Abstract

This work focuses on the development of a patient-specific transient CFD–FSI numerical model combined with the Time-Averaged Entropy Generation Rate (TAEGR) to predict hemodynamic parameters in the thoracic aorta, including the Oscillatory Shear Index (OSI) and the Time-Averaged Wall Shear Stress (TAWSS). While arterial blood flow can be modeled assuming either rigid or elastic arterial walls, the effect of wall compliance on these parameters, particularly on TAEGR, remains insufficiently characterized. Moreover, the interpretation of established indicators is not unique, as regions of vascular relevance may correspond to either high or low values of OSI and TAWSS. The proposed approach aims to identify symmetry and asymmetry in shear stress and entropy generation within the arterial wall, which are closely associated with the development of atherosclerotic plaque. Four aortas from clinical patients were analyzed using the proposed numerical framework to investigate blood flow behavior. The results revealed regions with high values of the hemodynamic parameters (OSI > 0.15, TAWSS ≥ 2 Pa, and TAEGR ≥ 20 ) predominantly located in the vicinity of the upper arterial branches. These regions, referred to as critical zones, are considered prone to the development of cardiovascular diseases, particularly atherosclerosis. The proposed numerical model provides a reliable qualitative framework for assessing symmetry and asymmetry in aortic blood flow patterns under different surgical conditions.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide [1]. Among these conditions, atherosclerosis is characterized by the formation, progression, and rupture of fatty plaques in the inner layer of the thoracic aorta (TA). Its main clinical manifestations include ischemic heart disease, ischemic stroke, and peripheral arterial disease [2]. According to some authors, wall shear stress (WSS) is directly related to atherosclerotic pathologies within the aorta [3,4,5,6]. Some other studies associate the evolution of fatty plaque with low WSS values (<1.5 Pa) [7,8,9]. Several authors have studied hemodynamic parameters in the blood flow; for example, Abazari et al. [10] evaluated the TAWSS, HOLMES, and flow patterns in aortas exhibiting a certain degree of dissection. Using CFD, they analyzed three case studies under different heartbeat conditions. Their results indicated that a decrease in TAWSS helps prevent tearing or rupture of the arterial wall, whereas an increase in HOLMES contributes to improved control of calcification and the formation of fatty plaques within the arteries. Camarda et al. [11] used the fluid–structure interaction (FSI) to simulate blood flow and obtain the hemodynamic parameter values inside the aorta artery for patients (men and women) with different kinds of diseases. As a result, they observed that the differences between TAWSS and OSI were due to the local morphology of the aorta artery and to the velocity of the blood flow leaving the heart. Wang et al. [12] conducted a study to assess the risk of thrombosis and aneurysm rupture based on patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. The results showed that zones with high OSI values and low TAWSS values increase as the aneurysm diameter increases, with a diameter of 5 cm exhibiting the largest extent of such regions. Similarly, Bozorgpour et al. [13] analyzed how the aneurysm evolution affects the hemodynamic parameters TAWSS and OSI, finding that low TAWSS values and high OSI values are associated with aneurysm rupture. Praharaj et al. [14] and Kamangar [15] evaluated flow patterns, as well as the OSI and TAWSS values, in arteries with stenosis. In these studies, variations in the size and shape of the stenosis were considered for each patient, revealing that an increase in TAWSS is associated with a higher degree of arterial stenosis. Soares et al. [16] performed CFD simulations to evaluate hemodynamic parameters and characterize the blood flow behavior within the abdominal aorta. These simulations enabled the identification of regions prone to atherosclerosis development in the patient. Wang et al. [17] used CFD techniques to evaluate hemodynamic parameters in dissected aortas implanted with stent grafts, concluding that low WSS values and high relative residence time (RRT) indicate an increased risk of thrombosis. Other authors have reported that regions with high OSI values (OSI ≥ 0.15) and low TAWSS values (≤0.4 Pa) are prone to the development of atherosclerosis [18]. Lantz et al. [19] performed a study of blood flow in the thoracic aorta and proposed a novel way to localize regions susceptible to atherosclerosis. By plotting OSI against TAWSS, they found that regions with high OSI values (>0.15) and TAWSS values ≥ 2 Pa coincide with critical zones associated with atherosclerosis development.

As demonstrated in the studies discussed above, some authors have analyzed arterial flow in the human body considering both rigid and elastic arterial walls. However, only a limited number of studies have performed this comparison for established hemodynamic parameters, and, to date, no studies have examined the TAEGR parameter while accounting for arterial wall elasticity. In addition, there is no unique criterion regarding the critical values of conventional indicators, since regions of vascular risk have been associated with either elevated or reduced values of TAWSS and OSI, depending on the adopted assumptions and evaluation criteria. For this reason, this study presents a hemodynamic analysis of both rigid and elastic arterial walls to compare and evaluate OSI, TAWSS, and the novel parameter TAEGR, proposed by Crespo et al. [20], in four human aortas, as well as to examine the influence of aortic geometry, where partial symmetry and curvature-driven asymmetry play a decisive role in these parameters.

2. Materials and Methods

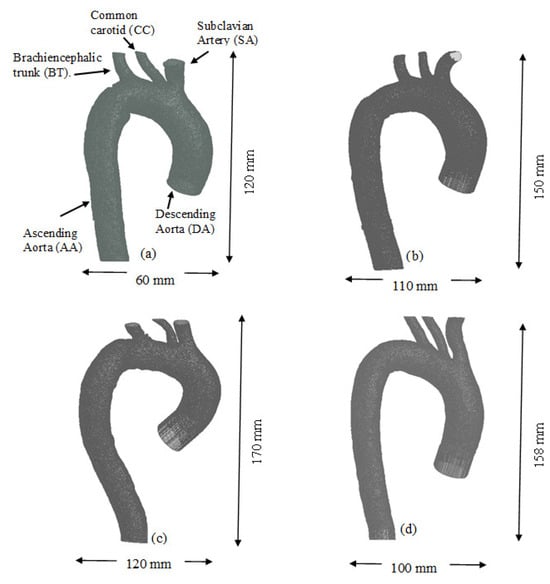

For this research, commercial software was used to perform numerical simulations based on the finite volume method (ANSYS Fluent v16, ANSYS Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA), employing the various tools available within the Workbench® platform. The first step involved importing the geometry into the Design Modeler® module included in the ANSYS® software. The human aorta geometries used in this study are shown in Figure 1; they were obtained from healthy adult subjects and include the ascending aorta (AA), the left common carotid artery (CC), the left subclavian artery (SA), the descending aorta (DA), and the brachiocephalic trunk (BT). These geometries were acquired using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) through a collaborative effort with Malvé et al. [21].

Figure 1.

Geometries of the (a) TA #1, (b) TA #2, (c) TA #3, and (d) TA #4.

Once each arterial geometry was imported into the software, the models were meshed, and their boundary conditions were defined using the Meshing® program. A combination of ‘pressure_outlet’ and ‘velocity_inlet’ boundary conditions was implemented to accurately predict the velocity and pressure fields within the aortic geometry [22] (see Figure 2a). Using these boundary conditions, a comparison between the expected physiological flow distribution and the flow obtained in the simulation was performed, as shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

(a) Boundary conditions used in the TA, (b) mesh used for the computational model.

Table 1.

Expected physiological flow distribution and flow obtained using the imposed boundary conditions.

Some assumptions in this study, for the fluid part, are as follows: unsteady state (time step = 0.01 s), pulsatile flow, Newtonian fluid, and laminar regime. The reason for a laminar regime instead of a turbulent one, despite the calculated Reynolds number being close to 9000, is based on two considerations. First, this Reynolds number corresponds to peak systole, which represents only a brief portion of the cardiac cycle; during most of the cycle, the flow remains laminar, with Reynolds numbers on the order of 1000. Second, according to the literature, several authors have reported that this flow assumption provides a reasonable approximation of blood flow behavior [23,24,25]. The SIMPLE (Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure-Linked Equations) scheme was employed for pressure–velocity coupling, as it is widely adopted in CFD due to its efficiency and robustness for incompressible flows. Spatial discretization was performed using a second-order upwind interpolation scheme for the momentum and scalar transport equations in order to enhance the accuracy in resolving flow gradients, particularly in regions characterized by recirculation and curved geometry [26]. The fluid (blood) was modeled with a density of 1063 kg/m3 and a dynamic viscosity of 0.0035 kg/m∙s.

The primary variable employed for the mesh sensitivity analysis in the fluid domain was the maximum TAEGR over the cardiac cycle. The simulations were performed using meshes consisting of 1,270,000, 1,450,129, 2,732,594, 3,983,900, 5,010,560, 5,263,892, and 5,470,544 elements. The relative difference between the mesh with 5,010,560 elements and the finest mesh was found to be only 0.13%. Consequently, the mesh comprising 5,010,560 elements was selected for the final simulations. The resulting mesh is illustrated in Figure 2b.

For the structural domain, a solid body was created to represent the aortic arterial wall and its interaction with blood flow. The aortic arterial wall model was based on ex vivo measurements of human aortas reported by Wuyts et al. [27]. Figure 3 shows the thickness of the arterial wall at the inflow and outflow regions of the aorta. The wall thickness, denoted as “”, was calculated as a function of lumen diameter and age using a simplified relation proposed by Wuyts et al. [27], as expressed by the following equation:

Figure 3.

Thickness of the arterial wall.

The arterial wall was modeled as an isotropic, linear elastic material. This simplification was adopted because, although the aortic wall exhibits anisotropic and nonlinear mechanical behavior, this approximation is considered adequate for the objectives of the present work, which are focused on the comparative analysis of hemodynamic parameters and on the relative influence of wall elasticity. The density was set to 1062 kg/m3, and isotropic elasticity was defined using a Young’s modulus of 4.66 MPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.45. The structural mesh consisted of 1,132,252 elements, including quadrilateral and tetrahedral cells.

Finally, the hemodynamic parameters TAWSS, defined as the tangential force associated with viscous shear stress; OSI, which describes the cyclic behavior of TAWSS; and TAEGR, which represents the time-dependent variation of entropy within the arteries, were evaluated. The governing equations for these parameters are shown in Equations (2)–(4).

where is the WSS vector, and is the period of the cycle.

The OSI ranges from 0 to 0.5, where a value of 0 corresponds to a unidirectional WSS vector, and a value of 0.5 indicates that the instantaneous vector is oscillatory.

For the TAEGR parameter, the solution methodology is described in Crespo et al. [20]. In this new parameter, only the contribution due to viscous stress () is considered.

It is important to mention that all methods performed in this work follow the guidelines published in the World Medical Association (WMA) Declaration of Helsinki [28].

3. Results

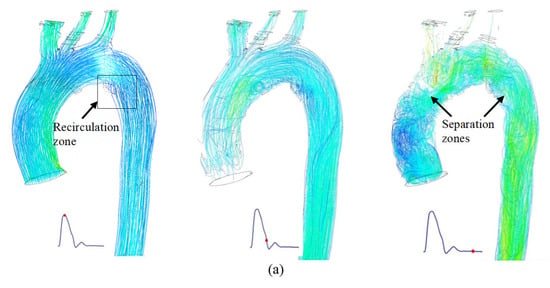

The velocity lines for the aortas are shown in Figure 4. The flow considerations are laminar and Newtonian flow. All cases were analyzed at three points in the cardiac cycle, i.e., peak systole (left), end systole (center), and end diastole (right). In the case of TA #1, the velocity lines are shown in Figure 4a. At the peak of systole (left), it is clearly observed that the flow has an increase in velocity between the first two arterial branches (BT and CC) and reaches a Reynolds number close to 9000. This is due to the division of flow and the curvature-driven asymmetry that this zone presents. The recirculation zones are important areas in the study of atherosclerosis and are shown in the black box. The flow in this zone is oscillatory, and its rotation is clockwise, similar to the flow patterns presented by some authors [19]. Since velocity decreases during the deceleration of blood flow, it is important to know the behavior of the velocity vectors and patterns during this phase of the cardiac cycle. The first flow separation zone is observed in the first curvature of the aorta, between the AA and the aortic arch, while the second is located near the descending aorta (DA), in close proximity to the recirculation zone. At this stage of the cardiac cycle, the Reynolds number is approximately 1000.

Figure 4.

Velocity lines during the 3 phases of the cardiac cycle for the: (a) TA #1, (b) TA #2, (c) TA #3, and (d) TA #4.

For the velocity lines of TA #2, shown in Figure 4b, the same pattern observed in TA #1 is evident. During peak systole (left), a symmetric flow pattern and an increase in velocity at the flow division within the superior arterial branches are observed. However, in this aorta, no recirculation zones are observed, which is normal because not all TA geometries are the same. For end systole (center), helical and asymmetric flow patterns are observed in the flow separation zones, and the velocity vectors appear completely disordered, similar to those in TA #1. The first flow separation zone is shown in the AA, while the second is between the DA and the aortic arch. Figure 4c shows the velocity lines of TA#3. In this aorta, the only feature that differs from the cases above is that, at the peak of systole (left), a recirculation zone is observed in the aortic arch, close to the SA, which is also observed at the end of systole (center) and diastole (right). The flow separation zones observed at the end of diastole are present in the AA and DA, as in TA#2. For TA #4, the velocity streamlines are shown in Figure 4d. At peak systole (left), a small recirculation region can be observed in the aortic arch, located nearly in the same area as that identified in TA #1. The results presented above highlight the complexity of aortic blood flow, as even small geometric variations can lead to significant changes in flow patterns. As mentioned earlier, alterations in flow symmetry and asymmetry may contribute to the development of certain aortic diseases.

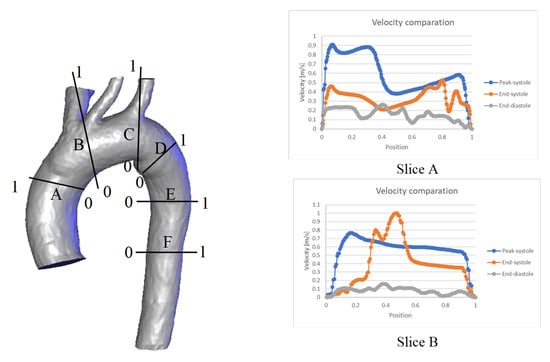

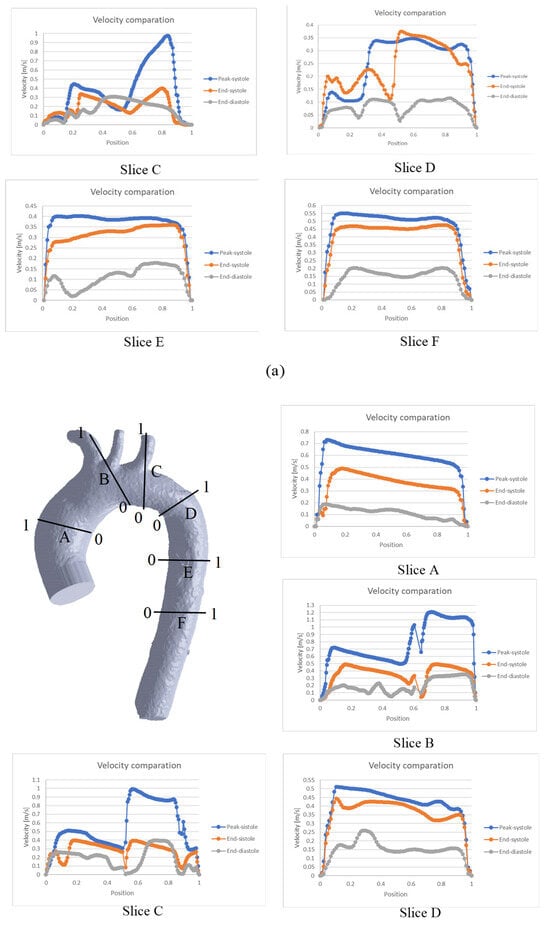

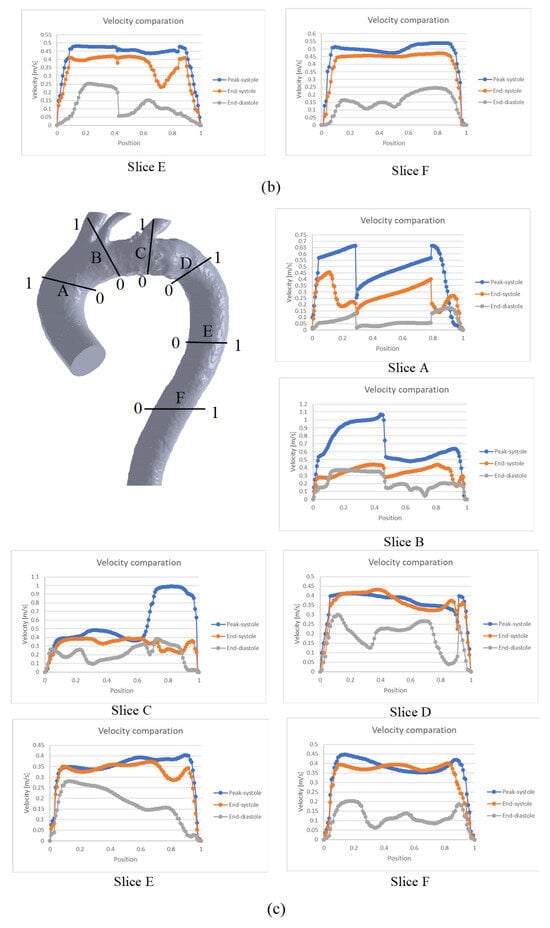

To further characterize the behavior shown in Figure 4, a graphical comparison of six specific zones throughout the entire cardiac cycle is presented in Figure 5. In general, the velocity profiles for each slice depend on the aortic geometry and may vary both qualitatively and quantitatively (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of velocity throughout the cardiac cycle for the: (a) TA #1, (b) TA #2, (c) TA #3, (d) TA #4.

In the case of TA#1 (Figure 5a), slice A shows that, at the end of systole, the blood flow becomes asymmetric in the distal AA. This behavior is due to the backflow from the upper arteries during this phase of the cardiac cycle, which combines with the ascending flow in the TA. In slice B, the velocity at the end of the systole is greater than the velocity in the peak systole in some TA positions (position 0.8), and the velocity at the end of the diastole is greater than the velocity at the end of the systole in the 0.4 position of the TA. This behavior is due to the fact that blood flow in this zone of the TA#1 undergoes a flow division, and there is a reverse flow in the upper arterial branches, which mixes with the flow passing through the aortic arch and increases its velocity. In the case of slice D, the behavior observed in the three phases is caused by the fact that this section is located in a recirculation zone; therefore, the velocity shows this type of fluctuation. For slices E and F, the flow remains symmetric, indicating the absence of anomalies in the flow or along the arterial wall.

For the case of the TA#2 (Figure 5b), blood flow at the end of diastole exhibits asymmetric behavior in the upper arterial branches, as observed in slices B and C. As in TA#1, this flow disturbance is attributed to backflow from the upper arterial branches. Meanwhile, in slices A, D, E, and F, the flow remains orderly due to the uniformity of the geometry.

Figure 5c shows the blood flow behavior for TA#3, showing that during both phases of the cardiac cycle, the flow exhibits disordered patterns in the aortic arch and the upper arterial branches. This occurs because at several points, the flow velocity at the end of the diastole is greater than at the end of the systole, as shown in slices A, B, and C. This behavior is due to the return flow in the upper arterial branches, which was explained in previous sections. For the case of the velocity drops shown in slices A and B, this is due to a recirculation zone or a flow separation zone at the positions where this behavior is observed in the graph.

The behavior of the TA#4 (Figure 5d) shows a flow disorder only in the upper arterial branches, as shown in slices B and C, indicating minimal overall flow recirculation for this geometry. The velocity reductions observed in slices A, B, and C are also attributed to the location of these sections within recirculation or flow separation zones caused by backflow.

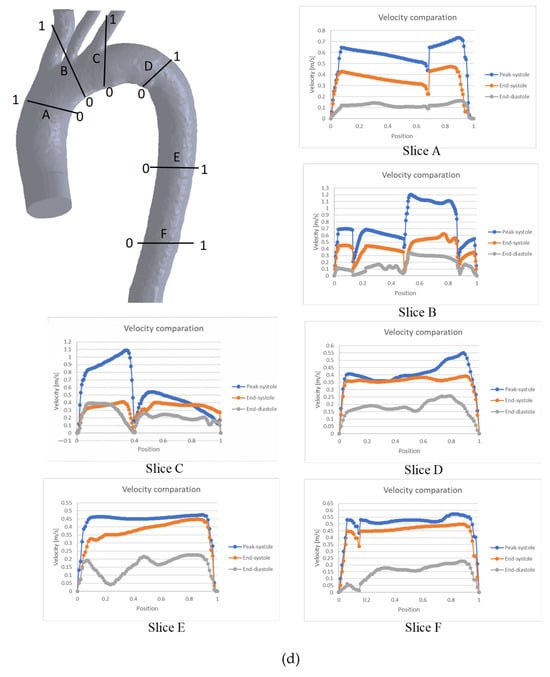

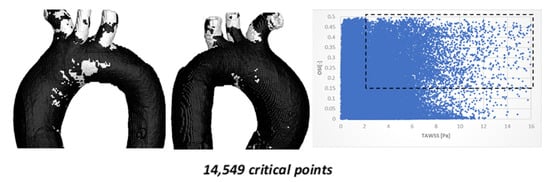

3.1. Comparison Between TAWSS, OSI, and TAEGR Considering Only the Fluid Part

The methodology employed in this work was originally proposed by Lantz et al. [19]. The WSS values were extracted from Fluent® and post-processed to obtain the parameters of interest. In the case of TA #1 (Figure 6), a total of 210,328 points on the aortic surface were used to calculate OSI, TAWSS, and TAEGR values. In the upper region of Figure 6, an inverse relationship between OSI and TAWSS is observed: low TAWSS values correspond to high OSI values, and vice versa. However, a limited number of points exhibit a different behavior, namely high OSI values combined with high TAWSS values; these points are highlighted within the black rectangular region in the same plot. The range of values within this region is defined by 2 ≤ TAWSS ≤ 16 and 0.15 ≤ OSI ≤ 0.5. Points falling within this range are considered critical, as most of them are located near the arterial branches, which are regions prone to the development of atherosclerosis in the thoracic aorta (TA) [7,10]. These critical points were mapped back onto the aortic geometry and are shown as white dots in the frontal and anterior views of the TA, displayed below the graph in Figure 6. These results show a strong spatial agreement between the critical points identified by Lantz et al. [19] and those obtained in this study.

Figure 6.

OSI vs. TAWSS using 210,328 points on the aortic surface (top). The points within the dotted rectangle show the critical zones for the development of atherosclerosis (bottom).

The same procedure for calculating the TAEGR is shown in Figure 7. Critical zones for this new hemodynamic parameter appear only in the vicinity of the arterial branches, which, as mentioned above, are prone zones to develop atherosclerosis. The main difference between the zones shown in Figure 7 and those in Figure 6 is that the critical points presented in the OSI vs. TAWSS graph are located along the arterial branches, with only a few found in the curvature of the BT and SA. Meanwhile, zones with critical values of the TAEGR are mostly in the vicinity of the two arteries (BT and SA) and only a few along the arterial branches. This is an expected behavior, indicating that the zones prone to developing atherosclerosis are located, mostly, in the vicinity of the branches [6,9].

Figure 7.

TAEGR using 210,328 points on the surface of TA #1.

Comparison of OSI vs. TAWSS hemodynamic parameters for TA #2 is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

TAWSS vs. OSI using 215,085 points on the surface of TA #2.

Figure 8 shows the critical zones identified by the TAWSS–OSI parameters for TA #2, with a total of 17,124 (8.00%) critical points. As in the previous aorta, most of these points are located in the arterial branches. However, unlike the previous case, TA #2 exhibits approximately 1000 critical points in the aortic arch. These critical zones are located far from the recirculation areas, which are typically considered the regions most prone to disease development. Nevertheless, this does not imply that the areas identified by these parameters are non-risk zones, as risk regions depend primarily on aortic geometry. Furthermore, the current aorta exhibits different curvature characteristics compared to the previous aorta.

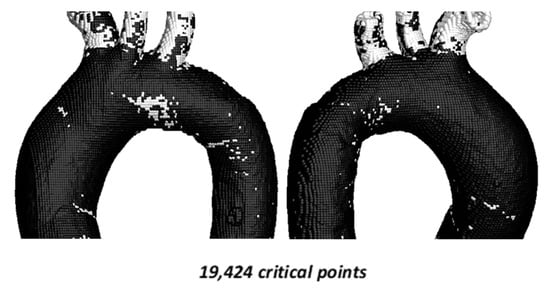

The comparison of the hemodynamic parameter TAEGR is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

TAEGR using 217,923 points on the surface of TA #2.

For this case, a total of 19,424 critical points (8.91%) were identified. Critical zones are observed in the aortic arch, coinciding with those detected in the TAWSS–OSI analysis; however, the density of critical points in this region is more than 50% lower and approximately 10% lower in the upper arterial branches.

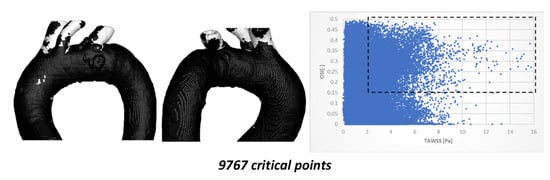

Once the simulations of TA #2 were completed, the simulations of TA #3 were carried out, using the same flow considerations. The results of the comparison between TAWSS and OSI hemodynamic parameters are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

TAWSS vs. OSI using 198,227 points on the surface of TA #3.

Figure 10 illustrates the critical zones highlighted within the black box (2 ≤ TAWSS ≤ 16 and 0.15 ≤ OSI ≤ 0.5), with a total of 9767 critical points (4.92%). In this case, most critical points are located in the superior arterial branches, while only a small fraction (less than 15%) appear in the arterial curvatures. The critical zone identified in the aortic arch is relatively small (fewer than 150 points); although its density is sufficient for clear visualization, it remains spatially distant from the arterial recirculation zones.

Once the results for the TAWSS vs. OSI parameters were obtained, Figure 11 shows the results for the TAEGR parameter.

Figure 11.

TAEGR using 198,533 points on the surface of TA #3.

The critical zones are practically the same as those identified in the TAWSS vs. OSI comparison; however, a new small zone appears in the aortic arch, near the recirculation zone (red circle) with around 10 critical points, as well as another zone in the ascending aorta.

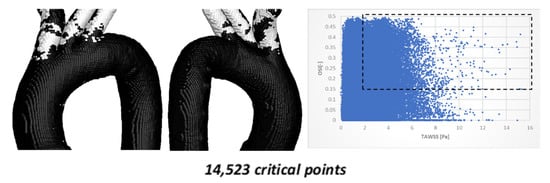

The results of the comparison between TAWSS vs. OSI hemodynamic parameters for TA #4 are shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

TAWSS vs. OSI using 204,962 points on the surface of TA #4.

Figure 12 shows the critical zones detected by the TAWSS vs. OSI parameters, with a total of 14,523 critical points (7.42%). As in the previously simulated aorta, most of the points are located in the superior arterial branches, with only a small fraction (less than 25%) appearing in the curvatures. The most significant difference compared to the previous aortic model is the absence of hemodynamically critical regions in the curvature. This morphological feature suggests a lower atherosclerotic predisposition for this specific geometry.

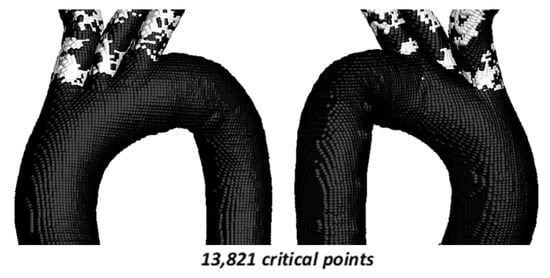

The comparison of the hemodynamic parameter TAEGR and the critical zones detected is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

TAEGR using 204,962 points on the surface of TA #4.

In this case, a total of 13,821 critical points (6.74%) are identified, and the critical zones are similar to those observed for the TAWSS vs. OSI comparison. However, for the TAEGR, the critical points are concentrated in the curvatures of the upper arterial branches, while for the TAWSS vs. OSI comparison, they are concentrated along these arterial branches.

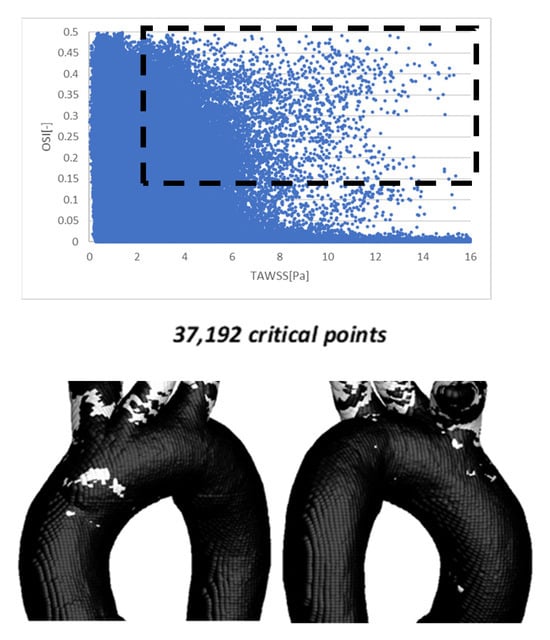

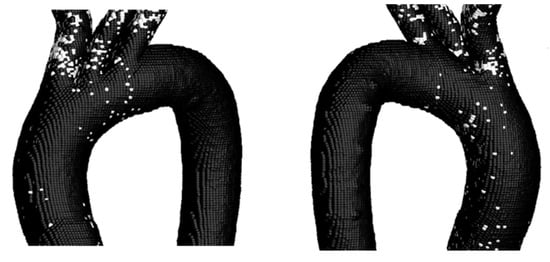

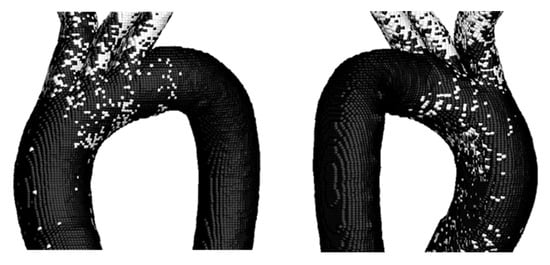

3.2. Comparison Between TAWSS–OSI and TAEGR Considering FSI Methodology

Simulations that account for arterial wall elasticity require solving a fluid–structure interaction (FSI) problem, which substantially increases numerical complexity, computational cost, and convergence time. Therefore, in this study, two representative aortic geometries (TA#1 and TA#4) were selected for the simulations with elastic walls. This approach allowed the main hemodynamic trends associated with wall deformability to be captured while maintaining a balance between computational feasibility and analytical depth. Given that the main objective of this work is to compare hemodynamic differences between the rigid and elastic wall assumptions, the selected cases were considered sufficient to highlight the most relevant differences between the two models without excessively broadening the scope of the study.

Figure 14 shows that the number of critical zones on the surface of TA #1 is lower than in the case where only a rigid wall is considered. However, critical zones are still observed in the upper arterial branches, while the critical zone previously identified in the aortic arch disappears.

Figure 14.

TAEGR on the surface of TA #1.

To observe the difference between the hemodynamic parameters TAWSS, OSI, and TAEGR, the critical zones identified through the TAWSS–OSI comparison were also analyzed, as shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

TAWSS vs. OSI on the Surface of TA #1.

In this case, the results are similar to those obtained for the rigid wall, with most critical points located along the upper arterial branches and a small zone appearing near the aortic arch.

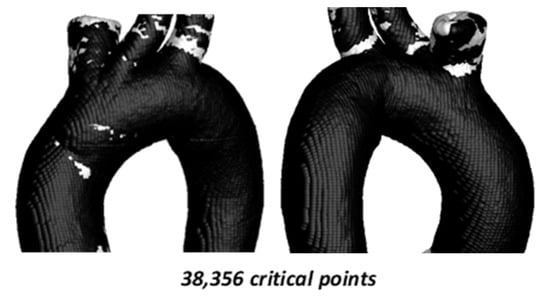

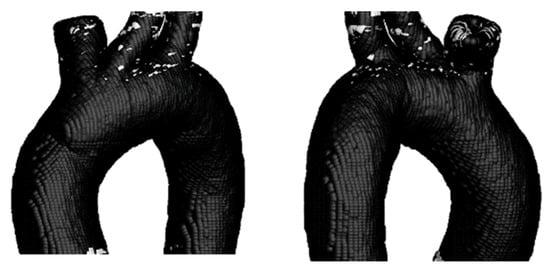

Subsequently, TA#4 was analyzed to examine the differences between the elastic and rigid wall assumptions (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

TAEGR on the surface of TA #4.

The figure above shows that the zone with the highest density of critical points is at the inlet of the BT; however, a small critical zone is also observed in the curvature of the aortic arch of the TA. Following the analysis of this parameter, the comparison of the TAWSS and OSI parameters is presented in Figure 17.

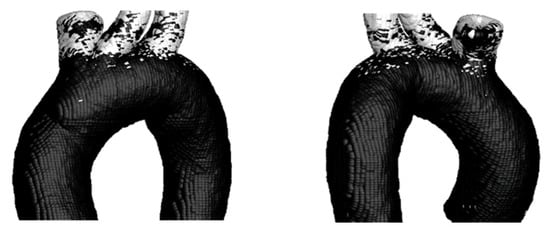

Figure 17.

TAWSS vs. OSI on the Surface of TA #4.

As in the previous cases, a higher number of critical points is observed compared to those obtained for the TAEGR parameter, indicating that, based on the comparison of these parameters, the three upper arterial branches exhibit a tendency toward the development of diseases such as atherosclerosis. In addition, these parameters also show a high number of critical points in the aortic arch, similar to the previous parameter. However, under this comparison, critical points are still observed in the DA.

4. Conclusions

The analyzed arteries indicate that segments with approximate geometric symmetry exhibit more stable flow patterns, whereas asymmetric regions promote recirculation and flow separation zones along the aortic arch and ascending aorta, which is consistent with the established literature. These observations confirm the validity of the hemodynamic simulations performed. Moreover, the velocity patterns observed at different phases of the cardiac cycle show good agreement with previously reported studies. This agreement confirms that the pressure and velocity profiles did not introduce anomalies during the cardiac cycle and that fully developed flow conditions were achieved for the calculation of OSI and TAWSS.

The OSI, TAWSS, and TAEGR results exhibit the expected hemodynamic behavior, with regions prone to disease, particularly atherosclerosis, primarily localized near the upper arterial branches. These regions are characterized by OSI values ≥ 0.15, TAWSS values ≥ 2 Pa, and TAEGR values ≥20 . When comparing the critical regions identified by TAEGR with those obtained from OSI and TAWSS, a partial overlap between the different metrics is observed. However, OSI and TAWSS tend to highlight critical points mainly along the supra-aortic branches, which are anatomical regions not typically associated with the development of vascular pathologies, whereas TAEGR concentrates most of its critical regions in the aortic curvatures and in the aortic arch, which are not detected by the other hemodynamic parameters. This behavior is explained by the fact that TAEGR is sensitive to intense velocity gradients and viscous dissipation within the bulk flow, while OSI and TAWSS are exclusively based on the behavior of wall shear stress.

When considering the arterial wall as elastic, the TAEGR reduced its number of critical points by up to 52% compared to the rigid arterial wall. This behavior is expected, since the arterial wall becomes smoother as its diameter increases. In contrast, the TAWSS vs. OSI comparison shows an increase in the number of critical points of up to 16%, indicating that the new parameter, TAEGR, is sensitive to arterial wall deformation, whereas the conventional parameters are not.

The distinct velocity profiles and the OSI, TAWSS, and TAEGR results obtained in this study demonstrate that aortic geometry significantly affects both the magnitude and spatial distribution of these parameters, producing noticeable qualitative and quantitative effects.

Compared with other hemodynamic parameters such as OSI and TAWSS, which are kinematic descriptors of wall shear behavior, and with RRT, which is derived from the former two, the hemodynamic parameter TAEGR quantifies the irreversible mechanical energy losses associated with viscous dissipation within the aortic flow. This implies that TAEGR provides direct information on flow inefficiency, and its clinical value lies in offering a complementary and energetically meaningful perspective on altered hemodynamics, particularly in complex patient-specific aortic configurations.

Although the present analysis focuses on qualitative hemodynamic indicators rather than statistical quantification, the observed trends consistently demonstrate the sensitivity of the hemodynamic parameter TAEGR to morphological variations within the aorta. While quantitative geometric descriptors such as curvature, torsion, and branching angles were not explicitly computed in this study, previous parametric investigations, such as that proposed by Cilla et al. [29], have shown that geometric parameters of this type exert a direct influence on hemodynamic patterns. Nevertheless, the objective of the present work was not to isolate the individual contribution of each geometric descriptor but rather to analyze the resulting hemodynamic response in anatomically realistic configurations. In this context, the critical threshold values adopted for OSI, TAWSS, and TAEGR were applied uniformly across all cases, and their robustness or sensitivity to inter-patient geometric variability was not explicitly evaluated. The presented numerical framework serves as a valuable tool for assessing aortic hemodynamics. This approach can be applied to the following:

- Pathological case evaluations;

- Virtual surgical scenarios involving aortic morphological modifications;

- Analysis of conditions producing substantial variations in the considered hemodynamic indices.

From a biological perspective, elevated TAEGR values indicate regions of highly energy-dissipative blood flow that impose non-physiological mechanical stimuli on the endothelium, a condition associated with endothelial dysfunction and directly linked to the progression of vascular pathologies such as atherosclerosis.

The methodology proposed in this study not only represents a methodological contribution in terms of hemodynamic parameter assessment, but the critical zones identified through the computation of OSI, TAWSS, and TAEGR also allow the identification of localized regions exposed to unfavorable hemodynamic environments, which are known to correlate with vascular pathology and wall degeneration. In this sense, the results may assist cardiovascular clinicians in detecting high-risk areas, monitoring disease progression, and evaluating the hemodynamic impact of different surgical strategies in a virtual setting prior to the patient’s final treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.R.-A.; Methodology, J.d.J.R.-M. and D.A.R.-A.; Software, J.A.C.-Q.; Validation, J.A.C.-Q., A.V.-L. and O.A.L.-N.; Investigation, J.A.A.-A.; Resources, M.Á.M.B.; Data curation, M.M.; Visualization, J.d.J.R.-M.; Supervision, A.V.-L. and M.Á.M.B.; Project administration, O.A.L.-N.; Funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Lumen Diameter [mm] | |

| H | Wall Thickness of the Aorta [mm] |

| OSI | Oscillatory Shear Index [-] |

| TAWSS | Time Average Wall Shear Stress [Pa] |

| TAEGR | |

| Tp | Period Cycle [s] |

| WSS | Wall Shear Stress [Pa] |

| Μ | Dynamic Viscosity kg/m |

| Ρ | Density [kg/m3] |

Abbreviations

| AA | Ascending Aorta |

| BC | Boundary Conditions |

| BT | Brachiocephalic Trunk |

| CC | Carotid Artery |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| DA | Descending Aorta |

| FSI | Fluid–Structure Interaction |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Image |

| SA | Subclavian Artery |

| TA | Thoracic Aorta |

| WMA | World Medical Assembly |

References

- World Health Organization, Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Herrington, W.; Lacey, B.; Sherliker, P.; Armitage, J.; Lewington, S. Epidemiology of Atherosclerosis and the Potential to Reduce the Global Burden of Atherothrombotic Disease. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.L.; Thavornpattanapong, P.; Cheung, S.C.P.; Tu, J.Y. Biomechanical investigation of pulsatile flow in a three-dimensional atherosclerotic carotid bifurcation model. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2013, 13, 1350001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, C.L.; Ilegbusi, O.J.; Hu, Z.; Nesto, R.; Waxman, S.; Stone, P.H. Determination of in vivo velocity and endothelial shear stress patterns with phasic flow in human coronary arteries: A methodology to predict progression of coronary atherosclerosis. Am. Heart J. 2002, 143, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, P.F. Hemodynamic shear stress and the endothelium in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2009, 6, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, E.; Giglioli, C.; Valente, S.; Lazzeri, C.; Gensini, G.F.; Abbate, R.; Mannini, L. Role of hemodynamic shear stress in cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2011, 214, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Tempel, D.; Van Haperen, R.; Van Der Baan, A.; Grosveld, F.; Daemen, J.A.P.; Krams, R.; De Crom, R. Atherosclerotic lesion size and vulnerability are determined by patterns of fluid shear stress. Circulation 2006, 113, 2744–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irace, C.; Cortese, C.; Fiaschi, E.; Carallo, C.; Farinaro, E.; Gnasso, A. Wall Shear Stress Is Associated with Intima-Media Thickness and Carotid Atherosclerosis in Subjects at Low Coronary Heart Disease Risk. Stroke 2004, 35, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J.J.; Usami, S.; Chien, S. Vascular endothelial responses to altered shear stress: Pathologic implications for atherosclerosis. Ann. Med. 2009, 41, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abazari, M.A.; Rafieianzab, D.; Soltani, M.; Alimohammadi, M. The effect of beta-blockers on hemodynamic parameters in patient-specific blood flow simulations of type-B aortic dissection: A virtual study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarda, J.A.; Dholakia, R.J.; Wang, H.; Samyn, M.M.; Cava, J.R.; LaDisa, J.F. A Pilot Study Characterizing Flow Patterns in the Thoracic Aorta of Patients With Connective Tissue Disease: Comparison to Age- and Gender-Matched Controls via Fluid Structure Interaction. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 772142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, K.; Chen, K.; Wu, P.; Li, X. A hemodynamic analysis of energy loss in abdominal aortic aneurysm using three-dimension idealized model. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1330848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozorgpour, R.; Youssof Zadeh, V.; Rammer, J.R. Hemodynamic Markers: CFD-Based Prediction of Cerebral Aneurysm Rupture Risk. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2025, 162, 107578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praharaj, P.; Sonawane, C.; Pandey, A.; Kumar, V.; Warke, A.; Panchal, H.; Ibrahim, R.; Prakash, C. Numerical analysis of hemodynamic parameters in stenosed arteries under pulsatile flow conditions. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2023, 20, 100265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamangar, S. Influence of Multi Stenosis on Hemodynamic Parameters in an Idealized Coronary Artery Model. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2022, 15, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.A.; Carvalho, F.A.; Leite, A. Wall Shear Stress-Based Hemodynamic Descriptors in the Abdominal Aorta Bifurcation: Analysis of a Case Study. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2021, 14, 1657–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Armour, C.; Ma, T.; Dong, Z.; Xu, X.Y. Hemodynamic parameters impact the stability of distal stent graft-induced new entry. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydrychowicz, A.; Stalder, A.F.; Russe, M.F.; Bock, J.; Bauer, S.; Harloff, A.; Berger, A.; Langer, M.; Hennig, J.; Markl, M. Three-dimensional analysis of segmental wall shear stress in the aorta by flow-sensitive four-dimensional-MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2009, 30, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz, J.; Rolan, G.; Karlsson, M. Quantifying turbulent wall shear stress in a subject specific human aorta using. Med. Eng. Phys. 2012, 34, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, J.A.; Alfaro, J.A.; Ramírez, J.J.; Vidal, A.; Cano, S. A detailed analysis in thoracic aorta by means of the entropy generation rate: Prediction of the atherosclerotic lesion. J. Eng. Med. 2022, 236, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvè, M.; Chandra, S.; García, A.; Mena, A.; Martínez, M.A.; Finol, E.A.; Doblaré, M. Impedance-based outflow boundary conditions for human carotid haemodynamics. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 17, 1248–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yull Park, J.; Young Park, C.; Mo Hwang, C.; Sun, K.; Goo Min, B. Pseudoorgan boundary conditions applied to a computational fluid dynamics model of the human aorta. Comput. Biol. Med. 2007, 37, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannoglou, G.D.; Soulis, J.V.; Farmakis, T.M.; Giannakoulas, G.A.; Parcharidis, G.E.; Louridas, G.E. Wall pressure gradient in normal left coronary artery tree. Med. Eng. Phys. 2005, 27, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmakis, T.M.; Soulis, J.V.; Giannoglou, G.D.; Zioupus, G.J.; Louridas, G.E. Wall shear stress gradient topography in the normal left coronary arterial tree: Possible implications for atherogenesis. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2004, 20, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, J.; Wong, K.K.L.; Cheung, S.C.P.; Beare, R.; Phan, T. Analysis of patient-specific carotid bifurcation models using computational fluid dynamics. J. Med. Imaging Health Informat. 2011, 1, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinman, D.A.; Milner, J.S.; Norley, C.J.; Lownie, S.P.; Holdsworth, D.W. Image-based computational simulation of flow dynamics in a giant intracranial aneurysm. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2003, 24, 559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Wuyts, F.L.; Vanhuyse, V.J.; Langewouters, G.J.; Decraemer, W.F.; Raman, E.R.; Buyle, S. Elastic properties of human aortas in relation to age and atherosclerosis: A structural model. Phys. Med. Biol. 1995, 40, 1577–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Medical Association Inc. Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects; WMA Gen Assem: Somerset West, South Africa, 2008; pp. 1–5. Available online: https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/medical-ethics/declaration-of-helsinki/doh-oct2004/?utm (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Cilla, M.; Casales, M.; Peña, E.; Martínez, M.A.; Malvé, M. A parametric model for studying the aorta hemodynamics by means of the computational fluid dynamics. J. Biomech. 2020, 103, 109691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.