Abstract

Shale pores and throats are key factors controlling the enrichment and development efficiency of shale oil and gas. However, the characteristics and formation mechanisms of shale pores and throats remain unclear. Taking the Permian continental shales in the Mahu Sag of the Junggar Basin as an example, this paper studies the formation mechanisms of pores and throats in shales of different lithofacies through a series of experiments, such as high-pressure mercury injection and scanning electron microscopy. The results show that the Permian continental shales in the Junggar Basin are mainly composed of five lithofacies: rich siliceous shale (RSS), calcareous–siliceous shale (CSS), argillaceous–siliceous shale (ASS), siliceous–calcareous shale (SCS), and mixed-composition shale (MCS). The pores in shale are dominated by intergranular and intragranular pores. The intergranular pores are mainly primary pores and secondary dissolution pores. The primary pores are mainly slit-like and polygonal, with diameters between 40 and 1000 nm. The secondary dissolution pores formed by dissolution are irregular with serrated edges, and their diameters range from 0.1 to 10 μm. The throats are mainly pore-constriction throats and knot-like throats, with few vessel-like throats, overall exhibiting characteristics of nanometer-scale width. The mineral composition has a significant influence on the development of pores and throats. Siliceous minerals promote the development of macropores, and carbonate minerals promote the development of mesopores. Clay minerals inhibit pore development. Diagenesis regulates the development of pores and throats through mechanical compaction, cementation, and dissolution. Compaction leads to a reduction in porosity, and cementation has varying effects on the preservation of pores and throats. Dissolution is the main factor for increased pores and throats. These findings provide a lithofacies-based geological framework for evaluating effective porosity, seepage capacity, and shale oil development potential in continental shale reservoirs.

1. Introduction

Shale oil and gas, as unconventional oil and gas resources, have surpassed the realm of energy, becoming a key variable in reshaping global geopolitics, economic order, and sustainable development pathways [1,2]. Their large-scale exploitation and efficient development are highly dependent on the microstructure of shale reservoirs, especially the pore size characteristics that directly affect hydrocarbon storage and seepage capacity.

Shale pore sizes range widely from nanometer scale (<1 nm) to micrometer scale [3]. Although nanometer-scale pores (2–50 nm) have a small volume, their storage capability is comparable to that of larger pores [4,5]. Organic-clay composite pores and fractures (<200 nm) account for over 70% in high-maturity shale, and their three-dimensional connectivity is significantly better than that of conventional organic pores, becoming the main storage space for shale oil [6,7]. This structure directly affects the occurrence state and flow efficiency of shale oil, serving as a key basis for evaluating recoverable resource quantities [8,9].

As a core indicator characterizing the microstructure of reservoirs, shale pore structure is an indispensable component of the reservoir evaluation system [10]. Researchers have conducted extensive studies on shale pore structure, including pore types, shapes, and sizes [11]. However, the concept of “pore” mentioned in previous studies is not precise. The so-called “pores” referred to by earlier researchers mix pores and throats together without distinction [12]. In shale oil development, the importance of throats is higher than that of pores [13,14,15]. For example, shale with only large pores and narrow throats has poor permeability and low oil recovery efficiency. Throats are narrow passages connecting pores, and their size and distribution directly affect fluid flow [16]. When the throat size is too small, the fluid is restricted due to capillary resistance and requires fracturing technology to improve seepage capacity [17]. Therefore, distinguishing between shale pores and throats, clarifying their development characteristics, and revealing their formation causes are of great significance for both the geological understanding of shale oil and its practical economic exploitation [18]. The research object is the shale reservoirs of the Fengcheng Formation in the Early Permian strata (297–306 Ma) of the Junggar Basin [19]. Through core observation, mineral analysis, optical microscopy, high-pressure mercury intrusion tests, scanning electron microscopy images, and panoramic stitched images, the study analyzes the differences between shale pores and throats and examines the factors affecting their development from the perspectives of mineral composition and diagenetic processes [20,21].

Compared with previous studies on the Fengcheng Formation shale reservoirs, which generally did not distinguish pores and throats, this study explicitly distinguishes pores from throats and systematically investigates their respective types, size distributions, and coupling relationships. By integrating lithofacies classification with high-pressure mercury intrusion, SEM observations, and geochemical analyses, this work establishes a lithofacies-controlled pore–throat evolution framework for Permian continental shales in an alkaline lacustrine setting. The study quantitatively clarifies how siliceous, carbonate, and clay minerals exert differential controls on pore and throat development and elucidates the multistage diagenetic mechanisms governing pore reduction and enhancement across different lithofacies. These findings not only advance the microscopic understanding of pore–throat systems in continental shales but also provide a lithofacies-based geological basis for evaluating effective porosity, seepage capacity, and shale oil resource potential in the Junggar Basin and analogous continental shale systems.

2. Regional Geological Setting

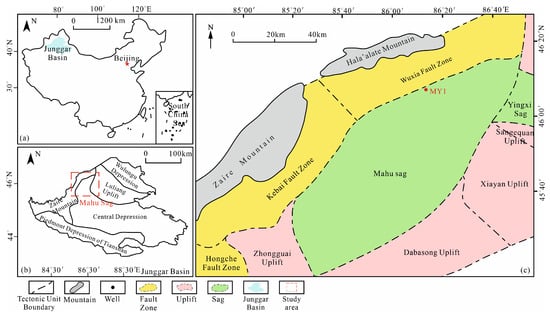

The Fengcheng Formation in the Mahu Sag of the Junggar Basin is vertically sub-divided into three members (the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd members), with a main thickness ranging from 50 to 400 m and an average value of 300 m. The shale thickness distribution exhibits a scoop-shaped depression geometry, characterized by greater thicknesses in the northwest and gradual thinning toward the southeast (Figure 1) [22]. The Fengcheng Formation was deposited in a terrestrial alkaline lacustrine basin, where sedimentation was dominated by deep-lake to semi-deep-lake systems [23]. During deposition, the basin experienced alternating arid to semi-arid climatic conditions, and the lake waters were predominantly reducing, providing favorable conditions for the accumulation and preservation of organic-rich fine-grained sediments. The sediment grain size is relatively fine, mainly composed of shale intercalated with siltstone. The alkaline lake sedimentary deposition of the Fengcheng Formation develops alkaline minerals such as magnesite and Searle site [24]. Vertically, it presents multi-level stratum architecture and sedimentary rhythm characteristics [25]. The millimeter-scale stratum rhythm interfaces in the outcrops and core samples are clear, completely recording the chemical–detrital mixed sedimentary dynamic process of the ancient lake basin [26]. Previous studies have shown that four pore types, including intergranular pores, intragranular pores, organic matter pores, and fractures, are developed in the shales of the Fengcheng Formation in the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin, with intergranular and intragranular pores being dominant; the pore space is mainly composed of micropores (0.5–1.2 nm) and mesopores (10–50 nm), and whereas macropores are poorly developed, pore morphologies are predominantly ink-bottle- and slit-shaped, and overall pore connectivity is relatively poor. However, most existing studies have treated pores and throats as an integrated pore system, and the characteristics and formation mechanisms of pores and throats have not been investigated separately [27,28].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of structural location of Mahu Sag in the Junggar Basin. (a) The Junggar Basin and its location in China; (b) Location of the study area in the Junggar Basin; (c) Division of geological structural units in the research area.

3. Sample Selection and Experimental Methods

3.1. Sample Selection

Samples were selected from Well MY1 in the Mahu Sag of the Junggar Basin (Figure 1). A total of 68 samples were chosen for mineral composition and porosity analysis, 15 samples for nuclear magnetic resonance experiments, 15 samples for N2 adsorption experiments, 15 samples for high-pressure mercury intrusion testing, 10 samples for field emission scanning electron microscopy, and 20 samples for thin section observation.

3.2. Mineral Composition Analysis

A Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer was used with a Cu-target X-ray source (40 kV/100 mA) at a scanning speed of 6°/min. The scanning range was 2.6–45° (2θ), and α-Al2O3 standard samples were used to calibrate the angles, with an error ≤ 0.01°. The samples were ground to <0.074 mm, and diffraction peaks were fitted using the ClayQuan 2016 software. The interplanar spacing was calculated using Bragg’s law (nλ = 2dsinθ) and the mineral composition content was determined [29].

3.3. Porosity Analysis

Cylindrical samples with a diameter of 2.5 cm were placed in a PorePDP-200 confining porosimeter, manufactured by Core Laboratories, Houston, TX, USA, and measurements were carried out under a constant temperature (25 °C) and stable pressure (560 kPa). After helium gas injection, porosity was calculated based on the ideal gas law, with an accuracy of up to 0.01% [30].

3.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy

The samples were polished using argon ion polishing [31]. By bombarding with an argon ion beam, a stress-free, damage-free flat surface was obtained, avoiding pore blockage or material contamination caused by mechanical grinding. After polishing, the samples were fixed with conductive adhesive and coated with gold to enhance conductivity and prevent charging effects from affecting imaging. A ZEISS Gemini scanning electron microscope, manufactured by Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Oberkochen, Germany, with a resolution of up to 0.3 nm, was used for backscattered electron imaging to distinguish different minerals and visually display the pore distribution.

3.5. Mercury Porosimeter

An AutoPore IV 9500 mercury porosimeter(Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA, USA), equipped with a precision capillary and pressure sensor was used. The pressure range was 0.034–200 MPa (corresponding to 0.007–1000 microns), covering nano-scale to micro-scale pores in shale. The samples were dried (105 °C) to a constant weight to avoid interference from moisture. The shale samples were then loaded into the expansion cell, and air was evacuated under vacuum. Pressure was applied continuously or in steps, and the change in mercury volume was recorded. Pore size was calculated from the applied pressure using the Washburn equation, and the distribution curve was plotted [32]. Mercury extrusion efficiency was used to indicate mercury release during unloading and the associated capillary trapping in the pore–throat system. Lower values reflected stronger hysteresis and more constricted effective throats, whereas higher values suggested more open connectivity and relatively wider effective throats.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Mineral Composition and Type of Lithofacies

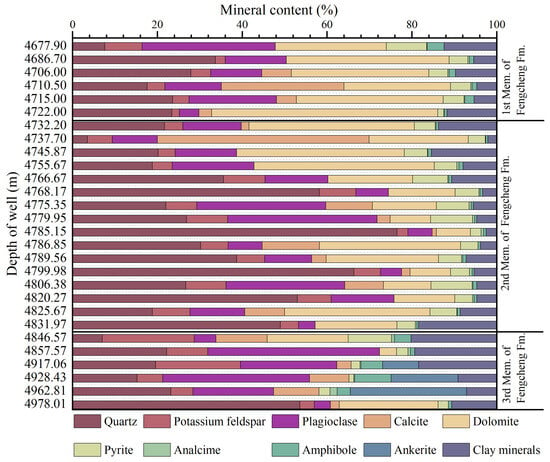

In general, the rocks whose dominant detrital particles are smaller than 0.0625 mm are classified as shale; based on this definition, the Permian shales in the Mahu Sag were deposited in a complex depositional environment with various rock types [33]. The depositional environment of the Permian shales in the Mahu Sag is complex, with various rock types. XRD experimental results show that the mineral composition is mainly quartz, feldspar, carbonate minerals, clay minerals, and pyrite (Figure 2), and sporadically occurring minerals such as siderite, anhydrite, analcite, amphibole, and ankerite. Specifically, quartz content ranges from 3.50% to 76.5% (average 29.82%). The feldspar is mainly plagioclase (0%–51.90%, with an average value of 16.74%), and the potassium feldspar content ranges from 1.3% to 35.4% (average 7.46%); carbonate minerals are dominated by dolomite (2.9%–54.5%, average 25.02%), and calcite content ranges from 0 to 49.90% (average 9.22%); clay mineral content ranges from 0 to 34.2% (average 7.58%); pyrite content ranges from 0 to 16.8% (average 5.42%). Overall, the shales are characterized by high silica minerals (20.00%–90.00%, average 53.80%), high carbonate minerals (3.40%–73.30%, average 30.94%), and low clay mineral content.

Figure 2.

Mineral composition content diagram of Well MY1.

The contents of the major minerals in different members of the Fengcheng Formation show pronounced vertical variability, without exhibiting a unidirectional trend. Quartz content is relatively low in the first member, increases markedly in the second member, and reaches a relative maximum in the middle part of the second member, followed by an overall decrease in the third member, although secondary enrichment occurs at some intervals. Feldspar contents are generally lower in the first and second members, with strong intra-member fluctuations in the second member, and they reach the highest values at the top of the third member. Carbonate minerals also display clear stratigraphic differentiation. Calcite is relatively enriched in the first member and at certain intervals of the second member, whereas its overall abundance decreases from the middle of the second member to the third member, with only localized increases. In contrast, dolomite attains its maximum content at the base of the first member, shows pronounced fluctuations in the second member, and exhibits the lowest overall abundance in the third member, indicating strong vertical heterogeneity. This feature fluctuates significantly with changes in depth.

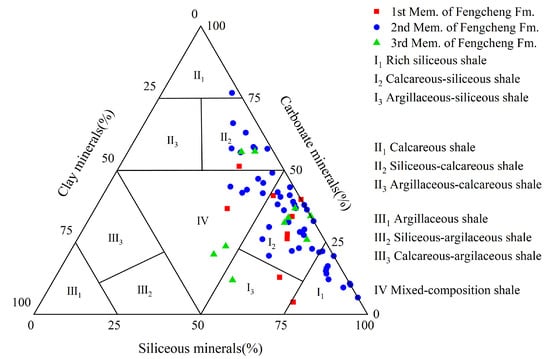

Permian continental shales can be classified into five major lithofacies, namely rich siliceous shale (RSS), calcareous–siliceous shale (CSS), siliceous–calcareous shale (SCS), argillaceous–siliceous shale (ASS), and mixed-composition shale (MCS). Rich siliceous shale (RSS) is dominated by siliceous minerals, with an average content of approximately 72%, whereas carbonate and clay minerals constitute subordinate proportions, averaging about 14% and 8%, respectively. Argillaceous–siliceous shale (ASS) exhibits a more balanced composition, with siliceous minerals averaging 53%, accompanied by a substantial clay mineral content of 34% and relatively low carbonate minerals (12%). Calcareous–siliceous shale (CSS) is characterized by high contents of both siliceous and carbonate minerals, averaging 57% and 32%, respectively, while clay minerals are scarce (4%). In contrast, siliceous–calcareous shale (SCS) is dominated by carbonate minerals, which account for approximately 57%, with siliceous minerals averaging 31% and clay minerals about 6%. Mixed-composition shale (MCS) displays relatively comparable proportions of siliceous and carbonate minerals, averaging 41% and 37%, respectively, together with a moderate clay mineral content of approximately 13%. The mineral composition is dominated by siliceous and carbonate minerals, with clay minerals accounting for no more than 25% (Figure 3). There are differences in lithofacies development across the three members of the Fengcheng Formation. The 1st member exhibits well-developed clay minerals and fewer carbonate minerals, predominantly consisting of ASS and MCS. The 2nd and 3nd members are mainly composed of RSS and CSS.

Figure 3.

Shale lithofacies classification diagram [34].

4.2. Characteristics of Core and Thin Sections

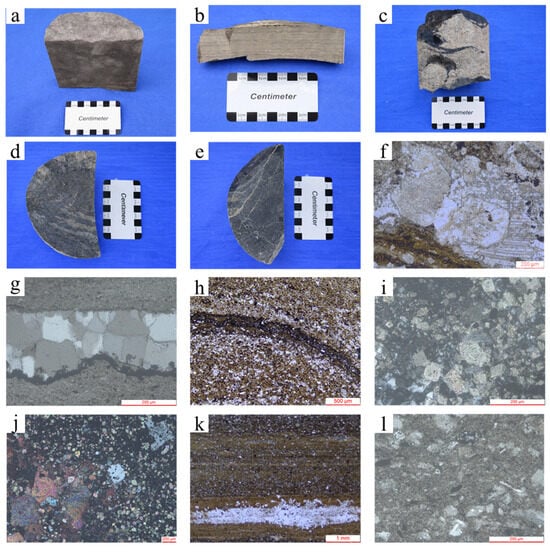

The macroscopic and microscopic characteristics of the five types of lithofacies shales are as follows: The RSS cores have a dark color and a dense, hard texture, with thin sections showing siliceous mineral content exceeding 75% (Figure 4a,f,g). The CSS cores exhibit relatively high hardness, with thin sections indicating siliceous mineral content greater than 50% and carbonate mineral content over 25% (Figure 4b,h,i). The SCS cores are relatively loose, microscopically dominated by carbonate minerals (>50%) mixed with siliceous minerals (>25%) (Figure 4c,j). The ASS cores are soft and easily split due to clay mineral content exceeding 25%, with siliceous mineral content still above 50% (Figure 4d,k). The MCS cores have uneven color and hardness, and thin sections confirm that siliceous, carbonate, and clay minerals all exceed 25%, presenting a complex mixed structure (Figure 4e,l). Specifically, the 1st member is dominated by siliceous–calcareous shale (SCS) and mixed-composition shale (MCS), the 2nd member features the widest distribution of calcareous–siliceous shale (CSS) and rich siliceous shale (RSS), and the 3rd member is characterized by the appearance of argillaceous–siliceous shale (ASS).

Figure 4.

Core and optical microscopic images of five lithofacies in the Fengcheng Formation of the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin. (a) RCS, 4810.8 m; (b) CSS, 4737.7 m; (c) SCS, 4737.7 m; (d) ASS, 4789.5 m; (e) MCS, 4826.77 m; (f) RSS, 4755.3 m; (g) RSS, 4810.9 m; (h) CSS, 4799.9 m; (i) CSS, 4715.6 m; (j) SCS,4737.7 m; (k) ASS, 4789.5 m; (l) MCS, 4826.7 m.

4.3. Types and Characteristics of Shale Pores and Throats

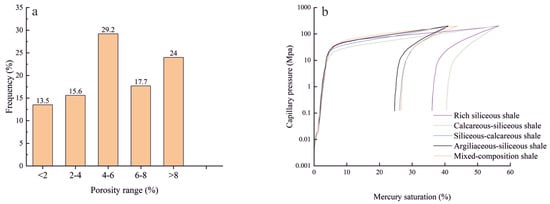

The porosity of the Permian shale in the Junggar Basin exhibits an overall relatively uniform distribution, with the porosity values mainly concentrating in the range of 4%—6% (Figure 5a). In the mercury intrusion–extrusion curves, the graphical distribution of all samples is predominantly concentrated in the left part of the plots. The displacement pressures of the samples are relatively close to one another, ranging from 10 to 45 MPa, which fall within the range of relatively high values. The maximum mercury saturation of most samples is approximately 40%, while the maximum mercury saturation of a small portion of lithofacies exceeds 50%. However, the residual mercury saturation of these samples is even higher (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Porosity frequency diagram and mercury intrusion and extrusion curves of the five lithofacies shales in the Fengcheng Formation of the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin. (a) Porosity frequency diagram; (b) mercury intrusion and extrusion curves of the five lithofacies.

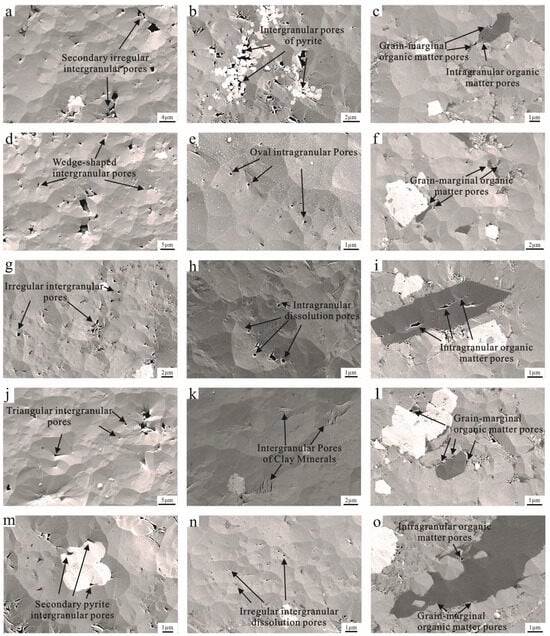

The pore space in the Fengcheng Formation shales in the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin, mainly comprises three fundamental types: intergranular pores, intragranular pores, and organic matter pores (Table 1). Among these, intergranular pores represent the most important type of inorganic pores in shale reservoirs and can be classified into primary and secondary intergranular pores. Primary intergranular pores are inherited from interparticle voids formed during deposition and are mainly controlled by depositional hydrodynamics, grain sorting, and early mechanical compaction. In contrast, secondary intergranular pores are generated during diagenesis and are associated with mineral dissolution, dehydration and shrinkage of clay minerals, and crystal growth processes. The secondary intergranular pores are mostly formed through dissolution processes, with irregular, serrated edges, good connectivity, and pore diameters ranging from 0.1 to 10 μm, larger than those of primary intergranular pores. The dehydration of clay minerals can also form secondary intergranular pores, generally showing a slit-like form due to clay mineral growth, with pore diameters of 40–500 nm. The dispersed pyrite secondary intergranular pores are even smaller, with diameters of only 1–30 nm (Figure 6).

Table 1.

Relative content and characteristics of pores of the five lithofacies in the Fengcheng Formation shales in the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin.

Figure 6.

Characteristics of pores in the Fengcheng Formation shales in the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin. (a) RSC, secondary irregular intergranular pores, 4755.67 m; (b) RSC, intergranular pores of pyrite, 4755.67 m; (c) RSC, grain-marginal organic matter pores and intragranular organic matter pores, 4755.67 m; (d) CSS, wedge-shaped intergranular pores, 4799.9 m; (e) CSS, oval intragranular pores, 4799.9 m; (f) CSS, grain-marginal organic matter pore, 4799.9 m; (g) SCS, irregular intergranular pores, 4715.6 m; (h) SCS, intragranular dissolution pores, 4715.6 m; (i) SCS, intragranular organic matter pores, 4715.6 m; (j) ASS, triangular intergranular pores, 4789.5 m; (k) ASS, intergranular pores of clay minerals, 4789.5 m; (l) ASS, grain-marginal organic matter pores, 4789.5 m; (m) MCS, secondary pyrite intergranular pores, 4826.7 m; (n) MCS, irregular intergranular dissolution pores, 4826.7 m; (o) MCS, intragranular organic matter pores and grain-marginal organic matter pores, 4826.7 m.

Intraparticle pores are widely developed. The alkaline lake environment in the study area causes siliceous and carbonate minerals to be easily dissolved by acidic fluids, resulting in the widespread presence of intraparticle dissolution pores, which are primarily elliptical in shape, commonly with pore sizes ranging from 20 to 200 nm, and are developed in a honeycomb-like concentrated arrangement with relatively good connectivity. Within clay mineral aggregates (such as illite agglomerates) and the mixed-layered illite–smectite formed from the transformation of montmorillonite to illite, a large number of intraparticle pores are also developed. The intercrystalline pores of clay minerals are mostly slit-shaped, with pore sizes ranging from 10 to 500 nm. In pyrite aggregates (often strawberry-shaped), polygonal intercrystalline pores are developed internally, occasionally filled with organic matter, forming a three-dimensional network structure with pore sizes ranging from 30 to 1000 nm (Figure 6c).

The organic matter content and thermal maturity of the shale in the study area are relatively low, and the development of organic matter pores is relatively limited [35]. Organic matter is often associated with pyrite, and a greater number of slit-like organic matter pores can be observed near pyrite. Most organic matter surfaces are smooth, internally intact, and closely connected to surrounding minerals, resulting in underdeveloped porosity. The organic matter pores are mainly small pores, with diameters ranging from 10 to 200 nm (Figure 6d).

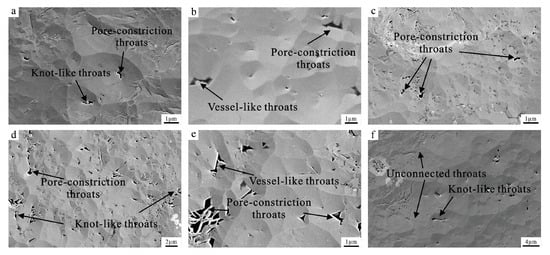

In the Fengcheng Formation shales of the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin, five main types of throats are developed: vessel-like throats, pore-constriction throats, knot-like throats, flaky throats, and curved flaky throats [36]. As shown in Figure 7 and Table 2, the shale throats are generally narrow. They are mainly pore-constriction throats and knot-like throats, which developed in all five rock lithofacies [37]. In RSS, aside from the developed knot-like throats and pore-constriction throats, there also exist disconnected throats, mostly caused by compaction or organic matter filling. In CSS, in addition to the dominant throat types, vessel-like throats develop, while flaky throats and curved flaky throats appear in small quantities. SCS is similar to CSS, with the development of vessel-like throats. Among the five lithofacies, RSS and SCS have relatively larger throat sizes, which can effectively improve pore connectivity. ASS exhibits the poorest development of throats, with many disconnected throats often filled with organic matter, reducing pore connectivity. In MCS, the development of throats is similar to that in SCS. In addition to the dominant types, few vessel-like throats can be observed, along with the development of some flaky throats and curved flaky throats, resulting in a relatively diverse range of intergranular pores.

Figure 7.

Characteristics of throats in the Fengcheng Formation shales in the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin. (a) RSS, pore-constriction throats and knot-like throats, 4755.67 m; (b) CSS, pore-constriction throats and vessel-like throats, 4799.9 m; (c) CSS, pore-constriction throats, 4799.9 m; (d) MCS, pore-constriction throats and knot-like throats, 4826.7 m; (e) SCS, vessel-like throats and pore-constriction throats, 4737.7 m; (f) ASS, unconnected throats and knot-like throats, 4789.5 m.

Table 2.

Proportion and size of throats of the five lithofacies in the Fengcheng Formation shales in the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin.

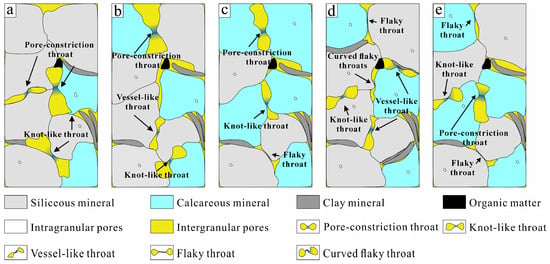

5. Discussion

5.1. Combination of Pores and Throats

Following the IUPAC recommendations, pores with diameters >50 nm were classified as large pores, whereas pores ≤50 nm were grouped as small pores in this study [38]. A throat diameter of 20 nm was used as the operational boundary between fine and wide throats as oil penetration became ineffective below 20 nm, implying limited storage/flow through such narrow throats [39]. The Fengcheng Formation shales in the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin, predominantly exhibit characteristics of small-pore and fine-throat and large-pore and fine-throat combinations (Figure 7, Table 3). Based on high-pressure mercury intrusion experiments’ data, shales are classified into distinct pore and throat types using two key parameters [37]. For pore classification, samples with a maximum mercury intrusion saturation of over 50% are defined as the large-pore type, whereas those with this saturation below 50% fall into the small-pore type. For throat classification, shales with a mercury extrusion efficiency exceeding 38% are categorized as the wide-throat type, while those with an efficiency lower than 38% are designated as the fine-throat type. An extrusion-efficiency threshold of 38% was applied to separate extrusion-restricted cases (fine-throat dominated, with stronger mercury retention) from comparatively efficient extrusion cases (wide-throat dominated). This criterion was used consistently in the lithofacies comparison. The skewness of all samples is less than zero, suggesting narrow throats. The kurtosis is all greater than one, indicating that the pore–throat distribution curve is sharply peaked, with a uniform pore radius distribution and a small fluctuation range [40]. Part of the shales exhibit a mercury removal efficiency exceeding 38%, which indicates that these shales belong to the wide-throat type. The displacement pressures range from 10 to 45 MPa, which are generally high, reflecting a relatively small pore–throat radius [41]. The maximum mercury saturation is mostly around 40%, with some lithofacies exceeding 50%, but residual mercury saturations are even higher, mainly due to small pore–throat sizes and low porosity. Even if some lithofacies have higher porosity, the throats remain fine, and the mercury is difficult to expel under reduced pressure due to capillary forces [42]. Moreover, ASS and MCS develop small-pore and wide-throat combinations, while other lithofacies display both small-pore and fine-throat combinations and large-pore and fine-throat combinations. Based on imaging characteristics, it can be concluded that the shales in the study area are predominantly small-pore and fine-throat and large-pore and fine-throat combinations (Figure 8).

Table 3.

Mercury injection data of the five lithofacies of Permian shales in the Junggar Basin.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of pore–throat combinations of the five lithofacies of the Permian shales in the Junggar Basin. (a) RSS, large-pore and fine-throat combination; (b) CSS, large-pore and fine-throat combination; (c) SCS, small-pore and fine-throat combination; (d) ASS, small-pore and wide-throat combination; (e) MCS, small-pore and wide-throat combination.

5.2. Formation Mechanisms of Pores and Throats in Permian Continental Shales

5.2.1. Role of Mineral Composition in Pore and Throat Development

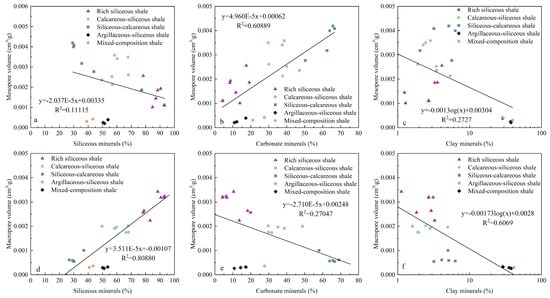

The mineral composition of different lithofacies shale varies significantly, and their physical and chemical properties directly lead to different pore–throat development characteristics [43,44]. The correlation between the three main mineral components and the mesopore and macropore volume shows that the mesopore volume has a certain correlation with carbonate minerals, with a determination coefficient R2 of 0.6099; the macropore volume has a good correlation with the siliceous mineral content, with a determination coefficient R2 of 0.8088; and the clay mineral logarithmic value has a correlation with it, with a determination coefficient R2 greater than 0.5 (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Correlation of pores and mineral compositions in the Fengcheng Formation shales in the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin. (a) Correlation between siliceous mineral content and mesopore volume; (b) Correlation between carbonate mineral content and mesopore volume; (c) Correlation between clay mineral content and mesopore volume; (d) Correlation between siliceous mineral content and macropore volume; (e) Correlation between carbonate mineral content and macropore volume; (f) Correlation between clay mineral content and macropore volume.

The influence of mineral components on pore development can be summarized as follows: During the transition from early to middle diagenesis, prior to metamorphism, the dissolution and re-precipitation of quartz and feldspar play a critical role in controlling pore evolution. Acidic fluids generated during burial and organic matter maturation preferentially dissolve feldspar minerals, producing intragranular and grain-margin dissolution pores that contribute to mesopore to macropore development. The released silica subsequently migrates and precipitates as authigenic quartz within the diagenetic system. Quartz overgrowths strengthen the rigid grain framework and enhance resistance to compaction, favoring the preservation of primary pores, while locally occluding early dissolution pores and increasing pore-scale heterogeneity. Therefore, the coupled dissolution–reprecipitation processes of quartz and feldspar exert a dual control on pore generation and modification and represent a key diagenetic factor governing the pore structure evolution of the Fengcheng Formation shales in the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin [43]. Thus, the silicate minerals promote the development of macropores and inhibit the development of mesopores [44]. The carbonate minerals are easily dissolved, and the original pores have a larger scale, but during the geological history, affected by stress and diagenesis, macro-pores are prone to rupture and being filled, resulting in more mesopores, so when the content of carbonate minerals is high, the pore volume of macropores actually decreases [45]. Thus, carbonate minerals promote the development of mesopores and inhibit the development of macropores. Clay minerals have strong plasticity, their own pores are not developed, and they are prone to filling the pores, which leads to a decrease in porosity. Thus, clay minerals inhibit the development of all pores [46].

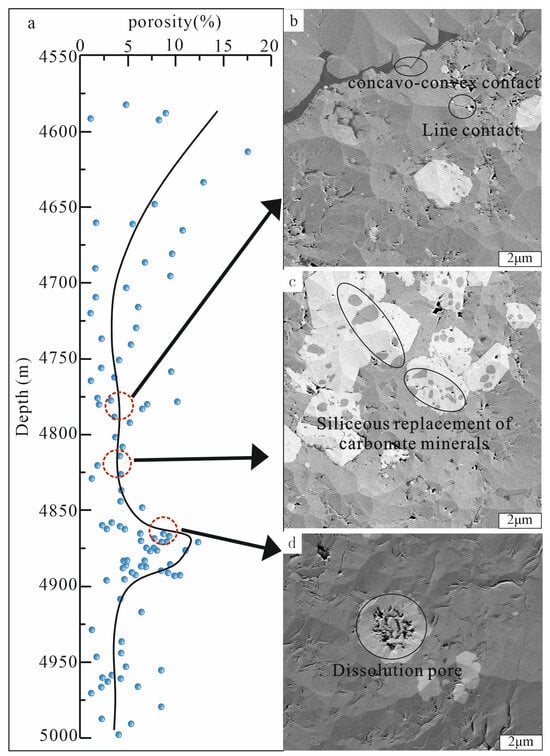

5.2.2. Impact of Diagenesis on Pore and Throat Development

The influence of diagenesis on the development of pore–throats in the Fengcheng Formation shales in the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin, is mainly manifested as pore reduction caused by mechanical compaction and cementation, as well as pore increase due to dissolution (Figure 10). The overall porosity of the shale decreases with increasing depth, as the increase in burial depth leads to an increase in overlying stratum pressure, resulting in enhanced compaction. The compaction effect is most significant in the early stage of sedimentation, and with increasing depth, the strata become denser, fluids in the pores are expelled, the original pores are destroyed and reduced, and fractures are compressed to form slit-like structures [47]. When the burial depth reaches a certain level, mineral particles undergo pressure dissolution under the combined action of organic acids and overlying pressure, and the contact relationship changes from point contact to line contact and concave–convex contact [48,49].

Figure 10.

Porosity variation with depth and diagenesis of the Permian shales in the Junggar Basin. (a) Variation in sample porosity with depth; (b) Concavo-convex contact and line contact, 4782.0 m; (c) Siliceous replacement of carbonate minerals, 4820.1 m; (d) Dissolution pore, 4863.7 m.

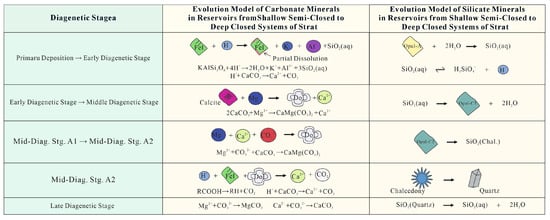

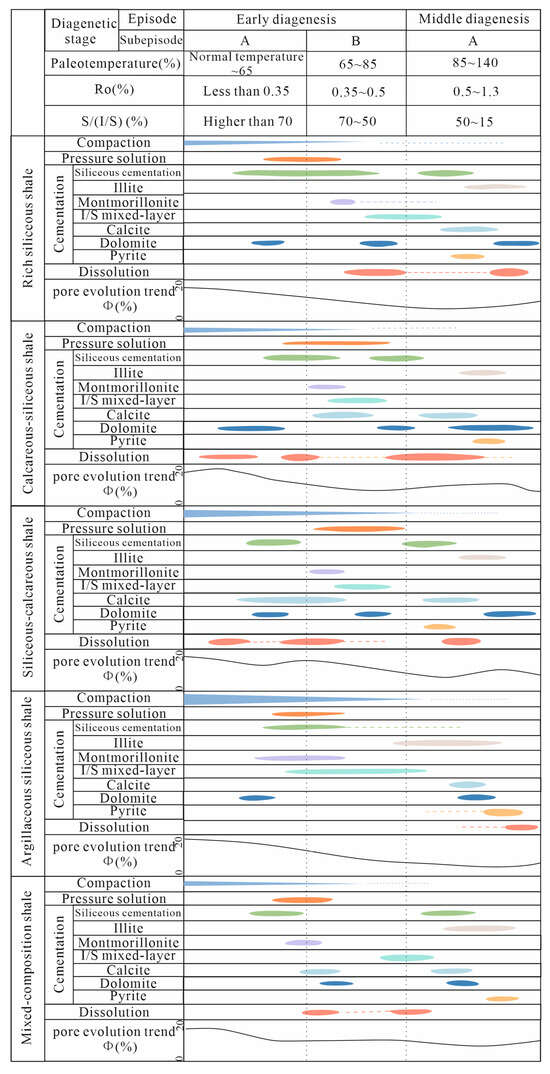

The influence of different diagenetic stages on pore evolution in Permian shales varies (Figure 11). It is mainly divided into the early diagenetic stage, the middle diagenetic stage, and the late diagenetic stage: In the early stage of sedimentation, alkaline minerals and detrital quartz were developed, and the pores were mainly primary pores, such as intergranular pores and intragranular pores [50]. The development of autogenetic quartz and calcareous cement inhibited the compaction effect, allowing intergranular pores between calcite and dolomite to be preserved. In the late stage of early diagenesis, the autogenetic quartz developed; although it avoided some compaction damage, it occupied part of the pore space. The dissolution and cementation effects began to appear, and minerals such as dolomite, calcite, and feldspar were strongly dissolved, generating a large number of dissolution pores [51]. The partial dissolution of potassium feldspar promoted the transformation of montmorillonite to illite [52]. At the same time, the clay minerals filling the pores led to a decrease in porosity [53]. From the middle diagenetic stage to the hydrocarbon generation threshold, organic matter pores began to appear, and aluminosilicate minerals and salt minerals were extensively dissolved to form dissolution pores. The fluids carrying magnesium silicate minerals promoted the growth of dolomite and made the reservoir more compact. Then, a small amount of chlorite appeared, indicating entry into the late diagenetic stage. Silicate minerals exhibit distinct stage-dependent reactions during different diagenetic phases. In the early diagenetic stage, unstable silicate minerals undergo initial dissolution and cementation, with part of the silica participating in early diagenetic reactions in dissolved or colloidal forms. During the middle diagenetic stage, increasing burial depth and temperature promote intensified dissolution–reprecipitation processes of silicate minerals; feldspars and other silicates progressively dissolve, releasing SiO2 that serves as a material source for the precipitation of authigenic silica, accompanied by the formation of secondary quartz or siliceous cements [54]. In the late diagenetic stage, silica evolution is dominated by recrystallization and stabilization, with silica transforming from amorphous or microcrystalline phases into more crystalline quartz, and the silicate mineral system becomes relatively stable, exerting a diminishing influence on pore structure modification [55].

Figure 11.

Diagenetic evolution model of carbonate and silicate minerals in the Permian shales of the Junggar Basin.

There are differences among the five lithofacies of diagenetic processes (Figure 12). In the early diagenetic stage of RSS, siliceous cementation plays a dominant role, reflecting the coupled process of aluminosilicate mineral dissolution and siliceous precipitation [56]. In CSS, the compaction process runs through all stages, accompanied by alternation of dolomite cementation and solution, demonstrating the transformation of magnesium-rich fluids into carbonate minerals. The strength of cementation in SCS is negatively correlated with pore evolution, reflecting the destruction of storage space by calcite cementation [57]. In ASS, the dissolution process in the mesogenetic stage is enhanced, corresponding to the dissolution and modification of brittle minerals by acidic fluids released from the thermal evolution of organic matter [58]. The diagenetic process of MCS shows a composite response, with the superposition of cementation, compaction, and dissolution leading to more complex pore evolution.

Figure 12.

Diagenetic evolution characteristics of the five lithofacies in the Fengcheng Formation shales in the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin.

5.3. Contribution to Industrial Hydrocarbon Production

From the perspective of reservoir evaluation and resource assessment, pore–throat architecture represents a fundamental control on the effectiveness and producibility of Permian continental shale reservoirs. The results demonstrate that significant differences exist among lithofacies in terms of pore types, pore-size distributions, and throat structures, which directly govern effective porosity, seepage capacity, and hydrocarbon mobility. Siliceous and siliceous–calcareous shales are characterized by the development of relatively large dissolution pores and comparatively well-developed knot-like and pore-constriction throats, favoring higher effective porosity and improved pore connectivity. These features constitute the material basis for shale oil enrichment and producibility. In contrast, clay-rich lithofacies are dominated by fine pores and narrow throats, resulting in poor connectivity and limited effective storage space [59]. Variations in pore–throat combination types further highlight the strong heterogeneity of reservoir quality. Reservoirs dominated by large-pore and fine-throat and small-pore and wide-throat assemblages exhibit distinct flow behaviors controlled by the coupling between pore scale and throat geometry. Consequently, reservoir effectiveness cannot be adequately characterized by total porosity alone but requires integrated consideration of throat size and connectivity efficiency [60]. Lithofacies-based classification and evaluation of shale reservoirs using pore–throat structural parameters allow differentiation between total and effective porosity and enable the determination of movable hydrocarbon thresholds. This approach improves the accuracy of shale oil resource estimation and favorable reservoir prediction, providing a robust geological basis for subsequent development optimization.

6. Conclusions

- The pores of the Fengcheng Formation shales in the Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin, are primarily intragranular, with pore sizes ranging from micrometer to nanometer scales. Rich siliceous shale (RSS) has larger pores, mainly with knot-like throats. Calcareous–siliceous shale (CSS) mainly features dissolved pores with relatively fine throat size. Siliceous–calcareous shale (SCS) primarily contains intragranular pores with diverse throat types. Argillaceous–siliceous shale (ASS) has low porosity, mainly with small pores and few throats. Mixed-composition shale (MCS) exhibits complex pore types and diverse throat types.

- Siliceous minerals contribute to the preservation of macropores and inhibit the formation of mesopores, with porosity positively correlated with the content of the siliceous minerals. Carbonate minerals promote the development of mesopores while inhibiting macropores. Clay minerals hinder pore development, leading to a negative correlation between porosity and clay content. The lithofacies with higher siliceous mineral content tend to have more macropores, the lithofacies containing carbonate minerals have more mesopores, and the lithofacies with higher clay content exhibit lower porosity.

- Diagenesis controls pore development through a “pore reduction to pore enhancement” mechanism. The initial compaction reduces porosity, while subsequent dissolution processes promote macropore formation. The cementation in different lithofacies affects porosity. In RSS, cementation inhibits pore damage. In CSS, cementation alternates with dissolution. In SCS, cementation by calcite reduces porosity. The pore evolution during diagenesis displays a difference with lithofacies.

- The pore–throat structure exerts a fundamental control on the effectiveness and producibility of Permian continental shale reservoirs. Lithofacies-dependent variations in pore scale, throat type, and connectivity systematically regulate effective porosity and hydrocarbon mobility, thereby governing reservoir quality. Consequently, lithofacies-based evaluation of pore–throat characteristics provides a basis for improving reservoir assessment and enhancing the accuracy of shale oil and gas resource estimation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and X.T.; methodology, Z.L. and Z.Y.; software, Z.L.; validation, Z.L., X.T. and Z.Y.; formal analysis, Z.J.; investigation, W.S.; resources, X.T.; data curation, Z.L. and L.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L. and Y.J.; writing—review and editing, X.T., L.C. and Z.J.; visualization, L.Y.; supervision, X.T. and Z.J.; project administration, X.T.; funding acquisition, X.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2024D01E09) and the Strategic Cooperation Technology Projects of CNPC and CUPB (ZLZX2020-01-05).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Yifan Jiao is employee of PetroChina Xinjiang Oilfield Company. The paper reflects the views of the scientists and not the company.

References

- Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Fu, H.; Wang, Z. Research on Digital Core Characterization and Pore Structure Control Factors of Tight Sandstone Reservoirs in the Fuyu Oil Layer of the Upper Cretaceous in the Bayan Chagan Area of the Northern Songliao Basin. Minerals 2025, 15, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.; Hakhoo, N.; Bhat, G.M.; Hafiz, M.; Khan, M.R.; Misra, R.; Pandita, S.K.; Raina, B.K.; Thurow, J.; Thusu, B.; et al. Petroleum Systems and Hydrocarbon Potential of the North-West Himalaya of India and Pakistan. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 187, 109–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Z.; Wen, Z.; Tian, Z.; Wang, H.; Ma, F.; Wu, Y. Distribution and Potential of Global Oil and Gas Resources. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, D.; Vishal, V.; Bahadur, J.; Agrawal, A.K.; Das, A.; Hazra, B.; Sen, D. Nano-Scale Physicochemical Attributes and Their Impact on Pore Heterogeneity in Shale. Fuel 2022, 314, 123070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, E.G.; Large, D.J.; Fletcher, R.S.; Rigby, S.P. Multi-Scale Pore Structural Change across a Paleodepositional Transition in Utica Shale Probed by Gas Sorption Overcondensation and Scanning. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 134, 105348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Ostadhassan, M. Quantification of the Microstructures of Bakken Shale Reservoirs Using Multi-Fractal and Lacunarity Analysis. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017, 39, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, K.; Han, S.-J.; Sang, S.-X.; He, J.-J.; Baral, U.; Bhandari, S.; Mondal, D.; Zhou, X.-Z.; Liu, S.-Q. Impacts of Himalayan Tectonism on Eocene Gas Shale and Its Pore Structure within the Lesser Himalayas, Nepal: Insights for Shale Gas Accumulation and Preservation. Pet. Sci. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Tang, X.; He, W.; Huang, L.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, L.; Lin, C. Characteristics and Genesis of Pore-Fracture System in Alkaline Lake Shale, Junggar Basin, China. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labani, M.M.; Rezaee, R.; Saeedi, A.; Hinai, A.A. Evaluation of Pore Size Spectrum of Gas Shale Reservoirs Using Low Pressure Nitrogen Adsorption, Gas Expansion and Mercury Porosimetry: A Case Study from the Perth and Canning Basins, Western Australia. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2013, 112, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Cai, W.; Li, Z.; Lu, H. Microscopic Characterization and Fractal Analysis of Pore Systems for Unconventional Reservoirs. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Jiang, Z.; Jiang, S.; Li, Z.; Peng, Y.; Xiao, D.; Xing, F. Effects of Organic Matter and Mineral Compositions on Pore Structures of Shales: A Comparative Study of Lacustrine Shale in Ordos Basin and Marine Shale in Sichuan Basin, China. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2018, 36, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ougier-Simonin, A.; Renard, F.; Boehm, C.; Vidal-Gilbert, S. Microfracturing and Microporosity in Shales. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2016, 162, 198–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jia, Z.; Cheng, L.; Li, B.; Jia, P.; Lan, Y.; Dong, D.; Qu, F. Characterization of Flow Parameters in Shale Nano-Porous Media Using Pore Network Model: A Field Example from Shale Oil Reservoir in Songliao Basin, China. Energies 2023, 16, 5424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Xun, Y.; Liu, H.; Qi, B.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C. An Investigation of Hydraulic Fracturing Initiation and Location of Hydraulic Fracture in Preforated Oil Shale Formations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, F.; Yan, X.; Bai, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, K. Effect of Pore Throats on the Reservoir Quality of Tight Sandstone: A Case Study of the Yanchang Formation in the Zhidan Area, Ordos Basin. Open Geosci. 2025, 17, 20220759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, C.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Q.; Gong, Q.; Zhuo, X.; Zhuo, P. The Impact of Reservoir Parameters and Fluid Properties on Seepage Characteristics and Fracture Morphology Using Water-Based Fracturing Fluid. Processes 2025, 13, 3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, I.V.; Dejam, M.; Quillinan, S.A. A Critical Review of Experimental and Theoretical Studies on Shale Geomechanical and Deformation Properties, Fluid Flow Behavior, and Coupled Flow and Geomechanics Effects during Production. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2025, 306, 104777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Jiang, Z.; Gong, X.; Li, C.; Wang, D.; Wu, Q. The Shale Gas Migration Capacity of the Qiongzhusi Formation: Implications for Its Enrichment Model. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 056603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Liu, Z.; He, W.; Zhou, C.; Qin, Z.; Wei, Y.; Yang, C. Multiple Enrichment Mechanisms of Organic Matter in the Fengcheng Formation of Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.; Tang, X.; Xu, L.; Wu, W.; Shi, X.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. Quantitative Identification Method for Pores in Shale Inorganic Components Based on Pixel Information. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2025, 12, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, P.; Song, Y.; Li, Z.; Tang, X.; Li, T.; Zhai, G.; Bao, S.; Xu, C.; et al. Porosity-Preserving Mechanisms of Marine Shale in Lower Cambrian of Sichuan Basin, South China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 55, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, D.; Tang, Y.; He, W.; Guo, X.; Zheng, M.; Huang, L. Orderly Coexistence and Accumulation Models of Conventional and Unconventional Hydrocarbons in Lower Permian Fengcheng Formation, Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2021, 48, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Wen, H.; Gibert, L.; Jin, J.; Wang, J.; Lei, H. Deposition and Diagenesis of the Early Permian Volcanic-Related Alkaline Playa-Lake Dolomitic Shales, NW Junggar Basin, NW China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 123, 104780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, L.; Jiang, Z.; He, W.; Huang, L.; Chang, Q.; Tang, X.; Ye, H. Geneses of Multi-Stage Carbonate Minerals and Their Control on Reservoir Physical Properties of Dolomitic Shales. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 153, 106216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Meng, X.; Pu, R. Impacts of Mineralogy and Pore Throat Structure on the Movable Fluid of Tight Sandstone Gas Reservoirs in Coal Measure Strata: A Case Study of the Shanxi Formation along the Southeastern Margin of the Ordos Basin. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2023, 220, 111257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.; Zhang, T.; Dodd, T.J.H.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Q.; Ji, D.; Liu, Y. Sedimentary Characteristics of Deep-Marine Gravity Flows Influenced by Island–Arc Volcanism: A Case Study of Carboniferous Sedimentary Successions in the Junggar Basin, NW China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2024, 272, 106189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, M.; Ma, M. Pore Structure of the Mixed Sedimentary Reservoir of Permian Fengcheng Formation in the Hashan Area, Junggar Basin. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hu, T.; Cao, T.; Pang, X.; Xiong, Z.; Lin, X.; Xiao, H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, F.; Jiang, L.; et al. Pore Structure and Geochemical Characteristics of Alkaline Lacustrine Shale: The Fengcheng Formation of Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin. Minerals 2023, 13, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Mou, X.; Guo, H.; Wang, X.; An, H.; Mo, Q.; Long, H.; Dang, C.; Wu, J.; et al. Pore Structure and Fractal Characteristics of the Marine Shale of the Longmaxi Formation in the Changning Area, Southern Sichuan Basin, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 1018274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; He, S.; Yi, J.; Hu, Q. Nano-Scale Pore Structure and Fractal Dimension of Organic-Rich Wufeng-Longmaxi Shale from Jiaoshiba Area, Sichuan Basin: Investigations Using FE-SEM, Gas Adsorption and Helium Pycnometry. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2016, 70, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardestani, R.; Patience, G.S.; Kaliaguine, S. Experimental Methods in Chemical Engineering: Specific Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution Measurements-BET, BJH, and DFT. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 97, 2781–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, A.M.S.; El-Sayed, N.A.A. Controls of Pore Throat Radius Distribution on Permeability. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 157, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Liu, C.; Shi, D.; Zhu, D.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Y. Characterization and Control of Pore Structural Heterogeneity for Low-Thermal-Maturity Shale: A Case Study of the Shanxi Formation in the Northeast Zhoukou Depression, Southern North China Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 943935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhou, N.; Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Li, W.; Chen, G.; Zhang, P.; Lu, S. Organic-Rich Shale Lithofacies Classification Scheme: Application and Discussion. Nat. Resour. Res. 2025; Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Cao, J.; He, W.-J.; Guo, X.-G.; Zhao, K.-B.; Li, W.-W. Discovery of Shale Oil in Alkaline Lacustrine Basins: The Late Paleozoic Fengcheng Formation, Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin, China. Pet. Sci. 2021, 18, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Kou, G.; Zhou, H.; Liu, W.; Duan, X.; Zhan, S.; Li, H.; Li, Q. Microscopic Pore-Throat Classification and Reservoir Grading Evaluation of the Fengcheng Formation in Shale Oil Reservoir. Unconv. Resour. 2024, 4, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, P.; Xue, H.; Wang, G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Li, Z. Classification of Microscopic Pore-Throats and the Grading Evaluation on Shale Oil Reservoirs. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Jin, X.; Zhu, R.; Gong, G.; Sun, L.; Dai, J.; Meng, D.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Wu, S.; et al. Do Shale Pore Throats Have a Threshold Diameter for Oil Storage? Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Mirzaei-Paiaman, A.; Liu, B.; Ostadhassan, M. A New Model to Estimate Permeability Using Mercury Injection Capillary Pressure Data: Application to Carbonate and Shale Samples. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 84, 103691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, L.; Dang, W.; Luo, T.; Sun, W.; Jiang, Z.; Tang, X.; Zhang, S.; Ji, W.; Shao, S.; et al. Discussion on the Rising Segment of the Mercury Extrusion Curve in the High Pressure Mercury Intrusion Experiment on Shales. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 102, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelly, E.N.; Yang, F.; Ngata, M.R.; Mwakipunda, G.C.; Shanghvi, E.R. A Field Study of Pore-Network Systems on the Tight Shale Gas Formation through Adsorption-Desorption Technique and Mercury Intrusion Capillary Porosimeter: Percolation Theory and Simulations. Energy 2024, 302, 131771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, B.; Huffman, K.; Thornton, D.; Elsworth, D. The Effects of Mineral Distribution, Pore Geometry, and Pore Density on Permeability Evolution in Gas Shales. Fuel 2019, 257, 116005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.A.; Rezaee, R.; Smith, G.; Ekundayo, J.M. Shale Lithofacies Controls on Porosity and Pore Structure: An Example from Ordovician Goldwyer Formation, Canning Basin, Western Australia. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 89, 103888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathia, E.J.; Bowen, L.; Thomas, K.M.; Aplin, A.C. Evolution of Porosity and Pore Types in Organic-Rich, Calcareous, Lower Toarcian Posidonia Shale. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2016, 75, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Perez, D.; Fisher, Q.; Lorinczi, P.; Velásquez Arauna, A.; Valderrama Puerto, J. A Review on Greensand Reservoirs’ Petrophysical Controls. Minerals 2025, 15, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y. Lithofacies-Controlled Pore Characteristics and Mechanisms in Continental Shales: A Case Study from the Qingshankou Formation, Songliao Basin. Minerals 2025, 15, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Luo, C.; Qiu, X.; Wen, R.; Hu, Q. Quantitative Characterization of Deep Shale Gas Reservoir Pressure-Solution and Its Influence on Pore Development in Cases of Luzhou Area in Sichuan Basin. Minerals 2025, 15, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamov, T.; White, V.; Idrisova, E.; Kozlova, E.; Burukhin, A.; Morkovkin, A.; Spasennykh, M. Alterations of Carbonate Mineral Matrix and Kerogen Micro-Structure in Domanik Organic-Rich Shale during Anhydrous Pyrolysis. Minerals 2022, 12, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmings, J.F.; Dowey, P.J.; Taylor, K.G.; Davies, S.J.; Vane, C.H.; Moss-Hayes, V.; Rushton, J.C. Origin and Implications of Early Diagenetic Quartz in the Mississippian Bowland Shale Formation, Craven Basin, UK. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 120, 104567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.-M.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Yin, Z.-Y.; Zhu, R.; Hou, Z.-Y.; Bai, Y. Further Study on the Genesis of Lamellar Calcite Veins in Lacustrine Black Shale—A Case Study of Paleogene in Dongying Depression, China. Pet. Sci. 2024, 21, 1508–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, K.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dong, L. Clay Mineral Characteristics and Smectite-to-Illite Transformation in the Chang-7 Shale, Ordos Basin: Processes and Controlling Factors. Minerals 2025, 15, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B.S.; Schieber, J.; Kalinec, J. Clay Diagenesis and Overpressure Development in Upper Cretaceous and Tertiary Shales of South Texas. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 147, 105978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørlykke, K.; Jahren, J. Open or Closed Geochemical Systems during Diagenesis in Sedimentary Basins: Constraints on Mass Transfer during Diagenesis and the Prediction of Porosity in Sandstone and Carbonate Reservoirs. AAPG Bull. 2012, 96, 2193–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, M.; Keene, J.B.; Gieskes, J.M. Diagenesis of Siliceous Oozes—I. Chemical Controls on the Rate of Opal-A to Opal-CT Transformation—An Experimental Study. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1977, 41, 1041–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Memory, S.L.; Joseph, J.; Meshram, R.R. Mineralogical and Geochemical Studies of Shales from Kopili Formation, Dima Hasao District Assam, North East India: Insights into Diagenesis, Deposition and Provenance. Evol. Earth 2024, 2, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.-F.; Zhang, T.-L.; Pan, J.-F.; Li, Y.-W.; Sheng, J.J.; Ge, D.; Jia, R.; Guo, W. Evolution of the 3D Pore Structure of Organic-Rich Shale with Temperature Based on Micro-Nano CT. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 2339–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Tang, L.; Ma, K.; Yang, Y.; Jin, C.; Wu, L.; Li, X. The Control Effect of Burial Evolution Time Limit on the Organic Matter Pore Structure of Shale: A Case Study of the Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation Shale from the Periphery of the Sichuan Basin in Southern China. Unconv. Resour. 2025, 9, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Lai, F.; Gao, X.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, N.; Luo, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Peng, S.; Luo, X.; et al. Characteristics and Genetic Mechanism of Pore Throat Structure of Shale Oil Reservoir in Saline Lake—A Case Study of Shale Oil of the Lucaogou Formation in Jimsar Sag, Junggar Basin. Energies 2021, 14, 8450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; An, C.; Dong, Z.; Xiao, D.; Yan, J.; Ding, G.; Yan, P.; Zhang, J. Reservoir Characteristics and Controlling Factors of Oil Content in Hybrid Sedimentary Rocks of the Lucaogou Formation, Western Jimusar Sag, Junggar Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 736598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.