Abstract

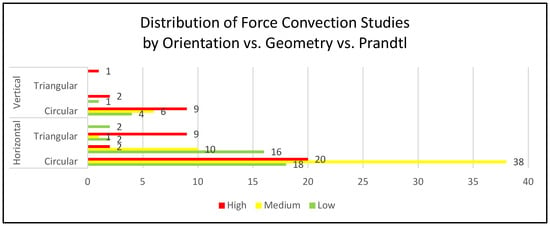

This paper presents a comprehensive review of forced convective heat-transfer phenomena in fluids, emphasizing the influence of fluid properties, tube geometries, and flow orientations under varying Prandtl numbers. Key governing parameters—including velocity, viscosity, thermal conductivity, density, specific heat, surface area, and flow regime (laminar or turbulent)—are expressed through dimensionless groups such as the Nusselt (Nu), Reynolds (Re), and Prandtl (Pr) numbers. The review encompasses heat-transfer characteristics of low-, medium-, and high-Prandtl-number fluids flowing through circular, square, triangular, and elliptical tubes in both horizontal and vertical orientations, aiming to critically evaluate the effectiveness and trends reported in previous studies. Where applicable, symmetry correlations—based on equivalent thermal and hydrodynamic behaviour along geometrically symmetric boundaries—were considered to interpret flow uniformity and heat-transfer distribution across cross-sectional profiles. Analysis reveals that over 84% of the reviewed studies emphasize on horizontal configurations and 55% on circular geometries, with medium-Prandtl-number fluids dominating experimental investigations. While these studies provide valuable insights, significant research gaps remain. Limited attention has been given to vertical orientations, where buoyancy effects may alter flow behaviour due to temperature and pressure gradients arising from variations in fluid density and viscosity, to non-circular geometries that enhance boundary-layer disruption, and to extreme-Prandtl-number fluids such as liquid metals and heavy oils, which are vital in advanced industrial applications. Bridging these gaps presents opportunities to design and optimize diverse engineering systems requiring efficient convective heat transfer. Practical examples include coolant flow in nuclear reactors, heat dissipation in high-performance CPUs, and high-speed airflow over automotive radiators. This review therefore underscores the need for future research extending forced-convection studies beyond conventional configurations, with particular emphasis on vertical orientations, complex geometries, and underexplored Prandtl-number regimes.

1. Introduction

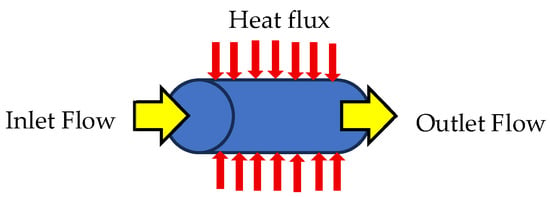

Primarily, when a temperature difference exists between two objects or regions, heat naturally transfers from the higher-temperature (warmer) body to the lower-temperature (cooler) one [1]. This phenomenon, known as thermal energy transfer, results in a change in the internal energy of both bodies. Internal energy is defined as the sum of all microscopic forms of energy associated with the intermolecular forces among the molecules within a system [2]. Heat can be transferred through the following three mechanisms: conduction, convection, and radiation and in this paper the focus will be on heat transfer by forced convection [3]. Forced convection occurs when an external force is applied to induce fluid motion, whether in gases or liquids, thereby enhancing heat transfer. Examples of such external forces include fans or pumps that circulate the fluid, promoting heat distribution by reducing the fluid’s density as it is heated, causing it to rise. In the absence of these external drivers, heat transfer occurs solely due to buoyancy effects, known as natural convection. Hence, the stronger the external driving forces, the more dominant the convective heat transfer.

These forces may originate from magnetic fields [4,5,6], electrohydrodynamic effects [7,8], acoustic excitation [9,10], or mechanical vibrations [11,12]. In situation where the convection reaches turbulent mode, an empirical formula of Dittus–Boelter correlation is applied for fully developed flow inside circular tube which relates the Nusselt number () to the Reynolds () and Prandtl () numbers, as expressed in Equation (1).

where

- Nu = Nusselt number

- Re = Reynolds number

- Pr = Prandtl number

- n = 0.4 for heating of the fluid (wall temperature > bulk temperature)

- n = 0.3 for cooling of the fluid (wall temperature < bulk temperature)

In certain situations, both natural and forced convection mechanisms coexist, forming what is referred to as mixed convection. Classically, as natural convection correlates Nu-Ra and forced convection embodied by Dittus–Boelter correlation, both correlations did not directly validate in mixed-convection regimes due to modification of velocity and thermal boundary layers caused by the buoyancy existence [13]. This scenario was studied by Amran M.F. et al. [14], who investigated the influence of Prandtl number, geometry, and orientation in mixed convection which commonly favour horizontal circular tubes due to high heat-transfer performance with minimal pumping power, especially at low Reynolds numbers. As mixed convection typically appears in the transition regime (1000 < Re < 4000 and 0.1 < Ri < 10), forced convection predominates when Re > 4000 and Ri < 0.1. Buoyancy starts to distort forced convection velocity profile when Ri is at moderate range between 0.21 and 1 and shifts to mixed convection.

Several investigators have preferred stationary circular cylinders, including Denis et al. [15], who observed that cylinder rotation led to a complex heat-transfer phenomenon in their numerical study of forced convection. Subsequently, Denis and Badr [16] conducted further investigations on the effect of rotational speed on heat transfer from circular cylinders and found that increasing the rotational speed resulted in a reduction in the overall heat-transfer rate. Badr later extended this work to mixed convection involving laminar flow from a horizontal cylinder in a cross-stream configuration [17]. The observed decrease in heat-transfer rate was attributed to disturbances in the thermal boundary-layer structure when the cylinder was in rotational motion compared to when it was stationary, as also discussed by Baugh and Saniei [18]. Moreover, Rashid A. Ahmad [19] numerically analyzed a similar case involving uniform heat flux in an air cross-flow over a horizontal stationary circular cylinder at laminar Reynolds numbers ranging from 100 to 500. In contrast, a non-circular duct including rectangular, square, triangular, and elliptical contain corners or edges that limit the thermal performance due to flow stagnation. Vinuesa R et al. [20] and Nikitin et al. [21] both carried out investigation on the scenario known as secondary flow of the second kind (turbulence-driven vortices) induced by anisotropic Reynolds stresses in turbulent flow. The thermal boundary layer at the corner is thinning and significantly increases local and overall heat transfer.

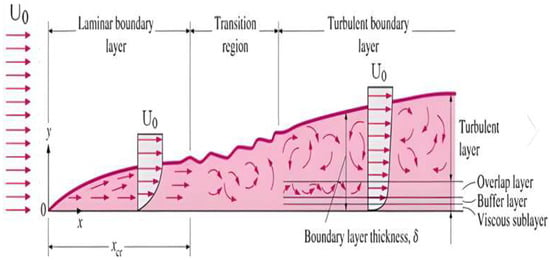

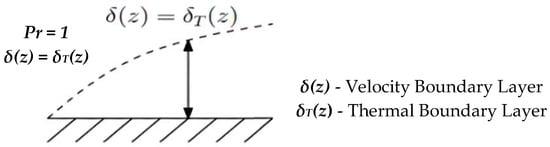

With regard to Prandtl numbers selection, the researchers have examined fluids with both very low and very high Pr values, each exhibiting distinct heat-transfer dynamics. Ludwig Prandtl, the originator of the Prandtl number, defined it as the ratio of momentum diffusivity to thermal diffusivity, representing the relationship between the hydrodynamic and thermal boundary-layer thicknesses [22]. This boundary layer represents the region adjacent to a solid surface where flow resistance occurs due to viscous effects, and its extent is characterized by its thickness (δ) measured from the wall surface [23]. As illustrated in Figure 1, the thickness of the boundary layer can be determined from the Fourier heat-conduction equation [24], as expressed in Equation (2).

where

- q = heat transferred per unit time (W)

- A = heat transfer area (m2)

- k = material thermal conductivity (W/m·K)

- TH = hot temperature (K)

- TC = cold temperature (K)

- δ = material thickness (m)

Figure 1.

Thickness of laminar and turbulent boundary layers [24].

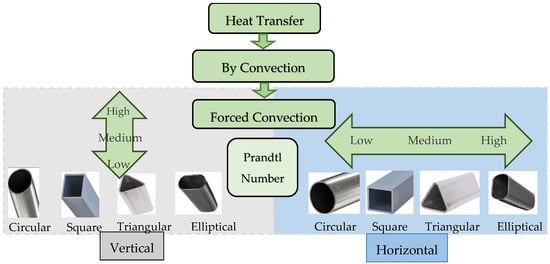

Therefore, the main objective of this paper is to consolidate previous research findings on the effectiveness of forced convection with respect to these three governing parameters (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary on Pr selection with its geometry setting for forced convection.

2. Low Prandtl Number

For low-Prandtl-number fluids (Pr < 1), thermal diffusivity dominates over momentum diffusivity because of the fluid’s relatively high thermal conductivity and low kinematic viscosity and specific heat [25]. Henceforth, the thermal conductivity is higher, as expressed in Equation (3).

where

- µf = fluid dynamic viscosity (kg/m·s)

- Cp = specific heat capacity (J/kg·K)

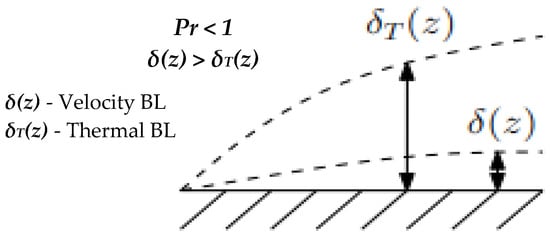

In simpler terms, in fluids with low Pr values, heat diffuses more rapidly than the velocity field develops, resulting in a thicker thermal boundary layer and a thinner velocity boundary layer, as illustrated in Figure 3. Most researchers have investigated heat transfer at low Prandtl numbers, typically around Pr = 0.7, which corresponds to gaseous fluids. Such fluids generally exhibit high thermal conductivity, high thermal capacity, low vapour pressure, and low melting points [26]. Furthermore, previous studies focusing on low-Prandtl-number heat transfer over circular-cylinder geometries are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Boundary layer of low Pr number fluid.

Table 1.

History of heat and fluid flow past a cylinder.

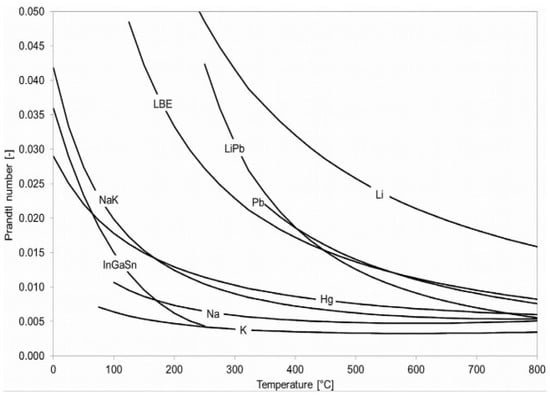

In addition to gases, several liquid metals are also classified as low-Prandtl-number fluids. Wadim Jaeger [36] conducted a comprehensive study on twelve such metals, including sodium (Na) [37], potassium (K) [37], sodium–potassium alloy (NaK) [37], mercury (Hg) [38], lead (Pb) [39], lead–bismuth alloy (PbBi) [40], lithium (Li) [41], lithium–lead alloy (LiPb) [42], and the indium–gallium–tin alloy (InGaSn) [43]. A comparative assessment of their thermal and flow characteristics was carried out, and the results are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of Pr vs. Temperature (°C) [38].

The thermal–hydraulic behaviour of these liquid metals was studied and validated using both empirical models and experimental data under turbulent forced-convection conditions. The investigations covered various geometries, including circular pipes, annular channels, rectangular ducts, parallel plates, and rod bundles. A comparative summary of the numerical and experimental results is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Theoretical Nu vs. Experimental Nu [38].

Overall, low-Prandtl-number fluids exhibit lower Nusselt numbers compared to high-Pr fluids, such as oils and water, because convection is limited by their thin thermal boundary layers. Regarding geometry, both circular and non-circular ducts influence boundary layer development, with non-circular ducts providing only a slight enhancement for low-Pr fluids. Among the fluids considered, sodium–potassium alloy (NaK) typically achieves the highest Nusselt numbers, whereas mercury (Hg) exhibits the lowest.

2.1. Low Prandtl Number—Square Horizontal Tube

Researchers have long investigated forced convective heat transfer around square cylinders or tubes, as it represents a classical problem in fluid mechanics due to the complex flow patterns that arise—particularly flow separation and vortex shedding near sharp edges. These phenomena have motivated numerous experimental and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) studies aimed at analyzing the local Nusselt number distributions along the cylinder surfaces, where the heat-transfer rate varies across different faces.

A.K. Dhiman et al. [44] elucidated the significance of the Prandtl number in determining heat transfer from a solid square cylinder under steady-flow conditions (see Table 3). To capture detailed variations in the local Nusselt numbers over the obstacle surfaces, the flow domain was modelled in a rectangular coordinate system.

Table 3.

Geometric configuration.

The findings revealed that, for square tubes, there exists a noticeable variation in the average Nusselt number on each face depending on both the Prandtl number (Pr) and Reynolds number (Re). In general, the average Nusselt number (Nu) increases progressively with increasing Re and Pr, thereby enhancing the overall heat-transfer rate.

Sharma and Eswaran [45] numerically investigated the heat-transfer characteristics of an isolated square cylinder under both steady and unsteady laminar flows for Pr = 0.7 and Re = 1–160 (two-dimensional regime). Geometrically, a square cylinder is bluffer compared to a circular one, leading to flow separation at the leading and trailing edges. Consequently, the square cylinder forms Kármán vortex streets that are significantly longer and broader, offering potential for enhanced heat and mass transfer between the cylinder surface and the surrounding fluid.

This phenomenon has drawn significant interest from other researchers seeking to further explore this fundamental fluid–thermal interaction from an engineering perspective. Zaki et al. [46] reported similar findings based on both numerical and experimental investigations of flow past a square cylinder at low and high Reynolds numbers, respectively. Sohankar et al. [47] extended these studies to Reynolds numbers in the range Re = 45–250, while in a subsequent work, Sohankar et al. [48] performed two- and three-dimensional unsteady flow simulations for Re = 150–500. Their results demonstrated the presence of stable vortex-shedding patterns at Re = 150 for 2D flow and at Re = 200 for 3D flow.

2.2. Low Prandtl Number—Circular/Sphere Horizontal Tube

For decades, numerous researchers have focused on the development of forced convective heat transfer using low-Prandtl-number working fluids in circular or spherical geometries. In as early as 1973, Dennis et al. [49] conducted a study to determine the heat transfer from an isothermal sphere subjected to a steady stream of viscous, incompressible flow. The numerically obtained Nusselt numbers were compared with experimental data at very low Reynolds and Prandtl numbers (Pr = 0.73), showing good agreement with the theoretical predictions of Rimmer [50]. However, as the Reynolds number increased, the results correlated well with the Whitaker correlation [51]. Research on low-Prandtl-number flows in circular and spherical enclosures has continued to the present day [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. Overall, circular geometries are dominated by thermal conduction, resulting from thick thermal boundary layers and relatively low Nusselt numbers, with minimal dependence on Reynolds and Prandtl numbers.

2.3. Low Prandtl Number—Rectangular Horizontal Tube

V. Botton et al. [62] conducted a numerical simulation of low-Prandtl-number convection using a 2.5-dimensional (2D½) model in a rectangular cavity with dimensions 10: 6: 1 (length/height/width). The use of the 2D½ model, rather than a purely two-dimensional (2D) approach, was motivated by the presence of temperature-field inaccuracies in 2D simulations, which failed to accurately capture the underlying flow physics.

The study referenced five 2D benchmark experiments, collectively known as the AFRODITE experiments [63,64,65,66], which employed a similar cavity configuration for validation. In summary, the results demonstrated that the 2D½ simulation provided superior agreement with experimental data compared to the 2D model. It offered improved temperature-field uniformity in the transverse direction, better prediction of the Grashof number (Gr) behaviour, shorter computational time, and lower uncertainty relative to experimental results. Similarly to the square geometry, the rectangular cavity also exhibited weak sensitivity to variations in Reynolds number (Re), Prandtl number (Pr), and aspect ratio.

2.4. Low Prandtl Number—Elliptical Horizontal Tube

The impact of using horizontally oriented elliptical tubes on heat transfer was thoroughly investigated by Hussein et al. [67]. The study involved a numerical evaluation comparing three different geometries—elliptical, circular, and flat tubes—as illustrated schematically in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic of investigation [65].

The findings from this study revealed that the elliptical tube achieved higher heat-transfer coefficient compared to the circular tube, when tested at the same length (500 mm) and hydraulic diameter (3 mm), as summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison by geometry and heat transfer coefficient between elliptical, circular, and flat cross-sectional area.

In conclusion, the elongated geometry resulted in non-uniform velocity and temperature distributions, as forced convection in this configuration was largely dominated by thermal conduction. Consequently, the overall heat-transfer performance remained low, since the Nusselt number (Nu) was strongly influenced by the Reynolds number (Re), Prandtl number (Pr), and the aspect ratio.

2.5. Low Prandtl Number—Applications

Forced convection with low-Prandtl-number fluids is inherently complex because temperature and flow fields are strongly coupled. The high thermal diffusivity of such fluids leads to a thin thermal boundary layer, as heat is rapidly conducted away. One of the most significant applications of this phenomenon is in nuclear reactors, particularly in liquid-metal-cooled systems where coolants such as liquid sodium or lead–bismuth alloys are employed.

E. Cascioli et al. [68] examined the influence of low-Prandtl-number fluids in strongly forced-convection flows within a central planar cold jet, applying a series of turbulent heat-transfer models. Their results showed that at elevated temperatures, these fluids promote highly efficient heat transfer. Several other studies have similarly explored turbulent convection in jet systems using low-Prandtl-number fluids, including the works of Chua L.P. et al. [69], Di Venuta et al. [70], Errico O. et al. [71], Fregni A. et al. [72], Grotzbach G. [73], and Kyas W.M. [74].

A critical aspect of this research area lies in understanding the fluid-thermal interactions that govern reactor-cooling performance. Beyond turbulence modelling, there remain opportunities for advancement through refined computational-fluid-dynamics (CFD) simulations and the development of predictive heat-transfer correlations, which can yield more accurate predictions of flow and temperature behaviour under real reactor operating conditions. Ultimately, achieving efficient and safe thermal management depends on integrating both fundamental physical understanding and modelling enhancements.

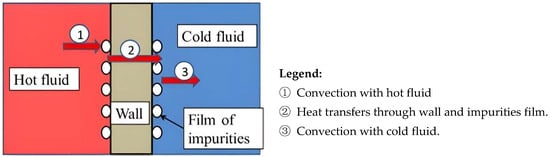

In the automotive industry, a persistent challenge is developing radiators that deliver equal or superior thermal performance while reducing size and manufacturing cost. An improved radiator refers to a heat exchanger capable of removing excess heat from the engine more rapidly and efficiently, facilitating effective heat transfer between two or more fluids without any coolant mixing, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Transfer of heat through wall [75].

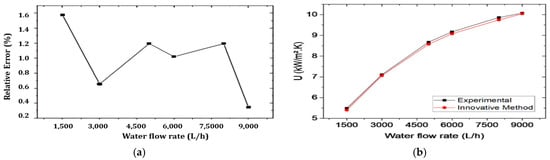

A. Faraj et al. [75] developed, simulated, and validated a new method to enhance heat exchanger performance by simultaneously measuring water and air flows under various operating conditions. The thermal performance was evaluated across sixty different combinations of air velocities and water flow rates. The procedure was deemed successful, showing very low relative errors—all below 1.6% (Figure 7a)—and minimal differences between the experimental results and the proposed innovative method for water flow rate predictions (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

(a): As the water flow rate increases, the relative error between the experimental data and the predicted values decreases, indicating that the model demonstrates higher accuracy at elevated Reynolds numbers [75]. (b): The overall heat-transfer coefficient (U) steadily increases with flow rate due to enhanced turbulence and improved convection. The innovative method shows strong agreement with the experimental results (relative error <1.5%), validating the reliability of the proposed approach [75].

In the modern world, the continuous depletion of Earth’s natural resources—including fossil fuels, oil, natural gas, and coal—has shifted global attention toward renewable energy sources, particularly solar energy. Photovoltaic (PV) panels have become an essential technology for electrical power generation. Typically, water is employed as a working fluid to remove excess heat generated by solar irradiation, which accumulates on the rear surface of PV modules. This fluid-based cooling helps to maintain optimal panel temperature and improve electrical efficiency.

I. Masalha et al. [76] successfully demonstrated this concept using porous media (gravel) with varying porosities and fluid flow rates. Without cooling, the maximum surface temperature reached 49.1 °C, which was reduced to 39.4 °C after implementing the technique. Similar PV cooling approaches have been explored by other researchers. S. Yogesh et al. [77] enhanced cooling efficiency through optimized fluid design, H. Alizadeh [78] used a single-turn pulsating heat pipe, S. Jakhar et al. [79] utilized an earth–water heat exchanger, I. Masalha et al. [80] and Z. Rostami et al. [81] applied nanofluids, while H. M. Bahaidarah [82] studied jet impingement cooling.

3. Medium Prandtl Number

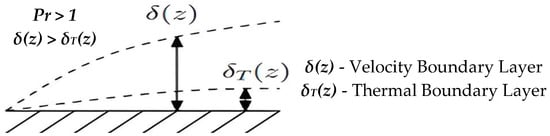

For medium-Prandtl-number fluids (Pr = 1), the momentum and thermal diffusivities are identical. In simpler terms, for fluids with Pr ≈ 1, heat diffuses at approximately the same rate as momentum, resulting in equal thicknesses of the thermal boundary layer δT(z) and the velocity boundary layer (δ(z)) as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Boundary layer of medium-Pr-number fluid [25].

3.1. Medium Prandtl Number—Circular/Sphere Horizontal Tube

In a horizontal circular tube, there is a balance of interaction between conduction and convection, characterized by moderately thick thermal boundary layers, distinct temperature gradients near the wall, and Nusselt numbers (Nu) that vary noticeably with both Reynolds (Re) and Prandtl (Pr) numbers. Buoyancy effects remain negligible at low Richardson numbers (Ri).

Nemati et al. [83] used direct numerical simulations (DNS) to investigate how the boundary layer affects fluid flow in a circular tube. Their work examined the interaction between the wall-adjacent thermal layer and the developing turbulent flow inside the tube. The DNS employed fluid properties corresponding to the inlet Reynolds (Re) and Prandtl (Pr) numbers of a supercritical fluid. The results showed that the thermal effusivity ratio strongly influences both the Nusselt number (Nu) and the skin-friction coefficient. Another significant study on medium-Prandtl-number forced convection in circular tubes was conducted by Jian Liu et al. [84], who confirmed the effectiveness of supercritical carbon dioxide (sCO2) as a regenerative cooling medium. Utilizing a circular tetrahedral lattice (CTL) structure, the sCO2-cooled channel achieved a 52.5% reduction in wall temperature compared to a smooth channel, highlighting the advantages of regenerative cooling in highly heated aerospace jet engine systems.

Similarly, Tu et al. [85] compared supercritical CO2 flow in microchannels of different cross-sectionals—circular, semicircular, rectangular, and trapezoidal. Their findings showed that the circular microchannel provided the highest heat-transfer coefficient, whereas the trapezoidal channel yielded the lowest, confirming the strong influence of geometry on thermal performance.

3.2. Medium Prandtl Number—Square Horizontal Tube

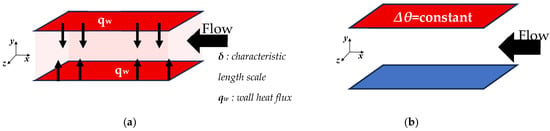

In horizontal square tube, Xingguang Zhou et al. [86] simulated turbulent heat-transfer mechanisms under constant wall temperature difference (CTD) conditions. Using OpenFOAM software, they aimed to obtain turbulent statistics and analyze the associated flow and thermal behaviours across medium Prandtl numbers ranging from 0.025 to 1.0 at a Reynolds number of 180. The simulation revealed distinct turbulent heat-transfer characteristics under both CTD and uniform heat flux (UHF) boundary conditions. The comparison of these two cases is illustrated in Figure 9a,b.

Figure 9.

(a): UHF—constant heat flux from the top and bottom. (b): CTD—consistent temperature difference (Δθ) from end to end.

At the same friction Reynolds number (ReT = 180), Kawamura et al. [87] performed direct numerical simulations (DNS) of turbulent heat transfer under uniform heat flux (UHF) conditions for a range of medium Prandtl numbers (0.025–0.71) to investigate the combined effects of Reynolds (Re) and Prandtl (Pr) numbers on flow and thermal behaviour. To date, a considerable number of DNS studies have been conducted on similar topics, including the works of Alcántara-Ávila and Hoyas [88], Abe and Antonia [89], and Priozzoli [90].

3.3. Medium Prandtl Number—Circular Vertical Tube

In circular vertical tube, one of the important applications is supercritical CO2 (sCO2), where flow through vertical channels is critical for the design of safe and efficient heat exchangers in sCO2 power cycles. At Pr range between 1 and 10, sCO2 exhibits strong coupling between turbulence and variable properties, especially near the wall regions. This incident generates positive and negative impact. On the positive note, a secondary flow of the second kind fabricating streamwise vortices enhances momentum and heat transport toward corners. In contrast, strong variations in temperature and pressure especially near the pseudocritical point cause heat transfer deterioration (HTD).

However, previous studies on convective heat transfer of sCO2 in vertical tubes at low mass flux have reported inconsistent results, indicating that the underlying mechanisms remain insufficiently understood. To address this gap, Li et al. [91] experimentally investigated sCO2 convective behaviour in a vertical tube, aiming to enhance heat transfer. They concluded that increasing mass flux, rather than heat flux, is the primary driver for improving convection under these conditions.

Wu et al. [92] further identified three stages characterizing vertical forced convection of sCO2:

- i.

- Deterioration stage—caused by flow laminarization,

- ii.

- Recovery stage—where buoyancy effects intensify and turbulence regenerates, and

- iii.

- Re-deterioration stage, based on DNS of downward-flowing sCO2.

Similar investigations have examined downward-flow sCO2 characteristics in various configurations, including microtubes at low Reynolds numbers (E. Oztabak et al. [93]), the cooling-transfer effects of buoyancy (Y. Lei et al. [94]), and thermal–hydraulic behaviour under both heating and cooling (J. Guo et al. [95]).

3.4. Medium Prandtl Number—Applications

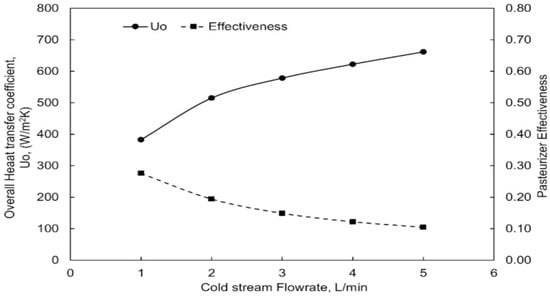

One of the significant modern applications of medium-Prandtl-number fluids is in pasteurization processes within the food industry. Pasteurization is primarily governed by convective heating, as conduction contributes only minimally. In such systems, temperature uniformity plays a crucial role—particularly in milk pasteurization and in solar-thermal collectors, which offer a sustainable alternative to traditional fossil-fuel-based thermal energy. At Pr of 2.605, S. K. Dabhi et al. [96] demonstrated the effectiveness of a convective pasteurizer, showing that increasing the flow rate in the cold stream significantly enhances the overall heat-transfer coefficient, as illustrated in Figure 10. Additionally, the integration of phase change materials (PCM) was shown to reduce temperature fluctuations, providing improved thermal stability, which is highly valuable for maintaining consistent pasteurization conditions.

Figure 10.

Effect of cold stream flow rate on overall heat transfer coefficient and effectiveness [96].

Additional research has also explored the application of medium-Prandtl-number fluids in pasteurization systems. Several studies have analyzed solar-assisted pasteurization, where solar energy serves as the primary heat source [97,98,99], while others have examined milk pasteurization using medium-Pr fluids under various thermal and flow conditions [100,101,102,103,104].

In the field of nuclear energy, the latest fourth-generation (Gen-IV) nuclear reactor systems require very high operating temperatures. These systems commonly employ medium-Prandtl-number working fluids, such as helium–xenon mixtures, lead, and sodium, which possess thermophysical properties suited to high-temperature heat transfer. Despite their relevance, conducting experiments on fast reactors involving these fluids is extremely challenging and costly, as highlighted by Schulenberg and Stieglitz [105], Wang [106], and Zhang et al. [107].

In overall, medium-Pr fluids exhibit moderate Nusselt numbers, higher than low-Pr fluids (liquid metals), because thermal transport is more efficiently coupled with momentum transport.

Unlike low-Pr fluids, geometry plays a more noticeable role as the non-circular ducts can enhance Nu more significantly and a turbulent water exhibits higher Nu compared to milk and ethylene glycol.

4. High Prandtl Number

For high-Prandtl-number fluids (Pr > 1), momentum diffusivity exceeds thermal diffusivity due to higher kinematic viscosity and specific heat. In practical terms, heat diffuses more slowly than the velocity field develops, producing a thin thermal boundary layer (δt) and a comparatively thick velocity boundary layer (δ) as illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Boundary layer of high-Pr-number fluid [25].

M. S. Arif et al. [108] further showed that high-Prandtl-number fluids exhibit lower temperatures, a behaviour linked to their inherently low thermal diffusivity.

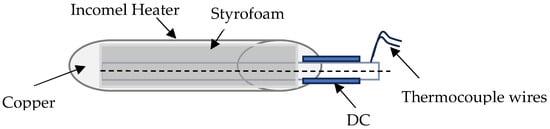

4.1. High Prandtl Number—Circular Horizontal Tube

Sanitjai and Goldstein [109] investigated the impact of forced convection on local heat transfer from a circular cylinder using water and water–ethylene glycol mixtures as working fluids. The Prandtl number in their experiments ranged from 7 to 176. Direct current was supplied through a thin in-line heater, providing uniform heating along the cylinder surface, as illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Test cylinder [109].

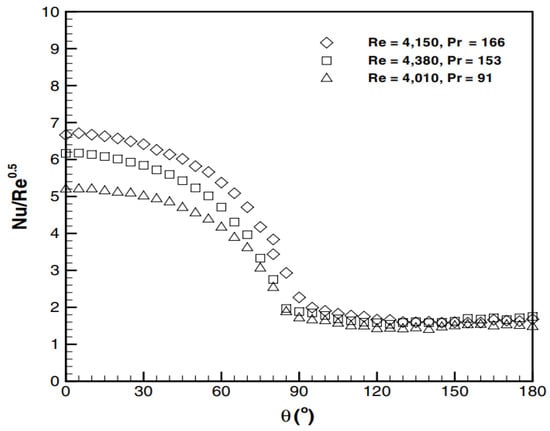

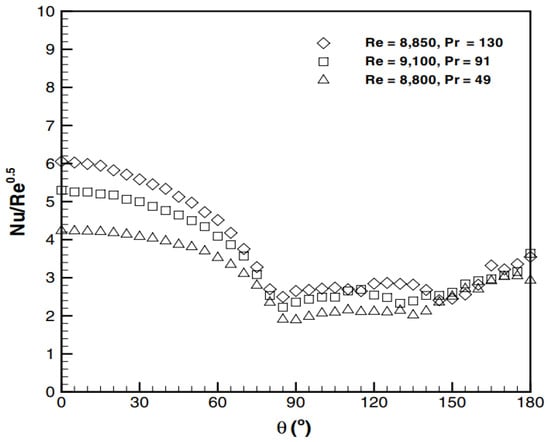

The investigation established a correlation between the local Nusselt number (Nu) and the Prandtl number (Pr). At Reynolds numbers (Re) of 4000 and 9000, the results showed that Nu increased with increasing Pr, as illustrated in Figure 13 and Figure 14.

Figure 13.

Distribution of local Nu at Re: 4 × 103 [109].

Figure 14.

Distribution of local Nu at Re: 9 × 103 [109].

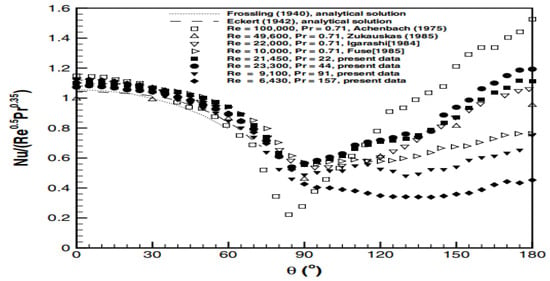

Furthermore, the obtained results were compared with previous studies, as shown in Figure 15 as it revealed a similar trend among the Nusselt, Prandtl, and Reynolds numbers [110,111,112,113,114,115].

Figure 15.

Comparison with other results [110,111,112,113,114,115].

Sarkar et al. [116] also investigated the correlation between Prandtl number and Richardson number. Using a circular horizontal tube, they examined forced convective flows and concluded that an increase in both Re and Pr leads to a corresponding increase in the local and average Nusselt numbers (Nu). In contrast, an increase in Ri results in a decrease in the average Nu [117].

Other studies examining the effect of high-Prandtl-number fluids in forced convection over circular horizontal tubes include those by Perkins and Leppert [118], Chang and Finlayson [119], and Sanitjai and Goldstein [120]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that forced convection of high-Prandtl-number fluids in horizontal circular tubes is primarily governed by convective mechanisms, characterized by thin thermal boundary layers, steep wall temperature gradients, and high Nusselt numbers that are strongly dependent on both Reynolds and Prandtl numbers. Moreover, buoyancy effects become increasingly significant at higher Richardson numbers.

4.2. High Prandtl Number—Circular Vertical Tube

In addition to studies on horizontal forced convection, several investigations have also focused on vertical flow configurations. For high-Prandtl-number fluids in a vertical circular tube, heat transfer is characterized by intense convection, thin thermal boundary layers, and high Nusselt numbers (Nu). The vertical orientation introduces buoyancy effects that may either assist or oppose the flow, depending on the direction of heating.

Rasheed et al. [121] conducted a critical investigation on a vertically stretched cylinder, examining the influence of Prandtl number (Pr) along with other dimensionless parameters such as the Grashof number (Gr), Hartmann number (Ha), Schmidt number (Sc), and Eckert number (Ec) on flow velocity, temperature, concentration, skin-friction coefficient, and Nusselt number. A related study by Biswas et al. [122] analyzed the effects of a magnetic field on forced convection over a vertically stretched plate, exploring the combined influence of magnetic field, thermal radiation, heat source, and viscous dissipation within the boundary layer.

4.3. High Prandtl Number—Applications

For fluids with high Prandtl numbers, momentum diffusivity exceeds thermal diffusivity, resulting in thinner thermal boundary layers and steeper temperature gradients near the surface. In forced convection, this enhances heat-transfer performance even when the fluid’s thermal conductivity is relatively low. Introducing external driving mechanisms such as blowers, pumps, or fans further strengthens convection, often promoting turbulent flow. One notable application is the packed bed system—a column-type reactor or container filled with solid materials through which fluids (liquids or gases) flow, as defined by Almusafir et al. [123].

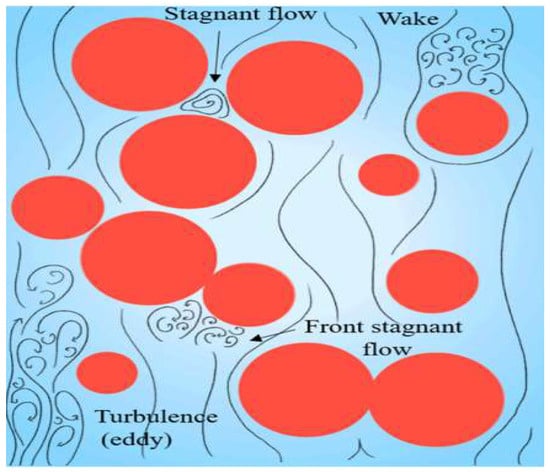

Packed beds are widely used in advanced nuclear reactors [124,125], thermal energy storage systems [126,127], catalytic reactors [128], and heat exchangers [129,130,131]. Within these systems, several physical and chemical phenomena occur simultaneously, including fluid flow through void spaces, heat transfer between the fluid and solid particles, dispersion effects due to mixing, chemical reactions at solid surfaces, and maldistribution caused by flow non-uniformity, as illustrated in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Flow characteristics in packed bed [132].

Park et al. [132] concluded that, to minimize adverse pressure gradients caused by stagnant flow, particular attention should be directed toward the geometric configuration of packed beds to help sustain turbulence. While traditional nuclear reactors employ fuel rods, the modern packed pebble-bed reactor (PBR) utilizes small spherical fuel elements (pebbles) to enhance coolant flow uniformity and thermal efficiency.

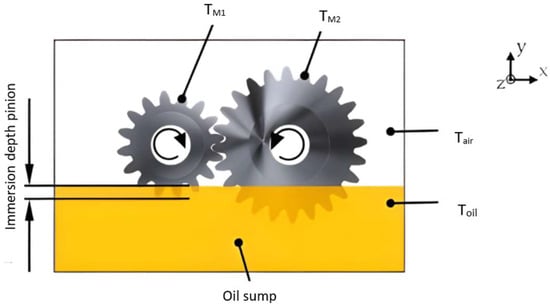

Another important application of high-Prandtl-number fluids is found in lubrication systems. Fluids such as oils, which exhibit Prandtl numbers ranging from 100 to 1000, can retain heat effectively due to their low thermal conductivity relative to momentum diffusivity. The resulting localized heat generation helps to stabilize the contact interfaces within the lubricant, a critical factor in maintaining lubrication performance. This thermal balance is particularly significant in automotive gearbox operations, where it directly affects fluid behaviour and efficiency. Hildebrand et al. [133] confirmed this interaction through numerical simulations of convective heat transfer between the rotating gears and lubricating fluid in a dip-lubricated gearbox, as illustrated in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Illustration of interaction between gearbox and oil in oil sump through immersion depth [133].

The investigation revealed that increasing oil viscosity and circumferential gear-rotation speed both lead to a higher heat-transfer coefficient. Additional research on thermal balance in gearboxes has been conducted by Becker [134], who examined rotating machine elements to predict gearbox power loss. These studies collectively underscore the importance of balanced heat transfer in any rotating gearbox or machinery where oil serves as the working fluid [135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142]. At a Prandtl number of approximately 0.2, gas-turbine systems exhibit propulsive flow characteristics. Mixtures such as helium–xenon (He–Xe) or hydrogen–xenon (H–Xe) generate low-Prandtl-number ranges (0.16 < Pr < 0.7). M. F. Taylor et al. [143] measured these mixtures in a vertical tube, correlating their behaviour with the Colburn analogy and Dittus–Boelter relation. B. Zhou et al. [144] further emphasized the turbulent behaviour of He–Xe, a critical property for accurately simulating convective heat transfer in propulsion systems.

The food and beverage industry also benefits from advancements in heat-transfer engineering, particularly in processes such as pasteurization, decrystallization, ultra-high-temperature (UHT) treatment, and cooking, all of which ensure product safety, shelf life, and quality. Modern lifestyles, characterized by limited meal-preparation time, have driven demand for ready-to-eat and quick-cook products. Many of these, such as tomato paste and chocolate, are high-viscosity, high-Prandtl-number fluids (Pr > 100). H. Sadia and M. Mustafa [145] further explored heat transfer in food processing, covering manufactured coatings, comestibles (e.g., cheese and mayonnaise), slurries (e.g., emulsions and paper pulp), and multiphase mixtures (e.g., oil–water ointments). G. Betta et al. [146] developed a rapid method for estimating thermal diffusivity, applied to various foods including tomato purée, sauces, bacon, and eggs.

In a nutshell, the ability of high Pr fluids to maintain stable thermal gradients remain to drive innovation in material and system design. Although their thermal diffusivity is low, its high viscous losses can dominate pressure drop in lubrication channels. Design compromises are needed including shorter ducts, lower flow rates, or enhanced cooling surfaces in order to manage pressure and temperature simultaneously.

5. Findings

The primary objective of this paper—to review and synthesize past and current research on forced convection across various geometries, orientations, and Prandtl-number ranges—has been successfully achieved. A consolidated summary of the key findings is presented in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Studies on forced convective heat transfer.

From Figure 18, it is evident that research activities were distributed almost equally—approximately 33% each—across the three Prandtl-number categories (high, medium, and low). Most studies were conducted under horizontal flow conditions (84%), and the circular tube geometry was the most frequently used (55%). Researchers commonly preferred horizontally aligned circular tubes because it is the simplest geometry for buoyancy—dominated flow topology. Without corners or sharp edges, the flow curvature is uniform entirely especially for low Pr fluids, which deduces a predictable heating distribution. This stability and predictability had prompted most researchers to proceed with measurements or DNS in studying the boundary layer interaction, DNS solvers, new turbulence model, and engineering correlations. In contrast, a non-circular duct had created vortices and re-circulations as the boundary layer thickness is mismatched along the adjacent walls.

With respect to the influence of Prandtl number across different geometries in forced convection, the circular profile remains the dominant choice in industrial applications such as general piping systems and heat exchangers. Beyond ease of manufacture, circular tubes offer a high strength-to-weight ratio and can withstand internal pressure uniformly in all directions. However, for specific engineering requirements—particularly where enhanced turbulence and higher heat-transfer rates are desired—alternative geometries such as rectangular or non-circular ducts are also employed, albeit with the trade-off of higher pressure drops. Additional findings and comparative observations are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Impact of geometries towards Prandtl numbers.

In addition, variations in geometry produce distinct effects on the Nusselt number (Nu) in forced convection, as summarized in Table 6:

Table 6.

Impact of geometries towards Nusselt numbers.

In terms of research methodology, two main approaches were identified: active and passive methods. In active methods, the rate of forced convection is enhanced through the application of an external force. Common active enhancement techniques include the use of magnetic fields [4,5,6], electrohydrodynamic (EHD) effects [7,8], acoustic excitation [9,10], and mechanical vibration [11,12].

In contrast, passive methods do not rely on external forces or power input. Instead, they enhance heat transfer by modifying fluid properties or surface characteristics. One passive approach involves altering the thermal conductivity of the working fluid, often through the use of nanoparticles, as demonstrated in several studies [147,148]. Another common strategy is to increase the effective heat-transfer surface area or promote flow disturbances, such as by flattening tubes [149] or inserting helical screw-tape elements [150]. Additionally, the heat-transfer surface can be specially engineered using twisted tapes [151], corrugated tube channels [152], or V-cut twisted tape inserts, with or without modifications [153].

6. Future Recommendations

Future research in forced convection is motivated by the global demand for improved thermal performance, energy efficiency, and sustainable engineering solutions. To advance the field, continuous development is required in the areas of fluid properties, geometry, and flow orientation. Area of improvement can be classified into two areas.

6.1. Fluid Properties, Geometry, and Orientation

- (a)

- Development of Turbulent Prandtl Number models for non-circular ducts in low-Pr flows.

- (b)

- Investigation of flow instability in vertical downward flows with high heat flux (opposing buoyancy).

- (c)

- Enhancing tube geometry and internal structures using roughened surfaces, twisted-tape and wire-coil inserts, and variable cross-sectional shapes to intensify turbulence and heat transfer.

- (d)

- Evaluating temperature-dependent variations in Pr, particularly under high thermal gradients encountered in combustion chambers, jet engines, and high-temperature reactors.

6.2. Advanced Physical Understanding and Experimental Needs

- (a)

- The potential of Machine Learning (ML) to derive universal correlations that cover the full spectrum of Pr numbers and geometries.

- (b)

- Exploring heat-transfer mechanisms in micro and nanoscale channels, where deviations from classical convection theory may arise due to entrance effects, wall roughness, rarefaction, and non-continuum behaviour.

- (c)

- Conducting experiments to validate MHD enhancements in high Pr vertical flows which are very much related to zero-carbon cooling systems. In turn, it is beneficial to these cooling technologies to reduce or eliminate CO2 emissions and this research promotes energy efficiency and innovation in sustainable thermal management, indirectly supporting SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure).

- (d)

- Conducting experiments with non-conventional fluids, including nanofluids, hybrid nanoparticles, and PCM-infused fluids, in addition to molten salts and traditional water–air systems.

- (e)

- Conducting in-depth studies on flow physics, especially in the transition regime, to address deficiencies in existing correlations and to better understand local heat-transfer augmentation.

- (f)

- Giving greater attention to two-phase and multiphase flow behaviour, which plays a crucial role in overall heat transfer performance. Multiphase flow patterns—such as stratified, slug, annular, and bubbly flows—are particularly important in systems with low velocities, high viscosity, or small hydraulic diameters.

- (g)

- Utilizing electric or magnetic fields to manipulate flow structures and enhance heat transfer, including techniques of electrohydrodynamics (EHD) and magnetohydrodynamics (MHD).

- (h)

- Advancing experimental measurement techniques to obtain high-resolution, time-resolved, and spatially detailed data on local Nusselt number distributions and temperature fields, enabling more accurate model development and validation.

7. Conclusions

This review investigated forced convection across a wide range of geometries, orientations, and Prandtl numbers. Among the various configurations, the circular horizontal tube consistently demonstrated superior performance, attributable to its uniform flow distribution, lower pressure drops, and favourable heat-transfer characteristics. While these findings strengthen our understanding of forced convection mechanisms, they also reveal a noticeable imbalance in the current research landscape. Several research limitations were identified:

- (i)

- Limited coverage of emerging working fluids—Most studies focus on conventional fluids such as water, oil, and air, with relatively few investigations on nanofluids, supercritical fluids, or liquid metals.

- (ii)

- Oversimplified geometries—Many works employ basic tube or duct shapes, whereas real industrial systems often involve complex or irregular geometries.

- (iii)

- Restricted flow orientations and conditions—Research predominantly examines horizontal or vertical flows under steady-state conditions, with limited attention to inclined, rotating, or pulsating flows.

- (iv)

- Modelling and simulation constraints—Numerous CFD studies rely on simplified laminar or ideal turbulence models, despite real systems exhibiting variable thermophysical properties, multiphase interactions, and transient behaviours.

- (v)

- Lack of experimental standardization—Differences in measurement techniques, boundary conditions, and data reporting complicate cross-study validation and model generalization.

In summary, addressing these research limitations opens pathways for innovation in engineering systems where convective cooling is essential. Potential applications include nuclear reactor safety systems, high-performance electronics cooling, and advanced automotive and aerospace heat exchangers. Future work should prioritize vertical-orientation studies, unconventional geometries, and underrepresented Prandtl-number regimes. Such efforts will help rebalance current research trends and contribute to the development of more efficient, robust, and sustainable thermal-management technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.S., M.F.A., and C.P.T.; methodology, S.M.S. and M.F.A.; software, S.M.S., M.F.A., and C.P.T.; validation, S.M.S. and M.F.A.; formal analysis, S.M.S., M.F.A., and C.P.T.; investigation, S.M.S. and M.F.A.; resources, S.M.S. and M.F.A. and C.P.T.; data curation, S.M.S. and M.F.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.S., M.F.A., and C.P.T.; writing—review and editing, S.M.S. and M.F.A.; visualization, S.M.S. and M.F.A.; supervision, S.M.S.; project administration, S.M.S.; funding acquisition, C.P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE), Malaysia, through the Fundamental Research Grants Scheme under the grant number FRGS/1/2023/TK08/UKM/02/1.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclatures

| A | Area | Greek letters | |

| BL | Boundary layer | ||

| C | coefficient used in correlations | B | thermal expansion coefficient |

| Cp | constant-pressure specific heat | ϵ | surface roughness |

| CWT | constant wall temperature | μ | dynamic viscosity |

| DNS | Direct Numerical Simulation | μ f | fluid dynamic viscosity |

| Di | inner diameter | v | kinematic viscosity |

| Do | outer diameter | ρ | Density |

| EB | energy balance | ɣ | non-dimensional conductance ratio |

| f | friction factor | ||

| fcr | friction factor at Recr | ||

| fqt | friction factor at Reqt | Subscripts | |

| g | gravitational acceleration | b | Bulk |

| Gr | Grashof number | c | cross-section |

| Gr* | modified Grashof number | CFD | computational fluid dynamic |

| Gz | Graetz number | cor | Correlation |

| h | heat transfer coefficient | exp | Experimental |

| I | current j Colburn j-factor | i | Inlet |

| K | thermal conductivity | L | Laminar |

| Kf | fluid thermal conductivity | MCD | Mixed Convection Developing region |

| L | Length | o | outer/outlet |

| Lt | thermal entrance length | QT | quasi-turbulent |

| M | measurement or calculated value | ref | Reference s surface |

| ṁ | mass flow rate | ||

| Nu | Nusselt number | ||

| P | Pressure | ||

| Pe | Peclet number | ||

| Pr | Prandtl number | ||

| Q | heat transfer rate | ||

| Qe | electrical input rate | ||

| Qw | water heat transfer rate | ||

| Q | heat flux | ||

| Ra | Rayleigh number | ||

| Ri | Richardson number | ||

| Ret | start of turbulent flow regime | ||

| ΔRe | width of transitional flow regime | ||

| St | Stanton number | ||

| T | Temperature | ||

| ΔT | temperature difference between surrounding fluid and object surface | ||

| TGf | transition gradient in terms of friction factor results | ||

| TGj | transition gradient in terms of Colburn j-factor results | ||

| V | Velocity | ||

| x | distance from inlet | ||

References

- Stolarski, T.; Nakasone, Y.; Yoshimoto, S. Engineering Analysis with ANSYS Software; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cengel, Y.A.; Ghajar, A.J. Heat and Mass Transfer: Fundamentals & Applications, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Let’s Talk Science. Introduction to Heat Transfer [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://letstalkscience.ca/educational-resources/backgrounders/introduction-heat-transfer (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Zarei Saleh Abad, M.; Ebrahimi-Dehshali, M.; Bijarchi, M.A.; Shafii, M.B.; Moosavi, A. Visualization of pool boiling heat transfer of magnetic nanofluid. Heat Transfer–Asian Res. 2019, 48, 2700–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, D.Y.; Aydin, E.; Gürü, M. The effects of particle mass fraction and static magnetic field on the thermal performance of NiFe2O4 nanofluid in a heat pipe. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 183, 107875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, S.M.; Bijarchi, M.A. Experimental Investigation of Thermal and Hydraulic Characteristics of the Internal Flow in a Circular Tube with Rotating Magnetic Turbulators. Int. Comm. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 162, 108643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.H.; Karayiannis, T.G. Electrohydrodynamic enhancement of heat transfer and fluid flow. Heat Recovery Syst. CHP 1995, 15, 389–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.; Poulter, R. Radial mass flow in electrohydrodynamically-enhanced forced heat transfer in tubes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1987, 30, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Bartoli, C. Heat transfer enhancement due to acoustic fields: A methodological analysis. Acoustics 2019, 1, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainshtein, P.; Fichman, M.; Gutfinger, C. Acoustic enhancement of heat transfer between two parallel plates. Int. Comm. Heat Mass Transf. 1995, 38, 1893–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.M.; Kapan, S.; Sen, M.; Celik, N. Effect of vibration on heat transfer and pressure drop in a heat exchanger with turbulator. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 28, 101680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idan, M.F.; Ramadhan, A.A. An experimental study to show the effect of forced vertical vibrations on the thermal heat transfer coefficient of a flat plate. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2023, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakaç, S.; Pramuanjaroenkij, A. Single-Phase Convective Heat Transfer, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, M.F.; Sultan, S.M.; Tso, C.P. A comprehensive review of mixed convective heat transfer in tubes and ducts: Effects of Prandtl number, geometry, and orientation. Processes 2024, 12, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, S.C.R.; Hudson, J.D.; Smith, N. Steady laminar forced convection from a circular cylinder at low Reynolds numbers. Phys. Fluids 1968, 11, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, H.M.; Dennis, S.C.R. Laminar forced convection from a rotating cylinder. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 1985, 28, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, H.M. A theoretical study of laminar mixed convection from a horizontal cylinder in a cross stream. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 1983, 26, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughn, J.W.; Saniei, N. The Effect of the Thermal Boundary Condition on Heat Transfer from a Cylinder in a Crossflow. In ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.A. Steady-state numerical solution of the Navier–Stokes and energy equations around a horizontal cylinder at moderate Reynolds numbers from 100 to 500. Heat Transf. Eng. 1996, 17, 31–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinuesa, R.; Schlatter, P.; Nagib, H.M. Secondary flow in turbulent ducts with increasing aspect ratio. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2018, 3, 054606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, N.V.; Popelenskaya, N.V.; Stroh, A. Prandtl’s Secondary Flows of the Second Kind. Problems of Description, Prediction, and Simulation. Fluid. Dyn. 2021, 56, 513–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, N. Fundamentals of Heat Transfer Through the Lens of Thermodynamics; Walnut Publication: Delhi, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Levenspiel, O. Engineering Flow and Heat Exchange, 2nd ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Nuclear Power for Everybody. Boundary Layer Thickness. 2025. Available online: https://www.nuclear-power.com/nuclear-engineering/fluid-dynamics/boundary-layer/boundary-layer-thickness/ (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Ehrenfried, C. Convective Turbulent Near Wall Heat Transfer at High PRANDTL Numbers. In Monographic Series TU Graz; Graz University of Technology Press: Graz, Austria, 2020; Volume 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.U.S.; Eastman, J.A. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. In Proceedings of the ASME 1995 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–17 November 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Glauert, M.B. The flow past a rapidly rotating circular cylinder. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1957, 242, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.B.; Travnicek, Z. On the linear heat transfer correlation of a heated circular cylinder in laminar cross flow using a new representative temperature concept. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2001, 44, 4635–4647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.R.; Yovanovich, M.M. Experimental study of forced convection from isotherm circular and square cylinders and toroids. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 1997, 119, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kwon, K.; Choi, H. Numerical solution of flow past a circular cylinder at Reynolds number up to 160. KSME Int J. 1998, 12, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfouz, F.M.; Badr, H.M. Forced convection from a rotationally oscillating cylinder placed in a uniform stream. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2000, 43, 3093–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, E.M.; Abraham, J.P.; Tong, J.C.K. Archival correlations for average heat transfer coefficients for non-circular and circular cylinders and for spheres in cross-flow. Int. J. Heat Mass. Transf. 2004, 47, 5285–5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Talama, F. Flow characteristics and local heat transfer rates for a heated circular cylinder in a crossflow of air. Int. J. Fluid. Mech. Res. 2008, 35, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.A.; Culham, J.R.; Yovanovich, M.M. Fluid flow around and heat transfer from an infinite circular cylinder. J. Heat. Transf. 2005, 127, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eighnam, R.I. Experimental and numerical investigation of heat transfer from a heated horizontal cylinder rotating in still air around its axis. Int. J. Therm. Technol. 2014, 5, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, W. Heat transfer to liquid metals with empirical models for turbulent forced convection in various geometries. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2017, 319, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foust, O.J. Sodium–NaK Engineering Handbook; Gordon and Breach: New York, NY, USA, 1972; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillov, P.L. Thermophysical Properties of Materials for Nuclear Engineering; Obninsk Institute for Atomic Power Engineering: Obninsk, Russia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, J.W. Improvements and Validation of the System Code TRACE for Lead and Lead-Alloy Cooled Fast Reactors Safety-Related Investigations; NUREG/IA-0421; US Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, W.; Hering, W.; Rios, N.D.d.L.; Gonzalez, A. Validation of TRACE in the field of liquid metal heat transfer. ASME Int. Mech. Eng. Congr. Expo. 2014, 46569, V08BT10A100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohse, R. Handbook of Thermodynamic and Transport Properties of Alkali Metals; Blackwell Science: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Buxbaum, R.E. A chemical theory analysis of the solution thermodynamics of oxygen, nitrogen and hydrogen in lead-rich Li-Pb mixtures. J. Less Common. Met. 1984, 97, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barleon, L.; Mack, K.J.; Stieglitz, R. The MEKKA Facility–A Flexible Tool to Investigate MHD Flow Phenomena; FZKA-5821; Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe Technik und Umwelt: Karlsruhe, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dhiman, A.K.; Chhabra, R.P.; Sharma, A.; Eswaran, V. Effects of Reynolds and Prandtl numbers on heat transfer across a square cylinder in the steady flow regime. Numer. Heat. Transf. Part A 2006, 49, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Eswaran, V. Heat and fluid flow across a square cylinder in the two-dimensional laminar flow regime. Numer. Heat. Transf. Part A 2010, 45, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, T.G.; Sen, M.; Gad-el-Hak, M. Numerical and experimental investigation of flow past a freely rotatable square cylinder. J. Fluids Struct. 1994, 8, 555–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohankar, A.; Davidson, L.; Norberg, C. Numerical simulation of unsteady flow around a square two-dimensional cylinder. In Proceedings of the Australasian Fluid Mechanics Conference, Hobart, Australia, 14–18 December 1995; pp. 517–520. [Google Scholar]

- Sohankar, A.; Norberg, C.; Davidson, L. Numerical simulation of unsteady low Reynolds number flow around rectangular cylinders at incidence. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1997, 69–71, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, S.C.R.; Walker, J.D.A.; Hudson, J.D. Heat transfer from a sphere at low Reynolds numbers. J. Fluid. Mech. 1973, 60, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, R. Heat transfer from a sphere in a stream at small Reynolds number. J. Fluid. Mech. 1968, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, S. Forced convection heat transfer correlations for flow in pipes, past flat plates, single cylinders, single spheres, and packed beds. AIChE J. 1972, 18, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, A.; Yuki, T.; Mitsuishi, N. Combined forced and natural convection heat transfer from spheres at small Reynolds number. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 1976, 9, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Mucoglu, A. Analysis of mixed forced and free convection about a sphere. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 1977, 20, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, B.A.; Olson, J.W. Heat transfer to spheres at low to intermediate Reynolds numbers. Chem. Eng. Commun. 1987, 58, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, X.; Li, D.; Wei, A.; Luo, K.; Fan, J. Vortex dynamics of a sphere wake in proximity to a wall. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 2016, 79, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, J.B.; Kruyt, N.P.; Venner, C.H. Experimental study of forced convective heat transfer from smooth, solid spheres. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2017, 109, 1059–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hout, R.; Eisma, J.; Elsinga, G.E.; Westerweel, J. Experimental study of the flow in the wake of a stationary sphere immersed in a turbulent boundary layer. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2018, 3, 024601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hema Sundar Raju, B.; Nath, D.; Pati, S. Effect of Prandtl number on thermofluidic transport characteristics for mixed convection past a sphere. Int. Commun. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2018, 98, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, I.; Lehmkuhl, O.; Soria, M.; Gomez, S.; Domínguez-Pumar, M.; Kowalski, L. Fluid dynamics and heat transfer in the wake of a sphere. Int. J. Heat. Fluid. Flow. 2019, 76, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, B.H.S.; Nath, D.; Pati, S. Mixed convective heat transfer past an isoflux/isothermal sphere: Influence of Prandtl number. Phys. Scr. 2020, 95, 085211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, V.T. The overall convective heat transfer from smooth circular cylinders. Adv. Heat. Transf. 1975, 11, 199–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botton, V.; Boussaa, R.; Debacque, R.; Hachani, L.; Zaidat, K.; Ben Hadid, H.; Fautrelle, Y.; Henry, D. A 2D½ model for low Prandtl number convection in an enclosure. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2013, 71, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.D.; Petitpas, P.; Garnier, C.; Paulin, J.P.; Fautrelle, Y. A quasi-two-dimensional benchmark experiment for the solidification of a tin–lead binary alloy. Comptes Rendus Mécanique 2007, 335, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.D.; Fautrelle, Y. An investigation of the influence of natural convection on tin solidification using a quasi two-dimensional experimental benchmark. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2009, 52, 5624–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachani, L.; Saadi, B.; Wang, X.D.; Nouri, A.; Zaidat, K.; Belgacem-Bouzida, A.; Ayouni-Derouiche, L.; Raimondi, G.; Fautrelle, Y. Experimental analysis of the solidification of Sn-3 wt.%Pb alloy under natural convection. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2012, 55, 1986–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussaa, R.; Budenkova, O.; Hachani, L.; Wang, X.; Saadi, B.; Zaidat, K.; Ben Hadid, H.; Fautrelle, Y. 2D and 3D Numerical Modelling of Solidification Benchmark of Sn-3Pb Alloy Under Natural Convection. In CFD Modelling and Simulation in Materials Processing; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.M.; Sharma, K.V.; Bakar, R.A.; Kadirgama, K. Effect of tube cross-sectional area on friction factor and heat transfer for nanofluid turbulent flow. Int. Commun. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2013, 47, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascioli, E.; Buckingham, S.; Keijers, S.; Van Tichelen, K.; Kenjereš, S. Numerical and experimental analysis of a planar jet with heated co-flow at medium and low Prandtl numbers. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2020, 361, 110570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, L.P.; Antonia, R.A. Turbulent Prandtl number in a circular jet. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 1990, 33, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Venuta, I.; Boghi, A.; Angelino, M.; Gori, F. Passive scalar diffusion in turbulent rectangular free jets with turbulent Prandtl/Schmidt analysis. Int. Commun. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2018, 95, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errico, O.; Stalio, E. DNS of low-Prandtl turbulent convection above a wavy wall. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2015, 290, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fregni, A.; Angeli, D.; Cimarelli, A.; Stalio, E. DNS of a buoyant triple jet at low Prandtl number. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2019, 143, 118466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grötzbach, G. Challenges in low-Prandtl-number heat transfer simulation. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2013, 264, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kays, W.M. Turbulent Prandtl number—Where are we? J. Heat Transfer 1994, 116, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, A.; Faraj, J.; Harika, E.; Hachem, F.; Khaled, M. Development of a new method for estimating the overall heat transfer coefficient of heat exchangers—Validation in automotive applications. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 28, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masalha, I.; Masuri, S.U.; Badran, O.O.; Ariffin, M.K.A.M.; Abu Talib, A.R.; Alfaqs, F. Outdoor experimental and numerical simulation of photovoltaic cooling using porous media. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 42, 102748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogesh, S.; Bijjargi, K.S.; Shaikh, K.A. Cooling techniques for photovoltaic module for improving its conversion efficiency: A review. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. 2016, 7, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, H.; Ghasempour, R.; Shafii, M.B.; Ahmadi, M.H.; Yan, W.M.; Nazari, M.A. Numerical simulation of PV cooling using single-turn pulsating heat pipe. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2018, 127, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, S.; Soni, M.S.; Gakkhar, N. Modelling and simulation of concentrating photovoltaic system with earth–water heat exchanger cooling. Energy Procedia 2017, 109, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masalha, I.; Elayyan, M.; Al-Jamea, D.M.K.; Omar, B.; Alsabagh, A.S.; Darweesh, N.A. Experimental and numerical study to improve PV module efficiency using nanofluid cooling. Int. Rev. Mech. Eng. 2021, 15, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, Z.; Rahimi, M.; Azimi, N. Using high-frequency ultrasound and nanofluid to enhance PV cooling performance. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 160, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahaidarah, H.M. Experimental performance evaluation and modelling of jet-impingement cooling for photovoltaic thermal management. Sol. Energy 2016, 135, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, H.; Patel, A.; Boersma, B.J.; Pecnik, R. The effect of thermal boundary conditions on forced convection heat transfer to fluids at supercritical pressure. J. Fluid. Mech. 2016, 800, 531–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, W.; Yin, M.; Xi, W.; Sunden, B. Flow and heat transfer characteristic of regenerative cooling channels using supercritical CO2 with circular tetrahedral lattice structures. Therm. Eng. 2025, 71, 106204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Zeng, Y. Comparative study on thermo-hydraulic performance of different cross-section shapes of microchannels with supercritical CO2 fluid. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 5525235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Yu, H.; Tian, W.; Qiu, S.; Su, G. DNS study of turbulent heat transfer with different Prandtl numbers under constant wall-temperature difference condition. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2025, 185, 105770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, H.; Ohsaka, K.; Abe, H.; Yamamoto, K. DNS of turbulent heat transfer in channel flow with low to medium–high Prandtl number fluid. Int. J. Heat. Fluid. Flow. 1998, 19, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcantara-Avila, F.; Hoyas, S. Direct numerical simulation of thermal channel flow for medium-high Prandtl numbers up to Reτ = 2000. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2021, 176, 121412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, H.; Antonia, R.A. Turbulent Prandtl number in a channel flow for Pr = 0.025 and 0.71. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Turbulence and Shear Flow Phenomena, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 22–24 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pirozzoli, S. Prandtl number effects on passive scalars in turbulent pipe flow. J. Fluid. Mech. 2023, 965, A7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Shao, Y.; Zhong, W. Experimental study on convective heat transfer characteristics of supercritical carbon dioxide in a vertical tube with low mass flux. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 230, 120798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Tian, R.; Wei, M.; He, S.; He, J. Characteristic stages of heat transfer for supercritical CO2 flowing downward in a vertical tube under cooling conditions. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2024, 205, 106136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztabak, E.; Gokkaya, O.; Ahn, H. Heat transfer characteristics of horizontal supercritical CO2 flow through a microtube at low Reynolds numbers and its comparison with vertical flows. Exp. Therm. Fluid. Sci. 2023, 147, 110957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Xu, B.; Chen, Z. Experimental investigation on cooling heat transfer and buoyancy effect of supercritical carbon dioxide in horizontal and vertical micro-channels. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2021, 181, 121792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Xiang, M.; Zhang, H.; Huai, X.; Cheng, K.; Cui, X. Thermal-hydraulic characteristics of supercritical pressure CO2 in vertical tubes under cooling and heating conditions. Energy 2019, 170, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabhi, S.K.; Patel, V.R.; Mazar, A.S.; Dipakkumar, J.P. Development of novel thermal storage integrated pasteurizer for solar milk pasteurization system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 263, 125375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.S.; Latif, Y.; Munir, A.; Hensel, O. Comparative thermal analyses of solar milk pasteurizers integrated with solar concentrator and evacuated tube collector. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 7917–7930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, H.; Patel, R.; Sathyamurthy, R. Investigation and performance analysis of solar milk pasteurisation system. Int. J. Ambient. Energy 2019, 42, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaar, M.; Boughanmi, H.; Bouadila, S.; Jarraya, M. Parametric study of plate heat exchanger for eventual use in a solar pasteurization process designed for small milk collection centres in Tunisia. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 45, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, N.; Genc, S. Thermodynamic analysis of a milk pasteurization process assisted by geothermal energy. Energy 2015, 90, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayou, D.S.; Hargiyanto, R.; Coronas, A. Ammonia-based compression heat pumps for simultaneous heating and cooling applications in milk pasteurization processes: Performance evaluation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 217, 119168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.O.L. Milk temperatures of dairy cows during milking. Br. Vet. J. 1980, 136, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bon, J.; Clemente, G.; Vaquiro, H.; Mulet, A. Simulation and optimization of milk pasteurization processes using a general process simulator (ProSimPlus). Comput. Chem. Eng. 2010, 34, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, C.O. Short-time pasteurization of milk. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1943, 35, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulenberg, T.; Stieglitz, R. Flow measurement techniques in heavy liquid metals. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2010, 240, 2077–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. A review of recent numerical and experimental research progress on CDA safety analysis of LBE-/lead-cooled fast reactors. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2017, 110, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Lan, Z.; Wei, S.; Chen, R.; Tian, W.; Su, G. Review of thermal-hydraulic issues and studies of lead-based fast reactors. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.S.; Abodayeah, K.; Nawaz, Y. Two-stage explicit numerical scheme for mixed convective flow in hybrid materials with variable properties. Hybrid. Adv. 2025, 11, 100517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanitjai, S.; Goldstein, R.J. Heat transfer from a circular cylinder to mixtures of water and ethylene glycol. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2004, 47, 4785–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frossling, N. Evaporation, heat transfer, and velocity distribution in laminar boundary-layer flow. Acta Univ. Lund. NACA TM 1958, 1432. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2060/20030068788 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Eckert, E.; Soehngen, E. Distribution of heat-transfer coefficients around circular cylinders in crossflow at Re = 20–500. Trans. ASME 1952, 74, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, E. Total and local heat transfer from a smooth circular cylinder in crossflow at high Reynolds numbers. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 1975, 18, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukauskas, A.; Ziugzda, J. Heat Transfer of a Cylinder in Crossflow; Hemisphere Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi, T. Correlation between heat transfer and fluctuating pressure in the separated region of a circular cylinder. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 1984, 27, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuse, H.; Oyama, T.; Kanamori, S. Influence of free-stream turbulence on rear-surface cylinder heat transfer: Effects of high-frequency turbulence. Heat. Transfer Jpn. Res. 1985, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, S.; Dalal, A.; Biswas, G. Unsteady wake dynamics and heat transfer in forced and mixed convection past a circular cylinder for high Prandtl numbers. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2011, 54, 3536–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sid, S.; Dubief, Y.; Terrapon, V.E. Direct numerical simulation of mixed convection in turbulent channel flow: On the Reynolds number dependency of momentum and heat transfer under unstable stratification. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computational Heat and Mass Transfer (ICCHMT), Instanbul, Turkey, 25–28 May 2015; Available online: https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/185877 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Perkins, H.C.; Leppert, G. Local heat-transfer coefficients on a uniformly heated cylinder. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 1964, 7, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.W.; Finlayson, B.A. Heat transfer in flow past cylinders at Re < 150. Part 1: Constant fluid properties. Numer. Heat. Transfer A 1987, 12, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanitjai, S.; Goldstein, R.J. Forced convection heat transfer from a circular cylinder in crossflow to air and liquids. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2004, 47, 4795–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rasheed, H.; Al-Zubaidi, A.; Islam, S.; Saleem, S.; Khan, Z.; Khan, W. Effects of Joule heating and viscous dissipation on MHD boundary-layer flow of Jeffrey nanofluid over a vertically stretching cylinder. Coatings 2021, 11, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.; Arifuzzaman, S.M.; Karim, I.; Khan, M.S. Impacts of magnetic field and radiation absorption on mixed-convective Jeffrey nanofluid flow over a vertical stretching sheet with stability analysis. J. Nanofluids 2017, 6, 1082–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusafir, R.S.; Jasim, A.A.; Al-Dahhan, M.H. Review of the fluid dynamics and heat transport phenomena in packed pebble-bed nuclear reactors. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 2023, 197, 1001–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Deng, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Qiu, S.; Su, G.H. Experimental analysis of flow and convective heat transfer in the water-cooled packed pebble-bed nuclear reactor core. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2020, 122, 103298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmohsin, R.S.; Al-Dahhan, M.H. Characteristics of convective heat transport in a packed pebble-bed reactor. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2015, 284, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Deng, J.; Zhang, D.; Gu, H. Review of experimental research on thermal-hydraulic characteristics in pebble-bed reactor cores and fusion breeder blankets. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 11352–11383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekifi, T.; Boukraa, M. CFD applications for sensible heat storage: A comprehensive review of numerical studies. J. Energy Storage 2023, 68, 107893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odenthal, C.; Tombrink, J.; Klasing, F.; Bauer, T. Comparative study of models for packed-bed molten-salt storage systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 226, 120245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Creaser, D.; Siahrostami, S.; Grönbeck, H.; Ojagh, H.; Skoglundh, M. Catalytic hydrogenation of C=C and C=O in unsaturated fatty acid methyl esters. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 2427–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.M.; Zheng, Q.Y.; Zhang, X.R. Heat transfer model of a particle-energy-storage moving packed-bed heat exchanger. Energy Storage 2020, 2, e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Guo, Z.; Jia, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, Q. Numerical investigation of a new tube type for shell-and-tube moving packed-bed heat exchangers. Powder Technol. 2021, 394, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R.-H.; Moon, J.-Y.; Chung, B.-J. Reynolds analogy in a packed bed for a high-Prandtl-number fluid. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2024, 232, 125917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, L.; Genuin, S.; Lohner, T.; Stahl, K. Numerical analysis of heat transfer of gears under oil-dip lubrication. Tribol. Int. 2024, 195, 109652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.M. Measurements of convective heat transfer from a horizontal cylinder rotating in water. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 1963, 6, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changenet, C.; Oviedo-Marlot, X.; Velex, P. Power-loss prediction in geared transmissions using thermal networks: Application to a six-speed manual gearbox. J. Mech. Des. 2006, 128, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschold, C.; Sedlmair, M.; Lohner, T.; Stahl, K. Efficiency and heat-balance calculation of worm gears. Forsch. Ingenieurwes 2020, 84, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschold, C.; Sedlmair, M.; Lohner, T.; Stahl, K. Calculating component temperatures in gearboxes for transient operating conditions. Forsch. Ingenieurwes 2022, 86, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayan, E.; Kromer, C.; Schwitzke, C.; Bauer, H.-J. Experimental determination of heat-transfer coefficients on impingement-cooled gear flanks: Validation of the evaluation method. J Turbomach. 2022, 144, 081008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccioni, L.; Concli, F. Computational fluid dynamics applied to lubricated mechanical components: A review of simulation approaches for gears, bearings, and pumps. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Wu, W.; Hou, X.; Nelias, D.; Yuan, S. Research on flow pattern of low temperature lubrication flow field of rotating disk based on MPS method. Tribol Int. 2023, 180, 108221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]