Abstract

In this work, we study a generalised high-order nonlinear Schrödinger equation with time-dependent coefficients, embracing a wide range of physical influences. By employing the Darboux transformation, we construct explicit breather and rogue wave solutions, illustrating how the spectral parameter governs waveform transitions. In these dynamics, dispersion determines stability and symmetry, nonlinearity influences the peak amplitude and width, and third-order dispersion introduces asymmetry and drift in the wave profile. We have demonstrated that stabilization, destabilization and shifting of the centre of the localization, or drifting towards the soliton in space or even temporal directions, can be possible by manoeuvring the spectral parameter relating dispersion and nonlinearity in optical fibre. Manoeuvring the spectral parameter relates the dispersion and nonlinearity from 100 t to 0.1 t leads to the stabilization of the soliton by a notable decrease in the amplitude for two hundred folds. The results reveal that the inclusion of higher-order term functions as a control mechanism for managing instability and localisation in nonlinear optical fibre systems, offering promising prospects for future developments in nonlinear optics.

1. Introduction

In 1834, J. Scott Russell observed an unusual propagation of waves in the Union Canal in Scotland. This created a curiosity to experiment on this translation of waves and found that these waves are localized, stable, and persist without dissipation. The findings stunned the researchers due to their contrary, unexpected behaviours of waves in nonlinear media. In 1895, Russell mathematically proved, using the Korteweg–de Vries (KdV) equation, that the existence of such a unique shape-preserving wave translation occurs because of the balance between dispersion and nonlinearity. This self-reinforcement of its shape due to the balance between dispersion and nonlinearity opened the floodgates in nonlinear optics to perform lossless long-distance communication by means of solitons as optical signals [1,2].

The growing demand for nonlinear wave phenomena and their applications in optical fiber communication has led to the identification of several new classes of localized wave structures, including breathers and rogue waves. Breathers are characterized by periodic localization and oscillatory energy exchange, with different types arising from variations in their spatial and temporal localization properties. For instance, a breather that is temporally localized and spatially periodic is known as an Akhmediev breather [3], whereas its spatially localized and temporally periodic counterpart is referred to as a Kuznetsov breather [4]. In addition, extremely large and steep localized waves, commonly termed rogue waves, may also emerge in nonlinear dispersive systems [5]. From a mathematical perspective, these specialized wave structures can be derived from fundamental soliton solutions by tuning the spectral parameter that governs the balance between dispersion and nonlinearity [6].

In the early development of nonlinear wave theory, analytical approaches relied heavily on the integral properties of the governing model equations. Among these, the nonlinear Schrödinger Equation (NLSE) has remained central due to its broad applicability across diverse physical systems. Owing to its versatility, the NLSE serves as a foundational framework for investigating and characterizing a wide variety of localized wave structures. However, the demands of modern applications necessitate extending the classical NLSE to capture more complex dynamical features. These extensions often incorporate higher-order dispersion and related physical effects, which are introduced through time-independent or time-dependent coefficients representing dispersion, nonlinearity, and higher-order corrections. Phenomena such as third-order dispersion, self-steepening, and spatial or temporal inhomogeneities become particularly significant in scenarios involving ultrashort pulses or nonuniform media [7].

In addition to the classical developments, the single-component NLSE offers only limited flexibility for controlling soliton dynamics. This limitation naturally shifts attention toward two-component NLSEs, which more accurately describe the propagation of optical pulses in birefringent fibers and matter-wave solitons in Bose–Einstein condensates (BECs). For example, the persistence of solitons and the influence of external trapping potentials have been examined in ref. [8]. These studies collectively demonstrate that even small modifications to previously investigated NLSE-type models can open entirely new avenues of research. Motivated by this, we pursue a systematic investigation of earlier-mentioned effects, particularly dispersion and nonlinearity, by introducing free parameters that allow greater control over the underlying dynamics. To analytically capture such complex phenomena, it becomes necessary to employ a more general NLSE framework endowed with multiple free parameters that may depend on space, time, or both. Selecting a sufficiently general model with flexible parameters enables a realistic representation of key physical processes, while the use of robust analytical methods allows one to trace and characterize localized wave structures, thereby uncovering new dynamical behaviours. Generalized higher-order NLSE-type equations with time-dependent coefficients have been extensively studied [9], incorporating variations in dispersion, nonlinearity, and dissipative terms, and examining their influence on the resulting dynamics under appropriate constraints. Within this expanded framework, the search for exact and stable localized solutions remains the significant research direction [10,11,12,13,14]. Several powerful analytical tools exist for this purpose, including the inverse scattering method [15], Hirota’s bilinear method [16], gauge transformations [17], and the Darboux transformation (DT) [18]. Among these, the DT is particularly advantageous due to its systematic procedure for generating higher-order solitons from simple seed solutions. It is also capable of producing various special localized structures [19,20,21]. More importantly, the DT naturally incorporates the spectral parameter, providing a convenient mechanism for tuning dispersion and nonlinearity effects. This parameter tunability acts as a control switch, allowing transitions among different nonlinear wave states and allowing intentional reshaping/requirement of waveforms [7,22,23,24].

In light of the above developments, we investigate a generalized higher-order nonlinear Schrödinger (HNLS) equation with time-dependent coefficients that account for realistic physical effects, including variable dispersion, nonlinearity, and higher-order dispersive contributions such as third-order dispersion. Within this framework, we explore possible transitions between distinct localized states, for example, the conversion of a general breather into an Akhmediev breather, Ma breather and rogue wave. We further demonstrate that localized structures can be stabilized or destabilized by appropriately tuning the balance between dispersion and nonlinearity. Additionally, our analysis reveals that modulation of the dispersion parameter induces spatial drift in solitons, effectively providing a powerful mechanism for engineering nonlinear wave propagation. These findings are significant not only from a theoretical standpoint but also for practical applications, offering prospects for designing stable optical pulses, controlling extreme wave events in fluids and advancing the broader use of nonlinear wave phenomena across physics.

2. The Model: Higher-Order Nonlinear Schrödinger Equation

We study the following generalized HNLS equation that describes optical soliton propagation in advanced fibre systems [25,26]:

where is the complex wave envelope. The time-dependent coefficients represent key physical effects as follows: describes the second-order (group velocity) dispersion coefficient which governs the spreading of the wave packet and represents the Kerr nonlinearity coefficient responsible for self-phase modulation. The term accounts for third-order dispersion, which becomes significant for ultra-short pulses, whereas and describe the self-steepening and nonlinear dispersive effects, respectively, both of which influence waveform asymmetry and polarization dynamics.

In addition to these time-dependent coefficients, represents the spatial or temporal inhomogeneities (or an external potential) and characterizes gain or loss in the system (positive for amplification and negative for damping). The coefficients , , and relate to other parameters via:

where the dot denotes the time derivative. This equation captures the complex interplay of nonlinear, dispersive and dissipative effects in wave evolution, making it well-suited for describing nonlinear optics, water waves, BECs and plasma waves under varying physical conditions.

3. Lax Pair and Darboux Transformation

To apply the DT in Equation (1), the problem is reformulated as a linear system of equations for an auxiliary field, denoted as . The evolution of is governed by the following linear system [27]:

Here, and are referred to as the Lax pair matrices. These matrices are specifically designed so that the linear system aligns with Equation (1). The DT is then applied to this linear system, enabling the construction of new, nontrivial solutions. To introduce the DT, the auxiliary field is extended by incorporating a spectral parameter matrix , which contains constant eigenvalues . This, in turn, yields the following modified form of the original linear system:

and

where

with

Here, and are matrices that are functions of the solution to Equation (1) and its spatial derivatives. To satisfy both Equations (3) and (4), must satisfy the consistency condition , which leads to:

where denotes the commutator of and . Substituting the matrices and into Equation (5) yields Equation (1).

After deriving the matrices and , which is the most crucial and challenging part, we apply the DT to obtain the analytic solution. We solve Equation (1) by setting , where is the seed solution. This process is then iterated to produce a new solution, given by:

where is the updated matrix that contains the solution and , which allows the application of the DT method to generate exact solutions. Starting from a known simple seed solution (continuous wave, time-dependent phase) [28,29]. The DT constructs more complex localized wave solutions by incrementally modifying the wave function through an iterative process involving a free spectral parameter . This spectral parameter serves as a control variable that allows for continuous tuning of solutions among families of breathers and rogue waves. The DT method ensures that each generated wave solution remains an exact solution of the original equation, preserving integrability. Detailed constructions and the explicit form of the Lax pair matrices U, V are omitted here for brevity but are crucial for the implementation of DT.

4. Results and Discussion

This section devoted to the investigation of the generalised HNLS equation with time-dependent coefficients which reveals a wide spectrum of nonlinear wave dynamics governed by the interplay of dispersion, nonlinearity and higher-order effects. By employing the DT constructed from the derived Lax pair, several families of localized solutions have been analytically obtained, including general breathers, Akhmediev breathers, Ma breathers and Peregrine-type rogue waves. The resulting profiles clearly demonstrate how the modulation of the spectral parameter and the temporal dependence of the coefficients , , and determine the morphology, localisation and stability of the nonlinear structures. The analysis demonstrates that the dispersion coefficient primarily controls the spatiotemporal spreading and localisation width of the waveform, while the nonlinearity coefficient determines the peak intensity and the depth of amplitude modulation. The third-order dispersion term , on the other hand, introduces asymmetry and phase drift, resulting in observable spatial or temporal shifts of the soliton core without necessarily affecting its amplitude integrity.

Through systematic parameter tuning, the DT-generated solutions reveal smooth transformations between distinct nonlinear regimes, where gradual variation in induces continuous transitions from a generalised breather to Ma and Akhmediev-type breathers and ultimately to the rogue wave limit, characterised by extreme amplitude localisation. The Figures presented in this section capture these dynamical behaviours through contour, 3D, and temporal evolution plots, illustrating how localised energy can be stabilised or destabilised under appropriate parametric modulation. Furthermore, the role of nonautonomous coefficients highlights the intrinsic controllability of the HNLS system, where careful dispersion and nonlinearity management can effectively act as a stabilizing mechanism against modulation instability. This dynamic tunability establishes the present model as an effective analytical framework for designing controllable soliton and breather states in optical fibres and other nonlinear dispersive media, providing deeper physical insight into the mechanisms responsible for waveform evolution, stability switching, and energy localisation. All numerical simulations and graphical representations presented in this section were generated using Wolfram Mathematica.

4.1. Breather Solution

In this subsection, we derive explicit breather solutions to the generalized HNLS equation using the DT approach. Beginning with the Lax pair formalism, we select a nontrivial plane wave seed solution of the form: , which satisfies the background dynamics governed by the HNLS equation. The DT is then applied iteratively to generate higher-order, localized wave solutions, resulting in the following generalized breather form:

The functions , , , and encode the nonlinear and dispersive dynamics and are defined as:

with the auxiliary functions and constants given by:

where are constants. These analytical breather solutions exhibit diverse spatiotemporal dynamics depending on the spectral parameter , and the time-dependent coefficients and , which emphasizes the role of nonautonomous systems in shaping wave profiles [30].

The parameters and W are complex and intermediate auxiliary functions. These functions carry the complex spatiotemporal dependence (phase and amplitude modulation) imposed on the final solution by the variable coefficients and . Finally, the components of the eigenfunction vector (), denoted , are the explicit closed-form solutions obtained by solving the Lax pair. Their complex exponential forms are fundamental inputs required for constructing the DT matrix.

4.2. General Breather Regime

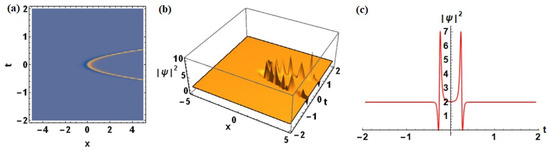

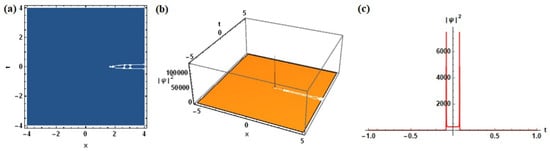

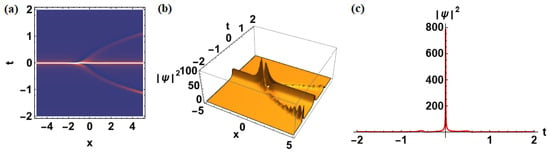

For generic values of and the parameters , and , the solution exhibits extended, smoothly varying breather dynamics. Figure 1 illustrates the surface profile of as a function of x and t. The temporal evolution at fixed spatial coordinate further confirms the parabolic amplitude modulation and zoomed views of the peak region reveal persistent regularity and stability.

Figure 1.

General breather profile for : (a) contour plot of the solution demonstrating an extended smoothly varying breather regime in the HNLS model, (b) 3D evolution of reveals the general breather profile and (c) temporal profile of at fixed x showing parabolic evolution.

An explicit instance simplifies to:

where are linear combinations of and x defined in detail in the text above, and . The functions are given by and This structure confirms the presence of temporal modulations and spatial localization under nonautonomous system parameters.

4.3. Spectral Control: Breather Transitions

By tuning the spectral parameter , and fixing the time-dependent coefficients as , , and , the solution exhibits transitions between different breather typologies.

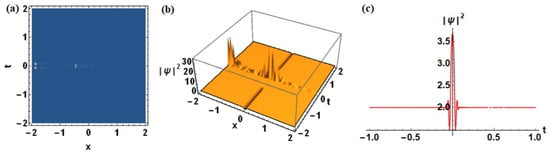

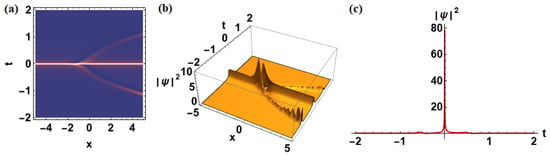

Figure 2 demonstrates the deformation from a broad general breather to a more spatially periodic Ma-type breather profile. As increases, the solution exhibits enhanced spatial periodicity together with stronger amplitude localization, providing an essential mechanism for engineering targeted nonlinear waveforms.

Figure 2.

Transition from general to Ma breather for : (a) contour plot of the solution, (b) 3D plot of shows how tuning the spectral parameter morphs the breather profile from a general state to Ma-type, with increasing spatial periodicity and amplitude localization and (c) temporal profile of at fixed x.

4.4. Akhmediev Breather Regime

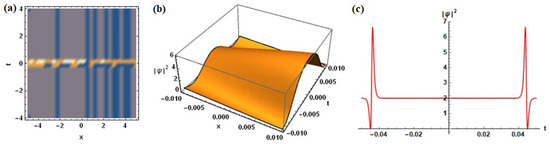

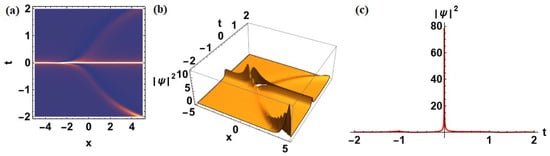

For , the solution morphs into the Akhmediev breather, exhibiting hallmark periodicity in x and pronounced localization in t. Figure 3 displays the 3D surface plot of , where maxima are periodically arranged and localized on the wave background. This regime is particularly relevant for fiber systems aiming at pulse shaping and control.

Figure 3.

Akhmediev breather for : (a) contour plot of the solution, (b) 3D evolution of reveals the hallmark periodic structure of the Akhmediev breather in space, with localized amplitude maxima and background modulation and (c) temporal profile of at fixed x.

4.5. Ma and Rogue Wave Breather

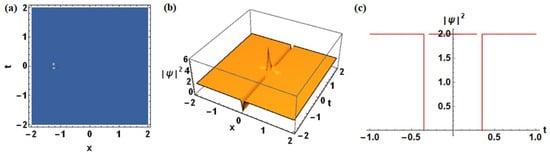

For (see Figure 4) the mixed regime emphasizes the sensibility of breather dynamics to spectral detuning, where small parameter range can trigger extreme localization events.

Figure 4.

Ma breather and rogue wave for : (a) depict the contour plot of the solution, (b) 3D evolution of reveals the hallmark periodic structure of the Ma and Rogue wave breather in space, with localized amplitude maxima and background modulation and (c) Temporal profile of at fixed x.

4.6. Rogue Wave (Peregrine Soliton)

Setting the spectral parameter to a critical value induces rogue wave (Peregrine soliton) solutions. These features are characterized by abrupt, highly localized amplitude peaks (see Figure 5). Such events correspond physically to extreme nonlinear phenomena, found in optical fibers, water waves and BECs, where sudden energy localization is of practical and fundamental interest [31,32,33]. The choice of various spectral and dispersion parameters for Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 has been summarized in Table 1 for better understanding.

Figure 5.

Rogue wave (Peregrine soliton) for : (a) depict the contour plot of the solution, (b) 3D plot of displays the sudden, steep amplitude peak of a rogue wave localized in both x and t, a defining characteristic of extreme nonlinear events in the HNLS model and (c) temporal profile of at fixed x.

4.7. Parameter Engineering: Dispersion and Nonlinearity Control

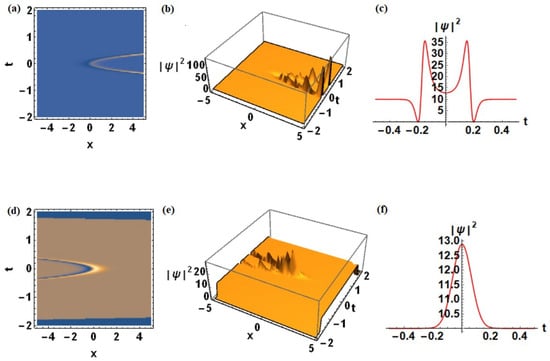

To clarify the physical interpretation of the parameters used in Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8, we summarize the roles of the time-dependent coefficients as follows. The term representing third-order dispersion controls the temporal drift and asymmetry of the breather, thereby enabling precise control of its trajectory. The coefficient associated with group velocity dispersion governs the balance between dispersion and nonlinearity and thus determines the degree of temporal or spatial compression and expansion of the wave. In contrast, the nonlinearity coefficient directly affects the peak amplitude and self-focusing intensity, enabling regulation of wave strength and suppression of instabilities. Since , and correspond, respectively, to measurable fiber parameters, group velocity dispersion (ps2/km), nonlinear coefficient (), and third order dispersion (ps3/km), their combined tuning offers a physically meaningful mechanism for controlling localization, trajectory and robustness of the nonlinear waves. This explains the variations observed across the Figures.

Figure 6.

Effect of time-dependent coefficients in the evolution of the breathers for the fixed spectral parameter for and the varying coefficients and : (a–c) and (d–f) .

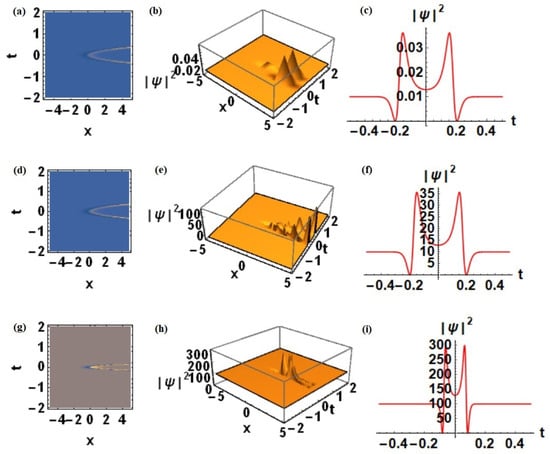

Figure 7.

Effect of time-dependent coefficient . For , and , the influence of is illustrated in the following cases: (a–c) , (d–f) and (g–i) .

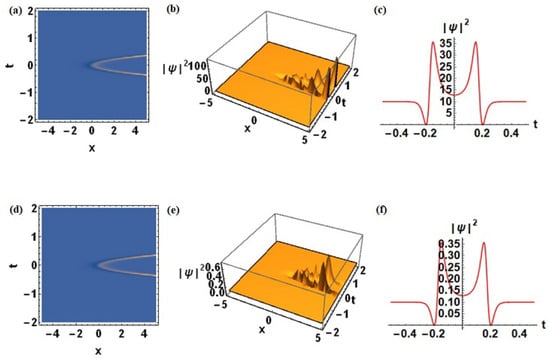

Figure 8.

Effect of time-dependent coefficient . For , the influence of is illustrated in the following cases: (a–c) and (d–f) .

In the following, we adjust the time-dependent coefficients while fixing the spectral parameter at .

From Figure 6, it can be observed that changing from to significantly reduces the degree of localization, as evidenced by a pronounced decrease in amplitude. This effect is clearly visible across the contour, 3D and 2D plots. The sign reversal of also induces a shift in the breather trajectory in the direction opposite to that seen in the previous case, demonstrating its strong influence on wave propagation. Furthermore, variations in introduce spatial drift and provide an effective mechanism for controlling the position of breathers or rogue waves without substantially altering their intrinsic shape.

Localization of solitons in optical media is achieved only when dispersion and nonlinearity remain in exact balance. By appropriately tuning the time-dependent coefficients and , we systematically investigate how these two fundamental physical mechanisms, dispersion and Kerr nonlinearity, govern soliton localization and stability. This balance is delicate, and even a slight perturbation to either parameter can disrupt localization and induce instability. Figure 7 and Figure 8 clearly illustrate the influence of these coefficients on soliton dynamics. The results demonstrate that soliton stabilization or destabilization can be theoretically engineered by adjusting the relative strengths of dispersion and nonlinearity. This provides a powerful framework for controlling nonlinear wave propagation in realistic optical settings. This behaviour becomes evident when comparing the soliton amplitudes in Figure 7 and Figure 8. The amplitude enhances sharply in Figure 7, comparing the rows (a–c), and (d–f) with (g–i) which indicates the onset of instability, whereas in Figure 8 the amplitude is noticeably reduced in the rows (a–c) to (d–f). By suitably tuning the time-dependent coefficients, it is possible to generate more stable and strongly nonlinear wave packets, thereby suppressing such instabilities.

4.8. One to One Effect of Time-Dependent Coefficients

In this subsection, we present a detailed interpretation of the results displayed in the Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, which illustrate the influence of different functional forms of the time-dependent coefficients , and on the spatiotemporal evolution of breather-type localized waves. These plots emphasize the crucial role of dispersion and nonlinearity management in stabilising or destabilising the nonlinear structures generated by the generalised HNLS equation.

Figure 9.

The time-dependent coefficients are chosen as , and , with all other parameters identical to those used in Figure 8, as illustrated in the contour plot (a), three-dimensional plot (b), and time profile for a fixed x (c).

Figure 10.

Effect of time-dependent on the already chosen and all other parameters as same as in Figure 9 as depicted by its contour plot (a), three-dimensional plot (b), and time profile for fixed x (c).

Figure 11.

Effect of time-dependent coefficient on the already chosen and and all other parameters as same as in Figure 10 as depicted by its contour plot (a), three-dimensional plot (b) and time profile for fixed x (c).

In Figure 9, the selected parameters , , and introduce a highly nonautonomous environment where dispersion grows exponentially in time while the nonlinearity evolves linearly. This combination leads to a gradual broadening of the localized pulse accompanied by a controlled reduction of its amplitude, indicating enhanced temporal stability and reduced intensity fluctuations. The hyperbolic dependence of effectively suppresses excessive modulation instability, resulting in a smoother energy distribution and stable wave confinement.

Figure 10 examines the effect of increasing the nonlinearity coefficient to while maintaining the same and as in Figure 9. The enhanced nonlinear contribution significantly amplifies the breather’s peak intensity and compresses its width, revealing the strong sensitivity of the localized amplitude to the nonlinear modulation strength. The corresponding contour and surface plots exhibit a noticeable increase in localization accompanied by a temporal narrowing, characteristic of energy focusing driven by nonlinearity. This suggests that the nonlinearity term directly governs the energy accumulation rate and the formation of strongly confined breather structures.

In Figure 11, the variation of the third-order dispersion coefficient to , with and fixed as in Figure 10, highlights the asymmetric deformation and drift of the breather envelope. The increase in introduces a discernible spatial shift of the localization center and modifies the temporal phase of the waveform without significantly altering its peak amplitude. Such a shift represents a physical manifestation of third-order dispersion–induced temporal drift, which is particularly relevant in the control of pulse propagation in optical fibers and ultrafast systems. Importantly, despite this drift, the waveform retains its structural integrity, emphasizing the robustness of the system against higher-order dispersive perturbations.

Overall, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 collectively confirm that dynamic manipulation of the time-dependent coefficients enables precise control over localization strength, stability, and trajectory of breather-type waves. The parametric evolution of , , and thus serves as an effective mechanism to engineer the desired nonlinear response—ranging from stabilization to drift control—demonstrating the feasibility of tailoring spatiotemporal soliton dynamics through dispersion and nonlinearity management.

Numerical Verification: Error and Spectral Analysis

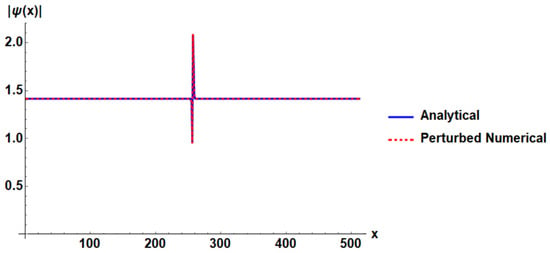

The stability of the analytical breather solution was verified by adding a small random perturbation () to the initial condition, resulting in . The relative error,

was found to be ∼6 × , confirming the high fidelity of the initial breather. Fast Fourier transformation-based spectral analysis further verified that the characteristic modes were preserved, with no spurious high-frequency components. Figure 12 shows the close agreement between the analytical and perturbed initial states, supporting reliable numerical propagation.

Figure 12.

Quantitative Comparison of the analytical breather solution (solid blue line) against the numerically computed profile with small initial perturbation (, dashed red line). The plot demonstrates the minimal deviation between the two profiles, confirming the accuracy and inherent stability of the analytical solution for subsequent numerical propagation. The error for this initial profile is .

4.9. Physical Insights and Applications

The results obtained through the analytical and graphical investigations presented in the preceding subsections highlight the deep physical implications of dispersion and nonlinearity management in nonautonomous higher-order nonlinear Schrödinger systems. The interplay between the time-dependent coefficients , , and representing dispersion, Kerr nonlinearity and third-order dispersion, respectively, serves as an effective control mechanism to tailor the characteristics of localized waveforms such as breathers, rogue waves and solitons. By varying these coefficients in a controlled fashion, one can modulate the amplitude, width, and spatial or temporal localization of nonlinear excitations, thereby achieving stable or intentionally destabilized propagation regimes.

From a physical standpoint, the coefficient governs the strength of group-velocity dispersion, which dictates the spreading and compression behavior of optical pulses. A gradual increase in , as observed in the simulations, leads to enhanced pulse broadening and reduced intensity peaks, corresponding to a stabilized propagation regime with minimal modulation instability. Conversely, a rapid modulation or sign change in can trigger focusing-type nonlinear behavior, resulting in localized wave collapse or strong temporal compression. The nonlinearity coefficient , in contrast, acts as a gain-like mechanism that amplifies the local field energy. The results in Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 clearly demonstrate that increasing enhances the amplitude of the breather while reducing its spatial extent, confirming that nonlinearity directly governs the degree of localization and energy concentration within the system.

The inclusion of the higher-order dispersion term provides additional degrees of freedom that introduce asymmetry, spectral broadening, and drift effects in the soliton envelope. Physically, this corresponds to third-order dispersion in optical fibers or higher-order kinetic corrections in Bose–Einstein condensates, which shift the peak of the soliton without significantly altering its amplitude. Such drift control is particularly advantageous in pulse engineering, where temporal synchronization and position control are crucial. In addition, the ability to switch the sign of reverses the direction of propagation drift, offering a dynamic mechanism for routing or phase-adjusting optical pulses within nonlinear media.

The smooth transition between different nonlinear regimes, ranging from general breathers to Akhmediev, Ma, and Peregrine rogue waves, illustrates how spectral tuning through the parameter can emulate the onset of modulation instability and the emergence of extreme events. This has practical significance in fiber optics, where rogue-like pulses can either be suppressed to maintain signal integrity or intentionally generated for high-intensity pulse amplification. The theoretical results hence provide a guiding framework for managing extreme events in physical systems such as supercontinuum generation, plasma oscillations, and wave turbulence, where similar localization–delocalization dynamics are observed.

Beyond optics, the findings have broader cross-disciplinary relevance. In Bose–Einstein condensates, where mean-field interactions play the role of the nonlinear term, temporal tuning of scattering lengths via Feshbach resonances can effectively reproduce the parameter variations described in this work. Similarly, in hydrodynamic or plasma environments, equivalent time-dependent control can be achieved through modulated external forcing or density gradients. Therefore, the analytical results obtained from the time-dependent HNLS model not only provide theoretical understanding but also offer an experimental roadmap for realizing tunable nonlinear states.

Overall, the present study demonstrates that nonautonomous management of dispersion, nonlinearity, and higher-order effects serves as a universal mechanism for controlling energy localization, waveform stability, and phase evolution across a wide range of nonlinear systems. The spectral parameter acts as a powerful tuning variable, while the time-dependent coefficients function as effective control switches to engineer the onset and suppression of instability. Such an integrated framework paves the way for robust, reconfigurable design of nonlinear optical systems, adaptive communication channels, and controlled wave propagation in diverse physical media.

5. Comparative Advantages of the Present Work

To highlight the contribution of the present study, we provide a direct comparison with our previous work [27] on the HNLS equation with constant coefficients, where the seed solution was set to zero and the resulting structures were solitonic in nature. In contrast, the current study investigates the same HNLS framework but under time-dependent coefficients, and employs a nonzero continuous-wave seed. This modification leads to fundamentally new dynamical behaviors and allows for the emergence of breather type localized structures. Table under summarizes the main differences between the two models with respect to integrability conditions, choice of seed, and the resulting analytical solutions:

| Term | HNLS with Constants Coefficients | HNLS with Time-Dependent Coefficients |

| Integrability | ||

| Seed | 0 | |

| Solution |

Where H and M are already defined. The present study extends the analytical framework of the HNLS equation by incorporating temporal variability in the coefficients and by employing a nonzero background seed. This combination leads to a more general class of solutions and reveals dynamical structures that are not accessible in the constant-coefficient model.

6. Conclusions

In this work, we conducted an analytical and parametric study of a generalized higher-order nonlinear Schrödinger (HNLS) equation with time-dependent dispersion, nonlinearity, and third-order dispersion terms. Using the Darboux transformation based on the constructed Lax pair, we derived explicit breather and rogue-wave solutions and examined their dynamics under nonautonomous conditions. The temporal modulation of the coefficients (dispersion), (nonlinearity) and the higher-order dispersion term enables control of localization, amplitude, and phase dynamics, allowing stabilization or destabilization of Breathers structures. The spectral parameter serves as a tuning variable governing smooth transitions among generalized, Ma, Akhmediev, and Peregrine-type rogue waves, while introduces asymmetry and controlled drift without affecting amplitude. The modulation of and manages amplitude and localization width, defining waveform stability. Stabilization or destabilization of Breathers structures.The robustness of the analytical results has been quantitatively substantiated by numerical analysis using the error norm. To move beyond qualitative observations and provide quantitative support for our claims of stabilization and destabilization, we performed a preliminary stability analysis using the numerical split-step Fourier method. We introduced small, low-amplitude disturbances to the analytical breather solution and monitored the evolution of the error norm. The robust fidelity of the analytical solution is confirmed by the very small initial error value, recorded at approximately . This metric establishes the high inherent stability of the derived breather solution against small perturbations. Crucially, the observed “destabilization” and “amplitude growth” discussed in the context of Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 are not due to inherent numerical instability but are rather a direct consequence of controlled, time-dependent variations in the coefficients , which successfully induce the targeted dynamic changes in the wave’s amplitude and trajectory, thus validating our management strategy quantitatively. Graphical analysis confirms that tuning these parameters governs localization, symmetry, and stability, highlighting their role as control switches in nonlinear dynamics. Overall, the study establishes that dispersion, nonlinearity, and higher-order effects act as efficient tools for managing soliton dynamics, regulating instability, and achieving controlled generation of extreme nonlinear events across optical, plasma, and condensate systems. The main constraints of this work arise from the restriction to integrable conditions and the exclusion of dissipative or stochastic effects that may occur in real physical media. Nevertheless, these constraints provide a foundation for future investigations aimed at extending the model to nonintegrable regimes, higher dimensions, and experimental validation. The prospects of this study include the application of time-dependent management strategies to design reconfigurable optical systems, control extreme events in nonlinear media, and guide future developments in ultrafast photonics and coherent matter-wave engineering.

Author Contributions

Z.T.: methodology, software, formal analysis; H.C.S.: formal analysis, validation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; M.Z.: formal analysis, writing—review and editing; P.S.: conceptualization, visualization, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, validation, resources, supervision; N.S.: formal analysis, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition, visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan, grant number AP19675202.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

M.Z. and N.S. would like to thank the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan, grant number AP19675202. The authors (Z.T. and H.C.S.) appreciate support from Hassiba Benbouali University of Chlef (Algeria), and P.S. wishes to thank PSG College of Arts and Science (India) and the management for the computational facility to demonstrate the analytical research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Hasegawa, A.; Kodama, Y. Solitons in Optical Communications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kodama, Y. Optical soliton in a monomode fiber: Transportation and propagation in nonlinear systems. J. Stat. Phys. 1985, 39, 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmediev, N.; Eleonskii, V.M.; Kulagin, N.E. Exact first-order solutions of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Theor. Math. Phys. 1987, 72, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, E.A. Solitons in a plasma. Sov. Phys. JETP 1976, 41, 164–169. [Google Scholar]

- Bludov, Y.V.; Konotop, V.V.; Akhmediev, N. Matter rogue waves. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 80, 033610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollenauer, L.F.; Stolen, R.H.; Gordon, J.P.; Tomlinson, W.J. Extreme picosecond pulse narrowing by means of soliton effect in single-mode optical fibers. Opt. Lett. 1983, 8, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samet, H.C.; Sakthivinayagam, P.; Al Khawaja, U.; Benarous, M.; Belkroukra, H. Peregrine soliton management of breathers in two coupled Gross–Pitaevskii equations with external potential. Phys. Wave Phenom. 2020, 28, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayagam, P.S.; Aravindha Krishnan, D.; Kamaleshwaran, R.V.; Radha, R. Collisional dynamics of solitons and pattern formation in an integrable cross coupled nonlinear Schrödinger equation with constant background. Rom. Rep. Phys. 2025, 77, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.-Q.; Gao, Y.-T.; Xue, L.; Wang, Q.-M. Nonautonomous solitons, breathers and rogue waves for the Gross–Pitaevskii equation in the Bose–Einstein condensate. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2016, 36, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serikbayev, N.; Saparbekova, A. Symmetry and conservation laws of the (2+1)-dimensional nonlinear Schrödinger-type equation. Int. J. Geom. Methods Mod. Phys. 2023, 20, 2350172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmediev, N.N.; Korneev, V.I. Modulation instability and periodic solutions of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Theor. Math. Phys. 1986, 69, 1089–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.-C. The perturbed plane-wave solutions of the cubic Schrödinger equation. Stud. Appl. Math. 1979, 60, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peregrine, D.H. Water waves, nonlinear Schrödinger equations and their solutions. J. Aust. Math. Soc. Ser. B 1983, 25, 16–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikhova, G.; Serikbayev, N.; Yesmakhanova, K.; Myrzakulov, R. Nonlocal complex modified Korteweg–de Vries equations: Reductions and exact solutions. Geom. Integr. Quantization 2020, 21, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablowitz, M.J.; Clarkson, P.A. Solitons, Nonlinear Evolution Equations and Inverse Scattering; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, R. Exact Solution of the Korteweg–de Vries Equation for Multiple Collisions of Solitons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1971, 27, 1192–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, V.E.; Shabat, A.B. Exact theory of two-dimensional self-focusing and one-dimensional self-modulation of waves in nonlinear media. Sov. Phys. JETP 1972, 34, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.H.; Porsezian, K.; He, J.S. Breather and rogue wave solutions of a generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 87, 053202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveev, V.B.; Salle, M.A. Darboux Transformations and Solitons; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Belkroukra, H.; Chachoua Samet, H.; Benarous, M. New families of breathers in trapped two-component condensates. Phys. Wave Phenom. 2022, 30, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikhova, G.N.; Kutum, B.B.; Syzdykova, A. Phase portraits and new exact traveling wave solutions of the (2+1)-dimensional Hirota system. Results Phys. 2023, 55, 107173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankiewicz, A.; Soto-Crespo, J.M.; Akhmediev, N. Rogue waves and rational solutions of the Hirota equation. Phys. Rev. E 2010, 81, 046602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Ling, L.; Liu, Q.P. Nonlinear Schrödinger equation: Generalized Darboux transformation and rogue wave solutions. Phys. Rev. E 2012, 85, 026607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesmakhanova, K.; Bekova, G.; Myrzakulov, R.; Shaikhova, G. Lax representation and soliton solutions for the (2+1)-dimensional two-component complex modified Korteweg–de Vries equations. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 804, 012004. [Google Scholar]

- Sasa, N.; Satsuma, J. New-type of soliton equations—An extension of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1991, 60, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YongHui, K.; Bolin, M.; Xin, W. Higher-order soliton solutions for the Sasa–Satsuma equation revisited via diference method. J. Nonlinear Math. Phys. 2023, 30, 1821–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samet, H.C.; Benarous, M.; Asad-uz-Zaman, M.; Al Khawaja, U. Effect of third-order dispersion on the solitonic solutions of the Schrödinger equations with cubic nonlinearity. Adv. Math. Phys. 2014, 2014, 323591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, V.F.; Polyanin, A.D. Handbook of Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Al Khawaja, U.; Al Sakkaf, L. Handbook of Exact Solutions to the Nonlinear Schrödinger Equations; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z. Nonautonomous “rogons” in the inhomogeneous nonlinear Schrödinger equation with variable coefficients. Phys. Lett. A 2010, 374, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solli, D.R.; Ropers, C.; Koonath, P.; Jalali, B. Optical rogue waves. Nature 2007, 450, 1054–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kibler, B.; Fatome, J.; Finot, C.; Millot, G.; Dias, F.; Genty, G.; Akhmediev, N.; Dudley, J.M. The Peregrine soliton in nonlinear fibre optics. Nat. Phys. 2010, 6, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, J.M.; Genty, G.; Eggleton, B.J. Harnessing and control of optical rogue waves in supercontinuum generation. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 3644–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).