Abstract

In this study, we consider the Lorentzian rotation about a lightlike axis. First, we introduce a geometric characterization for the rotation angle between two vectors that can overlap each other under a Lorentzian rotation about a lightlike axis. Then, we give a definition for the angle measurement between two spacelike vectors whose vector product is lightlike. Later, we generalize the Lorentzian rotation about a lightlike axis, and determine matrices of these transformations using the Cartan frame and the well-known Rodrigues formula, then using the Cayley map, and finally using the generalized split quaternions. We see that such transformations give parabolic rotational motions on general cones or general hyperboloids of one or two sheets, while they also give linear rotational motions on general hyperboloids of one sheet.

Keywords:

Lorentzian scalar product; generalized Lorentzian rotation matrix; Cartan’s frame; Rodrigues rotation formula; Cayley map; split quaternion MSC:

15A63; 15A66; 53A17; 53A35; 53B30; 70B05; 70B10; 70E17

1. Introduction

As a ubiquitous phenomenon, Euclidean rotational motions serve as a bridge between theoretical abstraction and practical applications. They are linear transformations that can be expressed by the orthogonal matrices whose determinants are 1, forming a non-Abelian group denoted by SO(3). Rotation matrices have attracted the attention of many researchers, as they play an important role in many application areas in many fields such as robotics [1,2], and differential geometry [3]. Some well-known methods to obtain rotation matrices are the Rodrigues formula, the Cayley map, and quaternion multiplication.

Rotation transformations and their matrices can be defined for other scalar product spaces, and these new rotation transformations can create new fields of study. One of those spaces is the Minkowski 3-space [4,5,6], which is a geometric framework that is used to study the structure of spacetime in special relativity. Rotation transformations of Minkowski 3-space are a crucial component of the three-dimensional Lorentz group, and their mathematical properties and the simplified physical scenarios they govern make them a valuable tool for theoretical physicists and mathematicians to explore fundamental concepts in relativity, quantum mechanics, and field theory. On the other hand, rotation transformations of the Minkowski spacetime finds diverse applications, including analyzing lens optics or laser cavity kinematics [7], deriving robot manipulator equations of motion [8], facilitating motion interpolations [9], and modeling ideal fluid hydrodynamics [10]. There are many studies on generating or generalizing the rotation matrices of the Minkowski 3-space, which have spacelike, timelike, or lightlike axes of rotation [11,12,13,14]. The rotation matrices of the generalized Minkowski 3-space that have spacelike or timelike axes are given in [15,16]. However, the rotation matrices that have generalized lightlike axes are not given yet.

The main aim of our study is to give generalized Lorentzian rotation matrices with generalized lightlike axes, which provide parabolic motions on general cones or hyperboloids of one or two sheets, while they also give linear motions on hyperboloids of one sheet, using the well-known classical methods of the Rodrigues formula, the Cayley map, and quaternion multiplication. Here, we have established that the generalized Lorentz rotation formulas are identical to the standard Lorentz rotation formulas, with the exception of skew-symmetric matrices. In addition, we consider the angle of a Lorentzian rotation about a lightlike axis in the Minkowski 3-space, and we introduce a geometric characterization for it, using the region swept by the rotated vector as in the classical geometries. Moreover, we provide a definition not found in the literature for measuring the angle between two spacelike vectors whose vector product is lightlike. We also adapt this characterization to the generalized Minkowski 3-space.

This paper is organized as follows: First, we give a brief introduction to the generalized Minkowski 3-space and the related number system. Then, we consider the Lorentzian rotation about a lightlike axis, and introduce the geometric meaning for the rotation angles, giving a definition of angle between two spacelike vectors on the same pseudosphere, whose vector product is lightlike. Finally, we generate the generalized Lorentzian rotation matrices which determine parabolic and linear rotational motions in the space, using the Rodrigues formula, the Cayley map, and the generalized split quaternion methods in the generalized Minkowski 3-space.

2. Preliminaries

The generalized Minkowski 3-space derived by the standard Minkowski 3-space of signature , and its associated number system , which is the generalized split quaternion, were introduced in [15]. Accordingly, is the real vector space with the three-dimensional generalized Lorentzian scalar product or -scalar product defined by a real symmetric matrix

with a negative determinant whose eigenvalues are not all of the same sign, which can be written as

for vectors , , while the standard Lorentzian scalar product is

where . The matrix is the associated matrix of the bilinear form, and

is called the constant of the matrix . A nonzero vector is called -spacelike, -timelike and -lightlike (or -null), if “ or ”, , and “ and ”, respectively. The -norm of the vector is given by

For , spheres of the generalized Minkowski 3-space or -spheres with a center at the origin and radius r are the sets

which is called an -pseudosphere, which is a general hyperboloid of one sheet and an -hyperbolic sphere which is a general hyperboloid of two sheets. In addition, the -sphere with its center at the origin and radius 0 is

which is called -light cone, which is a general cone.

A matrix S is defined as -skew-symmetric if it satisfies the equation , and for a given vector , the -skew-symmetric matrix related to the vector has the form of

where , , and , , , , and . Using this notion, the generalized Lorentzian vector product of vectors is given as follows:

In addition, for vectors , the following equation is satisfied:

The -measure of the angle between linearly independent -spacelike vectors and is defined as follows [16]:

- (i)

- If is -spacelike and , which are equivalent to , then

- (ii)

- If is -timelike, which is equivalent to , then

On the other hand, for the real numbers A, B, C, D, E, F which are the entries of the matrix , and for the base elements satisfying the following equalities

each element of the set

is called a generalized split quaternion or an -split quaternion. The set with its sum and multiplication operations is a non-commutative, non-division, and associative ring. For an -split quaternion , the real number and the vector are called the scalar part and the vector part of , respectively. A pure -split quaternion is defined as an -split quaternion with a zero scalar part. So, the vectors of can be thought of as pure -split quaternions. For any two -split quaternions and , the multiplication of them is given by

Then for two pure -split quaternions and , the following equation is satisfied:

In addition, left and right multiplications of -split quaternions can be computed as follows:

For an -split quaternion , the conjugate, norm and inverse of are defined as follows:

If then is called a unit -split quaternion. Generalized split quaternions, like ordinary split quaternions, can be classified as follows: an -split quaternion is called spacelike, timelike and lightlike (or null), if and , respectively.

3. On the Lorentzian Rotation About a Lightlike Axis

In [17], Sodsiri, using an elementary approach, determined the rotation matrices in the Minkowski 3-space about the lightlike axis by the angle , as

for each . It is easy to see that for each value of n, a different Lorentzian rotation matrix is obtained, which fixes the axis ℓ′ pointwise. Then, using the vectorial representation of the spherical rotations, the rotation about a general lightlike axis ℓ spanned by a lightlike vector as a geodesic was given as

for the unit vector , in [18]. Later, Nešović determined the rotation matrix R about a general axis ℓ spanned by a lightlike vector by the angle using Cartan’s frame [19].

Cartan’s frame in is a pseudo-orthonormal frame satisfying the following conditions:

In this frame, is on the pseudosphere with radius 1, and linearly independent lightlike vectors and are always on different naps of the light cone, since two lightlike linearly independent vectors lie in the same nap of the light cone if and only if their Lorentzian scalar product is less than 0 [20]. In addition, the frame is positively oriented, since the frame conditions give the result det. In particular, if and for real numbers and t in Cartan’s frame , then it is possible to see with some calculations that

Hence, using the matrix (21) and the frame coordinates or using Equation (22), one can easily see the equation

which determines the angle of the Lorentzian rotation matrix . On the other hand, the most general form of this frame can be written as where , for the following Euclidean rotation about the x-axis by the angle

which is also a Lorentzian rotation, and is the Lorentzian rotation about the general lightlike axis ℓ spanned by the lightlike vector , since the multiplication of two Lorentzian rotations is also a Lorentzian rotation and

In addition, since the Lorentzian rotations preserve the Lorentzian scalar product, one gets

So, the rotation angle of is also .

Using this fact, Nešović determined the rotation matrix R about the axis ℓ spanned by the lightlike vector by the angle as

where

which is the semi-skew-symmetric matrix with respect to . However, in these studies, the rotation angle has no geometric meaning. In the next section, we introduce a geometric meaning for this value, and this meaning gives a new definition for the angle between two spacelike vectors on the same pseudosphere in , whose vector product is lightlike.

4. Geometric Meaning of the Angle for Rotations About a Lightlike Axis

In this section, we introduce a geometric characterization of the rotation angle between two linearly independent vectors on the same three-dimensional Lorentzian sphere, such that one of the vectors is rotated on to the other one by the Lorentzian rotation matrix (28) about the lightlike axis with direction vector by the angle . Since all structure is invariant under the transformation , we only consider the vector where . Notice that for two different linear dependent different lightlike vectors and , the Lorentzian rotation matrices about the axis ℓ with direction vector or by the angle are different. So, the representation may be a cause of confusion. To avoid this confusion, is a more suitable representation than for the rotation transformation, and is a more suitable representation than ℓ for the rotation axis. For this reason, from now on, we only use the notation for the Lorentzian rotation around the axis by the angle . But one can also prefer to call it the Lorentzian rotation about the axis ℓ with respect to the vector , by the angle .

It is known that any nonzero vector and are in the same casual character, and the endpoint of the rotated vector is on the plane which passes through the endpoint of and Lorentzian orthogonal to . So, the trajectory of the motion of the endpoint of the vector under the rotation is either a line or a parabola since the intersection of the Lorentzian sphere and the plane is either two parallel lines or a parabola. More clearly, the trajectory is a parabola when the endpoint of is on a hyperbolic sphere or a light cone, while the trajectory is either a line or a parabola when the endpoint is on a pseudosphere; in particular, the trajectory is a line when the endpoint of is on the plane which passes through the origin and Lorentzian orthogonal to , and the trajectory is a parabola when the endpoint of is not on the plane .

Let be any nonzero vector linearly independent from . Then, either the vector lies in the plane or it does not; in other words, either , or .

(1) First, let lie in the plane . In this case, is a spacelike vector that can be written in general form as , and its endpoint is on the Lorentz space circle , which consists of a pair of parallel lines. Then, one can see that

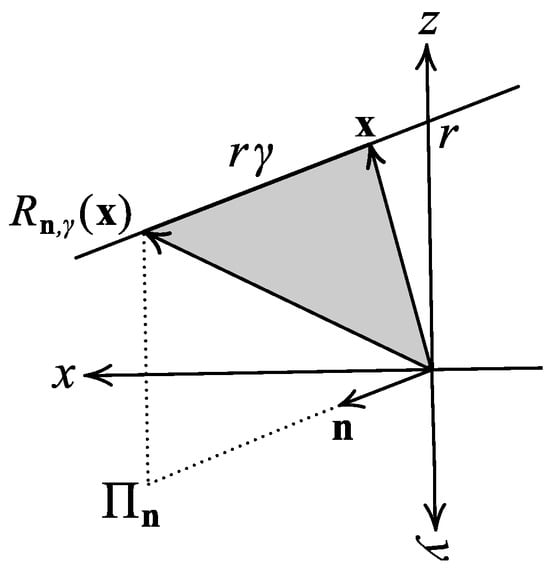

and so the rotation occurs in the plane , which is a tangent to the light cone along the line with direction vector . Moreover, if , then the directed area of the vector swept under the rotation is (see Figure 1). Therefore, in accordance with the classical geometries, the measurement of the directed angle of the rotation with the axis form to corresponds to the directed area . In addition, if , then the corresponding area increases -fold. Consequently, for two given vectors and such that where , the directed angle of the rotation can be computed by

where S is equal to the directed area of the triangle determined by the vectors and .

Figure 1.

Area of the region swept by under , where and .

Notice that, since the Lorentzian vector product of and is in the same direction as in this case, one can define the angle between them by the angle of the rotation with the standard lightlike axis , which transforms to , as follows

Clearly, this definition completes the angle definition between spacelike vectors given in the preliminary section.

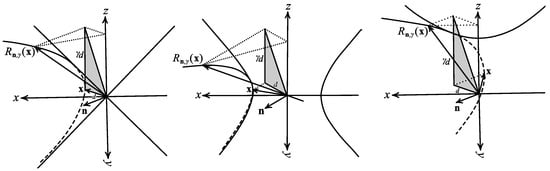

(2) For the other cases, let us consider a nonzero vector which does not lie in the plane . In this case, can be a spacelike, timelike or lightlike vector, and the rotation occurs in the plane , which is parallel to . Then, one can see that the plane can be written in general form as for a nonzero real number d, such that is equal to the Euclidean distance from the origin to the plane . So, can be written in general form as for . Using the matrix of the Lorentzian rotation (21) about the axis with by the angle , one finds that the difference of the third component of the coordinates of and is . In addition, the Euclidean length of the Euclidean orthogonal projection of the vector to the plane , which passes through the origin and Euclidean orthogonal to , is . Therefore, when completes its movement under the transformation , the area of the Euclidean orthogonal projection of the triangle scanned by onto the plane Euclidean orthogonal to is (see Figure 2). Therefore, in accordance with the classical geometries again, the measurement of the directed angle of the rotation with the axis from to corresponds to the directed area , where , acting like a radius, is the Euclidean distance from the origin to the plane . In addition, if , then the corresponding area and the difference of the third components increases -fold. Consequently, for two given vectors and such that , the directed angle can be computed by

where S is equal to the directed area of the Euclidean orthogonal projection of the triangle defined by vectors and onto the plane . Notice that in this case, the rotation angle from to cannot be equal to the angle between them, since their Lorentzian vector product cannot be in the same direction as .

Figure 2.

Area of the Euclidean orthogonal projection of the region swept by under , where and .

Example 1.

Let us take two spacelike vectors and whose Lorentzian vector product is lightlike. Then one can obtain the angle between and as

where is the area of the triangle determined by the vectors and . One can check that for the Lorentzian rotation about the axis by the angle ,

Notice that the trajectory in this example is a line. In addition to this example, the measurement of the angle of the rotation about another lightlike axis from to can be computed as

It is easy to check that

Example 2.

Let us take a timelike vector to rotate by the Lorentzian rotation about the lightlike axis by the angle . Then the rotation matrix can be found as

and we get

One can verify the rotation angle γ by the formula as

where is the Euclidean distance from the origin to the plane , and S is equal to the area of the Euclidean orthogonal projection of the triangle defined by vectors and onto the plane which passes through the origin and Euclidean orthogonal to . Notice that the trajectory in this case is a parabola.

5. -Rotation About an -Lightlike Axis

It is known that any given general hyperboloid of one or two sheets or general cones, which are -spheres, can be transformed to their standard forms, which are Lorentzian spheres, by an affine transformation. So, if and are the quadratic forms associated with the Lorentzian and -scalar products, respectively, and A is a linear transformation that transforms the -spheres to the standard Lorentz spheres, then

for every vector , and one gets

and

Therefore, the geometric structure of the -space is the same as the standard Lorentzian space . In other words, orthogonality, parallelism, and tangency are preserved.

For example, if is -lightlike vector, then the plane which passes through the origin and -orthogonal to is the tangent plane to the -light cone along the line with direction vector ; the intersection of the plane with the -pseudo spheres is two parallel lines. Likewise, Cartan’s -frame is a -pseudo-orthonormal positively oriented frame formed by linearly independent -lightlike vectors and which are on the -light cone, and a unit -spacelike vector which is on the -pseudosphere with radius 1, satisfying the following conditions:

A real matrix O is -orthogonal if and only if , and the set of all -orthogonal matrices whose determinants are equal to 1 gives the generalized Lorentzian group consists of all -rotation matrices of . For any vector , if R is an -rotation matrix, the endpoint of is on the plane which passes through the endpoint of and -orthogonal to , since

So, as in the standard Lorentzian case, the trajectory of motion of the endpoint of a vector under -rotation is either a line or a parabola since the intersection of the -Lorentzian spheres and such a plane whose -normal is -lightlike vector is either two parallel lines or a parabola. If R is an -rotation matrix, then one of the eigenvalues of R is 1, and the eigenvector corresponding to 1 determines the axis of rotation. In addition, in analogy with the standard Lorentzian geometry, if is an -rotation matrix about the axis , we define the angle as the -measurement of the rotation angle if

is satisfied for Cartan’s -frame , and denoted as with the angle by .

However, the geometric meaning of -measurement of the angle slightly changes, since one needs to use the generalization of the Euclidean norm by the same linear transformation A in the corresponding angle formula. One can obtain that

for

which gives the generalization of the Euclidean norm with respect to the linear transformation A. So, for two given vectors and such that where is an -rotation matrix about the axis by the angle , the directed angle can be computed by the formula

if in which can only be an -spacelike vector in the plane , and by the formula

if in which can be any vector not in the plane , where is the -distance from the origin to the plane , and is the directed -area of the -orthogonal projection of the triangle defined by vectors and onto the plane .

Here, one can derive the matrix A using the Euclidean orthogonal diagonalization of the matrix as follows: Let P be the Euclidean-normalized orthogonal matrix with the first column determined by the negative eigenvalue of the matrix , which has one negative and two positive eigenvalues. And let D be the diagonal matrix determined by the eigenvalues corresponding to the columns of P. Then we have or . If then gives the linear transformation A, since

In the next sections, we determine the matrix of -rotation about an -lightlike axis, and the rotation angle of a given -rotation matrix, using the Rodrigues and Cayley methods and -split quaternions, by the following five theorems. These theorems are actually well-known results for the standard Minkowski 3-space. We just use the -scalar product in the proofs instead of the standard Lorentzian scalar product, and we see that the generalized Lorentz rotation formulas are identical to the standard Lorentzian rotation formulas with the exception of skew-symmetric matrices.

6. -Rotation Formula by the Rodrigues Formula

Here, we determine the matrix of the -rotation around an -lightlike vector by an angle , using the Rodrigues formula and Cartan’s -frame. Note that the characteristic polynomial of is

and so one gets

for the -lightlike vector .

Theorem 1.

Let us take an -lightlike vector , and angle . Then, for the -skew-symmetric matrix , the matrix exponential function

is the matrix of the -rotation about the vector by the angle γ. In addition, can be written as follows:

where , , , and .

Proof.

Let for a nonzero vector . The vector can be written in Cartan’s -frame as where . Using the linearity, we get

The vectors and can also be written in Cartan’s -frame as

where . Then considering Cartan’s -frame conditions, one gets

In addition, since we have

we get and . In addition, one can obtain the followings:

Then, it follows that

and so we get

Moreover, since we have that

we get

and so have

Differentiating this equation for the variable , we get

On the other hand, considering again Cartan’s -frame conditions, we derive that

and we obtain

Integrating this equation, we get

and

By using the Taylor power series expansion of and (see [21,22] for the exponential of semi-skew matrices), we obtain the Rodrigues rotation formula as

Substituting the matrix (8) into this equation, one derives the matrix (47). One can see that the determinant of the matrix (47) is 1. In addition, using the -skew-symmetric matrix property, one gets the -orthogonality of as follows:

Thus, is the -rotation matrix about the -lightlike axis by the angle . Notice that the matrix (47) has eigenvalues . □

If R is an -rotation matrix whose axis and angle are unknown, then while its axis can be determined by the eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue 1, its angle can be found by the following theorem.

Theorem 2.

Let R be an -rotation matrix. If is the axis of the -rotation R, then the angle γ can be computed by the formula

Proof.

Example 3.

Given a general cone, two general hyperboloids with the equations

which are the -light cone, the -hyperbolic sphere, and the -pseudosphere with centers at the origin, for the matrix

respectively. Let us consider an -lightlike vector . Using the Equation (47), one can calculate for the angle as follows:

Consider an -lightlike vector , -timelike vector , and two -spacelike vectors and such that , and rotate them about the vector by the angle 4. One can derive the following results:

Under the -rotation about , the trajectories of the endpoints of are parabolas on the planes passing through the endpoint of and -orthogonal to the vector , which are the intersection of the -light cone with the plane , the -hyperbolic sphere with the plane , and the -pseudosphere with the plane , respectively. In addition, since is on the plane , the trajectory of the endpoint of is a line which is a part of the intersection of the -pseudosphere and . Using the matrix determined by the positive affine transformation A and , we can check the angle γ from Formula (31). For the matrix , one can obtain that

where

Then one derives that

where , and get

One can check for and that

where , and

7. -Rotation Formula by the Cayley Map

For the -skew-symmetric matrix (8) where is an -lightlike vector, one can derive by lengthy calculations that the determinant of is equal to 1. So, is an invertible matrix, and the well-known Cayley map can be given as

Then, it is not difficult to see that

using the fact that . Hence, one can obtain that

In addition, since we have , we get that . Thus, is an -rotation matrix since it is -orthogonal and its determinant is equal to 1. By the following theorem, the -rotation matrix about the -lightlike axis by the angle can be obtained using the Cayley map:

Theorem 3.

Let be an -lightlike vector, and . For the -skew-symmetric matrix , the matrix

gives the -rotation about the axis by the angle γ, that is .

Proof.

Clearly, for all , is an -skew-symmetric matrix. Therefore

is the matrix of an -rotation. If , multiplying it by on the right, then one gets

In addition, by Formula (46), one has

So,

This equation implies that

which results in . Substituting this value into , one obtains

□

Since one has

one can express Equation (52) as

It is obvious that it is well defined for , since we have

by Theorem 2. For a given -rotation matrix R, if the rotation axis is , then one can also find the rotation angle with the help of the following theorem instead of Theorem 2.

Theorem 4.

Let R be an -rotation matrix. If is the axis of the -rotation R, then the angle γ can be computed by the formula

Proof.

By Theorem 3, we have

for the -rotation matrix R. Considering the inverse of the Cayley function (54), we get

□

Example 4.

Let us take a general cone with the equation

which is the -light cone for

Let us consider an -lightlike vector as . The -skew-symmetric matrix with respect to is

Thus, one can obtain the -rotation matrix for the -lightlike axis and the angle γ as follows:

This matrix can be checked by the Rodrigues Formula (47) as follows:

Example 5.

Consider an -rotation matrix

where

Let us find the axis and the angle of the -rotation. The form of eigenvectors of R associated with the eigenvalue of 1 is for , which are -lightlike vectors. If , then the -skew-symmetric matrix corresponding to is derived as

Then, using Equation (48) or (56), one can obtain the angle as . We can verify that the matrix of the -rotation for in the previous example gives the matrix R.

8. -Rotation Formula by the -Split Quaternions

Like the ordinary split quaternions, -split quaternions can be used to produce -rotations in . In this section, we use the -split quaternions with their multiplication in the to generate an -rotation matrix about an -lightlike axis . One can see that for every -lightlike vector , is a unit timelike -split quaternion. For a unit timelike -split quaternion , the -rotation operator can be defined as

where is a pure -split quaternion which can be considered a vector to be rotated. The following theorem shows that this operator -rotates about the -lightlike axis by the angle :

Theorem 5.

For a unit timelike -split quaternion

where is a -lightlike vector and , and for any pure -split quaternion , the transformation

gives an -rotation about the -lightlike axis by the angle γ.

Proof.

Example 6.

Given a -lightlike vector for

Let us -rotate the vector about the vector by the angle . Using the unit timelike -split quaternion

one obtains the -rotation operator

considering the vector as a pure -split quaternion. Then, using the -split quaternion multiplication, we get

which can be considered as the rotated vector . One can easily check this result using Theorem 1, to generate the -rotation matrix with the axis and the angle , as

9. Conclusions

In this study, we gave a geometric characterization with the notion of the area for the angle of Lorentzian rotations about a lightlike axis, and we gave a definition not found in the literature for the angle measurement between two spacelike vectors whose vector product is lightlike, in the Minkowski 3-space. Then, we established the affine relation between the standard and generalized Minkowski 3-spaces, and we generalized the Lorentzian rotations about a lightlike axis, determining them in the generalized Minkowski 3-space with the angle measurement characterized similarly, using the well-known Rodrigues and Cayley maps, and the generalized split quaternions. We showed that the generalized Lorentzian rotations about a generalized lightlike axis give parabolic and linear rotational motions on general hyperboloids of one or two sheets or cones, and their formulas are identical to the standard Lorentz rotation formulas with the exception of skew-symmetric matrices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.B.Ç.; investigation, H.B.Ç., M.D. and A.Y.C.; methodology, M.D. and H.B.Ç.; validation, H.B.Ç., M.D. and A.Y.C.; formal analysis, M.D. and H.B.Ç.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D. and H.B.Ç.; writing—review and editing, M.D. and H.B.Ç.; supervision, H.B.Ç. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous referees for their helpful suggestions and comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xie, G.; Yang, H.; Deng, H.; Shi, Z.; Chen, G. Formal verification of robot rotary kinematics. Electronics 2023, 12, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Ju, H.; Yang, Y.; Xu, H. An improved unit quaternion for attitude alignment and inverse kinematic solution of the robot arm wrist. Machines 2023, 11, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Çalışkan, A. Quaternionic shape operator and rotation matrix on ruled surfaces. Axioms 2023, 12, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.W. Semi-Riemannian Geometry with Applications to Relativity; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, J.G. Foundations of Hyperbolic Manifolds; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- López, R. Differential geometry of curves and surfaces in Lorentz-Minkowski space. Int. J. Geom. 2014, 7, 44–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başkal, S. Wigner rotations and Little groups. Acta Phys. Hung. A Heavy Ion Phys. 2004, 19, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, F.C.; Bobrow, J.E.; Ploen, S.R. A Lie group formulation of robot dynamics. Int. J. Robot. 1995, 14, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadami, R.; Rahebi, J.; Yaylı, Y. Fast methods for spherical Linear interpolation in Minkowski space. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebr. 2015, 25, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, V. On the differential geometry of infinite dimensional Lie groups and its applications to the hydrodynamics of perfect fluids. Ann. L’Institut Fourier 1966, 16, 319–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğdu, M.; Özdemir, M. On reflections and rotations in Minkowski 3-space of physical phenomena. J. Geom. Symmetry Phys. 2015, 39, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, M.; Ergin, A.A. Rotations with unit timelike quaternions in Minkowski 3-space. J. Geom. Symmetry Phys. 2006, 56, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkaldı, S.; Gündoğan, H. Cayley formula, Euler parameters and rotations in 3-dimensional Lorentzian space. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebr. 2010, 20, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, H.; Özdemir, M. Rotations on a lightcone in Minkowski 3-space. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebr. 2017, 27, 2841–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duru, M.; Çolakoğlu, H.B. Generalized split quaternions and their applications on non-parabolic conical rotations. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çolakoğlu, H.B.; Duru, M. Elliptic and hyperbolic rotational motions on general hyperboloids. Symmetry 2025, 17, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodsiri, W. Lorentzian motions in Minkowski 3-space. KKU Sci. J. 2006, 34, 242–249. [Google Scholar]

- Korolko, L.; Leite, F.S. Kinematics for rolling a Lorentzian sphere. In Proceedings of the 2011 50th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control and European Control Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 12–15 December 2011; pp. 6522–6527. [Google Scholar]

- Nešović, E. On rotation about lightlike axis in three-dimensional Minkowski space. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebr. 2016, 26, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoguchi, J.I.; Lee, S. Null curves in Minkowski 3-space. Int. Electron. J. Geom. 2008, 1, 40–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gallier, J.; Xu, D. Computing exponetials of skew symmetric matrices and logarithms of orthogonal matrices. Int. J. Robot. Autom. 2003, 18, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kula, L.; Karacan, M.K.; Yaylı, Y. Formulas for the exponential of semi symmetric matrix of order 4. Math. Comput. Appl. 2005, 10, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).