utilizes these pictures to make the point by point pictures. This enables specialists and preparedness experts to see the muscles, ligaments, tendons, vessels, and bones that make up one’s knee.

A CT scan is, likewise, sometimes alluded to as a CAT scan. The output is obtained at a clinic or a specific outpatient testing office.

1.4. Deep Learning in Medical Image Processing

In previous years, deep learning gained immense consideration by showing promising outcomes for some best-in-class methodologies, for example, discourse acknowledgment, manually written character acknowledgment, picture characterization, identification, and division. There are desires to use deep learning to enhance or create restorative picture examination applications, for example, PC-assisted conclusions, picture enlistment, multi-modular picture investigation, picture division, and recovery. There have been some applications that utilize deep learning in restorative applications like cell following and organ disease location. Specialists utilize attractive reverberation pictures as successful instruments to determine infections [2].

1.5. Machine Learning in Medical Image Processing

Machine learning is an incredible method for identifying patterns in therapeutic pictures; be that as it may, it must be utilized with caution since it may very well be abused if the qualities and shortcomings of this innovation are not comprehended.

Machine learning is a procedure for identifying patterns that can be associated with medical pictures. Although it is an amazing asset that can help in drawing medical conclusions, it tends to be biased. Machine adaptation regularly starts with the machine learning calculation framework determining the picture inclusions that are accepted to be of significance in making the forecast or coming to a conclusion. The machine learning calculation framework at that point recognizes the best mix of these picture highlights for ordering the picture or determining some measurement for the given picture locale. There are a few techniques that can be utilized, each with various qualities and shortcomings. There are open-source forms of the greater part of these machine learning strategies that make them simple to attempt and apply to pictures. A few measurements for estimating the execution of a calculation exist; in any case, one must know about the conceivably related entanglements that can bring about deluding measurements. Recently, machine learning has begun to be utilized more often; this strategy has the advantage that it does not require picture highlight distinguishing and computation as an initial step; rather, highlights are recognized as a component of the learning procedure. Machine learning has been utilized in restorative imaging and will have a more prominent impact in the future. Those working in medical imaging must know about how machine learning functions [3].

1.6. Purpose of the Study

Machine and deep learning algorithms are quickly developing a unique exploration of clinical imaging. These techniques have a huge amount of algorithms that can be used for medical imaging to detect the symptoms of diseases at very early stages. These programming techniques use supervised and unsupervised algorithms that can predict diseases from medical images—i.e., X-rays MRIs, and CT scans—by using a huge number of datasets. To date, considerable endeavors have been made for the improvement of clinical imaging applications utilizing these algorithms to analyze the mistakes in infection indicative frameworks that may bring about very vague clinical indications. This paper gives a review and comparison of clinical imaging in the machine and deep learning strategies to unambiguously dissect diseases of the knee bone. It conveys thoughts concerning the set-up of these algorithms that can be utilized for the examination of diseases and programmed decision making. Some techniques can provide the best results by using machine learning methodologies, and some can provide better accuracy by using deep learning methodologies. Thus, in this review paper, we compare the deep and machine learning algorithms with different forms of medical imaging—i.e., X-rays, CT scans, and MRI—to conclude which techniques are more accurate for this imaging.

1.7. Reviews and Hypothesis

We reviewed 32 papers for our comparison. From these, six papers relate to deep learning techniques for knee bone X-rays, five papers relate to deep learning techniques for MRI, and five relate to CT scans with deep learning techniques. Similarly, we selected six papers for X-ray imaging with machine learning techniques, five for CT scan imaging, and five for MRI with machine learning techniques.

We extracted image types, datasets, knee bone disease statuses, and accuracies from each paper regarding deep learning and machine learning. For the results, we compared the accuracy of these techniques and determined the results by calculating their average percentages. According to our results, we concluded that deep learning techniques provide more accuracy than machine learning for X-ray, MRI, and CT scan images of knee bones.

2. Related Work

A lot of work has performed in the knee bone field by using reported data of MRI, X-rays, and CT scans by using the deep learning and machine learning techniques, some of which is described below.

In the present review, the authors describe methodology for naturally diagnosing and reviewing knee OA from plain radiographs. Rather than past examinations, their model uses explicit highlights significant for the ailment. Besides, considering the recently described methodologies, their technique accomplishes the best multi-class grouping results, despite having an alternate testing set that shows 66.7% precision [4].

The researchers of this research created and assessed a programmed 3D deformable methodology for knee MRI having force inhomogeneity. They showed that the underlying point can be resolved, depending on the histogram from earlier learning. It is additionally striking that no preparation stage is required, dissimilarly to other custom deformable models—for example, Active Shape Model (ASM), Active Appearance Model (AAM), and map book-based models. The exploratory outcomes showed that their methodology accomplishes a 95% Dice, 93% social epistemic network signature (SENS), and 99% Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation (SPEC) in volume assessment but an Average symmetric surface distance (ASSD) of 1.17 mm and Root mean square symmetric surface distance (RMSD) of 2.01 mm in surface assessment [5].

This work shows the credibility of the program’s bone division and characterization of CT scans utilizing a convolutional neural network (CNN). The model accomplishes a high Diverse Counterfactual Explanations (Dice) coefficient and ends up being very robust to Gaussian clamor. In any case, a few constraints and enhancements that would unquestionably improve the execution are distinguished. An enhanced yet comparative model could be helpful in a few clinical and research applications for numerous therapeutic undertakings [6].

Researchers study the programmed characterization of complete tissues with 3D MRI. With an MRI flag structure, there is no need for unfolding. The additional data separated from the stage give better division than just utilizing greatness highlights. A request of greatness increment is acquired by diminishing the number of pixels that should be characterized [7].

Much more work has done in the field of deep and machine learning for the past decade, and in the future, there is a chance that deep learning, machine learning, big data, and information retrieval will remain the most tempting areas for researchers in the medical and engineering fields [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

3. Systematic Literature Review

A comparative “Systematic Literature Review” (SLR) has been chosen as the exploration technique. This paper utilizes SLR rules, which are a type of auxiliary investigation that utilizes a very much characterized technique. The SLR strategy is intended to be as reasonable as conceivable by being adaptable and repeatable. As per [16], the purpose of an SLR is to give a complete-as-possible overview of all studies that are identified within a certain branch of knowledge. In the meantime, customary surveys endeavor to condense the implications of various studies.

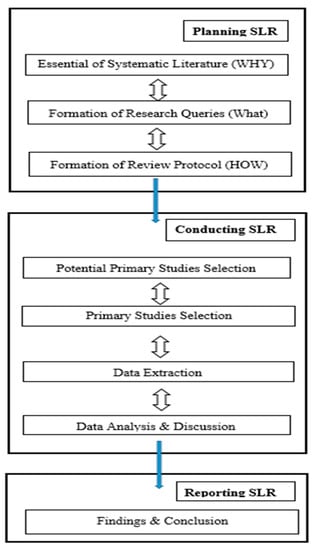

We performed an SLR utilizing the rules given in [17]. The SLR is an examination strategy for performing a survey efficiently capturing all characterized advances [17]. There are generally three stages of an SLR: planning the SLR, directing the SLR, and reporting the SLR (see Figure 2). Below, we discuss how we performed each part in these three stages.

Figure 2.

The systematic literature review process.

According to [16], an SLR procedure is secured by three back-to-back stages: planning the SLR, conducting the SLR, and reporting the SLR. In this section, we will concentrate on the arranging stage, which includes characterizing the study goals and how the audit was done.

3.1. Planning SLR

The following paragraph describes the complete plan for our systematic literature review.

3.1.1. Necessity of the SLR

The purpose of Evidence-Based Software Engineering (EBSE) is to aggregate the best results from research and examine these with regard to (reality) observations to assess these issues [17].

We utilized the following inquiry string to prove that there existed no comparative study in the literature.

((‘Knee bone’ OR ‘Deep Learning’ OR ‘Machine Learning’) AND (‘Knee bone’ OR MRI’) AND (‘Knee bone’ OR CT Scan’) AND (‘Knee bone’ OR X-ray’) AND (‘MRI’ OR ‘Deep Learning’) AND (‘X-ray’ OR ‘Deep Learning’) AND (‘CT Scan’ OR ‘Deep Learning’) AND (‘MRI’ OR ‘Machine Learning’) AND (‘X-ray’ OR ‘Machine Learning’) AND (‘CT Scan’ OR ‘Machine Learning’) AND (‘Systematic Review’ OR ‘Comparative Study Review’).

The recognized examinations were investigated based on their titles, concepts, and ends. The outcome demonstrated that there was no other SLR that had a similar degree and time frame of distribution.

3.1.2. Research Questions

We characterized our research questions (RQ) as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Research questions.

3.1.3. Review Protocol

This section introduces the survey convention that we characterized for directing the SLR. Below, we describe how we planned the SLR, choice of studies, information extraction, and information examination.

Search Process

It is very difficult to form an effective search string for primary studies. That is why we firstly focus on our main domain of knee bone images with deep learning and machine learning techniques and then focus on the image type, i.e., MRI, CT scan, or X-ray.

Then, we consider hyphens, antonyms, and synonyms for each word. Finally, we used Boolean operators (‘AND’ and ‘OR’) and wildcards (‘*’) to form an authentic string for the search process.

Table 2 shows the combinations of keywords, Boolean operators, and wildcards. The population column shows the keywords with the ‘AND’ operator, and the intervention column shows the combinations of more keywords with the ‘OR’ operator.

Table 2.

String search.

“*“ shows that the alphabets would be the same till asterisk *, but after that any alphabet can occur for searching query.

Study Exclusion Criteria

The accessibility of the full content of the essential investigation and English language were imperative for choice. Short papers were excluded.

Study Inclusion Criteria

The basic criteria for paper selection were related to the research questions mentioned in Table 3. We settled on 32 quality papers to study, which met our requirements. The selected criteria were set to study all aspects of our research. The included papers and criteria are mentioned in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Study inclusion criteria.

Quality Criteria for Primary Studies

When leading an SLR, it is essential to choose investigations of high quality in determining solid outcomes and ends *. This requires great SLR management, the adoption of the right catchphrases, and an all-around characterized consideration of avoidance criteria. We connected the accompanying criteria for further breaking down the nature of concerns regarding their legitimacy (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Quality criteria for primary study selection.

Data Extraction

After studying the primary studies, we extracted the data into tables. The outcomes were recorded in the structures for further examination. Below, we give the meanings of explicit data we obtained in connection to RQs (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Data extraction form.

4. SLR Conduct

After planning the study, we conducted our SLR. The following paragraphs describe the comprehensive details of our SLR methodology.

4.1. Design

In this section, we describe the design of the review by forming the strategies and queries to judge the quality of the measurements of this SLR.

4.1.1. Research Queries

Describing and depicting profound learning with machine learning methods is another issue, since we found that the most recent related work was in 2019. Consistently, a couple of examinations have driven machine learning methods with profound learning in the knee bone medicinal field. From now on, this paper is intended to describe the features that impact the sufficiency of Deep Learning methodologies with machine learning for knee bone information from MRI, CT scans, and X-rasy. The SLR Research Question (RQ) that we intend to answer in this paper is as follows:

“Which techniques of deep learning and machine learning are best for diagnosing knee bone diseases by using the imaging report data for MRI, CT scans, and X-rays?”.

4.1.2. Search Procedure

This SLR focuses on seeking logical databases as opposed to explicit books or specialized reports. A presumption was made that the majority of the exploration results in books and reports were likewise regularly depicted or referenced in logical papers. This study chose five databases to perform the SLR search process:

These databases were picked as they offer the most vital and most astounding full-content diaries and meeting procedures; 32 research papers were reviewed to cover the diagnosis of disease in knee bones by using deep learning and machine learning techniques.

The following keywords were used to find related studies to accomplish this SLR research:

“Deep learning in knee bone” OR “Machine learning in knee bone” OR “Knee bone diseases “OR “Knee bone X-ray” OR “Knee bone MRI” OR “Knee bone CT-scan”.

4.2. Study Selection

The determination of studies was performed through the following procedures [18]:

Inquiry across databases to identify significant studies, utilizing the search tags.

- Discarding studies based on the avoidance criteria.

- Discarding insignificantly concentrated studies based on the investigation of their titles and edited compositions.

- Assessing the choice to concentrate, depending on a full content read.

- Assessment by an outer specialist.

- Re-examining the outcomes in irregular studies.

- Acquiring essential examinations.

4.3. Quality Evaluation

As indicated by the rules of the SLR [18], three Quality Assurance (QA) queries must evaluate the nature of the examination of every proposition and provide a quantitative correlation between them. After selecting the primary studies according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we assessed their quality. The purpose of determining the quality of the papers was to determine how much our selected studies were relevant to our research questions and paper scope. We selected three quality questions and set their scores. We gave a score to each selected study, according to the relevancy of the paper to our scope. The scoring criteria are given below:

- Agree (A) = 1

- Some (S) = 0.5

- Disagree (D) = 0

The questions relating to the selected papers according to our requirements are given below:

- Do the selected papers refer to the required query?

- How are the function impediments archived?

- Were the detected research papers acceptable?

When the essential investigations of the SLR had been identified, we assessed them as indicated by the above queries. The score doled out to each examination for each inquiry is shown in Table 6 and Table 7 for deep learning and machine learning papers, respectively.

Table 6.

Quality assessment of selected research papers on deep learning.

Table 7.

Quality assessment of selected research papers on machine learning.

After obtaining the scores for these questions for all the selected studies, we determined the percentages by multiplying the averages of these question scores by 100. Let us take the example of SP1 for all three questions:

- Do the selected papers refer to the required query?

Our SP1 paper “Automatic knee osteoarthritis diagnosis from plain radiographs: a deep learning-based approach” is very relevant to our scope and required query. Because this paper is about the X-ray imaging of knee bone osteoarthritis with deep learning methodologies, we gave this paper a score of “1” because it fully relates to Question 1.

- How are the function impediments archived?

Although SP1 is quite good for our research, it is not supporting Question 2, so we gave it “0” for this question.

- Was the detected research paper acceptable?

Yes, this paper has authentic and quality research that is good enough for our research paper. Thus, we gave this paper a score of “1” for this question.

After getting the score, we determined the question score average for SP1 and then we multiplied it by 100 to get the percentage, i.e., 1 + 0 + 1 = 2 / 3 x 100 = 66.67%. In the end, we took the average of all the percentages according to % of an S1 + % of S2 +…………… % of S16 / 16 and then obtained the total percentage by multiplying the result by 100. Thus, we obtained the quality assessment percentages of the deep learning papers and machine learning papers.

Table 6 shows that our selected papers on deep learning techniques are highly related to our research requirements, as the relatedness scoring percentage is 70.83%.

Similarly, Table 7 indicates that our selected papers on machine learning techniques are highly related to our research requirements, as the relatedness scoring percentage is 76%.

Thus, it is obvious from the above two tables that our selected papers fulfill the quality requirements of the literature review.

4.4. Synthesis

Our research paper is related to knee bone reports, which we obtained by X-Ray, MRI, and CT scan imaging. We had to compare the data in these reports with the machine learning and deep learning methodologies. It was a challenge for us to find the studies that fitted our selection criteria because we required studies of deep learning methodologies with X-rays, MRI, and CT-scans and similarly required machine learning papers with these screening techniques. We found a lot of papers related to machine learning for X-rays, machine learning for knee bones, deep learning for CT scans, MRI images of knee bones, etc. However, it was very difficult to find papers that fulfilled our search queries, which are mentioned in Table 2.

Therefore, we decided to conduct our search on multiple levels, which are given below.

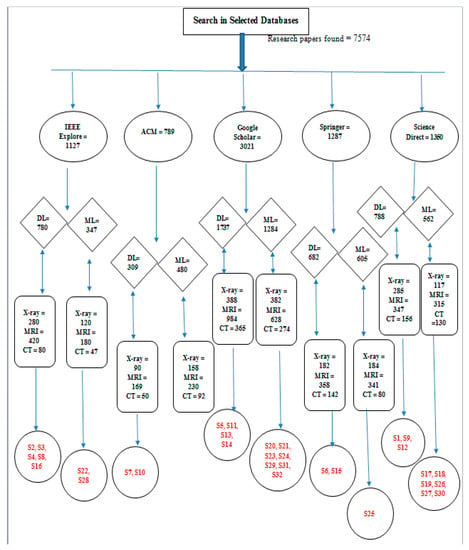

Level 1. Firstly, we selected databases to find selected research articles. There were almost 7574 related articles in different databases.

Level 2. At Level 2, we searched our papers in five databases including Springer, IEEE Xplore, Google Scholar, ACM, and Science Direct.

Level 3. At this level, we distinguished our papers related to deep learning and machine learning separately to perform a comparison between them.

Level 4. At Level 4, we took account of more papers related to MRI-, CT scan-, and X-ray-related deep learning and machine techniques.

Level 5. Finally, we found 32 papers, 16 on deep learning and 16 on machine learning. We distributed our papers in such a way that from these 30 papers on deep and machine learning, 10 papers were related to MRI, 12 consisted of X-rays, and the remaining 10 consisted of CT scans of knee bones.

Figure 3 demonstrates the hierarchy of our research methodology, which consists of five levels:

Figure 3.

Hierarchy of number of Studies for SLR.

4.5. Citation of Selected Papers

Table 8 shows the number of citations of selected research papers, which are taken from Google Scholar. Table 8 clearly shows that many papers are well-cited, which means that authentic papers were reviewed for this comparative literature review.

Table 8.

Citation of selected Deep Learning and Machine Learning Papers.

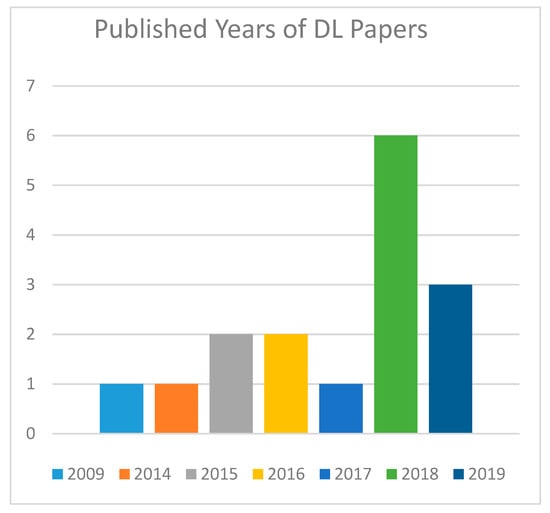

4.6. Years of Publication

Figure 4 shows the numbers of essential examinations by year of distribution. These 16 articles are distributed across the years 2009, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019. It demonstrates that the year 2018 has more chosen articles than the other years.

Figure 4.

Publication by years of Deep Learning papers.

According to Figure 4, the quantity of production was significantly in the year 2018 of studies utilizing Deep Learning approaches.

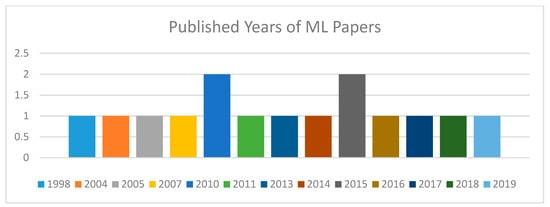

Figure 5 shows the published years of the selected machine learning papers. These papers are dispersed from the year 1998 to 2019. As papers related to our requirements of machine learning techniques for knee bone were rare in the previous 5 to 10 years, we decided to review more related papers; although they are so old, they were related to our requirements for this literature review. However, our major selected papers are from the last 10 years.

Figure 5.

Published years of selected ML papers.

4.7. Data Extraction

Table 9 and Table 10 provide the information extraction frame that is utilized for all the chosen essential investigations to do a top-to-bottom study. It describes the author’s name of the paper, published year, image type, model, data set, disease, and accuracy of the proposed techniques.

Table 9.

Extracted data for knee bone-related MRI, CT scans, and X-rays using deep learning techniques.

Table 10.

Extracted data for knee bone-related MRI, CT scans, and X-rays using machine learning techniques.

Table 11 and Table 12 describe the work of the researchers that they have performed by using different methodologies in their research papers, predictions of their future work, and the advantages of their research.

Table 11.

Extracted data from papers including contributions, predictions, and advantages of related deep learning techniques.

Table 12.

Extracted data from papers including the contributions, predictions and advantages of related Machine Learning Techniques.

Table 13 and Table 14 show the gaps in the review articles on deep learning and machine learning papers.

Table 13.

Deep learning papers.

Table 14.

Gaps in machine learning papers.

5. Discussion

Clinical imaging has prompted improvements in the determination and treatment of various ailments in children and adults. There are numerous sorts—or modalities—of clinical imaging systems, every one of which utilizes various advances and methods. Processed tomography (CT) and radiography (“regular X-beam” including mammography) both utilize ionizing radiation to produce pictures of the body. Ionizing radiation is a type of radiation that has enough power to possibly harm DNA and may raise an individual’s lifetime danger of malignant growths.

In CT, numerous X-ray images are recorded as the locator moves around the patient’s body. A computer recreates all the individual images into cross-sectional images or “cuts” of inner organs and tissues. A CT test includes a higher radiation portion than traditional radiography because the CT image is remade from numerous individual X-ray projections.

An MRI scanner can be utilized to take pictures of any piece of the body (e.g., the head, joints, midsection, legs, etc.), in any image bearing. X-rasy give better delicate tissue differentiation than CT and can better separate fat, water, muscle, and other delicate tissues than CT (CT is typically better for imaging bones). These pictures give data to doctors and can help in the diagnosis of a wide assortment of ailments and conditions.

A knee X-ray can help to elucidate the reasons for normal signs and side effects, for example, pain, sensitivity, swelling, or disfigurement of the knee. It can identify broken bones or a separated joint. After a damaged bone has been set, the picture can help to decide if the bone is in an inappropriate arrangement and whether it has recuperated appropriately.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee utilizes an amazing attractive field, radio waves, and a computer to create point-by-point images of the structures inside the knee joint. It is commonly used to help analyze or assess pain shortcomings, growths, or seeping in and around the joint.

A computed tomography (CT) filter is a kind of X-ray approach that shows cross-sectional pictures of a particular zone on one’s body. For instance, a CT output of one’s knee would assist specialists with diagnosing maladies or reviewing wounds on one’s knee. A CT scanner circles the body and sends images to a computer.

A lot work has been performed in the field of knee bones on the basis of medical imaging.

The exact division of the articular ligaments from magnetic resonance (MR) pictures of the knee is significant for clinical examinations and medication preliminary investigations into conditions such as osteoarthritis. As of now, divisions are acquired utilizing tedious manual or self-loader calculations that have high between- and intra-eyewitness change abilities. This paper presents a significant advance towards performed programmed and precise divisions of the ligaments, a specific way of dealing with consequently sectioning the bones and concentrating on the bone–ligament interfaces (BCI) in the knee. The division is performed utilizing three-dimensional dynamic shape models, which are introduced utilizing a relative enlistment to a map book. The BCI are then extricated utilizing picture data and earlier information about the probability of each point having a place with the interface. The exactness and robustness of the methodology were tentatively proved utilizing an MR database of fat stifled ruined inclination review pictures. The femur, tibia, and patella bone divisions had middle Dice closeness coefficients of 0.96, 0.96, and 0.89, respectively, and a normal point-to-surface error of 0.16 mm on the BCI. The removed BCI had a middle surface cover of 0.94 with the genuine interface, showing its usefulness for ligament division or quantitative investigation [47].

In an earlier investigation of marathon runners, we saw that MR sweeps of the knee often indicated the hyperplasia of red (i.e., hematopoietic) bone marrow. Since the recurrence of this finding in different populaces is obscure, the reason for this investigation was to decide the overall prevalence of hematopoietic bone marrow hyperplasia in MR assessments of the knees of solid volunteers (n = 74), patients with side effects of knee issues (n = 54), and asymptomatic long distance runners (n = 23). The frequency of hematopoietic bone marrow hyperplasia was 3% (2/74) for the healthy volunteers, 15% (8/54) for the patients, and 43% (10/23) for the long distance runners. The distinction in the predominance between every one of the three gatherings was statistically significant at p < 0.05 for each situation with hematopoietic bone marrow hyperplasia; the distal femur was the main site influenced, while the epiphysis and proximal tibia were uninvolved. This example of influenced bone marrow with hyperplasia of the hematopoietic marrow might be valuable for differential analysis. We hypothesize that the high predominance of hematopoietic bone marrow hyperplasia in long distance runners may be a reaction to “sports frailty”, which is generally found in exceptionally adapted, vigorously prepared competitors [48].

Based on the above discussion of the benefits of medical imaging, we decided to select these imaging techniques—X-rays, MRI, and CT scans—for our research. Our first question in Section 3.1.2 was taken to cover this imaging for knee bones. The work on these image types in this paper is mentioned in Section 5.1.

This section discusses this SLR. The dialog is about the examination question referenced above in Section 3.1.2. The answers to the question are mentioned in the given paragraph.

5.1. Type of Knee Bone Images Used in SLR

Our first question was related to medical images of knee bone.

“Which sort of knee bone images were used for medical image processing in this literature review?”.

We asked this question to understand the focus of knee bone images by using different methodologies. We select three types of medical images for this SLR, which are X-rays, CT scans, and MRI images of knee bone. We studied six papers on knee bone X-rays with deep learning techniques and six papers on those with machine learning techniques. Then, we read five papers on MRI images of knee bone with deep learning techniques and five papers on those with machine learning techniques. Similarly, we studied 10 papers on CT scan images of knee bone with deep and machine learning techniques. Thus, our research fulfills the requirements of our first question.

5.2. Techniques or Methods Used

Deep learning is, overall, a developing approach in information investigation and has been named one of the 10 greatest advances of 2013. Deep learning is an improvement of artificial neural networks, comprising more layers that grant more significant levels of deliberation and improved expectations from the information. Until this point in time, it has been rising as the main AI device in the general imaging and computer vision spaces. Medical image examination groups all over the world are rapidly entering the field and applying CNNs and other deep learning approaches to a wide assortment of utilizations. Promising outcomes are developing. Most translations of medical images are performed by doctors; however, the picture understanding of people is restricted because of its subjectivity, huge variation across mediators, and weakness. Numerous symptomatic actions require an original search procedure to recognize variations from the norm and to evaluate estimations and changes after some time. Electronic instruments—explicitly, image examination and AI—are the key empowering influences to improve analysis, by encouraging recognizable proof of discoveries that require treatment and help the master’s work process. Among these devices, deep learning is quickly becoming the cutting edge approach, prompting improved precision. It has additionally opened up new countries to information examination with paces of progress not previously experienced.

Even though the term machine learning is generally recent, the ideas of machine learning have been applied to clinical imaging for quite a long time, maybe most eminently in the areas of computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) and useful brain mapping. Our objectives are to familiarize examination with some cutting edge strategies that are presently staples in the machine learning field and to delineate how these methods can be utilized in different manners in clinical imaging.

We designated deep learning and machine learning techniques to study knee bone images. Deep learning and machine learning techniques are given below in Table 15, which were used for this SLR.

Table 15.

Deep and machine learning techniques.

5.3. Failure or Success Ratio

The artificial neural network (ANN), a machine learning procedure derived from the human neuronal neurotransmitter framework, was presented during the 1950s. In any case, the ANN has recently been restricted in its capacity to tackle genuine issues, because of the disappearing inclination and overfitting issues with preparing deep architecture, absence of registering power, and, fundamentally, the lack of adequate information to prepare the computer framework. Enthusiasm for this idea has recently remerged because of the accessibility of enormous amounts of information, upgraded registering power with current designs, preparing units, and novel calculations for preparing the profound neural system. Ongoing investigations into this innovation propose that it is conceivable for it to perform better than people in some visual and sound-related acknowledgment assignments, which may predict its applications in medicine and medical services, particularly in clinical imaging, working within a reasonable time-frame. This review article offers points of view on the history, improvement, and utilization of deep learning and innovation, especially concerning its applications in clinical imaging.

The purpose of this question was to determine the failure and success ratio of this SLR. We checked whether our research either completed successfully or failed. Thus, according to the results mentioned in Section 6, it is obvious that our SLR has been successful. It gave us a clear indication that there are a lot of techniques in a machine and deep learning that can provide the most accurate results for knee bone images that we get from X-ray, CT scan, or MRI reports.

5.4. Best Technique

For deep learning in radiology to succeed, it must be noted that well-explained huge informational indexes are required for deep systems that are mind-boggling; computer programming and equipment are developing continually, and inconspcious contrasts between malady states are harder to see than contrasts between regular items. Later on, machine learning in radiology will be required to be generously used in the clinic along with the imaging assessments being routinely performed in clinical work, providing the chance to improve choices and help in clinical picture understanding. The term of note is choice help, demonstrating that computers will expand human dynamics, making it progressively viable and proficient. The clinical effect of having PCs in routine clinical practice may permit radiologists to additionally incorporate their insights with their clinical associates in other clinical claims to fame and consider accurate medication.

We compared our study with deep learning and machine learning techniques; all techniques provide good accuracy for knee bone images. The accuracy of X-ray, CT scan, and MRI images with deep and machine learning techniques are mentioned in Table 16, below.

Table 16.

Accuracy.

The results show that deep learning techniques and methodologies provide more accuracy for X-ray, MRI, and CT scan images of knee bones to diagnose diseases. Meanwhile, machine learning provides good accuracy but less than deep learning.

6. Conclusions and Forthcoming Work

The objective of this research was to conduct a comparative “systematic literature review” on MRI, CT scan, and X-ray images of knee bone by using deep learning techniques. Thirty-two papers associated with deep learning and machine learning approaches were reviewed in this research, which provide the accuracy mentioned in Table 17 and Table 18, respectively.

Table 17.

Accuracy of deep learning papers.

Table 18.

Accuracy of machine learning papers.

Let us discuss the outcomes of each research paper used for this research to finalize our results. The following points describe the outcomes of each paper:

S1: This paper is about deep learning techniques with X-ray images of the knee bone disease osteoarthritis. The authors showed a novel methodology for naturally diagnosing and reviewing knee OA from X-rays. It can help patients experiencing knee pain to obtain a quicker finding. Their technique accomplishes the best multi-class grouping results, despite having an alternate testing set: a normal multi-class precision of 66.71%, radiographical OA AUC of 0.93, quadratic weighted Kappa of 0.83, and MSE of 0.48. It may be possible to contrast this with normal human understandings. A total of 3000 subjects from the Osteoarthritis Initiative dataset was used in their research.

S2: This paper covers the knee bone tumor X-rays with deep learning techniques. The ImageNet dataset was used for this paper. In this paper, the researchers present a successful end-to-end deep learning model for knee bone tumor arrangement. In future work, the researchers will grow the present model to confine the tumor’s position, which may altogether support clinical treatment. The proposed new model uses semi-supervised ensemble Wnet (SSEW) in their research. They used three models—InceptionV3, ResNet50, and MobileNet. The accuracy results for the proposed model (SSEW) are 97.64 for Two-Class, 79.23 for “79.23”, and 80.31 for Five-Class, respectively.

S3: This paper is about studying the osteoarthritis of knee bones via X-rays with deep learning techniques. The Kellgren–Lawrence classification model is used for research. The accuracy of this model is, for moderate OA, 91.5%; for minimal OA, 80.4%; and for doubtful OA, 57%.

S4: This paper is related to X-ray images of knee bone osteoarthritis with deep learning techniques. This paper researched a few new techniques for the programmed measurement of knee OA seriousness, utilizing the CNN model. In the future, there is a plan to increase the accuracy of the CNN model of the knee joint by applying more techniques. The accuracy of this technique was 94.2%.

S5: The researchers worked on knee osteoarthritis in X-ray images of knee bone. The active contour segmentation technique was used for this research. A total of 200 X-ray images were used as the dataset. The accuracy of this technique was 87.92%.

S6: In this paper, X-ray images of osteoarthritis patients were used with deep learning techniques. Two algorithms were used, which are the K-nearest Neighbor Algorithm (KNN) and Supports Vector Machine (SVM). The accuracy results for these techniques were, for normal images, KNN = 100% and SVM = 79% and for abnormal images, KNN = 100% and SVM = 100%.

S7: This research paper is about MRI images of knee bones for the detection of knee bone diseases from MRI. Online MRI datasets were used for this technique. Scale Space Local Binary Pattern (LBP) feature extraction was used for this research. The accuracy attained in this research was 96.1%.

S8: In this paper, the convolutional neural network (CNN) was used for MRI images with deep learning techniques. The MICCAI dataset was used to accomplish this research. In this paper, the researchers built up a knee ligament division calculation from a high goal MR volume utilizing a novel completely 3D Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). The accuracy of this technique was 87.7%. The accuracy of the proposed system will be improved in the future.

S9: In this paper, 3D MRI datasets SK10, Dataset OAI Imorphics, and dataset OAI ZIP were used for MRI images of knee bones with deep learning techniques. The models used for this research were the 3D CNN and SSM. The accuracies of these models were for the 3D MRI datasets SK110, 75.73%; for the dataset OAI Imporphics, 90.4%; and for the dataset OAI ZIb, 98.5%.

S10: In this research 3D MRI dataset images were used for knee bone MRI reports. The researchers of this research created and assessed a programmed 3D deformable methodology for knee MRI having force inhomogeneity. The exploratory outcomes showed that their methodology accomplished 95% Dice, 93% SENS, and 99% SPEC in the volume assessment but an ASSD of 1.17 mm and RMSD of 2.01mm in the surface assessment.

S11: In this research, the Convolutional Neutral Network (CNN) model was used for 175 patient MRI datasets for knee bones. The accuracy attained in this research was 91%.

S12: This research is on CT scan image reports on knee bone. It is a systematic literature review. In this research, the datasets of CT scan, and some of MRIs, are used. Their results show that 95% accuracy can be achieved.

S13: In this study, 2D CT scan images were used for knee joint reconstruction. The CT scan data of multiple patients were used for this research. The researchers of this research used a convolutional neural network for all knee bone diseases. A dataset of 21 abdominal CT scans images was used to accomplish this research. The accuracy obtained from the research was 93%.

S14: The CT scan data of multiple patients was used by using different deep learning models. The technique models used to accomplish this research were Finite element (FE), Sobel Operator, Laplacian of Gaussian operator, and Canny edge detection. The researchers claim that 83% accuracy can be achieved for CT scan images of the knee by using these techniques.

S15: The researchers of this research used the CT scan images of 59 patients by using the CNN technique for sclerotic metastasis of knee bone CT scans. The researchers created a two-layered coarse-to-fine course structure to initially working with an exceptionally delicate hopeful age framework with the greatest affectability of ∼92% but with a high FP level (∼50 per understanding). The average accuracy gain with this technique was 70% to 80%.

S16: In this study, the researchers used the 3D image datasets of knee bone CT scans. The convolutional neural network was used for their research. In this paper, the researchers proposed a novel structure to determine seven anatomical milestones of the distal femur bone. They attained 80% accuracy in this research.

S17: In this study, the researchers worked on MRI images of Gaucher’s patients’ reports using machine learning techniques. The technique that was used to accomplish this research is the General Linear Model (GLM). This study’s motivation was to build up a strategy to measure the seriousness of bone ailments in type 1 GD patients and to differentiate between various GD genotypes and between GD patients and healthy people. The accuracy obtained with this technique for MRI images of knee bones was 70%.

S18: In this study, the researchers performed work on MRI images of osteoarthritis and osteochondral patients. The machine learning technique used for this study was Pattern Recognition and Multivariable regression (WND-CHARM). WNDCHRM might be an effective technique for the grouping of ligament MRIs. A dataset of 35 MRI images was used to accomplish this study. The accuracy obtained by this technique for MRI images of knee bones was 86%.

S19: In this study, the researchers studied the programmed characterization of finished tissues in 3D MRI. This research used the complex magnetic resonance signal, which provides segmented information. This research is good for the feature extraction of knee bone for all diseases. In this study, the Support Vector Machine (SVM) was used by using a dataset of 18 MRI images. A 91% accuracy was obtained by using this technique.

S20: In this paper, 36 BNC samples and 40 control samples of osteoarthritis patients’ MRI images were used. A multivariable Support Vector machine was used for this study. The researchers examined whether multivariate help vector machine examination would allow enhanced tissue portrayal. SVM examination performed utilizing certain parameter combinations displayed especially ideal grouping properties. The outcomes show the capacity of multivariate examination to incredibly increase the MRI appraisal of ligament network status in essential scientific studies. The research proves that 97% accuracy can be achieved for MRI images of knee bones using the SVM technique.

S21: In this research, the natural language processing framework was prepared, in an attempt to master ordered knee MRI reports from two noteworthy human services associations. The researchers assessed the execution of the framework both inside and across associations. The Support Vector Machine was used to accomplish this study. The results of this research prove that 95% accuracy can be achieved by using this technique for knee MRI reports.

S22: This paper tried to distinguish the edges of restorative pictures, especially knee osteoarthritis pictures in various basic states utilizing the Sobel administrator and proposed developed Sobel calculation. The proposed algorithm is very good for blurred and distorted images. The researchers used the dataset of X-ray images of osteoarthritis patients by using Sobel Edge Detector Operator. Their research concludes that 50% accuracy can be obtained by using this machine learning technique.

S23: In this paper, the researchers proposed a model-guided milestone limitation strategy for programmed ISR estimation. At first, the proposed technique required building a patella to demonstrate a factual patella shape and power data from preparatory information. They used 21 X-ray images for training patellae and 48 X-ray images as the validation data set. A component point extraction calculation was intended to determined the underlying model position naturally. The precision of the proposed technique was proved by both quantitative and subjective tests. Their research’s outcome is that 80% accuracy can be achieved by using this technique.

S24: This paper exhibited a researcher’s exploration of the recognition of bone breaks in X-ray images. A dataset of 432 images of the femur was used with the Support Vector Machine and Bayesian Classifier techniques. Their research concludes that 97.2% accuracy can be achieved through these machine learning techniques.

S25: In this study, the researchers used a dataset of 75,000 patients. They used the X-ray images of osteoarthritis patients by using the Bootstrap Aggregation technique. They achieved 97% accuracy for X-ray images of knee bone osteoarthritis.

S27: This investigation presented a robotized computer-aided diagnostic approach for the identification of OA, which utilizes a mix of standardizations given presciently, displaying MLR utilization and highlight extraction utilizing ICA. The classification rates of the proposed CAD are higher than those obtained in previous studies. They used 1024 X-ray images of osteoarthritis patients and used the Multivariate Linear Regression (MLR) technique. They achieved 82.98% accuracy.

S28: This research study performed a morphometrical comparison between CT scan databases of miniaturized objects by using the two-division procedure. The researchers used the Micro CT-Scan trabecular datasets by using Chan–Vese and Fixed Threshold techniques. They obtained 60% to 70% accuracy with these techniques.

S29: This study is related to CT scan images of osteoporosis, which is a knee bone disease. They used the Multidetector Computed Tomography (MDCT) dataset of CT scan images of knee bones. They obtained 98% accuracy.

S30: The goal of this study was to utilize fluoroscopy to precisely determine three-dimensional (3D) structure. They used 10 knees-experienced patterns of 3D CT scan images by using the helical axis of the model. They obtained 90% accuracy.

S31: The primary objective of this study was to assemble a limited component, demonstrate phenomena for trabecular bone from small scale figured tomography (miniaturized scale CT) pictures, and concentrate on the flexible properties of bone. They used seven samples of pig femur bone CT scan images by using the finite element model. They obtained 65% accuracy by using this machine learning technique.

S32: In this examination, a few morphological parameters were estimated at the same time for each example as opposed to simply concentrating on a couple of parameters. The researchers of this study used the Finite Element Model (FME) on the CT scan images of porcine trabecular bones. They obtained 70% accuracy with the FME for CT scan images.

We determined our results by calculating the average of each image type, i.e., to determine the accuracy of X-ray images for deep learning, we summed up the accuracy of each X-ray paper and divided the sum by the total number of X-ray papers. In our study, there are six X-ray papers for deep learning, so we calculated it by dividing the accuracy sum by six. Similarly, we calculated the total accuracy for the MRI and CT scan image types.

After obtaining the results for all the papers, we determined that deep learning methodologies provide more accuracy for MRI, CT scan, and X-ray images than machine learning techniques. While machine learning techniques provide less accuracy, we can conclude by saying that deep learning techniques are best for X-ray, MRI, and CT scan images for knee bone diseases. Undoubtedly, techniques of deep and machine learning are both helpful in medical image processing, but it is the situation that decides which is the best technique to obtain the best accuracy.

As it is a comparative systematic literature review, we conclude by finding and calculating each study’s accuracy.

The explosion of computerized medical service information has prompted a flood of information-driven clinical exploration dependent on machine learning. As of late, as an influential strategy for big data, deep learning and information retrieval have increased a focal situation in machine learning circles for incredible points of interest in inclusion portrayal and example acknowledgment. Many articles present a far-reaching outline of studies that utilize big data and information retrieval strategies to manage clinical information. Initially, because of the investigation of the attributes of clinical information, different kinds of clinical information (e.g., clinical pictures, clinical notes, lab results, indispensable signs, and segment informatics) are discussed, and the subtleties of some open clinical datasets are mentioned. Furthermore, a short review of normal deep learning models and their qualities is performed. At that point, considering the wide scope of clinical exploration and the considerable variety of information types, a few big data applications for clinical information are shown: assisted conclusions, anticipation, early admonition, and different errands. Even though there are difficulties in applying deep learning procedures to clinical information, it is as of yet advantageous to anticipate a promising future for deep learning applications in clinical big data toward precision medicine [49].

Our research is still in progress; as many studies are performed in the medical field by using big data and information retrieval techniques, we have a plan to review big data and information retrieval techniques for this literature review to make this study more qualified.

Table A1 contains the citation’s references of selected studies. By using this table, reader can find the reference of selected studies from bibliography.

Funding

This research work is supported by Data and Artificial Intelligence Scientific Chair at Umm AlQura University, Makkah City, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Primary Studies of Comparative Systematic Literature Review:

Table A1.

Reviewed papers and references.

Table A1.

Reviewed papers and references.

| # | Citation | # | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | [4] | S17 | [32] |

| S2 | [19] | S18 | [33] |

| S3 | [20] | S19 | [7] |

| S4 | [21] | S20 | [34] |

| S5 | [22] | S21 | [35] |

| S6 | [23] | S22 | [36] |

| S7 | [24] | S23 | [37] |

| S8 | [25] | S24 | [38] |

| S9 | [26] | S25 | [39] |

| S10 | [5] | S26 | [40] |

| S11 | [27] | S27 | [41] |

| S12 | [28] | S28 | [42] |

| S13 | [6] | S29 | [43] |

| S14 | [29] | S30 | [44] |

| S15 | [30] | S31 | [45] |

| S16 | [31] | S32 | [46] |

References

- Ryzhkov, M.D. Knee Cartilage Segmentation Algorithms: A Critical Literature Review. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Senaras, C.; Gurcan, M.N. Deep learning for medical image analysis. J. Pathol. Inform. 2018, 9, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, B.J.; Korfiatis, P.; Akkus, Z.; Kline, T.L. Machine Learning for Medical Imaging. Radiographics 2017, 37, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiulpin, A.; Thevenot, J.; Rahtu, E.; Lehenkari, P.; Saarakkala, S. Automatic Knee Osteoarthritis Diagnosis from Plain Radiographs: A Deep Learning-Based Approach. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Lee, J.; Yoon, J.S.; Lee, K.J.; Won, K. Development of automated 3D knee bone segmentation with inhomogeneity correction for deformable approach in magnetic resonance imaging. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Research in Adaptive and Convergent Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 9–12 October 2018; pp. 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa, F. A Deep Learning Approach to Bone Segmentation in CT Scans. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeat, P.; Fripp, J.; Stanwell, P.; Ramadan, S.; Ourselin, S. MR image segmentation of the knee bone using phase information. Med. Image Anal. 2007, 11, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, I.; Fatima, K.; Dastagir, A.; Mahmood, S.; Hussain, M. Autism Identification and Learning Through Motor Gesture Patterns. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Innovative Computing (ICIC), Lahore, Pakistan, 1–2 November 2019; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8966740/ (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Nadeem, M.W.; Hussain, M.; Khan, M.A.; Awan, S.M. Analysis of Smart Citizens: A Fuzzy Based Approach. Commun. Comput. Eng. 2019, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainab, M.; Usmani, A.R.; Mehrban, S.; Hussain, M. FPGA Based Implementations of RNN and CNN: A Brief Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Innovative Computing (ICIC), Lahore, Pakistan, 1–2 November 2019; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8966676/ (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Nadeem, M.W.; Al Ghamdi, M.A.; Hussain, M.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, K.M.; AlMotiri, S.H.; Butt, S.A. Brain Tumor Analysis Empowered with Deep Learning: A Review, Taxonomy, and Future Challenges. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.G.; Zahid, A.H.; Hussain, M.; Farooq, M.; Riaz, U.; Alam, T.M. A journey of WEB and Blockchain towards the Industry 4.0: An Overview. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Innovative Computing (ICIC), Lahore, Pakistan, 1–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor, A.; Hussain, M.; Mehrban, S. Performance Analysis and Route Optimization: Redistribution between EIGRP, OSPF & BGP Routing Protocols. Comput. Stand. Inter. 2020, 68, 103391. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0920548919300996 (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Hassan, M.; Hussain, M.; Ayubi, S.-U.-D.; Irfan, M. A Policy Recommendations Framework To Resolve Global Software Development Issues. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Innovative Computing (ICIC), Lahore, Pakistan, 1–2 November 2019; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8966719/ (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Hussain, M.; Al-Haiqi, A.; Zaidan, A.; Zaidan, B.; Kiah, M.; Iqbal, S.; Abdulnabi, M.; Iqbal, S. A security framework for mHealth apps on Android platform. Comput. Secur. 2018, 75, 191–217. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167404818300798 (accessed on 22 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Hordri, N.F.; Samar, A.; Yuhaniz, S.S.; Shamsuddin, S.M. A systematic literature review on features of deep learning in big data analytics. Int. J. Adv. Soft Comput. Appl. 2017, 9. Available online: http://home.ijasca.com/data/documents/Vol_9_1_ID-19_Pg32-49.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Tahir, T.; Rasool, G.; Gencel, C. A systematic literature review on software measurement programs. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2016, 73, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhani, B.D.; Mahrin, M.N.; Nikpay, F.; Ahmad, R.B.; Nikfard, P. A systematic literature review on Enterprise Architecture Implementation Methodologies. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2015, 62, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, N.-H.; Yang, H.-J.; Kim, S.H.; Taek Jeong, S.; Joo, S.-D. Ene-to-end Knee Bone Tumor Classification from Radiographs Based on Semi-Supervised Ensemble Wnet; Korean Multimedia Society, Honam University Gwangsan: Gwangsan, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shamir, L.; Ling, S.M.; Scott, W.W.; Bos, A.; Orlov, N.; Macura, T.J.; Eckley, D.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Goldberg, I.G. Knee x-ray image analysis method for automated detection of osteoarthritis. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2009, 56, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antony, J.; McGuinness, K.; O’Connor, N.E.; Moran, K. Quantifying radiographic knee osteoarthritis severity using deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 23rd International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Cancun, Mexico, 4–8 December 2016; pp. 1195–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Gornale, S.S.; Patravali, P.U.; Manza, R.R. Detection of osteoarthritis using knee X-ray image analyses: A machine vision based approach. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2016, 145, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hegadi, R.S.; Chavan, U.P.; Navale, D.I. Identification of Knee Osteoarthritis Using Texture Analysis. In Data Analytics and Learning; Springer: Solapur, India, 2019; pp. 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Mun, J.; Jang, Y.; Son, S.-H.; Yoon, H.J.; Kim, J. A SSLBP-based feature extraction framework to detect bones from knee MRI scans. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Research in Adaptive and Convergent Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 9–12 October 2018; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, A.; Vishwanathan, S.; Ajani, B.; Krishnan, K.; Agarwal, H. Automatic knee cartilage segmentation using fully volumetric convolutional neural networks for evaluation of osteoarthritis. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018), Washington, DC, USA, 4–7 April 2018; pp. 851–854. [Google Scholar]

- Ambellan, F.; Tack, A.; Ehlke, M.; Zachow, S. Automated segmentation of knee bone and cartilage combining statistical shape knowledge and convolutional neural networks: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Med. Image Anal. 2019, 52, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhou, Z.; Samsonov, A.; Blankenbaker, D.; Larison, W.; Kanarek, A.; Lian, K.; Kambhampati, S.; Kijowski, R. Deep Learning Approach for Evaluating Knee MR Images: Achieving High Diagnostic Performance for Cartilage Lesion Detection. Radiology 2018, 289, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.-D.; Xiang, B.-Y.; Schotanus, M.G.; Liu, Z.-H.; Chen, Y.; Huang, W. CT-versus MRI-based patient-specific instrumentation for total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon 2017, 15, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.-W.; Seo, Y.-J.; Yoo, Y.-S.; Kim, Y.S. Computed Tomographic Image Analysis Based on FEM Performance Comparison of Segmentation on Knee Joint Reconstruction. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, H.R.; Yao, J.; Lu, L.; Stieger, J.; Burns, J.E.; Summers, R.M. Detection of Sclerotic Spine Metastases via Random Aggregation of Deep Convolutional Neural Network Classifications. In Recent Advances in Computational Methods and Clinical Applications for Spine Imaging; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 20, pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, S.; Yan, Z.; Tan, C.; Li, K.; Metaxas, D. Automated anatomical landmark detection ondistal femur surface using convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 12th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), New York, NY, USA, 16–19 April 2015; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.B.; Robertson, D.D.; Laney, D.A.; Gambello, M.J.; Terk, M. Machine learning based analytics of micro-MRI trabecular bone microarchitecture and texture in type 1 Gaucher disease. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 1961–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashinsky, B.G.; Coletta, C.E.; Bouhrara, M.; Lukas, V.A.; Boyle, J.; Reiter, D.A.; Neu, C.P.; Goldberg, I.G.; Spencer, R.G.S. Machine learning classification of OARSI-scored human articular cartilage using magnetic resonance imaging. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2015, 23, 1704–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-C.; Irrechukwu, O.; Roque, R.; Hancock, B.; Fishbein, K.W.; Spencer, R.G. Multivariate analysis of cartilage degradation using the support vector machine algorithm. Magn. Reson. Med. 2011, 67, 1815–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, S.; Langlotz, C.; Amrhein, T.J.; Befera, N.; Lungren, M.P. Performance of a Machine Learning Classifier of Knee MRI Reports in Two Large Academic Radiology Practices: A Tool to Estimate Diagnostic Yield. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2017, 208, 750–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahurul, S.; Zahidul, S.; Jidin, R. An Adept Edge Detection Algorithm for Human Knee Osteoarthritis Images. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Signal Acquisition and Processing, Bangalore, India, 9–10 February 2010; pp. 375–379. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.-C.; Lin, C.-J.; Wu, C.-H.; Wang, C.-K.; Sun, Y.-N. Automatic Insall–Salvati ratio measurement on lateral knee x-ray images using model-guided landmark localization. Phys. Med. Boil. 2010, 55, 6785–6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.E.; Xing, Y.; Chen, Y.; Leow, W.K.; Howe, T.S.; Png, M.A. Detection of Femur and Radius Fractures in X-ray Images. Available online: https://www.comp.nus.edu.sg/~leowwk/papers/medsip2004.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Kruse, C.; Eiken, P.; Vestergaard, P. Machine Learning Principles Can Improve Hip Fracture Prediction. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2017, 100, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoff, W.A.; Komistek, R.D.; Dennis, D.A.; Gabriel, S.M.; Walker, S.A. Three-dimensional determination of femoral-tibial contact positions under in vivo conditions using fluoroscopy. Clin. Biomech. 1998, 13, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahim, A.; Jennane, R.; Riad, R.; Janvier, T.; Khedher, L.; Toumi, H.; Lespessailles, E. A decision support tool for early detection of knee OsteoArthritis using X-ray imaging and machine learning: Data from the OsteoArthritis Initiative. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2019, 73, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demenegas, F.; Tassani, S.; Matsopoulos, G.K. Active segmentation of micro-CT trabecular bone images. In Proceedings of the 2011 10th International Workshop on Biomedical Engineering, Kos Island, Greece, 5–7 October 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. Finite element modeling of trabecular bone from multi-row detector CT imaging. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, D.A.; Mahfouz, M.; Komistek, R.D.; Hoff, W. In vivo determination of normal and anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee kinematics. J. Biomech. 2005, 38, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, O. Finite Element Analysis of Porcine Trabecular Bone Based on Micro-CT Images. 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2142/78802 (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Lee, W. Structure-Property Relations of Porcine Trabecular Bone and Micro-CT Imaging of Various Materials. 2013. Available online: https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/handle/2142/45644 (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Fripp, J.; Crozier, S.; Warfield, S.K.; Ourselin, S. Automatic segmentation of the bone and extraction of the bone–cartilage interface from magnetic resonance images of the knee. Phys. Med. Boil. 2007, 52, 1617–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shellock, F.G.; Morris, E.; Deutsch, A.L.; Mink, J.H.; Kerr, R.; Boden, S.D. Hematopoietic Bone Marrow Hyperplasia: High Prevalence on MR Images of the Knee in Asymptomatic Marathon Runners. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1992, 158, 335–338. Available online: www.ajronline.org (accessed on 2 July 2020). [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. Clinical big data and deep learning: Applications, challenges, and future outlooks. Big Data Min. Anal. 2019, 2, 288–305. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8787233/ (accessed on 23 June 2020). [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).