Abstract

Let denote a commutative ring with unity and denote a collection of all annihilating ideals from . An annihilator intersection graph of is represented by the notation . This graph is not directed in nature, where the vertex set is represented by . There is a connection in the form of an edge between two distinct vertices and in iff . In this work, we begin by categorizing commutative rings , which are finite in structure, so that forms a star graph/2-outerplanar graph, and we identify the inner vertex number of . In addition, a classification of the finite rings where the genus of is 2, meaning is a double-toroidal graph, is also investigated. Further, we determine , having a crosscap 1 of indicating that is a projective plane. Finally, we examine the domination number for the annihilator intersection graph and demonstrate that it is at maximum, two.

Keywords:

planar graph; zero-divisor graph; genus of a graph; annihilating-ideal graph; annihilating intersection graph MSC:

05C25; 05C10; 13A15

1. Introduction

Algebra, combinatorics and discrete mathematics are three crucial branches of mathematical sciences. These branches frequently intersect, using techniques from one to the other. The first occurrence of forming a group from a graph resulted from studying the automorphic groups of graphs. This led to the essential question of identifying classes of groups that can be represented as automorphic groups of graphs. Conversely, this research involves creating graphs from groups. The earliest example of this was given in 1878 for the formation of graphs with finite groups due to Arthur Cayley, known as pictorial representation for a class of groups. Today, Cayley graphs are important discrete structures in parallel computing and they are applied in routing problems to resolve and correct any type of error that appears.

In classical algebra, the notable construction involves graphs that are derived from rings with finite or infinite characteristics. Investigating graphs originating from rings enhances the relationship between structural properties of rings with their corresponding graph structures. The present research starts with the extensively studied zero-divisor graphs of commutative rings. The concept of a graph, which is represented by and is associated with a set of zero-divisor elements of a commutative ring , was initially defined by Beck [1] in 1988. The author explored the colors of these graphs. Beck hypothesized that the clique number and the chromatic number are not different for the graph However, Anderson and Naseer [2], in 1993, refuted Beck’s hypothesis by presenting a counterexample. In 1999, Anderson and Livingston [3] not only coined the term zero-divisor graph but also revised Beck’s definition. They interlinked the relationship between the structural properties of commutative rings and the corresponding theoretic properties of the graphs due to a set of zero-divisor elements. Beck’s initial definition of a zero-divisor graph includes all elements of as vertices of , while in , a set of vertices consists of all zero-divisor elements of .

In the theory of rings, the structural properties are often more closed to the behavior of associated ideals rather individual elements of rings. Ideals gives structural details that might be missed when focusing solely on elements, making it logical to introduce a graph with its corresponding ideals as all of its vertex. Then, Behboodi and Rakeei [4,5] introduced a different graph that would come prior to it and named it the annihilating-ideal graph on , whose vertices belong to the set of nonzero annihilating ideals of instead of those in the previously known zero-divisor graphs. This makes annihilating-ideal graphs of rings a valuable tool to study certain features of properties of rings with commutativity, particularly structures based on associated ideals of the ring.

In a related development, Vafaei et al. [6] introduced a class of ideal-based graphs that are undirected over a ring and named these graphs based on the annihilator intersection of , which is denoted by the symbol . This graph has as its vertex set, and there is connection in form of an edge between two distinct vertices and in iff .

In [7], Rehman et al. characterized finite commutative rings that have the annihilator intersection graph as either a unicycle, a tree, an outerplanar graph, or a split graph. They also classified isomorphic properties of , whose graph based on the annihilator intersection is either a toroidal or a planar graph. Minimal non-outerplanar graphs are discussed in [8]. Algebraic graphs are not only studied in classical structures but in logical algebras and lattice theory as well, e.g., Moin et al. [9] investigated a graph associated with UP-algebras that is a class of logical algebras.

This article begins with the classification of the finite commutative rings to determine whether is a star graph or a 2-outerplanar graph, and we determine the inner vertex number of . We also identify the class of finite rings to determine that the genus of is 2, meaning that is a double-toroidal graph. In addition, we determine the class of finite rings to determine that the crosscap of is 1, indicating that is a projective plane. Finally, we examine the domination number of the annihilator intersection graph and prove that it is at maximum, two.

The set is a collection of vertices V and edges E in such a way that its edges are undirected. The structure formed by the collection of edges and vertices is simple; it is called a graph. A graph has a number of classes. Among the classes of graphs, we denote a complete graph by the notation , in which every pair of distinct vertices is connected by an edge. In an r-partite graph, the set of vertices are partitioned into r subsets, ensuring that there is no connection between vertices within the same partition. Specifically, a complete r-partite graph has vertices connected to all vertices not in the same subset. is another special class of r-partite graph that is from the family of 2-partite graph, whose part sizes are m and n, where each vertex from one part is connected to every vertex in the opposite part. A dominating set S of is a subset of such that every vertex in has at least one neighbor in S. is the domination number of by the size of the smallest dominating set in . In [10], the smallest k in a complete graph, such that G is k-outerplanar, is determined.

Mohar and Thomassen [11] introduced the concept of graphs on surfaces. Let represent a sphere with k handles for indicating the surface of genus oriented to k. represents the genus of graph , which is the least positive integer n so that can be embedded in . Visually, a graph is considered embedded in a surface if it can be depicted on that surface such that its edges only intersect at their common vertices. A planar graph is a class of graphs whose genus is while a toroidal graph is another class of graphs with genus A graph with genus 2 is called a double-toroidal graph. In addition, it is important to note that indicates that H is a subgraph of . The genus of a graph is given in more detail in [7,12]. For other terminologies based on graph theoretic concepts, the reader may refer to [13].

Throughout this research, commutative rings are considered those that have a unit element 1 other than For , denotes the collection of ideals of and . An ideal of is called an annihilator ideal if ∃ is an ideal of . For , the annihilator of is defined as . Let represent the collection of annihilator ideals where . The sets of minimal prime ideals, nilpotent elements, zero-divisors, and unity of are denoted correspondingly by , , and . More details with different notations and other terminologies for the ring theoretic concept can be found in [14].

2. Basic Properties of

This section comprises the characterization of to determine that is a ring graph, star graph, or a 2-outerplanar graph. In addition, we determine the inner vertex number of for a finite commutative ring.

The subsequent observations of [6] are frequently utilized throughout this paper.

Lemma 1

([6]). Let Λ be a commutative ring, where . Consequently, the subsequent statements are valid:

- 1.

- If ∉, then .

- 2.

- If ∈, then ∈.

- 3.

- If ∉, then there exists a vertex such that forms a path in .

Lemma 2

([6]). Let Λ be a non-reduced ring. Then, every nilpotent ideal of Λ other than zero is connected with every other vertex in . Specifically, the subgraph or subpart formed with nilpotent ideals is a complete subgraph or subpart of .

Theorem 1

([7]). Let Λ be a local commutative ring. Then, generates a complete graph.

In the subsequent ring, we investigate the class of finite commutative rings to determine that forms a star graph.

Theorem 2.

The structure turns to a star graph in a finite commutative ring Λ iff either Λ is a local ring having a maximum of two different ideals other than zero or , where and are fields.

Proof.

First, consider whether is a star graph. Now, it is known that is non-infinite, , where is a local ring for each i and . Assume . Consider , , and . Since for each , forms a cycle in , this contradicts the fact. Hence, .

Case (1) Suppose and . Consider , , and . Since for each , forms a cycle in , it is contradictory. Therefore, is a field. In similar fashion, is a field.

Case (2) Suppose , i.e., is a local ring. Using Theorem 1, graph is complete. Since is a star graph, .

Conversely, if is a local ring with , then or Using Theorem 1, if , where and are fields, then . This confirms that it is a star graph. □

The results for a planar graph established by Rehman et al. [7] are presented as follows:

Theorem 3

([7]). The structure is a planar graph in the finite commutative ring Λ iff any one subsequent below is satisfied:

- 1.

- Λ is a local ring with maximum 4 non-trivial ideals.

- 2.

- , where and are fields.

- 3.

- , where Υ is a field, is a local ring, and ϰ is a unique non-trivial ideal of .

Theorem 4

([7]). The structure in a finite commutative ring Λ is an outerplanar graph iff either Λ is local with or , where and are fields.

Consider the graph . A chord in is an edge that connects two non-adjacent vertices within a cycle of . A cycle C in is called primitive if there are no chords in it. A graph is said to have the primitive cycle property (PCP) if any two primitive cycles share a maximum of one edge. The notation stands for a free rank of , and it is the number of primitive cycles in . The cycle rank of , denoted by , is given by , where k indicates the number of connected components of . The cycle rank is also known as the dimension of the cycle space of . Due to [15], . A graph is referred as a ring graph, meeting any one subsequent equivalent assertions [15]:

- ;

- satisfies the PCP without having a subdivision of as a subpart.

We are now ready to identify the class of rings to determine that is a ring graph.

Theorem 5.

The structure is a ring graph in the finite commutative ring Λ iff any one of the following assertions is met:

- 1.

- Λ is a local ring with a maximum of 3 non-trivial ideals.

- 2.

- , where and are fields.

Proof.

Since all ring graphs are planar, we only need to verify the rings listed in Theorem 3 to determine if they form ring graphs. If is a local ring with or 2, or if , where and are fields, then using Theorem 1, or . In such cases, , making a ring graph.

If is a local ring with , then using Theorem 1, . Here, , so is also a ring graph.

However, if is a local ring with or if , where is a field and is a local ring with as a unique non-trivial ideal of , then using Theorem 1, . In this situation, and , meaning is not a ring graph. □

A planar graph embedding of is called 1-outerplanar if the planar graph itself is outerplanar, which means the collection of vertices are connected to the outer face in the embedding. This idea extends to k-outerplanar embeddings, where, once the vertex set is removed from the outer face corresponding to incident edges, the remaining graph is -outerplanar. We call a graph to be k-outerplanar if it allows for such a k-outerplanar embedding. The outerplanarity index of a graph is the smallest k such that is k-outerplanar. For a planar graph , the inner vertex number is defined as the minimum number of vertices not on the boundary of the exterior face in any plane embedding of . A graph is termed minimally non-outerplanar if equals 1. For additional details on k-outerplanarity, refer to [8,10].

The subsequent observations are crucial for deriving the results in this section.

Theorem 6

([16]). A graph is outerplanar iff it is not contained in a subdivision of or .

In the next result, the classification of the finite rings as a 2-outerplanar graph is given.

Theorem 7.

The structure in the finite commutative ring Λ has an outerplanarity index of 2 iff any of the subsequent conditions is satisfied:

- 1.

- Λ is a local ring with exactly 4 non-trivial ideals.

- 2.

- , where Υ is a field and is a local ring with ϰ as a unique non-trivial ideal of .

Proof.

Suppose that has an outerplanarity index of 2. This means that is a planar graph. Hence, according to Theorem 3, must be any one of the rings identified in Theorem 3.

If is a local ring with or if , where and are fields, then, using Theorem 4, the outerplanarity index of is 1, which is contradictory. Therefore, must be a local ring with or , where is a field and is a local ring with as a unique non-trivial ideal of .

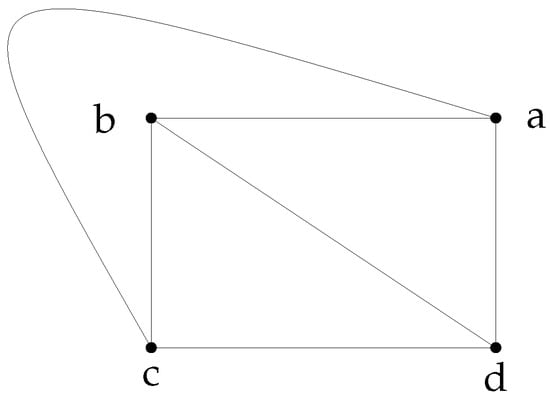

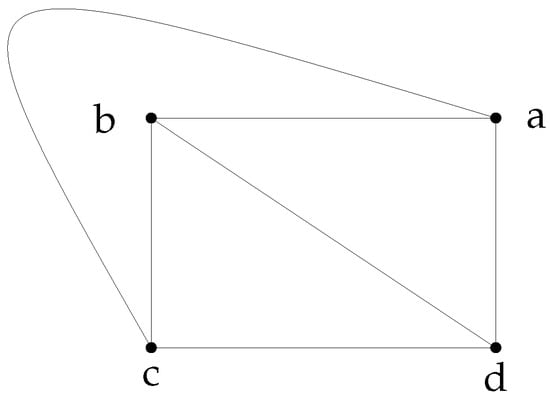

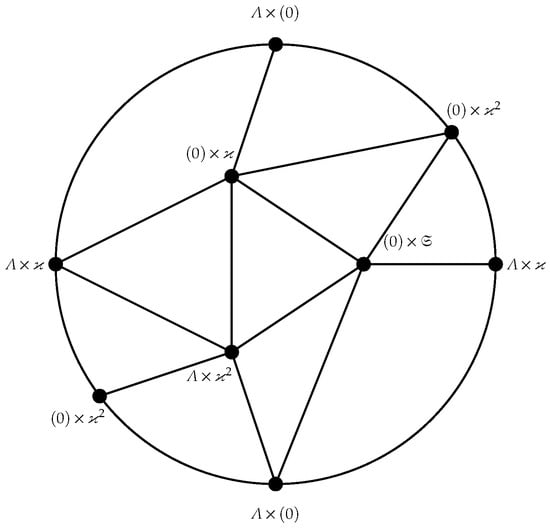

Conversely, if is a local ring with or if , where is a field and is a local ring with as a unique non-trivial ideal of , then . So, using Theorem 6, is not a 1-outerplanar graph. Removing the vertices from the outer face results in a graph that is , which is 1-outerplanar (refer to Figure 1). Therefore, by definition, is 2-outerplanar, establishing 2 as the minimum. Thus, the outerplanarity index of is 2. □

Figure 1.

.

Corollary 1.

The structure in a finite commutative ring Λ has an outerplanarity index of maximum two.

Lastly, we determine the inner vertex number of for the class of finite rings in the subsequent result.

Theorem 8.

The inner vertex number of in a finite commutative ring Λ is given by

Proof.

By using Theorem 4 and Figure 1, the following proof is directly obtained. □

Corollary 2.

The structure is minimally non-outerplanar in a finite commutative ring Λ iff either Λ is a local ring with exactly 4 non-trivial ideals or , where Υ is a field and is a local ring with ϰ as a unique non-trivial ideal of .

3. Genus of

This section comprises the classification of finite rings to determine that is a double-toroidal graph, i.e., .

For a given real number w, let

Lemma 3

([16]). Let . Then,

Specifically, for . In addition, for .

Lemma 4

([16]). Let . Then,

In particular, for and .

In [7], Rehman et al. identify the class of finite rings to determine that is a toroidal graph, as follows:

Theorem 9

([7] (Theorems 4.3, 4.4, 4.5, 4.6)). Let Λ be a finite commutative ring. Then, iff any one ot these subsequent conditions is satisfied:

- 1.

- Λ is a local ring between 5 and 7 non-trivial ideals.

- 2.

- , where , , and are fields.

- 3.

- , where each is a local ring having unique non-trivial ideal for and .

- 4.

- , where Υ is a field and is a local ring with ϰ and as its only non-trivial ideals.

We now determine the finite commutative rings to determine that the annihilator intersection graph is a double-toroidal graph.

Theorem 10.

in a finite commutative ring Λ iff any one of the conditions below is met:

- 1.

- Λ is a local ring with exactly 8 non-trivial ideals.

- 2.

- , where Υ is a field and is a local ring with ϰ, , and as its only non-trivial ideals.

Proof.

Assume that . Since is a finite non-local ring, it can be expressed as , where each is a local ring and . Suppose . Define the subsequent vertices: . Since for every i and j, the graph contains a subgraph isomorphic to , induced by the set . Therefore, by Lemma 3, it follows that , which is contradictory. Consequently, we must have .

Case (1) Assume and . Let us consider the subsequent vertices: , , , , , , , , and , all of which are vertices of .

Since for i and j, has a subgraph induced by the set . Therefore, by Lemma 4, we have , which contradicts. Hence, , meaning that must be a field. By a similar reasoning, it follows that and are also fields. Consequently, according to Theorem 9, , which again contradicts.

Case (2) Suppose , with and . Let such that . Define the subsequent vertices: , , , , , , , , , and .

Since for i and j, has a subgraph induced by the set . Therefore, by Lemma 4, we have , which contradicts. Thus, must be the sole non-trivial ideal of . Similarly, must be a unique non-trivial ideal of . Consequently, using Theorem 9, , which again contradicts. Therefore, any one must be zero; let us assume , implying that is a field.

If were also a field, then using Theorem 3, , which contradicts. Hence, is not a field and has a non-trivial maximal ideal . Let denote the nilpotency index of . Suppose . Consider the subsequent vertices: , , , , , , , , , , and .

Since for i and j, has subgraph induced by the set , which contradicts Lemma 3. Thus, . Based on Theorems 3 and 9, it is evident that and , so .

Let such that , , or . Define the vertices , , , , , , , , and .

Since for each i and j, contains a subgraph induced by the set , which contradicts Lemma 4. Hence, , , and must be unique non-trivial ideals of .

Case (3) Assume , which means is a local ring. According to Theorem 1, is a complete graph. Hence, must have exactly 8 non-trivial ideals by using Lemma 4.

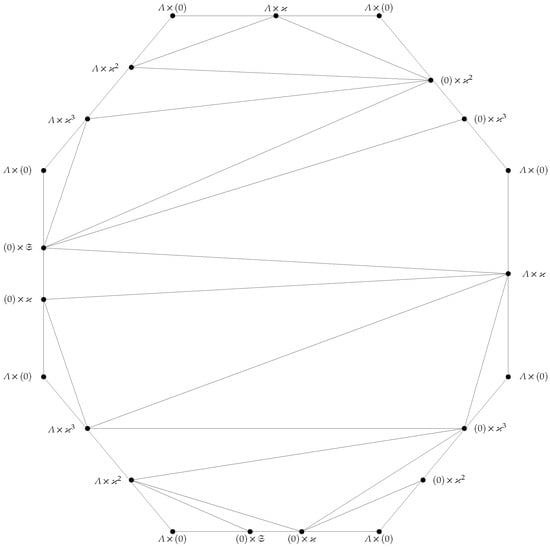

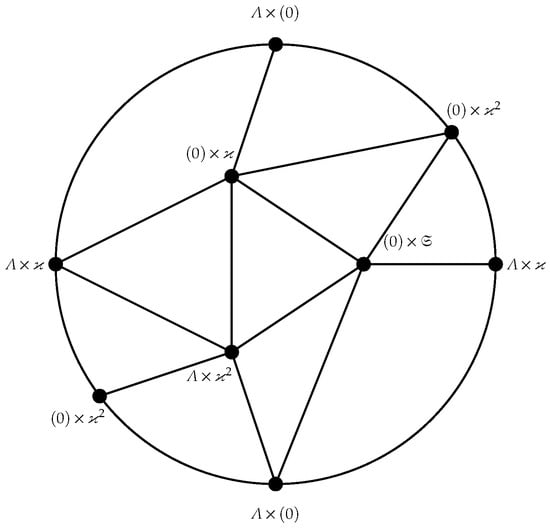

Conversely, if , where is a field and is a local ring with , , and as unique non-trivial ideals of , then the double-toroidal embedding of is illustrated in Figure 2. In addition, if is a local ring having precisely 8 non-trivial ideals, this implies that , using Theorem 1. Thus, applying Lemma 4, we find that . □

Figure 2.

Embedding of on , where is a local ring with , , and as unique non-trivial ideals of .

Example 1.

Let ; then, using Theorem 10, .

4. Crosscap of

This section comprises the identification of the class of rings to determine that the crosscap number of the annihilator intersection graph equals one, i.e., .

For non-negative integers k, denotes a sphere with k crosscaps attached. Any connected compact surface can be topologically represented as for some non-negative integer k. The crosscap number, also referred to as or a nonorientable genus, is the least positive integer k in such a way that H can be embedded in . The projective and Klein bottle graphs correspond to crosscap numbers 1 and 2, respectively. Moreover, if L is a subgraph of H, then .

The subsequent results specify the crosscap numbers for complete graphs and complete bipartite graphs. In this context, the notation .

Lemma 5

([16]). For , we have

Lemma

([16]). For , it holds that

We now proceed to classify finite commutative rings to determine that is a projective plane.

Theorem 11.

in a finite commutative ring Λ iff any one of the subsequent conditions is satisfied:

- 1.

- Λ is a local ring with 5 or 6 non-trivial ideals.

- 2.

- , where each is a field for .

- 3.

- , where Υ is a field and is a local ring with ϰ and as its only non-trivial ideals.

Proof.

Assume . Since is finite, hence , with each is a local ring and . If , consider the vertices , , , , , and . Since for every , the graph has a subgraph isomorphic to induced by the set , which contradicts Lemma 3. Therefore, .

Case (1) Assume and . Let us consider the subsequent vertices: , , , , , , and , all of which are in . Since for each pair , the subgraph induced by in is isomorphic to . By Lemma 5, this implies , which contradicts. Therefore, must be zero, meaning is a field. Similarly, it follows that and must also be fields.

Case (2) Assume , and both and . Let us define the subsequent vertices: , , , , , , and , all of which are in . Since for every pair , the subgraph induced by in is isomorphic to . This leads to a contradiction of Lemma 3, implying that at least one of must be zero. Assume , which means is a field.

If were also a field, then by Lemma 3, would be 0, which is contradictory. Therefore, must not be a field and must have a nonzero maximal ideal . Let denote the nilpotency index of . Suppose . Define the following vertices: , , , , , , and , which are in . Since for each pair , the subgraph induced by in is isomorphic to , which contradicts with Lemma 5. Thus, .

If , then . According to Lemma 5, this would imply , which contradicts it. Consequently, must be 3.

Consider such that and . Define the following vertices: , , , , , , and , all of which are in . Since for every pair , the subgraph induced by the set contains a subgraph isomorphic to in , which contradicts Lemma 5. Therefore, and must be unique non-trivial ideals of .

Case (3) Assume . Using Theorem 1, the graph must be a complete graph. Given that , Lemma 5 implies that must have 5 or 6 non-trivial ideals.

On the other hand, if the number of non-trivial ideals in satisfies , then is either or . By Lemma 5, this confirms that .

Specifically, if , where each is in the form of a field for a selection of , then is isomorphic to . Thus, applying Lemma 5 again, .

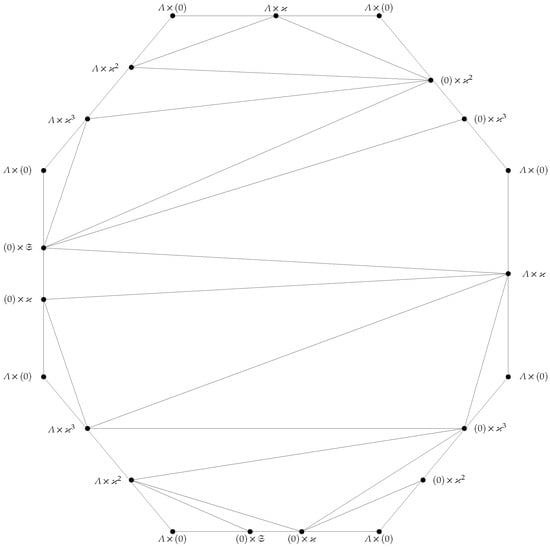

In addition, if , where is a field and is a local ring with and being unique non-trivial ideals of , then the projective embedding of is illustrated in Figure 3. □

Figure 3.

Projective embedding of , where is a local ring with and are unique non-trivial ideals of .

Example 2.

Let ; then, using Theorem 11, .

Example 3.

Let ; then, using Theorem 11, .

5. Domination Number of

This section comprises an exploration of the domination number of the annihilator intersection graph.

Lemma 7.

Let be a commutative ring, where each is an integral domain for and . The subsequent statements are true:

- 1.

- For , the graph is a complete bipartite graph.

- 2.

- For , , where H denotes a multipartite graph and m is a positive integer with .

Proof.

and

.

(1) When , the graph is a complete bipartite graph with the partitions and .

(2) For , let us define the subsequent sets:

It follows that and . We establish the subsequent claims:

Claim(1): The subgraph is a multipartite graph. Let and be two vertices of . Define a relation ∼ on by iff iff for each . It is straightforward to verify that ∼ is an equivalence relation on . The equivalence classes under ∼ are , where with only the ideal being zero for each . Therefore, . Consider two distinct vertices and in . Analyze the subsequent cases:

Case (i): Let for some . In this case, . Given that , it follows that no edge exists between and in . Consequently, no two vertices within are connected in for each .

Case (ii): Suppose and for some . Here, and . Since but , we have . Therefore, forms an edge in . Thus, each vertex in is adjacent to every vertex in for all .

Combining the results from Case (i) and Case (ii), we conclude that is indeed a multipartite subgraph of .

Claim (2): The subgraph is a complete subgraph of . Consider two distinct vertices and in . There exist indices such that the and ideals of are zero, and the and ideals of are zero. Without loss of generality, . Then, , but . Therefore, . This implies that is a complete subgraph of .

Combining Claims (1) and (2), we conclude that , where is a multipartite graph and is a complete graph. □

Theorem 12.

Let be a commutative ring, where each is an integral domain for and . Then, the subsequent statements are true:

- 1.

- If , then .

- 2.

- If , then .

Proof.

(1) For the case , according to Lemma 7(1), we have . If , it follows that . On the other hand, if , then .

(2) For the case , by Lemma 7(2), , where H denotes a multipartite graph with . Hence, . □

Lemma 8

([17] (2.7)). Let Λ be a reduced commutative ring containing a nonzero minimal ideal, then Λ is decomposable.

Lemma 9.

Let be a commutative ring, where each is a commutative ring and . Then, .

Proof.

For , the set of vertices is shown by . We claim that the set is a dominating set in .

Consider any vertex . There exists at least one index such that , implying that there is to that .

If , then , but , hence . Therefore, is an edge in .

If and , then , but , thus . This indicates that forms an edge in .

If and , then there must exist . Here, , but , leading to . Thus, is an edge in .

Combining these observations, we conclude that there is an edge between and in . Therefore, is indeed a dominating set in . Consequently, . □

Theorem 13.

Let Λ be a reduced commutative ring; the domination number of is at most two.

Proof.

If , then using Theorem [6] (thm 2.2), the annihilator intersection graph is isomorphic to , where . Therefore, .

If , then according to Lemma 8, we can decompose as , where and are commutative rings. Without loss of generality, . Applying similar reasoning as before, we find that can be further decomposed into , where each is a commutative ring. By Lemma 9, the set is a dominating set in . Consequently, . □

Corollary 3.

Let Λ be a reduced commutative ring with . Then, the subsequent statements are true:

- 1.

- If , then , where at least one of or is a field.

- 2.

- If , then , where neither nor is a field.

Theorem 14.

Let Λ be a non-reduced commutative ring. Then, .

Proof.

Assume and consider any . By Lemma 2, is connected to every other vertex in . Therefore, . □

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have extensively studied the annihilator intersection graph for a commutative ring with unity. We classify finite commutative rings to that exhibits the structure of a star graph and a 2-outerplanar graph. Furthermore, we have determined the inner vertex number of , enriching our understanding of its structural properties.

Our investigation has led to the identification of finite rings to determine that the genus of is 2, categorizing as a double-toroidal graph. In addition, we have identified the finite rings to determine that the crosscap of is 1, thereby classifying as a projective plane.

Finally, we have explored the domination number of the annihilator intersection graph, establishing that it is at maximum, two. These findings contribute to the broader comprehension of the graphical properties of and its behavior across different classes of commutative rings.

Author Contributions

The idea of the present paper was proposed and improved by A.A.K. and M.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/339/45.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests concerning the publication of this article.

References

- Beck, I. Coloring of commutative rings. J. Algebra 1988, 116, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Naseer, M. Beck’s coloring of a commutative ring. J. Algebra 1993, 159, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.F.; Livingston, P.S. The zero-divisor graph of a commutative ring. J. Algebra 1999, 217, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behboodi, M.; Rakeei, Z. The annihilating-ideal graph of commutative ring I. J. Algebra Appl. 2011, 10, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behboodi, M.; Rakeei, Z. The annihilating-ideal graph of commutative ring II. J. Algebra Appl. 2011, 10, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, M.; Tehranian, A.; Nikandish, R. On the annihilator intersection graph of a commutative ring. Italian J. Pure Appl. Math. 2017, 38, 531–541. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, N.; Nazim, M.; Selvakumar, K. On the genus of annihilator intersection graph of commutative rings. Algebr. Struct. Their Appl. 2024, 11, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kulli, V.R. On minimally nonouterplanar graphs. Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. 1975, 41, 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, M.A.; Haidar, A.; Koam, A.N.A. On a graph associated to UP-algebras. Math. Comput. Appl. 2018, 23, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, K. Determining the smallest k such that G is K-outerplanar. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2007, 4698, 359–370. [Google Scholar]

- Mohar, B.; Thomassen, C. Graphs on Surfaces; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA; London, UK, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, N.; Nazim, M.; Selvakumar, K. On the planarity, genus and crosscap of new extension of zero-divisor graph of commutative rings. AKCE Int. J. Graphs Comb. 2022, 19, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, D.B. Introduction to Graph Theory, 2nd ed.; Prentice-Hall of India: New Delhi, India, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Atiyah, M.F.; Macdonald, I.G. Introduction to Commutative Algebra; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Gitler, I.; Reyes, E.; Villarreal, R.H. Ring graphs and complete intersection toric ideals. Discrete Math. 2010, 310, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.T. Graphs, Groups and Surfaces; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Wisbauer, R. Foundations of Module and Ring Theory; Breach Science Publishers: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).