Abstract

Sb-rich avicennite (first discovery in Russia) was found at the Khokhoy gold deposit, 120 km west of Aldan, Aldan district, Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), Eastern Siberia, Russia. The mineral of critical metal thallium forms irregularly shaped grains up to 0.25 mm in size, in association with amgaite, weissbergite, goethite, gold, and unidentified Tl-bearing phases. Aggregates of colloform structure prevail, represented by rhythmic-, concentric-zonal, kidney-shaped, and spherulitic varieties. Avicennite is black in color, with metallic luster, and it fractures unevenly. No cleavage is observed. The density value of avicennite, obtained using its empirical formula and the unit cell parameters calculated from the powder X-ray diffraction data, is 8.548 g/cm3. In reflected light, avicennite is light gray and isotropic. Internal reflections are absent. Reflection is very low; the reflectivity curve is of mixed type with a small maximum in the blue part. Its chemical composition (average value on 10 analyses, wt.%): Tl2O3—85.36, V2O5—0.73, As2O5—0.85, Sb2O5—12.98, Total—99.92; It corresponds to the following empirical formula (calculation for three atoms of O): Tl1.40Sb5+0.30V5+0.03As5+0.03O3. The unit cell parameters calculated from the powder X-ray diffraction data are as follows: the mineral is cubic, a = 10.496(6) Å, V = 1156(2) Å3.

1. Introduction

The further research of the complex and diverse mineralogy of the Khokhoy gold deposit was prompted by the discovery of thallium minerals (weissbergite, avicennite, jankovićite, parapierrotite), which were found in Yakutia for the first time; most importantly, amgaite, a new mineral and the rare natural compound of thallium and tellurium, was also discovered [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In addition, unidentified antimony and thallium carbonates were detected. Thallium minerals are indicators of high-quality gold ores, which is of great importance; they are characteristic of Carlin-type deposits, thus attracting great attention. Carlin-type gold deposits are one of the leaders in global gold production. Carlin-type mineralization is characterized by the presence of thallium in association with arsenic, gold, mercury, antimony, and lead [7]. In some cases, a direct correlation between critical metal thallium and gold is also recorded [8]. The Carlin-type gold deposit, characterized by Au-Tl-As-Hg-Sb geochemical properties, contains high concentrations of Tl in mineralized rocks. In this connection, thallium has been suggested as an effective indicator element than gold in prospecting for gold deposits of this type [9].

Previously, the authors described avicennite from the Khokhoy deposit with a stoichiometric composition without any other impurities [2,3]. In the course of further mineralogical and microprobe studies, thallium oxide with variable antimony contents was found. This mineral is closely associated with avicennite and amgaite and also forms individual grains. At first, it was assumed that these were thallium antimonates. But X-ray examination of the mineral grains showed that it was antimony-containing avicennite—Sb-avicennite.

The article presents original results that enrich our knowledge of the ancient mineral avicennite. The enrichment of the mineral thallium with antimony is another mystery that we have tried to solve in this study.

2. Occurrence, Geological Settings, and Mineral Association

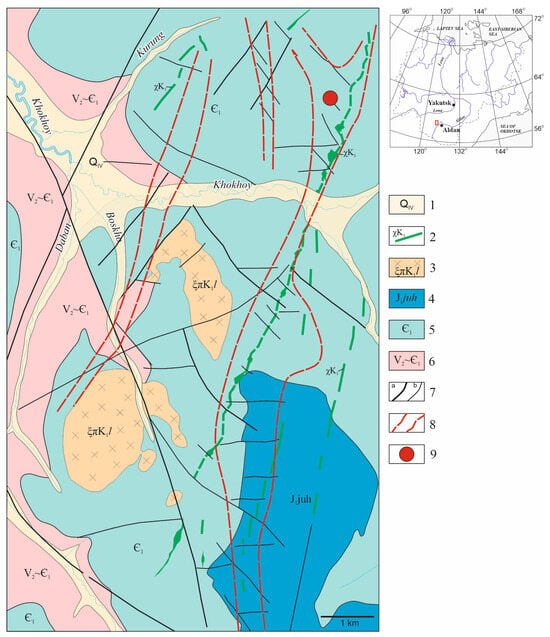

The Khokhoy gold deposit that contains Sb-rich avicennite is located in the Verkhneamginskiy ore district, on the northern slope of the Aldan-Stanovoy Shield at the junction of two large structural units: the Olekma granite-greenstone region and the Aldan granulite-gneiss region, in the zone of the submeridional Amga deep fault (Figure 1) [1]. The mineralization is represented by sandy-clayey-clastic karst formations developed at the tectonically deformed contact between Lower Cambrian carbonate and Lower Jurassic terrigenous deposits. Ore-conducting submeridional steeply deepening fault zones are accompanied by Cretaceous dikes of alkaline gabbroic rocks.

Figure 1.

Geological map of the Khokhoy ore field (Aldan Shield, Yakutia, Russia) [1] with changes: 1—Quaternary deposits; 2—subalkaline dikes; 3—Lebedinsky monzonitesyenite plutonic complex; 4—Yukhtinskaya suite, inequigranular, oligomictic sandstones, lenses and interlayers of gravelstones, conglomerates, siltstones; 5—Lower Cambrian deposits of the Ungelinskaya, Tumuldurskaya, and Pestrotsvetnaya suites, dolomites with interlayers of marl and marly dolomites, 6—Vendian–Lower Cambrian deposits of the Ust-Yudomskaya suite, bituminous dolomites with thin interlayers of marly dolomites; 7—faults: (a) main, (b) secondary; 8—karst development zones; 9—Khokhoy deposit.

Primary ores are represented by pyrite-adularia-quartz metasomatites formed as a result of silicic-potassic metasomatosis of carbonate rocks.

The only macroscopic mineral in the ore minerals of the Khokhoy deposit is pyrite, always altered to goethite or hematite. All other ore minerals form microscopic inclusions in pyrite and vein minerals. These include arsenopyrite, galena, stibnite, chalcopyrite, bornite, sphalerite, berthierite, scheelite, cassiterite, thallium minerals (weissbergite, jankovićite, and parapierrotite), mercury minerals (cinnabar, coloradoite), native gold, and silver. During the oxidation, disintegration, and redeposition processes in karst cavities, loose gold-bearing sediments were formed in primary ores, in which supergene minerals developed extensively: jarosite, avicennite, amgaite, smithsonite, chlorargyrite, and bismoclite.

The described Sb-rich avicennite was found in strongly limonitized clayey-sandy formations containing numerous fragments of primary ores and host rocks that fill karst cavities. Loose supergene formations are composed of quartz, muscovite, clay minerals (illite, clinochlore, chamosite, kaolinite), lepidocrocite, carbonates, baryte, fluorite, goethite, jarosite, and hematite. Primary ores are preserved in the form of fragments/relics of jasperoids—pyrite-adularia-quartz metasomatites resulting from silicic-potassic metasomatosis of carbonate rocks. Jasperoids host low-temperature mineralization represented by fine crypto-grained quartz, chalcedony, adularia, sericite, calcite, baryte, fluorite, illite, hollandite, pyrite, and minerals of thallium, antimony, arsenic, tellurium, and mercury [10]. Finely dispersed native gold from primary ores, not exceeding 5 µm in size, is found in oxidized pyrite enriched with Sb, As, and Hg. In loose karst formations, residual gold was released and grew to 100–500 µm in size. High-grade supergene gold is characterized by a spongy structure and impurities of Ag and Hg. A new mineral, Tl2TeO6 thallium tellurate, amgaite, has been discovered in the ores [5,6].

3. Materials and Methods

Avicennite has been described based on observations obtained under stereo microscope Zeiss Discovery V8 and polarizing microscopes MT 9430L (MeijiTechno, Japan) and A15.1019-B Opto-Edu (Beijing Co., Ltd., China) in the Diamond and Precious Metal Geology Institute, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences (DPMGI SB RAS, Yakutsk, Russia).

Optical properties of avicennite were examined in reflected light under polarization microscopes POLAR-3 (Micromed, Russia) and POLAM-215 (POLAM, Belarus). The reflectance spectrum was determined in air in accordance with the Si standard on a microscope-spectrophotometer MSF-R manufactured by LOMO PLC, Russia (300 µm diameter of the photometric aperture, 100 µm monochromator exit slit size, 6 nm spectral interval).

In order to check the chemical composition of avicennite, its grains were put in epoxy resin, carefully polished, and carbon-coated using Leica EM ACE600 coater (Germany). The chemical composition was studied using scanning electron microscope (SEM) JEOL JSM-6480 LV with an energy dispersive accessory INCA Energy-350 Oxford Instruments and Hitachi FlexSEM 1000 with EMF-detector Xplore Contact 30 and analysis system Oxford AZtecLive STD, accelerating voltage 20 kV, probe diameter 2 μm, current 5 nA on the standard-metallic cobalt. Detected elements, analytical X-ray lines and standards: TlMα—TlInSe2; VKα—vanadinite (Morocco); AsLα—GaAs; SbLα—Sb. The concentrations of other elements with atomic numbers higher than those of beryllium were below the detection limits of EDS analysis.

Several grains of avicennite were mounted on a glass fiber for powder X-ray diffraction with studs, which were carried out using a single-crystal Rigaku R-AXIS Rapid II diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan) equipped with a cylindrical detector of reflected X-rays Image Plate (radius 127.4 mm) in Debye-Scherrer geometry, using CoKα radiation (rotating anode with VariMAX microfocus optics; 40 kV, 15 mA) and 10 min exposure in 2θ range of 3–140°. The angular resolution of the detector is 0.045 2θ (pixel size 100 µm). The data from the X-ray experiment were indexed in the Osc2Tab software [11].

4. Results

- Physical and optical properties

Avicennite forms irregularly shaped grains up to 250 µm in association with amgaite, weissbergite, goethite, gold, and unidentified Tl-bearing phases. Avicennite is black in color, with metallic luster and uneven fracture. No cleavage is observed. The density of the mineral could not be determined, as it significantly exceeds the density of the Clerici solution. The density value of avicennite obtained on the basis of its empirical formula and the unit cell parameters calculated from the powder X-ray diffraction data is 8.548 g/cm3.

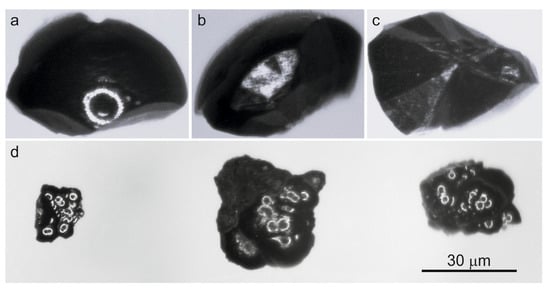

Aggregates of colloform texture prevail (Figure 2). A transition of sectorial crystals to spherical shapes is observed (Figure 2a–c). Colloform shapes and spherulitic aggregates are common (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Morphology of supergene thallium minerals: (a–c)―transition of sectorial crystals to sphere: (a)―spherical form (top view), (b)―combination of two types (side view), (c)―sectorial crystals (bottom view), (d)―colloform shapes.

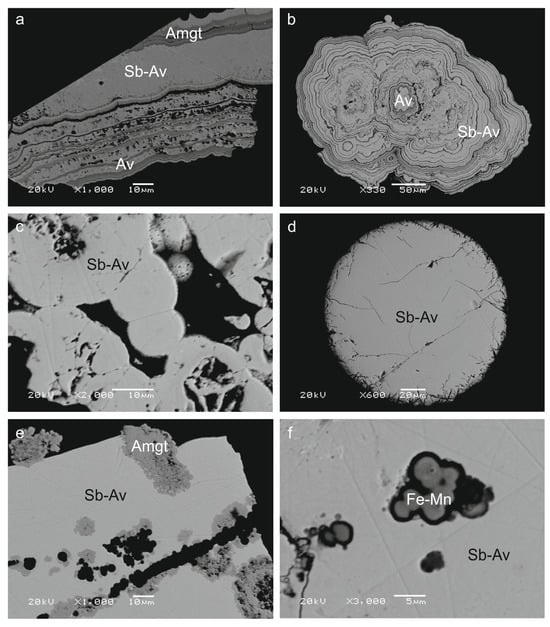

The colloform structures are well shown upon examination of the samples in reflected light and in SEM (Figure 3). They are represented by the following varieties: rhythmic-zonal, showing alternation of avicennite, Sb-rich avicennite, and amgaite (Figure 3a), concentric-zonal (Figure 3b), kidney-shaped and spherulitic (Figure 3c,d). The replacement of avicennite of a massive structure by amgaite of a porous texture is also observed (Figure 3e). Occasionally, concentric zonal aggregates of Mn-Fe variety of amgaite are observed in Sb-rich avicennite (Figure 3f). Some aggregates of Sb-rich avicennite contain native gold inclusions (Figure 3g,h).

Figure 3.

Colloform and kidney-shaped structure of colloidal aggregates of thallium minerals: (a)―rhythmic-zonal, (b)―concentric-zonal, (c)―kidney-shaped, spherulitic aggregates of Sb-rich avicennite (Sb-Av) are recorded in cavities, (d)―spherulitic, (e)―replacement of massive Sb-avicennite by amgaite (Amgt) of a porous structure, (f)―Sb-rich avicennite of a massive structure with inclusions of spherulites of Fe-, Mn-bearing varieties of amgaite, (g,h)―Sb-rich avicennite with inclusions of native gold (Au).

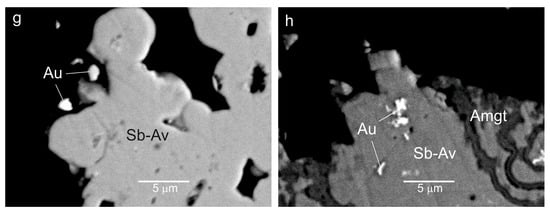

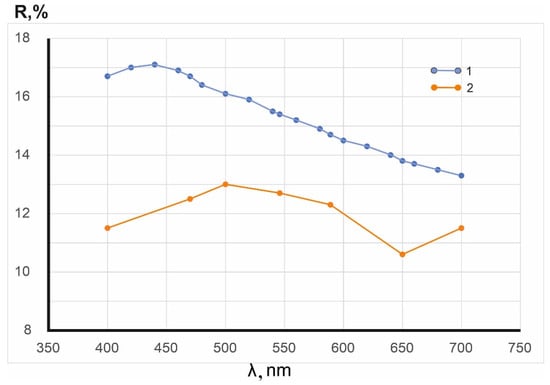

In reflected light, Sb-rich avicennite is light gray, isotropic. Internal reflections are absent. Reflection is very low; the reflectivity curve is of mixed type with a small maximum in the blue part (Figure 4). The reflectance values of the Khokhoy avicennite are shown in Table 1, compared to avicennite from the Carlin gold deposit in Nevada, USA [12]. It is seen that the reflectance values of the former are higher than those of the latter, which may be due to differences in the chemical composition of the two minerals and their grain morphology. The mineral from Nevada is chemically pure in contrast to avicennite from Russia. In addition, the grains have a porous structure, which, notoriously, can significantly understate the reflectance values.

Figure 4.

Reflectance spectra of Sb-rich avicennite from the Khokhoy gold deposit (Yakutia, Russia) (1) in comparison with avicennite from the Carlin gold deposit (Nevada, USA) (2).

Table 1.

Reflectance values of Sb-rich avicennite from the Khokhoy gold deposit (Yakutia, Russia) in comparison with avicennite from the Carlin gold deposit (Nevada, USA).

The refraction index of the Khokhoy Sb-rich avicennite, which was calculated from the recorded reflection data using a formula derived from the Fresnel equation, is n = 2.29 at λ = 546 nm.

- 2.

- Chemical Composition

Sb-rich avicennite from the Khokhoy gold deposit is stable under electron probe beam. Its chemical composition (average value on 10 analyses) is presented in Table 2, corresponding to the following empirical formula (calculation for three atoms of O): Tl3+1.40Sb5+0.30V5+0.03As5+0.03O3. In contrast to avicennite from the site of its type locality in Uzbekistan [13] and the Carlin deposit in Nevada [12], the composition of the mineral found in Russia is characterized by a significant admixture of Sb, as well as low admixtures of V and As.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of Sb-bearing avicennite from Khokhoy gold deposit (Yakutia, Russia).

- 3.

- X-ray study

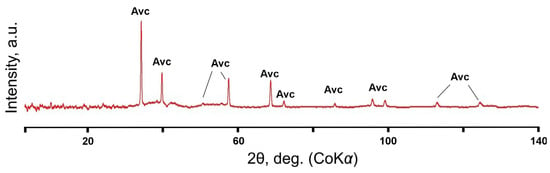

The poor quality of avicennite grains precluded their examination by single-crystal X-ray diffraction; therefore, X-ray data were obtained via powder method (Figure 5, Table 3). The unit cell parameters calculated from the powder X-ray diffraction data using UnitCell software [14] are as follows: the mineral is cubic with a = 10.496(6) Å and V = 1156(2) Å3.

Figure 5.

PXRD pattern of Sb-rich avicennite.

Table 3.

Powder X-ray diffraction data and unit cell parameters of Sb-rich avicennite from the Khokhoy gold deposit (Yakutia, Russia).

5. Discussion

An interesting feature of the Khokhoy avicennite lies in its uncommon chemical composition, particularly its antimony enrichment. Our analyses did not confirm the presence of mechanical impurities of the Sb-bearing phase: avicennite grains in the ore microscope appear homogeneous and monomineralic, whereas there are no reflections other than those belonging to avicennite on the powder diffraction pattern. In addition, we observe that the composition of impurities is reproduced on different grains. Considering all of the described facts, we believe that the identified impurities, most likely, are incorporated into the structure of the mineral, isomorphically replacing a part of Tl3+ atoms. Unfortunately, the structure of natural avicennite has not yet been studied, and the potential isomorphism involving Tl3+ has not yet been clearly defined. Nevertheless, the presence of impurities in the Khokhoy avicennite is not a unique occurrence. Previously, at the Alshar deposit in Macedonia, avicennite with As impurity (up to 6 at.%), as well as the smallest (up to 3 μm) spherulites of Tl and Sb oxide with the ratio of Tl:Sb~3:1 have been found [15].

Another discussion point is the oxidation degree of impurity elements in the Khokhoy mineral. The small size of grains and the insufficient amount of the material, unfortunately, do not allow us to determine the valence of Sb, V, and As by means of direct methods; however, we believe that all three of these impurity elements have here their highest oxidation degree at 5+. Firstly, it is connected to the strong oxidizing conditions in the supergene zone of the Khokhoy deposit: all previously studied oxygen minerals here contain chemical elements with the highest oxidation states (Tl3+ in avicennite and amgaite, Te6+ in amgaite, Fe3+ in goethite, etc.). In this regard, it is reasonable to assume that Sb, V, and As will also be oxidized to 5+. Secondly, the volume of the cubic unit cell of the Khokhoy Sb-rich avicennite (1156(2) Å3) is significantly lower than that of the pure Tl2O3, both natural—1173.17 Å3 [12] and synthetic—1180.93 Å3 [16] or 1169.04 Å3 [17]. The decrease in the cell volume is evidently due to the fact that the impurity component is lower in its ionic radius than Tl3+. The ionic radius of Tl3+ (coordination number 6) is 0.862 [18]. The ionic radii of Sb3+(6) and As3+(6) (1.077 and 1.044, respectively) are higher than this value, while the ionic radii of Sb5+(6) and As5+(6) (0.611 and 0.464) are lower, which further supports the 5+ oxidation degree of the latter.

6. Conclusions

The associated thallium mineralization, located in close connection with tellurium mineralization in gold deposits of Yakutia, has been isolated for the first time to this extent. Strong thallium enrichment of ores occurs during potassium metasomatosis in fault zones [19], which explains the presence of thallium minerals here. The crucial characteristic of the ores occurring in the Khokhoy gold deposit is that, in contrast to other gold deposits worldwide, thallium minerals here are represented primarily by oxides and tellurates, which are closely related to gold mineralization. This is due to very strong oxidizing conditions, which contributed to the formation of amgaite, wherein Tl and Te reached their highest valence states: +3 and +6, respectively [6], as well as avicennite, including its Sb-rich variety. The discovery of the latter is, in fact, the first finding in both Russia and the world.

The expansion of the list of thallium minerals in the ores of the Khokhoy gold deposit will provide grounds for the identification of promising areas of Carlin-type mineralization on the territory of the Aldan Shield.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S.A.; Methodology, G.S.A. and A.V.K.; Software, G.S.A. and A.V.K.; Validation, G.S.A. and A.V.K.; Formal analysis, G.S.A. and A.V.K.; Research, G.S.A., A.V.K., L.A.K., V.N.K. and V.V.G.; Resources, G.S.A. and A.V.K.; Data curation, G.S.A. and A.V.K.; Writing—preparation of initial draft, G.S.A. and A.V.K.; Writing—reviewing and editing, G.S.A. and A.V.K.; Visualization, G.S.A.; Management, G.S.A.; Project administration, G.S.A.; Completion of funding, G.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation (regional contest) project No. 25-27-20082.

Data Availability Statement

The information is contained in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to N. Khristoforova for assistance in SEM analysis (Diamond and Precious Metal Geology Institute, SB RAS). We thank E. Sokolov from Yakutskgeologiya for his contribution to the initial work and for the organization of field work. We also express our gratitude to all editors and anonymous reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anisimova, G.S.; Kondratieva, L.A.; Kardashevskaia, V.N. Characteristics of supergene gold of Karst cavities of the Khokhoy Gold Ore Field (Aldan Shield, East Russia). Minerals 2020, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, G.S.; Kondratieva, L.A.; Kardashevskaya, V.N. Weissbergite (TlSbS2) and avicennite (Tl2O3)—Rare thallium minerals. The first finds in Yakutia. Zap. Ross. Miner. Obs. 2021, 2, 18–27. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Anisimova, G.S.; Kondratieva, L.A.; Kardashevskaia, V.N. Weissbergite (TlSbS2) and avicennite (Tl2O3), rare thallium minerals: First findings in Yakutia. Geol. Ore Depos. 2022, 64, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratieva, L.; Anisimova, G. Minerals of Hg, Tl and As of Khokhoy deposit (Aldan shield). In Proceedings of the Geology and Mineral Resources of the North-East of Russia: Materials of the XII All-Russian Scientific and Practical Conference Dedicated to the 65th Anniversary of the Institute of Geology of Diamond and Precious Metals, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Yakutsk, Russia, 23–25 March 2022; pp. 184–188. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Kasatkin, A.V.; Anisimova, G.S.; Nestola, F.; Plášil, J.; Sejkora, J.; Škoda, R.; Sokolov, E.P.; Kondratieva, L.A.; Kardashevskaia, V.N. Amgaite, IMA 2021-104, in: CNMNC Newsletter 66. Eur. J. Mineral. 2022, 34, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasatkin, A.V.; Anisimova, G.S.; Nestola, F.; Plášil, J.; Sejkora, J.; Škoda, R.; Sokolov, E.P.; Kondratieva, L.A.; Kardashevskaia, V.N. Amgaite, Tl3+2Te6+O6, a New Mineral from the Khokhoyskoe Gold Deposit, Eastern Siberia, Russia. Minerals 2022, 12, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.V.; Sidorov, A.A. The geological-genetic model of Carlin type gold deposits. Litosphere 2016, 6, 145–165. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, C.M.; Olivo, G.R.; Chouinard, A.; Weakly, C. Mineral paragenesis, flteration and geochemistry of the two types of gold ore and the Host Rocks from the Carlin-type deposit. Econ. Geol. 2010, 105, 971–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikramuddin, M.; Besse, L.; Nordstrom, P.M. Thallium in the Carlin-type gold deposits. Appl. Geochem 1986, 1, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratieva, L.A.; Anisimova, G.S.; Sokolov, E.P.; Kardashevskaia, V.N. The Khokhoy Deposit Is a New Carlin-Type Gold-Bearing Object (the Aldan Shield). Geol. Ore Depos. 2025, 67, 428–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britvin, S.N.; Dolivo-Dobrovolsky, D.V.; Krzhizhanovskaya, M.G. Software package for processing X-ray powder data obtained via cylindrical detector Rigaku RAXIS Rapid II diffractometer. Zap. Ross. Miner. Obs. 2017, 146, 104–107. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Radtke, A.S.; Dickson, F.W.; Slack, J.F. Occurrence and formation of avicennite, Tl2O3, as a secondary mineral at the Carlin gold deposit, Nevada. J. Res. U.S. Geol. Surv. 1978, 6, 241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Konkova, E.A.; Saveliev, V.F. On a new thallium mineral—Avicennite. Zap. IMO 1960, 89, 316–320. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Holland, T.J.B.; Redfern, S.A.T. Unit cell refinement from powder diffraction data: The use of regression diagnostics. Mineral. Mag. 1997, 61, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, T.; Kolitsch, U.; Drahota, P.; Peresta, M.; Majzlan, J.; Tasev, G.; Serafimovski, T.; Boev, I.; Boev, B. Tl sequestration in the middle part of the Tl–Sb–Au Allchar deposit, North Macedonia. In Proceedings of the Goldschmidt 2021, Virtual, 4–9 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, H.H.; Baltrush, R.; Brant, H.J. Further evidence for Tl3+ in Tl-based superconductors from improved bond strength parameters involving new structural data of cubic Tl2O3. Phys. C 1993, 215, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariasen, W. The crystal structure of the modification C of the sesquioxides of the rare earth metals, and of indium and thallium. Nor. Geol. Tidsskr. 1927, 9, 310–316. [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne, F.; Gagné, O. New ion radii for oxides and oxysalts, fluorides, chlorides and nitrides. Acta Cryst. 2024, B80, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevyrev, L.T. Regularities in the volatile elements distributions within the surficial envelope of Earth: Probable historical-metallogenic interpretation. Proc. Voronezhsk. Gos. Univ. 2015, 3, 5–16. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).