Abstract

Modularization fails to adequately meet the diverse customer requirements and the product operational data for complex equipment of port shipping (CEPS). To address this challenge, we propose a module configuration design approach (MCDA) that incorporates module parameter planning (MPP) and service module customization (SMC). Initially, the design ranges and weights of functional requirements are established using fuzzy information derived from customer requirements, facilitated by fuzzy quality function deployment. Subsequently, a multi-objective model of MPP is developed, incorporating the cost utility, information content, and delivery time of module and product based on a probabilistic assessment of module instances from operational data. The non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II (NSGA-II) is employed to derive the solution set for MPP. The personalized configuration of the Pareto solution set for SMC is derived based on each objective function pair. Finally, we illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach through a case study involving a wheel loader and method comparison.

1. Introduction

Modularization is an effective methodology to make positive promotions to the product life cycle [1]. To implement the modularization strategy, primary parameters of partitioned modules should be identified, and module parameters would have many values, which may be discrete or continuous; all the module parameters constitute module parameter planning (MPP) [2]. Some parametric modules and customized modules with uncertain valued parameters are designed to achieve the function requirements (FRs), which are mapped from customer requirements (CRs) [3,4]. However, the fuzziness of CRs leads to the inaccuracy of FRs, where service module customization (SMC) is not considered. As well, a specific parametric module in MPP will be difficult to pick over with the increase in the number of modules, and then the result of MPP cannot be applied in engineering design directly. Thus, a module configuration design approach (MCDA) that incorporates MPP and SMC specifically for complex equipment of port and shipping (CEPS) must be carefully established, planned, and managed. It would be dramatically significant to establish the MCDA framework for MPP and SMC based on heterogeneous data of CRs and product operations.

With the development and confluence of big data, artificial intelligence, and the internet of things, a multitude of profound changes and emerging trends in the design field have been witnessed [5,6,7]. These works primarily offer high-level, directional discussions about the digital transformation in design, yet they lack detailed implementation pathways for applying these technologies to specific domains, such as CEPS. Thereinto, modularization, as the foundation of module partition, is an effective strategy to reduce the cost of product research and development [8,9,10]. While these studies confirm the value of modularization, they often focus on traditional, function-and-physics-based partitioning, without fully exploring how to leverage operational data to dynamically guide and optimize module configuration planning. Over the last decade, many approaches of modularization have been introduced based on product function [11], manufacturing and assembly [12,13], and product design [14,15], as well as innovation design methods [16,17], where these studies rely on function-driven or data-driven approaches to improve product performance. So far, few studies have addressed the issue of MPP and SMC based on heterogeneous information, especially for CEPS based on heterogeneous CR data and product operational data. Fortunately, all these issues can be viewed as combinational optimization problems to achieve an optimal combination of discrete model parameters or attribute levels [18,19]. The limitation of these approaches is that their optimization objectives often rely on static and subjective evaluations and lack the integration of real-time operational data from the product lifecycle, leading to solutions that may diverge from actual operational performance. Then, they obtain the best alternative scheme.

The MCDA incorporating MPP and SMC should be presented to derive the FRs of the product and achieve the personalization value of the module parameter. Among these presented MPP approaches, the part-worth model and the information axiom are effective methods to calculate the cost utility of the parametric module and the information content of FRs, respectively. The quality function deployment (QFD) [20] and Kano model [21] are effective ways to measure the CRs and their satisfaction. The conjoint analysis [22] is another widely adopted method to explore the configuration scheme in product design. The product configuration approach has turned out to be one of the most popular preference-based techniques for presenting new product concepts or product-service systems [23]. However, MPP should be established to achieve the FRs as much as possible and obtain a near-optimal product concept, which the product operational data and SMC do not have. Thus, personalization configuration of parametric modules and customized modules for MPP and SMC should be established and managed to improve the satisfaction of customers.

In this article, an integrated MCDA approach for CEPS is presented to derive MPP and SMC based on heterogeneous CR data and product operational data. The rest of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the literature review of this study. Section 3 introduces the basic concepts of FRs and module configuration, and the proposed approach for the MCDA is introduced. Section 4 presents a real-world case study of a wheel loader to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. Finally, the conclusions as well as future work of this study are summarized in Section 5.

2. Literature Review

MPP and SMC technologies have focused on the assembly process of products that require high development costs and technology contents, along with a long lead time for application [24]. This section reviews the related works for CRs and MPP as well as SMC, which are the major issues of the MCDA for CEPS.

2.1. CRs for Complex Equipment

The trend of diversity and personalization of CRs posed great challenges in design and development. CEPS, such as cranes, excavators, and loaders, are widely used in ports and shipping, including the handling of goods, loading and unloading, etc. In CR modeling, Li et al. [1] built an integer programming model based on CRs to plan the combination of modules of complex equipment products. This provides a mathematical method for obtaining optimal module combinations. However, the model heavily relies on precise, static customer data and does not incorporate product operational data. Chiu et al. [25] developed a smart product service system that leverages unsupervised NLP and deep learning to transform customers into active data producers for personalized recommendations and value cocreation. Ji et al. [26] proposed a two-layer optimization model for joint decision-making in technical systems and material reuse modularization based on a constrained genetic algorithm. Nevertheless, the approach remains static and rigid in handling CRs, lacking consideration for operational feedback. Zeng et al. [27] studied the inclusive relationship between parametric models based on the Apriori algorithm by comparing the confidence of frequent itemsets and taking product data as the object. Hu et al. [28] proposed Kano-based engineering feature mapping and artificial immune system-based product design models to comprehensively meet CRs for product characteristics and obtained product design solutions. Cheng et al. [29] proposed a coupling analysis method based on axiomatic design and a module association matrix for the product family design coupling problem and analyzed the corresponding association relationships among product family CRs, FRs, design parameters, and modules. This helps reduce management complexity in product family design. The relationships are established based on static expert judgment or historical data, without leveraging operational data for validation and dynamic updates. Ma et al. [30] proposed a framework to identify and redesign key functional modules based on performance degradation analysis by considering causal associations of functional failures. Dou et al. [31] established an evolutionary game-based CR response model for the customer-side multi-energy load coupling problem. Qu et al. [32] provided a systematic method to capture the smart manufacturing systems requirements list and explain the complex relationship between the smart manufacturing systems and their multi-stakeholders. The perspective is macro- and system-level, offering only indirect guidance for module configuration at the product level.

Based on the above analysis, customer or market requirements were derived through various methods, including market research, customer evaluations, questionnaires, online data sources [33], and product operation data [34]. Consequently, this information was incorporated into the developed cost–benefit or satisfaction function model to identify the optimal combination of module parameters. However, those approaches are hindered by a reliance on subjective and one-dimensional evaluation information, a limited modeling perspective, and a lack of consideration for post-production services. As a result, they fail to meet the diverse expectations of different customers and the subsequent SMC. Therefore, there is a pressing need for multi-objective planning that integrates heterogeneous data from CRs and product operational data to enhance MPP for CEPS.

2.2. Methods of MPP and SMC

Traditional MPP and SMC problems primarily rely on the subjective evaluations of designers, which can directly impact project schedules. Customers possess diverse requirements for products, necessitating that they be suitable for their intended applications, cost-effective, and supported by robust product services. Modular design is recognized as an effective approach to address these MPP and SMC challenges. Within a modularization strategy, a product is decomposed into modules, each characterized by a set of instances defined by continuous or discrete parameters, resulting in a combinatorial optimization problem known as NP-hard. Researchers have investigated various design methodologies for MPP and SMC tailored to complex equipment, as outlined below.

Wang et al. [34] presented an optimization design method of a wheel loader gearbox considering product operational big data based on the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II (NSGA-II) and multi-objective particle swarm optimization (MOPSO) algorithm. Oliva and Opabola [35] presented a framework that integrates hazard characterization, facility-specific exposure assessment, fragility model selection, damage simulation, and fault tree analysis to estimate the probability of operational disruption under given hazard intensity measures. Li et al. [36] introduced a novel modularization method of the complex product, which incorporates the modularity and the scope of design change propagation. This helps design module architectures that are stable with minimal change propagation. However, it focuses on managing changes during design and does not explore using operational data to guide initial MPP. Hou et al. [37] proposed an innovation evolution method for product families to address the shortcomings of research on dynamic evolution mechanisms and systematic innovation methods. This provides a methodology for the long-term evolution of product families. It focuses on macro-level technical evolution rather than supporting real-time module configuration for individual custom orders. To enhance worker experience, Ulmer et al. [13] introduced an adaptive manufacturing assistance system based on hardware modularization and gamified instructions tailored to individual workers. Given the high coupling and heterogeneity characteristics among complex equipment component modules, Li et al. [38] proposed a module division method based on a weighted complex network. To address complex product modularization, Liu et al. [10] introduced a network-based method that employs stable overlapping community detection and genetic algorithm optimization for superior module partition. Zhang and Du [39] established a mixed integer nonlinear two-layer programming model with product family configuration design as the main focus and remanufacturer selection decision as the secondary focus to optimize remanufactured product family configurations. This optimizes the configuration of remanufactured product families. The model is tailored for the remanufacturing context and faces challenges in handling uncertainty and dynamic data. Li et al. [40] introduced the concept of a digital twin to the multidisciplinary collaborative design of complex mechanical products. This provides a vision for interaction and iteration between the design and physical spaces. It is a conceptual framework that lacks detailed models and algorithms for its specific implementation in configuration design. Yang et al. [6] established a technology association-based project organization and task dependency network model by identifying functional associations and organizing execution associations between tasks. Macherki et al. [41] formulated the self-reconfiguration of manufacturing systems as a constraint satisfaction problem solved using Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMTs), providing a formal logic-based approach for dynamic module and layout reconfiguration. Lai et al. [42] determined module redesign priorities by the ratio of a green performance evaluation value to a proposed functional commonality index value based on a product family hierarchy model. Forti et al. [43] presented the integration process of two modularization methods. Wang et al. [44] proposed a novel precooling strategy based on multi-modules, in which the precooler is divided into multiple identical modules, and the number of modules cooled by different fuels could be regulated. This study provides a flexible engineering design adaptable to different working conditions. It is a highly specific solution where modularization refers to physical replication of parts, differing from the parametric customization of functional modules in product family design.

From the preceding discussion, it is evident that the design methodologies for MPP and SMC of complex equipment primarily emphasize modularization strategies. However, the previously mentioned excessive reliance on modularization strategies is associated with limitations, such as a singular modeling perspective and a lack of diverse solution approaches, as well as insufficient attention to the personalization of parametric modules and customized modules for MPP and SMC. Consequently, these approaches fail to adequately address the varying expectations of different CRs. Therefore, it is essential to integrate heterogeneous data from CRs and the engineering data of CEPS to develop a framework of the MCDA that incorporates MPP and SMC.

To sum up, this study is structured around addressing the following three research questions (RQs):

RQ1: How can a heterogeneous data-driven framework be constructed to effectively integrate CRs and product operational data for the module configuration of CEPS?

RQ2: How can a multi-objective optimization model for MPP be formulated and solved to balance the trade-offs among cost utility, information content, and delivery time?

RQ3: How can a linkage mechanism between MPP and SMC be established to enable adaptive personalization based on optimal module configuration schemes?

2.3. Research Gap and Contribution

As a classic modular design challenge, MPP and SMC of complex equipment cannot be effectively resolved through a singular approach. The identified research gaps are summarized as follows.

(1) Limited data-driven personalization configuration. Existing modularization strategies for complex equipment predominantly emphasize functional standardization, lacking robust methodologies to integrate heterogeneous data, such as usage scenarios and operational preferences with product operational data [10]. In contrast to these standardized approaches, our work leverages both CRs and operational data for personalized configuration. The traditional QFD method for deriving FRs relies on static and homogeneous customer feedback, thereby failing to capture dynamic and multi-source operational data (e.g., sensor logs, product operational data, and failure risk information) that significantly influence long-term product performance [14,20]. This study addresses this gap by employing fuzzy QFD to process imprecise CRs and incorporating operational data into the process of requirement mapping.

(2) Lack of integrated service customization. Most studies treat module configuration and module customization as distinct processes, thereby missing opportunities for synergistic optimization in the product lifecycle management [45,46]. Unlike these decoupled approaches, the proposed MCDA integrates MPP and SMC within a unified framework. Additionally, current MPP methodologies often prioritize singular objectives (e.g., cost minimization, time reduction, or value maximization), neglecting to balance trade-offs among part-worth utility, information entropy, and delivery time. This oversight can result in module configurations that do not align with real-world operational constraints [22]. Our research tackles this limitation by formulating a multi-objective optimization model that simultaneously considers these three critical factors.

Motivated by the above discussion, this study proposes an integrated framework for the MCDA aimed at deriving MPP and SMC for CEPS based on heterogeneous data from CRs and product operational data. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows.

(1) The fuzzy QFD (FQFD) was utilized to map CRs to FRs and to delineate the design range, with the weights of FRs calculated using triangular fuzzy numbers. This approach, unlike the traditional QFD, effectively handles the fuzziness in CRs. A multi-objective model for MPP was constructed, incorporating the cost utility, information content, and delivery time of the module and product based on product operational data. This model provides a more comprehensive and balanced solution compared to single-objective models prevalent in the literature.

(2) This study introduced a heterogeneous data-driven MCDA framework that integrates CR information and product operational data for CEPS specifically. This directly addresses the data integration gap identified in existing modularization strategies. A multi-objective optimization model based on the NSGA-II with an elite strategy was developed to address the Pareto optimal problem.

(3) A mechanism linking MPP and SMC was presented to Pareto optimal product configurations, facilitating adaptive post-sale services that included predictive maintenance and spare part recommendations. This linkage is a novel contribution, overcoming the process isolation issue noted in prior research. The superiority of this approach is demonstrated through a case study of a wheel loader, which reveals enhanced customer satisfaction and reduced lifecycle costs compared to conventional design methodologies of modular configuration.

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Acquisition of FRs

Each divided module will encompass several module instances, each characterized by continuous or discrete parameter values, thereby forming module combination planning schemes to address various CRs. Prior to planning the parameter values, it is essential to select the relevant CRs. These CRs are gathered based on company orders and subsequently integrated and ranked by weighting their significance. The weighted CRs are then mapped to FRs using FQFD [45], which is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mapping relationships on CRs, FRs, and design parameters.

The range of design parameters and weights of FRs is determined according to the values of FRs. The mapping relationship transformation of FQFD and determination of FR weights are performed using triangular fuzzy numbers as follows:

where is the correlation between the gth CR and jth FR after normalization, is the correlation between the tth FR and jth FR after normalization (expressed as a triangular fuzzy number), and and are the respective weights of CRs and FRs.

3.2. Conceptual Description of Module Configuration

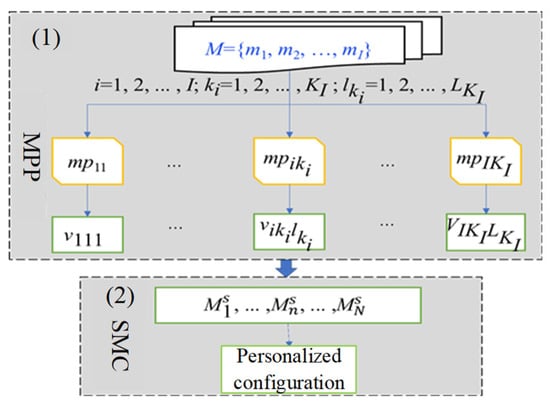

The proposed MCDA of CEPS can be divided into two stages (as shown in Figure 2), including phase (1) MPP and phase (2) SMC. Some concepts and descriptions are defined as follows.

Figure 2.

Two stages of the MCDA.

Definition 1.

The set of functional modules of MPP is represented as ; the set of module instances contained in each module is ; and the list of parameter values for each module instance is .

Definition 2.

The set of functional modules of SMC is represented as , where the results obtained from MPP have an association relationship f with SMC, and the weighting matrix is obtained by integrating the scheme service evaluation matrix to obtain the service module ranking, i.e., the more the configuration scheme is associated with a service module, the more it satisfies personalization requirements.

Definition 3.

If the ith module instance is capable of generating an acceptable utility to the jth functional requirement FR, then the ith module should be capable of reuse to reduce the load of redesign. According to the part-worth utility model [1], the utility of the ith module to the jth FR is assumed to be the part-worth utility preference function for the parameter values of module mi as follows:

where is the utility weight of parameter of module mi; is the part-worth utility of FRj to the value of parameter ; is the error trend of each FR module pair; and is a binary variable.

Definition 4.

If module mi is assembled from integral parts of type f1 and parts of type f2, then its engineering cost ECi (i = 1, 2, …, I) can be expressed as

where is the cost of module mi with type f2 input parts; is the quantity requirement; and are the cost rate and working time, respectively, of the module mi assembly operation; is the cost of using integral parts of type f1 by module mi; and is the quantity requirement. Since the input part of module mi is the output of the relevant manufacturing process, the cost of module mi using integral parts of type f1 can be calculated as follows:

where is the manufacturing cost of a part of type f1 at manufacturing center w, is the raw material cost, is the input material cost, is the cost rate (¥/h) for setting up operation w (CNY/h), and t is the manufacturing time.

Definition 5.

According to the information axiom [21] that a good engineering product concept should satisfy functional independence while containing the least possible information, the amount of information that satisfies FRj with probability of success pj (j = 1, 2, …, J) is as follows:

If FR is a fuzzy variable, then its success probability pj (determined by the desired design range and system range given by the customer) can be expressed as follows:

where the common range is the overlap area between the design and system ranges on a uniform probability distribution curve, the design range is defined by the designer to satisfy the FR, and the system range is the range within which the system can be delivered to the customer. If the FRj is a continuous random variable, then the probability of success in satisfying FRj within the design range can be expressed as follows:

where is the systematic probability density function of FRj and and are the lower and upper bounds, respectively, of the design range.

Definition 6.

The configuration delivery time of each module parameter is another important factor considered by the customer. After submitting an order, the customer wants to obtain the product as soon as possible. Let the time evaluation of the product module parameter be Cij. Then, the product delivery time is

3.3. Model Construction of the MCDA

(1) Model construction of MPP. A comprehensive product performance can be described by three objective values: module cost utility (ratio of engineering cost to acceptable utility; the smaller the better), module information content , and product delivery time (meet the timeliness of service customization; the smaller the better). Then, MPP can be described as a multi-objective model of integer planning as follows:

Joining Equations (1)–(13), the multi-objective model for MPP is constructed as follows:

where and are binary decision variables. The input is a known module instance parameter and the output is a set of module parameter combinations satisfying minimum cost utility, information content, and delivery time. The combinatorial optimization problem (Equations (14)–(17)) is an NP problem that can be solved with the help of a heuristic algorithm. The three-dimensional solution set distribution is obtained based on the NSGA-II and MOPSO algorithm [34].

(2) Model construction of SMC. To obtain SMC, the Pareto solution set of MPP under each objective function pair (a two-objective optimization function) is computed to obtain different module combination schemes Qi (i = 1, 2, 3) as follows:

The values of SMC are calculated according to the obtained MPP scheme. The manufacturer provides service modules, such as technical consulting, equipment maintenance, performance monitoring, fault diagnosis, part replacement, and recycling services (expressed by service statistics ), which are subject to different MPP schemes. According to the obtained with target values of MPP, SMC can be customized based on . The configuration relationship f between the combination scheme and the service module can be obtained through the weighted integration of the scheme service evaluation matrix. The more a configuration scheme is associated with a service module, the more it satisfies the personalization requirements of customers. Then, the scheme of SMC within the MCDA can be constructed as follows:

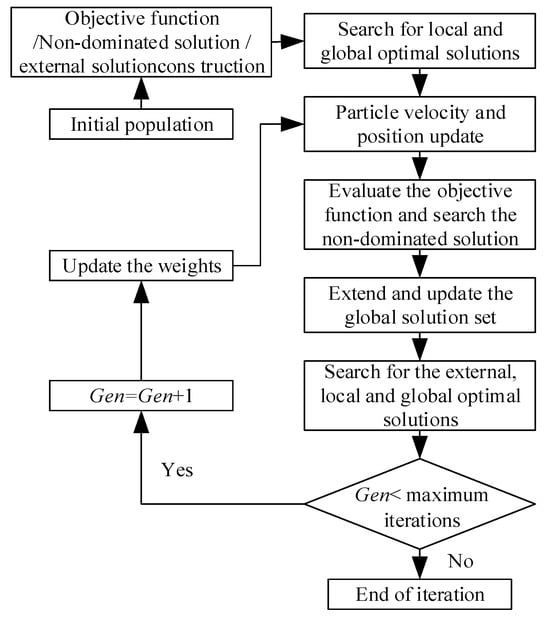

3.4. Problem-Solving Procedures of the Proposed MCDA

The problem-solving procedures of the proposed MCDA are shown in Figure 3, and the detailed steps are described as follows.

Figure 3.

The problem-solving procedures of the proposed MCDA.

Step 1: Obtain CRs based on the order data of the enterprise and obtain weights of FRs based on FQFD.

Step 2: Construct a multi-objective model of MPP based on the information content, delivery time, and cost utility of module and product and obtain the Pareto solution set under each objective function pair.

Step 3: The NSGA-II is selected to obtain the Pareto solution sets of the MPP schemes. And then, SMC is presented based on the configuration relationship between the combination scheme MPP and the service modules with different customer usage scenarios.

Step 4: Compare and analyze the results of the case study based on the proposed MCDA framework.

4. Case Study

4.1. Background Illustration and FR Calculation

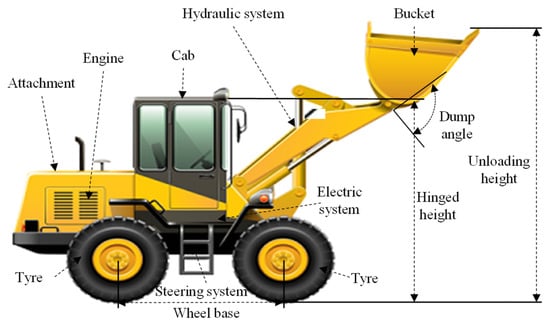

A mechanical company located in Xiamen specializes in the integration of design and development, manufacturing, and sales services, with a focus on CEPS such as cranes, excavators, and loaders. To meet the diverse requirements of its customers, the company aims to implement personalized customization designs for its product family of wheel loaders, which constitutes a significant aspect of product redesign. The wheel loader (as depicted in Figure 4) features a modular system structure composed of front, rear, and middle components, each containing several functional module layers. Only a selection of representative software functions and hardware functions, as well as service modules, are included as case studies. Table 1 provides descriptions of the selected modules and parameters associated with the wheel loader.

Figure 4.

Modular system structure of a wheel loader.

Table 1.

List of module instances and module parameters for a wheel loader.

The descriptions of CRs and FRs are presented in Table 2, based on the customer order data and the enterprise’s product database. The CRs were subjected to statistical analysis utilizing the Kano model, resulting in integrated weights of CRs as follows: 0.14, 0.16, 0.15, 0.12, 0.13, 0.13, 0.08, and 0.09. These weights were subsequently mapped to the FRs using FQFD in conjunction with triangular fuzzy numbers to establish the range of design parameters. The weights of the FRs were computed using Equation (1), and the resulting data are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Description of CRs and FRs.

Table 3.

Mapping the relationship and weights of FRs.

4.2. Calculation of Parameter Values

Utilizing the customer orders and the module utility weights from the company’s database, the cost utility for each module parameter corresponding to the FRs was computed using Equation (2). The results of this analysis are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

The cost utility of module parameters.

Based on the data from the production department and the associated costs of manufacturing, assembly, and engineering within the company, the costs for the modules are calculated using Equation (4). The results of these calculations are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Engineering cost of module parameters (CNY/min).

In accordance with the design range of FRs presented in Table 2, the company’s designers established the system range for module parameters based on customer orders. The results of this determination are illustrated in Table 6.

Table 6.

The system range of module parameters.

Since the FRs are random and fuzzy variables, the probability of information content Pij for the module parameters under each FR can be calculated according to Equations (6)–(8), as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Probability of information content for module parameters.

4.3. Calculation of the MCDA Based on the NSGA-II

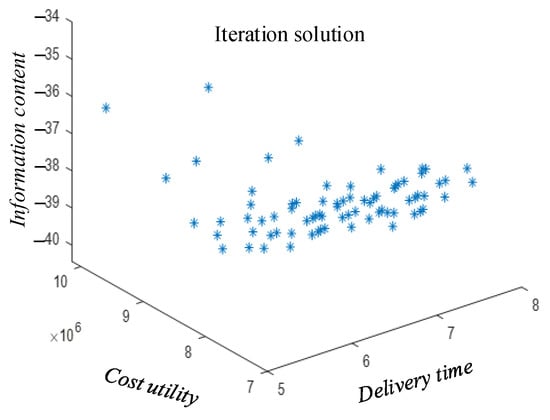

The NSGA-II with an elite strategy is selected for the coding process; the workflow is illustrated in Figure 5. The parameters of the NSGA-II were configured with a population size, solution set size, the maximum iterations set to 100, a crossover probability of 0.8, and a mutation probability of 0.3. We selected three of the most representative and coupled core parameters of the NSGA-II: maximum number of iterations, crossover rate, and mutation rate. Each parameter was set at three levels, forming an L9(34) orthogonal array. Using Taguchi orthogonal experimental design, the hypervolume (HV) indicator, which can simultaneously characterize population convergence, diversity, and distribution, was used as the response variable. The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) and mean were used as evaluation indicators [46]. Through nine sets of orthogonal experiments, we analyzed the impact of parameters on algorithm performance. Finally, the optimal parameter combination for the NSGA-II was determined as (maximum number of iterations, crossover probability, mutation probability) = (100, 0.8, 0.3) (as shown in Figure 6). Based on the data presented in Table 6 and Table 7, as well as Equations (10)–(17), the solution set of MPP obtained through MATLAB 2022a is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 5.

Workflow of the NSGA-II.

Figure 6.

Parameter settings of the NSGA-II.

Figure 7.

Iteration solution of MPP based on the NSGA-II.

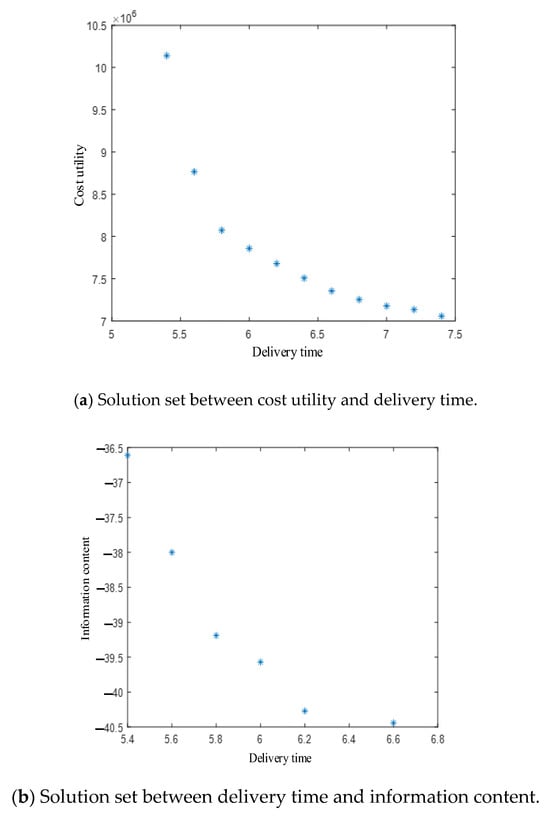

As illustrated in Figure 7, a total of 75 feasible solutions corresponding to the module parameter value are identified across the three objective functions, necessitating further selection to satisfy the specified SMC. This abundance of alternatives underscores a core principle of multi-objective optimization: there exists no single best solution, but rather a set of compelling trade-offs, from which a final choice must be made according to higher-level priorities. To identify the Pareto solution set Qi under different objective functions, a two-objective optimization function was constructed based on Equation (18); the results are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Pareto solution set under each objective function pair.

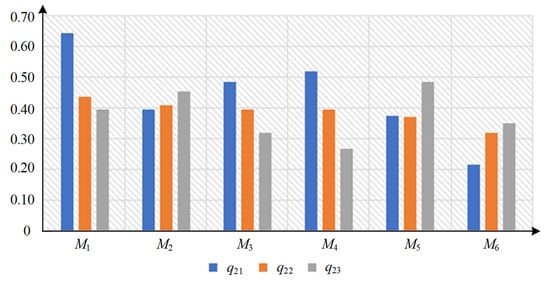

For clarity, only the three MPP schemes located at the extremes and the midpoint of the obtained target solution set are presented for SMC analysis. These specific schemes were selected to represent the spectrum of design priorities. One extreme prioritizes one objective, the other extreme prioritizes the competing objective, and the midpoint offers a balanced compromise between them. The corresponding results are detailed in Table 8.

Table 8.

The extremes and the midpoint of the Pareto solution set.

In combination with Definition 2, individualized modules were configured from the service statistics matrix based on the obtained MPP schemes in Table 8. Q1 was evaluated under the criteria of delivery time and cost utility, wherein five decision-makers were invited to perform a five-point scaling (0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9) of service statistics for SMC across six service criteria. represents technical consulting, equipment maintenance, performance monitoring, fault diagnosis, parts replacement, and recycling services. The scheme service evaluation matrix of Q1 is presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Scheme service evaluation matrix of Q1.

Here, each decision-maker was assigned a weight of 0.2. The decision matrix for SMC was derived by integrating the geometric weighting operators corresponding to the weights as outlined in Equation (19). The decision matrix for SMC is presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Decision matrix

From Table 10, the first scheme of SMC q11 under the objective function of delivery time and cost utility focuses on the service modules, which are ranked as recycling services > performance monitoring > technical consultation > fault diagnosis > equipment maintenance > part replacement. Since q11 has the largest cost utility (delivery time has the smallest), the hope is not to add additional costs for part replacement and equipment maintenance. For recycling services and performance monitoring, there is a focus on the cost to receive benefit returns. The software and hardware configuration modules of q11 are as follows: 2.2 m3 bucket capacity, variable hydraulic configuration, 3 t load, 2800 mm unloading height, Shangchai brand engine, 175 kW rated power, 7470 mm outer bucket radius, 6650 mm inner wheel radius, low smart system, and Delta tires. Hence, q11 has low intelligence and does not have a good human–machine interaction function. It, therefore, needs performance monitoring and technical consulting. Accordingly, the comparison of decision values between (q11, q12, and q13) is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Comparison of decision values between .

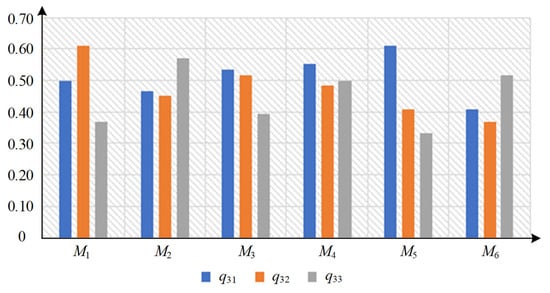

Similarly, the decision matrix under the delivery time and information content function is shown in Table 11, and the decision matrix under information content and cost utility function is shown in Table 12. And, the comparison of decision values between is shown in Figure 10, and the comparison between is shown in Figure 11.

Table 11.

Decision matrix .

Table 12.

Decision matrix

Figure 10.

Comparison of decision values between

Figure 11.

Comparison of decision values between

4.4. Method Comparison and Result Analysis

The MOPSO algorithm [34] (as illustrated in Figure 12) was employed to encode the proposed MPP model. To validate the stability of the results obtained from the MCDA, the parameters for the MOPSO algorithm were configured as follows [46]: population and solution set sizes were set to 100, the maximum number of iterations was limited to 50, individual and global learning coefficients were both set to 1, and the maximum transfer speed weight was established at 0.8. And, the solution set of MPP based on the MOPSO algorithm is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Flowchart of the MOPSO algorithm.

Figure 13.

Solution set of MPP based on the MOPSO algorithm.

There were 24 feasible solutions corresponding to the parameter value of the module across the three objective functions; further selection was necessary to identify a configuration scheme that aligns with CRs. This necessity stems from the inherent trade-offs in multi-objective optimization, where no single solution can simultaneously optimize all conflicting goals, thus requiring a decision-making process to select the most preferable compromise. Two-objective optimization functions were developed based on Figure 13 to identify the Pareto optimal solution set Qi under each objective function pair. For the purpose of clarity, only the extremes and the midpoint of each objective solution set are presented, with the results summarized in Table 13. These representative schemes effectively capture the spectrum of design philosophies. One extreme prioritizes one objective (e.g., minimal delivery time), the other extreme prioritizes the competing objective (e.g., minimal cost utility), and the midpoint offers a balanced compromise between the two. The decision values indicate that the objective function values and combination schemes obtained from the two algorithms are largely consistent (with the exception of q11), suggesting that the constructed model and schemes of the proposed MCDA are both stable and effective. This convergence in results, despite the different search mechanisms of the NSGA-II and MOPSO, indicates that the identified Pareto front is a robust property of the underlying problem formulation rather than an artifact of a specific algorithm. The minor discrepancy in q11 highlights the presence of near-optimal solutions in the search space, which different algorithms may approximate slightly differently, without undermining the overall validity of the model.

Table 13.

Solution set based on the MOPSO algorithm.

The robustness of the MCDA corresponding to the combination scheme was analyzed. Since the evaluation values of the service modules focused on the combination scheme are mainly provided by decision-makers, whose weights in the process of decision matrix integration directly affect the final configuration results, the changes of the service modules can be observed by the changes of the decision-maker weights. To reduce the number of weight perturbations, the weight change range of each decision-maker was [0.1, 0.3]. The scheme of SMC perturbation results , , and after six uniform perturbations are shown in Table 14. The comparison results between , , and after perturbation is shown in Figure 14. The observed stability in the SMC rankings under weight perturbations underscores the robustness of the proposed decision-making mechanism within the MCDA framework.

Table 14.

Weight perturbation and the decision matrix of , , and

Figure 14.

Comparison results between , , and

The results of the ranking for , , and indicate that the values of the SMC under the objective function Qi vary with the weights assigned by decision-makers. This variation is expected, as different weight assignments naturally alter the aggregated evaluation scores. However, the ranking order exhibits a tendency towards stability. This stability suggests a strong inherent correlation between the optimal module configuration derived from MPP and its most suitable service modules, which is not easily overturned by minor changes in subjective judgment. This observation underscores the robustness of the results obtained from the proposed MCDA framework.

5. Conclusions

This study proposes an MCDA framework, which investigates CR information and product operational data to address the module configuration problem for CEPS. The research has successfully addressed the three questions posed at the outset (1) by developing a heterogeneous data-driven framework that integrates MPP and SMC; (2) by formulating and solving a multi-objective MPP model; and (3) by establishing a linkage mechanism for personalized service customization. In the proposed MCDA, an MPP model was constructed considering cost utility, information content, and delivery time, followed by the SMC model to meet the customization design for a wheel loader. The principal contributions of this research are summarized as follows.

(1) The FQFD was employed to map CRs to FRs and to establish the design range of modules based on CR data. The weights of the FRs were determined using triangular fuzzy numbers. A multi-objective model of MPP was developed, incorporating the cost utility, information content, and delivery time based on product operational data.

(2) The NSGA-II and MOPSO algorithms were utilized to derive the Pareto solution sets for the MPP schemes, and then the SMC scheme was formulated for the customization design. The application and analysis of CEPS demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed MCDA framework.

A case study on the configuration design of a wheel loader illustrated the efficacy of the proposed MCDA framework, which has been successfully implemented in a corporate project. Nevertheless, the CR information, cost utility, information content, and delivery time of the module and product often exhibit imprecision when establishing the MPP problem, and the identification of SMC still lacks robust supporting tools and theoretical foundations. This study has certain limitations that point to future research directions. It is acknowledged that the framework’s validation is primarily based on a case study of a wheel loader, and the comparative analysis of multi-objective algorithms could be expanded beyond the NSGA-II and MOPSO to further generalize the findings. Future work will focus on analyzing and mining heterogeneous data related to CR information and product operations data to identify potential FRs based on usage scenarios, facilitating the redesign and optimization of key functional components of CEPS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. (Xiaozhen Lian) and D.S.; methodology, X.L. (Xiaozhen Lian); software, X.L. (Xinyi Luo); validation, X.L. (Xiaozhen Lian) and D.S.; formal analysis, X.L. (Xiaozhen Lian) and D.S.; investigation, X.L. (Xiaozhen Lian); resources, X.L. (Xiaozhen Lian); data curation, X.L. (Xinyi Luo); writing—original draft preparation, X.L. (Xiaozhen Lian); writing—review and editing, X.L. (Xiaozhen Lian) and D.S.; visualization, X.L. (Xiaozhen Lian) and D.S.; supervision, X.L. (Xiaozhen Lian) and D.S.; project administration, D.S.; funding acquisition, X.L. (Xiaozhen Lian). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Young and Middle-aged Teacher Education Research Project of Fujian Province, China (grant No. JAT231050), and the Youth Top Talents Class A Research Launch Fundation of Jimei University, China (grant No. CX248115).

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors express sincere appreciation to the anonymous referees for their helpful comments that helped improve the quality of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, Y.; Chu, X.; Chen, D.; Liu, Q.; Shen, J. An integrated module portfolio planning approach for complex products and systems. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2015, 28, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Jin, G.; Matsukawa, H. Product platform configuration decision in NPD with uncertain demands and module options. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 6336–6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sheng, G.J.; Chen, L.C.; Li, J. An innovative model of personalized product service system (PPSS) for open community collaborative supply (OCCS): Selection, configuration, and optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 436, 140639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Chu, X.; Wang, W.; Xue, D. A directed failure causality network (DFCN) based method for function components risk prioritization under interval type-2 fuzzy environment. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2019, 41, 100920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, R.; Luo, J.; Malmqvist, J.; Summers, J. New design: Opportunities for engineering design in an era of digital transformation. J. Eng. Des. 2022, 33, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H. Modeling and simulation technical risk diffusion in the complex product research and development projects. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 2019, 39, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Zhang, S.; Fu, S.; Liu, Y. FD-LLM: Large language model for fault diagnosis of complex equipment. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, X.; Zou, F. Identification of influential function modules within complex products and systems based on weighted and directed complex networks. J. Intell. Manuf. 2019, 30, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakkanen, J.; Juuti, T.; Lehtonen, T.; Mämmelä, J. Why to design modular products? Procedia CIRP 2022, 109, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhong, P.; Liu, H.; Jia, W.; Sa, G.; Tan, J. Module partition for complex products based on stable overlapping community detection and overlapping component allocation. Res. Eng. Des. 2024, 35, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Li, F.; Xue, J.; Zhang, L. A TRIZ-inspired knowledge-driven approach for user-centric smart product-service system: A case study on intelligent test tube rack design. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 56, 101901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Chakrabortty, R.K.; Elsawah, S.; Ryan, M.J. Modelling and application of hierarchical joint optimisation for modular product family and supply chain architecture. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 947–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer, J.; Braun, S.; Cheng, C.-T.; Dowey, S.; Wollert, J. A human factors-aware assistance system in manufacturing based on gamification and hardware modularisation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 7760–7775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Jiao, R.J. Data-informed inverse design by product usage information: A review, framework and outlook. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 529–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gericke, K.; Eckert, C.; Campean, F.; Clarkson, P.J.; Flening, E.; Isaksson, O.; Kipouros, T.; Kokkolaras, M.; Köhler, C.; Panarotto, M.; et al. Supporting designers: Moving from method menagerie to method ecosystem. Des. Sci. 2020, 6, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbeck, L.; Kovaleva, D.; Manny, A.; Stieler, D.; Rettinger, M.; Renz, R.; Tošić, Z.; Teschemacher, T.; Stindt, J.; Forman, P.; et al. Modularisation Strategies for Individualised Precast Construction—Conceptual Fundamentals and Research Directions. Designs 2023, 7, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yang, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Shi, J.; Zhang, K. Design for product resilience: Concept, characteristics and generalisation. J. Eng. Des. 2023, 34, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. A Heuristic Genetic Algorithm for Product Portfolio Planning. Comput. Oper. Res. 2007, 34, 1777–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Ren, M.; Xiang, Z.; Zheng, P.; Cong, J.; Chen, C.-H. A novel smart product-service system configuration method for mass personalization based on knowledge graph. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avikal, R. QFD and Fuzzy Kano model based approach for classification of aesthetic attributes of SUV car profile. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Chen, C. Customer requirement management in product development: A review of research issues. Concurr. Eng. 2006, 14, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshreshtha, K.; Sharma, G.; Bajpai, N. Conjoint analysis: The assumptions, applications, concerns, remedies and future research direction. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2023, 40, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Xu, X.; Yu, S.; Liu, C. Personalized product configuration framework in an adaptable open architecture product platform. J. Manuf. Syst. 2017, 43, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Sheng, G.; Lu, X.; Ming, X. An innovation service system and personalized recommendation for customer-product interaction life cycle in smart product service system. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 398, 136470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.C.; Huang, J.H.; Gupta, S.; Akman, G. Developing a personalized recommendation system in a smart product service system based on unsupervised learning model. Comput. Ind. 2021, 128, 103421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Jiao, R.J.; Chen, L.; Wu, C. Green modular design for material efficiency: A leader-follower joint optimization model. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 41, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.S.; Peng, W.P.; Yan, W. Analysis of inclusion relation of parameterized models for product platforms. China Mech. Eng. 2017, 28, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Design of customer demand products based on Kano and artificial immune system. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 24, 2536–2546. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Qiu, H.; Wan, L.; Wang, H. Coupling analysis of product family design based on axiomatic design and modular incidence matrix. China Mech. Eng. 2019, 30, 794–803. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Chu, X.; Xue, D.; Chen, D. Identification of to-be-improved components for redesign of complex products and systems based on fuzzy QFD and FMEA. J. Intell. Manuf. 2019, 30, 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.Y.; Wu, L. Analysis of user demand side response behavior of regional integrated power and gas energy systems based on evolutionary game. Proc. CSEE 2020, 40, 3775–3785. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ming, X.; Chu, X. Multi-stakeholder’s sustainable requirement analysis for smart manufacturing systems based on the stakeholder value network approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 177, 109043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvillo, L.; Díaz, O. Requirement-driven evolution in software product lines: A systematic mapping study. J. Syst. Softw. 2016, 122, 110–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Hou, L.; Fang, Y.; Lin, H.; Guo, T.; Jiao, J. Optimization design of wheel loader gearbox considering product operational big data. J. Mech. Eng. 2018, 54, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, R.; Opabola, E.A. Simulating operational disruption in petrochemical facilities under natural hazard impact. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 265, 111481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Z. Modularization for the complex product considering the design change requirements. Res. Eng. Des. 2021, 32, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Wang, H.L.; Mu, R.; Huang, W.; Ling, W.G.; Lai, R.Y. Research on the evolution & innovation for modular product family. J. Mech. Eng. 2012, 48, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chu, X.; Chu, D.; Liu, Q. An integrated module partition approach for complex products and systems based on weighted complex networks. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 4608–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Du, G. Leader-follower joint optimization of product family configuration with consideration of remanufacturing. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 24, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Li, H.; Gu, F.; Ding, N.; Gu, X.; Luo, G. Multidisciplinary collaborative design modeling technologies for complex mechanical products based on digital twin. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2019, 25, 1307–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Macherki, D.; Diallo, T.M.L.; Choley, J.-Y.; Barkallah, M.; Haddar, M. Self-reconfiguration of manufacturing systems using Satisfiability Modulo Theory. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, R.S.; Lin, W.G.; Wu, Y.M. Redesign priority identification of product family modules for green performance optimization. China Mech. Eng. 2019, 30, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Forti, W.; Ramos, C.; Muniz, J. Integration of design structure matrix and modular function deployment for mass customization and product modularization: A case study on heavy vehicles. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 125, 1987–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, J.; Qin, J. Research on modularized design and parameter matching of dual-fuel pre-cooler for chemically precooled engine. Fuel 2025, 381, 133201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Chu, X.; Li, Y. An integrated approach to identify function components for product redesign based on analysis of customer requirements and failure risk. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 36, 1743–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, X.; Jin, Y. PlatEMO: A MATLAB platform for evolutionary multi-objective optimization. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2017, 12, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).