Abstract

Indonesia’s reliance on fossil-based energy exports continuously shapes the dynamics of CO2 emission and the broader energy environment relationship across regions. This study applies a symmetric–asymmetric copula-based generalized linear mixed model (copula–GLMM) to examine the joint dependence between energy exports and CO2 emissions across 34 provinces from 2010 to 2024. The proposed framework captures both balanced and tail-specific dependence structures, providing a deeper understanding of the evolving dynamics shaped by industrial concentration, policy interventions, and technological adoption. The analysis reveals a strong positive association, with the Clayton copula offering the best fit. Notably, lower-tail dependence shows that provinces with smaller export volumes face disproportionate emission risks, whereas regions with larger exports exhibit more stable outcomes due to renewable integration and improved efficiency. These findings challenge the notion that export growth inevitably leads to proportional emission increases. The study underscores the need for region-specific strategies rather than uniform national policies to advance sustainability goals and support Indonesia’s commitments to SGDs 7, 11, and 13, as well as the Paris Agreement.

1. Introduction

This introduction aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the global and regional context of the energy–emissions nexus, with a particular focus on Indonesia’s position and challenges. It begins by outlining the global trends in greenhouse gas emissions and the persistent dependence on fossil fuels, followed by an examination of Southeast Asia’s growing energy demand and the implications for regional sustainability targets. The discussion then narrows to Indonesia, exploring its dual role as a major energy exporter and significant emitter and highlighting the substantial provincial disparities that shape its de-carbonization pathway. Finally, this section identifies key gaps in existing studies and introduces the rationale for employing a symmetric–asymmetric copula-based GLMM as a more robust framework to analyze complex dependencies between energy exports and CO2 emissions.

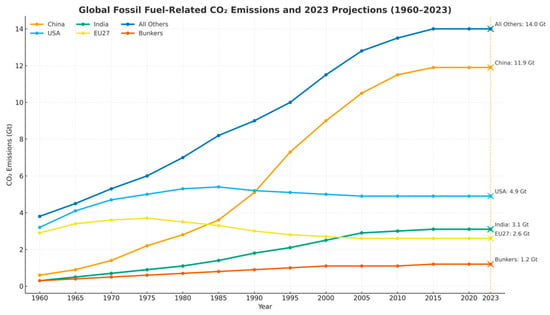

Climate change remains one of the most urgent global challenges of the twenty-first century, with energy-related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions at the center of the problem. According to [1], the energy sector accounts for nearly 73% of total global GHG emissions, primarily due to the combustion of fossil fuels for electricity generation, transportation, and industrial activities. As shown in Figure 1, global fossil fuel-related CO2 emissions have continued to rise over the past six decades, increasing from 9.5 gigatonnes (Gt) in 1960 to a record 37.4 Gt in 2023. This represents a 1.1% increase from the previous year and highlights the world’s ongoing reliance on fossil fuels, despite significant progress in renewable energy deployment and international climate initiatives. Emission patterns also show substantial variation. In 2023, China alone contributed 11.9 Gt (about 32% of global emissions), followed by the United States (4.9 Gt), India (3.1 Gt), and the European Union (2.6 Gt). These differences reveal the coexistence of symmetric patterns, where countries follow similar emission trajectories, and asymmetric patterns, where trends diverge significantly. Capturing such complex relationships requires advanced statistical approaches that can model both shared trends and divergent behaviors within the energy–emissions nexus.

Figure 1.

Global fossil fuel-related CO2 emissions and 2023 projections based on historical trends (1960–2023). Source: Global Carbon Project (2023).

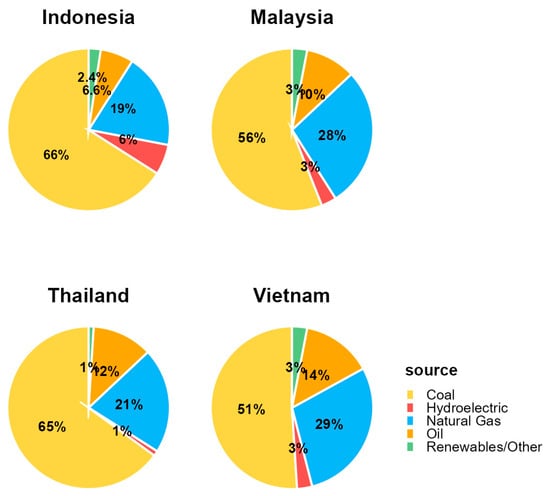

Southeast Asia provides a particularly clear example of these dynamics. Rapid industrialization, urbanization, and population growth have made it one of the fastest-growing energy markets in the world. However, fossil fuels still dominate the region’s electricity generation. As illustrated in Figure 2, coal and natural gas dominate electricity generation across Southeast Asia, accounting for 85% in Indonesia, 84% in Malaysia, 86% in Thailand, and 80% in Vietnam. Meanwhile, the share of renewable energy remains limited, with only 8.4% in Indonesia, 6% in Malaysia, 2% in Thailand, and 6% in Vietnam. This heavy reliance on fossil-based sources presents two major challenges. First, it threatens regional sustainability targets, as fossil fuel combustion contributes to more than 85% of Southeast Asia’s total CO2 emissions, undermining progress toward the Paris Agreement and Indonesia’s Net Zero Emissions (NZE) 2060 target. Second, it highlights persistent technological, policy, and financial barriers—such as the slow adoption of clean energy technologies and limited investment incentives—that hinder the region’s clean energy transition. These challenges show the need for region-specific strategies to diversify energy portfolios and emphasize the importance of analytical tools that can capture both symmetric and asymmetric interactions between energy exports and CO2 emissions.

Figure 2.

Electricity generation mix in selected Southeast Asian countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam). Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy (2023).

Within this regional context, Indonesia plays a crucial role. As Southeast Asia’s largest exporter of coal and liquefied natural gas (LNG), the country’s energy exports remain central to its economic growth and fiscal stability. However, this dependence also places Indonesia among the world’s top ten CO2 emitters, contributing approximately 2.1% of global emissions in 2022. Despite its commitment to achieving Net Zero Emissions (NZE) by 2060, current projections indicate that energy-related CO2 emissions could rise by around 35–40% by 2040 if existing fossil-fuel-dependent policies persist. This situation presents a major policy dilemma: how to sustain economic growth driven by energy exports while accelerating the transition toward a low-carbon energy system. Furthermore, substantial inter-provincial disparities in energy structure, industrial capacity, and policy implementation make this transition even more complex.

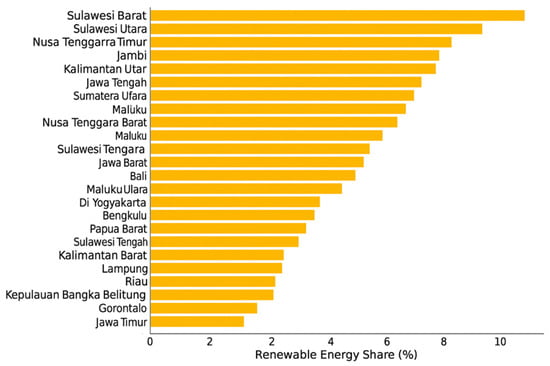

Variations in resource availability, economic structure, and local policies have produced highly diverse energy–emission profiles across the archipelago. For example, resource-rich provinces such as East Kalimantan generate large amounts of coal and LNG, which leads to higher emissions. Urbanized regions like Jakarta experience elevated emissions because of concentrated energy demand, while provinces such as Bali, which rely more heavily on renewable energy, show relatively low emission intensities. As shown in Figure 3, renewable energy shares vary widely between provinces. In Bali and East Nusa Tenggara, they exceed 30% due to geothermal and hydropower resources. In contrast, East Kalimantan and South Sumatra remain below 10%, and highly urbanized regions such as Jakarta and Banten record less than 5%. These disparities illustrate the coexistence of symmetric patterns among provinces with similar energy–emission characteristics and asymmetric cases with distinct dynamics, highlighting the need for robust models that can capture both.

Figure 3.

Interprovincial renewable energy share in Indonesia (2024).

Achieving Indonesia’s Net Zero Emissions (NZE) 2060 target is made more challenging by the large differences that exist between provinces in terms of energy production, consumption, and CO2 emissions. These variations are shaped by factors such as resource availability, economic structure, and local energy policies, leading to highly diverse energy–emission profiles across the country. For example, East Kalimantan, one of Indonesia’s main energy-producing regions, records substantial coal production and liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports [2]. This heavy reliance on fossil fuels directly contributes to higher CO2 emissions. In contrast, provinces with high energy demand, such as the Jakarta Capital Region (DKI Jakarta), show elevated emissions due to concentrated urban energy use and dependence on imported fossil fuels [1]. Meanwhile, provinces that prioritize renewable energy, such as Bali, tend to have much lower emission levels because of greater adoption of clean energy technologies and a tourism-based economy [3].

As shown in Figure 3, renewable energy shares differ widely across Indonesia. Provinces like Bali and East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) achieve shares above 30% thanks to significant geothermal and hydropower potential. By contrast, resource-rich regions such as East Kalimantan and South Sumatra remain below 10%, and highly urbanized areas such as Jakarta and Banten report adoption rates of less than 5%. These disparities demonstrate the coexistence of symmetric patterns among provinces with similar energy–emission characteristics and asymmetric cases where behaviors diverge significantly. Understanding these variations is crucial for designing effective de-carbonization strategies and highlights the need for advanced statistical models, such as the proposed symmetric–asymmetric copula-based GLMM, which can capture both common drivers and province-specific differences in the relationship between energy exports and CO2 emissions.

These findings highlight not only the diversity of Indonesia’s provincial energy–emission landscape but also the complexity of policy design that must accommodate such heterogeneity. Addressing these challenges is not only a matter of academic interest but also a strategic necessity. Without a precise understanding of how energy exports and emissions interact, including the nonlinear patterns and asymmetric behaviors that shape their relationship, policy interventions risk becoming too generic or poorly aligned with the realities faced by each province. As Indonesia enters a critical decade in its pursuit of the Net Zero Emissions (NZE) 2060 roadmap, the capacity to design differentiated and evidence-based policies becomes essential to balance continued economic growth with environmental responsibility. In this context, a more advanced analytical framework is not merely useful but truly indispensable.

Despite extensive research on the energy–emissions relationship, most existing studies rely on conventional approaches such as generalized linear models (GLM), generalized linear mixed models (GLMM), or vector autoregressive (VAR) methods. While these methods provide valuable insights, they often assume homogeneous relationships and fail to capture nonlinear dependence structures or tail-specific dynamics. For example, Ref. [4] examined the interaction between energy exports, oil prices, and CO2 emissions using a VAR model and found significant short- and long-term relationships. However, this approach cannot account for provincial heterogeneity and does not adequately represent the asymmetric nature of energy–emissions dependencies.

To address these limitations, this study proposes a symmetric–asymmetric copula-based generalized linear mixed model (copula–GLMM). This framework integrates a double-link structure that models mean effects and variance dynamics simultaneously while using copula functions to capture nonlinear and tail-dependent relationships. The approach makes it possible to identify groups of provinces that exhibit similar behaviors as well as outliers with unique patterns. The contributions of this study are threefold. Theoretically, it extends the conventional GLMM framework by incorporating copula-based dependence modeling. Empirically, it applies this framework to a comprehensive panel dataset covering 34 Indonesian provinces from 2010 to 2024. Practically, it provides evidence-based insights to support adaptive, region-specific energy transition strategies that align with Indonesia’s Net Zero Emissions (NZE) 2060 goals and global climate commitments.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the materials and methods, detailing the data sources, variables, and the overall modeling framework. It introduces the foundation of the generalized linear model (GLM), explains the double-link extension, and describes how copula functions are integrated within the GLMM structure. This section also elaborates on the parameter estimation procedures and the approach used to analyze tail dependence. Section 3 presents the main empirical results, including descriptive patterns, the identification of symmetric and asymmetric dependence structures, the outcomes of the copula-based estimation, and a series of robustness checks. Section 4 provides an in-depth discussion of the key findings, situates them within the context of the existing literature, and highlights their practical implications. Finally, Section 5 concludes the study by summarizing the essential insights and offering policy recommendations as well as potential directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the dataset, methodological framework, and estimation procedures used to analyze the joint dynamics of CO2 emissions and energy exports across Indonesia’s provinces. We begin by describing the data sources, variables, and preprocessing steps. We then present the modeling strategy, which builds on a double-link generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) enhanced with copula functions to capture nonlinear and tail-specific dependencies. Finally, we discuss the parameter estimation process based on the Inference Functions for Margins (IFM) and the criteria used for model selection and tail-dependence analysis.

2.1. Data Sources and Variables

This study employs a balanced panel dataset comprising 34 Indonesian provinces over the period 2010–2024 (15 years), resulting in a total of 510 province–year observations. The dataset was constructed by integrating multiple official sources, including BPS-Statistics Indonesia [5], the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM), and the World Bank CO2 Emission Database, ensuring reliability and representativeness across spatial and temporal dimensions. The chosen time span captures both pre- and post-energy-transition policy phases, allowing the analysis to reflect structural changes over time.

The dataset integrates energy, environmental, and socioeconomic indicators. The primary response variables are provincial CO2 emissions (Y1), measured in metric tons per year, and energy exports (Y2), expressed in terawatt-hours (TWh) or billion Indonesian rupiah (IDR). Explanatory variables include renewable energy share (RE_Share), GDP per capita (GDP_pc), urbanization rate (Urban), educational expenditure (Edu_Exp), infrastructure expenditure (Infra_Exp), and income inequality (Gini index). Descriptive statistics reveal significant heterogeneity: emissions range from 1.2 to 78.4 million tons, while energy exports show wide dispersion driven by resource endowments and policy interventions. This diversity motivates the use of mixed-effects modeling to capture both shared dynamics and province-specific variations.

By combining environmental and socioeconomic indicators, the dataset enables a nuanced examination of symmetric and asymmetric dependencies—where some provinces follow similar trajectories, while others diverge significantly due to differences in economic structure, policy focus, or renewable energy adoption.

2.2. Model Framework

To investigate how energy exports and CO2 emissions evolve across provinces, this section introduces the core analytical framework used in this study. The approach builds on a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) and extends it with copula functions to capture complex, nonlinear dependencies and variations that differ from one province to another. By doing so, the model provides a richer and more realistic picture of how energy and environmental dynamics interact in Indonesia.

Understanding how CO2 emissions and energy exports evolve together requires a model that accounts for both common patterns and regional heterogeneity. Classical regression approaches such as GLMs or standard GLMMs often assume homogeneous effects across regions, overlooking crucial interprovincial differences. To overcome these limitations, we propose a symmetric–asymmetric copula-based GLMM (copula–GLMM), which integrates copula functions into a mixed-effects framework. This enables the joint modeling of nonlinear dependencies between multiple responses, here, and , while capturing unobserved heterogeneity through random effects.

Symmetric dependencies describe scenarios where provinces respond similarly to policy or market changes, whereas asymmetric dependencies reflect divergent responses, often driven by structural or resource-based differences. The proposed model unites both perspectives into a single, flexible framework.

2.2.1. Generalized Linear Mixed Model

We begin by outlining the basic structure of the generalized linear mixed model, which serves as the foundation for our analysis. This framework is particularly useful because it allows us to examine both overall trends and the unique characteristics of each province, reflecting the diverse ways in which energy policies and economic factors influence emissions.

The foundation of our approach is the generalized linear mixed model (GLMM), which combines fixed effects (shared across all provinces) with random effects (province-specific deviations) [6]. The general form of the GLMM is expressed as

where is the link s the link function connecting the expected response to the linear predictor, is the matrix of fixed-effect covariates for province i at year t, represents the vector of fixed-effect coefficients, is the design matrix for random effects, denotes the vector of province-specific random effects.

GLMMs are particularly powerful when modeling hierarchical or panel data because they allow the intercepts (and, if specified, slopes) to vary across groups, in our case, the 34 Indonesian provinces. This flexibility is crucial when analyzing energy export and CO2 emission dynamics because provinces differ substantially in their energy profiles, renewable adoption, and socioeconomic structures.

In this study, the fixed effects () represent the average impact of predictors such as renewable energy share (RE_Share), GDP per capita, and urbanization rate on CO2 emissions and energy exports. Meanwhile, the random effects ( capture unobserved heterogeneity specific to each province, such as natural resource endowment, policy implementation efficiency, and industrial composition. By combining these two components, the GLMM framework provides a robust approach to understanding both common patterns and province-specific variations in Indonesia’s energy–emission system.

Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of GLMMs in energy and environmental research. For instance, Ref. [7] highlighted the model’s flexibility in handling clustered datasets, while [8] emphasized its suitability for capturing complex hierarchical structures. In comparative studies across countries, applying mixed-effects models to emissions-related data has been shown to yield more reliable results than standard GLMs. For instance, Ref. [9] demonstrated that a gamma-based GLMM provided a superior fit compared to GLMs when examining CO2-by-fuel variables from 169 countries.

In the context of this research, the GLMM forms the foundation of the proposed symmetric–asymmetric copula-based GLMM, where the model not only captures the effect of explanatory variables on energy exports and CO2 emissions but also serves as the basis for integrating copula functions to model nonlinear dependencies between these response variables. This integration allows us to move beyond the limitations of conventional GLMMs and provides a comprehensive framework to study both symmetric and asymmetric interprovincial dynamics.

2.2.2. Double-Link Extension

Because provinces vary widely in their energy systems and emission patterns, assuming constant variability across regions would oversimplify reality. To address this, we extend the standard GLMM by modeling both the mean and the variance simultaneously. This double-link approach provides deeper insights into how the drivers of emissions behave under different conditions and improves the reliability of the model’s estimates.

In conventional generalized linear mixed models (GLMM), the variance of the response variable is typically assumed to be a simple function of its mean, implying homoscedasticity across observations. However, in the context of Indonesia’s energy–emission dynamics, this assumption is often unrealistic because provinces differ significantly in energy production, renewable adoption, industrial structures, and policy implementation. These structural differences can lead to heteroscedasticity, where the variability of CO2 emissions or energy exports differs systematically across provinces.

To address this limitation, we extend the standard GLMM by introducing a double-link structure that models the mean and variance simultaneously. The extended framework is formulated as follows:

where is the primary link function relating the expected response to the predictors, is the secondary link function modeling the conditional variance , is the matrix of predictors for the mean model, is the matrix of predictors influencing the variance structure, and are the corresponding parameter vectors.

The double-link framework allows the variance to depend not only on the mean but also on specific covariates. In our study, the variance of CO2 emissions and energy exports may be influenced by factors such as renewable energy share (RE_Share), GDP per capita, and policy intervention dummies. For example, provinces like East Kalimantan with high fossil fuel production tend to exhibit larger fluctuations in emissions, while renewable-oriented provinces such as Bali have relatively stable variance patterns.

This extension is particularly relevant when analyzing symmetric and asymmetric dependencies across provinces. Provinces exhibiting symmetric responses share similar variance structures, while those showing asymmetric responses demonstrate distinct variance dynamics caused by differences in energy mix and socioeconomic conditions. By explicitly modeling the variance structure, the double-link GLMM improves parameter estimation, enhances inference reliability, and provides a stronger foundation for integrating the copula-based dependence modeling introduced in the next section.

Several studies have highlighted the advantages of modeling both mean and variance components in GLMMs. For instance, Ref. [10] showed that employing double-link structures can markedly enhance statistical inference in the presence of heteroscedasticity, providing a more flexible framework for modeling mean–variance relationships. Similarly, Ref. [11] extended GLMMs with variance modeling to better capture group-level heterogeneity.

2.2.3. Derivation of the Asymmetric–Symmetric Copula Construction

To explicitly capture both symmetric and asymmetric dependence structures in the energy–emission relationship, we start by defining the joint distribution of two marginal variables (CO2 emissions) and (energy exports) using a copula function as

where is the copula with dependence parameter then and are the marginal cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) [12].

The symmetric copula captures balanced co-movements across the joint distribution but often fails to reflect tail-specific sensitivities. To address this, we extend the formulation by introducing an asymmetric transformation function applied to the marginal components:

where allows different dependence intensities in the lower and upper tails. The joint density is then

and the corresponding joint probability density function (PDF) becomes

Finally, we integrate this joint structure into the random-effects GLMM framework:

The lower and upper tails exhibit different dependence intensities. This transformation retains the standard copula properties while enabling asymmetric tail modeling. Finally, the proposed asymmetric–symmetric copula-based GLMM integrates this joint structure into the random-effects framework:

where is the random-effects density. The resulting formulation provides a robust mathematical foundation for analyzing the joint dynamics of energy exports and CO2 emissions. By embedding asymmetric transformations within the copula–GLMM framework, the model is able to capture tail-specific co-movements while preserving the flexibility and interpretability required for empirical applications. This formulation also serves as a basis for the subsequent integration of copula functions and likelihood construction, which further enhance the model’s capacity to represent complex dependence structures.

2.2.4. Copula Integration and Likelihood Approximation

While GLMMs effectively model individual responses, they fall short in capturing dependence between them. Copulas resolve this by linking marginal distributions into a joint structure. Given the marginal CDFs , the joint conditional distribution is obtained via Sklar’s theorem [12,13,14]:

where is the copula with parameter controlling dependence strength and direction. The corresponding joint density is

This decomposition separates marginal behavior (GLMM) from dependence modeling (copula), enabling nuanced inference on how emissions and exports co-move under different policy or economic conditions.

2.2.5. Likelihood Formulation

For province-, the conditional log-likelihood is

and the marginal log-likelihood integrates out random effects:

where is the multivariate Gaussian density; and are GLMM parameters.

Because this integral lacks a closed-form solution, due to nonlinear copula dependence, double-link marginal estimation, and multidimensional random effects, we approximate it using Adaptive Gauss–Hermite Quadrature (AGHQ) for accuracy and Laplace approximation for computational efficiency when needed.

2.2.6. Adaptive Gauss–Hermite Quadrature (AGHQ)

Estimating the model requires integrating over random effects, a task that is rarely solvable analytically. Here, we use Adaptive Gauss–Hermite Quadrature, a numerical technique that adapts to the shape of the data and significantly improves the precision of our parameter estimates. The estimation of dependence structures in copula-based generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) becomes particularly challenging when extended to double-link formulations, where both the mean and variance components are modeled. Since the integration over random effects does not yield closed-form solutions, accurate numerical approximation of the marginal likelihood is essential.

Adaptive Gauss–Hermite Quadrature (AGHQ) provides a powerful tool in this context. Unlike fixed quadrature rules, AGHQ adapts nodes and weights according to the distribution of the integrand, which allows it to handle skewed or heterogeneous random effects more effectively. This flexibility is especially relevant for double-link copula–GLMMs, in which both nonlinear dependence and variance heterogeneity must be accounted for to achieve robust inference.

Korhonen, Nordhausen, and Taskinen (2024) [15] note in their review of generalized latent variable models that modern computational strategies increasingly rely on adaptive quadrature methods, with AGHQ standing out as one of the most accurate likelihood-based approaches for GLMM-type models. They emphasize that, compared to simpler approximations, AGHQ ensures more reliable inference when random effects are strongly non-Gaussian.

Similarly, Ref. [16], in a comparative study of Laplace approximation, penalized quasi-likelihood, and AGHQ for binary outcome data with sparse observations, reporting that AGHQ consistently produced less biased estimates and narrower confidence intervals. Their findings underline the advantage of AGHQ in settings where data sparsity complicates estimation, a situation frequently encountered in regional environmental applications.

Ref. [17] applied AGHQ in the context of multilevel parametric survival models with recurrent events and demonstrated that the method yields stable maximum likelihood estimates even under complex hierarchical dependence. They further argued that AGHQ allows researchers to integrate over random effects with high accuracy while retaining computational feasibility in large-scale applications.

Taken together, this body of evidence highlights the suitability of AGHQ as an estimation procedure in double-link extension copula–GLMMs. By combining the flexibility of copula functions with the precision of adaptive quadrature, the framework can achieve reliable parameter estimation in multivariate settings across environmental, biomedical, and economic research domains.

Step 1. Gaussian Quadrature Approximation

For a Gaussian integral,

where = Hermite polynomial roots, quadrature weights.

Step 2. Adaptive Centering at Posterior Mode

In copula–GLMM, the posterior of may be skewed due to strong tail dependence from asymmetric copulas. To improve accuracy, we re-center quadrature nodes around the posterior mode :

where denotes the Cholesky decomposition of the local posterior covariance matrix . Here, is a lower triangular matrix such that multiplying by its transpose reproduces the covariance matrix. This transformation rescales and rotates the standard quadrature nodes ensuring that they reflect the posterior distribution more accurately. This step significantly reduces integration error.

Step 3. AGHQ Likelihood Approximation

The marginal likelihood for province becomes

for most applications, or modes are sufficient.

2.2.7. Laplace Approximation

In some cases, a simpler and faster method is preferable for likelihood estimation. The Laplace approximation offers a practical alternative by balancing computational efficiency with reasonable accuracy. This subsection explains when and why this method is used and how it complements AGHQ within our modeling framework.

Estimating double-link copula–GLMMs presents significant computational challenges. By jointly modeling the mean and dispersion while incorporating cross-sectional dependence, the likelihood function becomes analytically intractable. The Laplace approximation addresses this issue by expanding the joint log-likelihood around the posterior mode of the random effects, providing a tractable marginal likelihood that retains essential curvature information while ensuring computational efficiency.

Previous studies highlight the continued importance of this approach. Ref. [18] demonstrated that embedding Laplace approximation within penalized likelihood frameworks yields stable inference across models with complex variance structures. Ref. [19] advanced this development through the Template Model Builder (TMB), where Laplace approximation is combined with sparse matrix computation and automatic differentiation, offering a scalable and accurate solution for high-dimensional random-effects models. Ref. [20] further illustrated the practical benefits of Laplace-based estimation within the GLMM–TMB framework, which successfully accommodates zero-inflated and extended GLMM families while maintaining efficiency. More recently, Ref. [21] applied Laplace approximation in longitudinal latent-trait models, confirming its capacity to provide reliable inference in contexts characterized by heterogeneity and complex dependence structures.

Together, these contributions demonstrate that Laplace approximation remains a reliable and versatile estimation method. Within double-link copula–GLMMs, it achieves a balance between computational scalability and inferential precision, making it particularly well-suited for applications in environmental, biomedical, and economic research where accurate modeling of dependence and dispersion is essential. For models with higher-dimensional random effects, Laplace approximation offers faster computation.

Step 1. Second-Order Expansion

Define

Expanding around the posterior mode ,

where is the negative Hessian.

Step 2. Laplace Approximation Formula

Laplace is computationally efficient, especially when symmetric dependencies dominate.

2.2.8. Choosing Between AGHQ and Laplace

In this study, we primarily adopt the Adaptive Gauss–Hermite Quadrature (AGHQ) method because the dimension of the random effects is relatively small (d = 2), involving only provincial and temporal random intercepts. AGHQ provides highly accurate likelihood approximations, which are particularly important when modeling tail-dependent copulas such as Gumbel and Clayton that capture asymmetric co-movements in extreme values. For these situations, accurate numerical integration is essential to correctly estimate the strength and direction of dependence. However, when the random-effects dimension becomes larger (d > 3) or when the joint dependence is expected to be symmetric and closer to Gaussian, the Laplace approximation serves as a computationally efficient alternative. In practice, we exploit AGHQ for its superior precision but remain flexible to switch to Laplace when modeling complexity requires a faster approach without sacrificing too much accuracy.

2.2.9. Relevance to Symmetric–Asymmetric Modeling

The choice of likelihood approximation plays a crucial role in uncovering the symmetric and asymmetric interprovincial dependencies underlying Indonesia’s energy–emission dynamics. In provinces where policy interventions produce relatively uniform impacts and responses to energy, shocks are broadly similar, symmetric dependencies dominate, and the Laplace approximation provides sufficiently accurate results with lower computational costs. Conversely, in provinces exhibiting highly divergent energy profiles—such as Bali, where a renewable-oriented energy mix drives lower emission volatility, and East Kalimantan, where coal and LNG production remain dominant—the energy–emission relationship is characterized by strong asymmetric tail dependencies. In such cases, the Adaptive Gauss–Hermite Quadrature (AGHQ) approach becomes essential to avoid biased parameter estimates and to capture the nonlinearities in dependence structures more accurately.

By integrating double-link GLMMs [22] for modeling heteroscedasticity marginal dynamics, copula-based dependence structures for capturing nonlinear associations, and adaptive likelihood approximation techniques for improved estimation accuracy, this study introduces a modeling framework capable of jointly identifying symmetric clusters and asymmetric outliers across Indonesian provinces. To the best of our knowledge, this methodological integration has not been previously applied in the context of Indonesia’s interprovincial energy–emission system. As such, this framework offers significant contributions by providing novel empirical insights into regional energy-export and CO2 emission dynamics and informing the design of province-specific policies for achieving Indonesia’s Net Zero Emissions (NZE) 2060 roadmap. The detailed R script used for the Copula-based GLMM estimation is provided in Appendix A.

2.3. Parameter Estimation

After defining the model, we turn to how its parameters are estimated. This section introduces the Inference Functions for Margins (IFM) approach, a two-step procedure that first estimates the marginal distributions and then the dependence structure. We also describe how different copula models are evaluated and compared to identify the best fit for our data. The parameters of the proposed symmetric–asymmetric copula-based generalized linear mixed model (copula–GLMM) are estimated using the Inference Functions for Margins (IFM) approach [23,24,25]. This two-stage estimation strategy is computationally efficient and statistically consistent, making it particularly suitable for high-dimensional panel data involving multiple responses and province-specific heterogeneity.

2.3.1. Inference Functions for Margins (IFM)

The IFM framework separates the estimation into two sequential stages:

Step 1. Marginal Parameter Estimation

The marginal dynamics of CO2 emissions and energy exports are estimated using the double-link GLMM as formulated in Section Copula Integration and Likelihood Approximation. This stage provides the fitted marginal cumulative distribution functions (CDFs):

where are the transformed pseudo-observations and are the estimated GLMM parameters.

Step 2. Copula Parameter Estimation

Given the estimated marginal CDFs, the copula dependence parameter θ is obtained by maximizing the copula log-likelihood:

where is the copula density function. This stage captures nonlinear symmetric and asymmetric dependencies between CO2 emissions and energy exports across provinces.

2.3.2. Copula Selection and Optimization

Choosing the right copula is crucial because it determines how well the model captures the relationship between energy exports and emissions. In this part, we explain the selection process, compare the strengths and limitations of different copula families, and introduce the statistical criteria and tail-dependence measures used to guide our decision.

To capture the dependence structure between energy exports (Y2) and CO2 emissions (Y1) more accurately, five copula families were evaluated based on their theoretical properties and suitability for modeling both symmetric and asymmetric dynamics. Each copula offers a distinct assumption regarding how the two variables co-move across varying levels of energy activity, enabling a more comprehensive representation of the energy–emissions nexus.

- The Gaussian copula assumes a symmetric dependence structure [26,27], where positive and negative co-movements between energy exports and CO2 emissions are proportionally balanced. This specification is most appropriate when the relationship between the variables remains stable across the distribution, making it suitable for contexts in which the energy–emissions link follows a linear and homogeneous pattern.

- The Student-t copula, while also designed to capture symmetric dependence [28,29], provides an additional advantage by accommodating heavier tails. This property allows the model to better represent joint fluctuations during periods of high volatility, making it particularly relevant when energy exports and emissions experience simultaneous surges or declines.

- The Clayton copula is used to capture lower-tail asymmetric dependence [30,31], where stronger associations are observed during simultaneous declines in energy exports and CO2 emissions. This feature makes it particularly useful for analyzing periods of reduced energy demand, economic slowdowns, or policy-driven restrictions, as it highlights the increased vulnerability of emissions to negative shocks.

- The Gumbel copula focuses on upper-tail asymmetric dependence [32,33] and is well-suited for scenarios where energy exports and CO2 emissions jointly reach exceptionally high levels. This copula is particularly relevant during phases of rapid industrial expansion or energy-intensive development, where significant increases in production lead to disproportionately large environmental impacts.

- Finally, the Frank copula is designed to model moderate symmetric dependence [34] and is flexible in capturing both positive and negative associations without emphasizing tail-specific behavior [29,35]. Its strength lies in representing smooth and monotonic relationships, making it applicable in contexts where energy exports and emissions evolve consistently without pronounced lower- or upper-tail dominance.

The optimal copula is determined through a comprehensive model selection procedure that integrates three complementary statistical criteria to ensure the best representation of the dependence structure between CO2 emissions and energy exports:

- (a)

- Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)

Measures the trade-off between goodness-of-fit and model complexity [36,37]:

AIC=−2ℓ + 2k

Here, ℓ is maximized log-likelihood and k is the number of parameters estimated. A lower AIC indicates a better balance between model fit and complexity. In simple terms, a lower AIC suggests that the model fits the data well without being unnecessarily complicated. AIC is particularly useful when comparing several competing models, as it tends to reward models that capture important patterns while remaining flexible enough to generalize beyond the current dataset.

- (b)

- Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)

Provides a more conservative penalization for model complexity [38]:

where n refers to the sample size. Like AIC, a smaller BIC indicates a better-fitting model, but BIC penalizes complexity more strongly. This means it often prefers simpler models that still capture the essential structure of the data. Such parsimony is valuable when the goal is to build models that remain stable and reliable when applied to new situations as an important consideration in studies that aim to inform long-term energy and environmental policy. Using both AIC and BIC together provides a more comprehensive and confident basis for selecting the most appropriate copula model for the analysis.

BIC= −2ℓ + k ln(n),

- (c)

- Vuong’s Likelihood Ratio Test

Used to discriminate between non-nested copula models [39,40]. The test statistic is computed as follows:

where is the pointwise log-likelihood ratio.

- > 1.96 → Model 1 significantly preferred.

- < −1.96 → Model 2 significantly preferred.

- Otherwise, both models perform equivalently.

2.3.3. Tail-Dependence Coefficients

To assess extreme co-movements between CO2 emissions and energy exports, we calculate the upper-tail and lower-tail dependence coefficients based on the fitted copula models. These measures quantify the probability that one variable takes an extreme value given that the other variable is also extreme. For a bivariate copula , the upper-tail dependence coefficient and lower-tail dependence coefficient are defined as follows [41]:

where and are the pseudo-observations derived from marginal CDFs; represents the joint cumulative probability at quantile q. Then, the interpretation is as follows:

- → strong co-movement in the upper tail (e.g., simultaneous extreme increases).

- → strong co-movement in the lower tail (e.g., simultaneous extreme declines).

- → weak dependence in the corresponding tail.

3. Results

This chapter presents the main findings of the study and builds a comprehensive picture of how energy exports and CO2 emissions are interconnected across Indonesia’s provinces. We begin by examining the descriptive characteristics of the data to understand their basic patterns and regional variations. This step provides essential context before moving on to more complex modeling.

The analysis then explores how these variables evolve over time and differ spatially across provinces, offering early clues about whether their relationship behaves in a straightforward, proportional way (symmetric) or in a more uneven, tail-driven manner (asymmetric). Once these preliminary patterns are established, we proceed with the core of the analysis—estimating a copula-based generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) that can capture both the common dynamics shared across provinces and the unique sensitivities that arise in specific regional contexts.

We further evaluate the robustness of the results by testing the model under different specifications and alternative scenarios, ensuring that the conclusions are consistent and reliable. Finally, we classify provinces based on their dependence patterns and discuss what these findings imply for designing targeted, region-specific energy and environmental policies.

By progressing from descriptive insights to advanced dependence modeling, this chapter aims to move beyond surface-level correlations and provide a deeper understanding of how energy exports and emissions interact—not only on average, but also at the extremes, where policy interventions often matter most.

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of Energy Exports and CO2 Emissions

Before moving into complex statistical modeling, it is important to first understand the story told by the data itself. Descriptive analysis provides the foundation for deeper exploration, offering an initial look at how energy exports, CO2 emissions, renewable energy penetration, economic activity, and urbanization evolve across Indonesia’s provinces over time. By exploring these basic patterns, we can observe how provinces differ from one another, where disparities are most pronounced, and how these differences might shape the broader energy–emissions relationship. This initial step is crucial because it reveals potential connections and anomalies that will later guide the interpretation of more advanced analytical results.

This section presents the empirical findings derived from a comprehensive panel dataset covering 34 Indonesian provinces from 2010 to 2024. The analysis aims to explore the dynamic interdependence between energy exports (EEX), CO2 emissions (CO2), renewable energy share (RE_Share), GDP per capita (GDP_pc), and urbanization rate (Urban). Before implementing the symmetric–asymmetric copula-based generalized linear mixed model (GLMM), we conducted an extensive exploratory data analysis to understand the underlying structure, distributional properties, and potential nonlinearity among the key variables. Table 1 reports the summary statistics of the primary variables, including measures of central tendency, variability, and shape distribution, providing the foundation for subsequent model estimations.

Table 1 summarizes the statistical characteristics of the key variables, highlighting significant cross-provincial heterogeneity during the 2010–2024 period. The mean level of CO2 emissions (Y1) is approximately 178 MtCO2, with values ranging from as low as 6.75 MtCO2 in low-industrialized regions to peaks exceeding 347 MtCO2 in highly urbanized provinces. The relatively high standard deviation (102.99) suggests strong regional disparities in carbon emissions, reflecting the influence of varying energy consumption patterns and industrial activities.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of main variables (2010–2024).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of main variables (2010–2024).

| Variable | Mean | Median | Std. Dev | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1: CO2 Emissions (MtCO2) | 178.11 | 183.90 | 102.99 | 6.75 | 347.57 | −0.04 | −1.26 |

| Y2: Energy Exports | 127.93 | 132.05 | 73.14 | 6.24 | 248.28 | −0.04 | −1.26 |

| RE_Share (%) | 6.01 | 6.03 | 1.95 | 1.00 | 13.71 | 0.23 | 0.15 |

| GDP_pc (IDR) | 50,004,890 | 49,670,600 | 9,821,399 | 23,031,133 | 81,377,485 | 0.20 | 0.11 |

| Urbanization (%) | 60.80 | 60.93 | 9.95 | 31.04 | 86.44 | −0.10 | −0.08 |

Similarly, energy exports (Y2), proxied by standardized energy production data, exhibit an average value of 127.93, ranging from 6.24 to 248.28, indicating pronounced differences in energy output across provinces. The parallel movement between CO2 emissions and energy exports suggests an underlying positive association, particularly in regions where export-oriented energy production dominates provincial economic structures. The skewness close to zero (−0.04) implies a nearly symmetric distribution, while the negative kurtosis (−1.26) indicates thinner tails, suggesting fewer extreme outliers in energy export activities compared to emissions.

The renewable energy share (RE_Share) displays a relatively low average of 6.01%, with substantial variability across provinces (1% to 13.71%). This pattern highlights the persistent dominance of fossil-based energy systems, reinforcing the need to evaluate asymmetric dependencies between renewable integration and emissions dynamics. The GDP per capita averages around IDR 50 million, spanning from IDR 23 million in less-developed provinces to over IDR 81 million in more industrialized regions, indicating significant income inequality within the panel. Finally, the urbanization rate averages 60.8%, ranging from 31.04% in rural areas to 86.44% in highly urbanized provinces, underscoring the role of demographic concentration as a potential driver of energy demand and emissions intensity.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate substantial heterogeneity across provinces, supporting the application of a symmetric–asymmetric copula-based GLMM to capture potential nonlinear and tail-dependent relationships between energy exports and CO2 emissions. The observed variability further justifies modeling country-specific random effects and testing for asymmetric tail dependence, particularly for high-energy-intensive regions.

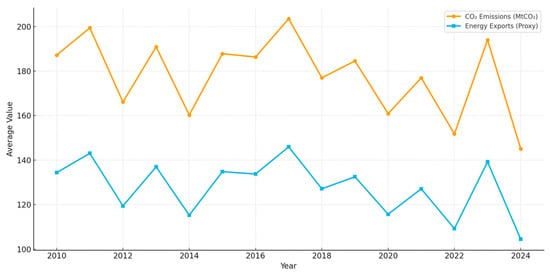

To gain preliminary insights into the dynamic interaction between energy exports and environmental outcomes, Figure 4 illustrates the temporal evolution of CO2 emissions and energy exports across all provinces from 2010 to 2024. The series are plotted using annual averages to capture the general direction of change while minimizing short-term fluctuations. This visualization provides an initial overview of the potential dependence structure between the two variables and serves as the foundation for the subsequent copula-based analysis.

Figure 4.

Temporal evolution of CO2 emissions and energy exports across Indonesian Provinces (2010–2024).

The observed trend reveals a close co-movement between CO2 emissions and energy exports over the 2010–2024 period, indicating a strong interdependence between the two variables. Both variables exhibit a gradual upward trajectory from 2010 until approximately 2018, reflecting the expansion of energy-intensive activities and the growth of export-oriented production. A significant decline is observed in 2020, coinciding with the global economic slowdown and reduced energy demand during the COVID-19 pandemic. Following 2021, there is a clear rebound in both energy exports and emissions, suggesting a recovery in industrial activities and international energy trade. Despite some year-to-year fluctuations, the parallel movement of the two series indicates a potential symmetric dependence during periods of moderate growth, while sharp export surges in specific years imply possible asymmetric effects on emissions. This dynamic supports the application of a copula-based GLMM in subsequent analyses to effectively capture both symmetric and tail-dependent relationships between energy exports and environmental consequences.

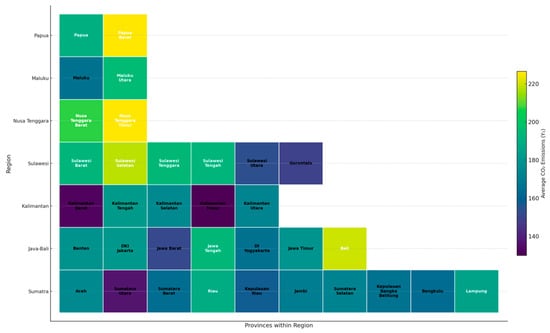

To further explore the cross-provincial heterogeneity in the relationship between CO2 emissions and energy exports, Figure 5 illustrates a heatmap of correlation coefficients computed across 34 Indonesian provinces for the period 2010–2024. The heatmap provides a visual perspective on the symmetry and asymmetry of the energy–emission nexus, offering initial evidence of regional dependence patterns.

Figure 5.

Heatmap of average CO2 emissions (Y1) across Indonesian Provinces, 2010–2024.

Figure 5 displays a heatmap illustrating the spatial distribution of average CO2 emissions (Y1) across 34 Indonesian provinces from 2010 to 2024. Darker shades correspond to provinces with relatively higher emission levels, while lighter tones indicate regions with lower carbon output. The visualization reveals notable interprovincial disparities, where provinces in Java-Bali, Papua, and certain parts of Sumatra consistently exhibit elevated emissions. These patterns are largely associated with intensive industrial activities, higher urban concentration, and energy-demanding production structures.

Conversely, provinces such as Nusa Tenggara Timur, Gorontalo, and Maluku Utara demonstrate lower average emissions, reflecting their smaller industrial bases and reduced reliance on fossil fuels. Interestingly, several provinces in Kalimantan and Sulawesi fall within an intermediate range, where moderate population density combined with resource-based extraction contributes to relatively high emissions despite smaller economic scales.

Overall, the heatmap highlights significant heterogeneity in carbon intensity across Indonesia, emphasizing the necessity of employing a copula-based GLMM framework in the subsequent analysis to effectively capture both symmetric and asymmetric dependence between energy exports and CO2 emissions.

Figure 6 presents the average levels of energy exports (Y2) across 34 Indonesian provinces over the period 2010–2024. Provinces such as Papua, Kalimantan Timur, Riau, and Aceh record consistently higher export volumes, largely driven by resource-based production and strong integration into international energy markets. In contrast, regions including DI Yogyakarta, Bali, and Nusa Tenggara Timur exhibit persistently lower energy exports, reflecting their limited fossil-based production capacity and smaller industrial structures. Meanwhile, several provinces in Sulawesi and Maluku occupy a moderate range, suggesting a balanced combination of domestic energy consumption and export-oriented production strategies.

Figure 6.

Average energy exports (Y2) across 34 Indonesian provinces by region, 2010–2024.

Overall, the heatmap reveals a highly heterogeneous spatial distribution of energy exports across Indonesia. When compared with Figure 5 on CO2 emissions, the observed divergence indicates potential symmetric dependence in resource-rich provinces where energy exports and emissions evolve in tandem, alongside possible asymmetric effects in low-export regions where variations in energy activity do not necessarily translate into proportional emission changes. These findings provide a strong rationale for employing a copula-based GLMM framework in Section 3.3 to capture the varying dependence structures between the two variables.

Furthermore, the descriptive analysis highlights significant interprovincial heterogeneity in both energy exports (Y2) and CO2 emissions (Y1) from 2010 to 2024. As shown in Figure 4, the aggregate trajectories of energy exports and emissions are closely aligned, reflecting Indonesia’s increasing reliance on energy-intensive activities over time. However, the heatmaps in Figure 5 and Figure 6 demonstrate that these patterns are far from uniform. Resource-abundant provinces such as Papua, Kalimantan Timur, and Riau consistently dominate in both energy exports and emissions, while regions such as Bali, DI Yogyakarta, and Nusa Tenggara Timur remain at the lower end of the spectrum.

These interprovincial variations underscore the complex dynamics shaping Indonesia’s energy–emission nexus. Differences in industrial structure, resource dependency, and urbanization patterns significantly influence environmental outcomes. This heterogeneity raises an important question: do shifts in energy activity lead to proportional changes in emissions across all provinces, or do certain regions exhibit heightened sensitivity to energy fluctuations? Addressing this question forms the analytical foundation for exploring potential symmetric and asymmetric dependence patterns, which are rigorously examined using a copula-based GLMM framework in the subsequent analysis.

3.2. Symmetric vs. Asymmetric Patterns in Energy–Emission Dynamics

While descriptive statistics offer valuable insight into the scale and distribution of energy use and emissions, they do not fully explain how these variables interact. The next step is to examine whether the relationship between energy exports and CO2 emissions is uniform across provinces or whether it varies depending on local conditions. In other words, do changes in energy activity always lead to proportional changes in emissions (a symmetric pattern), or do some provinces respond in a more complex and uneven way (an asymmetric pattern)? Exploring this question helps reveal the hidden dynamics of Indonesia’s energy–emission nexus and sets the stage for more sophisticated modeling approaches in the following sections.

Building on the observed heterogeneity in energy exports and CO2 emissions across provinces, a closer examination of their dependence structure becomes essential to understand Indonesia’s evolving energy–emission dynamics. While the overall trends suggest a positive relationship between energy activity and carbon output, the disparities revealed in the previous analysis indicate that this relationship may not be uniform across regions. In resource-rich provinces such as Papua, Kalimantan Timur, and Riau, energy exports and emissions appear to move in near-perfect synchrony, suggesting a symmetric pattern where changes in energy activity translate proportionally into emission levels. In contrast, provinces like Bali, DI Yogyakarta, and Nusa Tenggara Timur may exhibit asymmetric sensitivities, where small variations in energy activity could trigger disproportionately large or muted changes in emissions.

Understanding these potential differences is critical, as it determines whether policy interventions should be designed at the national level or tailored to specific regions. This motivates a deeper descriptive exploration of symmetric versus asymmetric patterns in energy–emission dynamics, which will serve as a conceptual bridge to the copula-based GLMM framework developed in the subsequent analysis.

3.2.1. Exploratory Analysis of Symmetric and Asymmetric Dependence

To better understand these dynamics, we begin with an exploratory analysis that investigates how provinces respond to changes in energy activity. This step focuses on identifying whether relationships remain stable across different levels of energy exports or whether sensitivities shift—for example, whether emissions react more strongly to small changes in energy activity in some regions than in others. Such exploration helps uncover the diversity of provincial responses and offers important clues about underlying structural differences, such as technology adoption, economic scale, or energy mix composition.

The relationship between energy exports (Y2) and CO2 emissions (Y1) demonstrates a clear positive association at the aggregate level; however, this overall trend conceals considerable heterogeneity across provinces. In resource-rich regions such as Riau, Kalimantan Timur, and Papua, variations in energy exports tend to correspond with proportionate changes in emissions, indicating the presence of symmetric dependence. In contrast, several low-export provinces reveal indications of asymmetric dynamics, where even modest fluctuations in energy exports may trigger disproportionately large changes in CO2 emissions, or conversely, where substantial export growth results in relatively limited emission responses.

These diverse patterns emphasize the need to examine the underlying dependence structures across provinces rather than relying exclusively on aggregate correlations. Such an approach provides a more nuanced understanding of regional dynamics and forms the conceptual basis for distinguishing provinces according to their symmetry and asymmetry patterns, which are further investigated in the subsequent section. These insights provide the foundation for selecting an appropriate copula-based GLMM in the subsequent analysis.

3.2.2. Provincial Classification Based on Tail/Slope Ratio

Building on these preliminary insights, we further classify provinces according to their dependence patterns using a tail–slope approach. This method allows us to determine whether provinces fall into symmetric categories, where responses remain proportional across the distribution, or asymmetric ones, where sensitivity differs significantly in the lower or upper extremes. This classification not only provides a clearer picture of Indonesia’s regional energy–emission landscape but also informs the development of targeted policy strategies tailored to each province’s unique dynamics.

The exploratory findings presented in the previous section indicate that the aggregate relationship between energy exports (Y2) and CO2 emissions (Y1) tends to mask substantial heterogeneity across Indonesian provinces. In resource-abundant regions, emissions generally respond in a stable and proportionate manner to changes in energy exports, suggesting relatively symmetric dynamics. In contrast, several other provinces display disproportionate sensitivities, where variations in energy exports are associated with nonlinear or amplified changes in CO2 emissions, indicating the potential presence of asymmetric patterns.

Recognizing these variations is crucial for distinguishing provinces where the energy–emission linkages are relatively consistent and symmetric from those where emissions exhibit nonlinear responses under different levels of energy activity. To capture these heterogeneous dependence structures, a tail–slope estimation approach is employed, allowing us to evaluate how the sensitivity of CO2 emissions (Y1) to energy exports (Y2) differs between lower and upper ranges of energy activity. This method involves three main steps:

- Estimating tail-specific slopes.

For each province, we calculate the slope of Y1 relative to Y2 separately for the lower quartile (Q1) and upper quartile (Q3):

- 2.

- Computing the slope ratio.

The slope ratio is obtained as

This ratio captures differences in emission sensitivities between the two tails.

- 3.

- Classifying provinces based on slope ratio.

Using the following criteria:

- Symmetric dependence: 0.80 ≤ ratio ≤ 1.25

- Upper-tail asymmetric: ratio > 1.25

- Lower-tail asymmetric: ratio < 0.80

This approach enables the identification of tail-dependent dynamics that conventional correlation measures might fail to capture, offering a more comprehensive understanding of provincial energy–emission linkages. To further examine the heterogeneous patterns observed across provinces, each region is classified based on the sensitivity of CO2 emissions (Y1) to variations in energy exports (Y2). Using the tail–slope estimation approach, the slopes corresponding to the lower quartile (Q1) and upper quartile (Q3) are compared to evaluate potential differences in emission responses at varying levels of energy activity. The resulting slope ratio serves as a straightforward yet effective indicator for determining whether the dependence between energy exports and emissions is symmetric or asymmetric.

Table 2 presents the classification outcomes for selected provinces. A slope ratio close to unity suggests symmetric dependence, indicating that changes in energy exports are associated with proportionate variations in CO2 emissions. Ratios substantially greater than one indicate upper-tail asymmetry, implying that emissions become more sensitive when energy exports reach higher levels. Conversely, ratios significantly below one represent lower-tail asymmetry, reflecting weaker emission responses even when energy exports increase substantially.

Table 2.

Classification of provinces based on tail–slope estimation and dependence patterns.

The classification presented in Table 2 shows substantial variation in the dependence structure between energy exports (Y2) and CO2 emissions (Y1) across Indonesian provinces. For most regions, the slope ratios are close to unity, indicating a symmetric dependence pattern in which changes in energy exports are associated with proportionate adjustments in CO2 emissions. This suggests that, for a large number of provinces, the environmental consequences of energy-export-related activities follow a relatively stable and predictable pathway, where emissions respond in a balanced manner to fluctuations in energy activity.

However, several provinces exhibit asymmetric dependence structures that deviate from the overall national trend. Upper-tail asymmetric provinces, such as Aceh and Sumatera Selatan, demonstrate heightened sensitivity of CO2 emissions at elevated export levels, where modest increases in energy exports result in disproportionately large rises in emissions. These findings indicate that these regions are particularly vulnerable to emission surges during periods of intensified energy activity.

Conversely, lower-tail asymmetric provinces, including Nusa Tenggara Timur and DI Yogyakarta, display weaker emissions responses despite substantial increases in energy exports. This pattern may be attributed to factors such as a higher reliance on low-emission energy sources, improved adoption of energy-efficient technologies, or structural characteristics that reduce the emission intensity of exported energy.

Taken together, these results highlight the heterogeneous nature of dependence patterns across Indonesian provinces and reinforce the need for flexible modeling frameworks. This provides strong motivation for employing a copula-based GLMM in the subsequent Section 3.3 to more accurately capture both symmetric and asymmetric tail dynamics.

3.3. Copula-Based GLMM Estimation

Once the nature of symmetric and asymmetric patterns has been established, the next step is to formally model these relationships using a more advanced statistical framework. The copula-based generalized linear mixed model (copula–GLMM) offers a powerful approach to simultaneously capture marginal behaviors and the dependence structure linking energy exports and CO2 emissions. This method allows us to move beyond simple correlations and directly measure how these variables interact under different conditions, including in the tails of the distribution where extreme behaviors often occur. The results from this modeling provide a deeper and more precise understanding of Indonesia’s energy–emission nexus.

The heterogeneous dependence patterns identified in the previous section demonstrate the need for a more flexible statistical framework to analyze the joint dynamics between energy exports (Y2) and CO2 emissions (Y1). Conventional linear models are often inadequate when the underlying relationships involve nonlinearities or tail-specific asymmetries, as observed across several provinces. To address these limitations, a copula-based generalized linear mixed model (copula–GLMM) is employed, which jointly models the marginal distribution of each variable and the dependence structure connecting them.

This modeling approach offers two main advantages. First, it enables a systematic comparison between symmetric and asymmetric copulas, providing statistical evidence on whether emission responses differ across varying levels of energy activity. Second, the inclusion of mixed-effects components captures province-specific heterogeneity, ensuring that regional disparities are properly represented in the model. Through this framework, the objective is to identify the most appropriate copula family and assess whether Indonesia’s energy–emission nexus is better described by a symmetric dependence structure or by asymmetric tail-dominant dynamics. Building on this framework, the next step involves comparing alternative copula families to determine which best captures the underlying dependence structure in Indonesia’s energy–emissions relationship

3.3.1. Model Selection and Goodness of Fit

To model the joint dependence between energy exports and CO2 emissions, five copula families—Clayton, Gumbel, Frank, Gaussian, and Student-t—were evaluated, each offering distinct features in capturing dependence structures. The Gumbel and Student-t copulas are more sensitive to upper-tail dependence, making them suitable for analyzing extreme co-movements when both variables reach high levels. The Frank copula assumes symmetric dependence across the distribution, while the Gaussian copula is based on linear correlation and does not capture tail dependence, which limits its explanatory power when nonlinear patterns exist.

The Clayton copula differs in that it specializes in modeling lower-tail dependence, capturing cases where both variables move together at lower levels—a pattern that closely reflects the empirical characteristics of our data. Many provinces display strong co-movement under low export and emission conditions, highlighting the structural realities of regions with limited energy production and smaller carbon footprints. This property makes Clayton particularly valuable for understanding asymmetric relationships that are often overlooked by symmetric or upper-tail-focused models.

Model comparison results further support this choice. Clayton consistently achieved the lowest AIC and BIC values and outperformed alternatives in likelihood ratio tests, indicating the best overall fit. Beyond statistical performance, its ability to capture asymmetric, lower-tail dynamics provides deeper and more policy-relevant insights into the energy–emissions nexus, making it the most appropriate copula for the proposed GLMM framework. The model evaluation is summarized in Table 3, which reports the log-likelihood values, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for each copula specification.

Table 3.

Model comparison for copula-based GLMM.

3.3.2. Copula Parameter Estimates

The estimation results from the Clayton copula–GLMM presented in Table 4 provide substantial empirical evidence on the dependence structure between energy exports (Y2) and CO2 emissions (Y1). The estimated copula parameter ψ = 2.317 (p < 0.001) indicates a strong and statistically significant association between the two variables. Translating this parameter into Kendall’s Tau yields τ ≈ 0.697, suggesting that the relationship between energy activity and emissions is highly concordant across provinces. Unlike symmetric copulas, the Clayton model captures a pronounced lower-tail dependence, meaning that the strongest co-movements between Y2 and Y1 occur when both variables are relatively low.

Table 4.

Parameter estimates for the best-fitting copula (Clayton copula–GLMM).

This result is particularly relevant for low-to-moderate export provinces, where small fluctuations in energy activity tend to produce disproportionately large changes in CO2 emissions. Such behavior is consistent with provinces in earlier stages of industrialization, where limited technological adaptation and less efficient energy systems exacerbate environmental impacts. In contrast, high-export provinces exhibit more proportional dynamics: emissions continue to rise alongside energy exports, but the marginal impact becomes more stable and predictable, reflecting technological improvements and investment in cleaner production infrastructure.

The estimated tail-dependence coefficients reinforce this conclusion. The lower-tail coefficient (0.482) indicates a relatively strong interdependence in regions with smaller export volumes, while the upper-tail coefficient (0.129) shows a weaker connection when both energy exports and emissions are high. This asymmetry suggests that carbon intensity is more sensitive to export shocks in low-activity environments, but becomes less elastic in high-export settings. These patterns may arise from technological advancements, higher energy efficiency, and the increasing role of renewable energy in more developed provinces.

Furthermore, the highly significant p-value (< 0.001) confirms the robustness of these findings, indicating that the observed asymmetric dependence reflects a genuine structural phenomenon rather than random variation. These results are also consistent with the heterogeneity identified earlier in Table 2, where several provinces exhibited divergent sensitivities to energy activity levels.

In summary, the Clayton copula–GLMM reveals that Indonesia’s energy–emission relationship is nonlinear and asymmetrically dependent, dominated by lower-tail sensitivity. Provinces with limited energy exports are more vulnerable to environmental pressures, as small increases in energy production or exports generate disproportionately high emission responses. Conversely, regions with more advanced export capacity display greater stability, benefiting from efficiency gains and cleaner production processes. These findings underscore the importance of adopting tail-sensitive modeling frameworks and support the formulation of targeted emission-control strategies, particularly for provinces in earlier stages of energy-intensive development.

3.3.3. Tail-Dependence Visualization

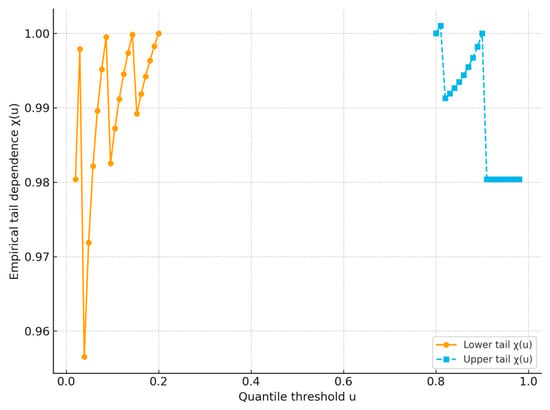

To gain deeper insights into the nature of symmetric and asymmetric dependence between CO2 emissions (Y1) and energy exports (Y2), we estimate the empirical tail-dependence functions, χ(u), for both the lower and upper tails of their joint distribution. This diagnostic assesses the probability that both variables simultaneously assume extreme low values (lower tail) or extreme high values (upper tail), thereby distinguishing whether the observed dependence structure is balanced or dominated by tail-specific effects. The patterns illustrated in Figure 7 provide visual confirmation of the model selection outcomes reported in Table 3 and the parameter estimates in Table 4, offering further evidence on whether CO2 emissions exhibit greater sensitivity at lower or higher levels of energy activity.

Figure 7.

Empirical tail-dependence functions for the joint distribution of CO2 emissions (Y1) and energy exports (Y2).

The empirical tail-dependence functions presented in Figure 7 provide visual confirmation of the asymmetric dependence between energy exports (Y2) and CO2 emissions (Y1). The estimated lower-tail function, , remains relatively high and stable across a wide range of thresholds, indicating that provinces with low-to-moderate energy export levels exhibit stronger co-movements between Y2 and Y1. This finding is consistent with the results reported in Table 4, where the Clayton copula was identified as the best-fitting model, reflecting pronounced lower-tail dominance in the dependence structure.

In contrast, the upper-tail function, , shows a gradual decline as u approaches extreme values, suggesting that the likelihood of simultaneously observing high energy exports and high CO2 emissions is comparatively weaker. This pattern implies that provinces with high export volumes are less prone to extreme emission spikes relative to energy activity, possibly due to improvements in energy efficiency, technological advancements, and a growing reliance on cleaner production processes in resource-rich regions.

Overall, the behavior of the tail-dependence functions strongly supports the selection of the Clayton copula and confirms that Indonesia’s energy–emission nexus is inherently nonlinear and asymmetric, with greater sensitivity observed at lower levels of energy activity. These results further validate the copula–GLMM estimation and provide a robust statistical basis for formulating targeted provincial-level emission mitigation strategies, particularly for regions with limited export capacity and higher vulnerability to environmental impacts.

The empirical evidence derived from model selection, parameter estimation, and tail-dependence diagnostics provides a comprehensive understanding of the interdependence between energy exports (Y2) and CO2 emissions (Y1) across Indonesian provinces. The comparative evaluation presented in Table 3 identifies the Clayton copula as the most suitable specification, indicating a clear lower-tail-dominant dependence structure. In practical terms, this suggests that the co-movement between energy activity and emissions is strongest when both variables are at low to moderate levels, whereas the degree of dependence weakens in the upper extremes.

The parameter estimates reported in Table 4 further reinforce these findings. The estimated copula parameter ψ = 2.317 (p < 0.001) and the corresponding Kendall’s Tau (τ ≈ 0.697) confirm a robust positive association between energy exports and CO2 emissions at the aggregate level. However, the lower-tail coefficient (0.482) is substantially larger than the upper-tail coefficient (0.129), indicating that emission sensitivity is disproportionately higher in low-export provinces. In these regions, even modest expansions in energy activity tend to result in disproportionately large increases in emissions, reflecting structural limitations such as restricted technological adaptation, limited renewable energy integration, and lower overall energy efficiency.

In contrast, provinces with high energy export levels demonstrate a more stable and predictable relationship between energy activity and emissions. This relatively subdued marginal response is consistent with the adoption of energy-efficient technologies, cleaner production processes, and a greater penetration of renewable sources in resource-rich regions, including Kalimantan Timur, Riau, and Papua. These insights are further supported by Figure 7, where the empirical tail-dependence curves clearly illustrate pronounced lower-tail dominance and a gradual decline in sensitivity at the upper extremes.

From an analytical perspective, these results suggest that asymmetry is conditional and localized rather than uniform across the distribution. While Indonesia’s energy–emission nexus exhibits a strong overall interdependence, the degree of sensitivity varies considerably depending on industrial structure, technological capability, and energy mix. Consequently, policy interventions should avoid a uniform, one-size-fits-all approach. Provinces situated in the lower tail—where emerging energy exports are accompanied by steep emission responses—would benefit most from initiatives aimed at improving energy efficiency, accelerating renewable integration, and implementing basic emission control technologies. Conversely, upper-tail provinces, where emission responses are less elastic, require more advanced strategies focused on technological innovation, fuel switching, and the deployment of sophisticated abatement mechanisms.

Finally, these findings highlight the effectiveness of adopting a copula-based GLMM framework. By jointly modeling marginal behaviors and the underlying dependence structure while accounting for unobserved provincial heterogeneity, the model successfully captures both the symmetric core of the energy–emission relationship and its tail-specific sensitivities. These insights establish a robust foundation for the subsequent section on robustness checks and policy implications, where the stability of these findings will be further examined and translated into actionable strategies to support Indonesia’s sustainable energy transition.

3.4. Robustness Checks