Abstract

Geothermal water from different orogenic belts, surrounding rock weathering, and salt-forming elements sourced from surface basins jointly shape the hydrochemical characteristics, evaporation evolution sequences, and prospects for subsequent development and utilization of terminal salt lakes. In view of the lack of research on the metallogenic model of a single salt lake in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, this paper selects the Nie’er Co Salt Lake, a terminal lake in Northern Tibet, and systematically samples the water, river sediments, and surrounding rocks of the upper reaches of the recharge river, the Xiangqu. The Piper, Gibbs, and Durov, combined with ion ratio analysis, correlation analysis, PHREEQC, quantitative calculations of surrounding rock weathering and tributary contributions to salt-forming elements, were applied to comprehensively characterize groundwater hydrochemistry and surface water system runoff, and clarify the evolution of salt-forming elements in the terminal lake. The driving mechanism of surface runoff and surrounding rock weathering on ion enrichment in the terminal lake was revealed. The Nie’er Co Salt Lake in Tibet evolves from Ca/Na-HCO3 springs to Na-SO42− via dilution, rock leaching, and evaporation. Tributaries contribute 39.6%, 8.2%, and 52.3% of the major ions. Silicate weathering dominates (75%–80%), shifting to evaporite–carbonate inputs. The overall performance is dominated by silicate weathering. The contribution rate of silicate weathering decreases, and the trend of evaporite–carbonate weathering increases. The evolution of surface runoff can be divided into a tributary ion concentration growth section, a mixed ring section (evaporation concentration–TDS increase), and a terminal lake sedimentary section (enrichment evaporation to form the salt lake), revealing that multi-branch superposition and surrounding rock weathering synergistically affect the formation of salt lake hydro-chemical types.

1. Introduction

Endorheic basins are predominantly distributed in arid and semi-arid regions, evolving under the synergistic influence of multiple factors, including tectonics, climate, and hydrological processes. They constitute entirely closed systems [1,2]. Tectonic activity generates relatively low-lying areas, mainly distributed in rift valleys, foreland basins, and graben basins, and are surrounded by varied mountain rock formations. In these basins, stable runoff, atmospheric precipitation, and glacial meltwater from higher elevations converge in depressions, forming enclosed lake basins [3]. Tectonic forces create relatively low-lying areas, predominantly developing within rift valleys, foreland basins, and graben basins, surrounded by diverse mountainous rock formations. Within these basins, stable runoff replenishment, atmospheric precipitation, and glacial meltwater converge from higher elevations into depressions, forming enclosed lake basins. Under arid conditions, with no drainage outlets, evaporation becomes the sole mechanism for water loss. When evaporation outpaces recharge, lake salinity elevates progressively, facilitating the formation of saline lakes or salt lakes. With the gradual decline of recharge, the lake undergoes areal contraction and eventual desiccation, evolving into dry salt lakes or saline–alkali soils [4].

Terminal water lakes across diverse climatic zones and tectonic settings worldwide exhibit varied hydrochemical types and evolutionary mechanisms due to differences in recharge conditions, rock-water interactions, and evaporation rates [5,6]. The Great Salt Lake, situated in the arid interior of North America, is a closed, hypersaline terminal water lake. Its catchment experiences arid conditions with minimal rainfall, where annual evaporation far exceeds precipitation. Fed by seasonal rivers, its salinity exhibits pronounced sensitivity to climatic fluctuations [7,8,9]. Lake Eyre, situated in the heart of Australia’s inland desert, is a prototypical intermittent terminal water lake. Its replenishment relies on seasonal rivers and floods, leaving it dry for most periods. Salinity exhibits fluctuating characteristics depending on the source water: during dry spells, it becomes a salt–alkali desert. During floods, freshwater inflow lowers salinity to form a lake, yet extremely rapid evaporation leads to the precipitation of salt minerals [10,11]. Lake Turkana, situated in the northern part of the East African Rift Valley, is a transitional terminal lake in a semi-arid zone. Its evolution is driven by both tectonic activity and climatic fluctuations [12,13,14]. Qarhan Salt Lake, situated in the Qaidam Basin of China’s Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, is a sedimentary terminal lake in a high-altitude arid region. Its water supply relies on meltwater from the Kunlun Mountains and groundwater, resulting in highly mineralized water. Continued subsidence within the basin provides ample space for salt deposition [15,16,17].

The numerous lakes scattered across the Tibetan Plateau are predominantly endorheic bodies, maintaining their water balance through evaporation and remaining isolated from one another. As a typical terminal lake in the western Tibetan Plateau, Nie’er Co Lake’s hydrogeochemical evolution chronicles the integrated response to regional climate change, tectonic activity, and hydrological cycles. Current research on this salt lake encompasses its resource characteristics, paleoenvironment, paleoclimate, and geological structure [18]. In 2010, Liu Xifang and Zheng Mianping systematically elucidated the geological characteristics of the magnesium–boron deposits at Nie’er Co, proposing that boron originated from hydrothermal activity and rock weathering, subsequently forming independent boron deposits through arid evaporation [19]. In 2020, Wu Hao et al., integrating the tectonic evolution of the gabbroic intrusion within the Nie’er Co region, proposed that its formation resulted from crustal subsidence caused by plate subduction and collision, creating a rift basin [20]. Subsequent uplift of the Tibetan Plateau formed an endorheic basin, where salts from surrounding rock weathering and hydrothermal activity accumulated. Under arid conditions, this ultimately formed the modern terminal water salt lake. This ‘tectonically controlled, source-replenished, climate-driven’ lake formation model shares common characteristics with other typical Tibetan salt lakes. Reviewing the existing literature reveals that research on Nie’er Co Salt Lake has established clear findings regarding resources, paleoenvironment, and tectonics, yet systematic studies on modern hydrological processes remain scarce. For the Nie’er Co terminal lake, the complete material migration chain of ‘water collection-sedimentation-lake formation’ remains unclear. In particular, the elemental response relationships between water quality entering rivers and sediments versus the surrounding rock have not been systematically studied, representing the gap this research aims to address. In-depth investigation into the evolutionary history of Nie’er Co provides a crucial case study for understanding the hydrodynamic mechanisms governing terminal lakes within the Tibetan Plateau’s endorheic basins. It also offers scientific foundations for sustainable water resource utilization and environmental conservation in the region.

In this study, the salt lake at the terminus of Nie’er Co was taken as the research object. Through a field geological survey, brine geochemical test and water body numerical simulation, the source, migration path and enrichment law of elements in the process from the surface to the terminal salt lake were systematically revealed. The contribution of the surface and the underground watershed and water–rock interaction was refined, and its evolution mechanism was analyzed, which provided a theoretical basis for the sustainable development of the salt lake.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Geological and Hydrogeological Settings

2.1.1. Geological Settings

Nie’er Co Lake is situated in the Western Qinghai–Tibet Plateau within the Ali Region, at 82°13′30″ east longitude and 32°17′00″ north latitude (Figure 1a). The basin is bounded by low-lying, gently sloping mountains, presenting a topography of elevated margins and a depressed central area. The lake surface lies at an elevation of 4398 m, surrounded by mountain ranges averaging 5000 m in height, with the modern salt lake covering an area of 24 km2. The area hosting Nie’er Co Lake is located within the Qiangtang Block of the Western Tibetan Plateau, along the southern margin of the Bangong Co Lake–Nujiang Suture Zone [19]. This region represents a multiphase, multi-layered composite structural belt, recording the complete evolutionary process of the Tethys Ocean Basin, including its breakup, intracontinental orogeny, and the subsequent uplift of the Tibetan Plateau. Tectonic activity in the study area is dominated by faulting and crustal uplift: faults generally exhibit a north–northwest-to-northwest strike, and the Gel-Guchang-Wuru Lake Fault Zone cuts across Nie’er Co Lake west to east, shaping the salt lake basin in the Northern Tibetan Plateau.

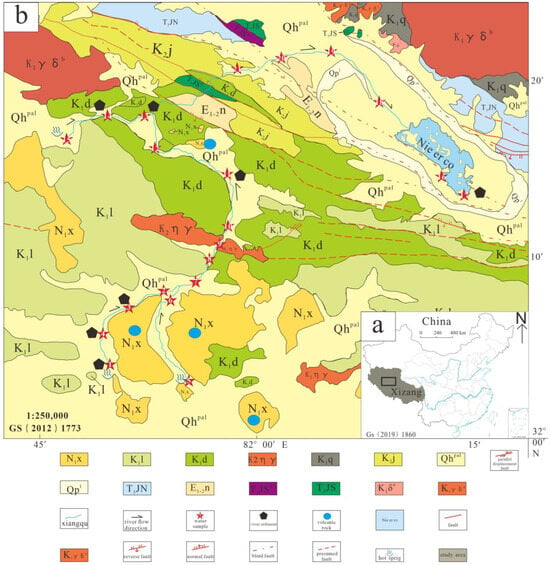

Figure 1.

Geological overview map of the study area. (a) Location map; (b) geological map. Abbreviations: Qhpal—Quaternary system, new series; Qpl—Quaternary system, Pleistocene; N1x—Neogene system, Miocene series, Xiongba formation; E1-2n—Paleogene system, Niubao formation; K2j—Cretaceous system, Jingzhushan formation; K1q—Cretaceous Qushenla formation; K1l—Lower Cretaceous Langshan formation; K1d—Lower Cretaceous Duoni formation; K2ηγ—Late Cretaceous Monzonitic granite; K1δa—Early Cretaceous fine-grained diorite; K1γδa—Early Cretaceous fine-grained granodiorite; K1γδb—Early Cretaceous medium-grained granodiorite; T3JS—Jurassic Shiquanhe ophiolite group; T3JSΦ1—Ultramafic accretionary complex of Shiquanhe ophiolite group; T3JN—Jurassic Nie’er Co tectonic complex.

The lithology within the Xinagqu River basin to the Nie’er Co terminal lake region comprises various tectonic lithologies of differing types, ages, and structures, while the southern part is dominated by volcanic strata [21]. The stratigraphic sequence from youngest to oldest is Q—Quaternary lacustrine deposits; N—Neogene andesite, volcanic tuff; E—Palaeogene conglomerate, quartz sandstone, mudstone, etc.; K—Cretaceous conglomerate, sandstone, limestone, andesite, basalt; and T—Jurassic ophiolite, basic basalt, gabbro, etc. The area lies near the Bangong Co–Nujiang suture volcano–magmatic arc, where igneous rocks have developed, primarily comprising extrusive volcanic rocks and intrusive granitic bodies. Intrusive rocks are distributed in the northern part of the mining area, with their extension direction aligning with regional tectonic trends. Granodiorite (γδ) bodies extend from east to west (Figure 1b).

2.1.2. Hydrogeological Settings

From a hydrological perspective, this region falls within the subarctic arid climate zone of the plateau, characterized by high altitude, cold temperatures, low oxygen levels, abundant sunshine, low annual precipitation (approximately 150 mm/year), and high evaporation rates (approximately 20,300 mm/year) [21]. The rainy season is concentrated between July and September, while winter and spring are dry and windy. The frost-free period lasts approximately 110 days annually. As a terminal endorheic salt lake, Nie’er Co Lake occupies a closed, endorheic basin. Its water sources derive from deep-seated fluid-released hot springs, snowmelt, and atmospheric precipitation. The catchment area features multiple seasonal rivers, primarily reliant on the Xiangqu River for replenishment. The upper reaches of the Xiangqu River exhibit extensive hot spring development, yielding substantial summer flows but freezing almost entirely during winter. The lake possesses no external outlet, making evaporation the sole means of drainage from the basin. It is a classic example of a terminal lake within an endorheic basin.

In July 2023, the researchers systematically sampled the salt lake brine, recharge river water, source spring water, and surrounding volcanic rocks and weathering materials of the Nie’er Co Salt Lake, including water samples and corresponding river sediments (Figure 2). At the same time, the flow velocity, width, and depth of the river were tested and recorded. The water samples were collected by plastic sample bottles, and the river sediment samples were dried and stored in sealed bags. The water temperature, pH, and TDS values of all water samples were measured on-site using a portable multi-parameter analyzer.

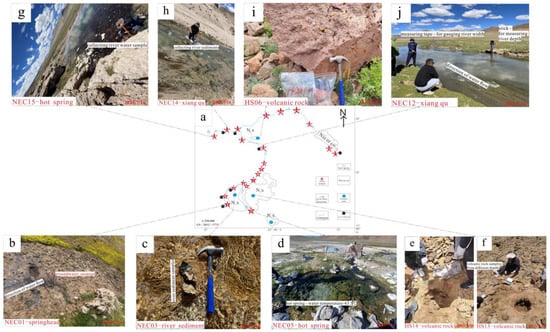

Figure 2.

Field sampling diagram. (a) Sampling route map for the Nie’er Co River Basin; (b,d,g,j) Tributary water samples and Xiangqu streamflow sampling, take water samples at the headwaters of each tributary, measure water temperature, use a tape measure to gauge river width, employ a wooden stick to determine river depth, design the frequency of paper slip deployment based on river width, and calculate flow velocity by measuring the time taken and distance travelled across the river surface within a specified period; (c,h) river sediment samples, at each river section corresponding to the water samples, collect sediment samples from the designated points; (e,f,i) volcanic rock samples, Quaternary deposits are widespread throughout the area, necessitating the identification of fresh bedrock and weathered material within sampling zones, alongside the excavation of pits to obtain rock samples at varying depths.

2.2. Testing Methods

The main and trace elements of water samples were measured using an ICPE-9000 (Shimadzu, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometer. The liquid samples containing elements Li+, Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, SO42−, and B were tested. The first step is to determine the salinity of the liquid sample. According to the salinity calculation, the sample with high salinity is diluted to 1 g/L, and 2.5% HNO3 solution is added (2.5% HNO3 solution is selected to prevent the precipitation of elements in the brine sample, and the second is based on ICP. The acidity of the instrument is measured, and the concentration effect is better), and the machine is measured. ICP has high sensitivity and high precision (RSD < 1%) and can be used for quantitative analysis of multiple elements at the same time. Cl−, CO32−, and HCO3− were determined by volumetric titration.

The major element test of river sediment, weathered rock, and weathered material samples was completed in the Beijing Institute of Geology, Nuclear Industry. The test instrument was an Axios-mAX X-ray fluorescence spectrometer. The test method was based on GB/T14506.28-2010 [22], and the accuracy of the major element data measured by XRF was better than 2%. The total rock trace elements were tested by Agilent 7700 (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) at the Beijing Institute of Geology, and the analysis accuracy was better than 5%. The test method is based on GB/T 14506.30-2010 [23] and HDB/T 3022-2018[24].

2.3. Analysis Methods

For hydrochemical data processing, the Piper diagram visually classifies the hydrochemical types by projecting the equivalent percentages of cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, and Na+ + K+) and anions (HCO3− + CO32−, and SO42−, Cl−) into the trilinear diagram. A Gibbs diagram is used to distinguish the relationship between TDS and the Na+/(Na++ Ca2+), Cl−/(Cl− + HCO3−) ratio, distinguish the hydrochemical control mechanism (atmospheric precipitation, rock weathering, evaporation, and concentration), and clarify the geochemical process of different river sections [25]. The forward end-member model quantifies the contribution rate of various types of surrounding rocks by calculating the main elements (Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, K+, SO42−, and Cl−) and shows the contribution rate of different rock weathering processes to water ions, which provides key data for analyzing the material cycle of the basin and evaluating the resource potential. PHREEQC (Phreeqc Interactive 3.7.3-15968) simulates the evaporation sequence of a water body, obtains the saturation index (SI) of minerals, judges the trend of mineral dissolution or precipitation in a water body, and reveals the dynamic process of water–rock interaction [26,27].

For sediment and surrounding rock data, a rare earth element distribution map and trace element spider diagram of sediment elements and surrounding rock samples are used. A rare earth element distribution map is drawn into a smooth curve by standardizing the concentration of rare earth elements (REE) in samples (chondrite standardization), reflecting the fractionation characteristics and distribution pattern of REE. The trace element spider diagram standardizes the concentration of various trace elements in the sample (crustal standardization) and shows the enrichment or loss characteristics of elements in the form of line charts. The rare earth element distribution map focuses on revealing the material source and differentiation process, which is suitable for sediment tracing. The trace element spider diagram can trace the geochemical process and tectonic background, and the combination of the two can comprehensively analyze the elemental geochemical behavior of the samples [28,29].

3. Results

3.1. Water Sample Data Results

Table 1 is a summary of the main ion concentrations of the river water in the study area. By studying the hydrochemical characteristics, it can be seen that the cation distribution of the water sample is more dispersed, the anion is more concentrated, and the content of bicarbonate is higher. The pH value of the hot spring water at the source of the three tributaries is weakly acidic, and the remaining water bodies range from seven to nine, showing slightly alkaline, salt lake brine > Xiangqu > tributary > hot spring water [26]. The rivers in the study area are mainly freshwater. TDS reflects the comprehensive index of water quality. The TDS value of water samples is 800 mg/L~1500 mg/L, which is significantly higher than the average value of global river water bodies (283 mg/L). The overall presentation is groundwater recharge < Xiangqu runoff < Nie’er Co Salt Lake. The order of the main ion concentration of the hot spring water in the tributary source is Ca > Na > Mg > K, HCO3− > SO42− > Cl > CO32−. The main river channel is Na > Ca > Mg > K, HCO3− > Cl > SO42− > CO32−. The terminal salt lake is Na >> Mg > K >> Ca, SO42− > Cl >> CO32−. The ion content of river water samples in the basin increased gradually from upstream to downstream. With the evaporation and concentration process, the main ion concentration of salt lake water was much higher than that of river water and spring water.

Table 1.

Hydrochemical data of surface-terminal salt lake water samples.

3.2. Solid Data Results

Based on the geochemical behavior of trace elements, some specific trace elements are often used to study specific geochemical processes and determine the provenance of sediments. This is restricted by many factors, such as the application, sediment sorting, and hydrogeochemical characteristics of various elements [30,31].

This study systematically determined the trace elements in river sediments within the Xiangqu stream channel and in the surrounding volcanic host rock. Trace element concentrations in sediments were significantly influenced by rock type, weathering processes, and diagenesis in the source area (Table 2). The trace element content of both samples exhibits a highly consistent distribution pattern overall, with K and Ti showing significantly elevated levels reaching tens of thousands of μg/g. These are followed by P, Ba, and Sr, while the remaining trace elements generally exhibit lower concentrations with pronounced variability. This similarity indicates that the material sources of the river sediments are closely linked to the surrounding volcanic rocks. Weathering products from these volcanic rocks may constitute the sedimentary source. Elements did not undergo significant selective enrichment or depletion during weathering, transport, and deposition, suggesting relatively stable migration behavior.

Table 2.

The content of trace elements in river sediments and volcanic rocks.

4. Discussion

4.1. Hydrological Characteristics

4.1.1. Water Quality Assessment Based on the WQI

The Water Quality Index (WQI) provides a quantitative assessment of water quality. In remote regions with minimal human intervention, the surface and the groundwater retain near-natural hydrochemical characteristics [32,33]. Consequently, analyzing the WQI rating of water quality to determine low pollution levels and ion compositions consistent with natural weathering patterns allows for the exclusion of anthropogenic interference or other factors influencing lake-forming substances. This holds significant importance for understanding the control mechanisms of the geological drivers and natural processes on watershed water [34].

Based on existing water sample monitoring data, a total of 21 water samples were collected from two water sources: the Xiangqu River section and the terminal water lake of Nie’er Co. The water quality index (WQI) was calculated according to the WHO’s drinking water standards and Chinese drinking water standard values (Figure 3). The weights assigned reflect the actual deviation of each indicator, with TDS and Cl− being the primary weighting factors for salt lake water quality [35]. The following seven parameters were assigned weights for comprehensive water quality assessment: TDS (0.20), pH (0.15), Cl− (0.18), SO42− (0.15), Na+ (0.12), Ca2+ (0.10), and Mg2+ (0.10) [36]. The WQI scoring criteria are 80–100 points (excellent), 60–79 points (good), 40–59 points (moderate), 20–39 points (poor), and 0–19 points (very poor) [34].

where wi: weight of the i indicator; qi: quality score of the i indicator; n: number of indicators involved in the evaluation (n = 7); ci: concentration in the i sample; and si: limit of the i parameter [32].

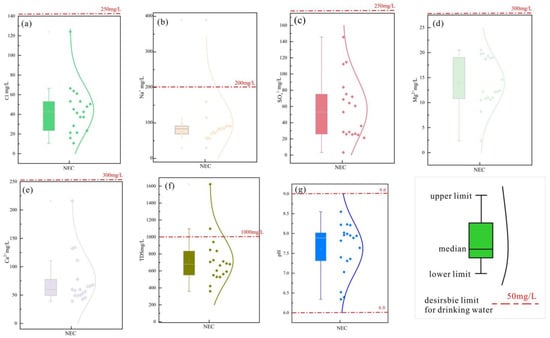

Figure 3.

Distribution of physicochemical parameters of sampled waters in study area. (a) The distribution of Cl− content in water and the corresponding values in WTO drinking water standards; (b) The distribution of Na content in water and the corresponding values in WTO drinking water standards; (c) The distribution of SO42− content in water and the corresponding values in WTO drinking water standards; (d) The distribution of Mg2+ content in water and the corresponding values in WTO drinking water standards; (e) The distribution of Ca2+ content in water and the corresponding values in WTO drinking water standards; (f) The distribution of TDS in water and the corresponding values in WTO drinking water standards; (g) The distribution of pH in water and the corresponding values in WTO drinking water standards.

The above chart presents graphical analyses of seven indicator parameters against WHO drinking water standards (Table 3). Due to the exceptionally high salinity and ion concentrations in the Terminal Lake NEC16-17 samples—both exceeding standard values—only data from other water samples are displayed. Among these, merely two samples exhibited partial values surpassing drinking water standards. Based on the aforementioned calculation formula, the table below presents the final WQI values for all 21 data samples. The results indicate that the two Nie’er Co Salt Lake samples (NEC16-17) exhibit extremely poor quality due to their exceptionally high salinity. The remaining 19 water samples from the Xiangqu River section demonstrate overall excellent quality, with 17 rated as “Excellent” and only NEC05 and NEC15 rated as “Good” due to their spring water origin and relatively higher ion concentrations. The majority of surface water samples from rivers within the study area met WHO drinking water standards for ion concentrations. Given the region’s sparse population and minimal human activity, the water remains free from external anthropogenic contamination. Consequently, they exhibit stable natural conditions and represent naturally occurring sources of substances [32].

Table 3.

WQI calculation data results.

4.1.2. Correlation Between Rivers and Physicochemical Parameters of Water Samples

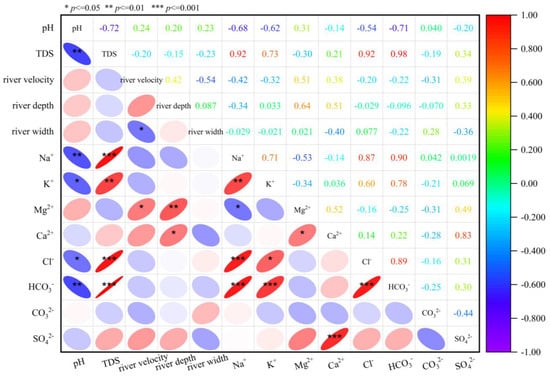

This diagram illustrates the correlation between river width, depth, flow velocity, TDS, pH, and the elemental content of water samples (Figure 4) [26]. Darker colors indicate stronger correlations, with blue signifying negative correlations and red denoting positive correlations. Numerical values represent the degree of statistical significance. TDS exhibits a strong positive correlation with sodium, calcium, potassium, and chloride ions, with values exceeding 0.8, indicating these elements are primary determinants of TDS levels. pH shows a significant negative correlation with chloride and sodium ions, suggesting the water’s acidity or alkalinity influences ion concentrations. Conversely, the river’s hydrological parameters—flow velocity, depth, and width—showed no significant correlation with most ions [37,38]. Only river depth exhibited a significant positive correlation with calcium ions, while flow velocity showed a significant negative correlation with TDS. This indicates that kinetic parameters exert a minimal influence on river ion concentrations, with ionic variations primarily driven by hydrochemical reactions, such as rock weathering, dissolution, and leaching. Significant correlations exist between ions, including sodium with potassium and chloride, and chloride with calcium and potassium, with r > 0.7 indicating a companion relationship. Carbonate and sulphate ions, along with sodium and magnesium, show significant negative correlations, suggesting chemical reactions, such as dissolution–exchange and precipitation between ions and water-soluble mineral salts.

Figure 4.

Correlation of ion concentration in water.

4.1.3. Distribution Characteristics of Hydrochemical Types

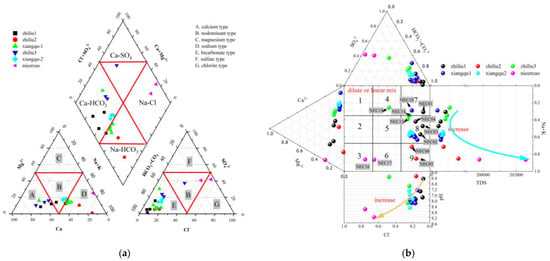

The Piper diagram can comprehensively reflect the hydrochemical characteristics through the proportional relationship of the main ions, and to a certain extent, it has the function of indicating the evolution process of water chemistry. The rhombus area is divided into nine zones, indicating nine hydrochemical types [39], which can better indicate the formation and evolution of river water and groundwater, and indirectly indicate the hydrological cycle. Nie’er Co Salt Lake is a terminal lake. It has a long river length and many branches. There are three branches in different directions. The water samples of the source, the branch river, and the final terminal lake are all exposed to travertine at the source, and all of them are hot springs. The stages of development and evolution of each source are inconsistent, and the solid and water samples presented are also different. It can be seen from the Piper diagram [40] that the farthest, tributary 1, from the terminal lake is a Ca-HCO3−-type, the tributary 2 is an Na-HCO3−-type, and the closer recharge tributary 3 is a Ca-HCO3—type. But, compared with tributary 1, bicarbonate is reduced and transits to a sulfate type, and cations are also enriched in calcium ions. The water sample data of each tributary into the Xiangqu River Basin were analyzed. The cation showed a gradual decrease in calcium ions, a decrease in anionic carbonates, and an increase in sulfate ions (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Runoff and the water chemical characteristics of the terminal-end lake. (a) Piper; (b) Durov; The arrows in the picture indicate the sequence from the hot spring, surface river water to the teminal lake water.

The Durov diagram (Figure 5b) analysis showed that pH and TDS maintained the same law in the runoff of tributaries’ spring water and groundwater → Xiangqu → Nie’er Co, and the sources of the three tributaries were all high. Dilution in the runoff of tributaries led to an increase in pH and a decrease in TDS, which increased again after entering the Xiangqu reach and remained stable during the runoff process of Xiangqu, proving that there was an external source input. After receiving the recharge of groundwater, hot springs, surface runoff, and precipitation, the lake water was strongly evaporated and concentrated, resulting in the precipitation of calcium carbonate and magnesium carbonate with low solubility, while Na+, SO42−, and Cl− with relatively high solubility gradually became the main chemical components in the terminal salt lake. The corresponding TDS increased continuously, and the water type gradually transitioned to a sulfate type (Table 4).

Table 4.

Calculation of water chemical types of water samples [41].

4.2. Source of Materials and Quantitative Contribution Rate

4.2.1. Qualitative Analysis of Principal Elements

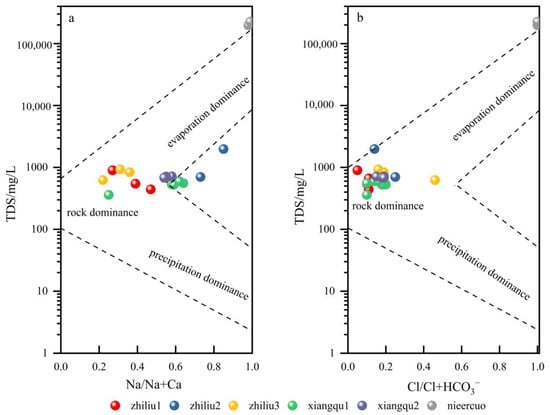

The hydrochemical composition of natural water bodies has a variety of origins, which are closely related to the various hydrogeochemical processes they undergo. Through the study of global natural water bodies, Gibbs summarized it into three causes: atmospheric precipitation, lithology, and evaporation–crystallization. A Gibbs diagram can indicate the main factors controlling the chemical composition of natural water bodies.

The Gibbs diagram is used to intuitively reflect that the main ion components of the water body are controlled by atmospheric precipitation, rock weathering, and evaporative crystallization (Figure 6). The TDS < 10 mg/L in the atmospheric precipitation area, and the cations or anions are between 0.5 and 1. The water sample ions in this area are mainly controlled by atmospheric precipitation. The TDS value of the rock weathering area is 70~300 mg/L, and the cation or anion is less than 0.5. The water sample ions in this area are mainly controlled by rock weathering. The TDS in the evaporation–crystallization zone is greater than 300 mg/L, and the cation or anion ratio is 0.5–1. The water sample ions in this area are mainly controlled by evaporation–crystallization [42].

Figure 6.

Gibbs diagram of water. (a) TDS and Na/Na+Ca; (b) TDS and Cl/Cl+HCO3–.

The source spring water is greatly affected by rock weathering, and the Xiangqu River water is located in the evaporative crystallization area. The cation of spring water mainly comes from rock weathering, while the cation of river water gradually develops from rock weathering to the evaporation–crystallization process. The source and dominant control process of anions in spring water and river water are different from cations, which are the source of rock weathering. The water of Nie’er Co Lake in the terminal salt lake is a multi-component mixed water source, including atmospheric precipitation supply, weathering and dissolution of surrounding rocks, evaporation, and crystallization. The hydrochemical genesis of river water is inconsistent, which is located between the lithology control area and evaporation–crystallization. The water genesis of lake water is consistent, mainly related to evaporation–crystallization.

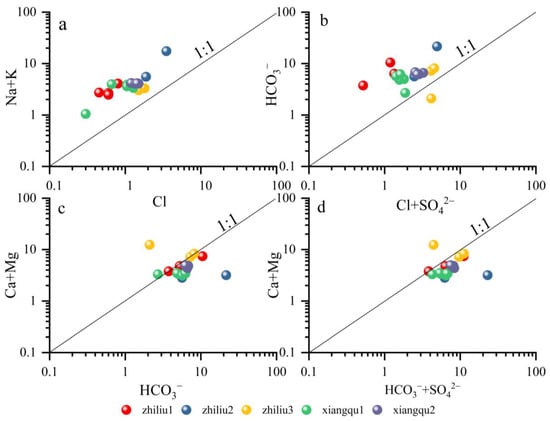

The ratio of Na + K/Cl is greater than one (Figure 7a), indicating that it is mainly derived from the weathering of silicate rocks or water–rock interaction. In this process, a large amount of Na+ and K are released, resulting in an increase in the concentration of Na+ and K+, while the concentration of Cl− is relatively stable or increases less. Generally, Ca2+, Mg2+, HCO3−. and SO42− in groundwater are mainly derived from the dissolution of carbonates or silicates and evaporites (such as sulfates) (Figure 7b). The HCO3−/Cl + SO42− relationship diagram shows that all the points fall above the 1:1 straight line, indicating that the formation of the water body is mainly the dissolution of carbonates. Only one point of tributary 3 is located below 1:1, indicating that the water type is accompanied by the dissolution of evaporite (Figure 7c) [43].

Figure 7.

Main ion ratio diagram of water. (a) Na+K and Cl; (b) HCO3– and Cl+SO42–; (c) Ca+Mg and HCO3–; (d) Ca+Mg and HCO3–+SO42–.

Combined with the analysis of the ratio of Ca + Mg/HCO3− and the ratio of Ca + Mg/HCO3− + SO42−, the points are close to or lower than one, which are located on the line (Figure 7d). The hydrochemical composition is mainly dissolved by the mixture of carbonate rock–CaCO3, CaMg(CO3)2, and gypsum CaSO4. The tributary 3 located above the line indicates that there are additional sources of cations, which may include the dissolution of gypsum CaSO4, silicate weathering, and cation exchange of clay mineral adsorption. The tributary 2, located below the line, indicates that Ca2+ and Mg2+ in groundwater are mainly derived from the dissolution of carbonate rocks, and there are also the effects of weathering and dissolution of silicate rocks and evaporite rocks.

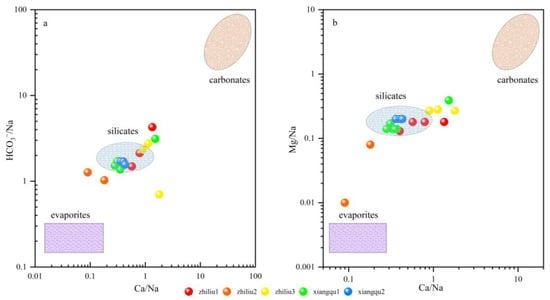

The contribution of silicate, carbonate, and evaporite can be determined by the ratio of Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, and HCO3− [44]. As shown in the figure, most of the river water and tributary groundwater samples are located near the silicate, indicating that the water chemical composition of Na+, Mg2+, and HCO3− released by silicate weathering is dominant. A tributary water sample is located in the transition zone between silicate and carbonate (Figure 8), indicating that carbonate weathering also controls the chemical composition of water. In Figure 8b, some groundwater deviates from silicate and is close to evaporite, indicating that evaporite weathering is also the cause of hydrochemical composition. The chemical composition of river water (Xiangqu1-2) along the surface runoff is mainly controlled by silicate weathering, and carbonate weathering also has an impact on it. The chemical composition of groundwater in tributaries is determined by silicate, evaporite, and carbonate weathering. This matches the contribution of rock weathering calculated in Figure 6.

Figure 8.

Mixing diagrams using Na-normalized molar ratios in the dissolved phase of the rivers. (a) HCO3–/Na and Ca/Na; (b) Mg/Na and Ca/Na.

The relationship between Ca2+/Na+ and HCO3−/Na+ can reveal the influence of different sources (evaporite, silicate rock, precipitation, and carbonate rock) in the process of groundwater circulation [45]. In this figure, the distribution of tributaries is scattered, located in the evaporite–silicate transition zone and silicate–carbonate transition zone, mainly for the interaction between silicate and carbonate rocks. The Xiangqu section is mainly affected by silicate rock.

This combination of ion ratios indicates that the chemical composition of the samples is the result of a combination of multiple geological processes, including weathering and dissolution of carbonate and silicate rocks, and dissolution of evaporite rocks. These processes together contribute to the ion composition of the Xiangqu River and form complex water–rock interactions [46].

4.2.2. Deep-Water Flow, Tributary Contribution Rate

Multiple faults that developed within the Xiangqu River basin provide crucial pathways for deep fluid ascent. Source water samples from NEC05 and NEC15 exhibit temperatures of 35–40 °C, exceeding surface water temperatures, with mineralization significantly higher than that of the surface waters in the Xiangqu basin (Figure 2c,f). Cations are predominantly Ca2+, Mg2+, and Na+, while anions are chiefly HCO3−. Calcareous travertine deposits are distributed around these springs. Deep fluids ascend along faults, undergoing hydrothermal alteration that saturates the fluids with Ca2+ and HCO3−. Upon reaching the surface, rapid pressure reduction causes CO2 to escape, leading to the rapid precipitation of CaCO3 and travertine formation. Consequently, the headwaters of Xiangqu’s tributaries all originate from deep fluids escaping to the surface, thereby supplying elemental material to the rivers [47].

According to the mass balance equation, the contribution of each tributary to the main river channel is calculated, and the equations are constructed. Because sodium ions and chloride ions are relatively stable in the whole river section, precipitation and adsorption will not occur, so sodium and chlorine are selected for the linear equation to obtain the contribution rate:

Among them are the C main river channel—the concentration of a certain element in the main river channel (measured value); C tributary i—the concentration of this element in tributary i (measured value); and the contribution rate of fi-tributary i (the total contribution rate is 100%).

Finally, the contribution rate of each tributary to the main river channel is calculated as follows: tributary 1—39.56%, tributary 2—8.18%, tributary 3—52.26% [37,38].

4.2.3. Minor Element Analysis

Rare earth elements are widely used in the study of sediment provenance discrimination and tectonic environment change due to their similar chemical element composition and stable chemical properties. The morphological characteristics of the spider diagram of rare earth elements are of great significance to the source identification of sediments [48].

The trace element concentrations of volcanic rocks and river sediments around the Xiangqu Basin were standardized by chondrites (Figure 9), and the rare earth element distribution map and trace element spider diagram were made [49]. The overall characteristics of the chondrite–normalized rare earth element distribution model are the relative enrichment of LREE, the relative loss of HREE, and the obvious loss of Eu. The trace element spider diagram shows the geochemical characteristics of strong enrichment of large ion incompatible elements such as Th, U, and Ce, and strong depletion of high field strength elements such as Ti, Nb, and Ta. Light rare earth elements are relatively enriched in the mineral phase of early crystallization and are easily adsorbed by clay minerals during weathering and transportation [27]. Their migration ability in water is relatively weak, and they are deposited in the near-source area. The REE distribution pattern and trace element spider diagram of river sediments are highly consistent with the surrounding volcanic rocks, reflecting that the sediments inherit the geochemical characteristics of volcanic rocks, revealing that magmatic differentiation and supergene leaching synergistically control the migration–enrichment path of elements. Therefore, it can be determined that the elements of river sediments are mainly derived from the weathering and denudation of volcanic rocks.

Figure 9.

Elemental content chart. (a) Trace element spider diagram—river sediments; (b) rare earth element distribution diagram—river sediments; (c) trace element spider diagram—volcanic rocks; (d) rare earth element distribution diagram—volcanic rocks.

4.2.4. Contribution Rate of Surrounding Rock Weathering

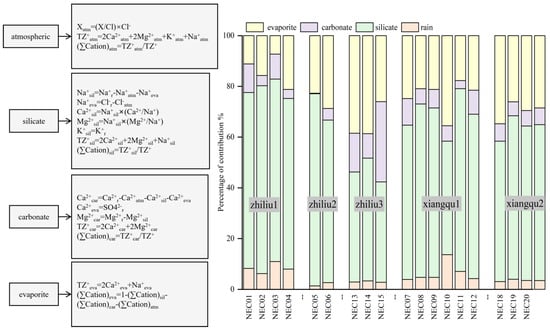

The analysis of the forward model data shows that different rock weathering types in the Xiangqu basin have a significant effect on the water solute. Even in the same basin, the change of rock type directly determines the hydrochemical components of river water and spring water. Therefore, it is particularly important to quantitatively study the water’s rock weathering in the basin, and then determine the contribution ratio of dissolved substances from different sources in the water body [42,50]. According to the calculation of the contribution of carbonate minerals (Figure 10), silicate minerals, and evaporite weathering process to river ions, it is concluded that the weathering ratio of the main ions in the water body of the study area from silicate minerals is between 43% and 74%; the proportion of evaporite minerals is between 11% and 38%. The weathering ratio from carbonate minerals is between 3% and 31%. The proportion of atmospheric precipitation and rainwater is between 1% and 13%. It can be seen that the main ions in the river water of the study area are derived from silicate minerals, followed by the weathering of evaporite and carbonate minerals. The contribution ratio of silicate mineral weathering from upstream to downstream gradually decreases, and the contribution ratio of evaporite and carbonate mineral weathering gradually increases.

Figure 10.

Contribution rate of rock weathering to major elements in water [25,51].

4.3. Water–Rock Interaction

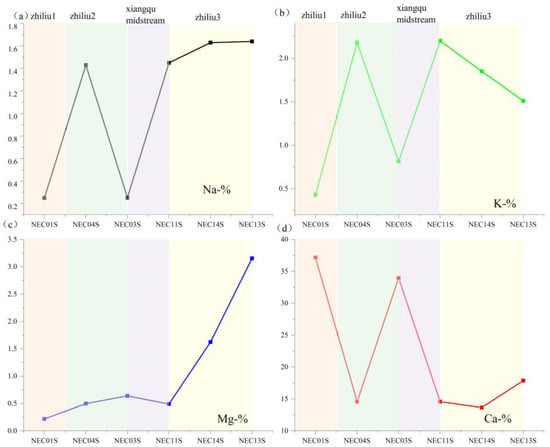

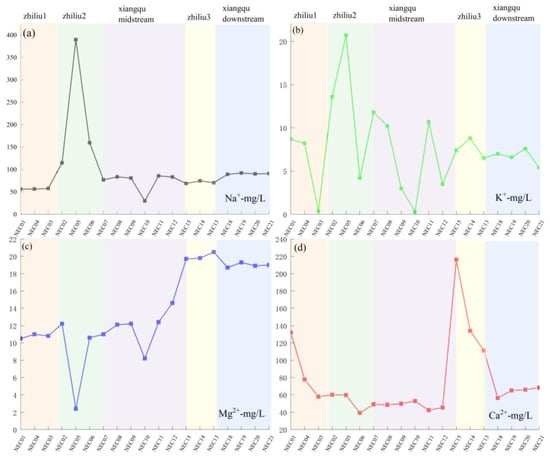

4.3.1. Spatial Variation of Main Ion Components

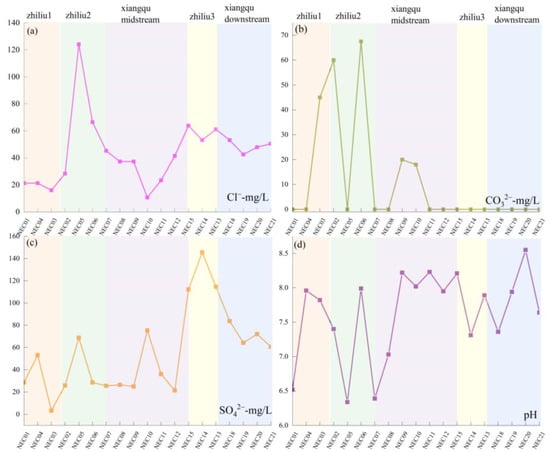

Sodium and potassium primarily dissolve into the water body through leaching from silicate minerals, whereas calcium and magnesium dissolution is dominated by carbonate minerals. The spatial distribution of elemental concentrations in sediments exhibits a synchronous increasing trend with corresponding water samples from the same river section. Across different tributary sections, all cations demonstrate a consistent pattern of ‘increased sediment content → synchronous increase in water sample concentration’, confirming sediment replenishment of cations in water samples. For sediment sodium and potassium concentrations, it is tributary 2 > Xiangqu > tributary 1 > tributary 3 (Figure 11a,b). The water samples exhibit the same trend (Figure 12a,b). Sediment calcium and magnesium concentrations are tributary 1 > tributary 2 > tributary 3 (Figure 11c,d). The water sample calcium and magnesium concentrations also show corresponding increases across different sections (Figure 12c,d). Spatial variation in water sample carbonate ions inversely correlates with sediment calcium–magnesium content and positively correlates with water sample calcium–magnesium content [52]. This indicates that carbonate mineral dissolution releases calcium, magnesium, and carbonate ions into the water body, correspondingly reducing their concentrations in sediments. Sulfate and chloride ion concentrations in water samples increase downstream, consistent with sediment enrichment patterns, reflecting dual influences of evaporative concentration and sediment release (Figure 13a–c). pH variations influence water–rock interactions (Figure 13d): weakly acidic conditions reduce carbonate mineral dissolution rates, whereas alkaline environments enhance dissolution of both carbonate and silicate minerals. In the higher-pH tributary 1–2 water bodies, elevated element concentrations in water samples indicate greater mineral dissolution, releasing ions into the water and accelerating sediment replenishment of water sample constituents.

Figure 11.

The space change of each element content with the concentration of surface–salt lake runoff. (a) Na content in river sediments; (b) K content in river sediments; (c) Mg content in river sediments; (d) Ca content in river sediments.

Figure 12.

The space change of each element content with the concentration of surface–salt lake runoff. (a) Na content in river water samples; (b) K content in river water samples; (c) Mg content in river water samples; (d) Ca content in river water samples.

Figure 13.

The space change of each element content with the concentration of surface–salt lake runoff. (a) Cl− content in river water samples; (b) CO32− content in river water samples; (c) SO42− content in river water samples; (d) pH spatial distribution.

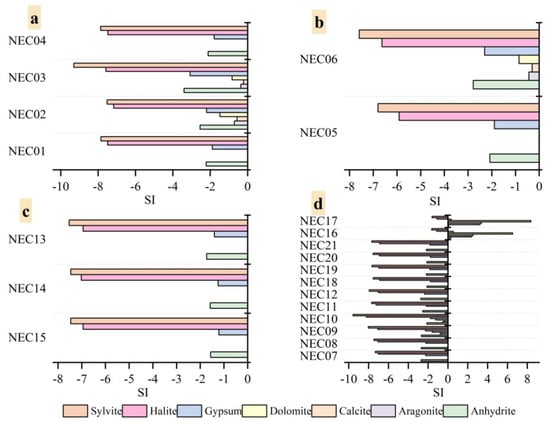

4.3.2. SI Saturation Index of Water Minerals

The tributaries’ spring water and Xiangqu basin water are in the mineral-dissolved state, SI < 0. Gypsum, travertine, calcite, and dolomite minerals are saturated and precipitated in the terminus of the Nie’er Co Salt Lake, and halite and sylvite are unsaturated (Figure 14). The mineral SI of the recharge water and the source water of each tributary is shown as carbonate > sulfate > chloride, and the saturation index values of each mineral are relatively consistent, indicating that the spring water and river water have a consistent source [53]. At the same time, the SI values of spring water, river water, and lake water minerals show a gradual increase trend according to the distance from the terminal salt lake. Finally, gypsum, calcite, and dolomite change from negative to positive in the salt lake brine, and halite and sylvite are also close to zero, indicating that, with the process of evaporation and karst filtration, the corresponding minerals are precipitated, resulting in the gradual change of hydrochemical types. It can also be seen from the saturation index that the saturation index of calcite, gypsum, and halite in the lake water is higher than that of the recharge water, which further proves that evaporation causes the continuous concentration of these minerals [50].

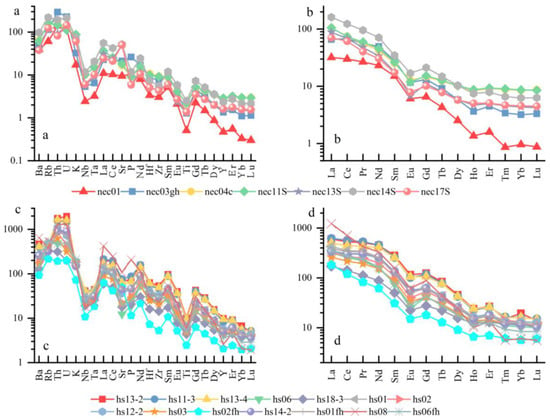

Figure 14.

The variation characteristics of saturation index of different minerals in water. (a) zhiliu1; (b) zhiliu2; (c) zhiliu3; (d) xiangqu channel thread.

4.4. Comparative Analysis of the Evolutionary Mechanisms of Lake Nie’er Co and Global Terminal Lake Evolution

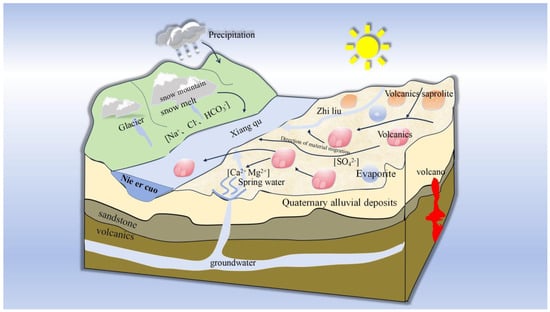

4.4.1. Formation Mechanism of Nie’er Co Lake

As a terminal lake within the Bangong Co–Nujiang Suture Zone, the hydrochemical characteristics of Nie’er Co Lake are jointly controlled by tectonics, deep fluids, surface runoff, volcanic rock weathering, and climatic evaporation. Tectonic activity south of the study area gave rise to extensive Neogene volcanic rocks, which serve as a primary source of mineralizing elements. At the headwaters of the Xiangqu Tributary, Ca-HCO3−-type hot springs have developed, transporting mineralizing elements derived from deep fluids. The surface runoff of the Xiangqu watershed is predominantly replenished by atmospheric precipitation and glacial meltwater (Ca-HCO3− type), which leaches soluble elements from surrounding volcanic rocks and carries them into the terminal lake via rivers. Along the river course, variations in lithology lead to a differential input of elements at different sections, followed by water–rock interactions that drive processes such as aqueous element enrichment and sedimentary precipitation. Ultimately, under arid climatic conditions, intense evaporation concentrates the lake water, leading to the formation of the Na-SO42−-type Nie’er Co Salt Lake [19,21] (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Pattern of water body formation process of Nie’er Co terminal salt lake.

4.4.2. Comparative Analysis of Formation Mechanisms Between Nie’er Co Lake and Typical Terminal Salt Lakes Worldwide

Formation mechanisms of typical terminal salt lakes: The Great Salt Lake is fed by Na-SO42−-type river water and Ca-Cl- type hydrothermal spring water; intense evaporation and concentration of these inflows yield highly saline chloride-type brines [8,9]. Lake Eyre receives seasonal fluvial recharge, with its salinity decreasing during flood periods and dry salt flats forming in arid phases, classifying it as a Na-CO32−-type system [11]. Lake Turkana, situated in the East African Rift Valley, is an alkaline salt lake sustained by permanent rivers. These rivers transport weathering products of surrounding volcanic rocks and tuffs into the lake, where arid conditions and evaporation drive the formation of Na-HCO3−-type brines [13,14]. Qarhan Salt Lake lies in the Dabuxun Depression, Southeastern Qaidam Basin. It is replenished by Ca-Cl-type deep fault fluids and Ca-HCO3−-type surface river water. As these waters flow through regions underlain by granite, they acquire potassium- and lithium-rich ore-forming elements; subsequent evaporation under arid conditions generates Na-SO42−/Cl−-type brines characteristic of Qarhan Salt Lake [15,16,17].

Summary of influencing factors and research insights into terminal salt lake formation: ① Tectonic activity: All terminal salt lakes are located in tectonically active zones. Nie’er Co Lake and Lake Turkana occur in volcanically active basins, with material inputs derived from volcanic rocks. By contrast, Qarhan Salt Lake is supplied with deep fluids via tectonic fault zones. ② Material sources: Among the two terminal salt lakes on the Tibetan Plateau, Qarhan Salt Lake derives its ore-forming elements from silicate granite in the surrounding basin, producing water bodies enriched in potassium and magnesium. For Nie’er Co Lake, the leaching of volcanic rocks constitutes the primary elemental supply, leading to boron, magnesium, and lithium accumulation. Lake Turkana also receives weathering products of volcanic rocks and tuffs. In contrast, the Great Salt Lake and Lake Eyre rely predominantly on fluvial recharge, with no additional inputs from surrounding rock weathering. ③ Hydrological and climatic conditions: All typical terminal salt lakes are replenished by freshwater rivers and lack external outflow channels, making evaporation the sole pathway of water loss under arid conditions. The key differences lie in the intermittent input of deep fluids into Nie’er Co Lake and Qarhan Salt Lake, which elevates their ionic concentrations above those of other lakes. Lake Eyre is an ephemeral water body, whereas the other lakes experience stable climatic conditions and consistent recharge–evaporation regimes, leading to progressive solute concentration and the sequential hydrochemical evolution from carbonate-type to sulfate-type and finally chloride-type brines.

In conclusion, the formation of Nie’er Co terminal lake is synergistically driven by deep fluid input, fluvial recharge, volcanic rock weathering, and evaporation—a distinctive model that differs from the fluvial recharge–evaporation dominated mechanism of most other terminal lakes. Owing to their high-altitude setting and multi-source material supply, salt lakes on the Tibetan Plateau typically form clusters of terminal lake chains within individual basins, with each lake exhibiting unique characteristics. A comparative analysis with Qarhan Salt Lake confirms that traditional silicate weathering primarily supplies conventional elements (e.g., K, Na, and Mg), whereas tectonically induced volcanic rock inputs give rise to specialized salt lakes enriched in B and Li. The unique attributes of Nie’er Co Salt Lake fill the research gap in the hydrochemical evolution of volcanic rock-associated terminal lakes and enrich the global inventory of salt lake genesis cases. Moreover, by contrasting its formation mechanism with those of typical terminal lakes worldwide, we establish a genetic framework for salt lakes characterized by the coupling of tectonic activity, deep fluid migration, hydrological recharge, water–rock interaction, and evaporative concentration. The variable proportional combination of these processes accounts for the diverse hydrochemical types of salt lakes, providing a reference for deciphering the formation of terminal lakes under different geological and climatic contexts.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Based on WQI findings, it is confirmed that the water quality of the Xiangqu River basin flowing into Nie’er Co Lake is excellent and naturally formed, free from anthropogenic contamination. High-quality water carries salt ions generated by the weathering of the surrounding rock into the enclosed lake. Through prolonged evaporation and accumulation, salinity increases and ion concentrations become enriched, ultimately forming a terminal lake with extremely poor water quality;

- (2)

- Mechanism of hydrochemical evolution:

The source water exhibits an HCO3−–Ca2+/Na+ type, with its principal elements derived from the weathering of carbonate and silicate rocks. Under arid conditions, water evaporation and the mixing of tributaries replenishing the Xiangqu River drive the water body towards evaporative concentration;

- (3)

- Elemental material sources:

Upstream water sources derive their primary ions from silicate mineral weathering, whilst downstream contributions increase from evaporite and carbonate mineral weathering. Both rare earth elements and trace elements in river sediments are confirmed to originate from regional volcanic rocks. Thermal springs transport deep-seated materials, with leaching processes in volcanic rock areas further replenishing the water body with mineralizing elements;

- (4)

- Formation mechanism of Nie’er Co Salt Lake:

Three tributaries transport deep geothermal fluids that mix with surface runoff. After leaching mineral elements through volcanic rock formations, these waters converge into the lake basin. Under arid conditions, intense evaporation promotes the saturation and precipitation of carbonate minerals, ultimately forming the Na+–SO42−/Cl−-type salt lake—Nie’er Co.

Author Contributions

J.H. and M.Z.: Conceptualization, methodology; J.H., Z.N., and M.Z.: formal analysis, data curation; J.H. and K.W.: writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; Z.N. and M.Z.: visualization, supervision; project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Projects (2022YFC2904005); the major research program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China entitled Metallogenic Mechanisms and Regularity of the Lithium Ore Concentration Area in the Zabuye Salt Lake, Tibet (91962219, KG2023); the subject of the China Geological Survey project (No.DD20230037, N2301).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nichols, G. Sedimentary processes, environments and basins. In Fluvial Systems in Desiccating Endorheic Basins; Nichols, G., Williams, E., Paola, C., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, G. Tectonics of sedimentary basins. In Endorheic Basins; Busby, C., Azor, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquerro, L.; Liesa, C.L.; Simón, J.; Luzón, A. Sequence stratigraphy in continental endorheic basins: New contributions from the case of the northern extensional teruel basin. Sediment. Geol. 2025, 481, 106868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, A.; Dąbek-Głowacka, J.; Nowak, G.J.; Górecka-Nowak, A.; Wyrwalska, U.; Furca, M.; Wójcik-Tabol, P. Evolution of a late carboniferous fluvio-lacustrine system in an endorheic basin: Multiproxy insights from the Ludwikowice formation, intra-sudetic basin (SW Poland, NE Bohemian Massif). Minerals 2025, 15, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koycegiz, C. Seasonality effect on trend and long-term persistence in precipitation and temperature time series of a semi-arid, endorheic basin in central Anatolia, Turkey. J. Water Clim. Change 2024, 15, 2402–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvan, F.J.; Heredia, J.; Ruiz, J.M.; Pardo-Iguzquiza, E.; Garcia de Domingo, A.; Elorza, F.J. Hydrochemical and isotopes studies in a hypersaline wetland to define the hydrogeological conceptual model: Fuente de piedra lake (Malaga, Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 576, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Naftz, D.; Spencer, R.; Oviatt, C. Geochemical evolution of great Salt Lake, Utah, USA. Aquat. Geochem. 2008, 15, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagniecki, E.; Vanden Berg, M.; Boyd, E.; Johnston, D.; Baxter, B. Sulfate-rich spring seeps and seasonal formation of terraced, crystalline mirabilite mounds along the shores of Great Salt Lake, Utah: Hydrologic and chemical expression during declining lake elevation. Chem. Geol. 2023, 636, 121650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorko, K.; Jewell, P.; Nicoll, K. Fluvial response to an historic lowstand of the great Salt Lake, Utah. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2011, 37, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, T.; Arnold, L.; Gázquez, F.; May, J.; Marx, S.; Jankowski, N.; Chivas, A.; Garćia, A.; Cadd, H.; Parker, A.; et al. Late quaternary climate change in Australia’s arid interior: Evidence from Kati Thanda—Lake Eyre. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2022, 292, 107635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppel, M.; Karlstrom, K.; Crossey, L.; Love, A.; Priestley, S. Evidence for intra-plate seismicity from spring-carbonate mound springs in the Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre region, south australia: Implications for groundwater discharge from the great artesian basin. Hydrogeol. J. 2019, 28, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obiero, K.; Wakjira, M.; Gownaris, N.; Malala, J.; Keyombe, J.; Ajode, M.; Smith, S.; Lawrence, T.; Ogello, E.; Getahun, A.; et al. Lake Turkana: Status, challenges, and opportunities for collaborative research. J. Great Lakes Res. 2023, 49, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutz, A.; Schuster, M.; Boës, X.; Rubino, J. Orbitally-driven evolution of Lake Turkana (Turkana Depression, Kenya, Ears) between 1.95 and 1.72 ma: A sequence stratigraphy perspective. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2017, 125, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloszies, C.; Forman, S.L.; Wright, D.K. Water level history for Lake Turkana, Kenya in the past 15,000 years and a variable transition from the African humid period to holocene aridity. Glob. Planet. Change 2015, 132, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.L.; Fan, Q.S.; Li, Q.K.; Chen, T.Y.; Yang, H.T.; Han, C.M. Recharge processes limit the resource elements of Qarhan Salt Lake in western China and analogues in the evaporite basins. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2023, 41, 1226–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bao, G. Diversity of prokaryotic microorganisms in alkaline saline soil of the Qarhan Salt Lake area in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.W. Uniconfined brine hydrochemistry characteristic and brine cause analysis of east section of Qarhan Salt Lake. J. Salt Lake Res. 2009, 17, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, M.P. Salt lake resources and eco-environment in China. Acta Geol. Sin. 2010, 84, 1613–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.F.; Zheng, M.P. Geological features and metallogenic mechanism of the Nie’er co magnesium borate deposit,Tibet. Acta Geol. Sin. 2010, 84, 1601–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xu, Z.Y.; Yan, W.B.; Hao, Y.J.; Lin, Z.X. Zircon u-pb ages and geochemical characteristics of diabase in Nie’erco area, Central Tibet: Implication for Neo-Tethyan slab breakoff. Geol. China 2023, 50, 1804–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.Y.; Zheng, M.P.; Nie, Z.; Lv, Y.Y.; Wu, Q. Mg-borate deposit formation: Recharge and lake water hydrogeochemistry of Nie’ er co Lake, northwestern Tibet. Geochem. J. 2016, 50, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 14506.28-2010; Methods for Chemical Analysis of Silicate Rocks—Part 28: Determination of 16 Major and Minor Elements Content. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China, Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2010. Available online: https://openstd.samr.gov.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=8C96145A08BB7CE3C1B2E6947DBBB4AA&refer=outter (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- GB/T 14506.30-2010; Methods for Chemical Analysis of Silicate Rocks—Part 30: Determination of 44 Elements. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China, Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2010. Available online: https://openstd.samr.gov.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=C7B39BCCDC84BC81FD9EFD9F6CDD7A16&refer=outter (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- HDB/T 3022-2018; Standard for Primary Trace Element Testing of Rocks. Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology: Beijing, China, 2018; (Internal Institutional Documents, Not Made Public, the Standard Number was Provided by the Testing Party).

- Zhang, X.R.; Fan, Q.S.; Li, Q.K.; Du, Y.S.; Qin, Z.J.; Wei, H.C.; Shan, F.S. The source, distribution, and sedimentary pattern of k-rich brines in the Qaidam Basin, western china. Minerals 2019, 9, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Duan, L.M.; Mao, H.R.; Wang, C.Y.; Liang, X.Y.; Luo, A.K.; Huang, L.; Yu, R.H.; Miao, P.; Zhao, Y.Z. Hydrochemical and isotopic fingerprints of groundwater origin and evolution in the Urangulan River Basin, China’s Loess Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.X.; Gao, Y.Y.; Qian, H.; Chen, J.; Li, W.Q.; Li, S.Q.; Liu, Y.X. Elucidating the hydrochemistry and REE evolution of surface water and groundwater affected by acid mine drainage. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 366, 125495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.D.; Xu, J.X.; Han, W.H.; Han, J.B. Hydrochemical characteristics and influencing factors of lakes in Hoh Xil. Earth Environ. 2024, 53, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, N. Distribution characteristics and source identification of heavy metals and safe utilization in surface soils from high-selenium regions in China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk. Assess. 2024, 38, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Luo, X.; Xu, J.F.; Dong, S.Q.; Liang, S.S.; Xu, L.F.; Liu, L.Z.; Li, Y.H. Effects of PH and hydrochemical types on archaealcommunity structures in salt lakes of Badain Jaran Desert, Inner Mongolia. Microbiol. China 2025, 52, 2517–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.Y. Variation patterns of boron and lithium isotopes in salt lakes on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau and their application in evaluating resourcesin the Damxung Co salt lake. J. Geomech. 2024, 30, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.W.; Zhang, Y.X.; Hao, Q.C.; Chen, H.Z.; Qi, Z.X.; Yan, H.J.; Han, J.B.; et al. Hydrogeochemical signatures, genetic mechanisms, and sustainable utilization potential of Li-B-Sr enriched groundwater in a typical arid endorheic watershed on Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 61, 102731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, A.; Ahmed, T.; Uddin, M.; Al-Sulttani, A.; Shafiquzzaman, M.; Islam, M.; Ahmed, M.; Alamin; Mohadesh, M.; Haque, M.; et al. Evaluation of Water Quality Index (WQI) in and around Dhaka city using groundwater quality parameters. Water 2023, 15, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, N.; Li, L.M.; Zhu, H.X.; Chen, L.; Li, S.P.; Meng, F.W.; Zhang, X.Y. Multiple evaluations, risk assessment, and source identification of heavy metals in surface water and sediment of the Golmud River, northeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 1095731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.S.; Pandya, D.M.; Shah, M. A systematic and comparative study of Water Quality Index (WQI) for groundwater quality analysis and assessment. Environ. Sci Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 54303–54323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.U.; Khan, M.A.; Siddiqui, F.; Mahmood, N.; Salman, N.; Alamgir, A.; Shaukat, S.S. Geospatial assessment of water quality using Principal Components Analysis (PCA) and Water Quality Index (WQI) in Basho Valley, Gilgit Baltistan (northern areas of Pakistan). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.Q.; He, Z.Q.; Diao, Y.S.; Huang, X.; Guo, J.; Hu, F.; Luo, A.P.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Zhang, X.B. Tracing the origins of strontium in strontium-rich mineral water usingstrontium, hydrogen and oxygen isotope analysis. Earth Environ. 2025, 53, 504–515. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/52.1139.p.20241231.1500.001.html (accessed on 31 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.T.; Chen, L.; Li, Q.K.; Wang, J.P.; Yu, D.M.; Liu, Z.; Huo, S.L. Sources and enrichment processes of rubidium and cesium in the Nalengele river and its terminal lakes, Qaidam Basin. J. Salt Lake Res. 2024, 32, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.Z.; Yang, X.P. Hydrochemical compositions of natural waters in ordos deserts and their influencing factors. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 76, 2224–2239. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=X7jC3qydZ5-s2HzJj08EMS1dKjwAYUdMcH6JTCWRim8w5Zf0-MwmUvurVpCtQxg2z9kmD8t3gtjqG1P65IVVsh9wqMQ_zL5wahcDgauXd9dPOcz2VhwQ2OTXBT2DNjP56KgkpvcNnpYSr84oBEjMPOHMynPWIRXIX_xvyfLJ0dPBULh3x8FSmg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Fan, Z.J.; Wei, X.; Zhou, Y.L.; Chen, M.E.; Shen, J.W.; Li, J.W. Analysis of nitrate sources and transformation processes in shallowgroundwater in typical mountainous agricultural area. Res. Environ. Sci. 2023, 36, 1946–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.J.; Chen, C. The classification method of water chemical types based on the principle of kurllov’s formula and shoka lev classification. Ground Water 2018, 40, 6–11. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=1UNTTfPTmO-rASOQuf1e3tOGNBBFXQRBv7XYr10Y4cwq37WMFYNxD9V2R3EqxARjrxmJLzeANvNWb5hUZouZ1ue4DrWTKcXWdnghmcly9lNDofL0uG0oXUl7mImDqRJkNrjcZHPELMXJo2fVVrtslD85Sc45G54OPqcct7_LchjSLH71HtK0Qw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Mercedes-Martin, R.; Ayora, C.; Tritlla, J.; Sanchez-Roman, M. The hydrochemical evolution of alkaline volcanic lakes: A model to understand the South Atlantic pre-salt mineral assemblages. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 198, 102938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.L.; Shen, H.Y.; Zhao, C.H.; Wang, Z.H.; Xie, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, Y.P. Hydrochemical characteristics and formation causes of ground karst water systems in gudui spring catchment. Environ. Sci. 2023, 44, 4874–4883. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=1UNTTfPTmO_baOeHEuc421SPpsjJ5NjR9ydBeB2OoBJEL6atxBNOslNhSU1cW3J52xZTUhhpH2zg6zZ2U6RPSlHI3ufqAbbaLA9ZIkZ2yXXX4_WGWoyPyfpIjscCAOmqGmB_PNkGGKiDA5yOJ-jcDAybW81ibPpX-6Ae0rqXE0c7smHVkT6Dsw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Yang, N.; Guo, L.; Wang, G.C.; Xiong, L.Y.; Song, X.M.; Li, H. Application of major ions and SR isotopes to indicate the evolution of river water and shallow groundwater chemistry in a typical endorheic watershed, northwestern China. Appl. Geochem. 2024, 175, 106182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.L.; Zheng, X.Q.; Liang, Y.P. Hydrochemical characteristics and formation causes of ground karst water systems in the longzici spring catchment. Environ. Sci. 2020, 41, 2087–2095. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=X7jC3qydZ5_mxdxbcWGo6AUSz4SLFixXp0ZDy2AsEz19AKNJA8UJSLCrPiyoyFauk03w2RPF7a-Ilpo8ZFXycNiTSsCHjjkQ8gVUgs3Uwh48J6tyXrj6ZnYNDaVq5vSQRd8sdOhXDHK2wBc1ZtrMB42nO4E7HEvrlyn1KIiasetOhAALwQioXA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Ren, X.H.; Zhang, Z.H.; Yu, R.H.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.Z. Hydrochemical variations and driving mechanisms in a large linked river-irrigation-lake system. Environ. Res. 2023, 225, 115596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.G.; Zheng, M.P.; Zhang, X.F.; Xing, E.Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Ren, J.H.; Ling, Y. O, H, and Sr isotope evidence for origin and mixing processes of the gudui geothermal system, himalayas, China. Geosci. Front. 2020, 11, 1175–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.L.; Miao, W.L.; Zhang, X.Y.; Li, W.W.; Yuan, X.L. Trace element geochemistry and its constrains on lithium provenance of river sediments in the naringgele river catchment of qaidam basin. J. Salt Lake Res. 2023, 31, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.Y.; Zheng, M.P.; Wang, Z.M.; Hao, W.L.; Wang, J.H.; Lin, X.B.; Han, J. Hydrochemical characteristics and sources of brines in the Gasikule salt lake, northwest qaidam basin, China. Geochem. J. 2015, 49, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodbane, M.; Boudoukha, A.; Benaabidate, L. Hydrochemical and statistical characterization of groundwater in the chemora area, northeastern algeria. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 14858–14868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillardet, J.; Dupré, B.; Louvat, P.; Allègre, C.J. Global silicate weathering and CO2 consumption rates deduced from the chemistry of large rivers. Chem. Geol. 1999, 159, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.H.; Pan, T.; He, M.Y.; Hou, D.B.; Chen, J.Z.; Zhou, J.D. Progress in the study of potassium, lithium, and boron salt resourcesin salt lakes of the qaidam basin on the qinghai-tibet plateau. Acta Geosci. Sin. 2025, 46, 376–396. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=X7jC3qydZ5-6TojRWhP7utZWMA8kZk-vTyAl9flAjNesXcLlup5Z4XDmJCPQ4IYjKdbssT3NPPEOQamQ4H1E0LddfHMUo3hH8OUb-hrHIvNOR8uZzf5pYUSd9VRFEFse_PaJ4IvKCjHRfoMiLVKiSKfKOXj0FUuxHkw9s1y796c_LtxFPodt3A==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Amroune, A.; Boudoukha, A.; Boumazbeur, A.; Benaabidate, L.; Guastaldi, E. Groundwater geochemistry and environmental isotopes of the hodna area, southeastern algeria. Desalination Water Treat. 2017, 73, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.