Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is becoming more and more integrated into manufacturing processes, revolutionizing conventional production, like CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machining. This study analyzes how large language models (LLMs), exemplified by ChatGPT, behave when tasked with G-code optimization for improving surface quality and productivity of automotive metal parts, with emphasis on systematically documenting failure modes and limitations that emerge when general-purpose AI encounters specialized manufacturing domains. Even if software programming remains essential for highly regulated sectors, free AI tools will be increasingly used due to advantages like cost-effectiveness, adaptability, and continuous innovation. The condition is that there is sufficient technical expertise available in-house. The experiment carried out involved milling three identical parts using a Haas VF-3 SS CNC machine. The G-code was generated by SolidCam and was optimized using ChatGPT considering user-specified criteria. The aim was to improve the quality of the part’s surface, as well as increase productivity. The measurements were performed using an ISR C-300 Portable Surface Roughness Tester and Axiom Too 3D measuring equipment. The experiment revealed that while AI-generated code achieved a 37% reduction in cycle time (from 2.39 to 1.45 min) and significantly improved surface roughness (Ra—arithmetic mean deviation of the evaluated profile—decreased from 0.68 µm to 0.11 µm—an 84% improvement), it critically eliminated the pocket-milling operation, resulting in a non-conforming part. The AI optimization also removed essential safety features including tool length compensation (G43/H codes) and return-to-safe-position commands (G28), which required manual intervention to prevent tool breakage and part damage. Critical analysis revealed that ChatGPT failures stemmed from three factors: (1) token-minimization bias in LLM training leading to removal of the longest code block (31% of total code), (2) lack of semantic understanding of machining geometry, and (3) absence of manufacturing safety constraints in the AI model. This study demonstrates that current free AI tools like ChatGPT can identify optimization opportunities but lack the contextual understanding and manufacturing safety protocols necessary for autonomous CNC programming in production environments, highlighting both the potential, but also the limitation, of free AI software for CNC programming.

1. Introduction

Industry 5.0 represents the next evolution in industrial practices, focusing heavily on human-centric approaches, sustainability, digital and green transitions, and smart technologies [1]. In the context of CNC machining, Industry 5.0 focuses on enhancing the partnership between skilled human workers and automated CNC machines, allowing customization, flexibility, and integration with advanced technology [2].

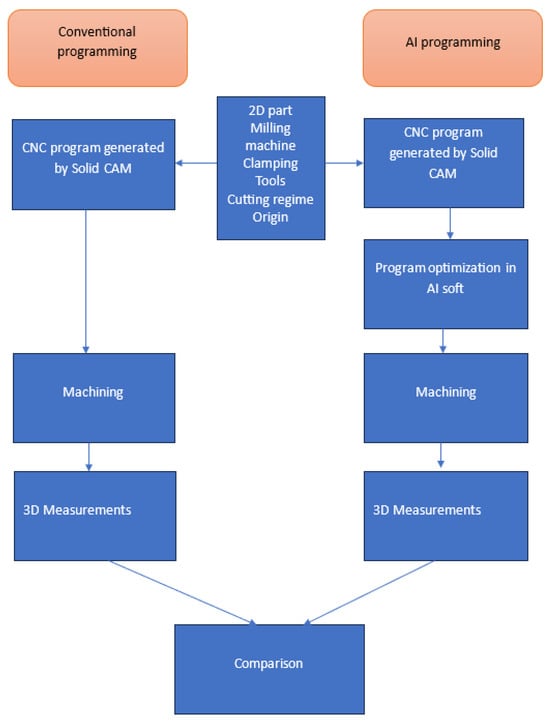

This paper analyzes how artificial intelligence serves the purpose of increasing flexibility within companies by integrating it into the programming process. The main objective of the paper is to provide empirical documentation of both the capabilities and critical failure modes when using artificial intelligence in CNC programming. More specifically, this study systematically investigates where general-purpose AI tools like ChatGPT 4.0 succeed and fail when applied to specialized manufacturing tasks. Thus, two programming methods were used to mill the same part. In the first phase, using a CAM (Computer-Aided Manufacturing) program, the G-code was generated. In the second phase, the same program was introduced into artificial intelligence software, with the instruction to optimize the program and improve the quality of the surface obtained.

By focusing on surface quality improvements, businesses can innovate their operations to support the dual goals of digitalization and sustainability, thus aligning with the principles of Industry 5.0. AI algorithms can analyze vast amounts of data quickly, enabling more efficient machining processes. This can lead to shorter cycle times, reduced waste, and improved resource allocation compared to machining using CAM software. Another advantage is that AI algorithms can increase production demand without significant investment in new technologies, making it a sustainable choice for future growth.

In the context of Industry 5.0, which focuses on the collaboration between humans and machines, CNC machining can significantly enhance surface quality for several reasons:

Human–Machine Collaboration: Industry 5.0 emphasizes the partnership between advanced technologies and skilled human workers. Operators can provide oversight and quality checks to ensure superior surface finishes, while CNC machines handle repetitive tasks with precision.

Smart Technologies: Incorporating IoT devices and AI algorithms into CNC operations can lead to real-time monitoring and adjustments. Predictive analytics can anticipate potential issues, leading to improved surface quality and reduced errors.

Advanced Materials and Coatings: Industry 5.0 promotes the use of innovative materials and surface treatment technologies. CNC machining can be combined with these features to achieve better surface finishes, such as enhanced durability and corrosion resistance.

Customization and Flexibility: CNC machines can quickly adapt to produce customized parts in smaller production runs. This flexibility allows for more intricate designs that can improve the overall esthetics and functionality of the components.

Sustainability Practices: Industry 5.0 encourages sustainable manufacturing. CNC machining can minimize waste and energy consumption, contributing to an eco-friendlier approach while maintaining high surface quality. The transition from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0 has brought a renewed focus on human-centric and sustainable manufacturing. Mohsen Soori et al. [3] discussed how AI-powered technologies enhance collaboration between humans and machines. Their research emphasizes the importance of maintaining ergonomic work environments while leveraging AI for automation. For example, Industry 5.0 frameworks propose the use of robots for repetitive tasks, allowing human operators to focus on creative and strategic roles. These developments foster a balanced approach to automation, ensuring both productivity and worker well-being.

In this way, this holistic approach can lead to enhanced competitiveness, reduced environmental impacts, and improve customer satisfaction.

While AI tools, including ChatGPT, are increasingly explored across manufacturing domains, this study provides novel contributions in the following ways:

Systematic Empirical Validation: Unlike anecdotal applications or theoretical analyses, this research presents rigorous experimental methodology with quantitative measurements of surface roughness (Ra, Rz), dimensional tolerances, form deviations, and cycle times across multiple specimens, providing reproducible data on AI optimization performance.

Critical Limitations Documentation: This is among the first studies to systematically document the failure modes of free generative AI in CNC programming—specifically, the removal of critical operations (pocket milling) and safety features (G43, G28 codes)— with photographic evidence, detailed code comparison table (Table 5), and quantitative analysis showing that the eliminated pocket operation constituted 31% of the original code length.

Manufacturing Safety Analysis: We explicitly analyze the safety implications of AI-generated code omissions, which is an area that has received limited attention in existing literature despite being critical for production implementation.

Industry 5.0 Context: This work positions AI-assisted CNC programming within the Industry 5.0 framework of human–machine collaboration, demonstrating that current free AI tools function as assistive rather than autonomous systems.

Practical Implementation Guidance: By comparing 180+ lines of G-code across six machining operations with detailed commentary, we provide practitioners with specific insights into where AI excels (cycle time, surface optimization) and fails (geometric completeness, safety protocols).

The novelty lies not in using ChatGPT per se, but in providing the manufacturing community with rigorous, transparently documented evidence of both capabilities and critical limitations that must be understood before production implementation.

This study is not an endorsement of ChatGPT as a production-ready CNC programming tool. Rather, it is an empirical investigation into the failure modes of general-purpose AI when applied to specialized manufacturing tasks. The utilization of accessible AI tools has led manufacturing practitioners to experiment with LLMs for tasks including code generation, despite these tools lacking manufacturing domain knowledge. Understanding where and how these tools fail is critical research that prevents potentially dangerous implementations in production environments.

2. Literature Review

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a multidisciplinary field that integrates knowledge from various scientific disciplines, including computer science, deep learning, machine learning (ML), evolutionary biology (through evolutionary algorithms), robotics, and planning. The appearance of artificial intelligence (AI) has significantly transformed various sectors, including manufacturing. Various AI techniques are being utilized to optimize CNC machining processes. These include ML, neural networks, and genetic algorithms, each offering distinct advantages in analyzing and improving the complex CNC programming tasks [4,5,6,7]. Machine learning algorithms are utilized to predict the outcomes of specific machining conditions. A study by Aman Kukreja et al. [8] uses ML models trained to determine the best toolpath planning strategy for CNC machining (finishing) without using CAM software. The tool path is generated directly from the CAD (Computer-Aided Design) model using Convolutional Neural Network. The surface finish, toolpath length, and smoothness are permanently evaluated. Machine learning technologies are being utilized to predict tool wear and energy consumption. Studies show that predictive data can help mitigate tool failures and extend tool life, which results in reduced downtime and lower machining costs [9]. This not only enhances productivity but also ensures consistent surface quality. Machine learning algorithms allow supervision controllers for real-time assessment of surface quality during machining [10]. Through advanced algorithms, these systems can predict and adjust the machining parameters in real time to ensure that the desired surface finish is achieved without incurring additional costs [11]. Recent studies highlight the application of ML and deep learning techniques in evaluating and predicting surface roughness. These approaches allow for proactive adjustments in the machining process, which helps achieve the required surface quality without compromising operational costs [12]. Zhang, Y. et al. [13] proposed an adaptive machining framework utilizing machine learning to optimize cutting parameters. This study demonstrated that real-time adjustments could reduce tool wear and increase machining efficiency, leading to cost savings of approximately 25% while improving cycle times. Surface quality is a critical metric in CNC machining, directly impacting the functionality and esthetic appeal of finished products. Moreira et al. [14] introduced an AI-driven supervision controller that adjusts machining parameters in real time to maintain surface quality. By employing a multi-variable control system, their solution minimizes discrepancies in surface roughness, reducing waste and reprocessing costs. Tested on steel alloys, the system demonstrated its ability to achieve near-perfect surface finishes, highlighting AI’s role in advancing precision manufacturing.

Neural networks have also been used for reducing costs while obtaining the desired surface. Modern lean production methodologies combined with AI can enhance accuracy and efficiency in part manufacturing. Utilizing AI-driven insights, manufacturers can streamline operations and further reduce costs while preserving or even enhancing surface quality [15]. Downey et al. [16] also explored the application of neural networks for real-time monitoring of surface quality during machining. Their model effectively identified anomalies in the machining process, allowing for immediate adjustments to tool paths and parameters, resulting in improved surface quality. Self-supervised learning is a breakthrough in AI that eliminates the need for extensive labeled data. Yavartanoo et al. [17] introduced CNC-Net, a deep neural network (DNN) framework designed to simulate and optimize CNC machining operations. CNC-Net uses 3D-model inputs to generate sequential machining operations autonomously. By learning from iterative simulations, the system refines its operations to achieve exceptional precision in fabricating 3D objects. This framework has been tested on datasets like ShapeNet and demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional CAD reconstruction methods. CNC-Net’s ability to adaptively learn and optimize toolpaths without human intervention represents a significant step forward in automating CNC operations.

The adoption of AI in CNC programming has led to measurable improvements in surface quality. Numerous studies have reported significant reductions in surface roughness, enhanced dimensional accuracy, and improved material utilization. For example, research by Ullrich et al. [18] identifies the need for more integrated, multi-objective AI applications in machining to fully realize the benefits of digital manufacturing. It highlights the potential of AI-driven optimization in transforming traditional machining into a data-centric, intelligent system and outlines a roadmap for future research and implementation. Leshchenko and Dyshev [19] also focused on dynamic parameter adjustments through AI algorithms, eliminating the need for human intervention in error correction. Their study demonstrates how real-time monitoring of spindle speeds, feed rates, and tool alignment can enhance the precision of machining processes. For example, the AI system they developed adjusts machining parameters dynamically to minimize deviations, even when working with complex geometries and materials. This advancement is particularly critical for industries like aerospace and medical device manufacturing, where tight tolerances are non-negotiable. Their work exemplifies how AI can ensure consistent quality, reduce waste, and improve throughput. According to a 2023 report by Deloitte [20], implementing AI-based quality control systems can significantly reduce defect rates—by up to 50%. This reduction is crucial for ensuring high surface quality in machined parts, leading to lower costs associated with rework and scrap materials. Also, AI integration in CNC machining leads to more efficient material usage. By analyzing data and optimizing parameters, AI helps in minimizing waste during the milling process, contributing to overall cost savings while maintaining the quality of the finished products [21]. Precision in CNC machining is paramount, and AI has become instrumental in achieving this objective. Another paper that analyses costs is [22]. This study uses deep learning for manufacturing-cost prediction but lack explainability due to black-box models. This study introduces an explainable AI process using 3D CAD models to predict and visualize cost-driving features, offering design guidance and real-time cost insights for CNC-machined parts. As environmental concerns grow, energy efficiency in manufacturing has become a key focus. Brillinger et al. [23] explored the use of machine learning models to predict and optimize energy consumption in CNC machining. Their research demonstrated that decision tree-based algorithms, particularly Random Forest, could accurately estimate the energy demand of CNC operations based on NC code and part geometries. By linking machining strategies with energy consumption, their model enables manufacturers to adopt energy-efficient practices. This innovation not only aligns with global sustainability goals but also reduces operational costs, making it a practical solution for industries aiming to minimize their carbon footprint.

M. Elahi [24] investigates various AI techniques, including deep learning and reinforcement learning, in the context of CNC programming. The study reveals that these advanced AI methods can enhance decision-making processes in CNC operations, enabling machines to learn from previous tasks and improve over time. In addition to direct machining applications, AI has found utility in production scheduling. Alexopoulos et al. [25] applied deep reinforcement learning (DRL) to optimize job-shop scheduling by selecting the most suitable dispatch rules. Their study highlights the adaptability of DRL agents in dynamic manufacturing environments. For instance, in their simulation involving a bicycle production line, the AI system dynamically assigned tasks to resources, minimizing production delays and improving overall efficiency. This research underscores AI’s potential to integrate CNC operations with broader manufacturing systems, ensuring seamless coordination between scheduling and machining.

Another domain where AI has been used is manual programming. The manual programming of CNC machines, particularly for complex parts, is labor-intensive and prone to errors. Preiss and Kaplansky [26] addressed this challenge by developing an AI-based autonomous part programming system. By integrating CAD input and machine-specific knowledge, their system generates efficient toolpaths and G-code automatically. Their work is notable for its ability to manage intricate operations, such as handling tangential edge transitions and optimizing pocket geometries. The automation of part programming reduces the reliance on skilled operators and significantly speeds up the design-to-production cycle. Additionally, their system includes error-handling mechanisms, ensuring that edge cases are either resolved autonomously or flagged for human review.

The evolution of AI has drastically transformed the field of manufacturing, with CNC programming benefiting immensely from these advancements. AI’s integration enhances precision, automates complex tasks, and reduces human error, thereby boosting efficiency across various industries. The potential is immense, with the ability to transform different facets of society and significantly enhance human life. Production is one of the main areas where AI will make significant changes. However, the widespread implementation of AI also brings forth important concerns regarding ethics, bias, data privacy, and the responsible use of AI technologies. Tackling these issues is essential for fully realizing AI’s benefits for humanity.

The integration of AI into CNC programming offers a multi-faceted approach to overcoming traditional manufacturing challenges. From automating complex operations to enhancing energy efficiency, AI technologies provide scalable and cost-effective solutions. Additionally, the transition toward human-centric manufacturing under Industry 5.0 ensures that the benefits of automation are balanced with social and environmental considerations.

3. Methodology

LLMs training, including tools like ChatGPT [27], is increasingly being integrated across various industries, enhancing processes and offering transformative benefits. One of the most impactful areas of AI application is in the manufacturing sector, where its use has significantly redefined traditional production methods. AI’s role in optimizing manufacturing processes, particularly in CNC machining, cannot be overstated. CNC machining involves the use of G-code to direct machine toolpaths, control speeds, and manage operations with high levels of precision. The need for optimization in this domain is critical, as reducing cycle times and improving surface quality directly translate into cost savings and higher-quality products. AI tools can streamline this optimization process, enabling faster and more accurate adjustments based on real-time data analysis, ultimately leading to more efficient production workflows [28].

While there are several free AI software options available for manufacturers, their adoption may come with certain trade-offs. Free tools can significantly reduce the upfront costs of AI integration; however, they may require substantial in-house technical expertise to properly configure, troubleshoot, and maintain. This can present a challenge for organizations lacking dedicated technical staff. Despite these hurdles, the benefits of adopting such free AI tools are considerable for businesses with skilled teams. These tools can provide a level of agility that proprietary software may not match, enabling companies to customize solutions according to their unique needs. Additionally, free AI tools often come with continuous updates and access to cutting-edge innovations, which can keep an organization ahead of competitors. When combined with the right technical resources, the productivity gains, cost reductions, and innovations derived from using these AI solutions far outweigh the challenges, making them an increasingly popular and cost-effective choice for manufacturers seeking to optimize their operations and improve their bottom line [29].

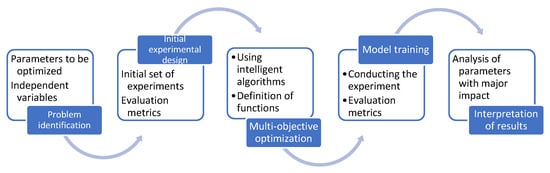

In contrast, dedicated software suits highly regulated industries or niche applications where vendor support and compliance are critical—but for most users, free AI tools deliver comparable (or superior) productivity at a fraction of the cost. To demonstrate its usefulness, ChatGPT was used. The methodology focuses on defining parameters to be optimized and the independent variables. Thus, the optimization inputs were the part drawing and the G-code obtained in Solid Cam. These were introduced into the artificial intelligence program, with the condition of optimizing the surface obtained and the production time, defining the initial set of experiments and establishing evaluation metrics. This case study explores the application of ChatGPT, a generative AI model, to refine G-code for automotive metal parts, demonstrating how AI can augment engineering workflows [30]. The methodology used in this paper is presented in Figure 1. This methodology represents a systematic approach to solving complex optimization problems with multiple competing objectives.

Figure 1.

Methodology.

Figure 1 presents the complete experimental framework:

- Input Phase: Part drawing and baseline G-code generated using SolidCam.

- Optimization Phase: ChatGPT processes the G-code with prompt: “Optimize this code for better surface quality and reduced cycle time.”

- Validation Phase: Physical machining of 3 parts using both conventional and AI-optimized programs.

- Analysis Phase: Comparative measurements of surface roughness (Ra, Rz), dimensional tolerances, form deviations, cycle time, and critical code-structure analysis.

No restrictions or limitations were provided. The only request was regarding the quality of surface and the cycle time. Due to this fact, the independent variables are the cutting regime, the tool parameters, and the operations. The final product cannot be modified. Three parts were used, which were milled using the conventional program using the same parameters: same machine, tools, and clamping setup. Also, for both experiments, lubrication was used. In this way, variation from the process has been eliminated. The optimized program is considered valid and implicit if the parts obtained through post-optimization processing correspond to the initial drawing and an improvement in part quality and productivity is observed. An ISR C-300 Portable Surface Roughness Tester and Axiom Too 3D were used for measuring roughness and dimensional, angular, and form deviations. Regarding the cycle time of the milled part, measurements regarding the machining process were recorded and analyzed.

This study uses ChatGPT as a representative free AI tool to systematically investigate both its optimization capabilities and its failure modes in CNC programming. The experiment will validate if LLMs can provide rigorous, systematic documentation of AI failure modes in specialized domains. In order to obtain a new, better program, the message submitted to ChatGPT was as follows:

“This is a CNC code written by an engineer with which we machined 3 pieces of metal parts for the automotive industry. Please optimize this code and rewrite it in order to obtain better quality of the finished product. Please take into account to optimize cycle times as well.”

The function to be optimized consists of 3 variables, the rest of the inputs remaining constant. Changing the cutting regime also involves changing the productivity as well as the surface quality. Feed rate with a low value and a higher spindle speed generates low productivity, but a much better surface quality. So, the dependent variables were defined as productivity and surface quality.

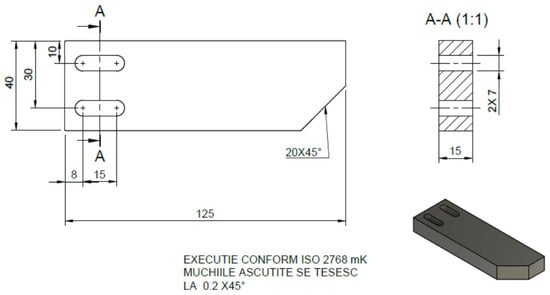

After optimizing the G-code using artificial intelligence, it was re-entered into the machine (Figure 2). A new round of machining was performed. Again, 3 parts were machined. The drawing of the machined part is presented in Figure 3. The part drawing specifies Ra ≤ 3.2 μm (typical for automotive components). The optimization objective was to achieve Ra below this threshold while maintaining geometric compliance. A new set of surface quality measurements was performed. The results from the 2 processes are exemplified in Section Investigating LLM Behavior in G-Code Optimization: Hypotheses for Potential AI Decision-Making Patterns.

Figure 2.

Steps followed to demonstrate the AI use.

Figure 3.

The part under testing.

While G-code simulation software (Vericut 9.6, ICAM V17, CAMWorks 2024) can detect geometric errors and collisions, our research objectives required physical validation due to the fact that we wanted to validate surface roughness—and surface finish depends on interactions between cutting parameters, tool deflection and vibration, material behavior, and thermal effects during the cutting process; to test dimensional accuracy under real cutting conditions, a real machine induces tool deflection under cutting forces, thermal deformation of the part/clamping setup during extended cutting, machine tool positioning errors, and clamping setup vibration. A simple simulation cannot provide data for the problems mentioned because they involve material removal physics, not just geometric collision detection.

Investigating LLM Behavior in G-Code Optimization: Hypotheses for Potential AI Decision-Making Patterns

When LLMs are tasked with optimizing CNC machining code containing dual objectives (quality and cycle-time reduction) without explicit geometric constraints, their interpretation of “optimization” may diverge from manufacturing requirements due to fundamental characteristics of their training and architecture. This section presents three complementary hypotheses that will guide our experimental analysis of how LLMs process and modify G-code. These hypotheses address: (1) potential economic token-minimization behaviors inherent to LLM training paradigms, (2) the absence of geometric semantic understanding in text-based processing, and (3) possible biases embedded in training data that may favor code simplification patterns. By establishing these theoretical frameworks before conducting experiments, we aim to systematically evaluate whether and how LLMs trained on general text handle specialized engineering tasks requiring constraint-aware reasoning beyond pattern recognition.

This is the reason why three hypotheses were tested within this paper:

Hypothesis 1.

LLMs may prioritize economic token optimization.

LLMs are trained to generate output efficiently in terms of token usage. When presented with optimization requests containing dual objectives (quality + cycle time) without explicit geometric constraints, the phrase “optimize cycle times” may be interpreted by AI prediction algorithms as a directive to minimize code length, due to the following:

- Shorter code generates fewer tokens, aligning with reduced computational “cost” in LLM training paradigms.

- Operations constituting larger percentages of total G-code length represent maximum cycle-time reduction potential per token eliminated.

- Removing the longest continuous operation block while preserving shorter operations could achieve apparent optimization goals.

This hypothesis suggests LLMs may apply length-based optimization strategies rather than feature-based reasoning when geometric constraints are not explicitly stated.

Hypothesis 2.

LLMs may lack semantic G-code understanding.

LLMs process G-code as text sequences without inherent understanding of geometric semantics. This could manifest in the following ways:

- Pattern recognition based on syntactic similarity rather than functional comprehension (e.g., preserving commands with similar syntax while eliminating entire operation blocks).

- Inability to recognize that eliminating certain operations creates geometric non-compliance with design specifications.

- Absence of constraint-checking mechanisms comparable to specialized CAM software, potentially resulting in no error messages or warnings about missing critical features.

This hypothesis posits that text-based processing without geometric reasoning capabilities may lead to functionally invalid modifications.

Hypothesis 3.

Training data may introduce systematic biases.

LLMs reflect patterns present in their training data. Potential sources of bias include the following:

- Preference for code minimalism: Programming best practices emphasize concise code; training data likely overrepresents simplified examples.

- Incomplete manufacturing contexts: G-code in training datasets may appear without accompanying technical drawings or specifications, preventing models from learning geometry–code relationships.

- Optimization examples bias: Training examples labeled as “optimization” may disproportionately emphasize removal and simplification rather than preservation and enhancement.

This hypothesis suggests that the composition and context of training data may predispose LLMs toward simplification strategies that conflict with manufacturing requirements.

4. Technological Process of Metal Machining Using a 3-Axis Milling Machine

The technological process of milling a part involves a sequence of steps to transform raw material into a finished component by removing material with rotating cutting tools. For our article, we used the part shown in Figure 3.

For milling the part, we used a Haas VF-3 SS CNC milling machine. The machining accuracy of the Haas VF-3 SS machining center generally refers to the positioning accuracy and repeatability specified by the manufacturer. According to Haas [31] technical specifications, these values are as follows:

- linear positioning accuracy: ±0.005 mm on X, Y, Z, axis,

- repeatability: ±0.0025 mm.

In real applications, the machine can maintain machining tolerances of ±0.01–0.02 mm, depending on the quality of the tools and the clamping setup, the thermal stability of the environment, the operator’s experience, and the machine calibration. At very high speeds, accuracy can be easily affected by vibration or thermal deformation. The use of spindle cooling and lubricant systems is recommended.

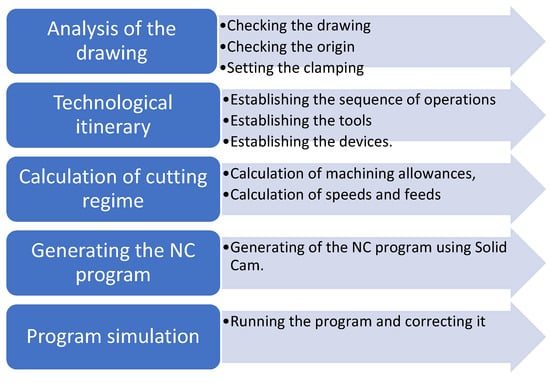

Developing the source program for the machining of a part using CNC involves following the method shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Steps needed to develop the NC program.

4.1. Initial Experimental Design

The role of the experiment is to determine whether artificial intelligence—in this case ChatGPT—can be used to optimize certain functions, and if it can subsequently replace the conventional programs currently used to generate G-code.

The part used for the experiment is presented in Figure 3.

Two clamping setups are used to process the part. In the first clamping, the face milling, contour milling, contour finishing, pocket milling, drilling, and deburring operations are performed, and in the second clamping setup, the face milling and deburring operations are performed. The size of the semi-finished product is 20 × 45 × 130 mm. The material used is 5083 Al alloy with a density of 2.7 g/cm3 and a specific strength of 60 MPa [32].

The sequence of operations for clamping setup 1 is presented in Table 1, and for clamping setup 2 in Table 2. Table 1 and Table 2 also present the tools used for machining and their characteristics (d—diameter, z—no. of teeth, H and D—tool correction register).

Table 1.

Sequence of operations for the first clamping setup.

Table 2.

Sequence of operations for the second clamping setup.

The program used to generate and simulate the milling process is SolidCam, professional CAM software widely used in automotive manufacturing. SolidCAM uses sophisticated algorithms to generate toolpaths that minimize speed and direction variations, avoiding vibrations and stop/start marks that affect roughness. It also uses strategies that maintain constant engagement of the tool in the material, reducing thermal loading and deformations, essential for a uniform finish. Another feature of the program is that it allows for the reduction in sudden changes in tool direction, maintaining a constant cut and avoiding vibrations that cause roughness [33].

Three identical pieces were machined and measured. Critical features such as pockets, holes, and contours are annotated to highlight areas requiring high precision. The drawing shows a general roughness of 3.2 µm, the roughness that needs to be achieved. This indicates a moderate surface finish and is used in applications where a balance between cost and performance is required.

The machined part can be seen in Figure 5. The cycle time needed to machine the part was measured using a timer and was equal to 2.39 min.

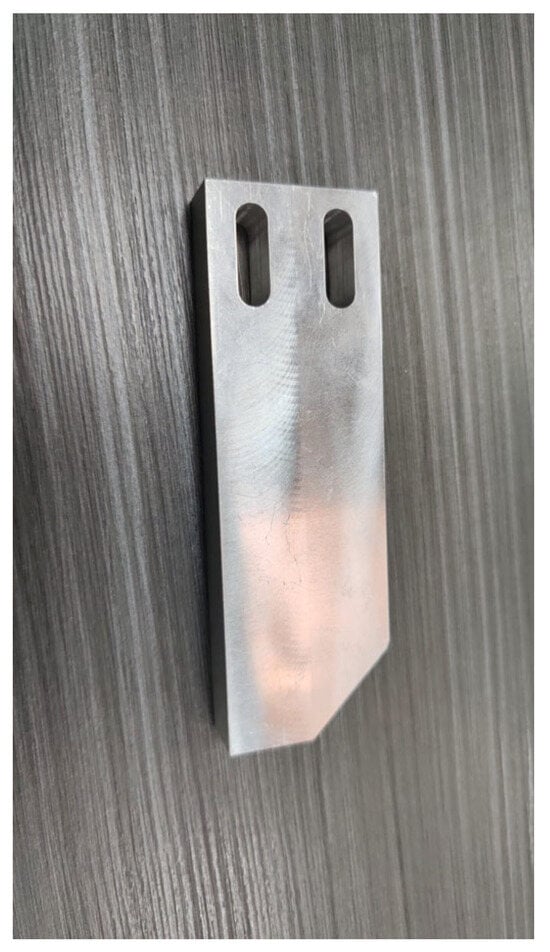

Figure 5.

The part obtained using conventional programming.

4.2. Optimized Experimental Design

To machine the part from Figure 3 using the program optimized by ChatGPT, we followed the steps presented in Figure 2 in the AI programming branch. Thus, as in the initial experimental design, for milling the part, two clamping setups were used. For the first clamping setup, AI defined 5 tools for milling the part, presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sequence of operations defined by AI for the first clamping setup.

It can be observed that the pocketing operations were eliminated. This is the main reason why the machined part will certainly not correspond to the 2D drawing.

For the second clamping setup, the operation and tools are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sequence of operations defined by AI for the second clamping setup.

The next step that must be followed from the methodology after obtaining the tools and the cutting regime is to optimize the G-code obtained from SolidCam using AI, in our case ChatGPT. The optimization aims to improve cycle time as well as the surface quality.

The milled part obtained after the use of AI is presented in Figure 6. With a simple glance at the milled part, one can see the essential difference in terms of design: the elimination of the pocket channel and the addition of the 4 holes. This is the reason why we can say that the piece is rejected. Also, in order for machining to be possible, features were added when performing the milling: the G43 tool correction was added (without it, the part would be destroyed and the tool would break). Analyzing the time to obtain the part, it is also observed in this case that the elimination of an operation had a significant impact on the part. Thus, the value of 1 min and 45 s was obtained.

Figure 6.

The part obtained using optimized programming.

Unfortunately, the experiment demonstrated that the GPT-generated code cannot run safely without human intervention.

The elimination of pocket-milling operations represents the most critical AI failure in our study. Our study demonstrated that LLMs failed to generate a correct code, and instead generated errors, due to three hypotheses that were tested:

Hypothesis 4.

LLMs are trained to generate economic optimization.

LLMs are trained to generate concise outputs. Analysis of the initial message (“Please optimize this code and rewrite it in order to obtain better quality of the finished product. Please take into account to optimize cycle times as well.”) that was provided to ChatGPT reveals that the message contained dual objectives (quality + cycle time) without explicit geometric constraints. The phrase “optimize cycle times” may have been interpreted by the AI prediction algorithm as a directive to minimize code length, due to the following reasons:

- -

- Shorter code = fewer tokens = reduced computational “cost” in LLM training paradigm.

- -

- Pocket-milling operation constituted 31% of total G-code length (Table 5).

- -

- Removing longest operation achieves maximum cycle-time reduction per token eliminated.

As a result, ChatGPT consistently removed the longest continuous operation block while preserving shorter operations, suggesting length-based optimization rather than feature-based reasoning.

Hypothesis 5.

Lack of semantic G-Code understanding.

LLMs process G-code as text sequences without understanding geometric semantics. In this direction, we can see that it has pattern recognition failure (AI preserved G03 commands in deburring (similar syntax) but eliminated entire pocket blocks)—this suggests pattern-matching on operation headers rather than geometric comprehension. Also, it did not recognize that eliminating pockets creates geometric non-compliance. This is why no error message or warning was generated about missing features, suggesting the absence of constraint-checking mechanisms present in specialized CAM software.

Hypothesis 6.

Training data bias.

LLMs reflect patterns in training data. Potential causes are as follows:

- Preference for code minimalism: Programming best practices emphasize concise code; training data likely overrepresents simplified examples.

- Incomplete manufacturing contexts: G-code in training data may appear without accompanying drawings/specifications, preventing the AI from learning geometry–code relationships.

- Optimization examples bias: Training examples of “optimization” may emphasize removal/simplification more than preservation/enhancement.

The comparative analysis (Table 5) reveals a paradoxical optimization pattern: while the AI-optimized version achieved a 37% total cycle-time reduction (54 s saved), this improvement came at the cost of complete elimination of the pocket-milling operation—a critical feature-creation step that comprised 28% of the original cycle time (45 s).

Table 5.

Critical safety feature omissions.

The data demonstrates non-uniform optimization across operations. Surface-level operations (face milling, contour roughing, drilling) showed moderate reductions (20–25%), while finishing operations (contour finishing, deburring) experienced minimal changes (6–9%). The complete removal of pocket milling, rather than its optimization, suggests the AI prioritized cycle-time reduction through operation elimination rather than process efficiency improvement within individual operations.

This pattern supports the hypothesis that LLMs may interpret “optimization” as code minimization rather than manufacturing-process improvement. The AI achieved numerical superiority in cycle-time metrics while fundamentally compromising geometric compliance—a result that would be immediately flagged as invalid by domain-aware CAM software but passed undetected through text-based LLM processing.

Key findings: 83% of time savings (45 of 54 s) came from eliminating pocket milling—an invalid optimization producing a non-compliant part. Only 17% (9 s) represents legitimate optimization.

5. Roughness and 3D Measurements

Finally, the surface roughness of the machined specimens was measured in terms of the average surface roughness, Ra. During the measurement process, each sample was carefully positioned on a stable, flat surface to minimize vibrations or movement. The tester’s stylus was precisely aligned with the sample’s surface and traversed along a predefined evaluation length to capture roughness data. Surface roughness (Ra) values were recorded for each sample, with measurements conducted in three different sections per sample. The roughness evaluation was performed over a sampling length of 2.5 mm and a total evaluation length of 12.5 mm to ensure comprehensive data collection. After the measurements were performed, the average values of the Ra measured in three different sections were introduced in the design matrix. The results were then analyzed using Design expert software. The surface roughness of 3D-printed samples was evaluated using the ISR C-300 Portable Surface Roughness Tester, manufactured by Insize (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Roughness measurements.

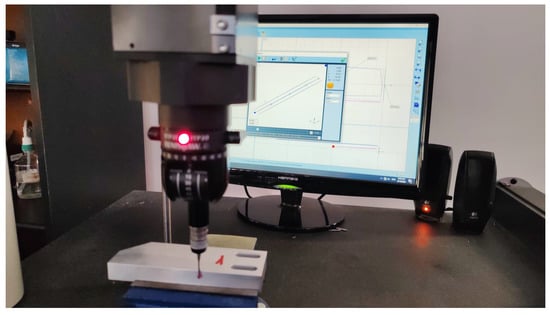

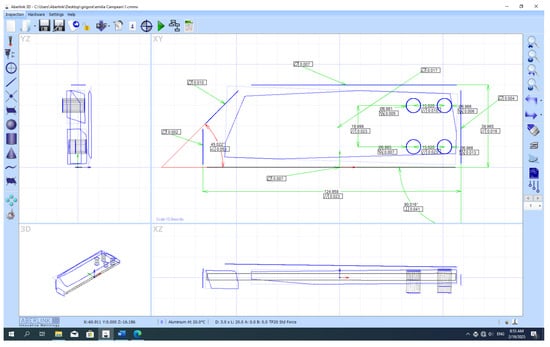

For dimensional, angular, and form deviations, the Axiom Too 3D measuring machine, a coordinate measuring machine (CMM) produced by Aberlink (Aberlink Ltd., Gloucestershire, UK), was used. The measurements were conducted in the 3D measurement laboratory of the Technical University of Cluj-Napoca under controlled conditions at 20 °C and 50% humidity, using an Axiom Too CMM (Gloucestershire, UK) and its firmware software (Aberlink 3D, Version 4.22). Figure 8 shows the CMM measuring one of the parts and the following dimensions were measured:

Figure 8.

Three-dimensional measurements.

- Deviations, including flatness and cylindricity tolerances.

- Orientation tolerances, perpendicularity, and parallelism.

- Linear dimensions, showing the actual deviation from the nominal size.

- Angular dimensions.

For each unit (plane, cylinder) a minimum of 10 points evenly distributed were measured across 3 different sections and the results were documented in the report. Before measurement, all surfaces were meticulously cleaned to remove any dust, oil, or debris that could compromise accuracy. To maintain consistency in surface properties, the samples were stored in a controlled environment for at least 24 h prior to testing.

6. Results

Table 6 presents the values obtained for surface roughness measurements (Ra and Rz) comparing results from manual programming by SolidCam and AI-driven programming. The differences between the two methods are striking. For example, the average Ra value from conventional programming (0.68 µm) is six times higher han the AI’s result (0.11 µm). The same pattern holds for Rz: conventional-programmed surfaces averaged 4.5 µm, while AI programming produced much smoother surfaces at just 1.27 µm—about four times lower. These findings suggest that AI programming yields significantly smoother surfaces, highlighting its potential for improving surface quality and precision in manufacturing processes.

Table 6.

Measured values for surface roughness parameters.

Table 7 presents the measured values for the analyzed geometrical and dimensional tolerances from Figure 9. The results show that form and orientation tolerances exhibit minimal differences between conventional and AI programming, with variations not exceeding 13 µm. However, larger discrepancies were observed in dimensional tolerances, specifically in the height and length of the part. In these cases, AI programming resulted in smaller deviations from the nominal size, with maximum variations remaining below 30 µm. These findings suggest that while both approaches perform similarly in maintaining geometric accuracy, AI programming offers an advantage in achieving more precise dimensional tolerances. Taking into account all the analyzed data, the experiment demonstrated that the result obtained using the AI software was a systematic result; artificial intelligence could provide the best solution for generating a good surface, but in its attempt to optimize the program, it eliminated important parts of it, leading to tool breakage and damage to the workpiece if not for programmer intervention. At this stage, it cannot yet be used in optimizing CNC programs. The AI’s optimization created a paradox: a component with superior surface finish on existing features but missing essential geometry specified in the design. This exemplifies a critical failure mode in AI-assisted manufacturing—the generation of locally optimal but globally invalid solutions. While total surface area differs, our comparison focuses on surfaces machined in both versions: face milling, external contours, drilled holes, and deburred edges. Pocket surfaces exist only in conventional parts and were excluded from comparative analysis.

Table 7.

Measured values for dimensional and geometrical tolerances.

Figure 9.

Three-dimensional measurements report for part 1 produced using conventional generated CNC programming.

This outcome reveals that AI optimization without holistic manufacturing constraints and geometric verification produces parts that are simultaneously “better” and “unusable.” The system optimized measurable metrics (surface roughness, cycle time) while ignoring the binary constraint of design compliance. This represents a critical lesson for AI integration in manufacturing: technical competence in parameter optimization does not compensate for the absence of constraint-aware reasoning that ensures solutions remain within the feasible design space. Manufacturing AI systems require explicit geometric validation frameworks, not merely performance-optimization algorithms.

7. Conclusions

The current study presents a detailed comparison between 2 CNC programs: one generated by SolidCam, and the other optimized by free AI software powered by ChatGPT. The results show significant distinctions in terms of toolpath logic, program structure, machining quality, and overall cycle time. Even though the cycle time was significantly reduced from 2 min and 39 s to 1 min and 45 s, the LLM optimization removed one of the machining operations (pocket milling) and the tool compensation, and revealed limitations like improper use of safety codes, inadequate path verification protocols, and removal of return-to-safe-position codes (G28).

This removal of one of the milling operations and of the tool compensation led to obtaining a non-compliant part that does not meet the original 2D drawing specifications. Regarding tool life, this study focused specifically on delivering to the manufacturing community systematic, empirically grounded documentation of how AI systems fail when confronted with domain-specific technical tasks requiring specialized knowledge. The AI-optimized program increased cutting speeds by 8–17% (from S6000 to S6500–7500 RPM) and feed rates by 20–50% (from F800–2000 to F1000–3000 mm/min), which theoretically accelerates tool wear. However, comprehensive tool life analysis is needed. The AI-optimized program increased cutting speeds by 8–17% and feed rates by 20–50%, which would theoretically accelerate tool wear. Future research should investigate tool wear implications. From a performance standpoint, improving surface quality led to lack of design fidelity and machining safety, demonstrating the current limitations of LLMs in replacing specialized CAM software or experienced human programming in high-precision manufacturing. Future research could explore tighter integration of AI tools like ChatGPT with established CAM software (e.g., SolidCAM 2024, Fusion 360 2.0.21538, Mastercam 2024) via APIs (Application Programming Interfaces). This hybrid model may allow AI to suggest optimizations while maintaining the geometric and manufacturing constraints handled by professional CAM tools. AI’s better surface roughness (0.68 μm → 0.11 μm) stems from more aggressive parameters, not superior logic. Critically, these improvements came at the cost of geometric non-compliance—demonstrating AI optimization without holistic constraints produces locally optimal but globally invalid solutions.

Future work will focus on implementation of multi-stage verification systems that automatically analyze AI-generated machining code, validate geometric compliance with design documentation, confirm inclusion of required safety protocols, and perform pre-execution simulation to detect errors before material commitment.

This study’s scope is deliberately focused on a single automotive aluminum alloy component (5083 Al) machined on a Haas VF-3 SS CNC machine. We acknowledge the limitations regarding the scope (single part geometry: the test part contains specific features (pockets, contours, holes, face milling) common in automotive components but not exhaustive of all manufacturing geometries); material specificity (results apply to 5083 aluminum alloy; behavior may differ for hardened steels, titanium, composites, or other materials); machine constraints (findings are based on three-axis milling; four/five-axis machining, turning, or multi-process operations not addressed); and AI version dependency (ChatGPT capabilities evolve; findings reflect the version used in late 2024/early 2025).

At present, the current free LLMs cannot replace CAM software or specialized programmers in production environments. They miss three capabilities: understanding geometric data, having conscious reasoning about constraints, and preserving safety protocols. One of the main objectives of Industry 5.0 is represented by identifying parameter-optimization opportunities that human programmers can validate and implement. So, the 20–50% feed rate improvements and 8–17% spindle speed increases suggested by LLMs represent genuine optimization insights—they simply require expert verification before deployment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C. and G.P.; Methodology, E.C. and G.P.; Software, E.C.; Validation, G.P.; Investigation, E.C. and G.P.; Resources, E.C. and G.P.; Writing—original draft, E.C. and G.P.; Visualization, E.C.; Supervision, E.C.; Project administration, E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Industry 5.0. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/research-area/industrial-research-and-innovation/industry-50_en#what-is-industry-50 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Lei, Z.; Shi, J.; Luo, Z.; Cheng, M.; Wan, J. Intelligent Manufacturing From the Perspective of Industry 5.0: Application Review and Prospects. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 167436–167451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Machine learning and artificial intelligence in CNC machine tools, A review. Sustain. Manuf. Serv. Econ. 2023, 2, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, W. Application of Machine Learning to the Prediction of Surface Roughness in the Milling Process on the Basis of Sensor Signals. Materials 2022, 18, 148. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Vogel-Heuser, B.; Wang, L. Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—Inception, conception and perception. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 61, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharath, S.; Natraj, K. Application of Artificial Intelligence Methods of Tool Path Optimization in CNC Machines. In International Journal Of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) Confcall—2018 (Volume 06—Issue 14); IJERT: Gujarat, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini, M.; Mezzogori, D.; Neroni, M.; Zammori, F. Machine Learning for industrial applications: A comprehensive literature review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 175, 114820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukreja, P.A.; Pande, S.S. Optimal toolpath planning strategy prediction using machine learning technique. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B. Cutting Tool Wear Prediction in Machining Operations, A Review. J. New Technol. Mater. 2022, 12, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Möhring, H.-C.; Eschelbacher, S.; Georgi, P. Machine learning approaches for real-time monitoring and evaluation of surface roughness using a sensory milling tool. Procedia CIRP 2021, 102, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Kim, T.J.; Wang, X.; Kim, M.; Quan, Y.-J.; Oh, J.W.; Min, S.-H.; Kim, H.; Bhandari, B.; Yang, I. Smart machining process using machine learning: A review and perspective on machining industry. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2018, 5, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wu, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tao, F.; Wang, Y. A generic energy prediction model of machine tools using deep learning algorithms. Appl. Energy 2020, 275, 115402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, Z. Adaptive machining framework for the leading/trailing edge of near-net-shape integrated impeller. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 107, 4221–4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.C.; Li, W.D.; Lu, X.; Fitzpatrick, M.E. Supervision controller for real-time surface quality assurance in CNC machining using artificial intelligence. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 127, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Xia, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X. A Novel CNC Milling Energy Consumption Prediction Method Based on Program Parsing and Parallel Neural Network. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, J.; O’SUllivan, D.; Nejmen, M.; Bombinski, S.; O’lEary, P.; Raghavendra, R.; Jemielniak, K. Real Time Monitoring of the CNC Process in a Production Environment- the Data Collection & Analysis Phase. Procedia CIRP 2016, 41, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavartanoo, M.; Hong, S.; Neshatavar, R.; Lee, K.M. CNC-Net: Self-Supervised Learning for CNC Machining Operations. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 9816–9825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, K.; von Elling, M.; Gutzeit, K.; Dix, M.; Weigold, M.; Aurich, J.C.; Wertheim, R.; Jawahir, I.; Ghadbeigi, H. AI-based optimisation of total machining performance: A review. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 50, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshchenko, O.; Dyshev, O. Achieving the Required Machining Accuracy by CNC Programming AI. Science.lpnu.ua. Ukr. J. Mech. Eng. Mater. Sci. 2024, 10, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/consulting/articles/using-ai-in-predictive-maintenance.html (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Daniyan, I.; Tlhabadira, I.; Daramola, O.; Mpofu, K. Design and optimization of machining parameters for effective AISI P20 removal rate during milling operation. Procedia CIRP 2019, 84, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyoung, Y.; Namwoo, K. Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Manufacturing Cost Estimation and Machining Feature Visualization. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillinger, M.; Wuwer, M.; Hadi, M.A.; Haas, F. Energy prediction for CNC machining with machine learning. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2021, 35, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, M.; Afolaranmi, S.O.; Lastra, J.L.M.; Garcia, J.A.P. A comprehensive literature review of the applications of AI techniques through the lifecycle of industrial equipment. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2023, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, K.; Mavrothalassitis, P.; Bakopoulos, E.; Nikolakis, N.; Mourtzis, D. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Selection of Dispatch Rules for Scheduling of Production Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiss, K.; Kaplansky, E. Automated part programming for CNC milling by artificial intelligence techniques. J. Manuf. Syst. 1985, 4, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChatGPT. Available online: https://openai.com/index/chatgpt/ (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Shamsuddoha, M.; Khan, E.A.; Chowdhury, M.M.H.; Nasir, T. Revolutionizing Supply Chains: Unleashing the Power of AI-Driven Intelligent Automation and Real-Time Information Flow. Information 2025, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praxie. Available online: https://praxie.com/ai-in-manufacturing-industry/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Rivet, I.; Dialami, N.; Cervera, M.; Chiumenti, M.; Valverde, Q. Mechanical analysis and optimized performance of G-Code driven material extrusion components. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 61, 103348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas Tooling. Available online: https://www.haascnc.com/haas-tooling.html?utm_term=&utm_campaign=ENG_GPM_Tooling&utm_source=adwords&utm_medium=ppc&hsa_acc=2937336482&hsa_cam=22058431606&hsa_grp=&hsa_ad=&hsa_src=x&hsa_tgt=&hsa_kw=&hsa_mt=&hsa_net=adwords&hsa_ver=3&gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjw2N2_BhCAARIsAK4pEkU9PSeALWXVDFyflYDZYxlw5_KvABjMpJk1X1aNy1krNLPt7oHf0RUaAkNNEALw_wcB (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- AZO Materials. Available online: https://www.azom.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=2804 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- SolidCam. Available online: https://www.solidcam.com/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.