Abstract

Xicheng is an important Chinese area enriched in lead–zinc polymetallic ore concentration area. Since the 1970s, substantial research achievements have been made in various domains, including the geological and geochemical characteristics of the deposits, metallogenic chronology, features of the marine basin during the initial mineralization stage, enrichment and precipitation of lead–zinc and other metallic ions, ore genesis, and metallogenic simulation experiments. Among these, the most representative findings focus on exhalative sedimentary reformation and the complexation of organic matter with lead–zinc metal elements during sedimentary processes. This review discusses the formation and evolution of sulfur-containing organic matter, especially H2S, under Thermal Decomposition of Sulfate (TDS), Bacterial Sulfate Reduction (BSR), and Thermochemical Sulfate Reduction (TSR) conditions, and further summarizes the general characteristics of organic matter and lead–zinc (and other metal elements) adsorption–complexation–reduction. Subsequent research on organic lead–zinc mineralization in the Xicheng area has been grounded in ore deposit geology and geochemistry, adopting the perspective of organic fluids. These studies focus particularly on the formation process of Pb–Zn organic complexes and analyze the various stages and mechanisms of mineralization based on the characteristics and evolution of organic matter. This approach provides new insights for understanding both the general features and the unique attributes of lead–zinc mineralization in the Xicheng area.

1. Introduction

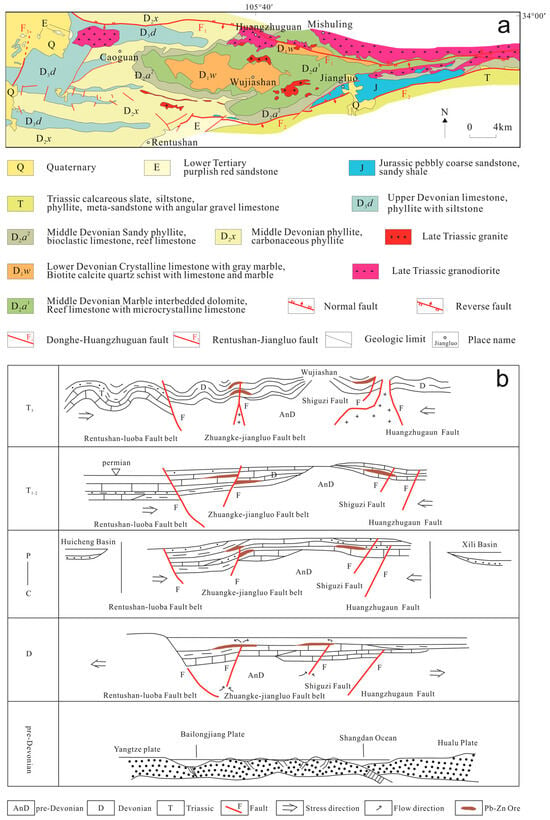

The Xicheng lead–zinc ore field is located at the junction between the Hercynian–Indosinian fold belt on the southern margin of Central Qinling and the Indosinian fold belt on the northern margin of South Qinling, within the hinterland of the western segment of the Qinling Orogenic Belt. The ore-bearing strata are primarily from the Upper Paleozoic Devonian system, which constitutes a set of shallow-metamorphosed flysch-like (clastic–siliceous–carbonate) sedimentary structure. The southern boundary of the Xicheng ore field is demarked by the Rentushan–Jiangluo Fault, with Triassic and Devonian strata in the south and north, respectively. It is the boundary fault between the Qinling Indosinian terrane and the Hercynian fold belts and extends for more than 300 km. On the northern side of the mining district is the Donghe–Huangzhuguan Fault, which extends nearly 200 km in an E–W direction and is characterized by Devonian strata. These two major faults converge into a broom-shaped syntaxis east of Huixian and Luobao, diverging to the west and converging to the east. Devonian strata are widely developed within the rhombic fault and block defining north–south boundary faults (Figure 1a). The region hosts numerous large to extremely large lead–zinc deposits, with proven resources reaching approximately 18 million tonnes, and inferred resources could reach 25 million tonnes. Major deposits include Dengjiashan (0.54 million tonnes, 6.27% Zn, 1.31% Pb), Changba (3.80 million tonnes, 5.16% Zn, 1.38% Pb), Lijiagou (3.13 million tonnes, 8% Zn, 1.29% Pb), Luobao (1.05 million tonnes, 4.55% Zn, 1.61% Pb), and Bijiashan (0.63 million tonnes, 4.88% Zn, 1.2% Pb). Furthermore, nearly 40 small and medium-sized lead–zinc deposits have been identified in the area, including Dujiaying, Yeshuihe, Guanzigou, and Miaogou.

Figure 1.

Geological structure (a) and mineralization schematic diagram (b) of the Xicheng ore field.

Relevant research on the mineralization stages has divided the mineralization of the Xicheng Pb–Zn ore field into four main stages (Figure 1b). During the Caledonian orogeny period, characterized by extension and compression, the Wujiashan basement complex was formed. It was during this phase that the Rentushan–Jiangluo Fault (a component of the Liangdang–Zhen’an Fault) was already active, providing conditions for the formation of the Xicheng Basin and the migration of deep fluids, and laying the foundation for subsequent structural development and orebody formation [1]. The early Hercynian fault-depression sedimentation stage involved the northern part of the ore concentration area. It characterized the formation of a robust barrier system dominated by the Bijiashan biohermal and a fault-depression stagnant basin in the Changba-Xiangyangshan area; this combined paleotopography provided the critical conduit systems and confined environment conducive to the exhalative sedimentation of ore-forming fluids [2]. In the southern part of the ore concentration area, Middle Devonian ore-forming fluids migrated upwards along the Zhuangke–Shapoli Fault and underwent exhalative sedimentation. Areas with well-developed organic reefs were particularly conducive to the accumulation of metallogenic materials, forming initial ore layers. This resulted in the concordant occurrence of the ore layers with the strata, making them an integral component of the stratigraphic sequence [3]. During the mid–late Hercynian uplift stage, due to sedimentary burial depth and uplift, significant regional metamorphism occurred. Tectonic activity and thermal events activated and migrated some active elements, such as Hg–Sb, while Pb–Zn hosted in siliceous–carbonate rocks accumulated further [4]. The fold-orogeny stage during the Indosinian movement, a huge geological change, involved the strong orogenic movement of the Indosinian period (220–205 Ma), which caused a series of magmatic activities, providing sufficient heat and power for transforming Pb–Zn deposits. In the Xicheng mineralization concentration area, the reformation effects are manifested in the following two aspects: (1) Provision of thermal energy: The majority of the lead–zinc deposits are hydrothermal sedimentation-reformed deposits, characterized by extensive distribution and large-scale mineralization. Their broad spatial distribution and large size imply formation from vast hydrothermal systems, for which the Indosinian magmatism provided the essential heat engine. (2) Providing dynamic forces for reformation mineralization: The ore-forming hydrothermal fluids originate from deeper strata. The reason they can circulate toward structurally weak zones in shallower strata while carrying a large number of metal ions is due to compression, which turns the deep hydrothermal fluids into confined aquifer systems [4,5,6].

Research on the genesis of ore deposits commenced in the 1970s. Dong [7], based on S isotope data and the relationship between ore bodies and strata, structures, and metamorphism, proposed that the Pb–Zn deposits in this area were jointly controlled by sedimentary processes and later metamorphism. On the other hand, Huang [8] proposed distinct metallogenic models based on the different types of deposits. Submarine volcanic activity formed blocky sulfide ore bodies in limestone, which were later overprinted by tectonic–metamorphic events on an extensive carbonate platform, further generating lead–zinc deposits within siliceous rocks. In the mid-to-late 1980s, strata-bound deposits became the main academic view, leading to several key understandings: (a) the primary ore-forming materials were mainly derived from seawater, as well as terrigenous and deep-seated materials transported by seawater [9,10,11]; (b) deposit formation was dominated by sedimentation, with later reformation playing a subsidiary role [12,13]; (c) the ore-forming fluids were primarily metalliferous hot brines exhaled along synsedimentary faults [14,15]. Since the 1990s, the theory of submarine exhalative sedimentary mineralization has gradually emerged and has become the dominant perspective of lead–zinc mineralization in the Xicheng area [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Recent studies have shown that tectonic activity and its products are the dominant ore-controlling factors in the Xicheng ore concentration area. The Pb–Zn deposits represented by Changba–Lijiagou have obvious post-genetic mineralization characteristics. Moreover, the widespread and intense coupling of the metamorphic deformation-magma and activity-fluid in the Late Triassic mediated the large-scale polymetallic mineralization in this region [5,23].

The role of organic matter in Pb–Zn mineralization is worthy of further exploration. The essence and regularity of Pb–Zn mineralization can be revealed by systematically analyzing the characteristics, composition, distribution, evolution, and participation of organic matter in the mineralization of different types of Pb–Zn deposits, providing an important basis for finding new Pb–Zn resources [24].

This review summarizes the organic mineralization in the Xicheng Pb–Zn ore field and the adsorption–complexation–reduction process of organic matter and Pb–Zn metal elements and aims to add to the existing understanding and research prospects in this ore field.

2. Pb–Zn Deposits in the Xicheng Belt

2.1. Geologic Settings

Organic mineralization refers to the role played by organic matter derived from organisms in acting upon ore-forming elements during sedimentation, diagenesis, and mineralization processes. It encompasses various ore-forming processes involving organic matter and diverse organic fluids, such as the adsorption, complexation, migration, precipitation, and concentration of ore-forming elements [25]. Although scholars became aware of the issue of organic mineralization as early as the 1930s, significant progress has only been made in the past decade [26]. Research has shown that organic matter acts as a reducing agent in ore formation, and the oxidation of organic carbon accelerates the mineralization of metal salts [27,28]. Biological organic matter not only plays a role in deposit formation under supergene environments but is also crucial throughout the activation and migration of ore-forming elements and the localization and enrichment of ore-forming fluids. Research has also expanded to typical stratiform, volcanic sedimentary, sedimentary reformed, and certain typical hydrothermal deposits. Ample evidence supports the significant role of organic matter during the mineralization of Pb–Zn deposits [29,30,31,32,33,34].

In the 1990s, Duan [35] conducted a preliminary study on the organic matter characteristics of the Bijiashan lead–zinc deposit (Table 1), essentially clarifying the adsorption of metal elements from seawater by organic matter. Based on the spatial distribution characteristics of organic carbon and biomarker compound parameters, Sun [36] inferred that organic matter is involved in the formation of source beds, influencing the redox properties of the depositional environment, adsorbing lead–zinc metal elements, and facilitating the reductive precipitation of lead–zinc sulfides. Through the analysis of different component compositions of soluble organic matter in the Xicheng ore field, Zhang [37] clarified that the sedimentary environment was a strongly reducing to reducing, weakly alkaline environment. From the perspective of biological organic mineralization, Lin [38] conducted experimental simulation and mechanism analysis of biomineralization. The results indicated that besides the organic matter in the host strata, marine invertebrates and lower aquatic organisms also participated in biomineralization. Zhu [39] proposed that in the late stage of reformation mineralization in the Luoba lead–zinc ore field, carbon asphalt was closely associated with the ores, and the organic matter and ore-forming elements arrived at the ore-forming site and participated in the mineralization during the transformation mineralization period. Findings of a thermal water simulation experiment of organic fluids in the Luoba area by Lin [40] revealed that organic fluids are more likely to activate and migrate lead and zinc ore-forming elements. In the formation of ore deposits, siliceous rocks, silicified and bioclastic limestone, and phyllite may have played the roles of the ore source, reservoir layer, and cap rock, respectively.

Table 1.

Organic carbon content of Xicheng lead–zinc ore deposit.

2.2. Pb–Zn Deposits

In the Xicheng Pb–Zn ore area, there seems to be an inseparable relationship between organic mineralization and the content of total organic carbon, with the organic carbon content being higher closer to the ore body. Table 1 lists an overall close relationship between Pb and Zn metal elements and organic mineralization.

Previous research on soluble organic matter has mainly focused on the characterization of alkane (saturated hydrocarbon) biomarker compounds. Overall, in terms of the saturated hydrocarbon gas chromatogram profiles, the low-carbon-number region exhibits distinct peaks, with some samples also possessing a high carbon number but do not constitute the dominant fraction [36]. The main carbon peak mainly pertained to nC18 or nC17, with an unobvious odd–even advantage and a relatively obvious phytane predominance, indicating the overall reductive sedimentary environment of the organic matter in the Xicheng Pb–Zn ore field [36]. Regarding the distribution of terpanes or hopanes, the carbon number distribution of long-chain triterpanes is concentrated between C19 and C27, while the pentacyclic triterpanes with hopane skeletons are mostly distributed between C27 and C32. The ore-associated limestone samples are dominated by pentacyclic triterpanes, whereas carbonaceous phyllite samples are characterized by long-chain triterpanes. Rearranged steranes and the related parameters of C27 (C27dia) and C29 (C29ββR/ααR) indicate that the organic matter has experienced a long migration time. Furthermore, triaromatic steranes are more readily detected in the eastern part than in the western part of the ore field, indicating that the eastern Xicheng lead–zinc ore field has experienced stronger thermal effects [37].

The main series of aromatic compounds includes benzene, biphenyl, naphthalene, phenanthrene, pyrene, fluorene, and thiophene, as well as individual polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon compounds such as benzopyrene, benzofluoranthene, benzanthracene, and cadalene. Among these, dibenzothiophene and benzonaphthothiophene were predominant, indicating the special position of organic sulfur. This also provides data support for the precipitation of ore-forming metals such as lead and zinc by the combination of organic sulfur and metal ions.

2.3. Forming Mechanism

Correlation analysis showed a strong positive correlation between lead and zinc and carotenes, terpenes, and steranes, with correlation coefficients of 0.42 and 0.73, 0.99 and 0.89, and 0.98 and 0.91, respectively [39]. In contrast, some organic matter molecular parameters, ω(∑C22−)/ω(∑C22+), ω(tricyclic terpanes)/ω(tetracyclic terpanes), ω(C20 + C21)/ω(C23 + C24), and ω(terpanes)/ω(steranes), have a significant negative correlation with lead and zinc metal elements, with correlation coefficients of −0.07 and −0.77, −0.16 and −0.78, −0.06 and −0.75, and −0.81 and −0.96, respectively (Table 2) [39].

Table 2.

Organic molecular abundances and Pb–Zn element content in the Xicheng ore field [39].

Existing thermal simulation experiments have shown that neutral terpene biological precursors, such as dehydroabietane, and polar precursors (abietic acid, abietol, and pimaric acid) undergo various complex reactions during prolonged simulation experiments, including isomerization, dehydrogenation, aromatization, decarboxylation, and defunctionalization. Meanwhile, the formation of hopanoids is inextricably associated with bacterial action [41,42,43]. Therefore, the relative increase in the content of terpanes and steranes during evolution suggests enhanced thermal maturation and microbial activity, and the strong positive correlation between metal elements and these biomarkers provides important evidence for the involvement of organic matter in lead–zinc mineralization. Carotene is an organic molecule indicator of reducing environments, and its high abundance indicates a strongly reducing sedimentary paleoenvironment and high organic matter. Such organic-rich settings naturally carry elevated contents of metallogenic elements, which consequently leads to a pronounced positive correlation during mineralization processes.

The overall negative correlation between the organic matter molecular parameters and lead–zinc metal elements may be attributed to the cracking of high-carbon, long-chain normal alkanes into low-carbon, light components under high temperature, pressure, and microbial degradation during mineralization (lead–zinc metal element precipitation). This process leads to a pronounced negative correlation between lead and zinc metal elements and various organic molecule ratios. It is worth noting that some research shows that negative correlations of Pb (−0.07, −0.16, −0.06, and −0.81) are significantly weaker than those of Zn (−0.77, −0.78, −0.75, and −0.96). The reason may be that Zn is more active than Pb and more prone to migration, and the related thermodynamic experiments also show that Zn starts to precipitate at 80 °C, which could explain why Zn exhibits stronger negative correlations than Pb, and suggests that the precipitation process of Pb–Zn occurred in a low-temperature environment.

3. Organic Materials (Types and Features)

Existing statistical data indicate that MVT Pb–Zn deposits, which account for 24% of the global number and 23% of the reserves of all lead–zinc deposits, spatially coexist with or overlie paleo-oil and gas reservoirs [44]. Meanwhile, studies on the metallogenic mechanisms of MVT Pb–Zn deposits have revealed that geo-fluids rich in organic matter components play an exceptionally critical role in Pb–Zn mineralization [26,45], and there is a certain similarity in the overall characteristics of organic matter.

3.1. Overall Characteristics of Organic Matter

The general properties of organic matter in the Sedex and MVT lead–zinc deposits display elevated saturated alkane/aromatic hydrocarbon ratio parameters, exceeding 1 in overall value, indicating a sapropelic organic matter type (Type I) [46,47,48,49,50]. For the (non-hydrocarbon + bituminite)/(alkanes + aromatics) ratio, most values were less than 1, indicating that the organic hydrocarbons were light, of lower maturity, and less altered in the later stage. In lead–zinc ore fields such as Wulagen and Niujiaotang, this parameter ratio shows larger values, which may be due to the hydrothermal effect in the later stage of the mining area [51]. Judging solely from the generational sequence of organic matter formation (humic acid, low-maturity kerogen, organic acid, petroleum, high-maturity kerogen, asphalt, and methane), the increase in the non-hydrocarbon + bituminite content implies that the evolution of organic matter reached its middle and late stages [52]. From the perspective of organic mineralization in lead–zinc ore bodies, this essentially implies an intensification of Thermochemical Sulfate Reduction (TSR) reactions and an increase in the precipitation and exsolution of metal minerals [53].

3.2. Characteristics and Evolution of Sulfur Compounds

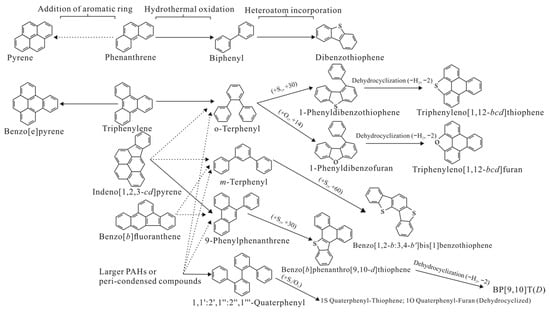

Among the sulfur-containing aromatic hydrocarbons, the characteristics displayed by Sedex and MVT-type lead–zinc deposits are consistent, and the main sulfur-containing compounds include dibenzothiophene, benzothiophene, dibenzothiophene-5,5-dioxide, and benzothiophene-2,3-dicarboxylic acid; the latter two are oxidation products of the former two [53,54]. There are many different understandings of different types of deposits in terms of the formation of sulfur-containing PAHs. In the organic mineralization research of the Australia McArthur River (HYC) lead–zinc–silver deposit, sulfur-containing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are mainly dibenzothiophene and 4, 2+3, and 1 methyl dibenzothiophene, and they show high abundance in ore and mudstone layers, with thermal gradients at the sedimentary margins likely being the main cause for this phenomenon and the distribution of sulfur compound isomers [55]. However, some researchers also believe that in the presence of ZnS and PbS, some unsubstituted PAHs, aryl–aryl linked phenyl-derivatives, and S/O atom-containing compounds are predominantly controlled by hydrothermal processes rather than thermodynamics [33]. In the study of the Erdaokan lead–zinc–silver deposit in Northeast Daxing’anling, only a high content of dibenzothiophene was found, and no other alkylated thiophenes and thiolates were found [34]. Some researchers believe that the transformation or generation of associated organic molecules may be significantly affected by mineral catalysis in metal deposits, which may be the main factor controlling organic transformation [33]. In a study of the Jinding Pb–Zn ore field, the hydrothermal catalytic conversion process and metastable equilibrium of PAHs were systematically described. In addition to dibenzothiophene, sulfur-containing aromatic compounds were also found in benzonaphthothiophene, and in the mass spectrum 258+260, 1-phenyldibenzothiophene, and triph-enyleno [1,12-bcd]thiophene [33]; the specific evolution process is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Possible key reaction pathways (solid lines) during the hydrothermal oxidation of selected PAHs, addition of aromatic rings, and heteroatom incorporation into phenyl-derivatives for the Jinding deposit samples. Note that there may be multiple combinations of reaction pathways, but these are not prominent in the present study and are shown with dashed lines.

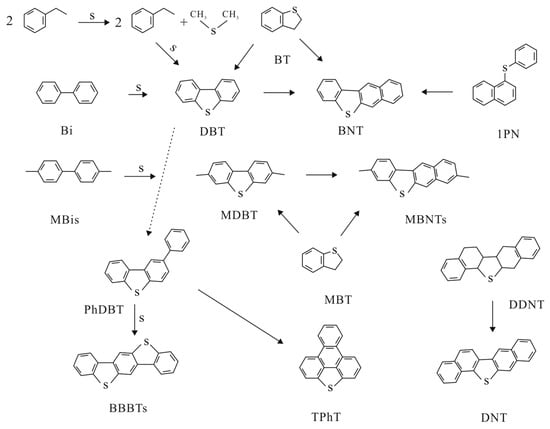

Notably, during the evolution of organic matter in geological history, the behavior and exact reaction pathways of certain thermally labile phenyl derivatives and their source compounds and thiophene or furan alkylations are unpredictable. Furthermore, hydrothermal ring opening, internal conversion (intramolecular cyclization), and the intermolecular introduction of additional heteroatoms result in more complex combinations [56,57]. In a focused study of sulfur-containing organic compounds, Zhao [58] suggested that the abundance and speciation of sulfur-containing polycyclic aromatic compounds (SPACs) are initially affected by the sulfur content and will gradually be affected by maturity in the later stages of evolution. However, it is also closely related to the iron ion content during sedimentary evolution; a lower iron content in the sedimentary environment is conducive to PAH–sulfur reactions and the formation of more sulfur-containing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (organic sulfur) [59]. Moreover, some experiments have shown that DBT can be produced from biphenyl and elemental sulfur [60,61], is more abundant in marine sedimentary environments, and its content tends to increase with advancing thermal maturity [59]. The evolutionary trends of the compounds are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Possible formation pathways of major SPACs. Abbreviations: BT: benzothiophenes; Bi: biphenyls; MBi: methylbiphenyls; DBT: dibenzothiophene; MDBT: methyldibenzothiophenes; BNT: benzonaphthothiophene; BNT: benzonaphthothiophenes; MBNT: methylbenzonaphthothiophenes; 1PN: 1-phenylthionaphthalene; TPhT: triphenyleno[1,12-bcd]thiophene; PhDBT: phenyldibenzothiophene; BBBTs: benzobisbenzothiophenes; DNT: dinaphthothiophenes; DDNT: dihydrodinaphthothiophene.

4. Effects on the Mineralization of Pb–Zn Ore Formation

4.1. Formation of H2S

Organic matter acts as an activator, carrier, and reducing agent in lead–zinc mineralization; however, its role varies slightly in different types of lead–zinc deposits. For example, in MVT-type Pb–Zn deposits, organic matter is primarily derived from oil and gas reservoirs in the foreland basin and forms a mineral-containing fluid system together with basin brine. When hydrocarbon reservoirs are disrupted by tectonic or magmatic activities, the mixing of hydrocarbon fluids with brines promotes sulfate reduction and metal precipitation, leading to large-scale lead–zinc mineralization. In Sedex-type Pb–Zn deposits, organic matter mainly originates from lower organisms in marine sedimentary environments, such as bacteria and algae, which perform photosynthesis or anaerobic respiration under anoxic conditions, generating substantial amounts of organic matter and H2S. These substances then react with metal ions in seawater to form a stratiform lead–zinc mineral. Therefore, in organic-associated lead–zinc mineralization, the source and evolution of H2S are critical for Pb–Zn organic mineralization. Current research shows that there are three primary sources of H2S: 1. Thermal Decomposition of Sulfate (TDS) of sulfur-containing organic matter in kerogen; 2. Bacterial Sulfate Reduction (BSR) of sedimentary sulfate in strata, and 3. Thermochemical Sulfate Reduction (TSR).

Thermal Decomposition of Sulfate (TDS) refers to the formation of hydrogen sulfide, also known as cracking-type hydrogen sulfide, by breaking sulfur-containing heterocycles in sulfur-containing organic matter under heating.

The channels for generating H2S by thermal action:

RCH2CH2SH (Kerogen I) → RCHCH2 (Kerogen II) + H2S↑

Alternatively, sulfate and elemental sulfur can oxidize substances such as kerogen or methane to produce H2S.

CH4 + SO42− + 2H+ → CO2 + 2H2O + H2S↑

And CH4 + 4S° + 2H2O → CO2 + 4H2S↑

And 10H30H45SO (Kerogen I) + 98S° → (C30H30S4)10O3 (Kerogen II) + 7H2O + 68H2S↑

In addition, Liu [62] believed that during the process of mineral-containing acidic hydrothermal fluid venting on the seafloor, H-bearing organic molecules may combine with elemental sulfur and generate H2S under thermal influence.

TaHCH2-S-H + H2O → (TaCH2O)2 + H2S (Ta represents an organic molecule)

In sulfate-bearing strata, the generation of H2S may be due to the participation of hydrocarbon fluids.

Hydrocarbons + CaSO4 (Sulfate) → CaSO4 + H2S + H2O + CO2 + S

Bacterial Sulfate Reduction (BSR) refers to the dissimilatory reductive metabolism of sulfate by sulfate-reducing bacteria that use various organic substances or hydrocarbons as sources of hydrogen to reduce sulfate and directly form hydrogen sulfide under dissimilatory conditions. This process is represented by the following chemical reactions:

∑CH (or C) + SO42− → H2S + H2O + CO2

Thermochemical Sulfate Reduction (TSR) refers to the chemical reaction in which sulfate minerals are reduced to sulfides by hydrocarbons and other organic substances under heated conditions. This process is considered the predominant origin of hydrogen sulfide gas in reservoirs and is an important mechanism for sulfide and hydrocarbon precipitation in hydrocarbon-bearing deposits [63,64]. The chemical expression of this process can also be represented as follows:

3SO42− + 3H+ + 4C6H5CH3 → 4C6H5COOH + 3HS− + 4H2O

2HS− + Me2+ → 2MeS + 2H+ (Me = Pb, Hg, Zn, Fe……)

Some studies have also suggested that sulfate (gypsum) serves as the primary source of hydrogen sulfide required for sulfide formation, and that SO42− is reduced to H2S [25]. During the biological reduction pathway, organic matter serves as a nutrient substrate for sulfate-reducing bacteria and other microorganisms, ensuring the production of hydrogen sulfide through biological reduction. The organic matter required for BSR typically consists of organic acids and oxygenated or fermentatively biodegraded organic materials. In thermochemical reactions, sulfur is supplied via the abiotic reduction of SO42− by organic matter. The organic matter required for the TSR reaction is generally branched and straight-chain alkanes, followed by cyclic and monoaromatic organic compounds [65,66]. Additionally, primary or metabolically produced organic sulfides may provide a sulfur source [67].

The primary inorganic products of the BSR and TSR reactions (Table 3) were H2S (HS−) and HCO32− (CO2). When alkaline earth metals or transition metals are present in the system, H2S can act as a “capture agent” for metal ions, resulting in the formation of carbonates or sulfides such as pyrite, galena, and sphalerite. Concurrently, elemental sulfur may accumulate in significant quantities, particularly after the consumption of reactive hydrocarbon organic matter [66,68]. A high burial rate of organic carbon promoted the reduction of sulfate, thereby promoting the formation of pyrite. Therefore, the deposition of organic carbon is considered the primary factor controlling pyrite formation [69]. Billon [70] used fatty acids as biomarkers to study the early formation of sulfides in mudflat samples. They found that the activity of sulfate-reducing bacteria promotes the formation of sulfides (FeS); however, if readily biodegradable organic matter is lacking, the sulfidation process is constrained. Pyritization can occur at the interface between water and sediment to form pyrite (FeS2) via three possible mechanisms:

Table 3.

Simplified geochemical reactions in BSR and TSR.

(1) In a strictly anaerobic environment, FeS + H2S → FeS2 + H2.

(2) Reduction reaction of elemental sulfur or polysulfide compounds, FeS + S0 → FeS2; in this process, partial reoxidation reactions may occur due to bioturbation or water flow, thereby promoting the formation of FeS2.

(3) Reaction of soluble sulfides and iron hydroxides, 2FeOOH + S0 + 3H+ → 2FeS2 + 2H2O [70].

4.2. Adsorption of Lead and Zinc by Organic Matter

The adsorption of organic matter means that it can form chemical or physical bonds with metal ions or complexes such as lead and zinc, thereby influencing the migration and enrichment of metals. During sedimentation, it can provide a significant amount of negative charge, forming electrostatic adsorption with positively charged metal ions and increasing the concentration and stability of metal ions. In the research related to the remediation of heavy metal pollution, the adsorption mechanisms of lead and zinc metal ions on organic matter are more advanced. Lima [71] found that in the adsorption of heavy metal pollutants such as lead, zinc, and cadmium (Cd) by organic matter, different metal ions have different adsorption preferences, and overall adsorption efficiency followed the order lead > cadmium > zinc; compared to the initial concentration tested, some organic matter adsorbed almost 100% of the lead. McKay and Porter [72] proposed that the adsorption of metal ions is related to their electronegativity; metal ions with higher electronegativity are more attractive on the surface of the adsorbent. Table 4 presents that, except for the two cases where some Zn and Cd [73], and Cd and Pb [74] exchange positions, the remaining data indicate a trend correlating electronegativity (Pb2+ = 1.8 > Cd2+ = 1.7 > Zn2+ = 1.6) with organic adsorption capacity.

Table 4.

PTE (including Pb, Zn, and Cd) adsorption affinity order by organic reactive materials.

In terms of adsorption formulation, due to the complexity of organic matter composition, there is no single universal chemical equation to describe the adsorption of metal ions by organic matter. However, regardless of whether it is an element or a compound, any substance that can provide an electron pair, such as amino, carboxyl, or thiol groups, can combine with metal ions, such as Pb2+, Zn2+, and Cu2+ to form organic–metal complexes.

Amino acids are organic ligands that can form complexes with metal ions. The chemical reaction formulas for amino acids with Pb and Zn metal ions are as follows:

NH2 + Pb2+ = [Pb(NH2)4]2+

NH2 + Zn2+ = [Zn(NH2)4]2+

A carboxyl group is a functional group containing a carbonyl group and a hydroxyl group, with the chemical formula R-COOH, where R can represent an alkyl, aryl, or other organic substituent. The carboxyl groups are acidic and react with metal ions to produce metal carboxylates and water. For example:

2RCOOH + Pb2+ → (RCOO)2Pb + 2H+

RCOOH + Zn2+ → RCOOZn + H+

The chemical reaction formula of thiol groups compounds and lead–zinc metal ions:

CH3CH2SH + Pb2+ → CH3CH2SPb + H+

CH3CH2SH + Zn2+ → CH3CH2SZn + H+

4.3. Complexation and Reduction of Organic Matter

Organic matter can provide abundant chelating agents such as carboxyl, phenol, and thiol groups, which form stable organic matter mineralization with metal ions, thereby reducing their hydration energy and increasing their migration ability. Following complex formation, under special geological background conditions—such as redox reactions and elevated temperatures—lead and zinc metals precipitate to form ore deposits. The general expression for the precipitation of complexes with H2S is as follows:

Pb Zn Complexes (Liquid) + H2S → PbS↓ + ZnS↓

The precipitation patterns of lead and zinc still vary in different strata and fluids. For example, in carbonate strata, the chemical expression for precipitation with calcium and magnesium ions is as follows [84]:

CH4 + ZnCl2 + SO42− + Mg2+ + CaCO3 → ZnS↓ + CaMg(CO3)2 + 2Cl− + H2O + 2H−

In hydrocarbon fluids, the ideal precipitation pattern for lead and zinc is

Natural gas + H2S + [PbCl3−] (Complexes) + [ZnCl3−] (Complexes) → Natural gas + PbS↓ + ZnS↓ + 2Cl−

In formations with evaporite layers, when hydrocarbon-bearing fluids encounter lead–zinc complexes and undergo redox reactions, it results in the precipitation of lead–zinc metal:

Hydrocarbons + CaSO4 + [PbCl3−] (Complexes) + [ZnCl3−] (Complexes) → Altered hydrocarbons + Bitumen + 2CaSO4 + PbS↓ + ZnS↓ + 6Cl−

Li [52] demonstrated in related research that if a paleo-oil reservoir was disrupted by tectonic uplift, liquid oil underwent oxidation and degradation under shallow surface conditions, generating abundant organic acids, which restore the sulfate (reduction) in the Pb–Zn-containing formation fluid to form hydrogen sulfide. The chemical reactions are as follows:

SO42− + C6H5CH3 → C6H2COOH + HS− + 2H2O

The generated hydrogen sulfide then reacts with the Pb–Zn elements carried in the fluid, leading to Zn-Pb precipitation and mineralization. The chemical reactions are as follows:

HS− + (Zn,Pb)Cl2 → (Zn, Pb)S + H+ + 2Cl−

5. Discussion and Outlook for Xicheng

5.1. Existing Research Characteristics and Issues

Recent studies on the Xicheng ore concentration area indicate that its deposit type remains a sedimentary exhalative (Sedex)-hydrothermal brine (non-magmatic) overprinting and reworking deposit, rather than a late metamorphic–deformational orogenic (magmatic–hydrothermal-influenced) type. Trace element characteristics of its sulfides indicate that its mineralization has no obvious correlation with magmatic hydrothermal activity, and the mineral formation temperature falls under a moderate–temperature environment [22]. Therefore, under such a metallogenic model and temperature conditions, the role of organic matter throughout the ore-forming process includes adsorption, complexation, and subsequent precipitation-release of lead, zinc, and other metals. However, the current research on organic matter in the Xicheng Pb–Zn ore field still faces certain challenges.

Presently, the understanding of the origin of organic matter remains incomplete, and various viewpoints exist on the analysis of organic matter sources in the Xicheng region: organic matter is believed to come from the carbonaceous limestone, mudstone and mud shale of the Middle Devonian Anjiacha Group and Xihanshui Group [36]; the organic matter comes from the carbonate rocks of the underlying Bikou Group and Silurian strata [36]; the organic matter comes from the input of lower organisms. However, analyzing the source of organic matter only from the characteristics of kerogen, organic carbon, and biomarker compounds is relatively one-dimensional because, throughout geological history, organic matter has inevitably undergone a series of alterations including oxidation, biodegradation, and high-temperature and high-pressure geological tectonic movements. Therefore, it is necessary to comprehensively analyze the isotopic data characteristics, mineralogical characteristics of organic matter, and evolutionary trends of the organic compounds themselves to restore the mineralization of Pb, Zn, and other metal elements by organic matter during geological history.

The interaction and influence between organic matter and inorganic metal elements have not received sufficient attention or consideration. Within the overall organic metallogenic system of the Xicheng ore cluster, the coupling relationship between organic matter and metallic elements at different stages constitutes the key and core of this theory. Its absence has limited the applicable scope and effectiveness of the organic metallogenic theory.

There remains unclear understanding regarding whether metal elements such as lead and zinc, after forming metal–organic complexes, undergo multi-stage precipitation and mineralization. The formation of super-large deposits often exhibits characteristics of multi-stage mineralization, particularly in areas where several super-large Pb–Zn deposits are distributed within the Xicheng ore cluster. This is also a main reason for divergent views on mineralization stages and metallogenic models in the study of this region. Therefore, future research should focus on the sulfur isotope characteristics of different forms of sulfur-bearing minerals, the fractionation effect of sulfur, combined with mineralogical and mineralization chronology characteristics. This would clarify the multi-stage precipitation and exsolution characteristics of lead–zinc minerals and principal mineralization stages.

The main sources and formation stages of H2S remain unclear. In the process of lead–zinc metal sulfide mineralization, the source and presence of H2S is a key factor. However, related organic–geochemical research does not provide sufficient theoretical basis for H2S formation. For instance, the argument that microorganisms degrade seawater sulfate to form H2S poses many problems. Firstly, the sulfate content in normal seawater is relatively low (2.709‰), and even if bacteria were highly active and rapidly reduce the entire sulfate in seawater, it is difficult to produce H2S adequate for the combination and precipitation of lead–zinc minerals [85]. Secondly, the continuous accumulation of H2S is toxic to the microorganisms themselves, which inhibits the large-scale occurrence of such a reaction [85].

Understanding the migration and evolution of organic matter in the Xicheng ore concentration area remains inadequate. After the deposition of the ore source layer in the Xicheng ore concentration area, it experienced a series of subsequent tectonic deformations, magmatic intrusions, and fluid activity [86,87,88], resulting in different degrees of thermal cracking, cracking, and oxidation of organic matter, causing structural and compositional changes in organic matter and the generation of hydrocarbon fluids of different types and maturity. These hydrocarbon fluids subsequently migrate under geological driving forces, reacting with lead, zinc, and other metal ions through adsorption, complexation, reduction, and other reactions, ultimately promoting the precipitation and mineralization of lead–zinc metals. Therefore, understanding the migration and evolution of organic matter in the Xicheng area is of great significance for clarifying the organic matter mineralization process.

5.2. Key Aspects of Xicheng Organic Research

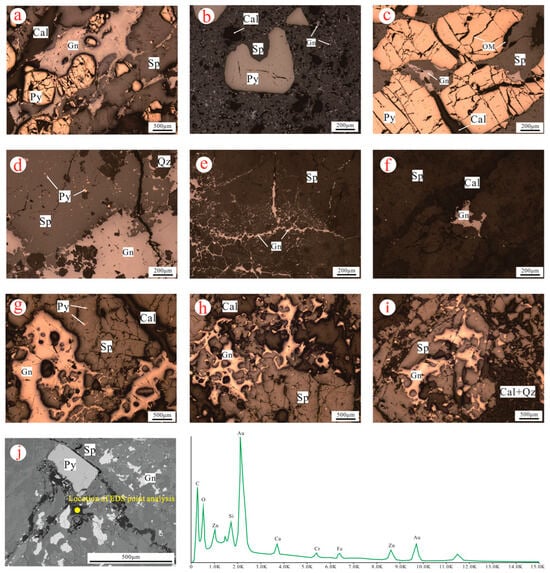

The formation and evolution of sulfide compounds and minerals is a key focus of organic matter mineralization research in Xicheng Pb–Zn. Existing research data from Xicheng indicate that lead–zinc deposits such as those in Lijiagou, Bijiashan, and Luoba differ in the macro- and microscopic characteristics of sulfide minerals within their ores. Based on petrographic characteristics (Figure 4), the lead–zinc ore in Lijiagou contains abundant pyrite (Figure 4a–c), and the fissures are well developed and distributed in a zonal pattern within the sphalerite. In contrast, sphalerite shows uniform distribution with few fractures, suggesting a mineral formation sequence of pyrite–sphalerite–galena. In the mineral assemblage of Luoba (Figure 4d–f), the pyrite content is relatively low, and galena and sphalerite either exhibit mutual grain-boundary textures (Figure 4d) or occur as veinlets filling fractures within sphalerite (Figure 4e), indicating two distinct stages of mineralization. In the mineral distribution of Bijiashan (Figure 4g–i), galena is mostly distributed allotriomorphically within the sphalerite (Figure 4g), and most of the triangular pores are developed (Figure 4h). Calcite and quartz are observed filling mineral pores (Figure 4i); this texture reflects a paragenetic sequence of sphalerite followed by galena.

Figure 4.

(a–j) Microscopic characteristics of minerals in the Xicheng lead–zinc ore field. Mineral abbreviations: Sp—sphalerite; Py—pyrite; Gn—galena; Cal—calcite; Qz—quartz.

Notably, the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) image of the Lijiagou lead–zinc ore sample (Figure 4j) depicts pyrite with a euhedral crystal structure that is crushed by later tectonic deformation, while sphalerite and galena were heterogeneously distributed in the carbonate minerals. This texture reflects a paragenetic sequence of pyrite–galena/sphalerite. Fractures are filled with Au–Zn-bearing carbonaceous–metallic fluids, indicating the migration of organic–metal complexes during middle-to-late stages. This provides a new perspective for understanding the timing of Pb–Zn precipitation and mineralization.

Zhao [59] believed that in a sedimentary environment, sulfate ions preferentially combine with iron to form pyrite when the iron content is sufficient, and after the iron is consumed, it combines with organic matter to form organic sulfur. It can be inferred that in the entire sedimentary environment of Xicheng, the iron content in the Changba–Lijiagou area is high, while that in Luoba and Bijiashan is low. Therefore, in subsequent research, refined analytical methods should be employed to precisely determine various indicator parameters under different mineral species and forms. This will identify the source of Pb and Zn metal ions, the source and consumption of iron, and the formation stages of H2S and the precipitation period of its combination with lead, zinc, and other metal ions. This will provide data support for the analysis of the general laws and main causes of Pb–Zn mineralization in the Xicheng area.

6. Conclusions

In the study of organic matter mineralization in the Xicheng lead–zinc ore field, the overall characteristics of organic matter show a trend of increasing total organic carbon content closer to the ore bodies, and the saturated hydrocarbons constitute a relatively high proportion of the soluble organic matter. Some biomarker parameters, [ω(∑C22−)/ω(∑C22+), ω(tricyclic terpanes)/ω(tetracyclic terpanes), ω(C20 + C21)/ω(C23 + C24), and ω(terpanes)/ω(steranes)], also exhibit clear positive or negative correlation with lead and zinc metal elements, collectively indicating a close relationship between organic matter and lead–zinc mineralization. Future research on organic-involved mineralization in the Xicheng area should focus on the characteristics of the sedimentary environment and the sulfur formation period during the early stages of mineralization. This will help clarify the distinct stages of lead–zinc mineralization in the Xicheng deposits and will provide fundamental data for establishing general mineralization patterns and deposit-specific models within the region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.N. and D.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y. and Z.M.; Data organization, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Gansu Provincial Department of Science and Technology (24YFGA019), Gansu Nonferrous Metal Geological Exploration Bureau managed projects (YSJG2025-03, YSJG2025-02, and YSJD2022-15), Key Talent Project of Organization Department of Gansu Provincial Party Committee (2024RCXM62), and Innovation Project of Gansu Provincial Bureau of Geology and Mineral Exploration & Development (2023CX12).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Assistant Editor and two anonymous referees for comments which helped in improving our manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bai, R.L.; Guo, D.B.; Chen, X.F.; Hu, P.C.; Zhang, C.X.; Feng, F.; Xia, X.Y.; Cao, H.W.; Yang, M.X.; Yang, L.J. Research Progress and Prospecting Directions of edimentary-Hosted Lead-Zinc Deposits in the Qinling etallogenic Belt, China. Geol. J. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.L.; Qi, S.J.; Li, Y.; Xue, C.J. Genesis of albitites in Changba Pb-Zn Ore deposit. Geol. Geochem. 1998, 2, 29–33, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.Y.; Wang, D.P.; Wei, Z.G. Fault controlling in Luoba lead-zinc deposit, Gansu province. Geol. Prospect. 2005, 6, 41–44, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.L.; Sun, B.N.; Yan, D.F.; Dong, C.; Hou, S.G.; Gao, H.G. The Tectonic Evolution of the Xicheng Ore Concentrated Area in Oinling Mountain and Its Relation to Lead-Zinc Mineralization. Acta Geol. Sin. 2012, 86, 1291–1297, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.T.; Zhang, C.Q. Editorial for Special Issue “Genesis and Evolution of Pb-Zn-Ag Polymetallic Deposits”. Minerals 2024, 14, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.J.; Dai, S.; Guo, D.B.; Li, H.L.; Cao, X.F.; Yi, Y.L.; Ma, Z.T.; Ma, Y.Z. Mineralization of gold and antimony in Pb-Zn deposit periphery of Luoba, West Qinling, China: Evidence from in situ trace elements and C-O-S isotopes. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2025, 41, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.L. Preliminary discussion on geological characteristics and genesis of lead-zinc deposits in Xicheng area, Gansu Province. Northwestern Geol. 1980, 3, 40–46, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.K. Types and genesis of Xicheng lead-zinc deposit. Geol. Prospec. 1983, 7, 2–10, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ma, G.; Beaudoin, G. Geological and geochemical characteristis of the Changba and Dengjiashan Pb-Zn deposits in the Qinling orogenic belt, China. In Mineral Deposit Research: Meeting the Global Challenge; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.M.; Deng, J.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Lai, X.G. Nature, diversity and temporal–spatial distributions of sediment-hosted Pb―Zn deposits in China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2014, 56, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.P.; Zhou, Z.G.; Xiao, J.D.; Chen, B.Y.; Zhao, X.W.; Xin, J.R.; Li, X.; Du, Y.S.; Xin, W.J.; Li, G.C. Characteristics of Devonian sedimentary facies in the Qinling mountains and their tectono-palaeo geographic significance. J. Southeast Asian Earth Sci. 1989, 3, 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.W.; Li, F.D.; Sun, N.Y. The basic geological features and genesis of Qinling type of Stratabound Lead-Zinc sulfide deposit. Northwest Geosci. 1987, 5, 83–96, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Zhao, H.S.; Wu, J.M. Discussion on controlling conditions of metallogenesis and enrichment regularities of mineralization of lead-zinc deposits in Changba Lijiagou area. Miner. Resour. Geol. 1988, 2, 1–9, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. Discussion on the genesis of West Qinling lead-zinc deposit. Northwestern Geol. 1989, 3, 22–30+21, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.; Cheng, H.S.; Su, W.M.; Chen, D.Y. Source of ore-forming metals for lead-zinc deposits in the Xicheng ore field, Gansu. Sci. Geol. Sin. 1992, 2, 149–159, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.X.; Bai, R.L.; Guo, D.B.; Chen, X.F.; Yang, L.J.; Yang, M.X.; Xia, X.Y.; Wang, K.N. Tracing the Genesis and Mineralization Mechanism of the Xiejiagou Pb–Zn Deposit in Gansu, China: Insights from Trace Element Analysis, Fluid Inclusion Studies, and the Sulfur Isotopic Composition. Geol. Ore Depos. 2024, 66, 663–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L. Qinling-Type Lead-Zinc Deposits in China; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, S.X.; Pu, F.C.; Wu, Y.H.; Lu, J.J.; Ou, K.; Li, Y.; Yu, P.P. TI Critical metals Ga and Ge enrichment in the last-stage and low-temperature sphalerite from the Guojiagou Zn-Pb deposit, western Qinling Orogen, NW China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2025, 179, 106494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.G.; Ni, P.; Wang, G.G.; Zhang, T. Identification and significance of methane-rich fluid inclusions in Changba Pb-Zn deposit, Gansu province. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2008, 24, 2105–2112. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, G.Z.; Zhao, C.B. Investigating rock permeability effects on mineralization locations of the Changba-Lijiagou Pb-Zn deposit, Gansu, China: Modelling of ore-forming mechanisms through the dual length-scale approach. Ore Geol. Rev. 2025, 177, 106445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.C.; Han, S.J.; Zheng, Y.; Zeng, Z.J.; Chen, T.W.; Zhang, G.B. Geology, geochemistry, zircon and garnet U-Pb geochronology, and C-O-S-Pb-Hf isotopes of the Guojiagou Pb-Zn deposit, West Qinling Belt, Central China: New constraints on district-wide mineralization. J. Geochem. Explor. 2024, 264, 107534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.B.; Bai, R.L.; Dai, S.; Chen, X.F.; Niu, Y.J.; Shang, L.L.; Mujahed, M.A.; Guo, X.G.; Zhang, C.X.; Wang, B.L. Trace elements of sulfides in the Dengjiashan Pb–Zn deposit from West Qinling, China: Implications for mineralization conditions and genesis. Geol. J. 2023, 58, 2913–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Liu, X.; Guo, H.; Hu, W. Mineral Chemistry and In Situ LA-ICP-MS Titanite U-Pb Geochronology of the Changba-Lijiagou Giant Pb-Zn Deposit, Western Qinling Orogen: Implications for a Distal Skarn Ore Formation. Minerals 2024, 14, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.J.; Gao, Y.B.; Zeng, R.; Chi, G.X.; Qing, H.R. Organic petrography and geochemistry of the giant Jinding deposit, Lanping basin, northwestern Yunnan, China. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2007, 23, 2889–2900. [Google Scholar]

- Disnar, J.R.; Sureau, J.F. Organic matter in ore genesis: Progress and perspectives. Org. Geochem. 1990, 16, 577–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lei, Q.; Huang, Z.; Liu, G.; Fu, Y.; Li, N.; Liu, J. Genetic Relationship between Mississippi Valley-Type Pb–Zn Mineralization and Hydrocarbon Accumulation in the Wusihe Deposits, Southwestern Margin of the Sichuan Basin, China. Minerals 2022, 12, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williford, K.H.; Grice, K.; Logan, G.A.; Chen, J.; Huston, D. The molecular and isotopic effects of hydrothermal alteration of organic matter in the Paleoproterozoic McArthur River Pb/Zn/Ag ore deposit. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 301, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, D.L.; Song, Y.C.; Hou, Z.Q. The world-class Jinding Zn–Pb deposit: Ore formation in an evaporite dome, Lanping Basin, Yunnan, China. Miner. Depos. 2017, 52, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marikos, M.A.; Laudon, R.C.; Leventhal, J.S. Solid insoluble bitumen in the Magmont West orebody, Southeast Missouri. Econ. Geol. 1986, 81, 1983–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gize, A.P.; Barnes, H.L. The organic geochemistry of two Mississippi Valley-type lead-zinc deposits. Econ. Geol. 1987, 82, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.M. Kerogen as a Source of Sulfur in MVT Deposits. Econ. Geol. 2014, 110, 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavender, B.D.; Shelton, K.L.; Schiffbauer, J.D. An atypical orebody in the Brushy creek mine, viburnum ternd, MVT district, Missouri early Cu-(Ni-Co)-Zn-rich ores at the lamotte sandstone/bonneterre dolomite contact. Econ. Geol. 2016, 111, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.Y.; Liu, Q.Y.; Zhu, D.Y. Hydrothermal catalytic conversion and metastable equilibrium of organic compounds in the Jinding Zn/Pb ore deposit. Geochim. Et Cosmochim. Acta 2021, 307, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.W.; Li, L.; Li, C.L.; Li, S.R.; Santosh, M.; Masroor, A.; Hou, Z.Q. The genesis of bitumen and its relationship with mineralization in the Erdaokan Ag-Pb-Zn deposit from the Great Xing’an Range, northeastern China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 139, 104464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Ma, L.H. Organic Geochemistry of the Bijiashan lead-zinc deposit(II)-features of bulk organic matter and sources of ore-forming materials. Acta Mineral. Sin. 1996, 1, 82–88, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.L. Organic geochemical characters and metallogenesis of Xicheng Pb-Zn ore field, Gansu, China. Acta Geol. Gansu 1999, 2, 58–64, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.J.; Cui, Y.L. Sedimentary Environment Interpreted by the Characteristics of Organic Matters in Xicheng Ore field. J. Lanzhou Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2000, 1, 125–130, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Zhu, L.D.; Pang, Y.C.; Xiong, Y.Z.; Fu, X.G. Simulation Experiment Research on Biomineralization of Xicheng Lead and Zinc Deposit, Qinling. Miner. Depos. 2002, 21, 423–426. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.C.; Zhu, L.D.; Lin, L. Organic Mineralization of Lead-Zinc Deposits in Devonian System, Xicheng Ore Field. Earth Sci. 2003, 2, 201–208, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Pang, Y.C.; Zhu, D.C.; Fu, X.G.; Zhu, L.D. The role of organic fluid during the migration of ore-forming elements: A case of simulation experiment for Luoba lead-zinc deposit, Western Qinling. J. Mineral. Petrol. 2008, 2, 51–55, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Qin, S.J.; Sun, Y.Z.; Tang, Y.G. Early hydrocarbon generation of algae and influences of inorganic environments during low temperature simulation. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2008, 26, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Z.; Qin, S.J.; Li, Y.H.; Lin, M.Y.; Ding, S.L. Explanation for peat-forming environments of Seam 2 and 9-2 based on the maceral composition and aromatic compounds in the Xingtai Coalfield, China. J. Coal Sci. Eng. 2009, 15, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Z.; Qin, S.J.; Zhao, C.L.; Kalkreuthc, W. Experimental study of early formation processes of macerals and sulfides. Energy Fuels 2010, 24, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.; Hu, R.Z.; Bi, X.W.; Liu, H.; Xiao, J.F.; Fu, S.L.; Santosh, M.; Tang, Y.Y. The source of organic matterand its role in producing reduced sulfur for the giant sedimenthosted Jinding zine-lead deposit, Lanping Basin, Yunnan Southwest China. Econ. Geol. 2021, 116, 1537–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtig, N.C.; Hanley, J.J.; Gysi, A.P. The role of hydrocarbons in ore formation at the Pillara Mississippi Valley-Type Zn-Pb deposit, Canning Basin, Western Australia. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 102, 875–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.C.; Yang, Z.M.; Zhuang, L.L. Enrichment of Mississippi Valley-type (MVT) deposits in the Tethyan domain linked to organic matter-rich sediments. Sci. China-Earth Sci. 2023, 66, 2853–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, G.Y.; Li, S.W.; Li, R.X. Metal-organic complex as a Pb/Zn carrier in the formation of Mississippi Valley-Type (MVT) Pb-Zn deposits: A case study of the Mayuan Pb-Zn ore district, the northern margin of the Yangtze Block, Central China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2025, 180, 106570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.Q.; Mao, J.W.; Ouyang, H.G.; Sun, J. The genetic relationship between hydrocarbon systems and Mississippi Valley-type Zn-Pb deposits along the SW margin of Sichuan Basin, China. Int. Geol. Rev. 2013, 55, 941–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.J.; Chi, G.X.; Li, Z.D.; Dong, X.F. Geology, geochemistry and genesis of the Cretaceous and Paleocene sandstone- and conglomerate-hosted Uragen Zn-Pb deposit, Xinjiang, China: A review. Ore Geol. Rev. 2014, 63, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Xiang, J.J.; Jin, Y.L.; Cen, W.P.; Zhu, G.Y.; Shen, C.B. Petroleum evolution and its genetic relationship with the associated Jinding Pb-Zn deposit in Lanping Basin, Southwest China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2024, 294, 104620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhou, J.X.; Hu, Y.Z.; Xu, S.H.; Shi, S.B.; Wen, Y.M.; Nie, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, K.; Tan, X.L.; et al. The biomarker signatures in the Niujiaotang sulfide ore field: Exploring the role of organic matter in ore formation. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2026, 183, 107616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.X.; Mao, J.W.; Zhao, B.S.; Chen, B.Y.; Liu, S.W. A Review of the Role of Hydrocarbon Fluid in the Ore Formation of the MVT Pb-Zn Deposit. Adv. Earth Sci. 2021, 36, 335–345, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.X.; Dong, S.W.; Dan, L.H. Tectonically driv-en organic fluid migration in the Dabashan Foreland Belt: Evi-denced by fibrous calcite with organic inclusions. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013, 75, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, G.Y.; Li, S.W.; Li, R.X. Mineralization Process of MVT Zn-Pb Deposit Promoted by the Adsorbed Hydrocarbon: A Case Study from Mayuan Deposit on the North Margin of Sichuan Basin. Minerals 2023, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galina, V.; Janet, M.H.; Amber, J.M.; Jarrett, N.W.; Jochen, J.B. Reassessment of thermal preservation of organic matter in the Paleoproterozoic McArthur River (HYC) Zn-Pb ore deposit, Australia. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 133, 104129. [Google Scholar]

- Marynowski, L.; Czechowski, F.; Simoneit, B.R.T. Phenylnaphthalenes and polyphenyls in Palaeozoic source rocks of the Holy Cross Mountains Poland. Org. Geochem. 2001, 32, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marynowski, L.; Rospondek, M.J.; Reckendorf, R.M.; Simoneit, B.R.T. Phenyldibenzofurans and phenyldibenzothiophenes in marine sedimentary rocks and hydrothermal petroleum. Org. Geochem. 2002, 33, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.J.; Qin, S.J.; Zhao, C.L.; Sun, Y.Z.; Balaji, P.; Chang, X.C. Origin and geological implications of super high sulfur-containing polycyclic aromatic compounds in high-sulfur coal. Gondwana Res. 2021, 96, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.J.; Qin, S.J.; Shen, W.C.; Sun, Y.Z. Significant influence of different sulfur forms on Sulfur-containing polycyclic aromatic compound formation in high-sulfur coals. Fuel 2023, 332, 125999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Alexander, R.; Fazeelat, T.; Pierce, K. Geosynthesis of dibenzothiophene and alkyl dibenzothiophenes in crude oils and sediments by carbon catalysis. Org. Geochem. 2009, 40, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, R.H.; Wang, T.G.; Li, M.J.; Xiao, Z.Y.; Zhang, B.S.; Huang, S.Y.; Shi, S.B.; Wang, D.W.; Deng, W.L. Dibenzothiophenes and benzo[b]naphthothiophenes: Molecular markers for tracing oil filling pathways in the carbonate reservoir of the Tarim Basin, NW China. Org. Geochem. 2016, 91, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Y.; Worden, R.H.; Jin, Z.J.; Liu, W.H.; Liu, J.; Gao, B.; Zhang, D.W.; Hu, A.P.; Yang, C. TSR versus non-TSR processes and their impact on gas geochemistry and carbon stable isotopes in Carboniferous, Permian and Lower Triassic marine carbonate gas reservoirs in the Eastern Sichuan Basin, China. Geochim. Et Cosmochim. Acta 2013, 100, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, R.H.; Smalley, P.C. H2S-producing reactions in deep carbonate gas reservoirs: Khuff Formation, Abu Dhabi. Chem. Geol. 1996, 133, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Worden, R.H.; Bottrell, S.H.; Wang, L.; Yang, C. Thermochemical sulphate reduction and the generation of hydrogen sulphide and thiols (mercaptans) in Triassic carbonate reservoirs from the Sichuan Basin, China. Chem. Geol. 2003, 202, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Qin, H.; Li, G. Fluid Mixing, Organic Matter, and the Origin of Permian Carbonate-Hosted Pb-Zn Deposits in SW China: New Insights from the Fuli Deposit. Minerals 2024, 14, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machel, H.G. Bacterial and thermochemical sulfate reduction in diagenetic settings—Old and new insights. Sediment. Geol. 2001, 140, 143–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Qi, H.W.; Bi, X.W.; Hu, R.Z.; Qi, L.K.; Yin, R.S.; Tang, Y.Y. Mercury and sulfur isotopic composition of sulfides from sediment-hosted lead-zinc deposits in Lanping basin, Southwestern China. Chem. Geol. 2021, 559, 119910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, S.Y. Microbial geochemistry of sulfur and its implication to geology. Geol. Chem. Miner. 1993, 15, 101–106, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Huang, K.M.; Chen, S.K. Sulfate reduction and iron sulfide mineral formation in the southern east China sea continental slope sediment. Deep-Sea Res. Part I-Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2002, 49, 1837–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billon, G.; Thoumelin, G.; Barthe, J.F.; Fischer, J.C. Variations of fatty acids during the Sulphidization process in the Authie bay sediments. J. Soils Sediments 2007, 7, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.Z.; Raimondi, I.M.; Schalch, V.; Rodrigues, V.G.S. Assessment of the use of organic composts derived from municipal solid waste for the adsorption of Pb, Zn and Cd. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 226, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, G.; Porter, J.F. Equilibrium parameters for the sorption of copper, cadmium and zinc ions onto peat. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 1997, 69, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddad, Z.; Gerente, C.; Andres, Y.; Cloirec, P.L. Adsorption of several metal ions onto a low-cost biosorbent: Kinetic and equilibrium studies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 2067–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hass, A.; Lima, I.M. Effect of feed source and pyrolysis conditions on properties and metal sorption by sugarcane biochar. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2018, 10, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricordel, S.; Taha, S.; Cisse, I.; Dorange, G. Heavy metals removal by adsorption onto peanut husks carbon: Characterization, kinetic study and modeling. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2001, 24, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratschbacher, L.; Hacker, B.R.; Calvert, A.; Webb, L.E.; Grimmer, J.C.; Mc-williams, M.O.; Ireland, T.; Dong, S.W.; Hu, J.M. Tectonics of the Qinling (Central China): Tectonostratigraphy, geochronology, and deformation history. Tectonophysics 2003, 366, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; Guo, S. Cellulose/chitin beads for adsorption of heavy metals in aqueous solution. Water Res. 2004, 38, 2643–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmykova, Y.; Strömvall, A.M.; Steenari, B.M. Adsorption of Cd, Cu, Ni, Pb and Zn on Sphagnum peat from solutions with low metal concentrations. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 152, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, W.E.; Franca, A.S.; Oliveira, L.S.; Rocha, S.D. Untreated coffee husks as biosorbents for the removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 152, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.C.; Aldrich, C. Biosorption of heavy metals from aqueous solutions with tobacco dust. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 5595–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Saeed, A.; Zafar, S.I. FTIR spectrophotometry, kinetics and adsorption isotherms modeling, ion Exchange, and EDX analysis for understanding the mechanism of the Cd2+ and Pb2+ removal by mango peel waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 164, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.; Guo, X.; Liang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, J. Biosorption of heavy metals from aqueous solutions by chemically modified orange peel. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 185, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shan, B.; Tang, W.; Zhu, Y. Comparison of cadmium and lead sorption by Phyllostachys pubescens biochar produced under a low-oxygen pyrolysis atmosphere. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 238, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.H.; Spinks, S.C.; Glenn, M.; MacRae, C.; Pearce, M.A. How carbonate dissolution facilitates sediment-hosted Zn-Pb mineralization. Geology 2021, 49, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.B.; Xue, C.J.; Zeng, R. Geochemistry of organic matters in the Jinding zinc-lead deposit. Lanping Basin, Northwest Yunnan Province. Geochimica 2008, 3, 223–232, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.D.; Li, S.G.; Chen, Y.D.; Li, Y.J. Timing of the synorogenic granoids in the South Qinling, Central China: Constrints on the evo-lution of the Qining-Dabie orogenic belt. J. Geol. 2002, 11, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Chen, R.X.; Zhao, Z.F. Chemical geodynamics of continental subduction-zone metamorphism: Insights from studies of the Chinese Continental Scientific Drilling (CCSD) core samples. Tectonophysics 2009, 475, 327–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.P.; Zhang, G.W.; Neubaue, R.F.; Liu, X.M.; Johann, G.; Christoph, H. Tectonic evolution of the Qinling orogeny, China: Review and synthesis. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2011, 41, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.