Abstract

Measures generating classical orthogonal polynomials are determined by Pearson’s equation, whose parameters usually provide the positivity of the measures. The case of general complex parameters (nonstandard) is also of interest; the non-Hermitian orthogonality with respect to (now complex-valued) measures is considered on curves in . Some applications lead to multiple orthogonality with respect to a number of such measures. For a system of r orthogonality measures, the perfectness is an important property: in particular, it implies the uniqueness for the whole family of corresponding multiple orthogonal polynomials and the -term recurrence relations. In this paper, we introduce a unified approach which allows to prove the perfectness of the systems of complex measures satisfying Pearson’s equation with nonstandard parameters. We also study the polynomials satisfying multiple orthogonality relations with respect to a system of discrete measures. The well-studied families of multiple Charlier, Krawtchouk, Meixner and Hahn polynomials correspond to the systems of measures defined by the difference Pearson’s equation with standard real parameters. Using the same approach, we verify the perfectness of such systems for general parameters. For some values of the parameters, discrete measures should be replaced with the continuous measures with non-real supports.

Keywords:

classical orthogonal polynomials; discrete orthogonal polynomials; Pearson’s equation; Rodrigues’s formula; multiple orthogonality; Hermite–Padé polynomials; perfectness; normality of indices; nearest-neighbor recurrence relations MSC:

33C45; 42C05

1. Introduction

Let be the linear space of polynomials with complex coefficients, and let there be linear functionals , . Each of the functionals may be defined by a sequence of its moments , .

Given a (multi-)index , a non-trivial polynomial of degree at most

is called a (type II) multiple orthogonal polynomial if it satisfies the following orthogonality conditions:

These orthogonality conditions reduce to a homogeneous linear algebraic system for the coefficients of , which always has a nontrivial solution.

The polynomials play the role of denominators of the Hermite–Padé approximants for a set of formal power series . That is, the following interpolation conditions at infinity are satisfied:

It is an easy exercise to show that the orthogonality conditions (1) are equivalent to the interpolation conditions (2). The corresponding numerators can be defined as the polynomial parts of power series expansions of at infinity.

On applying a construction of this kind, C. Hermite proved [1] that the number e is transcendental. Some modern applications of multiple orthogonality to number theory can be found in reviews [2,3] and papers [4,5]. Other important applications include random matrices [6], spectral theory [7] and integrable systems [8].

Definition 1.

Normality implies the uniqueness of the rational Hermite–Padé approximants, as well as the uniqueness of the multiple orthogonal polynomials up to multiplication by a nonzero constant.

Definition 2.

The system of functionals is called perfect if all its indices are normal.

The definition of perfect systems was given by K. Mahler in [9]. In the case , the above notions reduce to ordinary orthogonal polynomials with respect to a functional and to the Padé approximants. For , the notion of perfectness reduces to the so-called quasi-definiteness of the functional; see ([10], p. 16).

Consider the particular case of functionals determined by positive continuous weights on an interval E of the real line:

The system of weights is called an AT system if for each any nontrivial linear combination with polynomial coefficients

has at most zeros on E. It is not hard to show [11], that AT-systems are perfect, i.e., that the corresponding systems of linear functionals are perfect. Moreover, the corresponding polynomials have simple zeros in E. These properties are helpful for constructing generalized Gaussian quadratures; see [12,13,14].

Among special functions, an important role is played by classical orthogonal polynomials. They can be written in terms of hypergeometric functions; they admit explicit representations through Rodrigues’s formula and so on. Classification (see [15]) of such polynomials for can rely on differential Pearson’s equation for the orthogonality weight

where and are polynomials such that and . In this way, one obtains classical polynomials named after Hermite, Laguerre and Jacobi; one also obtains the Bessel polynomials orthogonal with respect to a complex measure on a complex curve.

It is also of interest to consider a system of classical weights satisfying Pearson’s equation with the common , but distinct . For standard restrictions on coefficients of and , this is also an AT-system, and the corresponding orthogonal polynomials admit explicit expressions via Rodrigues’s formula. Such systems are classified in [16,17].

Multiple orthogonal polynomials constructed in this manner turn to be closely related to certain problems from the theory of random matrices. In particular, the multiple Hermite polynomials account for probabilistic characteristics of non-intersecting Brownian bridges [18] and eigenvalues of Gaussian unitary ensembles with an external source [19]. The multiple Laguerre polynomials lead to the so-called Wishart ensembles [20]. These polynomials together with the Jacobi–Piñeiro polynomials [21] (i.e., the multiple Jacobi polynomials) are related to interesting problems in percolation theory [22].

Classical weights with nonstandard parameters are also of interest. In this case, the orthogonality with respect to complex measures is considered [23] on complex curves. For , the questions of uniqueness and of the asymptotic behavior of classical orthogonal polynomials with nonstandard parameters were studied in works [24,25,26]. For , the Jacobi–Piñeiro polynomials with nonstandard parameters allowed to construct a counterexample to the Gaudin Bethe Ansatz conjecture; see [27].

In this work, we study the perfectness of systems of weights satisfying differential Pearson’s equation with nonstandard parameters. Note that an analogous question for the multiple Wilson and Jacobi–Piñeiro polynomials was considered in the remarkable paper [28]. Our approach may be seen as a development of the approach of [28]: we rely on raising operators, which allows us to treat the case of difference Pearson’s equations in a similar manner.

On replacing the differential Pearson’s equation with its difference analogue

one arrives at the classification of classical polynomials orthogonal with respect to discrete measures: the Charlier, Meixner, Hahn and Krawtchouk polynomials. These families of polynomials were treated in detail in monograph [29]. Moreover, it is known that, for instance, the Meixner polynomials for some nonstandard values of parameters turn into the Meixner–Pollaczek polynomials whose orthogonality weight is continuous; see [30]. An analogous connection exists [31] between discrete and continuous Hahn polynomials. We revisit this phenomenon in Section 5. Modern applications of discrete orthogonal polynomials may be found in ref. [32].

The classification of discrete multiple orthogonal polynomials (the case ) based upon difference Pearson’s Equation (4) was made in the striking paper [33]. A relation of multiple Charlier polynomials to representations of the Heisenberg–Weyl algebra was found in [34]. There is an expression of the Hermite–Padé approximants for the remainder terms of power series of exponential functions via the multiple Charlier polynomials with nonstandard parameters; see [35]. The multiple Meixner polynomials arise in the description of non-Hermitian oscillator Hamiltonians [36,37]. Applications of the multiple Meixner–Pollaczek polynomials to the six-vertex model were studied in [38]. By applying our unified approach to normality and perfectness, we give a detailed answer for which values of the parameters, the systems of weights defined by difference Pearson’s equation, are perfect.

In ([39], Theorem 23.1.11) (see also [40]), W. Van Assche proved that multiple orthogonal polynomials induced by perfect systems satisfy the so-called nearest-neighbor recurrence relations on the lattice of indices. This leads to applications in discrete integrable systems [41,42] and spectral problems on graphs [43,44]. Asymptotic properties of the recurrence coefficients were investigated in [45]. Our approach allows us to show that already a subset of such recurrent relations may only exist for perfect systems.

2. Results

2.1. Continuous Classical Weights

Consider r analytic nontrivial functions satisfying Pearson’s equation

where and are polynomials such that and , . We consider a system of complex-valued measures supported on curves possessing finite moments of all orders . Each curve here is either closed, or connects zeros of . If , we say that its absent zeros are at infinity. The function is assumed continuous on possibly except for the endpoints.

Define functionals on polynomials via

and consider the corresponding multiple orthogonal polynomials. Observe that the multiplication of by a nonzero constant does not affect the orthogonality conditions (1). It is also clear that times any non-zero constant gives another solution to (1), so the multiple orthogonal polynomials are usually normalized in a certain way: for instance, one can consider the so-called monic polynomials, i.e., those with leading coefficients equal to 1. Due to analyticity of the integrand in (6), the curves may be replaced by any homotopically equivalent curve such that the value of the intergral in (6) remains the same.

2.1.1. One Continuous Weight

Let us briefly review the classical case of one weight, that is . Here, we omit the lower index of the weight and put .

It is well known (see Table 1) that there are four types of nontrivial weights satisfying (5) such that the type of w depends on the degree of the polynomial and multiplicity of its zeros. Here, we list these weights (up to shift and stretch of the independent variable) and the contours for all values of the parameters (including non-standard):

Table 1.

Weights for classical orthogonal polynomials.

- (a’)

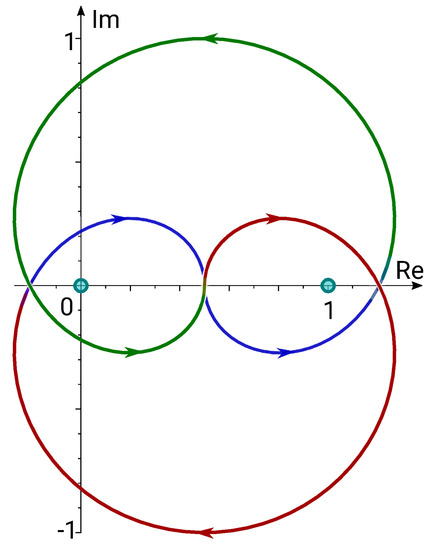

- The Jacobi weight , when has two distinct zeros, and hence . The curve here is a line interval, a circle cut (or not) at one point, or a smooth closed curve sometimes referred to as the Dürer folium, see Figure 1:

Figure 1. The integration curve for the Jacobi weight when . The colors correspond to continuous branches of and : the principal branches are in blue, blue changes to green as passes to another branch, and green changes to red as passes to another branch. Note that is continuous on the whole curve.

Figure 1. The integration curve for the Jacobi weight when . The colors correspond to continuous branches of and : the principal branches are in blue, blue changes to green as passes to another branch, and green changes to red as passes to another branch. Note that is continuous on the whole curve. - (b’)

- The Bessel weight , when has a double zero, so . The curve here is the cardioid . For , one can also take to be the unit circle .

- (c’)

- The Laguerre weight , when , so . Here we take to be either the positive semi-axis, or a parabola encircling it:

- (d’)

- The Hermite weight , when , and hence . Here we put .

Proposition 1.

The weight w is quasi-definite on the curve Γ defined above in the following cases:

- If and only if in the case (a’);

- If and only if in the case (b’);

- If and only if in the case (c’);

- In the case (d’).

Remark 1.

In all cases (a’)–(d’), the corresponding orthogonal polynomial may be found via Rodrigues’s formula:

Here the index is the scalar.

Proposition 1 mostly contains known results: for instance, [24] (Theorem 3.2) derives the quasi-definiteness in the Jacobi case from the uniqueness of the solution of the corresponding matrix Riemann–Hilbert problem. Our Proposition 1 is a particular case of the more general result stated in the next section devoted to multiple orthogonality.

2.1.2. Multiple Continuous Weights

In the general case , possible weights solving the Pearson’s equation in (5) clearly coincide with those listed above in –. Moreover, since all weights share the same polynomial , only combinations of same-type weights are possible. Nevertheless, the contours may (and in some situations must) be different. The details will be clear below.

It is shown in [17] that, for some of the combinations of weights, Rodrigues’s operators (appearing on the right-hand side of (7)) commute, and hence their compositions yield Rodrigues’s formulae, producing the corresponding multiple orthogonal polynomials. The authors of [17] identified combinations (up to a linear transform of the variable and normalization) with commuting Rodrigues’s operators. For , we have the following:

- (a)

- The system of weights on curves defines the Jacobi-Piñeiro polynomials;

- (b)

- The system of weights on curves defines the multiple Bessel polynomials;

- (c)

- The system of weights on curves defines the multiple Laguerre I polynomials;

- (d)

- The system of weights on curves defines the multiple Hermite polynomials;

- (e)

- The system of weights , , on curves defines the multiple Laguerre II polynomials.

Theorem 1.

Let a system of weights on curves be as one of those defined in (a)–(e). This system is perfect if and only if the following hold:

- and in the case (a);

- and in the case (b);

- and in the case (c);

- and in the case (d);

- and , in the case (e)

for all with .

Remark 2.

It is known [17], and we show it in Section 4 that orthogonal polynomials for the systems of weights listed in (a)–(e) may be found through Rodrigues’s formula

where the factors in the products are differential operators.

The Jacobi–Piñeiro case was considered in [28], where the perfectness was deduced from an explicit formula for the determinant defined in (13) below.

2.2. Weights Satisfying Difference Pearson’s Equation

Under and ∇, we understand the forward and backward finite differences, respectively:

Consider r meromorphic in functions satisfying difference Pearson’s equation

where and are polynomials such that and , . Let us note that the solutions of (9) are defined up to a multiplier, which can be an arbitrary meromorphic function with period 1.

We will consider two kinds of functionals. The first kind is defined by a complex measure with discrete support:

where is the Dirac delta function, and . The second kind of functionals is

where stands for some other solution of (9), i.e., , and is a smooth curve in encircling the support of discrete measure so that either it is closed, or both its ends are at infinity. The current section is devoted to multiple orthogonal polynomials with respect to the above functionals.

2.2.1. One Weight

It is well known (see Table 2) that there are four types of nontrivial weights satisfying the difference Pearson’s Equation (4). There are four families of classical discrete orthogonal polynomials, namely the Charlier, Meixner, Krawtchouk and Hahn polynomials. For standard parameters, the Charlier and Meixner weights are supported on an infinite set , while the Krawtchouk and Hahn polynomials are supported on the finite set of integers. These four families can be characterized by a difference version of Rodrigues’s formula.

Table 2.

Weights for classical orthogonal polynomials of discrete variable.

Let us list these weights and integration contours for all (including nonstandard) parameters. We use the notation

for the Pochhammer symbol; for , it reduces to .

- (i’)

- The Hahn weight isand is defined and supported on if . Furthermore,Under the conditionswe consider the curve ending at and separating from .If any of the parameters violates (10), then without loss of generality, it is enough only to consider the case . Indeed, the continuous weight still corresponds to the discrete weight or after relabeling its parameters. For instance, it corresponds to on exchanging and in the case .

- (ii’)

- The Krawtchouk weight isand is defined and supported on if . Let us note that the Krawtchouk weight transforms into the Meixner weight after . So the nonstandard parameters can be found in the next entry (iii’).

- (iii’)

- The Meixner weight isFor the measure is suppoted on . Let and . PutUnless , the curve is defined analogously to the Hahn case, namely it separates from and ends at . For , we can take the curve with the ends at infinity in the closed halfplane where is bounded and still separating from .

- (iv’)

- The Charlier weight iswith the only condition . The discrete measure of orthogonality is supported on .

Proposition 2.

The functional l corresponding to one of the weights described above in (i’)–(iv’) is quasi-definite if and only if

- (i’)

- for the Hahn weight;

- (ii’)

- and for the Krawtchouk weights;

- (iii’)

- and for the Meixner weight;

- (iv’)

- for the Charlier weight.

Given that in the cases (i’) and (ii’), all indices for the corresponding system of orthogonal polynomials are normal if and only if

- , in (i’), and

- in (ii’).

This proposition is a particular case of Theorem 2 from the next section.

2.2.2. Multiple Weights

Analogously to Section 2.1.2, the general case only allows certain combinations of same-type weights solving the difference Pearson’s equation (9), because all weights are supposed to share the same polynomial . Just like in the continuous case, we consider the orthogonality with respect to several functionals , where each is already defined in the previous paragraph. There are several families of multiple orthogonal polynomials corresponding to the system and retaining Rodrigues’s formula: the multiple Charlier, multiple Meixner I and II, multiple Krawtchouk and multiple Hahn polynomials (see [33]).

The multiple Charlier polynomials correspond to and . The multiple Hahn polynomials correspond to ; for non-integer values of N we arrive at the multiple continuous Hahn polynomials. The multiple Krawtchouk polynomials correspond to . In fact, for non-integer values of N, they can be reduced to the multiple Meixner polynomials.

The most involved cases are the multiple Meixner polynomials. Indeed, the weights for the Meixner I polynomials for transform to the Krawtchouk weights for . If , then we have discrete orthogonality on . If , then we introduce a change of variable , cf. ([10], p. 177, Equation (3.6)). If and , then we need to consider the Meixner–Pollaczek polynomials, cf. ([10], p. 180, Equations (3.17), (3.21), and (3.22)). Similarly, one or several weights for the multiple Meixner II polynomials with transform to the Krawtchouk weights. Furthermore, depending on , one can consider discrete or continuous orthogonality. We treat the Meixner weights in more detail in Section 5.1.

Theorem 2.

The systems of functionals generating multiple orthogonal polynomials are perfect if and only if

- (i)

- , as well as as for the multiple Hahn weights;

- (ii)

- , and as for the multiple Krawtchouk weights;

- (iii)

- and , as well as as for the multiple Meixner I weights;

- (iv)

- and as for the multiple Charlier weights;

- (v)

- and , in addition to as for the multiple Meixner II weights.

Given that in the cases (i) and (ii), all indices for the corresponding system of orthogonal polynomials are normal if and only if

- , simultaneously with as in (i), and

- together with as in (ii).

Remark 3.

In the last theorem, in the cases (i) and (ii) with , only the indices satisfying may be normal: indeed, the polynomial of degree is orthogonal to monomials of all non-negative integer degrees. An analogous remark may be applied to the case (iii) when and to the case (v) when and .

Analogously to the continuous case, we show that the difference Rodrigues’s formula (25) given below produces the orthogonal polynomials under the conditions of Theorem 2. Up to normalization, this formula coincides with Rodrigues’s formula obtained in [33] for standard values of the parameters.

2.3. Nearest-Neighbor Recurrence and Perfectness

It is known that, if and are normal indices, then the monic multiple orthogonal polynomials satisfy the so-called nearest neighbor recurrence relations:

where when , and

and a similar representation for uses type-I multiple polynomials; see ([39], Theorem 23.1.11) and [40] for the details. The converse (in a sense) to this assertion is presented by the following fact, whose proof given below uses methods similar to those of Theorem 1.

Proposition 3.

For every , let there be some polynomial of degree satisfying the orthogonality conditions (1), such that

holds for some and some complex numbers and , where we put as . Then this system of functionals is perfect if and only if for the values of are nonzero whenever , as well as for with .

3. Basic Theory

We introduce a notation for all nontrivial polynomials of satisfying (1). Clearly, is a linear space of positive dimension. Let us now review some basic facts related to normality and perfectness.

We say that a matrix A is a Hankel matrix if its entries on each antidiagonal are equal, that is, if it can be written as . Given an index and —the moments of functionals , put

so that is a determinant of order containing r rectangular Hankel blocks of sizes . It turns out that the condition is necessary and sufficient for the normality of ; see Lemma 1 below.

Lemma 1

(see, for example, ([39], §23.1) or [11]). Let be linear functionals . Then the normality of an index is equivalent to , where is the determinant defined in (13).

Proof.

Observe that for a polynomial , the orthogonality conditions (1) may be written as

and for , this linear system has a unique solution. So, the orthogonal polynomial in this case is defined uniquely up to multiplication by a nonzero constant, and hence is normal. On fixing , Cramer’s rule yields

At the same time, for , the orthogonality conditions (1) can be satisfied by a polynomial of degree strictly less than , namely, by for any nontrivial solution of the homogeneous system

Therefore, the index in this case is not normal. □

Remark 4.

Let us point out that the right-hand side of (14) satisfies the orthogonality conditions (1) regardless of whether vanishes or not. So, for and defined from (14), the condition is equivalent to that is the only solution of (1) up to multiplication by a nonzero constant. For instance, if and , then for every polynomial of degree satisfying (1) is equal to times some constant.

The next fact on perfectness is a variant of ([28], Lemma 3.4).

Lemma 2.

Let . For the linear functionals to have all indices , , normal (and to form a perfect system when ), it is necessary and sufficient that for each index with , there exists a polynomial of degree such that for it satisfies .

Proof.

The “only if” part follows directly from the definition of normality. The “if” part follows by induction in . For the base of the induction, observe that the index is always normal, as the corresponding orthogonal polynomial is not supposed to obey any orthogonality conditions.

Now, suppose that the index with is not normal, while all indices satisfying are normal. Then there is a polynomial of degree . Moreover, there is also some and index satisfying , as well as for with denoting the Kronecker delta such that . Consequently, the normality of implies that must coincide with Q up to multiplication by a constant. The equality is, however, impossible because and . So, the index can only be normal. By induction, we prove the normality of all the indices with . □

Another proof of Lemma 2.

The “only if” part follows directly from the definition of normality. The “if” part follows by induction in . For the base of the induction, observe that the index is always normal, as the corresponding orthogonal polynomial is not supposed to obey any orthogonality conditions.

Now, suppose that the index with for some is not normal, while the index is normal. Then and . Write the orthogonal polynomial via the determinant formula (14), then , which contradicts to . □

Proof of Proposition 3

Observe that if for a polynomial Q the conditions and are simultaneously satisfied, then . Therefore, by Lemma 2 the perfectness is equivalent to that for all and .

On multiplying (12) for by and then acting by , we arrive at

In particular, the “only if” assertion of the proposition immediately follows from this identity: for some and j implies absence of the perfectness by Lemma 2, while the conditions for with are clearly necessary for perfectness.

For the “if” assertion, observe that all indices satisfying are normal: trivially when , and by the proposition’s assumption when . By induction in , let us show that each index with is normal provided that all indices satisfying are normal. According to Lemma 2, it is enough to prove that for all j and with . For each j such that , we immediately have due to (15). The case and for all k follows from the proposition’s conditions.

Now, let and for some k. Then would mean that , and hence . Due to the normality of the index , the polynomial then would be identically equal to up to normalization. That would mean that and

which contradicts the induction hypothesis.

Note that the explicit form of the nearest-neighbor-recurrence coefficients for the Jacobi–Piñeiro, multiple Laguerre and Hermite polynomials are known [40]. Therefore, Theorem 1 can be proved using Proposition 3. However, we use another approach based on raising operators that we also apply to Theorem 2.

4. Proof of Theorem 1

First let us recall some of the details we need below. All systems of weights listed in (a)–(e) just before Theorem 1 are of two sorts depending on the ratios of the weights: namely, for running over

At the same time, the following commutation properties hold:

So, iterative application of these identities yields

whenever . This commutativity along with (16) allows us to take the indices in any order, which is important for the compositions of the so-called raising operators. Given , by

we denote the weight corresponding to the parameters and instead of respectively and (if any of them presents); the parameter in (d)–(e) remains the same, so we omit it from the notation. In particular, Now introduce the raising operators defined on polynomials by

allow us to rewrite Rodrigue’s Formula (8) up to a normalization as

where the terms of the product are taken so that increases for each , while the terms for different j may be mixed. In other words, the order of can follow any of the paths in from the origin to of length . In particular, the left-most (outer) operator is for some j. The next lemma connects the polynomials determined via (19) with the orthogonality conditions (1).

By , we denote the set for the functionals

Lemma 3.

Let , and let the parameters satisfy the corresponding conditions of Theorem 1. Then, given a polynomial Q, the conditions and for defined in (18) are equivalent.

Proof.

Let and consider the cases (a)–(c). Application of (18) and (16) and observing that the off-integral terms in the integration by parts disappear yield

Here, the right-hand side vanishes precisely when the left-hand side does. For , the coefficient near the integral on the right-hand side is nonzero due to . Therefore, if and only if .

Analogously, in the cases (d)–(e) from (16), (17), (18) and the vanishing of the off-integral terms when integrating by parts, we have

where is now a dummy parameter. The right-hand side of the last equality also vanishes precisely when the left-hand side does. For , the coefficient near the latter integral on the right-hand side is nonzero due to . The equality holds for all , and consequently if and only if . □

Remark 5.

If the conditions of Theorem 1 hold for the cases (a)–(c) except that for some , then we can reorder j and k so that . Then the condition for implies , as is seen from the proof of Lemma 3.

Similarly, if in the cases (d)–(e) we have for some , then implies .

Proof of Theorem 1.

For each index we construct a polynomial according to Rodrigues’s Formula (8), which is equivalent to the Formula (19) comprising iterations of the raising operator (18) applied to . As is seen from (19), this construction is correct, as the resulting polynomials do not depend on the path from the origin to , determining the order of the iterations. Moreover, due to Lemma 3 guarantees that .

Now we argue by contradiction. Let there exist an index such that Then Lemma 3 iterated times yields which may be tested directly:

Note that, for non-integer values of (resp. or ) one needs to take the continuous branch of (respectively or ) over the whole integration contour. In the cases (a), (c) and (d), the constant equals 1 when the integration contour is a line interval. Then Hankel’s formula yields for a cardioid in (b) and, via the reflection formula, and for a closed contour turning around the origin in (c) and (d), respectively. In the case (a), we have

see ([46], Section 1.6), also ([47], p. 59) or [24]. Under the conditions of the theorem, the right-hand side of (21) does not vanish. This contradiction implies that for every .

Now, if the parameters of the weights fall outside the conditions listed in the theorem, then the normality fails for certain indices as is seen from Lemma 3, Remark 5 and Formula (21). □

Note that in the cases (a) and (c), if or is a negative integer, then it is impossible to introduce the perfect functionals so that the polynomials given by (8) would satisfy (1) for all indices . Observe that already for , the Jacobi case for or can sometimes provide a perfect system, although the orthogonality conditions then cannot be written in the form (1): the linear functional for that must be replaced by a bilinear form as is done in [48,49]. (Indeed, from [24,49] it essentially follows that the perfectness of (certain limits of) the monic Jacobi polynomials with these bilinear forms is equivalent to at least one of the conditions and .)

Let us show that (1) does not fit the proper orthogonality conditions for, say, the case and of Jacobi polynomials determined by (7) when the indices are allowed to be greater than N. Observe that the lower triangular matrix

of the Jacobi polynomials’ coefficients and, hence, its inverse is a block-diagonal (consisting of two blocks on the diagonal each, the first block is of size ), so the right-hand side of the formula

is also a block-diagonal matrix. At the same time, the matrix on the left-hand side must have the Hankel structure due to , cf. (13). This contradiction shows that the corresponding bilinear form must allow the Gram matrix to have a block-diagonal structure. The case and follows on choosing

and replacing x by on the left-hand side of (22).

5. Proof of Theorem 2

A proof via the generalized Vandermonde determinants [33] does not work in the case of complex parameters: it exploits that an integral of a real continuous non-vanishing function is nonzero. Instead, we rely on Lemma 2 and on properties of the raising operators (18).

First, let us describe some properties of the classical multiple discrete polynomials. Given an index reflecting the shift of the parameters, put

Accordingly, the raising operator can be written in the form

The ratios of weights on the right-hand side of this equality are polynomials: namely,

where (assuming in the Hahn case)

Lemma 4.

The raising operators commute in the sense that, if and , then

Proof.

For ,

The lemma follows from that the coefficients here are symmetric. Indeed, near we have

the coefficient near equals

and the coefficient near is

□

Lemma 4 allows us to write the difference Rodrigue’s formula

where the terms of the product are taken so that increases for each , while the terms for different j may be mixed. In other words, the order of can follow any of the paths of length in from the origin to . As in the continuous case, the left-most (outer) operator is for some j. In what follows, formula (25) is shown to give the orthogonal polynomials for the system of weights satisfying Theorem 2.

5.1. Details on Meixner Weights

The Meixner weight w has all moments finite only if , although the corresponding orthogonal polynomials may still be found through Rodrigues’s formula when . In this section, we consider complex measures suitable for all , , with respect to the Meixner polynomials, which are orthogonal. Except for the degenerate case , the most general measure is continuous and supported on an infinite curve in . Then the standard discrete measures stem from calculating the integrals through the Cauchy theorem. The case is trivial, as the weight identically equals zero.

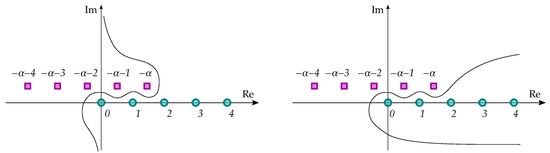

Generic case .

Let log be the principal branch of the logarithm, and let ; for we assume . Denote and observe that is bounded for z satisfying , that is for z varying in a halfplane (or the whole plane if ). Note that points inside this halfplane. We need the following two observations.

- (a)

- For , we have . Since the ratio vanishes exponentially for provided that , as well as for provided that and for some . In particular, it vanishes for .

- (b)

- Unless , the ratio vanishes for exponentially due to , cf. ([50], Proposition 9).

Consequently, given and , there exists a simple smooth curve L separating the poles of from the poles of tending to infinity so that the integral

absolutely converges for each fixed polynomial Q, see Figure 2. The positive direction of L may be chosen, e.g., so that remains on the left-hand side from L.

Figure 2.

The curve L suitable for the Meixner weight if (left) and if (right).

For , the integral may be calculated using the Cauchy theorem. Indeed, according to (a), for and any , the curve L may be replaced (without changing the integral’s value) with the union of circles , thus giving

Analogously, for , we obtain

which corresponds to the following relation between the Meixner polynomials:

stemming from the Pfaff transformation of hypergeometric functions (see ([47], p. 68) or ([39], Equation (1.4.9)).

Degenerate case .

Replace b by . On the one hand, the coefficients of Rodrigues’s formula for the Meixner polynomials then turn into those for the Krawtchouk polynomials—up to normalizing (correcting the sign) of odd-degree polynomials. Put in other words, the Meixner polynomials in this case reduce to the Krawtchouk polynomials, and the latter system is considered finite.

On the other hand, the Meixner weight defined in Table 2 is infinite for , but it can be easily regularized by a 1-periodic factor vanishing at : on multiplying w by and using Euler’s reflection formula, we arrive at

and the right-hand side is exactly the Krawtchouk weight; see Table 2. Our regularization may be avoided by defining l using integration over a large enough circle:

then the Cauchy integral theorem reduces the last expression to the Krawtchouk case (the circle may be replaced with other closed smooth curves separating the set from infinity).

5.2. Integration Curve for Continuous Hahn Weight

The Hahn weight w is usually defined for , and the corresponding measure is supported on the finite set . Nevertheless, general parameters are also well understood: in certain cases, the corresponding orthogonality measures turn to be discrete and finitely supported, while the generic case corresponds to a continuous weight on a complex curve.

Generic case here is . If so, follow [31] and choose to be a smooth curve ending at and separating from . Then the integral

absolutely converges for any polynomial Q: the ratios of gamma-functions behave at infinity as powers of z, while the product of sines yields exponential decay. As is noted in Section 2.2.1 above, the degenerate case, when at least one of the numbers , , , is a negative integer, reduces to a discrete weight.

5.3. Properties of Raising Operators

Charlier polynomials. The raising operator for Charlier polynomials reads

Lemma 5.

Given a system of Charlier weights as in Table 2 on , let be such that for some . Suppose that the parameters of the weights for satisfy for all . Then the conditions and are equivalent.

Proof.

It is clear that is zero for , so summation by parts yields

The right-hand side of this formula vanishes precisely when the left-hand side does. Since whenever , we immediately obtain if and only if . □

Meixner I polynomials. For the Meixner I polynomials, the raising operator has the form

Lemma 6.

Given and a system of continuous Meixner weights

on the curves defined as above, , let there be and some such that . If for all , then the conditions and are equivalent (provided that , which is necessarily true if for all j).

Proof.

Denote , then

where the third equality follows on replacing with : the integration gives the same result, as both curves have similar asymptotic behavior and separate the poles of and . Therefore,

The right-hand side of this formula vanishes precisely when the left-hand side does. Since whenever , we immediately obtain if and only if . □

Meixner II polynomials. For the Meixner II polynomials, the raising operator is given by

Lemma 7.

Given and a system of continuous Meixner weights

on the curves defined as above, , let there be an index and some such that . If for all , then the conditions and are equivalent (provided that , which is necessarily true for ).

If for some j, then the functional is not quasi-definite (cf. Remark 3), and hence the whole system cannot be perfect.

Proof.

Let . Similarly to the case of the Meixner I polynomials,

where the last equality follows on replacing with . For , the right-hand side equals

as desired. For , we obtain , and hence

The right-hand side of this formula vanishes precisely when the left-hand side does. Since whenever , we immediately obtain if and only if . □

Krawtchouk polynomials. This case may be reduced to the case of Meixner I polynomials on changing the sign of b. Nevertheless, we consider it here separately—for completeness.

Lemma 8.

Given a positive integer N and a system of Krawtchouk weights , let an index and some be such that . Suppose that for , as well as for all . Then the conditions and are equivalent (provided that , which necessarily hold true for ).

Proof.

Note that defined in Table 2 is zero for , so on plugging in (27) and using summation by parts, we have

The right-hand side of this formula vanishes precisely when the left-hand side does. Since whenever , we immediately obtain if and only if . □

Hahn polynomials.

The raising operator for Hahn polynomials is

Observe that is a polynomial of degree provided that the term in its leading coefficient does not vanish. The constant coefficient is , so it cannot vanish unless .

Lemma 9.

Given and a system of discrete Hahn weights on such that and for all j, let an index for some satisfy . If for all such that , then

Moreover, implies .

Proof.

Note that is zero for , so for

whence for

For , we arrive at

Both sides of the formula are equal to zero simultaneously. Since and whenever , on testing for we immediately obtain that if and only if . □

Lemma 10.

Given a system of continuous Hahn weights

on curves , where , choose some and an index such that . If for all such that , then the conditions and are equivalent (provided that ).

Proof.

The approach is similar to the case of multiple Meixner II polynomials. Let us remind that , and let m run over .

where the last equality follows by replacing with , and then noting that

Replacing with does not change the integral’s value, as both curves have similar asymptotic behavior and separate the poles of and

The right-hand side of this formula vanishes precisely when the left-hand side does. Since whenever , we immediately obtain if and only if . □

Proof of Theorem 2.

Let , where additionally if . We apply the notation (23)–(24). For the index , the polynomial of degree 0 is trivially orthogonal with respect to the functionals stemming from the weights . Moreover, in the cases allowing summation over discrete weights, we have

where the Hahn case follows from the Chu–Vandermonde identity ([47], p. 67), ([39], Equation (1.4.3)):

Observe that the expressions (29) for the Meixner weights remain valid (up to normalization) when we pass to parameters needing continuous weights. For the continuous Hahn weights, the expression is

see ([31], Equation (4)). As a result, under the conditions (i)–(v) of Theorem 2.

Using this fact as a base, we now apply induction in . Put if , and otherwise. Given M, for all shifts satisfying and for all indices satisfying , let be the unique polynomial of degree constructed via Rodrigues’s Formula (25). Let us show that the same holds for satisfying . Indeed, by Lemma 4, the polynomials

do not depend on j such that . Since , we have . Therefore, Lemmas 5–9 imply that . Moreover, under the theorem’s conditions (i)–(v), each of the raising operators increases the degree of polynomials by 1, and thus . So, Lemma 2 furnishes the proof of the “if” assertion of the theorem.

The “only if” assertion follows on noting that if the relevant condition of Theorem 2 fails to hold, then there is an index that is not normal. Indeed, either the raising operator does not increase degrees of polynomials, or for some and j, which is seen from (29) and (30).

More specifically, for the Charlier, Meixner and Krawtchouk weights, the condition or means that the jth weight is not zero identically, which is already required for the normality of the index .

Now, let in the Krawtchouk case; then the corresponding raising operator does not increase the degree of polynomials, and unless , the polynomial turns to be orthogonal to all monomials by Lemma 8, meaning absence of normality for . If , the Krawtchouk weights are supported on points, so the polynomial is orthogonal to all monomials; thus, the normality of is only possible if . Moreover, the condition is required by normality when .

The case of the Meixner I system is similar to the Krawtchouk case: we only have to replace and . For , the Meixner functionals should be replaced by their regularization—that is by the Krawtchouk functionals.

The “only if” assertion of Theorem 2 for the Meixner II system may be dealt analogously. The main difference here is seen from (26): if , then Lemma 2 implies the absence of normality for the orthogonal polynomial produced by iterations of the raising operator.

For the Hahn polynomials, if or , then in Theorem 2, we have . In this case, if for some k and , then

for all yielding the absence of normality of the corresponding indices (i.e., the indices with are not normal). Analogously, if , then for all indices , and hence, there is no normality for .

If , then is a polynomial of degree if and only if . So when for some index , we still obtain an orthogonal polynomial by iterations of the raising operator, while implies absence of normality of . As is seen from (29) and (30), such a situation cannot occur under the condition that for all j and . When and for all k, one tests this condition for to verify the normality of all indices satisfying . (For the index when but or , the orthogonal polynomials are given by the regularization: respectively, or .) □

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hermite, C. Sur la fonction exponentielle. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris Sér. I Math. 1873, 77, 18–24, 74–79, 226–233, 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Van Assche, W. Multiple orthogonal polynomials, irrationality and transcendence. In Continued Fractions: From Analytic Number Theory to Constructive Approximation; Berndt, B.C., Gesztesy, F., Eds.; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1999; Volume 236, pp. 325–342. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin, V.N. Cyclic graphs and Apéry’s theorem. Russ. Math. Surv. 2002, 57, 535–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.N. On Salikhov’s integral. Trans. Moscow Math. Soc. 2016, 77, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcovecchio, R. Vectors of type II Hermite-Padé approximations and a new linear independence criterion. Ann. Mat. Pura Appl. 2021, 200, 2829–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijlaars, A.B.J. Multiple orthogonal polynomial ensembles. In Recent Trends in Orthogonal Polynomials and Approximation Theory; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2010; Volume 507, pp. 155–176. [Google Scholar]

- Aptekarev, A.I.; Denisov, S.A.; Yattselev, M.L. Self-adjoint Jacobi matrices on trees and multiple orthogonal polynomials. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 2020, 373, 875–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doliwa, A. Non-commutative Hermite-Padé approximation and integrability. Lett. Math. Phys. 2022, 112, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, K. Perfect systems. Compos. Math. 1968, 19, 95–166. [Google Scholar]

- Chihara, T.S. An Introduction to Orthogonal Polynomials. Mathematics and Its Applications; Gordon and Breach Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA; London, UK; Paris, France, 1978; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Nikishin, E.M.; Sorokin, V.N. Rational approximations and orthogonality. In Translations of Mathematical Monographs; Boas, R.P., Translator; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1991; Volume 92, pp. viii+221. [Google Scholar]

- Coussement, J.; Van Assche, W. Gaussian quadrature for multiple orthogonal polynomials. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2005, 178, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, G.V. Generalized weighted Birkhoff-Young quadratures with the maximal degree of exactness. Appl. Numer. Math. 2017, 116, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, A.N.; Stanić, M.P.; Tomović, T.V. Construction of the optimal set of quadrature rules in the sense of Borges. Electron. Trans. Numer. Anal. 2018, 50, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforov, A.F.; Uvarov, V.B. Special Functions of Mathematical Physics; A Unified Introduction with Applications; Boas, R.P., Samarskiĭ, A.A., Translators; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 1988; pp. xviii+427. [Google Scholar]

- Van Assche, W.; Coussement, E. Some classical multiple orthogonal polynomials. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2001, 127, 317–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aptekarev, A.I.; Branquinho, A.; Van Assche, W. Multiple orthogonal polynomials for classical weights. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 2003, 355, 3887–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aptekarev, A.I.; Bleher, P.M.; Kuijlaars, A.B.J. Large n limit of Gaussian random matrices with external source. II. Commun. Math. Phys. 2005, 259, 367–389. [Google Scholar]

- Bleher, P.M.; Kuijlaars, A.B.J. Random matrices with external source and multiple orthogonal polynomials. Int. Math. Res. Not. 2004, 2004, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, P.; Forrester, P.J. Asymptotic correlations for Gaussian and Wishart matrices with external source. Int. Math. Res. Not. 2006, 2006, 27395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro Días, L.R. On simultaneous approximations for some collection of Markov functions. Vestn. Moskov. Univ. Ser. I Mat. Mekh. 1987, 1987, 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, M.; van Moerbeke, P.; Wang, D. Random matrix minor processes related to percolation theory. Random Matrices Theory Appl. 2013, 2, 1350008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcellán, F.; Rocha, I.A. Complex path integral representation for semiclassical linear functionals. J. Approx. Theory 1998, 94, 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kuijlaars, A.B.J.; Martinez-Finkelshtein, A.; Orive, R. Orthogonality of Jacobi polynomials with general parameters. Electron. Trans. Numer. Anal. 2005, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kuijlaars, A.B.J.; McLaughlin, K.T.R. Asymptotic zero behavior of Laguerre polynomials with negative parameter. Constr. Approx. 2004, 20, 497–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijlaars, A.B.J.; Martínez-Finkelshtein, A. Strong asymptotics for Jacobi polynomials with varying nonstandard parameters. J. Anal. Math. 2004, 94, 195–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhin, E.; Varchenko, A. Multiple orthogonal polynomials and a counterexample to the Gaudin Bethe Ansatz Conjecture. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 2007, 359, 5383–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckermann, B.; Coussement, J.; Van Assche, W. Multiple Wilson and Jacobi-Piñeiro polynomials. J. Approx. Theory 2005, 132, 155–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiforov, A.F.; Suslov, S.K.; Uvarov, V.B. Classical Orthogonal Polynomials of a Discrete Variable; Springer Series in Computational Physics; Translated from the Russian; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1991; pp. xvi+374. [Google Scholar]

- Atakishiyev, N.M.; Suslov, S.K. The Hahn and Meixner polynomials of an imaginary argument and some of their applications. J. Phys. A 1985, 18, 1583–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askey, R. Continuous Hahn polynomials. J. Phys. A 1985, 18, L1017–L1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, J.; Kriecherbauer, T.; McLaughlin, K.T.R.; Miller, P.D. Discrete Orthogonal Polynomials; Annals of Mathematics Studies; Asymptotics and Applications; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 164, pp. viii+170. [Google Scholar]

- Aversú, J.; Coussement, E.; Van Assche, W. Some discrete multiple orthogonal polynomials. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2003, 153, 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Vinet, L.; Zhedanov, A. Automorphisms of the Heisenberg-Weyl algebra and d-orthogonal polynomials. J. Math. Phys. 2009, 50, 033511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévost, M.; Rivoal, T. Remainder Padé approximants for the exponential function. Constr. Approx. 2007, 25, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, H.; Tsujimoto, S.; Vinet, L.; Zhedanov, A. An algebraic model for the multiple Meixner polynomials of the first kind. J. Phys. A 2012, 45, 325205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndayiragije, F.; Van Assche, W. Multiple Meixner polynomials and non-Hermitian oscillator Hamiltonians. J. Phys. A 2013, 46, 505201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, M.; Delvaux, S.; Kuijlaars, A.B.J. Multiple Meixner-Pollaczek polynomials and the six-vertex model. J. Approx. Theory 2011, 163, 1606–1637. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, M.E.H. Classical and Quantum Orthogonal Polynomials in One Variable; Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, W. Nearest neighbor recurrence relations for multiple orthogonal polynomials. J. Approx. Theory 2011, 163, 1427–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aptekarev, A.I.; Derevyagin, M.; Van Assche, W. Discrete integrable systems generated by Hermite-Padé approximants. Nonlinearity 2016, 29, 1487–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aptekarev, A.I.; Derevyagin, M.; Miki, H.; Van Assche, W. Multidimensional Toda lattices: Continuous and discrete time. SIGMA Symmetry Integr. Geom. Methods Appl. 2016, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aptekarev, A.I.; Lysov, V.G. Multilevel interpolation for Nikishin systems and boundedness of Jacobi matrices on binary trees. Russ. Math. Surv. 2021, 76, 726–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, S.A.; Yattselev, M.L. Spectral theory of Jacobi matrices on trees whose coefficients are generated by multiple orthogonality. Adv. Math. 2022, 396, 108114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aptekarev, A.I.; Kalyagin, V.; López Lagomasino, G.; Rocha, I.A. On the limit behavior of recurrence coefficients for multiple orthogonal polynomials. J. Approx. Theory 2006, 139, 346–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdélyi, A.; Magnus, W.; Oberhettinger, F.; Tricomi, F.G. Higher Transcendental Functions; Bateman Manuscript Project; McGraw-Hill Book Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1953; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, G.E.; Askey, R.; Roy, R. Special Functions; Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; Volume 71. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro, M.; Pérez, T.E.; Piñar, M.A.; Rezola, M.L. Sobolev orthogonal polynomials: The discrete-continuous case. Meth. Appl. Anal. 1999, 6, 593–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, M.; de Morales, M.A.; Rezola, M.L. Orthogonality of the Jacobi polynomials with negative integer parameters. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2002, 145, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costas-Santos, R.; Sánchez-Lara, J. Extensions of discrete classical orthogonal polynomials beyond the orthogonality. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2009, 225, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).