Abstract

The Qingshan lead–zinc (Pb–Zn) deposit in northwestern Guizhou Province is a structurally controlled, carbonate-hosted system formed from basin-derived hydrothermal processes. Geology, fluid inclusion, and isotopic data reveal a multi-stage hydrothermal circulation after Emeishan Large Igneous Province (ELIP, ~260 Ma) tectono-thermal reactivation within the Sichuan–Yunnan–Guizhu triangle (SYGT) area. Fluid inclusion microthermometry indicates that ore-forming fluids were derived from deep sources influenced by enhanced crustal heat flow linked with possible thermal input from Indo-Caledonian tectonic activity after ELIP. Ore-stage calcite records mixed carbon derived from marine carbonates with additional inputs from organic matter and deep-sourced fluids, reflecting carbonate dissolution and fluid–rock interaction. Sulfide, together with fluid inclusion temperatures > 120 °C, indicates sulfur derived from evaporitic sulfate reduced by thermochemical sulfate reduction (TSR); the heavy sulfur signature and partial isotopic disequilibrium among coexisting sulfides reflect dynamic fluid mixing during ore deposition. Lead isotopes indicate metallogenic metals were leached mainly from Devonian–Permian carbonates with subordinate basement input. Ore precipitated by cooling, depressurization, and mixing of metal-rich, H2S-bearing fluids in structurally confined zones where the carbonate–clastic interface effectively trapped ore-forming fluids, producing high-grade sphalerite–galena mineralization. Collectively, these data support a Huize-type (HZT) carbonate-hosted Pb–Zn genetic model for the Qingshan deposit.

1. Introduction

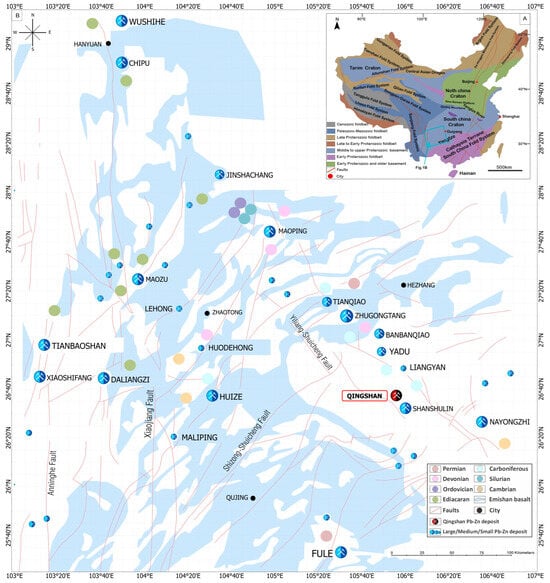

In southwestern China, the Sichuan–Yunnan–Guizhou triangle (SYGT) area, located along the western margin of the Yangtze Block, represents one of the most promising Pb–Zn mineralization belts in the country. It is characterized by numerous carbonate-hosted deposits formed under low- to medium-temperature hydrothermal conditions. The area spans approximately 170,000 km2 and encompasses more than 550 lead and zinc deposits of varying scales, primarily hosted within Sinian to Permian carbonate sequences. The total proven resources are estimated at roughly 30 million tons of combined Pb and Zn, with ore grades typically ranging from 10% to 35%. Structurally, the SYGT area is located within a fault-bounded zone delineated by the Yadu–Shuicheng, Xiojiang, and Mile–Shizong fault systems (Figure 1) [1,2,3].

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic geological map of China, showing the locations of the Yangtze Block and the Sichuan-Yunnan-Guizhou triangle (SYGT) (modified after the work of Wang et al., 2014 [4]); (B) regional geologic map of the SYGT, showing the distribution of sedimentary sequences, Emeishan basalts, major structures, and Zn–Pb deposits (modified after the work of Liu and Lin, 1999 [5]).

Carbonate-hosted Pb–Zn deposits constitute one of the most economically important sources of lead and zinc worldwide, accounting for approximately 27% of global Pb + Zn reserves. These deposits are commonly classified as Mississippi Valley-type (MVT) [6,7], and are typically found in orogenic belts situated along passive margins [8]. Well-known examples of these deposits are located in regions such as the Upper Mississippi Valley in the USA [9], the Irish Midlands in Ireland [10], and Pine Point in Canada [11]. However, the genesis of these deposits is complex, reflecting the interactions among diverse geological, tectonic, and geochemical factors [12,13].

Although a large number of Pb–Zn occurrences within the Sichuan–Yunnan–Guizhou triangle (SYGT) area have been described and investigated, their precise genetic mechanisms remain debated. Multiple models have been proposed to explain the source, migration, and precipitation processes of ore-forming fluids in this region. Some researchers, described in certain studies as representing the prevailing scholarly perspective, classify these deposits mainly as Mississippi Valley-type (MVT) or strata-bound deposits, suggesting their formation was primarily controlled by sedimentary processes [14,15]. In contrast to this view, Han Runsheng et al. have proposed a distinct Huize-type (HZT) classification [2,3,16,17]. Overall, the genesis of these deposits is complex and not fully explained by genetic models linked to the Permian system Emeishan basalt–mantle plume [18].

The Qingshan lead and zinc deposit, representing a medium-sized occurrence in the western part of the Yangtze Block, forms part of the extensive Sichuan–Yunnan–Guizhou triangle (SYGT) area. The deposit contains approximately 0.3 Mt of ore with average grades of 30 wt.% Pb + Zn. Mineralization is mainly hosted within Carboniferous carbonate strata and is structurally influenced by the Weining–Shuicheng fault and related intraformational fault systems [19,20]. The ores, consisting primarily of sphalerite, galena, pyrite, dolomite, calcite, and fluorite, occur as breccia infillings, veinlet networks, disseminations, and locally massive aggregates within dolomitized limestones. Although several studies have examined the Qingshan deposit, its metallogenic evolution remains insufficiently understood. The origin, evolution, and compositional features of the ore-forming fluids, along with the mechanisms of metal migration and precipitation, remain unclear. Consequently, the genetic interpretation of this deposit remains debated, emphasizing the need for integrated research that combines geological observations with fluid inclusion and isotopic analyses.

Building upon earlier research and employing a suite of advanced analytical methods, this study provides a comprehensive examination of the geological features, fluid inclusion behaviors, and isotopic compositions (C, O, S, and Pb) of the Qingshan Pb–Zn deposit. The main goals of this study are to (1) characterize the physicochemical properties and evolutionary history of the mineralizing fluids through integrated fluid inclusion and carbon–oxygen isotope analyses; (2) determine the origins of sulfur and lead by assessing their isotopic systematics; and (3) interpret the genetic framework of the Qingshan deposit within the broader metallogenic context of carbonate-hosted Pb–Zn systems in the SYGT area. By combining field-based geological observations with isotopic and microthermometric evidence, this research seeks to clarify the formation processes and metal sources of one of Southwest China’s representative Pb–Zn deposits.

2. Regional Geology

The geology of South China comprises two major crustal domains: the Yangtze Block in the northwest and the Cathaysia Block to the southeast [21] (Figure 1A). The Sichuan–Yunnan–Guizhou triangle (SYGT) area occupies the southwestern margin of the Yangtze Block and forms part of a metallogenic area characterized by low- to medium-temperature Pb–Zn mineralization [22]. This area covers more than 170,000 km2 and contains over 550 identified Pb–Zn deposits, collectively representing roughly 27% of China’s overall Pb–Zn resources [13,23].

The SYGT area is bounded and structurally influenced by three prominent regional fault systems: the northwest-trending Kangding, Yiliang, Shuicheng, the north–south-oriented Xiaojiang, and the northeast-trending Mile- Shizong and Shuicheng fault zones (Figure 1B). These long-lived fault systems have experienced multiple episodes of activation and reactivation through various tectonic events, serving as crucial conduits for hydrothermal fluids and controlling the spatial distribution of Pb–Zn mineralization in the area [24]. During the Late Indo-Chinese orogeny, the convergence between the Yangtze and Indosinian blocks generated an intracontinental strike–slip fault system that promoted the ascent of deep-seated hydrothermal solutions, creating favorable conditions for extensive base-metal mineralization [2,20].

Geologically, the SYGT area is underlain by a metamorphic basement overlain unconformably by thick sedimentary successions and basaltic units related to the Emeishan large igneous province [3] (Figure 1B). The basement comprises successively younger Precambrian sequences, including Archean crystalline rocks of the Kangding Group (~3.3–2.9 Ga) [25,26], Mesoproterozoic metamorphic formations of the Dongchuan Group (~1.7–1.5 Ga) [27], and Neoproterozoic metamorphic rocks belonging to the Kunyang–Huili Groups (~1.1–0.9 Ga) [28,29].

The sedimentary sequence in the region includes Sinian system to Triassic marine carbonates and continental deposits ranging from the Jurassic to the Quaternary. The marine carbonates of Sinian system to Triassic age constitute the primary host rocks for mineralization [3], whereas basaltic flows of the Late Permian Emeishan large igneous province (259 ± 3 Ma) are widely distributed throughout the region [30] (Figure 1B).

Complex metallogenic dynamics operating within this stratigraphic framework facilitated the formation of numerous Pb–Zn and Ag–Pb–Zn deposits of varying scales, including world-class large deposits such as Huize, Maoping, Zhugongtang and Fule; medium-sized deposits such as Tianqiao, Shanshulin and Qingshan; and smaller deposits including Liangyan, Yulu and others distributed across the SYGT [3] (Figure 1B).

3. Ore Deposit Geology

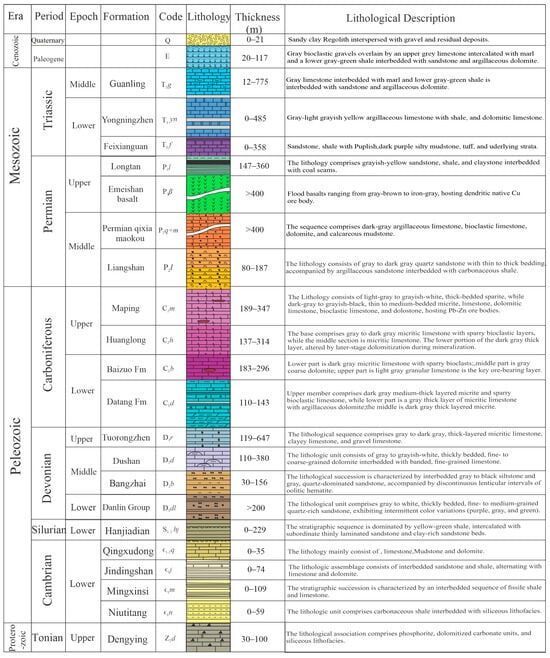

The Qingshan deposit is a medium-sized Pb–Zn deposit located 10 km east of Liupanshui City, Guizhou Province, and lies within the broader Sichuan–Yunnan–Guizhou (SYG) metallogenic province. It holds substantial resources, with an estimated 0.3 Mt of 9.9 wt.% Pb and 22.3 wt.% Zn. The stratigraphy includes (Figure 2) the Lower Carboniferous Baizuo Formation (C1b), composed of dolomitic limestone, which is succeeded stratigraphically by the Upper Carboniferous Huanglong Formation (C2h) and the Maping Formation (C2m), both predominantly consisting of carbonate rocks. This sequence transitions into the middle Permian Liangshan Formation (P2l), characterized by sandstone, shale, and siltstone. The Liangshan Formation is conformably succeeded by the middle Permian Qixia–Maokou Formation (P2q+m), which consists predominantly of carbonate rocks. A disconformity separates the Upper Permian Emeishan Formation (P3β), dominated by basalts, from the coal-bearing clastic rocks of the Longtan and Dalong formations (P3l+d). The upper stratigraphic levels of the Maping Formation (C2m), composed mainly of limestone and dolomitic limestone, contain the principal ore bodies (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Comprehensive stratigraphic columnar diagram of Northwest Guizhou region (modified from the work of Jing Zhongguo, 2008) [31].

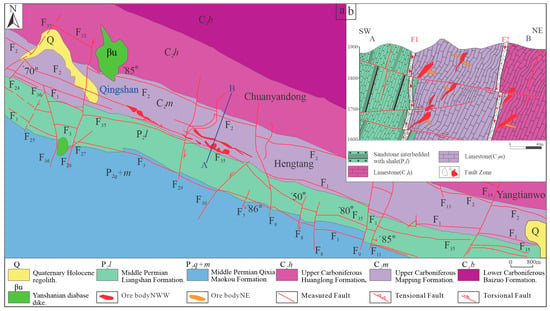

Figure 3.

Geological map of the Qingshan lead-zinc deposit (a), cross-section of the ore bodies (b).

The distribution of ore bodies is influenced by the Weining–Shuicheng fault, associated with intraformational faults, NW-trending tight folds, and related fracture systems. The principal ore bodies are hosted mainly within the Maping Formation, governed by fractures oriented roughly NWW and NNE–NE (Figure 3). The primary control fractures F1 and F2 are a set of NWW inter-layer fractures dipping 75–85° towards SW and are generally consistent with the bedding. The footwall of F1 is the source of inter-layer fractures, whereas the primary ore body is endowed in the backslope (Figure 3). This deposit’s ore-controlling structure is orientated in the same direction as the “Normal Faults-Anticlines” combination [20,32].

The ore bodies strike between NW 75 and 80°, trend SW, and extend laterally towards SE. The extension direction of the primary ore body aligns with the NWW-oriented fractures and strata, exhibiting more extension than depth. The ore bodies are substantial, sac-shaped, brecciated, and vein-like, primarily formed in the voids of the NW fractures and mainly hosted within the NW-trending F1 fault zone and its footwall-derived secondary folds. Key fault systems include NW-NE-trending faults, as well as some N-S-oriented faults, which promote the formation of NW-trending interlayer fractures and NE-trending joints, providing pathways for hydrothermal fluid flow and mineralization [33]. The ore mostly consists of sulfide minerals (galena, sphalerite), with a lesser presence of oxide minerals. The ores predominantly exhibit blocky, brecciated, banded, vesicular, and honeycomb characteristics.

The alteration types of the surrounding rocks of the Qingshan lead–zinc deposit are primarily categorized as carbonatization, pyritization, and chloritization. Carbonatization is primarily characterized by calcite, with dolomitization occurring concurrently.

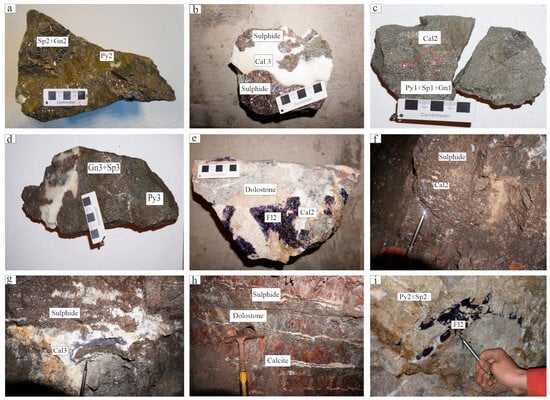

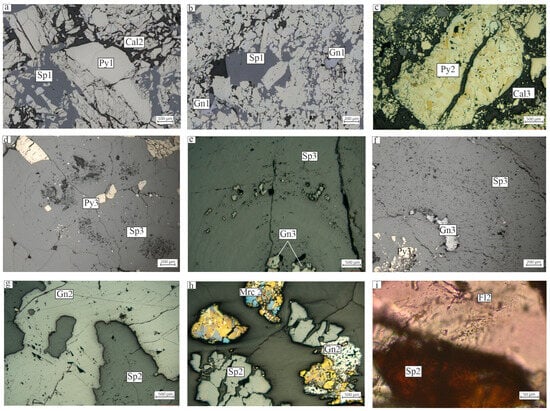

Mineralization is characterized by the predominance of sphalerite, galena, and pyrite, accompanied by calcite, fluorite, and dolomite as the main gangue minerals (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Ore mineralization predominantly occurs as massive sulfide bodies (Figure 4a,c,d), breccia where sulfide clasts are cemented by late-stage calcite (Figure 4b,g), vein and stockwork fillings (Figure 4f,h), and vug-filling where fluorite and calcite precipitate in open cavities (Figure 4e,g,i). At the microscopic level, these ores display a range of textures that reveal their formation history, including fragmentation of early minerals (Figure 5a,c), replacement of sphalerite by galena (Figure 5g,h), presence of euhedral–subhedral granular grains (Figure 5b), veinlet-filling (Figure 5f) and enclosed textures (Figure 5d,e), which are standard, illustrating the multi-stage nature of the deposit.

Figure 4.

Field photographs illustrating ore styles and textures. (a,d) Massive ore showing intergrown Sp, Gn, and Py. (b,g) Breccia ore with sulfide clasts cemented by late Cal-3. (c) Abundant Py-1, Sp-1, Gn-1 with minor Cal-2. (e,i) Open-space vugs filled with purple Fl-2, Cal-2, Py-2 and Sp-2. (f) Late-calcite veinlet cross-cutting sulfides. (h) Stockwork mineralization in the host dolostone. Abbreviations: Py = pyrite, Sp = sphalerite, Gn = galena, Fl = fluorite, Cal = calcite.

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs showing the textural features of ore minerals at the Qingshan deposit (a) brecciated pyrite (Py1) cemented by sphalerite (Sp1) and later calcite (Cal2). (b) Interstitial galena (Gn1) between subhedral sphalerite (Sp1) grains. (c) Late-stage calcite (Cal3) cementing fractured main-stage pyrite (Py2). (d) Disseminated pyrite (Py3) inclusions within late sphalerite (Sp3). (e) Galena (Gn3) inclusions within late sphalerite (Sp3). (f) Late galena (Gn3) and pyrite (Py3) filling a microfracture within sphalerite (Sp3). (g) Galena (Gn2) replacing earlier sphalerite (Sp2). (h) Replacement of sphalerite (Sp2) by galena (Gn2), associated with later bladed marcasite (Mrc2). (i) Intergrown anhedral sphalerite (Sp2) and gangue fluorite (Fl2). Mineral abbreviations used in the figures include: galena (Gn), marcasite (Mrc), pyrite (Py), and sphalerite (Sp).

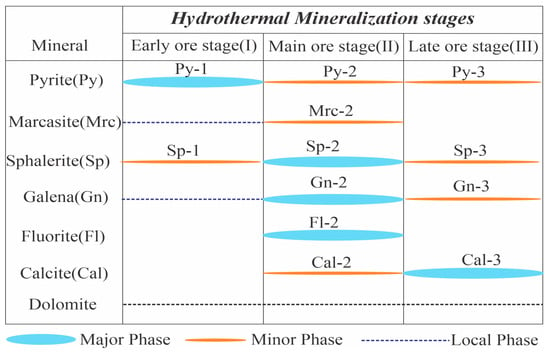

Detailed petrographic analyses of mineral assemblages and their cross-cutting relations indicate a three-stage evolution of hydrothermal mineralization: an early ore stage, a main ore stage, and a late ore stage (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Paragenetic sequence mineralization stages at the Qingshan deposit.

Early ore—stage 1: The earliest hydrothermal event is recorded by coarse, angular fragments of pyrite (Py1) that are cemented by sphalerite and minor calcite (Figure 5a and Figure 4c). The dominant sulfide mineral of this stage, sphalerite (Sp1), forms a subhedral granular matrix around the Py1 clasts. Subsequently, minor galena (Gn1) precipitated as anhedral grains within the interstitial spaces between the larger Sp1 crystals (Figure 5b), suggesting it precipitated slightly after or coevally with Sp1 (Figure 5b).

Stage 2 (main ore stage): The main economic mineralization stage is defined by a complex mineral assemblage dominated by sphalerite (Sp2) and galena (Gn2), with lesser pyrite (Py2) and marcasite (Mrc2), and associated gangue minerals fluorite (Fl2) and calcite (Cal2). In hand specimens, this assemblage fills vugs within the dolostone host rock, where purple fluorite (Fl2) is observed co-crystallizing with sulfides (Figure 4e,i). Petrographic analysis reveals a clear paragenetic sequence where the precipitation of sphalerite (Sp2) with that of galena (Gn2), as evidenced by textures of Gn2 embaying and overgrowing Sp2 (Figure 5g,h). This replacement is often associated with the subsequent deposition of bladed marcasite (Mrc2) (Figure 5h).

Stage 3 (late ore stage): The late hydrothermal event is marked by extensive formation of coarse-grained calcite (Cal3). This late calcite is texturally distinct and clearly post-dates the primary sulfide mineralization, acting as a cement that fills fractures and encloses fragments of earlier minerals. This is best exemplified by its cementation of brecciated main-stage pyrite (Py2) (Figure 5c). Minor, late-stage sulfides are also associated with this stage, including disseminated blebs of pyrite (Py3) (Figure 5d) and anhedral crystals of galena (Gn3) (Figure 5e). Furthermore, this late galena (Gn3), along with minor pyrite (Py3), is observed within late-stage veinlets that cross-cut earlier sphalerite (Sp2) (Figure 5f).

4. Research Methods

4.1. Sampling Methods and Sample Processing

Characteristic ore and host rock specimens were systematically obtained from underground workings and drill cores intersecting the four main ore bodies in the Qingshan Pb–Zn mining area (Figure 3). Mineral separates were carefully sorted under a stereoscopic microscope, attaining 99% purity before subsequent analysis. Double-polished thin sections with a thickness of approximately 200 µm were prepared for fluid inclusion studies. Petrographic examination selected six samples for detailed microthermometric analysis, resulting in datasets of 25 fluid inclusions in sphalerite, 55 in fluorite, and 41 in calcite. For stable isotope geochemistry, 22 calcite samples were analyzed for their carbon and oxygen compositions (δ13C and δ18O). Additionally, five sulfide samples (pyrite, sphalerite, and galena) were analyzed for their sulfur isotope ratios (δ34S). Finally, lead (Pb) isotope compositions were determined on three galena samples.

4.2. Analytical Methods

Microthermometric measurements of fluid inclusions were conducted at the Fluid Inclusion Laboratory of Yunnan Provincial Engineering Research Center for Mineral Resources Prediction and Evaluation, Kunming. A Linkam THMS600 heating–freezing stage mounted on a petrographic microscope was used to perform the fluid inclusion analyses. Prior to data acquisition, calibration utilized standard reference inclusions that are internationally used for fluid inclusion studies. The operational temperature range for measurements was −195 to +600 °C, with an estimated precision of ±0.1 °C for temperatures below 25 °C, ±1 °C between 25 and 300 °C, and ±2 °C for temperatures above 300 °C. Salinity, reported as NaCl equivalent (wt.% NaCl equiv.), was calculated from the final ice-melting temperatures (T_m, ice) following the equations in [34].

Carbon and oxygen isotope analyses were conducted on calcite samples at Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology (BRIUG), employing a high-precision MAT-253 mass spectrometer and following the 100% phosphoric acid preparation method [35], in which the reaction of calcite with H3PO4 generates CO2. The analytical reproducibility, based on repeated analyses of unknown samples, was better than ±0.2‰ (2σ) for δ13C and ±1‰ (2σ) for δ18O. All isotope ratios are expressed relative to the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (V-PDB) and Standard Mean Ocean Water (SMOW) scales.

In situ sulfur isotope analyses were carried out at Guangzhou Tuoyan Testing Technology Co., Ltd. Guangzhou, China, using a New Wave Research NWR193 nm laser ablation system coupled to a Thermo Scientific Neptune Plus MC-ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Measurements were performed using a laser fluence of 3.5 J/cm2, a repetition rate of 3 Hz, and a spot diameter of 25–37 μm, employing a single-spot approach. Helium served as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 700 mL/min, with argon used as the auxiliary gas at a flow rate of 0.96 L/min. The Neptune Plus MC-ICP-MS collected 34S, 33S, and 32S signals using Faraday cups L3, C, and H3, respectively. Sulfur isotope compositions were calculated as δ34S values using the standard formula: δ34S = [(34S/32S)_sample/(34S/32S)_standard − 1] × 1000, achieving a high precision of 2SE ≤ 0.2‰. The IAEA-S-1 (Ag2S, δ34S_VCDT = −0.3‰) standard was used, and δ34S values were normalized to the Vienna Canyon Diablo Troilite (VCDT). Instrumental drift was corrected using a standard–sample–bracketing (SSB) approach, with the standard analyzed once before and after every five samples. Detailed procedures follow those described in previous studies [36,37,38].

In situ Pb isotope measurements of sulfide minerals were performed at Guangzhou Tuoyan Testing Technology Co., Ltd. Guangzhou, China, using a RESOlution M-50 ArF excimer laser (193 nm) coupled to a Nu Plasma II MC-ICP-MS (Applied Spectra, West Sacramento, CA, USA). Faraday cups H2, H1, Ax, L2, and L4 recorded ion signals for 208Pb, 207Pb, 206Pb, 204Pb + Hg, and 202Hg, respectively. Analytical parameters included a laser energy density of 6 J/cm2, a pulse repetition rate of 5 Hz, spot sizes ranging from 9 to 120 μm, and helium as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 280 mL/min. Mass fractionation was corrected using the standard–sample–bracketing (SSB) approach, and the interference of 204Hg on the 204Pb signal was corrected based on the measured 202Hg and the natural isotopic ratio (202Hg/204Hg = 0.229883). Data quality was monitored using laboratory internal standards, including galena (Gn01) and a pressed pyrite powder tablet (PSPT-2). For further methodological details and parameters, see [37,38,39].

5. Analytical Results

5.1. Fluid-Inclusion Petrography

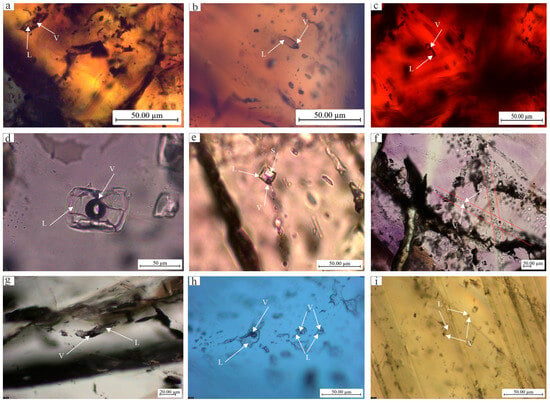

Detailed petrographic observations were carried out on doubly polished thick sections of sphalerite, fluorite, and calcite to investigate the characteristics of the ore-forming fluids. Inclusions were categorized as primary or secondary following criteria established in [40]. Primary inclusions were identified as those occurring in isolation or as distinct clusters (fluid-inclusion assemblages, FIAs) aligned along crystal growth zones, with no apparent relationship with healed fractures. Secondary inclusions were identified as those occurring in planar arrays that crosscut grain boundaries [41]. In sphalerite, primary inclusions are abundant. They commonly appear as isolated, two-phase (liquid–vapor, L-V) inclusions with elongated negative-crystal shapes (Figure 7a,b) or as tiny, subhedral inclusions with sharp triangular boundaries (Figure 7c). In fluorite, both primary and secondary inclusions were observed. Primary inclusions include large, two-phase (L-V) negative crystals (up to 50 µm in size; Figure 7d) and three-phase, solid-bearing (S + L + V) inclusions containing cubic daughter minerals, likely halite (Figure 7e). Secondary inclusions are prevalent, forming trails of two-phase (L-V) inclusions along healed microfractures that transect crystal boundaries (Figure 7f). In calcite, primary inclusions display diverse morphologies. These range from elongate and fusiform shapes (Figure 7g) to irregular forms (Figure 7h) and tabular, two-phase (L-V) inclusions arranged parallel to crystal growth lamellae (Figure 7i). Across all examined minerals, the two-phase (L-V) aqueous inclusions are liquid-rich, with the vapor bubble consistently occupying approximately 5 to 40 vol.% at room temperature. For this study, only the two-phase (L-V) primary and secondary inclusions were selected for microthermometric analysis, as they were the most abundant and suitable for systematic measurement.

Figure 7.

Microphotographs of fluid inclusions in samples from the Qingshan deposit. L-V fluid inclusions in Sp-1 (a–c). LV-type fluid inclusions in Fl-2 (d). LVS-type fluid inclusions in Fl2 (e). LV-type secondary fluid inclusion in Fl-2 (f). LV-type fluid inclusions in Cal-3 (g–i). Abbreviations: L = liquid; V = vapor; S = solid; Sp = sphalerite; Fl = fluorite; Cal = calcite.

5.2. Microthermometry

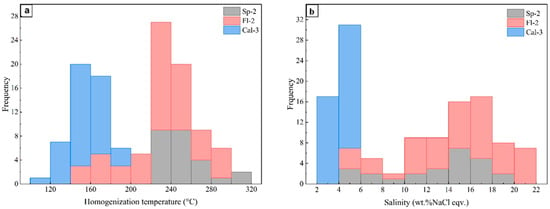

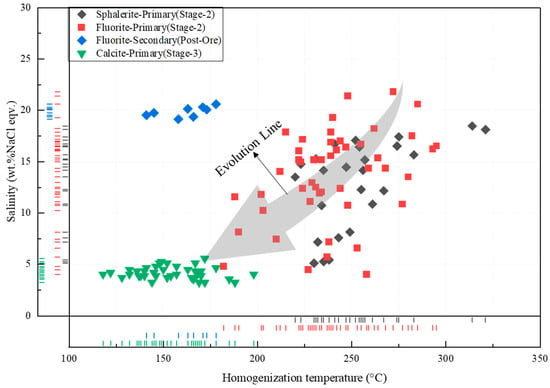

Microthermometric analyses were performed on primary fluid inclusions hosted in stage 2 sphalerite and fluorite, as well as stage 3 calcite. In addition, secondary inclusions in fluorite were analyzed to investigate later, post-ore fluids. A total of 121 inclusions were examined, with the results summarized in Table 1. Salinity values were determined using the HOKIE-FLINCS_H2O–NaCl spreadsheet [42]. Primary inclusions in stage 2 sphalerite (n = 25) exhibit homogenization temperatures (Th) ranging from 220 to 310 °C (Figure 8a), with salinities between 5.1 and 18.5 wt.% NaCl equivalent (Figure 8b). Stage 2 fluorite-hosted primary inclusions (n = 47) display Th values of 182–295 °C (Figure 8a), and salinities of 4.0–21.8 wt.% NaCl equivalent (Figure 8b). In contrast, secondary fluorite inclusions (n = 8) represent a later fluid phase, characterized by lower Th values of 141–178 °C (Figure 8a), and relatively high salinities of 19.1–20.6 wt.% NaCl equivalent (Figure 8b). Stage 3 calcite-hosted inclusions (n = 41) correspond to the coolest and most dilute fluids, with Th ranging from 118 °C to 198 °C (Figure 8a), and salinities of 3.2–5.6 wt.% NaCl equivalent (Figure 8b).

Table 1.

Summary of microthermometric data for fluid inclusions from stage 2 and stage 3.

Figure 8.

Histograms of homogenization temperatures (a) and salinities (b) of fluid inclusions from the Qingshan Pb–Zn deposit. Abbreviations: Sp = sphalerite; Fl = fluorite; Cal = calcite.

5.3. C–O Isotopic Composition

Carbon and oxygen isotopes from calcite separates associated with sulfide ores are compiled in Table 2. In total, 22 individual calcite crystals were analyzed. The carbon isotopic composition (δ13CV-PDB) of calcite crystals ranges from −8.6‰ to 2.1‰. The oxygen isotopic composition (δ18OV-PDB) ranges from −16.3‰ to −4.3‰. These δ18OV-PDB values were converted to δ18OV-SMOW values using the equation δ18OSMOW = 1.03086 × δ18OPDB + 30.86 [43], yielding a range of 14.1‰ to 26.5‰, respectively.

Table 2.

Carbon–oxygen isotope composition of calcite from the Qingshan deposit.

5.4. Sulfur Isotope Compositions

Sulfur isotope measurements were carried out on nine sulfide mineral samples—including three sphalerite, three pyrite, and three galena collected from the Qingshan Pb–Zn deposit (Table 3). The isotopic compositions are reported as δ34SV-CDT, exhibiting the following characteristics: Sphalerite from stages 1 to 3 shows a range of +16.12‰ to +18.29‰, with an average of +17.40‰. Pyrite from stage 1 to stage 3 ranges from +14.54‰ to +15.79, averaging +15.17, while galena from stage 1 to stage 3 displays a broader range from +8.56‰ to +17.01, with an average of +14.56. In this mineral assemblage, sphalerite exhibits the highest δ34S values, followed by pyrite, with galena showing the lowest values, suggesting complex sulfur source dynamics during mineralization.

Table 3.

S isotopic compositions of sulfides from the Qingshan deposit.

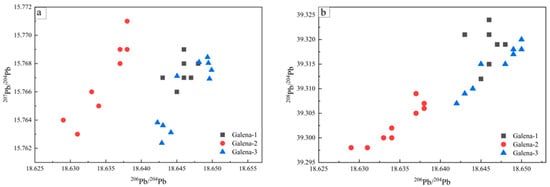

5.5. Lead Isotope Analyses

In situ lead isotope compositions determined by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (MC-ICP-MS) are compiled in Table 4. The galena samples from the study area exhibit a range of isotopic ratios for 206Pb/204Pb, 207Pb/204Pb, and 208Pb/204Pb. For stage 1 galena, the isotopic ratios vary from 18.643 to 18.648 for 206Pb/204Pb, 15.763 to 15.771 for 207Pb/204Pb, and 39.312 to 39.324 for 208Pb/204Pb. In stage 2 galena, the lead isotopic compositions are tightly constrained, with 206Pb/204Pb ranging from 18.629 to 18.638, 207Pb/204Pb from 15.761 to 15.770, and 208Pb/204Pb from 39.290 to 39.309, respectively. For stage 3 galena, the observed isotopic ratios range from 18.642 to 18.650 for 206Pb/204Pb, 15.762 to 15.768 for 207Pb/204Pb, and 39.307 to 39.320 for 208Pb/204Pb.

Table 4.

In situ Pb isotopic ratios of galena from the Qingshan deposit.

These results highlight the distinct isotopic compositions across the various galena stages, contributing valuable insights into the geochemical processes involved in mineralization and source contributions.

6. Discussion

6.1. Microthermometric Constraints on the Nature and Evolution of Ore-Forming Fluids

Carbonate-associated Pb–Zn deposits are an essential global source of lead and zinc, formed through the circulation of hydrothermal fluids within carbonate rock sequences [6]. Fluid inclusions record critical physicochemical parameters, temperature, salinity, pH, and redox conditions that control metal transport and precipitation [44,45]. Re-equilibration or leakage can overestimate homogenization temperatures (Th) [46]. Temperature variations reflect diverse geological environments, such as magmatic, basinal, and metamorphic, while deeper systems attain elevated salinities via evaporite dissolution, boiling, phase separation, and fluid–rock interaction, unlike near-surface seawater-dominated systems (3 wt.% NaCl) [47,48]. Microthermometric analyses of stage 2 sphalerite and fluorite, stage 3 calcite, and secondary fluorite inclusions reveal distinct temperature–salinity trends, constraining the multi-stage hydrothermal evolution at Qingshan.

Stage 2 primary fluid inclusions of sphalerite display homogenization temperatures (Th) of 220–310° C and salinities of 5.1–18.5 wt.% NaCl equivalent. Coeval stage 2 fluorite records Th = 182–295 °C and salinities of 4.0–21.8 wt.% NaCl equivalent. Overlap of Th and salinity between sphalerite and fluorite indicates near-synchronous precipitation from a homogeneous, moderately to highly saline fluid consistent with brines circulating at significant depth (Figure 9). Secondary fluorite inclusions define cooler Th (141–178 °C) but high salinities (19.1–20.6 wt.% NaCl equiv.), implying late-stage influxes of brines enriched by evaporite dissolution or fluid unmixing (Figure 9) [47,49]). Stage 3 calcite-hosted inclusions record waning conditions with Th = 118–198 °C and dilute salinities of 3.2–5.6 wt.% NaCl equiv., indicating progressive cooling and meteoric dilution during system closure (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Summary diagram showing the homogenization temperatures and salinities of fluid inclusions from various mineralization stages of the Qingshan Pb–Zn deposit.

This regional consistency suggests that Pb–Zn mineralization throughout the area originated from the migration of moderately hot, saline brines, accompanied by episodic thermal input from deeper crustal sources [48]. Although stage 2 inclusions plot within the brine field, their relatively high homogenization temperatures suggest a minor thermal contribution from deep sources. However, there is a spatial relationship between the Qingshan deposit and the Emeishan Large Igneous Province (ELIP), where basaltic magmatism (ca. 260 Ma) predates the main Pb–Zn mineralization (ca. 232–194 Ma) [22,50]. In contrast, secondary fluorite inclusions record cooler but highly saline fluids (Th = 141–178 °C; 19.1–20.6 wt.% NaCl equiv.), suggesting infiltration of brines enriched by evaporite dissolution or fluid unmixing [47,49]. Stage 3 calcite-hosted inclusions (Th = 118–198 °C; 3.2–5.6 wt.% NaCl equiv.) reflect progressive cooling and dilution through meteoric mixing [6]. Their low salinities, compared to other NW Guizhou Pb–Zn deposits (7–14 wt.% NaCl equiv.) [51], indicate enhanced late-stage dilution marking the final dissipative phase of hydrothermal circulation [44].

In summary, the fluid inclusion evidence from Qingshan reveals a multi-stage hydrothermal history. Ore precipitation during stage 2 was driven by moderately hot, saline brines, locally influenced by regional heat flow linked with possible thermal input from deep, fault-related hydrothermal fluids associated with tectonic activity. Subsequent overprinting by cooler but highly saline fluids indicate a later influx of evolved brines, while stage 3 reflects progressive cooling and dilution by meteoric waters. This evolutionary sequence underscores the dynamic interplay of deep-sourced fluids, tectono-thermal drivers, and surface mixing processes in controlling Pb–Zn mineralization in the SYGT.

Despite detailed petrographic screening of stage 1 sphalerite, no primary fluid inclusions suitable for microthermometry were found, likely due to absence, minute size, or post-entrapment re-equilibration. This limits direct estimates of early fluid temperature and salinity, an issue common in early carbonate-hosted Pb–Zn stages [40,52]. However, integrated evidence from stage 2 and stage 3 inclusions, together with C–O–S–Pb isotopic data, provides reliable constraints on fluid evolution and sources, partly compensating for this gap. Future application of techniques such as infrared microthermometry or LA-ICP-MS analysis of inclusions may refine early fluid characteristics. The following section focuses on carbon isotopes to further elucidate fluid pathways and carbon sources in the Qingshan mineralizing system.

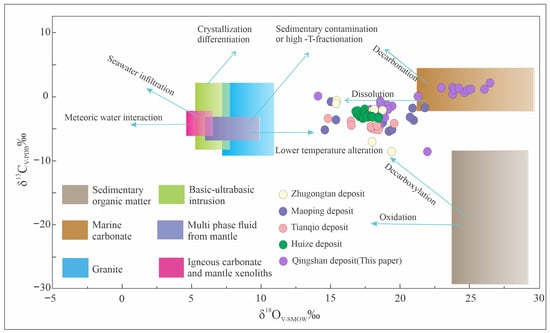

6.2. Sources of CO2

Newly obtained carbon and oxygen isotopic measurements performed on calcite separates associated with sulfide ores are compiled in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 10. Analysis of the δ13C and δ18O isotope signatures in ore-related minerals serve as key indicators for understanding the origin, fluid evolution, and formation mechanisms of ore systems [53].

Hydrothermal fluids derived from different reservoirs exhibit distinct C-O isotope signatures. Mantle-derived fluids typically show δ13CV_PDB values between −8 and −4‰ and δ18OV_SMOW values of +6‰ to +10‰ [54]. Fluids influenced by sedimentary organic matter are characterized by δ13CV-PDB values of −30‰ to −15‰ and δ18OV-SMOW values of +24‰ to +30‰ [55]. In contrast, fluids interacting with marine carbonate rocks generally display δ13CV-PDB values ranging from −4‰ to +4‰ and δ18OV-SMOW values of +20‰ to +30% [56]. These variations reflect the isotopic compositions of the fluid sources and provide constraints on fluid origin and evolution during ore formation.

The measured extensive range of δ13CV-PDB values (–8.60‰ to 2.10‰) and δ18OV-SMOW values (14.10‰ to 26.50‰) indicates a complex hydrothermal system that evolved through successive fluid pulses. As shown in the δ13CV-PDB versus δ18OV-SMOW diagram (Figure 10) and supported by the data in Table 2, these broad isotopic variations reflect mixing of multiple fluid reservoirs, each imparting a distinct isotopic signature, rather than derivation from a single uniform source.

In the δ13CV-PDB versus δ18OV-SMOW plot (Figure 10), calcite separates from the Qingshan deposit occupies isotopic fields intermediate between those characteristics of deep- sourced and marine carbonate rocks, positioned close to the range associated with sedimentary organic matter.

Figure 10.

Plot of δ13CV-PDB vs. δ18OV-SMOW values (modified from the work of Wang et al., 2014 [4]); data of the other deposits; Zhugongtang deposit [57], Maoping deposit [58,59], Tianqio deposit [60] and Huize deposit [61,62]. Colored squares/rectangles indicate isotopic end-member reservoirs, colored circles represent measured deposit values, and arrows show isotopic evolution pathways, with arrowheads indicating the direction of C–O change.

Despite this, the Pb–Zn mineralization in the SYGT area, dated at approximately ca. 232–194 Ma, occurred well after the emplacement of the Emeishan basalts (ca. 260 Ma) [22,50]. This temporal relationship suggests that there is no genetic connection between the Emeishan basalt and Pb–Zn mineralization [30,63].

A broad spectrum of δ13CV-PDB values in ore-stage calcites provides strong evidence for a mixed carbon origin. Positive values, up to 2.10‰, resemble those of marine carbonates (δ13CV-PDB = −4‰ to +4‰; [56]), consistent with dissolution of the marine carbonate strata hosting the deposit, which released CO2 enriched in 13C [55]. In contrast, negative values, down to −8.60‰, reflect input from a δ13C-depleted reservoir, most likely sedimentary organic matter [64], such as that in the Carboniferous strata at Qingshan. Although these values are less depleted than pure organic matter (−30‰ to −15‰; [55]), they indicate mixing of organic-derived carbon with heavier carbonate-derived carbon.

The wide range of δ18OV-SMOW values (14.10‰ to 26.50‰) complements the carbon isotope data, highlighting variations within the hydrothermal system. The upper range (21.3‰ to 26.50‰) corresponds to marine carbonate host rocks (δ18OV-SMOW = +20 to +30‰; [56], whereas lower values (down to 14.10‰) reflect 18O depletion caused by high-temperature fluid–rock interaction, where isotope exchange with lighter fluid reservoirs lowered the δ18O of precipitating calcite [55]. This depletion signals the involvement of deep-seated fluids contributing to the hydrothermal system.

Overall, integration of carbon and oxygen isotope data from ore-stage calcite at Qingshan reveals a multi-source hydrothermal system best explained by a ternary mixture model. On the δ13CV-PDB versus δ18OV-SMOW diagram (Figure 10), samples with positive δ13C and elevated δ18O values are grouped near the isotopic field characteristic of marine carbonates, reflecting the dominant contribution of host carbonate dissolution. In contrast, more negative δ13C values and depleted δ18O indicate additional inputs from sedimentary organic matter and deep-seated fluids. This isotopic interplay demonstrates that carbonate rocks provided the principal carbon reservoir, with organic matter and deeper fluids imparting secondary signatures through processes such as thermochemical sulfate reduction, CO2 degassing, and extensive fluid–rock exchange [55,65]. Such a mixed-source model is consistent with regional metallogenic patterns across the Sichuan–Yunnan–Guizhou Belt, such as those at Maoping [58] and Zhongontang [57] deposits, supporting a tectonically driven, homologous ore-forming system.

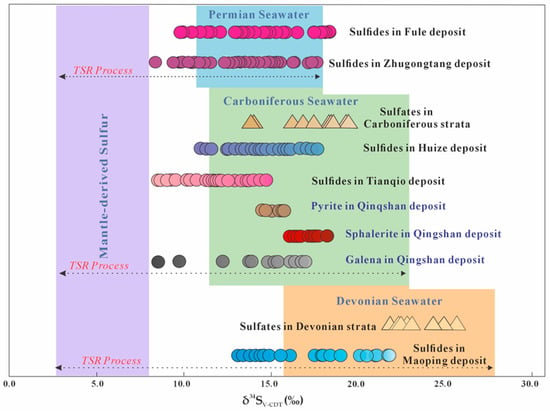

6.3. Sulfur Sources and Reduction Mechanism

The primary ores at the Qingshan Pb–Zn deposit consist predominantly of galena, sphalerite, and pyrite. The absence of sulfate minerals in these ores implies that the measured δ34S values of the sulfides closely reflect the sulfur isotopic composition of the ore-forming hydrothermal fluids [66,67]. The δ34S values obtained in this study are consistently positive, ranging from +16.12‰ to +18.29‰ in sphalerite, +14.54‰ to +15.79‰ in pyrite, and +8.56‰ to +17.01‰ in galena (Figure 11; Table 3). These relatively heavy δ34S values indicate that deep-sourced sulfur, which generally ranges around 0‰ ± 3% [68], was not the primary source, and they also suggest that bacterially reduced sulfur in sedimentary rocks did not contribute significantly.

Such heavy signatures exclude a dominant magmatic sulfur input, which generally ranges around 0‰ ± 3 [68]), and rule out bacterially reduced sulfur processes in sedimentary rocks, which commonly yield negative δ34S values [69]). Instead, the isotopic compositions strongly suggest derivation from marine sulfate reservoirs. This interpretation is consistent with Devonian–Permian seawater sulfates (+15‰ to +25; [67,70], and with evaporitic sulfates (barite +12‰ to +28; gypsum ~+15) documented in regional strata [4,5,61]. The heavy sulfur enrichment of the ore fluids, therefore, points to evaporites as the principal source of sulfur.

Although the absolute δ34S values are compatible with the reduction in sedimentary sulfate, the relative ordering of isotope enrichment among coexisting sulfides does not always follow equilibrium predictions. Theoretical models dictate δ34Spyrite > δ34Ssphalerite > δ34Sgalena under H2S-dominated equilibrium conditions [66]. However, the dataset includes instances where δ34Ssphalerite exceeds δ34Spyrite, and galena shows a wider range. Such reversals indicate partial isotopic disequilibrium during the precipitation of ores. The broader spread in galena compared to the narrower ranges in pyrite and sphalerite may also reflect episodic precipitation under dynamic fluid conditions. The persistently heavy δ34S values provide additional constraints on the sulfate reduction process. Marine sulfate can be reduced through either bacterial sulfate reduction (BSR) or thermochemical sulfate reduction (TSR) [71].

Figure 11.

Comparison of Sulfur isotopic compositions of sulfides, sulfates, mantle derived sulfur and seawater among the Pb–Zn deposits hosted in the different strata in the SYG metallogenic province. Sulfur isotopic data sources: Fule deposit [72], Zhugongtang deposit [57], Huize deposit [73], Tianqiao deposit [60], Maoping deposit [58], sulfates in the Carboniferous and Devonian strata [74]), seawater in different ages [70] and mantle-derived sulfur [68].

Bacterial sulfate reduction (BSR), operative below 110 °C, produces large isotopic fractionations (15‰–66‰) and typically results in light or negative δ34S values [75,76]. Given the mineralization temperatures at Qingshan (118 °C–310 °C; average 155 °C–252 °C), bacterial activity can be excluded. In contrast, TSR occurs at a higher temperature (>120) °C and generates reduced sulfur with δ34S values only slightly lower than the parent sulfate, thereby preserving the heavy isotopic character [71]. The positive δ34S values at Qingshan (+8.56‰ to +18.29‰) are therefore best explained by thermochemical sulfate reduction (TSR).

In summary, sulfur isotope systematics from the Qingshan deposit confirm evaporitic sulfate as the primary source of sulfur and highlight the contribution of TSR to the reduction in sulfate. The presence of partial isotopic disequilibrium further indicates dynamic ore-forming conditions, distinguishing Qingshan from other deposits where equilibrium fractionation has been more completely preserved.

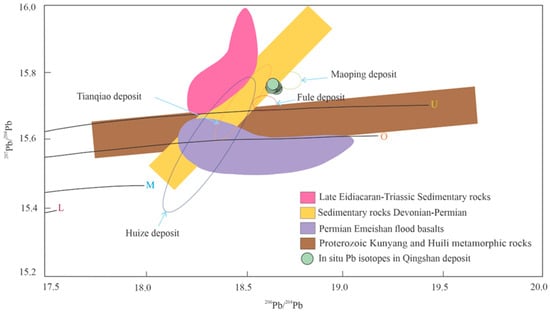

6.4. Metal Sources

Lead isotopic signatures in galena serve as reliable tracers of metal sources in hydrothermal deposits, as the exceedingly low U and Th contents in galena preclude significant radiogenic Pb ingrowth, thereby preserving the original Pb isotopic composition of the ore-forming fluids [77]. The source of ore-forming components in the Qingshan deposit, along with neighboring and genetically related occurrences, remains a topic of discussion. Earlier investigations in the SYGT [78] and references cited therein have identified three main potential reservoirs contributing to Pb–Zn mineralization in the SYGT: (1) the metamorphic basement (Kunyang and Huili Groups), (2) the overlying Devonian–Permian carbonate sequences, and (3) the late Permian volcanic rocks associated with the Emeishan Large Igneous Province (ELIP).

In situ galena Pb isotopes define three mineralization stages. Stage 1 displays tightly grouped isotopic ratios, with 206Pb/204Pb values ranging from 18.643 to 18.648, 207Pb/204Pb between 15.763 and 15.771, and 208Pb/204Pb from 39.312 to 39.324. Stage 2 is characterized by slightly less radiogenic 206Pb/204Pb values (18.629–18.638) while maintaining comparable 207Pb/204Pb (15.761–15.770) and 208Pb/204Pb (39.298–39.309) ratios. Stage 3 largely overlaps stage 1 but extends to higher 206Pb/204Pb (18.642–18.650). The stage 2 shift likely reflects a temporary increase in basement contributions before fluids returned to upper-crustal reservoirs in stage 3.

The Pb isotopic compositions of galena from the Qingshan deposit, as shown in the 207Pb/204Pb–206Pb/204Pb and 206Pb/204Pb–208Pb/204Pb (Figure 12a,b) diagrams, collectively indicate a mixed lead source that evolved during mineralization. In the 207Pb/204Pb versus 206Pb/204Pb diagram (Figure 13), galena data plot away from the isotopic fields of individual potential source rocks and cluster along or slightly above the upper continental crust (UCC) evolution curve [79], exhibiting a distinctly radiogenic signature. At comparable 206Pb/204Pb ratios, the galena shows higher 207Pb/204Pb values than both the ELIP basalts and the basement. The isotopic compositions lie within the range of Devonian–Permian carbonate rocks and approach those of the underlying metamorphic basement on the plots of 207Pb/204Pb versus 206Pb/204Pb (Figure 13) while remaining clearly distinct from the ELIP basalts and Sinian Dengying dolostone. These relationships suggest that the lead was derived mainly from upper-crustal carbonate strata, with subordinate basement input, and that the slightly radiogenic nature of the Pb reflects an upper-crustal reservoir influenced by the regional metallogenic processes [79,80].

Figure 12.

Diagrams of 207Pb/204Pb vs. 206Pb/204Pb (a) and 208Pb/204Pb vs. 206Pb/204Pb (b), showing three mineralization stages with distinct isotopic ratios from galena-I (early stage) to galena-II (main stage) and galena-III (late stage).

Figure 13.

Plots of 207Pb/204Pb versus 206Pb/204Pb ratios of galena from the Qingshan Pb–Zn deposit. Isotopic fields are modified after Zartman and Doe (1981) [79]. Data sources: Maoping deposit [58], Fule deposit [72], Tianqiao deposit [60], Huize deposit [81], Devonian–Permian carbonate rocks, Sinian Dengying Formation dolostone, basement rocks of the Kunyang and Huili Groups, and Emeishan flood basalts [81]. Abbreviations: Upper Crust (U), Orogenic Belt (O), Mantle (M) and Lower Crust (L).

In summary, Pb isotope data from Qingshan galena indicate derivation mainly through leaching of Devonian–Permian carbonate rocks, supplemented by inputs from Proterozoic basement units. The homogenized and radiogenic isotopic signature is characteristic of metals mobilized by deep-seated hydrothermal fluids, such brines, capable of extracting Pb from crustal reservoirs. Thus, the ore-forming system is best explained by a mixed-source model, dominated by upper-crustal sedimentary cover rocks with secondary contributions from Proterozoic basement.

6.5. Proposed Metallogenic Model and Implications for Ore Exploration

The Qingshan Pb–Zn deposit, located in northwestern Guizhou, represents a characteristic example of lead–zinc mineralization within the Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou (SYGT) area, resulting from the combined effects of tectono-thermal processes due to deep faulting, hydrothermal circulation, and crustal metal–sulfur sources, while the Qingshan deposit is hosted in carbonate sequences typical of an MVT system. The Qingshan deposit demonstrates multiple pivotal divergences from MVT criteria and exhibits a strong alignment with HZT diagnostic features. Structurally, mineralization was localized along an intracontinental strike–slip fault system in a compressional regime during the Late Indosinian to Early Yanshanian [19], contrasting with the extensional basin settings typical of MVT deposits [6]. This compressional, intracontinental strike–slip fault system is the hallmark of Huize-style deposits in the SYGT area [2]. The Qingshan Pb–Zn deposit is spatially associated with the Emeishan Large Igneous Province (ELIP) [81] (Figure 1B). The eruption of the Emeishan basalts is well constrained at 259 ± 3 Ma [30], whereas Pb–Zn mineralization across the SYG province occurred between ca. 232 and 194 Ma [22,50], leading it to contrasting with classical MVT deposits that lack magmatic influence [6]. Notably, the deposit’s Pb + Zn grades are over 30 wt.%, significantly exceeding the range typical of MVT deposits (<10 wt.%) [6], and consistent with HZT ores (averaging 15%–35%) [2], while ore-fluid homogenization temperatures of 118–310 °C are significantly higher than typical MVT temperatures (90–150 °C) [82]. The Qingshan thermal range is consistent with the higher temperature’s characteristic of HZT-style deposits (183–355 °C) [2]. However, the salinity (3.2–21.8 wt.% NaCl equiv.) spans intermediate values. Isotopically, ore-stage calcite exhibits δ13C values from −8.60‰ to +2.10‰, indicative of mixed, carbonate, organic, and deep-seated carbon sources, which is consistent with the general complexity observed across HZT systems in the SYGT, unlike the simpler, marine carbonate signatures of MVT deposits [6,83]. The positive δ34S values in Qingshan (+8.56‰ to +18.29‰) indicate TSR-derived evaporitic sulfate, consistent with HZT-type deposits (+5‰ to +15‰) and contrasting with the broader seawater–sulfate range of MVT systems (+10–+25‰,) [6,83]. Furthermore, Qingshan’s Pb isotopes plot along upper-crustal trends, consistent with the HZT model where metals mainly derive from the Proterozoic basement [2]. Collectively, the structural ore-controlling laws, fluid inclusion, and isotopic characteristics firmly establish the Qingshan deposit as a Huize-type (HZT) carbonate-hosted Zn–Pb system, exhibiting strong metallogenic affinity with the Huize, Maoping, Zhugongtang, and Tianbaoshan, along with other Pb–Zn deposits within the SYGT area.

The proposed model suggests that Pb–Zn mineralization in the Qingshan deposit was driven by low- to moderate-temperature (118 °C–310 °C), variably saline (3.2–21.8 wt.% NaCl equiv.) hydrothermal brines that ascended along NW-trending strike–slip faults under a compressional regime. These deep-sourced fluids, modified by meteoric and organic interactions, leached metals from the Devonian–Permian carbonates and the Proterozoic basement, as shown by Pb isotopes plotting along upper-crustal trends. Positive δ34SV_CDT values (+8.56‰ to +18.29‰) and fluid temperatures above 120 °C indicate sulfur derived from evaporitic sulfate reduced via thermochemical sulfate reduction (TSR); partial isotopic disequilibrium among coexisting sulfides, indicates fluid mixing during ore deposition, while the wide δ13CV_PDB range (–8.60‰ to +2.10‰) in ore-stage calcite reflects mixing of carbonate, organic, and deep-seated fluids. Ore precipitation was driven by cooling, depressurization, and fluid mixing between metal-rich and H2S-bearing solutions within dolomitized carbonate hosts, forming high-grade sphalerite–galena assemblages. This HZT-type model highlights the interplay of structurally focused deep-sourced brines and TSR-mediated sulfur reduction, providing a predictive framework for Pb–Zn exploration in fault-controlled carbonate–evaporite systems of the SYGT area.

7. Conclusions

- The Qingshan Pb–Zn deposit, hosted within Upper Carboniferous carbonate rocks of the Maping Formation, formed through a multi-stage hydrothermal system linked to deep-fault controlled tectono-thermal reactivation in the SYGT area. The ore-forming fluids (118–310 °C; 3.2–21.8 wt.% NaCl equiv.) were dominantly deep-sourced brines, locally influenced by elevated regional heat flow and possible thermal input related to fault reactivation during the Indosinian orogeny.

- Ore-stage calcite δ13CV_PDB (−8.60‰ to +2.10‰) and δ18OV_SMOW (14.10‰ to 26.50‰) indicate mixed carbon derived predominantly from marine carbonates, with additional contributions from organic matter, and deep-sourced fluids, reflecting carbonate dissolution and thermochemical sulfate reduction (TSR) during fluid–rock interaction.

- Positive δ34SV_CDT values (+8.56‰ to +18.29‰), together with fluid temperatures >120 °C, indicate evaporitic sulfate as the principal sulfur source, reduced by thermochemical sulfate reduction (TSR). The heavy sulfur signature, coupled with partial isotopic disequilibrium among coexisting sulfides, indicates dynamic physicochemical conditions involving fluid mixing during ore deposition.

- Lead isotopic compositions demonstrate that metals were leached primarily from Devonian–Permian carbonate strata, with subordinate contributions from the Proterozoic basement.

- The Qingshan Pb–Zn deposit is genetically consistent with HZT-type, carbonate-hosted Pb–Zn deposit.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A. and R.H.; methodology, J.A., R.H. and Y.Z.; software, J.A., Y.C. and L.W. validation, R.H. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, J.A., R.H. and L.W.; investigation, J.A. and R.H.; resources, R.H. and Y.Z.; data curation, J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.; writing—review and editing, R.H.; visualization, J.A.; supervision, R.H. and Y.Z.; project administration, R.H. and Y.Z.; funding acquisition, R.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Foundation of China (Nos. 42172086, 42472127 and 41572060), the deep and peripheral prospecting of the Hongqiao Qingshan-Shuangfeng Hengtang area in Guizhou Province (2023530103001927), the Yunnan Major Scientific and Technological Projects (No. 202202AG050014-01), the Program of Yunling Scholar of Yunnan Province (2014), and the Innovation Team of Yunnan Province and Kunming University of Science and Technology (2012, 2008), and the APC was funded by the Projects of YM Lab (2012).

Data Availability Statement

The authors agree to make data supporting the results or analyses presented in this paper available upon reasonable request from the first author and corresponding authors due to the internal policy.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Zhi He, a staff member of Guizhou Hongqiao Mining Industry, for his help in field work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, Y.; Han, R.-S.; Ding, X.; Wang, Y.-R.; Wei, P.-T. Experimental Study on Fluid Migration Mechanism Related to Pb–Zn Super-Enrichment: Implications for Mineralisation Mechanisms of the Pb–Zn Deposits in the Sichuan–Yunnan–Guizhou, SW China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2019, 114, 103110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.S.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, W.L.; Ding, T.Z.; Wang, M.Z.; Wang, F. Geology and Geochemistry of Zn-Pb(-Ge-Ag) Deposits in the Sichuan-Yunnan-Guizhou Triangle Area, China: A Review and a New Type. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1136397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.S.; Hu, Y.Z.; Wang, X.K.; Hou, B.H.; Huang, Z.L.; Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Wu, P.; Li, B.; Wang, H.J. Mineralization Model of Rich Ge-Ag-Bearing Zn-Pb Polymetallic Deposit Concentrated District in Northeastern Yunnan, China. Acta Geol. Sin. 2012, 86, 294, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Deng, J.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Lai, X. Nature, Diversity and Temporal–Spatial Distributions of Sediment-Hosted Pb―Zn Deposits in China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2014, 56, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.C.; Lin, W.D. Regularity Research of Lead-Zinc-Silver Deposits in Northeastern Yunnan Province; Yunnan University Press: Kunming, China, 1999; pp. 1–468. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Leach, D.L.; Bradley, D.C.; Huston, D.; Pisarevsky, S.A.; Taylor, R.D.; Gardoll, S.J. Sediment-Hosted Lead-Zinc Deposits in Earth History. Econ. Geol. 2010, 105, 593–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Q.; Xu, J.J.; Mao, J.W.; Rui, Z.Y. Advances in the Study of Mississippi Valley-Type Deposits. Miner. Depos. 2009, 28, 195–210, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, D.C.; Leach, D.L. Tectonic Controls of Mississippi Valley-Type lead–zinc Mineralization in Orogenic Forelands. Miner. Depos. 2003, 38, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, D.L.; Rowan, E.L. Genetic Link between Ouachita Foldbelt Tectonism and the Mississippi Valley–Type Lead-Zinc Deposits of the Ozarks. Geology 1986, 14, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.J.; Weiss, D.J.; Mason, T.; Coles, B.J. Zinc Isotope Variation in Hydrothermal Systems: Preliminary Evidence from the Irish Midlands Ore Field. Econ. Geol. 2005, 100, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmihelsky, M.; Steele-MacInnis, M.; Bain, W.M.; Falck, H.; Adair, R.; Campbell, B.; Dufrane, S.A.; Went, A.; Corlett, H.J. Mixing of Brine with Oil Triggered Sphalerite Deposition at Pine Point, Northwest Territories, Canada. Geology 2020, 49, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.J.; Stoffell, B.; Wilkinson, C.C.; Jeffries, T.E.; Appold, M.S. Anomalously Metal-Rich Fluids Form Hydrothermal Ore Deposits. Science 2009, 323, 764–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, Y.; Hou, L.; Mao, J. Geodynamic Setting of Mineralization of Mississippi Valley-Type Deposits in World-Class Sichuan–Yunnan–Guizhou Zn–Pb Triangle, Southwest China: Implications from Age-Dating Studies in the Past Decade and the Sm–Nd Age of Jinshachang Deposit. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 103, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, C.Y.; Li, Z.Q.; Li, B.H.; Liu, W.Z. The Comparison of Mississippi Valley-Type Lead-Zinc Deposits in Southwest of China and in Mid-Continent of United States. BMPG 2002, 21, 127–132, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.Q.; Mao, J.; Wu, S.P.; Li, H.M.; Liu, F.; Guo, B.J.; Gao, D.R. Distribution, Characteristics and Genesis of Mississippi Valley-Type Lead-Zinc Deposits in Sichuan-Yunnan-Guizhou Area. Miner. Depos. 2005, 24, 336–348, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Han, R.S.; Wang, F.; Hu, Y.Z.; Wang, X.K.; Ren, T.; Qiu, W.L.; Zhong, K.H. Metallogenic Tectonic Dynamics and Chronology Constrains on the Huize-Type (HZT) Germanium-Rich Silver-Zinc-Lead Deposits. Geotecton. Metallog. 2014, 38, 759–771, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Han, R.S.; Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, X.K.; Li, Y. Analysis of Metal-Element Association Halos within Fault Zones for the Exploration of Concealed Ore-Bodies—A Case Study of the Qilinchang Zn-Pb-(Ag-Ge) Deposit in the Huize Mine District, Northeastern Yunnan, China. J. Geochem. Explor. 2015, 159, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, Z.L.; Zhu, D.; Luo, T.Y. Origin of Hydrothermal Deposits Related to the Emeishan Magmatism. Ore Geol. Rev. 2014, 63, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Wu, P.; Qiu, W.L.; Li, W.Y. Metallogenic Mechanism of Germanium Rich Lead-Zinc Deposits and Prediction of Concealed Ore Location in Northeast Yunnan; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2019; p. 501. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, R.S.; Wang, M.Z.; Jing, Z.G.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.Y. Ore-Controlling Mechanism of NE-Trending Ore-Forming Structural System at Zn-Pb Polymetallic Ore Concentration Area in Northwestern Guizhou. Acta Geol. Sin. 2020, 94, 850–868, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- John, B.M.; Zhou, X.H.; Li, J.L. Formation and Tectonic Evolution of Southeastern China and Taiwan: Isotopic and Geochemical Constraints. Tectonophysics 1990, 183, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Fu, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, M.-F.; Fu, S.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Bi, X.; Xiao, J. The Giant South China Mesozoic Low-Temperature Metallogenic Domain: Reviews and a New Geodynamic Model. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2017, 137, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Jiang, S.-Y.; Xiong, S.-F.; Hou, J.-J. Ore-Forming Processes of Giant Carbonate-Hosted Zn Pb Deposit and Ge Enrichment Mechanism in Zhugongtang, Guizhou Province, China: Constraints from Trace Element and Isotopic Compositions of Sulfides. J. Geochem. Explor. 2025, 270, 107666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.S.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.L.; Wang, F.; Jin, Z.G.; Zhou, G.M.; Shi, Z.L.; Zhang, C.Q. New Research Progresses of Metallogenic Theory for Rich Zn-Pb-(Ag-Ge) Deposits in the Sichuan-Yunnan-Guizhou Triangle (SYGT) Area, Southwestern Tethys. Acta Geol. Sin. 2022, 96, 554–573, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y.M.; Gao, S.; McNaughton, N.J.; Groves, D.I.; Ling, W.L. First Evidence of > 3.2 Ga Continental Crust in the Yangtze Craton of South China and Its Implications for Archean Crustal Evolution and Phanerozoic Tectonics. Geology 2000, 28, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Yang, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, M.; Hu, Z.; Guo, J.; Yuan, H.; Gong, H.; Xiao, G.; Wei, J. Age and Growth of the Archean Kongling Terrain, South China, with Emphasis on 3.3 Ga Granitoid Gneisses. Am. J. Sci. 2011, 311, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.F.; Zhou, M.F.; Li, J.W.; Sun, M.; Gao, J.F.; Sun, W.H.; Yang, J.H. Late Paleoproterozoic to Early Mesoproterozoic Dongchuan Group in Yunnan, SW China: Implications for Tectonic Evolution of the Yangtze Block. Precambrian Res. 2010, 182, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.H.; Zhou, M.F.; Yan, D.P.; Li, J.W.; Ma, Y.X. Provenance and Tectonic Setting of the Neoproterozoic Yanbian Group, Western Yangtze Block (SW China). Precambrian Res. 2008, 167, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; Yu, J.H.; Griffin, W.L.; O’Reilly, S.Y. Early Crustal Evolution in the Western Yangtze Block: Evidence from U-Pb and Lu-Hf Isotopes on Detrital Zircons from Sedimentary Rocks. Precambrian Res. 2012, 222, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.-F.; Malpas, J.; Song, X.-Y.; Robinson, P.T.; Sun, M.; Kennedy, A.K.; Lesher, C.M.; Keays, R.R. A Temporal Link between the Emeishan Large Igneous Province (SW China) and the End-Guadalupian Mass Extinction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2002, 196, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.G. Ore-Controlling Factors, Metallogenic Rules and Prospecting Prediction of Lead and Zinc Deposits in Northwest Guizhou; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, D.H.; Han, R.S.; Wang, F.; Wang, M.Z.; He, Z.; Zhou, W.; Luo, D. Structural Ore−controlling Mechanism of the Qingshan Lead−zinc Deposit in Northwestern Guizhou, China and Its Implications for Deep Prospecting. Geol. China 2024, 51, 399–425. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Han, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, L. Indication of REEs, Fe, and Mn Composition Typomorphism of Calcite in Metallogenic Fracture Zones with Respect to Local Tectonic Stress Fields: A Case Study of the Qingshan Lead–Zinc Deposit in Northwest Guizhou, China. Minerals 2025, 15, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, R.J. Revised Equation and Table for Determining the Freezing Point Depression of H2O-Nacl Solutions. Geochim. Et Cosmochim. Acta 1993, 57, 683–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrea, J.M. On the Isotopic Chemistry of Carbonates and a Paleotemperature Scale. J. Chem. Phys. 1950, 18, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, K.; Bao, Z.; Liang, P.; Sun, T.; Yuan, H. Preparation of Standards for in Situ Sulfur Isotope Measurement in Sulfides Using Femtosecond Laser Ablation MC-ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2017, 32, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Chen, L.; Zong, C.; Yuan, H.; Chen, K.; Dai, M. Development of Pressed Sulfide Powder Tablets for in Situ Sulfur and Lead Isotope Measurement Using LA-MC-ICP-MS. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2017, 421, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Bao, Z.; Chen, K.; Zong, C.; Li, X.-C.; Qiu, J.W. Simultaneous Measurement of Sulfur and Lead Isotopes in Sulfides Using Nanosecond Laser Ablation Coupled with Two Multi-Collector Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometers. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2018, 154, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Yin, C.; Liu, X.; Chen, K.; Bao, Z.; Zong, C.; Dai, M.; Lai, S.; Wang, R.; Jiang, S. High Precision In-Situ Pb Isotopic Analysis of Sulfide Minerals by Femtosecond Laser Ablation Multi-Collector Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2015, 58, 1713–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roedder, E. Fluid inclusions. Rev. Mineral. 1984, 12, 644. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, G.; Haid, T.; Quirt, D.; Fayek, M.; Blamey, N.; Chu, H. Petrography, Fluid Inclusion Analysis, and Geochronology of the End Uranium Deposit, Kiggavik, Nunavut, Canada. Min. Depos. 2017, 52, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele-MacInnis, M.; Lecumberri-Sanchez, P.; Bodnar, R.J. HokieFlincs_H2O-NaCl: A Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet for Interpreting Microthermometric Data from Fluid Inclusions Based on the PVTX Properties of H 2 O–NaCl. Comput. Geosci. 2012, 49, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbeck, A.; Galler, P.; Bonta, M.; Bauer, G.; Nischkauer, W.; Vanhaecke, F. Recent Advances in Quantitative LA-ICP-MS Analysis: Challenges and Solutions in the Life Sciences and Environmental Chemistry. Anal Bioanal Chem 2015, 407, 6593–6617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, D.R.; Bull, S.W.; Large, R.R.; McGoldrick, P.J. The Importance of Oxidized Brines for the Formation of Australian Proterozoic Stratiform Sediment-Hosted Pb–Zn (Sedex) Deposits. Econ. Geol. 2000, 95, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, F.G.; Both, R.A.; Mangas, J.; Arribas, A. Metallogenesis of Zn-Pb Carbonate-Hosted Mineralization in the Southeastern Region of the Picos de Europa (Central Northern Spain) Province: Geologic, Fluid Inclusion, and Stable Isotope Studies. Econ. Geol. 2000, 95, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burruss, R.C. Diagenetic Palaeotemperatures from Aqueous Fluid Inclusions: Re-Equilibration of Inclusions in Carbonate Cements by Burial Heating. Mineral. Mag. 1987, 51, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, R.J.; Sterner, S.M. Synthetic Fluid Inclusions in Natural Quartz. II. Application to PVT Studies. Geochim. Et Cosmochim. Acta 1985, 49, 1855–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardley, B.W.D.; Graham, J.T. The Origins of Salinity in Metamorphic Fluids. Geofluids 2002, 2, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanor, J.S. Origin of Saline Fluids in Sedimentary Basins. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1994, 78, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-X.; Xiang, Z.-Z.; Zhou, M.-F.; Feng, Y.-X.; Luo, K.; Huang, Z.-L.; Wu, T. The Giant Upper Yangtze Pb–Zn Province in SW China: Reviews, New Advances and a New Genetic Model. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2018, 154, 280–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Xiong, S.-F.; Jiang, S.-Y. Genesis of Pb–Zn Deposits in Northwestern Guizhou Province of China: Constraints from the in Situ Analyses of Fluid Inclusions and Sulfur Isotopes. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 164, 105842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, R.J. Reequilibration of Fluid Inclusions. In Fluid Inclusions: Analysis and Interpretation; Mineralogical Association of Canada Short Course; Samson, I., Anderson, A., Marshall, D., Eds.; 2003; Volume 32, pp. 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wu, G.; Liu, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, D.; Mao, Z. Fluid Inclusions and Isotopic Characteristics of the Jiawula Pb–Zn–Ag Deposit, Inner Mongolia, China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 103, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.P.; Frechen, J.; Degens, E.T. Oxygen and Carbon Isotope Studies of Carbonatites from the Laacher See District, West Germany and the Alnö District, Sweden. Geochim. Et Cosmochim. Acta 1967, 31, 407–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefs, J. Stable Isotope Geochemistry, 6th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veizer, J.; Hoefs, J. The Nature of O18/O16 and C13/C12 Secular Trends in Sedimentary Carbonate Rocks. Geochim. Et Cosmochim. Acta 1976, 40, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, L.-L.; Yang, K.-G.; Ali, P.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, P.; Wu, D.-W.; Wang, J.; Cai, J.-C. Constraints of C H O S Pb Isotopes and Fluid Inclusions on the Origin of the Giant Zhugongtang Carbonate-Hosted Pb–Zn Deposit in South China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 151, 105192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wu, T.; Huang, Z.; Ye, L.; Deng, P.; Xiang, Z. Genesis of the Maoping Carbonate-Hosted Pb–Zn Deposit, Northeastern Yunnan Province, China: Evidences from Geology and C–O–S–Pb Isotopes. Acta Geochim. 2020, 39, 782–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.S.; Zou, H.J.; Hu, B.; Hu, Y.Z. Features of Fluid Inclusions and Sources of Ore-Forming Fluid in the Maoping Carbonate-Hosted Zn-Pb-(Ag-Ge) Deposit, Yunnan, China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2007, 23, 2109–2118, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, M.; Li, X.; Jin, Z. Constraints of C–O–S–Pb Isotope Compositions and Rb–Sr Isotopic Age on the Origin of the Tianqiao Carbonate-Hosted Pb–Zn Deposit, SW China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2013, 53, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.-S.; Liu, C.-Q.; Huang, Z.-L.; Chen, J.; Ma, D.-Y.; Lei, L.; Ma, G.-S. Geological Features and Origin of the Huize Carbonate-Hosted Zn–Pb–(Ag) District, Yunnan, South China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2007, 31, 360–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhou, M.; Li, W.; Jin, Z. REE and C-O Isotopic Geochemistry of Calcites from the World-Class Huize Pb–Zn Deposits, Yunnan, China: Implications for the Ore Genesis. Acta Geol. Sin.-Engl. Ed. 2010, 84, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, W.H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.J. Formation of Pb–Zn Deposits in the Sichuan-Yunnan-Guizhou Triangle Linked to the Youjiang Foreland Basin: Evidence from Rb-Sr Age and in Situ Sulfur Isotope Analysis of the Maoping Pb–Zn Deposit in Northeastern Yunnan Province, Southeast China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2019, 107, 780–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kump, L.R.; Arthur, M.A. Interpreting Carbon-Isotope Excursions: Carbonates and Organic Matter. Chem. Geol. 1999, 161, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaway, T.L.; Wicks, F.J.; Bryndzia, L.T.; Kyser, T.K.; Spooner, E.T.C. Formation of the Muzo Hydrothermal Emerald Deposit in Colombia. Nature 1994, 369, 552–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmoto, H.; Goldhaber, M.B. Sulfur and Carbon Isotopes. In Geochemistry of Hydrothermal Ore Deposits, 3rd ed.; Barnes, H.L., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 517–611. [Google Scholar]

- Seal, R.R., II. Sulfur Isotope Geochemistry of Sulfide Minerals. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2006, 61, 633–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaussidon, M.; Albarède, F.; Sheppard, S.M.F. Sulphur Isotope Variations in the Mantle from Ion Microprobe Analyses of Micro-Sulphide Inclusions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1989, 92, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollinson, H.R. Using Geochemical Data: Evaluation, Presentation, Interpretation; Longman Scientific & Technical: London, UK, 1993; pp. 306–308. [Google Scholar]

- Claypool, G.E.; Holser, W.T.; Kaplan, I.R.; Sakai, H.; Zak, I. The Age Curves of Sulfur and Oxygen Isotopes in Marine Sulfate and Their Mutual Interpretation. Chem. Geol. 1980, 28, 199–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machel, H.G. Bacterial and Thermochemical Sulfate Reduction in Diagenetic Settings—Old and New Insights. Sediment. Geol. 2001, 140, 143–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-X.; Luo, K.; Wang, X.-C.; Wilde, S.A.; Wu, T.; Huang, Z.-L.; Cui, Y.-L.; Zhao, J.-X. Ore Genesis of the Fule Pb Zn Deposit and Its Relationship with the Emeishan Large Igneous Province: Evidence from Mineralogy, Bulk C O S and in Situ S Pb Isotopes. Gondwana Res. 2018, 54, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.B.; Huang, Z.L.; Li, W.B.; Zhang, Z.L.; Yan, Z.F. Sulfur Isotopic Compositions of the Huize Super-Large Pb–Zn Deposit, Yunnan Province, China: Implications for the Source of Sulfur in the Ore-Forming Fluids. J. Geochem. Explor. 2006, 89, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.L.; Li, Y.H.; Zeng, P.S.; Qiu, W.L.; Fan, C.F.; Hu, G.Y. Effect of Sulfate Evaporate Salt Layer in Mineralization of the Huize and Maoping Lead-Zinc Deposits in Yunnan: Evidence from Sulfur Isotope. Acta Geol. Sin. 2018, 92, 1041–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Machel, H.G. Relationships between Sulphate Reduction and Oxidation of Organic Compounds to Carbonate Diagenesis, Hydrocarbon Accumulations, Salt Domes, and Metal Sulphide Deposits. Carbonates Evaporites 1989, 4, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, B.B.; Isaksen, M.F.; Jannasch, H.W. Bacterial Sulfate Reduction Above 100 °C in Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent Sediments. Science 1992, 258, 1756–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, G.R.; Dean, J.A.; Suppel, D.W.; Heithersay, P.S. Precise Lead Isotope Fingerprinting of Hydrothermal Activity Associated with Ordovician to Carboniferous Metallogenic Events in the Lachlan Fold Belt of New South Wales. Econ. Geol. 1995, 90, 1467–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liang, T.; Zhang, F.; Meng, X.; Lu, L.; Yang, G. Sources of Ore-Forming Material for Pb–Zn Deposits in the Sichuan-Yunnan-Guizhou Triangle Area: Multiple Constraints from C-H-O-S-Pb-Sr Isotopic Compositions. Geol. J. 2018, 53, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zartman, R.E.; Doe, B.R. Plumbotectonics—The Model. Tectonophysics 1981, 75, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shellnutt, J.G. The Emeishan Large Igneous Province: A Synthesis. Geosci. Front. 2014, 5, 369–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.L.; Chen, J.; Han, R.S.; Li, W.B.; Liu, C.Q.; Zhang, Z.L.; Ma, D.Y.; Gao, D.R.; Yang, H.L. Geochemistry and Ore-Formation of the Huize Giant Lead-Zinc Deposit, Yunnan Province, China: Discussion on the Relationship between the Emeishan Flood Basalts and Lead–Zinc Mineralization; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2004; pp. 1–204. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Basuki, N.I. A Review of Fluid Inclusion Temperatures and Salinities in Mississippi Valley-Type Zn-Pb Deposits: Identifying Thresholds for Metal Transport. Explor. Min. Geol. 2002, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, D.L.; Sangster, D.F.; Kelley, K.D.; Large, R.R.; Garven, G.; Allen, C.R.; Gutzmer, J.; Walters, S. Sediment-hosted lead-zinc deposits: A global perspective. Econ. Geol. 2005, 561–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.